Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

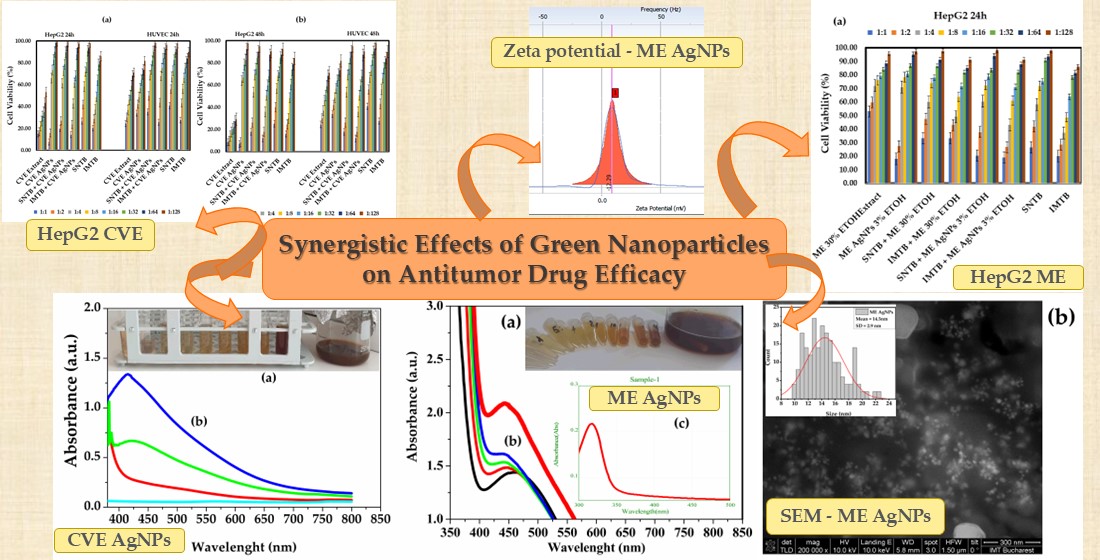

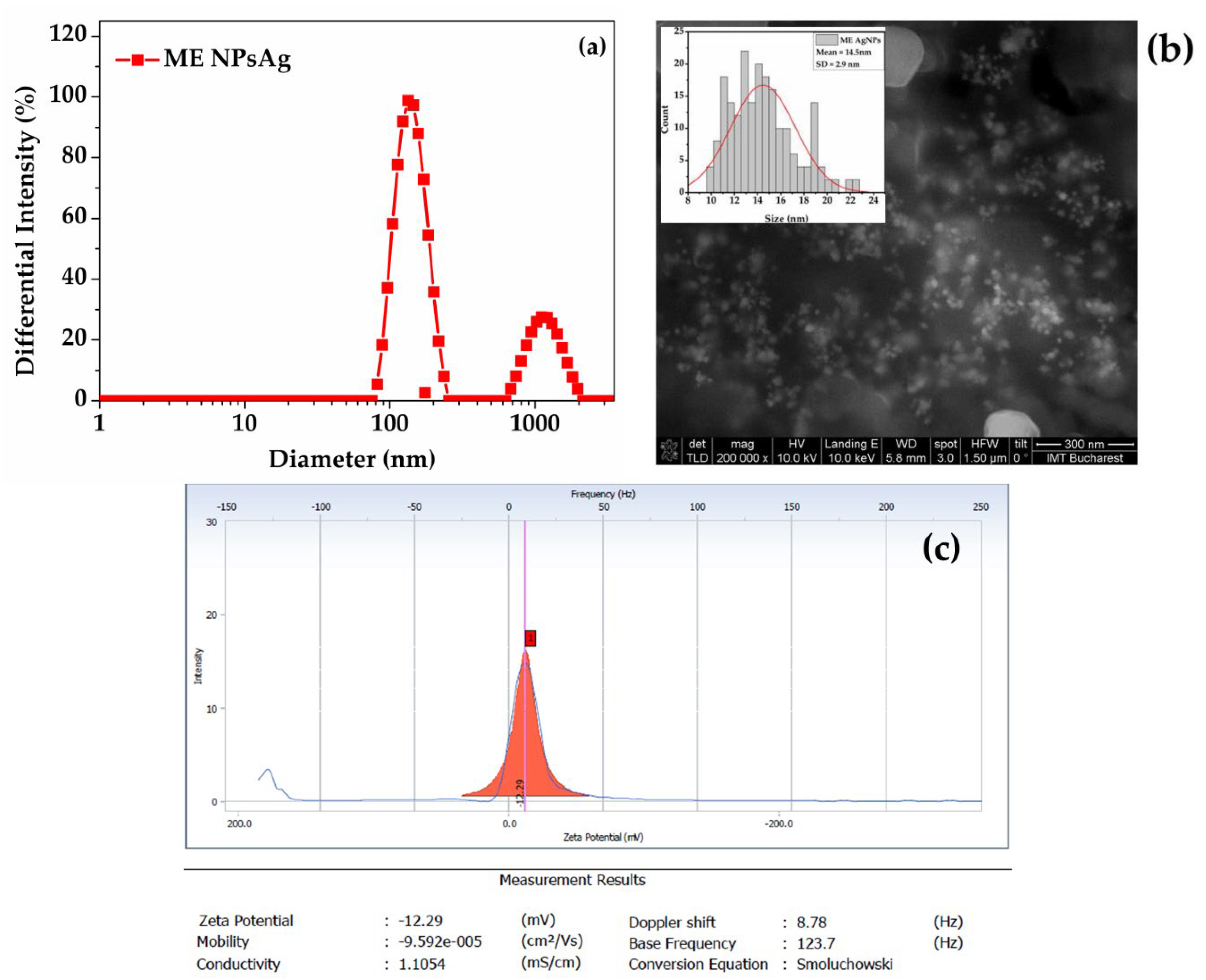

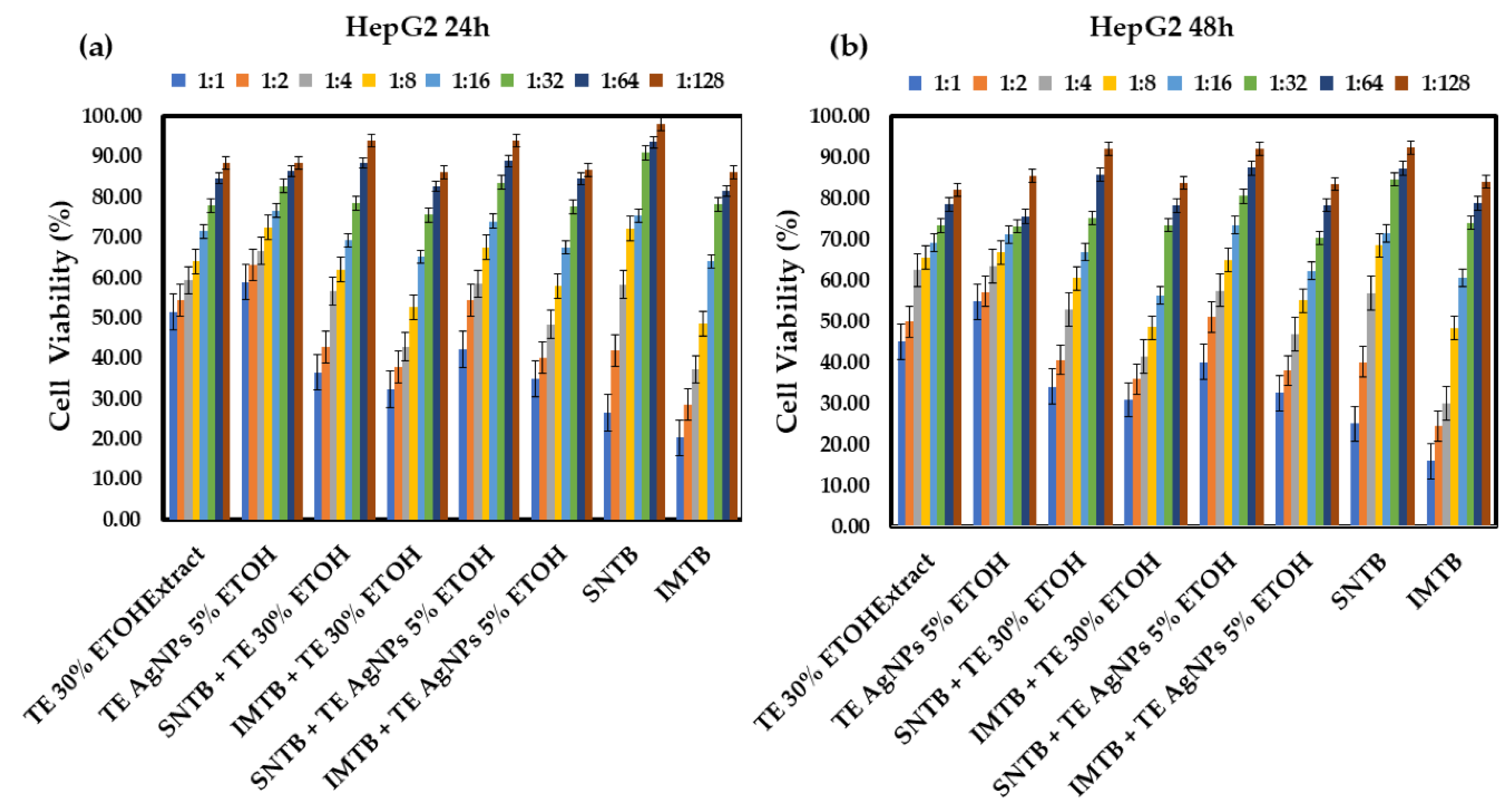

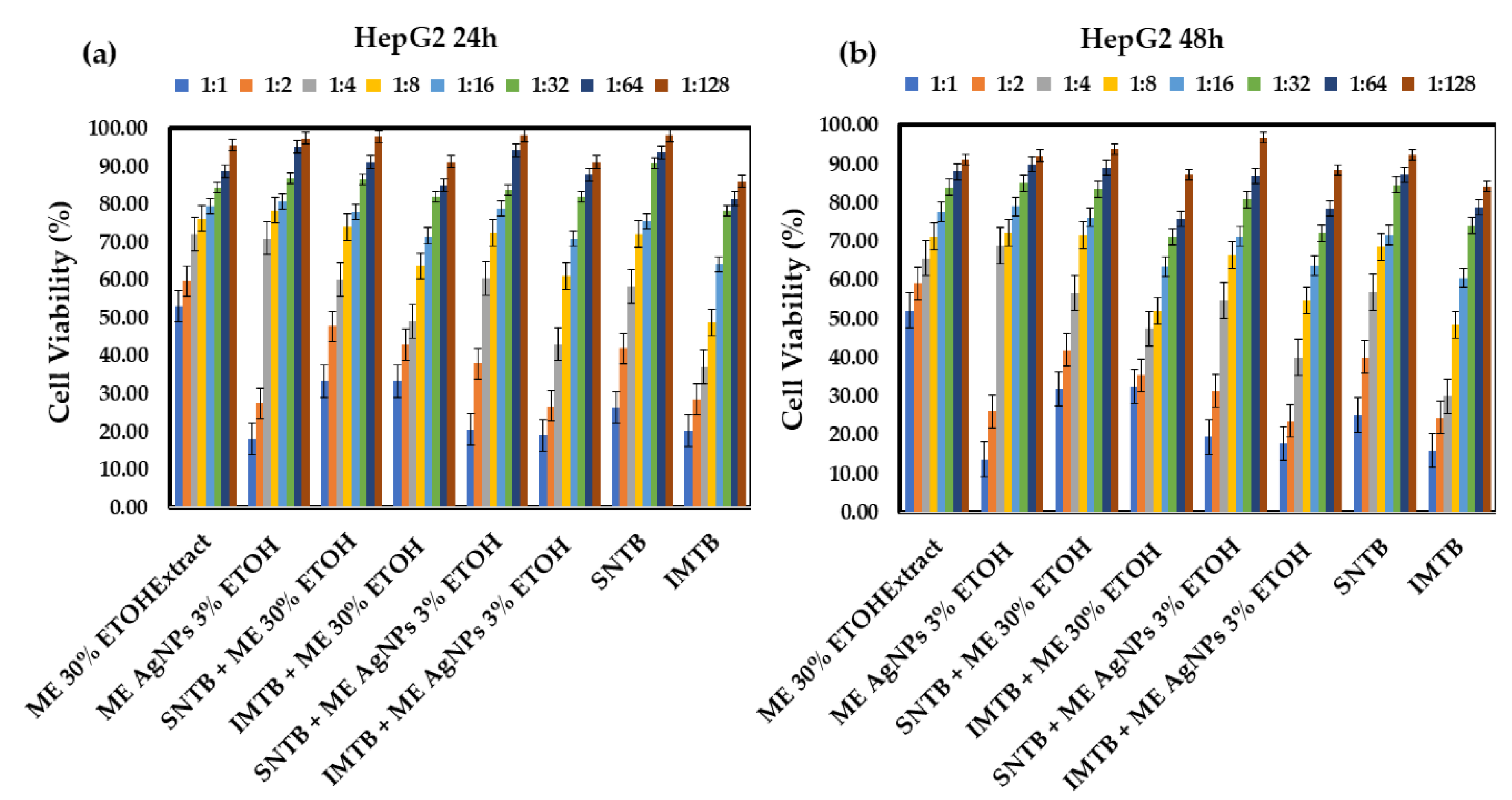

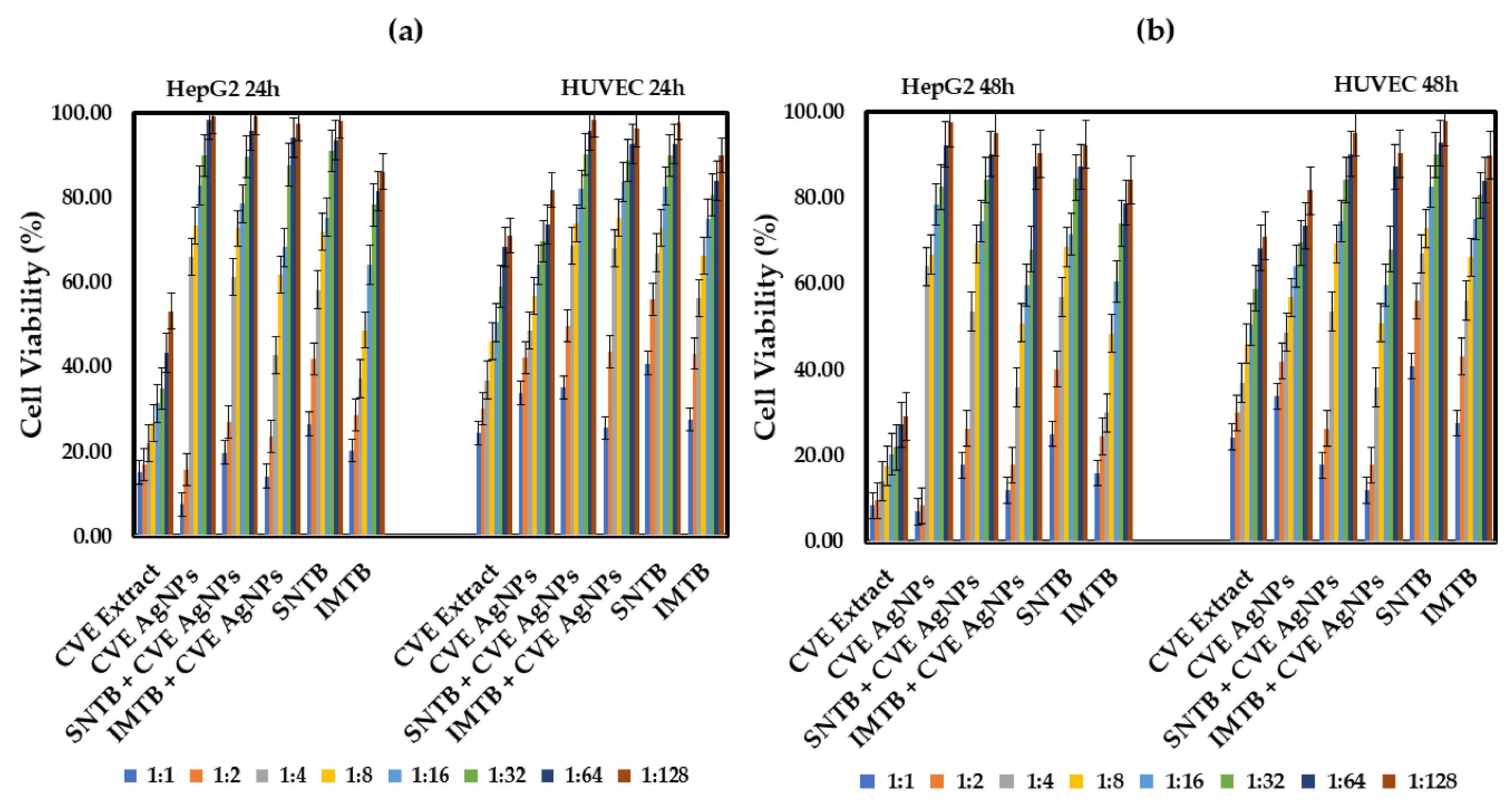

Cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, and despite significant advances in treatment plans and drug development, survival prospects are still low, and treatment side effects are life altering. This article examines plant-derived extracts and their therapeutic potential against various types of hepatocellular carcinoma as a means of inducing fewer side effects compared to existing treatments. The focus is on the in vitro synergistic effect of silver bio-nanoparticles obtained from Clematis