Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

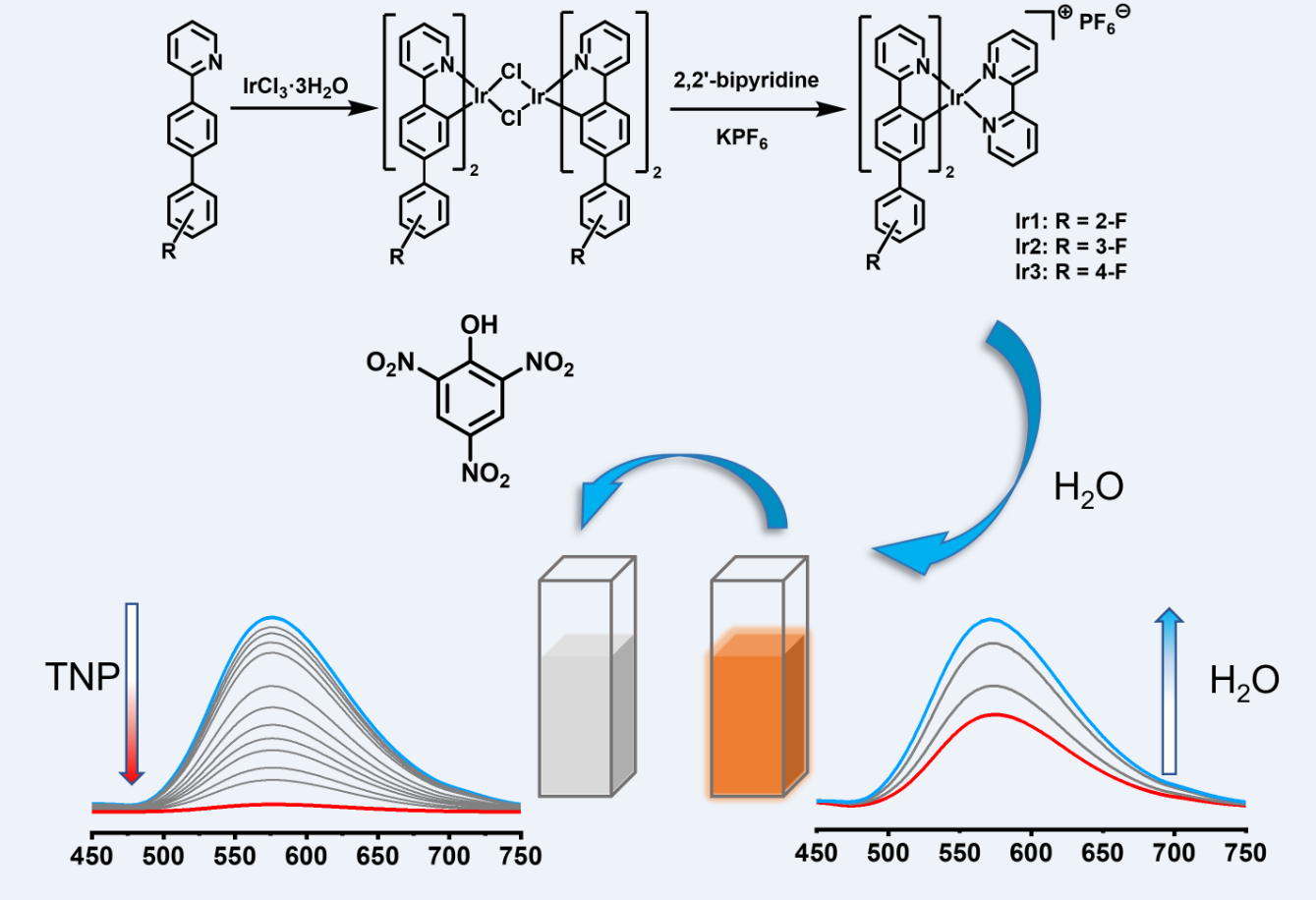

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Instruments

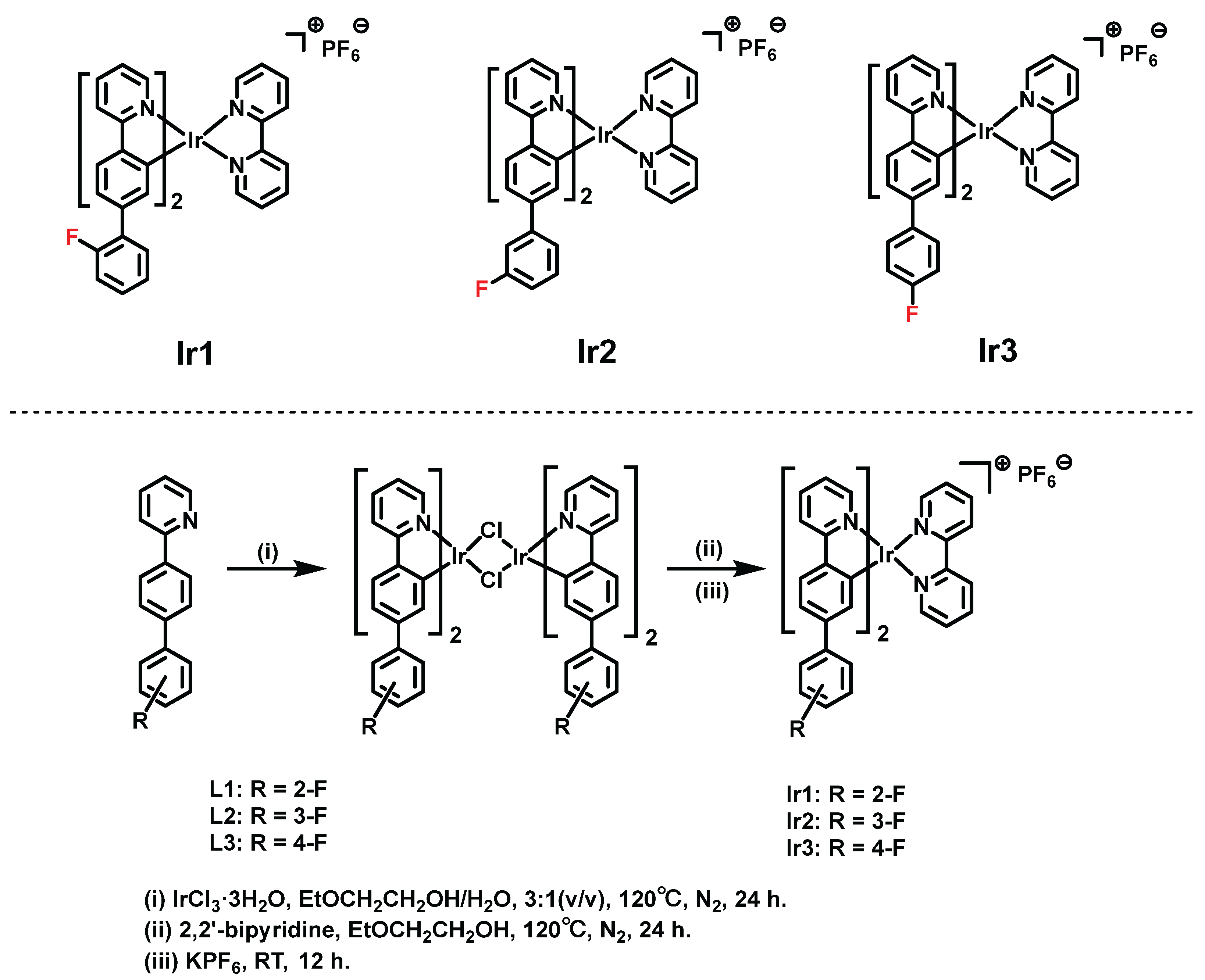

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of Complexes

2.3. Tests for the Detection of TNP

3. Results and Discussion

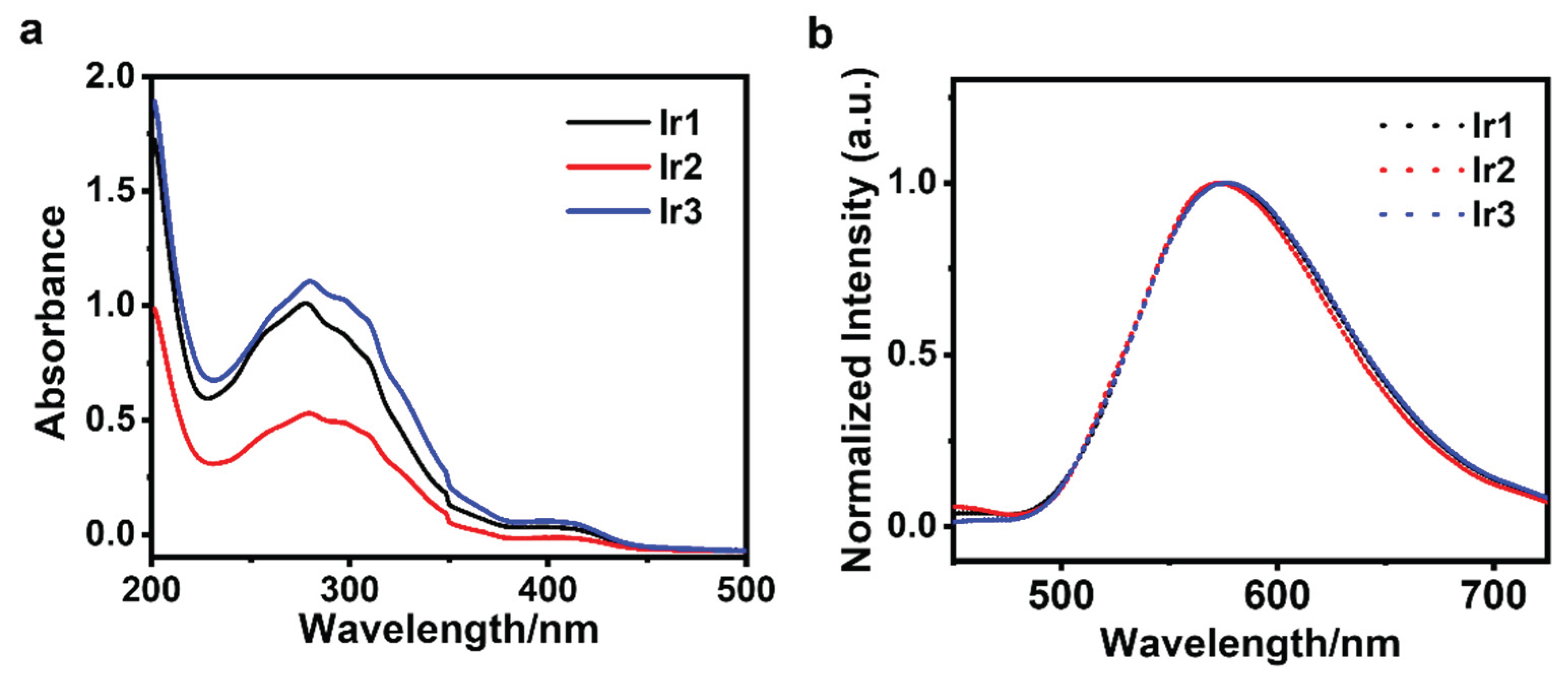

3.1. Photophysical Properties

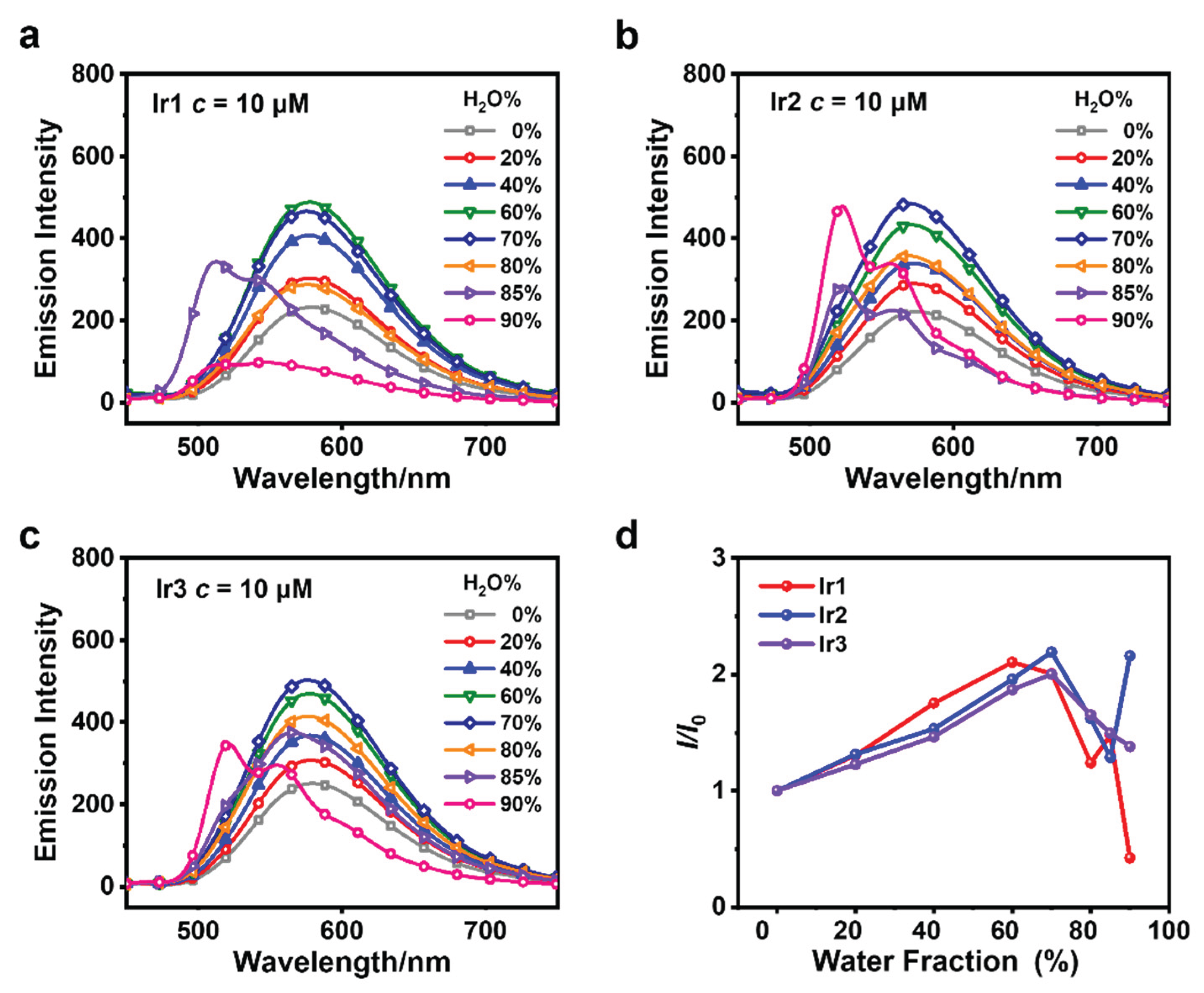

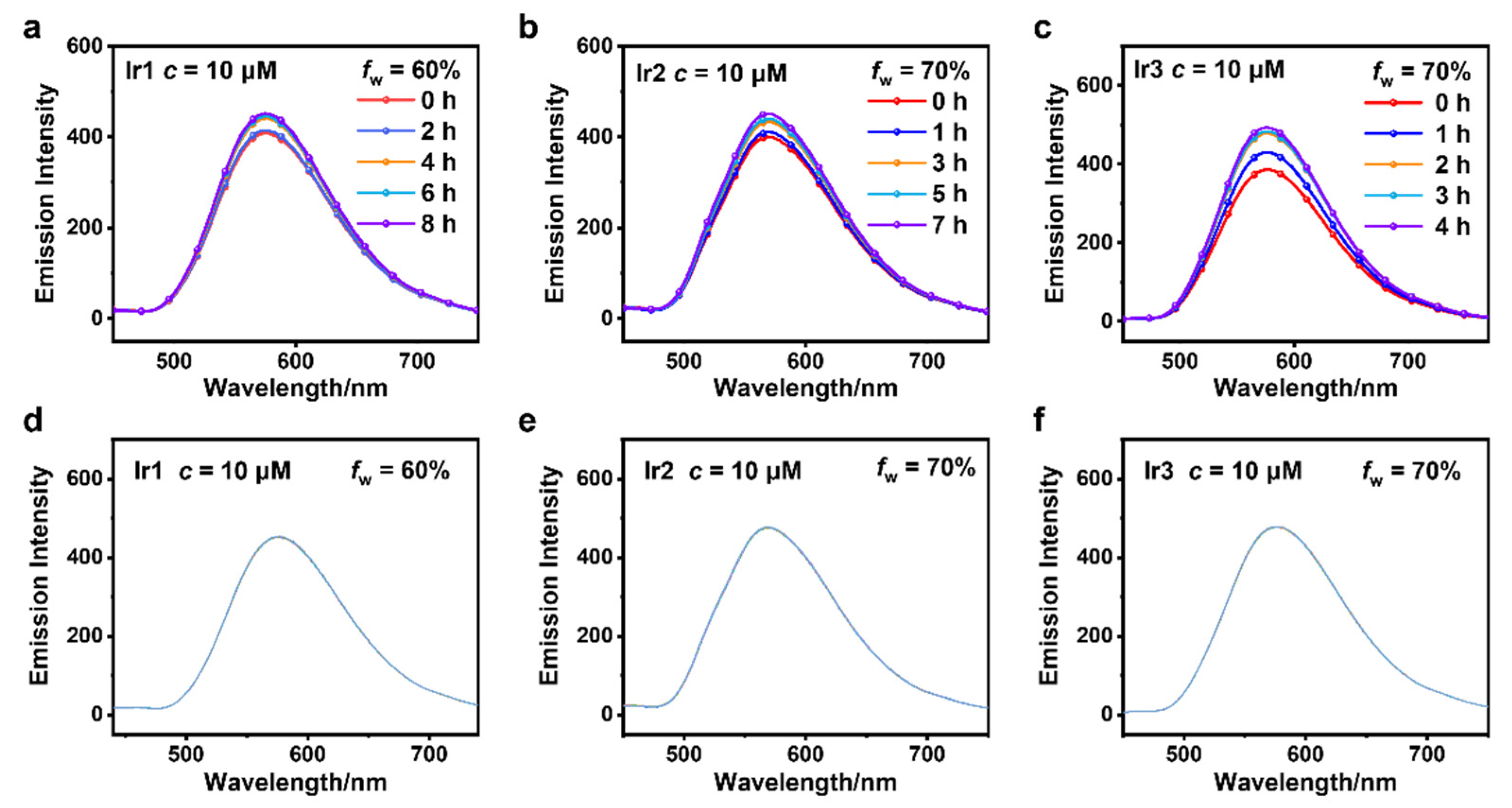

3.2. AIPE Properties and Stability Testing

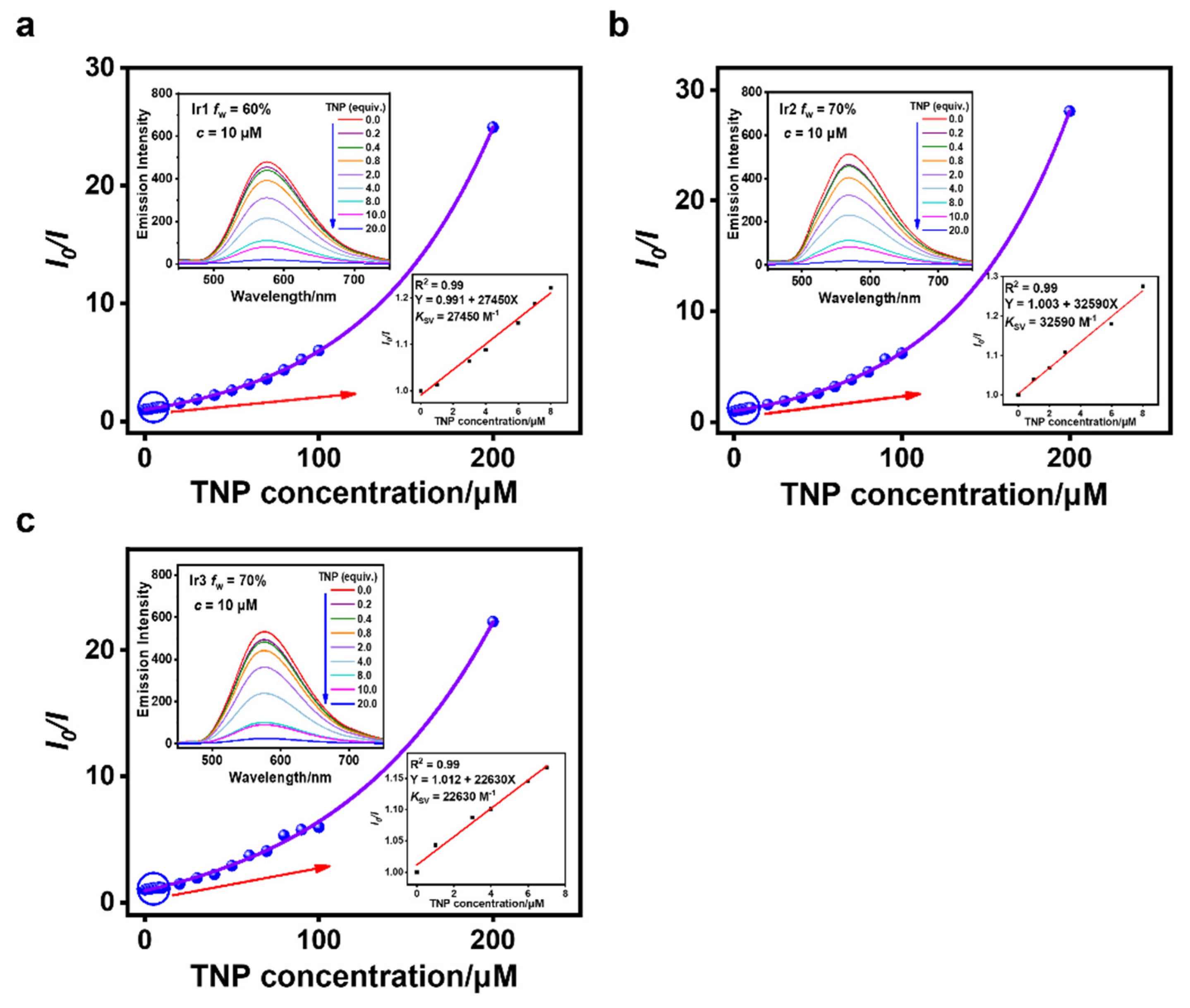

