1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, triggered by the emergence of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, was first identified in late 2019 and swiftly evolved into an unprecedented global health crisis. By early 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared it a pandemic, underscoring the scale and severity of its impact [

1]. This event marked one of the most consequential public health emergencies in modern history, affecting virtually every aspect of human life. The pandemic has profoundly influenced societies, economies, and scientific endeavors, compelling nations to reevaluate their priorities and exposing critical vulnerabilities in healthcare systems, infrastructure, and governance worldwide. Its far-reaching effects have catalyzed significant shifts in global policies and practices, with implications that continue to unfold.

COVID-19 placed unprecedented pressure on medical sciences. Healthcare systems faced shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), ventilators, and hospital beds. Frontline healthcare workers were stretched thin, often working under perilous conditions. At the same time, the pandemic disrupted routine healthcare services, delaying treatments for non-COVID-19 conditions and impacting preventative care such as vaccination programs [

2].

Research priorities shifted dramatically toward understanding SARS-CoV-2, developing diagnostic tools, and producing effective therapeutics and vaccines. However, this rapid pivot often came at the expense of ongoing research in other areas. Clinical trials for non-COVID-19-related treatments were delayed or canceled most funding streams were redirected toward pandemic-related initiatives. The pandemic also spurred innovations, such as telemedicine and digital health tools, which have since become integral components of healthcare delivery [

3].

The material sciences sector faced unique challenges and opportunities during the pandemic. The demand for materials used in PPE, such as polymers for masks and gowns, skyrocketed, leading to supply chain constraints [

4]. The need for antiviral coatings and filters stimulated innovation in materials engineering, with researchers exploring novel nanomaterials and biopolymers to enhance the efficacy of protective equipment [

5]. Additive manufacturing techniques such as 3D printing played a pivotal role in addressing supply shortages. Rapid prototyping capabilities enabled the production of critical components, such as face shields and ventilator parts, highlighting the value of decentralized manufacturing systems in emergency responses [

6,

7]. Disruptions and delays in global supply chains revealed the vulnerabilities of material procurement and logistics, prompting calls for more resilient and sustainable production methods [

8,

9].

1.1. The Role of Polymers in the COVID-19 Era

Polymers played an indispensable role during the COVID-19 pandemic, providing critical solutions across healthcare, personal protective equipment, medical devices, and packaging [

10]. The versatility of polymer materials, combined with their scalable production and cost-effectiveness, made them a cornerstone in the global response to the crisis. However, the unique demands of the pandemic also highlighted the need for tailored modifications in polymer properties to meet emerging and urgent requirements [

11]. The increased use of polymer-based products during the COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant rise in plastic waste, much of which is difficult or impossible to recycle [

12]. Single-use items such as masks, gloves, and packaging materials became essential but contributed substantially to environmental pollution [

13]. This surge in plastic consumption coincided with a slowdown in legislative efforts aimed at reducing single-use plastics, including bans on traditional polymer products. Many initiatives targeting the transition to sustainable alternatives were delayed as governments prioritized immediate public health and economic challenges. Consequently, the pandemic exacerbated the global plastic waste crisis, underscoring the urgent need for innovative and sustainable solutions in polymer science and waste management [

14,

15].

The pandemic underscored the critical role of polymers in healthcare systems worldwide. In medical devices, polymers were extensively used in the manufacturing of syringes, tubing, catheters, blood bags, and ventilator components. The properties such as flexibility, durability and low price of materials like polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyethylene (PE), and thermoplastic elastomers (TPEs) made them integral to these applications [

15]. Polymers also served as substrates for numerous diagnostic tools, including rapid antigen and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test kits, which were essential in tracking and controlling the spread of SARS-CoV-2 [

16].

Traditional polymers enabled the mass production of disposable medical products such as gloves, face masks, and gowns. The single-use nature of these items, primarily made from PE, polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET), minimized cross-contamination risks, safeguarding healthcare workers and patients alike [

17]. Beyond these applications, polymer-based hydrogels and nanomaterials contributed to the development of drug delivery systems and vaccine stabilization technologies, supporting the accelerated rollout of lifesaving treatments and immunizations [

18,

19].

The sudden surge in demand for PPE during the pandemic placed immense pressure on global supply chains, bringing polymers to the forefront of protective solutions. Polypropylene, a widely used polymer in nonwoven fabric production, became a key material for manufacturing surgical masks and N95 respirators [

20,

21]. Nonwoven PP provided an effective combination of filtration efficiency, breathability, and lightweight properties, crucial for long-term use [

22].

Polymers also enabled the creation of flexible and impact-resistant materials for face shields, typically fabricated from polycarbonate (PC) or PET [

23]. Additionally, the hydrophobic nature of many polymers enhanced their role as barriers against viral particles, while ongoing research explored the incorporation of antimicrobial and antiviral additives to further improvement of safety features of PPE devices [

24,

25].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the role of polymers in packaging expanded significantly due to heightened concerns about hygiene and contamination [

26]. Single-use polymer packaging materials, such as low-density polyethylene (LDPE), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), and PET, ensured the safe transport and storage of medical supplies, pharmaceuticals, and food products [

27]. In the pharmaceutical industry, polymers were critical in vaccine packaging, including syringe barrels and multi-dose vials, which required precise material performance to maintain sterility and prevent leakage. The pandemic also spurred innovations in flexible packaging, leveraging multilayer polymer films to create robust, lightweight, and airtight solutions for critical goods [

28].

1.2. Modification of Polymer Properties to Meet Emerging Requirements

Challenges posed by the pandemic necessitated advancements in polymer technologies to address specific needs. Research and development efforts focused on enhancing the mechanical, thermal, and antimicrobial properties of polymers to optimize their performance across diverse applications. In PPE production, modifications in polymer microstructure were pivotal in achieving higher filtration efficiencies without compromising breathability. For instance, electrostatic charging techniques were applied to polypropylene fibers in masks to improve their ability to trap aerosolized particles. Similarly, surface treatments and blending with nanomaterials increased durability, allowing extended or repeated use of protective equipment in resource-constrained environment [

29,

30,

31]. Another major innovation during the COVID-19 era was the integration of antimicrobial and antiviral agents into polymer materials. Silver nanoparticles, copper oxide, and zinc oxide were incorporated into materials and surface coatings to create self-sterilizing materials capable of reducing viral loads [

32,

33]. These functionalized polymers found applications not only in protective gear but also in high-touch surfaces in healthcare facilities, public transport, and packaging [

34]. The surge in polymer use during the pandemic raised concerns about environmental sustainability, particularly regarding single-use plastics. In response, researchers explored biodegradable and bio-based polymers, such as polylactic acid (PLA) and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), as alternatives to conventional materials [

35,

36]. While these solutions are not yet widely adopted due to cost and scalability challenges, the pandemic catalyzed interest and investment in sustainable biopolymer technologies development [

37]. Sterilization and reuse of medical equipment became critical in addressing shortages during the pandemic. Polymers with high thermal and chemical resistance, such as polyetherimide (PEI) [

38,

39] and polysulfone (PSU) [

40,

41], were utilized in applications requiring autoclaving or exposure to strong disinfectants. Tailored polymer blends and coatings further enhanced resistance properties, enabling repeated decontamination cycles without material degradation [

42,

43,

44].

2. Polymers in Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

2.1. Common Polymers Used in PPE

Polymers are essential for personal protective equipment (PPE) they provide durability flexibility chemical resistance and comfort [

45]. This text reviews polymers used in PPE discussing their properties applications and recent improvements. It also examines environmental sustainability challenges and strategies to enhance performance and reduce ecological impact. The study emphasizes the crucial role of polymers in PPE across healthcare manufacturing and environmental protection industries while exploring future directions for greener and more efficient materials.

2.1.1. Polypropylene, Polyesters, Polyurethane

Polypropylene

Polypropylene (PP) is a polymer extensively utilized in Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). It possesses remarkable chemical resistance coupled with affordability and straightforward processing. This material finds widespread application in the manufacturing of masks, gowns, and protective covers. PP exhibits exceptional durability while striking an optimal balance between flexibility and strength rendering it well-suited for diverse protective gear applications [

46] New research examines methods to improve plastic’s ability to be recycled and decrease its negative effect on the environment [

47]. Studies exploring environmentally-friendly methods for manufacturing PP are increasing. The goal is to enhance the material’s green credentials [

48].

Polyethylene

Polyethylene (PE) is a common material used in PPE. It is valued because it resists moisture and chemicals well. This makes it suitable for protective clothing like gloves and aprons. PE is widely utilized in medical and industrial protective gear due to its low cost and durability. PE’s impact on the environment has led researchers to explore biodegradable options as potential replacements [

49]. New ways of mixing polyethylene with other plastics are looking good. It’s improve performance but stay environmentally friendly [

50].

Polyvinyl Chloride

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is a material utilized in personal protective equipment like protective suits and gloves. It provides strong resistance against chemicals and physical damage [

51]. New work focused on lowering PVC’s harm to the environment. This led to making PVC from biological sources and plasticizers that are environmentally friendly [

52,

53]. Studies continue to investigate possible replacements for PVC that could reduce its impact on the environment.

Polyurethane

Polyurethane (PU) gets used for personal protective equipment because it’s flexible. It combines toughness and stretchiness. People often choose PU for demanding jobs like making gloves shoes, and protective pads. [

54]. PU provides great resistance against abrasion. However its lack of biodegradability poses a challenge. Scientists study bioPU and PU composites to improve sustainability [

55]. Recent advancements in PU-based personal protective equipment aim to enhance recyclability and minimize the material’s environmental footprint [

56].

Silicone

Silicone is a very useful material employed in personal protective equipment due to its ability to bend, resist chemicals and work well with living things. This makes it perfect for medical-grade items such as masks and seals [

57]. It endures intense heat and tough conditions. This makes it very helpful for industrial purposes [

58,

59]. Recycling silicone is still problematic. Researchers continue exploring ways to make silicone protective equipment less harmful for the environment [

60].