vitalba, Melissa officinalis, and Taraxacum officinale extracts (Clematis vitalbae extractum—CVE, Melissae extractum—ME, Taraxaci extractum—TE), alongside important drugs employed in liver cancer treatments (sunitinib—SNTB and imatinib—IMTB), and their effect on HepG2 cell lines (human hepatocellular carcinoma) and normal HUVEC cell lines (human umbilical vein endothelial cells). The nanoparticles (AgNPs) were characterized in terms of their dimensions, maximum absorption, and stability in solutions using techniques such as UV-Vis, DLS, zeta potential, and SEM. Meanwhile, antitumor effect was determined based on the viability of the HepG2 cells after 24 and 48 hours of treatment with each extract, mixtures of extracts with nanoparticles, and combinations of the extracts with antitumor drugs. Tests were repeated on the HUVEC cell line to determine normal cell toxicity. M. officinalis-derived silver nanoparticles (ME AgNPs) and the Clematis vitalba extract with silver nanoparticles (CVE AgNPs) significantly reduced HepG2 cell viability, enhancing efficacy when combined with conventional therapies (SNTB + ME AgNPs 1:1 vs SNTB: 20.01% vs 25.73% (p = 0.002), IMTB + ME AgNPs 1:1 vs IMTB: 17.80% vs 18.08% (p = 0.036); SNTB + CVE AgNPs 1:1 vs SNTB: 18.73% vs 25.73% (p = 0.000), SNTB + CVE AgNPs 1:2 vs SNTB: 26.62% vs 41.00% (p = 0.018), IMTB + CVE AgNPs 1:1 vs IMTB: 12.99% vs 18.08% (p = 0.001)). In contrast, the Taraxacum extract showed comparable cytotoxicity to its silver nanoparticles but did not exceed the efficacy of the extract alone after 24 hours. Of the three extracts, CVE demonstrated the most potent antitumor effect, resulting in an increase in the anticancer efficacy of the synthetic drug with remarkable therapeutic benefits in the fight against cancer. The findings of this study highlight the promising potential of plant-derived silver bio-nanoparticles to enhance the efficacy of conventional liver cancer treatments, paving the way for future research into more effective and less toxic therapeutic options.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Plant Extracts Preparation

2.2. Silver Nanoparticle Biosynthesis

2.3. Physical-Chemical Characterization Methods of Nanoparticles

2.4. Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Cell Cultures and Treatments - In Vitro Antitumoral Tests

