1. Introduction

A malignant tumor called breast cancer arises from faulty cells in the breast tissue. It is among the most prevalent malignancies in women, and if treatment is delayed, it may spread to other body areas. With 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 fatalities in 2020, it is the most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide [

1]. Despite their effectiveness, traditional treatments like radiation and chemotherapy frequently have serious side effects and deal with problems like drug resistance [

2]. Alternative remedies have become more popular as a result. The Middle Eastern and South Asian medicinal plant

Rhazya stricta (

R. stricta) which contains bioactive alkaloids [

3], flavonoids, and glycosides [

4,

5], has long been used to cure a variety of illnesses, including cancer [

6].

Nanotechnology has emerged as an effective tool in cancer diagnosis and treatment due to its ability to control matter at both the molecular and atomic levels [

7]. Among its many potential uses, the use of nanoparticles (NPs) for targeted delivery of drugs and imaging has received significant interest. Nanoparticles, with their high surface-area-to-volume ratio, adjustable size, and surface chemistry, interact with biological systems more effectively, allowing for increased permeability and retention in tumor tissues [

8]. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), in particular, have strong cytotoxic characteristics and have shown substantial potential in oncological applications [

9].

The anticancer mechanisms of biosynthesized AgNPs involve multiple cellular pathways. Various in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that AgNPs can suppress cancer cell proliferation and viability. They exert their anticancer effects by disrupting cellular ultrastructure, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), inducing DNA damage, and ultimately triggering apoptosis and necrosis [

10,

11]. These NPs induce oxidative stress through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), disrupt mitochondrial membrane potential, activate caspase-mediated apoptosis, and interfere with signaling cascades such as PI3K/Akt and MAPK [

12,

13].

The purpose of this study is to produce AgNPs from

R. stricta leaf extract using a green, cost-effective approach to investigate their anticancer efficacy against MCF-7 cells. By combining the therapeutic characteristics of plant-based phytochemicals with the cytotoxic potential of silver, this study aims to contribute to the creation of environmentally friendly nanomaterials for cancer treatment. AgNPs are formed through green synthesis by converting Ag⁺ ions into metallic Ag⁰ using phytochemicals containing functional groups like hydroxyl and carbonyl. These naturally occurring molecules not only facilitate the initial reduction and nucleation steps, but they also act as capping agents, directing the formation of nanoparticles while preventing them from aggregating. This dual functionality ensures the shape and stability of the produced AgNPs [

14]. The current work emphasizes the importance of using plant extracts as an environmentally friendly substitute to harmful chemical reagents, representing a critical step toward greener nanotechnology solutions. This work advances both nanotechnology and the possibility of using botanical extracts as sustainable and eco-friendly substitutes for conventional chemicals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Plant Extract

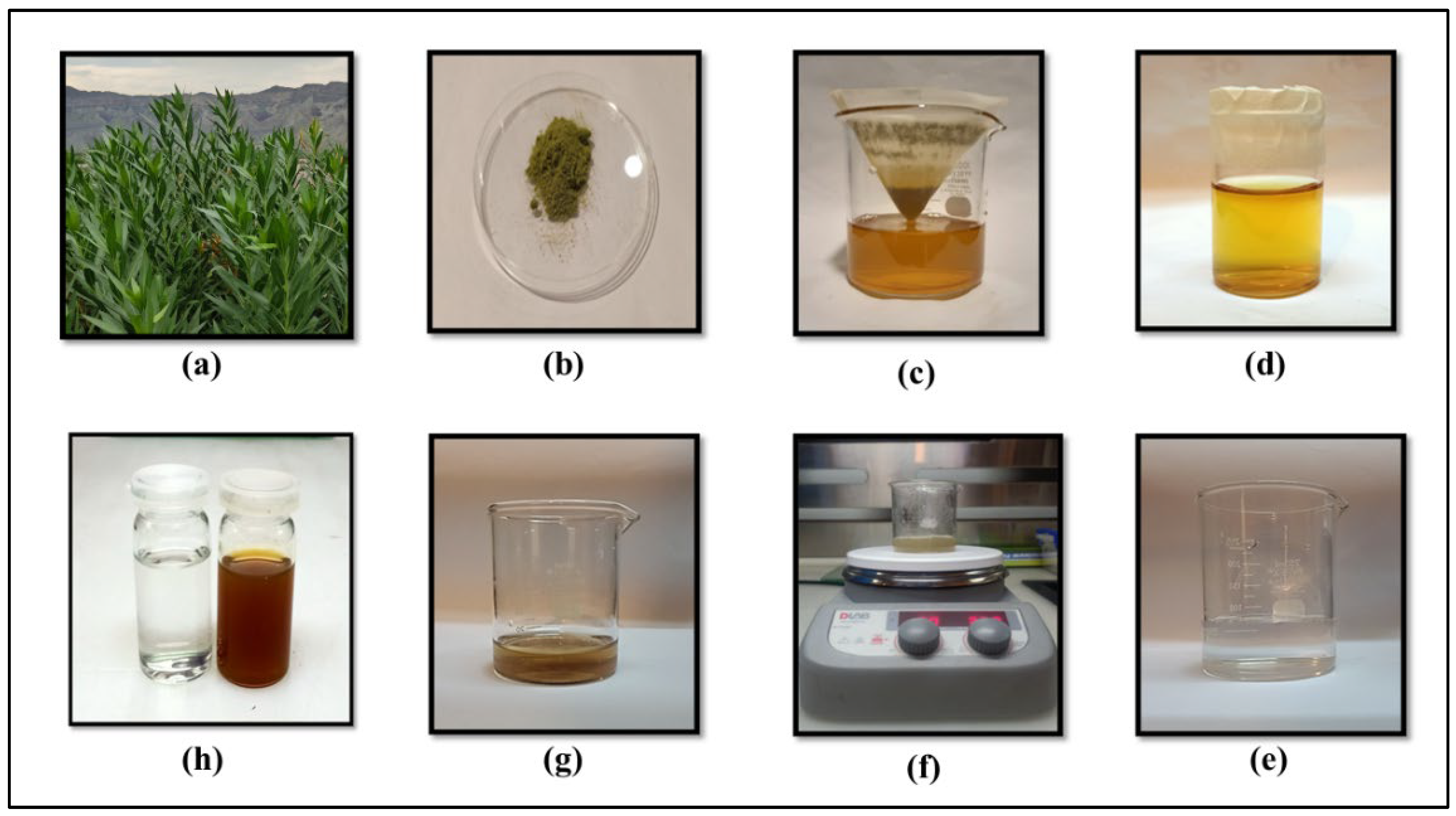

Fresh leaves of R. stricta were collected from Dera Ismail Khan, Pakistan, thoroughly rinsed with tap and distilled water, then air-dried for a week. The dried leaves were finely ground into powder. Two grams (2 g) of the powdered material were precisely measured and then mixed with 100 mL of distilled water in a glass beaker. The solution was heated on a hot plate at 60°C while being continuously stirred for a duration of 1 hour. Once the solution turned yellow, it was filtered and subsequently centrifuged for 20 minutes. Resulting aqueous extract was stored in glass bottles at 4°C.

