1. Introduction

Transdermal drug delivery systems are polymer-based compositions in the form of patches that are applied to the skin to provide controlled and predetermined drug release for systemic action. This method of administration is effective for the treatment of a number of clinical conditions, enabling the active substance to bypass the gastrointestinal tract and penetrate through the skin barrier directly into the bloodstream. In recent years, numerous types of patches with different mechanisms of action, properties, and excipients have been developed and tested, each offering distinct advantages and limitations [

1].

Polysaccharides such as gellan gum, chitosan, and agar-agar were selected as the polymeric framework in this study. Among these, gellan gum has attracted particular attention due to its excellent physicochemical, mechanical, and functional properties, which offer broad opportunities for biomedical applications. It is non-toxic, easily forms gels, exhibits mucoadhesiveness, and demonstrates high stability, biodegradability, and biocompatibility [

2,

3]. By combining gellan gum with other natural or synthetic polymers through cross-linking agents, its mechanical properties can be tuned, allowing the fabrication of scaffolds or dressings that are easy to apply to wounds [

4,

5]. However, a major limitation of gellan-based dressings in infected wound treatment is their lack of intrinsic antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. This limitation is the main rationale for incorporating additional copolymers or active agents into the polymer composite [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Furthermore, disadvantages such as the high melting point (90 °C), elevated gelation temperature, and reduced mechanical stability of gellan-based systems—caused by the exchange of divalent cations with monovalent ones over time—must also be addressed [

12].

Chitosan, a natural cationic polysaccharide, has attracted significant attention in the development of biomedical devices due to its unique physicochemical and biological properties. Its positive charge distinguishes it from most other polysaccharides and enables interactions with negatively charged biomolecules, providing antimicrobial activity, hemostatic potential, and enhanced cellular responses [

13]. Various chitosan-based systems have been reported, such as transdermal patches of isosorbide dinitrate prepared from chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol (1:9), and plasticized chitosan–starch patches (4:1) [

14]. However, these formulations still face limitations, including relatively low mechanical strength, susceptibility to enzymatic degradation, and reduced stability under highly acidic or alkaline conditions.

Despite these drawbacks, chitosan remains a highly promising biopolymer for wound dressing applications due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and ability to form hydrogels with tunable physicochemical properties. Chitosan-based hydrogels maintain a moist environment, absorb wound exudates, promote hemostasis, and provide protection against microbial invasion, thereby facilitating wound healing. At the biological level, chitosan enhances platelet and erythrocyte aggregation during the hemostatic phase, exhibits antibacterial activity in the inflammatory phase, and stimulates skin cell proliferation and granulation tissue formation during the proliferative phase, ultimately supporting tissue remodeling and wound closure.

The functional performance of chitosan hydrogels largely depends on the chosen crosslinking strategy. Two main approaches are widely applied: chemical crosslinking and radiation-induced crosslinking. Chemical crosslinking involves initiator-induced polymerization or UV irradiation in the presence of photoinitiators, forming covalent networks with enhanced mechanical stability. For example, highly porous chitosan hydrogels have been fabricated using ethylene glycol and foaming methods, while UV-induced crosslinking with polyethylene glycol diacrylate and Aloe vera extract has also been reported [

10,

15]. In contrast, radiation-induced methods, such as γ-irradiation, enable the synthesis of chitosan-based composite hydrogels (e.g., CS/Gel/PVA), yielding materials with favorable mechanical properties, pH sensitivity, swelling behavior, and water retention [

16].

Physically crosslinked chitosan hydrogels are generally safer, as they rely on biocompatible polymers without additional chemical agents. Nevertheless, they often exhibit insufficient stability, weak tissue adhesion, and limited mechanical strength. Chemically crosslinked hydrogels, while more robust and adaptable to different wound types, require extensive biocompatibility evaluation and sophisticated processing techniques, which may increase production costs and raise environmental concerns. Therefore, the rational design of chitosan-based wound dressings requires balancing biological safety with functional performance, selecting the optimal crosslinking approach to meet specific clinical needs [

17].

Agar, a natural polysaccharide extracted primarily from red algae (Rhodophyceae), has gained attention as a versatile biopolymer in the development of biomedical composites. Its structure is mainly composed of agarose and agaropectin, which confer excellent gelling ability, high water retention, and biocompatibility [

18,

19]. These properties make agar particularly attractive as an additive or matrix component in hydrogel-based wound dressings and transdermal patches.

