1. Introduction

Polyaniline (PANi) is one of the most promising π-conjugated conductive polymers because of its re markable attributes, such as enhanced conductivity, robust environmental stability, ease of doping, and conductivity control, and a wide array of color changes corresponding to various oxidation levels [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. PANi, known for its ability to dynamically and reversibly respond to environmental and external stimuli, has recently garnered significant attention. Moreover, its practical applications across various fields—including chemical sensors, optoelectronic devices, anticorrosion systems, and energy conversion technologies such as batteries and supercapacitors—have further elevated its prominence [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. In particular, PANi-based electrochemical sensors have garnered considerable attention as highly promising materials for gas detection due to their dynamic resistance modulation when exposed to reducing or oxidizing harmful gases. Through chemical doping, charge carriers are introduced into the π-conjugated polymer backbone, influencing electrical conductivity. For instance, when a positively charged, doped PANi-based sensor is exposed to an oxidizing gas, its resistance increases in direct proportion to the concentration of the adsorbed gas. Conversely, upon adsorption of reducing components such as ammonia, the resistance also exhibits a measurable increase. Furthermore, PANi demonstrates intrinsic redox activity, as it facilitates the addition or removal of electrons within its π-conjugated polymer backbone through doping or de-doping processes involving dopants or oxidizing/reducing gaseous species. Regardless, PANi has been widely regarded as a highly promising material for chemical sensing applications, particularly in the detection of various organic gases such as ammonia (NH

3), acetone (C

3H

6O), carbon dioxide (CO

2), hydrogen (H

2), and gaseous H

2O [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Its electrical resistance undergoes significant modulation upon exposure to acidic or basic hazardous gases, making it an exceptionally responsive and adaptable sensing medium. PANi-based sensors possess several advantageous properties for gas detection, as demonstrated by numerous studies [

15,

16]. Nevertheless, overcoming several key challenges is essential to attaining the performance standards necessary for their effective deployment in real-world applications. Firstly, the sensor must demonstrate stable and efficient operation at ambient or low temperatures, ensuring precise detection of target gas species while minimizing cross-sensitivity to interfering compounds. Secondly, the advancement of sensing materials with exceptional resilience to humidity fluctuations is paramount to sustaining long-term operational reliability and accuracy. Thirdly, the sensor should exhibit superior selectivity for specific gaseous constituents, achieving highly sensitive detection capabilities even at concentrations as low as 1 ppm.

Many studies have been conducted on materials capable of achieving high sensitivity while ensuring moisture stability and maintaining detection at room temperature [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Zhang et al. [

20] developed an acetone sensor using a ZnO/S-N graphite QD/PANi composite and reported a gas sensor capable of detecting 500 ppb at room temperature. Similarly, our research group previously developed an acetone gas sensor based on PANi nanoparticles (NPs) as part of an earlier study. However, the sensor has the challenge of achieving stable performance under variations in temperature, humidity, and repeated cycle evaluations [

