Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

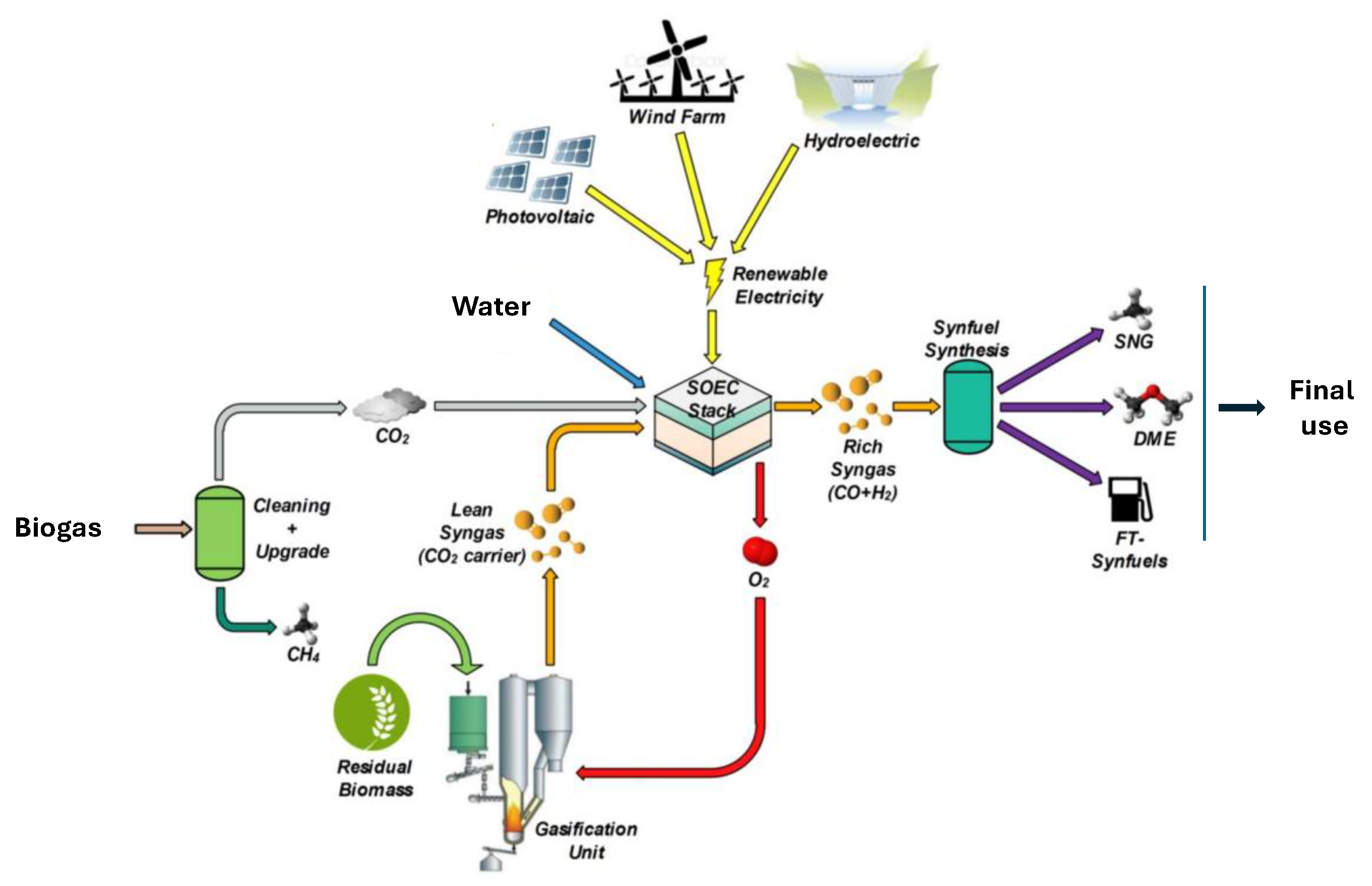

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: Contextualizing Hydrogen and Co-Electrolysis