In composite systems, agar improves the mechanical strength, moisture retention, and swelling behavior of hydrogels, thereby enhancing their performance as wound dressings. For instance, agar has been blended with chitosan to form hydrogel patches with improved porosity, controlled release of therapeutic agents, and accelerated wound healing capacity [

20]. Such chitosan–agar composites have demonstrated effective exudate absorption, antibacterial activity, and cytocompatibility, making them suitable candidates for biomedical use.

Moreover, agar contributes to the structural stability of hydrogel matrices under physiological conditions. Its thermo-reversible gelation behavior allows for facile processing and tunable mechanical properties, which can be advantageous in fabricating patches or films for controlled drug delivery [

21]. In addition, agar-based materials are generally recognized as safe (GRAS), further supporting their application in biomedicine.

Nevertheless, agar-containing composites may exhibit brittleness and limited elasticity, which restrict their direct application. To overcome these limitations, agar is often combined with other natural or synthetic polymers (e.g., chitosan, gelatin, polyvinyl alcohol) to achieve synergistic effects in terms of flexibility, degradability, and bioactivity [

22]. Such hybrid systems have been shown to enhance wound healing outcomes by maintaining a moist wound environment, reducing infection risk, and enabling the controlled release of bioactive molecules.

Taken together, agar serves as a valuable functional additive in polymeric composites for biomedical applications, particularly in wound dressings and patches. Its unique physicochemical properties, combined with complementary polymers, offer opportunities for the design of multifunctional and clinically applicable biomaterials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents for synthesis

Gellan gum, chitosan, and agar-agar were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Germany). Methylene blue, glutaraldehyde, acetic acid, sodium chloride, and calcium chloride were obtained from Merck (Germany). All reagents were used as received, without further purification.

2.2. Preparation of Polymer Patches

Gellan gum (1 g) was dissolved in distilled water under magnetic stirring until a homogeneous solution was obtained. Separately, chitosan solutions (0.25 g or 0.5 g) were prepared in 2% (v/v) acetic acid. The chitosan solution was gradually added to the gellan solution, followed by glutaraldehyde as a cross-linking agent. The mixture was continuously stirred on a magnetic stirrer equipped with a heating plate until a transparent solution was obtained. The resulting solution was then cast into molds. Additional cross-linking was achieved using sodium and calcium ions. In the preparation of samples 3 and 4, agar-agar was used as a substitute for gellan gum. After synthesis, the hydrogel samples were thoroughly washed with excess water, followed by ethanol, to remove unreacted components and residual impurities. The final hydrogels were dried in an oven at 40 °C until a constant mass was achieved and were subsequently stored in sealed packaging.

2.3. Patch Thickness

The thickness of the patches was determined using a caliper at multiple points (3–5 measurements), including the corners and center. The mean thickness and standard deviation were then calculated [

15]. The prepared samples exhibited a uniform thickness across the surface, with only 0.3–0.5% deviation.

2.4. Folding Resistance

The folding resistance of the patches was evaluated manually by repeatedly folding the same area until visible cracks or tears appeared. The resistance was expressed as the number of folds sustained before damage occurred and ranged between 42 and 70 [16, 23–25].