2.2. Green Synthesis of AgNPs

A 20 mL solution containing 1 mM silver nitrate precursor was heated to 80 °C on a hot plate with constant magnetic stirring at 200 rpm covered with an aluminum foil to avoid evaporation. When the temperature was achieved up to 80°C, aqueous extract (0.2 mL) from R. stricta leaves was added dropwise into the silver nitrate solution (1 mM). The solution became very light foggy right after the addition of extract. To raise the pH to 8, a few drops of 0.1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were introduced into the solution. The mixture was then stirred continuously and heated to 80°C for 45 minutes. Upon completion of the reaction, indicated by a color change to dark brown, the solution was allowed to cool to room temperature for 10 minutes as shown in Figure (1). Different concentrations of aqueous extract were used, such as 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.9 and 1 mL respectively and selected 0.2 mL concentration for further studies.

Figure 1.

a) R. stricta plant, (b) Dried leaves powder, (c) Filtration of aqueous extract through Whatman chromatographic paper no.1, (d) R. stricta leaves extract (e) AgNO3 solution (f) Heating and stirring at 80 °C (g) prepared nps (h) left-AgNO3, right-AgNPs.

Figure 1.

a) R. stricta plant, (b) Dried leaves powder, (c) Filtration of aqueous extract through Whatman chromatographic paper no.1, (d) R. stricta leaves extract (e) AgNO3 solution (f) Heating and stirring at 80 °C (g) prepared nps (h) left-AgNO3, right-AgNPs.

2.3. Biological Assay

2.3.1. Cell Culture

MCF-7 breast cancer cells were employed for the cell assays. Typically, the cells were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin, under standard cell culture conditions (37°C; 5% CO2).

2.3.2. MTT Cell Viability Assay

The minimum inhibitory concentration was used for R. stricta leaves extract and R. stricta leaves mediated Ag NPs against MCF-7 cell lines. This assay was performed in MMG lab, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan. The MTT assay was conducted by first maintaining and preparing the cell culture to ensure the logarithmic growth phase and the required confluency. Following this, cells were plated into 96-well plates and cultured for 24 hours at 37°C, or until they reached 70% confluency. 200 µL of a variety of working dilutions of R. stricta leaf extract and R. stricta AgNPs were made in DMEM and added to each plate. 200 µL of culture medium were added to the control cells. Following a 72-hour incubation period, cells were rinsed and subjected to a 3-hour incubation period with 100 µL of 10% MTT reagent to facilitate formazan reduction. Following that, 150 µL of DMSO each well was combined with formazan crystals. After that, a microplate reader was used to detect each well's absorbance at 570 nm in order to perform a spectrophotometric analysis and determine the intensity. The absorbance of the samples was used to calculate the percentage of viable cells.

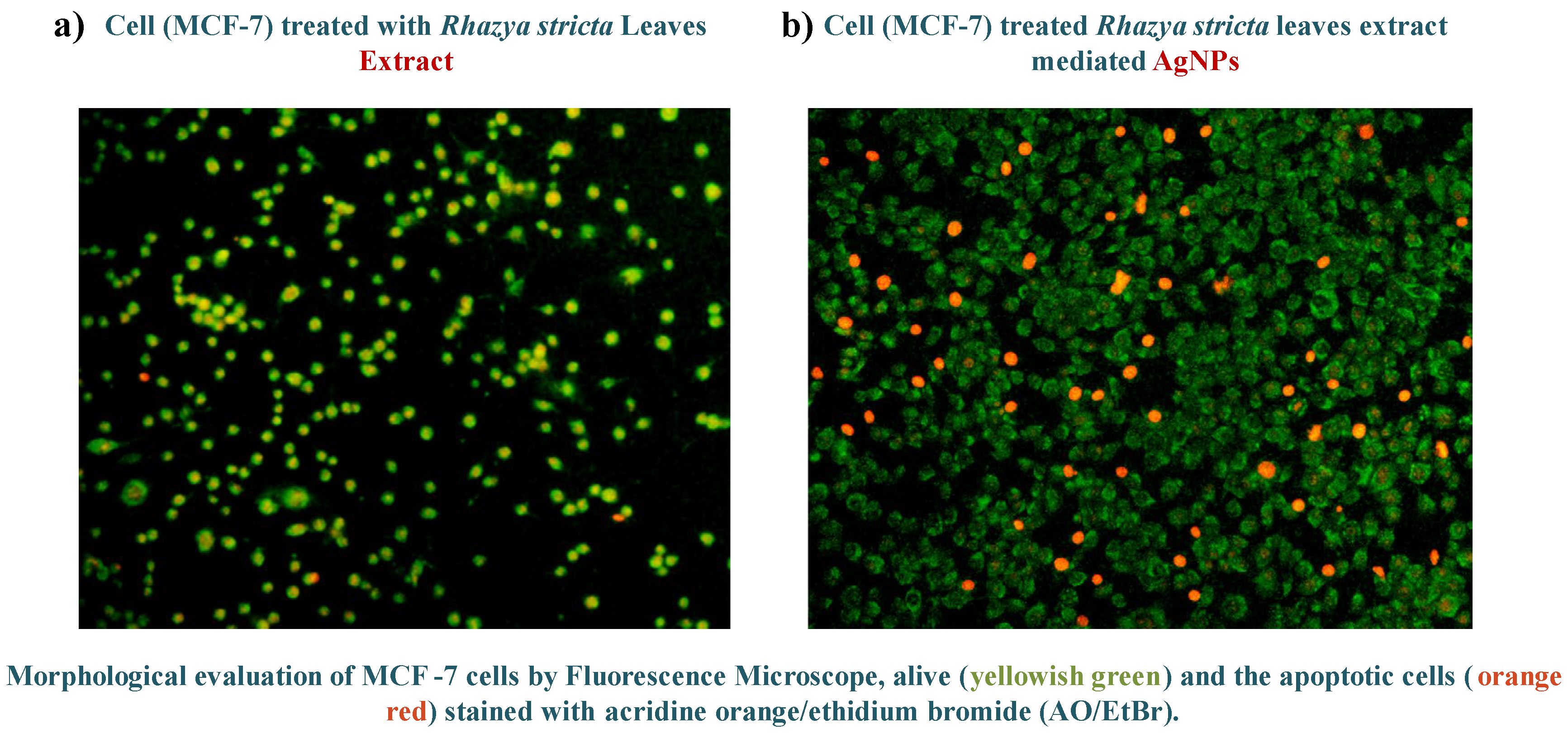

2.3.3. Cell Death Analysis

Fluorescent dyes such as ethidium bromide (EtBr) and acridine orange (AO) are often used to detect cell death. Researchers can distinguish between live, apoptotic, and necrotic cells using changes in uptake and staining properties. [

