1. Introduction

Plants and their natural compounds have been utilized in traditional medicine for centuries and remain a primary source for novel drug development, with many undergoing clinical trials to establish their therapeutic potential. The key constituents responsible for their pharmacological effects are secondary metabolites, including polyphenols (flavonoids, anthocyanidins, quinones, tannins, coumarins, phenolic acids), terpenes, alkaloids, lectins, polycarbohydrates, and polypeptides [

1]. Among these, polyphenols are of particular interest due to their broad range of pharmacological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, and anticancer effects [

2,

3]. Moreover, flavonoids—the most bioactive phenolic compounds—modulate key cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in inflammation, carcinogenesis, and microbial survival, making them promising candidates for phytotherapy and nanomedicine applications.

Two such examples are Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) and Sweet Wormwood (Artemisia annua), widely distributed and fast-growing plants from the Asteraceae family, found in Romania’s wild flora. They have been extensively studied for their medicinal properties, particularly due to their high content of bioactive compounds with antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities. Dandelion contains bioactive compounds such as sesquiterpenes, phenolics, terpenoids, sterols, and flavonoids, which contribute to its pharmacological properties [

4]. Sesquiterpenoids such as taraxinic acid contribute to both its anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties. Flavonoids, including apigenin, luteolin, and quercetin, along with flavanol glycosides (e.g., luteolin-7-β-D-glucopyranose, quercetin-7-β-D-glucopyranoside), are responsible for anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects [

5,

6]. Meanwhile, sterols such as taraxasterol, β-sitosterol, β-sitosterol-3-O-β-D-glucoside, gigantursenol A, along with novel triterpenoids (lupane, euphane, and bauerane), have been successfully isolated from Dandelion roots, demonstrating antitumor, antioxidant, and antibacterial effects [

7]. Additionally, phenolic compounds from Dandelion leaves and flowers, including hydroxycinnamic acid esters (chlorogenic acid, chicoric acid, and mono-caffeoyl tartaric acid), have been recognized for their antidiabetic properties[

8,

9]. One of the most significant bioactive components of Dandelion is Dandelion polysaccharide (DP), which has been reported to exhibit strong antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties [

4]. Recent studies suggest that DP’s physicochemical properties and structural configuration influence its anticancer activity, particularly against hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells [

10,

11].

Similarly, Sweet Wormwood (

Artemisia annua) exhibits numerous therapeutic effects, including antihyperlipidemic, antiplasmodial (malaria treatment), anticonvulsant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticholesterolemic, antiviral, antioxidant, antitumor, and anti-obesity activities [

12,

13]. Extracts from Sweet Wormwood demonstrated promising antitumor effects by inhibiting human gastric adenocarcinoma (AGS) cell-line proliferation, reducing tumor growth, and inducing apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells [

14,

15]. Recent studies have leveraged the bioactive compounds in Dandelion and Sweet Wormwood for the green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles, offering enhanced antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, and antitumor properties. These nanoparticles have been reported to exhibit enhanced antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, and antitumor properties, making them promising candidates for nanomedicine applications [

16,

17,

18].

Recent advances in nanotechnology have further demonstrated the potential of plant-mediated synthesis of metallic nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Montazersaheb et al. (2024) synthesized silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) using pumpkin peel extract and demonstrated their potential as radiosensitizers against triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells. These Ag-NPs enhanced the efficacy of radiotherapy by inducing apoptosis through pathways involving Bax, p53, and the PERK/CHOP axis [

19]. Similarly, İpek et al. (2024) utilized

Allium cepa L. (onion) peel aqueous extract for the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles (Au-NPs). The resulting Au-NPs exhibited significant antipathogenic, antioxidant, and anticholinesterase activities, highlighting the therapeutic potential of plant-mediated nanoparticle synthesis [

20,

21]. Building on these findings, green-synthesized nanoparticles have shown potent antitumoral properties by inducing apoptosis and inhibiting tumor proliferation [

22]. Their effectiveness extends beyond anticancer applications, as comparative studies with conventional chemotherapeutic agents have revealed their potential to enhance drug efficacy while minimizing adverse side effects [

23]. Moreover, their broad-spectrum antibacterial activity has been extensively studied, demonstrating significant inhibition of multi-drug-resistant bacteria [

24,

25]. These findings underscore the therapeutic versatility of green-synthesized nanoparticles, reinforcing their potential as an eco-friendly and efficient alternative to conventional treatments in oncology and antimicrobial therapies. These studies underscore the efficacy of green-synthesized nanoparticles in cancer treatment and antimicrobial applications, providing a foundation for our research on Dandelion (

Taraxacum officinale) and Sweet Wormwood (

Artemisia annua) extracts in nanoparticle synthesis.

The use of green-synthesized nanoparticles (NPs) in biomedical applications is gaining increasing interest due to their biocompatibility, tunable physicochemical properties, and improved therapeutic efficacy. Additionally, their antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties further support their use in therapeutic applications [

26]. Compared to chemically synthesized nanoparticles, green-synthesized NPs offer significant advantages, including reduced toxicity, environmentally friendly production, and improved biological interactions [

27]. Several studies have demonstrated the powerful reducing capacity of plant polyphenols in forming metallic nanoparticles [

17,

28,

29]. However, most studies have not quantitatively assessed the presence of phytotherapeutic compounds in the final colloidal solution [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. This lack of data hinders their ability to correlate bioactive compound concentrations with nanoparticle stability and therapeutic effects, limiting reproducibility and standardization. To address this gap, our study systematically quantifies the residual phytotherapeutic compounds after nanoparticle synthesis using dosage methods, FTIR, fluorescence analysis, and UV-Vis spectroscopy. This approach ensures a more accurate understanding of how bioactive compounds influence nanoparticle properties and biological activity, contributing to the optimization of green synthesis for biomedical applications.

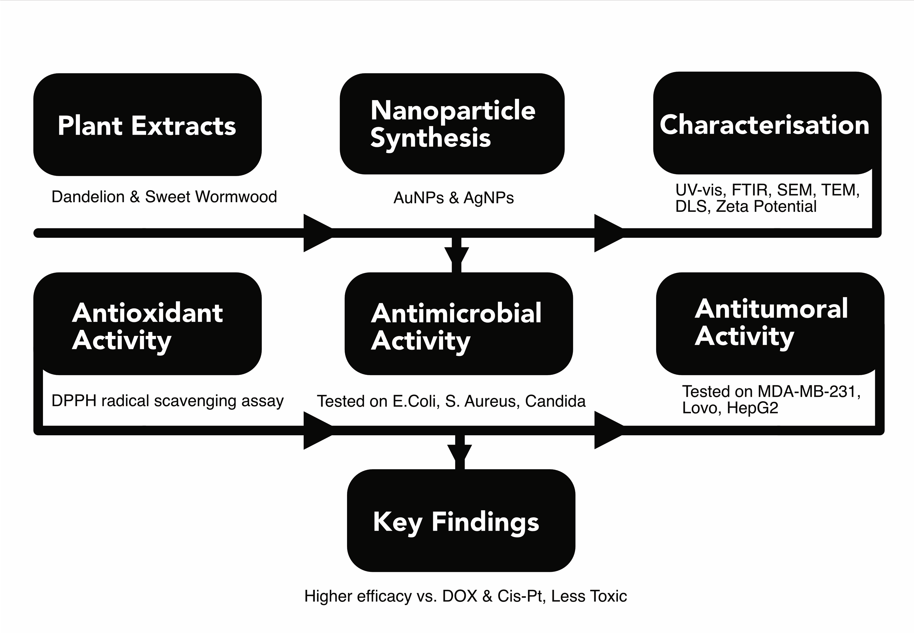

The aim of this study is to investigate the therapeutic potential of bioactive compounds derived from Sweet Wormwood (Artemisia annua) and Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), sourced from Romania’s wild flora, and to evaluate their impact on the stability, size, and biological activity of green-synthesized nanoparticles. This research explores the eco-friendly synthesis of silver (Ag) and gold (Au) nanoparticles using aqueous and alcoholic extracts (50:50 and 50:30 water-to-ethanol ratios) from these plants. The physicochemical and biological properties of the synthesized nanoparticles were systematically characterized using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), fluorescence analysis, UV-Vis spectroscopy, Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), and polydispersity index (PI) measurements. Additionally, biological assessments, including the DPPH assay, agar diffusion method, and MTS cytotoxicity assay, were performed. The antitumoral activity of the nanoparticles was evaluated against MDA-MB-231, LoVo, and HepG2 cancer cell lines. To assess their potential for safer therapeutic applications, the selectivity index (SI) was determined as a measure of lower toxicity compared to the reference chemotherapeutic drugs, DOX and CisPt.

