1. Introduction

In the context of university public administration, procurement planning is a critical step in ensuring the efficient use of resources, institutional transparency, and the achievement of strategic goals. In Peru, the regulatory framework governed by Law No. 30225 and its amendment, Law No. 32069, establishes planning as the cornerstone of the Annual Procurement Plan (PAC), requiring its periodic review and alignment with institutional objectives. However, multiple reports from the Comptroller General of the Republic (CGR) and the Supervisory Agency for State Procurement (OSCE) reveal persistent weaknesses in this phase, such as errors in the formulation of requirements, poor evaluation of suppliers, and poor alignment with international standards such as those proposed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), and Sustainable Procurement Guidelines (ISO 20400).

In the case of the National University of Huancavelica (UNH), located in a historically vulnerable region of Peru, these weaknesses are exacerbated by structural limitations, high staff turnover, limited use of digital tools, and an organizational culture with little focus on results. Despite modernization efforts, planning is predominantly formalistic, with limited predictive capacity and weak institutionalization of evaluation and monitoring processes.

International scientific literature offers various theoretical frameworks that allow these challenges to be addressed from an integrative perspective. Theories such as New Public Management, Public Value, and Agency Theory provide foundations for efficiency, legitimacy, and control in public procurement. Complementarily, approaches such as the Triple Helix, the JD-R Model, and Neural Networks applied to sustainability allow for the analysis of cultural, technological, and adaptive factors that influence institutional planning. However, there is a significant gap in the empirical application of these frameworks to the context of public universities in peripheral regions of Latin America, particularly with regard to the relationship between planning, operational efficiency, and transparency.

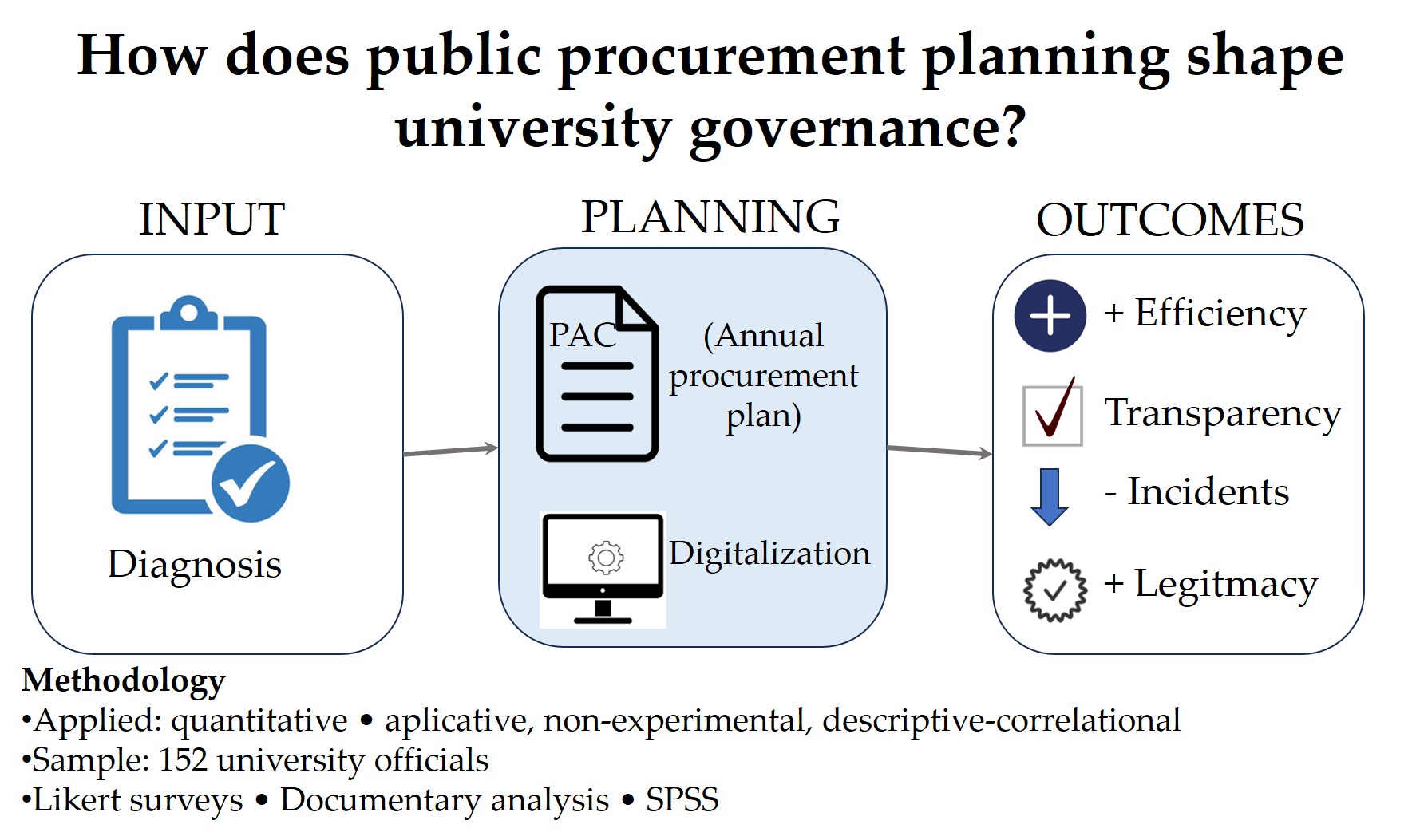

Consequently, this research is proposed as an applied, descriptive, and correlational study that analyzes the level of planning in public procurement at decentralized universities and its relationship with institutional efficiency and transparency between 2019 and 2024. Through structured surveys of 152 officials, documentary analysis of contractual files, and regulatory comparison with international standards, the study seeks to identify critical weaknesses, evidence of improvement, and opportunities to strengthen university management through a strategic and integrated approach. The study not only provides empirical evidence from a highly vulnerable institutional environment, but also proposes a set of recommendations aligned with principles of value for money, sustainability, and university public governance.

1.1. Empirical Reality in Management

In [

1], the challenges of multidisciplinary collaborative learning in higher education were investigated through a virtual course based on action research, under principles of pedagogical design in hybrid environments. The study, conducted at the University of Oulu (Finland), identified that the combination of teamwork and knowledge creation in virtual environments requires flexible pedagogical designs focused on interaction and continuous reflection. This theoretical framework supports the importance of adapting active methodologies in university contexts with face-to-face limitations.

In [

2], adaptation strategies in the face of threats are analyzed under the Theory of Reflexivity in Risk Management, using surveys and focus groups in Russia. Based on Weber's distinction between “positive/negative privilege” and Sztompka's theory of trust, the authors demonstrated that risk perception generates social stratification (beneficiaries vs. excluded). This approach is relevant for studying how public institutions manage risks in procurement, especially in contexts with high institutional mistrust.

In [

3], the authors developed a theoretical-practical framework on organizational competencies in university teachers (University of Samara, Russia). Based on surveys of 280 experts, they concluded that efficiency in educational management depends on skills such as strategic planning and adaptability. This theoretical approach supports the need to train public managers with equivalent skills to improve contractual processes.

The international push for neoliberal policies on higher education systems has generally tended to reduce government control over university operations, in exchange for these institutions taking on greater responsibility for generating their own income and providing quantitative evidence of their performance [

4].

The study conducted by [

5], is an empirical analysis of the public procurement system in Serbia, using data from the National Public Procurement Portal and evaluating 56 government entities. The results show that efficiency and transparency in procurement procedures are strongly influenced by the technical training of staff, the implementation of electronic platforms, regulatory consistency, and institutional control mechanisms. This empirical evidence can be extrapolated to university environments located in decentralized regions, where public procurement governance requires a robust technical foundation, systematic monitoring processes, and effective alignment with international standards of integrity and efficiency.

In the context of university governance, transparency in public procurement processes is a fundamental pillar for strengthening institutional legitimacy. As the authors of [

6], point out, improving access to procurement data through open publication contributes to a more informed public debate and enables communities to tackle corruption. This perspective reinforces the need to adopt digital oversight and accountability mechanisms as part of good practice in contract planning.

According to [

7], they investigated the use of ICT for independent work by students in English for Specific Purposes (ESP) courses at the National University of Commerce and Economics in Kiev (Ukraine). Using a SWOT analysis, they identified that, although online resources are valuable, students face challenges such as lack of self-discipline and communication gaps. This study reinforces the need to integrate digital tools with pedagogical strategies that promote autonomy and effective monitoring.

