Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

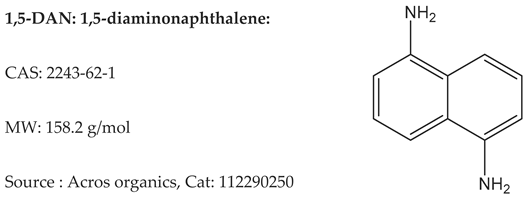

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

| Polluting solvent (H2O) | |

| Quantity added (µL) | Concentration H2O (mol/dm3) |

| 0 | 0.0000 |

| 10 | 0.1846 |

| 20 | 0.3679 |

| 30 | 0.5501 |

| 40 | 0.7310 |

| 50 | 0.9107 |

| 60 | 1.0893 |

| 70 | 1.2667 |

| 80 | 1.4430 |

| 90 | 1.6181 |

| 100 | 1.7921 |

| 120 | 2.1368 |

| 140 | 2.4770 |

| 160 | 2.8129 |

| 180 | 3.1447 |

| 200 | 3.4722 |

3. Results and Discussion

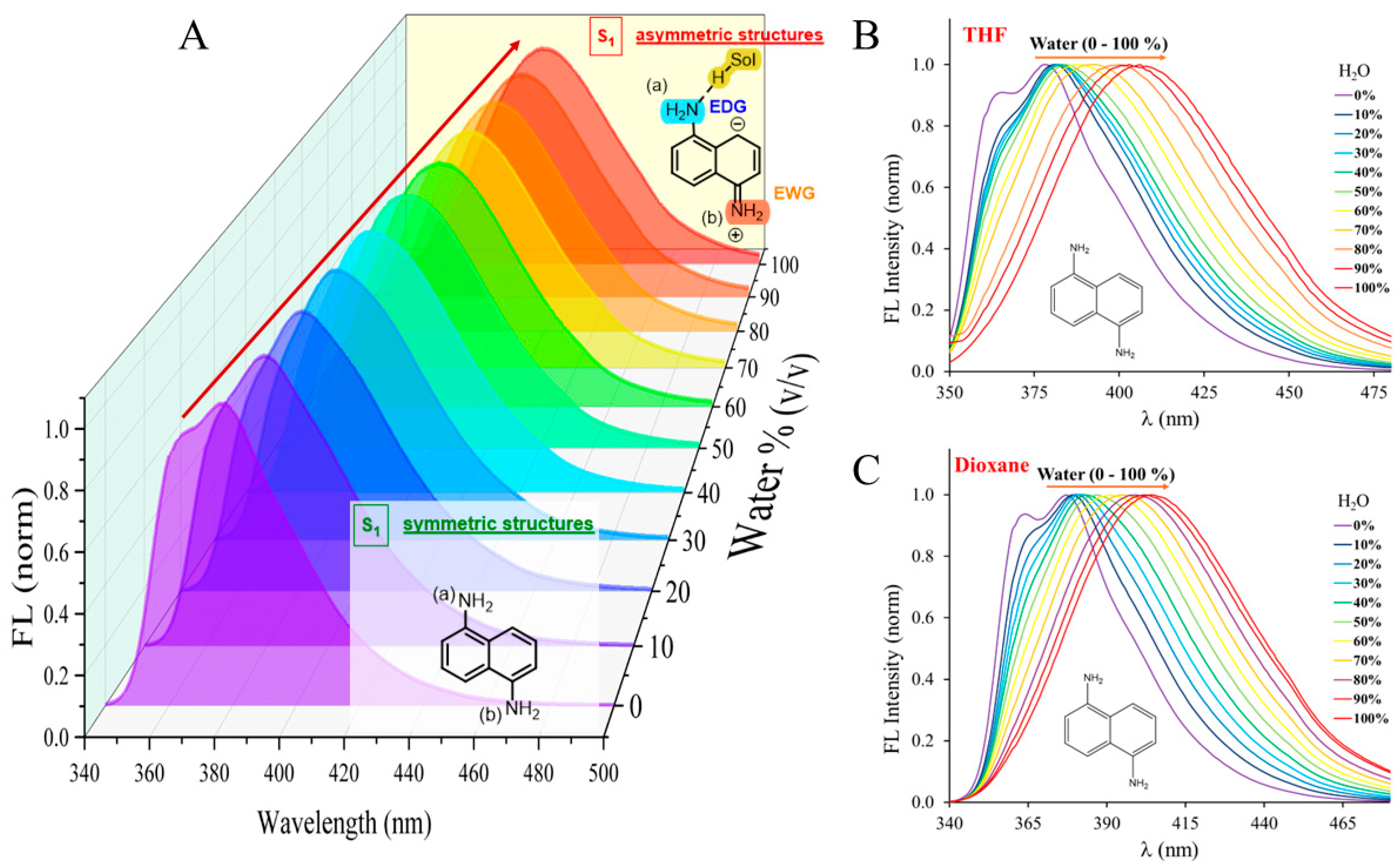

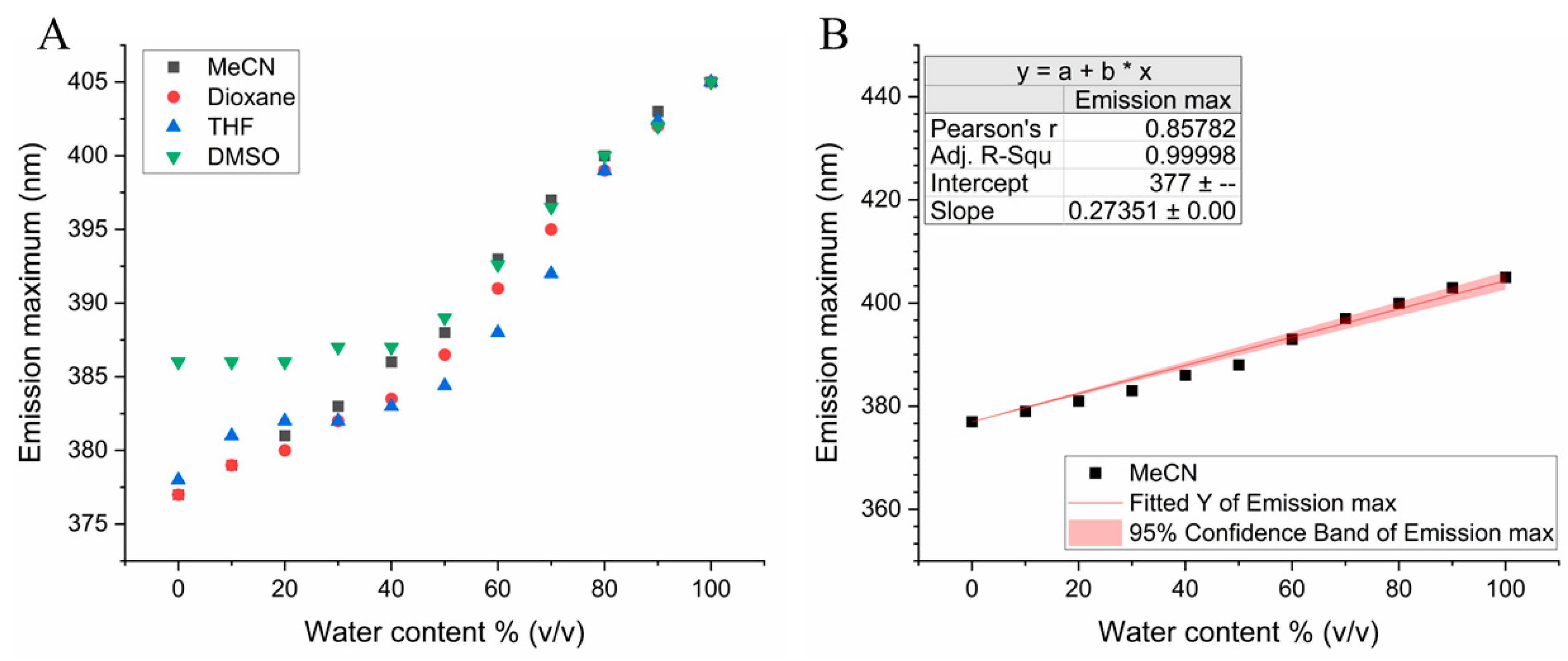

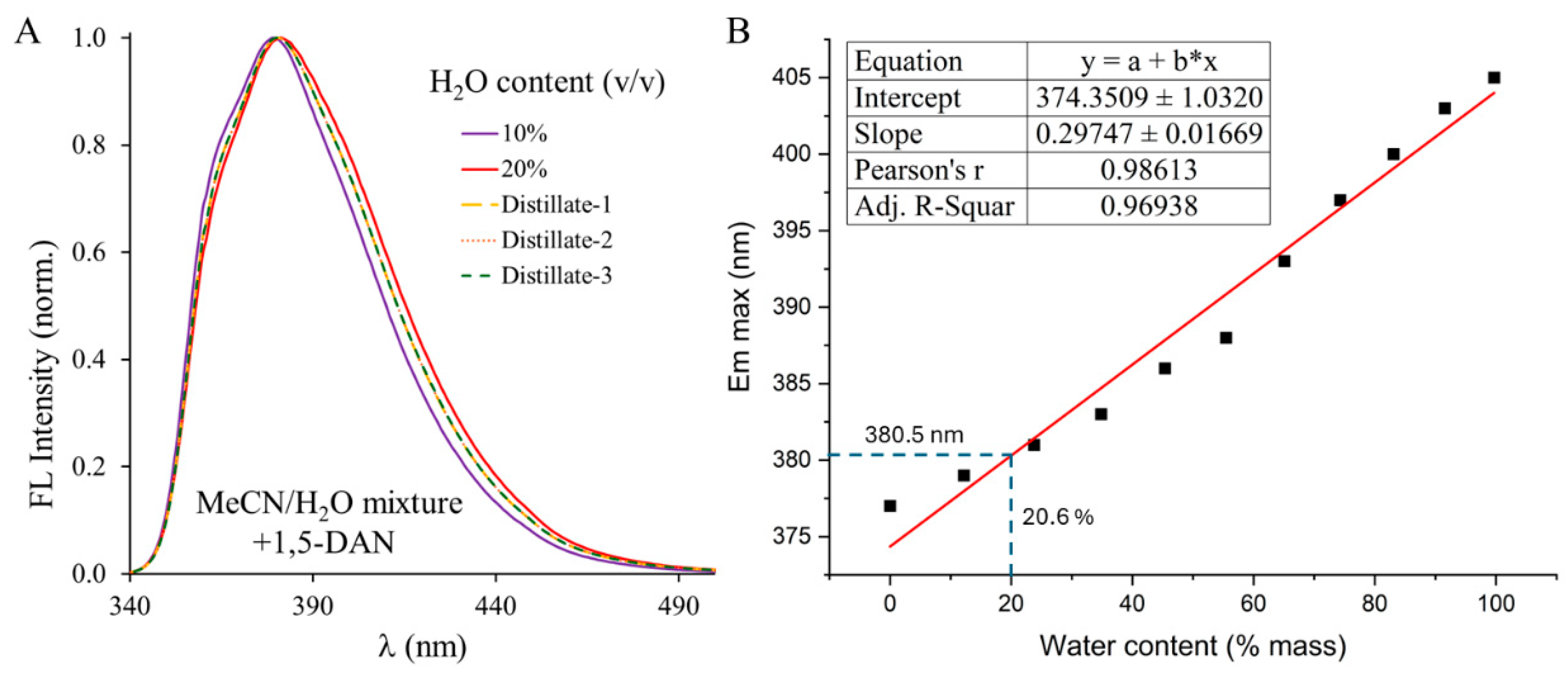

3.1. Determination of Water Content of Solvent Mixtures in the Range of 0-100%

| Water content (v/v) | |||||||||||

| 0% | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% | 100% | |

| Solvent | Emission maximum (nm) | ||||||||||