15]. Concisely, 4000 MCF-7 cells were planted in a 12-well culture plate at 70% confluency, and after 72 hours, the cells were exposed to LC

50 concentrations (doses) of

R. stricta-Extract and

R. stricta-AgNPs. Following the removal of the medium, cells were twice washed with 1 X PBS. AO and EtBr (1 mg/mL) stock solution was made in 1X PBS. Each well was filled with the working staining mixture of AO/EtBr in a 5:3 ratio, which was then added, and the plate was left in the dark for roughly 15 to 30 minutes. A 10X (Scale: 100 m) Olympus inverted fluorescence microscope was used to take the pictures.

2.4. Instrumentation

In this study, the structural and optical properties of AgNPs were systematically examined through a comprehensive analysis. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), a distinguishing feature of metallic NPs, was examined, resulting in a unique absorption spectrum in the UV and visible range. The SPR peak was spotted with a UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800). AgNPs were produced under various reaction conditions, and their elemental composition was evaluated by energy dispersive X-Ray (EDX) analysis. EDX, a surface analysis technique, used a high kinetic energy electron beam to characterize the elements on the sample's surface. The surface morphology, shape, and size distribution of the produced AgNPs were investigated using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) at 140,000x magnification under high- vacuum conditions. These three characterizations, SPR analysis, EDX analysis, and SEM analysis, together provide useful information about the structural and optical properties of the tailored AgNPs.

3. Results

3.1. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

This technique was used to examine the structural and optical properties of AgNPs. Metallic NPs have a distinctive property which is called Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). Due to SPR, metallic NPs have a distinctive absorption spectrum that is in the UV and Visible range. SPR occurred as a result of the steady-state oscillations between conduction electrons caused by the light absorption by metallic NPs. When an incident beam of a certain frequency strikes the sample, some portion of the light is transmitted through the sample while some gets absorbed. The absorbance peak of the produced NPs may be estimated by measuring the fraction of the incident beam that is absorbed. AgNPs were synthesized by varying reaction conditions described as follows:

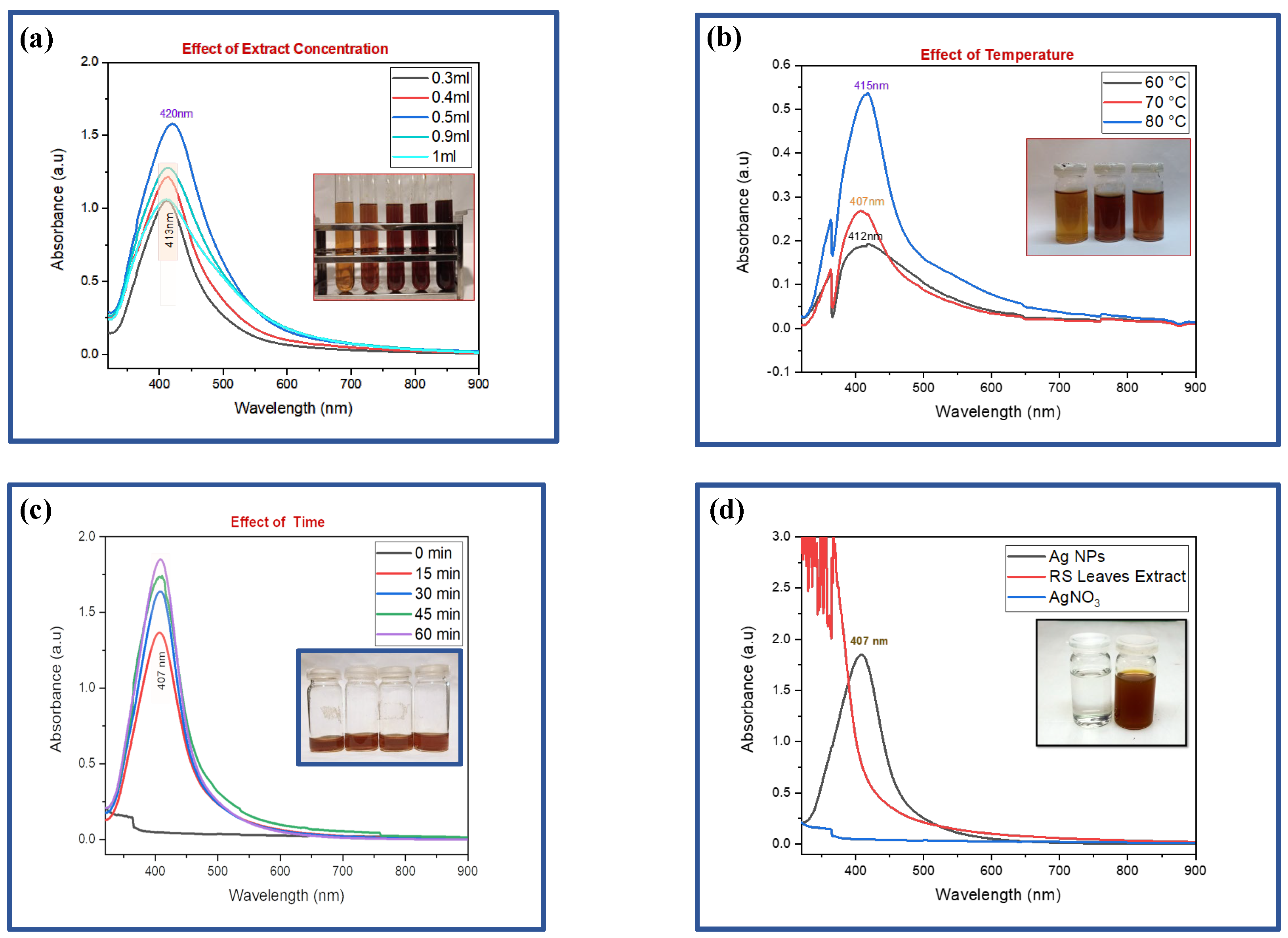

3.1.1. Effect of Extract Concentration

AgNPs were successfully synthesized using various volumes (0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.9, and 1 mL) of

R. stricta leaves extract. UV-visible spectroscopy demonstrated a strong hyperchromic impact, most pronounced at a 0.5 mL extract concentration [

Figure 2(a)]. This effect was accompanied by a redshift, which indicated a shift in the peak site to longer wavelengths or lower energy levels. This shift in peak position indicates alterations in the size, shape, or chemical conditions of the AgNPs, which can have a significant impact on their optical and chemical characteristics, making the 0.5 mL extract concentration an especially interesting condition for further research and applications in nanotechnology.

