1. Introduction

Around the world, public procurement makes up an estimated 12–20% of gross domestic product, which makes it one of the most significant tools the government has for both economic influence but also leverages to advance sustainability objectives [

1]. The growth of Green Public Procurement (GPP) which is defined as integrating environmental criteria into purchasing decisions, has seen GPP recognized as a viable opportunity to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12 around responsible consumption and production [

2,

3]. GPP development promotes a shift toward demand for environmentally preferable goods, services, and works, while also encouraging new solutions, reducing greenhouse gases and boosting resource efficiency [

4,

5]. However, implementation remains uneven across countries and sectors, and developing economies have clearly the largest challenges.

The research field has identified both the opportunities and obstacles to GPP. On the one hand, there is evidence that strong legal frameworks, mobilized stakeholders, and effective green markets can promote faster adoption of GPP in developed economies, such as the EU, Japan, and South Korea [

6,

7,

8]. On the other hand, studies in developing contexts have consistently emphasized the importance of ongoing barriers to GPP, including poor institutional capacity, inadequate policy implementation, financial constraints and limited preparedness of suppliers [

9,

10,

11]. Some claim GPP can produce long-term cost savings and social co-benefits[

12] while others question whether it is feasible to implement GPP in resource-constrained settings with procurement decisions primarily driven by short-term price competitiveness [

13,

14]. This separate points towards the need for context-specific empirical work.

Nepal is a particularly useful example to study the drivers and barriers of GPP. Public procurement in Nepal, on average, has been noted to represent nearly 20% of GDP [

15], meaning there is an enormous opportunity to use procurement to create meaningful change toward sustainable development. However, GPP has only begun to develop and is in its infancy, as there is no specific legal framework and only a collection of standalone, donor-funded initiatives to guide current practice [

16]. The absence of nationally institutionalized GPP policies, compounded by technical and market constraints, create an urgent need for multipronged approaches that respond to national governance, and economic considerations.

In light of the above, this study has two overall objectives:

(i) to conceptually understand the drivers and barriers to GPP in Nepal by utilizing a survey of stakeholders and binary logistic regression, and

(ii) to generate a strategic approach for implementing GPP based on empirical data and international best practices.

The findings, will help to highlight wider enabling and constraining influences such as growth in renewable energy as a driver and lack of e-training, training, and legal frameworks as barriers, and specific steps to incorporate GPP into national procurement systems. While this study applies to the national context of Nepal, we believe the findings contribute to wider discussions of sustainability governance and lessons for other developing economies addressing similar challenges.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The study used a mixed-methods approach, merging a structured literature review with a quantitative questionnaire, in order to identify critical drivers and barriers of Green Public Procurement (GPP) implementation in Nepal. The mixed-methods approach allowed for the examination of theoretical knowledge acquired via global experiences and emperical evidence sourced from national stakeholders, and for a comprehensive strategy to be developed that recognized the contextual specificities. The research philosophy was pragmatism, recognizing that sustainability challenges are complex and decisions are driven by methodological pluralism.

2.2. Study Area and Population

The study on public procurement in Nepal focuses on the existing law of public procurement applicable to government contracting, the Public Procurement Act(2007) and Public Procurement Regulation(2007). We interviewed those agencies that were expected to conduct procurement activities including the Department of Roads(DoR), the Department of Urban Developement and Building Construction(DUDBC), the Ministry of Energy, Water Resources, and Irrigation (MoEWRI), the Minsitry of Water Supply(MoWS), and the Public Procurement Monitoring Office(PPMO).

The target population for the research consisted of some of the poeple who were working with the procurement, policy, and sustainability: government officials, procurement officers, environmental experts, consultants, and academics.

2.3. Sampling and Respondents

We used purposive sampling to limit people with relevant knowledge and experience in procurement, leaving us with 74 valid responses. In this study, a 90% confidence interval (CI) and a 10% margin of error (MoE) were adopted. As in any other quantitative analysis, the assumed standard setting of confidence, except in those that are exceptions, is that the level is taken to be 95%, while in the current study, it is exploratory the 90% level was due to logistic barriers towards accessing this population [

17,

18]. The 10% margin of error was selected as a practical compromise between precision and the feasibility of collecting responses [

18].

2.4. Data Collection

Two main methods of data collection were carried out:

Literature Review: Secondary data was collected from books, journal articles, reports, and government documents to create inital list of GPP drivers and barriers.

Questionnaire Survey: A structured questionnaire was developed based on review. Participants were asked to ratethe importance of each driver and barriers on a five-point Likert Scale, where 1= not significant and 5= extremely significant. The Likert Scaling method has been extensively used in attitudinal and management studies [

18]. The survey was conducted physically and electronically from June to September 2024.

