Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Scabiosa palaestina Ethanolic Extract (SPE)

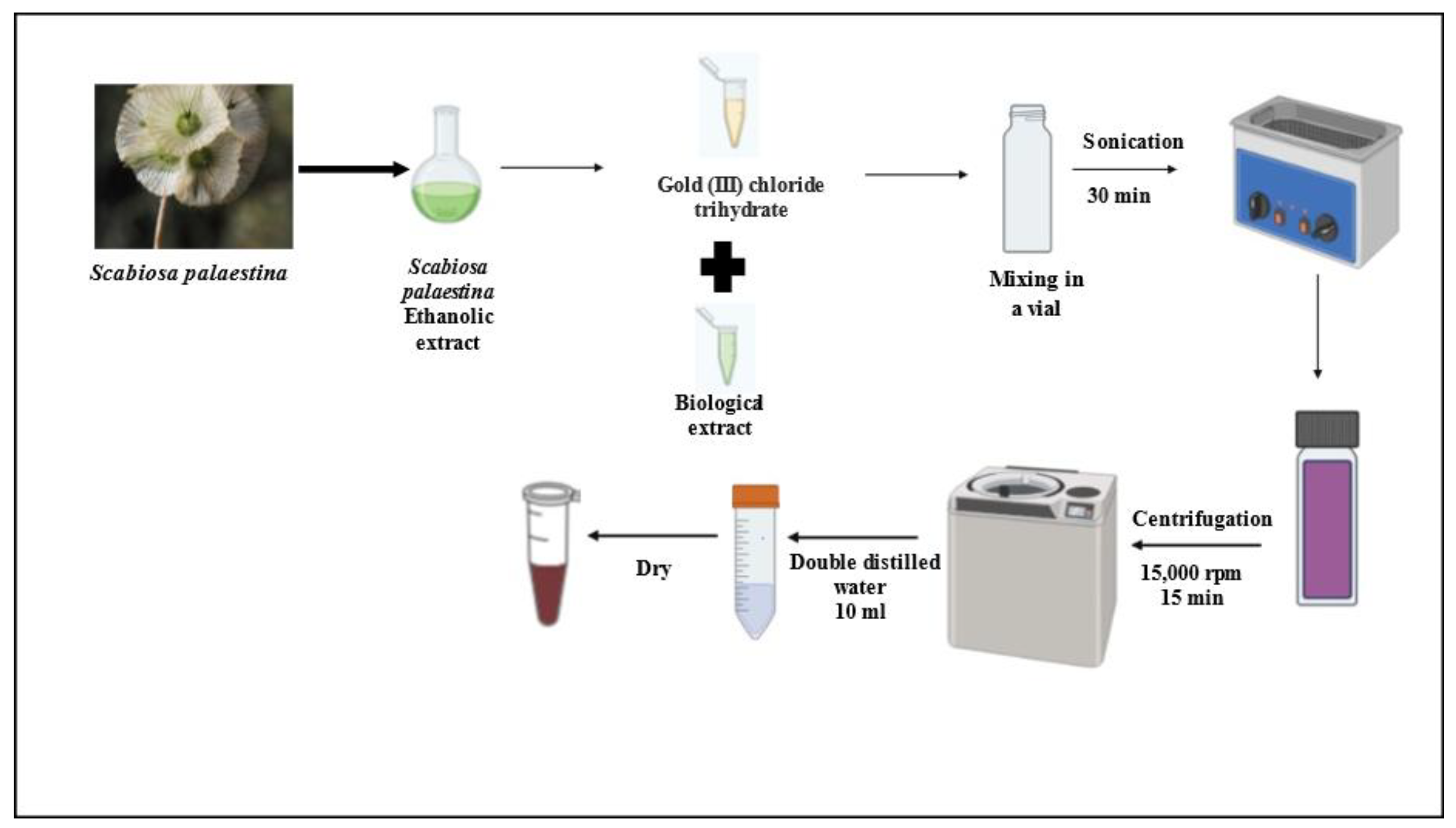

2.2. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using