Polycarbonate

Polycarbonate (PC) is a material prized for its transparency and ability to withstand impacts. These qualities make it well-suited for protective gear like face shields and goggles [

46]. PC offers excellent safeguarding from physical dangers. It is a lightweight choice for personal protective equipment. Yet its rather high price and problems with ultraviolet deterioration have driven research into ultraviolet-resistant coatings and other protective options [

61]

2.2. Polymer Modifications for Enhanced Protection

2.2.1. Surface Modifications to Improve Antiviral and Antimicrobial Properties

Antimicrobial coatings stop infections from spreading. They make protective gear safer. This is important in healthcare places. Silver nanoparticles (Ag), copper oxide (CuO), and other antimicrobial substances get added to polymers used in protective gear [

62]. The coatings provide durable defense from bacteria viruses fungi. They work well for medical gowns gloves masks [

50]. Incorporating Ag particles into surfaces provides a broad-spectrum antimicrobial effect, as seen in studies that confirm their ability to disrupt microbial growth and biofilm formation [

63]. Quaternary Ammonium Compounds (QACs) work by disrupting microbial membranes, delivering long-lasting protection. Coatings made with titanium dioxide (TiO

2) utilize UV light to generate reactive oxygen species that effectively neutralize pathogens to increase antimicrobial properties, photocatalytic coatings or chemical-resistant coatings are used coatings made with TiO

2 utilize UV light to generate reactive oxygen species that effectively neutralize pathogens [

64,

65]. Chemical-resistant coatings are essential for protecting surfaces from harsh disinfectants. Materials like polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and other fluoropolymers boast outstanding resistance to chemical degradation and wear. Epoxy formulations create strong, impermeable barriers that resist the penetration of disinfectants. The flexible polyurethane coatings can endure both mechanical strain and chemical exposure. Self-healing coatings possess the ability to autonomously repair minor damages, ensuring the preservation of surface integrity and enhancing longevity. They contain encapsulated healing agents, such as polymerizable monomers, that get activated by cracks or scratches to seal any defects. For instance, coatings infused with Diels-Alder-based polymers have shown effective crack sealing insimulated environmental conditions [

66].

2.2.2.1. Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Adjustments for Improved Breathability and Filtration Efficiency

Hydrophobic surfaces are manufactured in a way that resists water and other liquid contaminations. This characteristic is frequently determined through contact angle measurements, where a contact angle greater than 90º stands for greater hydrophobicity. Adding and adopting methods such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD), behavour towards of the surface through plasma enhancement, or merely coating the desired surfaces with hydrophobic materials such as fluoropolymers and silanes has been quite common [

67]. That being said, the use of hydrophobic surfaces is desirable because they can minimize the contact of water, thus enhancing airflow and filtration efficiency. On the other hand also, hydrophilic surfaces have the capacity to draw water and ‘soak’ the moistures quickly, followed by spreading them across the surface. This is especially helpful in settings where condensate or sweat sedation can disrupt breathability. For hydrophilic modifications, grafting of polymers which are hydrophilic such as polyethylene glycol onto surfaces, treating surfaces via a plasma, oxygen or nitrogen species or adding hygroscopic additives into the material matrix have been used [

68]

2.2.2.2. Impact on Breathability and Filtration, Efficiency, Breathability

Breathability is the faculty of a material to let air flow through while still acting as a barrier against contaminants. Hydrophobic treatments help prevent water from blocking the pores, ensuring that airflow remains uninterrupted. Conversely, hydrophilic treatments effectively manage moisture, stopping the creation of vapor barriers that could obstruct air movement [

69]. Filtration efficiency is determined by how well a material can capture particles while keeping airflow resistance low. Hydrophobic treatments improve the material’s ability to repel liquid aerosols, which can cause pore clogging. Hydrophilic surfaces are beneficial fortrapping water-soluble particles, like salts and bioaerosols, thereby enhancing the material’s performance in humid conditions [

70].

2.2.2.3. Methodologies for Adjusting Hydrophobicity and Hydrophilicity Plasma Treatments, Chemical Coatings, Nanostructuring, Material Blends

Plasma processes, including oxygen or argon plasma, can alter surface energy to enhance eitherhydrophilicity or hydrophobicity. These techniques are super environmentally friendly and adaptable, making them suitable for a variety of materials [

71]. Surface coatings, for instance fluorinated compounds for hydrophobicity or hydrophilic polymers, can be applied using methods such as dip-coating, spray-coating, or spin-coating [

68]. Creating micro- or nanoscale surface textures can, enhance to the natural hydrophobic or hydrophilic characteristics of materials. For example, the Lotus Effect, which mimics the surface of lotus leaves, enhances hydrophobicity [

72]. Combining hydrophobic and hydrophilic elements within one material allows for adjustable performance depending on environmental conditions. Layered structures can also leverage the advantages of both properties [

73].

2.2.2.4. Applications and Environmental Protection

Healthcare in medical masks and gowns, it is essential to achieve the right balance of breathability and filtration efficiency. Hydrophobic surfaces help prevent fluid penetration, while hydrophilic layers draw away sweat for added comfort [

68]. Air and water filtration systems can benefit from these modifications to address pollutants in different humidity levels. Hydrophilic layers improve the removal of water-soluble contaminants, while hydrophobic layers help prevent clogging from liquid pollutants.

Adjustments in hydrophobic and hydrophilic properties allow for multifunctional performance that meets consumer demands [

74]. The development of materials that can switch between hydrophobic and hydrophilic states in response to environmental changes [

75]

2.2.3. Use of Nanocomposites and Biopolymer Coatings

Use of nanocomposites and biopolymer coatings has become increasingly common in the realm of material science and engineering. These innovative materials provide considerable advancements in a variety of applications, including packaging, automotive, and medical sectors. The combined effect of nanofillers in biopolymeric matrices leads to the creation of cutting-edge and eco-friendly protective solutions. Polymers play a crucial role in many industries, yet their performance, especially regarding durability and protection, often requires enhancement. Traditional methods for improving polymer performance involve adding nanomaterials and applying biopolymeric coatings. Nanocomposites, which integrate polymers with nanoscale fillers like nanoparticles, nanotubes, or nanoclays, have demonstrated significant gains in mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties. Concurrently, biopolymer coatings are increasingly employed to offer protective layers that are both effective and environmentally responsible. These enhancements are becoming a vital component of strategies aimed at developing sustainable and efficient protective materials [

72,

76]

Nanocomposites are defined as materials that feature a polymer matrix combined with nanoscale fillers. By integrating nanoparticles into the polymer matrix, various properties can be significantly improved, such as mechanical strength, thermal stability, and barrier performance The interaction between the nanofillers and the polymer matrix plays a crucial role in enhancing dispersion, interfacial bonding, and the overall performance of the composite material. One of the main advantages of nanocomposites is their enhanced mechanical strength. Nanofillers like carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene oxide (GO) can significantly boost the tensile strength and elongation of the base polymer [

77]. Additionally, these nanomaterials improve the thermal stability of the polymer, making nanocomposites ideal for high-temperature applications. For instance, adding CNTs to epoxy resins leads to better thermal conductivity and enhanced thermal stability, which is vital in sectors such as electronics [

68]. Nanocomposites also provide improved barrier properties, which are critical in applications like food packaging, where protecting contents from moisture, oxygen, and other environmental factors is essential. The addition of nanoclays, such as montmorillonite, to a polymer matrix greatly enhances its resistance to gases and liquids [

78]. These enhanced barrier properties arise from the tight packing of nanofillers within the polymer matrix, which restricts the permeation of small molecules [

79]

Biopolymer coatings for environmentally friendly protection, sourced from renewable biological materials like starch, cellulose, and proteins, are gaining traction for their sustainable and eco-friendly characteristics. These coatings are mainly utilized to shield surfaces from environmental threats such as moisture, UV radiation, and microbial degradation. Biopolymers as protective coatings serving as a green alternative to conventional synthetic coatings that often depend on petrochemical materials, biopolymer coatings boast biodegradability and low toxicity. This makes them particularly suitable for packaging and agricultural uses. For example, chitosan, a biopolymer obtained from chitin, is widely used in food packaging as it effectively curbs microbial growth and prolongs shelf life [

80]. Antimicrobial and UV protection beyond their biodegradable properties, biopolymer coatings also offer antimicrobial protection. Chitosan, cellulose, and other biopolymers can be enhanced with antimicrobial agents, boosting their effectiveness in preventing microbial growth on surfaces [

74]. Additionally, these coatings can be fortified with UV-blocking agents, safeguarding the underlying materials from harmful UV radiation. This feature is especially beneficial for outdoor coatings and agricultural films. The combination of nanocomposites and biopolymer coatings has shown significant potential in improving the protective qualities of polymers. For example, adding nanocellulose to a biopolymer matrix has been demonstrated to greatly increase its mechanical strength, making it ideal for high-strength packaging materials. The synergistic interaction between nanomaterials and biopolymers facilitates the creation of advanced materials that are both high-performing and sustainable. These innovations are leading us toward a future where the environmental footprint of polymer-based products is reduced, all while maintaining or even enhancing their functionality. Furthermore, the medical field benefits from the antimicrobial properties of biopolymer coatings, which are applicable in wound dressings and surgical implants.

Despite the promising advantages, the development of nanocomposites and biopolymer coatings encounters several challenges. These include concerns regarding production scalability, the cost of raw materials, and achieving uniform dispersion of nanofillers within the polymer matrix. Additionally, the long-term stability and environmental implications of nanocomposites are ongoing areas of research. Future advancements in this field are essential for overcoming these hurdles and unlocking the full potential of these innovative materials.

2.3. Challenges and Innovations in Reusability

The development of reusable PPE continues. It happens because of the need to reduce medical waste, lower healthcare expenses and ensure sustainable infection control methods. However, making PPE reusable in medical settings faces several difficulties. At the same time, innovations in materials sterilization techniques and design are being utilized.

2.3.1. Challenges in Reusability of PPE

Sterilization and Infection Control

Challenge: Reusable protective equipment like face masks, gowns and gloves require proper sterilization methods to guarantee their safety for multiple uses. However, repeated exposure to sterilization processes such as autoclaving or chemical disinfection can weaken the material properties. This impacts their mechanical durability and ability to act as an effective barrier [

81]. Another worry exists about the risk of improper sterilization which might allow the spread of disease-causing agentsm [

82].

Solution: Recent advancements in sterilization technologies, including low-temperature plasma [

83] and hydrogen peroxide vapor [

84], provides better options compared to usual approaches. These new techniques treat materials with care yet still successfully eliminate microbes.

Material Durability

Challenge: Frequent cleaning and sanitizing of personal protective equipment can damage the materials. This leads to reduced protection. For example the non-woven fabrics used in medical masks and gowns may lose their ability to filter properly after being sterilized multiple times [

85].

Solution: New materials like strong plastics body-friendly mixtures, germ-fighting fibers make reusable protective gear last longer and work better. Adding tiny particles of silver helps kill germs and prevents wear [

86].

Comfort and Fit

Challenge: An important factor for personal protective equipment working well is how comfortable and well-fitting it is especially for extended use in medical facilities. Repeated sterilization can make materials less flexible and stretchy which may impact comfort and the protective equipment’s effectiveness [

87]. Achieving a secure fit is highly crucial for face masks. It prevents any leakage from occurring.

Solution: New materials like memory alloys and shape-memory polymers enable protective gear that keeps its shape and feels comfortable even after repeated sterilization [

88]. Designs with separate parts like straps or filters that can be swapped out or adjusted make protective equipment more comfortable and last longer [

89].

Cost and Accessibility

Challenge: Reusable protective gear brings financial advantages over time. However the upfront expense of quality materials and specialized sterilization tools can be too much for some healthcare facilities. This challenge is greater in areas with limited resources [

90].

