Submitted:

18 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of Plant Extracts

2.2.2. Phytochemical Analysis

2.2.3. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) Estimation

2.2.4. Biogenic Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles (SNPs)

2.2.5. Optimization of SNP Synthesis

2.2.6. Visual Inspection

2.2.7. UV–Visible Spectroscopy

2.2.8. Stability Study

2.2.9. Characterization of SNPs

2.2.10. Antimicrobial Activity

2.2.11. Anticoagulant Activity

2.2.12. In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Assays

2.2.13. In Vitro Antioxidant Assays

2.2.15. Tyrosinase Inhibition

2.2.16. In Vitro Cytotoxicity

2.2.17. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phytochemical Analysis

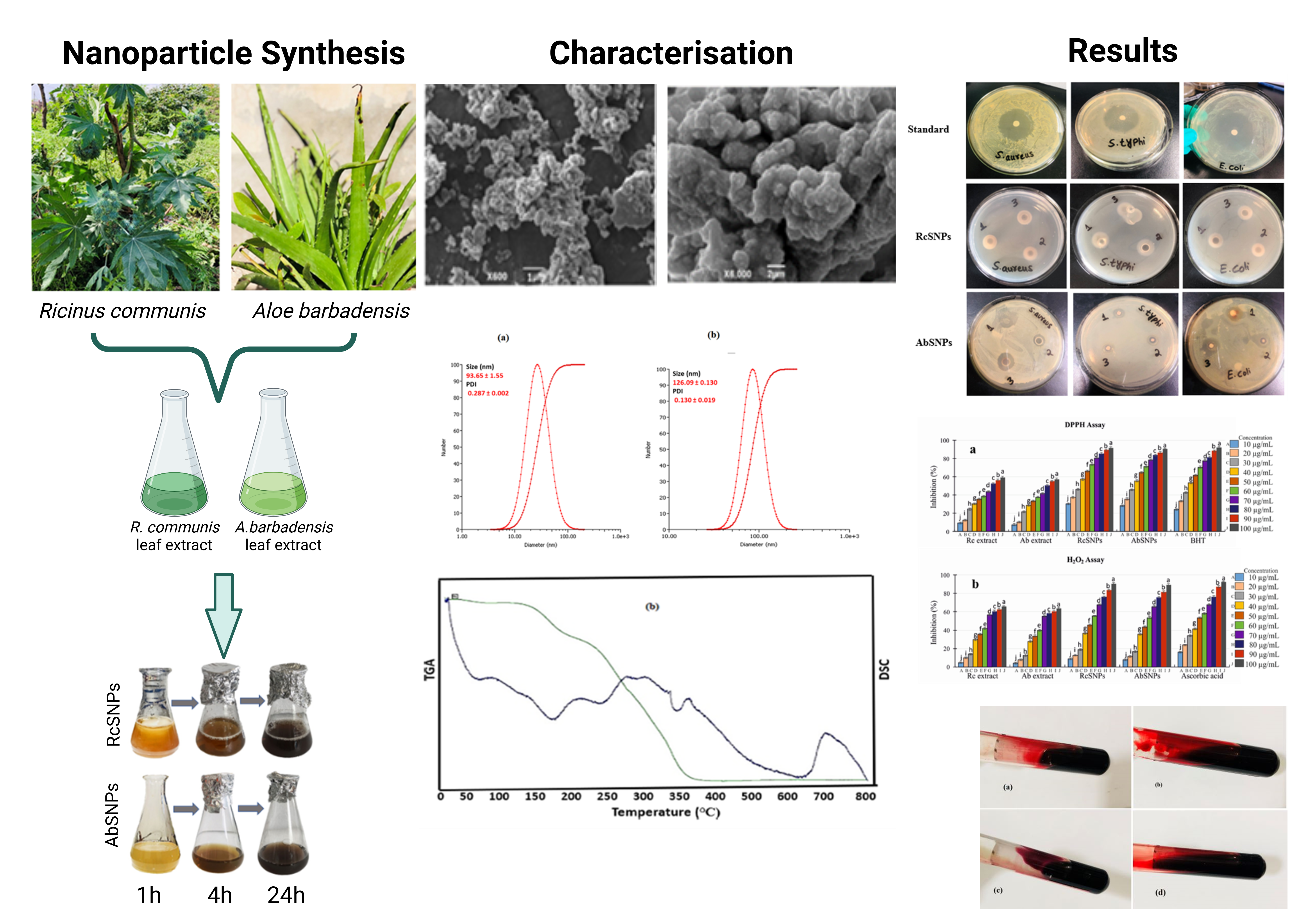

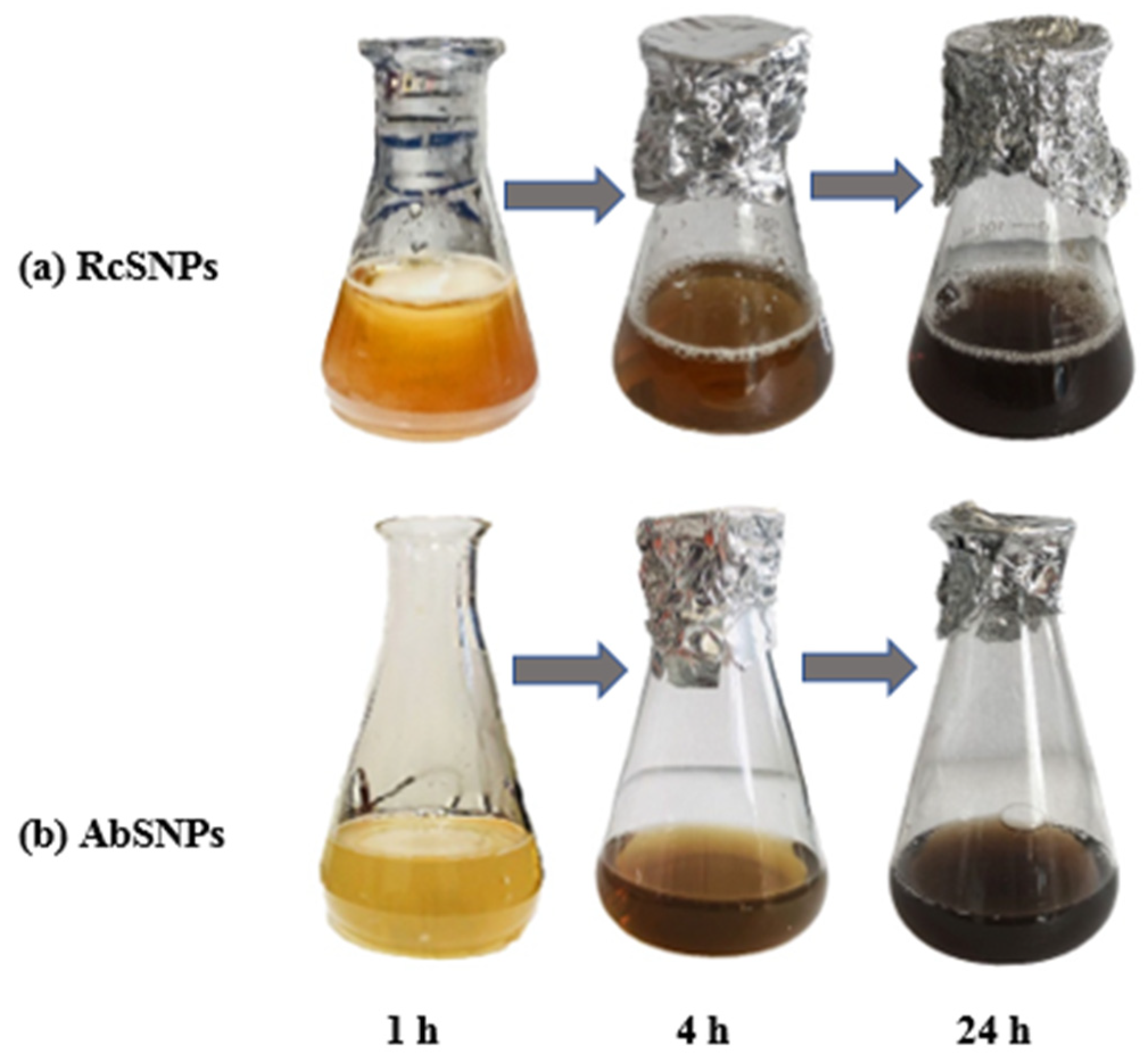

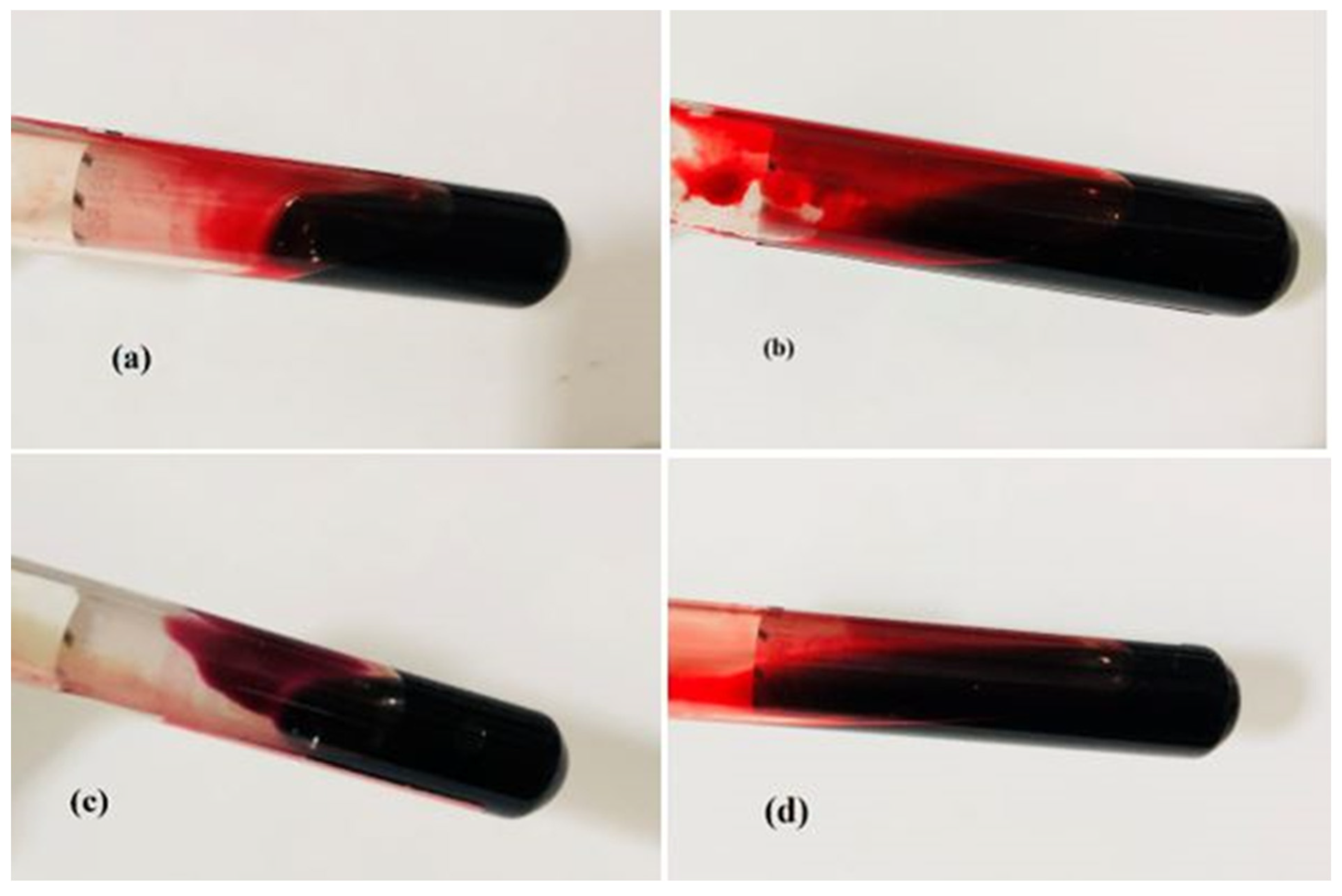

3.2. Visual Inspection

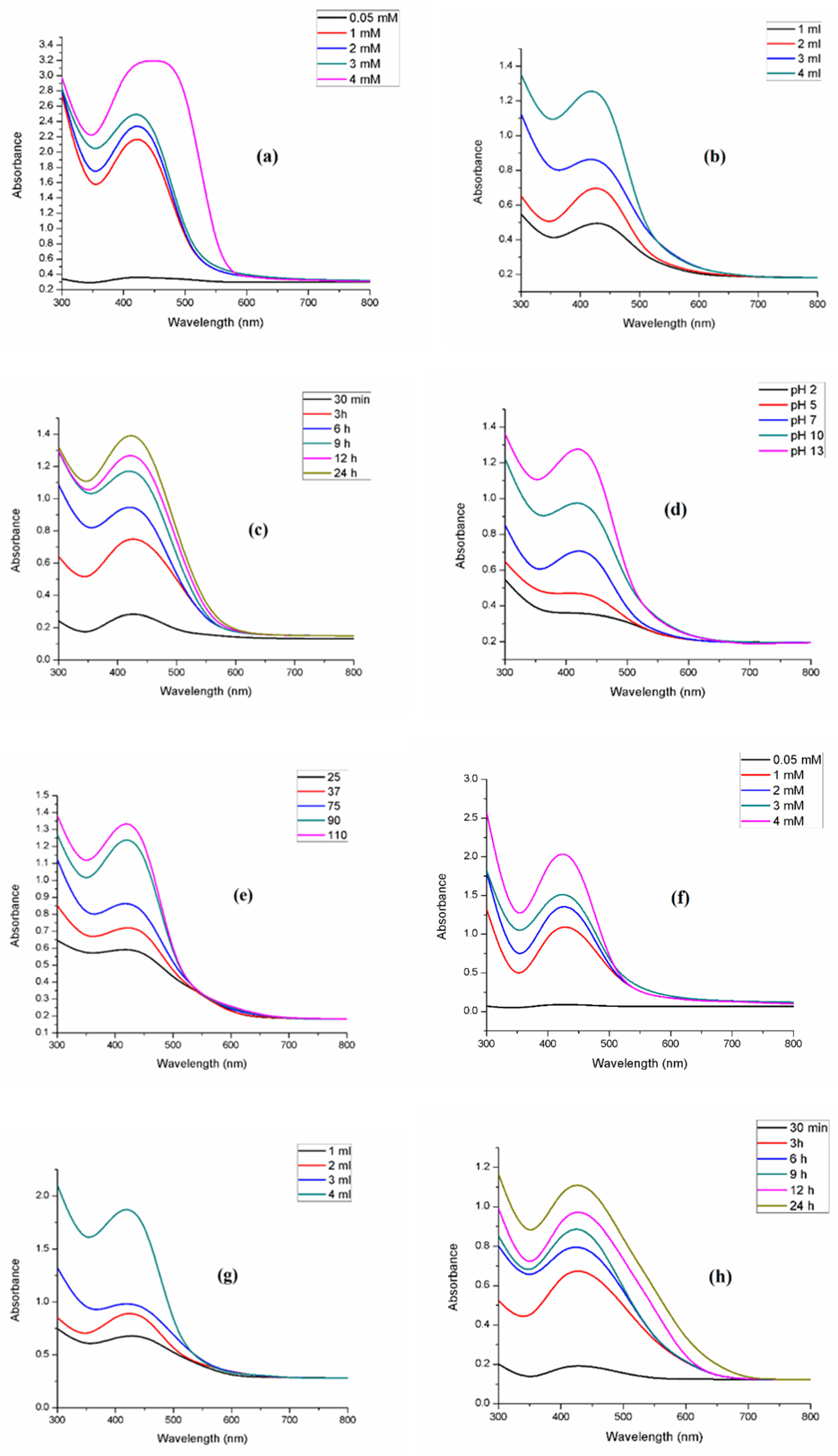

