Submitted:

18 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Actors and strategies in SPP

2.2. Strategies, Purposes, and Barriers in SPP

2.3. Purposes and Sustainability in PP

3. Method

4. Results and Discussions

5. Conclusions

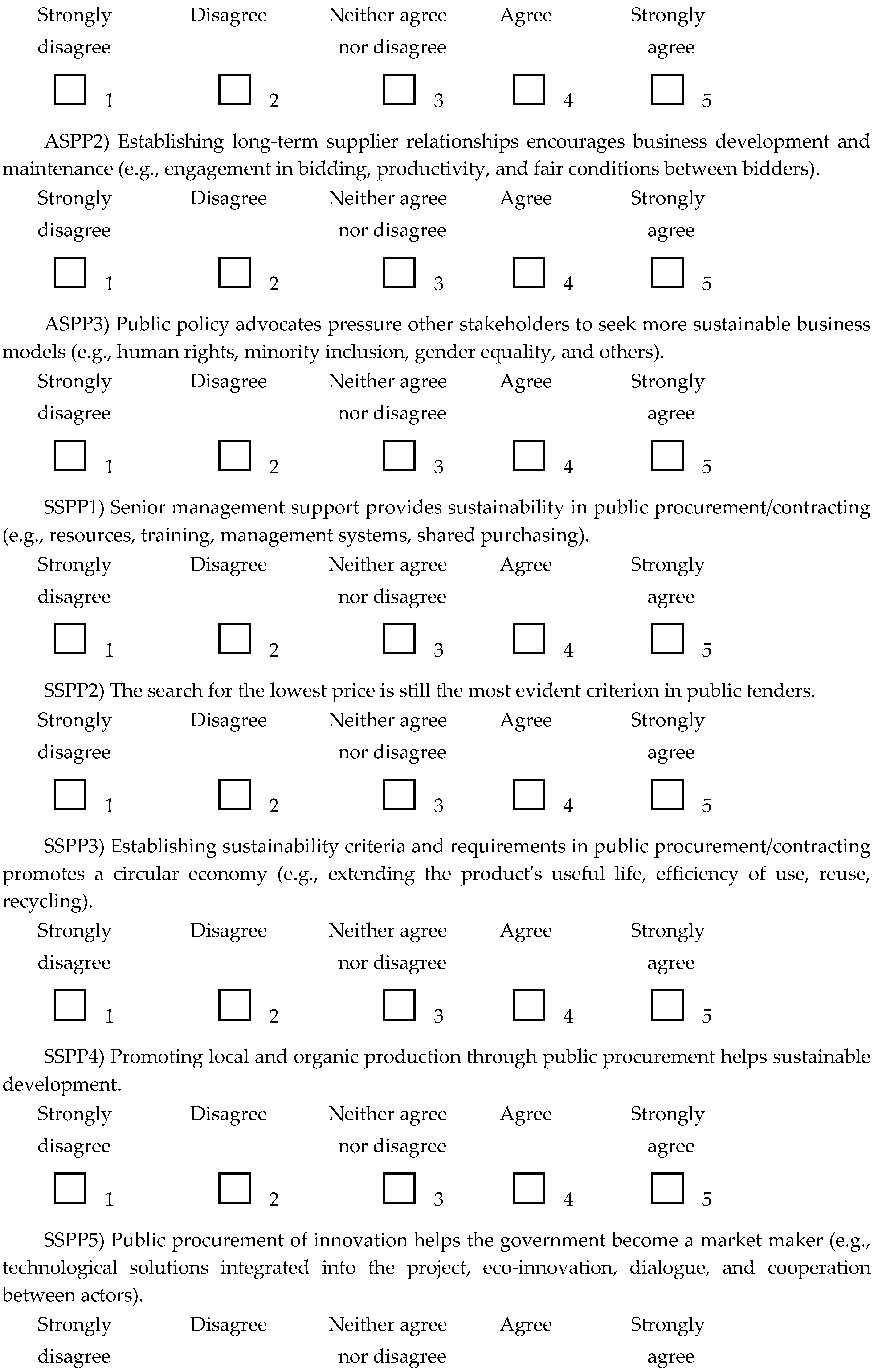

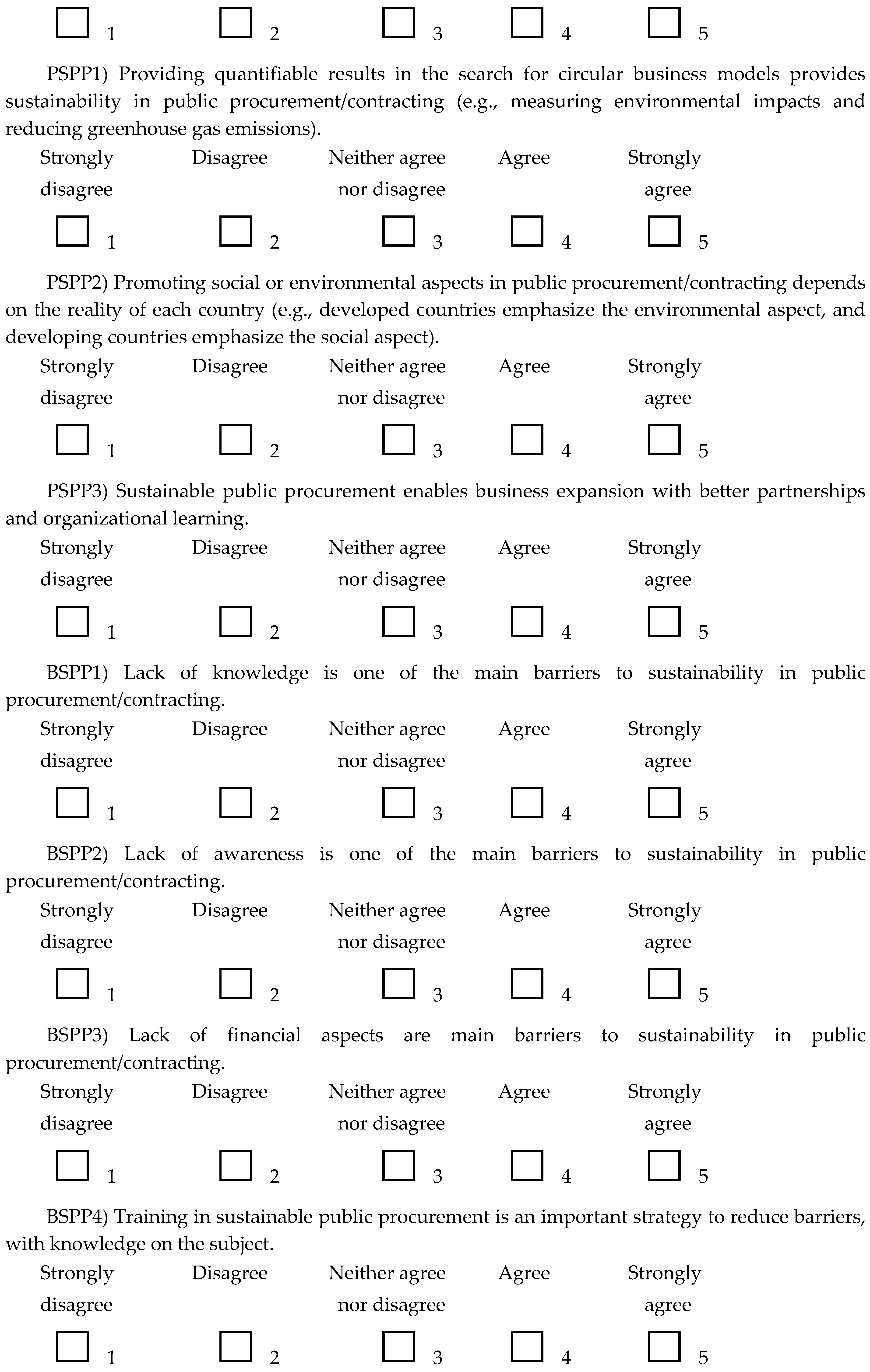

Appendix A. Questionnaire: Research: Sustainable Public Procurement

References

- Benchekroun, H. , Benmamoun, Z. and Hachimi, H. (2024), “Sustainable public procurement for supply chain resilience and competitive advantage”, Acta Logistica, Vol. 11 No. 03, pp. 349–360. [CrossRef]

- Calvacanti, D. , Oliveira, G., d’ Avignon, A., Schneider, H. and Taboulchanas, K. (2017), “Compras públicas sustentáveis: diagnóstico, análise comparada e recomendações para o aperfeiçoamento do modelo brasileiro”, p. 68.

