Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

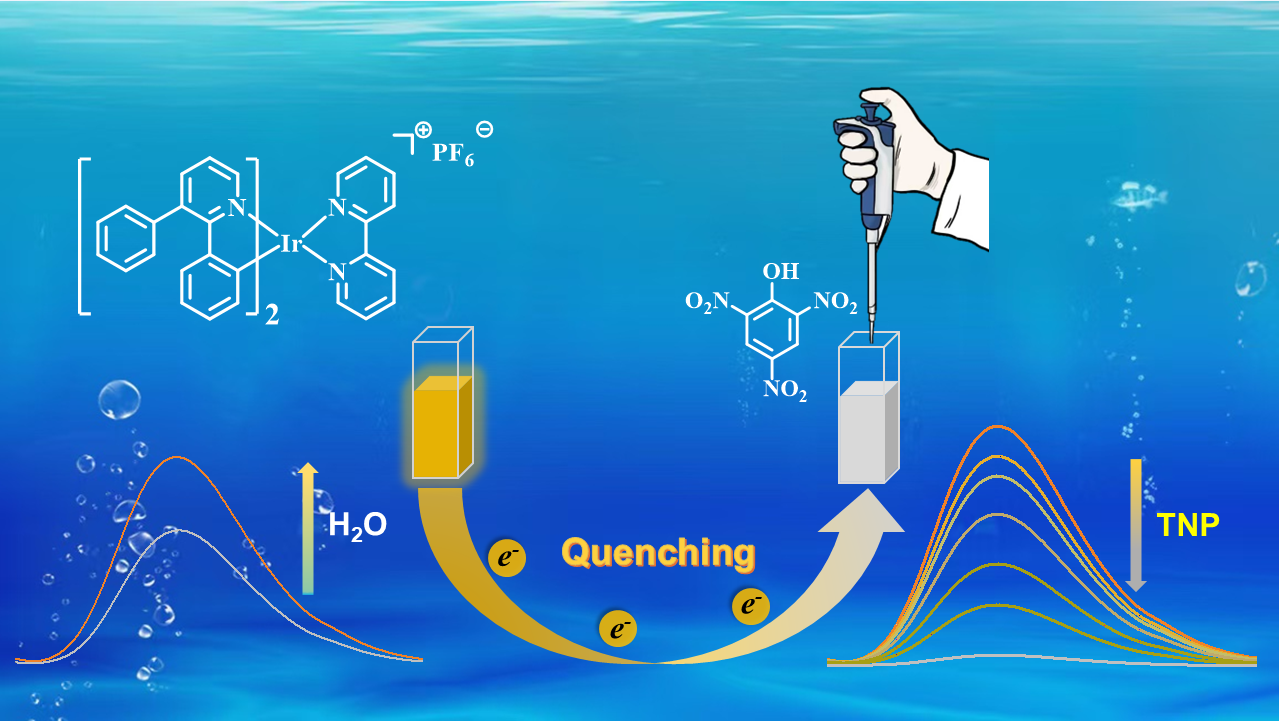

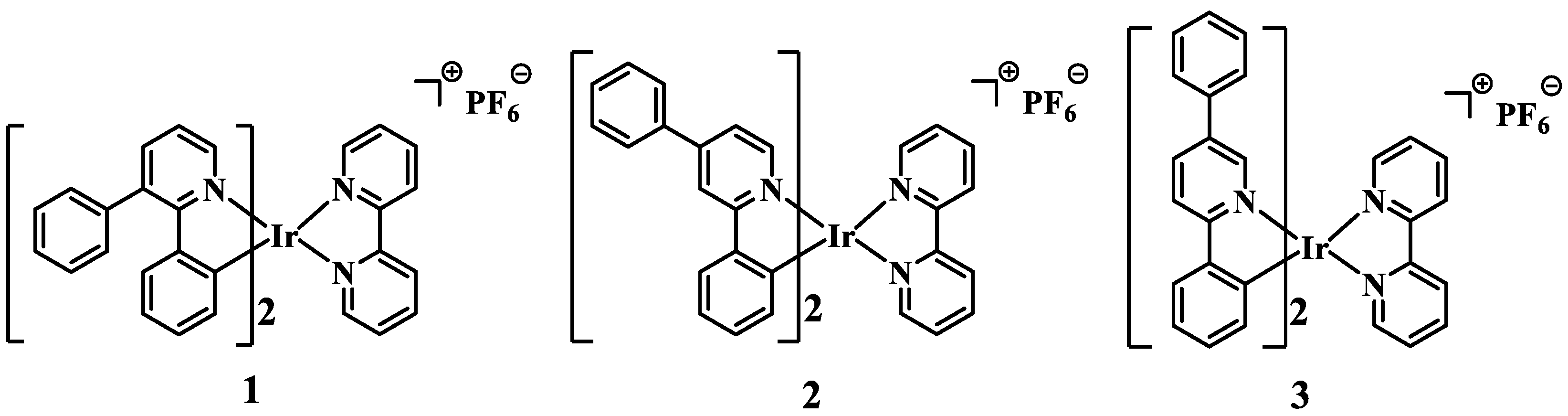

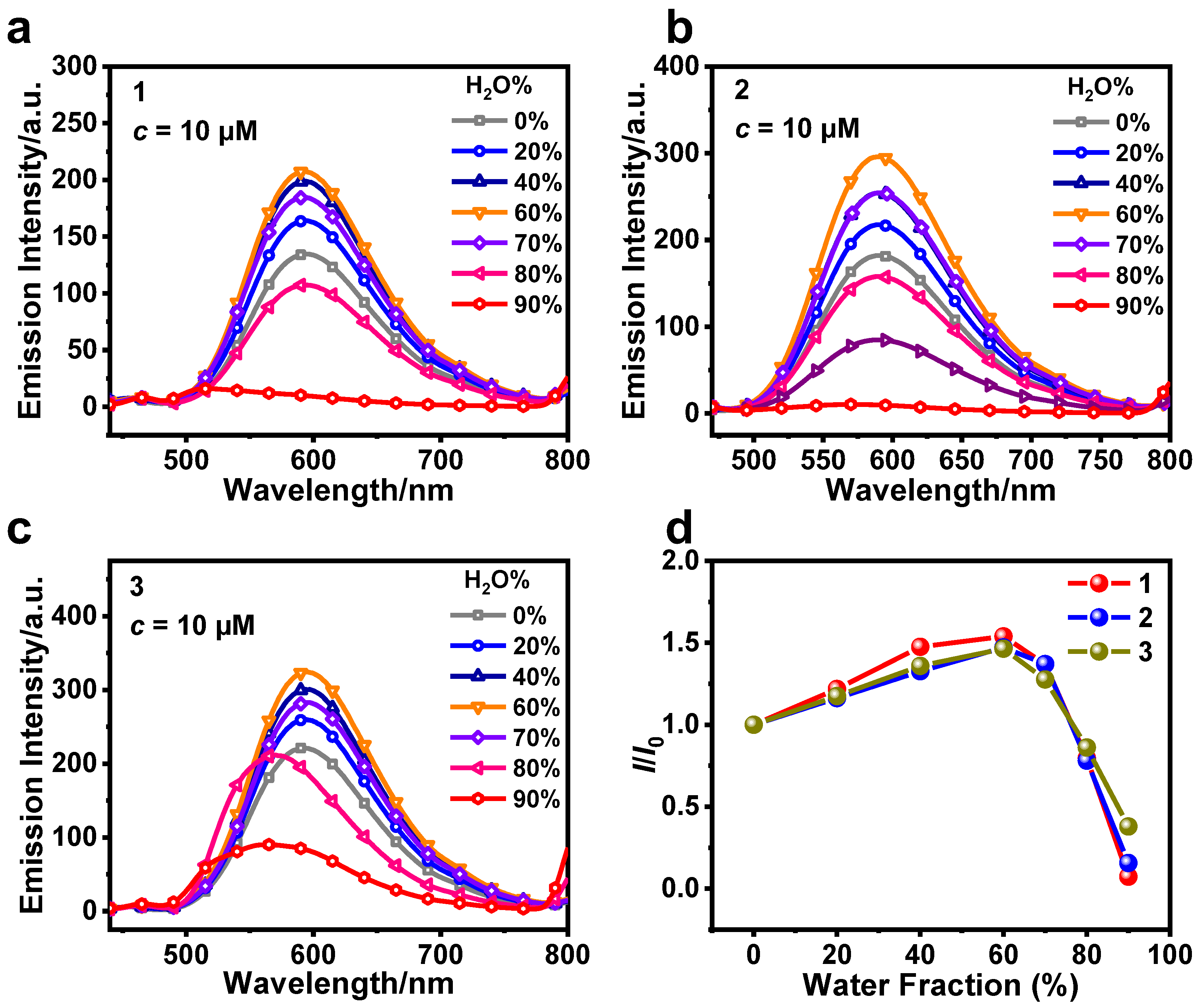

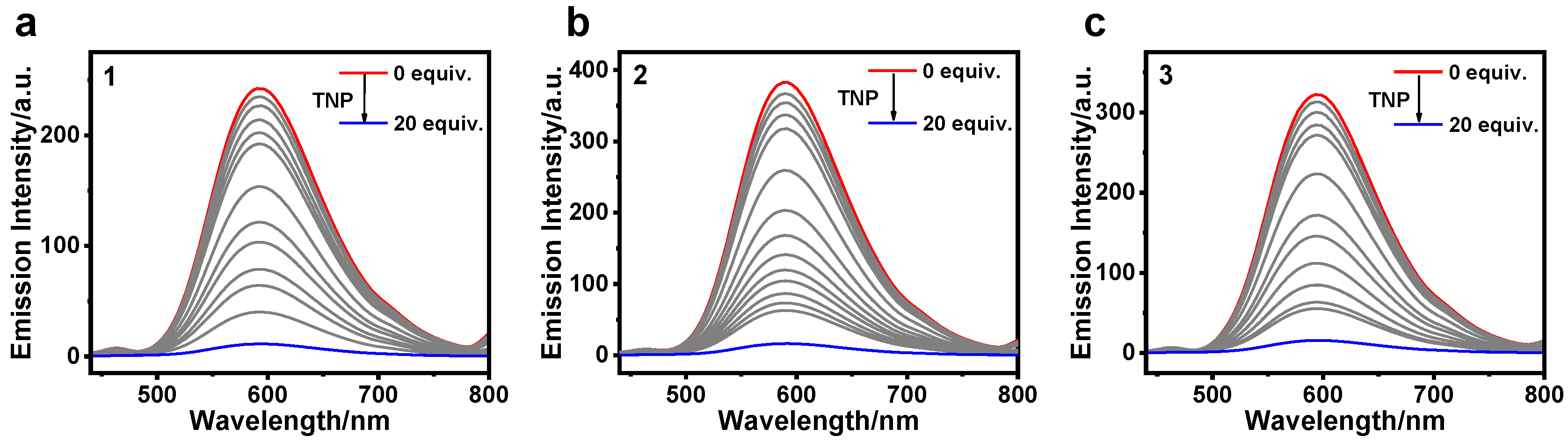

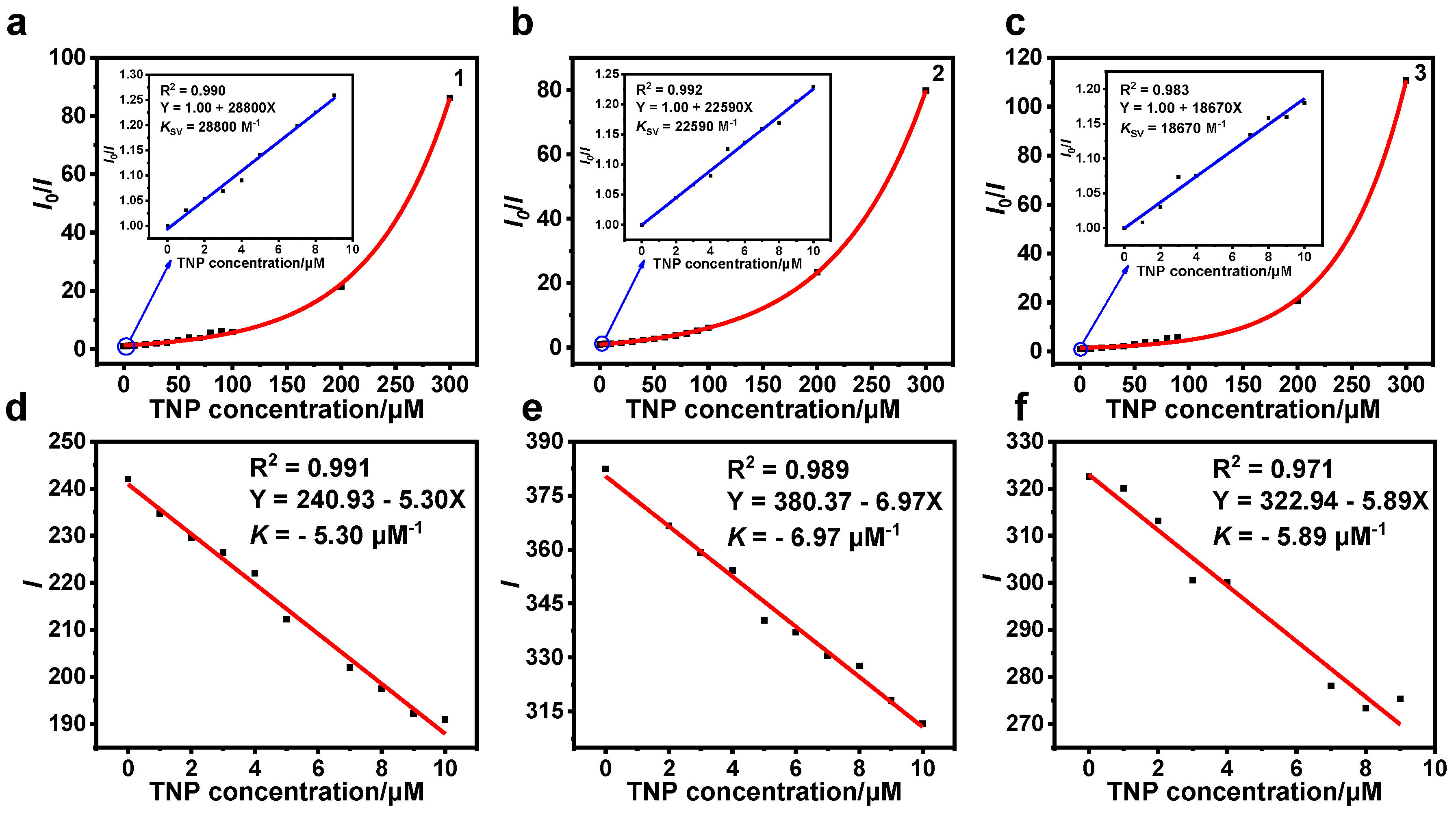

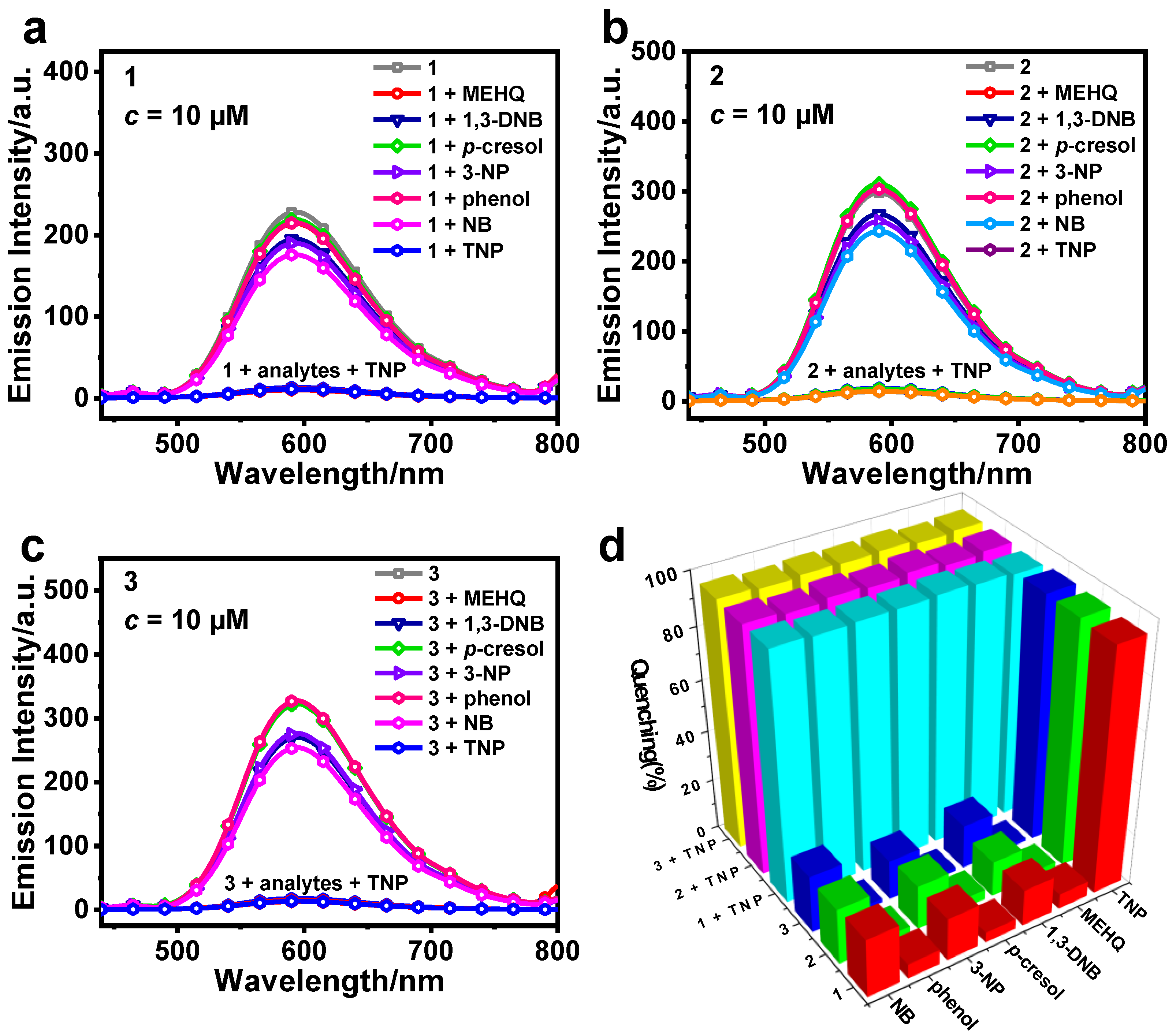