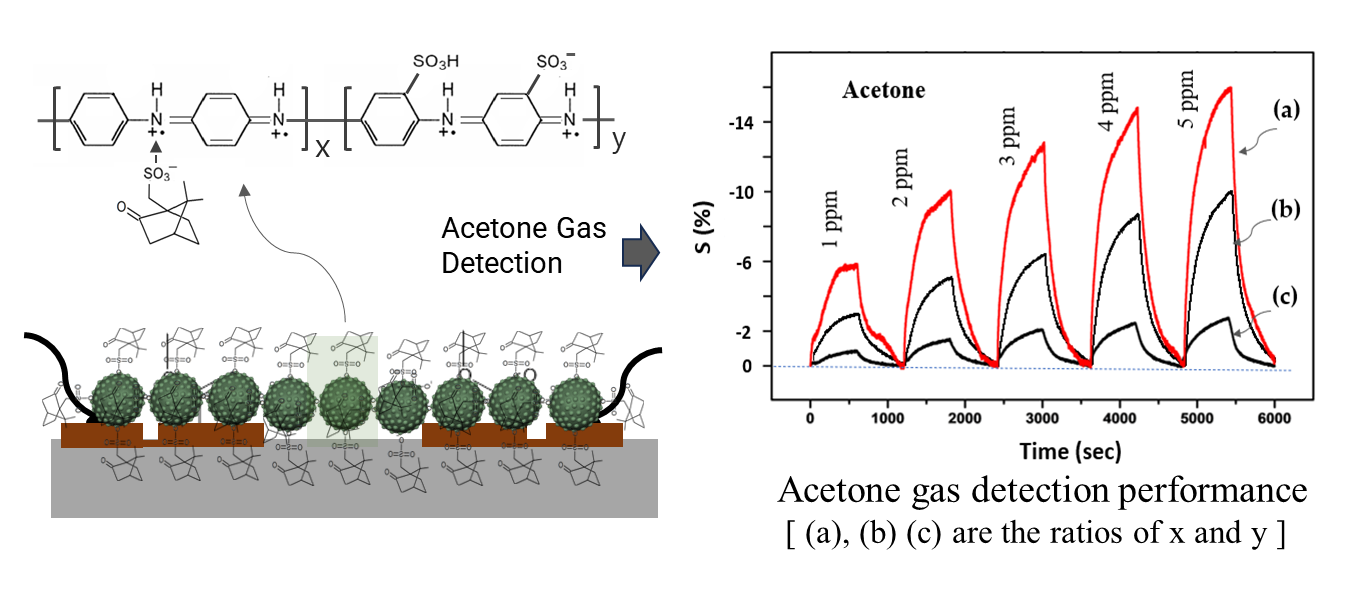

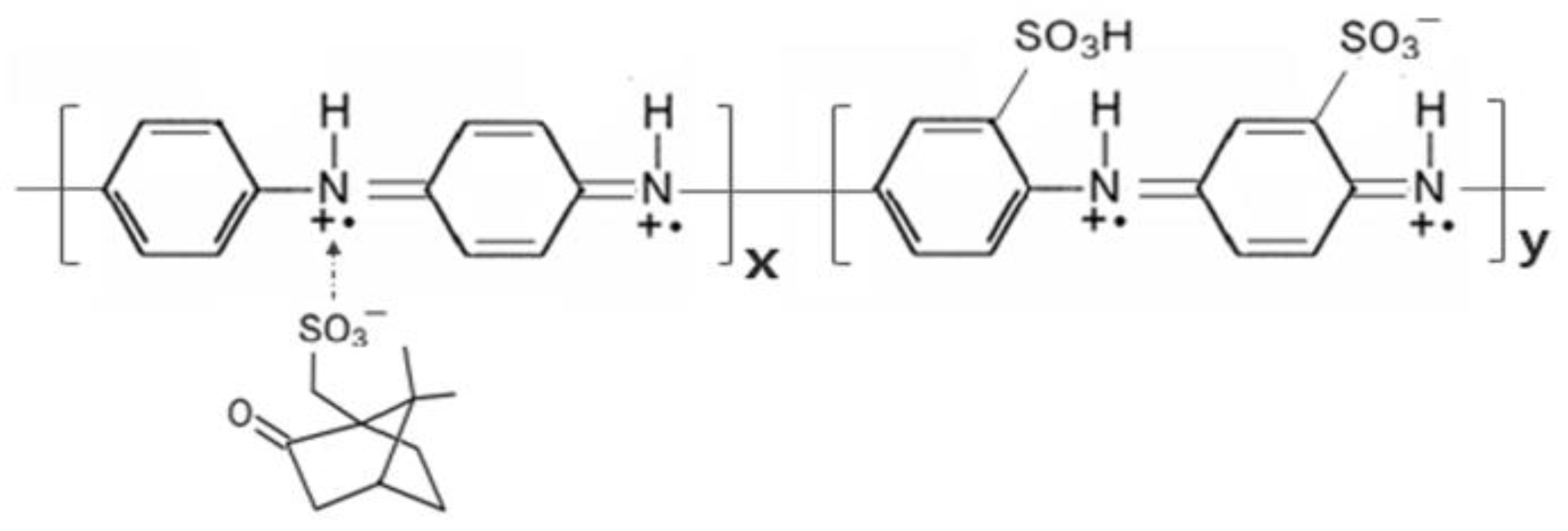

21]. To mitigate the aforementioned challenges, we designed spherical nanoparticles (NPs) composed of poly (aniline-co-aniline-2-sulfonic acid), capped with camphorsulfonic acid (CSA), herein referred to as CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi), as shown in

Figure 1. These engineered NPs have been specifically tailored for acetone gas sensing applications, ensuring enhanced sensitivity and selectivity. Structurally, it is a copolymer in which aniline monomer (ANi) and aniline-2-sulfonic acid monomer (ASNi) are used in equimolar amounts with a sulfonic acid (-SO

3H) group substituted at the 2-carbon position, and CSA is acted not only as a capping agent but also as a dopant. Specifically, PANi substituted with an -SO

3H group is expressed as poly(aniline-2-sulfonic) (PASNi).

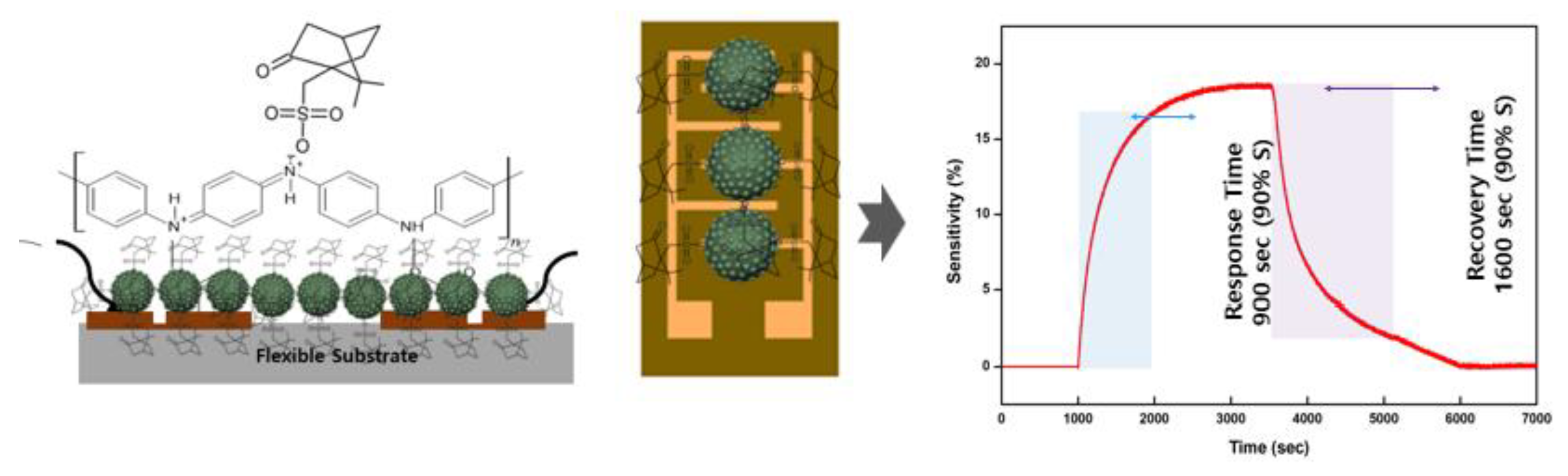

In this study, we synthesized emeraldine salts of CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) in the form of core-shell shaped spherical NPs, specifically designed as sensing elements for acetone gas and gaseous H2O (water vapor) detection. These engineered nanostructures aim to enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and stability in gas-sensing applications. Specifically, PANi substituted with an -SO3H group is expressed as poly(aniline-2-sulfonic) (PASNi). Here, the substituent -SO3H acts as a dopant, forming a self-doped conductive polymer. The -SO3H substituent directly donates electrons to the conjugated polymer chain, creating charged carriers and imparting conductivity. CSA with hydrophobic properties is positioned on the surface of P(ANi-co-ASNi) NPs. This configuration not only helps maintain a stable electrical resistance but can also minimize resistance changes due to humidity. Consequently, the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) NPs were capable of reliably detecting acetone gas and H2O vapor at concentrations of 1 ppm and 1% relative humidity (RH), respectively, at room temperature.

