1. Introduction

Polyaniline (PANI) has garnered considerable scientific interest since conducting polymers were discovered. It has been widely recognized for its diverse range of potential applications (e.g., gas sensors, catalysis, composite fabrication, adsorption, energy storage devices, and many others) and its notable advantages, encompassing facile synthesis, cost-effectiveness, robust environmental stability, and exceptional performance characteristics [

1]. The demand for conjugated (semiconducting) polymers with specific morphologies and properties tailored for particular device applications necessitates the development of simple and reliable synthesis methods. They are currently produced using a variety of techniques, including chemical oxidation polymerization [

2], electrochemical polymerization [

3], metal-catalyzed coupling [

4], solid-state polymerization [

5], Lewis acid-assisted polymerization [

6], acid-assisted polymerization [

7], photoinduced polymerization, and high-temperature oxidant-free acid polymerization [

8]. Its synthesis depends on several factors such as oxidant, solvent, electrode material, pH, temperature, and presence of chemical additives (like oligoaniline and π-bonding compounds) as well as the composition of the electrolyte and dopant anions [

9]. These factors modulate the PANI molecular structures and properties, necessitating careful optimization to obtain specific physicochemical properties that enhance performance in various applications. Chemical oxidative polymerization is the primary approach for producing PANI with a controlled chemical structure, size of the chains and morphology, showing a promising strategy for industrial synthesis. PANI can be synthesized by oxidative polymerization using ammonium persulfate (APS) as an oxidant in strong or weak acidic solutions. However, recent studies have introduced a novel synthesis approach for fabricating sensing layers utilizing PANI films and chelating agents [

7]. Aniline was polymerized using the acid-assisted polymerization method, where concentrated formic acid was used as a medium, alongside APS as the initiator of the reaction. This synthesis surpassed other traditional PANI synthesis methods by achieving full conversion of the monomer in a 24-hour period at ambient temperature, producing a stable solution, however, at a slow pace.

The current study aims to elucidate the timeframe required for a complete synthesis of PANI and subsequently, perform a comprehensive characterization of the resultant PANI solution. Glassy carbon’s (GC) physical and chemical characteristics have made it an intriguing and often-used electrode material. GC is an inert electrode used due to its relatively low oxidation rate, good chemical inertness, very small pore diameters, and reduced gas and liquid permeability [

10], making it a favorable material for electrocatalytic applications. The physicochemical characteristics of GC electrodes are significantly influenced by the initial polymer and the carbonization temperature [

11]. As they are shown to be one of the most intriguing and modified electrodes in electrochemical measurements with improved electrocatalytic performance, GC can be activated by several procedures, including vacuum heating, treatment with laser, mechanical polishing, carbon arc, and ultrasonication [

12].

In this study, we focus primarily on the PANI synthesis by method with two different APS concentrations (PANI1 and PANI2), the characterization of PANI morphologies, and the application of the cyclic voltammetry method (CV) to evaluate the electroactive performance of PANI for supercapacitor applications.

2. Results and Discussion

In this study, stable PANI suspensions were successfully synthesized using acid-assisted polymerization method [

7]. Two PANI suspensions with different initiator loading of APS were prepared. The stoichiometric feeding ratio of aniline to APS was reported to vary for the synthesis of different PANI forms [

13].

