Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

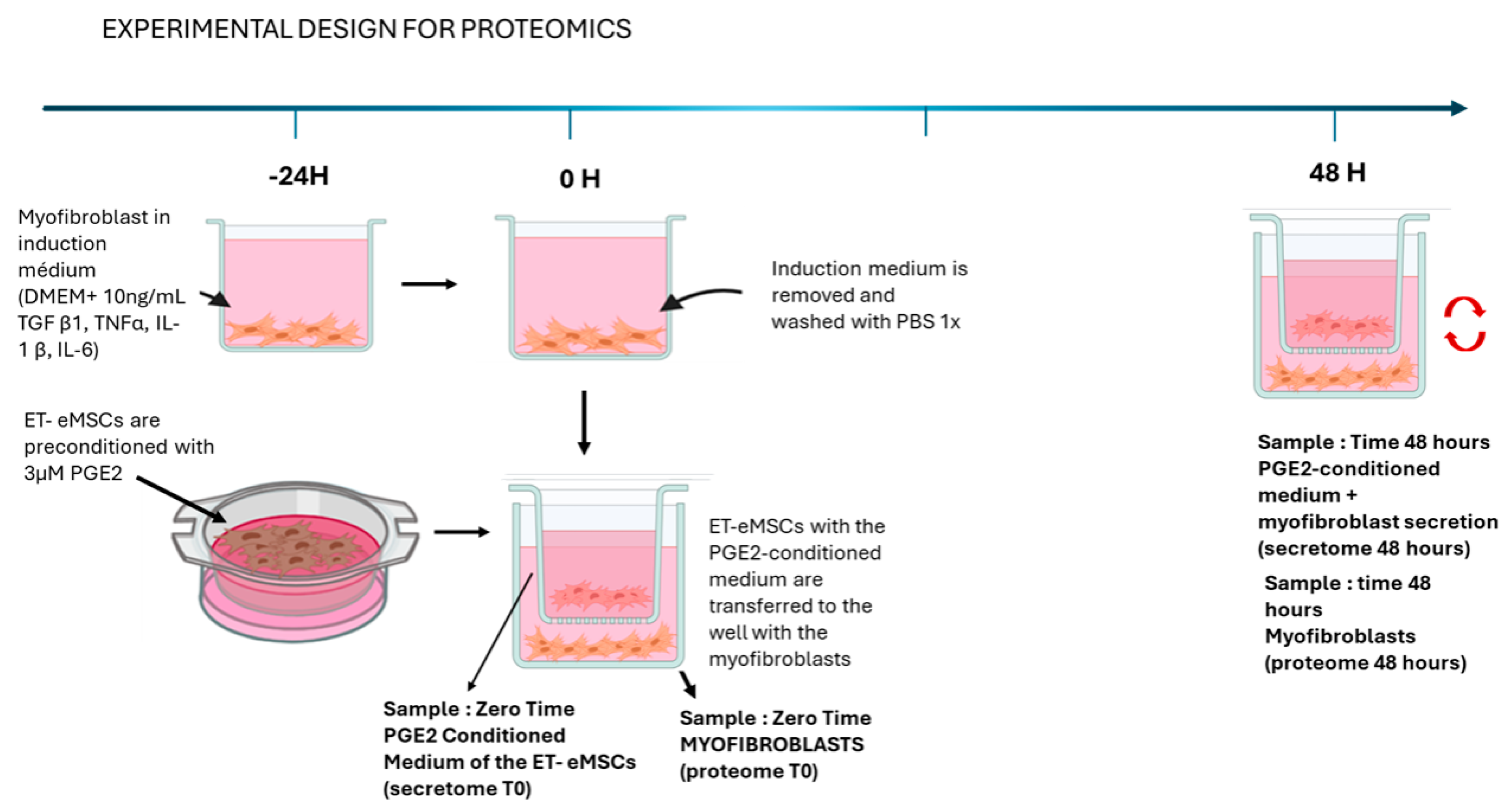

2.1.1. Experiment 1: Proteomic analysis of the interaction of endometrial myofibroblasts with PGE2-conditioned Equine mesenchymal stem cells derived from endometrial tissue (ET-eMSCs) for the study of endometrosis