- MTS-Based Cytotoxicity Assay

2.5. Preparation of In Vitro-Tested Samples

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

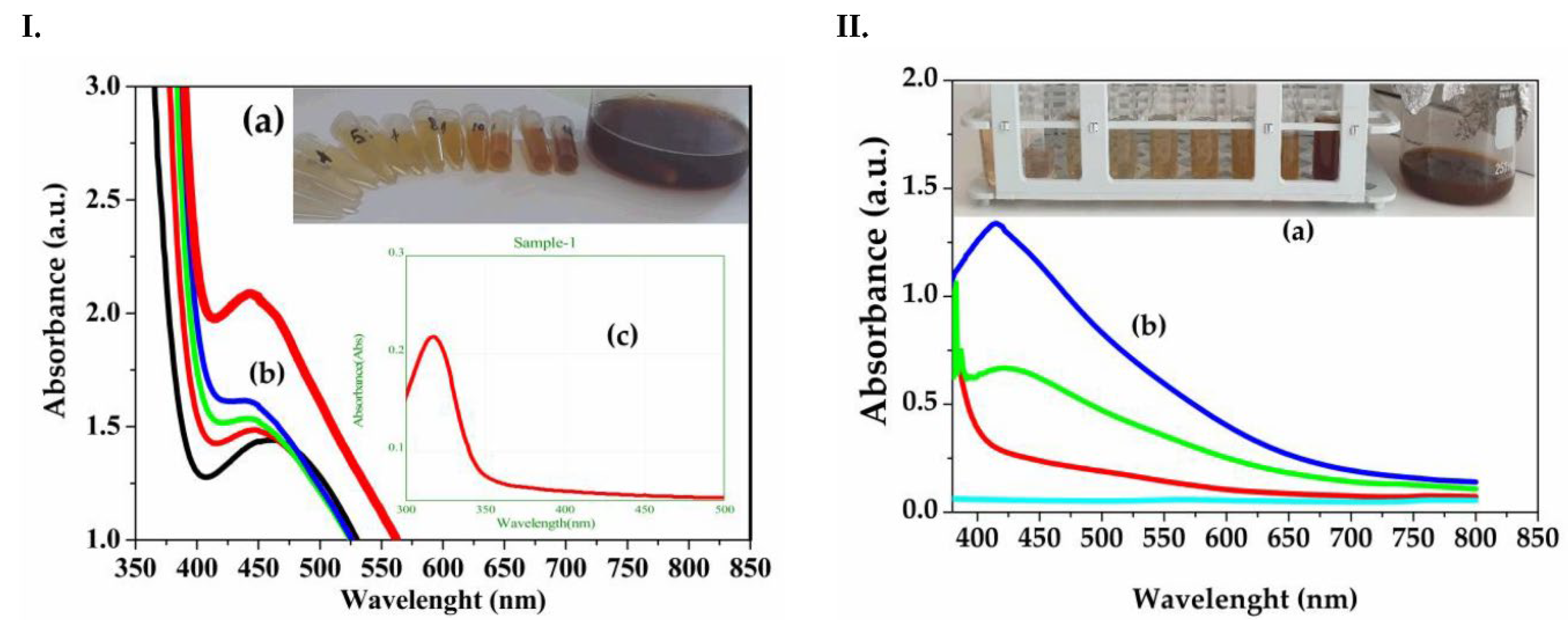

3.1. Physical-Chemical Nanoparticles Characterization

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Zeta Potential, and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

3.2. In vitro Antitumoral Studies

- Taraxaci extractum (TE) - based samples

- Melissae extractum (ME) - based samples

- Clematis vitalbae extractum (CVE) - based samples

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ritter J.M., Robinson E., Fullerton J., Flower R.J., Henderson G., Loke Y.K., MacEwan D. - Rang & Dale's Pharmacology, Tenth Edition, Elsevier eBooks, London, U.K., 2024; pp. 764–782.

- Cosme, P., Rodríguez, A. B., Espino, J., & Garrido, M. (2020). Plant phenolics: Bioavailability as a key determinant of their potential health-promoting applications. Antioxidants, 9(12), 1263. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9121263.

- Linnewiel-Hermoni, K., Khanin, M., Danilenko, M., Zango, G., Amosi, Y., Levy, J., & Sharoni, Y. (2015). The anti-cancer effects of carotenoids and other phytonutrients resides in their combined activity. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics, 572, 28-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2015.02.018.

- Habli, Z., Toumieh, G., Fatfat, M., Rahal, O. N., & Gali-Muhtasib, H. (2017). Emerging cytotoxic alkaloids in the battle against cancer: Overview of molecular mechanisms. Molecules, 22(2), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22020250.

- Shrihastini, V., Muthuramalingam, P., Adarshan, S., Sujitha, M., Chen, J. T., Shin, H., & Ramesh, M. (2021). Plant derived bioactive compounds, their anti-cancer effects and in silico approaches as an alternative target treatment strategy for breast cancer: An updated overview. Cancers, 13(24), 6222. doi: 10.3390/cancers13246222.

- Dehelean, C. A., Marcovici, I., Soica, C., Mioc, M., Coricovac, D., Iurciuc, S., et al. (2021). Plant-derived anticancer compounds as new perspectives in drug discovery and alternative therapy. Molecules, 26(4), 1109. doi: 10.3390/molecules26041109.

- Costea, L., Ghica, M., Costea, T., & Gird, C. E. (2021). Spectrophotometric evaluation of flavonoids, phenolcarboxylic acids and total phenolic contents of several indigenous herbal products with potential hepatoprotective effect. Farmacia, 69(6). https://doi.org/10.31925/farmacia.2021.6.23.

- Costea, L., Chițescu, C. L., Boscencu, R., Ghica, M., Lupuliasa, D., Mihai, D. P., et al. (2022). The polyphenolic profile and antioxidant activity of five vegetal extracts with hepatoprotective potential. Plants, 11(13), 1680. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11131680.

- Saratale, R. G., Benelli, G., Kumar, G., Kim, D. S., & Saratale, G. D. (2018). Bio-fabrication of silver nanoparticles using the leaf extract of an ancient herbal medicine, dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), evaluation of their antioxidant, anticancer potential, and antimicrobial activity against phytopathogens. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25, 10392-10406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-9581-5.

- Ren, F., Wu, K., Yang, Y., Yang, Y., Wang, Y., & Li, J. (2020). Dandelion polysaccharide exerts anti-angiogenesis effect on hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating VEGF/HIF-1α expression. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 11, 460. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.00460.