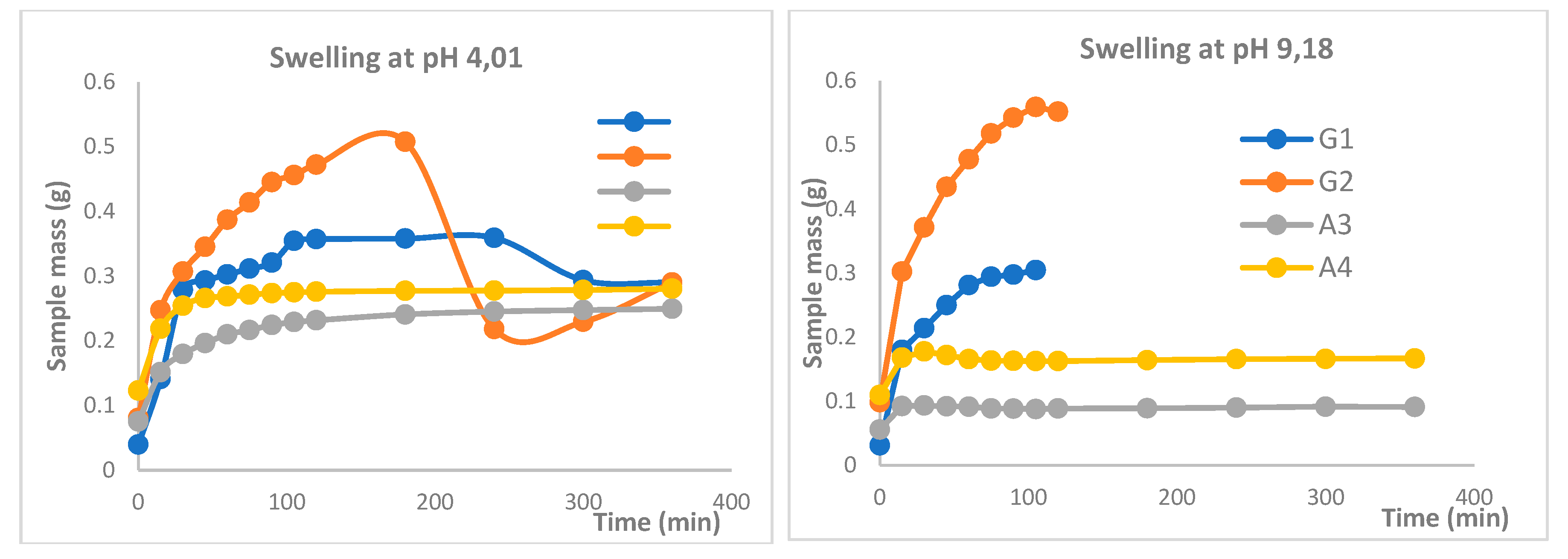

2.5. Swelling Study

The swelling behavior of polymer-crosslinked hydrogel patches was investigated to evaluate their pH sensitivity for topical applications. Swelling dynamics were examined in phosphate buffer solutions at pH 4.01 and 9.18. Initially, the dried hydrogel patches were weighed and then immersed in 250 mL of each buffer solution at room temperature for 72 hours. At predetermined time intervals, the patches were removed from the solutions, gently blotted with filter paper to remove surface moisture, and reweighed on an analytical balance. This procedure was repeated until the patches reached a constant weight, indicating equilibrium swelling [

26,

27].

The swelling coefficient (S) was calculated according to the following equation:

Wt – the mass of the sample after swelling during t,

Wo - the initial mass of the dry sample.

2.6. Sol–Gel Analysis

Sol–gel analysis was performed to determine the content of uncrosslinked components in the topical patches. The patches were first dried in an oven at 40 °C and weighed to obtain their initial dry mass. The dried patches were then immersed in 100 mL of distilled water for one week with occasional stirring to remove the soluble fraction. After one week, the patches were removed, carefully spread onto labeled Petri dishes, and redried in an oven at 40 °C until a constant mass was achieved [27-31]. The sol and gel fractions were calculated using the following equations:

where m

d – dry weight; m

s – wet weight.

2.7. UV–Vis Spectroscopy Analysis

The release of methylene blue from the hydrogel patches was evaluated using UV–Vis spectrophotometry (Agilent Cary 60 UV–Vis, Agilent Technologies, USA). Drug release studies were carried out in phosphate buffer solutions of different pH values to simulate physiological conditions. Samples were withdrawn at predetermined time intervals, and the absorbance of the solutions was recorded in 1 cm quartz cuvettes at the characteristic absorption maximum of methylene blue (λmax ≈ 660 nm). Calibration curves constructed from standard methylene blue solutions were used to determine the drug concentration in the release medium.

In parallel, the pH of the release medium was monitored using a calibrated pH meter equipped with a glass electrode to assess possible medium changes during the release process. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility, and the cumulative release of methylene blue was expressed as a percentage of the total drug load.

3. Results

Over the past two decades, transdermal drug delivery systems (TDDS) have been recognized as a reliable and versatile technology offering several advantages over conventional routes of administration. In contrast to oral or parenteral delivery, transdermal systems enable controlled and sustained release of therapeutic agents, improved patient compliance, and reduced fluctuations in plasma drug concentrations. Furthermore, the therapeutic effect can be easily discontinued by simply removing the patch, which provides an additional level of safety and dosing flexibility. These advantages have stimulated intensive research into the development of novel polymeric systems capable of overcoming the intrinsic limitations of the skin barrier.

In the present study, an attempt was made to design biodegradable transdermal patches based on natural polysaccharides. The selected polymers—gellan gum, chitosan, and agar-agar—were chosen due to their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and ability to form stable hydrogel matrices when subjected to chemical cross-linking. The incorporation of glutaraldehyde and divalent ions as cross-linking agents was intended to enhance the mechanical stability and durability of the prepared films.