Meanwhile, [

8] conducted a qualitative-interpretive analysis of the ethical, pedagogical, and social implications of the use of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) in higher education. The study emphasizes the need for context-sensitive regulatory frameworks to avoid the reproduction of biases and preserve academic equity. This theoretical framework reinforces the urgency of basing all institutional innovation—including public procurement management—on critical evidence, participatory approaches, and sound ethical principles.

However, [

9] through an international empirical study published in PLOS ONE, analyzed the challenges of reconciling elite sport with higher education. They identified that the main barrier perceived by student-athletes is time management, followed by the lack of institutional support structures. Their findings highlight the need to implement flexible university programs that allow for balancing academic performance with athletic demands, which can be extrapolated to policies that integrate administrative efficiency and well-being in the university environment.

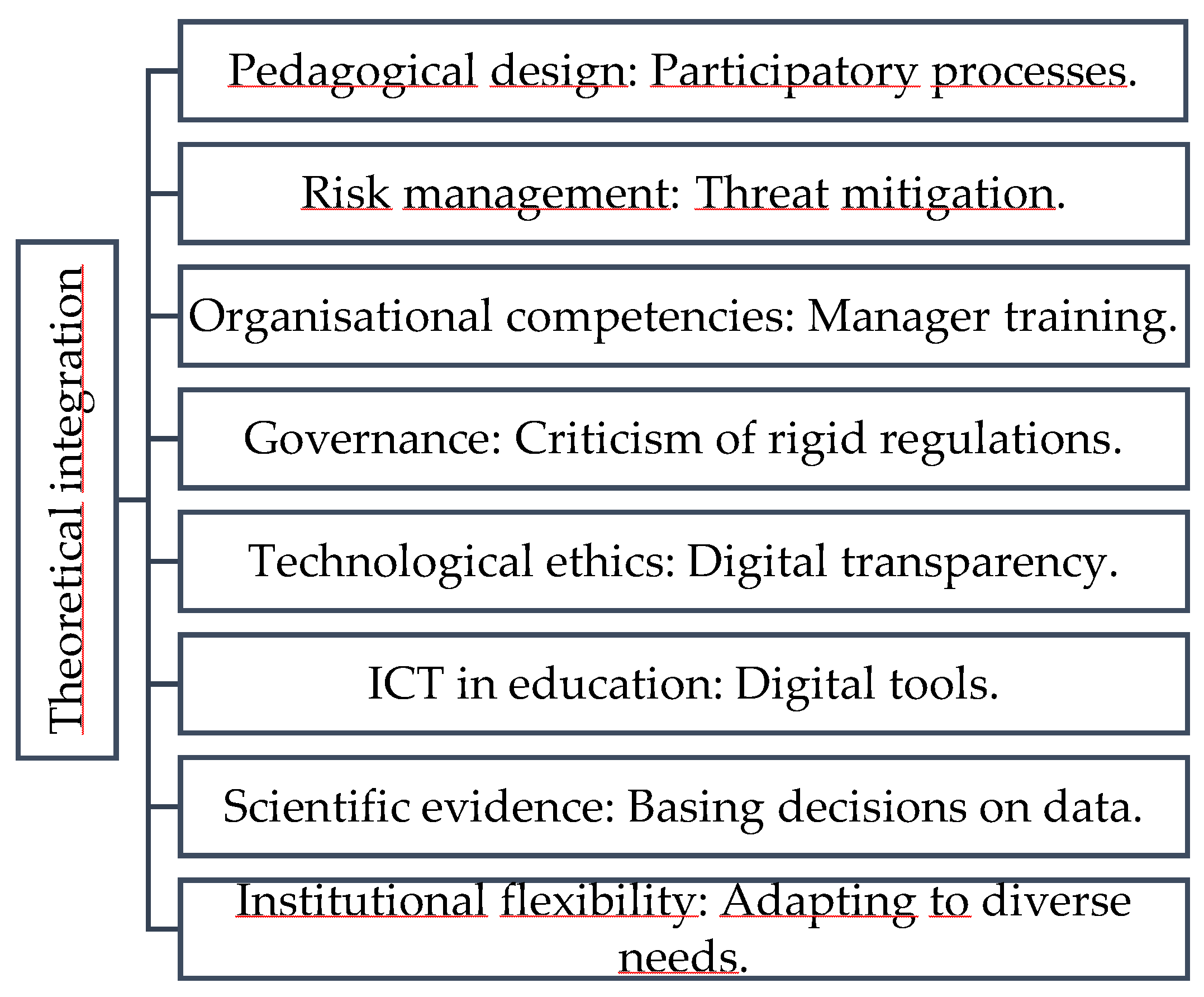

The theoretical integration in

Figure 1 provides a robust framework for analyzing university public procurement planning from multiple angles:

Identified gap: The combination of these approaches in the context of Peruvian universities, especially in regions with limited resources such as Huancavelica, has not yet been explored in depth.

1.2. Public Procurement Planning

Regarding the impact on institutional performance [

10], they showed that planning and staff competence improve organizational performance, especially in universities. They recommend adopting continuous training standards and predictive management tools. Likewise [

11], they demonstrated that planning mediates the relationship between staff capabilities and successful procurement. Their results emphasize that training in contract management is key to improving budget execution and reducing the risk of non-compliance.

Regarding public procurement planning and governance [

12], they identified that public procurement faces challenges such as confusing legislation, lack of planning, and lack of knowledge, proposing electronic systems and training as solutions. Their systematic review highlighted the need to improve public expenditure governance. Public procurement planning and corruption Control bodies, the OSCE, and citizens have identified that public entities face critical risks in procurement planning, including lack of competition and misuse of regulations, which can lead to acts of corruption [

13]. These findings highlight the need to strengthen transparency and oversight mechanisms in the early stages of the procurement process.

In citizen participation and sustainability [

14], they designed a participatory procurement model at a German university, involving students and suppliers in the creation of sustainable menus. This case demonstrated that the inclusion of local actors improves the social relevance of procurement. Furthermore, in public Works [

15], they analyzed the legal regime for local public works, concluding that citizen participation is only guaranteed when aligned with urban planning frameworks. Based on the OECD's strategic framework [

16], public procurement should include new collaboration schemes between government entities, suppliers, and social actors, promoting participatory governance models in all phases of the contract cycle. The synchronization of public and private interests in forward planning must be integrated into the national budgetary system, balancing public and private interests through models such as public-private partnerships (PPPs) [

17]. This is particularly relevant in infrastructure and long-term services.

In Integrated Procurement Efficiency [

18], they examined Law 14.133/2021 in Brazil, revealing that integrated procurement could reduce efficiency without rigorous planning. Their comparative analysis of international legislation emphasized the need to improve project selection requirements [

19] and highlighted the need for regulatory adaptation.

Risks in ICT contracts for smart cities [

20] proposed guidelines to mitigate risks in public ICT contracts, based on a systematic review. Their hypothetical-deductive approach revealed key vulnerabilities, such as information asymmetry between suppliers and administrations.

Fragmentation in social impact assessment [

21] interviewed Swedish transport planning experts, highlighting fragmentation in social impact assessment (SIA). The problems included public procurement, ambiguous roles, and a lack of methodological integration. Regulatory reforms for transparency [

22] emphasize that the modernization of procurement systems—such as the Organic Law in Ecuador—is essential to ensure efficiency and dynamism, provided that it is accompanied by training and continuous monitoring. and fiscal sustainability [

23] argue that planning should be extended to 5-10 year horizons, decoupling from annual budget cycles. This perspective facilitates the prioritization of strategic projects and avoids reactive spending, promoting fiscal responsibility.

On asset disposal and sustainability and solutions to effectiveness/efficiency challenges [

24] found that strategic planning is the dominant factor for successful public asset disposal linked to sustainable procurement.

Restrictive environmental criterio [

25] analyzed 756,482 procurement processes in Brazil, revealing that only 0.28% included environmental criteria. Their quantitative study criticized the legal limitations that hinder sustainability.

The adoption of e-procurement in South Africa [

26] identified six readiness factors (technological, financial, etc.) for the adoption of electronic procurement in South Africa. Their quantitative approach with Stata emphasized the need for evidence-based planning. And critical factors [

27] identified three satisfaction factors (support, intuitiveness, security) and two dissatisfaction factors in electronic procurement. Their quantitative study with PCA highlighted the role of intuitive design and technical support for successful adoption.