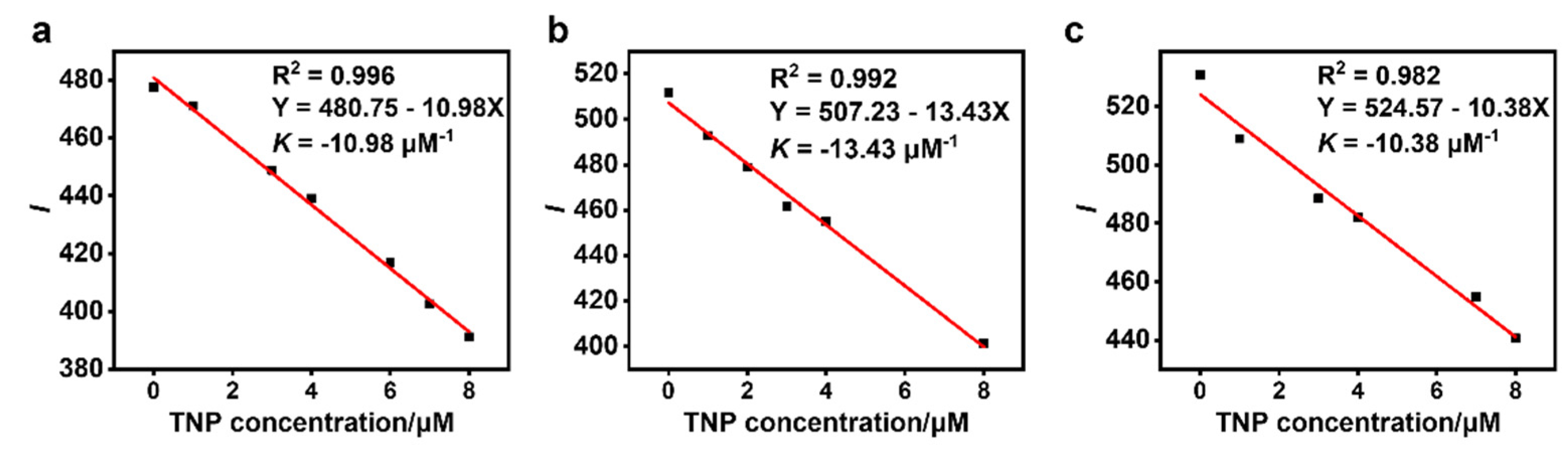

3.3. Sensing of TNP

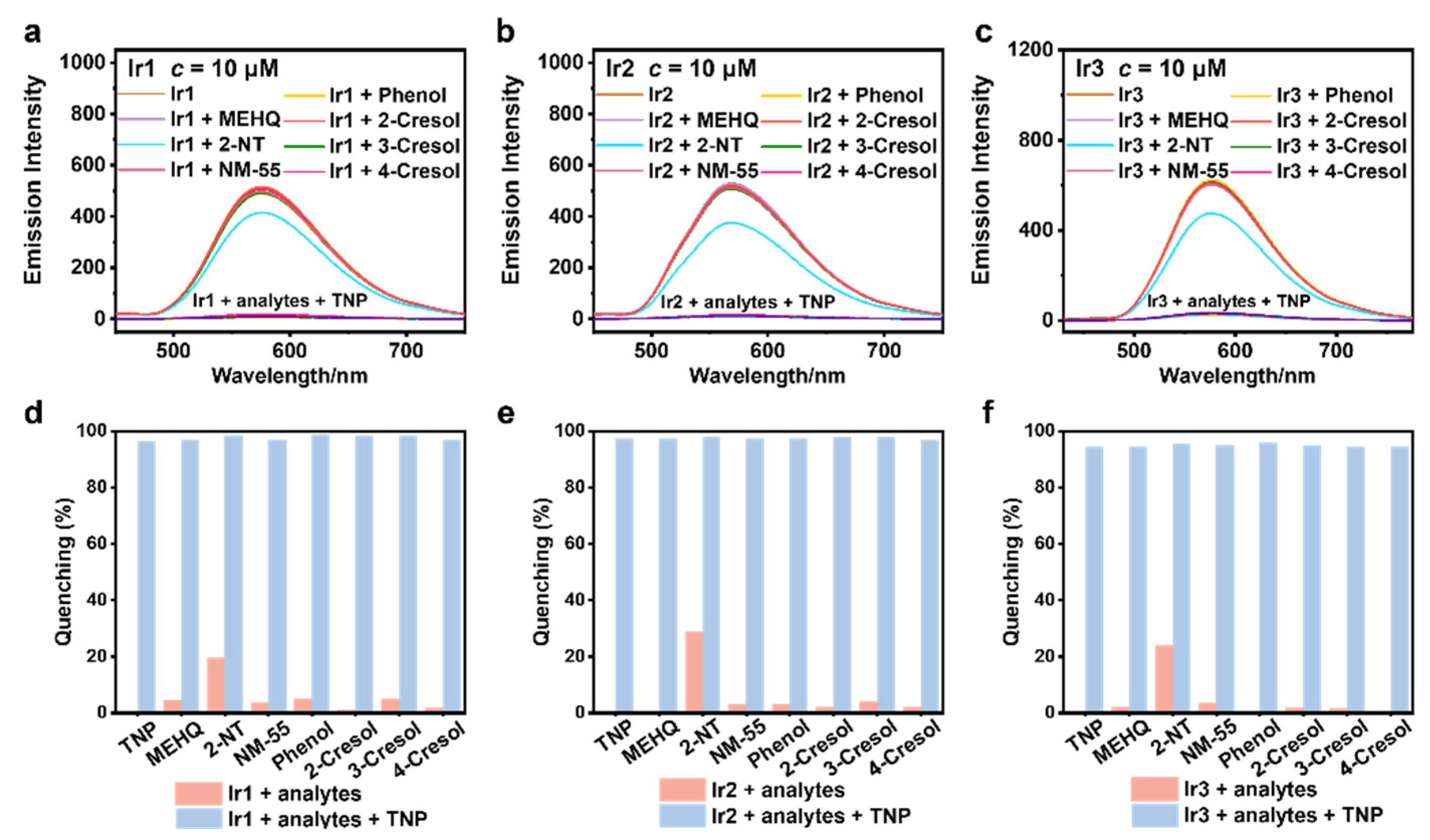

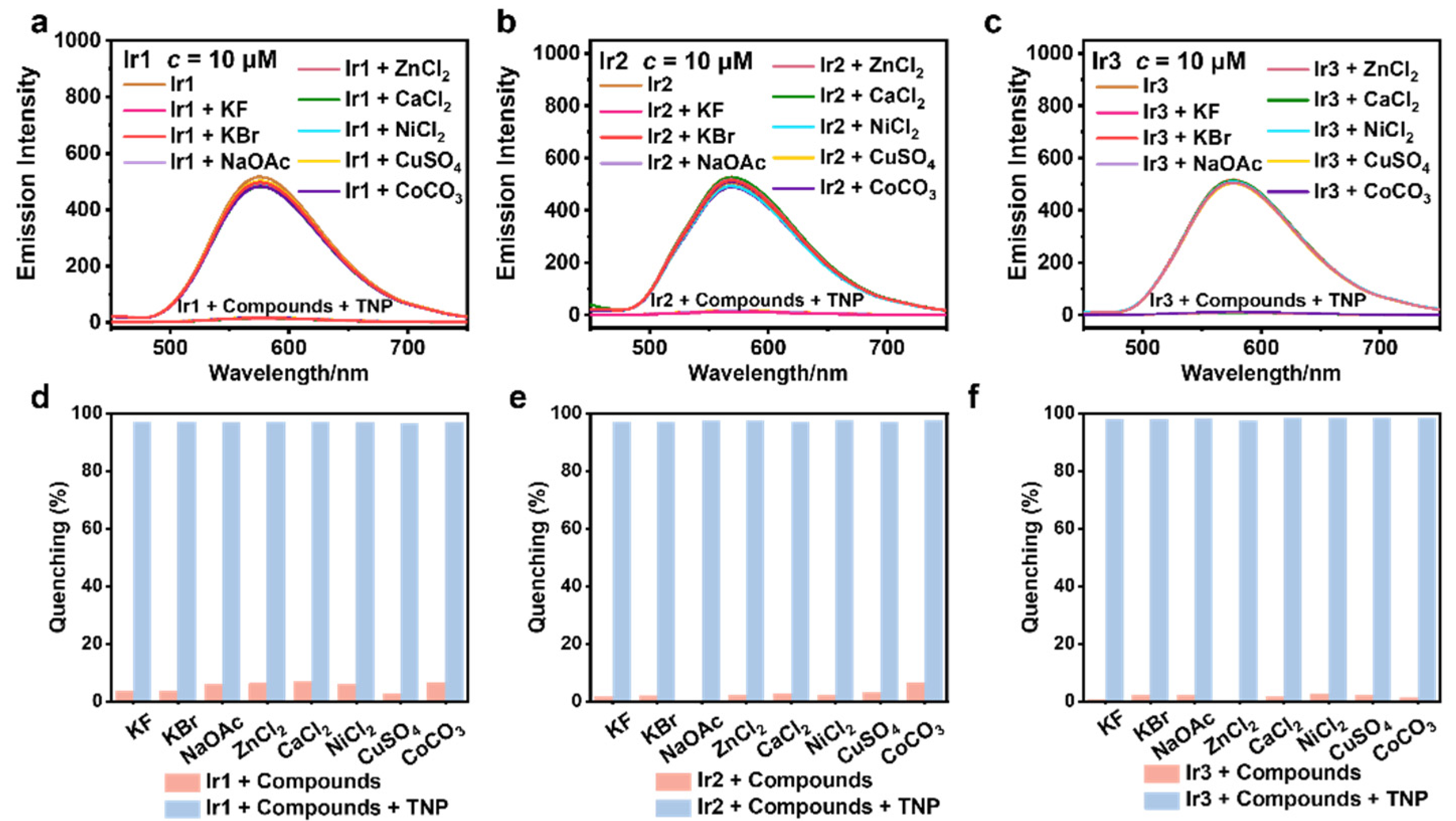

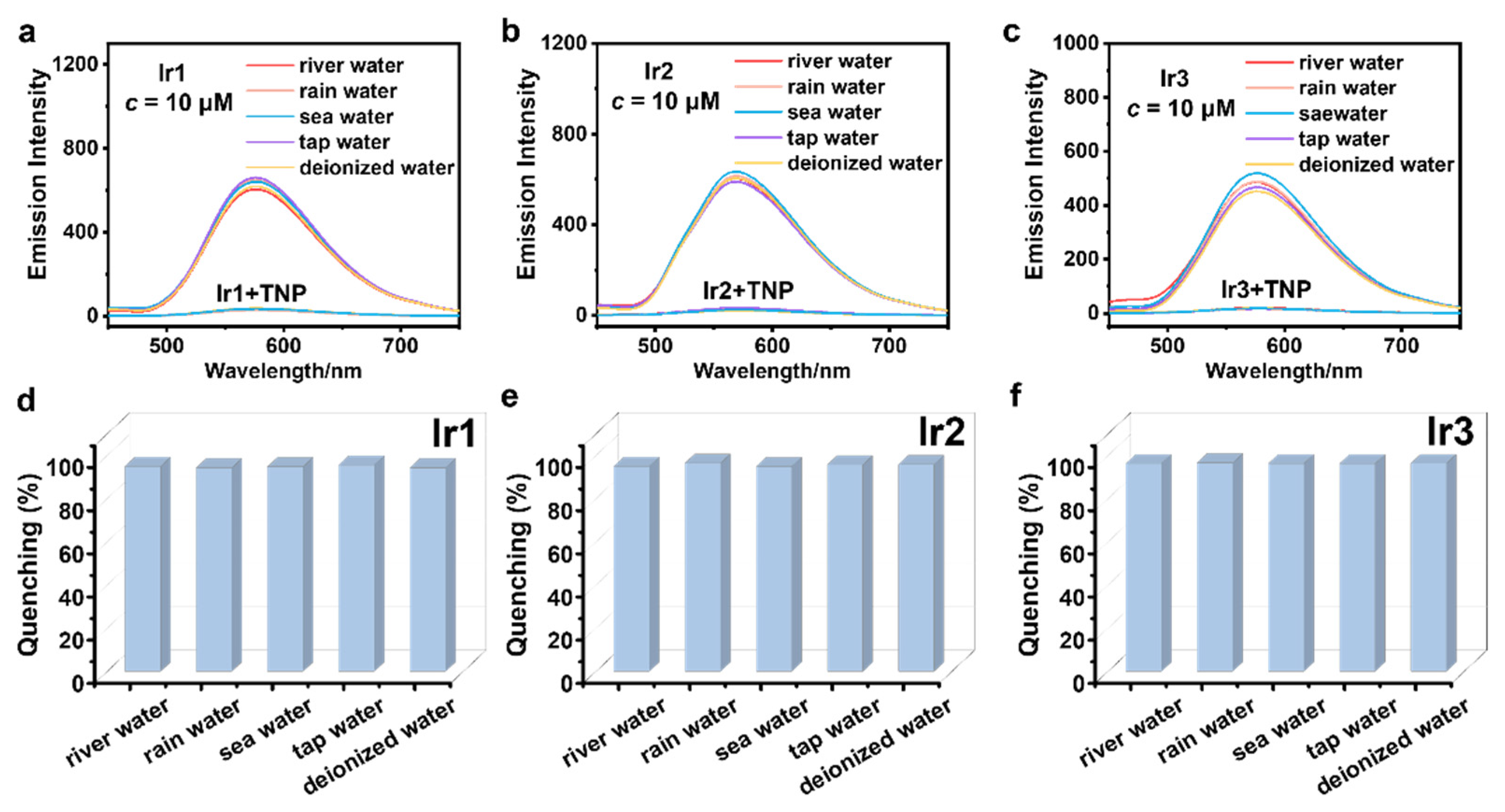

3.4. Selectivity and Anti-Interference Capability Experiments

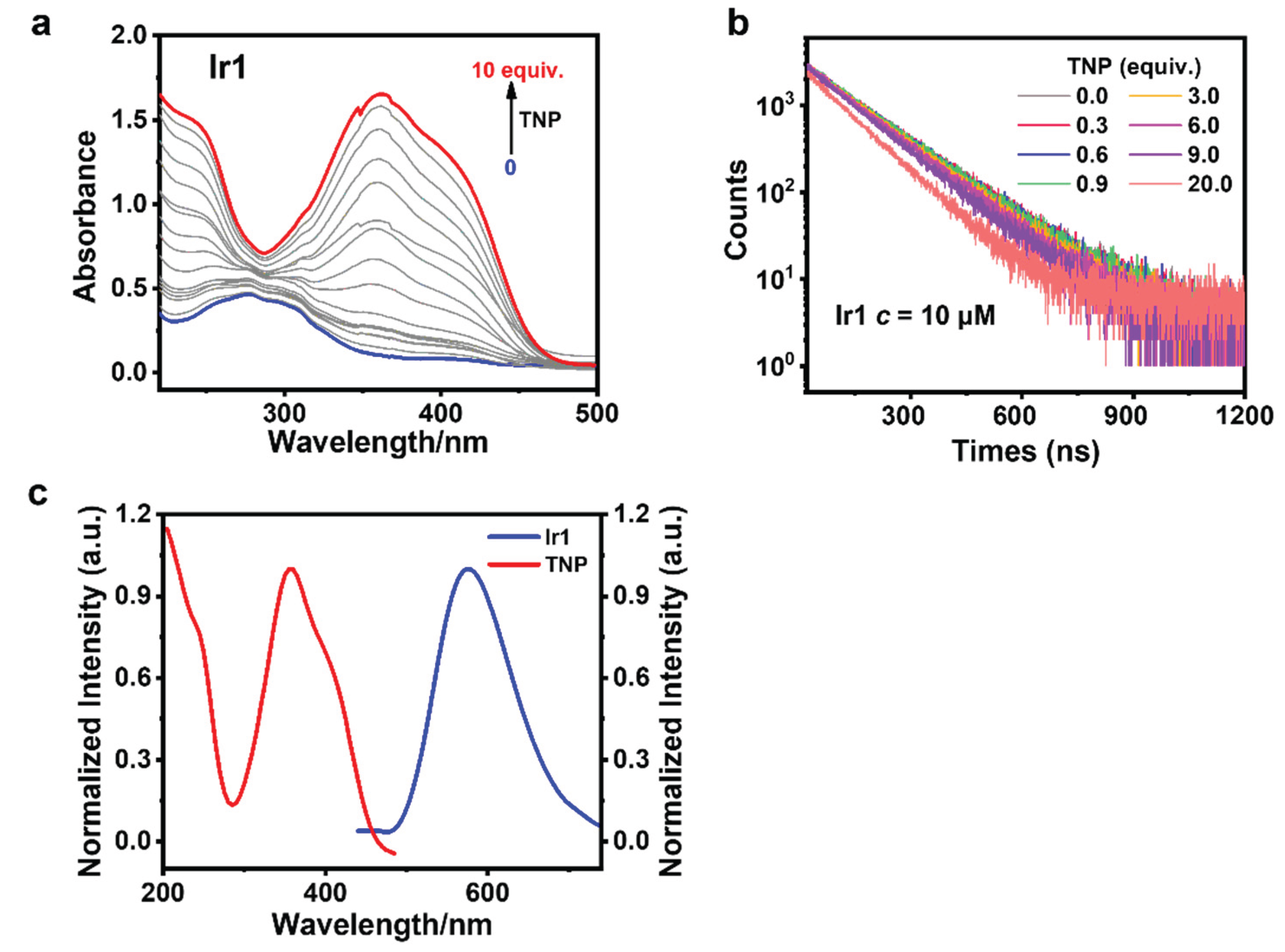

3.5. Sensing Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, J.D.; Xie, Z.L.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Cheng, L.; Chen, H.Y.; Qiu, C.F.; Kwok, H.S.; Zhan, X.W.; Liu, Y.Q.; Zhu, D.B. Aggregation-induced emission of 1-methyl-1,2,3,4,5-pentaphenylsilole. Chem. Commun. 