2.5. Data Analysis

The survey data was analyzed in SPSS. Cronbach's alpha was calculated for internal consistency, which were each more than 0.7, indicating acceptable reliability [

19].

Afterwards, the RII method was applied to rank the drivers and barriers. RII is often used in construction management and procured studies because it ranks perceived factors according to the respondents [

20]. The formula is:

where:

W = Weight assigned to each response (e.g., 5 for "Strongly Agree", 4 for "Agree", etc.)

f = Frequency of responses for each weight, A = Maximum weight (5 in this case)

N = Total number of respondents (74)

2.6. Framework Development

The framework for GPP implementation was developed by grouping the drivers and barriers in thematic categories: policy/legal, organizational, technical, financial, and market-related. The process of developing a context-specific strategic framework involved merging survey findings with contemporary insights from previous research (all within the context of Nepal) [

4,

9].

2.7. Ethical Consideration

Participation in the study was completely voluntary. Respondents were informed of the purpose of the research and assured of confidentiality and anonymity. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee of United Technical College, Pokhara University, prior to data collection.

2.8. Data Availability

The data that supports this study, including the anonymized questionnaire responses and analysis outputs, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

3. Results

In this section, the findings are presented from this analysis and detail the drivers, barriers, and the proposed conceptual framework for the implementation of GPP in Nepal. The data were collected primarily from a structured questionnaire based survey of 74 purposively sampled stakeholders and a literature review. The Relative Importance Index (RII) method was employed to rank the level of significance of various factors according to stakeholder perceptions.

3.1. Drivers of GPP Implementation

The uptake and practice of GPP in Nepal is dictated by a complex and varied number of factors that include the drivers of Organizational, Market, Legal, Environmental, Technical and Economic/Financial. The RII analysis shown in

Table 1 has enabled the ranking of these driver categories and provided some quantifiably evidence of their significance.

According to the findings indicated in

Table 1, Legal Drivers was recognized as the most impactful category (RII = 0.772072), emphasizing the importance of strong regulatory frameworks and compliance with international obligations in advancing GPP. The following driver that was found to be important is the category of Environmental Drivers (RII = 0.766667), which indicates the priority given to sustainability and the preservation of the environment in the country. The drivers of Market (RII = 0.764189) and Economic/Financial (RII = 0.758378) were also recognized with high importance (RII), acknowledging the influence of demand-supply pressure and cost considerations for environmental benefit. Organizational Drivers (RII = 0.758108) and Technical Drivers (RII = 0.722973) were notably the least important, and potentially are areas that could see more development.

A further disaggregation and analysis of 21 specific drivers is found in

Table 2. This further analysis provides insights into the factors and conditions supporting the adoption of GPP in Nepal.

The results presented in

Table 2 show that Renewable Energy Growth is the most influential driver (RII = 0.81081, Rank 1), highlighting Nepal's substantial investments in hydropower and solar energy projects, which contribute to global SDG-7. The second rank is shared by Focus on Sustainable Development and Forestry and Biodiversity Conservation; both represent RII of 0.78919 (Ranking 2), confirming Nepal's priorities in the 2030 Agenda and commitment to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Life-Cycle Cost Analysis and Financial Incentives (both RII = 0.77568, Rank 4) were also significant drivers, confirming that environmental sustainability through sustainable procurement practices is both economically attractive as a motivator and also a promising viable option for long term return on investment. The four highest ranked drivers noted emphasize the strategic import of GPP as a new purchase method that supports national priorities on supporting environmental sustainability and economic resilience.

Individual drivers in the medium range depict Institutional Support (RII = 0.77297, Rank 6) as critical to establishing systems and leadership. Disaster Risk Management (RII = 0.76486, Rank 7), and International Treaties (RII = 0.76486, Rank 7) highlight an aspect of Nepal's vulnerabilities to natural disasters, and some level of environmental agreement with the global community, is a fact. Also found in the medium range, Private Sector Involvement (RII = 0.76216, Rank 9) and Environmental Regulations (RII = 0.76216, Rank 9) suggest that the private sector is becoming a bigger player, and regulation is necessary. Notably, lower ranked drivers such as International Trade (RII = 0.72973, Rank 20), and Technical Know-How from INGOs (RII = 0.70000, Rank 21) highlighted areas in which influence does not exist or where more effort is needed to utilize them as possible areas of influence on GPP. Overall, the results indicated that while legal, environmental, and economic issues greatly progress GPP, organizational and technical betterment is required.

3.2. Barriers of GPP Implementation

Even with established drivers, Nepal continues to face significant barriers to effective GPP implementation. These barriers were categorized as Organizational, Market, Legal, Technical, and Economic/Financial. RII analysis is shown in

Table 3 of the overall ranking for the categories of barriers.