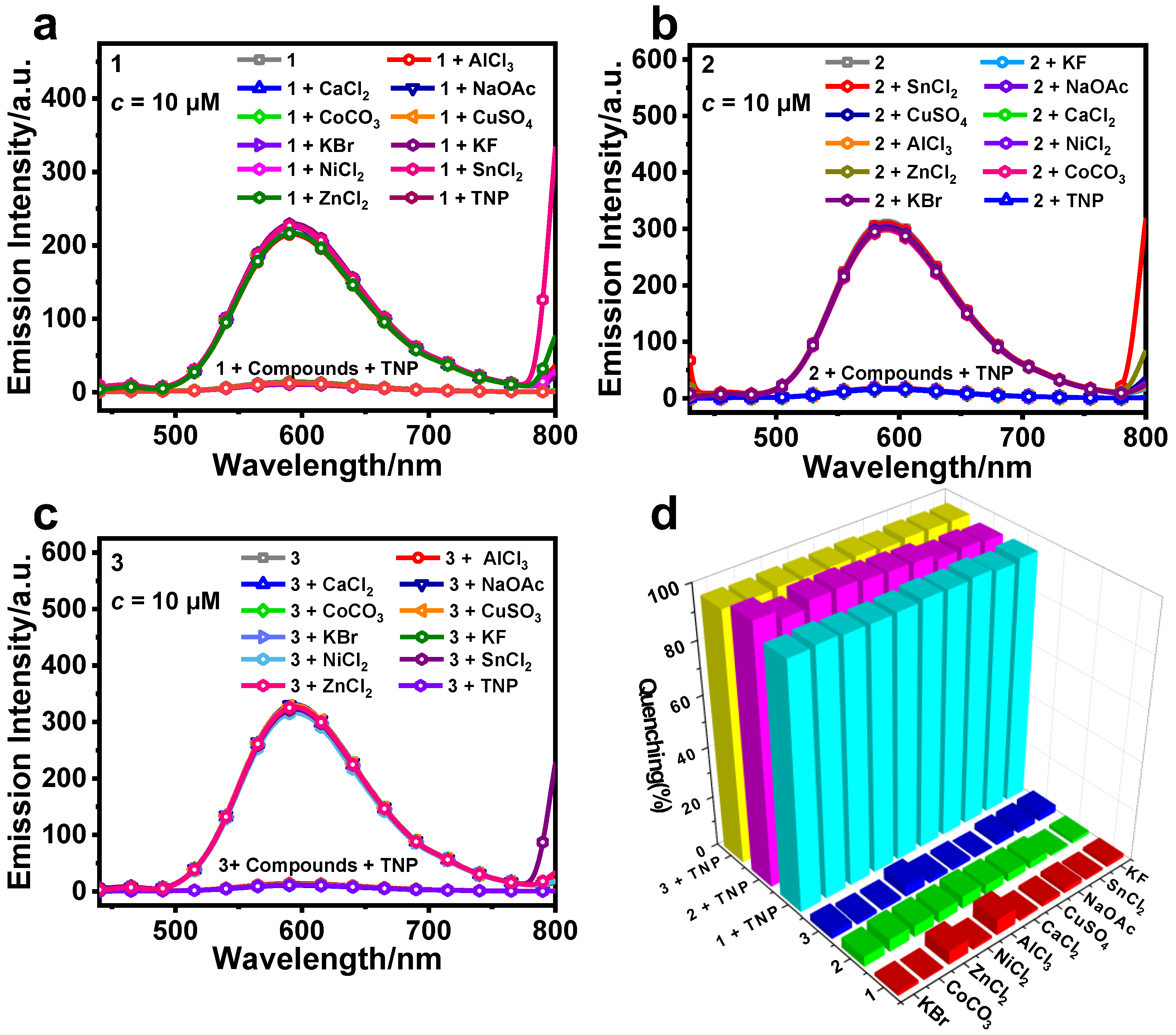

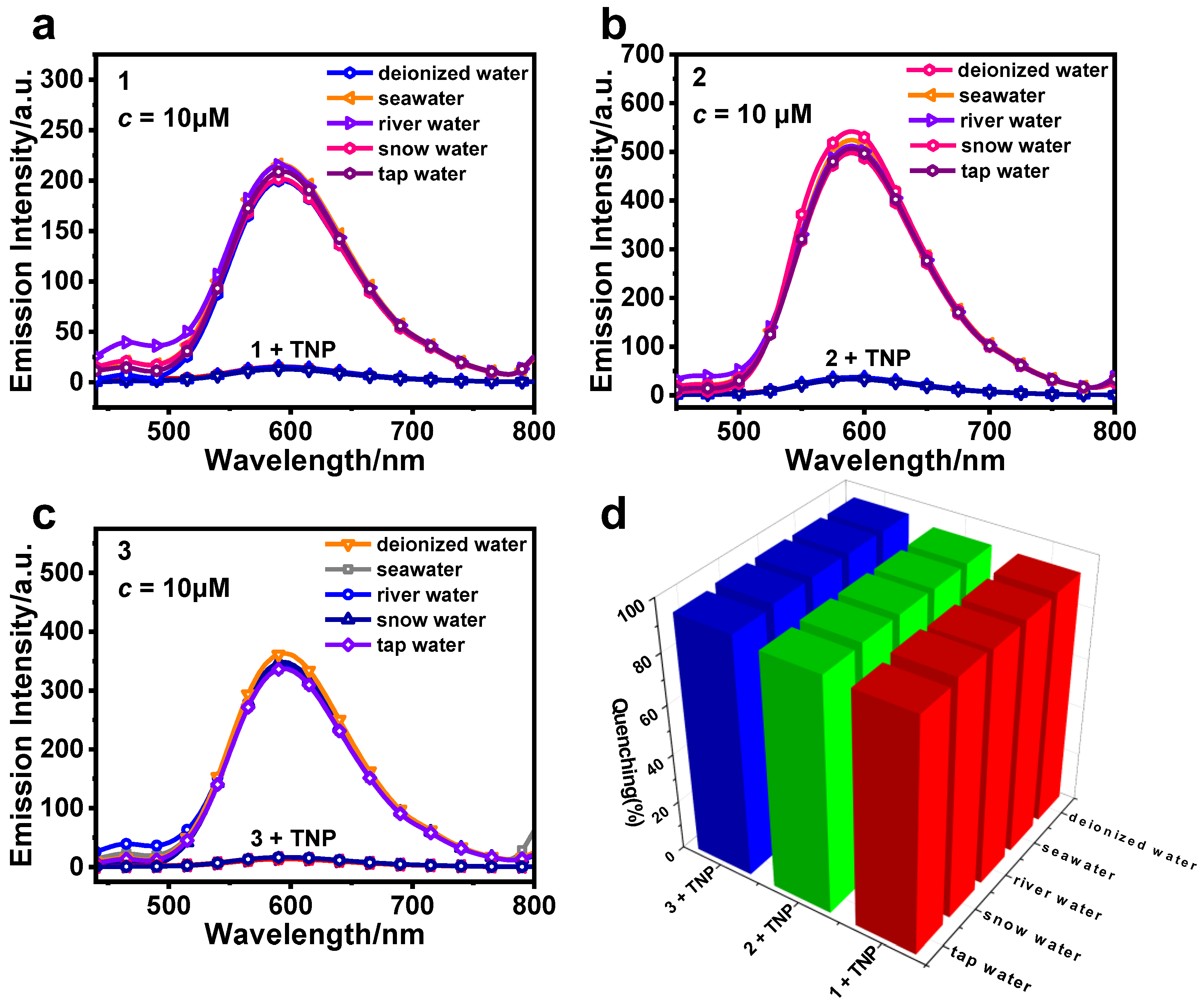

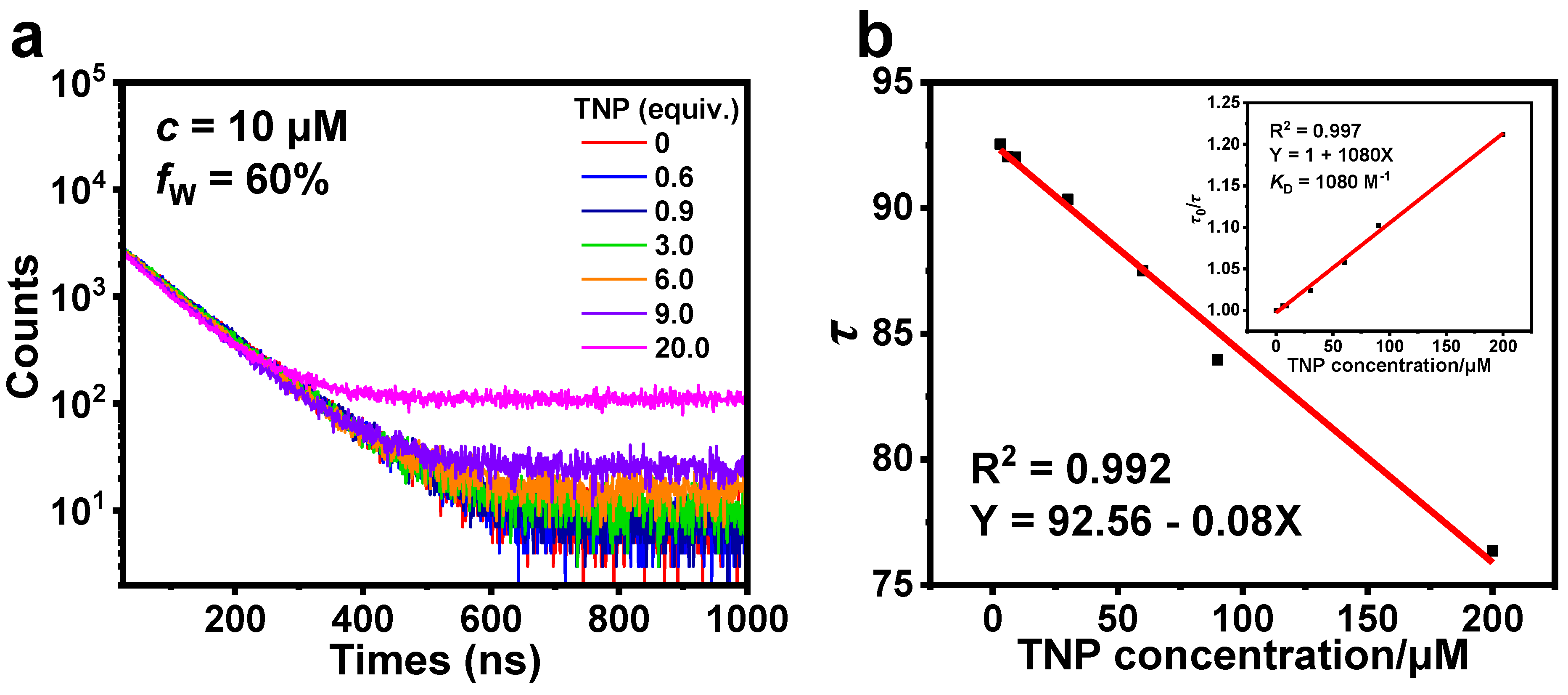

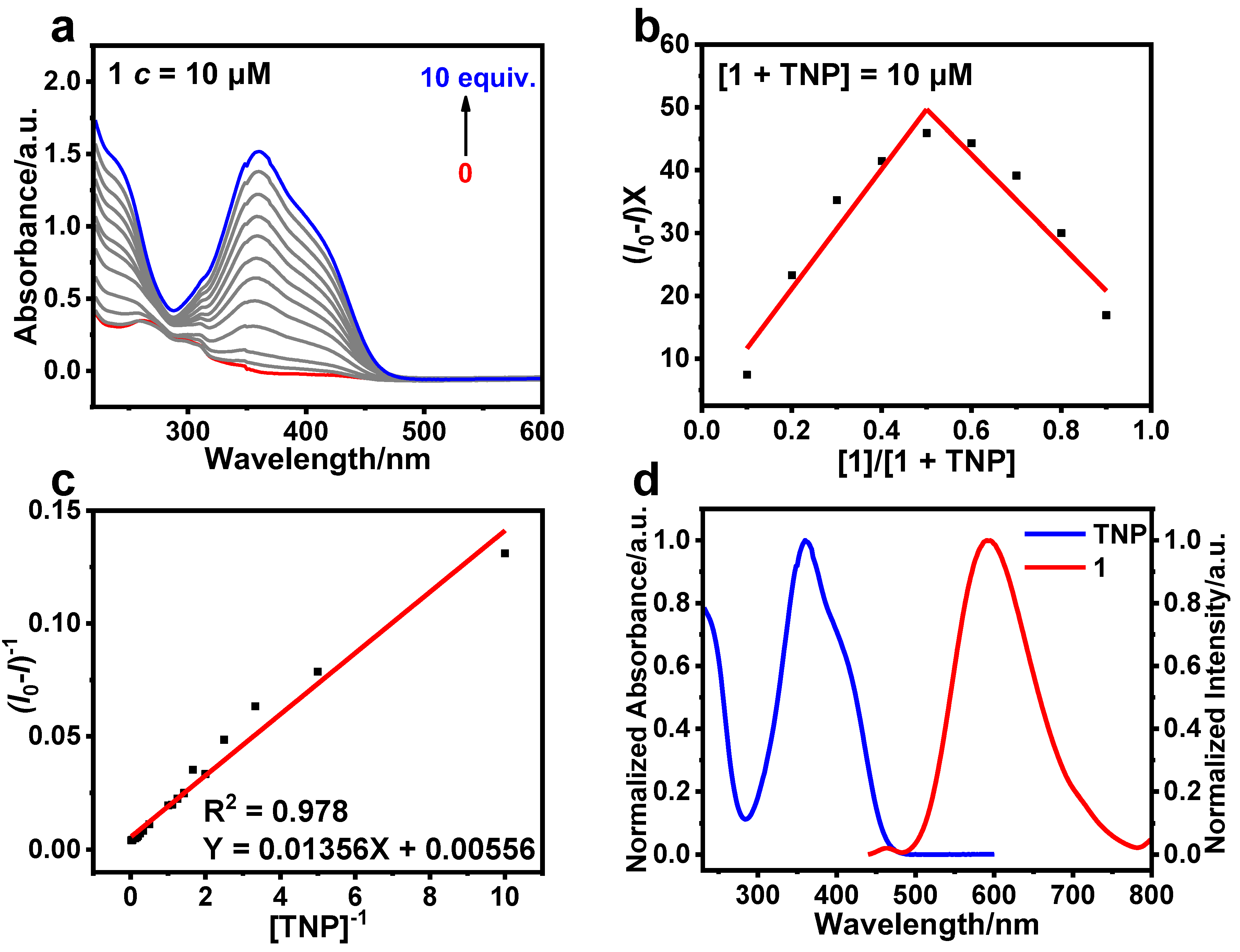

Three cationic Ir(III) complexes 1, 2, and 3 were successfully synthesized and characterized by tuning the position of a phenyl group at the pyridyl moiety in 2-phenylpyridine. All three complexes exhibit typical aggregation-induced phosphorescence emission (AIPE) properties in CH3CN/H2O. The AIPE property was further utilized to achieve highly sensitive detection of 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (TNP) in aqueous media with low limits of detection (LOD) of 164, 176, and 331 nM, respectively. This suggests that the different positions of the phenyl group influence the effectiveness of 1, 2, and 3 in the detection of TNP. In addition, 1, 2, and 3 showed superior selectivity and anti-interference for the detection of TNP and the potential to detect TNP in practical applications. Taking 1 as an example, the changes in the luminescent lifetime and UV-Vis absorption spectra of 1 before and after the addition of TNP, indicate that the quenching process is a combination of static and dynamic quenching. Additionally, the proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectra and spectral studies show that the detection mechanism is photo-induced electron transfer (PET).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