- Santos, F. , Hilletofth, P. and von Haartman, R. (2025), “Managing Organisational Changes for Collaboration Between Stakeholders in Sustainable Public Procurement”, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.L. , Hewitt, R.J. and Hernández-Jiménez, V. (2023), “Can public food procurement drive agroecological transitions? Pathways and barriers to sustainable food procurement in higher education institutions in Spain”, Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, Vol. 47 No. 10, pp. 1488–1511. [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W. , Eustachio, J.H.P.P., Caldana, A.C.F., Will, M., Lange Salvia, A., Rampasso, I.S., Anholon, R., et al. (2020), “Sustainability Leadership in Higher Education Institutions: An Overview of Challenges”, Sustainability, Vol. 12 No. 9, p. 3761. [CrossRef]

- Daskalova-Karakasheva, M. , Zgureva-Filipova, D., Filipov, K. and Venkov, G. (2024), “Ensuring Sustainability: Leadership Approach Model for Tackling Procurement Challenges in Bulgarian Higher Education Institutions”, Administrative Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 9, p. 218. [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, R.C.A. , Pedrosa, I. V. and Camara, M.A.O.A. (2021), “Sustainable public procurement in a Brazilian higher education institution”, Environment, Development and Sustainability, Vol. 23 No. 11, pp. 17094–17125. [CrossRef]

- Lagström, C. and Ek Österberg, E. (2024), “Exploring Sustainable Public Procurement Through Regulatory Conversations”, Financial Accountability & Management. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L. , Umair Ashraf, R., Ahtisham ul Haq, M. and Fan, X. (2022), “Hurdles on the Way to Sustainable Development in the Education Sector of China”, Sustainability, Vol. 15 No. 1, p. 217. [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, T. , Cravero, C., La Chimia, A. and Quinot, G. (2019), “Multidimensionality of Sustainable Public Procurement (SPP)—Exploring Concepts and Effects in Sub-Saharan Africa and Europe”, Sustainability, Vol. 11 No. 22, p. 6352. [CrossRef]

- Ciumara, T. and Lupu, I. (2020), “Green Procurement Practices in Romania: Evidence from a Survey at the Level of Local Authorities”, Sustainability, Vol. 12 No. 23, p. 10169. [CrossRef]

- Uyarra, E. , Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J.M., Flanagan, K. and Magro, E. (2020), “Public procurement, innovation and industrial policy: Rationales, roles, capabilities and implementation”, Research Policy, Vol. 49 No. 1, p. 103844. [CrossRef]

- Morley, A. (2021), “Procuring for change: An exploration of the innovation potential of sustainable food procurement”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 279, p. 123410. [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, P. and Gomes, R.C. (2019), “Can public procurement be strategic? A future agenda proposition”, Journal of Public Procurement, Vol. ahead-of-p No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, F.P. , Fanelli, S., Lanza, G. and Milone, M. (2021), “Public food procurement for Italian schools: results from analytical and content analyses”, British Food Journal, Vol. 123 No. 8, pp. 2936–2951. [CrossRef]

- Braulio-Gonzalo, M. and Bovea, M.D. (2020), “Criteria analysis of green public procurement in the Spanish furniture sector”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 258, p. 120704. [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Zapana, M. , Yagüe, J.L., De Nicolás, V.L. and Ramirez, A. (2020), “Benefits of public procurement from family farming in Latin-AMERICAN countries: Identification and prioritization”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 277, p. 123466. [CrossRef]

- Wittman, H. and Blesh, J. (2017), “Food Sovereignty and F ome Z ero : Connecting Public Food Procurement Programmes to Sustainable Rural Development in B razil”, Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 81–105. [CrossRef]

- Valencia, V. , Wittman, H., Jones, A.D. and Blesh, J. (2021), “Public Policies for Agricultural Diversification: Implications for Gender Equity”, Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, Vol. 5. [CrossRef]

- Alhola, K. , Ryding, S.O., Salmenperä, H. and Busch, N.J. (2019), “Exploiting the Potential of Public Procurement: Opportunities for Circular Economy”, Journal of Industrial Ecology, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 96–109. [CrossRef]

