1. Introduction

Over the past 50 years synthetic polymers and their usage, applications and presence in industry have grown exponentially. The plastic industry is still seeing rapid growth and it is estimated that plastic production will exceed 600mt (Million Tons) in the next 10 years [

1]. This rapid growth can be credited to polymer materials’ excellent versatility in terms of properties and characteristics [

2] which allow for a broad range of applications in food, medical and manufacturing settings. Synthetic polymers provide an almost limitless range of properties that can be tailored to fit general purpose applications as seen with plastic bags, containers and utensils to extremely niche applications in drug delivery and medical devices [

3,

4].

Polymers exhibit these desirable characteristics because of their polymeric structure, long chains of repeating units called monomers are covalently bonded and can consist of several different arrangements. These are generally accepted to be “linear” “branched” “cross-linked” and “networked” [

5] with each arrangement becoming more complex and harder to separate. Each different arrangement contributes to the characterization of these materials and crucially, their ability to be reused and recycled [

6]. While the versatility these molecular structures provide is advantageous, it has also become a critical environmental issue, particularly in recent years [

7]. The synthetic nature of these elements provides them with excellent properties such as being hydrophobic and inert which are desirable for many applications in industry, however, it also creates materials that are inherently non-degradable by environmental factors and enzymatic degradation through microbial action [

8].

The inability of these materials to degrade naturally and consistent mismanagement of plastic waste has led to significant negative environmental impacts. Plastic pollution is a global crisis with only 7% of plastic waste actually being recycled annual and over 50% ending up in landfills [

9]. Annual plastic waste production is forecast by the OECTD to rapidly increase to over 1000mt by 2060 [

10]. While countries around the world struggle to develop effective waste management systems, increased pressure has been put on companies to employ greener processing methods and materials to help alleviate the issue of plastic pollution and bolster long term and environmentally sustainable practices. This has resulted in a push for sustainable and biodegradable materials, particularly in the food and medical industries which will see the global production capacity of bioplastics rise from 2.18mt in 2023 to a predicted 7.4mt in 2028 [

11].

The increased demand for sustainable materials has led to the development and implementation of a range of biomaterials with PLA seeing the most widespread use because of its notable mechanical properties and relatively cheap production costs when compared to other biomaterials [

12,

13]. Biomaterials consist of organic compounds and are easily degraded in the presence of water through hydrolysis or enzymes specific to the material such as cellulase for cellulose and amylase for starches [

14]. The relative abundance of organic materials for use in biopolymers has enhanced their market viability with extensive preliminary available data on proteins, polysaccharides, starches and polyphenols and their applications in food and medical settings [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Biopolymers provide an extensive range of benefits when compared to traditional synthetic polymers, data has shown that the use of organic compounds in packaging films has proven physiological benefits and antimicrobial properties [

19]. These materials have also become significant in the medical industry as packaging, medical devices and more recently as drug delivery excipients providing safe and non-toxic by-products when they degrade within the body [

20].

The push for sustainable materials has however, been fraught with challenges. Biomaterials are produced through entirely separate mechanisms to conventional synthetic polymers. Materials such as PLA and PHB are created through bacterial fermentation as opposed to petrochemical processing, this has resulted in notable material costs which can exceed 50% of the cost of production in some cases [

21]. The consistency of the term “biodegradable” has also been heavily scrutinized in recent years. This has come from a broad range of biomaterials, including PLA’s inability to degrade unless under specific circumstances, which are typically uncommon in nature [

22]. As a result, this has led to apprehension about these materials’ introduction to the market. Recent developments into marine polysaccharides have addressed some common issues faced by traditional biomaterials. Seaweed based polysaccharides are extremely abundant materials and are considered third generation feedstocks requiring no land to cultivate and growing at rates up to ten times faster than terrestrial materials [

23]. Algal polysaccharides have become a popular choice for biodegradable packaging [

24], drug delivery excipients [

25], and medical devices [

26] because of their excellent biocompatibility and physiological benefits [

27].

While the outlook for biomaterials is still extremely positive because of their sustainability, physiological benefits and biocompatibility, there are still significant barriers to entry to the commercial market as food packaging and medical devices. The most significant issue with biomaterials is their poor material performance when compared to traditional synthetics [

28]. The mechanical performance and barrier properties of biomaterials have been a consistent hindrance to these materials’ commercialisation and are often further reduced due to sterilization processes related to stringent regulatory measures for food packaging and medical applications.

Sterilization is not essential for all food packaging but is often a prerequisite for packaging of sterile food, some ready to eat products and high-risk products such as baby formula and is carried out on all medical devices, packaging and drugs. It is the process of removing all microbial life and endospores from the surface and penetrating a material. Sterilization is an important process that ensures that food packaging, medical devices, drugs and excipients are free from harmful bacteria and spores that could cause potential outbreaks or cause serious harm to members of the population considered high risk or vulnerable.

Methods of sterilization include dry and wet heat, irradiation, chemicals, solvents and gas and selecting a method of sterilization for a given material is dependent on material characteristics such as thermal, UV and moisture resistance. Sterilization, while often a requirement for use in food packaging and medical application, has been known to degrade the materials being sterilized and, in many cases, cause notable reduction in mechanical and optical properties through discoloration, degradation by chemical or heat and crosslinking and chain scission through free radical interactions caused by irradiation processes [

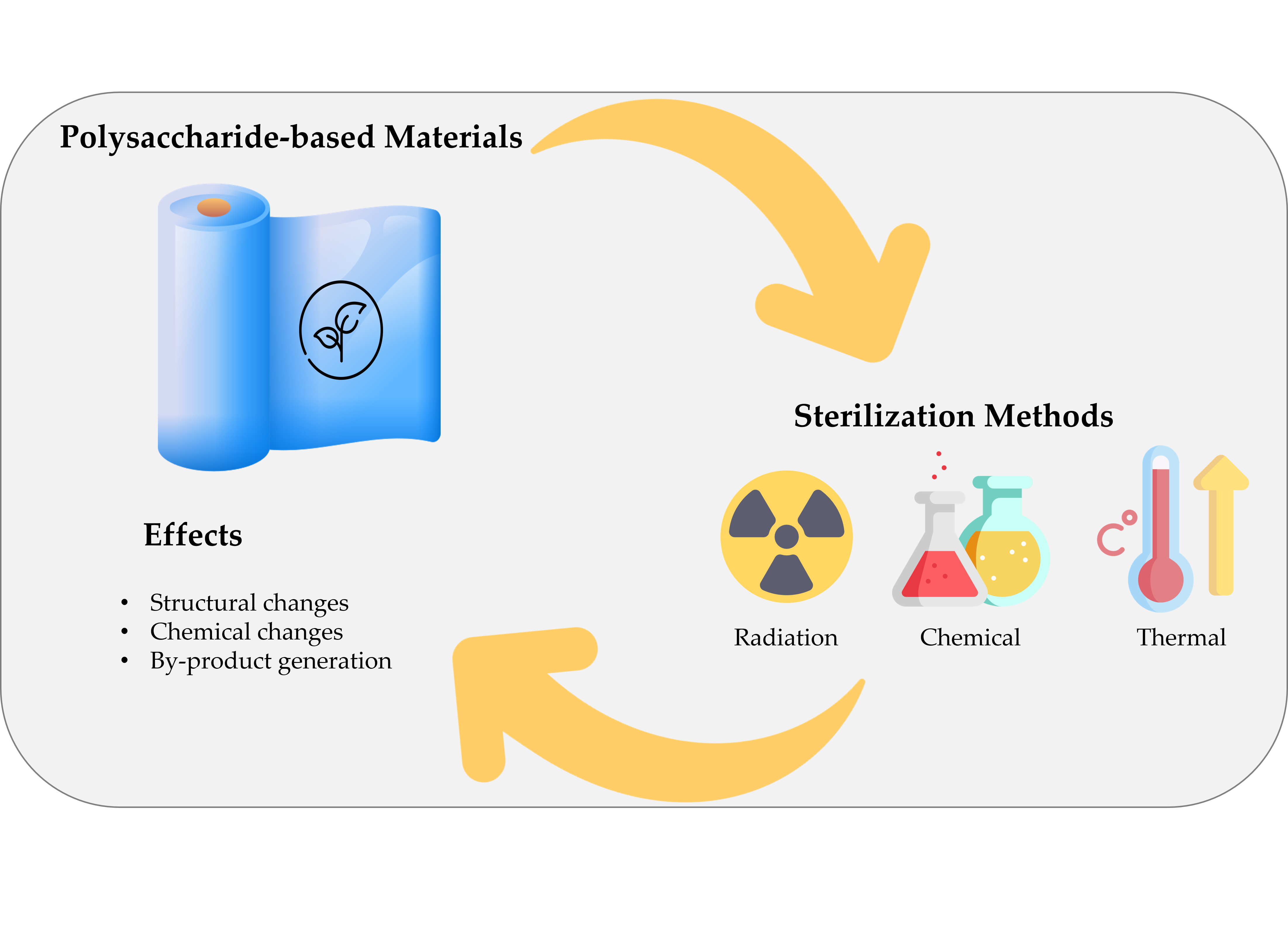

29]. This review focuses on the studied effects that a range of sterilization techniques have had on conventional polysaccharides and how these effects can impact the physiochemical and migratory properties of common polysaccharides and their market viability thereafter.