Figure 2.

:(a)-UV-Visible analysis at different extract concentrations [0.3 ml to 1 ml (left to right)]. (b)-UV-visible analysis of varying reaction temperature, on the absorption peaks on AgNPs [Temp. 60, 70 & 80 (left to right)]. (c)-UV-Visible analysis of varying reaction time, on the absorption peaks on AgNPs [15, 30, 45 and 60 minutes (from left to right)]. (d)-SPR peak of optimized AgNPs, AgNO3, and leaf extract [AgNO3 & AgNPs (left to right)].

Figure 2.

:(a)-UV-Visible analysis at different extract concentrations [0.3 ml to 1 ml (left to right)]. (b)-UV-visible analysis of varying reaction temperature, on the absorption peaks on AgNPs [Temp. 60, 70 & 80 (left to right)]. (c)-UV-Visible analysis of varying reaction time, on the absorption peaks on AgNPs [15, 30, 45 and 60 minutes (from left to right)]. (d)-SPR peak of optimized AgNPs, AgNO3, and leaf extract [AgNO3 & AgNPs (left to right)].

3.1.2. Effect of Temperature

At a constant extract concentration of 0.2 mL, the effect of different temperatures (60°C, 70°C, and 80°C) on AgNP synthesis was studied. UV-visible spectroscopy examination demonstrated a significant improvement in the reduction process, accompanied by a hyperchromic effect as the temperature increased. The most beneficial result was obtained at 80°C, as evidenced by the presence of an evident peak in

Figure 2(b). This temperature-dependent improvement in the reduction process, as well as the hyperchromic effect, suggest that higher temperatures play an important role in optimizing AgNP synthesis, with 80°C being the preferred temperature to achieve the most efficient and effective NP synthesis under these experimental conditions.

3.1.3. Effect of Time

At a constant temperature of 80°C and a fixed extract concentration of 0.2 mL, the synthesis of AgNPs was examined while varying the reaction time over intervals of 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60 minutes

Figure 2(c). UV-visible spectroscopy analysis exhibited a compelling hyperchromic effect with increasing reaction time. This observation underscores the time-dependent evolution of the AgNPs synthesis process, emphasizing the significance of monitoring and adjusting the reaction duration to attain the desired optical and chemical properties of the nanoparticles, further highlighting the dynamic nature of the synthesis process in achieving optimal results.

The optimized AgNPs synthesized using

R. stricta extract displayed a distinct single SPR peak at 407 nm as shown in

Figure 2(d), indicative of their unique optical properties. In stark contrast, AgNO

3, the precursor compound, exhibited no significant absorption within the same wavelength range. To analyze the synthesized AgNPs comprehensively, a UV-visible spectroscopy study was conducted, scanning wavelengths from 300 to 800 nm. The resulting graphical representation depicted the relationship between wavelength (nm) on the x-axis and absorbance (in arbitrary units, a.u.) on the y-axis, with the prominent SPR peak at 407 nm serving as clear signature of the successful synthesis of AgNPs using