3.3. UV-Visible Spectroscopy

3.3.1. Effect of AgNO3 Concentration

3.3.2. Effect of Leaf Extract Concentration

3.3.3. Effect of Reaction Time

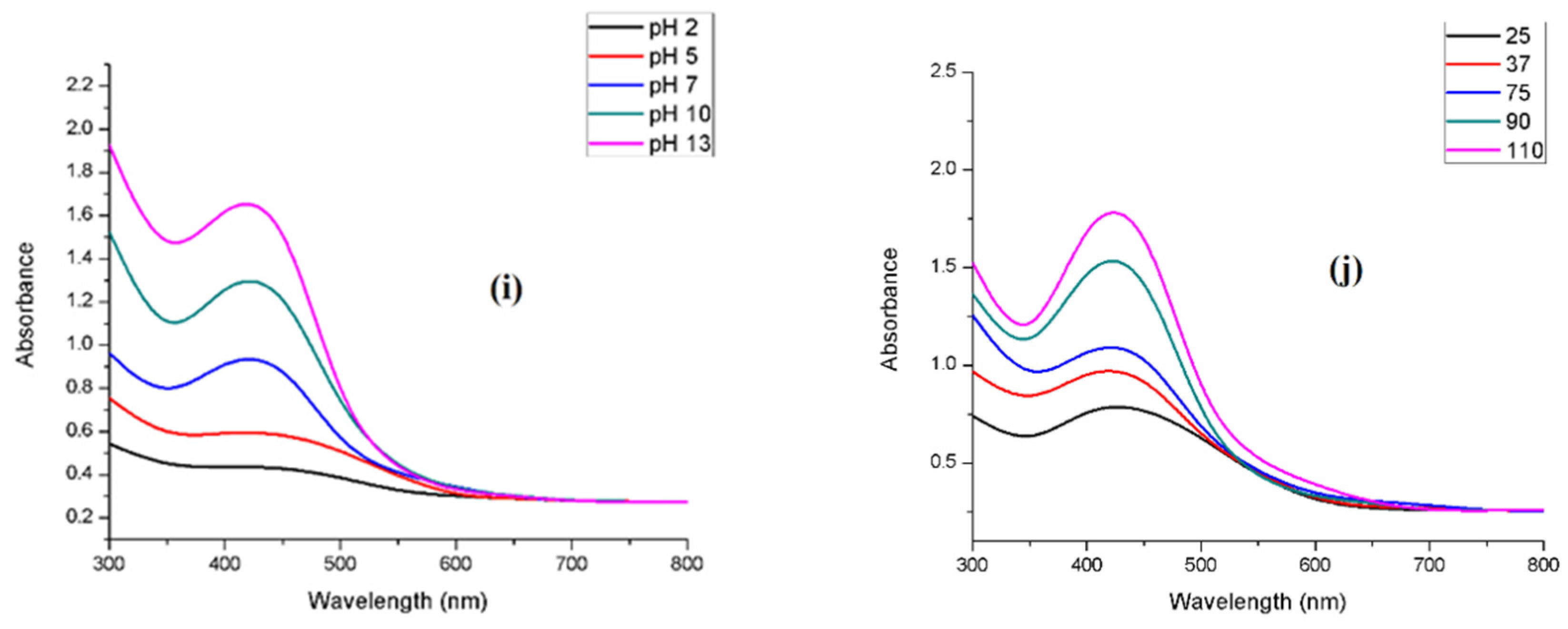

3.3.4. Effect of pH

3.3.5. Effect of Temperature

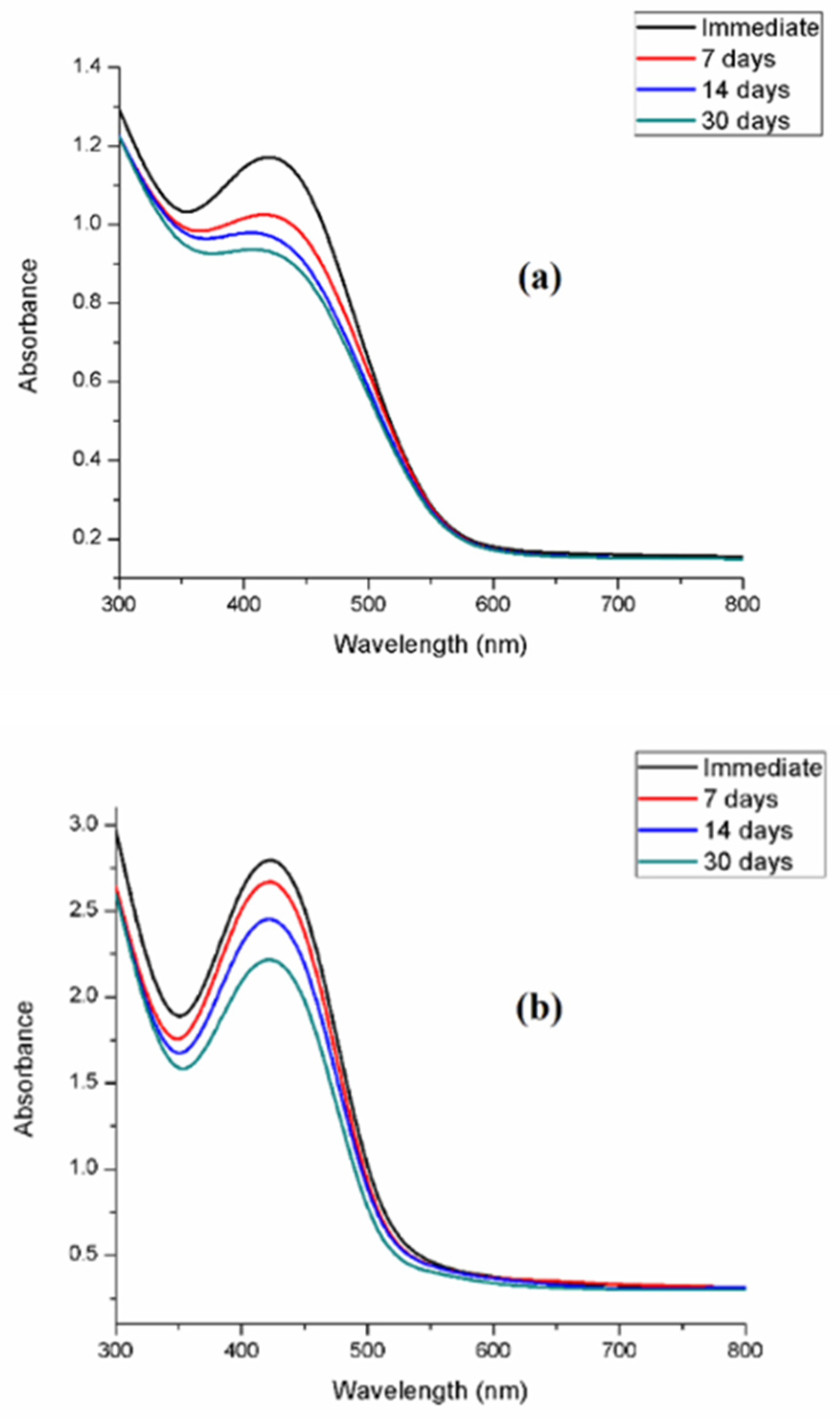

3.4. Stability of Synthesized SNPs

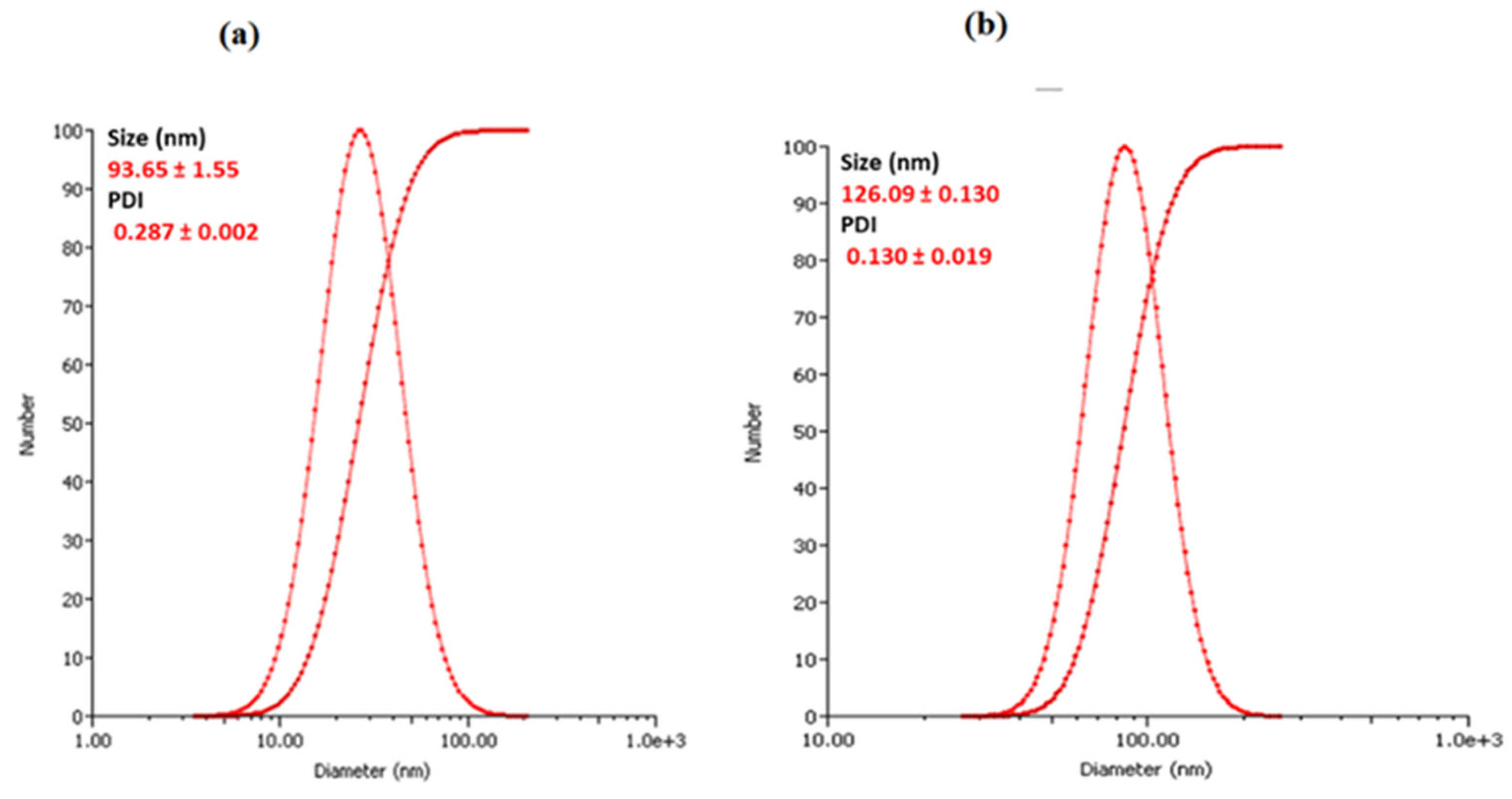

3.5. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Zeta Potential (ZP) Analysis