On the acquisition of unreliable materials in libraries [

28], they examined the complexity of evaluating non-fiction materials, highlighting the lack of standardized criteria. Their theoretical analysis proposed systematic methods to overcome gaps in public procurement. And on green procurement and profitability [

29], they evaluated the implementation of environmental criteria in Greece, highlighting that their successful adoption requires market research and inter-institutional coordination. Green procurement, although complex, can be profitable under clear regulatory frameworks.

On sustainable food planning [

30], they demonstrated that changes in public procurement (more vegetables, less meat) reduced emissions in Copenhagen nurseries. Their quantitative modeling validated the impact of sustainable food policies.

In governance in smart cities [

31], they studied the Amsterdam Smart City program, identifying four regulatory challenges: multi-stakeholder collaboration, network management, multi-level powers, and experimentation in public procurement.

In terms of tools for quarry planning [

32], they developed a Planning Support System (PSS) for quarries in Brescia (Italy), demonstrating its usefulness for public decisions based on geographic and environmental data. Regarding BIM technology in public procurement [

33], they suggested that the implementation of Building Information Modeling (BIM) requires standardized documents (EIR, BEP). Through expert interviews and comparative analysis, they highlighted the urgency of national guidelines to adapt ISO standards.

In sustainability in electro-electronic purchases [

34], they evaluated federal institutes in northern Brazil, finding low adoption of sustainable criteria in electro-electronic purchases. Their documentary analysis urged improvement in procurement plans.

1.3. Efficiency and Transparency

The study is based on theories related to public management, governance, and resource administration, with an emphasis on how strategic procurement planning influences efficiency (resource optimization) and transparency (access to information and accountability). The key theories identified in the literature review are discussed below.

New Public Management (NPM) Theory

Social Representations Theory

Public Value Theory

Agency Theory

Theoretical Gap and Originality

The NPM paradigm proposes the incorporation of private sector management approaches into public institutions with the aim of increasing efficiency, transparency, and the quality of services offered [

35].

One of the main lines of action of New Public Management is the adoption of international standards, such as International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS) and Monitoring and Assessment of Procurement Systems (MAPS), which seek to standardize financial reporting, facilitate comparability between institutions, and strengthen accounting transparency [

36,

37]. Similarly, [

38] argues that NPM is not a unified concept, but rather a set of heterogeneous ideas and practices with elements such as organizational structure, control, motivation, and citizen relations. Meanwhile, [

39] argues that, far from being a universal solution, NPM has had structurally negative effects on public organizations, affecting institutional cohesion and compromising essential democratic values. Consequently, it is essential to critically evaluate its applicability and legitimacy, especially in highly sensitive educational and administrative contexts such as universities.

Social representation theory relates to ideas about “efficiency” and “transparency” that are not only defined technically (by standards, indicators, or platforms) but also become social constructs shared among officials, citizens, the media, and auditors. These representations can be hegemonic (e.g., the ideal of merit-based and competitive hiring), emancipated (local or institutional perceptions that reconfigure standards), or controversial (controversies over cases of corruption or arbitrariness) [

40]. The adaptation of the arithmetic mean model proposed by Carl Friedrich Gauss as a tool for measuring transparency in the institutional sphere and revised by [

41]. We have:

n: number of transparency items,

Ei: score on item

i,

α: Weight of regulatory compliance (Law 32069),

Cp: Contracts published in advance,

Ct: Total planned contracts (PAC),

β Weight of reduction in incidents,

Dp: Processes without incidents (D+N+C+R),

Da: Total number of processes awarded,

γ: Weight of citizen participation,

Pi: Participatory mechanisms implemented,

Pt: Mechanisms required by OECD standards,

δ: Weight of digital platform use,

Pladicop%: % of information published on Pladicop.

In contexts such as Peru, marked by inequalities between locations and limited citizen oversight, the collaborative approach to transparency proposed by Moore 1995 and taken up by [

41] offers a strategic way to reduce the risks of patronage, transform platforms such as Pladicop into interactive spaces beyond mere dissemination, and strengthen institutional legitimacy by generating trust and active participation of the university community in the management of public resources.

In this sense, for a decision unit j, technical efficiency is calculated using the model of Charnes, Cooper, and Rhodes, 1978, taken up again by [

42].

Efficiency j: institutional efficiency, (u1, u2, u3, v1, v2, v3) are the weights, Services j: quality of services delivered by area, Satisfaction j: citizen satisfaction index regarding the service (surveys or complaints), Compliance j: degree of regulatory compliance (audits, sanctions, compliance reports), Budget j: economic resources allocated to the area and/or unit, Staff j: number of employees, Time j: duration of processes (time to award contracts)

It is interpreted as follows:

If efficiency j = 1, the unit and/or area is efficient compared to others

If efficiency j < 1, there is room for improvement in the services provided.

The need for control mechanisms, such as internal audits and efficiency between different units, to reduce the risk of management deviations gestión [

43], the application of legal sanctions for non-compliance with current regulations, as established by the Peruvian State Procurement Law.

Most studies analyze “NPM” in European or corporate contexts [

44,

45]. This article provides empirical evidence from Peruvian universities in Huancavelica, integrating factors such as: Technological barriers [

46] in regions with limited infrastructure. Transparency: Access to information and accountability (Public Value + Governance) according to [

47]. Governance: Multi-stakeholder approach (State, university, society) for legitimate decisions [

48]. Cultural factors in university management, which can be better understood with the following theories:

Triple Helix Theory

Theory of Planned Behavior

Theory of Cultural Friction

Labor Demand and Resource Model

Neural Network Theory Applied to Cultural Sustainability

From the perspective of the Triple Helix Theory, in the context of public universities, digital technologies applied to public procurement not only improve administrative efficiency but also reinforce institutional legitimacy by facilitating transparency and traceability. This model recognizes that interactions between universities, government, and industry are not unidirectional but dynamic and co-evolutionary. In decentralized contexts such as Peru, the strategic use of electronic platforms highlights the coordinating role of the state, the innovative capacity of the academic sector, and the technological offerings of the productive sector, generating a collaborative environment oriented toward public value [

49].

On an empirical level, the study [

50] highlights how Spanish universities strengthen their alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through active partnerships with external agents. Likewise, [

51] demonstrates that cooperation between universities and public entities contributes to improving sustainability in the field of cultural heritage.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) has proven effective in explaining students' entrepreneurial intentions in the university setting, especially when analyzing the impact of institutional support on the formation of such intentions, such as attitude, subjective norms, and perceived control over access to resources and practical experience. The study [

52] confirms that these three factors significantly mediate the relationship between university educational support and entrepreneurial intention, suggesting that universities can influence the future behavior of their students through training strategies aligned with the principles of TPB.

The study [

53] applies this theory to predict continuity in the use of sustainable educational technologies. Complementarily, [

54] shows how personal attitudes and normative pressure affect youth leadership oriented toward sustainability.

The Theory of Cultural Friction examines the conflicts that arise in intercultural contexts due to differences in values, beliefs, and practices. This perspective is useful for understanding the challenges of interaction between cultures in educational and tourist environments, especially in universities with a strong international presence. [

55] analyzes cultural clashes in the provision of hotel services, whose implications can be extrapolated to the academic sphere. In turn, [

56] reveals how student mobility generates valuable lessons about cultural sustainability through intercultural contact.

The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model, in the university context, is particularly useful for evaluating the institutional factors that affect the ability of faculty to contribute to the achievement of the SDGs. According to [

57], administrative overload, pressure for academic productivity, and regulatory ambiguity can lead to health deterioration. The flexibility of the model allows its categories to be adapted to decentralized university environments, recognizing that the balance between demands and resources is key to effective and sustainable governance in higher education.

Artificial neural networks represent a computational approach that allows complex behavior patterns to be predicted through machine learning. For example, the study [

58], which uses neural networks to predict student attendance at cultural events, demonstrates the potential of artificial intelligence to promote sustainable practices in educational and artistic contexts.

In Peru, the “PAC” can be modified in response to changes in budget allocation or the rescheduling of institutional goals, as is the case at the “UNH.”