2. Fundamentals and Energy Analysis of Co-Electrolysis of H2O and CO2

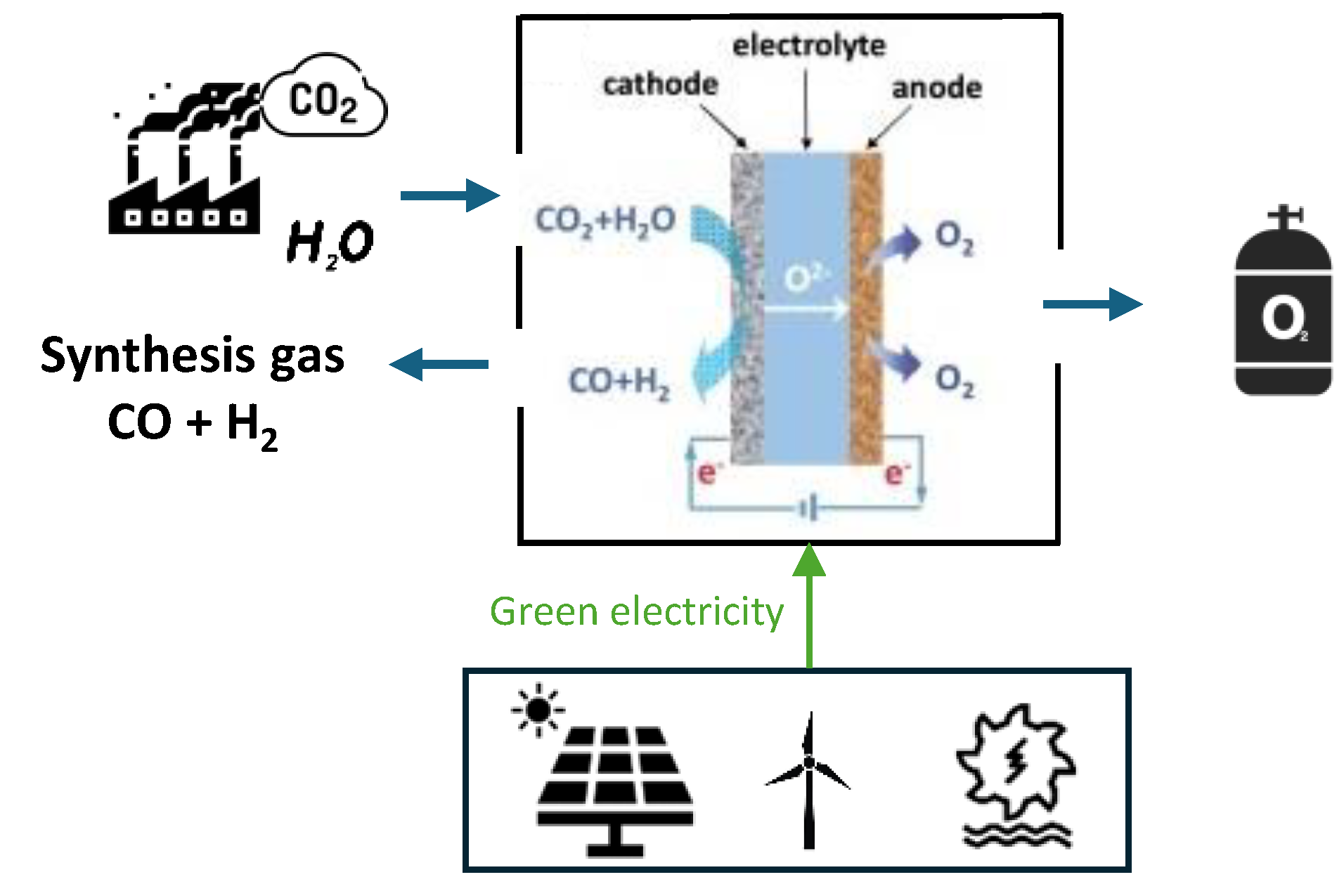

2.1. Operating Principles of Co-Electrolysis

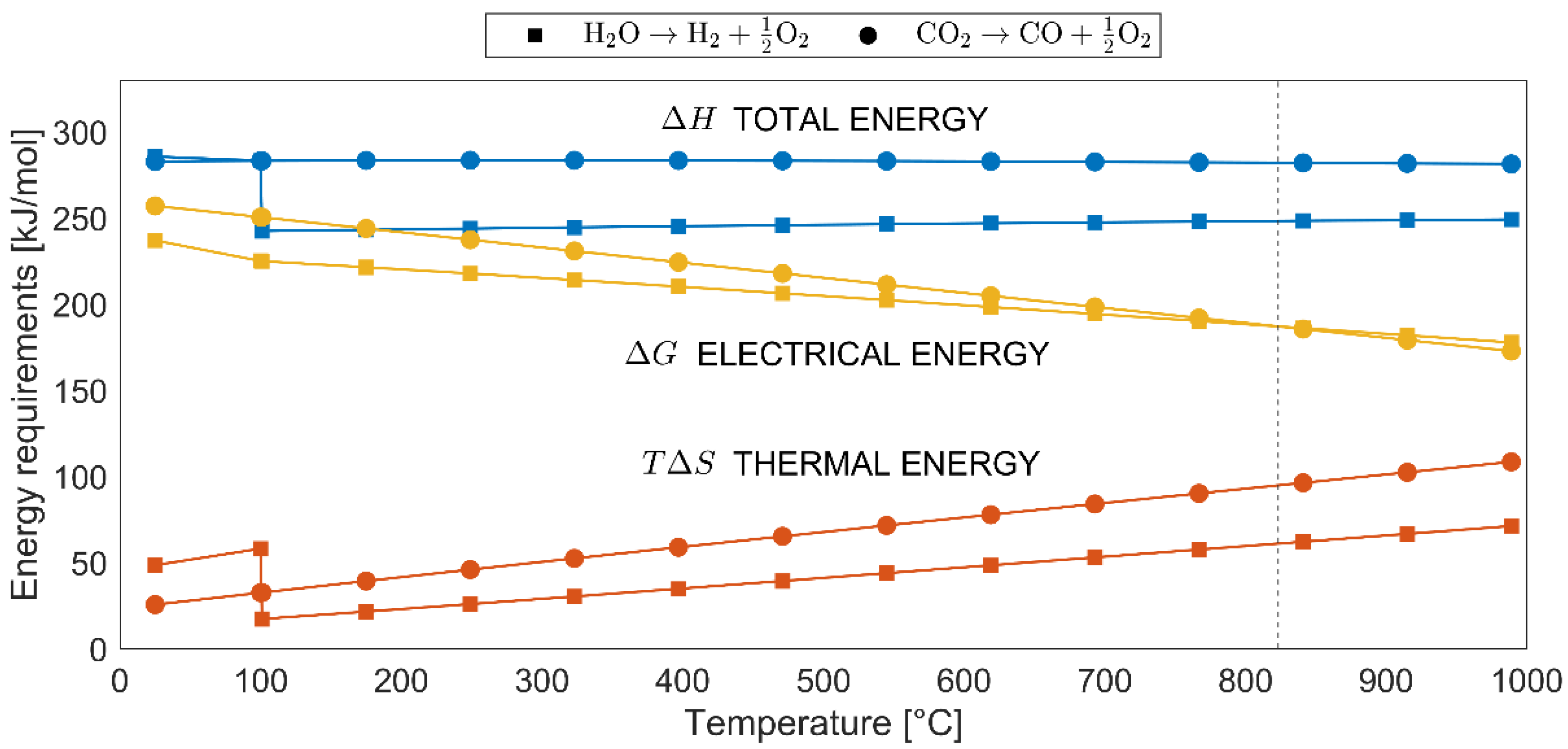

2.2. Energy Analysis of Co-Electrolysis

3. Outlook and Recent Developments of Co-Electrolysis of H2O and CO2

4. Potential Application of Co-Electrolysis in Specific Industrial Contexts

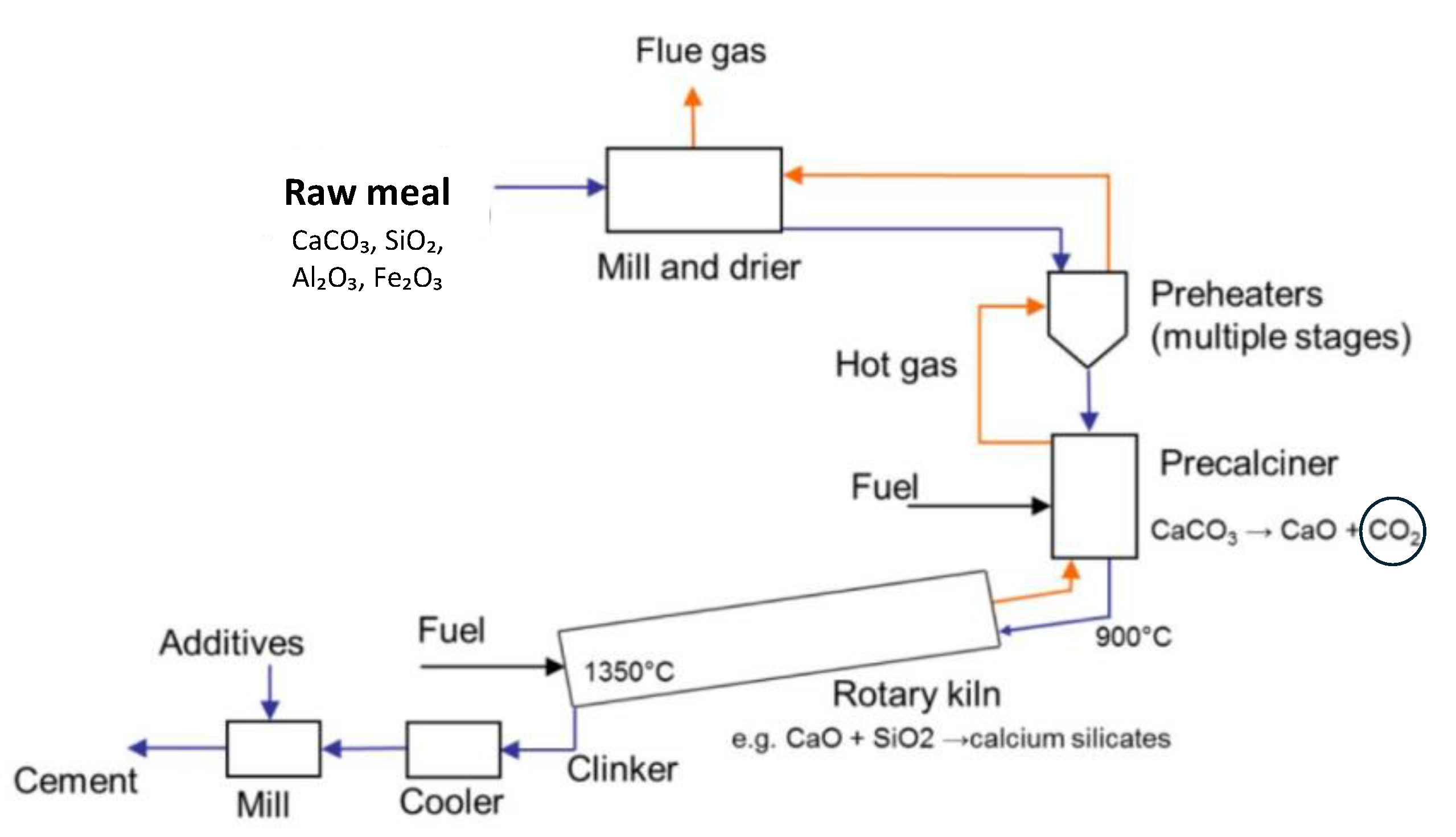

4.1. Cement Production

- −

- Calcination of Limestone: at high temperatures (approximately 900-1000°C), limestone (CaCO₃) undergoes a chemical reaction known as calcination. During this reaction, calcium carbonate decomposes into calcium oxide (CaO), also known as lime, and carbon dioxide (CO₂):

- −

- The CaO produced is solid and remains in the kiln, while the CO₂ is released into the atmosphere as a gas.

- −

- Clinker Formation: the CaO produced in the calcination step then reacts with other materials in the kiln, such as silica (SiO₂), alumina (Al₂O₃), and iron oxide (Fe₂O₃), at higher temperatures (around 1400-1450°C). These reactions result in the formation of clinker, a solid material that is ground into cement.