- Ren, F., Zhang, Y., Qin, Y., Shang, J., Wang, Y., Wei, P., et al. (2022). Taraxasterol prompted the anti-tumor effect in mice burden hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating T lymphocytes. Cell Death Discovery, 8(1), 264. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-022-01059-5.

- Rehman, G., Hamayun, M., Iqbal, A., Khan, S. A., Khan, H., Shehzad, A., et al. (2017). Effect of methanolic extract of dandelion roots on cancer cell lines and AMP-activated protein kinase pathway. Frontiers in pharmacology, 8, 875. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2017.00875.

- Ren, F., Li, J., Yuan, X., Wang, Y., Wu, K., Kang, L., et al. (2019). Dandelion polysaccharides exert anticancer effect on Hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and enhancing immune response. Journal of Functional Foods, 55, 263-274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2019.02.034.

- Moacă, E. A., Farcaş, C., Ghiţu, A., Coricovac, D., Popovici, R., Cărăba-Meiţă, N. L., et al. (2018). A comparative study of Melissa officinalis leaves and stems ethanolic extracts in terms of antioxidant, cytotoxic, and antiproliferative potential. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2018(1), 7860456. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7860456.

- Luță, E. A., Biță, A., Moroșan, A., Mihăiescu, D. E., Ghica, M., Mihai, D. P., et al. (2022). The influence of phytosociological cultivation and fertilization on polyphenolic content of Menthae and Melissae folium and evaluation of antioxidant properties through in vitro and in silico methods. Plants, 11(18), 2398. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11182398.

- Mohammed A., Waleed A., Al-Khafaji K., Abid M.M, Kadhom M., Alhaydary E., Yousif E. - Comprehensive analysis of anticancer activities in Melissa officinalis extract: Gas chromatography profiling, biological assessment, network pharmacology, and molecular docking, 2025, Letters in Applied NanoBioScience, 14(1), 15. doi:10.33263/LIANBS141.012.

- Dehghan-Nayeri, N., Darvishi, M., Mashati, P., Rezapour-Kalkhoran, M., Rezaiefard, M., & Younesian, S. (2020). Comparison of cytotoxic activity of herbal extracts on the most commonly used breast cancer cell lines (MCF7 and SKBR3): A systematic review. Journal of Research in Pharmacy, 24(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.35333/jrp.2020.121.

- Encalada, M. A., Hoyos, K. M., Rehecho, S., Berasategi, I., de Ciriano, M. G. Í., Ansorena, D., et al. (2011). Anti-proliferative effect of Melissa officinalis on human colon cancer cell line. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 66, 328-334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11130-011-0256-y.

- Jun, H. J., Roh, M., Kim, H. W., Houng, S. J., Cho, B., Yun, E. J., et al. (2011). Dual inhibitions of lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) ethanolic extract on melanogenesis in B16-F1 murine melanocytes: Inhibition of tyrosinase activity and its gene expression. Food science and biotechnology, 20, 1051-1059. doi: 10.1007/s10068-011-0143-1.

- Niu, C., & Aisa, H. A. (2017). Upregulation of melanogenesis and tyrosinase activity: Potential agents for vitiligo. Molecules, 22(8), 1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22081303.

- Shamseini, M., Mohammadi, M., Shirazi, F. H., Andalib, S., Gholami, S., Hosseini, S. H., et al. (2019). Prevention of liver cancer by standardized extract of Melissa officinalis L. in a rat model of hepatocellular carcinoma: Its potential role as a chemopreventive agent. International Pharmacy Acta, 2(1), 2e8-1. https://doi.org/10.22037/ipa.v2i1.23970.

- Yoo, G., Kim, M., Randy, A., Son, Y. J., Hong, C. R., & Nho, C. W. (2019). Lemon balm extract and its major chemical compound, rosmarinic acid, alleviate damages of liver in an animal model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)(P06-093-19). Current Developments in Nutrition, 3, nzz031-P06. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzz031.P06-093-19.

- Sammar, M., Abu-Farich, B., Rayan, I., Falah, M., & Rayan, A. (2019). Correlation between cytotoxicity in cancer cells and free radical-scavenging activity: In vitro evaluation of 57 medicinal and edible plant extracts. Oncology Letters, 18(6), 6563-6571. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2019.11054.

- Yesilada, E., & Küpeli, E. (2007). Clematis vitalba L. aerial part exhibits potent anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive and antipyretic effects. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 110(3), 504-515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.016.

- Șuțan, N. A., Popescu, D. I., Drăghiceanu, O. A., Topală, C., Şuţan, C., Negrea, A. D., et al. (2023). In vitro cytotoxic activity of phytosynthesized silver nanoparticles using Clematis vitalba L. (Ranunculaceae) aqueous decoction. Caryologia, 76(2), 67-81. https://doi.org/10.36253/caryologia-2330.

- Şuțan, N.A.; Dobrescu, C.M.; Drăghiceanu, O.A.; Fierăscu, I.; Fierăscu, R.C.; Şuțan, C.; Soare, L.C. (2022). Phytotoxicity of Clematis vitalba L. (Ranunculaceae) aqueous extract and nanostructured mixture. Chem. Proc., 7, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemproc2022007021.

- Buzzini, P., & Pieroni, A. (2003). Antimicrobial activity of extracts of Clematis vitalba towards pathogenic yeast and yeast-like microorganisms. Fitoterapia, 74(4), 397-400. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0367-326x(03)00047-9.