2. Experimental

2.1. Plant Material and Preparation of the Plant Extract

The aerial parts of Dandelion (

T. herba) and Sweet Wormwood (

A. herba) were collected from Ilfov County, Romania, in June - July 2022, and their voucher specimens were deposited in the Herbarium of the Bucharest Botanical Garden, University of Bucharest, Faculty of Biology, under the reference numbers 410416 and 408939 respectively.. The aerial parts of the two plants were washed, dried in shade at room temperature for seven days and then ground with a mechanical grinder as seen in

Figures S1 and S2 from the Supplementary Material (SM). An ethanolic extract was prepared using 1 g of each dried powder of vegetal product (sieved through sieve VI) and 100 mL of ethanol (30⁰ or 50⁰), heated on a water bath at reflux for 30 minutes and then filtered through Whatman filter paper (Whatman

® qualitative filter paper, Grade 1, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The obtained extracts were then stored at 4⁰ C until analysis.

2.2. Green Synthesis and Characterization Methods

For the synthesis of AgNPs using Dandelion extracts, 5 mL of EETOH-D (in 50% or 30% ethanol) where added to 50 mL of 1 mM AgNO3 (Sigma Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany). The mixtures have been shaken at 60⁰ C for 30 min. A color change to dark brown indicated the formation of silver nanoparticles from ethanolic dandelion extract, which were left covered until characterization at 4-8⁰ C. Similarly, silver nanoparticles were obtained using only the aqueous dandelion extract.

For the synthesis of silver nanoparticles from the ethanolic Sweet Wormwood extract (50% or 30% EETOH-SW extracts), 10 mL of ethanolic Dandelion extract (prepared in 50% or 30% EETOH-SW extracts) was added to 100 mL of 0.5 mM HAuCl₄·3H₂O (Sigma Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany). The mixture was then shaken at 60°C for 30 minutes. A color change to violet indicated the formation of silver nanoparticles, which were then kept covered at 4–8°C until characterization. Similarly, gold nanoparticles were obtained using only the aqueous sweet wormwood extract, referred to as AuNPsEaq-SW.

2.2.1. UV-VIS Absorption and Fluorescence

UV-VIS properties of the green synthesis were recorded using both plant and their corresponding extract using a U-0080D UV–Vis spectrometer (Hitachi, Japan), while fluorescence emission spectra were recorded with a spectrometer equipped with a 450 W Xenon lamp as an excitation source (model FLS920, Edinburgh Instruments Ltd., UK).

2.2.2. FTIR-ATR

Fourier transform infrared spectrometry (FTIR) was used to study the configurations of chemical bonds in the Ag/ and Au NPs samples from wormwood and Dandelion extracts and the ionic salts from which they were formed (0.5mM HAuCl4x3H20 and 1mM AgNO3). A Bruker Optics Tensor 27 spectrometer equipped with an ATR Platinum accessory with a single reflection diamond crystal was also employed. All samples were traced after 64 scans, with a resolution of 4 cm-1, on a spectral domain of 4000 - 400 cm-1. Each sample was prepared using a drying process at room temperature.

2.2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Nanoparticles were investigated morphologically using Nova NanoSEM 630, a Field Emission Scanning Microscope (FE-SEM) (FEI Company, Massachusetts, USA), with an operating voltage of 5 kV and a magnitude of 40 and 300 kx.

2.2.4. High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Sample Preparation for Transmission Electron Microscopy was performed using the following sequence. Firstly, Formvar and Carbon coated 100 mesh copper TEM grids were plasma treated to obtain a hydrophilic grid surface, by means of a PELCO easiGlow™, Glow Discharge System. Then, 1 mL of each sample was pipetted in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and sonicated for 1 to 2 minutes at room temperature, at 59 kHz, in an ultrasonic bath, FALC LBS 2 – 4.5 L. Afterword, 4 µL of each of the sonicated contents were pipetted on the treated TEM grids, slightly blotted with filter paper, and left to dry for 10 minutes. Micrographs were recorded on these grids using the 4k × 4k Ceta camera of a Talos F200c transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA USA), at 200kV, at 92 000x, 240 000x, 390 000x and 650 000x nominal magnifications.

2.2.5. Hydrodynamic and Electrophoretic Light Scattering Measurements

The hydrodynamic diameter and surface charge of the colloidal dispersions were characterized using a Delsa Nano C instrument from Beckman Coulter, USA, by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and electrophoretic light scattering (ELS). Particles were illuminated by a dual 30 mW laser diode, producing time-dependent fluctuations in the intensity of the laser light. The scattered light was collected at 165⁰ for size measurements and 15⁰ for zeta potential measurements (diluted concentration samples), and then measured by a highly sensitive detector. Both measurement types (DLS and ELS) were performed a room temperature, with each sample measurement being performed in triplicate, and with the DelsaTMNano 3.73 software being used for analysis.

2.2.6. Total Polyphenol content and Total Flavonoids content

Total polyphenolic (TPC) content was determined using the Singleton colorimetric method, based on the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (Sigma Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) and gallic acid certified reference material (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) as the standard polyphenol [

36]. For this determination, 1 mL of plant extract was mixed with 5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (previously diluted 10 times with distilled water) and 4 mL of 7.5% sodium carbonate solution (Merck Group, Darmstadt, Germany), with the mixture then stirred and left to stand for 60 minutes in the dark at room temperature. The absorbance of the blue mixture solution was read on a VWR UV-6300 PC Spectophotometer (VWR International, Wien, Austria) at a wavelength (λ) of 765 nm. For the quantification of the phenolic content, a calibration curve Equation (1) was established with gallic acid solutions in methanol (Sigma Aldrich, Germany) ranging from 10 to 50 µg/mL:

The results were expressed as mg gallic acid equivalent/g dry matter. Each assay was performed in triplicate. The total flavonoid content (TFC) of the two extracts was determined by the aluminum chloride colorimetric method described in the tenth Edition of the Romanian Pharmacopoeia [FRX] [

37] plant extracts (10 mL) were diluted with methanol in a 25 mL volumetric flask and then filtered. Subsequently, 5 mL of these diluted extracts were mixed with 5 mL sodium acetate (100 g/L) (Sigma Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany), 3 mL aluminum chloride (25 g/L) (Merck Group, Darmstadt, Germany), and methanol to volume 25 mL. The mixtures were kept in the dark for 15 min at room temperature and their absorbances were measured on a VWR UV-6300 PC Spectophotometer (VWR International, Wien, Austria), at a wavelength (λ) of 430 nm, in comparison with a blank prepared in the same way but without the reagents. The concentration of flavonoids was expressed as mg rutin (RE) equivalent/g dry plant material for extracts and in µg/mL for colloidal solution with nanoparticles. All the regents were of analytical grade, and the solvents were of HPLC quality.

2.3. Description of Samples and Their Abbreviations

All abbreviations used in this study to define the treatments applied to the three tumor cell lines (MDA-MB-231 - human breast adenocarcinoma, HepG2 - human liver cancer, LoVo - human colon adenocarcinoma) and to the normal human endothelial cell line (HUVEC) are listed and explained below in

Table 1.

2.4. Biological Tests

2.4.1. Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant activity of the two indigenous plants was analyzed using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazylradical scavenging assay. The method is based on the change in colour of the DPPH solution from violet to yellow when it is reduced by a proton donor (an antioxidant). For this analysis, 100 mg of DPPH (Sigma Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) was diluted with methanol in a 200 mL volumetric flask. 1 mL of the sample was mixed with 5 mL of the diluted DPPH and methanol up to 25 mL. After incubating for 30 minutes in the dark at room temperature, the absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 517 nm. The scavenging ability of the two extracts was calculated using the DPPH scavenging activity % Formula (2):

where Abs

control is the absorbance of diluted DPPH; Abs

sample is the absorbance of the sample extracts with DPPH [

38,

39]. Each assay was performed in triplicate.

2.4.2. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity

The microorganisms used for testing have been sourced from the international ATCC collection and/or the Pharmaceutical Microbiology Laboratory sub-collection of wild (environmental) strains or from clinical samples. The equipment was accessed through the endowment of the Pharmaceutical Microbiology Laboratory, including installations, inventory items, glassware, instruments, laboratory consumables, specific reagents, protective equipment, various sanitary materials. Working Methods: The agar diffusion method was used to evaluate the antimicrobial pharmacological effect of obtained extracts. The sterility and their own microbial load of the extracts was also analyzed determining their microbial load (bacterial and fungi counting) and conducting specific physico-chemical and antimicrobial pharmacological effect tests. These tests were adapted to comply with current regulations [

32].

The antimicrobial effect was evaluated by measuring in millimeters the diameter of the

Microbial Inhibition Zone (IZ) around the substance, expressed by the arithmetic mean of the measurement in two dimensions (maximum and minimum diameters) with the precision of tenths of a millimeter. The rules of Good Microbiology Laboratory Practice were applied, the description of the techniques used to be briefly presented for each individual experiment [

40,

41].