As shown in

Table 3, Organizational Barriers (RII = 0.778919, Rank 1) are the most significant challenges that include internal issues related to a lack of awareness, resistance to adopt, and institutional capacity limitations among public bodies. Legal Barriers (RII = 0.776577, Rank 2) and the Technical Barriers (RII = 0.776351, Rank 3) also have significant challenges related to the regulatory framework and lack of technical expertise. Market Barriers (RII = 0.754054, Rank 4) represents lack of green products available while Economic/Financial Barriers (RII = 0.751351, Rank 5) is also important due to cost and budget constraints.

A further detailed analysis of 22 barriers is presented below in

Table 4.

The most significant barrier identified is Limited GPP Training Programs (RII = 0.81081, Rank 1), highlighting a critical need for capacity building among procurement professionals. This is closely followed by No Internal GPP Policies (RII = 0.80000, Rank 2) and Lack of Legal Framework (RII = 0.79730, Rank 3), emphasizing the absence of strategic guidance and clear regulations for GPP implementation. Other high-ranking barriers include Lack of Knowledge and Awareness of GPP and Inadequate Standards (both RII = 0.78919, Rank 4), which indicates that there are critical gaps in understanding as well as technical benchmarks.

Mid-tier barriers include Technological Gap Hinders GPP (RII = 0.78108, Rank 6) and Regulatory Barriers (RII = 0.77838, Rank 7) which relates to being able to utilize innovative products and processes and navigating existing legal obstacles. Some of the barriers, Lack of Green Product Suppliers and Market Uncertainties (both RII = 0.77568, Rank 8) emphasizes the issues resulting from the undeveloped green markets in Nepal and the overall competitive context of sustainable products. Finally, we observe on the low tier Scarcity of Green Products (RII = 0.70000, Rank 22) which highlights the overall infancy of the green market. Barriers related to Economic/financial factors, such as Budget Constraints Limit GPP (RII = 0.75676, Rank 14), Limited Budget (RII = 0.76216, Rank 13), Highest Initial Costs of GPP (RII = 0.74595, Rank 19) show financial pressures despite long term benefits. In summary, these findings illustrate the complicated nature of barriers and the need for a comprehensive approach to managing GPP in Nepal.