SPE

2.3. Characterization of AuNPs

2.4. Cell Culture

2.5. MTT Cell Viability Assay

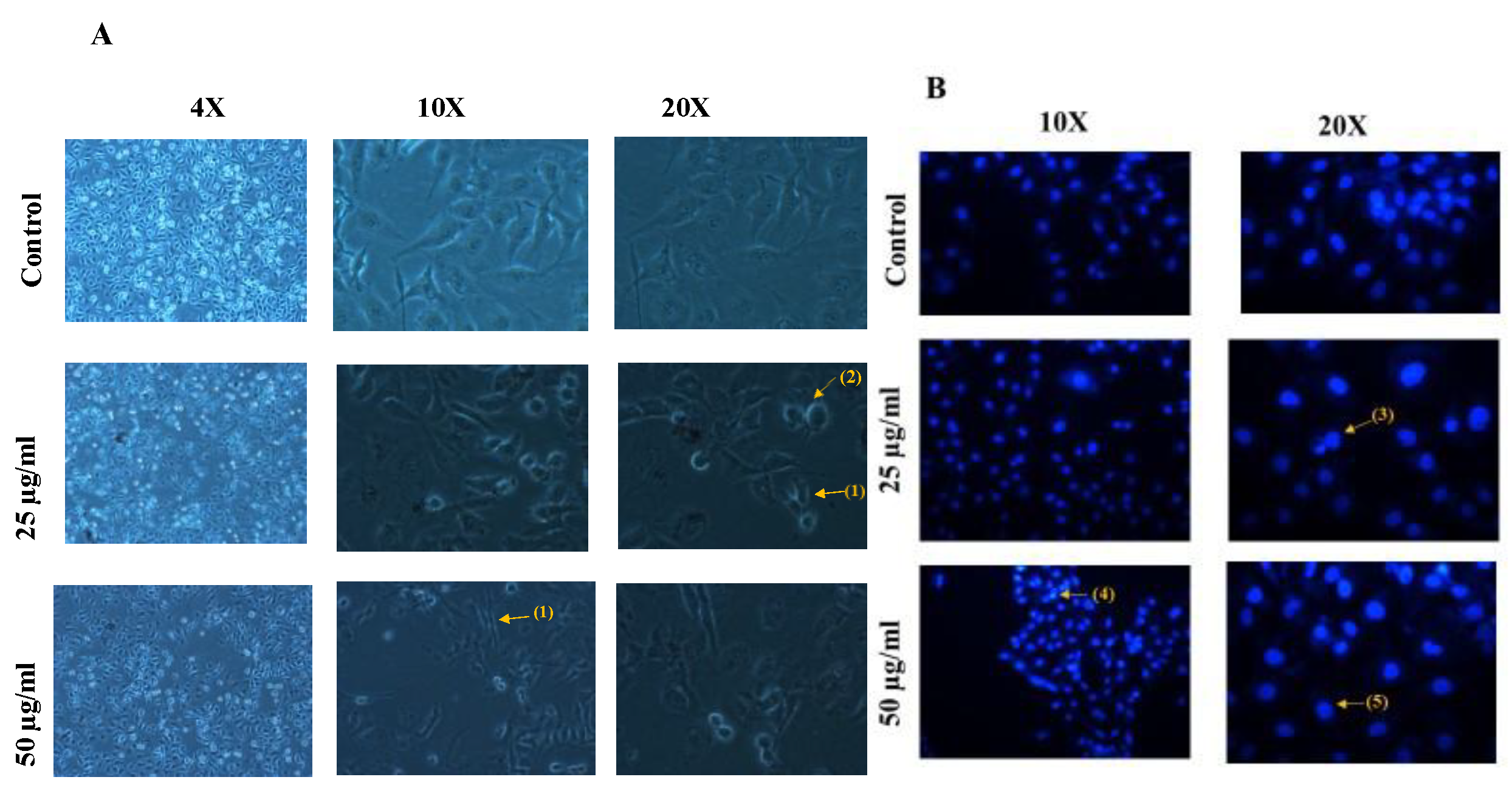