3. Results and Discussion

The overall synthesis procedure for CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) spherical NPs, using micelle polymerization with the HPMC surfactant in an aqueous solution, is depicted in

Scheme 1. As shown in

Scheme 1, the process began with dissolving HPMC, a surfactant essential for micelle formation, in DI water to prepare an aqueous solution. Subsequently, ANi and ASNi, substituted with a sulfonic acid (-SO

3H) group at the 2-carbon position, were added in equal molar amounts to the solution, and HCl was introduced into the previously prepared solution. During this step, the co-monomer comprising ANi and ASNi was protonated into positively charged anilinium ions (-NH

3+) via HCl. In succession, the polymerization of the co-monomer was triggered by the addition of APS, as an oxidizing agent. Afterwards, the impure ion products were neutralized and eliminated using NaOH solution, resulting in the spherical NPs of blue-colored emeraldine base structure. Finally, CSA was used for re-doping, resulting in a green-colored emeraldine salts structure-based electrically conductive NPs, as showed in the

Scheme 1. As depicted in the

Scheme 1, this process yielded green P(ANi-co-ASNi) spherical NPs capped with CSA. Here, the spherical NPs exhibited an average diameter of 265 nm, with the hydrophobic CSA chemically bonded to the outer surface of the positively charged P(ANi-co-ASNi) spherical NPs. In this context, the CSA capping agent, featuring an -SO

3H functional group, promotes stable charge transfer properties within the P(ANi-co-ASNi) polymer chains while enhancing the resistance of the structure to external moisture. In addition, the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) NPs exhibit the properties of p-type semiconductors, which are characterized by positively charged chain structures. The NH⁺ functional group within the P(ANi-co-ASNi) polymer chain can form weak hydrogen bonds with C=O or H⁺/OH via charge-charge interactions when acetone or H₂O molecules are adsorbed. This means that when the C=O group of acetone molecule is adsorbed, the positive charge density within the backbone of P(ANi-co-ASNi) decreases, thereby increasing the electrical resistance. Conversely, upon adsorption of H₂O molecules, the positive charge density along the P(ANi-co-ASNi) backbone increases. When H₂O acts as a charge acceptor, this interaction further reduces the net positive charge, resulting in decreased electrical resistance. Previous studies have reported on the reaction mechanisms between PANi-based materials and various organic gases [

22,

23]. Moreover, the spherical morphology of CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) particles provides a high surface-to-volume ratio, which significantly enhances the interaction between the polymer chains and gaseous analytes.

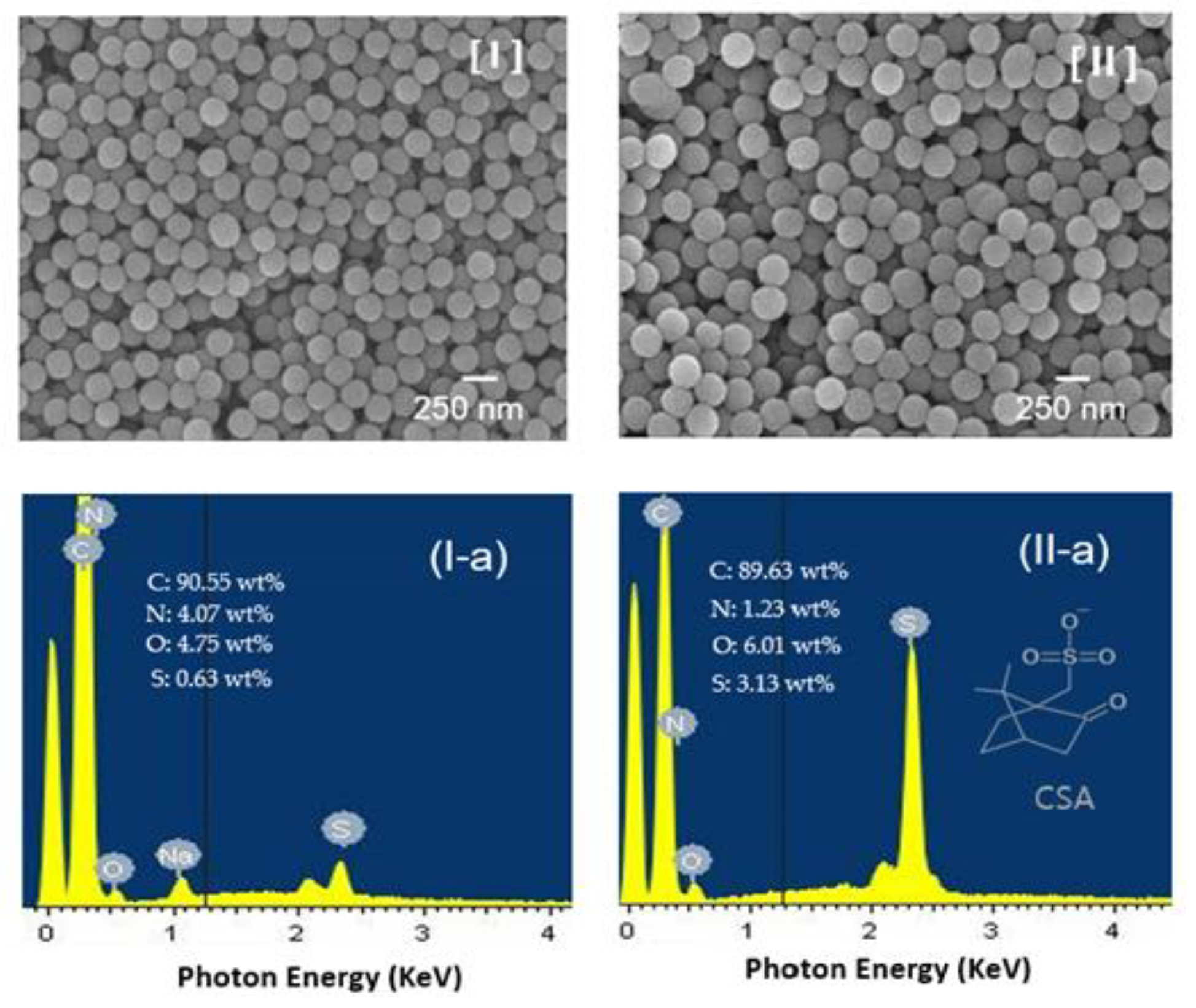

Figure 3 shows the SEM images of the as-synthesized P(Ani-co-ASNi) NPs prior to capping and the P(Ani-co-ASNi) NPs after CSA capping. As illustrated in the figure, the particles of P(Ani-co-ASNi) and CSA-doped P(Ani-co-ASNi) consist of well-ordered spherical NPs, with average diameters of approximately 235 and 265 nm, respectively. The diameter of CSA-capped P(Ani-co-ASNi), which was produced by secondary capping with CSA, is approximately 30 nm larger than that of P(Ani-co-ASNi). These results suggest that CSA is enveloped on the P(Ani-co-ASNi) surface, with an estimated thickness of approximately 30 nm. The electrical resistance of the as-prepared P(Ani-co-ASNi) NPs was measured to be approximately 1.2 MΩ, whereas upon capping with CSA to form a thickness of about 30 nm, the resistance decreased to approximately 0.6–0.8 MΩ. The observed decrease in electrical resistivity is attributed to the partial doping effect of camphorsulfonic acid (CSA), which incorporates a sulfonic acid group as a substituent. CSA functions not only as a capping agent but also serves as a dopant, thereby contributing to enhanced electrical properties. These findings suggest that CSA plays a dual role, acting simultaneously as a surface modifier and a chemical dopant. In addition, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) spectra were analyzed to determine the elemental composition of the NPs (