| MeCN | 377 | 379 | 381 | 383 | 386 | 388 | 393 | 397 | 400 | 403 | 405 |

| THF | 378 | 381 | 382 | 382 | 383 | 384 | 388 | 392 | 399 | 402 | 405 |

| Dioxane | 377 | 379 | 380 | 382 | 383 | 386 | 391 | 395 | 399 | 402 | 404 |

| DMSO | 386 | 386 | 386 | 387 | 387 | 389 | 392 | 396 | 400 | 402 | 403 |

3.2. Testing the Method on MeCN-Water Azeotrope as Real Sample

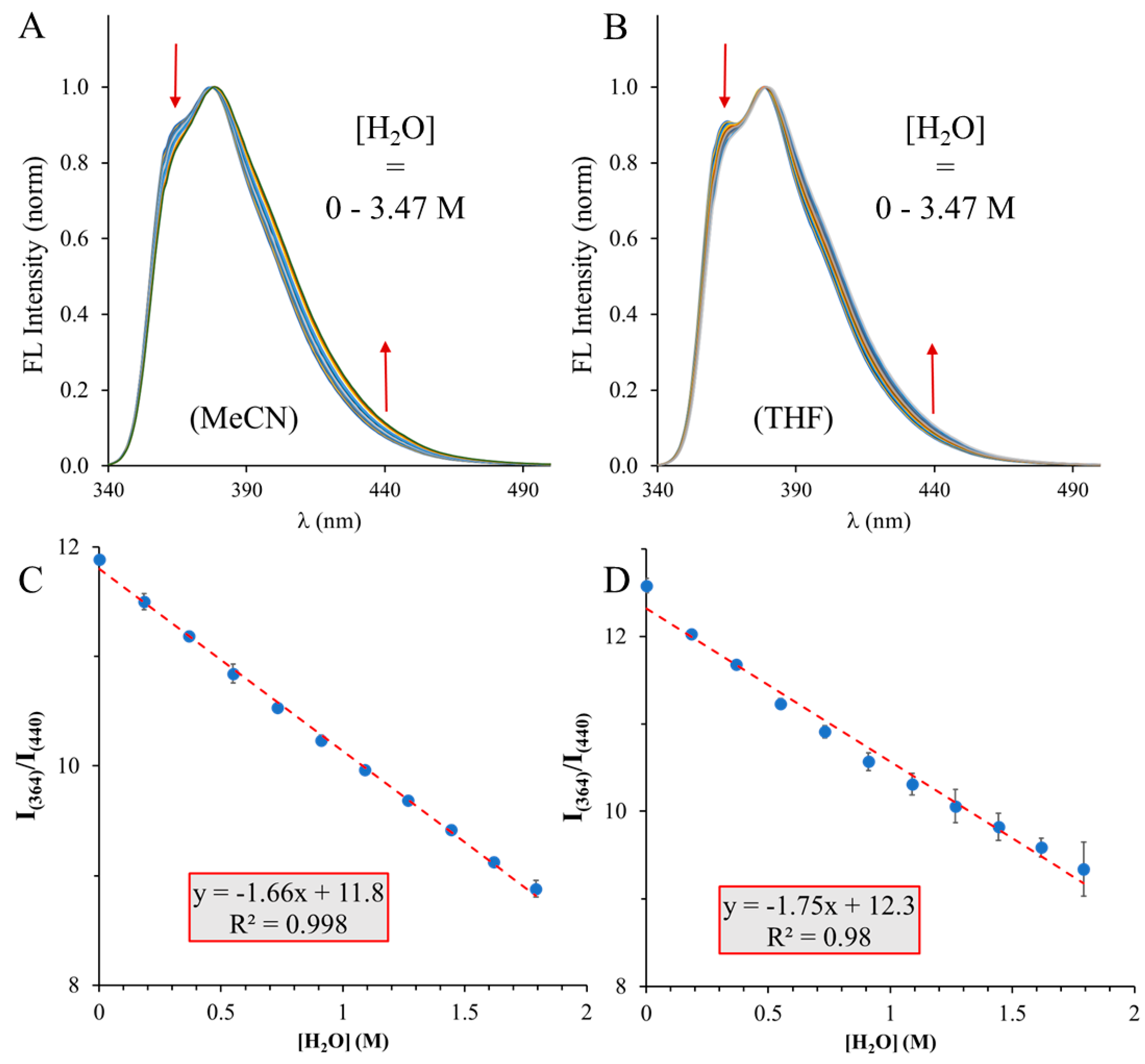

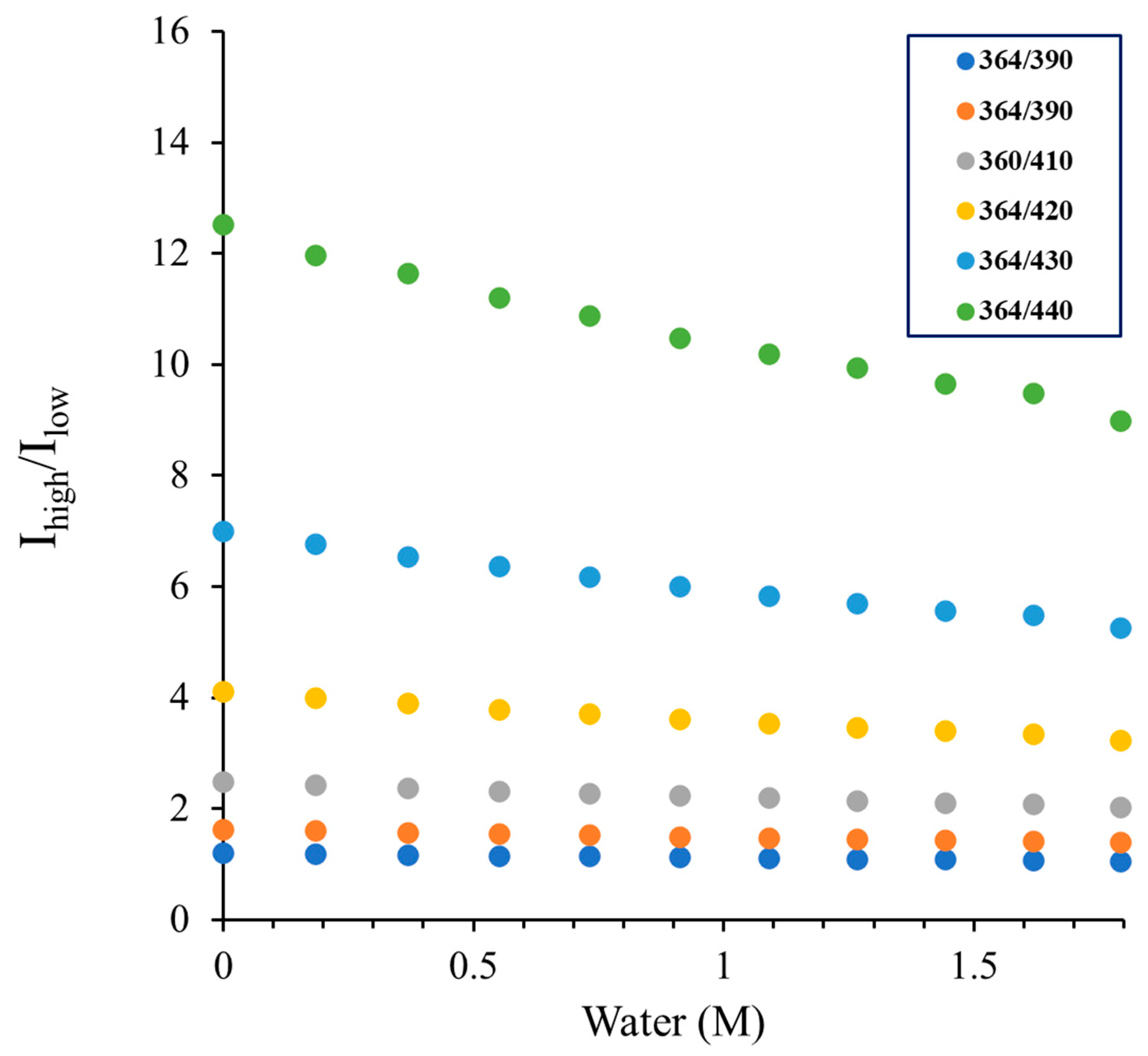

3.3. Determination of Water Content of Solvent Mixtures in the Low Concentration Range

3.4. Limit of Detection and Limit of Quantification of the Method

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Shivam, L., Dr. Sachin, N., Dr. Shailesh, L. & Dr. Anuradha, P. Review on Moisture Content: A Stability Problem in Pharmaceuticals. EPRA International Journal of Research & Development (IJRD), 27-33 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Pahl, C., Pasel, C., Luckas, M. & Bathen, D. Adsorptive Water Removal from Organic Solvents in the ppm-Region. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 83, 177-182 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Goderis, H. L., Fouwe, B. L., Van Cauwenbergh, S. M. & Tobback, P. P. Measurement and control of water content of organic solvents. Analytical Chemistry 58, 1561-1563 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Heitz, E. in Advances in Corrosion Science and Technology Ch. Chapter 3, 149-243 (1974).