- Sandulovici, R. C., Mihăilescu, C. M., Grigoroiu, A., Moldovan, C. A., Savin, M., Ordeanu, V., et al. (2022). The physicochemical and antimicrobial properties of silver/gold nanoparticles obtained by “green synthesis” from willow bark and their formulations as potential innovative pharmaceutical substances. Pharmaceuticals, 16(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16010048.

- Ungureanu, A. R., Ozon, E. A., Musuc, A. M., Anastasescu, M., Atkinson, I., Mitran, R. A., et al. (2024). Preparation and preliminary analysis of several nanoformulations based on plant extracts and biodegradable polymers as a possible application for chronic venous disease therapy. Polymers, 16(10), 1362. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16101362.

- Triantafillidis, J. K., Triantafyllidi, E., Sideris, M., Pittaras, T., & Papalois, A. E. (2022). Herbals and plants in the treatment of pancreatic cancer: A systematic review of experimental and clinical studies. Nutrients, 14(3), 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030619.

- Abdulrahman, A. S., Rasul, K. H., Mustafa, I. A., & Abdulqadir, S. Z. (2025). In vitro anti-cancer potentiality of quince and dandelion leaves extract against leukemia cell lines and database retrieval expression of BCR ABL and TCR genes in leukemia. Immunopathologia Persa, x(x): e41730. doi: 10.34172/ipp.2025.41730.

- Manuscript no. HELIYON-D-24-63740R1, Eco-friendly dandelion and sweet wormwood-synthesized nanoparticles: Polyphenolic drug delivery systems with antitumoral and antibacterial properties and low toxicity, in revision.

- Faivre, S., Raymond, E., Boucher, E., Douillard, J., Lim, H. Y., Kim, J. S., et al. (2009). Safety and efficacy of sunitinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: An open-label, multicentre, phase II study. The lancet oncology, 10(8), 794-800. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70171-8.

- Rini, B. I., Michaelson, M. D., Rosenberg, J. E., Bukowski, R. M., Sosman, J. A., Stadler, W. M., et al. (2008). Antitumor activity and biomarker analysis of sunitinib in patients with bevacizumab-refractory metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26(22), 3743-3748. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.15.5416.

- Zhu, A. X., Duda, D. G., Sahani, D. V., & Jain, R. K. (2009). Development of sunitinib in hepatocellular carcinoma: Rationale, early clinical experience, and correlative studies. The Cancer Journal, 15(4), 263-268. https://doi.org/10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181af5e35.

- Tolomeo, M., Grimaudo, S., Di Cristina, A., Pipitone, R. M., Dusonchet, L., Meli, M., et al. (2008). Galangin increases the cytotoxic activity of imatinib mesylate in imatinib-sensitive and imatinib-resistant Bcr-Abl expressing leukemia cells. Cancer letters, 265(2), 289-297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.025.

- Keshavarz-Pakseresht, B., Shandiz, S. A. S., & Baghbani-Arani, F. (2017). Imatinib induces up-regulation of NM23, a metastasis suppressor gene, in human Hepatocarcinoma (HepG2) Cell Line. Gastroenterology and Hepatology from Bed to Bench, 10(1), 29-33.

- Sandulovici, R. C., Gălăţanu, M. L., Cima, L. M., Panus, E., Truţă, E., Mihăilescu, C. M., et al. (2024). Phytochemical characterization, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activity of the vegetative buds from Romanian Spruce, Picea abies (L.) H. Karst. Molecules, 29(9), 2128. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29092128.

- Ghica, A., Tănase, M. L., Niculițe, C. M., Tocilă, A., Popescu, L., Luță, E. A., et al. (2024). In vitro toxicity evaluation of some plant extracts and their potential application in Xerosis cutis. Cosmetics, 11(4), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/cosmetics11040124.

- Manolache, M., Cadar, E., Antonescu, D., Mircioiu, C., Prasacu, I., & Sandulovici, R. (2018). Bioethics approach of biostatistics in clinical trials. Avoid the use of excessive or inadequate numbers of research subjects. Journal of Science and Arts, 18(1), 239-246.

- Gherghiceanu, F., Sandulovici, R., Prasacu, I., Anuta, V., & Mircioiu, C. (2016). Bioequivalence implies therapeutic equivalence. I. Biostatistical approach. Farmacia, 64(6), 823-827.

- Truţă, E., Vartic, M., & Cristea, A. N. (2011). Clinical study regarding preemptive analgesic effect of ketamine and remifentanyl in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Farmacia, 59, 2.

- Truță, E., Davitoiu, A. M., Jinescu, G., Mitu, A. M., Caragea, G., Ionica, M., & Stanciulescu, E. L. (2016). Study on the correlation of urinary leaden levels and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Rev. Chim. Bucharest, 67(4). https://doi.org/10.37358/Rev.Chim.1949.

- Sikder, M., Lead, J. R., Chandler, G. T., & Baalousha, M. (2018). A rapid approach for measuring silver nanoparticle concentration and dissolution in seawater by UV–Vis. Science of the total environment, 618, 597-607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.055.

- Ahmeda, A., Zangeneh, A., & Zangeneh, M. M. (2020). Preparation, formulation, and chemical characterization of silver nanoparticles using Melissa officinalis leaf aqueous extract for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia in vitro and in vivo conditions. Applied organometallic chemistry, 34(2), e5378. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.5378.