Methylene blue was employed as a model drug owing to its distinct physicochemical properties and intense coloration, which allows for facile visual monitoring of its diffusion from the polymer matrix. In addition to serving as a tracer compound, methylene blue has been widely utilized in pharmaceutical studies as a representative hydrophilic molecule for assessing drug release kinetics. This makes it a suitable probe for evaluating both the swelling behavior and release characteristics of the developed hydrogel-based patches.

The physicochemical properties of the patches—including their morphology, thickness, folding resistance, swelling capacity, sol–gel ratio, and in vitro release profile—were systematically investigated. These results provide insight into the influence of polymer composition and cross-linking on the functional performance of the patches and highlight the potential of polysaccharide-based hydrogels as carriers for transdermal drug delivery.

Table 1.

Composition of formulations with different feed ratios.

Table 1.

Composition of formulations with different feed ratios.

| Samples |

Gellan gum, (g) |

Chitosan, (g) |

Agar, (g) |

Glutaraldehyde |

Methylene blue, (g) |

| G1 |

1 |

0.25 |

- |

2.5 |

- |

| G2 |

1 |

0.5 |

- |

2.5 |

- |

| A1 |

- |

0.25 |

1 |

2.5 |

- |

| A2 |

- |

0.5 |

1 |

2.5 |

- |

| GM |

1 |

0.25 |

- |

2.5 |

0.01 |

| AM |

- |

0.25 |

1 |

2.5 |

0.01 |

All hydrogel samples obtained in this study were subjected to additional ionic cross-linking using sodium and calcium salts in order to evaluate their cross-linking density and overall structural stability. This procedure was carried out after the initial chemical cross-linking with glutaraldehyde, since the incorporation of multivalent cations into the polysaccharide matrix is known to enhance gel rigidity and reduce solubility in aqueous media. The use of sodium and calcium ions also allowed us to assess the efficiency of ionic interactions with different types of polysaccharides and to compare the resulting differences in their physicochemical behavior.

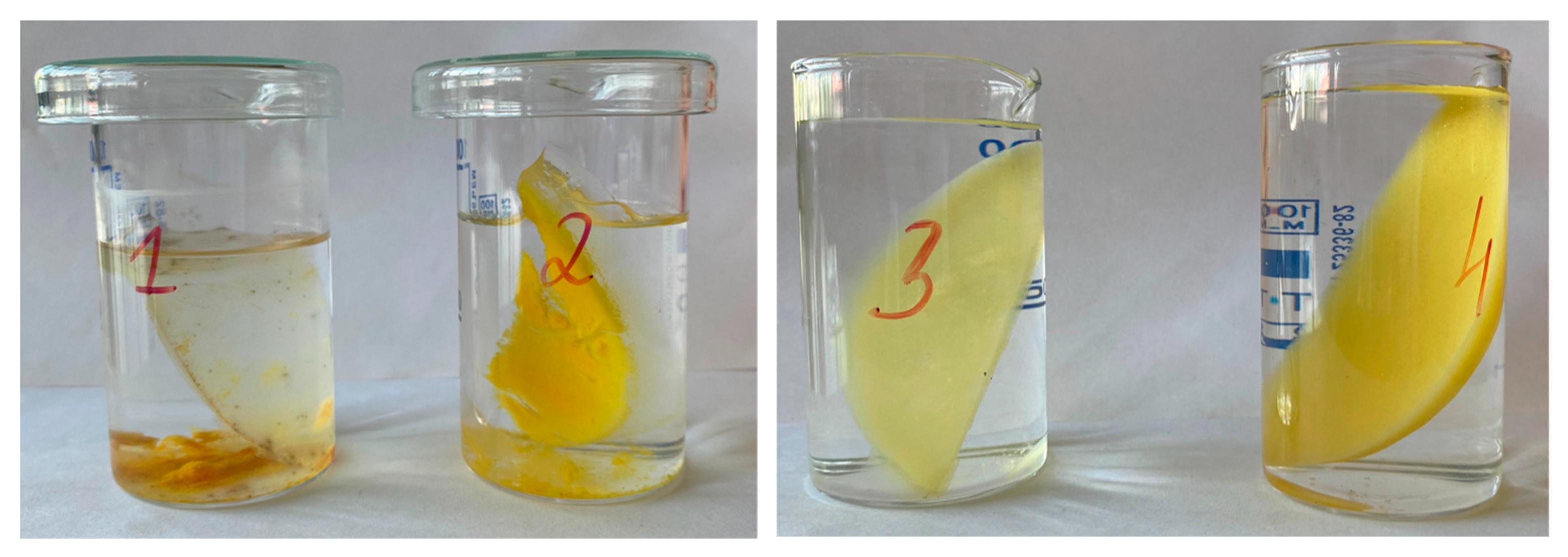

As a result, stable hydrogel discs were formed, which maintained their shape after washing and drying.