2.1.2. Induction of Myofibroblasts from Endometrial Fibroblasts

2.1.3. Culture to ET-eMSC

2.1.4. Co-Culture of Myofibroblasts and ET-eMSCs Preconditioned with PGE2

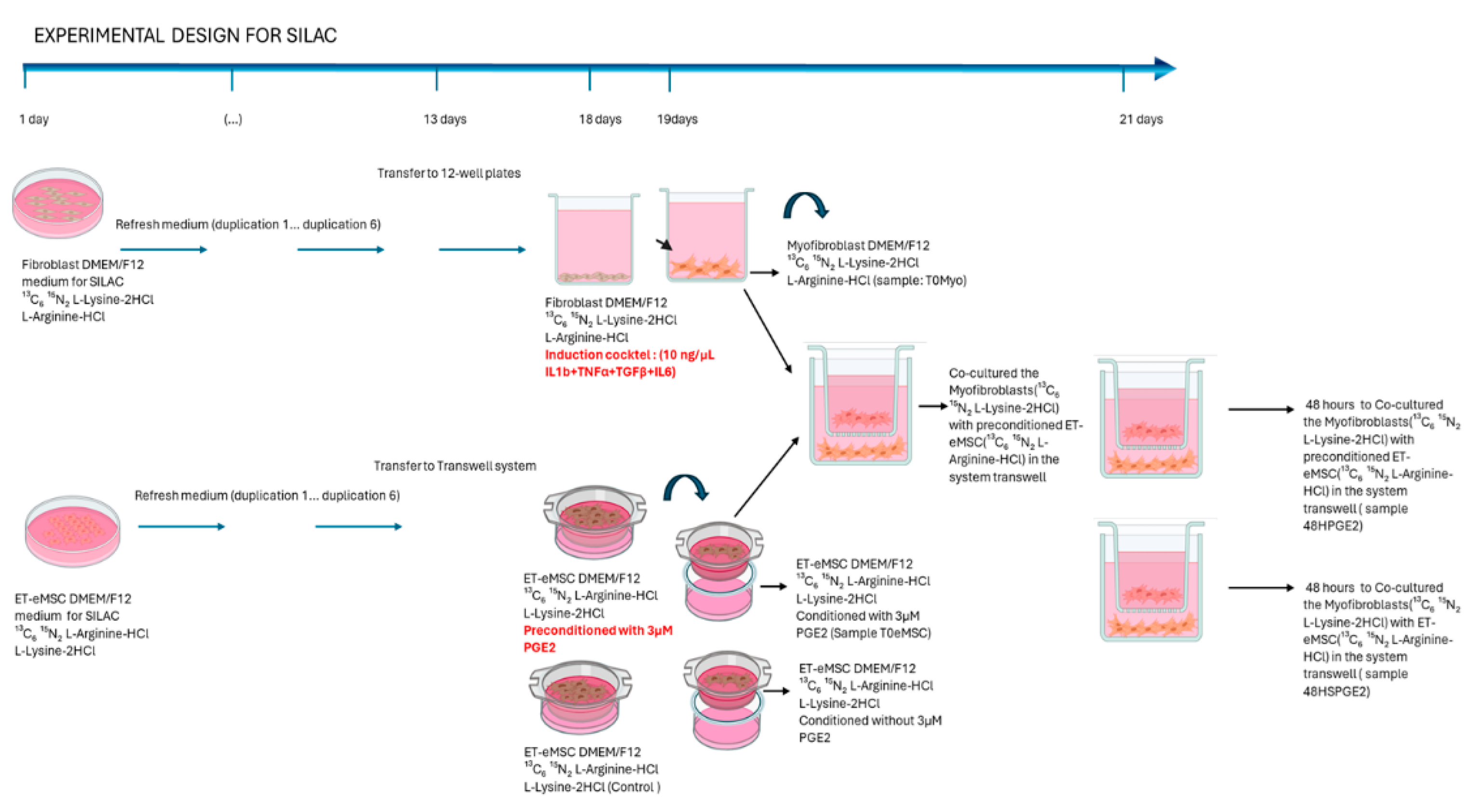

2.2. Experiment 2: Canonical Protein Identification and Relative Quantification of the Interaction Between Endometrial Myofibroblasts and PGE₂-Conditioned ET-eMSCs Were Performed Using the SILAC Protein Quantitation Kit (Trypsin)