- Hall, T. F. et al. Computer-Controlled On-Line Moisture Measurement in Organic Solvents Using a Novel Potentiometric Technique. Measurement and Control 22, 240-244 (1989). [CrossRef]

- Schöffski, K. & Strohm, D. in Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry (2000).

- Padivitage, N. L. T., Smuts, J. P. & Armstrong, D. W. in Specification of Drug Substances and Products 223-241 (2014).

- Jouyban, A. & Rahimpour, E. Optical sensors for determination of water in the organic solvents: a review. Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society 19, 1-22 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L. et al. Quantitative Determination of Water in Organic Liquids by Ambient Mass Spectrometry. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 62 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C., Weremfo, A., Wan, C. & Zhao, C. Cathodic Stripping Determination of Water in Organic Solvents. Electroanalysis 26, 596-601 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Barbetta, A. & Edgell, W. Infrared Spectrophotometric Determination of Trace Water in Selected Organic Solvents. Applied Spectroscopy 32, 93-98 (1978). [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. et al. Determination of Trace Water Using Fluorescence Probes Based on Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Quantum Dot Fluorescence Senors (Y-CDs and R-CDs). ChemistrySelect 8 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wei, J. et al. A novel fluorescent sensor for water in organic solvents based on dynamic quenching of carbon quantum dots. New Journal of Chemistry 42, 18787-18793 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-Y. et al. High-Performance Turn-On Fluorescent Metal–Organic Framework for Detecting Trace Water in Organic Solvents Based on the Excited-State Intramolecular Proton Transfer Mechanism. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 14, 55997-56006 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Niu, C., Li, L., Qin, P., Zeng, G. & Zhang, Y. Determination of Water Content in Organic Solvents by Naphthalimide Derivative Fluorescent Probe. Analytical Sciences 26, 671-674 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, N. I., Krasteva, P. V., Bakov, V. V. & Bojinov, V. B. A Highly Water-Soluble and Solid State Emissive 1,8-Naphthalimide as a Fluorescent PET Probe for Determination of pHs, Acid/Base Vapors, and Water Content in Organic Solvents. Molecules 27 (2022). [CrossRef]