Figure 1 illustrates representative samples prepared under these conditions: (A) a hydrogel disc obtained from gellan gum, (B) a disc prepared from agar-agar, and (C) a gellan gum-based disc containing methylene blue as a model filler. The latter sample was selected not only to visualize the uniform distribution of the incorporated substance throughout the polymer matrix but also to facilitate subsequent analysis of release dynamics.

3.1. Weight change and thickness evaluation

The average thickness of the fabricated patches was determined using three randomly selected specimens from each composition. Each sample was weighed individually, after which its thickness was measured with a digital caliper at five different points (the four edges and the central region). The mean thickness values ranged from 0,15 to 0,25 mm, with an average patch weight between 5,5 and 6,5 g (

Table 2). The obtained results reflect the specific features of the preparation method: initially, the hot solution undergoes a transition from a thermally reversible random coil state to a more ordered double-helix conformation upon cooling, followed by the formation of a stable three-dimensional polymeric network through ion-induced cross-linking. Among the obtained materials, patches cross-linked with Ca²⁺ ions demonstrated superior structural stability and elasticity compared to those cross-linked with Na⁺ ions. This can be explained by the fact that monovalent sodium ions primarily reduce the electrostatic repulsion between carboxylate groups, whereas divalent calcium ions not only neutralize repulsion but also establish additional ionic bridges between polymer chains, thereby enhancing gel strength and integrity [

32,

33].

3.2. Bending resistance

The mechanical flexibility of the hydrogel patches was evaluated in terms of bending resistance. All samples exhibited satisfactory performance, confirming that the incorporation of different polysaccharide concentrations resulted in elastic, non-brittle structures. Flexural resistance was assessed manually by repeatedly folding each specimen until visible cracks or rupture occurred. The number of folding cycles sustained before failure varied depending on the polymer composition. Notably, the A2 formulation demonstrated the highest resistance, withstanding up to 70 consecutive folds without structural failure, indicating its enhanced mechanical robustness compared to the other tested systems (

Table 2).

3.3. Characterization of Transdermal Patches

In order to comprehensively evaluate transdermal patches, a series of physicochemical, mechanical, and biological tests are required. According to the recommendations of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), essential parameters include dissolution behavior, in vitro drug release, adhesive performance, and excipient compatibility [34-36]. In addition, a number of supporting analyses are necessary, such as the assessment of material interactions, patch thickness and weight uniformity, bending resistance, moisture content, moisture uptake, vapor permeability, drug loading, surface flatness, stability, swelling capacity, and potential for skin irritation. Together, these evaluations provide a comprehensive understanding of patch quality, stability, and suitability for therapeutic use.