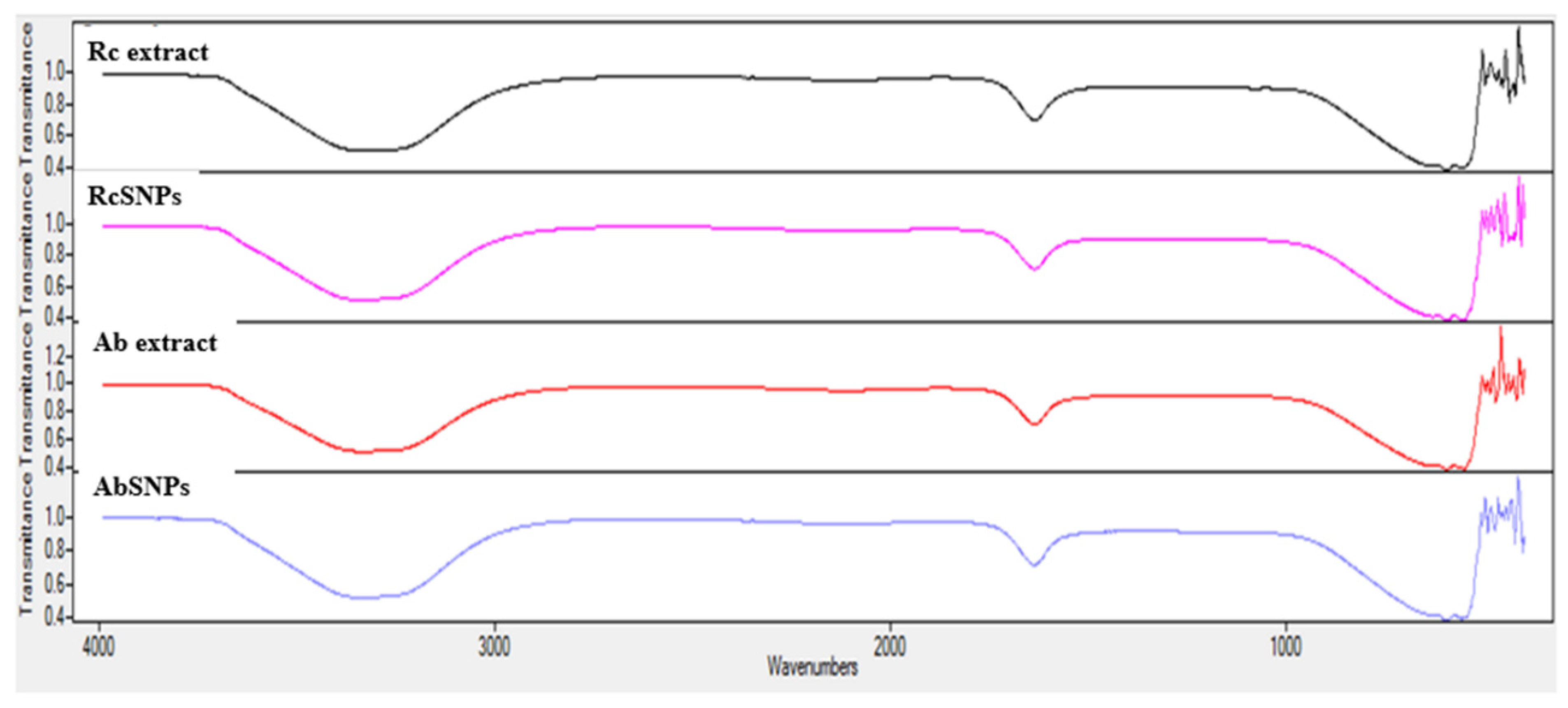

3.6. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

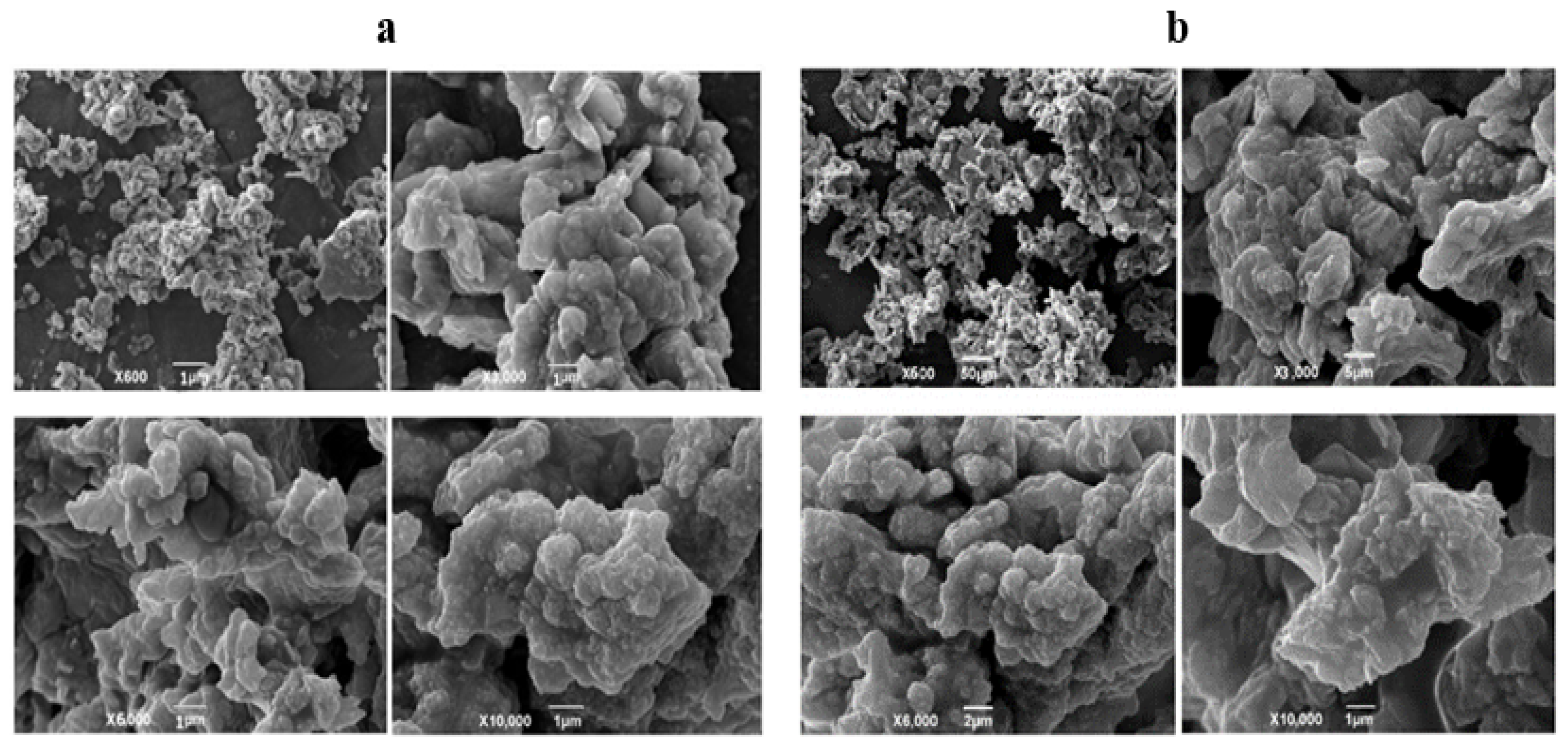

3.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

3.8. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

3.9. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

3.10. Antimicrobial Activity of Biogenic SNPs

3.11. Anticoagulant Activity

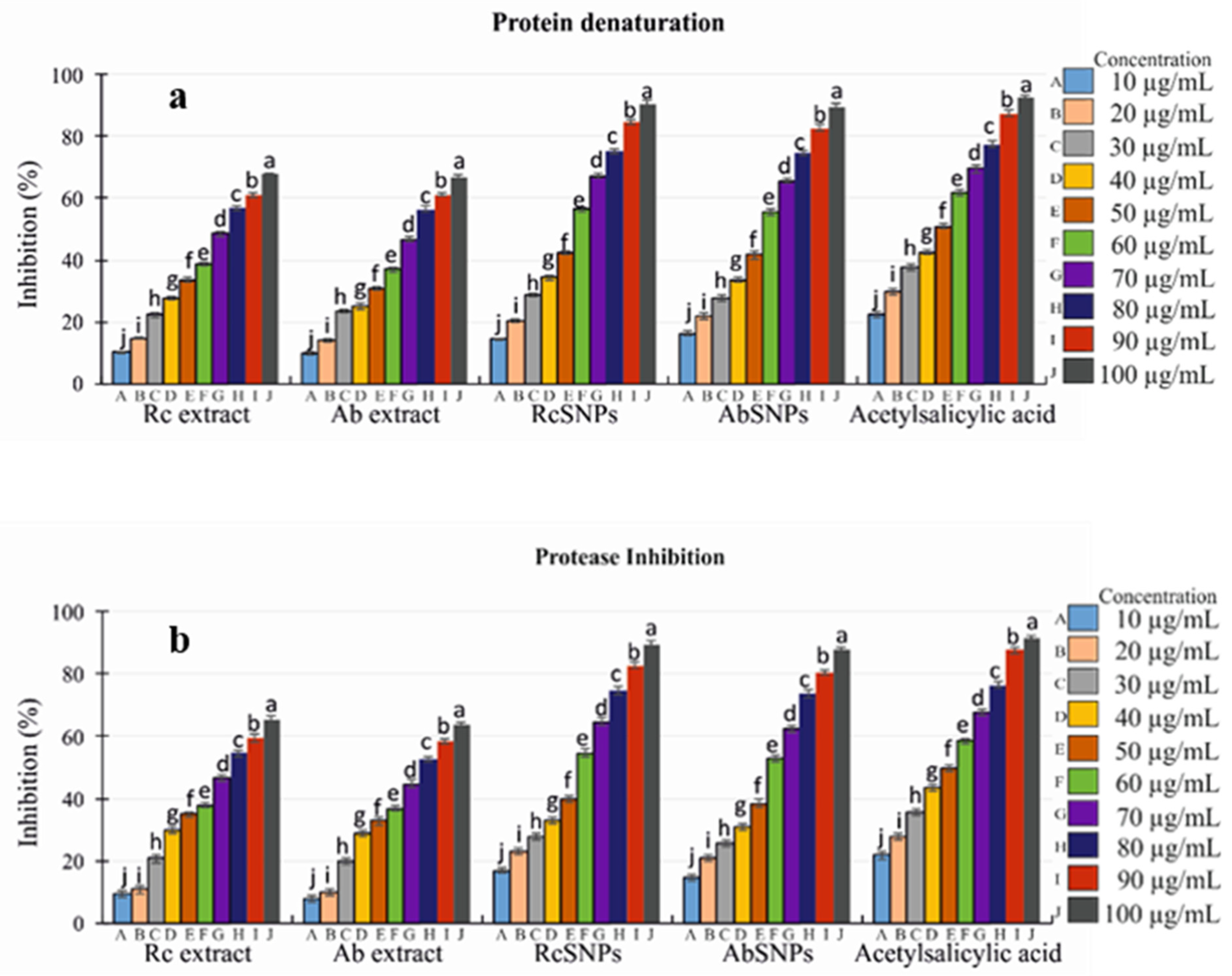

3.12. In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Assay

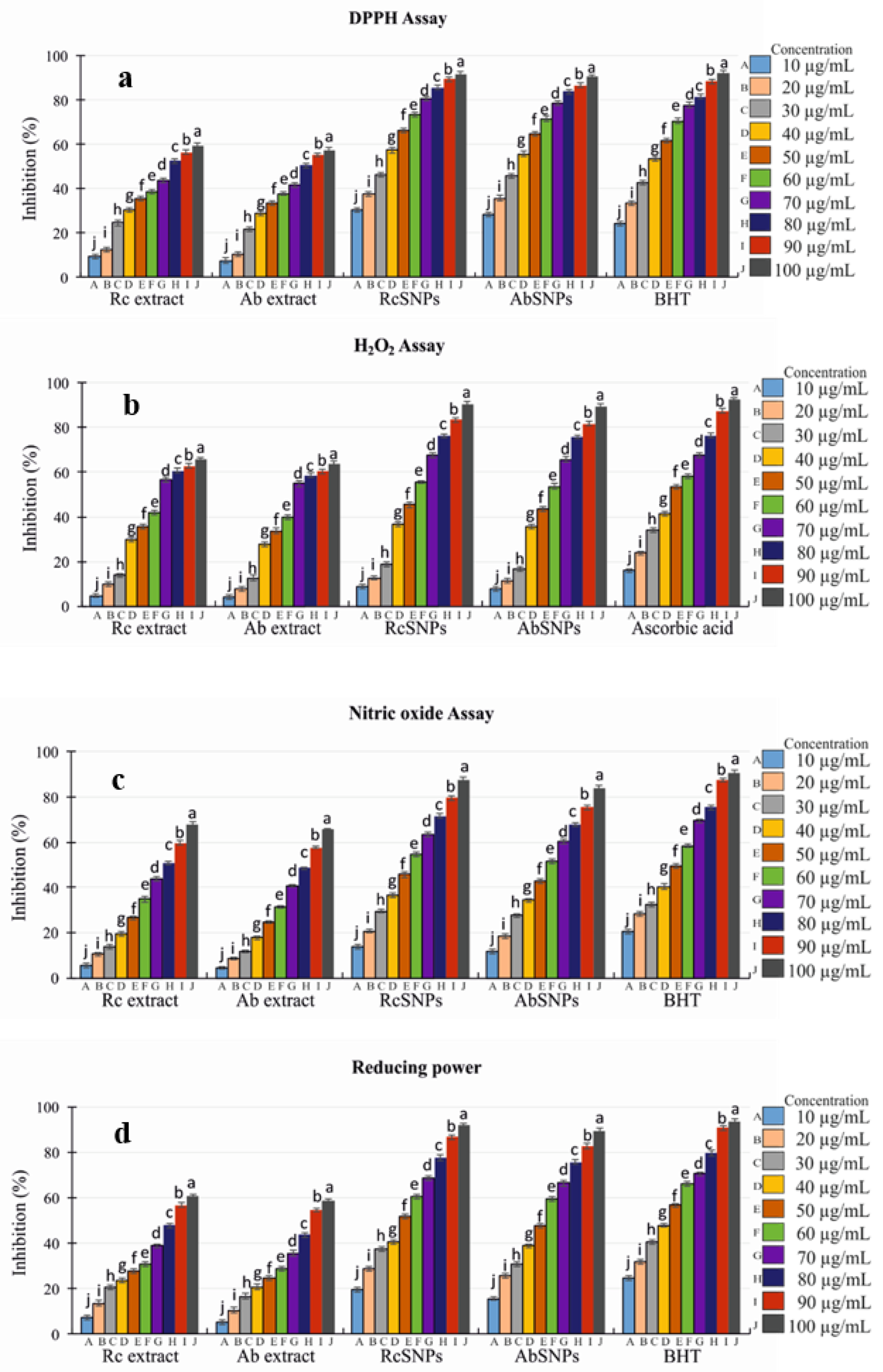

3.13. In Vitro Antioxidant Assay

3.14. Tyrosinase Inhibition Activity

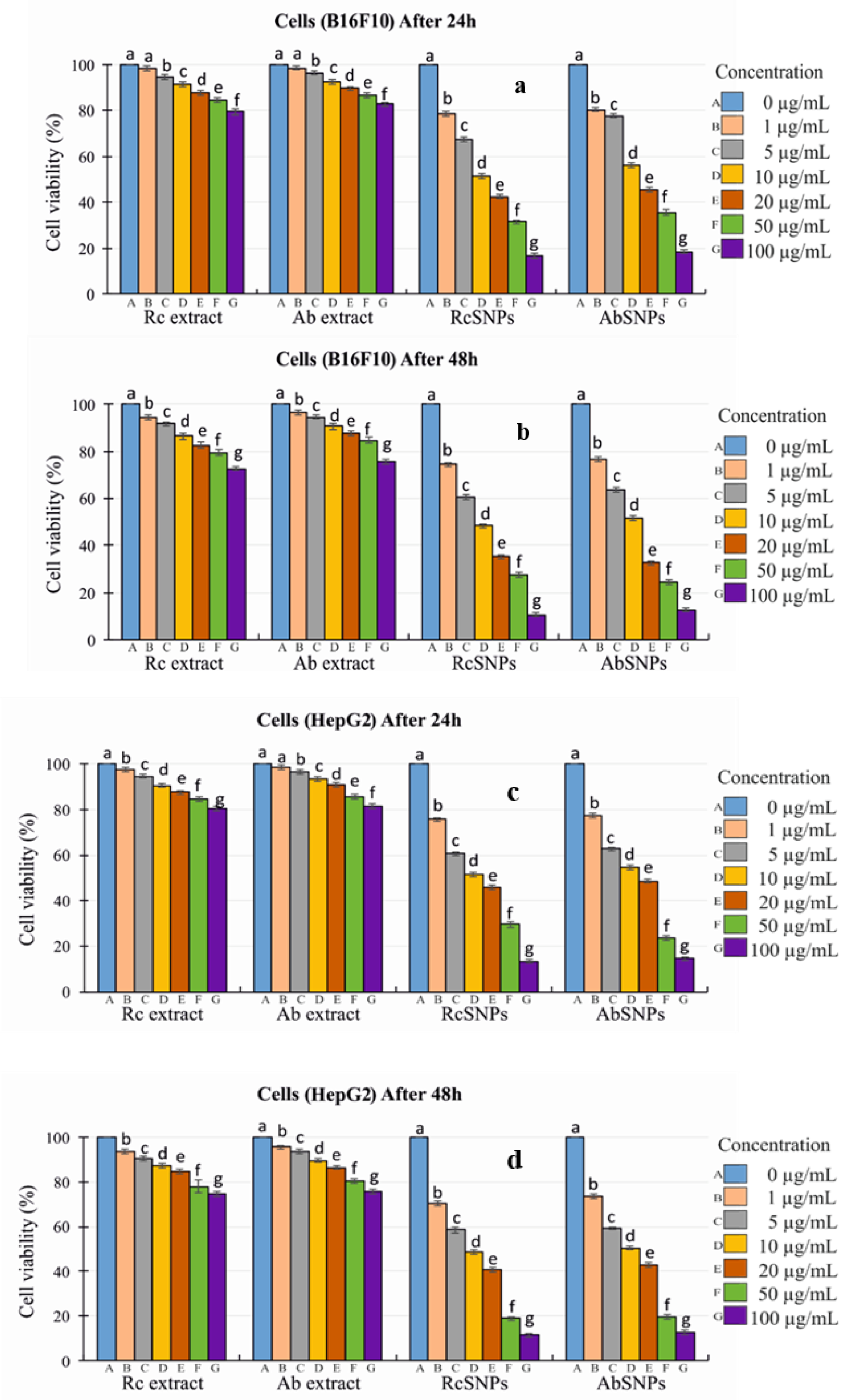

3.15. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis and Optimization of Silver Nanoparticles (SNPs)

4.2. Proposed Mechanism for RcSNPs and AbSNPs Synthesis

4.3. Characterization of SNPs

4.4. Therapeutic Evaluation of SNPs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamida, R.S.; Abdelmeguid, N.E.; Ali, M.A.; Bin-Meferij, M.M.; Khalil, M.I. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using a novel cyanobacteria Desertifilum sp. extract: their antibacterial and cytotoxicity effects. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 49-63.

- Sriramulu, M.; Sumathi, S. Photocatalytic, antioxidant, antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity of silver nanoparticles synthesised using forest and edible mushroom. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 8, 045012.

- Lateef, A.;S Folarin, B.I.; Oladejo, S.M.; Akinola, P.O.; Beukes, L.S.; Gueguim-Kana, E.B. Characterization, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticoagulant activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Petiveria alliacea L. leaf extract. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 48, 646-652.

- Odeniyi, M.A.; Okumah, V.C.; Adebayo-Tayo, B.C.; Odeniyi, O.A. Green synthesis and cream formulations of silver nanoparticles of Nauclea latifolia (African peach) fruit extracts and evaluation of antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2020, 15, 100197.

- Fatima, R.; Priya, M.; Indurthi, L.; Radhakrishnan, V.; Sudhakaran, R. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using red algae Portieria hornemannii and its antibacterial activity against fish pathogens. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 138, 103780.

- Wypij, M.; Czarnecka, J.; Świecimska, M.; Dahm, H.; Rai, M.; Golinska, P. Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of biogenic silver nanoparticles synthesized from Streptomyces xinghaiensis OF1 strain. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 34, 23.

- Govindappa, M.; Hemashekhar, B.; Arthikala, M.-K.; Rai, V.R.; Ramachandra, Y. Characterization, antibacterial, antioxidant, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory and antityrosinase activity of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Calophyllum tomentosum leaves extract. Results Phys. 2018, 9, 400-408.

- Siddiquee, M.A.; ud din Parray, M.; Mehdi, S.H.; Alzahrani, K.A.; Alshehri, A.A.; Malik, M.A.; Patel, R. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Delonix regia leaf extracts: In-vitro cytotoxicity and interaction studies with bovine serum albumin. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 242, 122493.

- Das, P.; Ghosal, K.; Jana, N.K.; Mukherjee, A.; Basak, P. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using belladonna mother tincture and its efficacy as a potential antibacterial and anti-inflammatory agent. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 228, 310-317.

- Ravichandran, V.; Vasanthi, S.; Shalini, S.; Shah, S.A.A.; Tripathy, M.; Paliwal, N. Green synthesis, characterization, antibacterial, antioxidant and photocatalytic activity of Parkia speciosa leaves extract mediated silver nanoparticles. Results Phys. 2019, 15, 102565.

- Hamedi, S.; Shojaosadati, S.A. Rapid and green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Diospyros lotus extract: Evaluation of their biological and catalytic activities. Polyhedron 2019, 171, 172-180.

- Vanlalveni, C.; Lallianrawna, S.; Biswas, A.; Selvaraj, M.; Changmai, B.; Rokhum, S.L. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plant extracts and their antimicrobial activities: A review of recent literature. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 2804-2837.