2. Sterilization Methods and Molecular Effects

2.1. Ionising Radiation

Many methods of sterilisation employ a combination of temperature, pressure, humidity and chemical treatments. To keep chemical and physical interactions to a minimum, particularly in complex and sensisitive medical devices, ionising radiation is commonly used. The benefit of radiation methods are that they are non-invasive and highly effective sterilising agents, however, the formation of free radicals and the potential for radiolysis at higher dosages can led to unwanted changes in material properties and leaching from device to bloodstream. While these methods produce no byproducts they can still alter the material through cross-linking and chain scission as well as requiring specialised training, particularly in the case of gamma radiation which uses a live radioactive element to sterilise materials.

2.2. Electron Beam

Electron (E) beam sterilization has become a popular method of sterilization for a range of materials due to its non-invasive nature. Materials that are susceptible to thermal degradation at elevated temperatures or undesirable interactions with chemicals and solvents are typically sterilized by means of radiation. The use of e-beam sterilization has been beneficial, particularly in the field of medicine for its excellent material penetration at higher voltages, allowing it to effectively sterilize complex and sensitive devices at high speed and no physical interaction. E-beam sterilization has also found success in the packaging industry because of this property and the added benefit of being able to produce ionizing radiation with no radioactive elements [

30].

The system of irradiation used for E-beam is an electron accelerator. Electric fields are generated in the accelerator wherein electromagnetic (micro)waves are used to accelerate electrons emitted thermionically to ~99.6% of the speed of light. The beam can be focused using lenses or small plates to direct the electrons and effectively sterilize the target product. E-beam and other irradiation techniques are some of the most effective sterilizing methods because of ionizing radiations effects on microbial life and endospores. Electrons which encounter organisms cleave the backbone structure of DNA which destroys all potential contaminants [

31]. These systems are typically energy intensive ranging from 1 MeV (Mega electron Volt) to 10MeV for denser materials. The penetrative effects of E-beam sterilization increase with increasing MeV, however, regulations such as ISO I11137-1:2006 generally require materials to be further evaluated for induced radioactivity over 10MeV [

32].

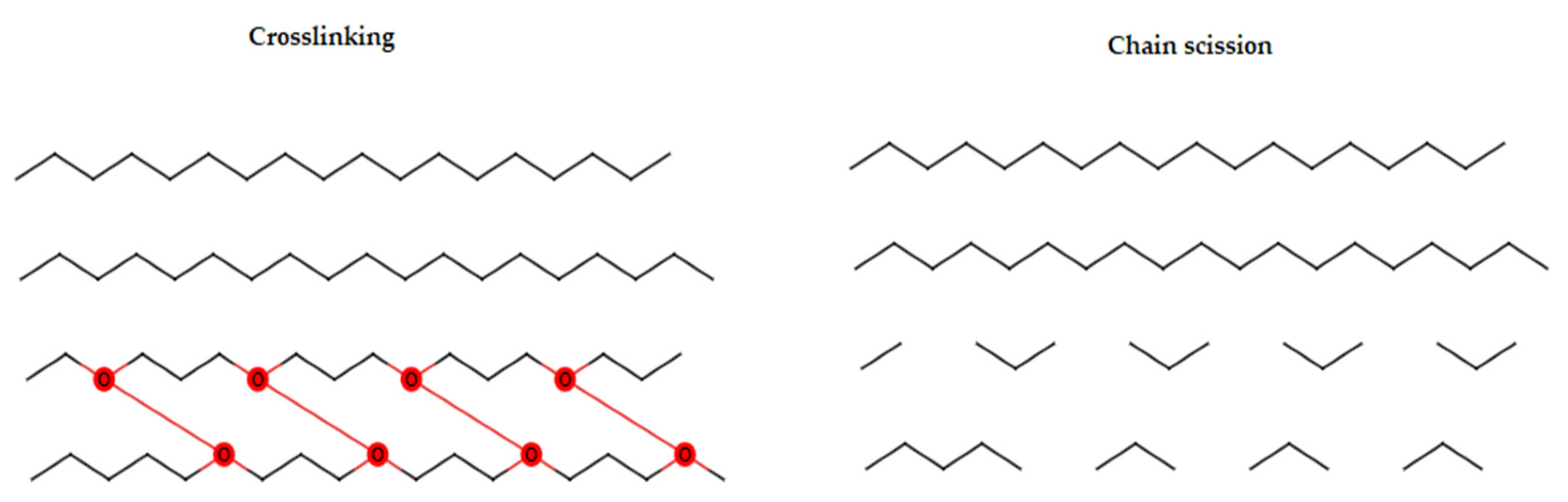

While the ionizing effects of e-beam radiation are a considerable advantage for sterilizing materials, this same property can induce unwanted negative side-effects which directly impact material performance. Biopolymers have often been criticized for their poor material performance when compared to traditional synthetics and the process of irradiation is known to cause the formation of free radicals in polymeric materials, which can cause chain scission or crosslinking as seen in

Figure 1 [

33]. The data relating to the sterilization of biopolymers through e-beam is extensive when compared to other sterilization techniques.

2.3. Gamma Radiation

Like E-beam sterilization, gamma produces ionizing radiation which effectively removes all endospores and microbial life from the surface and within devices and materials. While the phenomena of crosslinking and scission are persistent through each irradiation method the process has several distinct differences that separate it from other forms of radiation treatment, including its emission of radioactive elements. This is due to the difference in ionizing particles in each method. E-beam radiation uses high or low energy electrons to sterilize materials whereas gamma radiation uses photons (gamma rays) produced from the radioactive decay of cobalt-60 (60CO) that can penetrate much deeper into the material being sterilized [

45]. Gamma sterilization is an inherently more dangerous and time-consuming process because of the radioactivity, slow rate of decay of cobalt-60 and greater penetrating abilities of photons. Due to their limited interactions with outer shell electrons resulting from their neutral charge photons can travel deeper into irradiated materials [

46]. As such, when compared to other forms of sterilization gamma radiation requires a setup that is often subject to more stringent requirements including the necessity of thick radiation shielding. Gamma radiation has become a preferred method of sterilization as it allows large batch processing of in-package devices and materials. The diffuse nature of photons means they do not need to be directed or reflected to effectively target the object for sterilization [

47]. Having excellent penetrability, it can sterilize complex and dense medical devices without causing chemical or heat degradation.

2.4. X-Ray

X-ray sterilization is a less conventional method of sterilization that has seen some use in recent times due to its superior ability to penetrate materials when compared to gamma and e-beam methods. X-ray, while it is a much more costly and complex process, offers distinct advantages over gamma sterilization with the ability to sterilize denser and more complex devices at a much faster rate. The principle of sterilization remains the same with x-ray sterilization, ionizing radiation penetrates the molecular structure of microbial life and endospores present on the material, damaging the DNA and effectively sterilizing the material [

30]. X-ray sterilization is carried out using many of the same principals of e-beam sterilization. Electrons are thermionically released from a cathode inside an electron gun where they are sped up to 99% of the speed of light using an electric field. Instead of being fired directly at the materials as seen in e-beam these electrons are directed at an anode which commonly consists of tungsten. The sudden arrest of velocity causes a phenomena known as “Bremsstrahlung” which leads to the emission of x-rays [

31]. illustrates the ionizing electrons produced from this process which can interact with the two outermost shells of the anodes’ molecules creating photons as a result [

32].

2.5. Ultraviolet Radiation

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is a less common form of sterilization that also sterilizes by photochemical processes. Typical UV rays, as shown in Figure 2.3, are considered non-ionizing and are categorized as “UVA and UVB”. In a sterilization environment UVC rays are used which are shorter wavelength rays composed of photons that interact with electrons in the outer orbit of irradiated molecules to alter their structure and cause irreversible damage in the case of DNA in living organisms [

33]. The most common apparatus used for UVC sterilization are lamps or rods which can effectively sterilize surfaces and thin devices. The penetrating power of UV rays are much lower than those seen in other radiation methods. This is likely the primary reason for the lack of data relating to the sterilization of biomaterials used in complex medical devices and dense packaging [

34].