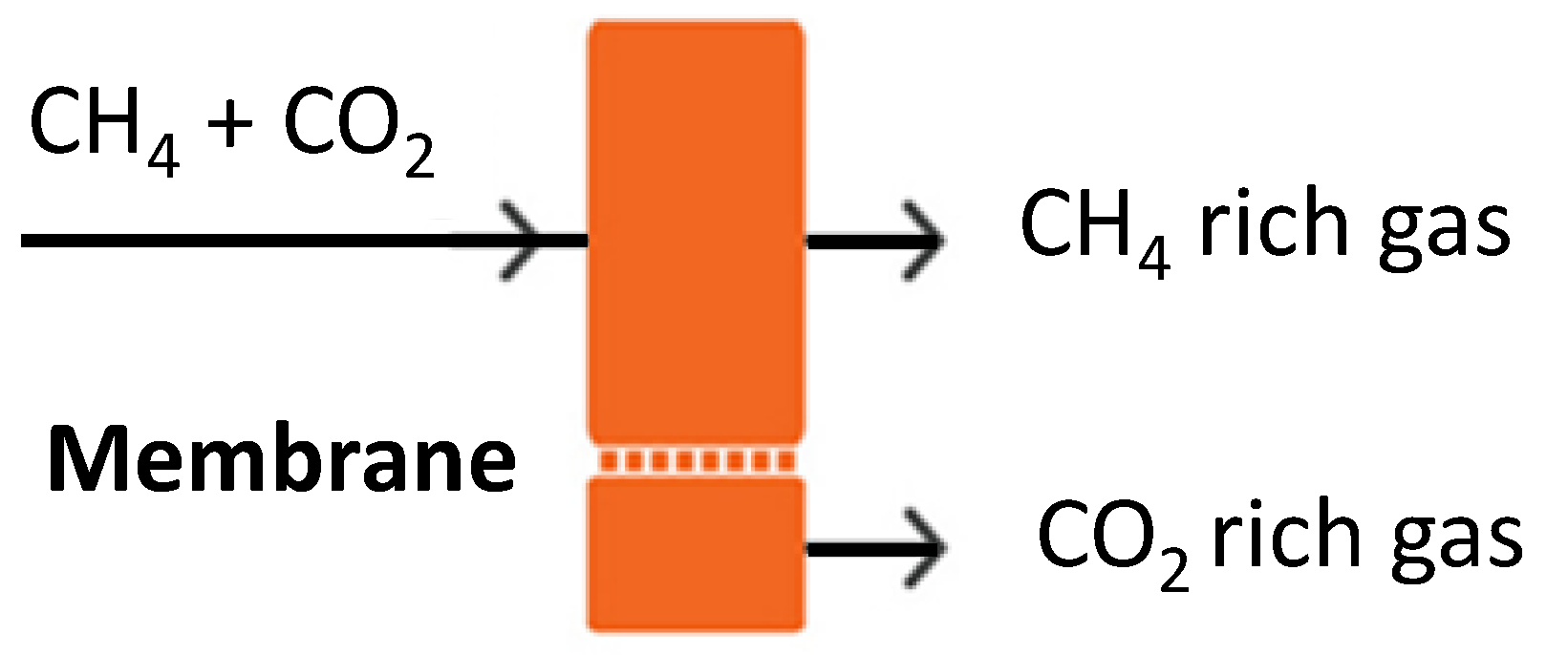

4.2. Natural Gas and Biogas Processing Facilities

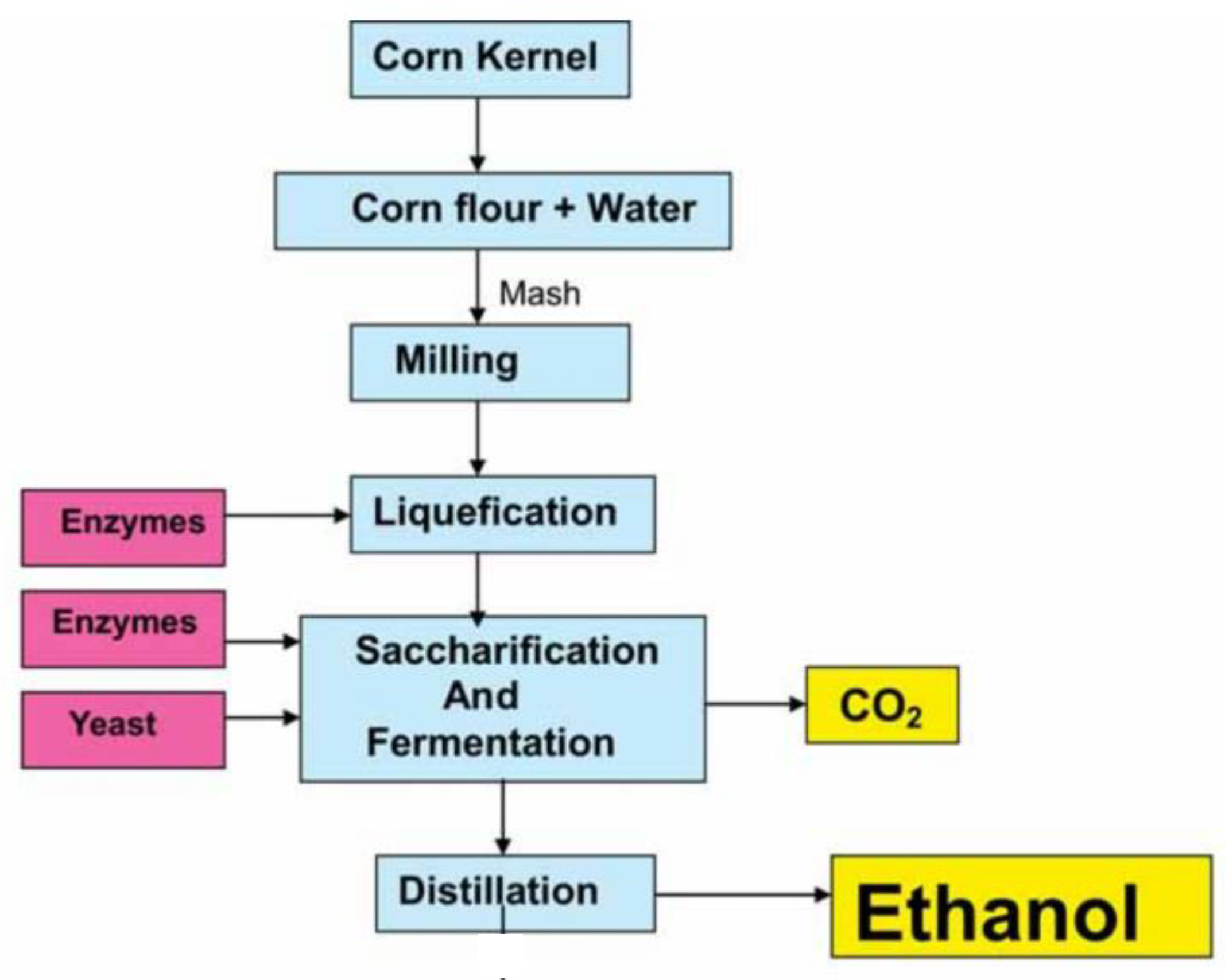

4.3. Carbon Dioxide Generation and Capture in Corn Fermentation for Bioethanol Production

- − Milling and Starch Preparation: The corn is ground to release starch, which is then broken down into fermentable sugars through enzymatic hydrolysis.