- Etse, D. , McMurray, A. and Muenjohn, N. (2021), “Comparing sustainable public procurement in the education and health sectors”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 279, p. 123959. [CrossRef]

- Paes, C.O. , Zucoloto, I.E., Rosa, M. and Costa, L. (2020), “PRÁTICAS, BENEFÍCIOS E OBSTÁCULOS NAS COMPRAS PÚBLICAS SUSTENTÁVEIS: UMA REVISÃO SISTEMÁTICA DE LITERATURA”, Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 21–39. [CrossRef]

- Da Silveira, V.A. , Da Costa, S.R.R. and Resende, D. (2022), “Blockchain Technology in Innovation Ecosystems for Sustainable Purchases through the Perception of Public Managers”, WSEAS TRANSACTIONS ON BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS, Vol. 19, pp. 790–804. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.V. de S.S., Simão, J. and Caeiro, S.S.F. da S. (2020), “Stakeholders’ categorization of the sustainable public procurement system: the case of Brazil”, Journal of Public Procurement, Vol. 20 No. 4, pp. 423–449. [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, B.B.F. and Da Motta, A.L.T.S. (2019), “Key factors hindering sustainable procurement in the Brazilian public sector: A Delphi study”, International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, Vol. 14 No. 02, pp. 152–171. [CrossRef]

- Delmonico, D. , Jabbour, C.J.C., Pereira, S.C.F., de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L., Renwick, D.W.S. and Thomé, A.M.T. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, F. , Annunziata, E., Iraldo, F. and Frey, M. (2016), “Drawbacks and opportunities of green public procurement: an effective tool for sustainable production”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 112, pp. 1893–1900. [CrossRef]

- Jeireisssati, L.C. and Melo, A.J.M. Sustainable public procurement and implementation of goal 12.7 of sustainable development goals (SDGs) in Brazil: advances and backwards. Brazilian Journal of Public Policy, 2020; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hair Jr., J. F., Black, W.C., Bardin, B.J., Anderson, R.E., 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7 ed. Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

- de Guimarães, J.C.F. , Severo, E.A., Jabbour, C.J.C., de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L. and Rosa, A.F.P. (2021), “The journey towards sustainable product development: why are some manufacturing companies better than others at product innovation?”, Technovation, Vol. 103, p. 102239. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F. Jr., W. C. Black, B. J. Bardin, and R. E. Anderson. 2014. Multivariate Data Analysis, P: New International Edition. 7th ed. New York.

- De Maesschalck, R. , Jouan-Rimbaud, D., Massart, D.L., 2000. The mahalanobis dis tance. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst. 50 (1), 1e18.

- Marôco, J. (2010). Análise de equações estruturais: fundamentos teóricos, softwares & aplicações.

- Kline, R.B. 2023. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 5 ed. The Guilford Press. New York.

- Bentler, P.M. (1990), “Comparative fit indexes in structural models.”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 107 No. 2, pp. 238–246. [CrossRef]

- MARDIA, K. V. (1971), “The effect of nonnormality on some multivariate tests and robustness to nonnormality in the linear model”, Biometrika, Vol. 58 No. 1, pp. 105–121. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. & Larcker, D.F. (1981) Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, Available at. [CrossRef]

- Severo, E.A. , de Guimarães, J.C.F. and Henri Dorion, E.C. (2018), “Cleaner production, social responsibility and eco-innovation: Generations’ perception for a sustainable future”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 186, pp. 91–103. [CrossRef]

- BOLLEN, K.A. (1989), “A New Incremental Fit Index for General Structural Equation Models”, Sociological Methods & Research, Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 303–316. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P. and Marsh, H.W. (1990), “Choosing a multivariate model: Noncentrality and goodness of fit.”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 107 No. 2, pp. 247–255. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, J.S. and Huba, G.J. (1985), “A fit index for covariance structure models under arbitrary GLS estimation”, British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, Vol. 38 No. 2, pp. 197–201. [CrossRef]

- Muduli, K. kanta, Luthra, S., Kumar Mangla, S., Jabbour, C.J.C., Aich, S. and de Guimarães, J.C.F. (2020), “Environmental management and the ‘soft side’ of organisations: Discovering the most relevant behavioural factors in green supply chains”, Business Strategy and the Environment, Vol. 29 No. 4, pp. 1647–1665. [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R. E. , and R. G. Lomax. 2010. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Routledge Academic.

