Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

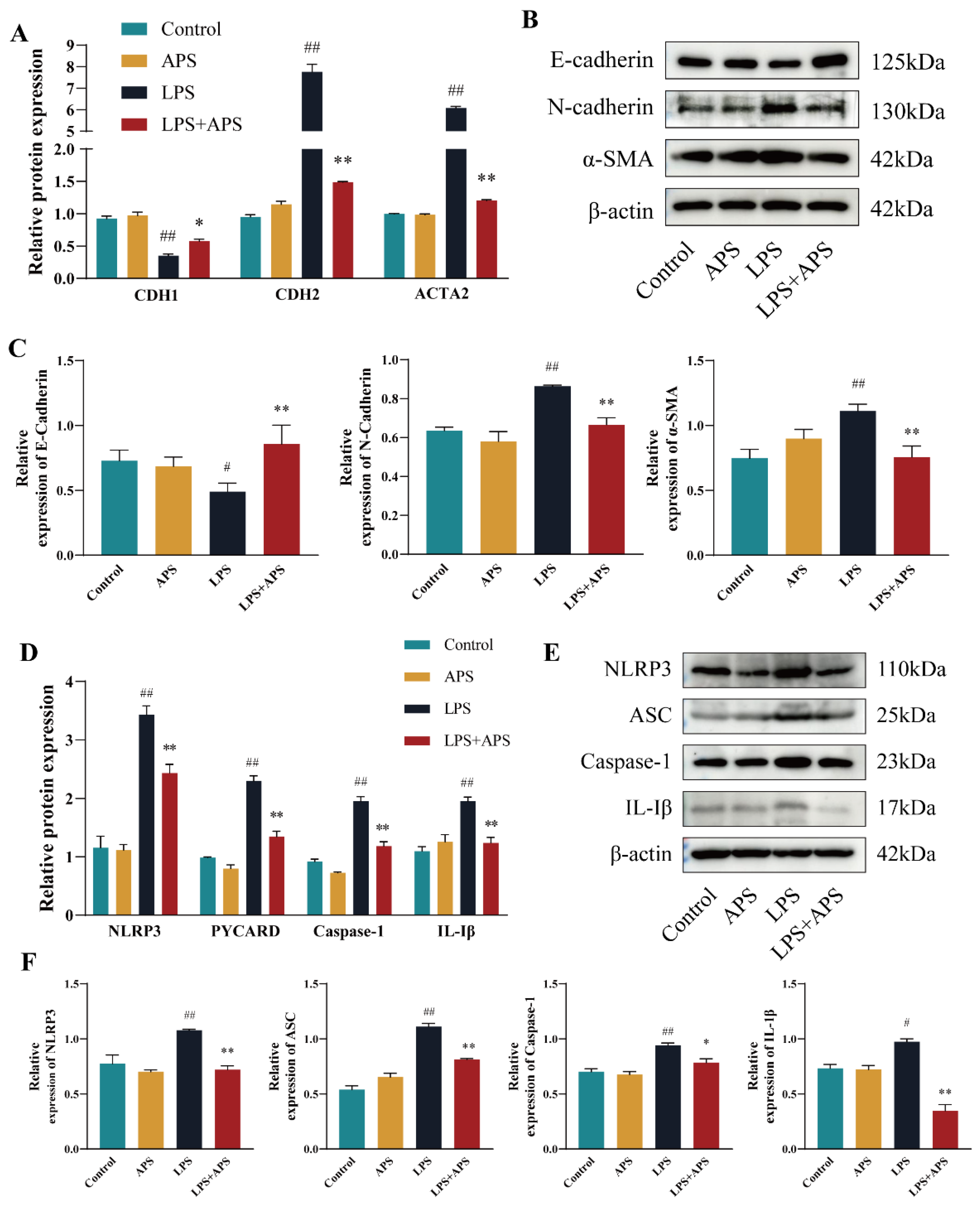

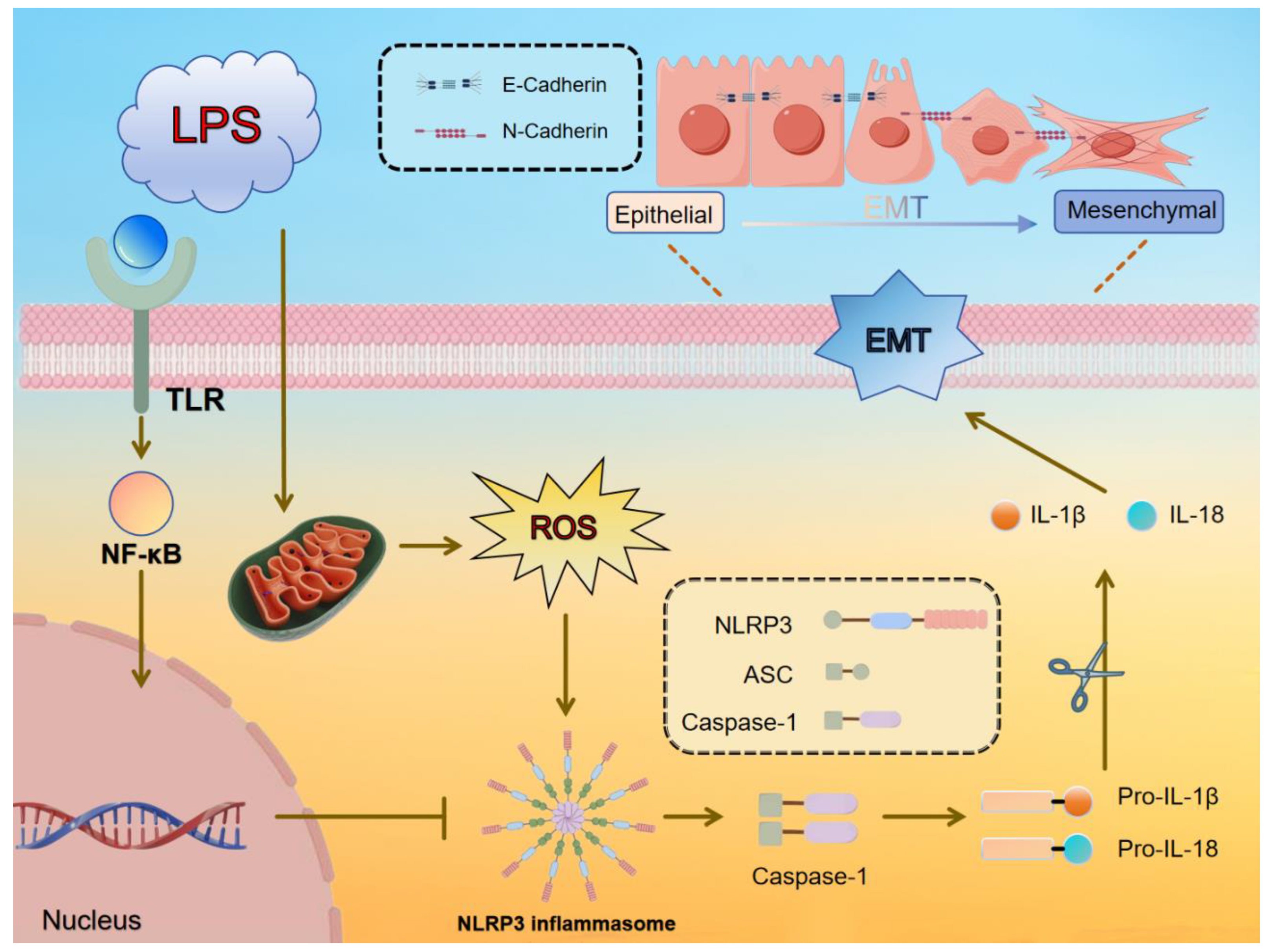

Mastitis in dairy cows, typically caused by bacterial infection, is a common inflammatory condition of the mammary tissue that leads to fibrosis, adversely affecting cow health, milk production, and dairy product quality. Astragalus polysaccharide (APS) has shown effectiveness in alleviating inflammation and fibrosis in various organs. In this study, a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced fibrosis model was established using a bovine mammary epithelial cell line (MAC-T) and Kunming rats. Key parameters, including relative gene mRNA expression, protein levels, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) content, were assessed using RT-qPCR, Western blotting (WB), and DCFH-DA techniques, while histological analysis of breast tissue was performed using H&E and Masson trichrome staining. Oxidative stress markers, such as malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration and enzymatic activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT), were also evaluated in mouse mammary glands. APS treatment modulated fibrosis markers (E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and α-SMA) and inflammation markers (NLRP3, ASC, Caspase-1, and IL-1β) at both mRNA and protein levels, significantly reduced ROS concentrations (P<0.01), restored oxidative stress balance in mice (P<0.05), and mitigated fibrosis and inflammation, as revealed by histological observations. These findings demonstrate that APS can mitigate ROS accumulation, reduce inflammation, and inhibit epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in vitro and mammary fibrosis in vivo, supporting its potential as an alternative therapeutic agent for mammary fibrosis treatment.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. APS Inhibits LPS-Induced EMT Studies in MAC-T Cells

2.2. Inhibition of ROS Production by APS Alleviates LPS-Induced EMT in MAC-T Cells

2.3. APS Alleviates EMT Progression in MAC-T Cells by Inhibiting NLRP3 Signaling

2.4. APS Inhibition of Mammary ROS and EMT Study in Mice

2.5. APS Attenuated Mouse Mammary Fibrosis Triggered by NLRP3 Activation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Samples