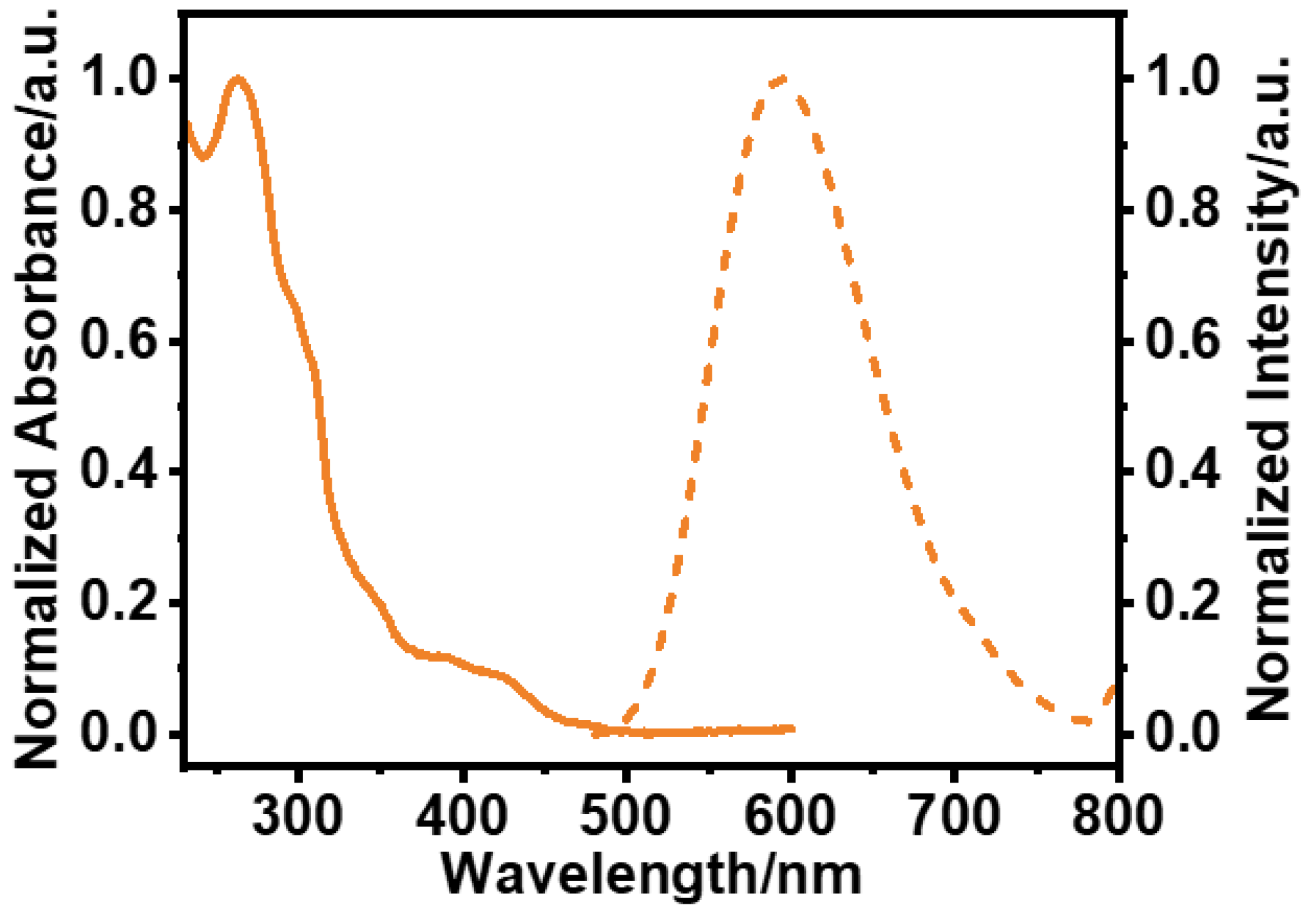

3.1. Photophysical and AIPE Properties

3.2. Detection of TNP

3.3. Sensing Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agarwal, A.; Bhatta, R.P.; Kachwal, V.; Laskar, I.R. Controlling the sensitivity and selectivity for the detection of nitro-based explosives by modulating the electronic substituents on the ligand of AIPE-active cyclometalated iridium(<sc>iii</sc>) complexes. Dalton Transactions 2023, 52, 14182–14193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Qiu, L.-G.; Yuan, Y.-P.; Xie, A.-J.; Shen, Y.-H.; Zhu, J.-F. Microwave-assisted synthesis of highly fluorescent nanoparticles of a melamine-based porous covalent organic framework for trace-level detection of nitroaromatic explosives. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2012, 221-222, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, Q. A highly sensitive and selective chemosensor for 2,4,6-trinitrophenol based on L-cysteine-coated cadmium sulfide quantum dots. Talanta 2019, 198, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Peng, H.N.; Liu, T.H.; Yang, M.N.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y. A novel picric acid film sensor <i>via</i> combination of the surface enrichment effect of chitosan films and the aggregation-induced emission effect of siloles. JOURNAL OF MATERIALS CHEMISTRY 2009, 19, 7347–7353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, D.T.; Cooper, K.R.; Goodfellow, W.L.; Rosenblatt, D.H. Uptake, elimination, and metabolism of14C-picric acid and14C-picramic acid in the American oyster (Crassostrea virginica). Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 1984, 13, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, E.G.; Burlinson, N.E. Migration of explosives in soil: analysis of rdx, tnt, and tetryl from a 14c lysimeter study. Journal of Energetic Materials 1988, 6, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, P.G.; Jenkins, T.F. A field method for quantifying ammonium picrate and picric acid in soil. Field Analytical Chemistry & Technology 1997, 1, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, J.F.; Serve, M.P.; Hobson, D.W.; Lee, L.H.; Uddin, D.E. Acute toxicity, distribution, and metabolism of 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (picric acid) in Fischer 344 rats. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health 1992, 37, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.S. Instrumentation for trace detection of high explosives. Review of Scientific Instruments 2004, 75, 2499–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvia, J.M.; Janni, J.A.; Klein, J.D.; Spencer, K.M. Surface-Enhanced Raman Detection of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene Impurity Vapor as a Marker To Locate Landmines. Analytical Chemistry 2000, 72, 5834–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakonen, A.; Andersson, P.O.; Stenbæk Schmidt, M.; Rindzevicius, T.; Käll, M. Explosive and chemical threat detection by surface-enhanced Raman scattering: A review. Analytica Chimica Acta 2015, 893, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krausa, M.; Schorb, K. Trace detection of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene in the gaseous phase by cyclic voltammetry1Dedicated to Professor W. Vielstich on the occasion of his 75th birthday.1. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 1999, 461, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, X.; Chen, W. Recent advances in electrochemical sensors for the detection of 2, 4, 6-trinitrotoluene. Current Opinion in Electrochemistry 2019, 17, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Lei, Y. Fluorescence based explosive detection: from mechanisms to sensory materials. Chemical Society Reviews 2015, 44, 8019–8061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hang, H.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Tong, H.; Wang, L. Water-dispersible hyperbranched conjugated polymer nanoparticles with sulfonate terminal groups for amplified fluorescence sensing of trace TNT in aqueous solution. Materials Chemistry Frontiers 2017, 1, 1875–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, P.D.; Prata, J.V. Fluorescent Calix[4]arene-Carbazole-Containing Polymers as Sensors for Nitroaromatic Explosives. In Chemosensors, 2020; Vol. 8.