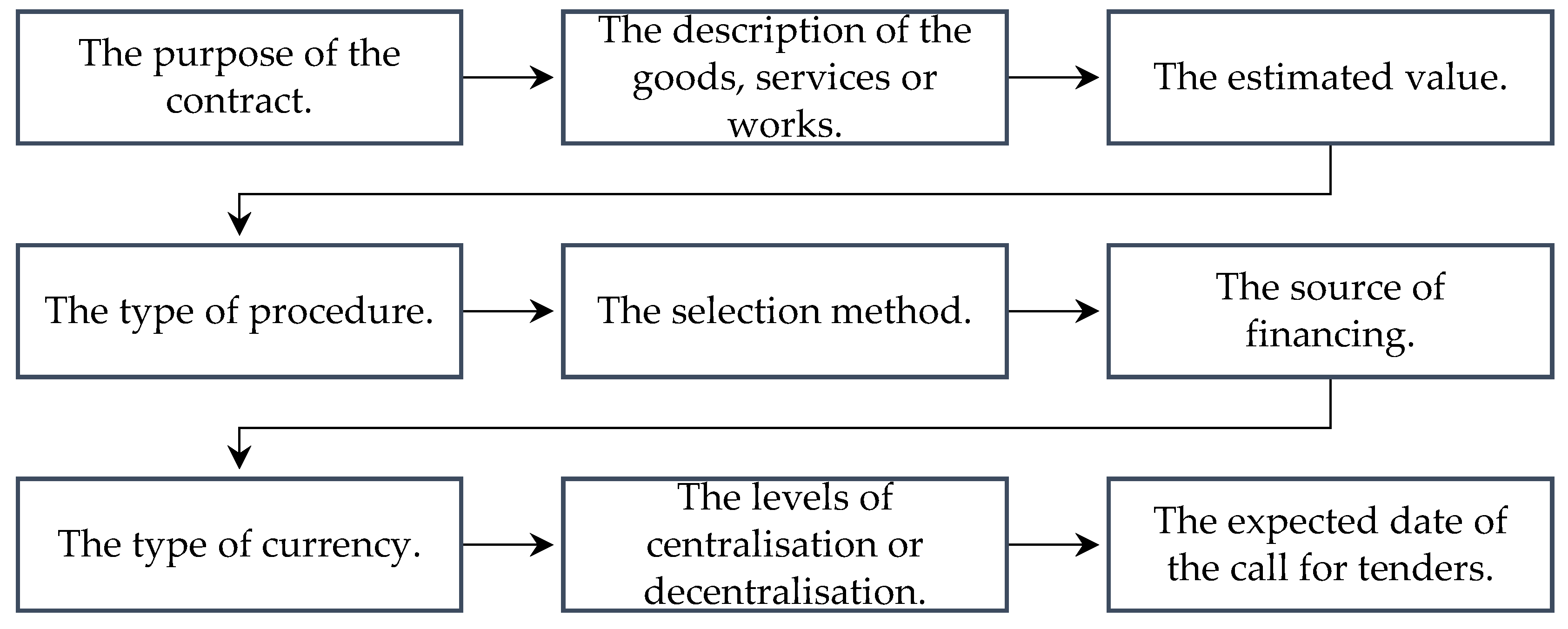

Figure 2 shows the main elements of this process. For this reason, current regulations require the head of the entity to evaluate its implementation every six months and, if necessary, adopt corrective measures to ensure compliance with institutional objectives.

In the area of decentralized university management, the preparatory phase of public procurement has regulatory gaps, as there are no mandatory minimum deadlines for the preliminary actions that entities must take. However, with the aim of improving operational efficiency and ensuring institutional transparency, the “OSCE” has implemented monitoring mechanisms that allow the time elapsed from the receipt of the request by the Contracting Authority (OEC) to the formalization of the procedure on the Pladicop electronic platform to be calculated. This practice helps to identify administrative bottlenecks, strengthen the traceability of processes, and guide planning toward the generation of public value, which is particularly relevant in regional universities where resources and citizen oversight are often limited.

Selection procedure: A standardized process (tenders, competitions) based on technical and multi-metric criteria, which seeks to ensure impartial selection and “best value,” transcending the logic of the lowest Price [

59].

Regulations and rules: Set of laws, regulations, and procurement systems that make up the regulatory framework; recent studies highlight how these regulations increase institutional transparency and reduce the risk of corruption [

60].

Structural design: Operational organization of purchasing processes and their institutional alignment. Systemic reviews highlight that coordinated structures (frequent units, integration of e-GP, clear roles) facilitate efficient management [

61].

2. Materials and Methods

This research was classified as applied, as it aims to solve a specific problem in the field of university management: poor planning of public procurement and its impact on institutional efficiency and transparency. Although it is based on conceptual and regulatory frameworks, its purpose is to generate empirical evidence and propose practical recommendations that can be implemented in decision-making and the improvement of administrative processes in similar contexts. The level is descriptive-correlational because it characterizes the perceptions and practices of public servants in relation to the regulations issued by Peruvian and international bodies. In the correlational dimension, the relationship between variables such as knowledge about the SDGs and the OECD, attitudes toward sustainability, and actions implemented at the institutional level is analyzed using a qualitative approach because the aim is to interpret the meanings, motivations, and subjective perceptions of the actors involved in public procurement processes. The methodological design was non-experimental and cross-sectional, given that data collection was carried out at a single point in time, without manipulation of variables, because it allows for the description of the phenomenon under study and the exploration of associations between variables of interest.

The study population consisted of 250 public servants belonging to different academic, technical, and administrative units of a public university, calculated using the formula for finite populations, considering a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%.

Based on this, a sample of 152 participants was determined, selected through non-probabilistic convenience sampling, ensuring minimum criteria of representativeness and functional diversity, including administrative, academic, and management personnel.

Distribution of the sample according to functional units

• Operational Administrative Units:

These units are responsible for issuing requirements and preparing and approving documents related to contracting processes. The following areas participated: Human Resources (n = 11), Planning and Budgeting (n = 10), Accounting (n = 6), Procurement (n = 12), Investment Execution (n = 10), and the Formulation Unit (n = 9).

• Technical Management Units:

These units act as end users or evaluators of the goods and services contracted. The areas of Quality Management (n = 9), University Welfare Directorate (n = 9), Information Technology Services (n = 12), General Services and Maintenance (n = 13), Central Laboratory (n = 6), and Central Library (n = 12).

• Academic Units:

They participate as expenditure supervisors and strategic users. The following were considered: Faculty deans (n = 9), FOCAM Project teachers (n = 18), and other bodies such as the Academic Vice-Rector's Office and the Graduate School, with no specific sample in this case.

• Other Units:

The Academic Vice-Rector's Office (n = 3) and the Graduate School (n = 3) were included, which perform institutional impact and transparency assessment functions within the framework of the study.

Data collection instrument.

A structured questionnaire was designed, consisting of items with a five-level Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly agree), aimed at capturing both perceptions and levels of knowledge, formulated on the basis of the guidelines of Law No. 30225, Law No. 32069, and international frameworks such as (OECD, UNCITRAL).

Content validity was determined through the expert judgment of three specialists in sustainability and university management, who evaluated the relevance, clarity, and consistency of the items with respect to the theoretical constructs. The reliability of the instrument was verified using Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α), which was greater than 0.71, indicating adequate internal consistency for basic social research purposes.

The instrument was applied to 152 selected samples with the aim of evaluating five dimensions related to the independent variable (level of planning in public procurement): procurement file, selection procedure, rules and regulations, supplier evaluation, and control and supervision; as well as to measure the dependent variable, corresponding to the institutional perception of efficiency and transparency.

Data collection was carried out using a face-to-face survey. Item coding was categorized by variable dimension. Processing was carried out using SPSS_31 statistical software and Excel for descriptive and correlational analysis.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the level of planning, calculating measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (standard deviation).

The results were interpreted by dimension, contrasting them with current regulatory frameworks and international standards for public procurement planning, and correlating the variables based on the objectives.

As a methodological background [

62], they developed a study with three objectives: (a) to deepen the multidimensional nature of the construct, (b) to validate the questionnaire to assess student perceptions of learning methodologies, and (c) to analyze the feasibility of nominal groups as a qualitative technique. The results demonstrated the statistical validity of the instrument and the effectiveness of nominal groups as a participatory and motivational technique.

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of the Level of Planning and Its Institutional Perception

The following sections present the findings of the study structured according to the specific objectives. They include empirical analysis, documentary review, and normative comparison, as well as correlations between the key variables of the model: planning, efficiency, and transparency.

Table 1 shows the perception of civil servants.

The results indicate that the level of planning in public procurement processes at the public university of Huancavelica is perceived as average or moderate, with a slight tendency toward neutrality. The internal consistency of the instrument was acceptable (α = 0.784), and most items showed responses centered around the value 3 (neither agree nor disagree), suggesting the need to reinforce the clarity, monitoring, or visibility of institutional planning practices.