- Xia, Y. and Yang, Y. (2019), “RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods”, Behavior Research Methods, Vol. 51 No. 1, pp. 409–428. [CrossRef]

- Novaes das Virgens, T.A. , Andrade, J.C.S. and Hidalgo, S.L. (2020), “Carbon footprint of public agencies: The case of Brazilian prosecution service”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 251, p. 119551. [CrossRef]

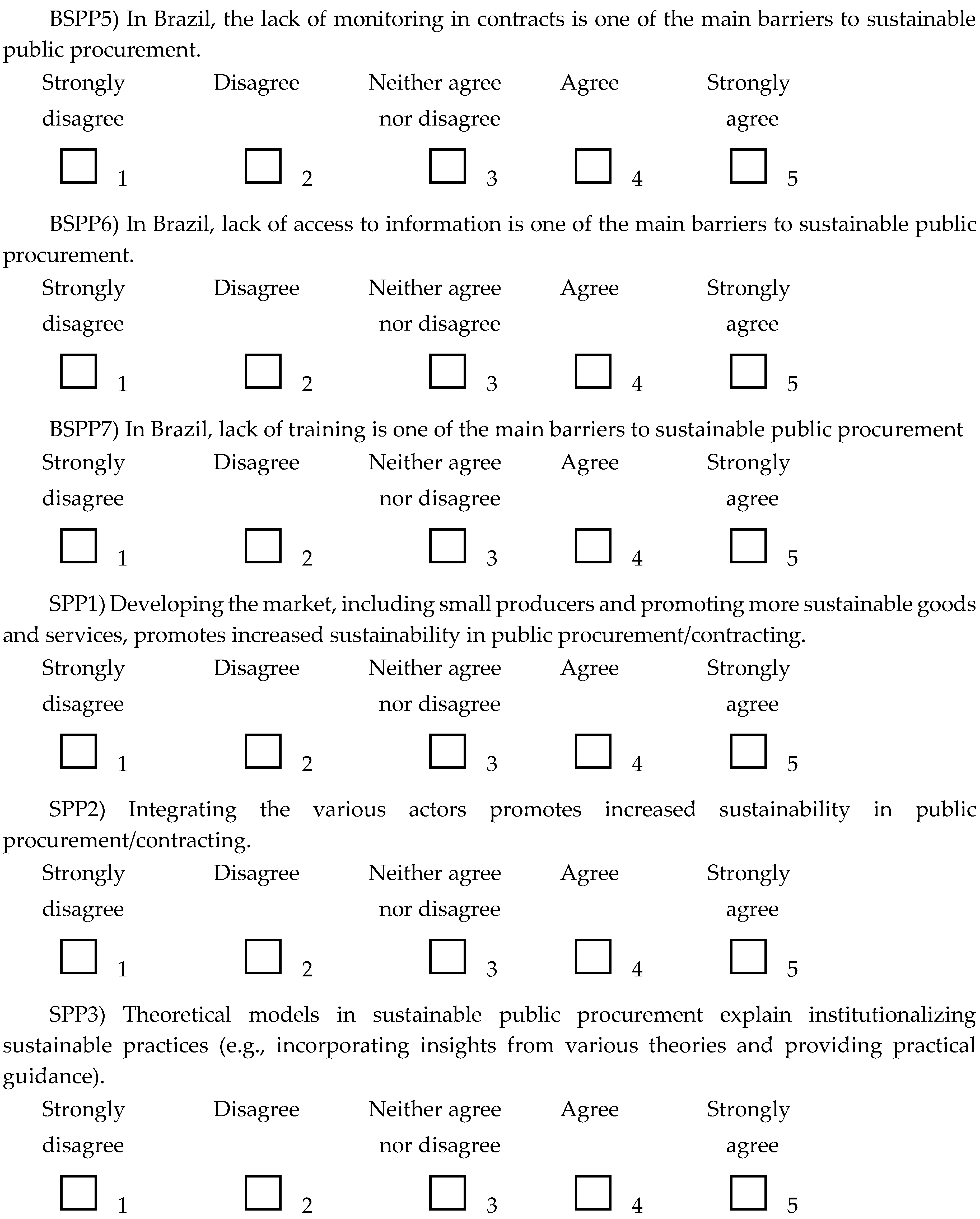

| Constructs and observable variables (Appendix A) | References |

|---|---|

|

Actors in SPP (ASPP) ASPP1; ASPP2; ASPP3 |

(Alhola et al., 2019; Morley, 2021; Oliveira et al., 2020; Salvatore et al., 2021; Stoffel et al., 2019; Testa et al., 2016) |