Solution: Finding ways to mass-produce reusable protective gear in a cost-effective manner along with setting up centralized sterilization facilities could lower expenses. Affordable solutions involve using inexpensive biodegradable materials that offer adequate protection while being environmentally friendly [

91].

Innovations in PPE Reusability

Coatings for Extended Lifespan and Antimicrobial Resistance:

Innovation: Antimicrobial coatings applied to personal protective equipment can greatly improve reusability. They prevent the growth of bacteria viruses and fungi. These coatings allow the protective gear to last longer. They also reduce how often disinfection is needed [

92]. Coatings made from silver and copper have proven effective at preventing microbial growth on the surface of personal protective equipment materials [

93].

Application: Coatings that fight microbes decrease contamination. They also improve the toughness of materials by limiting the growth of biofilms which can cause material breakdown [

94].

Self-Sterilizing and Smart Materials

Innovation: Materials that can sterilize themselves like coatings that use light to break down harmful microbes provide a new way for protective gear to destroy pathogens on its own when exposed to light [

95]. The arrival of intelligent personal protective equipment with built-in sensors for detecting contamination or material deterioration transformed how we monitor the condition of protective gear [

96]

Example: Certain materials like titanium dioxide can break down harmful microbes when exposed to ultraviolet light. These materials are used to make protective equipment that takes advantage of this ability.Smart masks have sensors built into them. These sensors can check the air quality. The sensors will let you know when the mask requires replacement or cleaning.

Modular and Reusable PPE Designs

Innovation: Designs with separate parts allow replacing or cleaning certain components of protective gear like filters, straps and gloves. This extends the overall usable life of the equipment [

97]. This method cuts down on waste. It also permits improved customization of personal protective equipment for various healthcare duties.

Example: Face shields that can be used again have filters or straps that can be replaced. Gowns & gloves also have replaceable straps. This allows needed protection while reducing the need to throw away the full protective gear after each use [

57,

98].

Eco-Friendly and Chemical-Free Disinfection Methods

Innovation: Non-chemical disinfection techniques like UV-C light ozone treatment and electrostatic disinfection are becoming more popular. They sterilize personal protective equipment without harming the environment like chemical disinfectants [

99]. The techniques mentioned are both efficient and environmentally sound. They provide a green approach for reusing personal protective equipment.

Example: UV-C light systems can deactivate various harmful microbes on protective equipment surfaces. These systems are environmentally friendly and pose little risk to healthcare staff [

100].

The move to reusable PPE marks an important step for sustainability and cost savings in healthcare systems around the world. Challenges exist with sterilization, material durability, comfort, and cost. However, new developments in antimicrobial coatings self-sterilizing materials and smart designs could solve these issues. As research continues, sustainable and cost-effective reusable solutions for protective equipment will emerge. This will help reduce medical waste and improve safety for healthcare workers globally.

3. Traditional Polymers in Medical Devices and Equipment

Polymers are universal materials in healthcare because of their ability to meet stringent medical standards while providing design flexibility and scalability in production [

101]. Their light weight, sterility, and ability to be shaped into complex forms make them suitable for a wide array of devices. Additionally, polymers can be engineered to possess specific mechanical, thermal, or biological properties, allowing for tailored solutions in diverse medical fields [

102]. The use of polymers in catheters, surgical instruments, and prosthetics ensures patient comfort and safety, while their role in packaging medical products protects sterility and extends shelf life. In diagnostic applications, fossil based polymers provide the structural base for testing kits and imaging devices, enabling accurate and reliable results. Medical market is dominated by several traditional polymers mainly due to their proven performance, availability and low price (

Table 1). Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) is widely used in blood bags, IV tubing, and oxygen masks due to its flexibility and clarity. PVC is highly resistant to chemicals and can be sterilized, making it ideal for fluid-contact applications [

103,

104]. Common in disposable syringes, surgical masks, and medical containers is application of polypropylene (PP), thanks to its lightweight, mechanical strength, and resistance to autoclaving and irradiation it is considered a perfect material for single-use items [

105,

106]. Another fossil based polymer used widely in medical devices is polyethylene (PE). It can be found in applications such as implantable devices, catheter tubing, and medical devices packaging [

107]. PE is found to be biocompatible and chemical resistant what makes it valuable in medical devices requiring direct-contact with tissues [

108]. Another interesting example of adaptation of unique polymers properties to tailored applications is polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), which is utilized in intraocular lenses, dental prosthetics, and medical imaging equipment due to its optical clarity and mechanical strength [

109,

110]. One of the oldest materials applied in medicine is natural and silicone rubber. It can be found in implants, tubing, and seals, its flexibility, thermal stability, and biocompatibility are essential for applications involving prolonged bodily contact [

111].

The global demand for medical devices and equipment is substantial and continues to grow, particularly as healthcare systems expand and populations age the COVID-19 was a important factor in this case. Disposable medical devices account for a significant portion of this volume. Over 16 billion injections are administered annually worldwide, with each syringe contributing to medical waste. An estimated 129 billion face masks and 65 billion gloves were used monthly at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. The healthcare sector is responsible for 4-5% of total global plastic waste, which was approximately 300 million tons in 2020, but during the pandemic time, monthly use of disposable items like masks, gloves, and gowns surged dramatically, with some estimates adding 2.6 million tons of medical plastic waste per month to the global what accounted for approximately 10-15% of the global increase in single-use plastic waste [

112].

3.1. Modification of Polymers for COVID-19 Applications

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the importance of fossil-based polymers, such as PP, PE, and PVC, in the production of personal protective equipment (PPE), medical devices, and packaging. These polymers were critical due to their availability, cost-effectiveness, and versatile properties. However, the unique demands of the pandemic highlighted the need for specific modifications to enhance their performance, safety, and utility in combating the virus (

Table 2) [

113].

Enhanced filtration efficiency was a critical polymer modification during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic as it directly impacted the effectiveness of personal protective equipment (PPE). By improving the ability of polymer-based materials, such as polypropylene, to capture aerosolized particles, these modifications reduced the risk of infection for healthcare workers and the public. Effective filtration minimized the spread of the virus in high-risk settings, ensuring the safety of frontline responders.

Fossil-based polymers, particularly PP, were pivotal in the manufacture of nonwoven fabrics for surgical masks and N95 respirators. To improve the filtration efficiency of these materials against aerosolized viral particles, several modifications were developed. Melt-blown PP fibers were treated with an electrostatic charge to enhance their ability to attract and trap airborne particles. This modification, known as the electret process, improved the masks’ efficiency in filtering particles as small as 0.3 microns without increasing the material’s density or compromising breathability [

106]. Another modification which took place was in case of PP was adjustments in the manufacturing process that allowed for creating finer fibers and increasing materials surface area. Such a modification allowed to improve the physical barrier properties of nonwoven fabrics. This modification was achieved through advanced melt-blown and spun-bond techniques, optimizing the polymer’s structural attributes for enhanced performance [

114,

115]. Fossil-based polymers were often combined with other materials, such as nanofibers or hydrophobic coatings, to create multilayer structures that offered superior filtration and resistance to fluid penetration. These composites addressed the dual needs of respiratory protection and durability under extended use.

The integration of antimicrobial and antiviral properties into fossil-based polymers became a priority during the pandemic to reduce surface contamination and viral transmission risks.

Additives such as silver (Ag), copper (Cu), and zinc oxide (Zn) nanoparticles were embedded into PE, PP, and PVC matrices. These metals are known for their broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, including efficacy against SARS-CoV-2. The nanoparticles disrupted viral membranes or inhibited replication upon contact, making the polymers self-sanitizing [

116,

117,

118,

119]. Another antimicrobial enhancement was reached thanks to quaternary ammonium salts which were chemically bonded to the surface of polymers or incorporated during polymerization process. This approach enhanced the sterilizing capabilities of PPE and medical devices without compromising their mechanical properties [

120,

121]. To enhance the antimicrobial properties of selected materials titanium dioxide (TiO₂) and similar photocatalytic agents were applied to PP and PE surfaces to create materials that actively degraded organic contaminants under UV light, including viruses and bacteria. This innovation was particularly relevant for high-touch surfaces and reusable protective equipment [

122,

123].

The reuse and sterilization of medical devices and PPE became critical in addressing supply shortages during the pandemic. Modifications were made to materials to enhance their resistance to autoclaving, gamma irradiation, and exposure to strong disinfectants. Crosslinking agents were introduced to improve the thermal and chemical stability of PE and PP, enabling them to withstand repeated sterilization cycles [

124]. Polymer blends, such as PP with polycarbonate (PC), nitrile butadien or polyetherimide (PEI), provided improved mechanical strength and heat resistance, allowing devices to endure high-temperature decontamination processes [

125,

126,

127].

3.2. Biopolymers Development in Era of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed numerous advancements across diverse scientific fields, and biopolymer research stands out as one of the most impactful beneficiaries of this global crisis. The pandemic accelerated research into biopolymer-based medical devices, such as syringes, catheters, and drug delivery systems. Polylactide (PLA [

128] and polycaprolactone (PCL) were used in 3D-printed components, enabling rapid prototyping and localized production of essential medical supplies [

129]. Pandemic significantly accelerated research into different type of biopolymers, namely polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) due to their biodegradability and potential to replace conventional plastics in critical applications. PHAs, a class of biopolyesters synthesized by microorganisms [

36], garnered attention for use in PPE, medical devices, and packaging solutions. The increased demand for disposable PPE led to the exploration of PHA-based masks and gowns that could degrade in natural environments, reducing the ecological footprint of pandemic-related waste. Additionally, PHAs’ biocompatibility and antimicrobial potential were investigated for applications in drug delivery systems and wound dressings [

130,

131].

Research efforts during the pandemic focused on enhancing the scalability and cost-efficiency of PHA production by optimizing microbial fermentation processes and utilizing waste feedstocks. Innovations included tailoring PHA properties to improve flexibility, thermal resistance, and barrier capabilities, making them suitable for food and medical packaging. The pandemic also highlighted the need for robust supply chains, driving partnerships between academia and industry to develop sustainable PHA production technologies [

132]. These advancements have positioned PHAs as a key material in addressing both pandemic-driven demands and long-term environmental challenges.

PLA emerged as a critical material during the COVID-19 pandemic due to its biodegradability, biocompatibility, and versatility. However, PLA’s inherent limitations, including brittleness, low thermal resistance, and limited antimicrobial properties, necessitated modifications to expand its utility. The pandemic catalyzed research efforts to overcome these limitations, enabling PLA to address urgent needs in medical devices, PPE, and sustainable packaging.

Researchers focused mainly on improving PLA’s mechanical, thermal, and functional properties to meet the heightened demands of pandemic-related applications [

133,

134].