3.2. Documentary Analysis of Procedures and Efficiency in University Management (2019–2024)

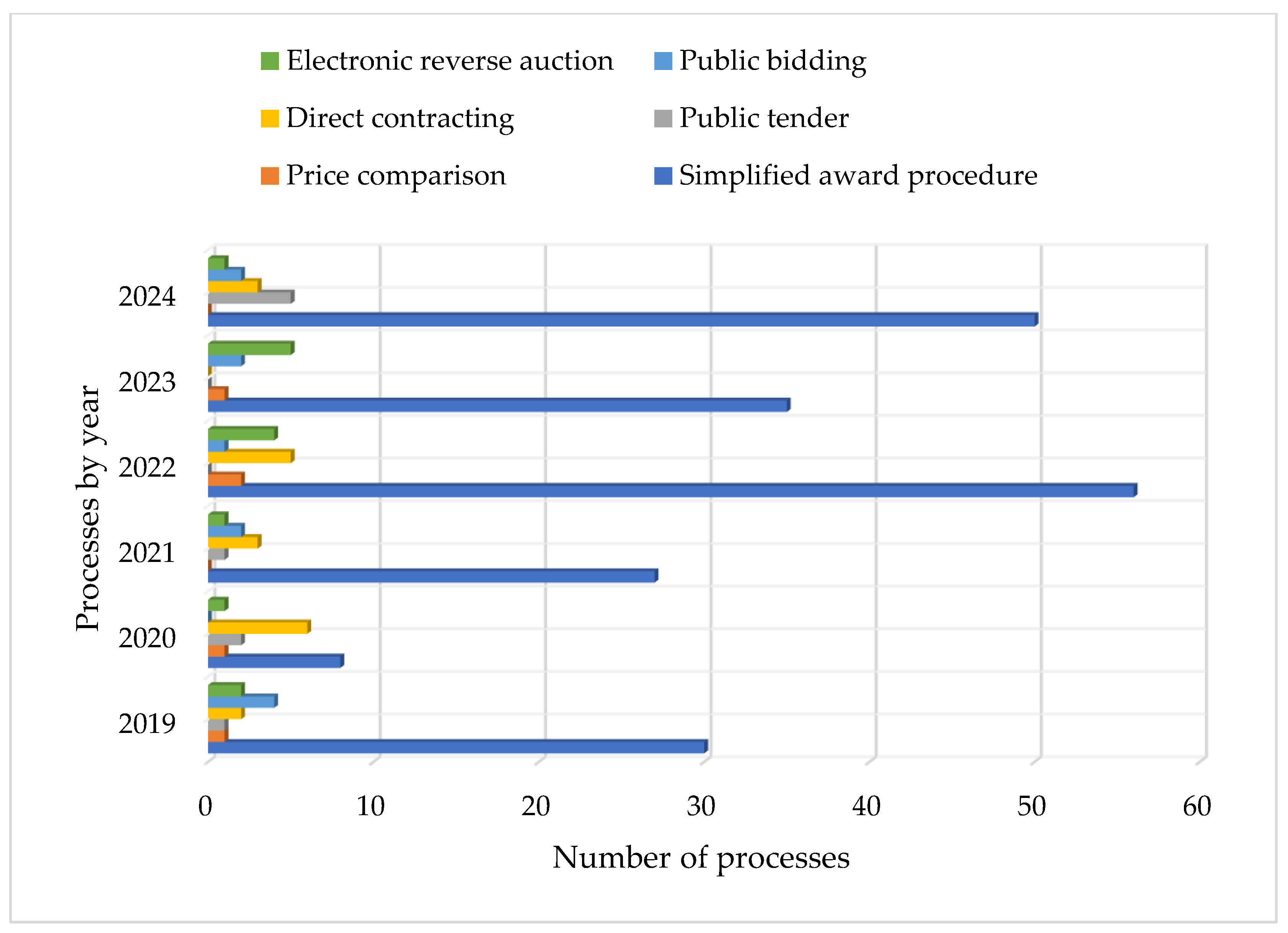

Figure 3 shows a horizontal annual comparison of the types of contracting procedures used at the public university of Huancavelica between 2019 and 2024. Simplified awarding clearly stands out as the most widely used mechanism throughout the period, with peak values in 2022 (56 processes) and 2024 (50 processes). This suggests an established institutional trend toward rapid execution procedures, commonly applicable to lower-value goods and services.

Other procedures—such as tendering, competitive bidding, and electronic reverse auctions—show marginal and variable participation, with no sustained patterns. Direct contracting, although limited, experienced a slight upturn in 2020 and 2022, possibly associated with exceptional conditions or emergency situations. The price comparison procedure shows virtually no use in recent years, which could indicate an institutional preference for other forms of simplified selection.

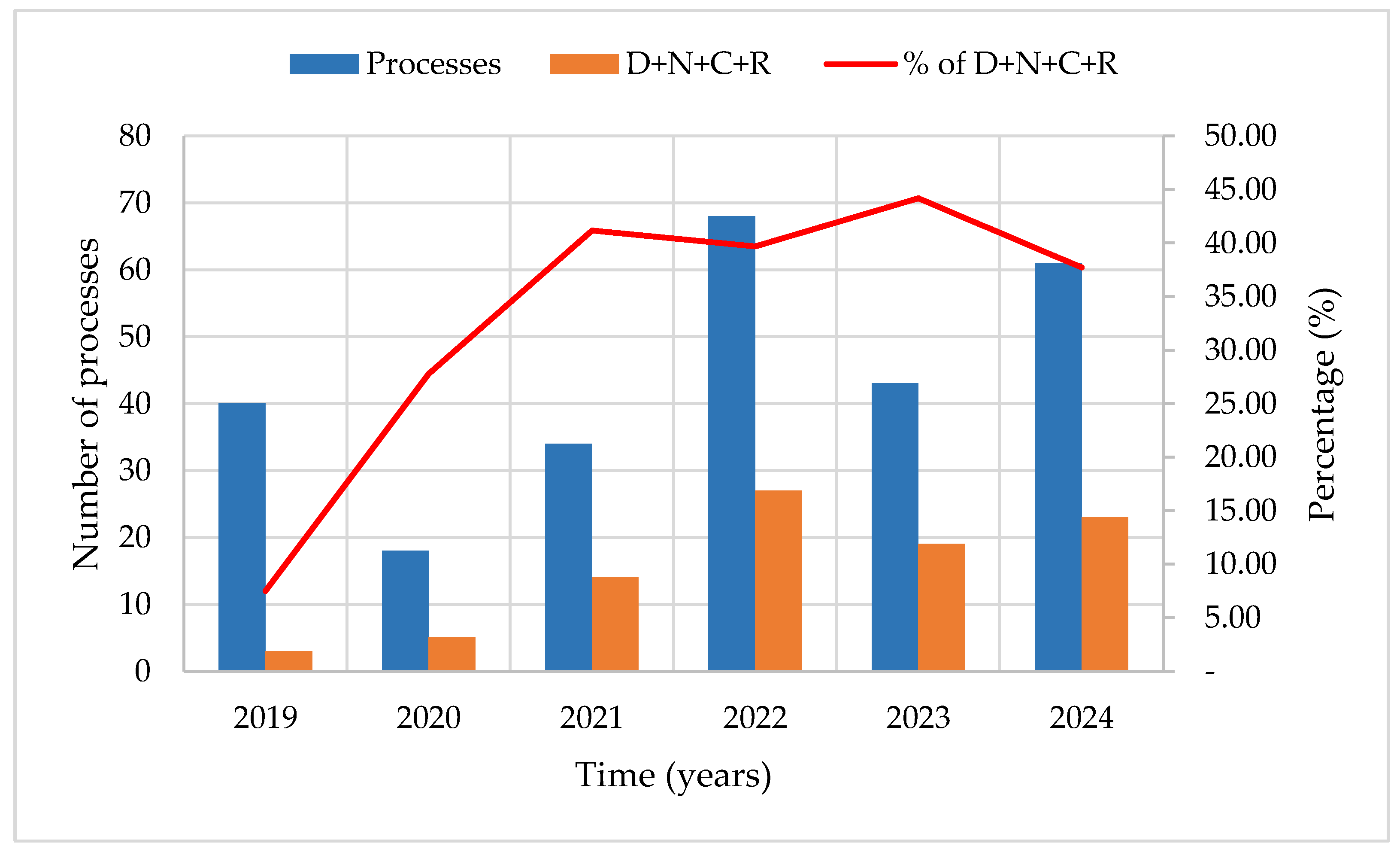

Figure 4 shows the annual evolution of the total number of public procurement processes executed and the number of processes with negative observations, expressed in columns D, N, C, and R, where (Deserted, Null, Cancelled, Rescheduled). The indicator % of D+N+C+R reflects the percentage of processes with problems or interruptions out of the annual total.