2.6. Ethylene Oxide

Ethylene oxide (EtO) is one of the most common methods of sterilization, particularly for medical devices. This stems from the gasses ability to penetrate difficult to reach areas in medical devices and the process using no heat or humidity to effectively sterilize products. EtO is a well-established and extremely well controlled sterilization process that enables the sterilization of sensitive medical devices without the danger of heat or radiation-based degradation [

128]. EtO is a direct-acting alkylating agent, not requiring metabolic activation, acting antimicrobilally via inactivation of DNA, RNA and proteins found within bacteria, viruses, fungi and spores [

35,

36,

37]. The addition of alkyl groups which are bound to the sulfhydryl, hydroxyl, amino and carboxyl groups prevent regular cellular activity and the ability to reproduce, thus rendering microbes nonviable [

37]. Although EtO sterilization is a carefully controlled process there is an innate danger stemming from the reactive nature of the substance itself. EtO is an effective sterilizing agent due to its reactivity with DNA pairs. This reactive nature of EtO is a result of its strained epoxide structure [

129] which when in contact with DNA pairs will covalently bond causing alkylation which disrupts cell functions. These characteristics also make EtO extremely toxic to human life, it is considered a mutagen and carcinogen and requires strict regulatory controls in industry [

130] The process of EtO sterilization is typically carried out in a vacuum chamber over four distinct phases, vacuum, exposure, sterilizing, and aerating. Once a vacuum has been created the chambers humidity and temperature are stabilized so that the material can be exposed to the gas. The process of exposure, sterilizing and aerating can take up to 60 hours making EtO the most time intensive sterilization process. EtO is one of the most widely used processes for materials that have low thermal resistance or are susceptible to water-based degradation, as such, the established data should be extensive when compared to many other discussed methods.

2.7. Autoclaving

Autoclaving is a common form of sterilization it uses a relatively simple method of pressurized steam to kill bacteria and fungal spores through denaturation of proteins, inactivation of DNA and cell membrane damage. Typical autoclaving is carried out at 115°C for 20 minutes. Autoclaving is considered a sterilization method with low penetrability, because of this the items that are most compatible with autoclave sterilization are glassware, pipettes, cultures, bags and liquids [

102]. Autoclaving is considered an extremely safe method of sterilization with little to no risk of contamination in the sterilized material or danger to the operators. The process uses a chamber where the airflow can be regulated and removed to create a vacuum. After air is removed the chamber is filled with steam causing the pressure and temperature to increase to a baseline level where sterilization will take place. The simplicity of autoclaving makes it a preferable option for lab equipment and can sterilize large batches per cycle [

103].

Within industry the use of autoclaving for biopolymer sterilization is negligible. This incompatibility stems from the low C-C bond strength in molecular structures of biopolymers [

104] and the heat and humidity produced via autoclaving. Biopolymers are considered biodegradable and biocompatible largely because of hydrolysis which is the cleavage and degradation of the backbone structure when in contact with water. The occurrence of this phenomenon significantly increases the risk of degradation in the material in a process such as autoclaving and has resulted in an expected lack of data.

2.8. Dry Heat

Dry heat is another relatively simple method of sterilization. Dry heat methods use convective heat transfer to circulate hot air in a chamber which sterilizes the target material. Air temperature ranges from 105°C – 190°C with typical cycle times of 180 minutes to 11 minutes respectively. This method of sterilization is desirable for materials that may be susceptible to degradation in the presence of water and/or humidity. The penetrative ability provided by dry heat is also beneficial for products of complex geometry provided that airflow is permitted over its surface [

114]. Dry heat has the potential to inactivate all microbes including pyrogens, however it is less effective against prions than that of moist heat. Primarily, the microbial inactivation occurs as a result of protein denaturation, dehydration and oxidative free radical damage [

38,

39,

40]

In the context of biopolymers dry heat is relatively a relatively uncommon process. Unlike autoclaving that will induce hydrolytic reaction, dry heat induces more significant heat degradation in materials. The higher operating temperatures and exposure times found in dry heat sterilization heavily impact its viability in the biopolymer industry.

2.9. Ozone

Ozone has seen some use as a sterilizing agent in industry. Ozone effectiveness comes from a process known as “oxidative bursts” which perforates the cell wall of microorganisms and disrupts cell activity. This is due to the reactive nature of Ozone (03) where it will always freely give up an oxygen atom. As cell proliferation occurs more ozone atom enters the cell membrane and reacts internally to further eliminate microbial elements leaving only oxygen as a by-product. Ozone has some distinct advantages including its ability to penetrate and sterilize complex geometries and heat sensitive materials [

41]. While ozone boasts some advantages, it is still a relatively new process with some pertinent issues. Ozone has been shown adverse effects when exposed to human respiratory systems with long term exposure suspected to be fatal [

42]. In regards to the literature relating to ozone sterilization the process may be unsuitable for a large number of polymers due to materials ability to adsorb ozone causing unwanted chemical or structural degradation [

43].

2.10. Supercritical Carbon Dioxide

Supercritical Carbon Dioxide (ScCO2) is a promising alternative to many forms of sterilization that induce degradation in the base materials. The inert nature of carbon dioxide and its low surface tension allow it to penetrate deep into materials and completely sterilize objects with complex geometry without the risk of chemical reaction and toxic residues [

44]. CO2 reaches its critical state at a low temperature of ~30°C and pressure of ~38MPa which is well within the acceptable range for even the most sensitive biopolymers. The supercritical nature of the carbon dioxide allows it to possess the penetrative properties of a gas while maintaining the dissolution properties of its liquid form which gives it excellent biocidal properties [

45]. The mechanism of sterilization for ScCO2 involves the denaturation of proteins through the formation of carbonic acid from chemical reactions with H2O within the cell wall [

46]. ScCO2 has also been observed to extract lipids from the cell membranes which maintain cell function [

47].

Similar to other gas-based processes ScCO2 is carried out in a vacuum chamber where pressure and temperature a controlled to the supercritical point of the gas. Unlike ETO sterilization, no toxic residue is present after the initial sterilization phase making long aeration phases unnecessary meaning ScCO2 is a considerably faster process. While the biocidal effects of ScCO2 are considered extremely effective the nature or mechanism of sterilization by carbon dioxide leaves it ineffective against some forms of spores and endospore. Eliminating microbes primarily through dissolution and reaction with H2O is an effective method for bacterial strains consisting of high-water content. Spores generally consist of a highly dehydrated core with a low permeability outer spore cortex which makes carbon dioxide an ineffective sterilizing agent [

48]. The effectiveness of ScCO2 against spores has been enhanced through the use of additives and slight increases in operation temperatures, however, many of these developments fail to produce a 9-log (99.99%) reduction in spores in the material [

49,

50].

3. Sterilization of Polysaccharide-Based Materials

Polysaccharide’s ability to produce biodegradable and biocompatible materials has seen their usage in the food and medical device industry increase dramatically in recent years. The growing fears related to microplastic toxicity and the long-standing issue with plastic waste have resulted in the promotion of sustainable, circular and, most importantly, a biocompatible approach to new products. While these new products are rigorously tested to fall in line with ISO’s and product regulations the necessity of sterilization, in the medical industry, can modify the material properties to an undesirable state. The data relating to the sterilization of polysaccharide materials is crucial to understanding the changes in material properties and how these may impact the medical device or food packaging performance.

3.1. Electron Beam

Wei Liang et al. performed detailed characterizations of potato starch using EBI (electron beam irradiation), where they found that the process of EBI induced significant changes in the isolated starch samples. The samples experienced degradation, yellowing and reductions in molecular weight while still retaining its original morphological properties [

51]. A similar study by Xing Zhou et al., investigated the effects of EB on waxy maize starch films where the results were consistent with established data. They found reductions in MW, a notable reduction in tensile properties at higher dosages and an increase in short chain production which significantly increased the solubility, it was also found to have increased modulus properties at lower dosages due to increased relative crystallinity from cross linking [

52].