To meet the stringent requirements for medical applications, researchers modified PLA by blending it with additives such as PCL or PHAs. These blends improved PLA’s flexibility, impact resistance, and thermal stability, making it suitable for applications like 3D-printed face shields, ventilator components, and surgical instruments. Nanocomposite integration, including the incorporation of graphene and silica nanoparticles, further enhanced PLA’s mechanical and barrier properties, ensuring durability under prolonged use. The functionalization of PLA with agents such as Ag nanoparticles, Zn oxide, and chitosan imparted antiviral and antibacterial properties to PLA, enabling its use in PPE like masks and gowns. Studies demonstrated the effectiveness of these functionalized materials in reducing pathogen transmission [

135,

136]. The integration of pure and modified PLA with 3D printing technologies was a significant development during the pandemic. PLA’s ease of processing and biocompatibility made it a preferred material for rapid prototyping and localized production of medical components. Efforts to develop high-performance PLA filaments involved optimizing polymer chain orientation and incorporating nucleating agents, resulting in improved print quality and functionality [

137,

138].

Biopolymers also became pivotal in vaccine delivery systems. Nanotechnology-driven biopolymer platforms, including those based on chitosan, alginate, and polyethylene glycol (PEG), were instrumental in developing advanced vaccine formulations [

139]. For instance, these materials were used to create stable and efficient nanoparticles for mRNA vaccine delivery, enhancing immune responses and ensuring safe distribution. The flexibility and biocompatibility of biopolymers allowed for the development of innovative drug delivery systems, including hydrogels and nanofibers, which were tailored to improve therapeutic efficacy and patient outcomes [

140]. Another area of growth during the pandemic was the use of biopolymers in diagnostic tools and therapeutic devices. Biopolymer-based biosensors were developed for rapid and accurate detection of SARS-CoV-2, utilizing materials such as silk [

141] fibroin and graphene-enhanced biopolymers [

142]. These sensors offered advantages like high sensitivity, reduced cost, and environmental sustainability compared to traditional diagnostic methods.

4. Antibacterial Properties of Selected Particles Commonly Used for Polymer Modification

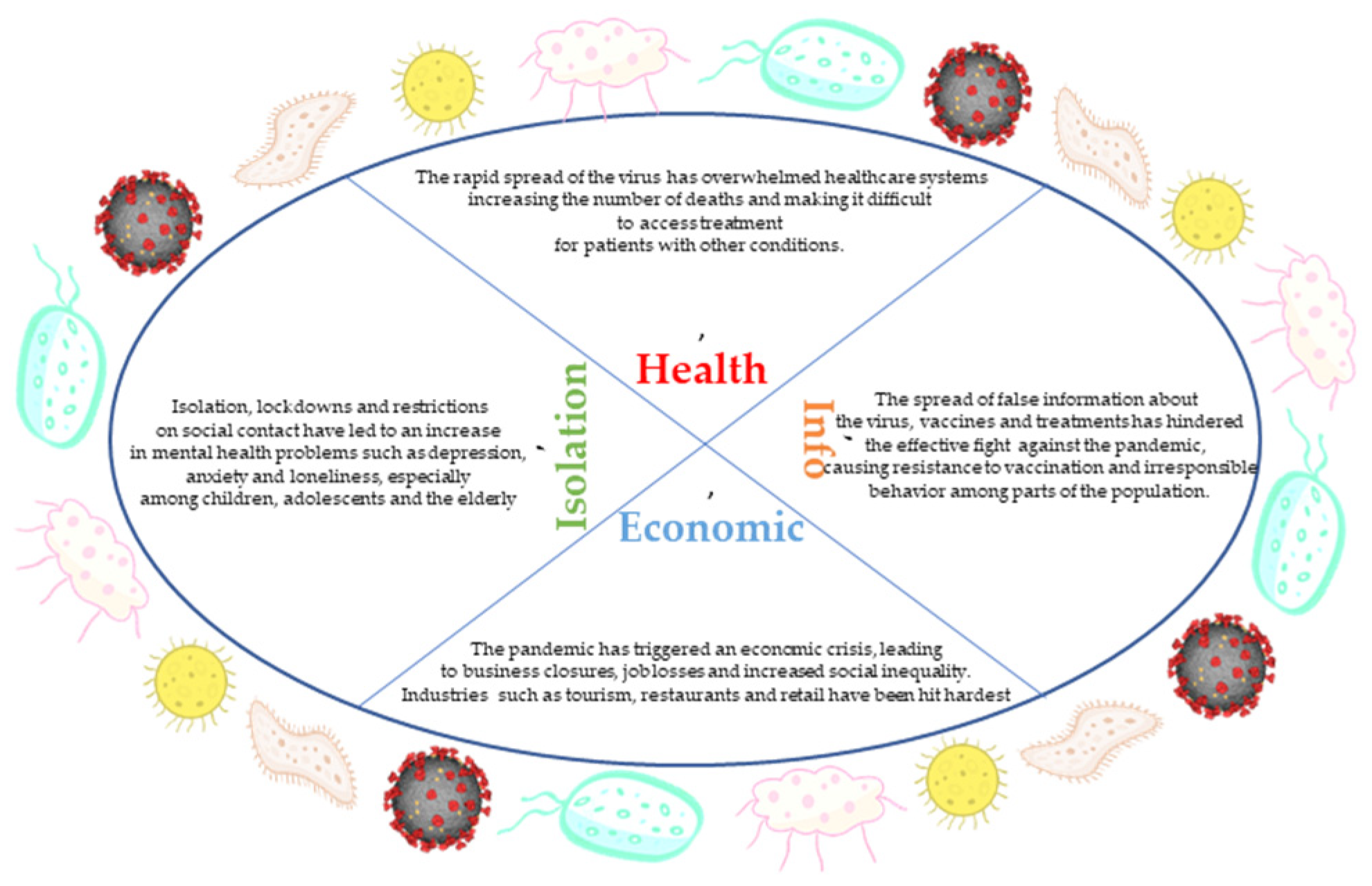

In the era of the coronavirus pandemic, the importance of antibacterial and antiviral materials, including particles with antimicrobial properties, has increased significantly. The pandemic has highlighted how crucial it is to control the spread of pathogens in public and private spaces. Threats in the coronavirus pandemic are presented in

Figure 1. The antibacterial properties of particles are now widely used to limit the transmission of bacteria, viruses and fungi. These materials eliminate microorganisms through a variety of mechanisms, including generating reactive oxygen forms, damaging cell membranes, and interfering with the metabolic processes of pathogens [

143,

144,

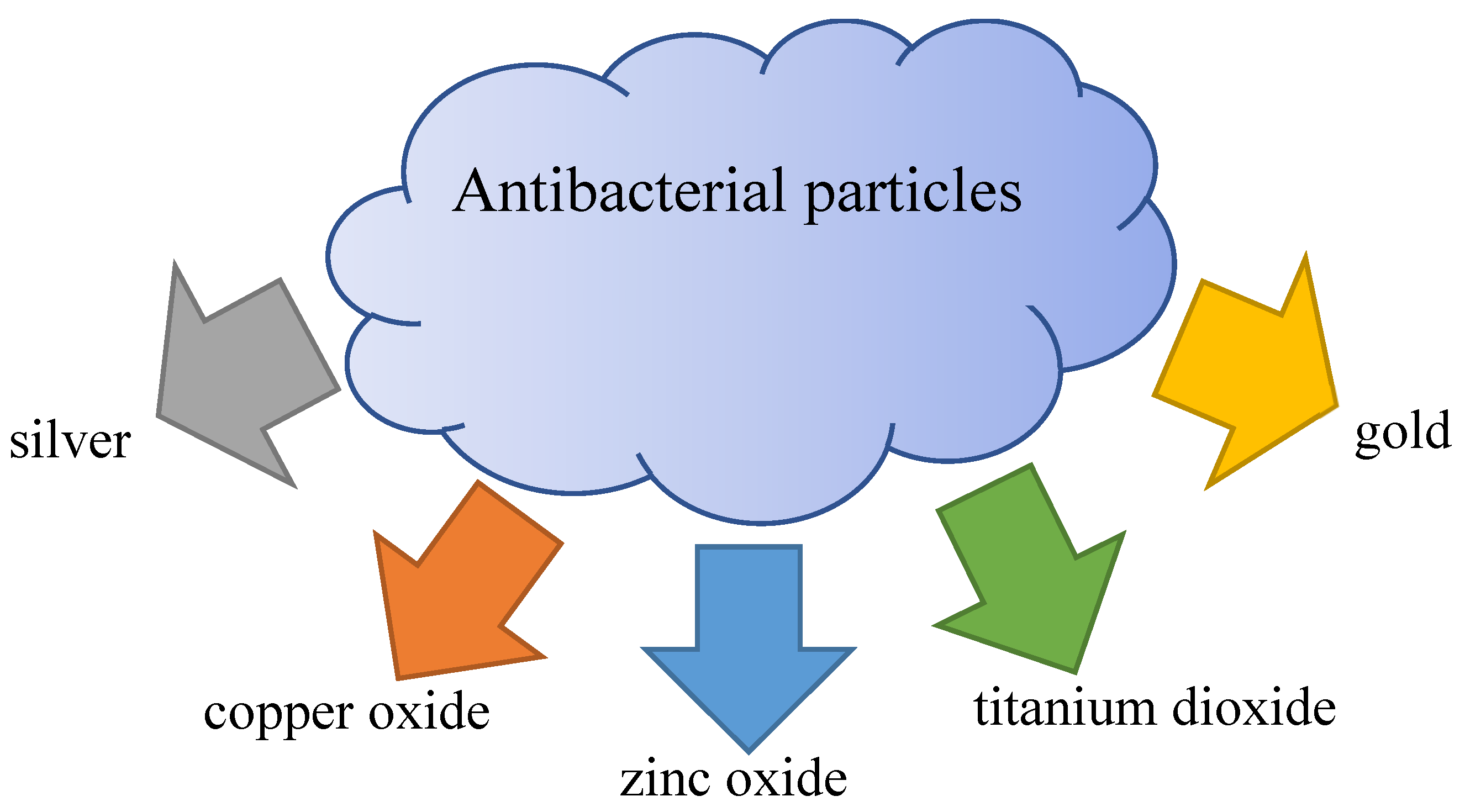

145]. The selected antibacterial particles are listed in

Figure 2.

This means they can act both prophylactically and in response to existing microbiological threats. Antimicrobial coatings and additives have found application in the production of textiles, packaging, medical equipment and touch surfaces. Their effectiveness and durability make them an attractive solution in places with a high risk of infection, such as hospitals, public transport and offices. A key advantage of these materials is the ability to provide continuous protection, which is an important complement to traditional disinfection methods, which are limited to momentary action [

146].

The pandemic has also changed society’s perception of hygiene and safety. There has been an increased demand for technologies that can reduce contact with pathogens in everyday life. Antibacterial materials significantly contribute to reducing the risk of infections by creating microbiological barriers. With the advancement of technology, it has become possible to produce materials that are both effective and ecological, which responds to the growing need for sustainable development.

Nowadays, particles with antimicrobial properties are also used in construction materials such as polymer composites or metal coatings [

147]. Their inclusion in such products improves both their functional properties and health safety. This allows us to create materials that are not only durable, but also actively limit the spread of microorganisms.