There has been an increase in observed processes (D+N+C+R): that is, the percentage of processes with incidents rose from 7.5% in 2019 to levels above 40% between 2021 and 2023, representing a notable deterioration in the efficiency of the contracting system. In 2023, the highest peak was reached with 44.19% of processes with problems, despite not being the year with the highest total number of processes.

Efficiency in decline: Although the number of processes in 2022 and 2024 was high (68 and 61 respectively), there were also worrying percentages of processes with problems (almost 40% in both cases), suggesting a structural weakness in the planning and execution of procurement.

2020–2021 period: Despite the low number of processes in 2020 (18), 27.78% presented observations, possibly affected by exceptional conditions such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, the percentage shot up to 41.18%, initiating a sustained trend of inefficiency.

Likewise, the analysis of efficiency in university management revealed structural weaknesses, mainly associated with the preparatory stage of public procurement procedures.

Table 2 shows the information extracted from the specific control reports carried out by the Comptroller General of the Republic and from technical studies by the OSCE, which allows for the identification of recurring causes of inefficiency, both operational and regulatory.

Both reports agree that the identified failures originated in the preparatory acts, confirming that this critical stage presents institutional bottlenecks with a direct impact on the overall efficiency of the procurement system. The units involved—both administrative, operational, technical, and academic—showed weaknesses in the formulation, review, and validation of files, requiring corrective intervention from the planning stage.

Previous findings by the OSCE determined that the Market Feasibility Study (EPOM) accounts for up to 50% of the total time spent on preparatory activities, making it the most critical phase due to the difficulty in identifying suitable suppliers. In addition, a subsequent technical study by the OSCE indicated that the average duration of preparatory actions is 71.6 calendar days, which is higher than that recorded in local governments (64.4 days), with a greater presence of extreme values in university entities and those within the FONAFE sphere, such as the intervened university.

3.3. Regulatory Consistency: Comparative Analysis Between National Laws and International Standards

By analyzing the relationship between Peruvian laws in force as of 2025 and a set of relevant international laws, standards, and frameworks in the area of public procurement. The purpose is to identify the levels of convergence and relationship between the national legal framework and international best practices that strengthen efficiency, transparency, citizen participation, and the quality of public spending.

Table 3 shows the content analysis and common approach between Law No. 30225 and Law No. 32069 in the preparatory stages of public procurement.

Law No. 32069 greatly expands the preparatory phase, highlighting new principles such as value for money, interaction with the market, and the mandatory use of digital platforms such as Pladicop. It incorporates collaborative methodologies, promotes advance transparency, and establishes guidelines for segmentation, technical approval, and market research. While Law No. 30225 structured the preparatory actions in five articles, the new law develops them in depth with 14 articles, providing a more robust operational framework.

This regulatory analysis is presented as a basis for comparing empirical findings with the current global regulatory framework.

Table 4 presents the main subtopics regulated by Law No. 32069 and the current international frameworks, indicating the degree of regulatory relationship:

In more specialized areas—such as supplier evaluation, excellence in contract execution, and citizen participation—the correspondence is only partial, suggesting opportunities for improvement. These gaps are related to emerging practices such as sustainable procurement, project management, and active social control, which have not yet been fully institutionalized in the Peruvian framework.

3.4. Evaluation of Efficiency and Transparency in Contracting Methods

Table 5 presents the descriptive results for the dependent variable, which consists of items that evaluate institutional efficiency and transparency in government contracting methods.

The results reveal that public servants' perception of institutional efficiency and transparency in public procurement is at a medium level, with no evidence of marked approval or rejection. The reliability of the scale was satisfactory (α = 0.776), which guarantees the soundness of the interpretations. The variability in some items suggests areas with divided opinions, which deserve further analysis (e.g., monitoring of results, access to information, governance, society, etc.).

3.5. Relationship Between Planning and Institutional Efficiency/Transparency

Table 6 shows the results of the correlation analysis between the total planning variable and the total efficiency/transparency variable, using Spearman's coefficient to establish the strength and direction of the relationship.

A positive and statistically significant correlation was observed between public procurement planning and the perception of institutional efficiency and transparency (ρ = 0.566; p < 0.01). This finding suggests that higher levels of planning are consistently associated with higher levels of operational efficiency and institutional transparency mechanisms at the university analyzed.

3.6. Proposed Recommendations for Optimizing Public Procurement Planning

Based on the empirical, documentary, and regulatory findings of this study, the following strategic recommendations are formulated to improve public procurement planning at the Public University of Huancavelica, with a direct impact on operational efficiency and institutional transparency:

1. Institutionalize the semi-annual evaluation of the “PAC”

Strengthen the application of Article 8 of Law No. 30225 by implementing semi-annual reviews of the PAC by senior management, with corrective reports on unexecuted processes, rescheduled processes, and compliance with related goals.

2. Strengthen the preparatory stage through unified technical protocols

Develop operational guidelines for the formulation, validation, and review of technical files prior to contracting, ensuring technical, regulatory, and budgetary consistency from the beginning of the process. Include checklists and standardized formats based on Law No. 32069 and its 14 expanded articles on planning.

3. Reduce the levels of processes with observations (D+N+C+R) through preventive control.

Establish an internal alert system to detect recurring patterns of canceled, void, or deserted processes. This includes prior verification of the technical file, market research, and proper definition of the object of the contract.

4. Strengthen the ongoing training of the responsible units

Implement periodic technical training programs in public procurement, aimed at those responsible for logistics, formulation, requirements, and evaluation, with an emphasis on current regulations, OECD best practices, and institutional sustainability criteria.

5. Integrate digital tools for traceability and active transparency

Promote the mandatory use of platforms such as Pladicop, ensuring the advance publication of requirements, procurement schedules, and selection criteria, with feedback mechanisms from suppliers and the public.

6. Promote inter-area and interdisciplinary coordination mechanisms

Foster participatory planning spaces between technical, academic, and administrative units to build realistic procurement plans aligned with institutional and budgetary objectives.

7. Adapt the institutional model to the “value for money” approach

Apply criteria of efficiency, quality, and results in the evaluation of suppliers, considering performance indicators and the life cycle of the contracted good or service, in accordance with international standards (OECD, MAPS, ISO 20400).

3.7. Contributions

This study reveals for the first time the specific mechanisms through which public procurement planning (PAC) transforms governance in peripheral public universities.

Table 7 summarizes the most relevant contributions of the study.

4. Discussion

4.1. Assessment of the Level of Planning and Its Institutional Perception

The results show average levels in public procurement planning, with an overall average of around 3 points on the Likert scale. This finding suggests a moderate perception among public servants regarding compliance with the preparatory phases, in line with studies such as[

10,

12], which point out that poor planning compromises operational efficiency. The validity of the instrument and the adequate Cronbach's alpha (0.784) reinforce the consistency of the perceptual analysis. This diagnosis is consistent with Social Representation Theory [

40], which allows us to interpret how planning is internalized as a bureaucratic process rather than a strategic tool.

4.2. Documentary Analysis of Procedures and Efficiency in University Management (2019–2024)

The documentary review of processes executed and audits between 2019 and 2024 revealed deficiencies in the execution of the “PAC,” as well as a high incidence of recurring observations in the audit reports. This empirical evidence confirms the findings of [

18], regarding the negative impact of weak planning on contractual efficiency. From Hood's “NPM” perspective, these results reinforce the need to establish objective performance metrics and corrective control, something also provided for in the IPSAS Standards and Law 30225.

4.3. Regulatory Consistency: Comparative Analysis Between National Laws and International Standards

The analysis of consistency between Peruvian regulations and international standards (OECD, UNCITRAL, IPSAS) shows progress in the formalization of procedures, but there are still gaps in the adoption of performance evaluation mechanisms, active transparency, and forward planning [

23]. These regulatory gaps replicate what was noted by [

20], regarding the need to adapt legal frameworks to institutional realities. This regulatory tension can also be analyzed from the Agency Theory perspective, as it highlights a gap between the expectations of the State (principal) and the technical capacity of the university manager (agent).

4.4. Evaluation of Efficiency and Transparency in Contracting Methods

The 13 items that measured efficiency and transparency yielded average perception values (Cronbach's alpha = 0.776), indicating that, although certain formal aspects are met, doubts remain about the quality of spending, accountability, and the traceability of processes. This interpretation is in line with Moore's Public Value Theory, as it shows that transparency is not only a normative principle but also a condition of legitimacy. It also confirms the postulate of [

39] on the negative effects of implementing NPM without solid structural support.