2.2.1. Induction of Myofibroblasts from Endometrial Fibroblasts

2.2.2. ET-eMSC Pre-Conditioning with PGE2

2.2.3. Co-Cultures

2.3. Protein Extraction for Spectrometry Analysis

2.4. Preparation for Mass Spectrometry

2.5. Liquid Chromatography – Tandem Mass Spectrometry

2.6. Protein Identification and Relative Quantification

2.6.1. SILAC-Based Protein Quantification

2.7. Bioinformatics Analysis

3. Results

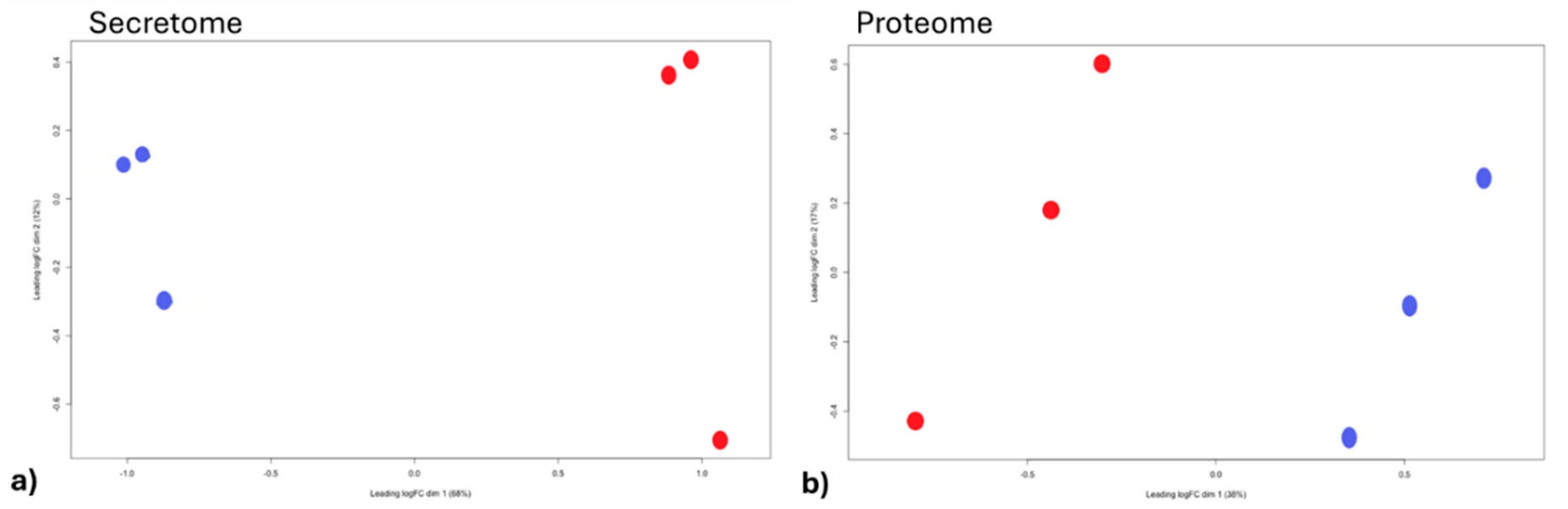

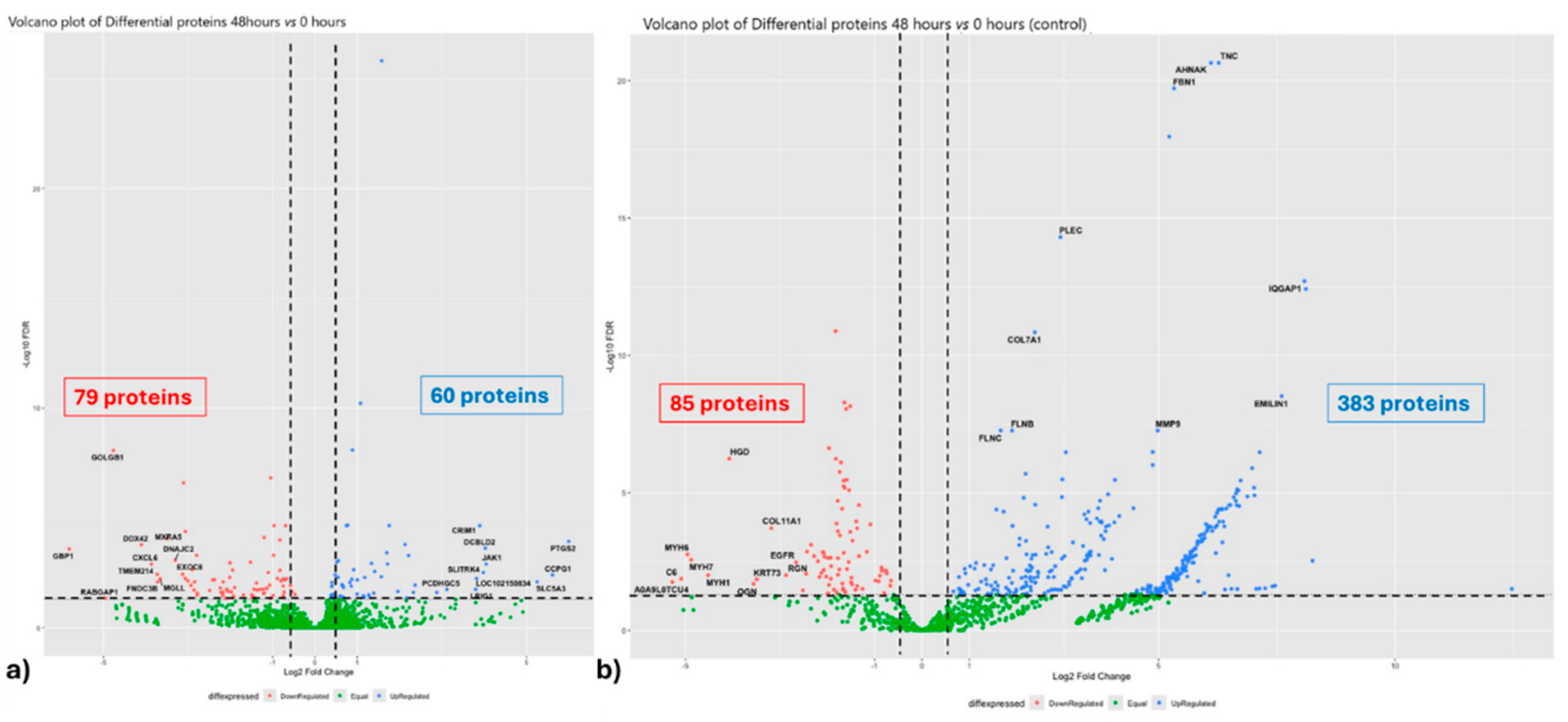

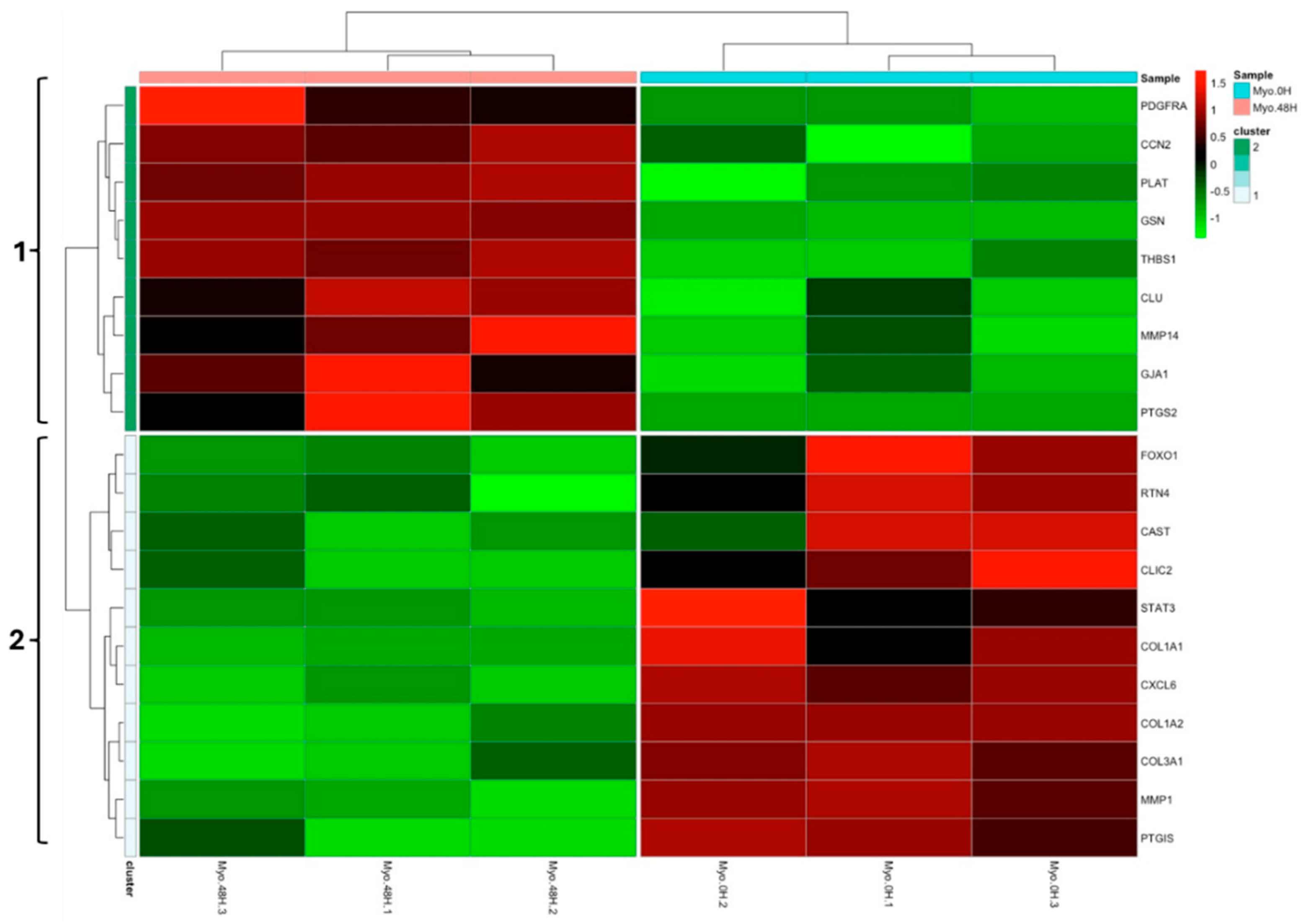

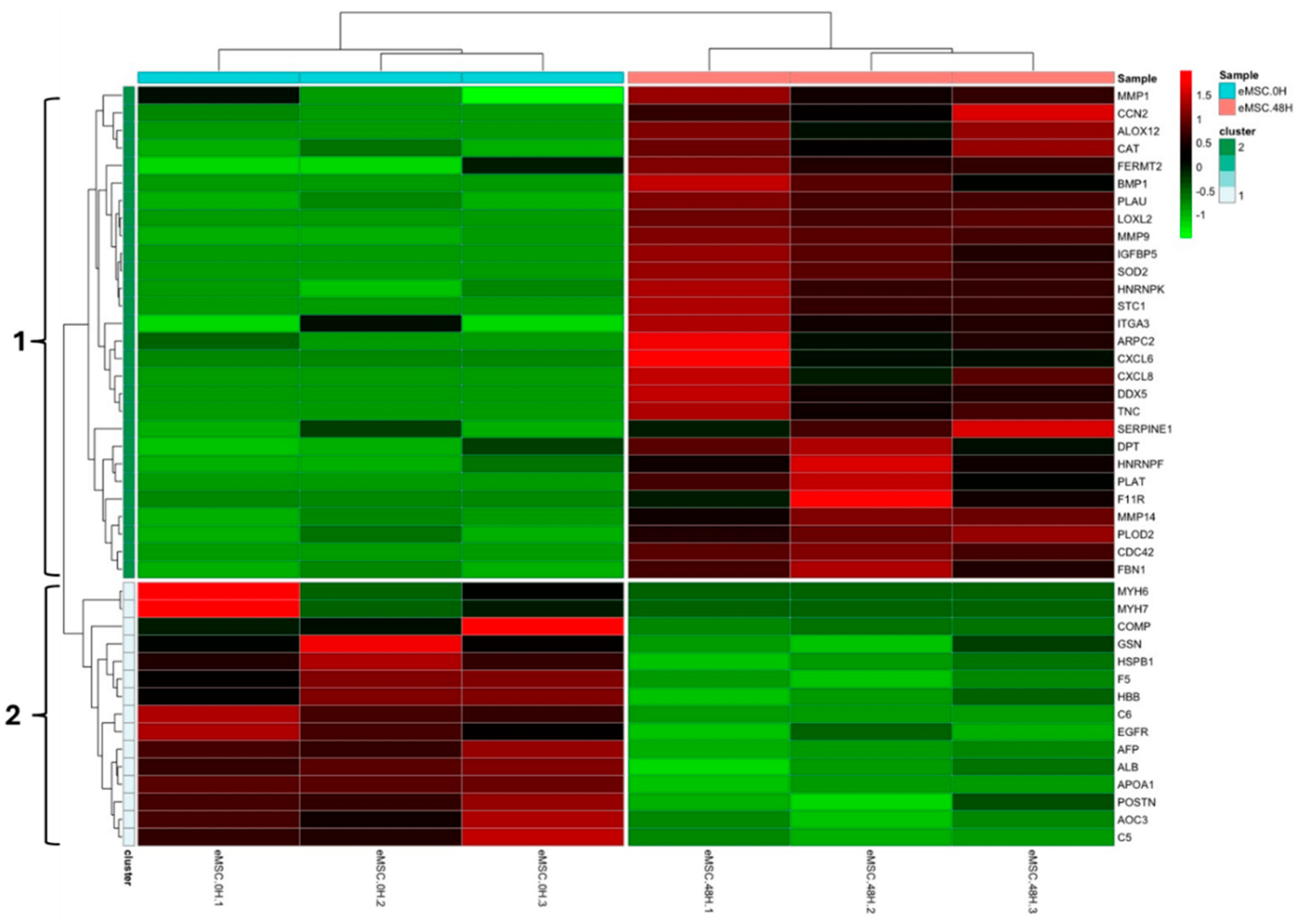