- − Liquefaction and Saccharification: Enzymes (such as amylase) convert starch into simple sugars like glucose and maltose.

- − Fermentation: Yeast: converts glucose into ethanol and CO₂:

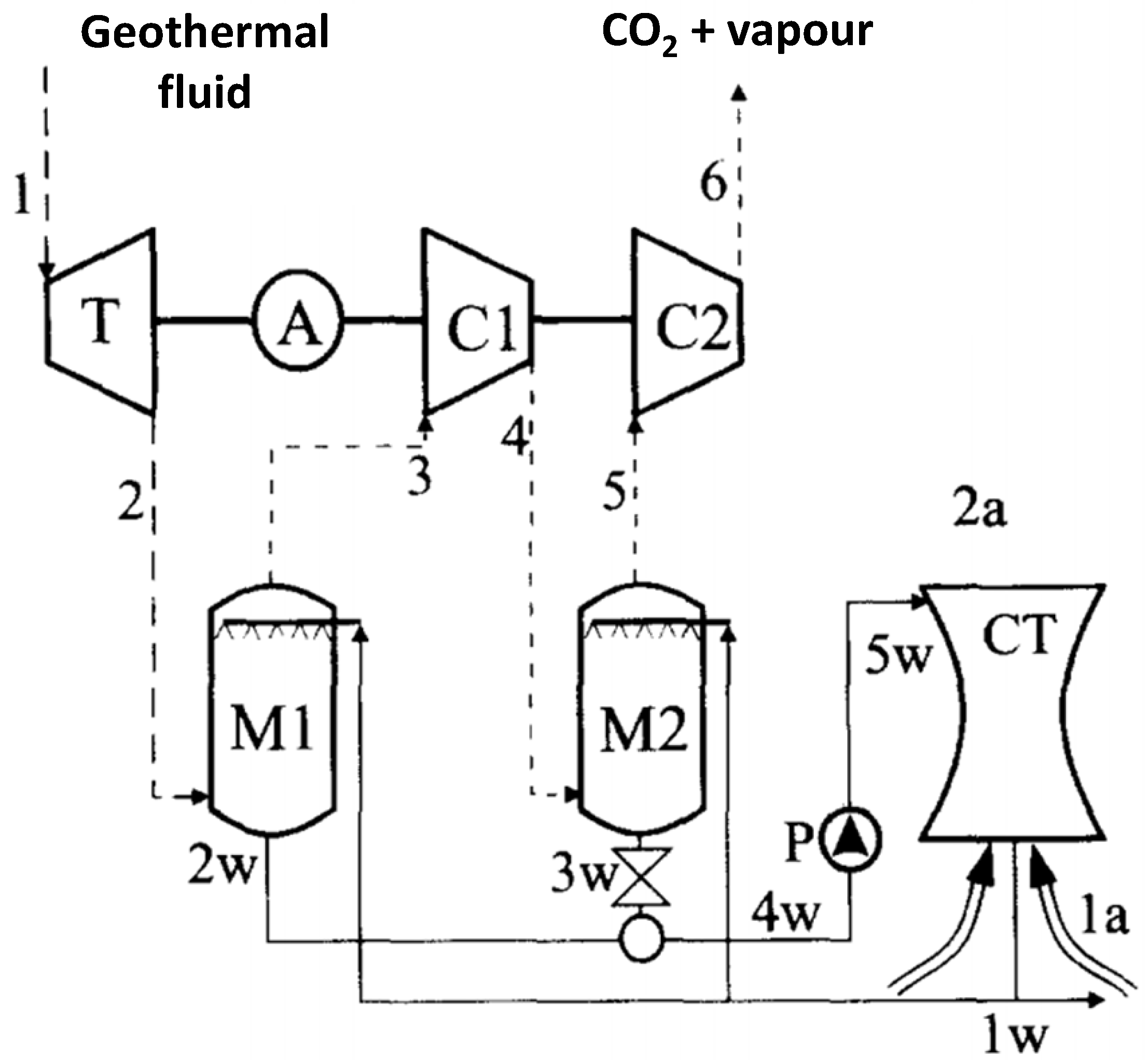

4.4. Co-Electrolysis of CO2 and H20 in the Power Sector: The Case of Geothermal Power Plants

5. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| AC | Alternate Current |