3.3. Strategic Framework for GPP Implementation

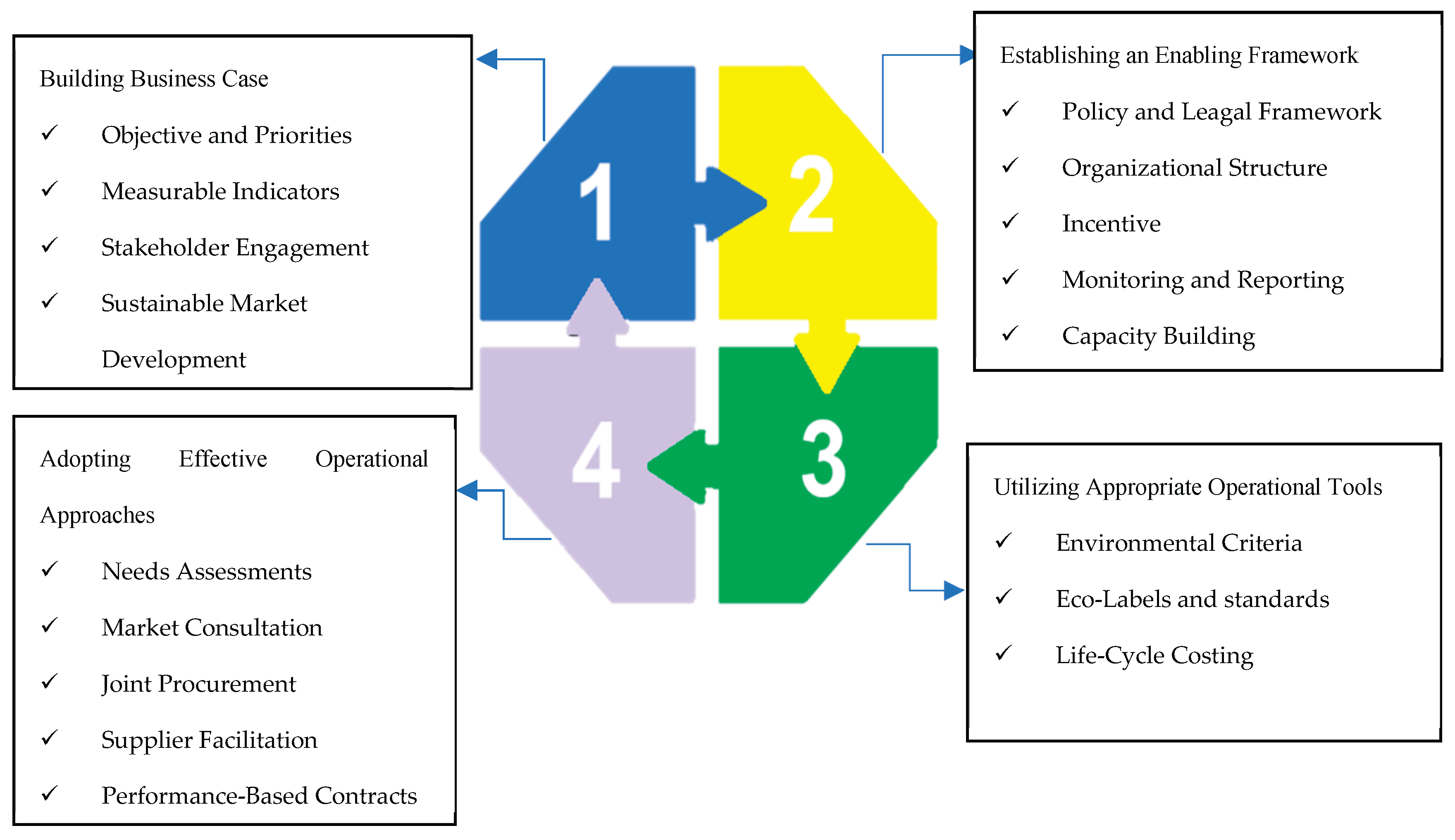

Based on international best practice and in the context of Nepal-the framework for implementing Green Public Procurement (GPP) - provides the foundation for developing a clear plan for transitioning to a GPP policy, within the procurement system in Nepal, indicates that a more holistic approach is required to promote the successful uptake and implementation of GPP. The four main pillars identified within this framework are; the business case, the enabling framework, the operational tools, and the operational approaches.

Figure 1.

Core Pillars of GPP Implementation Framework. (Source: Modified from World Bank Report "Green Public Procurement: An Overview of Green Reforms in Country Procurement Systems" [

21]).

Figure 1.

Core Pillars of GPP Implementation Framework. (Source: Modified from World Bank Report "Green Public Procurement: An Overview of Green Reforms in Country Procurement Systems" [

21]).

3.3.1. Policy and Legal Framework

This component focuses on establishing a sound legal framework by embedding mandatory sustainability criteria in laws and regulations, clarifying roles, and ensuring accountability and transparency. A policy component could be a comprehensive GPP law that requires mandatory sustainability criteria, environmental impact assessments, life-cycle costing, and ecolabels, that aligns with the country's sustainability goals.

3.3.2. Capacity Building

This component focuses on doing what is needed to support stakeholders. Capacity building includes developing comprehensive training for procurement officers, policy-makers, and suppliers which clearly state how to incorporate GPP principles into procurement, how to carry out life-cycle costing, use of ecolabels, and sustainfable practices, and developing national campaigns to build awareness about the benefits of GPP.

3.3.3. Market Development

This pillar addresses how to stimulate both the demand for, and the supply of, green products and services. The overall aim is ensure that there are policies in place to stimulate the production and supply of green products, support local purchasing, and provide incentives for eco-innovation. Market consultation is also key to understand supplier fees for green products, and the availability of green options.

3.3.4. Economic and Financial Mechanisms

This involves strategies to overcome cost barriers, and offer incentives. It includes a focus on utilizing life-cycle costing (LCC) approaches to measure the total costs and overall impact on the environment. It also features financial incentives such as tax cuts, grants, and subsidies for procurers and suppliers using sustainable products. Actions include dedicating a specific budget towards the GPP activity, and searching fron international partners for funding.

3.3.5. Monitoring and Evaluation

This is about monitoring instruments to measure what progress has been made, but also accountability and continuous improvement. It also includes how to put a fully monitoring and reporting system in place to monitor GPP implementation, set a period of regular reports, and collect data on progress, challenges has faced, and what lessons had been learnt from a national, regional, and local level. KPI's were another key point, but also independent auditing processes too.

3.3.6. Action Plan

The strategic framework also includes an Action Plan (

Table 5) that describes phases with actions, timelines, and responsible government organizations for objectives in the short term (1-3 years), medium term (3-7 years), and longer term (7+ years). This includes establishing the GPP Task Force, reviewing legal frameworks, developing GPP guidelines, undertaking pilot projects, and institutionalizing GPP at all levels of government.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine key elements and factors of success of Green Public Procurement (GPP) drawing on international practices, highlight drivers and barriers to GPP implementation in Nepal, and develop a strategic framework for the useful adoption of GPP. The results identify effective ways to improve Nepal's current public procurement while promoting environmental sustainability and economic resilience.