4.2. Animal Samples

4.3. RT-qPCR

4.4. Western Blot

4.5. Determination of Mitochondrial ROS Levels

4.6. H&E and Masson Staining

4.7. Detection of Mammary Gland Oxidative Stress Levels

4.8. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Magro, G.; Biffani, S.; Minozzi, G.; Ehricht, R.; Monecke, S.; Luini, M.; Piccinini, R. Virulence Genes of S. aureus from Dairy Cow Mastitis and Contagiousness Risk. Toxins 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Ding, Y.; Bi, Y.; Chen, M.; Cao, X.; Wang, F. Staphylococcus aureus on the effect of expression of MMPs/TIMPs and uPA system in bovine mammary fibroblasts. Journal of microbiology, immunology, and infection = Wei mian yu gan ran za zhi 2021, 54, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, X.; Hu, G.; Liu, Y.; Xu, P.; Huang, Y.; Cai, X.; Guo, W.; Fu, S.; Liu, J. Mammary Fibrosis Tendency and Mitochondrial Adaptability in Dairy Cows with Mastitis. Metabolites 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisto, M.; Ribatti, D.; Lisi, S. Organ Fibrosis and Autoimmunity: The Role of Inflammation in TGFβ-Dependent EMT. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Kenawi, A.; Ruffell, B. Inflammation, ROS, and Mutagenesis. Cancer cell 2017, 32, 727–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Feng, D.; Zhao, H.; Lin, M.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Lv, L.; Gao, Z.; Zhai, X.; et al. p66Shc Contributes to Liver Fibrosis through the Regulation of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species. Theranostics 2019, 9, 1510–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez, F.J.; Chandel, N.S.; Jain, M.; Budinger, G.R.S. Reactive oxygen species as signaling molecules in the development of lung fibrosis. Translational research : the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine 2017, 190, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, F.; Li, N.; Kong, M.; Wu, J.; Fan, Z.; Miao, D.; Xu, Y.; Ye, Q.; Wang, Y. CDKN2a/p16 Antagonizes Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Liver Fibrosis by Modulating ROS Levels. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2020, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Xiong, Z.; Song, A.; Lei, C.; Ye, C.; Su, H.; Zhang, C. UCP1 alleviates renal interstitial fibrosis progression through oxidative stress pathway mediated by SIRT3 protein stability. Journal of translational medicine 2023, 21, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ding, H.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, W.; Mei, Y.; Zhang, R. Alarin alleviated cardiac fibrosis via attenuating oxidative stress in heart failure rats. Amino acids 2021, 53, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, A.; Li, B.; Kombe, A.J.K.; Jin, T.; Tao, J. Pharmacological Inhibitors of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, E.I.; Sutterwala, F.S. Initiation and perpetuation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and assembly. Immunological reviews 2015, 265, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Li, J.C.; Lai, J. Astragalus polysaccharide: a review of its immunomodulatory effect. Archives of pharmacal research 2022, 45, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Han, X.; Li, Q.; Sun, L.; Wang, J. Iguratimod ameliorates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting the EMT process and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie 2022, 153, 113460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shergis, J.L.; Yang, L.; Zhang, A.L.; Guo, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, S.; Zeng, L.; Mao, W.; Xue, C.C. Astragalus membranaceus (Huang Qi) as adjunctive therapy for diabetic kidney disease: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2019, 239, 111921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.; Jerng, U.; Lee, S. A systematic review of anticancer effects of radix astragali. Chinese journal of integrative medicine 2016, 22, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Niu, J.; Wang, Z.; Xu, W.; Qiao, Z.; Gu, Y. Astragalus embranaceus extract activates immune response in macrophages via heparanase. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2012, 17, 7232–7240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yang, J.; Bai, W.L.; Ji, W.Y. Antitumor and immunoregulatory effects of astragalus on nasopharyngeal carcinoma in vivo and in vitro. Phytotherapy research : PTR 2011, 25, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shen, J.; Li, S.; Zhi, L.; Yang, X.; Yao, J. Sulfated Astragalus polysaccharide regulates the inflammatory reaction in LPS-infected broiler chicks. International journal of biological macromolecules 2014, 69, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Yao, J. Astragalus polysaccharide reduces inflammatory response by decreasing permeability of LPS-infected Caco2 cells. International journal of biological macromolecules 2013, 61, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, Y.; Xu, Q.; Liu, S.; Li, H.; Cheng, K.; Yuan, J.; Liu, H.; Zhu, P. Astragalus polysaccharide alleviates alcoholic-induced hepatic fibrosis by inhibiting polymerase I and transcript release factor and the TLR4/JNK/NF-κB/MyD88 pathway. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2023, 314, 116662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, C.; Zhao, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, L.; Chen, Q.; Jiang, H.; Gao, X.; Lv, X.; Zhi, X.; Wu, X.; et al. Research progress of natural medicine Astragalus mongholicus Bunge in treatment of myocardial fibrosis. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2023, 305, 116128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Fu, X. Hedysarum polybotrys polysaccharide attenuates renal inflammatory infiltration and fibrosis in diabetic mice by inhibiting the HMGB1/RAGE/TLR4 pathway. Experimental and therapeutic medicine 2023, 26, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.; Xu, P.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Wu, L.; Chen, Y.; Teng, L.; Wang, D. Investigation on the immunomodulatory activities of Sarcodon imbricatus extracts in a cyclophosphamide (CTX)-induced immunosuppressanted mouse model. Saudi pharmaceutical journal : SPJ : the official publication of the Saudi Pharmaceutical Society 2017, 25, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; Long, T.; Zhou, L.; Bao, Y. Immunomodulatory effects of herbal formula of astragalus polysaccharide (APS) and polysaccharopeptide (PSP) in mice with lung cancer. International journal of biological macromolecules 2018, 106, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakrashi, A.; Ryan, C.; Guéret, C.; Berry, D.P.; Corcoran, M.; Keane, M.T.; Mac Namee, B. Early detection of subclinical mastitis in lactating dairy cows using cow-level features. Journal of dairy science 2023, 106, 4978–4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, B.; Dong, J.; Viswanathan, S.; Widjaja, A.A.; Paleja, B.S.; Adami, E.; Ko, N.S.J.; Wang, M.; Lim, S.; Tan, J.; et al. Fibroblast-specific IL11 signaling drives chronic inflammation in murine fibrotic lung disease. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2020, 34, 11802–11815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Figueiredo, J.; De Angelis, S.P.; Corso, F.; Girardi, A.; Pereira, J.; Seruca, R.; Bonanni, B.; Carneiro, P.; Pravettoni, G.; et al. E-cadherin deregulation in breast cancer. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2020, 24, 5930–5936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Shen, J.; Zhao, L.; Hao, Q.; Yang, Y. Curcumin Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-Activated Neuroinflammation via Modulation of miR-199b-5p/IκB Kinase β (IKKβ)/Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB) Pathway in Microglia. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research 2019, 25, 9801–9810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuwaki, T.; Shionoya, K.; Ihnatko, R.; Eskilsson, A.; Kakuta, S.; Dufour, S.; Schwaninger, M.; Waisman, A.; Müller, W.; Pinteaux, E.; et al. Involvement of interleukin-1 type 1 receptors in lipopolysaccharide-induced sickness responses. Brain, behavior, and immunity 2017, 66, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Xiao, L. Ginsenoside Rg1 Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Fibrosis of Endometrial Epithelial Cells in Dairy Cows by Inhibiting Reactive Oxygen Species-Activated NLRP3. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, D.; Ouyang, G.; Liu, Y.; Cui, D. Periostin deficiency attenuates lipopolysaccharide- and obesity-induced adipose tissue fibrosis. FEBS letters 2021, 595, 2099–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Ma, L.T.; Ren, Q.Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, H.J.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.H.; Dou, Y.Q.; Li, S.D.; et al. The influence of astragalus polysaccharide and β-elemene on LX-2 cell growth, apoptosis and activation. BMC gastroenterology 2014, 14, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Liang, H.; Yan, X.; Liang, Q.; Bai, Z.; Xie, T.; Dai, J.; Zhao, X.; Xiao, Y. Astragalus polysaccharide promotes autophagy and alleviates diabetic nephropathy by targeting the lncRNA Gm41268/PRLR pathway. Renal failure 2023, 45, 2284211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qin, L.