- Ahsan, A.; Farooq, M.A. Therapeutic potential of green synthesized silver nanoparticles loaded PVA hydrogel patches for wound healing. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 101308.

- Girón-Vázquez, N.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, C.; Soto-Robles, C.; Nava, O.; Lugo-Medina, E.; Castrejón-Sánchez, V.; Vilchis-Nestor, A.; Luque, P. Study of the effect of Persea americana seed in the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their antimicrobial properties. Results Phys. 2019, 13, 102142.

- Thomas, B.; Vithiya, B.; Prasad, T.; Mohamed, S.; Magdalane, C.M.; Kaviyarasu, K.; Maaza, M. Antioxidant and photocatalytic activity of aqueous leaf extract mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Passiflora edulis f. flavicarpa. J. Nanoscience Nanotechnol. 2019, 19, 2640-2648.

- Kumar, P.V.; Kalyani, R.; Veerla, S.C.; Kollu, P.; Shameem, U.; Pammi, S. Biogenic synthesis of stable silver nanoparticles via Asparagus racemosus root extract and their antibacterial efficacy towards human and fish bacterial pathogens. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 104008.

- Singh, P.; Ahn, S.; Kang, J.-P.; Veronika, S.; Huo, Y.; Singh, H.; Chokkaligam, M.; El-Agamy Farh, M.; Aceituno, V.C.; Kim, Y.J. In vitro anti-inflammatory activity of spherical silver nanoparticles and monodisperse hexagonal gold nanoparticles by fruit extract of Prunus serrulata: a green synthetic approach. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 2022-2032.

- Khosravi, A.; Zarepour, A.; Iravani, S.; Varma, R.S.; Zarrabi, A. Sustainable synthesis: natural processes shaping the nanocircular economy. Environ. Sci.: Nano 2024, 11, 688-707.

- Babu, A.T.; Antony, R. Green synthesis of silver doped nano metal oxides of zinc & copper for antibacterial properties, adsorption, catalytic hydrogenation & photodegradation of aromatics. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 102840.

- Khojasteh, D.; Kazerooni, M.; Salarian, S.; Kamali, R. Droplet impact on superhydrophobic surfaces: A review of recent developments. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2016, 42, 1-14.

- Kumar, V.; Singh, D.K.; Mohan, S.; Gundampati, R.K.; Hasan, S.H. Photoinduced green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Physalis angulata and its antibacterial and antioxidant activity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 744-756.

- Sowmyya, T. Spectroscopic investigation on catalytic and bactericidal properties of biogenic silver nanoparticles synthesized using Soymida febrifuga aqueous stem bark extract. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 3590-3601.

- Vickers, N.J. Animal communication: when i’m calling you, will you answer too? Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R713-R715.

- Parlinska-Wojtan, M.; Kus-Liskiewicz, M.; Depciuch, J.; Sadik, O. Green synthesis and antibacterial effects of aqueous colloidal solutions of silver nanoparticles using camomile terpenoids as a combined reducing and capping agent. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 39, 1213-1223.

- Melo, P.S.; Massarioli, A.P.; Denny, C.; dos Santos, L.F.; Franchin, M.; Pereira, G.E.; de Souza Vieira, T.M.F.; Rosalen, P.L.; de Alencar, S.M. Winery by-products: Extraction optimization, phenolic composition and cytotoxic evaluation to act as a new source of scavenging of reactive oxygen species. Food Chem. 2015, 181, 160-169.

- Raota, C.S.; Cerbaro, A.F.; Salvador, M.; Delamare, A.P.L.; Echeverrigaray, S.; da Silva Crespo, J.; da Silva, T.B.; Giovanela, M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using an extract of Ives cultivar (Vitis labrusca) pomace: Characterization and application in wastewater disinfection. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103383.

- Behravan, M.; Panahi, A.H.; Naghizadeh, A.; Ziaee, M.; Mahdavi, R.; Mirzapour, A. Facile green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Berberis vulgaris leaf and root aqueous extract and its antibacterial activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 124, 148-154.