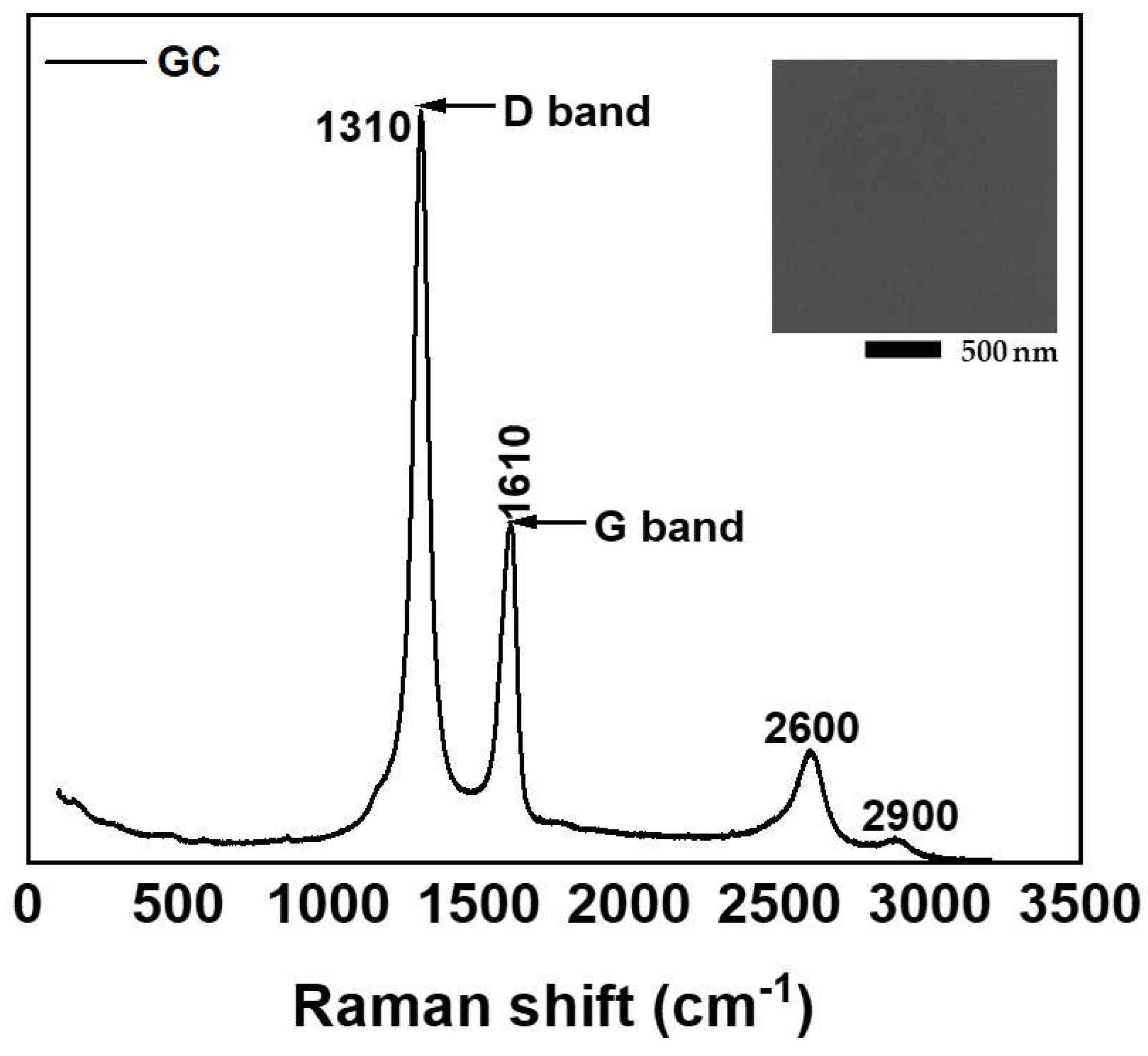

2.1. Raman Spectroscopy of Glassy Carbon (GC)

The intention of measuring the Raman Spectroscopy of GC was to prove that the substrate does not affect the Raman spectra of PANI. The Raman spectra of GC samples were employed with a 785 nm excitation wavelength, revealing two major peaks, as shown in

Figure 1. These peaks located around 1310 cm

-1 (D band) and 1610 cm

-1 (G band) are characteristic features of graphitic carbon structures [

14]. The D band, associated with disorder-induced Raman scattering, is not present in perfect single-crystal graphite [

15]. Recent studies suggest that Raman scattering by double resonant is a likely mechanism for the origination of D bands [

16]. The G band, coming from an in-plane stretching vibration of sp

2-bonded carbon atoms, indicates the presence of graphitic-like structures [

17]. The relative intensity ratio of the D and G bands (I

D/I

G) and the linewidth of the D band are key indicators of the sample’s graphitic quality and defect density. In addition to D and G bands, the second-order Raman peaks near to 2600 cm

-1 and 2900 cm

-1 are also well recognizable, and correspond to 2D peak and G+D peak combination, respectively [

17,

18]

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis of the GC sample showed a uniform smooth surface morphology consistent with the amorphous nature of glass carbon. No distinguishable features or topographical details were observed within the resolution limits of the SEM, suggesting a highly homogenous material.