Common reinforcing materials such as cellulose lack persistent data with studies referring primarily to pulp degradation and effects as part of an organic-non-organic mix or composite. Driscoll et al. investigated the effects EBI that had doses varying from 0-1000kGy with values in excess of 50-100kGy being far above a common dosage [

53], these results did however emphasize the degrading effects of EBI dosages with a reduction in MW of 2%, 93% and a 97% reduction at 10kGy, 100kGy and 1000kGy respectively. The relative crystallinity of the cellulose reduced from 87% to 45% at 1000kGy [

54]

Data for non-terrestrial polysaccharides are sparse with alginate, agar and chitosan being the most characterized through means of EBI. Yuan et al. characterised Carboxymethyl Chitosan hydrogels where it was found that although the irradiation inhibited the materials ability to flow and caused greater degrees of yellowing at each dose there were no significant alterations to the group structure and molecular weight of the chitosan material post irradiation [

55]. While these results are promising a paper by Urszula Gryczka investigated and emphasized the necessity of long-term analysis of chitosan undergoing ionizing radiation. It was found to cause elevated degrees of deacetylation and oxidative degradation, dependent on dosage, over a five year period [

56]. Data for agar is extremely limited with minor references made to sterilization through EBI, however a singular study by Luliano et al. completed a range of sterilization techniques including EBI on TPS (Thermoplastic starch) agar-agar blends. Results were consistent with established literature, with the material becoming more rigid and had an observable increase in WVP (water vapor permeability) of 10% and 14% [

57].

Apart from starches, alginates appear to have the most extensive range of data available although it is still exceptionally limited and primarily for medical applications, Puspitasari et al.l studied the degradation of a high and low viscosity sodium alginate by low energy electron beam where colour change and reductions in molecular weight were observed and it was concluded that for LEEB applications Low viscosity alginates were preferrable. Research by Farno et al. studied LEEB irradiation of 3D scaffolds of alginate/chitosan and their polyelectrolyte complexes. Depolymerisation was observed at dosages of 25kGy with reductions in molecular weight and overall material cohesion. The results also found an optimal dose of 280keV to sustain sterility and maintain scaffold properties [

58].

3.2. Gamma

Polysaccharides have a variable range of data relating to gamma radiation as their use in medical and packaging applications has seen sharp increases in recent years, while terrestrial polysaccharides have been well characterised, non-terrestrial or marine polysaccharides remain largely unexplored. Starch is one of the most common polysaccharides that is employed in the biopolymer industry and radiation studies have been carried out a range of starches from varying sources. Chung et al. studied the effects of gamma radiation on corn starches with different ratios of amylose to amylopectin. The study found increased IR absorbance at each dosage (1,5,10,25,50kGy) as well as significant reductions in the pasting abilities and crystallinity of the starch materials. While the degrading effects were significant for a range of starches tested, one specimen, Hylon VII exhibited significant resistance to gamma radiation at 5kGy and showed signs of increased viscosity at this range [

59].

A study by Atrous et al. characterised the effects of gamma radiation on starch/clay composites at 1-4%wt. The study observed that the tensile strength and gelling fraction of starch blends would steadily increase from dosages of 10kGy, 20kGy and 30kGy but sharply declined by ≥50% at 40kGy for all samples. The elongation at break of each sample steadily declined in all cases while the increase in clay content enhanced the thermal stability of the material [

60]. Similar results found by Atrous et al. showed high doses of gamma irradiations >20kGy induced significant deterioration of starch cellular structure and swelling power. The study also found that apparent amylose content in wheat samples were higher than potato samples at each dosage which align with results from Chung et al. which posits that higher sources of amylopectin will reduce degradation via gamma irradiation [

61].

Marine polysaccharides have seen little characterization in terms of gamma sterilization with chitosan and alginate having the most established data while carrageenan fucoidan and agar have extremely sparse data pertaining to sterilization. While sterilization through gamma radiation is not readily available for carrageenan some effects of ionizing radiation have been catalogued by V. Abad in a review of radiation modified carrageenan. The effects of gamma radiation induce chain scission and thus reduces the molecular weight of the material. This reductions in molecular weight has been linked an increase in reducing sugars which have anti-oxidant effects [

62]. Similarly, fucoidan has seen little characterization in terms of gamma radiation, however, a study by Choi et al. investigated the effects it had on the structure of fucoidan itself. The study observed the formation of additional carboxyl groups in the material through gamma irradiation and also concluded that the radiation up to dosage of 100kGy had no significant effect on the sulfate functional groups of the material [

63]. A similar study carried out by Jong-il Choi and Hyun-Joo Kim used gamma radiation to prepare fucoidan at dosages of 30, 50 and 100kGy. The study showed a sharp initial decrease in molecular weight that normalized over time. The study also investigated the anti-cancer properties of fucoidan and found that at dosages of 100kGy the cytotoxicity significantly increased to 47% from 35% in non-irradiated specimens [

64].

Alginates have seen considerably more analysis compared to other marine polysaccharides likely due to their broad usage in the medical field. A study by Lee et al. investigated the effects of gamma radiation degradation sodium alginate. They found that over the range of 0.1kGy to 200kGy the rate of degradation increased exponentially but sharply declined/ceased at dosages higher than 200kGy. The viscosity of the alginate was also significantly reduced at dosages as low as 10kGy and the materials exhibited a colour to change to brown as the dosage increased [

65]. Huq et al. studied the effects of gamma radiation on alginate films and beads. They found that minor dosages in the range of 0.1-0.5kGy resulted in an increase in mechanical properties and gelling power in the films and beads. The study also observed that dosages of 5kGy and above completely removed the film forming capabilities of the alginate material.

Like alginate, the data for chitosan in recent years are well established when compared to other polysaccharides. Jarry et al. investigated the effects of gamma irradiation on chitosan/polyol where they found that the viscosity of chitosan was significantly reduced which severely inhibited the thermogelling properties of the mixture. Another study by Lim et al. characterised the mechanical, thermal and molecular properties of chitosan films at dosages of 3.7,11,18.3 and 25kGy. The study showed considerable increase in mechanical performance at 3.7kGy with a notable increase in tensile strength of 60%. The mechanical properties continued to increase until dosages of 25kGy. The material also showed a steady decrease in molecular weight as expected from chain scission attributed to ionizing radiation with reductions in viscosity also observed [

66]. Further studies on chitosan films were conducted by Li et al. The study focused on konjac glucomannan/chitosan films and characterised the mechanical and structural properties of the films. IR spectra showed increased absorbance at each dose with little interaction/cleavage observed at dosages of 25kGy. The results showed that from dosages of 0kGy-80kGy showed negligible impacts on mechanical performance however the maxim increase in crystallization occurred at dosages of 25kGy. The results of the study suggest that konjac glucomannan can inhibit the degradation of chitosan by gamma radiation [

67].

3.3. X-Ray

Data relating to x-ray sterilization on biomaterials are extremely sparse, this is likely due to the complexity of operation and large costs involved with this process. While the data are few there are still several studies that have worked to catalogue the effects of x-ray radiation on a range of starches, wool keratin, collagen and alginate. Kerf et al. characterised corn, potato and drum dried corn starches and their disintegration properties as a result of x-ray treatment. The disintegration rates of tablets containing α-lactose monohydrate, magnesium stearate and corn, potato or ddc irradiated starches at dosages of 0, 10, 50 and 100kGy were examined. The tablets showed decreased disintegration time per increased radiation dosage. The solubility of each sample also notably increased with increasing dosages with the solubility of corn starch increasing from 24% at 0 kGy to 75% at 100 kGy [

68]. Another study by Leccia et al. investigated the effects of a high flux x-ray synchrotron micro beam on alpha keratin fibers. The study observed disulphide bond cleavage as well as mass loss associated with chain scission.

3.4. Ultra-Violet

Various sources of starches have been characterised through UV-radiation in studies by Bajer et al. The study observed that out of the tested starches from corn, waxy corn, potato and wheat, potato starch was the most vulnerable to UV radiation. UV radiation induced chain scission in each of the samples except for potato starch due to its higher water content and lower crystallinity [

69]. Kurdziel et al. also investigated the effects of UVB radiation on potato and corn starch and amylopectin. The results showed that potato starches exhibited much more degradation than corn starches and amylopectin samples [

70]. This result is consistent with previously discussed amylopectin resistance to degradation by radiation via gamma rays which suggests that, based on available data, amylopectin is effective in reducing the degrading effects of radiation in materials. A study on wheat and spelt starches by Nowak et al. investigated the physiochemical and molecular properties after UV radiation. They found that the molecular weight of the irradiated spelt starches fluctuated through different periods of exposure with an initial decrease followed by an increase in Mw post 5 hours of radiation. The study observed that the highest molecular weight chains appeared after 50 hours of radiation which suggests that UV radiation can be used to alter the modifiable properties of the starches for further applications [

71].