4.1. Drivers of Green Public Procurement Implementation

The analysis that employed the Relative Importance Index (RII) demonstrated that, in terms of influencing GPP implementation in Nepal, Legal Drivers were the most significant category, followed by Environmental Drivers, Market Drivers, Economic/Financial Drivers, Organizational Drivers, and Technical Drivers, which highlights the critical importance of strong regulatory frameworks and national commitments for advancing sustainable procurement practices in developing economies.

With respect to individual drivers, the most important driver was Renewable Energy Growth (RII = 0.81081), which corresponds with Nepal's significant hydropower potential and the increase in solar power investments, and supports international commitments beyond the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7: Affordable and Clean Energy, as well as Nepal's Long-Term Strategy for Net Zero Emissions by 2050. This finding also resonates with a worldwide perspective of GPP being a driver for expanding renewable energy, as demonstrated by Kenya's focus on developing solar and wind energy projects.

Rounding out the top four influences were Focus on Sustainable Development (RII = 0.78919) and Forestry and Biodiversity Conservation (RII = 0.78919). The fact that Nepal is invested in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, especially with GPP specifically supporting SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), implies that GPP policy changes are occurring as part of a broader policy shift integrating sustainability into our hands for far more than green procurement. Furthermore, the policies focused in biodiversity conservation are indicative of Nepal’s ecological wealth and also a commitment it has made under the auspices of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The strong alignment made with Nepal’s national focused sustainability efforts aligns strongly with Bhutan’s successful GPP implementations. An interesting parallel can be drawn between GPP integration aligned with bottom-line sustainability across sectors in Bhutan, while GPP is integrated with The Gross National Happiness (GNH) philosophy for both environmental and cultural preservation in their gross regional happiness, to generate awareness on that front.

Both Life-Cycle Cost Analysis (LCC) and Financial Incentives were relative to one another as the 5th influence (RII = 0.77568), suggesting a growing awareness about the associated long-term economic returns of procurements and apparent need for supportive financial mechanisms – which scenario aligns with OECD recommendations for sustainable procurement. That said, LCC as an effective alternative to deciding what to give by price for regionally relevant, is also widely held globally. Countries such as South Korea, Japan, and Bhutan all showcase just how LCC can yield significant cost savings and a reduced environmental footprint in shifting decision making from initial purchase price to total life cycle costs. More than often economic sensibly can be incentivizer behavior change toward greener alternatives, especially for regionally developing countries with less of a budget for green initiatives.

Institutional Support (RII = 0.77297) was also an important driver in Engaging with GPP, particularly the aspect of strong leadership, supporting frameworks, and inter-agency collaboration. This finding supports previous research that highlighted how influential support from senior levels of political and decision-makers is decisive for successful GPP implementation in public procurement and mainstreaming GPP.

On the other hand, Technical Know-How of INGOs (RII = 0.70000) was ranked the lowest driver. This could be interpreted as a lack of perceived influence or an evident gap of how to leverage international technical know-how effectively within Nepal, indicating may be a requirement for targeted and localized capacity-building approaches rather than just relying on the international transfer of knowledge.

4.2. Barriers of Green Public Procurement Implementation

The results of the study highlight Organizational Barriers as the most significant barriers to GPP implementation in Nepal, followed by other barrier types: Legal Barriers, Technical Barriers, Market Barriers, and Economic/Financial Barriers. This suggests that the internal barriers associated with institutional capacity and commitment are more foundational than economically driven external market or purely financial constraints.

Limited GPP Training Programs (RII = 0.81081) was the most substantial individual barrier. This significant lack of training indicates a critical capacity limitation amongst procurement professionals in Nepal which, in part, limits the ability to implement the principles of GPP when being asked to implement GPP and understand the opportunities arising from it. This is consistent with the global literature, which frequently identifies inadequate training and awareness is one of the key barriers to implementation of GPP in developing countries' contexts.

The second and third barrier types were No Internal GPP Policies (RII = 0.80000) and Lack of Legal Framework (RII = 0.79730). The absence of internal formal policies within public bodies indicates a lack of strategic direction and accountability of GPP initiatives. Similarly, the lack of enforcement of particular legal framework, namely no explicit guidelines or enforcement mechanism also served to undermine any form of obligatory practice for sustainable procurement. These findings also support previous studies which have noted the importance of clear and enforceable laws to institutionalize GPP; the findings of the research presented in this article are consistent with previous studies highlighting the importance of both internal policies for non-financial procurement and a combination of a capable law as an enabling condition for scalability and sustainability of GPP.