For antibacterial activity, selected opportunistic pathogens bacterial strains, namely Staphylococcus aureus a Gram-positive coccus; Escherichia coli a Gram-negative bacillus, Enterobacteriaceaee family; Pseudomonas aeruginosa a Gram-negative bacillus , non-Enterobacteriaceae family and Bacillus subtilis a Gram-positive Bacillaceae family were cultured in Petri dishes Φ 10 with Mueller-Hinton Agar. The culture medium was swabbed with bacterial suspension, using sterile swabs and afterwards 6 inert cellulose biodiscs with 10 µL of test substance each and 6 microcylinders with 100 µL each sample was applied. The application was made using a standard template to ensure uniformity. Aerobic incubation was performed at 37⁰ C on the 1st ,2nd and 3rd days, and measuring the diameter of the growth inhibition zone around the extracts for calculating the MCI was done in µg/µL.

For the antifungal activity, several species of emerging fungal pathogens, including yeasts, like Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida albicans and filamentous fungi such as Penicillium sp. and Aspergillus sp. were tested, using a Sabouraud Agar Medium. The culture media were swabbed with the fungal suspensions, using sterile swabs and afterwards 6 inert cellulose biodiscs with 10 µL of test substance each and 6 microcylinders with 100 µL each sample were applied. The application was made using a standard template to ensure uniformity. The Petri dishes were incubated at 26⁰ C, aerobically for 24 hours to 1 week, depending on the fungal strain and after the incubation period the results were read and interpreted, by measuring the diameter of the growth inhibition zone around the extracts.

The MIC was calculated in μg/μl (equivalent to mg/ml or g/l) for each substance on each microbial strain by evaluating the volume (V) into which the substance diffused, using Formula (3) where R is the radius of the IZ (half the diameter) and h is the thickness of the culture medium.

2.4.3. Antitumoral Tests

For each of the three plant extracts studied (Dandelion - D, Sweet Wormwood - SW), both aqueous and alcoholic extracts were subjected to successive serial dilutions in deionized water at the following ratios: 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8, 1:16, 1:32, 1:64, and 1:128. The diluted samples were then used for the MTS cytotoxicity assay.

Similarly, samples containing silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were prepared by serial dilutions following the same 1:1 to 1:128 dilution scheme in deionized water. To establish a reference for antitumor activity, two control groups were used, consisting of the standard chemotherapeutic drugs DOX and Cis-Pt. These control samples were prepared under the same dilution conditions as the test samples.

All cytotoxicity results obtained for each plant extract, plant extract-nanoparticle complex (obtained from aqueous or ethanolic extracts of D or SW) were compared to the anticancer activity of these two clinically used synthetic drugs.

The potential cytotoxic activity of the studied extracts was evaluated on two adherent human cancer cell lines standardized against normal human endothelial cells and compared with the cytotoxicity of oncolytic drugs commonly used for cancer treatment. The human breast adenocarcinoma cell line MDA-MB-231 was purchased from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC, Catalogue No. 92020424), while the human colorectal adenocarcinoma cancer cell line LoVo (Catalogue No. CCL-229TM), human umbilical vein endothelial cells HUVEC (Catalogue No. CRL-1730 TM) and the human liver cancer cell line HepG2 (Catalogue no. HB-8065TM) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Control drug, Cis-diammineplatinum(II) dichloride (CisPt) and DOX were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All working solutions for the control drugs were prepared from stock solutions of 1 mM DOX and Cis-Pt, respectively, by serial dilutions in culture media before each experiment. Adherent cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo, USA) and incubated at 37⁰ C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. After 24 h, when the cells reached approximately 60% confluence, they were treated with different concentrations of the extracts for different periods of time. The cells in the flasks were then detached with a nonenzymatic solution of PBS/1 mM EDTA, washed twice in PBS, and used for proliferation/cytotoxicity assays. Untreated cells were designated as control cells.

To evaluate the cytotoxicity induced by the extracts, cell proliferation assays with an CellTiter 96 aqueous solution (Promega Corporation 2800 Woods Hollow Road Madison, WI 53711 USA) were used, which is an MTS (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxy-phenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt) colorimetric assay. All assays were performed in triplicate in flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates (Falcon, Teterboro, NJ, USA). The method is based on the capacity of metabolically active cells to reduce the yellow tetrazolium salt MTS to the colored formazan, a compound that is soluble in the culture medium. 1 x 104 cancer or normal cells/well were cultured in 100 µl for 24h and treated for an additional 24h or 48h with increasing concentrations of extracts or oncolytic drugs.

After incubation, 20 µL of coloring mixture reagent MTS was added in each well, and then the plates were incubated at 37

0C for 4h, with mild agitation every 20 min. The color developed during incubation, and it was spectrophotometrically quantified at λ = 492 nm by using a Dynex ELISA reader (DYNEX Technologies–MRS, Chantilly, VA, USA). The percentage of viability compared to untreated cells (considered 100% viable) was calculated with the Formula (4):

where, T = absorbance of treated cells, U = absorbance of untreated cells and B = absorbance of culture medium (blank), for λ = 492 nm.

Cell lysis data was expressed as the mean values ± standard deviations (SD) of three different experiments.

2.4.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Python 3.12 to evaluate the statistical differences of the prepared compounds (EEOTH30%-SW, AgNPsEEOTH3%-SW, AgNPsEEOTH3%-D, AuNPsEaq-D and AuNPsEEOTH3%-D) in comparison with the control ones (Cis-Pt, DOX) on a per cell type (HUVEC, LoVo, MDA-MB, HepG2) basis. The assumption of continuity of variables and absence of outliers conditions for statistical analysis have been observed, however due to the dependence of samples (dilutions, measurements at 24 h and 48 h) a repeated measure statistical method needs to be employed. Moreover, with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for data normality being invalidated (p < 0.05), a non-parametric statistical test has been decided upon (Friedman test) followed by a post hoc test (Siegel-Castellan) to assess the source of the statistical difference. Analysis has been implemented using the scipy.stats and scikit_posthoc libraries. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05, with results being considered significant when p < α.

2.4.5. Determination of Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration and Selectivity Index

The Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50) value was determined using Python 3.12 by fitting a four-parameter logistic regression (4PL) curve to the data through the scipy curve_fit function. IC50 represents the concentration at which 50% of the cells are inhibited compared to untreated controls. These curves depict variations in cell survival, reflecting either increased cytotoxicity or reduced proliferation. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), which indicates the concentration required to achieve a 50% reduction in viable cells, is a key parameter for evaluating the pharmacological and biological effects of a treatment. IC50 values are typically reported as mean ± standard error, with error estimation derived from a four-parameter logistic (4PL) regression model. In this study, the regression was performed using Python, specifically utilizing the scipy.optimize.curve_fit function. The Selectivity Index (SI) was calculated to determine how selective each compound was for cancer cells relative to normal cells[

42]. The formula used was:

If SI > 2–3, it indicates high selectivity for cancer cells (desirable). If SI ≈ 1, it means no selectivity, affecting both normal and cancer cells. If SI < 1, the compounds are more toxic to normal cells than to cancer cells (undesirable). Each compound’s SI was calculated for both LoVo and MDA-MB cells using HUVEC IC50 values as a reference.

3. Results

3.1. UV-VIS Spectra Characterization

The UV-VIS spectrophotometric analysis monitored the formation of silver and gold nanoparticles reduced by Dandelion and Sweet Wormwood extracts. Absorption spectra of extracts (denoted as, I-for Sweet Wormwood and II- for Dandelion), silver nitrate (I - blue curve), chloroauric acid (II - red curve), were recorded from 200-700 nm and are presented in

Figure 1a.

Figure 1b–e shows the UV-VIS spectra obtained for the nanoparticle solutions formed through bioreduction with aqueous or alcoholic extracts from the two plants. In

Figure 1b, the UV-VIS spectrum obtained for AgNP

SEaqD (curve I) is compared with the UV-VIS spectrum after bioreduction using the alcoholic Dandelion extract, AgNP

SE

ETOHD (curve II), with a 1:10 ratio of aqueous Dandelion extract to 1 mM AgNO3.

Figure 1c includes the UV-VIS spectra for gold nanoparticles obtained from the aqueous Dandelion extract, AuNPSEaqD (I), compared with gold nanoparticles obtained after bioreduction using the alcoholic Dandelion extract, AuNP

SE

ETOHD (II). Similarly,

Figure 1d presents the UV-VIS spectra for silver nanoparticles reduced with Wormwood aqueous extract, AgNP

SEaqSW (I), and alcoholic extract, AgNP

SE

ETOHSW (II). For Wormwood gold nanoparticles, the spectra are shown in

Figure 1e, with aqueous extract indicated as AuNP

SEaqSW (I) and the alcoholic extract as AuNP

SE

ETOHSW (II).