R. stricta leaves extract.

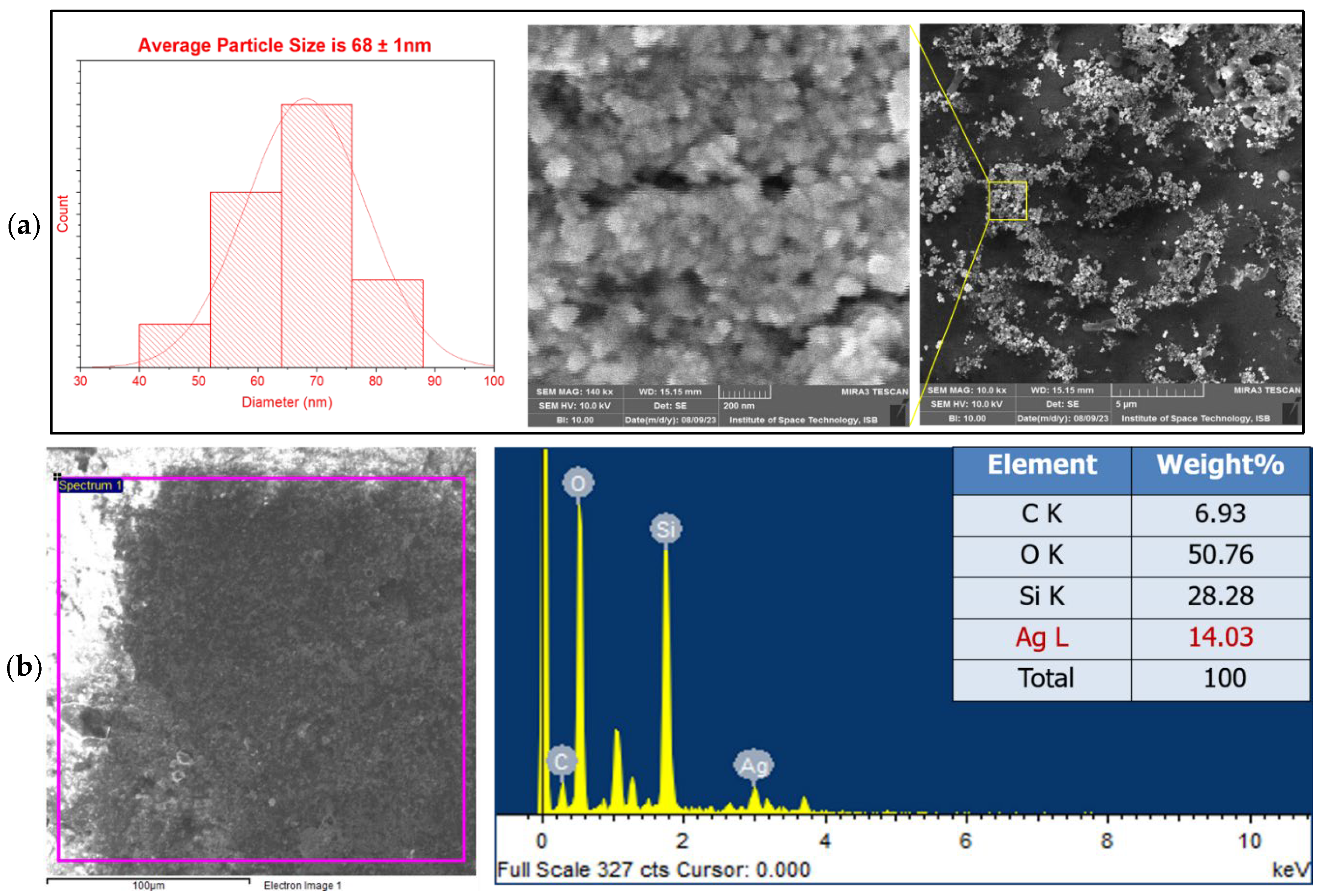

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

SEM analysis is employed for the analysis of surface morphology, shape, and size distribution of NPs. To govern the morphology of synthesized AgNPs, SEM analysis was done in a high vacuum at 140,000x magnification. SEM images revealed that

R. stricta mediated AgNPs had a spherical morphology having an average particle size of 68±1 nm as shown in the

Figure 3(a). Clusters of particles shown in the image indicate the aggregation of AgNPs.

Figure 3.

a)- SEM images of R. stricta-mediated AgNPs. (b)- EDX analysis of R. stricta mediated AgNPs.

Figure 3.

a)- SEM images of R. stricta-mediated AgNPs. (b)- EDX analysis of R. stricta mediated AgNPs.

3.3. Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis

Using EDX analysis, the elemental makeup of the material was ascertained. This type of surface analysis is applied when a sample's surface is struck by a high-kinetic-energy electron beam. An electron is released from the element's inner shell and a hole is made in the inner shell when the incident light strikes the sample's surface. This hole is then filled by the upper-level electron by releasing some of its energy in the form of X-rays. The amount of energy released during this step is specific for each element. Then these emitted X-rays are counted, and their energies are calculated using an energy dispersive spectrogram. In the EDX graph, energy in keV on the x-axis is plotted against several counts along the y-axis as shown in the

Figure 3. The EDX analysis of

R. stricta mediated AgNPs which was observed in

Figure 3(b) showed a peak at 3 keV which indicates the presence of AgNPs. Other elements such as carbon (C) and oxygen (O) were observed due to phytochemicals present in our sample. O may also be observed due to moisture or due to air as well. Silicon (Si) peak appeared because we placed our sample over the glass substrate.

3.4. Anticancer Results

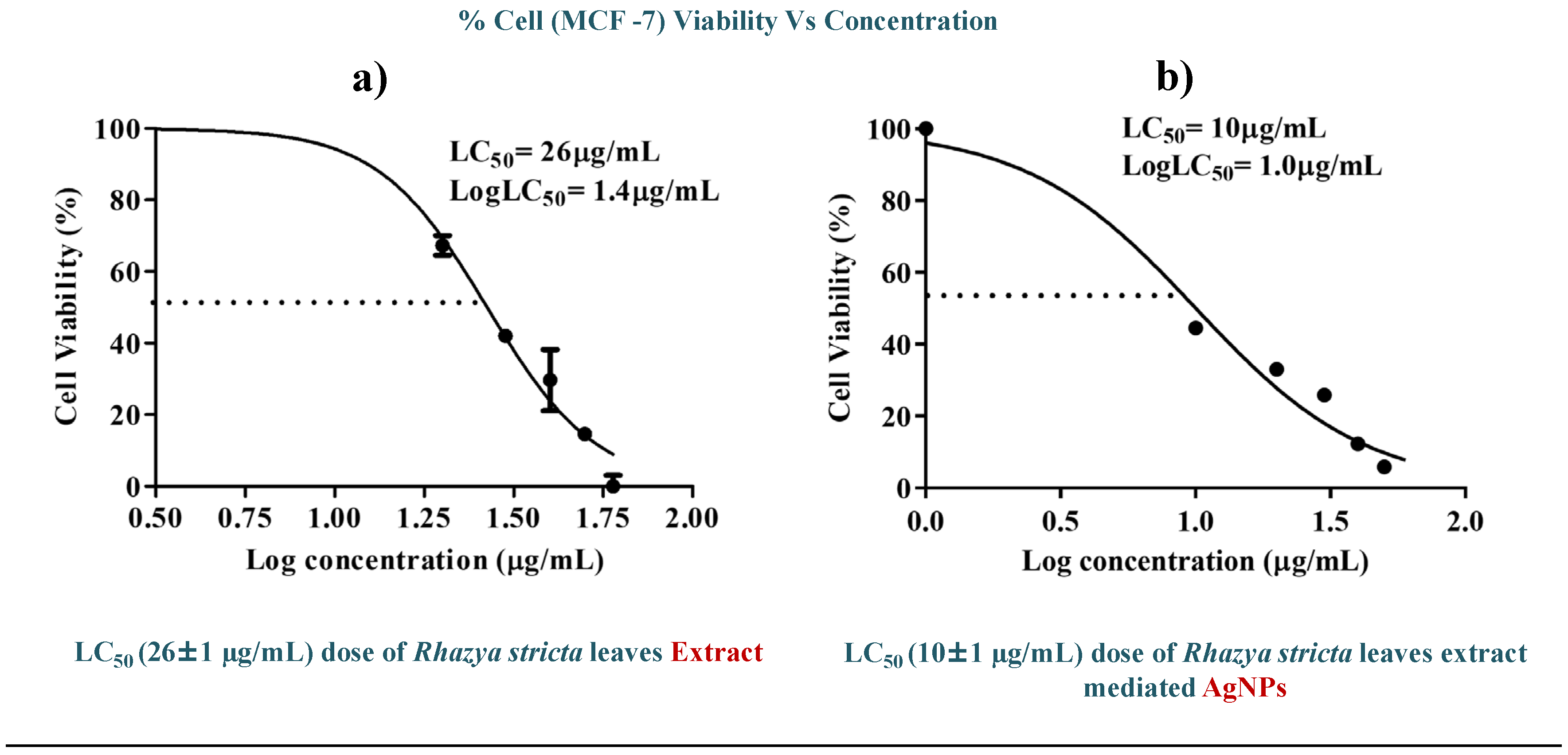

3.4.1. Cell Viability

By using the MTT assay method, the in vitro cytotoxic effect of

R. stricta leaf-mediated AgNPs against MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines was evaluated. Different concentrations of

R. stricta-Leaf extract and AgNPs were used to treat cancer cells. Following treatments with various doses of

R. stricta-Extract at and AgNPs, the viability of the cells was evaluated. The MTT experiment findings showed that when the concentrations of synthesized AgNPs increased, the cell viability reduced. LC

50 was discovered to be 26±1 µg/mL and 10±1 µg/mL for

R. stricta-leaf extract and

R. stricta-AgNPs respectively as shown in

Figure 4. It shows that AgNPs synthesized from

R. stricta-leaves extract have a greater propensity to eradicate cancer cells as compared to the extract only and can be used as an anticancer drug for breast cancer.