4.5. Relationship Between Planning and Institutional Efficiency/Transparency

Spearman's correlation (.566, p < 0.01) confirms a moderate and significant association between planning and efficiency/transparency. This confirms the findings of [

11], who demonstrate that planning acts as a mediating variable between organizational competence and institutional outcomes. This association is consistent with the Theory of Planned Behavior [

52], as favorable attitudes and perceptions toward planning predict behaviors oriented toward efficiency and transparency. Furthermore, it validates the methodological integration of the study (applied, correlational, and non-experimental), whose instruments were consistent and reliable.

4.6. Proposed Recommendations to Optimize Public Procurement Planning

The proposed recommendations are based on the gaps detected in the planning and execution of processes. These include the implementation of continuous training plans, the incorporation of technology (e-procurement), regulatory alignment with international standards, and the strengthening of citizen control. The recommendations are aligned with the proposals ine [

14], as well as with the participatory governance suggested by the Triple Helix Theory. In addition, they address the structural factors identified by the JD-R Model, related to work overload, lack of tools, and limited institutional motivation.

5. Conclusión

Planning in public procurement at the university is perceived as moderately adequate, with average scores close to the neutral value (3) on the Likert scale. This trend reflects an ambiguous institutional assessment of the effectiveness of planning practices. The reliability of the instrument was acceptable (α = 0.784), supporting the validity of the diagnosis.

The analysis of the processes carried out between 2019 and 2024 showed a high frequency of incidents, with up to 44% in certain periods. These findings suggest declining operational efficiency, mainly due to deficiencies in preparatory actions. Audit reports and OSCE studies corroborate the existence of structural bottlenecks that affect execution and contract compliance.

In terms of the legal framework, a high degree of formal correspondence was identified between Law No. 30225, Law No. 32069, and international frameworks such as those of the OECD, UNCITRAL, ISO 20400, and INTOSAI, especially in terms of principles of transparency, control, and planning. However, gaps persist in practical implementation, especially in areas such as sustainable supplier assessment, citizen participation, and results-based management, which limits alignment with international standards of excellence.

The institutional perception of efficiency and transparency is at an intermediate level, with no predominance of positive or negative judgments. The internal consistency of the instrument was adequate (α = 0.776), although levels of dispersion were observed in some items, indicating differences in the experiences and criteria of university actors and an uneven application of the principles of control and accountability.

The correlational analysis showed a positive and significant relationship (ρ = 0.566; p < 0.01) between planning and the perception of efficiency/transparency, highlighting its strategic role in university governance. It is recommended to institutionalize the PAC evaluation, strengthen preparatory actions, train staff, digitize procedures, and apply a value-for-money approach to improve efficiency and transparency.

Author Contributions

Teófila Chanca Mucha: research and methodology. Esteban Eustaquio Flores-Apaza: supervisor, validation. Rolando Ore-Flores: Project management. Jonathan Elmer Cahuana Pari: Data curation. Rúsbel Freddy Ramos Serrano: Formal analysis and visualization. Karen Alcos-Flores: Fundraising and resource acquisition. Erik Mulato-Ccoyllar: Conceptualization and software. Papa Pio Ascona García: Writing (proofreading and editing), writing (original draft).

Funding

This research did not receive external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was conducted in strict accordance with established ethical principles for studies. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the research institute, focusing solely on the main campus of the aforementioned university.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects who participated in the study, only in responding to the questions in the data collection instrument (survey). Due to this REASON Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this study are archived in the personal database of the first author as part of the desk work related to his doctoral research. These data may be requested from the corresponding author upon academic justification.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the National University of Huancavelica for facilitating the development of the study, as well as to the staff of its various units for their participation in the surveys. We also acknowledge the valuable contributions of external collaborators and researchers, whose observations and suggestions were essential for the development and consolidation of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest, whether financial, personal, or institutional, that has influenced the development, analysis, or presentation of the contents of this article. Body

References

- S. Kauppi, H. Muukkonen, T. Suorsa, and M. Takala, “I still miss human contact, but this is more flexible—Paradoxes in virtual learning interaction and multidisciplinary collaboration,” British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 1101–1116, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Abgadzhava, A. V. Aleinikov, and A. G. Pinkevich, “Risk-reflexive determinants of adaptation under threats: An empirical study*,” RUDN Journal of Sociology, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 787–799, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. V. Solovova and N. V. Sukhankina, “Comparative and correlation analysis of experimental work for developing organisational and managerial competences in university teachers,” Education and Self Development, vol. 15, no. 3, 2020. [CrossRef]

- I. Feller, “Neoliberalism, Performance Measurement, and the Governance of American Academic Science,” Norteamerica, 2008. [Online]. Available: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8hp0p7vd.

- B. Israel, “Digitalisation opportunities as drivers of confidentiality rules in public procurement: Organisational information culture as a moderator,” Journal of Process Management and New Technologies, vol. 13, no. 1–2, pp. 38–55, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Soylu et al., “Data Quality Barriers for Transparency in Public Procurement,” Information (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 2, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Shumeiko and A. Nypadymka, “Ict-supported students independent work in the esp context: the new reality in tertiary education,” Advanced Education, vol. 8, no. 18, pp. 79–91, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Bozkurt et al., “The Manifesto for Teaching and Learning in a Time of Generative AI: A Critical Collective Stance to Better Navigate the Future,” Open Praxis, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 487–513, 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Condello, L. Capranica, M. Doupona, K. Varga, and V. Burk, “Dual-career through the elite university student-athletes’ lenses: The international FISU-EAS survey,” 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mebrate and K. Shumet, “Assessing the impact of procurement practice on organizational performance,” Cogent Business and Management, vol. 11, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- I. A. Changalima and A. E. Mdee, “Procurement skills and procurement performance in public organizations: The mediating role of procurement planning,” Cogent Business and Management, vol. 10, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Sturmer, E. Garcia, E. N. Pereira, and F. F. F. Peres, “Public purchases: a systematic review of challenges and opportunities,” AtoZ, vol. 11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Castro Fuentes, “Un breve diagnóstico sobre la actividad de supervisión del OSCE en las compras públicas,” Ius et Praxis, no. 054, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Kretschmer and S. Dehm, “Sustainability transitions in university food service—A living lab approach of locavore meal planning and procurement,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 13, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. B. Entrena Ruiz, “Derecho a la ciudad, obras públicas locales y participación ciudadana,” Revista de Estudios de la Administración Local y Autonómica, 2022. [CrossRef]

- OECD, Public Procurement for Innovation. in OECD Public Governance Reviews. OECD, 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Obicci, G. Mugurusi, and P. O. Nagitta, “Establishing the connection between successful disposal of public assets and sustainable public procurement practice,” Sustainable Futures, vol. 3, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. A. C. Carmona, B. R. Marques, and O. Cavallari, “Integrated contract in Law 14.133/2021: new law, same problems? a study of comparative law,” Revista Brasileira de Politicas Publicas, vol. 11, no. 3, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. A. C. Carmona and M. A. Alamy, “Planning in the new bidding law and the applicability of its instruments in small municipalities,” Revista Brasileira de Politicas Publicas, vol. 13, no. 2, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Ortega Saurith and C. A. Correa Martínez, “Riesgos en el uso del fondo de contingencia ante urgencia manifiesta en la contratación pública en Colombia,” Novum Jus, vol. 16, no. 3, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Stjernborg, “Social impact assessments (SIA) in larger infrastructure investments in Sweden; the view of experts and practitioners,” Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, vol. 41, no. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. E. Faz Cevallos, L. E. Fuentes Gavilanez, M. Hidalgo Mayorga, and K. G. Guerrero Arrieta, “Government procurement in Ecuador: analysis and perspective,” Universidad Ciencia y Tecnología, vol. 27, no. 119, 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. V. Kikavets and Y. K. Tsaregradskaya, “Public procurement planning as a factor of socioeconomic development of the state,” Advances in Research on Russian Business and Management, vol. 2023, 2023.