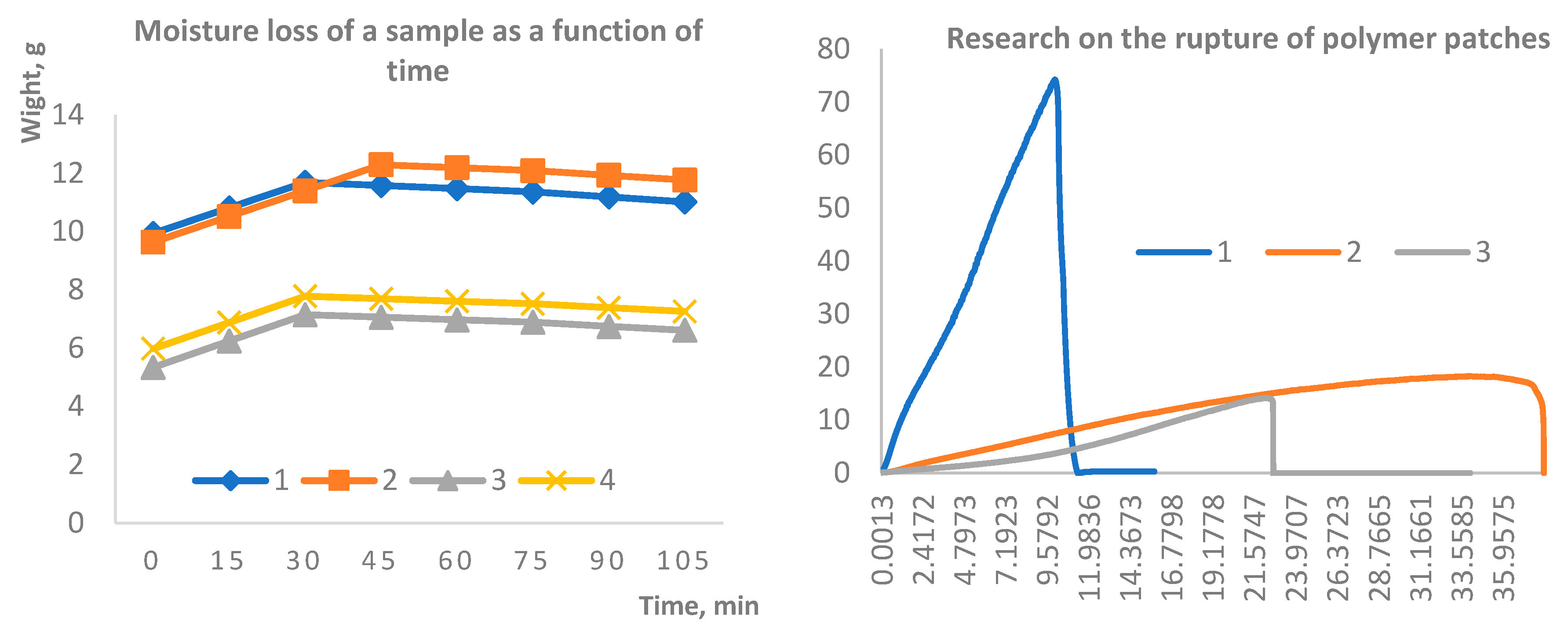

3.4. Weight loss evaluation

The weight loss of hydrogel-based patches was examined over two distinct time intervals. The first stage focused on the initial dehydration process, where weight reduction was measured during the first 1.5 hours of drying across all formulations. The second stage extended over several days, until the samples reached a constant weight, thereby reflecting their equilibrium water content. Following complete dehydration, the ability of the dried patches to recover their original dimensions upon rehydration was also assessed, providing insight into the structural resilience and reversibility of the hydrogel matrix.

Figure 2.

Kinetics of moisture loss in hydrogel samples over time (A); Mechanical performance of the patches evaluated by tensile strength testing (B).

Figure 2.

Kinetics of moisture loss in hydrogel samples over time (A); Mechanical performance of the patches evaluated by tensile strength testing (B).

It is well established that physically crosslinked gellan gum–based hydrogels exhibit limited stability under physiological conditions. This instability is primarily attributed to the exchange of divalent cations for monovalent ions, which can lead to rapid structural disintegration. Such behavior is particularly critical in the context of wound dressings, as the material is required to remain intact at least until the completion of the initial wound healing phase, typically lasting two to four weeks [

37,

38].

Therefore, the long-term stability of the synthesized samples was evaluated in aqueous media over a period of four months. Samples 1 and 2 underwent delamination within 3–4 days after immersion, persisting as separate layers throughout the remainder of the study. In contrast, samples 3 and 4 demonstrated remarkable structural integrity, maintaining stability over the entire experimental period (

Figure 3). Furthermore, sol–gel analysis revealed that the values for samples 3 and 4 prior to soaking were 1.4046 and 2.0308, respectively, whereas after 7 days of extraction of dried samples they decreased to 1.1096 and 1.6131. This indicates partial leaching of uncrosslinked fragments while confirming the preservation of a sufficiently stable network structure to ensure long-term stability.

Following the stability assessment, all samples were subjected to mechanical testing, with a particular focus on tensile strength. The results, presented in

Figure 4, indicate that the formulations containing agar-agar exhibited significantly greater durability compared to those based on gellan gum. These measurements were carried out using a Texture Analyzer (TA-3000, LabSol, China), providing quantitative evidence of the superior mechanical resilience of agar-agar cross-linked systems.