Figure 4.

In vitro cytotoxic activity of (a) R.stricta leaves extract and (b) R.stricta mediated AgNPs against MCF-7 cell lines.

Figure 4.

In vitro cytotoxic activity of (a) R.stricta leaves extract and (b) R.stricta mediated AgNPs against MCF-7 cell lines.

3.4.2. Cell Death Analysis

Fluorescent dyes ethidium bromide (EtBr) and acridine orange (AO) were used as a way to measure cell death. This method makes it possible to distinguish between live, apoptotic, and necrotic cells by exploiting of differences in cellular uptake and staining patterns.

Results shown in

Figure 5: Green Florescence= Live Cells, Yellowish Green Florescence=Apoptotic Cells, and Red Florescence= Necrotic Cells or Dead Cells

Figure 5.

Cell death analysis of (a) R.stricta extract and (b) R.stricta mediated AgNPs.

Figure 5.

Cell death analysis of (a) R.stricta extract and (b) R.stricta mediated AgNPs.

Figure 5: (a) and (b) depicts the cell death induced by LC

50 doses of

R. stricta-Extract and

R. stricta-AgNPs respectively. Green spots indicate the live cells while the red ones are completely dead cells. This cell death was necrotic as induced suddenly by abrupt rupturing of the cell membrane. While the yellowish-green fluorescence showed the apoptotic cells in which programmed cell death has been induced [

16].

The cell death analysis states that a large number of cell deaths occurred when cells were exposed to R. stricta-AgNPs as compared to the exposure to extract only.

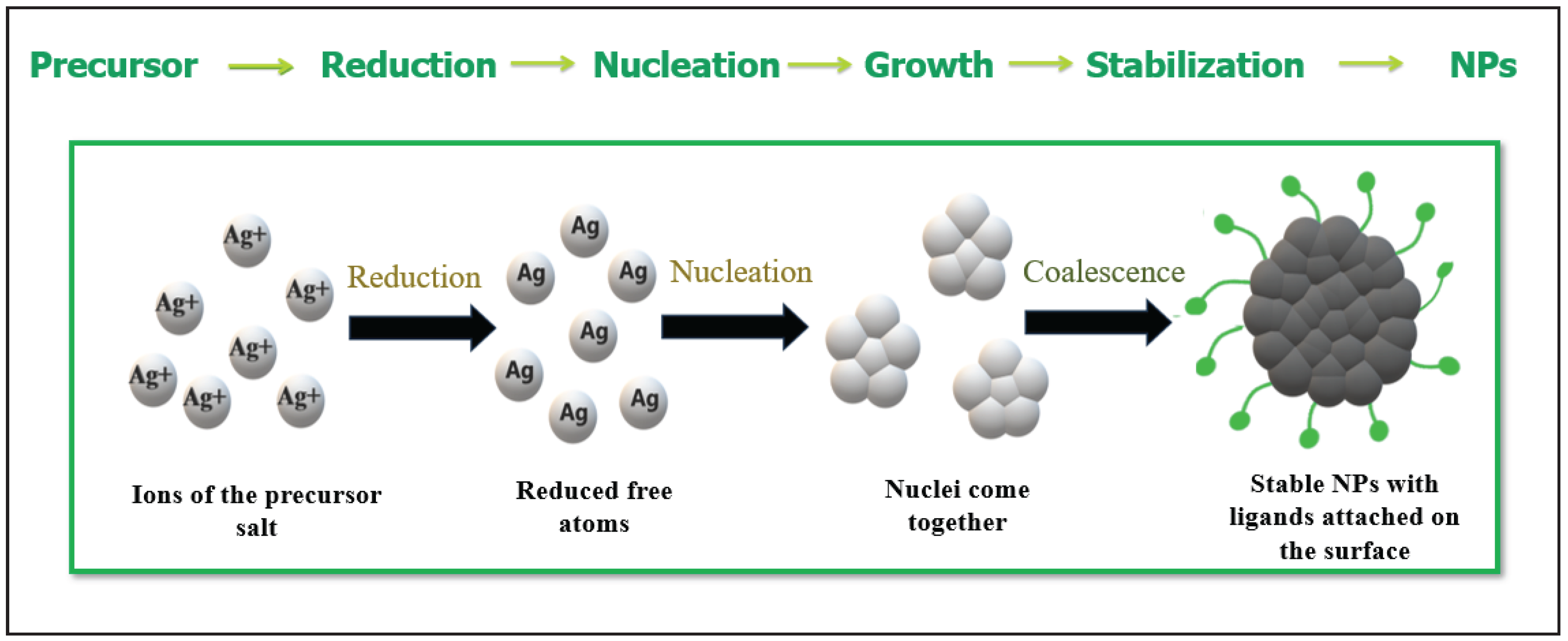

4. Discussion

AgNPs are widely recognized for their biomedical potential, which can be further improved by surface modification using various medicinal and natural biomolecules [

17]. Despite their promising applications, concerns regarding nanoparticle-induced toxicity have limited their use [

18]. Biosynthesizing AgNPs with plant extracts provides a safer option since bioactive ingredients not only mediate redox reactions but also serve as natural stabilizing and capping agents [

19,

20]. This plant extract contains a wide range of phytochemicals, including alkaloid, saponins, tannins, phenols, amino acids, triterpenes, and polysaccharides, which were detected via phytochemical analysis [

3]. The general proposed mechanism for the green synthesis of nanoparticles is illustrated in

Figure 6. Where, silver ions (Ag

+) are reduced by phytochemicals present in plan extract. The green synthesis of silver nanoparticles involves the reduction of Ag⁺ by phytochemicals present in plant extracts. These phytochemicals, such as flavonoids, phenolics, terpenoids, and alkaloids, contain electron-rich functional groups like hydroxyl (–OH) and carbonyl (=O), which donate electrons to Ag⁺, reducing it to metallic silver (Ag⁰). This reduction initiates the nucleation process, where individual silver atoms come together to form small clusters. As the process continues, these nuclei grow into NPs. Simultaneously, the same phytochemicals act as capping agents, stabilizing the NPs and preventing their aggregation, which results in the controlled synthesis of AgNPs with desired size and shape [

14]. This reduction is attributed to the electron rich groups such as OH and =O etc., and then nuclei come together to form NPs.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of reduction of silver ions (Ag+) into silver nanoparticles (Ag0) mediated by plant extract.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of reduction of silver ions (Ag+) into silver nanoparticles (Ag0) mediated by plant extract.