The future of antimicrobial materials lies in their adaptation to dynamically changing market and health requirements. Developing materials that are resistant to repeated washing and use is a challenge for materials engineers. At the same time, it is important to ensure their effectiveness against a wide range of microorganisms, including resistant strains. Antimicrobial materials are also a response to the growing demand for innovation in medicine, where their use can contribute to improving patient’s safety [

148,

149].

The pandemic has highlighted the need for interdisciplinary research in this field, combining knowledge from chemistry, biology and materials engineering. This approach allows for the design of materials with precisely tailored properties. This makes it possible to develop new generations of materials that are not only effective, but also compliant with the principles of the circular economy. As a result, the development of antimicrobial materials is a significant step towards improving the quality of life and protecting public health in the face of current and future epidemiological threats. Some of the most popular antimicrobial particles are silver, copper oxide, zinc oxide, titanium oxide, gold, aluminum oxide, and magnesium oxide. The action and detailed application of these particles will be described below.

4.1. Silver Nanoparticles

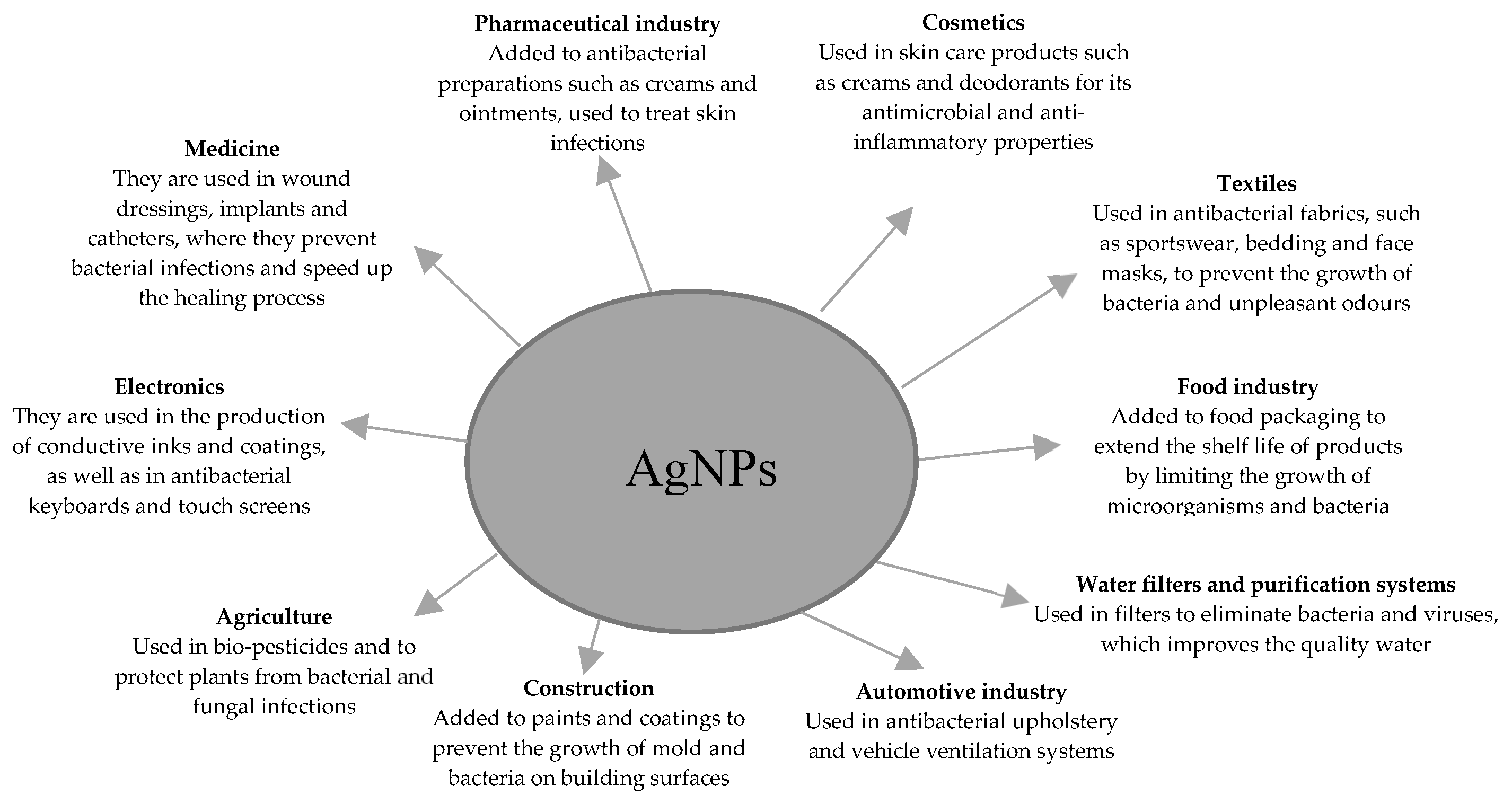

One of the most popular and widespread nanoparticles are silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). They have the ability to destroy a wide range of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. AgNPs exhibit strong antimicrobial properties that result from their ability to interact with bacterial and viral cells at several levels. First, Ag nanoparticles release Ag ions (Ag⁺), which react with thiol groups in microbial membrane proteins, disrupting their biological functions, such as ion transport and cellular respiration [

150]. Secondly, Ag nanoparticles can attach directly to the surface of bacterial cell membranes, leading to their destabilization and increased permeability, which causes leakage of cellular contents. In the case of viruses, these nanoparticles can bind to glycoproteins on their envelopes, hindering their entry into host cells. Furthermore, AgNPs can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals, which damage DNA, RNA, and microbial proteins [

151]. This mechanism leads to the inhibition of microbial replication and their death. In particular, Ag nanoparticles can penetrate into the bacteria or virus, where they directly interact with nucleic acids, causing disruptions in gene expression and replication. Their small size and large specific surface area allow for effective binding to microorganisms and high antimicrobial activity even at low concentrations. Due to the synergy of these mechanisms, Ag NPs are an effective antimicrobial agent that has found application in medicine, textiles, cosmetics and packaging. However, it is necessary to use them carefully, because excessive exposure can lead to the development of microbial resistance and potential side effects for higher organisms [

152,

153]. Range of Ag applications is presented in

Figure 3.

In the era of the coronavirus pandemic, not only antimicrobial particles have become popular and often used, but also plastic products have been and are used on a mass scale. Traditional polymer composites have often been used during the pandemic due to their good mechanical properties in relation to density and disinfection speed. The lack of a rough surface makes them safer than other substitutes. What’s more, these materials provide an excellent barrier against microorganisms, making them ideal for masks, gloves, and protective clothing. Additionally, their lightweight nature and ability to be molded into a variety of shapes make them easier to manufacture medical equipment such as ventilators, face shields, and sample containers. Plastics such as polypropylene (PP) are also used in HEPA filters, key to ventilation systems, and FFP2/FFP3 masks. Their low cost and ability to be manufactured quickly and on a large scale have made them an indispensable material in the fight against the pandemic.

There are many works in the literature on the modification of plastics using AgNPs [

154,

155,

156]. One of these works is the work of Oliani et al. who studied PP modified with AgNPs from 0.1%; 0.25%; 0.5%; 1.0%; 1.0% 2.0% to 4.0% by wt% [

157]. The films were tested against the following bacteria

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) and

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus). The studies showed that the addition of AgNPs resulted in the reduction of 100% of the tested bacteria. The work on the research on determining the effect of the SARS-Co-2 virus was the work of Medvevev et al. [

17]. PP fibers made by the melt-blown method were characterized for antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral activity. Samples with Ag concentrations of 0.1–1.0 g m−2 were prepared. Ag-modified materials have shown antibacterial and antifungal activity, especially at high Ag concentrations, and have proven effective against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Another work on the effect of AgNPs on the SARS-CoV-2 virus is the work of Assis et al. [

158]. The addition of AgNPs ranged from 0.5, 1.0 and 3.0 wt%. The antimicrobial activity of the composites was tested against the Gram-negative bacterium

Escherichia coli, the Gram-positive bacterium

Staphylococcus aureus and the fungus

Candida albicans. The best antimicrobial efficacy was achieved by the composite with α-Ag2WO4, which completely eliminated microorganisms within up to 4 hours of exposure. The composites were also tested for inhibition of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, showing an antiviral efficacy higher than 98% within just 10 minutes.

4.2. Copper Oxide

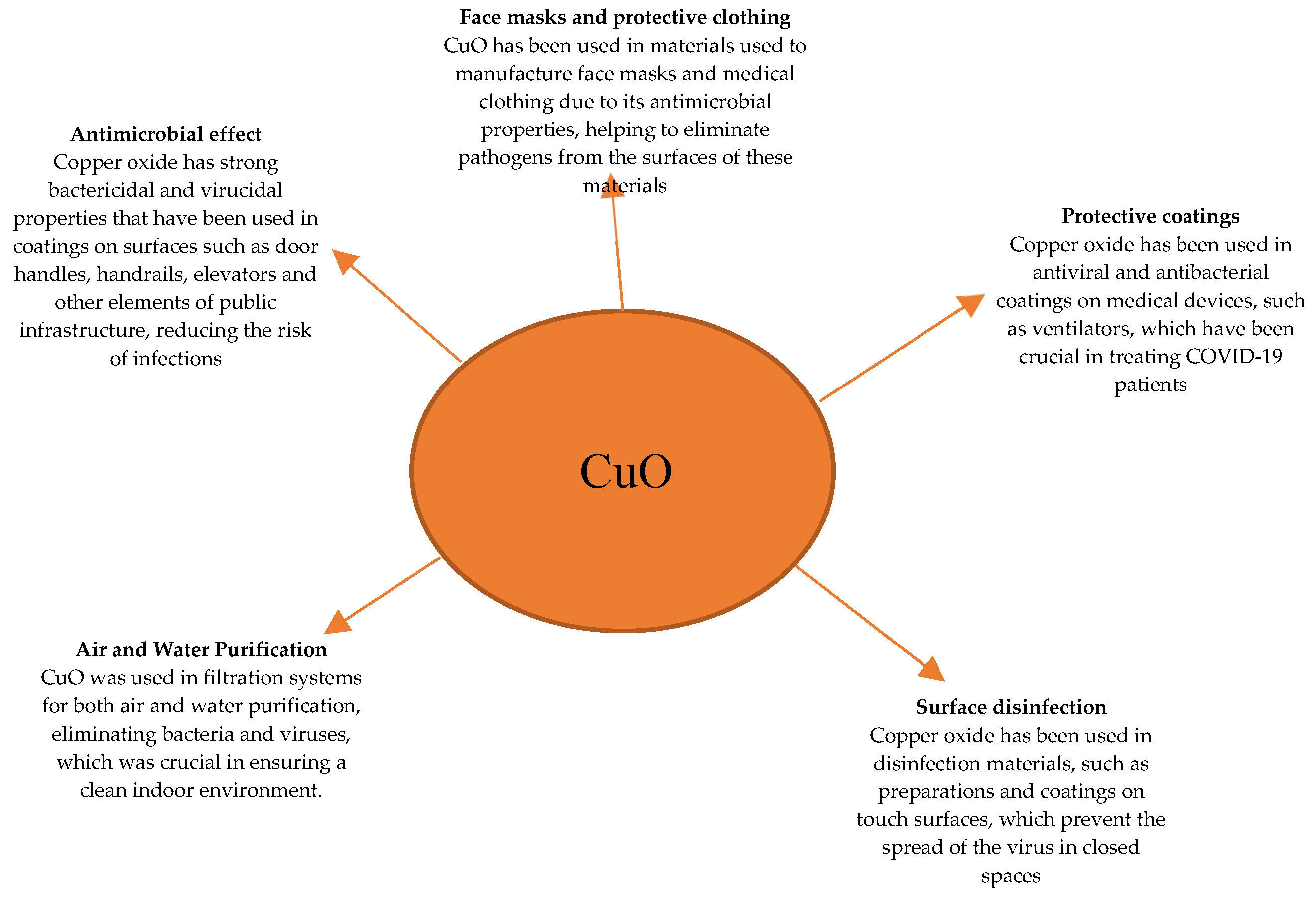

Another metal that exhibits antimicrobial properties is copper oxide (CuO). CuO exhibits strong antimicrobial properties through several mechanisms of action that effectively eliminate bacteria and viruses. First, CuO releases copper ions (Cu²⁺), which interact with microbial cell membranes, causing damage and increased permeability [