- Azad, A.; Zafar, H.; Raza, F.; Sulaiman, M. Factors influencing the green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles using plant extracts: a comprehensive review. Pharm. Fronts 2023, 5, e117-e131.

- Bhatnagar, S.; Aoyagi, H. Current overview of the mechanistic pathways and influence of physicochemical parameters on the microbial synthesis and applications of metallic nanoparticles. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 1-22.

- Evans, W.C. Trease and Evans’ pharmacognosy. Gen. Pharmacol. 1997, 2, 291.

- Urquiaga, I.; Leighton, F. Plant polyphenol antioxidants and oxidative stress. Biol. Res. 2000, 33, 55-64.

- Obadoni, B.; Ochuko, P. Phytochemical studies and comparative efficacy of the crude extracts of some haemostatic plants in Edo and Delta States of Nigeria. Glob. J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2002, 8, 203-208.

- Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Ponmurugan, K.; Jeganathan, P.M. Development and validation of ultrasound-assisted solid-liquid extraction of phenolic compounds from waste spent coffee grounds. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 34, 206-213.

- Ojo, O.A.; Oyinloye, B.E.; Ojo, A.B.; Afolabi, O.B.; Peters, O.A.; Olaiya, O.; Fadaka, A.; Jonathan, J.; Osunlana, O. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using Talinum triangulare (Jacq.) Willd. leaf extract and monitoring their antimicrobial activity. J. Bionanosci. 2017, 11, 292-296.

- Kumar, B.; Smita, K.; Cumbal, L.; Debut, A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Andean blackberry fruit extract. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 45-50.

- Yildirim, K.; Atas, C.; Simsek, E.; Coban, A.Y. The effect of inoculum size on antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e00319-00323.

- BEHERA, M.; SOREN, S.; SINGH, N.R.; SIPRA, B.; SETHI, G.; MAHANANDIA, S.; PRADHAN, B.; BHANJADEO, M. Green Synthesis of Bovine Serum Albumin Conjugated Silver Nanoparticles at Different Temperatures and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activity. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 86.

- Banik, S.; Biswas, S.; Karmakar, S. Extraction, purification, and activity of protease from the leaves of Moringa oleifera. F1000Res. 2018, 7, 1151.

- Prem, P.; Naveenkumar, S.; Kamaraj, C.; Ragavendran, C.; Priyadharsan, A.; Manimaran, K.; Alharbi, N.S.; Rarokar, N.; Cherian, T.; Sugumar, V. Valeriana jatamansi root extract a potent source for biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biomedical applications, and photocatalytic decomposition. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2024, 17, 2305142.

- Shankar, S.; Murthy, A.N.; Rachitha, P.; Raghavendra, V.B.; Sunayana, N.; Chinnathambi, A.; Alharbi, S.A.; Basavegowda, N.; Brindhadevi, K.; Pugazhendhi, A. RETRACTED: Silk sericin conjugated magnesium oxide nanoparticles for its antioxidant, anti-aging, and anti-biofilm activities. 2023.

- Pathak, P.; Shukla, P.; Kanshana, J.S.; Jagavelu, K.; Sangwan, N.S.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Dikshit, M. Standardized root extract of Withania somnifera and Withanolide A exert moderate vasorelaxant effect in the rat aortic rings by enhancing nitric oxide generation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 278, 114296.

- Alemu, B.; Molla, M.D.; Tezera, H.; Dekebo, A.; Asmamaw, T. Phytochemical composition and in vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Bersama abyssinica F. seed extracts. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6345.

- Chandrasekhar, N.; Vinay, S. Yellow colored blooms of Argemone mexicana and Turnera ulmifolia mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and study of their antibacterial and antioxidant activity. Appl. Nanosci. 2017, 7, 851-861.

- Giridasappa, A.; Ismail, S.M.; Gopinath, S. Antioxidant, Bactericidal, Antihemolytic, and Anticancer Assessment Activities of Al2O3, SnO2, and Green Synthesized Ag and CuO NPs. In Handbook of Sustainable Materials: Modelling, Characterization, and Optimization; CRC Press: 2023; pp. 367-398.

- Shahzadi, S.; Fatima, S.; Shafiq, Z.; Janjua, M.R.S.A. A review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (SNPs) using plant extracts: a multifaceted approach in photocatalysis, environmental remediation, and biomedicine. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 3858-3903.

- Mughal, S.S. Role of silver nanoparticles in colorimetric detection of biomolecules. Authorea Preprints 2022.

- Alim-Al-Razy, M.; Bayazid, G.A.; Rahman, R.U.; Bosu, R.; Shamma, S.S. Silver nanoparticle synthesis, UV-Vis spectroscopy to find particle size and measure resistance of colloidal solution. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2020; p. 012020.

- Gao, C.; Lu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chi, M.; Cheng, Q.; Yin, Y. Highly stable silver nanoplates for surface plasmon resonance biosensing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5629-5633.

- Jia, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, L.; Yang, D.; Kanaev, A. Dynamic light scattering: a powerful tool for in situ nanoparticle sizing. Colloids Interfaces 2023, 7, 15.

- Sun, Q.; Cai, X.; Li, J.; Zheng, M.; Chen, Z.; Yu, C.-P. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using tea leaf extract and evaluation of their stability and antibacterial activity. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 444, 226-231.

- Kumaran, N.S. In vitro anti-inflammatory activity of silver nanoparticle synthesized Avicennia marina (Forssk.) Vierh.: A green synthetic approach. Int. J. Green Pharm. 2018, 12.

- Yakop, F.; Abd Ghafar, S.A.; Yong, Y.K.; Saiful Yazan, L.; Mohamad Hanafiah, R.; Lim, V.; Eshak, Z. Silver nanoparticles Clinacanthus Nutans leaves extract induced apoptosis towards oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 131-139.

- Nasrollahzadeh, M.; Issaabadi, Z.; Sajadi, S.M. Green synthesis of the Ag/Al2O3 nanoparticles using Bryonia alba leaf extract and their catalytic application for the degradation of organic pollutants. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electro 2019, 30, 3847-3859.

- Deshpande, B.; Sharma, D.; Pandey, B. Phytochemicals and antibacterial screening of Parthenium hysterophorus. Indian J. Sci. Res 2017, 13, 199-202.

- Khan, T.; Ullah, N.; Khan, M.A.; Mashwani, Z.-u.-R.; Nadhman, A. Plant-based gold nanoparticles; a comprehensive review of the decade-long research on synthesis, mechanistic aspects and diverse applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 272, 102017.

- Abomughaid, M.M.; Teibo, J.O.; Akinfe, O.A.; Adewolu, A.M.; Teibo, T.K.A.; Afifi, M.; Al-Farga, A.M.H.; Al-kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Alexiou, A. A phytochemical and pharmacological review of Ricinus communis L. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 315.

- Singh, R. Chemotaxonomy of medicinal plants: possibilities and limitations. In Natural products and drug discovery; Elsevier: 2018; pp. 119-136.

- Dharajiya, D.; Pagi, N.; Jasani, H.; Patel, P. Antimicrobial activity and phytochemical screening of Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller). Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci 2017, 6, 2152-2162.

- Baba, S.A.; Malik, S.A. Determination of total phenolic and flavonoid content, antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of a root extract of Arisaema jacquemontii Blume. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2015, 9, 449-454.

- Chen, Z.; Świsłocka, R.; Choińska, R.; Marszałek, K.; Dąbrowska, A.; Lewandowski, W.; Lewandowska, H. Exploring the correlation between the molecular structure and biological activities of metal–phenolic compound complexes: research and description of the role of metal ions in improving the antioxidant activities of phenolic compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11775.

- Dakshayani, S.; Marulasiddeshwara, M.; Sharath Kumar, M.; Raghavendra Kumar, P.; Devaraja, S. Antimicrobial, anticoagulant and antiplatelet activities of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Selaginella (Sanjeevini) plant extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 131, 787-797.

- Song, X.-C.; Canellas, E.; Asensio, E.; Nerín, C. Predicting the antioxidant capacity and total phenolic content of bearberry leaves by data fusion of UV–Vis spectroscopy and UHPLC/Q-TOF-MS. Talanta 2020, 213, 120831.

- Lama-Muñoz, A.; del Mar Contreras, M.; Espínola, F.; Moya, M.; Romero, I.; Castro, E. Content of phenolic compounds and mannitol in olive leaves extracts from six Spanish cultivars: Extraction with the Soxhlet method and pressurized liquids. Food Chem 2020, 320, 126626.

- Ahmed-Gaid, K.; Ahmed-Gaid, N.E.Y.; Hanoun, S.; Chenna, H.; Ghenaiet, K.; Ahmed-Gaid, H.; Hadef, Y. PHENOLIC COMPOUNDS, ANTIOXIDANT, AND ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITIES OF METHANOLIC EXTRACT FROM THE SAHARAN ENDEMIC PLANT HALOXYLON SCOPARIUM POMEL. Bull. Pharm. Sci. Assiut Univ. 2025, 48, 267-276.

- Marius, L.; Kini, F.; Pierre, D.; Pierre, G.I. In vitro antioxidant activity and phenolic contents of different fractions of ethanolic extract from Khaya senegalensis A. Juss.(Meliaceae) stem barks. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2016, 10, 501-507.

- Khawory, M.H.; Amanah, A.; Salin, N.H.; Mohd Subki, M.F.; Mohd Nasim, N.N.; Noordin, M.I.; Wahab, H.A. Effects of Gamma Radiation Treatment on Medicinal Plants for Both Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Phenolic Acid. Available at SSRN 4334860.

- Veerasamy, R.; Xin, T.Z.; Gunasagaran, S.; Xiang, T.F.W.; Yang, E.F.C.; Jeyakumar, N.; Dhanaraj, S.A. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using mangosteen leaf extract and evaluation of their antimicrobial activities. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2011, 15, 113-120.

- Banerjee, P.; Satapathy, M.; Mukhopahayay, A.; Das, P. Leaf extract mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from widely available Indian plants: synthesis, characterization, antimicrobial property and toxicity analysis. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2014, 1, 3.

- Chandran, N.; Bayal, M.; Pilankatta, R.; Nair, S.S. Tuning of surface Plasmon resonance (SPR) in metallic nanoparticles for their applications in SERS. In Nanomaterials for luminescent devices, sensors, and bio-imaging applications; Springer: 2021; pp. 39-66.

- Yadav, M.; Gaur, N.; Wahi, N.; Singh, S.; Kumar, K.; Amoozegar, A.; Sharma, E. Phytochemical-Assisted Fabrication of Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles from Vitex negundo: Structural Features, Antibacterial Activity, and Cytotoxicity Evaluation. Colloids Interfaces 2025, 9, 55.

- Kale, G.; Bhatkar, D.; Rokade, S.; Ingle, P.; Patil, R. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica leaves extract and characterization by UV. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 1695, 1995-1699.