3.2. Total Polyphenol Content and Total Flavonoids Content

The results indicated that

Artemisia herba was richer in total polyphenols (GAE/g DW) compared to

Taraxacum herba (16.82 ± 0.12 mg vs. 15.78 ± 0.35 mg). Similarly, the flavonoid profile (RE/g DW) showed higher levels in

Artemisia herba than in

Taraxacum herba (9.17 ± 0.73 mg vs. 7.95 ± 0.65 mg). These findings aligned with other studies, such as Epure et al., who had found lower polyphenol and flavonoid contents in Dandelion tinctures (13.15 mg GAE/g DW and 6.87 mg RE/g DW) compared to our study [

43]. Contrarily, Ivanov reported higher phenol and flavonoid content in ethanolic Dandelion leaf extract (35.03 mg GAE/g DW) [

44]. Our results were also consistent with Guo et al.’s findings on Sweet Wormwood, where they reported a TPC of 39.58 mg GAE/g and a TFC of 7.04 mg RE/g [

45]. Furthermore, Saunoriute et al. reported varied phenolic contents in

A. stelleriana and Sweet Wormwood samples (176.7 - 288.59 mg RE/g DW and 297.37 - 9.18 mg RE/g DW, respectively) [

46]. Carvalho et al. found a range of 0.22 ± 0.002 mg to 0.39 ± 0.000 mg GAE/g DW in methanol extracts of various

Artemisia species [

47].

Both extracts were rich in polyphenols and flavones, which are expected to play a significant role in nanoparticle synthesis. To confirm their presence in colloidal nanoparticle solutions, a quantitative analysis was performed, and results for total phenolic compounds represented by GAE and flavone content by RE are provided in

Table 1.

3.3. Fluorescence of Nanoparticles

The produced green nanoparticles act as carriers for polyphenolic compounds. According to the literature, the emission range of 300 to 380 nm corresponds to polyphenols, while the emission range of 600 to 700 nm is attributed to chlorophyll and its derivatives [

48]. Fluorescence spectra were recorded for all samples with nanoparticles and are presented in the supplementary material as

Figure S3 (a-f).

3.4. FTIR

In our study, ATR-FTIR measurements were performed to identify the type of bonds in the biomolecules used as a reducing agent for the synthesis of metal nanoparticles, but also for the effective coating and stabilization of gold and silver nanoparticles.

Table S1 shows the possible assignments of the absorption bands of the 6 samples involved in the study.

Figure 2a displays the FTIR spectra of all samples superimposed on that of Dandelion such that the Dandelion alcoholic extract is represented by (I), AuNPsE

ETOHD by (II), and AgNPsE

ETOHD by (III). Meanwhile,

Figure 2b displays the FTIR spectra of all samples superimposed on that of Sweet Wormwood with the alcoholic extract being represented by (I), AuNPsE

ETOHSW by (II), and AgNPsE

ETOHSW by (III).

3.5. DLS Analysis, PDI, Zeta potential, SEM and TEM

The polydispersity index (PDI) represents the ratio of particles of different sizes to the total number of particles. A low PDI value (<0.1) indicates a more monodispersed sample. Table 2 displays the PDI values, average hydrodynamic diameter, and zeta potential for all obtained nanoparticles.

Figure 3 (a-h) present TEM images for all analyzed samples and Table 3 contains the corresponding size and morphology of nanoparticles measured by TEM.

3.6. Biological Tests

3.6.1. Antioxidant Proprieties

Table 4 shows the percentage of DPPH inhibition obtained by the green nanoparticles and by their corresponding extracts.

3.6.2. Antimicrobial and Antifungal Proprieties

Representative species were selected from major groups of pathogenic bacteria prevalent in human and veterinary infections, including Staphylococcus aureus a gram-positive coccus, Escherichia coli for gram-negative bacillius, Enterobacteriaceae family, Pseudomonas aeruginosa for gram-negative bacillus, non-enterobacteria family, and Bacillus subtilis (B.s) gram positive Bacillaceae family member, were cultured in Petri dishes Φ 10 with Mueller-Hinton Agar. The culture media were swabbed with bacterial suspension, using sterile swabs and afterwards 6 inert cellulose biodiscs with 10 µL of test substance each and 6 microcylinders with 100 µL each sample were applied. The application was made using a standard template to ensure uniformity. Aerobic incubation was at 37⁰ C 1, 2 and 3 days, and measuring the diameter of the growth inhibition zone around the extracts for calculating the MCI in µg/µL.

The antifungal effect was assessed on

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida albicans, Penicillium sp, and

Aspergillus sp, with incubation on solid Sabouraud media for 3 days to 1 week at 23-26⁰ C, measuring the zone of inhibition as with bacteria. The culture media were swabbed with the fungal suspensions, using sterile swabs and afterwards 6 inert cellulose biodiscs with 10 µL of test substance each and 6 microcylinders with 100 µL each sample were applied. The application was made using a standard template to ensure uniformity.

Figure 4a,b illustrate the zone of inhibition versus inhibition concentration calculated for Dandelion and respectively Sweet Wormwood samples using equation (2). The antifungal effect of the nanoparticles is presented in

Supplementary Figure S6 for the Dandelion samples and

Figure S7 for the Sweet Wormwood samples.

3.6.3. Antitumoral Effect

Studies were carried out in vitro to investigate the effect of the tested samples on the LoVo (human colon adenocarcinoma) and MDA-MB-231 (human breast adenocarcinoma) human tumor cells and liver tumor line HepG2 when compared to the HUVEC (umbilical vein endothelial cells human) normal cell line (

Figure 5 a,b and c). The positive controls of the study were CisPt and DOX, which are commonly used to treat colon and breast cancer, respectively. To evaluate cell viability, dilutions of the initial colloidal solutions were made and the cell lines were exposed for 24 and 48 hours.

Table 5 summarizes the statistical analysis results, highlighting the significant differences between green-synthesized nanoparticles and conventional chemotherapeutics (Cis-Pt and DOX) across various cancer and normal cell lines.

Tables S7 and S8 present the SI and IC50 values after sample treatment on LoVo and MDA-MB-231 cell lines, along with their corresponding errors, at 24 and 48 hours of treatment.

Table S9 displays the SI and IC50 values after sample treatment on HepG2 cells.

Figure 6 illustrates the evolution of the SI for all tumor cell lines over time.

4. Discussions

4.1. UV-VIS and Fluorescence

Comparing silver nitrate and Dandelion solutions with their mixture after titration (50 mL 1 mM AgNO

3, 5 mL of each aqueous and ethanolic extract under magnetic stirring at 200 rpm), the solution turned dark brown after 30 minutes, indicating colloidal silver nanoparticle formation as seen on the inset of

Figure 1(b). The UV-VIS spectra showed an absorbance peak at 462 nm for Ag nanoparticles in the ethanolic extract (

Figure 1b-I) and 450 nm for Ag nanoparticles in the aqueous extract (

Figure 1b-II). The estimated sizes were 37.57 nm for the aqueous extract nanoparticles and 73.97 nm for the ethanolic extract nanoparticles. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy confirmed by other studies an average particle size of 15 nm with a maximum wavelength of 435 nm for silver nanoparticles resulting from the bioreduction with Dandelion [

49]. The reducing power of the extracts depends on their biochemical composition and on the solvent employed in the extraction. Ethanol, being less polar, concentrates biomolecules more, but the aqueous colloidal solution showed a higher number of polyphenols involved in metal reduction. Absorbance values between 400-480 nm for Ag were consistent with previous studies for nanoparticle synthesis using Dandelion flowers [

50]. Dandelion silver nanoparticles obtained from ethanolic extracts contained the same gallic content as those from aqueous extracts, while a quantity of rutin was present only for the AgNPs E

ETOHD as shown in

Table 1.

For the reduction of gold with Dandelion, 8 mL of aqueous/ethanolic Dandelion extract was necessary, and the UV-VIS spectra exhibited the same absorbance maximum peaks for both colloidal solutions at 568 nm as shown in

Figure 1c. The inset of

Figure 1c presents the color change of the extract to violet confirming the formation of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). Previous studies have shown the dependence between the position of the SPR maximum and the FWHM of metal nanoparticles in colloidal systems and their size [

51]. Using only the Haiss equation for predicting the size of AuNPs, a theoretical size of 109.15 nm for AuNPs E

ETOHD and 109.81 nm for AuNPsEaqD can be estimated, which corresponds to the same maximum absorption at 568 nm wavelength but with a small variation of initial wavelength at the inflexion point of the UV-VIS spectra (λ

0).

UV-VIS spectra fitting techniques for estimation of NPs dimensions were less accurate for gold nanoparticles due to procedural limitations with high error. Size estimations by fitting from UV-VIS spectra closely matched with SEM values, especially for the silver nanoparticles.

The characteristic band of the silver nanoparticles between 400-450nm should be present only in the solution containing silver nanoparticles. Consequently, the UV-VIS spectra for both colloidal solutions exhibited a band at 441 nm for AgNPsEaq-SW (

Figure 1d-I) and 445 nm for AgNPsE

ETOH -SW (

Figure 1d-II). The corresponding sizes of the AgNPs, determined using the same theoretical methods as applied to those from Dandelion extracts through UV-VIS spectral analysis, were 38.48 nm for AgNP

SEaq-SW and 41.21 nm for AgNPsE

ETOH -SW [

26].