Lack of Knowledge and Awareness of GPP and Insufficient Standards (both RII = 0.78919) are also very significant barriers. This lack of knowledge prevents stakeholders from making sustainability a priority; in addition, having inconsistent or no clear standards for green products only adds to the confusion and inhibits procurement. This coincides with the UNEP asserting that the lack of knowledge and technical capacity from officials in procurement and suppliers is a substantial hurdle, especially in developing countries.

Technological Gap Hindering GPP (RII = 0.78108) and Regulatory Challenges (RII = 0.77838) are further barriers. The lack of updated tools like e-procurement systems, and the fact that regulations often overlap or contradict are less efficient and slowed down processes make it harder for GPP to be effectively integrated into procurement.

The limitation of suppliers of green products and uncertainty in the market (both RII = 0.77568) speaks to the early stages of the green market in Nepal. The lack of sustainable alternatives and unpredictability of the market work against public procurers and are consistent with barriers in other developing countries where being market-ready is an important problem. The barrier that was ranked lowest, Scarcity of Green Products (RII = 0.70000), indicates an immaturity in the market.

5. Conclusions

This research presents an overview of Green Public Procurement (GPP) in Nepal, integrating key elements and success factors from international experiences with some understanding of local drivers and barriers. The research concludes with the suggestion of a strategic framework to support GPP, underscoring its importance to national sustainability targets.

The study shows that GPP is a strategic approach to aligning public procurement within the frameworks of the environmental, social and economic priorities of the nation - in particular, linked to SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). Critical GPP elements and success factors from international settings, such as the existence of supporting legal frameworks, strategic planning, and capacity building, are identified as guiding principles for Nepal. In terms of empirical data, the drivers for GPP adoption in Nepal are, in order of rank: growth in renewable energy (RII = 0.81081), focus on sustainable development (RII = 0.78919), and forestry and biodiversity conservation (RII = 0.78919). These dimensions signify the largest environmental and developmental priorities for Nepal. The barriers to effective GPP implementation were primarily the limited number of GPP training programs (RII = 0.81081), the absence of any internal GPP policies (RII = 0.80000), and limited legal framework (RII = 0.79730).

The outcomes have important implications for policymakers and practitioners in Nepal and countries with similar developmental challenges. We recommend the following to build on the drivers and address the barriers:

Strengthening Policy and legal frameworks: Creating a GPP-specific law and amending impactsThe regulations to require sustainability criteria will provide clarity and accountability.

Capacity building and awareness raising: Capacity building and national awareness initiatives including targeted training of procurement professionals and procurement practitioners as well as stakeholders in GPP, is essential.

Building market development and incentives: Incentives and supports to local businesses to develop green/ sustainable products and create market information that is easily accessible to all could strengthen supply and demand for sustainable goods and services.

Effective implementation and monitoring: Developing pilot projects, clear monitoring and evaluation systems (with KPIs), and promoting life-cycle costing will ensure GPP initiatives are effective, transparent, and are improved on over time.

Adopting this approach to action will leverage Nepal’s public procurement system and have a meaningful impact on the Sustainable Development Goals for Nepal, particularly responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), will also support environmental stewardship, and build economic resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, and visualization, A.P. The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Institutional Review Committee of United Technical College, Pokhara University, Nepal.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the support of the professionals and stakeholders who participated in the survey. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI) for purposes of language refinement, structuring, and drafting support. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GPP |

Green Public Procurement |

| RII |

Relative Importance Index |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goal |

| DoR |

Department of Roads, Nepal |

| DUDBC |

Department of Urban Development and Building Construction, Nepal |

| MoEWRI |

Ministry of Energy, Water Resources, and Irrigation, Nepal |

| MoWS |

Ministry of Water Supply, Nepal |

| PPMO |

Public Procurement Monitoring Office, Nepal |

| LCC |

Life Cycle Costing |

| MoICS |

Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies, Nepal |

| KPI's |

Key Performance Indicators |

| CBD |

Convention on Biological Diversity |

| GNH |

Gross National Happiness |

| OECD |

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| INGOs |

International Non-Government Organizations |

References

- OECD. Government at a Glance 2021. OECD Publishing, Paris, 2021. [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Global Review of Sustainable Public Procurement. United Nations Environment Programme, 2017.

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: New York, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, F.; Annunziata, E.; Iraldo, F.; Frey, M. Drawbacks and Opportunities of Green Public Procurement: An Effective Tool for Sustainable Production. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Appolloni, A.; D’Amato, A.; Zhu, Q. Green Public Procurement, Missing Concepts and Future Trends—A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Public Procurement for a Better Environment. COM (2008) 400 Final, Brussels, 2008.