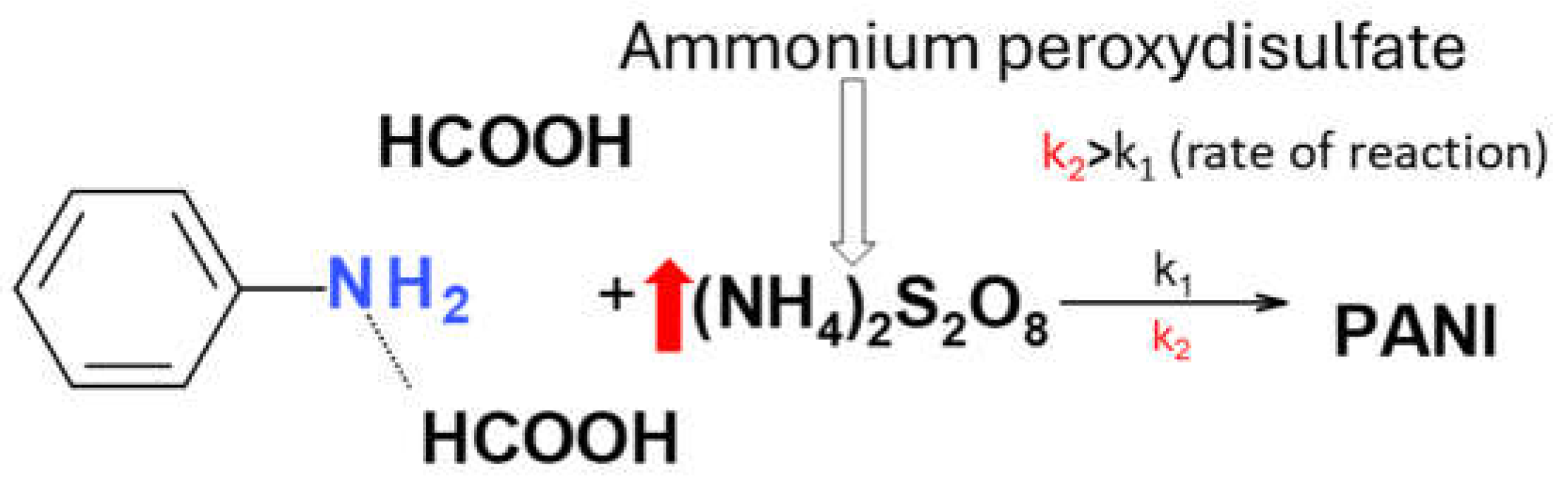

2.1. Synthesis of PANI1 and PANI2

The synthesis of PANI exhibits a strong dependence on the reaction medium. The concentrated formic acid plays a pivotal role in PANI synthesis. Concentrated formic acid facilitates electron transfer between the monomer (aniline) and the initiator (APS). The synthesis of PANI involves the reaction between the Lewis base aniline and the Bronsted-Lowry acid (formic acid). This initial step likely does not necessarily involve a simple neutralization reaction. Instead, formic acid acts as a proton transfer agent, facilitating the protonation of the aniline. The resulting anilinium cation then participates in subsequent oxidative polymerization initiated by APS. This polymerization process can lead to the formation of two types of PANI backbones: one with oxidized nitrogen and another with reduced nitrogen. These variations can be mainly attributed to the aniline-to-APS ratio. A higher APS concentration in the systém tends to promote the growth of PANI2. In addition, PANI2 usually is polymerized faster than PANI1. This is due to the higher content of APS present on the surface which promotes oxidization and coupling of aniline monomers.