The bioreduction of gold from Sweet Wormwood led to the formation of a maximum absorbance at 563 nm for AuNPs Eaq-SW corresponding to a nanoparticle size of about 105.67 nm (Haiss equation), as shown in the spectra from

Figure 1e - I.

Figure 1e – II show the UV-VIS spectra of AuNPs E

ETOHSW, which has a maximum absorbance at 557 nm, and a corresponding calculated size of 111.12 nm. The inset of

Figure 1e presents a color change from brown to red-violet, confirming the formation of gold nanoparticles. The time required for the reduction of metallic nanoparticles with Sweet Wormwood was 40 minutes, although an increase in this maximum was observed after 24 hours, indicating that nanoparticles formation continues over time. Although the extract-to-salt ratio required for bioreduction and nanoparticle formation was the same for all syntheses, a longer time was needed for the gold nanoparticles from wormwood to form, taking 40 minutes compared to the 30 minutes required for silver nanoparticles. It is possible that the reduction process for gold requires more time because Au ions are more difficult to reduce to the zero-valent state compared to Ag ions. While the maximum absorbance remained unchanged, a narrowing of the Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) was observed over time, suggesting that the nanoparticles become more homogeneous in solution. However, there was a tendency for flocculation, especially in gold nanoparticles, which might indicate that the bonds between the therapeutic compounds and the nanoparticles can break over time, leading to aggregation. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) studies, zeta potential and polydispersity index better clarify this aspect.

The obtained green nanoparticles act as carriers for polyphenolic compounds. According to literature, the emission region from 300 to 380 nm corresponded to polyphenols, and the emission region from 600 to 700 nm was ascribed to chlorophyll and its derivatives [

52]. For AgNPsE

ETOH -D, the maximum excitation and emission wavelengths were at 270 nm/360 nm and 310 nm/435 nm respectively as indicated in

Figures S3a and S3b. For AgNPsEaq -D, the intensity of the fluorescence band at 360 nm/480 nm was 1x10

5 (

Figure S3b and S3c), lower than Ag NPs obtained from the D ethanol extract (1.8x10

5) and shifted after excitation to 270 nm. This may indicate a lower content of polyphenols bound to the silver nanoparticles obtained from the aqueous extract, taking into consideration that the fluorescence source is the polyphenols [

22]. In the case of AuNPsE

ETOH -D, their maximum excitation and emission wavelengths were similar: 270 nm/380 nm and 400 nm/470 nm respectively (

Figure S3€ and Figure S3(f). The intensity of the fluorescence bands of Au NPs was higher compared to AgNPs, regardless of whether the extract was aqueous or ethanolic. This demonstrates a greater capacity of the green gold nanoparticles from Dandelion/Sweet Wormwood to act as carriers of polyphenols compared to the silver nanoparticles. The aqueous and ethanolic solutions with Ag/Au NPs obtained from SW exhibited similar behavior, which suggests that the obtained green nanoparticles act as carriers of polyphenols, potentially having significant biological and pharmaceutical importance. Characterizing the colloidal stability of these nanoparticles is crucial, especially since no chemical stabilizing agents were used. Stability tests were using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) analysis, polydispersity index, and zeta potential.

4.2. FTIR

In our study, Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) and FTIR measurements were performed to identify the type of bonds in the biomolecules used as a reducing agent for the synthesis of metal nanoparticles, but also for the effective coating and stabilization of gold and silver nanoparticles.

From a structural point of view, the chemical composition of Dandelion and Sweet Wormwood is influenced by genetic variability, the plant organ, and the biological stage. Dandelions are rich in vitamins, inulin, phytosterols, amino acids and minerals, sesquiterpenes, triterpenes, phytosterols and phenolic compounds in different proportions [

53]. Similarly cis-epoxyocimene, cis-chrysanthenol, thujone, bornyl or chrysanthenyl acetate, chrysanthenol, chamazulene, sabinyl, 1,8-cineole, caryophyllene, myrene, sabinene, linalool, chrysanthenyl acetate and trans-sabinyl acetate can be isolated from Sweet Wormwood [

54].

The FTIR spectrum for our Dandelion extract (

Figure 2a-I) showed a broad band due to the vibration mode of the O-H bonds of alcohols and phenols hydroxyl groups superimposed on the N-H of amine compounds (4000 – 3000 cm

-1). The peaks in the range of 3000-2800 cm

-1 can be associated with stretching vibrations of C-H, and those in the range of 1600-1000 cm

-1 can be attributed to both the stretching and deformation modes of the CO groups (C=O conjugated to the aromatic ring (1591 cm

-1), C-O from polyphenols (1591 cm

-1), C-OH from alcohols or esters (1024 cm

-1) [

10,

42]. Comparing the spectra of the metallic nanoparticles (

Figure 2(a)-II and III) with the spectrum of the Dandelion extract, a slight shift of the bands in the spectral domains of 4000-3000 cm

-1 and 1600-1000 cm

-1 is observed, suggesting the weakening of the intermolecular H-bonding and the involvement of CO groups in the anchoring of biomolecules surface of metal nanoparticles [

47].

Figure 2b shows the spectrum of our Sweet Wormwood extract (

Figure 2b-I) in which bands that can be associated with: (i) the vibrational mode of the O-H bonds from alcohols and phenols hydroxyl groups superimposed on N-H from amine compounds (3270 cm

-1), (ii) stretching and deformation mode of CH bonds from fatty acids or methoxy compounds (3000-2800 cm

-1), and respectively cyclohexane rings (897 cm

-1) or aliphatic groups (700-600 cm

-1); (iii) C=O conjugated to the aromatic ring from flavonoids (1700-1500 cm

-1); (iv) stretching and deformation mode of C-O bonds from alcohols or phenols compounds, cyclic or aliphatic substituted ethers (700-600 cm

-1) [

55,

56,

57,

58] can be seen. Comparing the spectra of the metallic nanoparticles (

Figure 2b-II and III) with the spectrum of the Wormwood extract, small shifts of the spectral bands are observed concomitant with the change in the shape of the bands below 600 cm

-1, thus confirming the reduction of the metal ions, Mn

+ to M

0 (M=Au, Ag), but also their coverage with biomolecules. The anchoring of biomolecules is supported by the existence of characteristic groups of the extract in the range of 4000-600 cm

-1. The displacement of the observed peak for the extract from 3268 cm

-1, to 3276 cm

-1 for Au nanoparticles and to 3243 cm

-1 for AgNPs, concomitant with the disappearance of the bands centered at 1390 cm

-1 and 1262 cm

-1, in the spectrum of the SW extract, and the appearance of a band at 1346 cm

-1 in the NPs spectra, confirm the involvement of hydroxyl and carbonyl groups in the reduction of salts and the stabilization of metal nanoparticles [

45,

59].

Consequently, the presence of polyphenolic acids and flavonoids was confirmed through FTIR analysis. These compounds tend to be more concentrated in the colloidal solutions derived from Wormwood extracts compared to those obtained from Dandelion extracts, as illustrated in

Table 1. Considering that all phytoactive compounds identified in the NPs colloidal solutions played a role in the bioreduction process, the size of the nanoparticles obtained from wormwood extracts should be smaller than those produced from Dandelion extracts, a finding that was corroborated by the SEM and TEM investigations.

4.3. Correlations Between Physico-Chemical Properties, Antioxidant Activity, Morphology, and Antimicrobial Effects

The interrelation between nanoparticle morphology, antioxidant properties, physico-chemical characteristics, and antimicrobial effects provides essential insights into their biomedical potential. Our study highlights significant variations based on plant sources, solvent type, and nanoparticle composition.

4.3.1. Influence of Polyphenolic Content on Nanoparticle Stability, Antioxidant Activity, and Antibacterial Action

The total polyphenol (TPC) and flavonoid (TFC) content of extracts and nanoparticles (

Table 1) directly impact their stability, antioxidant activity, and antimicrobial potential. Dandelion-derived nanoparticles (D-NPs) had lower flavonoid retention, which may explain their slightly lower antioxidant performance and weaker antibacterial effects as shown in

Figure 4a. Sweet Wormwood-derived nanoparticles (SW-NPs) exhibited the highest TPC and TFC values, particularly AuNPsE

ETOH-SW (152.15 µg RE/mL), which correlates with their enhanced colloidal stability (Zeta potential: -53.29 mV, Table 2) and strong antibacterial action against

Staphylococcus aureus (

Figure 4b).

The antioxidant assay (DPPH, Table 3) revealed that: AgNPsEaq -SW had the highest antioxidant activity (83.10%), correlating with their high TPC (97.90 µg GAE/mL) and a small, uniform size (11.7±4.6 nm, Table 4). This formulation also exhibited the highest antibacterial effect, particularly against

Escherichia coli and

Staphylococcus aureus as shown in

Figure 4b. AgNPsE

ETOH-SW and AuNPsE

ETOH-SW showed moderate antioxidant properties (~15-16%) and moderate antimicrobial action, likely due to larger particle sizes and aggregation tendencies. AgNPs from Dandelion (AgNPsEaq-D, AgNPsE

ETOH -D) demonstrated lower antioxidant activity (6-13%), potentially due to a lower retention of flavonoids, and correlating with their weaker antimicrobial effects (

Figure 4a).