3.1. Experiment 1: Analysis of Differential Protein Abundance During Co-Culture of Myofibroblasts with PGE2-Preconditioned ET-eMSC

3.1.2. Gene Ontology and Reactome Pathways Enrichment of DAPs in the Secretome of ET-eMSC

3.1.2. Gene ontology and Reactome Pathways Enrichment of DAPs in the Myofibroblast

3.1.3. Enrichment Analysis of Fibrosis-Related Proteins in Myofibroblasts and Secretome of ET-eMSC

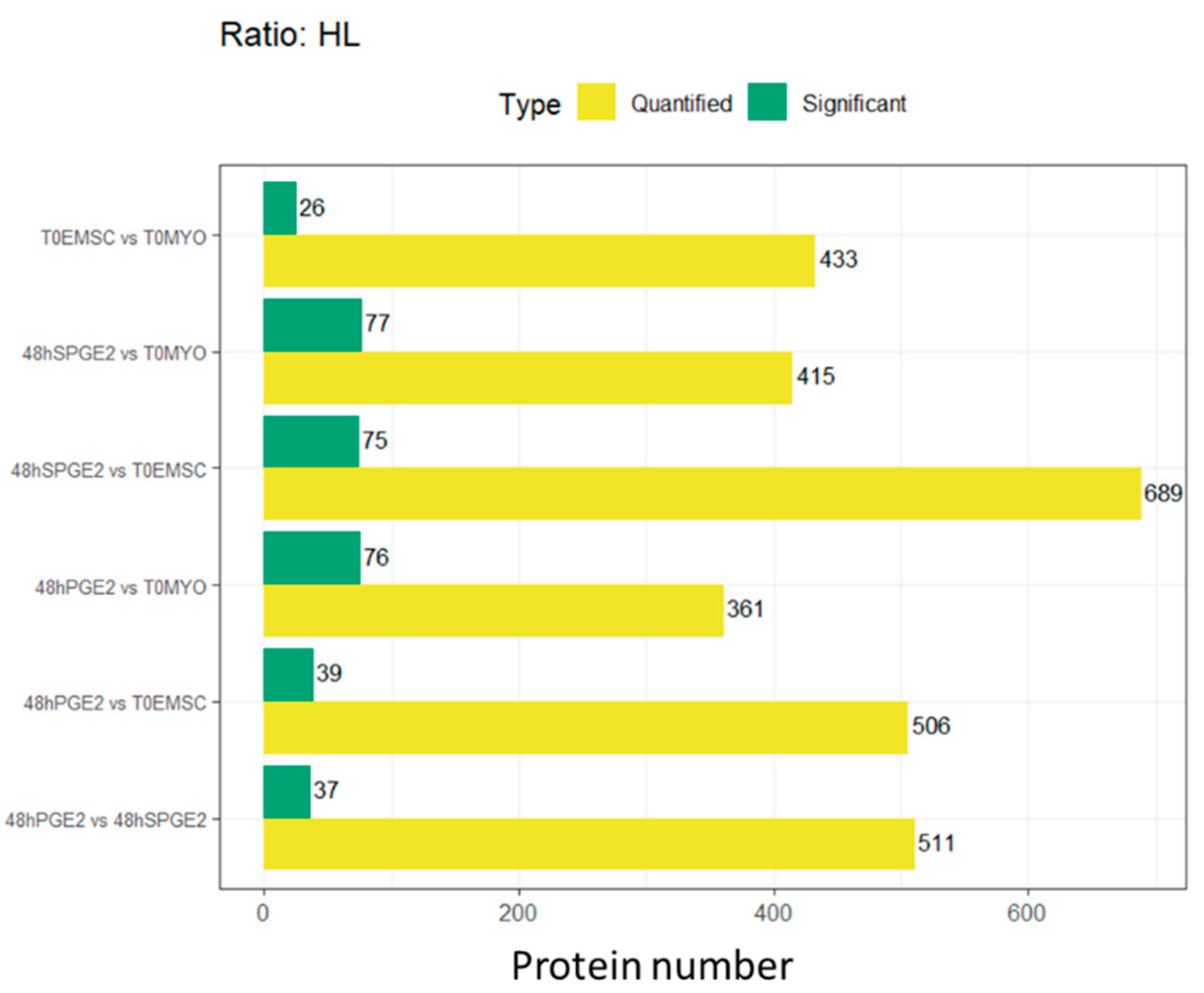

3.2. Experiment 2: SILAC Proteomic Analyses of Myofibroblasts Co-Cultured with Equine Endometrial-Derived MSCs (ET-eMSCs) Preconditioned with PGE₂ Reveal Bidirectional Interchange Transfer of Proteins