- Ministry of the Environment, Japan. Green Purchasing Law and Promotion of Eco-Friendly Goods. Tokyo, 2016.

- OECD. Public Procurement for Innovation: Good Practices and Strategies. OECD Publishing, Paris, 2017.

- Brammer, S.; Walker, H. Sustainable Procurement in the Public Sector: An International Comparative Study. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2011, 31, 452–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, M.; Roehrich, J.K.; Eßig, M.; Harland, C. Driving Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Public Sector: The Importance of Public Procurement in the European Union. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 19, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, L. Addressing Sustainable Development through Public Procurement: The Case of Local Government. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 14, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.; Marklund, P.O.; Strömbäck, E. Is Environmental Policy by Public Procurement Effective? J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2015, 71, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, C.; Hallstedt, S.; Robèrt, K.H.; Broman, G.; Oldmark, J. Assessment of Criteria Development for Public Procurement from a Strategic Sustainability Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appolloni, A.; Sun, H.; Jia, F.; Li, X. Green Procurement in the Public Sector: A State of the Art Review. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2014, 20, 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Public Procurement Monitoring Office (PPMO). Annual Procurement Report 2023. Government of Nepal, Kathmandu, 2023.

- Shakya, R.K. Public Procurement in Nepal: Issues and Challenges. Public Procure. J. Nepal 2016, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, W. , 1977. Sampling Techniques. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Fowler, F. , 2014. Survey Research Method. 5th ed. University of Massachusetts: Centre for Survey Research.

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooshdi, R. R. R. M., Majid, M. Z. A., Sahamir, S. R. & Ismail, N. A. A., 2018. Relative Importance Index of Sustainable Design and Construction Activities Criteria for Green Highway. Chemical Engineering Transactions, Volume 63, pp. 151–156.

- World Bank, 2021. Green Public Procurement: An Overview of Green Reforms in Country Procurement Systems, Washington: Climate Governance Papers Series.

Table 1.

Overall RII Ranking of Drivers.

Table 1.

Overall RII Ranking of Drivers.

| Category |

Overall RII |

Rank |

Importance |

| Organizational Driver |

0.758108 |

5 |

H-M |

| Market Drivers |

0.764189 |

3 |

H-M |

| Legal Drivers |

0.772072 |

1 |

H-M |

| Environmental Drivers |

0.766667 |

2 |

H-M |

| Technical Drivers |

0.722973 |

6 |

H-M |

| Economic/Financial Drivers |

0.758378 |

4 |

H-M |

Table 2.

Ranking Table of Drivers of GPP Implementation.

Table 2.

Ranking Table of Drivers of GPP Implementation.

| Driver Category |

Driver |

RII |

Rank |

| Organizational Drivers |

Sustainability Commitment |

0.75946 |

11 |

| Government Initiatives |

0.75405 |

13 |

| Public Sector Reforms |

0.74594 |

15 |

| Institutional Support |

0.77297 |

6 |

| Market Drivers |

Growth of Green Products and Services |

0.75405 |

13 |

| Private Sector Involvement |

0.76216 |

9 |

| International Trade |

0.72973 |

20 |

| Renewable Energy Growth |

0.81081 |

1 |

| Legal Drivers |

Environmental Regulations |

0.76216 |

9 |

| International Treaties |

0.76486 |

7 |

| Focus on Sustainable Development |

0.78919 |

2 |

| Environmental Drivers |

Climate Change Vulnerability |

0.74594 |

15 |

| Disaster Risk Management |

0.76486 |

7 |

| Forestry and Biodiversity Conservation |

0.78919 |

2 |

| Technical Drivers |

Technical Know-How from INGOs |

0.70000 |

21 |

| Digitalization of Procurement |

0.74594 |

15 |

| Economic/ Financial Drivers |

Cost Saving |

0.73784 |

19 |

| Economic Growth |

0.74594 |

15 |

| Life-Cycle Cost Analysis |

0.77568 |

4 |

| Private Sector Competitiveness |

0.75676 |

12 |

| Financial Incentives |

0.77568 |

4 |

Table 3.

Overall RII Ranking of Drivers.

Table 3.

Overall RII Ranking of Drivers.

| Category |

RII |

Rank |

Importance |

| Organizational Barriers |

0.778919 |

1 |

H-M |

| Market Barriers |

0.754054 |

4 |

H-M |

| Legal Barriers |

0.776577 |

2 |

H-M |

| Technical Barriers |

0.776351 |

3 |

H-M |

| Economic/Financial Barriers |

0.751351 |

5 |

H-M |

Table 4.

Ranking Table of Drivers of GPP Implementation.

Table 4.