The data for marine polysaccharides are not as extensively available though some evaluation is possible. Sedayu et al. investigated the effects of surface crosslinking on carrageenan film using sodium benzoate as a crosslinking agent. The results of the study showed a 35%-55% increase in tensile strength and 144% increase in modulus with 52% reduction in elongation at break. The study also observed a decrease in water transmission (WVP) of 21% but increased solubility and water uptake of 23%/22% [

72]. The effects of photo crosslinking are positive, but the necessity of a crosslinking agent here suggests as certain resistance to UV in the carrageenan alone. A study by Prasetyaningrum et al. studied the effects that UV/O

3 had on k-carrageenan. They observed that UV radiation or O

3 alone did not significantly alter the material except for minor reductions in viscosity [

73]. This result does give merit to the assumption that carrageenan has some inherent UV resistance. Fucoidan also suffers from a distinct lack of data relating to UV radiation exposure. Some studies have shown that fucoidan may exhibit anti-photoaging effects in vivo [

74] and anti-bacterial activity post UV sterilization [

75], but the studied effects of UV exposure are not well covered.

Both Chitosan and Alginate remain the most widely characterised marine polysaccharides with a larger number of apparent studies carried out with UV radiation. Meynaud et al. studied the effects of UV radiation on chitosan bioactivity. The study found results that suggest UV exposure has no significant performance inhibiting effects on chitosan solutions. The results showed little to no structural modifications in the material through IR testing and it retained its anti-fungal properties [

76]. A study by Sionkowska et al. studied the effects of UV radiation on chitosan/tannic acid films. The study revealed that UV radiation caused significant degradation in the films. The tensile strength and elongation % of the chitosan films reduced from 70MPa-41MPa and 3.2%-0.9% over six hours of exposure. The Youngs modulus of the chitosan film increased from 1.75MPa- 3.01MPa over the same period. A study by Zhu et al. used riboflavin as a crosslinking agent under UV-light to improve the properties of chitosan films. The results of photo-crosslinking show a 50% reduction in WVP at 2%wtRf however, the mechanical properties suffered sharp reductions at 0%wt and 2%wt with a minor increase in TS at 4%wt-6%wt [

77]. Alginate has less evident characterization with UV sterilization, however several studies on hydrogels have been conducted. Al-Sabah et al. studied the effects of UV sterilization on sodium alginate hydrogels. The UV exposure caused significant reductions in internal pore size in the hydrogel as well as minor reductions in swelling capacity. The Youngs modulus and the porosity of the hydrogel saw slight increases over the same period which is evident of crosslinking taking place [

78]. Harriz Iskandar investigated the crosslinking capabilities of UV exposure on alginate-based hydrogels where he observed an enhancement in the gelation matrix of the hydrogel over a 120-minute exposure time. The study also revealed that the stability of the hydrogels was also enhanced allowing them to last for up to 10 weeks in comparison to previous data that indicated a 4-week lifespan. Mechanical properties of the hydrogels were also enhanced because of UV exposure [

79].

3.5. Autoclave

Hoffman et al. investigated the effects of autoclaving on the properties of xyloglucan scaffolds where they were sterilized at 121°C and 1 bar for 15 minutes. They found that samples sterilized using autoclave showed significant reduction in maximum stress and equilibrium modulus. The results of FTIR showed no significant alterations to the peaks of the materials using autoclave, this indicates that no major structural or chemical reactions occurred because of the autoclave process [

80]. Another study by Hashimoto et al. studied the effects of thermal treatments on the secondary structure of silk fibroin. They found that at temperatures above 60°C the structure of fibroin changed from silk I to silk II, however, the structural changes were not significant enough to cause adverse effects [

81]. These results suggest that silk fibroin is a potential candidate for further research in heat treatment and heat-based sterilization methods.

Starch has seen some characterization through heat treatments although the data does not provide a solid foundation for a meta-analysis. Zheng et al. investigated the effects of heat-based sterilization on the physiochemical properties of proso millet starch. They found that autoclave treatment increases the water holding capacity of starch by 91% while also causing a loss of crystallinity in the samples. The viscosity of the samples was also heavily impacted by autoclave treatment although DSC analysis showed enhanced thermal performance post autoclave. The established data for starch is minimal, but this study suggests that starch undergoes significant structural degradation in the presence of heat and humidity which has a considerable effect on the crystallinity of the sample [

82].

Marine Polysaccharides show a similar lack of data to many other biopolymers. While some data exists for alginate, fucoidan and chitosan, studies relating to the effects of autoclave on agar and carrageenan are extremely sparse. Zhu et al. investigated the potential of fucoidan as a marine prebiotic using autoclave as the sterilization method for their work. The FTIR analysis of the fucoidan showed no significant alterations to the functional groups post sterilization, however, the molecular weight analysis showed a considerable reduction. The reduction of molecular weight in this fashion indicates that the fucoidan experiences depolymerisation in the presence of high temperature sterilization which may affect the integrity materials it is contained within [

83]. Alginate remains one of the most well documented marine polysaccharides with autoclave sterilization with several relevant studies on the topic. Stoppel et al. investigated the effects of autoclave sterilization on the mechanical properties of alginate hydrogels. The results found that autoclave significantly affected the swelling capacity of the gels and a steady increase in stiffness across the measured frequency range [

84]. Another study on alginate hydrogels by Ofori-Kwakye & Martin investigated the effects of autoclave sterilization on the mechanical and morphological properties of calcium alginate gels. The study found that by increasing calcium content the modulus steadily increases, with a similar effect occurring with increasing alginate grade. The study observed a significant reduction in the shear modulus with gels formed from calcium alginate solutions that were autoclaved at 121°C for 15 minutes [

85]. It is evident from these two studies that autoclaving can negatively impact the mechanical properties of alginate hydrogels. The application of heat results in a stiffer gel with heavily impacted swelling properties. Further study into the chemical and thermal profiles of these gels under these circumstances would be necessary to fully understand how autoclaving can impact material performance. The effects of autoclave sterilization on chitosan have also been documented in several studies. Juan et al. investigated the effects of autoclave sterilization of different chitosan materials, flakes, solutions and hydrogels. The results suggest that chitosan flakes dispersed in water and autoclaved at 121°C for 20 minutes did not induce any significant degradation in the samples while autoclaving in standard conditions cause significant depolymerisation of the materials [

86].

A study by Gossla et al. investigated the effects of autoclave sterilization on chitosan fibres. The results of the study showed autoclave sterilization induced a minor change in UTS from 177Mpa -153Mpa and no significant changes to the tensile strength were noted. Conventional autoclaving also caused a minor reduction in Youngs modulus from 14GPa to 12GPa although autoclaving while submerged in water caused a significant reduction to 6GPa. This suggests some discrepancies between previous studies where chitosan flakes did not suffer any degradation [

87]. While the results do not match the difference between flakes and fibres could be significant and the lack of mechanical testing in the study Juan et al. may contribute to the discrepancy.

3.6. Dry Heat

Starch has seen a great deal of characterization with various heat treatment methods. Much like previously discussed biopolymers, sterilization studies have not frequently been carried out, but heat treatment studies can be used as a proxy to determine the potential effects and viability of dry heat sterilization. Noranizan et al. investigated the changes in physiochemical properties of several types of starch from varying botanical sources. The studied was carried out using wheat, tapioca, sago and potato starches and tested them for one hour at 100°C and 110°C for one hour and 120°C for one and two hours. The results showed that none of the samples exhibited and swelling power after two hours with wheat being the only sample to exhibit swelling capacity after one hour at 110°C The swelling capacity of all the starch samples was severely impacted (>50%) after 1 hour at 110°C with the exception of wheat showing a 20% increase [

88]. A study by Liu et al. studied the effects heat treatment had on waxy potato starch. The potato starches were tested at 110°C for 0.5h, 1.5h and 2.5h where a steady reduction in crystallization temperature was observed at each time interval. The solubility and swelling power of the samples were also increased over time [

89]. These results show some consistency with established data from autoclaving of starches where the overall solubility was enhanced, however, starch samples in the previously discussed data exhibited a total lack of crystallinity post sterilization which is not the case for the study by Liu et al. While there is a lack of data to complete a comprehensive analysis, it does suggest that humidity has a significant impact on the reductions in crystallinity of the samples

Marine polysaccharides also exhibit temperature sensitivity, however, there have been some relevant studies to characterise several polysaccharides. Eha et al. investigated the effects of short-term heat treatment on commercial carrageenan. The study was carried out by exposing the carrageenan to 75°C-115°C for 15 minutes and found that no significant difference was found in this range in the carrageenan gels. The study found that above this range the gelling and melting temperature of carrageenan gels steadily decreased where it was concluded that to avoid significant degradation in processing high temperatures should not be used [

90]. While the characterization of agars thermal degradation and some heat treatment studies are available, the context in which they have been completes is not entirely applicable to the context of sterilization, the data does suggest that heat treatments results in a more coarse microstructure and that agar thermally degrades in a single step fashion which may be beneficial for lower, shorter term heat based sterilization [

91,

92]. A comprehensive study by Saozo et al. investigated the properties of calcium alginate planar films after they underwent heat treatment at 180°C for 0, 4, 8, 12, 20 and 24 minutes. The results of the study found overall reductions in physiochemical properties in the materials with the planar films becoming thinner and more brittle over time suggesting some degree of thermal degradation in the alginate films at this temperature [

93]. The effects of dry heat on chitosan have been investigated by Lim et al., where they found that dry heat at 80°C or less produced chitosan with lower glass transition temperatures and improved solubility. Higher temperatures produced chromophores in the chitosan and caused reduced solubility and a significant colour change from white > yellow > brown [

94].