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 48hPGE₂ | 48 hours with PGE2 (contextual) |

| AAM | Antibiotic-Antimycotic Solution |

| Akt | Proteins Kinase B (PKB) |

| Arg | Arginine |

| ARPC2 | Arp2/3 complex 34 kDa subunit |

| AT-eMSCs | Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| AU-rich elements | Elementos ricos en adenina y uracilo |

| AUF1 | AU-rich element RNA-binding factor 1 (hnRNP D0) |

| BP | Biological Process |

| C5 | Complement component 5 |

| C6 | Complement component 6 |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| CC | Cellular Component |

| CCN1 | Cellular Communication Network Factor 1 |

| CCN2 | Cellular Communication Network Factor 2 |

| CCN2/CTGF | Cellular communication network factor 2 / Connective Tissue Growth Factor |

| CLU | Clusterin alpha chain |

| CO₂ | Dióxido de carbono |

| COL1A1 | Collagen type I alpha 1 |

| COL2A1 | Collagen type II alpha 1 |

| COL3A1 | Collagen type III alpha 1 |

| COL5A1 | Collagen type V alpha 1 |

| COL7A1 | Collagen type VII alpha 1 |

| COMP | Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein |

| COX-2/PTGS2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 / Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 |

| CTGF | Connective Tissue Growth Factor |

| CTSK | Cathepsin K |

| CXCL6 | C-X-C motif chemokine 6 |

| CXCL8 | C-X-C motif chemokine 8 |

| DAPs | Differentially Abundant Proteins |

| DMEM | Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium |

| DTT | Dithiothreitol |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| eMSC.0H | ET-eMSC preconditioned with PGE2 (contextual) |

| eMSC.48H | ET-eMSC after 48 hours of co-culture with myofibroblasts (contextual) |

| eMSCs | equine MSCs |

| EP₂ | Prostaglandin E₂ receptor subtype 2 |

| ER-to-Golgi | Endoplasmic Reticulum to Golgi |

| ET-eMSC | Equine endometrium-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| ET-eMSCs | Equine mesenchymal stem cells derived from endometrial tissue |

| ET-eMSCs | equine endometrial-derived MSCs |

| F11R | Junctional adhesion molecule A |

| F5 | Factor V |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| FC | Fold-Change |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| FERMT2 | FERM domain containing kindlin 2 |

| FOXO1 | Forkhead box protein O1 |

| FWHM | Full Width at Half Maximum |

| GJA1 | Gap junction protein |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| GSN | Gelsolin |

| h | hour(s) |

| H/L | Heavy/Light (ratio) |

| HEPES | 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid |

| hnRNP D0 | Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein D0 |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| IGF | Insulin-like Growth Factor |

| IGFBPs | IGF Binding Proteins |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| JAK/STAT | Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| JAK1 | Janus Kinase 1 |

| K0/R0 | Unlabeled lysine/arginine (SILAC labels) |

| K8/R10 | Lysine-8/Arginine-10 (SILAC labels) |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography Tandem-Mass Spectrometry |

| logFC | Logarithm of Fold Change |

| LOXL2 | Lysyl oxidase homolog 2 |

| LUM | Lumican |

| Lys | Lysine |

| m/z | Masa por carga (mass-to-charge ratio) |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MCL | Markov Clustering |

| MF | Molecular Function |

| MMP-1 | Matrix metalloproteinase--1 |

| MMP-14 | Matrix metalloproteinase -14 |

| MMP-2 | Matrix metalloproteinase -2 |

| MMP-9 | Matrix metalloproteinase -9 |

| MMP/TIMP | Matrix metalloproteinase /Tissue Inhibitor of metalloproteinases |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| mRNA | messenger RNA |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| MXR5 | Matrilysin 5 |

| MXR8 | Matrilysin 8 |

| MXRA5 | Matrix Remodeling Associated 5 |

| MXRA8 | Matrix Remodeling Associated 8 |

| MYO-ET-eMSC | Myofibroblasts co-cultured with ET-eMSCs (contextual) |

| Myo.0H | Myofibroblast samples at 0 hours (contextual) |

| Myo.48H | Myofibroblast samples at 48 hours (contextual) |

| NaCl | Cloruro de sodio |

| PAI-1/SERPINE1 | Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 / Serpin Family E Member 1 |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PDGF | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| PDGFRα | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha |

| PGE₂ | Prostaglandin E₂ |

| PI3K/AKT | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Protein Kinase B |

| PKA | ProteinKinase A |

| PLAT | Plasminogen activator, urokinase-type |

| PLAU | Urokinase-type plasminogen activator |

| PPI | Protein-ProteinInteraction |

| PPM | Parts per million |

| PTGIS | Prostacyclin synthase |

| PTGS2 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 |

| PTM | Post-Translational Modifications |

| Rho/ROCK | Rho-associated protein kinase |

| SGCA | Sarcoglycan alpha |

| SILAC | Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture |

| SPD | Samples per Day |

| sPGE₂ | Sin PGE₂ (referring to conditioned medium without PGE₂) (contextual) |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| T0EMSC | ET-eMSCs at time zero (contextual) |

| T0MYO | Myofibroblasts at time zero (contextual) |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-beta |

| THBS1 | Thrombospondin-1 |

| THBS2 | Thrombospondin 2 |

| TIMP-1 | Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-1 |

| TIMP-2 | Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-2 |

| TMM | Trimmed Mean of M-values |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| TriC/CCT | TCP-1 Ring Complex / Chaperonin Containing TCP-1 |

| uPA | Urokinase-type plasminogen activator |

| YAP/TAZ | Yes-associated protein/Transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif |

| α-SMA | α-smooth muscle actin |

| µL | microliters |

| μM | micromolar |

References

- Trundell, D.A. Mare Can Teach Us When Dealing. Endometriosis: Recent Advances, New Perspectives and Treatments, 2022; 133. [Google Scholar]

- Buczkowska, J.; Kozdrowski, R.; Nowak, M.; Raś, A.; Mrowiec, J. Endometrosis--Significance for Horse Reproduction, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Proposed Therapeutic Methods. Pol J Vet Sci 2014, 17, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, M.; Maeda, Y.; Oikawa, M.A. Histopathological Characteristics of Endometrosis in Thoroughbred Mares in Japan: Results from 50 Necropsy Cases. J Equine Sci 2014, 25, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.; Ellenberger, C.; Mattos, R.C.; Aupperle, H.; Dhein, S.; Stief, B.; Schoon, H.-A. The Equine Endometrosis: New Insights into the Pathogenesis. Anim Reprod Sci 2009, 111, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckes, B.; Zigrino, P.; Kessler, D.; Holtkotter, O.; Shephard, P.; Mauch, C.; Krieg, T. Fibroblast-Matrix Interactions in Wound Healing and Fibrosis. Matrix Biol 2000, 19, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Dias, G.; Rebordão, M.R.; Galvão, A.M.; Roberto-da-Costa, R.; Amaral, A.; Fernandes, C.; Pinto-Bravo, P.; Morazzo, S.; Alexandre-Pires, G.; Lukasik, K. What Goes Wrong from a Mare Healthy Endometrium to Endometrosis?; Springer, 2020; pp. 528–540.