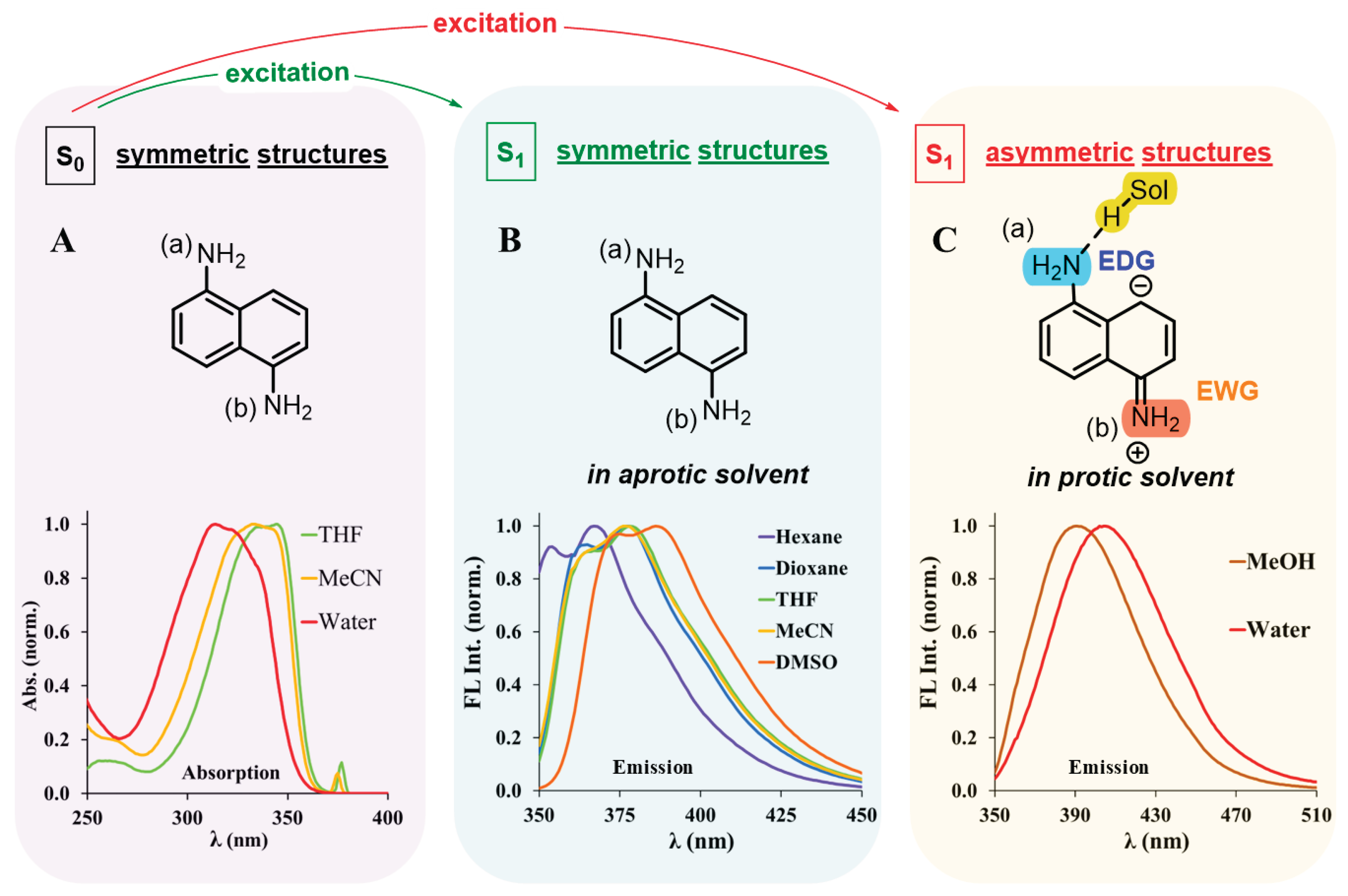

- Kopcsik, E. et al. Excited state iminium form can explain the unexpected solvatochromic behavior of symmetric 1,5- and 1,8-diaminonaphthalenes. Chemical Communications 60, 1008-1011 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Virk, A. S., Codling, D. J., Stait-Gardner, T. & Price, W. S. Non-Ideal Behaviour and Solution Interactions in Binary DMSO Solutions. ChemPhysChem 16, 3814-3823 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Goetz, G. H., Beck, E. & Tidswell, P. W. On-Column Solvent Exchange for Purified Preparative Fractions. JALA: Journal of the Association for Laboratory Automation 16, 335-346 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Wang, K., Lian, M., Li, Z. & Du, T. Process Simulation of the Separation of Aqueous Acetonitrile Solution by Pressure Swing Distillation. Processes 7 (2019). [CrossRef]

| Water content (v/v) | |||||||||||

| 0% | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | 80% | 90% | 100% | |

| Solvent (µL) | 3000 | 2700 | 2400 | 2100 | 1800 | 1500 | 1200 | 900 | 600 | 300 | 0 |

| Water (µL) | 0 | 300 | 600 | 900 | 1200 | 1500 | 1800 | 2100 | 2400 | 2700 | 3000 |

| Solvent | Equation of Calibrating line | LOD [M] | LOD [%] | LOQ [M] |

LOQ [%] |

R2 |

| MeCN | y = -1.66x + 11.8 | 0.047 | 0.08 | 0.156 | 0.24 | 0.998 |

| THF | y = -1.75x + 12.3 | 0.076 | 0.13 | 0.229 | 0.40 | 0.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).