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, H.; Zhu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, B.; Li, F.; et al. Astragalus polysaccharide attenuates LPS-related inflammatory osteolysis by suppressing osteoclastogenesis by reducing the MAPK signalling pathway. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2021, 25, 6800–6814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Tang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Wan, M.; Yu, M.; Chen, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, R.; Ge, M. Astragalus Polysaccharide Protects Against Cadmium-Induced Autophagy Injury Through Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Pathway in Chicken Embryo Fibroblast. Biological trace element research 2022, 200, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiological reviews 2014, 94, 909–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, C.R. Oxidative Stress and Hepatic Stellate Cells: A PARADOXICAL RELATIONSHIP. Trends in cell & molecular biology 2012, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y.N.; Wang, G.H.; Zhou, F.; Hao, J.J.; Tian, L.; Guan, L.F.; Geng, X.K.; Ding, Y.C.; Wu, H.W.; Zhang, K.Z. PM2.5 induces liver fibrosis via triggering ROS-mediated mitophagy. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety 2019, 167, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Jabeen, F.; Aslam, N.; Manan, M. Anti-EMT properties of ergothioneine attenuate lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative stress-mediated acute lung injury via modulating TGF-β/smad/snail signaling pathway. Human & experimental toxicology 2023, 42, 9603271231178015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbichler, T.B.; Dudas, J.; Ingruber, J.; Glueckert, R.; Sprung, S.; Fleischer, F.; Cidlinsky, N.; Dejaco, D.; Kofler, B.; Giotakis, A.I.; et al. Slug Is A Surrogate Marker of Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in Head and Neck Cancer. Journal of clinical medicine 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.S.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, D.Y.; Kang, S.G.; Jin, W. MEST induces Twist-1-mediated EMT through STAT3 activation in breast cancers. Cell death and differentiation 2019, 26, 2594–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcoran, S.E.; Halai, R.; Cooper, M.A. Pharmacological Inhibition of the Nod-Like Receptor Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 Inflammasome with MCC950. Pharmacological reviews 2021, 73, 968–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Li, K. The selective NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 alleviates cholestatic liver injury and fibrosis in mice. International immunopharmacology 2019, 70, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Shi, H.; Chang, S.; Gao, Y.; Li, X.; Lv, C.; Yang, H.; Xiang, H.; Yang, J.; Xu, L.; et al. The selective NLRP3-inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 reduces myocardial fibrosis and improves cardiac remodeling in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. International immunopharmacology 2019, 74, 105575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig-Portugall, I.; Bartok, E.; Dhana, E.; Evers, B.D.; Primiano, M.J.; Hall, J.P.; Franklin, B.S.; Knolle, P.A.; Hornung, V.; Hartmann, G.; et al. An NLRP3-specific inflammasome inhibitor attenuates crystal-induced kidney fibrosis in mice. Kidney international 2016, 90, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Sun, J.; Huang, L.; Yu, M.; Meng, X.; Shan, Y.; Dai, H.; Wang, F.; Shi, J.; Sheng, M. Astragalus membranaceus and its monomers treat peritoneal fibrosis and related muscle atrophy through the AR/TGF-β1 pathway. Frontiers in pharmacology 2024, 15, 1418485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Pang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; Lu, D.; Zhang, L.; Li, D. Astragalus Polysaccharides Attenuate Ovalbumin-Induced Allergic Rhinitis in Rats by Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and NOD2-Mediated NF-κB Activation. Journal of medicinal food 2021, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Species | Primer Sequence | Product Length | Tm/℃ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Cow | F:GGAGCGAGACCCCACTAACAT | 247 | 61 |