Figure 3, I-a and II-a). In this study, a thin CSA layer containing a -SO

3H functional group uniformly coated the entire surface of the P(ANi-co-ASNi) particles. Consequently, the mass percentage of sulfur (S) atoms in CSA-capped P(Ani-co-ASNi) was quantified and compared with the proportions of other constituents. The results of the analysis (

Figure 3 (II-a)) show that the mass percentage of S atoms in the CSA-capped P(Ani-co-ASNi) particles is 3.13%. In contrast, the EDS spectrum of P(Ani-co-ASNi) particles without CSA (

Figure 3 (I-a)) reveals only a small quantity of S atoms, amounting to 0.63%. The presence of these S atoms in the P(Ani-co-ASNi) particles is attributed to the -SO

3H group, which acts as a substitutent in PASNi, a copolymer of PANi. Ultraviolet/visible/near-infrared (UV/Vis/NIR) spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy were used to examine changes in the charge transport properties and molecular structure of the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) copolymer (

Figure 4).

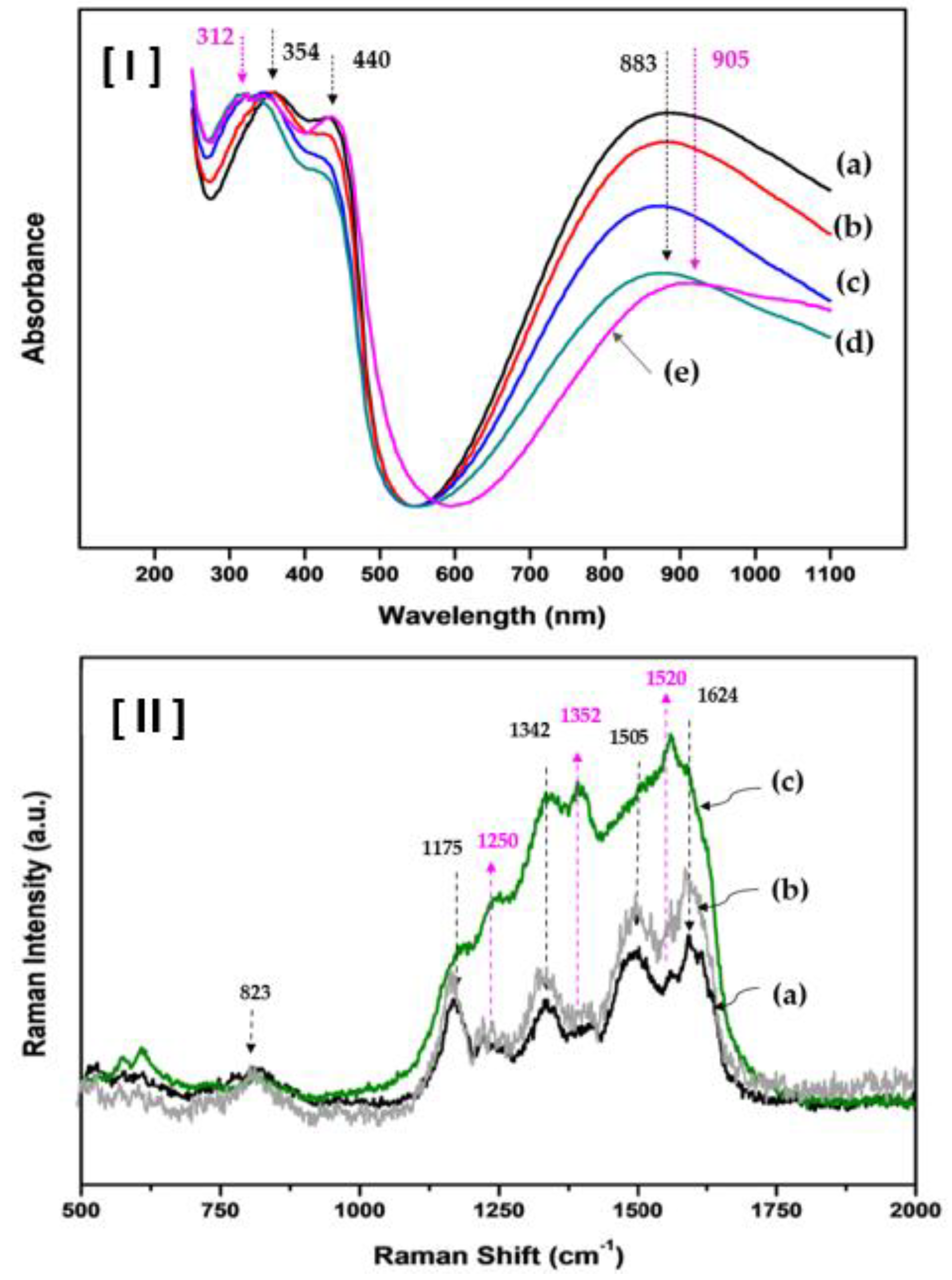

Figure 4-(I) shows the UV/Vis absorption spectra, highlighting the spectral changes corresponding to the molar ratios of ANi and ASNi in the P(ANi-co-ASNi) copolymer.

Figure 4-I-(a) shows the UV/Vis absorption spectra of the P(ANi-co-ASNi) sample with an Ani-to-ASNi molar ratio of 1:0, representing the spectrum of pure PANi. Three characteristic absorption peaks are observed at 354, 440, and 883 nm. Here, the peaks at 354 and 440 nm are attributed to the π–π* excitation of the

para-substituted benzenoid segment (-benzene-NH-benzene-). In contrast, the peak at 883 nm corresponds to the π–π* excitation of the quinoid structure (-N=quinone=N-) [

24,

25].