159]. Secondly, Cu ions can disrupt enzymatic functions in microbial cells by binding to thiol groups in key proteins, leading to disruption of metabolism and death of microorganisms [

160]. In the case of viruses, CuO binds to the protein coat of the virus or its RNA, preventing replication and infection of host cells. Additionally, CuO nanoparticles generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydroxyl radicals or hydrogen peroxide, which cause damage to DNA, RNA and membrane lipids of microorganisms [

161]. ROS can also fragment the genetic material of microorganisms, preventing their further functioning and proliferation. The small size of CuO nanoparticles increases their reaction surface, which allows for effective interaction with microorganisms even at low concentrations. Their ability to release Cu ions permanently and their chemical stability make CuO effective in the long term, making them effective in antimicrobial applications. It is worth adding that these mechanisms work synergistically, increasing the effectiveness of CuO against both bacteria and viruses. As a result, CuO nanoparticles are used in protective coatings, textiles, filtration systems and medicine. However, their use requires control to prevent potential toxic effects on higher organisms and the environment. Applications of CuO were presented in

Figure 4.

4.3. Zinc Oxide

Zinc oxide (ZuO) has become a versatile material supporting hygiene and public health protection in difficult pandemic conditions [

162]. ZnO is an inorganic chemical compound that occurs as a white powder with a wide range of applications. Its crystal structure is usually wurtzite (hexagonal), although it can also take the form of sphalerite (cubic) under certain conditions. The physical and chemical properties of ZnO include high thermal stability, a wide energy gap (approx. 3.3 eV), and the ability to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) under the influence of UV light, making it an effective semiconductor and photocatalytic material [

163,

164,

165] ZnO is insoluble in water, but it reacts in acidic and alkaline environments, forming zinc salts or complexes, respectively [

166]. It occurs naturally in the form of zincite mineral, but for industrial purposes it is most often synthesized.

ZnO reduces bacteria and viruses due to its unique physicochemical properties, acting in several synergistic ways. First, ZnO releases zinc ions (Zn²⁺), which can penetrate the cell membrane of microorganisms, disrupting enzyme function and metabolic processes [

167,

168]. Secondly, ZnO nanoparticles generate ROS such as hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl radicals and singlet oxygen, which damage lipid membranes, proteins and microbial DNA or RNA [

169]. In the case of viruses, ROS can degrade their protein envelopes and prevent replication in host cells [

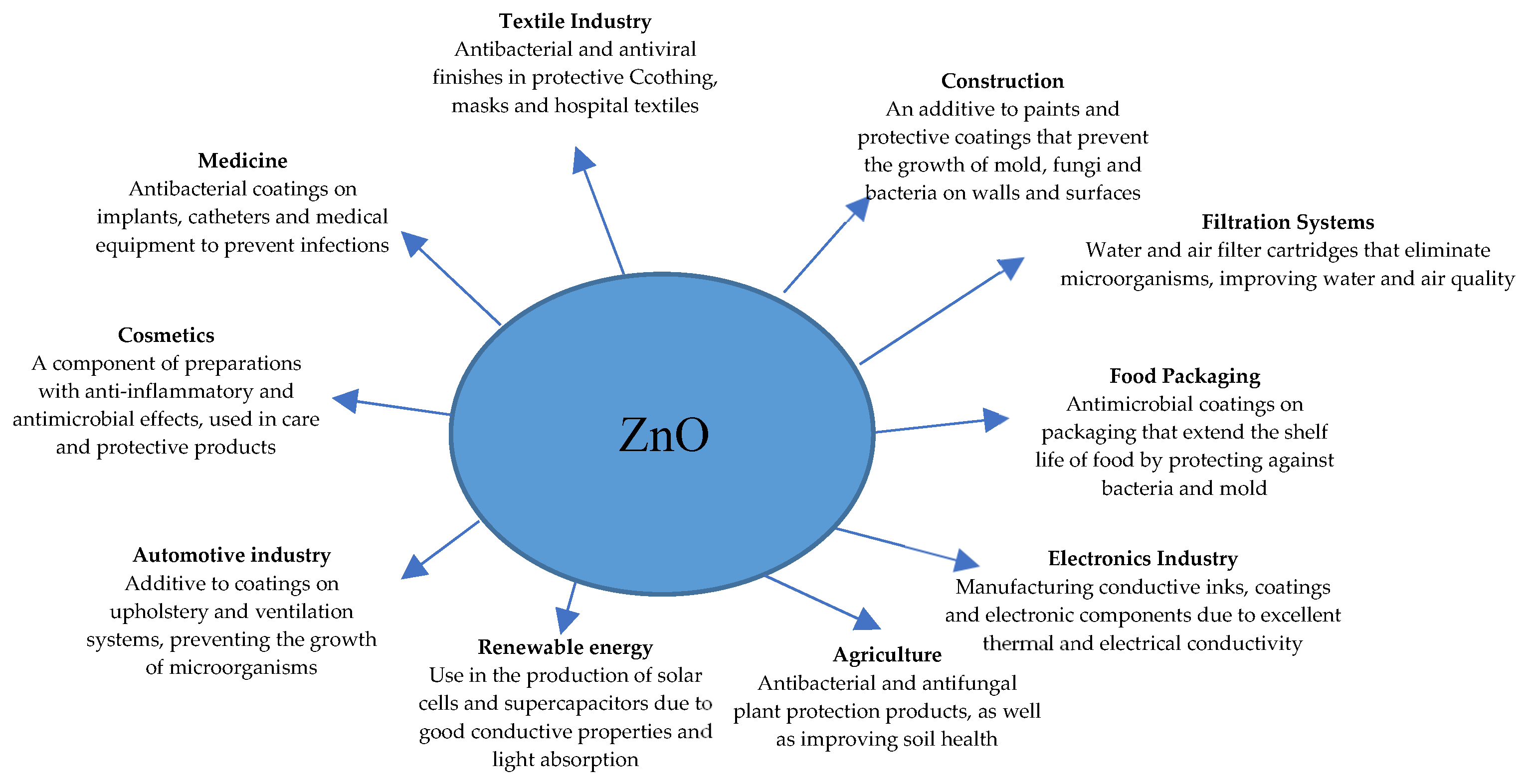

170]. ZnO can also bind to the surface of microorganisms, destabilizing their structure and leading to leakage of cytoplasmic content in the case of bacteria. Due to their semiconducting properties and wide energy gap, ZnO nanoparticles exhibit enhanced photocatalytic activity under the influence of UV light, which additionally increases the production of ROS. The small scale of ZnO nanoparticles provides a large reaction surface, which increases the effectiveness of their antimicrobial activity. In addition, their chemical stability and the possibility of sustained release of Zn²⁺ allow for long-term activity in various environments. These mechanisms together lead to effective inactivation of bacteria and viruses, which is why ZnO has found applications in medicine, water filters, protective coatings and cosmetics. However, it is important to control their applications to minimize potential side effects on the environment and higher organisms. Applications of ZnO were presented in

Figure 5.

The antibacterial activity of ZnO in polymer composites is widely described in the literature. Prasert et al. studied the effect of ZnO on the mechanical and antibacterial properties of PP [

171]. The samples were produced by injection molding and the ZnO content ranged from 0.5 to 2 wt.%. The antibacterial test results indicated that the nanocomposites had better antibacterial properties than unmodified PP. Another work on ZnO was that of Zhang et al. who produced PP fibers with a content of 1-5 wt.% [

172]. The degradation of PP fibers under the influence of UV radiation, antibacterial activity and mechanical properties were characterized. PP fibers filled with 3 wt.% ZnO nanoparticles showed better bactericidal efficacy against

S. aureus and

E. coli, with inhibition degree exceeding 99%. Not only PP was modified with ZnO but also polyethylene (PE). PE played a key role as a material for medical applications during the pandemic. Rojas et al. produced nanocomposites based on low density PE (3, 5 and 8 wt.%) with ZnO [

173]. The antimicrobial properties of UV-irradiated LDPE/ZnO nanocomposites reached 99.99% efficacy against

E. coli, regardless of the nanoparticle concentration and surface modification. Moreover, the antimicrobial properties of white light-irradiated nanocomposites were closely correlated with the nanoparticle concentration, reaching high antimicrobial properties of 96–99% against

E. coli for nanocomposites containing 8 wt.% ZnO and Mod-ZnO. The release of Zn cations was associated with the antimicrobial properties. Active antibacterial films based on LDPE with ZnO were investigated by Souza et al. [

174]. They evaluated physical properties and antibacterial activity against foodborne pathogens (

Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella Typhimurium and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) using liquid and agar disk diffusion tests. Active films contained 1.0, 2.5 and 5.5 wt.% ZnO. The best results were obtained for composites with 2.5 and 5 wt.% modifier.