- Rebordao, M.R.; Galvao, A.; Szostek, A.; Amaral, A.; Mateus, L.; Skarzynski, D.J.; Ferreira-Dias, G. Physiopathologic Mechanisms Involved in Mare Endometrosis. Reprod Domest Anim 2014, 49 Suppl 4, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerarduzzi, C.; Di Battista, J.A. Myofibroblast Repair Mechanisms Post-Inflammatory Response: A Fibrotic Perspective. Inflamm Res 2017, 66, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, B.; Phan, S.H.; Thannickal, V.J.; Galli, A.; Bochaton-Piallat, M.L.; Gabbiani, G. The Myofibroblast: One Function, Multiple Origins. Am J Pathol 2007, 170, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, A.V.; Humeres, C.; Frangogiannis, N.G. The Role of Alpha-Smooth Muscle Actin in Fibroblast-Mediated Matrix Contraction and Remodeling. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017, 1863, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.H.; McCue, P.M.; Aurich, C. Equine Endometritis: A Review of Challenges and New Approaches. Reproduction 2020, 160, R95–R110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mambelli, L.I.; Mattos, R.C.; Winter, G.H.; Madeiro, D.S.; Morais, B.P.; Malschitzky, E.; Miglino, M.A.; Kerkis, A.; Kerkis, I. Changes in Expression Pattern of Selected Endometrial Proteins Following Mesenchymal Stem Cells Infusion in Mares with Endometrosis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mambelli, L.I.; Winter, G.H.; Kerkis, A.; Malschitzky, E.; Mattos, R.C.; Kerkis, I. A Novel Strategy of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Delivery in the Uterus of Mares with Endometrosis. Theriogenology 2013, 79, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezakhani, L.; Kelishadrokhi, A.F.; Soleimanizadeh, A.; Rahmati, S. Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC)-Derived Exosomes as a Cell-Free Therapy for Patients Infected with COVID-19: Real Opportunities and Range of Promises. Chemistry and physics of lipids 2021, 234, 105009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, C.; Strillacci, M.G.; Bagnato, A.; Esposti, P.; Marini, M.G.; Corradetti, B.; Bizzaro, D.; Idda, A.; Ledda, S.; Capra, E.; et al. Microvesicles Secreted from Equine Amniotic-Derived Cells and Their Potential Role in Reducing Inflammation in Endometrial Cells in an in-Vitro Model. Stem Cell Res Ther 2016, 7, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, J.; Rojas, D.; Wong, Y.; Telleria, F.; Manriquez, J.; Mancanares, A.C.F.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L.L.; Castro, F.O. In Vitro Preconditioning of Equine Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Prostaglandin E(2), Substance P and Their Combination Changes the Cellular protein Secretomics and Improves Their Immunomodulatory Competence without Compromising Stemness. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2020, 228, 110100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, F.; Saravia, F.; Cisterna, G.; Rojas, F.; Silva, P.P.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L.; Rojas, D.; Cabezas, J.; Mancanares, A.C.F.; Castro, F.O. Assessment of the Anti-Inflammatory and Engraftment Potential of Horse Endometrial and Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells in an in Vivo Model of Post Breeding Induced Endometritis. Theriogenology 2020, 155, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.S.; Mancanares, A.C.; Navarrete, F.; Poblete, P.; Mendez-Perez, L.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L.; Castro, F.O. Short Preconditioning with TGFbeta of Equine Adipose Tissue-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Predisposes towards an Anti-Fibrotic Secretory Phenotype: A Possible Tool for Treatment of Endometrosis in Mares. Theriogenology 2024, 225, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.S.; Mancanares, A.C.; Navarrete, F.I.; Poblete, P.M.; Mendez-Perez, L.; Ferreira-Dias, G.M.L.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L.; Castro, F.O. Mare Stromal Endometrial Cells Differentially Modulate Inflammation Depending on Oestrus Cycle Status: An in Vitro Study. Front Vet Sci 2023, 10, 1271240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas Salazar, J.G. Pre-Condicionamiento in Vitro de Células Madre Mesenquimales Derivadas de Tejido Adiposo Equino, Como Herramienta Para Potenciar La Adquisición de Una Mayor Capacidad Inmunomoduladora. 2018.