4.3.2. Homogeneity, Hydrodynamic Diameter, Zeta Potential, and Shape of Nanoparticles

The presence of polyphenols and flavones in Sweet Wormwood extracts positively impacted the homogeneous formation of nanoparticles and hydrodynamic diameters. Similarly to the gold nanoparticles derived from Dandelion, the average hydrodynamic diameter (DLS) for gold NPs from Sweet Wormwood was larger than that seen in SEM measurements. Gold nanoparticles from both plants contained more phytotherapeutic compounds than silver ones, as confirmed by their increased fluorescence intensity (

Table 1). This suggests a high rutin/polyphenol concentration, contributing to nanoparticle stabilization.

In the absence of nanoparticle purification prior to

DLS analysis, high-molecular-weight compounds may encapsulate nanoparticles, increasing their hydrodynamic distribution. Polysaccharides in Dandelion extracts, known for their antitumor properties, may also contribute to nanoparticle stabilization [

4,

5]. The interaction of these compounds with the nanoparticle surface explains the increased hydrodynamic diameter.

Zeta potential analysis (Table 2) revealed that low zeta potential values (< +30 mV) in some formulations led to flocculation. Moreover, AgNPsEETOH-D had a highly negative zeta potential (-125.82 mV), ensuring strong colloidal stability. Dandelion nanoparticles from aqueous extracts exhibited weaker stability due to insufficient electrostatic repulsion. All nanoparticles had negative charges, suggesting they were surrounded by negatively charged ionic groups, mainly polyphenols, flavones, and phenolic acids. Among Sweet Wormwood-derived nanoparticles, AgNPsEaq-SW exhibited superior stability, while Dandelion nanoparticles (except AgNPsEETOH-D) were more prone to flocculation. The differences in hydrodynamic size and PDI indicate varying encapsulation thickness depending on the concentration and type of phytotherapeutic compounds.

Electron microscopy (SEM/TEM,

Figure 3a-h,

Figures S3 and S5) confirmed the presence of triangular gold nanoparticles in both plant extracts, ranging from 20–35 nm (Table 3), alongside rod-like AuNP structures in Sweet Wormwood with dimensions of 8–15 nm in width and 20–35 nm in length, while larger hydrodynamic diameters observed in DLS measurements were attributed to hydration layers affecting bioactivity, and SEM images revealed that nanoparticles were surrounded by an extract layer, which prevented coalescence and influenced the size measurements

4.3.3. Physico-Chemical Correlations with Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties

Green nanoparticles enhanced DPPH inhibition due to phytocompound adsorption on their surface, facilitating hydrogen donation to free radicals. This was most evident in AgNPsEaq -SW (83.10%), indicating a high antioxidant potential (Table 4). Gold nanoparticles from Sweet Wormwood retained significant polyphenol concentrations but exhibited lower antioxidant activity than AgNPs. This suggests that silver nanoparticles interact more effectively with ROS, enhancing free radical scavenging.

Dandelion-derived AgNPsE

ETOH-D showed significant antibacterial effects against

Escherichia coli, correlating with its highly negative zeta potential (-125 mV). SEM images confirmed large nanoparticles encapsulated in extract layers, contributing to enhanced bacterial interaction (

Figure 4a). Gold nanoparticles (AuNPsE

ETOH-D) also showed antibacterial properties, though weaker than silver. Lower AgNP concentrations generate ROS, disrupting bacterial membranes more effectively than gold. Sweet Wormwood-derived AuNPsE

ETOH-D displayed strong activity against

Staphylococcus aureus (

Figure 4b). Antifungal activity was generally lower (

Figures S6-S7), likely due to structural differences between bacterial and fungal cell walls. Mechanisms influencing antimicrobial effects include: 1. ROS production disrupting bacterial DNA and proteins [

60]; nanoparticle size and shape affecting bacterial uptake [

61]; Biofilm disruption and metabolic interference [

62]; silver ions (Ag

+) binding to bacterial thiol groups, altering enzymatic functions [

63]. The flocculation tendency of D-NPs increased bacterial wall penetration, enhancing antimicrobial activity compared to fungal activity. Additionally, DLS spectra of AgNPsE

ETOH-D (

Figure S4.2(b1)) revealed two hydrodynamic populations, suggesting an aggregation effect impacting bacterial interactions.

The Supplementary Material contains all values for the antimicrobial activity of the tested samples in

Tables S2-S6. Furthermore, recent pharmacological studies have demonstrated the potent anti-inflammatory and anticancer properties of rutin, which was also identified in the majority of our samples, especially those derived from Sweet Wormwood [

64].

4.4. Implications for Biomedical Applications

The combined influence of particle size, morphology, stability, and fluorescence properties suggests distinct biomedical applications. AgNPsEaq-SW exhibited the highest antioxidant and antibacterial activity, making them strong candidates for antimicrobial coatings and wound treatments [

57,

65]. Additionally, triangular AuNPsEaq-D and AuNPsE

ETOH -D demonstrated enhanced cellular uptake, which supports their potential applications in anticancer therapies and selective antibacterial treatments [

56,

66]. Gold nanoparticles derived from Dandelion and Sweet Wormwood extracts exhibited increased fluorescence intensity, likely due to higher phytochemical capping with rutin and polyphenols (

Table 1). This fluorescence-based stability enhancement suggests superior interaction with biological membranes, making these nanoparticles promising for targeted drug delivery applications (

Figure S8, Figure S9). Additionally, the fluorescence signature of AuNPs correlates with their ability to retain bioactive compounds, which could improve their anticancer efficacy through enhanced cellular uptake mechanisms [

59]. Moreover, Dandelion-derived nanoparticles, despite their lower antioxidant activity, exhibited notable antibacterial effects, indicating alternative therapeutic applications, particularly in microbial control and biocompatible formulations. The correlation between fluorescence intensity, nanoparticle stability, and bioactivity aligns with previous studies that emphasize the role of phytochemical-induced fluorescence in nanoparticle stabilization and therapeutic action (

Figure S10, Figure S11) [

55]. The strong fluorescence signals observed in

Figures S8 and S9 confirm the presence of polyphenols and flavonoids surrounding AuNPs, supporting their enhanced biocompatibility and bioactivity. Additionally,

Figures S10 and S11 illustrate how fluorescence intensity variations reflect differences in nanoparticle functionalization, further reinforcing their potential biomedical applications.

4.5. Therapeutic Potential and Statistical Validation of Nanoparticles in Cancer Treatment

4.5.1. Cytotoxic Analysis

CisPt and DOX appear to impact the investigated tumor lines; however, their effects also extended to the normal cell line after 24 hours (

Figure 5a). Meanwhile, after 24 hours the ethanolic extract of Sweet Wormwood reduced the viability of breast tumor cells, an effect not evident in the other cell lines. In the case of AgNPsE

ETOH -D and AgNPsE

ETOH -SW (with a final colloidal solution containing 3% ethanol), there was a slight reduction in cell viability compared to treatment with the extract alone. Silver nanoparticles from Dandelion demonstrated a significant antitumor effect on colon tumor cells (LoVo) after 24 hours (χ² = 58.428; p = 2.56e-11) and 48 hours, showing a greater impact than CisPt (

Figure 5a and 5b). Notably, AgNPsE

ETOH3%-D showed a higher cytotoxicity than CisPt (p = 4.58e-3), whereas AuNPsEaq-D exhibited a weaker cytotoxic effect (p = 1.82e-3). Gold and silver NPs derived from Dandelion extracts effectively targeted the breast tumor cell line (MDA-MB) with superior efficacy compared to DOX (χ² = 42.035; p = 5.79e-8). AgNPsEEOTH3%-SW exhibited the highest cytotoxicity (p = 1.43e-8), followed by AgNPsEEOTH3%-D (p = 7.20e-5) and AuNPsEEOTH3%-D (p = 4.72e-4). These nanoparticles significantly surpassed DOX in tumor cell inhibition while maintaining normal cell viability.

After 48 hours, AgNPsE

ETOH-SW influenced the breast tumor cell line without impacting normal cells (

Figure 5a,b). The

EETOH30%-SW extract demonstrated higher cytotoxicity than DOX (p = 4.58e-3), confirming its potential as a therapeutic agent.

Other studies have also shown a strong antitumor effect of biosynthesized AgNPs, particularly on breast tumor cell lines [

67,

68]. Additionally, polyphenols from the

Artemisia annua extract have shown anticancer activity in highly metastatic breast cancer cells (MDA MB-231) [

69].

Regarding the liver tumor line, HepG2, the high concentrations of the analyzed samples had a substantial antitumor effect (χ² = 105.868; p = 1.67e-19), especially in the case of the 30% alcoholic wormwood extract (p = 1.59e-9 compared to CisPt). The effect became much more pronounced after 48 hours, showing a stronger cytotoxic impact than CisPt (

Figure 5c).