2.6. Microscopic Analysis of Apoptotic Morphological Changes

2.7. Antioxidant Activity

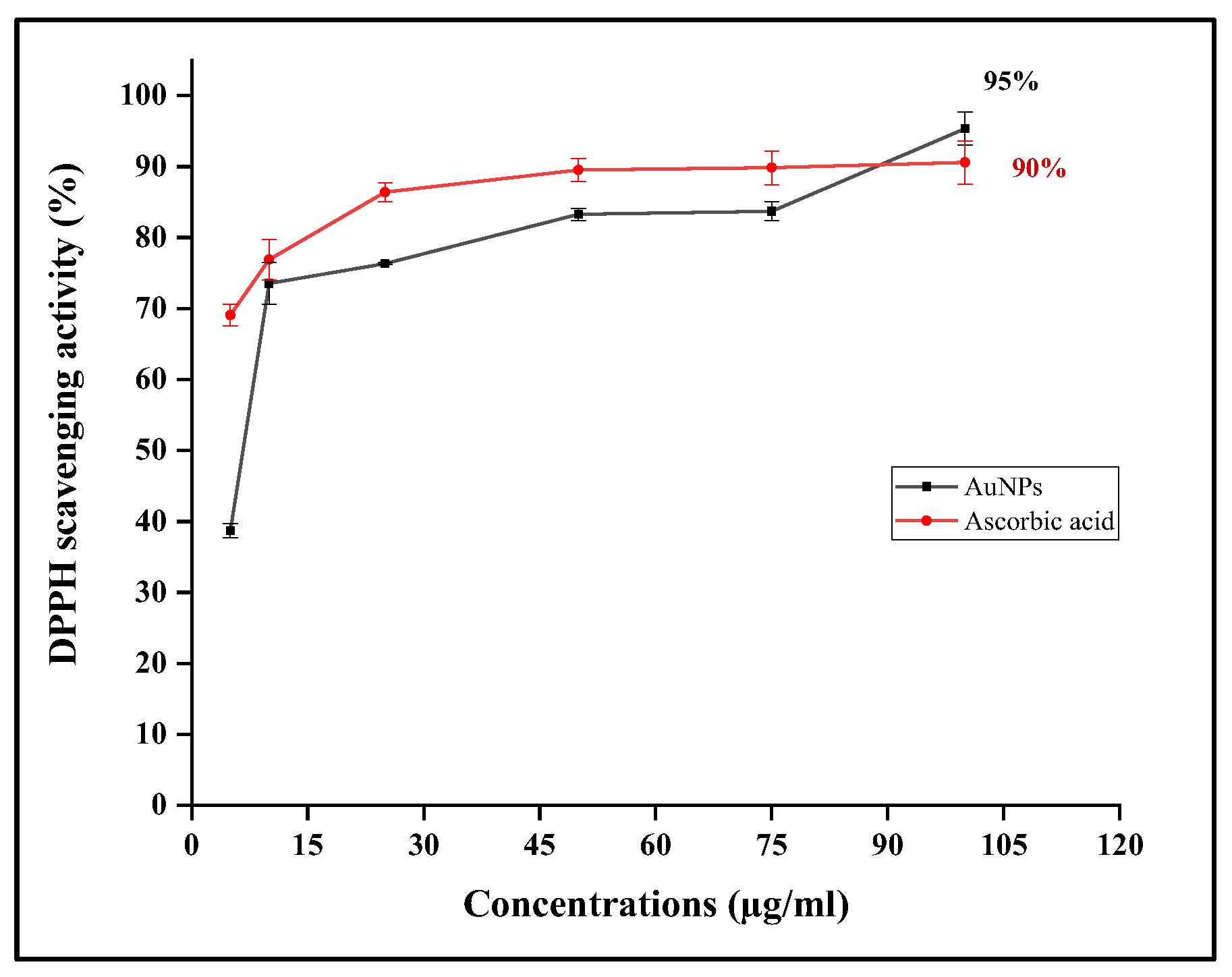

2.7.1. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Assay