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.; Horwitz, E. Minimal Criteria for Defining Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy Position Statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranera, B.; Lyahyai, J.; Romero, A.; Vazquez, F.J.; Remacha, A.R.; Bernal, M.L.; Zaragoza, P.; Rodellar, C.; Martin-Burriel, I. Immunophenotype and Gene Expression Profiles of Cell Surface Markers of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Equine Bone Marrow and Adipose Tissue. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2011, 144, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M. Functional and Quantitative Proteomics Using SILAC. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2006, 7, 952–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kani, K. Quantitative Proteomics Using SILAC. In Proteomics: Methods and Protocols; Comai, L., Katz, J.E., Mallick, P., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2017; pp. 171–184. ISBN 978-1-4939-6747-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas, J.; Rojas, D.; Wong, Y.; Telleria, F.; Manriquez, J.; Mançanares, A.C.F.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L.L.; Castro, F.O. In Vitro Preconditioning of Equine Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cells with Prostaglandin E2, Substance P and Their Combination Changes the Cellular Protein Secretomics and Improves Their Immunomodulatory Competence without Compromising Stemness. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2020, 228, 110100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, F.; Wong, Y.S.; Cabezas, J.; Riadi, G.; Manriquez, J.; Rojas, D.; Furlanetto Mancanares, A.C.; Rodriguez-Alvarez, L.; Saravia, F.; Castro, F.O. Distinctive Cellular Transcriptomic Signature and MicroRNA Cargo of Extracellular Vesicles of Horse Adipose and Endometrial Mesenchymal Stem Cells from the Same Donors. Cell Reprogram 2020, 22, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S. The STRING Database in 2023: Protein–Protein Association Networks and Functional Enrichment Analyses for Any Sequenced Genome of Interest. Nucleic acids research 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biernacka, A.; Dobaczewski, M.; Frangogiannis, N.G. TGF-β Signaling in Fibrosis. Growth Factors 2011, 29, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangogiannis, N. Transforming Growth Factor-β in Tissue Fibrosis. J Exp Med 2020, 217, e20190103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, F.S.; Cruz-Soca, M.; Bock-Pereda, A.; Faundez-Contreras, J.; Gutiérrez-Rojas, C.; Gandin, A.; Torresan, V.; Casar, J.C.; Ravasio, A.; Brandan, E. Role of TGF-β/SMAD/YAP/TAZ Signaling in Skeletal Muscle Fibrosis. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2025, 328, C1015–C1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpoim-Moreira, J.; Fernandes, C.; Rebordão, M.R.; Costa, A.L.; Bliebernicht, M.; Nunes, T.; Szóstek-Mioduchowska, A.; Skarzynski, D.J.; Ferreira-Dias, G. Collagen Type III as a Possible Blood Biomarker of Fibrosis in Equine Endometrium. Animals 2022, 12, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlers, D.; Brenmoehl, J.; Löffler, I.; Müller, C.K.; Leipner, C.; Schultze-Mosgau, S.; Stallmach, A.; Kinne, R.W.; Wolf, G. TGF-β and Fibrosis in Different Organs—Molecular Pathway Imprints. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2009, 1792, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallée, A.; Lecarpentier, Y. TGF-β in Fibrosis by Acting as a Conductor for Contractile Properties of Myofibroblasts. Cell & bioscience 2019, 9, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Aresu, L.; Benali, S.; Giannuzzi, D.; Mantovani, R.; Castagnaro, M.; Falomo, M.E. The Role of Inflammation and Matrix Metalloproteases in Equine Endometriosis. J Vet Sci 2012, 13, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno, L.A.M.; Bastos, H.B.A.; Bueno, V.L.C.; Trentin, J.M.; Fiorenza, M.; Panziera, W.; Winter, G.H.Z.; Kretzmann, N.A.; Fiala-Rechsteiner, S.; Mattos, R.C.; et al. Collagen and Collagenases in Mare’s Endometrium with Endometrosis. Theriogenology 2024, 230, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giantin, M.; Aresu, L.; Benali, S.; Aricò, A.; Morello, E.M.; Martano, M.; Vascellari, M.; Castagnaro, M.; Lopparelli, R.M.; Zancanella, V.; et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases and vascular endothelial growth factor in canine mast cell tumours. J Comp Pathol 2012, 147, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddsdóttir, C. Development of Endometrial Fibrosis in the Mare: Factors Involved in Tissue Remodelling and Collagen Deposition. 2008.