4.4. Titanium Dioxide

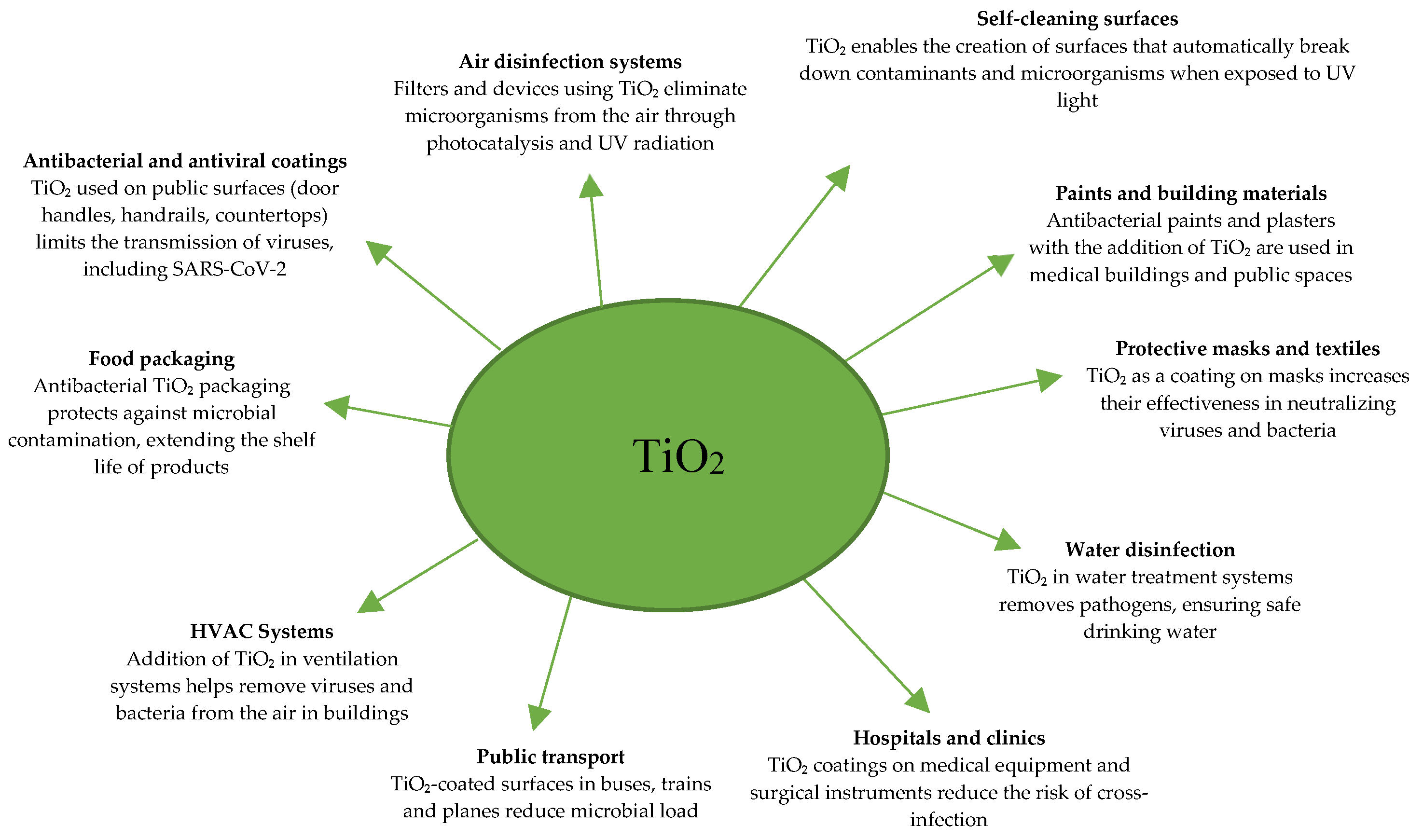

Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) has played a key role in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, becoming one of the most valued antimicrobial materials. Its unique photocatalytic properties mean that, when exposed to UV light, it generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), which effectively destroy bacteria, viruses and fungi. It is this ability to inactivate pathogens that has made it so popular in the face of the SARS-CoV-2 virus threat.

TiO₂ is widely used in creating self-cleaning surfaces that not only eliminate microorganisms but also decompose organic pollutants. During the pandemic, the possibility of using such coatings in public spaces such as hospitals, offices or means of transport has become particularly important. Its chemical and mechanical durability makes it a material that is exceptionally resistant to wear, making it an ideal addition to paints, ceramics, glass and polymer composites [

175,

176].

In medicine, TiO₂ has been used in antibacterial coatings of medical equipment and surgical instruments, which has contributed to reducing hospital infections [

177]. It is also used in air and water disinfection systems, including devices using UV light, which synergistically enhances its photocatalytic effect. TiO₂ is non-toxic, so it can be safely used in products that come into contact with food or skin.

In addition, its ability to reduce pollutants makes it an environmentally friendly material, which fits into the growing requirements of sustainable development. Studies on the effectiveness of TiO₂ against SARS-CoV-2 have shown its ability to quickly inactivate the virus, which has contributed to the growing popularity of this material during the pandemic. Titanium oxide is also widely available and relatively cheap, which allows for its use on a mass scale, from buildings to everyday products. Applications of TiO

2 were presented in

Figure 6.

TiO₂ is not only efficient, but also compatible with modern technologies, making it a material of the future [

178]. When combined with other antimicrobial compounds, such as CuO or Ag, it creates systems with even higher effectiveness. Its popularity in the pandemic is a result of not only high efficiency, but also multi-faceted usefulness, from medicine to environmental protection.

There are currently very few modifications of TiO

2 polymer composites in the literature. They most often concern antibacterial films [

179,

180,

181]. One of the few works is the work of Gonzalez et al. describing composites based on polylactide (PLA) modified with TiO

2 [

182]. Characterization was performed depending on the particle size (21 nm and <100 nm) and particle content (0%, 1%, 5%, 10% and 20%, wt.%). The behavior of the materials with respect to bacterial growth and biofilm development showed that the presence of TiO

2 nanoparticles significantly reduced the amount of extracellular polymeric substance and slightly changed the size of bacteria. With regard to the effect of particle size on the antibacterial efficacy of the nanoparticles, the results obtained in the Kirby-Bauer diffusion test were inconclusive.

4.5. Gold

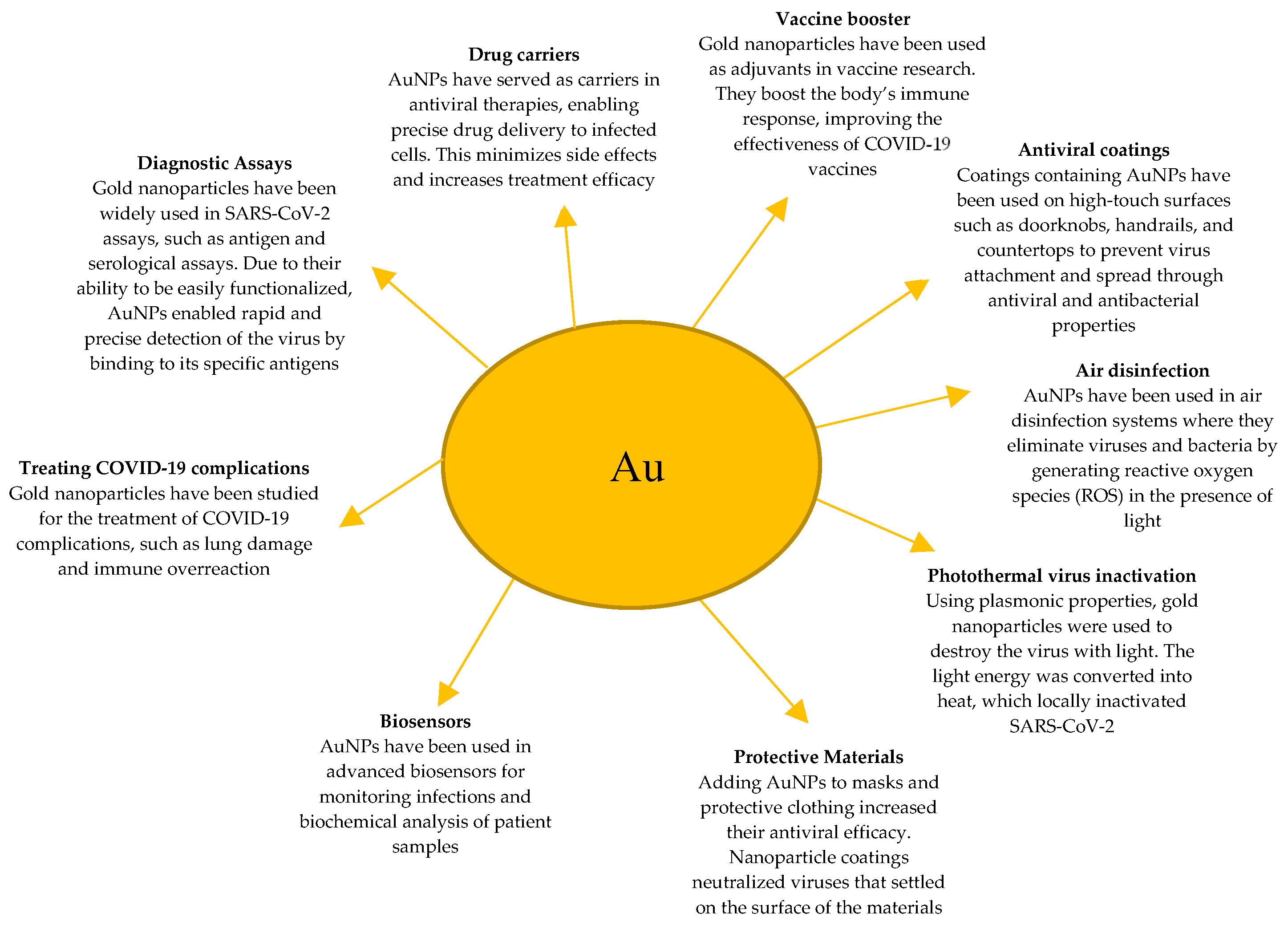

Gold (Au) has gained importance during the COVID-19 pandemic, both as a technological material and a strategic raw material. Its unique chemical and physical properties have made it play an important role in various fields [

183,

184]. Firstly, Au is a material biocompatible for mammalian cells while simultaneously beingantibacterial, making it ideal for medical applications [

185]. During the pandemic, it was used in antibacterial coatings that improved the hygiene of medical devices, such as diagnostic equipment and surgical instruments. In addition, Au played a key role in diagnostic technology. Au nanoparticles were widely used in SARS-CoV-2 tests, such as antigen and serological tests [

186]. Due to their ability to be easily functionalized and their high conductivity, Au nanoparticles enabled the creation of rapid and effective diagnostic tests that were irreplaceable in the fight against the pandemic.

Au particles, especially in the form of nanoparticles, exhibit unique antibacterial properties, which make them a promising material in the fight against bacterial or viral infections. Their mechanism of action is based on the ability to interact with bacterial cell membranes. Au nanoparticles can destabilize the cell membrane, leading to its damage and leakage of cellular components, which ultimately causes the death of bacteria [

187]. In the presence of light, Au nanoparticles generate ROS, which damage intracellular structures such as DNA, RNA, and proteins. Another important mechanism is the ability of Au nanoparticles to bind to thiol groups in bacterial enzymes, which inhibits their activity and disrupts key metabolic processes [

188]. In the presence of light, Au nanoparticles generate ROS, which damage intracellular structures such as DNA, RNA, and proteins. Another important mechanism is the ability of Au nanoparticles to bind to thiol groups in bacterial enzymes, which inhibits their activity and disrupts key metabolic processes. Au can also interact directly with bacterial DNA, preventing its replication and transcription, which stops bacterial growth and reproduction. It is worth emphasizing that Au nanoparticles act selectively and do not show toxicity to human cells at appropriate concentrations, which makes them a safe material for medical applications. Applications of Au were presented in

Figure 7.