- Markus, J.; Wang, D.; Kim, Y.-J.; Ahn, S.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Wang, C.; Yang, D.C. Biosynthesis, characterization, and bioactivities evaluation of silver and gold nanoparticles mediated by the roots of Chinese herbal Angelica pubescens Maxim. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 46.

- Kaabipour, S.; Hemmati, S. A review on the green and sustainable synthesis of silver nanoparticles and one-dimensional silver nanostructures. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2021, 12, 102-136.

- Chirumamilla, P.; Dharavath, S.B.; Taduri, S. Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from leaf extract of Solanum khasianum: optical properties and biological applications. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 353-368.

- Sinha, S.N.; Paul, D.; Halder, N.; Sengupta, D.; Patra, S.K. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using fresh water green alga Pithophora oedogonia (Mont.) Wittrock and evaluation of their antibacterial activity. Appl. Nanosci. 2015, 5, 703-709.

- Sasikala, A.; Linga Rao, M.; Savithramma, N.; Prasad, T. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles from stem bark of Cochlospermum religiosum (L.) Alston: an important medicinal plant and evaluation of their antimicrobial efficacy. Appl. Nanosci. 2015, 5, 827-835.

- Mariadoss, A.V.A.; Ramachandran, V.; Shalini, V.; Agilan, B.; Franklin, J.H.; Sanjay, K.; Alaa, Y.G.; Tawfiq, M.A.-A.; Ernest, D. Green synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles by Malus domestica and its cytotoxic effect on (MCF-7) cell line. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 135, 103609.

- Ahsan, A.; Farooq, M.A.; Ahsan Bajwa, A.; Parveen, A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Parthenium hysterophorus: optimization, characterization and in vitro therapeutic evaluation. Molecules 2020, 25, 3324.

- Macovei, I.; Luca, S.V.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K.; Horhogea, C.E.; Rimbu, C.M.; Sacarescu, L.; Vochita, G.; Gherghel, D.; Ivanescu, B.L.; Panainte, A.D. Silver nanoparticles synthesized from abies alba and pinus sylvestris bark extracts: characterization, antioxidant, cytotoxic, and antibacterial effects. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 797.

- Halawani, E.M. Rapid biosynthesis method and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Zizyphus spina christi leaf extract and their antibacterial efficacy in therapeutic application. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 8, 22-35.

- Logeswari, P.; Silambarasan, S.; Abraham, J. Ecofriendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles from commercially available plant powders and their antibacterial properties. Sci. Iran. 2013, 20, 1049-1054.

- Iravani, S.; Zolfaghari, B. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Pinus eldarica bark extract. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 639725.

- Madaniyah, L.; Fiddaroini, S.; Hayati, E.K.; Rahman, M.F.; Sabarudin, A. Biosynthesis, characterization, and in-vitro anticancer effect of plant-mediated silver nanoparticles using Acalypha indica Linn: In-silico approach. OpenNano 2025, 21, 100220.

- Alirezalu, A.; Ahmadi, N.; Salehi, P.; Sonboli, A.; Alirezalu, K.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Barba, F.J.; Munekata, P.E.; Lorenzo, J.M. Physicochemical characterization, antioxidant activity, and phenolic compounds of hawthorn (Crataegus spp.) fruits species for potential use in food applications. Foods 2020, 9, 436.

- Arumugam, S.; Ramesh, P. Green synthesis and characterization of zirconium oxide nanoparticles using solanum trilobatum and its photodegradation activity. Sustain. Chem. Clim. Action 2025, 6, 100086.

- Ndikau, M.; Noah, N.M.; Andala, D.M.; Masika, E. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Citrullus lanatus fruit rind extract. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2017, 2017, 8108504.

- Kumar, R.; Roopan, S.M.; Prabhakarn, A.; Khanna, V.G.; Chakroborty, S. Agricultural waste Annona squamosa peel extract: biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2012, 90, 173-176.

- Das, J.; Das, M.P.; Velusamy, P. Sesbania grandiflora leaf extract mediated green synthesis of antibacterial silver nanoparticles against selected human pathogens. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013, 104, 265-270.

- Vanaja, M.; Paulkumar, K.; Gnanajobitha, G.; Rajeshkumar, S.; Malarkodi, C.; Annadurai, G. Herbal plant synthesis of antibacterial silver nanoparticles by Solanum trilobatum and its characterization. Int. J. Met. 2014, 2014, 692461.

- Sarip, N.A.; Aminudin, N.I.; Danial, W.H. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using Garcinia extracts: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 469-493.

- Patel, J.; Kumar, G.S.; Roy, H.; Maddiboyina, B.; Leporatti, S.; Bohara, R.A. From nature to nanomedicine: bioengineered metallic nanoparticles bridge the gap for medical applications. Discov. Nano 2024, 19, 85.

- Mintiwab, A.; Jeyaramraja, P. Evaluation of phytochemical components, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Ricinus communis leaf extracts. Vegetos 2021, 34, 606-618.

- Lim, S.H.; Park, Y. Green synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity of gold nanoparticles prepared using rosmarinic acid. J. Nanoscience Nanotechnol. 2018, 18, 659-667.

- Adebayo-Tayo, B.C.; Akinsete, T.O.; Odeniyi, O.A. Phytochemical composition and comparative evaluation of antimicrobial activities of the juice extract of Citrus aurantifolia and its silver nanoparticles. Niger. J. Pharm. Res. 2016, 12, 59-64.

- Dawadi, S.; Katuwal, S.; Gupta, A.; Lamichhane, U.; Thapa, R.; Jaisi, S.; Lamichhane, G.; Bhattarai, D.P.; Parajuli, N. Current research on silver nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, and applications. J. Nanomater. 2021, 2021, 6687290.

- Pochapski, D.J.; Carvalho dos Santos, C.; Leite, G.W.; Pulcinelli, S.H.; Santilli, C.V. Zeta potential and colloidal stability predictions for inorganic nanoparticle dispersions: Effects of experimental conditions and electrokinetic models on the interpretation of results. Langmuir 2021, 37, 13379-13389.

- Gengan, R.; Anand, K.; Phulukdaree, A.; Chuturgoon, A. A549 lung cell line activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using Albizia adianthifolia leaf. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 2013, 105, 87-91.

- Varadavenkatesan, T.; Selvaraj, R.; Vinayagam, R. Phyto-synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Mussaenda erythrophylla leaf extract and their application in catalytic degradation of methyl orange dye. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 221, 1063-1070.

- Padalia, H.; Moteriya, P.; Chanda, S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from marigold flower and its synergistic antimicrobial potential. Arab. J. Chem. 2015, 8, 732-741.

- Salih, A.M.; Al-Qurainy, F.; Khan, S.; Nadeem, M.; Tarroum, M.; Shaikhaldein, H.O. Biogenic silver nanoparticles improve bioactive compounds in medicinal plant Juniperus procera in vitro. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 962112.

- Kumar, D.; Salvi, A.; Thakur, V.; Kharbanda, S.; Sangwan, S.; Thakur, P.; Thakur, A. Aloe vera assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: structural characterization, electrochemical behaviour, and antimicrobial efficiency. Discov. appl. sci. 2025, 7, 530.

- Modrzejewska-Sikorska, A.; Konował, E. Silver and gold nanoparticles as chemical probes of the presence of heavy metal ions. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 302, 112559.

- Awaly, S.B.; Osman, N.H.; Farag, H.M.; Yacoub, I.H.; Mahmoud-Aly, M.; Elarabi, N.I.E.; Ahmed, D.S. Evaluation of the morpho-physiological traits and the genetic diversity of durum wheat’s salt tolerance induced by silver nanoparticles. J. agric. environ. int. dev. 2023, 117, 161-184.

- Dubey, R.K.; Shukla, S.; Hussain, Z. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles; A sustainable approach with diverse applications. Zhongguo Ying Yong Sheng Li Xue Za Zhi 2023, 39, e20230007.

- Anjana, V.; Joseph, M.; Francis, S.; Joseph, A.; Koshy, E.P.; Mathew, B. Microwave assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles for optical, catalytic, biological and electrochemical applications. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2021, 49, 438-449.

- Fahim, M.; Shahzaib, A.; Nishat, N.; Jahan, A.; Bhat, T.A.; Inam, A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: A comprehensive review of methods, influencing factors, and applications. JCIS Open 2024, 16, 100125.

- Hussain, I.; Singh, N.; Singh, A.; Singh, H.; Singh, S. Green synthesis of nanoparticles and its potential application. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 545-560.

- Haridas, E.; Varma, M.; Chandra, G.K. Bioactive silver nanoparticles derived from Carica papaya floral extract and its dual-functioning biomedical application. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1-14.

- Aminnezhad, S.; Zonobian, M.A.; Moradi Douki, M.; Mohammadi, M.R.; Azarakhsh, Y. Curcumin and their derivatives with anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, anticancer, and antimicrobial activities: a review. Micro Nano Bio Asp. 2023, 2, 25-34.

- Stanoiu, A.-M.; Bejenaru, C.; Segneanu, A.-E.; Vlase, G.; Bradu, I.A.; Vlase, T.; Mogoşanu, G.D.; Ciocîlteu, M.V.; Biţă, A.; Kostici, R. Design and Evaluation of a Inonotus obliquus–AgNP–Maltodextrin Delivery System: Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitory and Cytotoxic Potential. Polymers 2025, 17, 2163.

- Yadav, S.; Kumari, P.; Mahto, S.K. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Momordica dioica leaf extract: characterizing antibacterial, antibiofilm, and catalytic activities. Transit. Met. Chem. 2025, 1-18.

- Mohanaparameswari, S.; Balachandramohan, M.; Kumar, K.G.; Revathy, M.; Sasikumar, P.; Rajeevgandhi, C.; Vimalan, M.; Pugazhendhi, S.; Batoo, K.M.; Hussain, S. Green synthesis of silver oxide nanoparticles using Plectranthus amboinicus and Solanum trilobatum extracts as an Eco-friendly approach: characterization and antibacterial properties. J Inorg Organomet Polym 2024, 34, 3191-3211.

- Leyva-Porras, C.; Cruz-Alcantar, P.; Espinosa-Solís, V.; Martínez-Guerra, E.; Piñón-Balderrama, C.I.; Compean Martínez, I.; Saavedra-Leos, M.Z. Application of differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and modulated differential scanning calorimetry (MDSC) in food and drug industries. Polymers 2019, 12, 5.

- Agnihotri, S.; Mukherji, S.; Mukherji, S. Size-controlled silver nanoparticles synthesized over the range 5–100 nm using the same protocol and their antibacterial efficacy. Rsc Adv 2014, 4, 3974-3983.