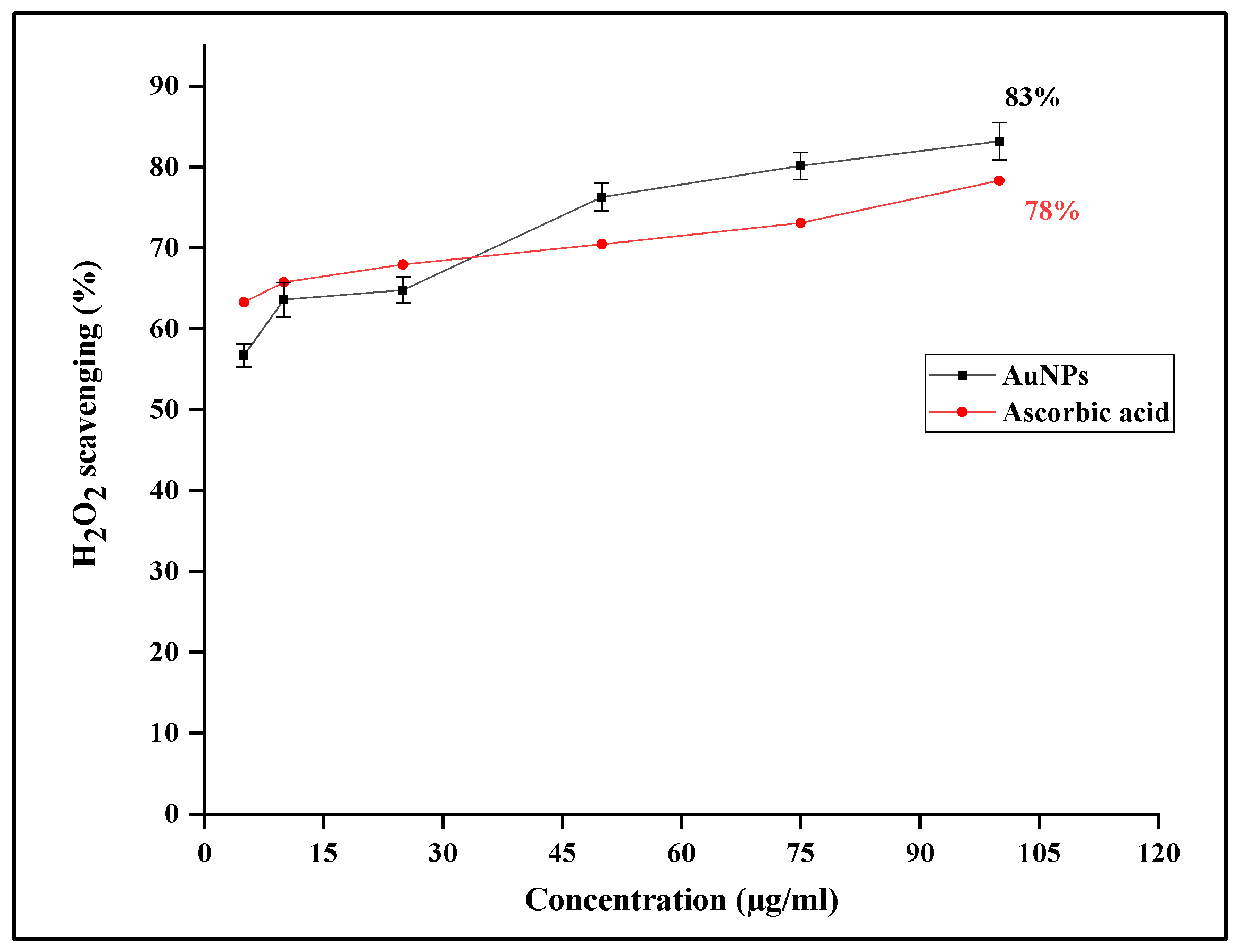

2.7.2. Hydrogen Peroxide Radical Scavenging (H2O2) Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

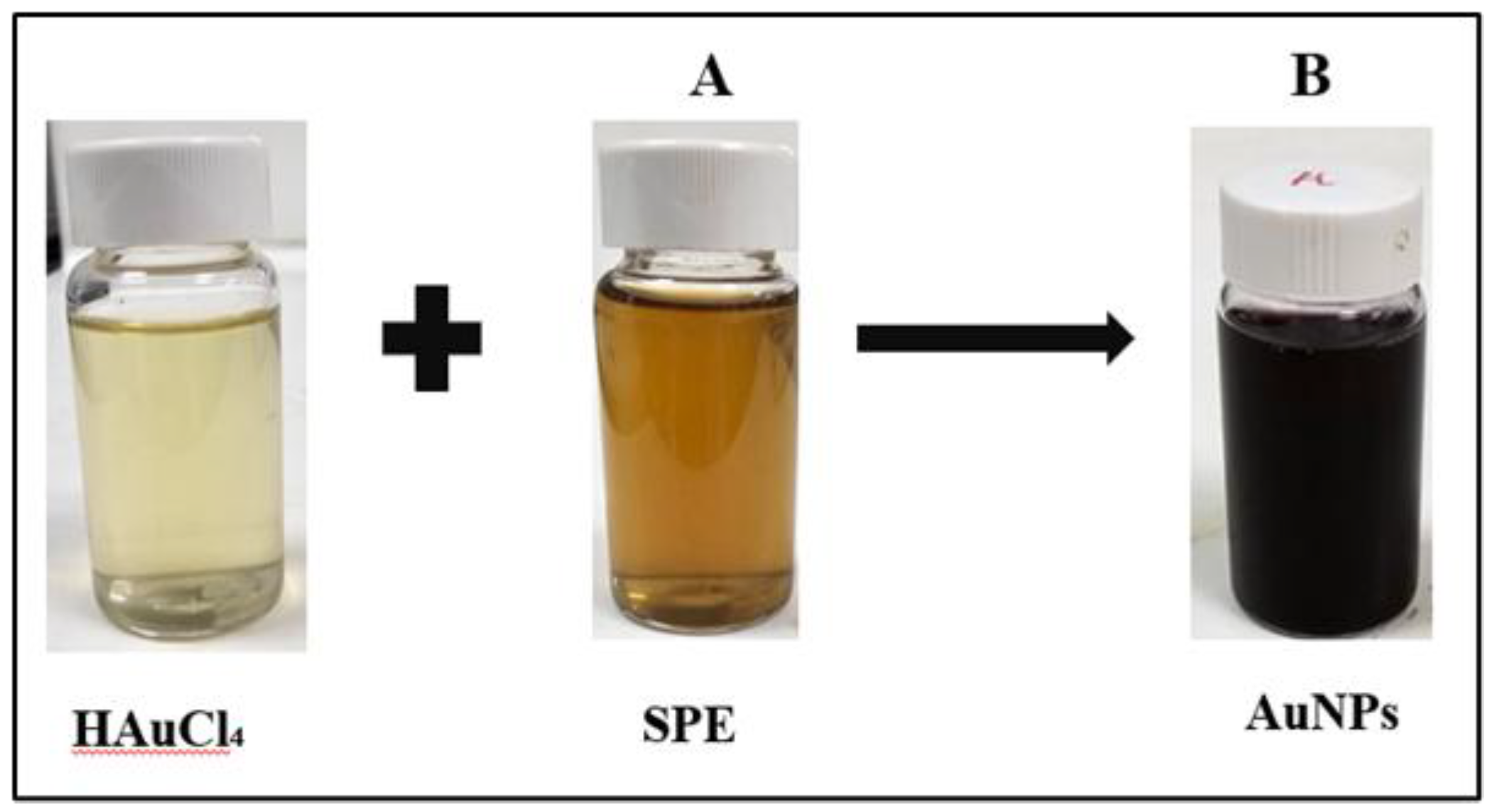