However, as shown in Figures 4-I-(b), (c), and (d), when the Ani-to-ASNi molar ratio was adjusted to 0.8:0.2, 0.7:0.3, and 0.6:0.4, respectively, the absorbance intensity of the peaks at 440 and 883 nm exhibited a decreasing trend. This phenomenon is attributed to the weakening of the quinoid structure in ANi as the proportion of ASNi increases. However, when the ANi-to-ASNi molar ratio in CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) was 0.5:0.5, a new UV/Vis absorption peak emerged (

Figure 4-I-(e)). Specifically, a new absorption peak emerged at 312 nm, and the peak at 883 nm shifted to 905 nm, extending into the near infrared (NIR) region. In contrast, no notable changes were detected in the peaks at 354 and 440 nm. The peak at 312 nm appears to be due to self-doping induced by the quinonoid region, which forms when the sulfonic acid group of ASNi donates electrons to the PASNi chain. In the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) structure with an ANi-to-ASNi molar ratio of 0.5:0.5, the sulfonic acid ion of CSA is believed to interact with P(ANi-co-ASNi) via the π-conjugated chain, resulting in protonation at the imine nitrogen sites. This interaction promotes the formation of a π-conjugated system with delocalized electrons, thereby enhancing electrical conductivity. Experimentally, the electrical resistance of pristine P(ANi-co-ASNi) was measured to be approximately 1.2 MΩ, whereas that of CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) was reduced to 0.6–0.8 MΩ, indicating a resistance decrease of over 30%.

Raman spectroscopy was performed to investigate the chemical bonding structures and their influence on the charge transport mechanism in CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) (

Figure 4 (II)).

Figure 4-II-(a) shows the Raman spectrum of the P(ANi-co-ASNi) sample with an ANi-to-ASNi molar ratio of 1:0, representing the Raman spectrum of pure PANi. The band at 823 cm

-1 is attributed to the C–H out-of-plane vibration in the 1,4-distributed benzene ring. Peaks corresponding to the bending modes of the benzene ring, the C–N stretching of the aromatic ring, and the stretching of the charged C–NH⁺ group were observed between 1250 and 1352 cm

-1. The bands at 1175 cm

-1 are assigned to the -SO₃H group associated with CSA. In addition, peaks for the C=C stretching of the quinoid structure (-N=quinone=N-) are observed at 1624 cm

-1, whereas the bands at 1505 cm

-1 are attributed to the C=C stretching of the benzoid structure (-N=benzene=N-) [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Finally, the intensity ratio of the bands at 1624 cm

-1 and 1505 cm

-1 reflects the conjugation length and doping level of the PANi chain. Typically, longer conjugation lengths and higher doping levels result in a more pronounced intensity of the 1624 cm

-1 peak compared to the 1505 cm

-1 peak [

30]. Figures 4-II-(b) and (c) show the Raman spectral characteristics of the copolymers synthesized with Ani-to-ASNi molar ratios of 0.8:0.2 and 0.5:0.5, respectively. As the ASNi content increased, a marked enhancement in the intensities of the peaks at 1250, 1352, and 1520 cm

-1 was observed. In addition, the Raman absorbance in the range of 1175 and 1624 cm

-1 was significantly stronger than that of pure PANi (

Figure 4-II-(a)). Accordingly, the peak at 1250 cm

-1 in CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) is attributed to the -SO₃H substitution group within the ASNi structure. The peak at 1352 cm

-1 corresponds to the stretching mode of the charged C–NH⁺ group within the quinoid structure of PASNi, and the peak at 1520 cm

-1 corresponds to the C=C/C–C stretching mode of the benzoid structure of PASNi.

Acetone gas, found in trace amounts of less than 1 ppm in human exhaled breath, is associated with metabolism and has been used as a medical biomarker for diabetes [

31,

32,

33]. Therefore, it is essential to accurately detect acetone gas concentrations in the range of tens of ppb emitted during respiration. In this study, we developed an acetone gas sensor by drop-casting an ink solution comprising CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) onto a sensor substrate integrated with a pair of gold electrodes. The test cell consists of a pair of gold electrodes embedded on a Si substrate, serving as the sensor. Acetone gas concentrations of up to 1 ppm and gaseous H₂O levels of up to 1% RH were stably detected using the developed sensor at room temperature. The real-time responses of the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) sample were systematically measured to evaluate their sensing capabilities for acetone and H₂O vapor (

Figure 5). The sensor's performance was evaluated under various conditions, including repeated recovery characteristics, fluctuations in temperature, humidity, and gas flow rates (

Figure 6).