- A. Tartaglia, G. Castaldo, and A. F. L. Baratta, “The role of Architectural Technology for the ecological transition envisaged by the PNRR,” TECHNE, vol. 23, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Bernardi, P. de T. De Lara Pires, and E. L. Peters, “Analysis of the environmental criteria in public procurements,” Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente, vol. 58, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. N. Maepa, M. F. Mpwanya, and T. B. Phume, “Readiness factors affecting e-procurement in South African government departments,” Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, vol. 17, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Ragin-Skorecka and Ł. Hadaś, “Sustainable E-Procurement: Key Factors Influencing User Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction,” Sustainability (Switzerland) , vol. 16, no. 13, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Dragaš, S. Ercegovac, and M. T. Kordić, “In the rift between criteria: procurement of unreliable nonfiction materials in public libraries.,” Vjesnik Bibliotekara Hrvatske, vol. 65, no. 3, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. S. Orfanidou, N. P. Rachaniotis, G. T. Tsoulfas, and G. P. Chondrokoukis, “Life Cycle Costing Implementation in Green Public Procurement: A Case Study from the Greek Public Sector,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Lassen, M. Nordman, L. M. Christensen, and E. Trolle, “Scenario analysis of a municipality’s food purchase to simultaneously improve nutritional quality and lower carbon emission for child-care centers,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 10, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Voorwinden, “Regulating the Smart City in European Municipalities: A Case Study of Amsterdam,” European Public Law, vol. 28, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. C. Pavesi, A. Richiedei, and M. Pezzagno, “Advanced modelling tools to support planning for sand/gravel quarries,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Popov, M. Medineckienė, T. Grigorjeva, and A. R. Zabulėnas, “Building information modelling: Procurement procedure,” Business, Management and Economics Engineering, vol. 19, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. P. da Silva and R. D. P. da Conceição, “Sustainability criteria and practices in electro-electronic purchases by ifect in the northern brazil region,” Revista de Gestao Social e Ambiental, vol. 18, no. 2, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Hood, “The ‘new public management’ in the 1980s: Variations on a theme,” Accounting, Organizations and Society, vol. 20, no. 2–3, pp. 93–109, Feb. 1995. [CrossRef]

- J. Christiaens, B. Reyniers, and C. Rollé, “Impact of IPSAS on reforming governmental financial information systems: A comparative study,” International Review of Administrative Sciences, vol. 76, no. 3, 2010. [CrossRef]

- L. Mentini and A. Levatino, “A ‘three-legged model’: (De)constructing school autonomy, accountability, and innovation in the Italian National Evaluation System,” European Educational Research Journal, vol. 23, no. 3, 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Gruening, “Origin and theoretical basis of new public management,” International Public Management Journal, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–25, Mar. 2001. [CrossRef]

- T. Diefenbach, “New public management in public sector organizations: The dark sides of managerialistic ‘enlightenment,’” Public Adm, vol. 87, no. 4, pp. 892–909, Dec. 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. B. Nonato, J. R. Fontes-Filho, and F. P. de Michelotto, “Strategic planning: unraveling civil servants’ autonomy and motivation through social representations of organizational goals,” Revista de Administracao Publica, vol. 58, no. 6, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Douglas and A. Meijer, “Transparency and Public Value—Analyzing the Transparency Practices and Value Creation of Public Utilities,” International Journal of Public Administration, vol. 39, no. 12, pp. 940–951, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Zarrin and J. O. Brunner, “Analyzing the accuracy of variable returns to scale data envelopment analysis models,” Eur J Oper Res, vol. 308, no. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Alibekova, L. Sembiyeva, A. Petrov, and A. Nurumov, “Organisation problems and audit of the effectiveness of interbudgetary relations,” Public Policy Adm, vol. 20, no. 5, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Szewieczek, B. Dratwińska-Kania, and A. Ferens, “Business model disclosure in the reporting of public companies—an empirical study,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 18, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Gutiérrez-Ponce, J. Chamizo-González, and N. Arimany-Serrat, “Disclosure of Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance Information by Spanish Companies: A Compliance Analysis,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 6, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. M. V. Lozano and J. D. Bardales, “Impact of technological barriers on the efficiency and transparency of public management: A systematic review,” 2024, EnPress Publisher, LLC. [CrossRef]

- H. el Kezazy, Y. Hilmi, E. F. Ezzahra, and I. Z. H. Hocine, “Conceptual model of the role of territorial management controller and good governance,” Revista de Gestao Social e Ambiental, vol. 18, no. 7, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. E. L. Ammar, W. E. L. Hajj, and A. Mroueh, “DEMATEL analysis of corporate and public governance: identifying key factors for good governance,” Administratie si Management Public, vol. 41, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Amaral, Y. Cai, A. R. Perazzo, C. Rapetti, and J. M. Piqué, “The Legacy of Loet Leydesdorff to the Triple Helix as a Theory of Innovation,” Triple Helix, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–27, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Blasco, I. Brusca, and M. Labrador, “Drivers for universities’ contribution to the sustainable development goals: An analysis of Spanish public universities,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Luekveerawattana, “Enhancing innovation in cultural heritage tourism: navigating external factors,” Cogent Soc Sci, vol. 10, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Aliedan, I. A. Elshaer, M. A. Alyahya, and A. E. E. Sobaih, “Influences of University Education Support on Entrepreneurship Orientation and Entrepreneurship Intention: Application of Theory of Planned Behavior,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 20, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Soria-Barreto, S. Ruiz-Campo, A. S. Al-Adwan, and S. Zuniga-Jara, “University students intention to continue using online learning tools and technologies: An international comparison,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 24, 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Mohamad, M. D. Akanmu, V. Ponnusamy, S. Yahya, and N. Omar, “Measuring Malaysian youth leadership competencies: validation and development of instrument,” Cogent Soc Sci, vol. 10, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. H. Liang, “Cultural friction during intercultural service encounters with Chinese tourists: perspectives from hotel employees in Australia,” Cogent Soc Sci, vol. 10, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Marin-Pantelescu, L. Tăchiciu, I. Oncioiu, and M. Ștefan-Hint, “Erasmus Students’ Experiences as Cultural Visitors: Lessons in Destination Management,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Bakker, E. Demerouti, A. Sanz-Vergel, and A. Rodríguez-Muñoz, “La Teoría de las Demandas y Recursos Laborales: Nuevos Desarrollos en la Última Década,” Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, vol. 39, no. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. M. De Sancha-Navarro, J. Lara-Rubio, M. D. Oliver-Alfonso, and L. Palma-Martos, “Cultural sustainability in university students’ flamenco music event attendance: A neural networks approach,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 5, 2021. [CrossRef]

- O. Balaeva, Y. Rodionova, A. Yakovlev, and A. Tkachenko, “Public Procurement Efficiency as Perceived by Market Participants: The Case of Russia,” International Journal of Public Administration, vol. 45, no. 16, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Khorana, S. Caram, and N. P. Rana, “Measuring public procurement transparency with an index: Exploring the role of e-GP systems and institutions,” Gov Inf Q, vol. 41, no. 3, p. 101952, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Romanelli, “Sustaining Change within Technology-Oriented Public Organizations,” in Strategica: Upscaling Digital Transformation in Business and Economics, 2019.

- H. Benito Mundet et al., “Multidimensional research on university engagement using a mixed method approach,” Educacion XX1, vol. 24, no. 2, 2021. [CrossRef]

- UNCITRAL, “UNCITRAL Model Law on Public Procurement,” 2014. [Online]. Available: www.uncitral.org.

- OMC, “Acuerdo sobre Acuerdo sobre contratación pública contratación pública,” 2012. Accessed: Jun. 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/gproc_e/gp_gpa_e.htm.

- ISO 20400, “ISO 20400:2017 Sustainable procurement — Guidance,” 2017. Accessed: Jun. 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.iso.org/standard/63026.html.

- INTOSAI, “Coordinación y Cooperación entre las EFS y los Auditores Internos en el Sector Público,” 2014. [Online]. Available: www.issai.org.

- MAPS, “Detailed Analysis Indicator Matrix,” 2020, Accessed: Jun. 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mapsinitiative.org/.

- OECD, “Managing risks in the public procurement of goods, services and infrastructure,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions/.

- OECD, “Public procurement performance: A framework for measuring efficiency, compliance and strategic goals,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions/.

- J. Krogstie, “Quality of Models,” in Model-Based Development and Evolution of Information Systems, Springer London, 2012, pp. 205–247. [CrossRef]

- Banco Mundial, “Open Contracting Data Standard,” 2022. Accessed: Jun. 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://documentos.bancomundial.org/es/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/744551614955316901/open-contracting-data-standard.

- EITI standard, “The global standard for the good governance of oil, gas and mineral resources,” 2023. Accessed: Jun. 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://eiti.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/ES%20EITI%20Standard.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).