2.2. SEM of PANI1 and PANI2

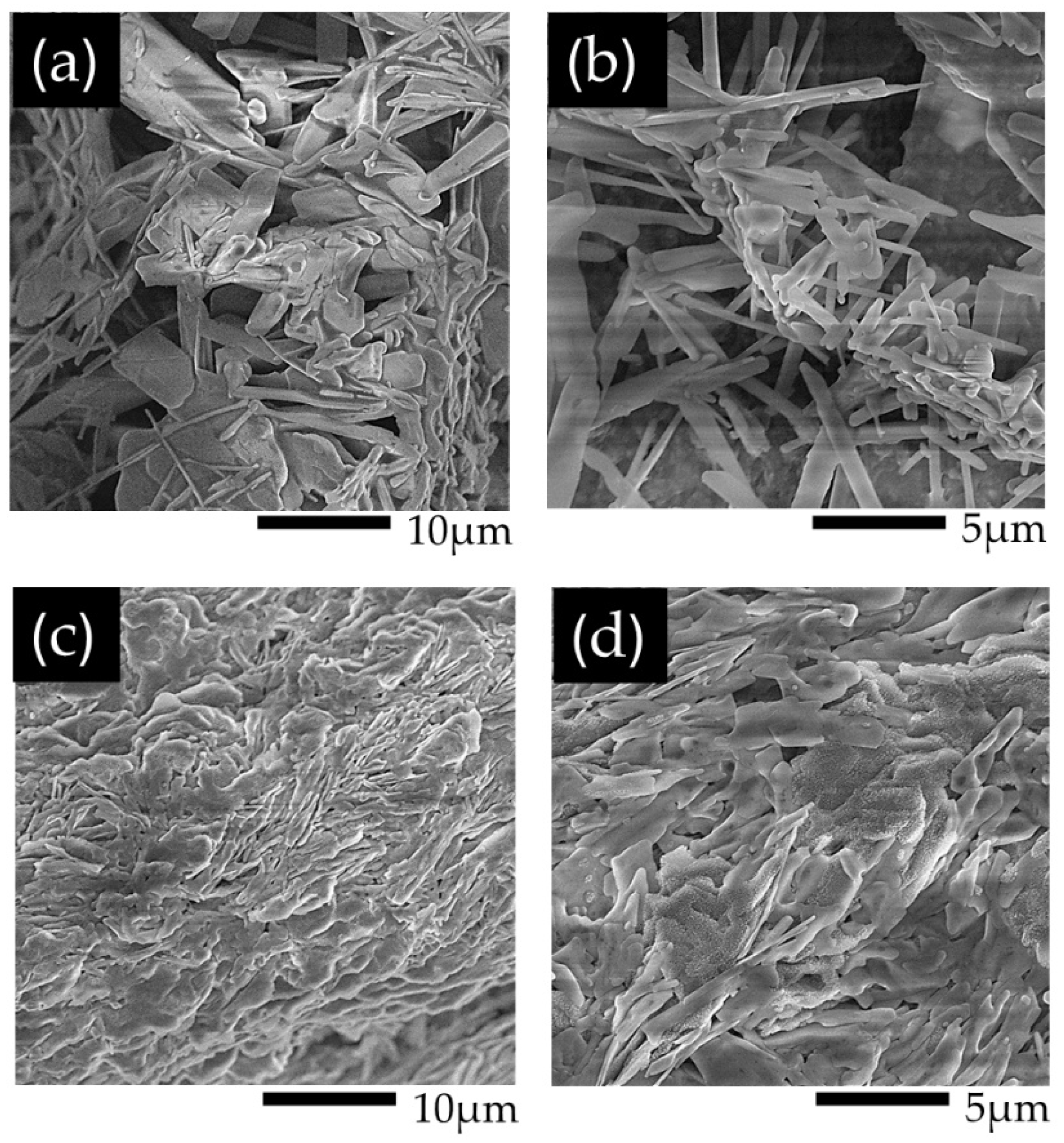

The SEM analysis of PANI 1 and PANI2 films deposited on glassy carbon revealed distinct morphological characteristics. PANI1 exhibits a porous structure with nanofibril-like features, whereas PANI2 displays densely packed features. These observations suggest different principles in PANI polymerization and crystal growth.

Figure 2.

SEM images of PANI1 at (a) low and (b) high magnification and PANI2 at (c) low and (d) high magnification deposited on glassy carbon.

Figure 2.

SEM images of PANI1 at (a) low and (b) high magnification and PANI2 at (c) low and (d) high magnification deposited on glassy carbon.