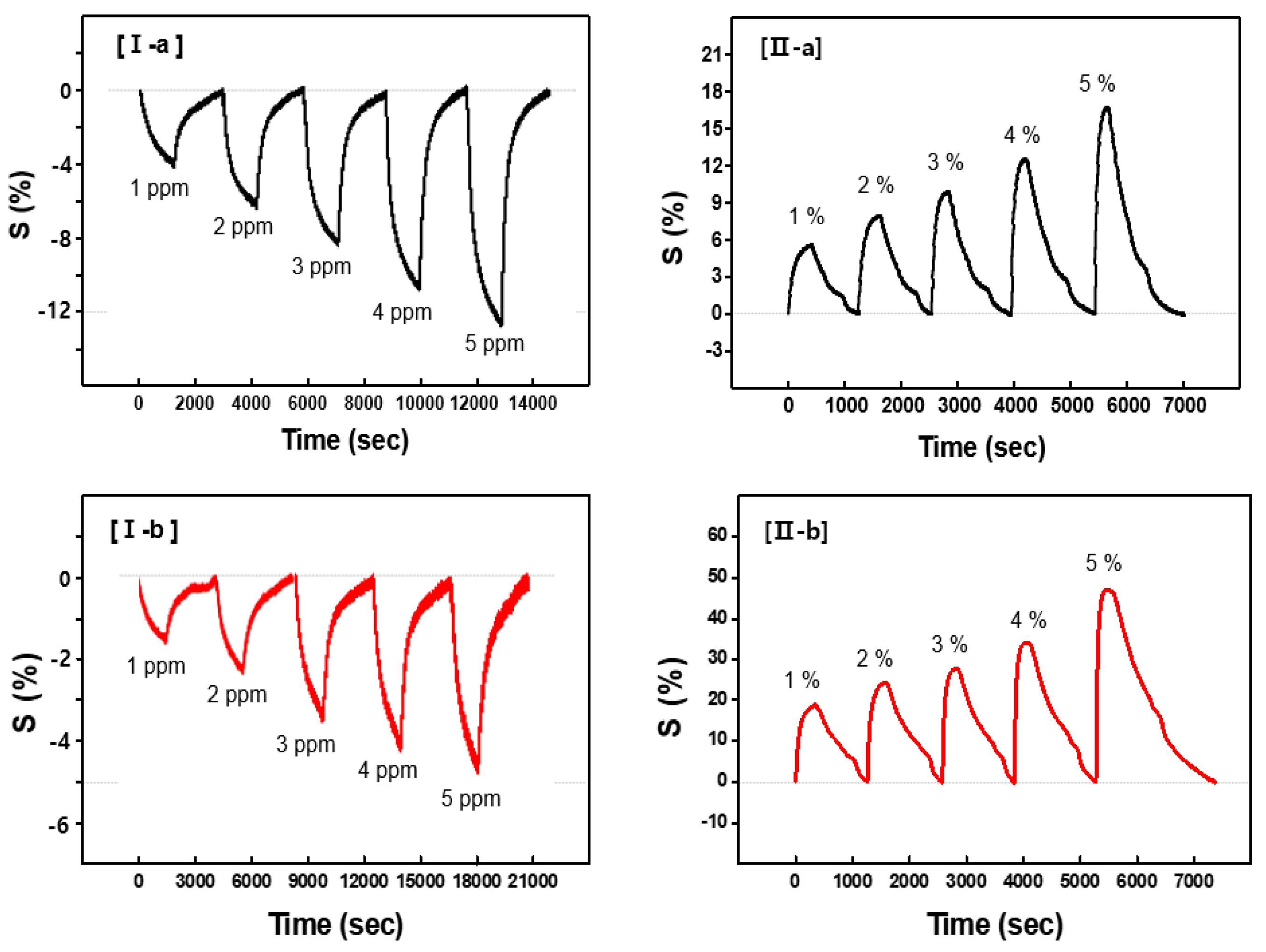

Figure 5-(I) shows the continuous dynamic response of the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) sensors to acetone gas concentrations ranging from 1 to 5 ppm, maintained at a constant temperature of 25°C and 0% RH.

Figures 5-(I-a) and 5-(I-b) show the sensor performance of the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) copolymers, with ANi-to-ASNi molar ratios of 1:0 and 0.5:0.5, respectively. The responsiveness (S%) of the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi)-based sensors to acetone gas was measured in real-time using the normalized change in resistance, ΔR/R

i = (R

i -R

0)/R

i x 100. Here, Ri denotes the initial resistance before gas exposure, R

0 denotes the real-time resistance during gas exposure, and ΔR represents the difference between Ri and R

0, which is calculated after gas exposure.

Figure 5-(I-a) shows the continuous dynamic response of a CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) sample with an ANi-to-ASNi molar ratio of 1:0, corresponding to pure PANi, during its exposure to acetone gas. The effective S value was measured for each acetone gas concentration (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 ppm), with the S value at 1 ppm determined to be 4.2 (absolute value). In addition, this S value showed that an increase in the gas concentration corresponded to a proportional decrease in relative reactivity in the negative (-) direction. This negative shift in the S value is attributed to the decreased charge density of the PANi backbone caused by the adsorption of acetone gas. The increased electrical resistance observed during the process can be attributed to the interaction between acetone gas molecules and the amine nitrogen (–NH⁺) sites present in the backbone of the PANi polymer. This indicates that hydrogen bonds (O–H) are formed between the NH⁺ sites of PANi and the oxygen (O) atoms in acetone molecules. These newly formed O–H bonds interfere with charge transfer in the PANi chains, causing a negative shift in the S value of the PANi structures. This observation suggests that hydrogen bonding significantly influences the electronic properties of the PANi polymer, particularly charge transport in the PANi backbone.

Figure 5-(I-b) shows the continuous dynamic response of the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) copolymers synthesized with equal ANi-to-ASNi molar ratio. The S value for acetone gas in these copolymer samples exhibited a significant reduction compared to that of pure PANi (

Figure 5-(I-a). At 1 ppm, the S value was 1.9 (in absolute terms), reflecting the diminished sensitivity under these specific conditions. Despite the marked decrease in responsiveness compared to pure PANi, the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi)-based sensor showed consistent reactivity and excellent reproducibility to acetone gas. In the P(ANi-co-ASNi) copolymer, PASNi represents PANi substituted with an SO

3H group. The incorporation of the SO

3H substituent serves as an intrinsic dopant, effectively transforming the material into a self-doped conductive polymer while ensuring stable electrical conductivity. However, as shown in

Figure 5-(I-b), the sensitivity of the copolymer was relatively stable, exhibiting consistent proportional changes with respect to the acetone gas concentration. This stability highlights the reliability of the copolymer in effectively detecting gas at various concentrations. The response time refers to the interval required for the conductance of a sensor to achieve 90% of its maximum (saturated) response signal, as shown in

Figure 2. Conversely, the recovery time is the duration required for a sensor to return to a conductance level that is 10% above its baseline value when exposed to air. These metrics are crucial for evaluating the efficiency and reliability of sensor performance under dynamic conditions. The CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi)-based sensors, with ANi-to-ASNi molar ratios of 1:0 and 0.5:0.5, exhibited response times of 1,200 and 1,700 s, respectively, when subjected to 1-ppm acetone gas at 25°C and 0% RH. Furthermore, their recovery times were measured at 1,500 and 2,700 s, respectively. In particular, as depicted in the figure 4, the recovery time exhibited a significant increase with increasing reacting gas concentration. This prolongation can be ascribed to the extended desorption process at room temperature, which becomes more time-intensive as the amount of gas adsorbed increases. Interestingly, this effect was more prominent in the copolymer bound to PASNi than in pure PANi, highlighting the distinct desorption dynamics influenced by the structural differences between the materials.

Figure 5-(II) shows the continuous dynamic response (S) of the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) sensors exposed to gaseous H

2O concentrations ranging from 1 to 5% RH. The S value for the CSA-doped pure PANi sample was approximately 5.8 when exposed to 1% RH H

2O vapor (

Figure 5-(II-a)). This result reflects the high S value of the sensor to low H

2O vapor concentrations under the specified conditions. Unlike acetone gas, H

2O vapor exhibited a distinctive trait in which the responsive value increased proportionally in the positive (+) direction as the concentration increased. Here, H

2O vapor is thought to function as an acid, interacting with CSA-doped pure PANi chains to reduce their electrical resistance. This effect aligns with the properties of p-type semiconductors, where charge carriers (holes) are positively influenced, enhancing conductivity. As shown in

Figure 5-(II-b), the S value of the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) copolymer samples increased by approximately four times that of pure PANi. This remarkable improvement appears to be primarily driven by the significant contribution of ASNi, which substantially enhances the reactivity of the copolymer toward H

2O vapor.