3.1. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using SPE

3.2. Characterization of Biosynthesized AuNPs

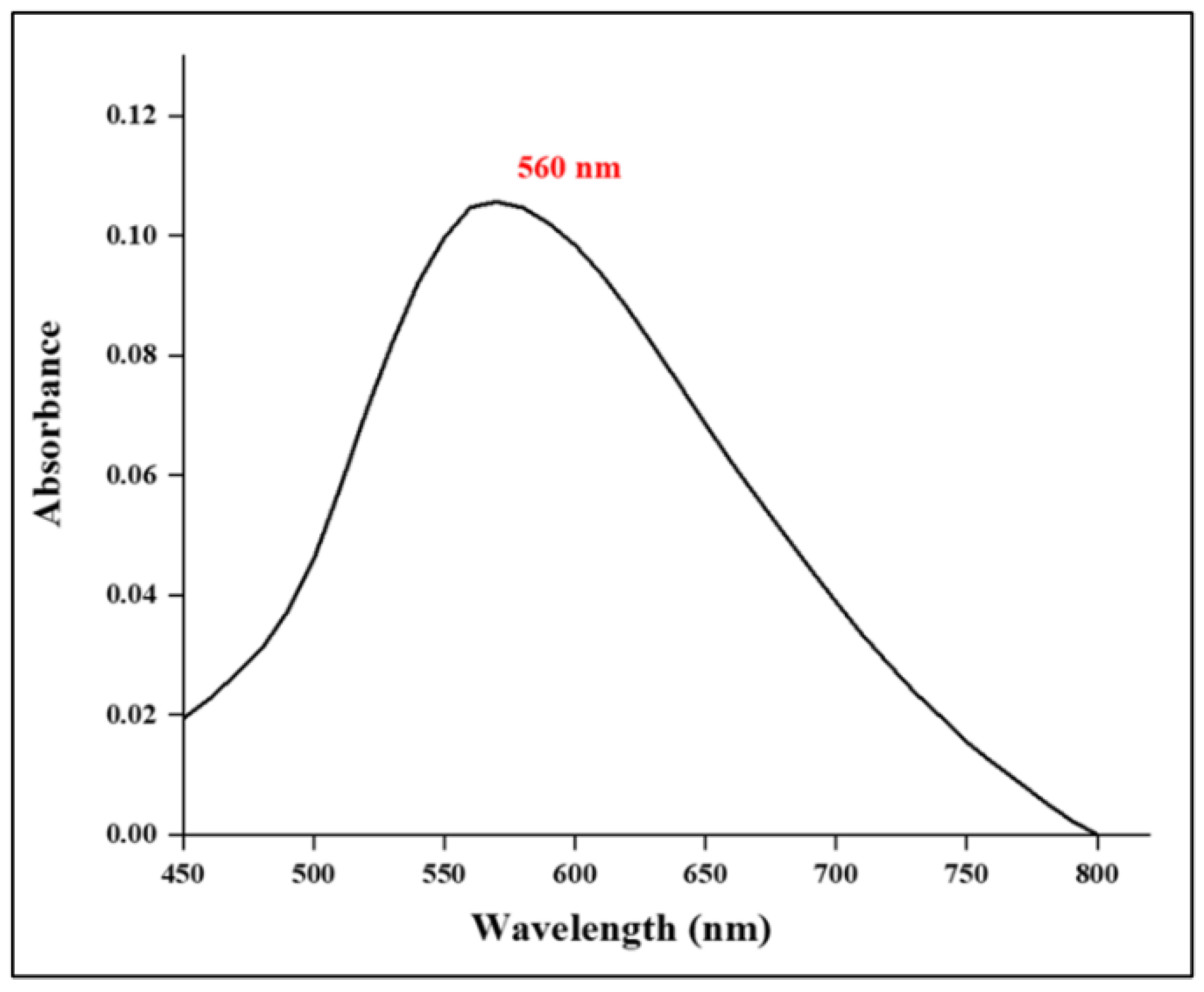