Due to economic and availability reasons, Au is not used as a modifier for polymer composites, it is most often used for implants or membranes [

189,

190,

191]. One of the few works concerning Au-doped composites is written byof Ryan et al. [

192] in which they described the production of crosslinked chitosan with the addition of Ag and Au. It appears that the addition of Ag and Au NPs has no effect on the degree of bacterial adhesion, indicating that the metal NPs do not contribute to the antimicrobial activity, perhaps because they are not being released from the membrane in neutral conditions.

5. Biodegradable and Sustainable Polymer Innovations

Personal protective gear plays a vital role in safety measures across various sectors like healthcare, construction and manufacturing. As environmental concerns escalate, the demand for sustainable and biodegradable alternatives to traditional protective equipment materials has become paramount.

Environmental damage and health issues have raised the need for protective gear in many fields. Gear like gloves masks, face shields, and gowns often use materials like polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE). These materials do not break down easily and lack proper recycling methods which harms the environment [

59] (Yao et al., 2022). The need for environmentally friendly, long-lasting options for personal protective equipment (PPE) materials has become crucial in the fields of materials science and engineering. Environmental worries about plastic waste are increasing. Researchers focus heavily on biodegradable polymers for PPE. Materials like polylactic acid (PLA) and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) get explored. They could replace non-biodegradable plastics used in protective gear [

193]. The eco-friendly materials lower the lasting environmental impact of PPE. This benefit applies mainly to single-use items like masks and gloves [

194]. Progress has been achieved in enhancing the efficiency and eco-friendliness of PPE materials. However, issues persist regarding expenses large-scale production, and recycling capabilities. Incorporating nanomaterials and biodegradable elements into protective gear presents financial and manufacturing hurdles [

90,

195].

5.1. Traditional Materials in PPE and Their Environmental Implications

Personal safety gear mostly uses man-made plastics like PVC PP, and PE. These materials are cheap, long-lasting and easy to produce. They provide key qualities such as bendability, water resistance, and simple sterilization, making them suitable for protective uses [

90,

195]. The use of certain materials has major impacts on the environment. Employing PVC for gloves results in long-lasting pollutants. PVC proves extremely challenging to recycle [

196].

Many regular protective gear does not break down easily. It stays in landfills for a very long time. This adds to plastic pollution issues. There are few good ways to get rid of or recycle this gear. This makes the environmental impact worse. The buildup of used protective gear during health crises like COVID-19 shows we need sustainable solutions quickly [

197].

5.1.1. Challenges with Traditional Polymers

Traditional petroleum-based plastics have several key drawbacks that contribute to their environmental burden:

Non-Biodegradability: Plastics do not break down easily in nature. This leads to long-term pollution issues. Plastics remain in oceans, landfills and animal habitats for extended periods. This persistence of plastics in the environment raises significant concerns [

198].

Plastic Pollution: Plastic materials pollute oceans & land environments. They harm animals by getting eaten or tangling them up. Small plastic pieces from larger plastics breaking down are everywhere in water, dirt and air. These microplastics enter food chains and may risk human health [

199].

Resource Depletion: Making regular plastics depends a lot on petroleum resources that cannot be replaced. Extracting and processing fossil fuels harms the environment by destroying habitats and releasing carbon emissions [

200].

Recycling Limitations: Some plastics get recycled but many materials have low recycling rates. The recycling process requires a lot of energy. Also mixing different materials together contaminates the recycling streams. This reduces how well recycling programs work [

201].

5.2. Sustainable Alternatives for PPE Materials

New eco-friendly options are being created to replace regular protective gear materials. These alternatives include polymers from natural sources composites that can break down, and cutting-edge nanomaterials.

5.2.1. Bio-Based Polymers

Polymers made from renewable sources like plant starch cellulose and chitin provide an appealing substitute for plastics derived from petroleum [

202]. PLA has been studied for use in different personal protective equipment applications. This is because it can break down naturally and comes from renewable sources [

203]. Protective equipment made from PLA is appealing for disposable items such as face masks and gloves. These items get thrown away after one use. Although PLA can biodegrade its weaknesses in strength and resistance to moisture mean it needs further improvement for use in crucial protective equipment applications. PHAs are a type of bio-based polymers [

204]. They have potential because they can break down naturally. Their mechanical properties are similar to regular plastics [

205]. Scientists study PHA to use in medical equipment and protective gear for industries. Early findings show PHA performs well in tough conditions [

206].

5.2.2. Biodegradable and Hybrid Composites

A significant research focus involves creating composite materials that can break down naturally. These composites usually mix bio-based polymers with reinforcing agents like natural fibers or nanomaterials. For instance cellulose nanofibers have reinforced biodegradable plastics, enhancing their mechanical strength while retaining their environmental advantages [

207]. Materials combining natural fibers & bio-based plastics offer potential for personal protective equipment needing higher durability like protective clothing and safety footwear. Nanocomposites mix tiny materials like carbon nanotubes or graphene with degradable polymers. They boost strength fight microbes, and improve protective gear performance [

90]. The modern materials have possibilities for delivering top capabilities required for vital safety uses. At the same time they decrease environmental damage.

5.3. Recycling and Upcycling of PPE Materials

Reusing protective equipment materials poses a major obstacle. Standard recycling methods frequently cannot handle composite materials or contaminated items. Nevertheless recent progress in material science offers new possibilities for recycling protective equipment. Experts study ways to chemically recycle plastics. They break down plastics into small parts. These parts get reused for making new protective gear. This method follows circular economy ideas. It reduces need for new raw materials [

208]. Turning old protective equipment into new products has become popular lately. For example old face shields and gowns can be made into strong building materials or other high-quality items [

196]. Those techniques help the environment. They also create chances to earn money by cutting waste and making protective gear last longer.

5.4. Discussion on the Environmental Burden of Single-Use Plastics During COVID-19 (PPE, Packaging)

5.4.1. Challenges and Future Directions

Advancements occurred in creating sustainable protective equipment materials. However difficulties persist. Key issues involve confirming biodegradable materials perform well and last long enough in actual protective equipment uses. Also, sustainable materials must overcome high production costs and improve scalability for widespread adoption. Further research analyzing the full lifecycle impact of bio-based and recyclable protective equipment materials is necessary. This analysis should cover environmental effects from production through disposal.

More studies should look at combining sustainability with performance and cost-effectiveness. Creating advanced materials like strong biodegradable composites and self-healing materials could solve many issues with eco-friendly PPE. Further improvements in recycling tech and waste management will also help lower the environmental impact of PPE.

The need for protective equipment has increased, especially due to global health issues. This has highlighted the environmental impact of traditional materials used in making protective gear. Plastics like PVC, PP and PE have been widely used, but they have drawbacks for the environment. Exploring sustainable alternatives is necessary. Bio-based polymers, biodegradable composites, and innovative nanomaterials show potential for reducing the environmental impact of protective equipment. Also, advancements in recycling and upcycling technologies offer ways to create a more circular economy for these materials. Ongoing research and development in these areas are crucial to strike a balance between performance sustainability, and environmental responsibility in producing protective equipment.

The environmental impact of traditional plastics, especially single-use plastics, has become a major global issue. Conventional polymers derived from petroleum resources contribute to long-term environmental damage, harm to wildlife, and resource depletion. The COVID-19 pandemic worsened the situation with increased use of single-use personal protective equipment and packaging.

Plastics are very important in today’s world. They are used in packaging medical products, electronics, and many other consumer goods. However, their widespread use has caused serious environmental problems. Traditional plastics like PE PP, polystyrene (PS) do not break down easily. They remain in the environment for hundreds of years contributing to the growing plastic waste issue. As more people become aware of these problems, researchers are exploring biodegradable and sustainable alternatives to replace conventional plastics. This is especially relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic when the use of single-use plastics for personal protective equipment and packaging increased dramatically.

5.4.2. The Environmental Burden of Single-Use Plastics During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The coronavirus outbreak increased the environmental issues caused by single-use plastics. Worries about health and safety led to a rise in using disposable items made from regular plastics. Main areas impacted include:

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): The frequent utilization of single-use face coverings, hand protectors and protective garments alongside facial barriers led to an extraordinary surge in plastic waste accumulation. Approximations indicate that during the peak periods of the pandemic, global consumption exceeded 129 billion face masks and 65 billion gloves on a monthly basis [

209].

Packaging Waste: Restaurants shutting down & people shopping online more caused higher demand for single-use packaging. Takeout boxes, delivery bags & food wraps mostly made of plastic added to the increasing waste issue [

210]

Healthcare Waste: Hospitals produced huge quantities of plastic trash. This included syringes packaging for medical supplies, other single-use objects. A significant portion was considered dangerous waste requiring special disposal methods [

211].

Disrupted Waste Management Systems: The pandemic put a lot of pressure on waste management systems, making it hard to collect & properly get rid of the larger amounts of personal protective equipment & other plastic waste. In many situations, these materials could not be recycled making the challenges of waste disposal even worse [

212].

5.4.3. Biodegradable and Sustainable Polymer Innovations

Scientists created new materials to replace plastic. These materials can break down naturally or get reused. The goal is to reduce plastic waste harming the environment.

PLA is a biodegradable plastic produced from renewable sources like corn or sugarcane. It has been widely utilized for food packaging, disposable utensils, and medical equipment [

36]. However PLA needs industrial composting conditions to break down properly, restricting its application in areas lacking such facilities [

213].

PHAs represent a category of biodegradable polymers created by bacteria through the fermentation of renewable resources. These materials offer a promising substitute for petroleum-based plastics in applications like packaging and medical products. PHAs degrade in natural environments making them an appealing choice for decreasing plastic pollution [

214].

Starch-Based polymers obtained from crops like corn or potatoes are biodegradable. They find use in food packaging and disposable products. However these bioplastics lack durability compared to traditional plastics. They may not work well for all applications [

215].

Plant-Based bio-PE gets created from renewable plant sources like sugarcane. It possesses comparable qualities to regular polyethylene. Although not biodegradable bio-PE offers a more sustainable option. This is because it originates from renewable resources and generates a smaller carbon footprint compared to petroleum-based polyethylene [

216].

5.4.4. Recyclable Polymers

New progress aims at making polymers that fit current recycling systems. This involves creating “closed-loop” setups for materials like polyethylene terephthalate (PET) which can undergo multiple recycling cycles without quality loss.

5.4.5. Challenges and Future Directions