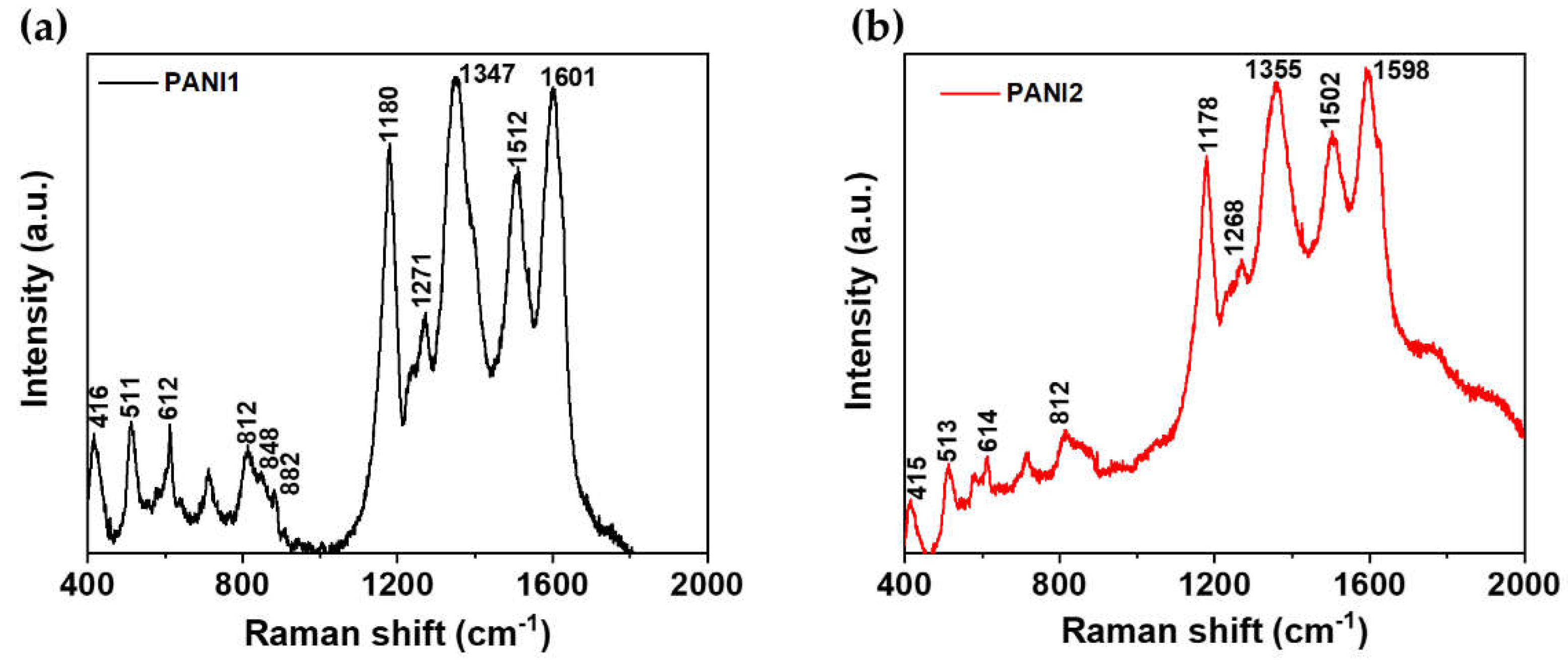

2.3. Raman Measurement of PANI1 and PANI2

The chemical composition and structures of PANI1 and PANI2 were investigated by Raman spectroscopy with an excitation line of 785 nm. Raman spectra with labeled most prominent peaks are shown in

Figure 3a and

Figure 3b, respectively. The most prominent peaks in the Raman spectra of PANI1 and PANI2 are seen at ~1600 cm

-1 and 1500 cm

-1, corresponding to C–C stretching vibrations of semiquinoid rings and - C=N- stretching imine sites, respectively [

13,

19]. The 1347 – 1360 cm

-1 peaks indicate semiquinone cations radicals in delocalized polaronic structures and C-N+ stretching vibrations in highly localized polarons [

20]. The in-plane C-H bending in the quinoid unit is attributed to the peak at around 1180 cm

-1 [

21]. From the Raman spectra, it can be confirmed that both polymers have comparable chemical structures and compositions.

Table 1 details the secondary peaks in

Figure 3a,b.

2.4. Electrochemical Applications

To investigate the impact of PANI synthesis on its supercapacitor properties, the GC electrode was applied as a current collector. GC electrodes were cleaned before PANI deposition by polishing with 0.05 µm alumina and washed with deionized water. 20 µL of both PANI1 and PANI2 suspensions were drop-casted on the GC electrode keeping a similar surface area.