3.2.1. UV- Vis Spectrometry

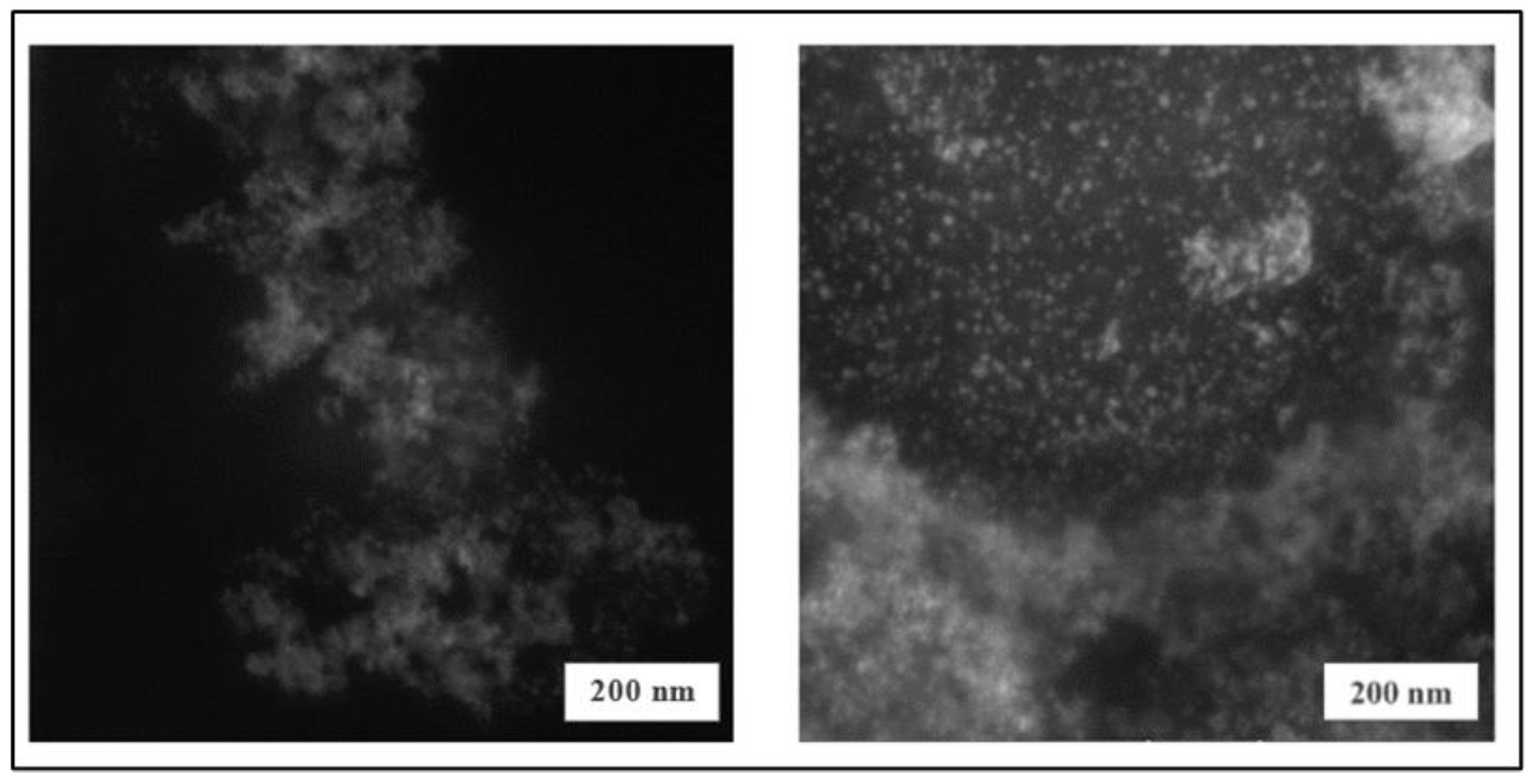

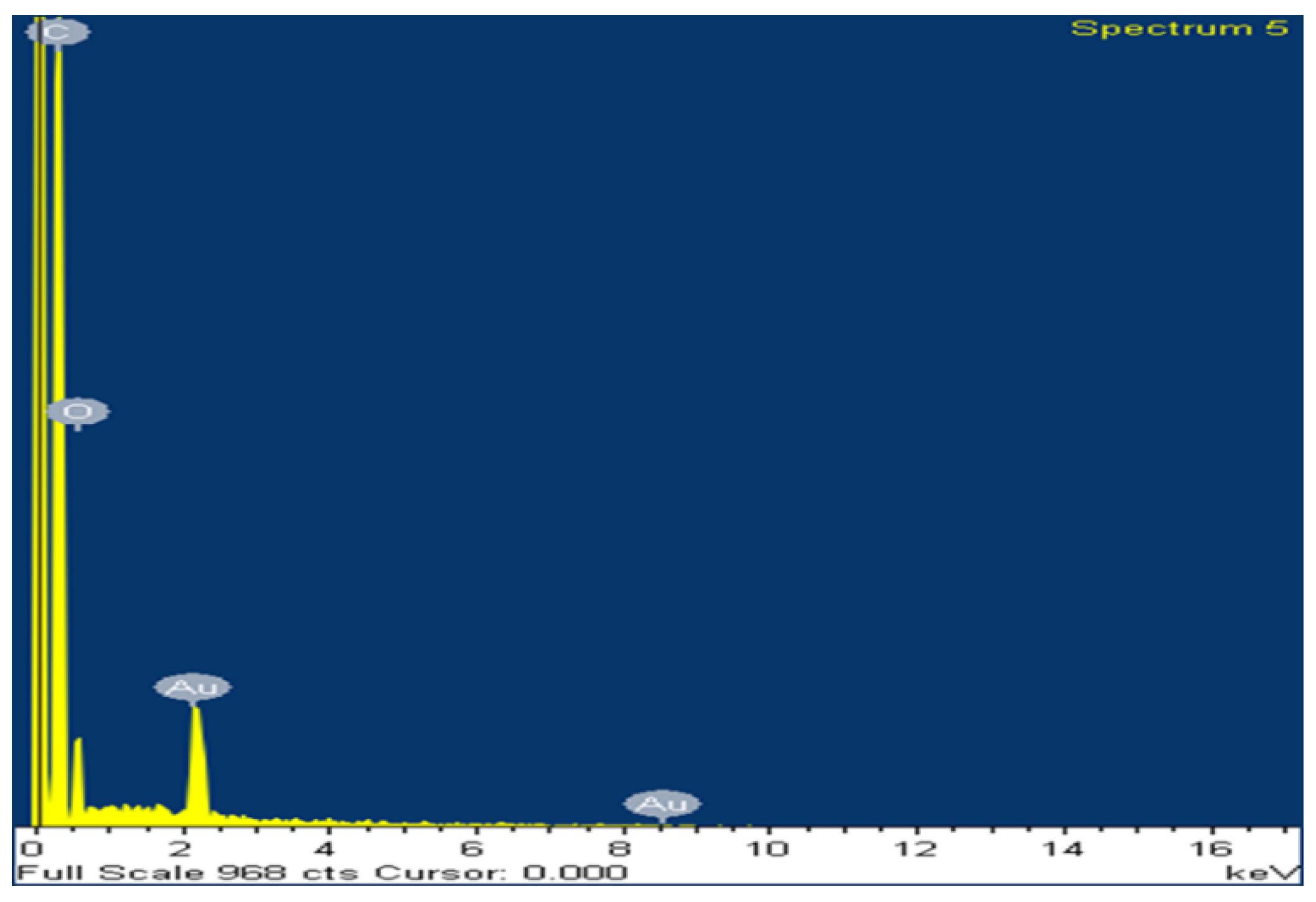

3.2.2. Morphological and Elemental Analysis – SEM and EDX