| act, a | Activation at anode |

| act, c | Activation at cathode |

| conc, a | Concentration at anode |

| conc, c | Concentration at cathode |

| DC | Direct Current |

| E | Ideal Potential [V] |

| F | Faraday's constant |

| I | Current [A] |

| LHV | Lower Heating Value [MJ/kg] |

| M | Mass flow rate [kg/s] |

| Ne | Number of “moles” of electrons |

| ohmic | Ohmic overpotential |

| P | Pressure [bar] |

| PEM | Proton Exchange Membrane |

| Q | Charge [Coulomb] |

| Q̇ | Thermal power [W] |

| SEC | Specific energy consumption [kWh/kg] |

| SOEC | Solid Oxide Electrolytic Cell |

| Syn | Syngas |

| T | Temperature |

| V | Potential [V] |

| Ẇ | Power [W] |

| X | Steam quality |

| ηact | Activation overpotential |

| h | Efficiency |

| DG | Gibbs free energy [kJ/kmol] |

| DH | Enthalpy of the reactions [kJ/kmol] |

References

- Hydrogen Council (2021). Hydrogen Council Report-Decarbonization Pathways: Hydrogen Council Report-Decarbonization Pathways Part 1: Life cycle Assessment Part 2: Supply Scenarios available. Available online: https://hydrogencouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Hydrogen-Council-Report_Decarbonization-Pathways_Part-1-Lifecycle-Assessment.pdf.

- Blank, T. K. , & Molly, P. (2020). Hydrogen’s decarbonization impact for industry. Near-term challenges and long-term potential. Report of the Rocky Mountain Institute. Available online: https://www.fuelcellpartnership.net/sites/default/files/Rocky_Mountain_Institute_hydrogen_insight_brief-1.pdf.

- Franco, A.; Giovannini, C. Routes for Hydrogen Introduction in the Industrial Hard-to-Abate Sectors for Promoting Energy Transition. Energies 2023, 16, 6098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C.; Treyer, K.; Antonini, C.; Bergerson, J.; Gazzani, M.; Gencer, E.; Gibbins, J.; Mazzotti, M.; McCoy, S.T.; McKenna, R.; et al. On the Climate Impacts of Blue Hydrogen Production. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2022, 6, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, R.W.; Jacobson, M.Z. How Green Is Blue Hydrogen? Energy Science & Engineering 2021, 9, 1676–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston Metal (2023). Zero CO2 Steel by Molten Oxide Electrolysis: A Path to 100% Global Steel Decarbonization. Available online: https://www.bostonmetal.com/news/zero-co2-steel-by-molten-oxide-electrolysis-a-path-to-100-global-steel-decarbonization/.

- Crownhart, C. (2022). How green steel made with electricity could clean up a dirty industry. Available online: https://www.technologyreview.com/</italic>2022/06/28/1055027/green-steel-electricity-boston-metal/.

- Graves, C.; Ebbesen, S.D.; Mogensen, M.; Lackner, K.S. Sustainable Hydrocarbon Fuels by Recycling CO 2 and H 2 O with Renewable or Nuclear Energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, S.; Zhao, X.; Jewell, L.L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Advances and Challenges with SOEC High Temperature Co-Electrolysis of CO2/H2O: Materials Development and Technological Design. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Giovannini, C. Recent and Future Advances in Water Electrolysis for Green Hydrogen Generation: Critical Analysis and Perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.H.; Larsen, P.H.; Mogensen, M. Hydrogen and Synthetic Fuel Production from Renewable Energy Sources. Inter-Natl. J. Hydrog. Energy 2007, 32, 3253–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsa, B.; Xia, L.; García De Arquer, F.P. CO2 Electrolysis Technologies: Bridging the Gap toward Scale-up and Commercial-ization. ACS Energy Lett. 2024, 9, 4293–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Overa, S.; Jiao, F. Emerging Electrochemical Processes to Decarbonize the Chemical Industry. JACS Au 2022, 2, 1054–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Quiroz-Arita, C.; Diaz, L.A.; Lister, T.E. Intensified Co-Electrolysis Process for Syngas Production from Captured CO2. Journal of CO2 Utilization 2021, 43, 101365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, G.; Choi, S.; Hong, J. A Review of Solid Oxide Steam-Electrolysis Cell Systems: Thermodynamics and Thermal Integration. Appl. Energy 2022, 328, 120145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupecki, J.; Motylinski, K.; Jagielski, S.; Wierzbicki, M.; Brouwer, J.; Naumovich, Y.; Skrzypkiewicz, M. Energy Analysis of a 10 kW-Class Power-to-Gas System Based on a Solid Oxide Electrolyzer (SOE). Energy Conversion and Management 2019, 199, 111934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbesen, S.D.; Graves, C.; Mogensen, M. Production of Synthetic Fuels by Co-Electrolysis of Steam and Carbon Dioxide. -Ternational J. Green Energy 2009, 6, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, G.; Bao, X. Co-Electrolysis of CO2 and H2O in High-Temperature Solid Oxide Electrolysis Cells: Recent Advance in Cathodes. J. Energy Chem. 2017, 26, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-W.; Kim, H.; Yoon, K.J.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, B.-K.; Choi, W.; Lee, J.-H.; Hong, J. Reactions and Mass Transport in High Temperature Co-Electrolysis of Steam/CO2 Mixtures for Syngas Production. J. Power Sources 2015, 280, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, D.J.; Gunduz, S.; Fitzgerald, T.; Miller, J.T.; Co, A.C.; Ozkan, U.S. Production of Syngas with Controllable H2/CO Ratio by High Temperature Co-Electrolysis of CO2 and H2O over Ni and Co- Doped Lanthanum Strontium Ferrite Perovskite Cathodes. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2019, 248, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L.; Duan, C.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Hou, Y.; Peng, J.; Song, X.; An, S.; O’Hayre, R. An All-Oxide Electrolysis Cells for Syngas Production with Tunable H2/CO Yield via Co-Electrolysis of H2O and CO2. Journal of Power Sources 2021, 482, 228887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimpiri, N.; Konstantinidou, A.; Tsiplakides, D.; Balomenou, S.; Papazisi, K.M. Effect of Steam to Carbon Dioxide Ratio on the Performance of a Solid Oxide Cell for H2O/CO2 Co-Electrolysis. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, G.; Discepoli, G.; Bidini, G.; Lanzini, A.; Santarelli, M. Co-Electrolysis of Water and CO2 in a Solid Oxide Electrolyzer (SOE) Stack: Study of High-Temperature Co-Electrolysis Reactions in SOEC. Int. J. Energy Res. 2016, 40, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhu, J.; Han, M.; Hua, X.; Li, D.; Ni, M. The Development of Solid Oxide Co-Electrolysis of H2 O and CO2 on Large-Size Cells and Stacks. iEnergy 2023, 2, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Q.; Pan, Z.; Chan, S.H. High-Temperature Electrolysis of Simulated Flue Gas in Solid Oxide Electrolysis Cells. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 280, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastián, D., Palella, A., Siracusano, S., Lo Vecchio, C., Monforte, G., Baglio, V., Spadaro, L., & Aricò, A. S. (2016). Development of an electrochemical co-electrolysis system for CO₂ and H₂O with a polymer electrolyte operating at low temperature for CO₂ reduction (CO2CHEM) - R.E. 45/16. CNR-ITAE. Available online: https://publications.cnr.it/doc/359565.