| R:TAAGGGGGCTAAGCAGTTGGT | ||||

| Mouse | F:GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG | 154 | 60 | |

| R:CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT | ||||

| CDH1 | Cow | F:CAACAAGGAAACAGGCGTCA | 175 | 59 |

| R:TGGGTTGAATCTGGGAGCAT | ||||

| Mouse | F:GGCACTCTTCTCCTGGTCCTG | 110 | 61 | |

| R: AAGATGGTGATGATATGAGGCTGTG | ||||

| CDH2 | Cow | F:CAGTGTGATTCCAACGGGGA | 146 | 60 |

| R:TCCCGGCGTTTCATCCATAC | ||||

| Mouse | F:ACAGCCCCTTCTCAATGTGA | 231 | 59 | |

| R:TCAGGTAGGGCTGGTTTGAG | ||||

| ACTA2 | Cow | F:ACCATCGGGAATGAGCGTTT | 97 | 60 |

| R:TGTTGTACGTGGTCTCGTGG | ||||

| Mouse | F:GCATGCAGAAGGAGATCACG | 157 | 59 | |

| R:TCGTCGTACTCCTGTTTGCT | ||||

| NLRP3 | Cow | F:CAACGGGGAAGAGAAGGCAT | 297 | 60 |

| R:TTGAGGTTCACGCTCTCACC | ||||

| Mouse | F:GGCCAAAGAGGAATCGGACA | 483 | 60 | |

| R:CTACGGCCGTCTACGTCTTC | ||||

| PYCARD | Cow | F:TGAGCAAGGGCCCTAGAAAC | 137 | 60 |

| R:ATCCAGAACCCCATCCACGA | ||||

| Mouse | F:GTGAGCTCCAAGCCATACGA | 124 | 60 | |

| R:TGACAGTGCAACTGCGAGAA | ||||

| Caspase-1 | Cow | F:ACAGCTATGGATAGAGCCCGA | 135 | 60 |

| R:ACTTTCTGAAGTGAGCCCCAG | ||||

| Mouse | F:TCCTTGTTTCTCTCCACGGC | 124 | 60 | |

| R:CGAGGGTTGGAGCTCAAGTT | ||||

| IL-1β | Cow | F:TCCGACGAGTTTCTGTGTGA | 206 | 59 |

| R:ATACCCAAGGCCACAGGAAT | ||||

| Mouse | F:GGAGCCTGTAGTGCAGTTGT | 208 | 60 | |

| R:AGCTTCAGGCAGGCAGTATC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).