Silver nanoparticles from wormwood (aqueous and alcoholic extracts) also exhibited significant antitumor effects on HepG2 liver tumor cells, though slightly weaker than those of the wormwood extract. Notably, AuNPsEEOTH5%-SW (p = 9.19e-9 vs. CisPt) and AgNPsEaq-D (p = 3.49e-9 vs. CisPt) demonstrated a considerable reduction in tumor cell viability. Artemisinin, the phytotherapeutic compound in wormwood, has been widely recognized for its antimalarial and antitumor effects. Drug delivery systems based on artemisinin have already been developed to efficiently and selectively target specific tumor cell lines [

70]. Utilizing synergistic effects, green-synthesized nanoparticles from Sweet Wormwood extracts could be a promising strategy to enhance controlled phytoconstituent delivery while minimizing toxicity risks.

4.5.1. Statistical Analysis

The cytotoxic effects of the tested compounds on different cell lines were statistically analyzed and summarized in Table 5. The Chi-Square (χ²) test results indicate significant differences between the tested treatments and standard chemotherapeutics across all analyzed cell lines, with high χ² values and extremely low p-values confirming that the cytotoxic effects of the green-synthesized nanoparticles. This table presents the comparative performance of the studied formulations against control treatments (Cis-Pt and DOX), highlighting statistically significant differences in cytotoxicity. The results indicate that silver nanoparticles from Dandelion and Sweet Wormwood extracts exhibited strong antitumor activity, particularly against MDA-MB-231 and LoVo cell lines, while maintaining lower toxicity towards normal cells (HUVEC). Notably, ethanolic wormwood extract (30%) demonstrated superior efficacy in targeting HepG2 liver cancer cells, outperforming Cis-Pt. These findings further support the potential of plant-based nanoparticles as promising alternatives in cancer therapy.

4.5.2. Comparative Analysis of IC50 and Selectivity Index at 24h and 48h

The comparative analysis of the IC50 values and selectivity indices at 24h and 48h reveals significant changes in the cytotoxicity and specificity of the tested compounds (

Table S7 and S8 and

Figure 6). A notable decrease in IC50 values over time is observed for most compounds, particularly E

EOTH30% - SW and AuNPsEaq - D, indicating an increase in their potency on cancer cells. This trend is especially pronounced in the case of MDA-MB cells, where E

ETOH30% - SW shows a drastic reduction in IC50 from 0.06848 (24h) to 0.02412 (48h), while AuNPsE

aq - D decreases from 0.21951 to 0.02800, suggesting a much stronger effect with prolonged exposure. In contrast, AgNPsE

ETOH3%- SW exhibits a loss of selectivity for MDA-MB over time, as its IC50 increases from 0.04909 (24h) to 0.21758 (48h), resulting in a significant drop in its selectivity index from 2.21 to 0.37. This suggests that its cytotoxic effect on cancer cells diminishes with prolonged exposure. Meanwhile, AgNPsE

ETOH3% - D maintains a stable IC50 for LoVo and sees an improvement in selectivity for MDA-MB, with the selectivity index increasing from 1.32 (24h) to 2.56 (48h), indicating an enhancement in its specificity towards breast cancer cells. Among all tested compounds, AuNPsEaq - D demonstrates the most remarkable shift in selectivity, with its selectivity index for MDA-MB skyrocketing from 0.31 at 24h to 8.41 at 48h, making it the most promising candidate for targeted breast cancer therapy. This drastic increase suggests that AuNPsEaq - D preferentially kills cancer cells while sparing normal HUVEC cells, a crucial characteristic of an effective anticancer agent. Similarly, E

ETOH30%- SW also improves in selectivity over time, with its selectivity index for MDA-MB increasing from 5.92 (24h) to 7.51 (48h), reinforcing its potential for cancer treatment. On the other hand, Cis-Pt continues to show poor selectivity across both time points, with a consistently low selectivity index for LoVo (0.14 at 24h and 0.12 at 48h) and no selectivity for MDA-MB, confirming its known broad cytotoxicity against both cancerous and healthy cells. These results suggest that while Cis-Pt remains a standard chemotherapy agent, the newly tested compounds, particularly AuNPsE

aq - D and E

ETOH30%- SW, offer more promising alternatives with improved selectivity and reduced side effects on normal cells. Overall, the 48-hour data provides strong evidence that AuNPsE

aq - D and E

ETOH30%- SW are the most effective and selective treatments for MDA-MB cells, while AgNPsE

ETOH30% - D also shows improved potential. The best samples for HepG2-targeted therapy based on SI values are E

ETOH30% -SW and AgNPsE

ETOH5% -D, which show the highest selectivity. Cis-Pt has lower selectivity than some of these nanoparticles, suggesting potential for replacing or combining nanoparticles with standard chemotherapies. Further in vivo studies and normal cell toxicity assessments are needed to validate clinical relevance. The enhanced selectivity over time suggests that these compounds may work more efficiently with prolonged exposure, supporting their potential for further preclinical and clinical studies. Future research should focus on mechanistic studies to understand the pathways involved in their cytotoxic effects and confirm their selectivity using additional cancer models.

4.5.3. The Potential Antitumoral Mechanism

Comparing the gold nanoparticles from

Taraxacum officinale (dandelion) with those from

Artemisia annua (sweet wormwood), we can observe that dandelion-derived nanoparticles exhibit a stronger anticancer effect, despite their lower antioxidant activity. This difference can be explained by several factors related to morphology, stability, and specific cellular mechanisms. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) from dandelion have a triangular morphology, which provides a higher surface-to-volume ratio compared to spherical nanoparticles. This results in: 1. stronger interaction with tumor cell membranes; 2. increased penetration of cancer cells through endocytosis or more intense contact with biomolecules; 3. influencing intracellular processes[

71]. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) from

Artemisia annua are more stable and have a spherical shape, making them less reactive in their interaction with tumor cells.

Gold nanoparticles from dandelion (AuNPsEaq-D and AuNPsEETOH-D), despite not exhibiting strong antioxidant properties, can induce specific oxidative stress in cancer cells. They can disrupt the redox balance of tumor cells, which are already characterized by high oxidative stress levels. Gold nanoparticles are known to interact with mitochondria and deregulate the energetic metabolism of cancer cells [

72]. Silver nanoparticles from

Artemisia annua (AgNPsEaq-SW, AgNPsE

ETOH-SW) exhibit higher antioxidant activity (e.g., AgNPsEaq-SW = 83.10%), suggesting that they may reduce oxidative stress rather than amplify it, which could limit their anticancer potential. Another crucial factor is the instability of dandelion-derived gold nanoparticles, which makes them more reactive in biological environments. This instability results in a faster release of gold ions, allowing for enhanced interactions with proteins and nucleic acids inside cancer cells. In contrast, silver nanoparticles from

Artemisia annua are more stable and therefore may have a slower or less aggressive anticancer action. Finally, the bioactive compounds present in

Taraxacum officinale, such as flavonoids and terpenoids, work synergistically with gold nanoparticles to amplify oxidative stress and induce apoptosis [

73]. While

Artemisia annua contains artemisinin, a compound known for its reactive oxygen species (ROS)-generating effects, its mechanism relies on iron metabolism, which may not be as effective in combination with silver nanoparticles [

74]. The AuNPsEaq-D and AuNPsE

ETOH-D exhibit higher selectivity for cancer cells compared to DOX, meaning they effectively target tumor cells without harming normal cells. This selective action can be explained by several factors: cancer cells are more susceptible to ROS stress than normal cells, making AuNPs more effective in targeting tumors [

75]; nanoparticles enter cancer cells more efficiently than normal cells, reducing off-target effects; normal cells have stronger antioxidant defenses, protecting them from AuNP-induced stress; unlike DOX, AuNPs do not directly bind to DNA or interfere with normal cell division, reducing systemic toxicity [

76].

Silver nanoparticles derived from Taraxacum officinale (AgNPsEETOH-D) exhibit superior anticancer effects against LoVo colon cancer cells, demonstrating greater efficacy than CisPt. This enhanced effectiveness can be attributed to their unique physicochemical properties, which allow for increased cellular uptake, oxidative stress induction, and apoptosis activation, while minimizing toxicity to healthy cells. In contrast, silver nanoparticles from Artemisia annua (AgNPsEaq-SW) show comparable anticancer effects to Cis-Pt, but with a significantly higher safety profile, reducing the risk of adverse side effects commonly associated with chemotherapy. These findings suggest that silver nanoparticles from Dandelion and Sweet Wormwood may serve as promising alternatives or complementary agents to conventional colon cancer treatments. Also other study revealed the importance of the green nanoparticles in

The EETOH30% -SW demonstrates high anticancer efficacy, showing significant cytotoxic effects after 48 hours, ultimately surpassing CisPt in its ability to reduce cancer cell viability. This effect can be attributed to the high content of bioactive compounds, particularly artemisinin, which is known to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) selectively in cancer cells, disrupting their redox balance and leading to apoptosis. Additionally, the presence of flavonoids and terpenoids enhances oxidative stress, further impairing tumor cell survival.