This comprehensive study effectively synthesized AgNPs utilizing

R. stricta-leaf extract and investigated their characteristics and uses. The initial observation of the solution hue shift served as a visual cue for the creation of synthetic AgNPs. This process, attributable to the SPR effect, turned the colloidal solution a dark brown color, indicating the reduction of Ag ions to Ag atoms [

21]. The brown coloration observed is attributed to the SPR effect [

22,

23], where resonance frequencies of surface oscillating electrons align with incident light frequencies, causing light absorption and resulting in the SPR peak. UV-visible spectroscopy analysis confirmed this SPR peak at 407 nm, substantiating Ag NP formation [

24,

25,

26,

27]. These NPs have the potential to interact with biomolecules in novel ways on the surface and within body cells, this may revolutionize cancer therapy and diagnosis [

28,

29]. SEM analysis at 200kx magnification revealed spherical NPs with an approximate size of 68±1 nm, ideally suited for diverse applications, including biomedical contexts. Further confirmation of Ag NP formation was derived from EDX analysis of

R. stricta-leaves extract, which exhibited an energy peak at 3 keV corresponding to Ag. The anticancer potential of the synthesized AgNPs was rigorously evaluated through MTT assay, comparing their efficacy with the leaf extract alone. Remarkably, AgNPs demonstrated potent anticancer effects, evident from their low LC

50 values, suggesting their potential as promising anticancer agents. The enhanced anticancer activity of AgNPs compared to the leaf extract alone can be attributed to their unique physicochemical properties, including small size and high surface area, facilitating efficient cellular interactions and uptake.

To explore further into their anticancer mechanism, the interactions of AgNPs with cancer cells were investigated. AgNPs induced apoptosis, inhibit cell proliferation, create reactive oxygen species (ROS), alter mitochondrial function, and disrupt the cell signaling pathways [

30]. Furthermore, AgNPs have the potential to preferentially target cancer cells because to their enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) properties. AgNPs can cause oxidative stress and mitochondrial malfunction in tumor cells, resulting in DNA fragmentation, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis. This focused cytotoxicity is especially important in the case of breast cancer, which remains one of the most common cancers affecting women globally. Breast cancer is characterized by an uncontrolled growth of epithelial cells in the mammary glands and is a primary cause of cancer-related death. Despite substantial advances in diagnoses and therapies, the disease continues to be a major medical and socioeconomic burden worldwide. The exploration of nanomaterials like AgNPs for enhanced cancer therapy is thus of paramount importance [

31,

32,

33,

34]. The MTT experiment yielded compelling findings: increasing AgNPs concentration correlated with reduced cell viability, with an LC

50 of 10±1 µg/mL for

R. stricta-AgNPs, surpassing

R. stricta-Extract (26±1 µg/mL) in terms of cell death (Table.1).

Table 1.

Anticancer effect of R. stricta extract and R.stricta mediated AgNPs.

Table 1.

Anticancer effect of R. stricta extract and R.stricta mediated AgNPs.

| Sr.# |

Sample |

Solvent |

LC50 values |

| 1 |

R.stricta Leaves Extract |

DI Water |

26±1 µg/mL |

| 2 |

R. stricta-AgNPs |

DI Water |

10±1 µg/mL |

5. Conclusion

In this study, we successfully synthesized AgNPs using Rhazya stricta-leaf extract and characterized their properties. This method has no harmful effects on the environment as compared to chemical approaches as it does not produce toxic chemicals. The spherical structure of AgNPs having an average size of 68±1 nm calculated by SEM images. EDX analysis also confirmed the formation of AgNPs by giving an observable peak at 3 keV. In vitro, findings suggest that AgNPs have potential applications as a potent anticancer agent, with promising results in MTT assays. In conclusion, we have proved that R. stricta-leaves mediated AgNPs can kill cancer cell lines, and the LC50 values are proven to be 10±1 µg/mL against breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7). Further research into the specific mechanisms of Ag NP-induced cytotoxicity and in vivo studies are warranted to better understand their potential for cancer therapy. This research contributes to the growing body of knowledge on green synthesis methods for NPs and their biomedical applications.

Author’s Contribution

Mahnoor Nasir performed the experiments and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. Muhammad Akram Raza supervised the project, contributed to the data analysis, and revised the manuscript analytically, Zakia Kanwal conceived the study, developed the methodology. Saira Riaz and Shahzad Naseem provided the materials and resources for the study, and conducted characterizations, Muti-ur-Rehman participated in execution of experiments, and analysis of the study. Mehmoona Zahid contributed to the interpretation of the results and critical feedback on the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable

Human and animal rights

No humans or animals were used in this study. All experimental protocols complied with institutional guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Availabilty of data

This article contains all of the data collected or analyzed during the course of this investigation. The corresponding author may provide more data upon request.

Funding

This study received no grants from any funding source in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Asima Tayyeb of the School of Biological Sciences, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan, for providing laboratory facilities and technical assistance during this project. Special appreciations are also made to Shafqat Rasool and Hira Ghani for their valuable help during the laboratory work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest financial or otherwise.

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R. L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2021, 71 (3), 209–249.