- Franco, A.; Diaz, A.R. Environmental Sustainability of CO2 Capture in Fossil Fuel Based Power Plants. In Proceedings of the Ecosytems and Sustainable Development VI; Vol. I; WIT Press: Coimbra, Portugal, August 17, 2007; pp. 251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y. , Luo, L., Liu, T., Hao, L., Li, Y., Liu, P., & Zhu, T. (2024). A review of low-carbon technologies and projects for the global cement industry. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 136, 682-697.

- Volaity, S. S. , Aylas-Paredes, B. K., Han, T., Huang, J., Sridhar, S., Sant, G.,... & Neithalath, N. (2025). Towards decarbonization of cement industry: a critical review of electrification technologies for sustainable cement production. npj Materials Sustainability, 3(1), 23.

- Bahadori, A. Natural Gas Processing: Technology and Engineering Design; Elsevier: Amsterdam ; Boston, 2014; ISBN 978-0-08-099971-5.

- Joyia, M. A. K., Ahmad, M., Chen, Y. F., Mustaqeem, M., Ali, A., Abbas, A., & Gondal, M. A. (2024). Trends and advances in sustainable bioethanol production technologies from first to fourth generation: a critical review. Energy Conversion and Management, 321, 119037.

- Frondini, F.; Caliro, S.; Cardellini, C.; Chiodini, G.; Morgantini, N. Carbon Dioxide Degassing and Thermal Energy Release in the Monte Amiata Volcanic-Geothermal Area (Italy). Appl. Geochem. 2009, 24, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taussi, M.; Nisi, B.; Brogi, A.; Liotta, D.; Zucchi, M.; Venturi, S.; Cabassi, J.; Boschi, G.; Ciliberti, M.; Vaselli, O. Deep Regional Fluid Pathways in an Extensional Setting: The Role of Transfer Zones in the Hot and Cold Degassing Areas of the Larderello Geo-thermal System (Northern Apennines, Italy). Geochem Geophys Geosyst 2023, 24, e2022GC010838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridriksson, T.; Merino, A.M.; Yasemin Orucu, A.; Audinet, P. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Geothermal Power Production. In Proceedings of the PROCEEDINGS, 42nd Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering Stanford University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ármannsson, H.; Fridriksson, T.; Wiese, F.; Hernandez, P.; Pérez, N.M. CO2 Budget of the Krafla Geothermal System, NE-Iceland. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg, S.; Werner, C.; Rissmann, C.; Mazot, A.; Horton, T.; Gravley, D.; Kennedy, B.; Oze, C. Soil CO2 Emissions as a Proxy for Heat and Mass Flow Assessment, T Aupō V Olcanic Z One, N Ew Z Ealand. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 2014, 15, 4885–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasco, R.D.; Lales, J.S.; Arnuevo, Ma.T.; Guillermo, I.Q.; De Jesus, A.C.; Medrano, R.; Bajar, O.F.; Mendoza, C.V. Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Storage and Sequestration of Land Cover in the Leyte Geothermal Reservation. Renew. Energy 2002, 25, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettagli, N.; Bidini, G. Larderello-Farinello-Valle Secolo Geothermal Area: Exergy Analysis of the Transportation Network and of the Electric Power Plants. Geothermics 1996, 25, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical species | Molar mass (g/mol) |

Moles [mol/s] |

Mass flow rate [kg/s] |

LHV [kJ/mol] |

LHV [MJ/kg] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | 18.02 | 22.73 | 0.41 | ||

| CO2 | 44.01 | 22.73 | 1 | ||

| CO | 28.01 | 22.73 | 0.637 | 283.0 | 10.1 |

| H2 | 2.02 | 22.73 | 0.046 | 241.8 | 120 |

| Number of electrons [mol/s] |

Total charge [C/s] |

Minimum cell potential, E [V] |

P = Q x E [kW] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90.92 | 8.76 × 10⁶ | 1.46 | 12680.9 |