3.7. Ethylene Oxide

Starch has seen very little characterization with EtO sterilization as with many other biopolymers discussed. This could be because starch is a common additive to biopolymer blends and is often not a strictly singular processing material, many of the materials such as collagen and cellulose also fall into this category. The lack of data relating to EtO sterilization of these materials, despite it being one of the most common methods for these sensitive materials, supports this claim.

Chitosan and alginate remain the most studied materials in sterilization studies with a small number available for EtO. Marreco et al. studied the effects of EtO sterilization on the mechanical and morphological properties of chitosan membranes. The study evaluated several compositions of chitosan fibers and found that EtO sterilization slightly increased the membrane thickness for all but the first test samples. The tensile strength of the samples was reduced by an average of 20% with slight inconsistencies shown in the %strain at break over the four tests [

95].

3.8. Ozone

Not many studies are available for ozone sterilization, however, Rediguieri et al. investigate the effects of ozone on PLGA (Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)) scaffolds. The scaffolds were sterilized in a vacuum chamber and exposed to “pulses” or 20-minute intervals of ozone gas for 2,4, or 8 cycles. Results from FTIR and the morphological profile of the samples showed no significant changes due to ozone exposure with the infrared analysis showing no additional or altered peaks. The tensile properties of the scaffolds remained unchanged at two and four pulses but did suffer considerable reductions at eight pulses for tensile strength (3.41MPa – 2.91Mpa) and modulus (118MPa – 88MPa). The study showed that ozone was an effective sterilization method for PLGA scaffolds, removing all microbial life and not negatively impacting cell proliferation [

96].

Another study by Tyubaeva et al. focused on the effects of ozone sterilization on PHB fibers. The fibers were subject to 1-600 minutes of ozone exposure in a flow through reactor at 0.1 L/min. The study found that the mechanical properties of the fibers were significantly enhanced at 7 minutes of exposure with max strength increasing from 1.7N – 3.5N and elongation % from 3.4% - 7.6%. The crystallinity of the fibers saw a large initial increase at 4 minutes then steady decrease until the 20-minute mark where it began to steadily increase again. DSC results showed broader melting peaks as exposure time increased as the materials crystalline structure was degraded by the ozone while the peak also shifted to the right over time [

97].

3.9. SCCO2

The characterization of biopolymers using ScCO

2 is limited likely because the process is ineffective against endospores which is a significant barrier for the medical device industry. While the data are limited in this area there have been a small number of studies carried out. Bento et al. studied the effects of sequential ScCO

2 drying and sterilization on alginate-gelatin aerogels. The sterilization took place over a two-hour period using a 7.5-minute static period followed by a 4-6-minute depressurization cycle. FTIR analysis of the aerogel sterilized at 100 and 250 bar showed a broadened band at 1600cm

-1 with no additional peaks forming indicating that the process did not induce any chemical reactions in the material. DSC results showed no significant changes from the control sample while the samples sterilized at 250 bar showed a notable increase in Youngs modulus. The process was concluded to be effective with no detectable microbes on the samples post sterilization [

98].

3.10. Cold Plasma

An effective and environmentally safe method for sterilization exists in the form of cold plasma cleaning. The majority of surface contaminants, many of which are of a high molecular weight, contain organic bonds (C-H, C=O) which are readily broken by the vacuum ultraviolet energy generated by plasma [

99]. A secondary cleaning action is performed by the various oxygen species generated within the plasma field, which subsequently react with organic contaminants to for CO, CO

2 and H

2O resulting in an ultraclean surface [

100]. Numerous authors have displayed the effectiveness of cold plasma treatment in the inactivation of a wide variety of microorganisms including

E. coli [

101],

L. monocytogenes [

102],

S. aureus [

103], as well as fungal contaminants [

104]. In addition to its antimicrobial activity, cold plasma allows for surface modifications, molecular interactions and tailorability of functional properties of polysaccharide-based materials. Wan et al. showed that cold plasma treatment of whey protein isolate-carboxymethyl chitosan films significantly improved the performance, both mechanically and preservative, of the films when applied as a pork preservative. It was demonstrated that the application of the cold plasma increased the aggregation of the two polymers thus enhancing viscosity and viscoelasticity. These results from the intermolecular interaction caused by the cold plasma leading to an increase in disulfide bond formation. As polysaccharide-based packaging materials are known to be susceptible to moisture uptake, cold plasma treatment has been utilized to tailor the solubility of starch-based materials. Guo et al. utilized dielectric blocking discharge plasma treatment for the modification of potato starch films. Their results demonstrated that the surface of the produced films had been flattened post-treatment and exhibited the highest tensile strength and lowest water vapor permeability of tested materials [

105]. Sifuentes-Nieves et al. utilized plasma treatments to modify starch of varying amylose content ranging from 30-70% with higher amylose contents displaying an increased degree of hydrophobicity. The application of plasma promotes that oxidation of OH-groups to C=O groups, forming new hydrogen bonds thus increasing the hydrophobicity of the materials [

106].

4. Commercial Viability of Sterilized Biomaterials

4.1. Migratory Effects Caused by Sterilisation

One of the most notable dangers in the sterilization of polysaccharide materials is the potential for the creation and subsequent migration of toxic by-products. When considering the nature of synthetic polymers, and their inherent biotoxicity, it is likely safe to assume that the plasticizers, stabilizers, dyes, and other processing compounds used are not prioritized as being biocompatible when compared to biomaterials. The necessity of sterilization in the food and pharmaceutical industries can heavily impact these materials and the way they behave and interact with external stimuli (

Table 1) which has resulted in regulatory compliance and standards to dominate the industry

For polysaccharide-based materials the use of non-toxic and biodegradable additives is paramount in the formation of safe medical devices, food packaging and utility items. The necessity of biodegradation often requires the action of hydrolysis making these material and their constituent parts highly hydrophilic. This affinity for water can lead to water soluble gasses such as EtO and Carbon dioxide to absorb and become trapped in these materials leading to leeching of cytotoxic compounds [

107] which are serious regulatory concerns.

While EtO can be absorbed as a consequence of polysaccharides’ ability to degrade via hydrolysis, Autoclaving can induce hydrolysis in biomaterials [

95] causing a breakdown of the material structure and leeching of polymer components. The cleavage of glycosidic bonds in polysaccharides causes the polymer to reduce into simple sugars, acids and water [

96]. While typically non-toxic in nature, simple sugars can leech into food products and react with proteins during food preparation causing a Maillard reaction which has been known to produce mutagenic compounds with free amines in the food products [

97]. Similarly, dry heat treatments can cause thermal degradation in heat sensitive biopolymers and at significant temperatures >180

oC glycerol, a common plasticizer, can thermally dehydrate to form toxic acrolein [

98].