- Da-Cheng, H. A. O., Pei-Gen, X. I. A. O., Hong-Ying, M. A., Yong, P. E. N. G., & Chun-Nian, H. E. (2015). Mining chemodiversity from biodiversity: Pharmacophylogeny of medicinal plants of Ranunculaceae. Chinese journal of natural medicines, 13(7), 507-520. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1875-5364(15)30045-5.

- Wen-Tsai, W. (2003). A revision of Clematis sect. Clematis (Ranunculaceae). Journal of Systematics and Evolution, 41(1), 1-62.

- Hao, D. C., He, C. N., Shen, J., & Xiao, P. G. (2017). Anticancer chemodiversity of Ranunculaceae medicinal plants: Molecular mechanisms and functions. Current genomics, 18(1), 39-59. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389202917666160803151752.

| TE 30% ETOHExtract – dandelion 30% ehtanolic extract (Taraxaci extractum); |

| TE AgNPs 5% ETOH – dandelion silver nanoparticles 5% ethanolic extract; |

| SNTB + TE 30% ETOH – sunitinib + dandelion 30% ehtanolic extract; |

| IMTB + TE 30% ETOH – imatinib + dandelion 30% ehtanolic extract; |

| SNTB + TE AgNPs 5% ETOH – sunitinib + dandelion silver nanoparticles 5% ehtanolic extract; |

| IMTB + TE AgNPs 5% ETOH – imatinib + dandelion silver nanoparticles 5% ehtanolic extract. |

| ME 30% ETOHExtract – lemon balm 30% ehtanolic extract (Melissae extractum); |

| ME AgNPs 3% ETOH – lemon balm silver nanoparticles 3% ethanolic extract; |

| SNTB + ME 30% ETOH – sunitinib + lemon balm 30% ehtanolic extract; |

| IMTB + ME 30% ETOH – imatinib + lemon balm 30% ehtanolic extract; |

| SNTB + ME AgNPs 3% ETOH – sunitinib + lemon balm silver nanoparticles 3% ehtanolic extract; |

| IMTB + ME AgNPs 3% ETOH – imatinib + lemon balm silver nanoparticles 3% ehtanolic extract. |

| CVE Extract – traveller’s joy aqueous extract (Clematis vitalbae extractum); |

| CVE AgNPs – Clematis vitalbae extractum silver nanoparticles; |

| SNTB + CVE AgNPs – sunitinib + Clematis vitalbae extractum silver nanoparticles; |

| IMTB + CVE AgNPs – imatinib + Clematis vitalbae extractum silver nanoparticles. |

| SNTB – sunitinib (synthetic anticancer drug); |

| IMTB – imatinib (synthetic anticancer drug). |

| Sample | Nanoparticle diameter (nm) | ||

| Min – Max | FWHM | Mean ± SD | |

| CVE AgNPs | 6-18 | 9-13 | 11.1 ± 1.9 |

| ME AgNPs | 9-22 | 11-17 | 14.5 ± 2.9 |

| (I) HepG2_Treatment_ME_vs_SNTB | (J) Control_Group |

Mean Difference (J-I) |

Std. Error |

Sig. (p value) |

| ME AgNPs 1:1 | Control_SNTB | 0.61259* | 0.08632 | 0.003 |

| ME AgNPs 1:2 | Control_SNTB | 0.39760* | 0.07941 | 0.022 |

| SNTB + ME AgNPs 1:1 | Control_SNTB | 0.49988* | 0.07853 | 0.002 |

| (I) HepG2_Treatment_ME_vs_IMTB | (J) Control_Group |

Mean Difference (J-I) |

Std. Error |

Sig. (p value) |

| ME AgNPs 1:1 | Control_IMTB | 0.45994* | 0.10684 | 0.028 |

| IMTB + ME AgNPs 1:1 | Control_IMTB | 0.37692* | 0.07202 | 0.036 |

| (I) HepG2_Treatment_CVE_vs_SNTB | (J) Control_Group |

Mean Difference (J-I) |

Std. Error |

Sig. (p value) |

| CVE 1:1 | Control_SNTB | 0.51588* | 0.07305 | 0.004 |

| CVE 1:2 | Control_SNTB | 0.46707* | 0.06980 | 0.010 |

| CVE 1:4 | Control_SNTB | 0.40876* | 0.09289 | 0.035 |

| CVE AgNPs 1:1 | Control_SNTB | 0.68835* | 0.06493 | 0.005 |

| CVE AgNPs 1:2 | Control_SNTB | 0.50431* | 0.08197 | 0.005 |

| SNTB + CVE AgNPs 1:1 | Control_SNTB | 0.37086* | 0.04998 | 0.000 |

| SNTB + CVE AgNPs 1:2 | Control_SNTB | 0.26627* | 0.05312 | 0.018 |

| (I) HepG2_Treatment_CVE_vs_IMTB | (J) Control_Group |

Mean Difference (J-I) |

Std. Error |

Sig. (p value) |

|

| CVE 1:1 | Control_IMTB | 0.43148* | 0.08789 | 0.023 | |

| CVE 1:2 | Control_IMTB | 0.37713† | 0.08879 | 0.066 | |

| CVE AgNPs 1:1 | Control_IMTB | 0.62611* | 0.06099 | 0.011 | |

| CVE AgNPs 1:2 | Control_IMTB | 0.42165* | 0.09653 | 0.028 | |

| IMTB + CVE AgNPs 1:1 | Control_IMTB | 0.40090* | 0.05021 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).