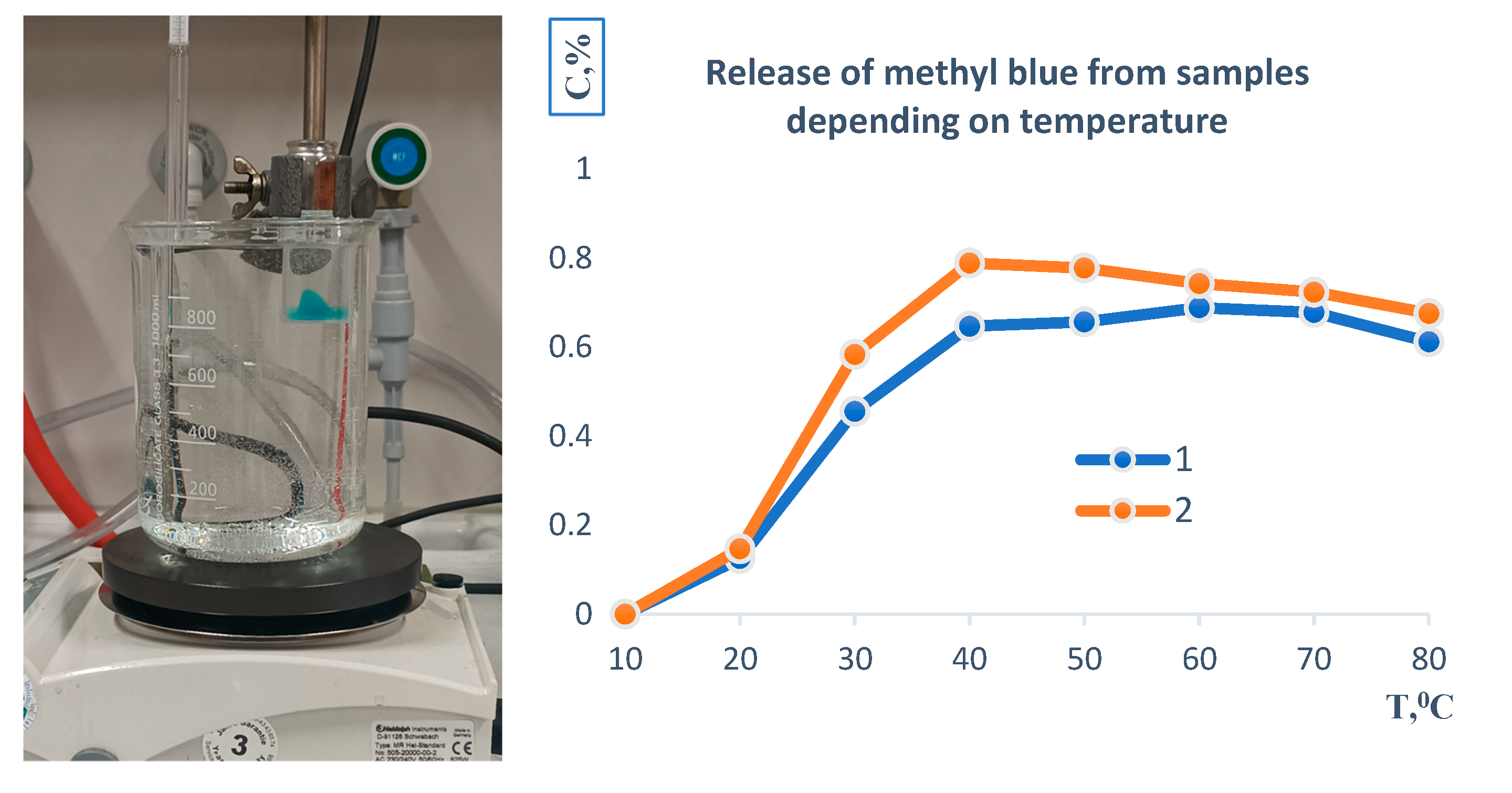

Figure 5 illustrates the temperature-dependent release profile of methylene blue from the polymer-based sample. Initially, the material was immersed in an aqueous medium at 20 °C, where a gradual release of the encapsulated compound was observed.