Methods that can produces significant oxidation in biomaterials can be considered the highest risk carriers from a regulatory context. The formation of free radicals that induce chain scission or crosslinking in materials can have a considerable impact on the material properties post sterilization when compared to other methods. Radiolysis of polysaccharide materials has shown the formation of formyl free radicals which react with hydrogen to form formaldehyde [

99] a compound known for its extreme toxicity [

100]. Minor secondary reactions of radiolysis can also produce acetic acid, particularly in the degradation of hemicellulose materials [

101]. In low concentrations acetic acid is generally safe and a food additive however higher concentrations, particularly when inhaled, have adverse effects [

102] and the potential for continuous free radical action and interaction with food content post sterilization is not well covered in literature. Ozone sterilization is also a highly oxidative technique which can form carboxylic acids as well as aldehydes in polysaccharide materials [

103]

4.2. Alteration of Physiochemical Properties

E-beam technologies have shown to compromise the molecular structure of biopolymer materials in sterilization applications of both medical devices and food packaging applications. The consistency of a minor or in some cases significant boost to materials elastic modulus at mid-high range doses is a direct result of free radical interactions within the material. Chain scission was seen to reduce the relative crystallinity of materials which induced notable degradations in material performance while crosslinking’s’ modulus boosting effect resulted in a consistently more rigid and less flexible material. It is important to note that while these interactions persistently produced a reduction in mechanical, rheological and optical properties they have also produced increased WVP, density, and solubility in organic compounds including starches, cellulose and collagen as previously discussed, which resulted in them exhibiting increased modifiability due to alterations of their molecular structures.

Gamma radiation of materials induces phenomena that are characteristic of ionizing radiation. The process of chain scission and crosslinking are present in much of the data discussed. A notable interaction that gamma appears to have with biopolymers is a sharp increase in their gelling properties with some studies suggesting gamma radiation as a means of gel preparation. The effects of gamma radiation on biopolymers from established literature show promising results. In some cases, considerable increases in mechanical performance have been observed without the expected reduction in elongation and increased rigidity of the material. While gamma sterilization still interacts with and cleaves the backbone structures of irradiated materials the reduction in chain scission is likely due to the reduced dosages required for effective sterilization. The data also suggests some potential degradation inhibitors namely konjac glucomannan and to a lesser extent amylopectin in starches have been observed to reduce the overall degradation and short chain reductions respectively.

While the effects of gamma radiation are discussed in the context of biopolymers, the data that is most readily available exists within the area of material modification. gamma sterilization of materials is generally complete at a specific and generally low dosage of 0.1-25kGy, many of the data available for material modification through irradiation far exceed these parameters. The effects of gamma sterilization on many biopolymers is still relatively unexplored and from the data discussed, can produce desirable properties in the irradiated materials. Further characterization of biopolymers using gamma radiation may allow for effective dosing for material enhancements.

The effects of x-ray sterilization on biomaterials is evidently not well studied, the lack of data is indicative that conventional methods of ionizing radiation are preferable to x-ray for several reasons, however, the importance of material characterization in this context cannot be understated. Further evaluating the potential of x-ray sterilization could provide some unique benefits such as the previously discussed ability of gamma radiation to significantly increase the gelling properties of materials. While the data are sparse it is logical to conclude that the common effects of ionizing radiation would be present in irradiated biopolymers although to what extent is unknown, however, the reduced exposure time required for x-ray, comparable to that of e-beam, suggests that the degradation effects may not be as prevalent as long-term exposure seen in gamma sterilization methods.

From established data UV radiation is not a widely adopted method for sterilization of biopolymers. It is evident that many naturally occurring elements exhibits some range of UV absorbance or blocking capabilities. This inherent resistance to UV has led to these materials’ use in sunscreen, UV blocking windows, paints and topical products. The data are few for direct sterilization and many of the cited data have UV exposure rates that range from one hour to several days exposure. Typical UV sterilization procedures are not carried out over extended periods, so it is difficult to identify prevalent trends, however, in many studies it appears that immediate exposure to UV radiation i.e., the first hour induces the most significant changes to material structure if they do not exhibit a UV resistance. Moreover, this resistance to UV radiation was beneficial in several studies in the context of photo crosslinking using a surfactant crosslinking agent which produced notable mechanical improvements in the material. The ability for amylopectin to resist several types of radiation is also significant with several studies across multiple sterilization methods citing similar results, the presence of amylopectin appears to inhibit the degradation both physically and morphologically in the materials it is present in. While UV sterilization methods may not be applicable for a range of naturally occurring polymers due to their resistant nature the photodegradation of these polymers is still an essential characterization for their environmental performance

While the effects of autoclave sterilization are not well documented for a significant number of biopolymers it can be concluded that, from established literature, the effects are primarily negative. Xyloglucan appears to exhibit higher degree of resistance to heat treatment than other biopolymers which is evident from the lack of degradation from exposure to both heat and humidity. A common phenomenon observed in these studies, particularly with starch is the complete loss of crystallinity in the samples. Effects on marine polysaccharides show similar degradative effects, however, in some cases where multiple sterilization methods were used autoclaving did not cause a significant degradation. Overall, the outlook for autoclave treatment on these materials is poor, the materials’ innate vulnerability to water through hydrolytic reactions and the compounding effect humidity has on this phenomenon leaves autoclave as a mostly ineffective method of sterilization for biomaterials.

The data relating to dry heat sterilization of biopolymers is extremely sparse. Considering the low thermal resistance of many biopolymers this can be expected. The application of heat without humidity appears to induce different phenomena in biopolymers when compared to autoclave processing. The data suggests that the presence of humidity in the process can largely impact the effective crystallinity of the samples which can be attributed to hydrolytic degradation seen in many biopolymers.

The established data for EtO sterilization is exceptionally limited. With EtO being an ideal sterilizing agent for many sensitive materials this is somewhat unexpected. The data that is available seems to indicate that EtO sterilization can increase the mechanical properties while making the material slightly more brittle. The limited data may also be due to the duration of EtO processes. To eliminate any degree of trace chemicals from sterilized materials a long period of aeration is necessary which is typically 8-12 hours in length. This, paired with the 6–12-hour EtO exposure times leaves EtO sterilization as one of the longest duration methods available

The data for ozone-based sterilization methods for biopolymers is quite limited, however, from observation of the available literature ozone appears to be an effective sterilizing agent. Ozone exposure induces chain scission in PHB fibers even at relatively short durations although produced a significant increase in fiber mechanical performance. The reduction in crystallinity also effected the thermal profile of the fibers which contrasts with the PLGA which showed no notable structural or morphological differences post sterilization. The lack of data relating to ozone leaves it difficult to suggest any significant trends in the context of its effect on a range of biopolymers. More relevant data would be required in this area to fully understand ozone’s potential as a biopolymer sterilizing agent although the relative ease of synthesis and it not requiring the application of heat and humidity point towards it being a suitable process for biopolymer sterilization.

Despite the lack of data, ScCO2 is a promising sterilization technique that present a safer alternative to intensive processes such as EtO and thermal sterilization. The low operating temperatures make this process particularly suited for biopolymer sterilization, however, the consistent use of additives such as hydrogen peroxide to eliminate endospores is a significant disadvantage. From available data ScCO2 has negligible effects on the materials it is used with while its cycle times are far below processes such as EtO and Gamma radiation. More data are required for ScCO2 to fully understand its potential in both the food and medical industry but the further development of this process, where an effective method that results in a frequent 9-log reduction in spores, will present a sterilization process that may be suitable for a large portion of biopolymers in industry.

5. Commercial Advancements in Polysaccharides

With mounting pressure on businesses to adopt sustainable and circular practices, the biopolymer market has seen countless innovations over the past number of years. A focus on renewable and non-toxic materials has pushed the continued development of biodegradable polymers in the food and medical industries. Recent controversies with microplastics and the growing understanding of their effects on the environment and the physical dangers they pose [180] have pushed consumers and businesses to pursue user friendly alternatives.

Development of marine polysaccharides have greatly benefited from these circumstances with a considerable range of applications as food packaging alternatives and physical benefits being explored [

18]. These materials represent a cheap and extremely abundant source of material but have yet to be fully harnessed due to the difficult nature of their extraction, however, the growing understanding of these materials and their potential in industry [

123,

124,

125,

126] has seen greater focus on an effective and scalable solution [

127,

128,

129,

130] As the terms “renewable” and “sustainable” become more commonplace in the materials industry the development of higher yield extraction methods for many biopolymers have seen similar advancements [

131,

132,

133,

134]. Advancements to the scalability and effectiveness of extraction methods is a major component of these materials’ desirability for commercial use although the most significant factor is their performance under diverse and strenuous conditions.

The enhancement of biopolymers and their resulting resistance to external processes such as sterilization are paramount if these materials are to be considered as replacements for synthetic polymers. The development of biopolymer composites and blends have greatly increased the functional characteristics of biopolymers particularly with additives such as microcrystalline cellulose [

135,

136] gelatin [

137] and chitosan [

138,

139] The significance of the continued development and characterization of biopolymers in this regard cannot be understated as material performance under varying conditions and the ease of extraction and synthesis largely contribute to their implementation in industry as a whole.