|

Strategies in SPP (SSPP) SSPP1; SSPP2; SSPP3; SSPP4; SSPP5 |

(Alhola et al., 2019; Braulio-Gonzalo and Bovea, 2020; Cervantes-Zapana et al., 2020; Morley, 2021; Novaes das Virgens et al., 2020; Testa et al., 2016) |

|

Purposes in SPP (PSPP) PSPP1; PSPP2; PSPP3; |

(Alhola et al., 2019; Braulio-Gonzalo and Bovea, 2020; De Giacomo et al., 2019; c et al., 2021) |

|

Barriers in SPP (BSPP) BSPP1; BSPP2; BSPP3; BSPP4; BSPP5; BSPP6; BSPP7 |

( Da Costa and Da Motta, 2019; Paes et al., 2020) |

|

Sustainability in PP (SPP) SPP1; SPP2; SPP3 |

(Morley, 2021; Novaes das Virgens et al., 2020) |

| Constructs | Mean | SD* | Fator loading |

Communality | Cronbach’s Alpha |

KMO* | Composite Reliability |

Convergent Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (EFA) | ,866 |

,835 |

0,941 |

0,5 |

||||

| ASPP1 | 4,321 |

0,969 |

0,582 |

,645 |

,564 | ,590 |

0,658 |

0,392 |

| ASPP2 | 3,921 |

0,963 |

0,468 |

,590 |

||||

| ASPP3 | 3,648 |

1,162 |

0,575 |

,378 |

||||

| SSPP1 | 4,297 |

0,995 |

0,560 |

,480 |

,633 |

0,740 | 0,755 | 0,43 |

| SSPP2 | 4,358 |

0,862 |

0,025 |

,995 |

||||

| SSPP3 | 4,424 |

0,828 |

0,681 |

,628 |

||||

| SSPP4 | 4,515 |

0,762 |

0,672 |

,630 |

||||

| SPP5 | 4,279 |

0,845 |

0,739 |

,588 |

||||

| PSPP1 | 4,303 |

0,768 |

0,679 |

,665 |

,563 |

0,578 | 0,594 | 0,36 |

| PSPP2 | 3,861 |

1,152 |

0,211 |