The release rate increased with rising temperature, reaching a maximum at approximately 39–40 °C, which corresponds to conditions close to physiological hyperthermia. Beyond this point, both formulations demonstrated a relatively uniform release pattern. At elevated temperatures of 80 °C, complete transfer of methylene blue into the aqueous phase was recorded. Moreover, under these conditions, the polymer matrix itself underwent full dissolution, indicating thermal instability of the carrier system

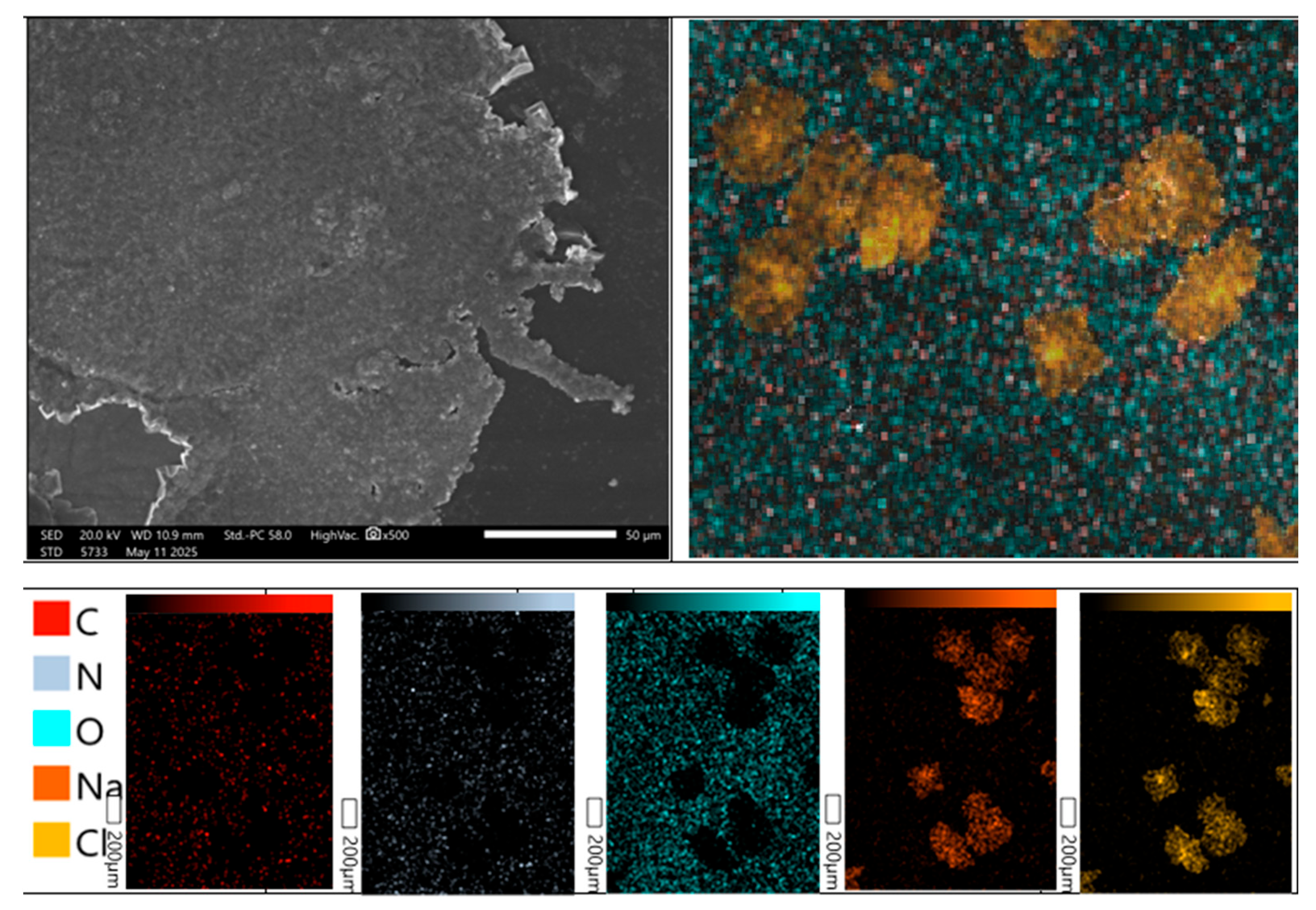

The surface morphology of the developed hydrogel patches was investigated using a high-resolution scanning electron microscope JSM-6390 (JEOL, Japan). The analyses were performed in high-vacuum mode with a secondary electron detector at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. Representative micrographs obtained at magnifications of 200×, 500×, and 1000× are presented in

Figure 6. The examined hydrogel patches exhibited a rough and porous surface architecture, as additionally confirmed by X-ray microanalysis. The presence of irregular cracks across the surface is attributed to partial disruption of the polymeric framework during the drying process. Such morphological features are expected to facilitate water penetration into the polymer network, thereby enhancing the hydration capacity of the material and contributing to moderate swelling behavior. Similar surface properties of polysaccharide-based hydrogels were reported by Bao et al. [

39], supporting the reproducibility of these structural characteristics.