6. Conclusion and Future Directions

The interaction between sterilization method and biopolymer structure varies significantly between methods and between materials. The inherent sensitivity of biomaterials and their susceptibility to undergo structural modifications with the application of different sterilization methods is relatively unexplored. Considering the structural properties of biopolymers and their viability for commercialisation post sterilization requires significantly more data than are available. A broad range of available methods and the data relating to them consist of a high variance in the degree of exposure times, dosages, and processing parameters.

The opportunity to fully understand these processes and their effects on material properties requires a commitment to the comprehensive study of sterilization processes and their optimizations in the context of sterilizing biopolymers. The scope of characterization by sterilization is clear from the established literature with each method of sterilization presenting a notably different interaction between process and material that can only be generalized due to the lack of consistent data for each material.

The furthered development and application of biopolymers in the food and medical industry as active packaging, medical devices and drug delivery agents will see a greater exposure to the processes of sterilization. To ensure these materials’ success in industry the effects of sterilization must be known as well as the development and enhancement of new fewer intensive methods. Sterilization presents an opportunity to enhance material properties through chain modification. In many cases the data suggests the preservation of the materials amorphous properties while providing notable increases in modulus and tensile strength, however, without consistent data or optimizations to the process, these enhancements can be negated or lead to degradation. The necessity for adequate regulation and compliance to be applied to these materials post sterilization is evident from the migratory effects possible via sterilization. Further examination of these migratory effects, particularly when exposed to external stimuli such as foods, and in vitro will be essential in providing safe, sterile and sustainable packaging and medical devices.

The importance of sterilization and their effects on biopolymers is significant. Where previously relative to these materials’ own development and usage in industry it is clear the development and generation of data for sterilization methods should be considered an essential characterization parameter for all biopolymers. This review provides a comprehensive evaluation of much of the available data relating to the sterilization of common polysaccharides detailing the structural effects and impact on material performance and migratory effects thereafter. This review attempts to highlight the significant gap in literature that is present the sterilization of biopolymers and both the necessity and opportunity for further research in this area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M. and D.M.C.; investigation, E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.; writing—review and editing, E.M, Y.C and D.M.C.; supervision, D.M.C; project administration, D.M.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No data was generated for the purpose of this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ritchie H, Samborska V, Roser M. Plastic Pollution. Our World in Data 2023.

- Johnson R. Polymers in Chemistry: Versatile Materials with Diverse Applications. Journal of Chemistry 2023;12.

- Lu J. Polymer Materials in Daily Life: Classification, Applications, and Future Prospects. E3S Web of Conferences 2023;406. [CrossRef]

- Velazco-Medel MA, Camacho-Cruz LA, Bucio E. Modification of relevant polymeric materials for medical applications and devices. MEDICAL DEVICES & SENSORS 2020;3:e10073. [CrossRef]

- Rudin A, Choi P. Chapter 1 - Introductory Concepts and Definitions. In: Rudin A, Choi P, editors. The Elements of Polymer Science & Engineering (Third Edition), Boston: Academic Press; 2013, p. 1–62. [CrossRef]

- Speight JG. Chapter 14 - Monomers, polymers, and plastics. In: Speight JG, editor. Handbook of Industrial Hydrocarbon Processes (Second Edition), Boston: Gulf Professional Publishing; 2020, p. 597–649. [CrossRef]

- Smith O, Brisman A. Plastic Waste and the Environmental Crisis Industry. Crit Crim 2021;29:289–309. [CrossRef]

- Mohanan N, Montazer Z, Sharma PK, Levin DB. Microbial and Enzymatic Degradation of Synthetic Plastics. Front Microbiol 2020;11:580709. [CrossRef]

- Naderi Kalali E, Lotfian S, Entezar Shabestari M, Khayatzadeh S, Zhao C, Yazdani Nezhad H. A critical review of the current progress of plastic waste recycling technology in structural materials. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2023;40:100763. [CrossRef]

- OECD. Global plastic waste set to almost triple by 2060, says OECD. OECD 2022. https://www.oecd.org/en/about/news/press-releases/2022/06/global-plastic-waste-set-to-almost-triple-by-2060.html (accessed August 19, 2024).

- Ghasemlou M, Barrow CJ, Adhikari B. The future of bioplastics in food packaging: An industrial perspective. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2024;43:101279. [CrossRef]

- Wellenreuther C, Wolf A, Zander N. Cost competitiveness of sustainable bioplastic feedstocks – A Monte Carlo analysis for polylactic acid. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2022;6:100411. [CrossRef]

- Xiao L, Wang B, Yang G, Gauthier M. Poly(Lactic Acid)-Based Biomaterials: Synthesis, Modification and Applications. Biomedical Science, Engineering and Technology, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo HS, Reis RL. Enzymatic Degradation of Biodegradable Polymers and Strategies to Control Their Degradation Rate. Biodegradable Systems in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine n.d.

- Apriyanto A, Compart J, Fettke J. A review of starch, a unique biopolymer – Structure, metabolism and in planta modifications. Plant Science 2022;318:111223. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal S. Major factors affecting the characteristics of starch based biopolymer films. European Polymer Journal 2021;160:110788. [CrossRef]

- De Luca S, Milanese D, Gallichi-Nottiani D, Cavazza A, Sciancalepore C. Poly(lactic acid) and Its Blends for Packaging Application: A Review. Clean Technologies 2023;5:1304–43. [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar R, Zo SM, Narayanan KB, Purohit SD, Gupta MK, Han SS. Recent development of protein-based biopolymers in food packaging applications: A review. Polymer Testing 2023;124:108097. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim NI, Shahar FS, Sultan MTH, Shah AUM, Safri SNA, Mat Yazik MH. Overview of Bioplastic Introduction and Its Applications in Product Packaging. Coatings 2021;11:1423. [CrossRef]

- Atanase L-I. Biopolymers for Enhanced Health Benefits. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:16251. [CrossRef]

- Rosenboom J-G, Langer R, Traverso G. Bioplastics for a circular economy. Nat Rev Mater 2022;7:117–37. [CrossRef]

- Royer S-J, Greco F, Kogler M, Deheyn DD. Not so biodegradable: Polylactic acid and cellulose/plastic blend textiles lack fast biodegradation in marine waters. PLOS ONE 2023;18:e0284681. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Liao W, Huang Y, Wen Y, Chu Y, Zhao C. Global seaweed farming and processing in the past 20 years. Food Production, Processing and Nutrition 2022;4:23. [CrossRef]

- Thiviya P, Gamage A, Liyanapathiranage A, Makehelwala M, Dassanayake RS, Manamperi A, et al. Algal polysaccharides: Structure, preparation and applications in food packaging. Food Chemistry 2023;405:134903. [CrossRef]

- Sarangi MK, Rao MEB, Parcha V, Yi DK, Nanda SS. Chapter 22 - Marine polysaccharides for drug delivery in tissue engineering. In: Hasnain MS, Nayak AK, editors. Natural Polysaccharides in Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications, Academic Press; 2019, p. 513–30. [CrossRef]

- Beaumont M, Tran R, Vera G, Niedrist D, Rousset A, Pierre R, et al. Hydrogel-Forming Algae Polysaccharides: From Seaweed to Biomedical Applications. Biomacromolecules n.d.;22:2021. [CrossRef]

- Mišurcová L, Škrovánková S, Samek D, Ambrožová J, Machů L. Chapter 3 - Health Benefits of Algal Polysaccharides in Human Nutrition. In: Henry J, editor. Advances in Food and Nutrition Research, vol. 66, Academic Press; 2012, p. 75–145. [CrossRef]

- Sionkowska A. Current research on the blends of natural and synthetic polymers as new biomaterials: Review. Progress in Polymer Science 2011;36:1254–76. [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq A, Clochard M-C, Coqueret X, Dispenza C, Driscoll MS, Ulański P, et al. Polymerization Reactions and Modifications of Polymers by Ionizing Radiation. Polymers (Basel) 2020;12:2877. [CrossRef]

- Malinowski M. Using X-ray Technology to Sterilize Medical Devices. AJBSR 2021;12:272–6. [CrossRef]

- L’annunziata MF. 1 - NUCLEAR RADIATION, ITS INTERACTION WITH MATTER AND RADIOISOTOPE DECAY. In: L’Annunziata MF, editor. Handbook of Radioactivity Analysis (Second Edition), San Diego: Academic Press; 2003, p. 1–121. [CrossRef]

- Tafti D, Maani CV. X-ray Production. StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Boardman EA. Deep ultraviolet (UVC) laser for sterilisation and fluorescence applications n.d.