,354 |

||||

| PSPP3 | 4,194 |

0,903 |

0,597 |

,595 |

||||

| BSPP1 | 4,479 |

0,770 |

0,587 |

,430 |

,793 |

,828 |

0,862 | 0,48 |

| BSPP2 | 4,309 |

0,935 |

0,715 |

,574 |

||||

| BSPP3 | 3,873 |

1,127 |

0,465 |

,307 |

||||

| BSPP4 | 4,721 |

0,569 |

0,470 |

,295 |

||||

| BSPP5 | 3,867 |

1,102 |

0,591 |

,434 |

||||

| BSPP6 | 3,945 |

1,100 |

0,657 |

,534 |

||||

| BSPP7 | 4,242 |

0,970 |

0,700 |

,587 |

||||

| SPP1 | 4,467 |

0,761 |

0,714 |

,612 |

,711 |

0,672 |

0,802 | 0,57 |

| SPP2 | 4,576 |

0,606 |

0,648 |

,675 |

||||

| SPP3 | 4,164 |

0,857 |

0,643 |

,615 |

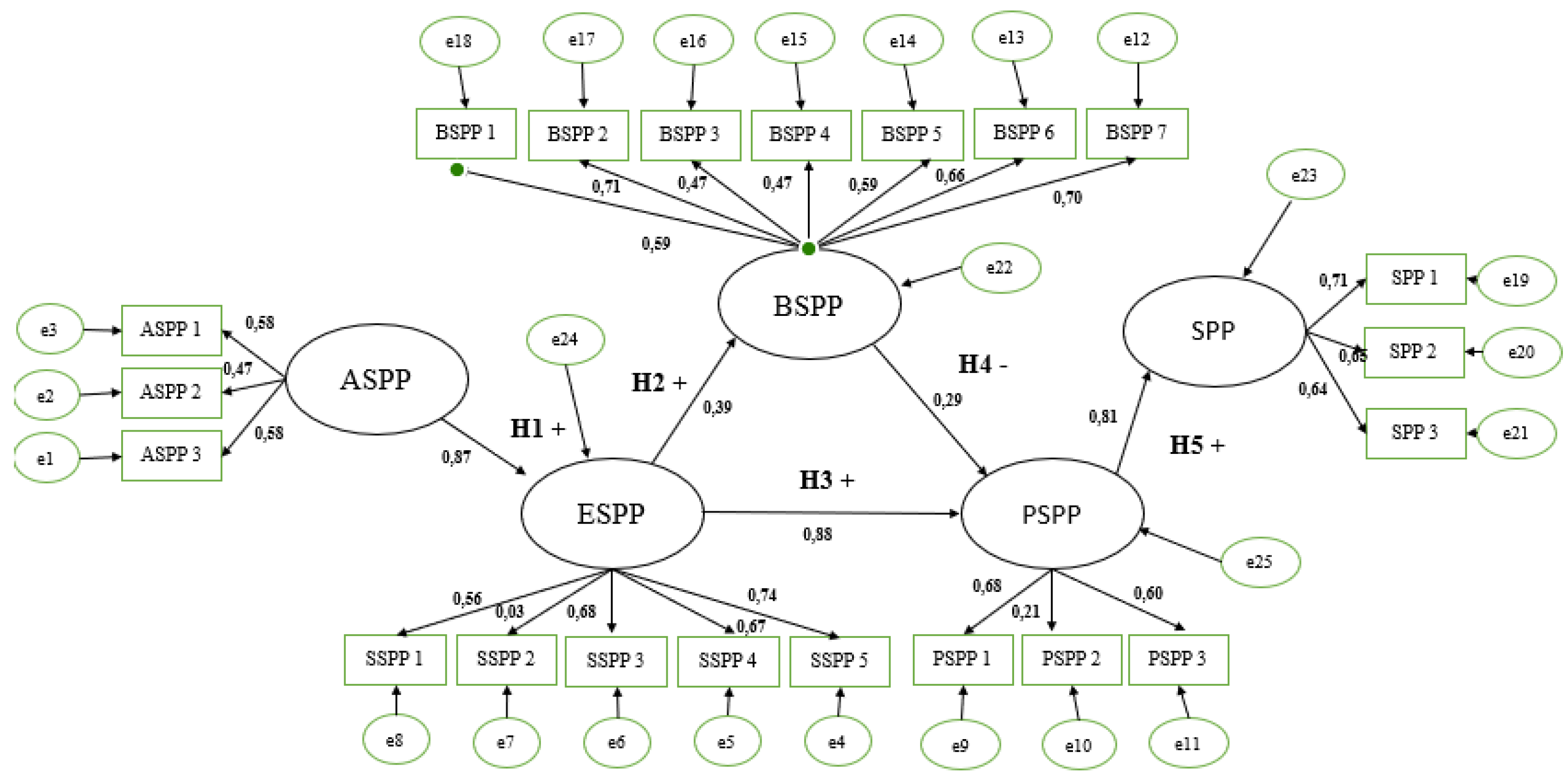

| Hypotheses | Description | Standardised regression weights | Intensity | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | The ASPP positively influences SSPP | 0,870 |

high intensity | confirmed |

| H2 | The SSPP positively influences PSPP | 0,882 |

high intensity | confirmed |

| H3 | The SSPP positively influences BSPP | 0,392 |

moderate intensity | confirmed |

| H4 | The BSPP negatively influences PSPP | 0,290 |

low intensity | confirmed |

| H5 | The PSPP positively influences SPP | 0,814 |

high intensity | confirmed |

| x2 | df | x2/df | CFI | NFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 360,193 |

184 | 1,958 | 0,828 |

0,708 |

0,076 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).