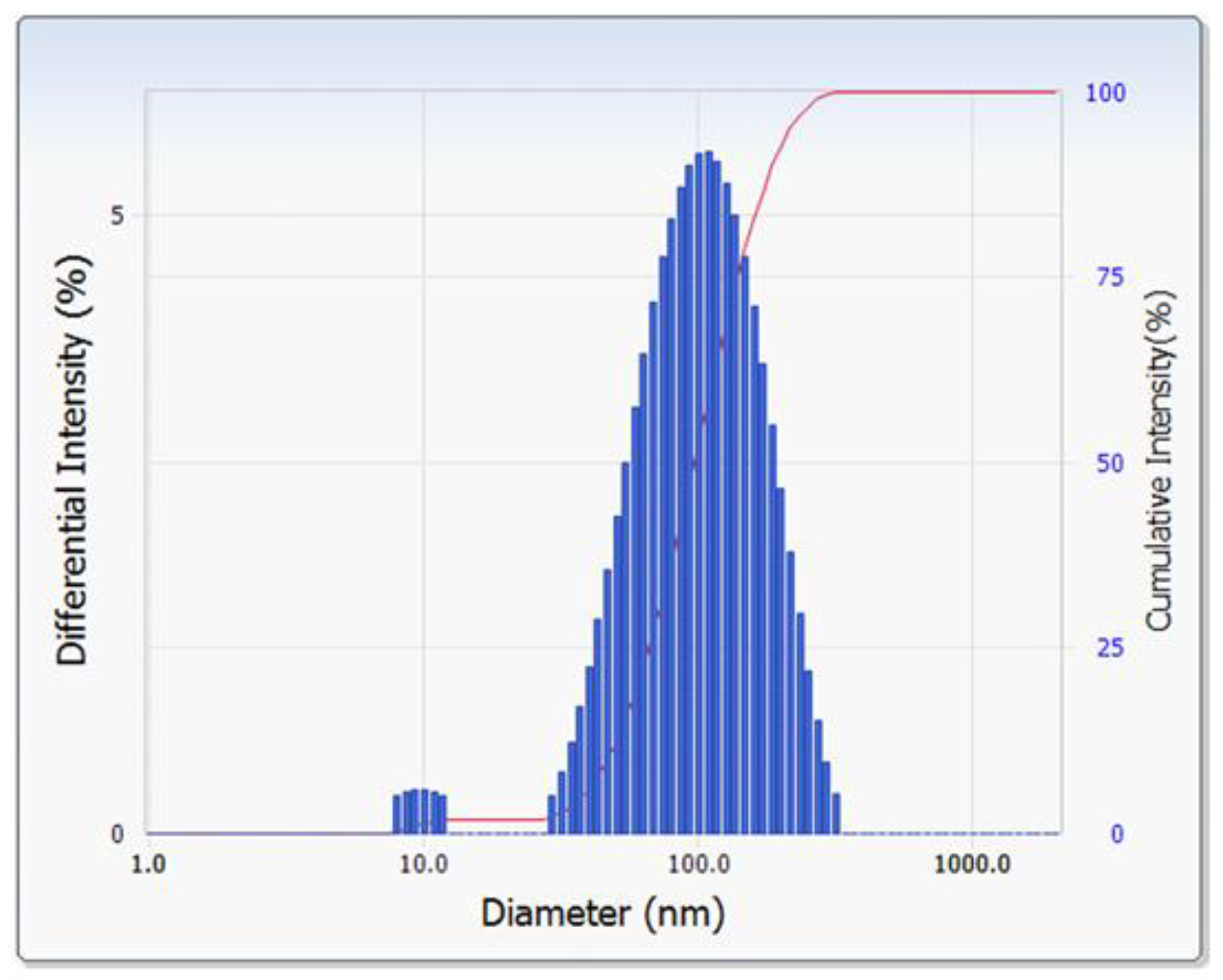

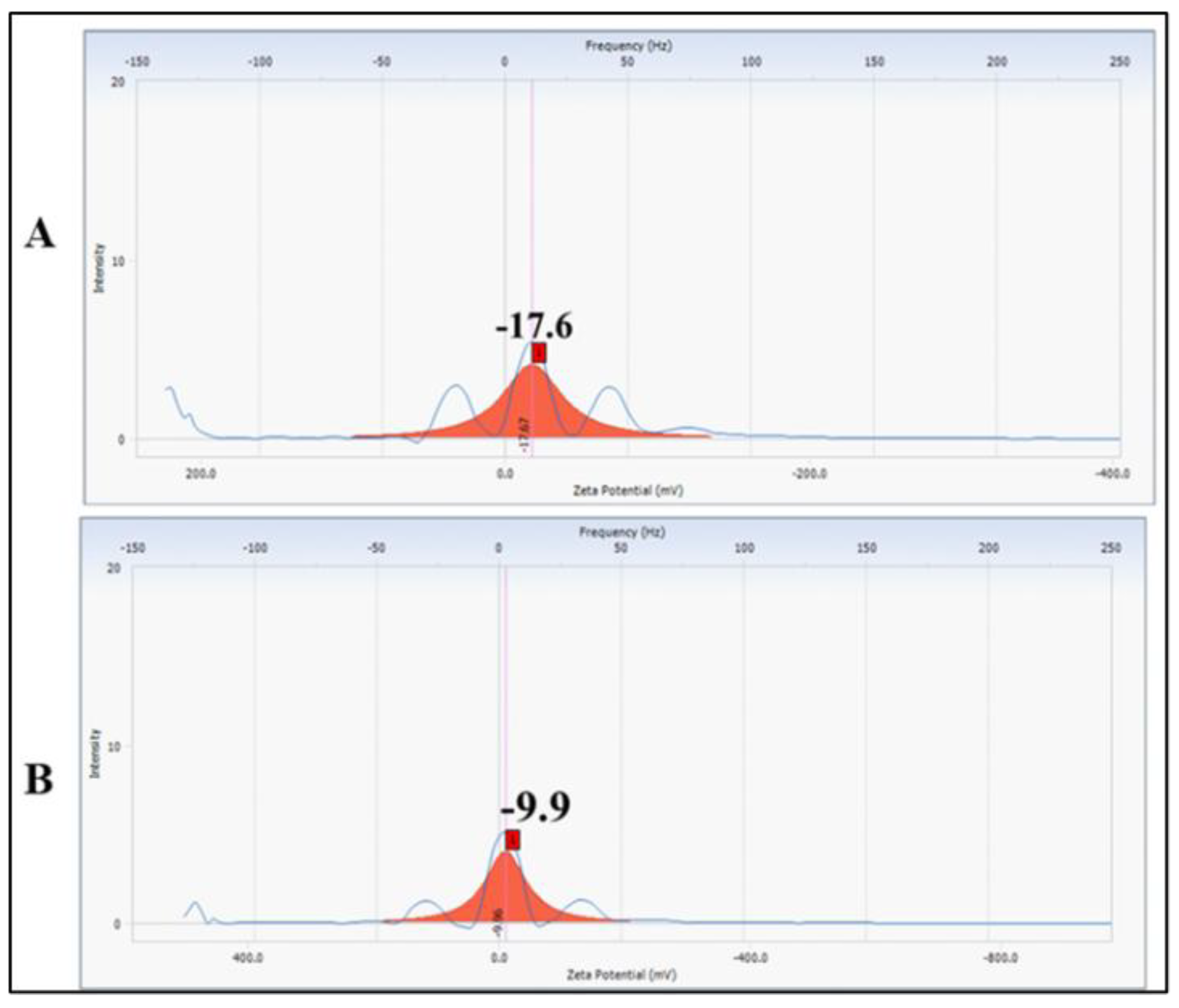

3.2.3. Particle Size and Zeta Potential

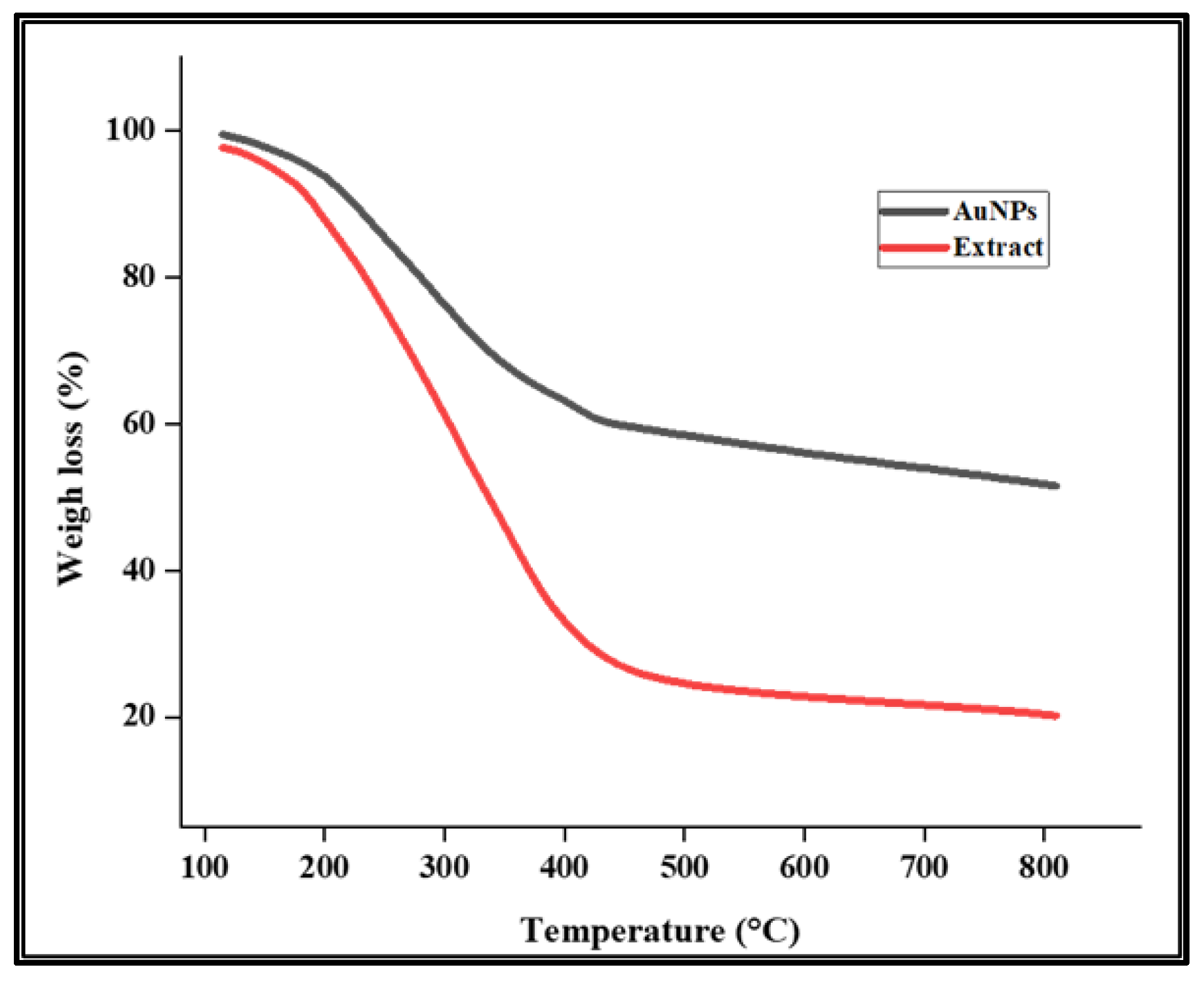

3.2.4. TGA Analysis