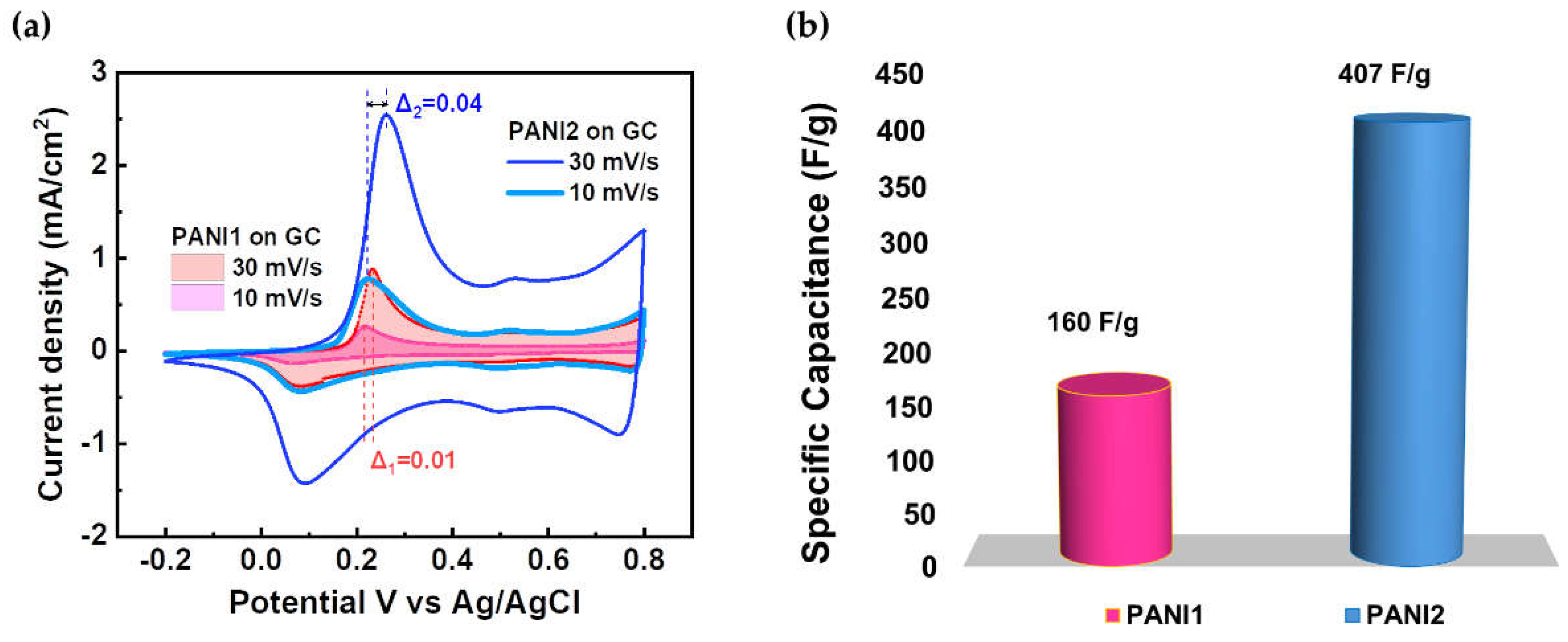

2.4.1. CV Measurements of PANI1 and PANI2 on GC

CV measurements for PANI1 and PANI2 deposited at GC were investigated in a three-electrode cell configuration in 5 M H3PO4, shown in

Figure 3a.

Figure 3a illustrates a comparative electrochemical behavior of PANI1 and PANI2 films at 10 mV/s and 30 mV/s scan rates. At the same time,

Figure 3b shows the specific capacitance (F/g) of PANI1 and PANI2 on the GC electrode calculated from CV measurements.

Figure 4.

(a) CV of PANI1 & PANI 2 on the GC measured in 5 M H3PO4 with scan rates 10 mV/s and 30 mV/s, and (b) Specific capacitance of PANI1 & PANI2 on the GC electrode.

Figure 4.

(a) CV of PANI1 & PANI 2 on the GC measured in 5 M H3PO4 with scan rates 10 mV/s and 30 mV/s, and (b) Specific capacitance of PANI1 & PANI2 on the GC electrode.

A quasi-reversible faradic process characterized by both oxidation and reduction peaks is clearly recognized. An increase in the scan rate from 10 mV/s to 30 mV/s resulted in oxidation potential shifts from 0.22 V to 0.23 V for PANI1 and from 0.22 V to 0.26 V for PANI2. For the reduction peaks, no scan rate dependence was observed. For PANI2, the more significant shift in the oxidation potentials (0.04 V) seems to be attributed to the physio-chemical properties of PANI/GC heterostructure, in our case related to PANI2 densely packed structure and optimized charge transfer at the GC support. This unique combination makes the PANI2/GC electrode more suitable for electrochemical storage applications than the PANI1/GC.

2.4.2. Electrochemical Performance of PANI1 and PANI2 on GC

Various factors, including the resistance of the electrode, significantly influence the electrochemical performance of the electrodes. The PANI2/GC electrode revealed a substantially lower impedance and phase angle φ compared to its PANI1 counterpart. These findings suggest that the PANI2/GC electrode showed superior electrochemical properties for supercapacitor applications. A reduced impedance correlates with enhanced performance. This electrochemical behavior is attributed to the inherent properties of the GC electrode. The observed specific capacitance for PANI1 on GC is 160 F/g while that of PANI2 is 407 F/g, which is 2.5 times higher than PANI1 as shown in

Figure 3b. This difference is likely attributed to the smooth surface morphology of the GC electrode and

the densely packed morphology of PANI2

. While the experimentally determined specific capacitance of PANI2 on GC reached 407 F/g, this value remains significantly lower than the theoretically predicted value (900 F/g).

Further investigations are envisioned to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of synthesis of PANI and its interaction with the support material. Raman spectroscopy and crystallographic analyses of the PANI solution are significant for characterizing the vibrational properties and material’s structure. Given the presence of crystalline traces observed for the PANI2 in SEM, photoluminescence studies can be effective for understanding the optical properties and potential excitonic processes. Optimization of the synthesis process with varying mass loadings will allow for a systematic evaluation of the influence of PANI on the support material electrodes. The use of electrodes with lower resistivity is recommended to minimize the unwanted effects of the support’s electrical resistance on the electrochemical measurements.

3. Materials and Methods

Materials: Analytical grade aniline, ammonium peroxydisulfate – APS (99% Lachner, Czech Republic), concentrated formic acid (98% Sigma Aldrich, Czech Republic), ortho-phosphoric acid (85%, Merck, Czech Republic), and ethanol were used as received without further purification.

Synthesis of polyaniline: PANI solution was synthesized according to the following procedure: at an ambient temperature (20 - 25 °C). 0.2 ml of 0.3 M aniline was dissolved in 1 ml of ethanol and about 5 ml of concentrated formic acid, mixed with 0.047 g of 0.03 M APS dissolved in 1 ml of deionized water (aniline to APS ratio 10:1). The resulting solution was labeled PANI1. Under the same conditions, PANI2 was synthesized by doubling the amount of APS to 0.094 g (aniline to APS ratio 5:1). Doubling the amount of APS accelerated the polymerization rate of PANI2 compared to PANI1 [

23].