- Luo, J.; Xie, Z.; Lam, J.W.; Cheng, L.; Chen, H.; Qiu, C.; Kwok, H.S.; Zhan, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, D.; et al. Aggregation-induced emission of 1-methyl-1,2,3,4,5-pentaphenylsilole. Chemical communications (Cambridge, England), 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Xu, R. AIE luminogen functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles as efficient fluorescent sensor for explosives detection in water. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2014, 196, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yu, R.-H.; Shi, C.-M.; Tao, F.-R.; Li, T.-D.; Cui, Y.-Z. Electrospun nanofibrous membrane based on AIE-active compound for detecting picric acid in aqueous solution. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2018, 262, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Kong, L.; Tian, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J. AIE-active luminogen for highly sensitive and selective detection of picric acid in water samples: Pyridyl as an effective recognition group. Dyes and Pigments 2019, 163, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Leung, N.L.C.; Kwok, R.T.K.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-Induced Emission: Together We Shine, United We Soar! Chemical Reviews 2015, 115, 11718–11940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manimaran, B.; Thanasekaran, P.; Rajendran, T.; Lin, R.J.; Chang, I.J.; Lee, G.H.; Peng, S.M.; Rajagopal, S.; Lu, K.L. Luminescence enhancement induced by aggregation of alkoxy-bridged rhenium(I) molecular rectangles. Inorganic Chemistry 2002, 41, 5323–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Liu, C. Carbazolyl-Modified Neutral Ir(III) Complexes for Efficient Detection of Picric Acid in Aqueous Media. In Sensors, 2024; Vol. 24.

- He, P.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.-N.; Yan, Y.-Y.; Liu, C. Aggregation-Induced Emission-Active Iridium(III) Complexes for Sensing Picric Acid in Water. In Chemosensors, 2023; Vol. 11.

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, X.; MacMillan, D.W.C. Decarboxylative sp3 C–N coupling via dual copper and photoredox catalysis. Nature 2018, 559, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yung, T.-L.; Cheng, S.-S.; Chen, F.; Liu, J.-B.; Leung, C.-H.; Ma, D.-L. A long-lived luminogenic iridium(III) complex for acetylacetone detection in environmental samples. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2020, 321, 128486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Han, M.P.; Chen, R.Z.; Zhuang, Y.L.; Zou, L.; Liu, S.J.; Huang, W.; Zhao, Q. Mitochondria-localized iridium(III) complexes with anthraquinone groups as effective photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy under hypoxia. SCIENCE CHINA-CHEMISTRY 2019, 62, 1639–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.-N.; Yan, Y.-Y.; Liu, C. AIPE-active cationic Ir(iii) complexes for efficient detection of 2,4,6-trinitrophenol and oxygen. Dalton Transactions 2023, 52, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, L.; Xing, Y.; Yang, Z.; Qiao, C.; Xia, Z. Photostable aggregation-induced emission of iridium(III) complex realizing robust and high-resolution imaging of latent fingerprints. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2023, 375, 132898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J. The influence of different cyclometalated ligand substituents and ancillary ligand on the phosphorescent properties of iridium(III) complexes. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2016, 177, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.-H.; Park, H.J.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, H.U.; Hwang, D.-H. Orange phosphorescent Ir(III) complexes consisting of substituted 2-phenylbenzothiazole for solution-processed organic light-emitting diodes. Organic Electronics 2018, 60, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, H.; Wang, X.; Qi, H. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence from Heteroleptic Iridium(III) Complexes with Multicolor Emission. Inorganic Chemistry 2015, 54, 1446–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zhou, K.; Li, M.; Sun, H.; Chen, Y.; Su, S.; Pu, X.; Huang, Y.; Lu, Z. Iridium(iii) complexes with enhanced film amorphism as guests for efficient orange solution-processed single-layer PhOLEDs with low efficiency roll-off. Dalton Transactions 2013, 42, 10559–10571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, A.; Tian, Y.; Wang, X.; Gong, D.; Guo, Y.; Iqbal, K.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W.; Qin, W. Carbon dots prepared by solid state method via citric acid and 1,10-phenanthroline for selective and sensing detection of Fe2+ and Fe3+. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2016, 237, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, F.; Yan, F.; Bai, Z.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, X. The quenching of the fluorescence of carbon dots: A review on mechanisms and applications. Microchimica Acta 2017, 184, 1899–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Maity, A.; Shyamal, M.; Maity, S.; Mudi, N.; Misra, A. Aggregation induced emission of 9-Anthraldehyde microstructures and its selective sensing behavior towards picric acid. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2018, 261, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Li, W.; Pi, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Li, P.; Jiang, X. Trace amounts of mercaptans with key roles in forming an efficient three-component photoinitiation system for holography. Materials Today Chemistry 2022, 26, 100999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Che, G. Diphenyl imidazole-based supramolecular self-assembly system for an efficient fluorometric detection of picric acid. Dyes and Pigments 2022, 203, 110378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuk Elmas, S.N.; Karagoz, A.; Arslan, F.N.; Yilmaz, I. Propylimidazole Functionalized Coumarin Derivative as Dual Responsive Fluorescent Chemoprobe for Picric Acid and Fe3+ Recognition: DFT and Natural Spring Water Applications. Journal of Fluorescence 2022, 32, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P, K.; Cherian, A.R.; Sirimahachai, U.; Thadathil, D.A.; Varghese, A.; Hegde, G. Detection of picric acid in industrial effluents using multifunctional green fluorescent B/N-carbon quantum dots. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, 107209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, D. Revising Intramolecular Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET) from First-Principles. Accounts of Chemical Research 2016, 49, 1816–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).