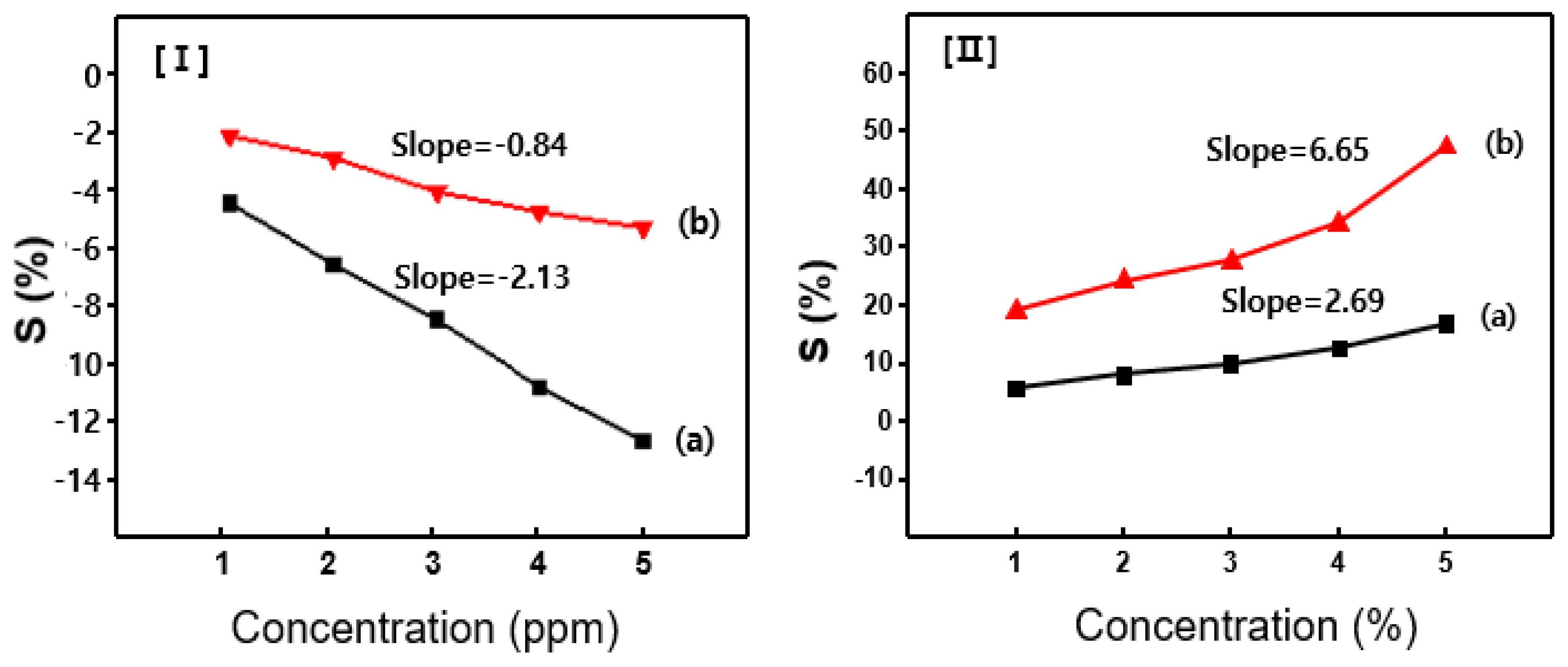

Figure 6 shows that the sensors exhibit a linear response, where the S value consistently increase with increasing concentration of the injected gas. This linearity highlights the reliability and accuracy of the sensors detecting various gas concentrations, highlighting their potential for precise quantitative analysis. Based on these results, the slope of the S value vs. acetone gas concentration was analyzed, leading to the determination of sensitivity in units of ppm

-¹. The acetone sensors based on pure PANi and the P(ANi-co-ASNi) copolymer exhibited sensitivity values of 2.13 and 0.84, respectively (

Figure 6-(I)). The H₂O vapor sensor exhibited significantly higher sensitivity (2.69) than the acetone sensor (6.65) (

Figure 6-(II)). All experimental data were acquired from a minimum of five repeated measurements conducted under identical environmental conditions, and the averaged values were utilized for analytical evaluation. To ensure precision and reliability, data falling within the measurement error range were excluded from the final analysis. However, the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi)-based sensor exhibited a remarkable sensitivity value of 6.65 to H₂O molecules. This result can be attributed to the hydrophilic nature of the -SO

3H substitution group in PANi, which promotes the adsorption of H₂O molecules. In addition, the presence of the -SO

3H group creates favorable conditions for interactions with H₂O molecules, enhancing the reactivity and sensitivity of the sensor to H₂O vapor.