- Karuna, D.; Dey, P.; Das, S.; Kundu, A.; Bhakta, T. In vitro antioxidant activities of root extract of Asparagus racemosus Linn. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2018, 8, 60-65.

- Rajeshkumar, S.; Bharath, L. Mechanism of plant-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles–a review on biomolecules involved, characterisation and antibacterial activity. Chem Biol Interact 2017, 273, 219-227.

- El Badawy, A.M.; Silva, R.G.; Morris, B.; Scheckel, K.G.; Suidan, M.T.; Tolaymat, T.M. Surface charge-dependent toxicity of silver nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 283-287.

- Shayo, G.M.; Elimbinzi, E.; Shao, G.N. Preparation methods, applications, toxicity and mechanisms of silver nanoparticles as bactericidal agent and superiority of green synthesis method. Heliyon 2024, 10.

- Tippayawat, P.; Phromviyo, N.; Boueroy, P.; Chompoosor, A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles in aloe vera plant extract prepared by a hydrothermal method and their synergistic antibacterial activity. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2589.

- Vélez, E.; Campillo, G.; Morales, G.; Hincapié, C.; Osorio, J.; Arnache, O. Silver nanoparticles obtained by aqueous or ethanolic aloe Vera extracts: An assessment of the antibacterial activity and mercury removal capability. J. Nanomater. 2018, 2018, 7215210.

- Haripriya, S.; Ajitha, P. Antimicrobial efficacy of silver nanoparticles of Aloe vera. 2017.

- Urnukhsaikhan, E.; Bold, B.-E.; Gunbileg, A.; Sukhbaatar, N.; Mishig-Ochir, T. Antibacterial activity and characteristics of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized from Carduus crispus. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21047.

- Ojha, S.; Sett, A.; Bora, U. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Ricinus communis var. carmencita leaf extract and its antibacterial study. Adv. Nat. Sci.:Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 8, 035009.

- Kitchen, S.; Gray, E.; Mackie, I.; Baglin, T.; Makris, M. Measurement of non-coumarin anticoagulants and their effects on tests of Haemostasis: Guidance from the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 166.

- Shrivastava, S.; Bera, T.; Singh, S.K.; Singh, G.; Ramachandrarao, P.; Dash, D. Characterization of antiplatelet properties of silver nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 1357-1364.

- Rodrigues, A.S.; Batista, J.G.; Rodrigues, M.Á.; Thipe, V.C.; Minarini, L.A.; Lopes, P.S.; Lugão, A.B. Advances in silver nanoparticles: a comprehensive review on their potential as antimicrobial agents and their mechanisms of action elucidated by proteomics. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1440065.

- Do, H.T.T.; Nguyen, N.P.U.; Saeed, S.I.; Dang, N.T.; Doan, L.; Nguyen, T.T.H. Advances in silver nanoparticles: unraveling biological activities, mechanisms of action, and toxicity. Appl. Nanosci. 2025, 15, 1.

- Ibrahim, A.T.A. Toxicological impact of green synthesized silver nanoparticles and protective role of different selenium type on Oreochromis niloticus: hematological and biochemical response. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 61, 126507.

- Nemudzivhadi, V.; Masoko, P. In vitro assessment of cytotoxicity, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities of Ricinus communis (Euphorbiaceae) leaf extracts. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014, 2014, 625961.

- Valderramas, A.C.; Moura, S.H.P.; Couto, M.; Pasetto, S.; Chierice, G.O.; Guimarães, S.A.C.; Zurron, A.C.B.d.P. Antiinflammatory activity of Ricinus communis derived polymer. 2009.

- Varghese, R.M.; Kumar, A.; Shanmugam, R. Comparative anti-inflammatory activity of silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using Ocimum tenuiflorum and Ocimum gratissimum herbal formulations. Cureus 2024, 16.

- Khashan, A.A.; Dawood, Y.; Khalaf, Y.H. Green chemistry and anti-inflammatory activity of silver nanoparticles using an aqueous curcumin extract. Results Chem. 2023, 5, 100913.

- Dharmadeva, S.; Galgamuwa, L.S.; Prasadinie, C.; Kumarasinghe, N. In vitro anti-inflammatory activity of Ficus racemosa L. bark using albumin denaturation method. Ayu 2018, 39, 239-242.

- Matkowski, A.; Tasarz, P.; Szypuła, E. Antioxidant activity of herb extracts from five medicinal plants from Lamiaceae, subfamily Lamioideae. J. Med. Plants Res. 2008, 2, 321-330.

- Silva, F.; Veiga, F.; Cardoso, C.; Dias, F.; Cerqueira, F.; Medeiros, R.; Paiva-Santos, A.C. A rapid and simplified DPPH assay for analysis of antioxidant interactions in binary combinations. Microchem. J. 2024, 202, 110801.

- Sohal, J.K.; Saraf, A.; Shukla, K.; Shrivastava, M. Determination of antioxidant potential of biochemically synthesized silver nanoparticles using Aloe vera gel extract. Plant Sci. Today 2019, 6, 208-217.

- More, G.K.; Makola, R.T. In-vitro analysis of free radical scavenging activities and suppression of LPS-induced ROS production in macrophage cells by Solanum sisymbriifolium extracts. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6493.

- Rana, M.S.; Rayhan, N.M.A.; Emon, M.S.H.; Islam, M.T.; Rathry, K.; Hasan, M.M.; Mansur, M.M.I.; Srijon, B.C.; Islam, M.S.; Ray, A. Antioxidant activity of Schiff base ligands using the DPPH scavenging assay: an updated review. RSC Adv 2024, 14, 33094-33123.

- He, W.; Zhou, Y.-T.; Wamer, W.G.; Boudreau, M.D.; Yin, J.-J. Mechanisms of the pH dependent generation of hydroxyl radicals and oxygen induced by Ag nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 7547-7555.

- Mata, R.; Nakkala, J.R.; Sadras, S.R. Biogenic silver nanoparticles from Abutilon indicum: their antioxidant, antibacterial and cytotoxic effects in vitro. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2015, 128, 276-286.

- Irfan, A.; Jardan, Y.A.B.; Rubab, L.; Hameed, H.; Zahoor, A.F.; Supuran, C.T. Bacterial tyrosinases and their inhibitors. Enzymes 2024, 56, 231-260.

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Biswas, R.; Sharma, A.; Banerjee, S.; Biswas, S.; Katiyar, C. Validation of medicinal herbs for anti-tyrosinase potential. J Herb Med 2018, 14, 1-16.

- Özer, Ö.; Mutlu, B.; Kıvçak, B. Antityrosinase activity of some plant extracts and formulations containing ellagic acid. Pharm Biol 2007, 45, 519-524.

- Manickam, V.; Mani, G.; Muthuvel, R.; Pushparaj, H.; Jayabalan, J.; Pandit, S.S.; Elumalai, S.; Kaliappan, K.; Tae, J.H. Green fabrication of silver nanoparticles and it’s in vitro anti-bacterial, anti-biofilm, free radical scavenging and mushroom tyrosinase efficacy evaluation. Inorg Chem Commun 2024, 162, 112199.

- Verma, S.K.; Jha, E.; Sahoo, B.; Panda, P.K.; Thirumurugan, A.; Parashar, S.; Suar, M. Mechanistic insight into the rapid one-step facile biofabrication of antibacterial silver nanoparticles from bacterial release and their biogenicity and concentration-dependent in vitro cytotoxicity to colon cells. RSC Adv 2017, 7, 40034-40045.

- Akter, M.; Sikder, M.T.; Rahman, M.M.; Ullah, A.A.; Hossain, K.F.B.; Banik, S.; Hosokawa, T.; Saito, T.; Kurasaki, M. A systematic review on silver nanoparticles-induced cytotoxicity: Physicochemical properties and perspectives. J Adv Res 2018, 9, 1-16.

- Sati, A.; Mali, S.N.; Ranade, T.N.; Yadav, S.; Pratap, A. Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) as a Double-Edged Sword: Synthesis, Factors Affecting, Mechanisms of Toxicity and Anticancer Potentials—An Updated Review till March 2025. Biol Trace Elem Res 2025, 1-52.

- Garrido, C.; Galluzzi, L.; Brunet, M.; Puig, P.; Didelot, C.; Kroemer, G. Mechanisms of cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Cell Death Differ 2006, 13, 1423-1433.

- Abbas, M.; Ali, A.; Arshad, M.; Atta, A.; Mehmood, Z.; Tahir, I.M.; Iqbal, M. Mutagenicity, cytotoxic and antioxidant activities of Ricinus communis different parts. Chem Cent J 2018, 12, 3.

- Erhabor, J.O.; Idu, M. In vitro antibacterial, antioxidant, cytogenotoxic and nutritional value of Aloe barbadensis Mill.(Asphodelaceae). 2020.

| Phytochemicals | Aqueous extract | Methanolic extract | ||

| Ricinus communis | Aloe barbadensis | Ricinus communis | Aloe barbadensis | |

| Alkaloids | - | + | + | + |

| Steroids | - | - | + | + |

| Flavonoids | + | + | + | + |

| Terpenoids | + | - | + | + |

| Glycosides | + | - | - | - |

| Phenols | - | + | + | + |

| Tannins | + | + | + | - |

| Saponins | + | - | + | + |

| Reducing sugars | + | + | + | + |

| Microorganisms | RcSNPs |

AbSNPs |

Standard | Control | |||||

| 50 μL | 100 μL | 50 μL | 100 μL | Gentamycin | Fluconazole | Rc extract | Ab extract | ||

| Bacteria | S. aureus | 18.32±0.34 | 20.2±0.23 | 17.2±0.082 | 20.3±0.051 | 25.2±0.34 | - | 12.3±0.42 | 10.4±0.45 |

| S. typhi | 18.1±0.72 | 19.3±0.52 | 14.5±0.067 | 18.6±0.070 | 27.8±0.54 | - | 14.6±0.36 | 8.6±0.58 | |

| E. coli | 17.6±0.93 | 18.4±0.65 | 16.1±0.047 | 17.3±0.049 | 23.4±0.65 | - | 11.2±0.71 | 11.7±0.32 | |

|

Fungi |

C. albicans | 20.1±0.65 | 22.3±0.75 | 17.25±0.25 | 20.5±0.54 | - | 22.8±0.74 | 10.7±0.93 | 13.6±0.15 |

| A. niger | 19.4±0.67 | 21.4±0.70 | 22.5±0.32 | 24.3±0.43 | - | 23.21±0.75 | 9.8±0.23 | 17.1±0.75 | |

| Testing material | Tyrosinase inhibition (%) |

| RcSNPs | 96.77±1.09 |

| AbSNPs | 97.72±0.75 |

| Ascorbic acid | 99.23± 0.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).