Scheme 1.

Reaction kinetics is characterized by reaction constants k1 and k2.

Scheme 1.

Reaction kinetics is characterized by reaction constants k1 and k2.

Characterization of PANI solution: The surface morphology of PANI films deposited on GC substrates was investigated using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Imaging was performed using a MAIA 3 SEM system (Tescan Ltd., Czech Republic) with an acceleration voltage of 10 kV in a top-view configuration.

Using a Renishaw Via Raman microscope (Renishaw, UK) with a Peltier cooled CCD detector and 442 nm (Dual Wavelength HeCd laser, model IK5651R-G, Kimmon Koha) and 785 nm lasers for excitation (Diode laser, Renishaw HPNIR785 Laser Source), Raman spectra of PANI droplets were collected. Leica objective 100x with NA 0.9 (50x/0.5 LWD) was used to gather scattered light in confocal mode. For the utilized excitations, the spectrograph was equipped with holographic gratings measuring 2400 lines/mm and 1200 lines/mm, respectively. Each sample was subjected to a continuous wave laser with a power of 1.1 mW for 10 seconds at an average distinct site, allowing for the collection of average spectra per sample. The sample damage and changes in the material caused by light are avoided by using these parameters together. The average spectra were then determined, the baseline was removed using the asymmetric least squares approach from the gathered spectra, and peak analysis was performed using Gaussian functions.

A Metrohm AUTOLAB Potentiostat/Galvanostat driven by the NOVA software was used to carry out the electrochemical measurements. A three-electrode cell configuration comprising a counter electrode (Pt), a working electrode (fabricated PANI/GC), and a reference electrode (Ag/AgCl, 3 M KCl) was utilized for the CV measurements at a scan rate of 10 mV/s and 30 mV/s. The potential ranged from -0.2 to 0.8 V vs Ag/AgCl.

4. Conclusions

In summary, PANI synthesis via acid-assisted polymerization technique has been successfully established. The concentration of APS significantly influenced the reaction kinetics, resulting in accelerated polymerization with an increased concentration of the initiator. The characterization of the PANI using SEM revealed distinct morphological features: PANI1 displayed porous nanofibril-like structures, while PANI2 exhibited densely packed structures. The SEM images of the support (GC) showed no observable features confirming a smooth and homogenous material. The electrochemical data suggests that the oxidation potential’s position depends primarily on the morphology of the PANI films, used current collector and applied electrolyte, as well as the nature of the electrode. Furthermore, the enhanced interfacial interaction between the support and PANI2, in contrast to PANI1, can be attributed to the synergistic effects including the sp2-carbon content of the GC electrode, resulting in a lower resistivity and the closely packed morphological structure of PANI2. This combination results in a more effective charge transfer that leads to the specific capacitance of 407 F/g.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and E.T.; methodology, S.B. and E.T.; software, S.B.; validation, S.B. and K.A.D. and E.T.; formal analysis, S.B.; investigation, S.B.; resources, E.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B..; writing—review and editing, S.B.; S.P.; E.T.; and A.K.; visualization, S.B.; S.P.; K.A.D.; E.T.; and A.K.; supervision, S.B.; S.P.; E.T.; and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported within the Strategy AV21 framework (VP26-Breakthrough Technologies for the Future) and by the MEYS OP JAC project SENDISO (no. CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004596), CzechNanoLab (no. LM2023051), and was partially supported by CTU university project no. SGS24/132/OHK4/3T/13.

Data Availability Statement

All generated data during this study are available at 10.5281/zenodo.13772941.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Czech Academy of Sciences within the Strategy AV21 framework (VP26-Breakthrough Technologies for the Future) and by the MEYS OP JAC project SENDISO (no. CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004596), used the infrastructure of the CzechNanoLab (no. LM2023051), and was partially supported by CTU university project no. SGS24/132/OHK4/3T/13, R. Jatskivová (SEM) and O. Babčenko (Raman).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Itoi, H.; Hayashi, S.; Matsufusa, H.; Ohzawa, Y. Electrochemical Synthesis of Polyaniline in the Micropores of Activated Carbon for High-Performance Electrochemical Capacitors. Chemical Communications 2017, 53, 3201–3204. [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, R.I.; Yoshino, K.; Hayashi, S. Preparation and Properties of Conducting Heterocyclic Polymer Films by Chemical Method. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 1984, 23, L899–L900. [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.F.; Kanazawa, K.K.; Gardini, G.P. Electrochemical Polymerization of Pyrrole. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications 1979, 635–636. [CrossRef]