| Parameter | Water Electrolysis (H₂O → H₂ + ½O₂) |

Co-electrolysis (CO₂ + H₂O → CO + H₂) |

|---|---|---|

| Reactants required | ~9 kg H₂O | ~9 kg H₂O + ~22 kg CO₂ |

| Overall reaction | H₂O → H₂ + ½O₂ | CO₂ + H₂O → CO + H₂+ O₂ |

| Technology used | PEM / Alkaline / SOEC | SOEC |

| Operating temperature | 60–80 °C (ALK, PEM); 700–850 °C (SOEC) |

700–850 °C |

| ΔG° | ~ 237 kJ/mol H₂ | ~ 257 kJ/mol H₂ |

| Minimum energy required | 39,6 kWh/kg H₂ | 42,7 kWh/kg H₂ |

| Electrical energy input | 55-60 kWh/kg H₂ | 79–84 kWh/kg H₂ |

| Thermal energy input (net) | ~0–1 kWh/kg H₂ | ~5–10 kWh/kg H₂ |

| Total energy required | ~55–61 kWh/kg H₂ | ~84–94 kWh/kg H₂ |

| Main product gas | H₂ | Syngas (H₂ + CO) |

| CO₂ processed per kg of H₂ | None | ~22 kg |

| Efficiency (on LHV basis) | ~60–70% | ~45–50% |

| Efficiency of co-electrolysis | Electricity required [kWh] |

Energy required for water vaporization | H2 mass flow rate [kg/h] |

CO mass flow rate [kg/h] |

H2 energy content [kWh] |

CO energy content [kWh] |

SEC for hydrogen prod. [kWh/kg] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70% | 9100 | 3790 | 165,6 | 2293.2 | 5520 | 6435.7 | 77.8 |

| 50% | 12800 | 3790 | 165,6 | 2293.2 | 5520 | 6435.7 | 100.2 |

| 30% | 21330 | 3790 | 165,6 | 2293.2 | 5520 | 6435.7 | 151.7 |

| Operating Temperature [°C] |

Estimated perspective efficiency [%] |

|---|---|

| 50-80 | 20–30 |

| 200 | 30–40 |

| 400 | 40–50 |

| 600 | 50–60 |

| 800 | 60–70 |

| Factor | High-Temperature Co-Electrolysis |

Low-Temperature Co-Electrolysis |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Requirement | Lower electrical input, as heat provides part of the required energy. |

Higher electrical input needed, increasing energy consumption. |

| Reaction Kinetics | Faster reaction rates, improving efficiency. | Slower reaction rates, making the process inefficient. |

| Electrolyte Conductivity | Solid oxide electrolytes (e.g., YSZ) conduct oxygen ions efficiently. |

Poor ion conductivity at low temperatures, leads to high resistance. |

| Water Phase | Operates with steam, which enhances reaction efficiency. | Requires additional energy to convert liquid water into steam. |

| Overall Efficiency | Higher efficiency due to improved kinetics and lower electrical losses. | Lower efficiency, high losses, and impractical operation. |

| Cost Reduction | High manufacturing and operational costs | Possible use of low-cost materials |

| Research Area | Key Challenges | Potential Solutions & Directions |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials & Catalysts |

Stability, efficiency, and resistance to degradation | Advanced perovskite oxides, transition metal doping, nanostructured catalysts |

| Electrochemical Performance |

Faradaic efficiency, current density, and reaction kinetics | Optimized doping, interface engineering, enhanced electrode architecture |

| Temperature Optimization |

High operating temperatures (700–900°C) increase thermal energy quality demand and material stress and thermal control | Exploring lower-temperature SOECs, hybrid approaches integrating PEM technology |

| H₂/CO Ratio Control |

Precise tuning for downstream applications (e.g., Fischer-Tropsch synthesis) | Adjusting feed gas composition, operating voltage, and catalyst properties |

| System Scalability |

Transitioning from laboratory-scale to industrial-scale applications | Modular SOEC stacks, integration with renewable energy sources |

| Durability & Degradation |

Long-term stability, anode/electrolyte interface degradation | Improved material selection, protective coatings, optimized operational strategies |

| Integration with Industrial Processes |

Compatibility with processes in which CO2 separation is required and sizing problem | Direct syngas utilization, coupling with carbon capture and utilization (CCU) technologies |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Annual Cement Production | 1,000,000 tons/year |

| Daily Production | 1,000,000 tons ÷ 365 days = 2740 tons/day |

| Hourly Production | 2,740 tons ÷ 24 h = 114.17 tons/h |

| CO₂ Emissions from Calcination | 0.68 × 114.17 tons = 77.76 tons CO₂/hour |

| Annual CO₂ Emissions | 77.76 tons/hour × 24 h × 365 days = 681,000 tons CO₂/year |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Natural gas treated (per day) | 2,000,000 m³ |

| Initial CO₂ content (6% of total) | 120,000 m³ |

| CO₂ separation efficiency | 85% |

| CO₂ separated (per day) | 102,000 m³ |

| CO₂ residual (in treated gas) | 18,000 m³ |

| CO₂ separated (per year) | 37,230,000 m³ (approx. 37.23 million m³) |

| CO₂ separated (mass per day) | 102,000 m³ × 1.977 kg/m³ = 201,654 kg (201.65 tons) |

| CO₂ residual (mass per day) | 18,000 m³ × 1.977 kg/m³ = 35,346 kg (35.35 tons) |

| Geothermal Field | CO₂ Concentration (wt%) | CO₂ Emissions (kg/MWh) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monte Amiata (Italy) | ~5-8% | 250-520 | [32] |

| Larderello (Italy) | ~1-5% | Lower than Monte Amiata | [33] |

| The Geysers (USA) | ~0.5-2% | ~40-100 | [34] |

| Krafla (Iceland) | ~0.5-1.5% | ~10-50 | [35] |

| Taupo Volcanic Zone (NZ) | ~2-6% | ~100-300 | [36] |

| Philippines Fields | ~1-4% | ~50-200 | [37] |

| Point | m [kg/s] |

P [bar] |

T [°C] |

x CO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 111.11 | 5.00 | 195 | 5.0 |

| 2 | 111.11 | 0.08 | 41 | 5.0 |

| 3 | 7.65 | 0.07 | 26 | 72.6 |

| 4 | 7.65 | 0.272 | 177 | 72.6 |

| 5 | 6.10 | 0.260 | 33 | 91.1 |

| 6 | 6.10 | 1.013 | 176 | 91.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).