2001, 18, 1740–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Chang, T.-K.; Ganesan, P.; Rajakannu, P. Emissive bis-tridentate Ir(III) metal complexes: Tactics, photophysics and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 346, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.N.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-induced emission. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 5361–5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naithani, S.; Goswami, T.; Thetiot, F.; Kumar, S. Imidazo [4,5-f] [1,10] phenanthroline based luminescent probes for anion recognition: Recent achievements and challenges. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 475, 214894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.-Y.; Feng, W.-W.; Liu, Q.-Y.; He, L.; Yao, D.-H.; He, Z.-D. Lipophilic neutral iridium(III) complexes for phosphorescence imaging of lipid droplets and potential photodynamic therapy. Dyes Pigm. 2022, 203, 110387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Fu, X.; Zhou, D.; Hu, R.; Qin, A.; Tang, B.Z. Smart aggregation-induced emission polymers: Preparation, properties and bio-applications. Smart Mol. 2023, 1, e20220008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manimaran, B.; Thanasekaran, P.; Rajendran, T.; Lin, R.J.; Chang, I.J.; Lee, G.H.; Peng, S.M.; Rajagopal, S.; Lu, K.L. Luminescence enhancement induced by aggregation of alkoxy-bridged rhenium(I) molecular rectangles. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 41, 5323–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.H.; Pan, H.H.; Li, L.; Liao, R.; Yu, S.Z.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, H.B.; Huang, W. AIPE-active platinum(ii) complexes with tunable photophysical properties and their application in constructing thermosensitive probes used for intracellular temperature imaging. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 7893–7899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, V.; Ramdass, A.; Thanasekaran, P.; Lu, K.L.; Rajagopal, S. Aggregation-induced phosphorescence enhancement (AIPE) based on transition metal complexes-An overview. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2015, 23, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro M, Cebrián C. Aggregation-induced phosphorescence enhancement in Ir(III) Complexes. Isr. J. Chem. 2018, 58, 901–914.

- Smith A R G, Burn P L, Powell B J. Spin-orbit coupling in phosphorescent Ir(III) Complexes. ChemPhysChem 2011, 12, 2428–2437.

- Jhun, B.H.; Song, D.; Park, S.Y.; You, Y. Phosphorescent Ir(III) complexes for biolabeling and biosensing. Top. Curr. Chem. 2022, 380, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao Q A, Liu S J, Huang W. Promising optoelectronic materials: Polymers containing phosphorescent Ir(III) complexes. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2010, 31, 794–807.