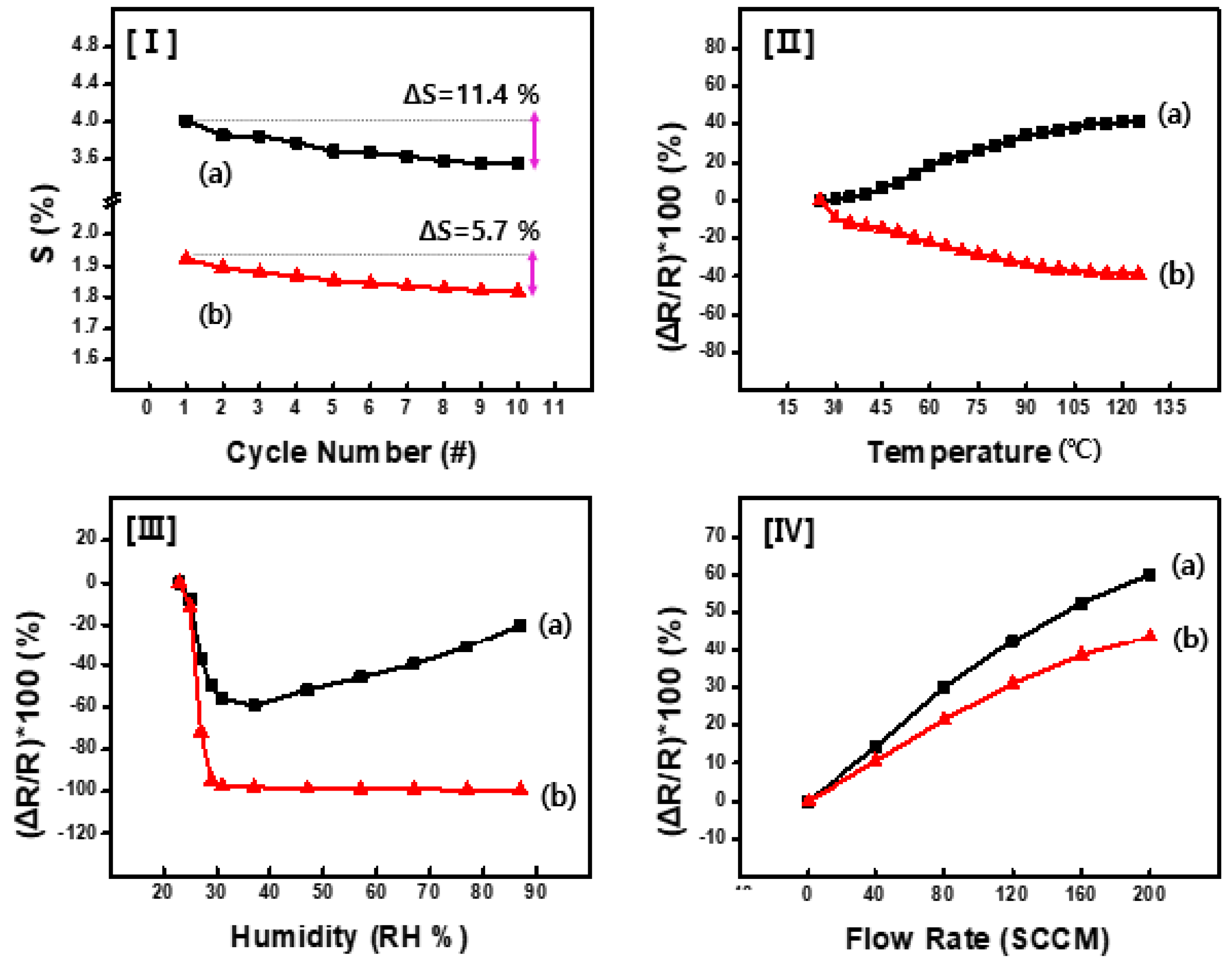

Figure 7-(I) shows the results of the reliability verification experiments in which cyclic testing was conducted on the acetone sensor samples based on CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi). These experiments aimed to evaluate the performance consistency and stability of the sensor under repeated exposure to acetone gas, providing insights into its durability and long-term reliability. These experiments were conducted under rigorously controlled conditions, including 25°C, 0% RH, and an acetone gas concentration of 1 ppm. This approach ensured consistency in the experiment environment, enabling a thorough assessment of the sensor performance over repeated cycles. As shown in

Figure 7-(I-a), the PANi-based sensor exhibited a ΔS value exceeding 11% during the 10-cycle test at an acetone gas concentration of 1 ppm. In contrast, as shown in

Figure 7-(I-b), the P(ANi-co-ASNi)-based sensor exhibits a more moderate change in ΔS (approximately 5%–6%) while maintaining a relatively high recovery rate. Figures 7-(II), (III), and (IV) show the performance of the sensor under various external environmental factors such as temperature, RH, and gas pressure. The changes in performance were carefully tracked by monitoring variations in the electrical resistance of the sensor cell.

Figure 7-(II-a) illustrates the impact of temperature on the performance of the PANi-based sensor. As the external temperature increased to 125°C, the electrical resistance changed, increasing by approximately 40% in the positive (+) direction. In contrast, for the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi)-based sensor (

Figure 7-(II-b)), a proportional decrease in its electrical resistance of approximately 40% was observed under the same conditions. These results indicate that in CSA-capped PANi sensors, electrical resistance decreases as temperature rises. In contrast, CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi)-based sensors exhibit an inverse behavior, with resistance increasing as the temperature elevates. This highlights the differing sensitivity dynamics between the pure PANi doped with CSA and CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi)-based sensors at different temperature.

Figure 6-(III) shows the variations in the electrical resistance of the sensor as it responds to various RH levels ranging from 0% to 87%.

It is widely recognized that acetone gas sensors are particularly susceptible to ambient humidity. As shown in

Figure 7-(III), an interesting trend was observed in this study: all tested sensors exhibited a proportional decrease in electrical resistance as the relative humidity (RH) increased up to 28% RH. Beyond this threshold, however, the sensors displayed a non-linear and divergent response pattern. This suggests that under low humidity conditions (<28% RH), the interaction between acetone molecules and the PANi backbone is enhanced—likely due to the absence of significant moisture interference, resulting in improved charge transfer. In contrast, at higher humidity levels (>28% RH), the adsorption of acetone appears to be hindered by increasing amounts of water vapor. This suggests that under low humidity conditions (<28% RH), the interaction between acetone molecules and the PANi backbone is enhanced—likely due to the absence of significant moisture interference, resulting in improved charge transfer. In contrast, at higher humidity levels (>28% RH), the adsorption of acetone appears to be hindered by increasing amounts of water vapor. Prior literature [

34,

35] supports this behavior, indicating that acetone molecules form hydrogen bonds with water vapor—particularly via interactions between the carbonyl oxygen of acetone and the hydroxyl (-OH) groups in water molecule—leading to a reduced availability of acetone for binding with the PANi backbone. Under identical test conditions, the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) sensor (

Figure 7-(III-b)) showed minimal variation in resistance even above 28% RH, with a relative change below 5%. This stability is attributed to the bulky sulfonic acid (-SO₃H) groups on the ASNi units, which contribute to a sterically hindered surface structure that resists water condensation and limits moisture-related interference. These observations suggest that at RH levels beyond 28%, acetone adsorption approaches saturation due to competition with water vapor. This behavior may provide an opportunity for stable signal output in humid environments. We also speculate that saturation humidity could shift with temperature; however, such effects were beyond the scope of this study and require further investigation in future work. As shown in

Figure 7-(IV), the P(ANi-co-ASNi)-based sensor exhibited approximately 15% lower pressure resistance to gas flow compared to the pure PANi-based counterpart. This discrepancy underscores distinct structural and compositional differences that significantly influence the performance of the two sensors under varying pressure conditions.

Selectivity is a key parameter in the practical application of gas sensors. To evaluate selectivity, responsiveness to various organic gases, including ethanol, methanol, chloroform, xylene, toluene, cyclohexane, and hydrogen, was investigated. According to the previous results, the CSA-capped P(ANi-co-ASNi) sensor with an ANi-to-ASNi molar ratio of 0.5:0.5 exhibited an S value of –5.2 for 5-ppm acetone gas and +20 for 1% H2O gas. The sensor also exhibited a response (S= –12 at 5ppm) to ethanol and methanol gases but negligible responses, even at a high concentration of 5 ppm, to other gases such as xylene, toluene, cyclohexane, and hydrogen. Interestingly, the sensor exhibited negative responsiveness to gases acetone and alcohols, which possess acidic properties, because of a decrease in the electrical resistance of the sensor. Conversely, the sensor exhibited positive responsiveness to gases with basic properties, such as chloroform, toluene, xylene, and cyclohexane.