- Szostek-Mioduchowska, A.Z.; Baclawska, A.; Okuda, K.; Skarzynski, D.J. Effect of Proinflammatory Cytokines on Endometrial Collagen and Metallopeptidase Expression during the Course of Equine Endometrosis. Cytokine 2019, 123, 154767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisberg, M.; Kalluri, R. Cellular Mechanisms of Tissue Fibrosis. 1. Common and Organ-Specific Mechanisms Associated with Tissue Fibrosis. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2013, 304, C216–C225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohani, M.G.; Parks, W.C. Matrix Remodeling by MMPs during Wound Repair. Matrix biology 2015, 44, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R.K.; Varshney, A.K.; Yadava, P.K. Diversity and Functional Evolution of the Plasminogen Activator System. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 98, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillen, M.; Declerck, P.J. A Narrative Review on Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 and Its (Patho) Physiological Role: To Target or Not to Target? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Espinosa, A.M.; Link, P.A.; Sicard, D.; Jorba, I.; Tschumperlin, D.J.; Haak, A.J. Dopamine D1 Receptor Stimulates Cathepsin K-Dependent Degradation and Resorption of Collagen I in Lung Fibroblasts. Journal of Cell Science 2020, 133, jcs248278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, S.; Smith, L.; Fields, G.B. Matrix Metalloproteases Collagenolysis in Health and Disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research 2017, 1864, 1940–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, G.; Huang, S.K.; Okunishi, K.; Scott, J.P.; Kumar Penke, L.R.; Scruggs, A.M.; Peters-Golden, M. Reversal of Myofibroblast Differentiation by Prostaglandin E(2). Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2013, 48, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wipff, P.J.; Rifkin, D.B.; Meister, J.J.; Hinz, B. Myofibroblast Contraction Activates Latent TGF-Beta1 from the Extracellular Matrix. J Cell Biol 2007, 179, 1311–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lei, D.; Swindell, W.R.; Xia, W.; Weng, S.; Fu, J.; Worthen, C.A.; Okubo, T.; Johnston, A.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; et al. Age-Associated Increase in Skin Fibroblast–Derived Prostaglandin E2 Contributes to Reduced Collagen Levels in Elderly Human Skin. J Invest Dermatol 2015, 135, 2181–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Shu, B.; Chen, L.; Tang, J.; Zhang, L.; Xie, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Qi, S. Prostaglandin E2 Inhibits Collagen Synthesis in Dermal Fibroblasts and Prevents Hypertrophic Scar Formation in Vivo. Exp Dermatol 2016, 25, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cilli, F.; Khan, M.; Fu, F.; Wang, J.H.-C. Prostaglandin E2 Affects Proliferation and Collagen Synthesis by Human Patellar Tendon Fibroblasts. Clinical journal of sport medicine 2004, 14, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, A.; Rojas, M.; Vallejos, A.; Villegas, V.; Perez, L.; Cabello-Verrugio, C.; Simon, F. Endothelial Fibrosis Induced by Suppressed STAT3 Expression Mediated by Signaling Involving the TGF-Beta1/ALK5/Smad Pathway. Lab Invest 2017, 97, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Qi, Y.-F.; Yu, Y.-R. STAT3: A Key Regulator in Liver Fibrosis. Annals of hepatology 2021, 21, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.J.; Kim, S.-J.; Hahn, Y.-I.; Yoon, H.-J.; Han, B.; Kim, K.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.P.; Suh, Y.G.; Na, H.-K.; et al. 15-Keto Prostaglandin E2 Suppresses STAT3 Signaling and Inhibits Breast Cancer Cell Growth and Progression. Redox Biol 2019, 23, 101175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.X.; Sun, J.X.; Ling, J.J.; Lv, J.H.; Zhu, D.Y.; Chen, Q.; Sun, Y.J.; Han, X. Prostaglandin E 2 Regulates Foxo Activity via the Akt Pathway: Implications for Pancreatic Islet Beta Cell Dysfunction. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2959–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naini, S.M.; Choukroun, G.J.; Ryan, J.R.; Hentschel, D.M.; Shah, J.V.; Bonventre, J.V. Cytosolic Phospholipase A2α Regulates G1 Progression through Modulating FOXO1 Activity. FASEB J 2016, 30, 1155–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Ma, Z.; Hu, W.; Jiang, S.; Yang, Z.; Li, T.; Chen, F.; Jia, G.; Yang, Y. FOXO1/3: Potential Suppressors of Fibrosis. Ageing research reviews 2018, 41, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Luo, F. The Role of JAK/STAT Pathway in Fibrotic Diseases: Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozyk, P.D.; Moore, B.B. Prostaglandin E2 and the Pathogenesis of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2011, 45, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rixon, C.; Andreassen, K.; Shen, X.; Erusappan, P.M.; Almaas, V.M.; Palmero, S.; Dahl, C.P.; Ueland, T.; Sjaastad, I.; Louch, W.E.; et al. Lumican Accumulates with Fibrillar Collagen in Fibrosis in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. ESC Heart Fail 2023, 10, 858–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamov, D.R.; Müller, A.; Wegrowski, Y.; Brezillon, S.; Franz, C.M. Quantitative Analysis of Type I Collagen Fibril Regulation by Lumican and Decorin Using AFM. J Struct Biol 2013, 183, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetwyne, M.T.; Murphy-Ullrich, J.E. Thrombospondin1 in Tissue Repair and Fibrosis: TGF-β-Dependent and Independent Mechanisms. Matrix Biol 2012, 31, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaqour, B. Caught between a “Rho” and a Hard Place: Are CCN1/CYR61 and CCN2/CTGF the Arbiters of Microvascular Stiffness? Journal of Cell Communication and Signaling 2020, 14, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Liu, N.; Bao, C.L.; Yang, D.Z.; Ma, G.X.; Yi, W.H.; Xiao, G.Z.; Cao, H.L. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Fibrotic Diseases-the Two Sides of the Same Coin. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2023, 44, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, W.I.; Nagano, T. Connective Tissue Growth Factor in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Breaking the Bridge. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, S.; Takigawa, M. Cellular and Molecular Actions of CCN2/CTGF and Its Role under Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Clinical Science 2014, 128, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, K.L.; Coustry, F.; Hecht, J.T. Cartilage Oligomeric Matrix Protein: COMPopathies and Beyond. Matrix biology 2018, 71–72, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, B.; Wei, S. The Role of Periostin in Cardiac Fibrosis. Heart Failure Reviews 2024, 29, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y. Periostin in Skin Tissue and Skin-Related Diseases. Allergology International 2014, 63, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Wang, W.; Morales-Nebreda, L.; Feng, G.; Wu, M.; Zhou, X.; Lafyatis, R.; Lee, J.; Hinchcliff, M.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.; et al. Tenascin-C Drives Persistence of Organ Fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanaka-Yoshida, K.; Aoki, H. Tenascin-C and Mechanotransduction in the Development and Diseases of Cardiovascular System. Front Physiol 2014, 5, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathaur, P.; Rodriguez, J.; Kuchtey, J.; Insignares, S.; Jones, W.B.; Kuchtey, R.W.; Bassnett, S. The Biomechanics of Fibrillin Microfibrils: Lessons from the Ciliary Zonule. Cells 2024, 13, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.; Okamoto, O.; Wu, W.; Matsuo, N.; Kumai, J.; Yamada, Y.; Katagiri, F.; Nomizu, M.; Fujiwara, S. Identification of Fibronectin Binding Sites in Dermatopontin and Their Biological Function. Journal of Dermatological Science 2014, 76, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannandrea, M.; Parks, W.C. Diverse Functions of Matrix Metalloproteases during Fibrosis. Dis Model Mech 2014, 7, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Vaughan, D.E. PAI-1 in Tissue Fibrosis. J Cell Physiol 2012, 227, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.-L.; Yang, H.-X.; Liu, Q.-P.; Rahman, K.; Zhang, H. CXCL6: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Inflammation and Cancer. Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2023, 23, 4413–4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, A.J.; Kim, D.; Lu, M.; Farina, M.; Bowman, R.L.; Yang, J.L.; Park, Y.; Karzai, A.; Xiao, W.; Zaroogian, Z.; et al. CXCL8/CXCR2 Signaling Mediates Bone Marrow Fibrosis and Is a Therapeutic Target in Myelofibrosis. Blood 2023, 141, 2508–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, J. The Functions of Thrombospondin-1 and-2. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2000, 12, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, A.; Chen, M.; Ye, Z. Identification of Matrix-Remodeling Associated 5 as a Possible Molecular Oncotarget of Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Death & Disease 2023, 14, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda, J.; Sanz, A.B.; Fernandez-Fernandez, B.; Carrasco, S.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Cannata-Ortiz, P.; Ortiz, A.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D. MXRA 5 Is a TGF-β1-regulated Human protein with Anti-inflammatory and Anti-fibrotic Properties. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharaee-Kermani, M.; Kasina, S.; Moore, B.B.; Thomas, D.; Mehra, R.; Macoska, J.A. CXC-Type Chemokines Promote Myofibroblast Phenoconversion and Prostatic Fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebschull, M.; Demmer, R.; Behle, J.H.; Pollreisz, A.; Heidemann, J.; Belusko, P.B.; Celenti, R.; Pavlidis, P.; Papapanou, P.N. Granulocyte Chemotactic Protein 2 (Gcp-2/Cxcl6) Complements Interleukin-8 in Periodontal Disease. Journal of periodontal research 2009, 44, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.B.-S.; Kress, S.; Castro, L.; Sheppard, A.; Raghunath, M. Cellular Re- and de-Programming by Microenvironmental Memory: Why Short TGF-Β1 Pulses Can Have Long Effects. Fibrogenesis & Tissue Repair 2013, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Secretome Experiment 1 (abundance) | Secretome Experiment 2 (identification in donor samples) | Origen cell | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene name | Secretome 48 hours vs 0 hours | 48H PGE2 | 48H SPGE2 | T0MSC | T0MYO | |

| MMP1 | high abundance | + | + | + | + | both |

| MMP2 | Equal | + | + | + | + | both |

| MMP9 | high abundance | + | + | + | + | both |

| MMP14 | high abundance | + | + | - | + | both |

| TIMP1 | Equal | + | + | + | + | both |

| TIMP2 | Equal | + | + | + | + | both |

| MXRA5 | high abundance | + | + | - | + | both |

| MXRA8 | high abundance | + | + | - | - | ET-eMSC |

| CXCL6 | high abundance | + | + | - | + | MYO |

| CXCL8 | high abundance | + | + | - | - | both |

| C-C motif chemokine | Equal | + | + | - | + | MYO |

| HMGB1 | Equal | + | + | - | - | both |

| THBS 1 | Equal | + | + | + | + | both |

| THBS 2 | Equal | + | + | + | + | both |

| PLAU | high abundance | + | + | + | + | both |

| SERPINE 1 | high abundance | + | + | + | + | both |

| CCN2/CTGF | high abundance | - | + | - | + | both |

| TGF β1 | Equal | - | + | - | - | both |

| INHBA | high abundance | + | + | - | + | both |

| PCOLCE | high abundance | + | + | + | + | both |

| PCOLCE2 | Equal | + | + | + | + | both |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).