- Li, Y.Y.; Wu, Y.Q.; Wu, J.; Lun, W.C.; Zeng, H.; Fan, X.L. A near-infrared phosphorescent Ir(III) complex for fast and time-resolved detection of cysteine and homocysteine. Analyst 2020, 145, 2238–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.F.; Qi, H.T.; Peng, Y.J.; Qi, H.L.; Zhang, C.X. Rapid “turn-on” photoluminescence detection of bisulfite in wines and living cells with a formyl bearing bis-cyclometalated Ir(III) complex. Analyst 2018, 143, 3670–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.L.; Guo, H.R.; Liu, B.A.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, G.J.; Wu, Z.X.; Wong, W.Y. Diarylboron-based asymmetric red-emitting Ir(III) complex for solution-processed phosphorescent organic light-emitting diode with external quantum efficiency above 28%. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1701067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Din, I.U.D.; Raheel, A.; Din, A.T.U. Cyclometalated Ir(III) complexes: Recent advances in phosphorescence bioimaging and sensing applications. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 34, e5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M.R.; Guo, X.W.; Pfund, B.; Okamoto, Y.; Ward, T.R.; Kerzig, C.; Wenger, O.S. Water-soluble tris(cyclometalated) Ir(III) complexes for aqueous electron and energy transfer photochemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 1290–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, L.; Li, F.Y.; Yu, M.X.; Liu, Z.P.; Yi, T.; Huang, C.H. Aggregation-induced phosphorescent emission (AIPE) of iridium(III) complexes. Chem. Commun. 2008, 685–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.H.; Chen, J.F.; Feng, J.Q.; Hu, J.S.; Cao, D.K. Two heteroleptic Ir(III)-bisthienylethene compounds: Syntheses, structures and aggregation-induced luminescence. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 14359–14365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.C.; Shang, G.J.; Shi, J.B.; Zhi, J.G.; Tong, B.; Dong, Y.P. Effect of substituent position on the photophysical properties of triphenylpyrrole isomers. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 11658–11664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.L.; Gao, J.; Gao, Y.; Shan, G.G.; Geng, Y.; Shao, K.Z.; Su, Z.M. Constructing anion-π interactions in cationic iridium (III) complexes to achieve aggregation-induced emission properties. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thekkathu, R.; Ashok, D.; Ramkollath, P.K.; Neelakandapillai, S.; Kurishunkal, L.P.; Yadav, M.S.P.; Kalarikkal, N. Magnetically recoverable Ir/IrO2@Fe3O4 core/SiO2 shell catalyst for the reduction of organic pollutants in water. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 742, 137147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paziresh, S.; Aghakhanpour, R.B.; Shahsavari, H.R.; Dolatyari, V.; Ara, I.; Nabavizadeh, S.M. Phosphorescent cyclometalated Ir(III) complexes comprising chelating thiolate ligands as pH-activatable sensors. New J. Chem. 2023, 47, 1378–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.K.; Wang, J.; Yang, K.; Liu, J.B.; Ma, D.L.; Leung, C.H.; Wang, W.H. Development of a NIR iridium(III) complex for self-calibrated and luminogenic detection of boron trifluoride. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2022, 282, 121658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, T.M.; Ye, S.N.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. Conjugated microporous polymers-based fluorescein for fluorescence detection of 2,4,6-trinitrophenol. Talanta 2017, 165, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, E.; Aydin, M.; Gorur, M.; Gürek, A.G.; Yilmaz, F. Pyrene-functional star polymers as fluorescent probes for nitrophenolic compounds. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 46310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabin M, Lapkowski M, Jarosz T. Methods for detecting picric acid-a review of recent progress. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3991.

- Khan, I.; Shah, T.R.; Tariq, M.R.; Ahmad, M.; Zhang, B.L. Understanding the toxicity of trinitrophenol and promising decontamination strategies for its neutralization: Challenges and future perspectives. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.L.; Lu, Z.; Xie, Z.H.; Hou, L.X. Amphiphilic gemini-iridium (III) complex for rapid and selective detection of picric acid in water and intracellular. Talanta 2020, 208, 120372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, G.G.; Li, H.B.; Sun, H.Z.; Zhu, D.X.; Cao, H.T.; Su, Z.M. Controllable synthesis of iridium(III)-based aggregation-induced emission and/or piezochromic luminescence phosphors by simply adjusting the substitution on ancillary ligands. J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wen, L.L.; Shan, G.G.; Sun, H.Z.; Mao, H.T.; Zhang, M.; Su, Z.M. Di-/trinuclear cationic Ir(III) complexes: Design, synthesis and application for highly sensitive and selective detection of TNP in aqueous solution. Sens. Actuators B 2017, 244, 314–322. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.M.; Zhang, Q.L.; Zhang, L.Y.; Liu, C. A phenyl-modified aggregation-induced phosphorescent emission-active cationic Ru(II) complex for detecting picric acid in aqueous media. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.C.; Zhang, L.Y.; Shi, Y.S.; Liu, C. Carbazolyl-modified neutral Ir(III) complexes for efficient detection of picric acid in aqueous media. Sensors 2024, 24, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.Y.; Jia, W.H.; Zhang, L.Y.; Liu, C. Fluorophenyl-modified AIPE-active cationic Pt(II) complexes for detecting picric acid in aqueous media. Dyes Pigm. 2023, 220, 111719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Rao, X.F.; Song, X.L.; Qiu, J.S.; Jin, Z.L. Palladium-catalyzed ligand-free and aqueous Suzuki reaction for the construction of (hetero)aryl-substituted triphenylamine derivatives. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.J.; Deng, L.J.; Zhang, T.; Li, J.Y. Substituent effect on the photophysical properties, electrochemical properties and electroluminescence performance of orange-emitting iridium complexes. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 6833–6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toprak, M.; Aydin, B.M.; Arik, M.; Onganer, Y. Fluorescence quenching of fluorescein by Merocyanine 540 in liposomes. J. Lumin. 2011, 131, 2286–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Miller, E.K.; Moses, D.; Heeger, A.J. Static and dynamic photoluminescence (PL) quenching of polymer: Quencher systems in solutions. Synth. Met. 2001, 119, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciotta E, Prosposito P, Pizzoferrato R. Positive curvature in Stern-Volmer plot described by a generalized model for static quenching. J. Lumin. 2019, 206, 518–522.

- Zu, F.L.; Yan, F.Y.; Bai, Z.J.; Xu, J.X.; Wang, Y.Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Zhou, X.G. The quenching of the fluorescence of carbon dots: A review on mechanisms and applications. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 1899–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadomska, A.V.; Nevidimov, A.V.; Tovstun, S.A.; Petrova, O.V.; Sobenina, L.N.; Trofimov, B.A.; Razumov, V.F. Fluorescence from 3,5-diphenyl-8-CF3-BODIPYs with amino substituents on the phenyl rings: Quenching by aromatic molecules. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2021, 254, 119623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollett, G.; Roberts, D.S.; Sewell, M.; Wensley, E.; Wagner, J.; Murray, W.; Krotz, A.; Toth, B.; Vijayakumar, V.; Sailor, M.J. Quantum ensembles of silicon nanoparticles: Discrimination of static and dynamic photoluminescence quenching processes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 17976–17986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Complexes | Ir1 | Ir2 | Ir3 |

| λ/nm | 574 | 573 | 578 |

| X1 | 452.1 | 473.1 | 477.0 |

| X2 | 452.4 | 473.5 | 476.6 |

| X3 | 452.4 | 474.6 | 476.7 |

| X4 | 451.9 | 473.6 | 476.4 |

| X5 | 451.2 | 474.4 | 476.8 |

| X6 | 451.4 | 473.9 | 476.7 |

| X7 | 451.3 | 473.4 | 477.0 |

| X8 | 451.2 | 473.2 | 477.6 |

| X9 | 452.1 | 473.9 | 477.5 |

| X10 | 451.9 | 474.0 | 477.4 |

| X11 | 452.3 | 473.5 | 477.8 |

| σ | 0.4558 | 0.4518 | 0.4400 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).