Similarly, the AgNPsEETOH3%-SW (Sweet Wormwood silver nanoparticles) induce a substantial decrease in cancer cell survival while exhibiting no toxic effects on normal cells, a selectivity likely driven by the differential redox environment of cancer versus normal cells. Cancer cells, which already experience higher baseline oxidative stress, are more susceptible to ROS-mediated damage induced by silver nanoparticles, whereas normal cells possess stronger antioxidant defense mechanisms that protect them from oxidative stress-related damage. Moreover, the nanoparticles interact with mitochondrial membranes, further destabilizing cancer cell metabolism and triggering apoptosis, making them a promising and selective alternative to conventional chemotherapy, with reduced systemic toxicity compared to CisPt.

The following schematic representation highlights the key mechanisms of nanoparticle action on cancer cell lines, including cellular uptake, ROS generation, DNA damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis induction, demonstrating their selective cytotoxicity and potential as targeted cancer therapies with reduced toxicity compared to DOX and CisPt.

Figure 7.

Selectivity Index and Mechanisms of Action of Green-Synthesized Nanoparticles Compared to Conventional Chemotherapeutic Agents.

4.6. Limitations of the Study

Despite the promising findings, this study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the long-term environmental and biological effects of green nanoparticles remain largely unexplored, requiring extended studies to assess their bioaccumulation potential and degradation pathways. Additionally, while in vitro experiments provide valuable insights into cytotoxicity and antimicrobial efficacy, they do not fully replicate the complex interactions occurring within living organisms, necessitating in vivo studies for a more comprehensive evaluation. Furthermore, variations in plant-derived bioactive compounds used for nanoparticle synthesis may lead to inconsistencies in physicochemical properties, potentially affecting reproducibility and large-scale production. Another limitation is the lack of detailed mechanistic studies on nanoparticle interactions at the molecular level, which are essential for understanding their potential risks and therapeutic applications. Lastly, while this study emphasizes the eco-friendly nature of green nanoparticles, a full life-cycle assessment is required to determine their overall sustainability, including energy consumption, waste generation, and long-term ecological footprint.

5. Conclusions

Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Potential: AgNPsEaq-SW demonstrated the highest antioxidant and antibacterial activity, making it a strong candidate for wound healing and antimicrobial coatings.

Selective Cytotoxicity and Fluorescence-Based Stability: triangular AuNPsEaq-D and AuNPsEETOH-D showed enhanced cellular uptake, supporting their potential use in anticancer therapies, while fluorescence signals confirmed the role of polyphenols in nanoparticle stabilization.

Bioactivity Correlations: the observed fluorescence intensity and stability trends in AuNPs correlate with their ability to retain bioactive compounds, improving their targeted therapeutic potential.

Dandelion-Derived Nanoparticles: despite lower antioxidant activity, they displayed notable antibacterial effects, highlighting their potential in microbial control applications.

Influence of Ethanol Percentage: The presence of ethanol at 3% and 5% concentrations significantly influenced nanoparticle formation, stability, and biological activity. Ethanol enhanced flavonoid extraction, leading to higher polyphenol content and increased fluorescence stability. However, ethanol also impacted nanoparticle aggregation and colloidal stability, with higher ethanol content (5%) favoring smaller, more stable nanoparticles, whereas lower ethanol (3%) resulted in moderate aggregation but retained bioactive compounds more effectively.

In Vivo Testing for Therapeutic Validation: further research should evaluate the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and toxicity of these nanoparticles in animal models.

Optimization for Drug Delivery: enhancing targeted delivery mechanisms using functionalized nanoparticles could improve their selectivity in cancer therapy.

Exploring Synergistic Effects: Investigating combination therapies with existing antibiotics and chemotherapeutic agents may enhance their efficacy while reducing resistance. Our previous study demonstrated the synergistic effect of green nanoparticles in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs on HepG2 cells, supporting further investigations into other tumor cell lines [

77].

Further Ethanol Influence Studies: More research should explore optimal ethanol concentrations for maximizing nanoparticle stability, bioactivity, and therapeutic efficiency, while minimizing aggregation effects.

Life Cycle Impact of Green Nanoparticles: Green nanoparticle synthesis offers a more sustainable approach, minimizing toxic waste and energy consumption while enhancing environmental and biological safety. Compared to conventional methods, AgNPs have a greener life cycle, reducing pollution, energy use, and potential toxicity. However, while their organic coatings degrade naturally, the metallic cores may persist, highlighting the need for further studies on their long-term fate and environmental interactions. Additionally, scalability remains a challenge, requiring optimization of biological synthesis for industrial applications without compromising nanoparticle quality.

This study highlights the potential of plant-based nanoparticles as multifunctional therapeutic agents, with antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer applications. The comparison with conventional drugs such as Cis-Pt and DOX suggests that these nanoparticles could serve as alternative or complementary agents in chemotherapy, with potentially lower systemic toxicity. Future studies should focus on enhancing stability, optimizing formulations for targeted delivery, and validating in vivo efficacy to bring these nanoparticles closer to clinical applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author contributions statement

M.C.R. conceptualized and designed the study, conducted experiments, analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. D.C. conducted experiments, contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and assisted in writing. M.S. designed and performed experiments and contributed to the original draft. A.G. performed statistical analysis, interpreted data, secured funding, and participated in writing. M.A.M. carried out experiments, optimized methodology, validated results, and drafted the manuscript. M.L.G. contributed to methodology, data analysis, and drafting. V.O. conceptualized the study, oversaw visualization, and supervised the project. M.P. organized data and contributed to experimental design and acquisition. V.Ț. conducted experiments, contributed to visualization, and drafted the manuscript. I.M., O.B., A.B., V.A. conducted experiments, optimized methods, and contributed to the draft. C.E.M. performed statistical analysis and supported experiments. R.C.S. supervised the project and validated results. M.C. organized data and supported data acquisition. A.T.-Ș. and E.A. contributed to conceptualization and statistical analysis. V.E.P. conducted experiments and drafted the manuscript. C.T. supervised and validated results. B.F. acquired funding, conducted experiments, and coordinated the project. C.M.M. contributed to conceptualization, conducted core experiments, drafted the manuscript, and managed final approvals.All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Research funding

This work was supported by Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization, Core Program µNanoEl “Advanced research in micro–nano electronic and photonic devices, sensors and microsystems for societal applications”, cod 2307 and also was co-funded under grant agreement No.101140192, project UNLOOC (Unlocking data content of Organ-On-Chips) and supported by the CHIPS Joint Undertaking and its members.

Ethics and Consent

This study did not involve human subjects, animal experiments, or data obtained from social media platforms. As such, ethics approval and informed consent were not applicable. The authors affirm that all relevant ethical guidelines were followed.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon justified request.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- R.C. Sandulovici, M.L. Gălăţanu, L.M. Cima, E. Panus, E. Truţă, C.M. Mihăilescu, I. Sârbu, D. Cord, M.C. Rîmbu, Ş.A. Anghelache, M. Panţuroiu, Phytochemical Characterization, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Activity of the Vegetative Buds from Romanian Spruce, Picea abies (L.) H. Karst., Molecules 29 (2024) 2128. [CrossRef]

- P. Laganà, G. Anastasi, F. Marano, S. Piccione, R.K. Singla, A.K. Dubey, S. Delia, M.A. Coniglio, A. Facciolà, A. Di Pietro, M.A. Haddad, M. Al-Hiary, G. Caruso, Phenolic Substances in Foods: Health Effects as Anti-Inflammatory and Antimicrobial Agents, J AOAC Int. 102 (2019) 1378–1387. [CrossRef]

- H. Rasouli, M.H. Farzaei, R. Khodarahmi, Polyphenols and their benefits: A review, Int. J. Food Prop. (2017) 1–42. [CrossRef]

- M. Fan, X. Zhang, H. Song, Y. Zhang, Dandelion (Taraxacum Genus): A Review of Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Effects, Molecules 28 (2023) 5022. [CrossRef]

- A.G. Durán, C. Rial, M.T. Gutiérrez, J.M.G. Molinillo, F.A. Macías, Sesquiterpenes in Fresh Food, in: Handbook of Dietary Phytochemicals, Springer Singapore, Singapore, 2021: pp. 477–542. [CrossRef]

- T. Esatbeyoglu, B. Obermair, T. Dorn, K. Siems, G. Rimbach, M. Birringer, Sesquiterpene Lactone Composition and Cellular Nrf2 Induction of Taraxacum officinale Leaves and Roots and Taraxinic Acid β - D -Glucopyranosyl Ester, J. Med. Food 20 (2017) 71–78. [CrossRef]

- T. Kikuchi, A. Tanaka, M. Uriuda, T. Yamada, R. Tanaka, Three Novel Triterpenoids from Taraxacum officinale Roots, Molecules 21 (2016) 1121. [CrossRef]