- Gottesman, M. M. Mechanisms of Cancer Drug Resistance. Annual Review of Medicine 2002, 53, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albeshri, A.; Baeshen, N. A.; Bouback, T. A.; Aljaddawi, A. A. A Review of Rhazya stricta Decne Phytochemistry, Bioactivities, Pharmacological Activities, Toxicity, and Folkloric Medicinal Uses. Plants 2021, 10(11), 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M. E. M.; Sobahi, T. R.; Albrakati, A.; Alfayez, A.; Abdel-Lateff, A.; Khan, S. A. Alkaloids from Rhazya stricta and Their Cytotoxic Potential. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2018, 214, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, T.; Khan, M.; Ullah, S.; Nazir, A.; Shahid, M.; Ahmed, S.; Qureshi, R. Phytochemical Profile and Pharmacological Properties of Rhazya stricta: A Review. Phytotherapy Research 2023, 37(1), 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zia-Ul-Haq, M.; Ahmad, S.; Calani, L.; Deriu, M.; Maiani, G.; Del Rio, D. Medicinal Properties of Rhazya stricta and Its Chemical Constituents. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2013, 2013, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, K. K. The Handbook of Nanomedicine; Springer: New York, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, R.; Mukherjee, P. Biological Properties of “Naked” Metal Nanoparticles. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2008, 60(11), 1289–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamer, U.; Cetin, D.; Suludere, Z.; Boyaci, I. H.; Temiz, H. T.; Yegenoglu, H.; Elerman, Y. Gold-Coated Iron Composite Nanospheres Targeted the Detection of Escherichia coli. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2013, 14(3), 6223–6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, M. M.; Snyder, C. M.; Sloop, J.; Solst, S. R.; Donati, G. L.; Spitz, D. R.; Singh, R. The Mechanism of Cell Death Induced by Silver Nanoparticles Is Distinct from Silver Cations. Particle and Fibre Toxicology 2021, 18, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, M. ; Ab. Rahim, N.; Wan Omar, W. A.; Nik Mohamed Kamal, N. N. S. Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles in A549 and BEAS-2B Cell Lines. Bioinorganic Chemistry and Applications 2022, 2022, 8546079. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, E.-J.; Seo, J.-H.; Choi, I.; Shin, Y.-S.; Kwon, S.-M.; Choi, J.-W. Mitochondria Mediated Apoptosis of Silver Nanoparticles in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. Toxicology in Vitro 2015, 29(8), 1493–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Arif, M.; Iqbal, J.; Ali, S. F.; Shah, B.; Khan, A.; Halin, I.; Khan, M. R. Molecular Mechanisms of Silver Nanoparticles in Breast Cancer: A Review. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 2021, 122(3), 239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Iravani, S.; Korbekandi, H.; Mirmohammadi, S. V.; Zolfaghari, B. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: Chemical, Physical and Biological Methods. Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences 2014, 9(6), 385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Liu, P. C.; Liu, R.; Wu, X. Dual AO/EB Staining to Detect Apoptosis in Osteosarcoma Cells: Comparison with Flow Cytometry. Medical Science Monitor Basic Research 2015, 21, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R.; Saraswathy, M. Pro Apoptotic and Cytotoxic Effects of Enriched Fraction of Elytranthe longa on HepG2 Cells. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2016, 16, 1395. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran, A.; Chandran, P.; Khan, S. S. Biofunctionalized Silver Nanoparticles: Advances and Prospects. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2013, 105, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwal, Z.; Raza, M. A.; Manzoor, F.; Riaz, S.; Jabeen, G.; Fatima, S.; Naseem, S. A Comparative Assessment of Nanotoxicity Induced by Metal (Silver, Nickel) and Metal Oxide (Cobalt, Chromium) Nanoparticles in Labeo rohita. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botcha, S.; Prattipati, S. D. Callus Extract Mediated Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles, Their Characterization and Cytotoxicity Evaluation Against MDA-MB-231 and PC-3 Cells. BioNanoScience 2019, 10, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.; Tayyeb, A.; Raza, M. A.; Ashfaq, H.; Perveen, S.; Kanwal, Z.; Riaz, S.; Naseem, S.; Abbas, N.; Ahmad, N.; Alomar, S. Y. Citrullus colocynthis-Mediated Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Antiproliferative Action against Breast Cancer Cells and Bactericidal Roles against Human Pathogens. Nanomaterials 2022, 12(21), 3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivas, K.; Sahu, S.; Patra, G. K.; Jaiswal, N. K.; Shankar, R. Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance of Silver Nanoparticles for Sensitive Colorimetric Detection of Chromium in Surface Water, Industrial Waste Water and Vegetable Samples. Analytical Methods 2016, 8(9), 2088–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirtarighat, S.; Ghannadnia, M.; Baghshahi, S. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using the Plant Extract of Salvia spinosa Grown In Vitro and Their Antibacterial Activity Assessment. Journal of Nanostructure in Chemistry 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, M. Q.; Khalil, A. T.; Ali, M.; Shah, M.; Ayaz, M.; Shinwari, Z. K. Phytochemical Analysis, Ephedra procera C.A. Mey.-Mediated Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles, Their Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Potentials. Medicina 2019, 55 (7), 369.

- Mehata, M. S. Surface Plasmon Resonance and Photoluminescence Properties of Silver Nanoparticles: A Review. Journal of Nanomedicine Research 2017, 5(2), 00113. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.; Kim, Y. J.; Zhang, D.; Yang, D. C. Biological Synthesis of Nanoparticles from Plants and Microorganisms. Trends in Biotechnology 2016, 34(7), 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V. K.; Yngard, R. A.; Lin, Y. Silver Nanoparticles: Green Synthesis and Their Antimicrobial Activities. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2009, 145 (1–2), 83–96.

- Garza-Cervantes, J. A.; Mendiola-Garza, G. M.; de Melo, E. M.; Salas-Villalobos, T. L.; Ortega-Rivera, O. A.; Martínez-Hernández, J. L.; Chávez-Morán, M. D. L. C.; Morones-Ramírez, J. R. Cellulose-Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: UV-Vis Confirmation of SPR Peak Centered at 407 nm. Nanomaterials 2020, 10(9), 1846. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, M.; Karimi, N. Green Synthesis and Biomedical Applications of Metal Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts: A Review. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2023, 49, 102747. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. ; Saifullah; Ahmad, M., Swami, B. L., Eds.; Ikram, S. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts and Their Antimicrobial Activities: A Review of Recent Literature. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2023, 30 (3), 103531. [Google Scholar]

- Takáč, P. The Role of Silver Nanoparticles in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer: Are There Any Perspectives for the Future? Life 2023, 13(2), 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gengan, R. M.; Anand, K.; Phulukdaree, A.; Chuturgoon, A. A. A549 Lung Cell Line Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized with Mentha spicata (Spearmint) Extract. Materials Letters 2013, 105, 264–267. [Google Scholar]

- Gurunathan, S.; Han, J. W.; Eppakayala, V.; Jeyaraj, M.; Kim, J. H. Cytotoxicity of Biologically Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles in MDA-MB-231 Human Breast Cancer Cells. BioMed Research International 2013, 2013, 535796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R. L.; Torre, L. A.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2018, 68 (6), 394–424.

- Patra, J. K.; Baek, K. H. Green Nanobiotechnology: Factors Affecting Synthesis and Characterization Techniques. Journal of Nanomaterials 2014, 2014, 417305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).