- Kuwabara, J.; Tsuchida, W.; Guo, S.; Hu, Z.; Yasuda, T.; Kanbara, T. Synthesis of Conjugated Polymers via Direct C-H/C-Cl Coupling Reactions Using a Pd/Cu Binary Catalytic System. Polymer Chemistry 2019, 10, 2298–2304. [CrossRef]

- Tusy, C.; Huang, L.; Jin, J.; Xia, J. Synthesis and Investigation of Novel Thiophene Derivatives Containing Heteroatom Linkers for Solid State Polymerization. RSC Advances 2014, 4, 8011–8014. [CrossRef]

- Bonillo, B.; Swager, T.M. Chain-Growth Polymerization of 2-Chlorothiophenes Promoted by Lewis Acids. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012, 134, 18916–18919. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R.; Šeděnková, I.; Svoboda, J.; Lukešová, M.; Walterová, Z.; Tomšík, E. Acid-Assisted Polymerization: The Novel Synthetic Route of Sensing Layers Based on PANI Films and Chelating Agents Protected by Non-Biofouling Layer for Fe2+ or Fe3+ Potentiometric Detection. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2023, 11, 1545–1556. [CrossRef]

- Aydogan, B.; Gunbas, G.E.; Durmus, A.; Toppare, L.; Yagci, Y. Highly Conjugated Thiophene Derivatives as New Visible Light Sensitive Photoinitiators for Cationic Polymerization. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 101–106. [CrossRef]

- Gvozdenović, M.M.; Grgur, B.N. Electrochemical Polymerization and Initial Corrosion Properties of Polyaniline-Benzoate Film on Aluminum. Progress in Organic Coatings 2009, 65, 401–404. [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, W.E.; Dieker, J.W. Glassy Carbon as Electrode Material in Electro- Analytical Chemistry. Analytica Chimica Acta 1980, 119, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Dekanski, A.; Stevanović, J.; Stevanović, R.; Nikolić, B.Ž.; Jovanović, V.M. Glassy Carbon Electrodes: I. Characterization and Electrochemical Activation. Carbon 2001, 39, 1195–1205. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aziz, A.M.; Hassan, H.H.; Badr, I.H.A. Activated Glassy Carbon Electrode as an Electrochemical Sensing Platform for the Determination of 4-Nitrophenol and Dopamine in Real Samples. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 34127–34135. [CrossRef]

- Stejskal, J.; Sapurina, I.; Trchová, M. Polyaniline Nanostructures and the Role of Aniline Oligomers in Their Formation. Progress in Polymer Science (Oxford) 2010, 35, 1420–1481. [CrossRef]

- Tuinstra, F.; Koenig, J.L. Raman Spectrum of Graphite. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1970, 53, 1126–1130. [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, M.A.; Dresselhaus, G.; Dresselhaus, M.S.; Cançado, L.G.; Jorio, A.; Saito, R. Studying Disorder in Graphite-Based Systems by Raman Spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 1276–1290. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, C.; Reich, S. Double Resonant Raman Scattering in Graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 5214–5217. [CrossRef]

- Jurkiewicz, K.; Pawlyta, M.; Zygadło, D.; Chrobak, D.; Duber, S.; Wrzalik, R.; Ratuszna, A.; Burian, A. Evolution of Glassy Carbon under Heat Treatment: Correlation Structure–Mechanical Properties. J Mater Sci 2018, 53, 3509–3523. [CrossRef]

- Shinzawa, R.; Otsuka, A.; Nakamura, A. Growth of Glassy Carbon Thin Films and Its pH Sensor Applications. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 171. [CrossRef]

- Kohut, O.; Dragounová, K.; Ukraintsev, E.; Szabó, O.; Kromka, A.; Tomšík, E. Non-Conducting Polyaniline Nanofibrils and Their Physico-Chemical Behavior. Vacuum 2020, 171, 108955. [CrossRef]

- Morávková, Z.; Bober, P. Writing in a Polyaniline Film with Laser Beam and Stability of the Record: A Raman Spectroscopy Study. International Journal of Polymer Science 2018, 2018, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, F.; Chen, C.; Zhang, L.; Qin, Y.; Knez, M. Tuning the Conductivity of Polyaniline through Doping by Means of Single Precursor Vapor Phase Infiltration. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2017, 4. [CrossRef]

- Morávková, Z.; Trchová, M.; Dybal, J.; Bláha, M.; Stejskal, J. The Interaction of Thin Polyaniline Films with Various H-phosphonates: Spectroscopy and Quantum Chemical Calculations. J of Applied Polymer Sci 2018, 135, 46728. [CrossRef]

- Guorong, S.; Zhihai, C. J of Applied Polymer Sci - 2008 - Guorong - A New Polymerization Method and Kinetics for Acrylamide Aqueous Two-phase.Pdf. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2008, 111, 1409–1416.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).