Ranking Table of Drivers of GPP Implementation.

| Driver Category |

Barriers |

RII |

Rank |

| Organizational Drivers |

Complexity and Bureaucracy |

0.75675 |

14 |

| Lack of Knowledge and Awareness of GPP |

0.78919 |

4 |

| No Internal GPP Policies |

0.80000 |

2 |

| Resistance to GPP Adoption |

0.73784 |

21 |

| Limited GPP Training Programs |

0.81081 |

1 |

| Market Drivers |

Scarcity of Green Products |

0.70000 |

22 |

| Lack of Market Information |

0.77027 |

10 |

| Lack of Green Product Suppliers |

0.77568 |

8 |

| Market Uncertainties |

0.77568 |

8 |

| No Competitive Green Options |

0.74865 |

18 |

| Legal Drivers |

Compliance Burden |

0.75405 |

16 |

| Regulatory Constraints |

0.77838 |

7 |

| Lack of Legal Framework |

0.79730 |

3 |

| Technical Drivers |

Lack of Technical Expertise |

0.77027 |

10 |

| Inadequate Standards |

0.78919 |

4 |

| Technological Gap Hinders GPP |

0.78108 |

6 |

| Technological Uncertainties |

0.76486 |

12 |

| Economic/ Financial Drivers |

High Initial Costs of GPP |

0.74595 |

19 |

| No Financial Incentives for GPP |

0.75135 |

17 |

| Budget Constraints Limit GPP |

0.75676 |

14 |

| Limited Budget |

0.76216 |

13 |

| Perceived Financial Risks |

0.74054 |

20 |

Table 5.

Specific Actions, Timeframes, and Responsible Government Bodies.

Table 5.

Specific Actions, Timeframes, and Responsible Government Bodies.

| Action |

Timeframe |

Responsible Government Body |

Government Level |

| Short-Term (1-3 Years): Foundation and Initial Implementation |

| Establish a Task Force on GPP |

1-3 years |

Department of Expenditure, Ministry of Finance, National Planning Commission (NPC) |

Federal |

| Review and Amend Legal Framework |

1-3 years |

Ministry of Law, Justice, and Parliamentary Affairs, the NPC, Ministry of Finance |

Federal |

| Conduct Stakeholder Mapping and Consultations |

1-3 years |

GPP Task Force |

Federal, Provincial, Local |

| Develop an GPP Policy Statement |

1-3 years |

GPP Task Force, Ministry of Finance, NPC |

Federal |

| Baseline Assessment of Current Procurement Practices |

1-3 years |

GPP Task Force |

Federal, Provincial, Local |

| Develop a GPP Communication Strategy |

1-3 years |

GPP Task Force, Ministry of Information and Communication |

Federal |

| Prioritize Product and Service Categories |

1-3 years |

GPP Task Force, Ministry of Industry, Commerce, and Supplies (MoICS), Ministry of Forests and Environment (MoFE) |

Federal |

| Medium-Term (3-7 Years): Expansion and Integration |

| Develop Environmental Criteria |

3-7 years |

MoFE, MoICS, GPP Task Force |

Federal |

| Promote Ecolabels and Standards |

3-7 years |

MoFE, MoICS, Nepal Bureau of Standards and Metrology, GPP Task Force |

Federal |

| Implement Life-Cycle Costing |

3-7 years |

GPP Task Force, Ministry of Finance |

Federal, Provincial, Local |

| Conduct Pilot GPP Projects |

3-7 years |

GPP Task Force, Relevant Ministries |

Federal, Provincial |

| Quantify Benefits of GPP |

3-7 years |

GPP Task Force, Ministry of Finance, National Planning Commission |

Federal |

| Develop GPP Guidelines and Tools |

3-7 years |

GPP Task Force, Ministry of Finance, Nepal Administrative Staff College, Ministry of Supplies |

Federal |

| Develop Capacity Building Programs |

3-7 years |

GPP Task Force, Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration |

Federal |

| Develop a GPP Monitoring System |

3-7 years |

GPP Task Force, NPC, Ministry of Finance |

Federal |

| Long-Term (7+ Years): Sustainability and Refinement |

| Streamline Procurement Processes |

7+ years |

GPP Task Force, Public Procurement Monitoring Office (PPMO) |

Federal, Provincial, Local |

| Develop Supplier Facilitation Programs |

7+ years |

GPP Task Force, MoICS |

Federal |

| Promote Performance-Based Contracts |

7+ years |

PPMO, GPP Task Force |

Federal |

| Enhance collaboration |

7+ years |

All relevant Ministries, Federal, Provincial, Local Governments |

All Levels |

| Institutionalize GPP |

7+ years |

PPMO, All Ministries |

All Levels |

| Ensure Policy Alignment |

7+ years |

NPC, All Ministries |

All Levels |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).