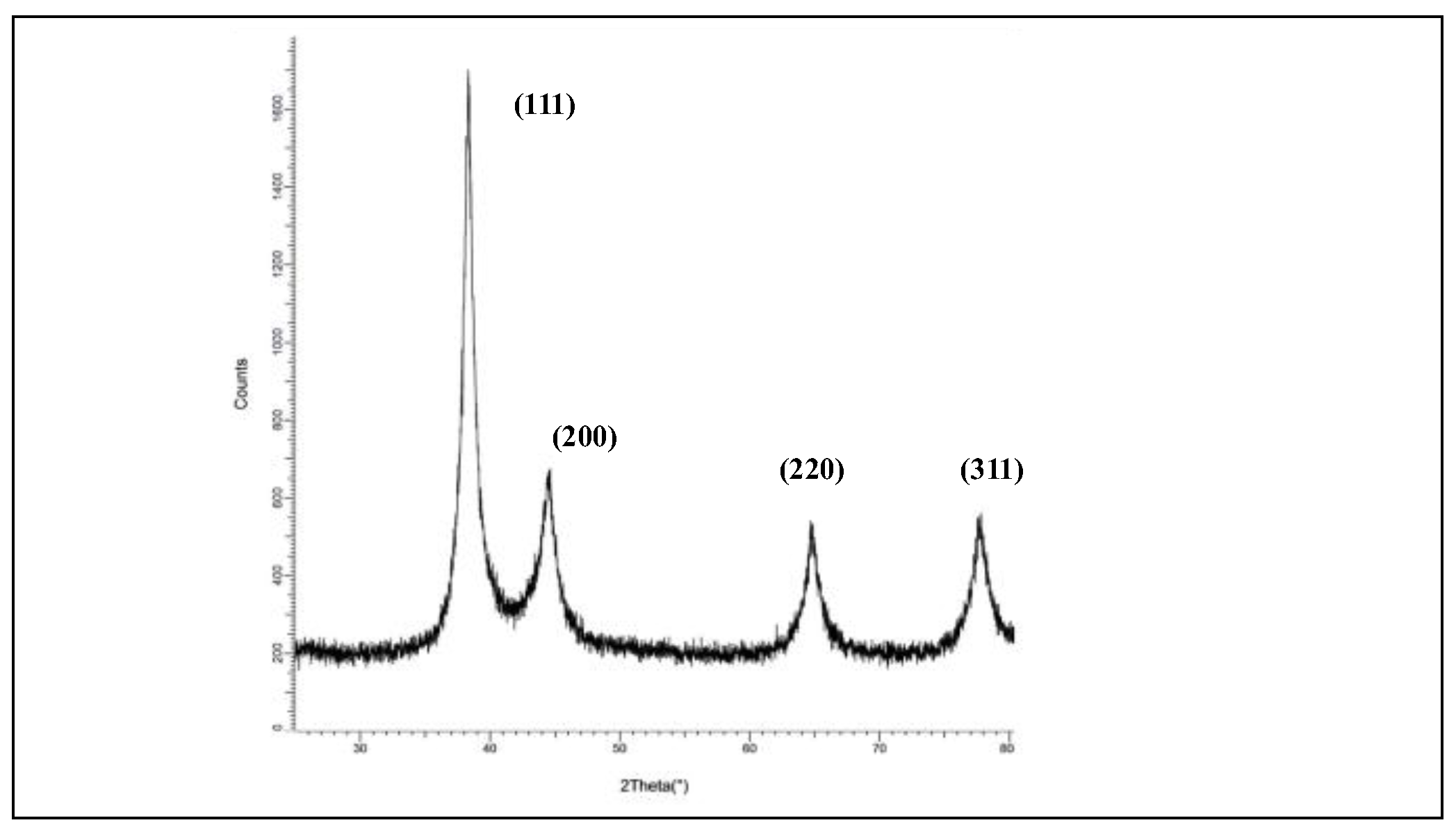

3.2.5. Crystallinity Characterization

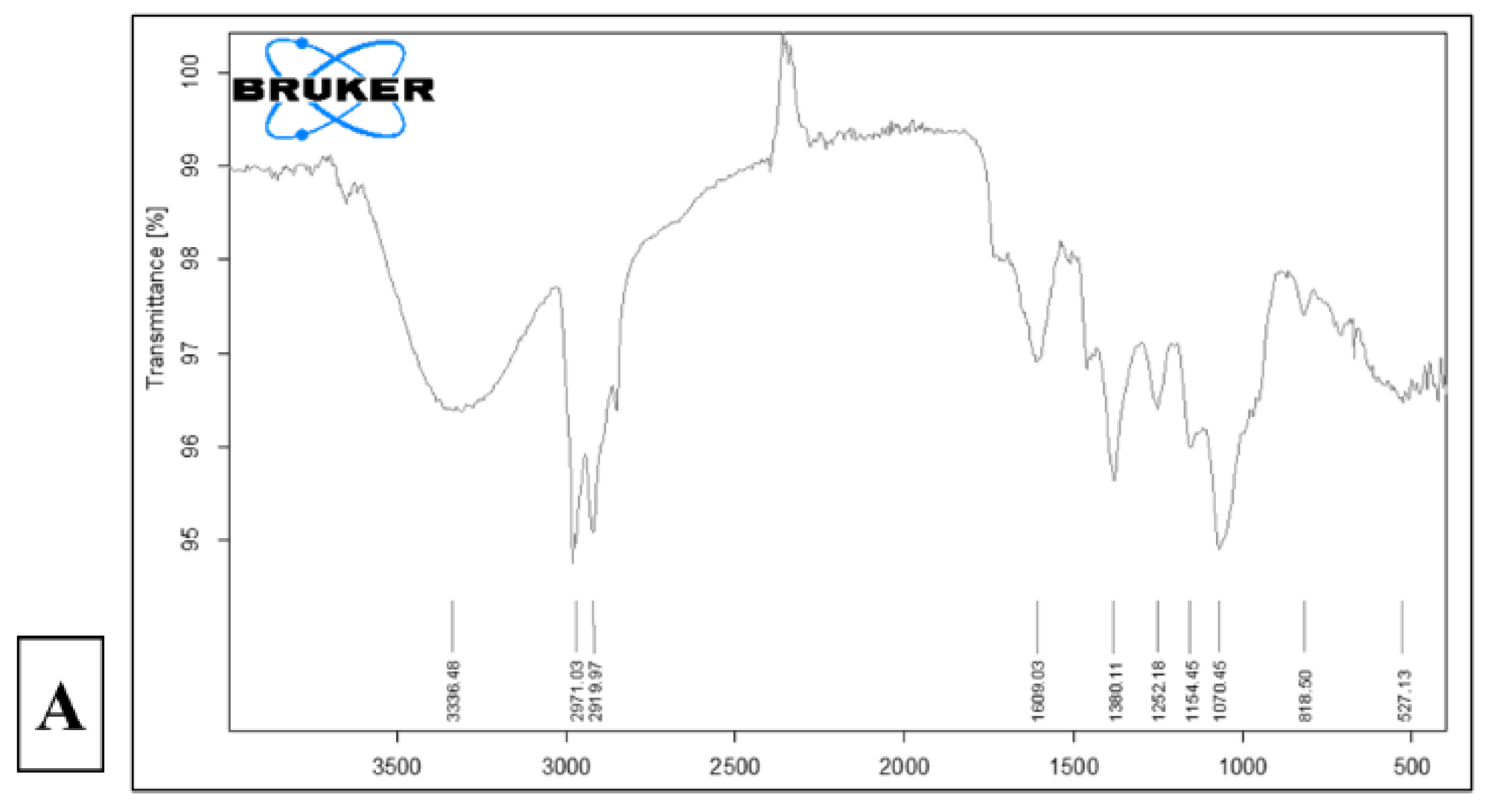

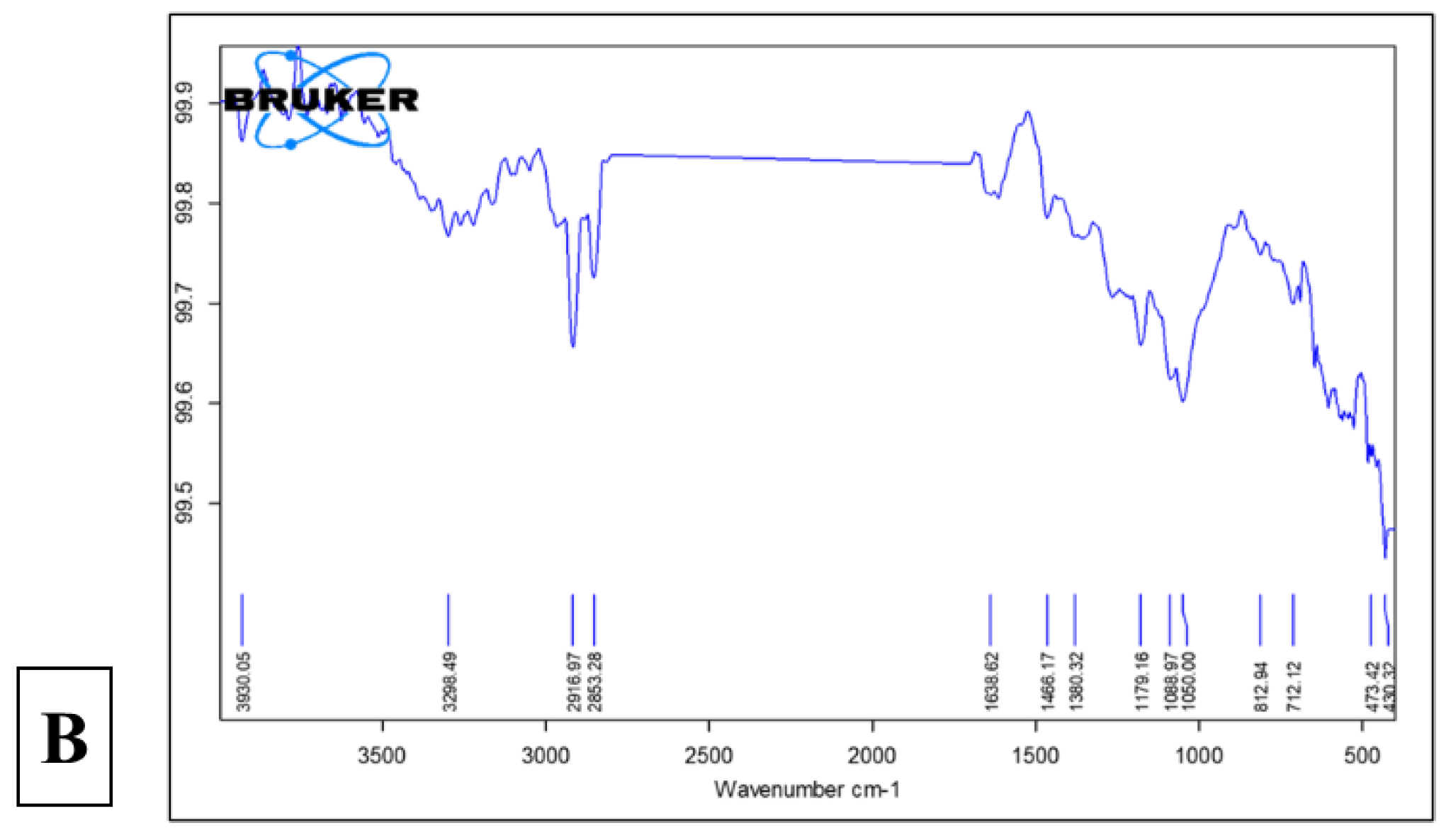

3.2.6. FTIR Analysis

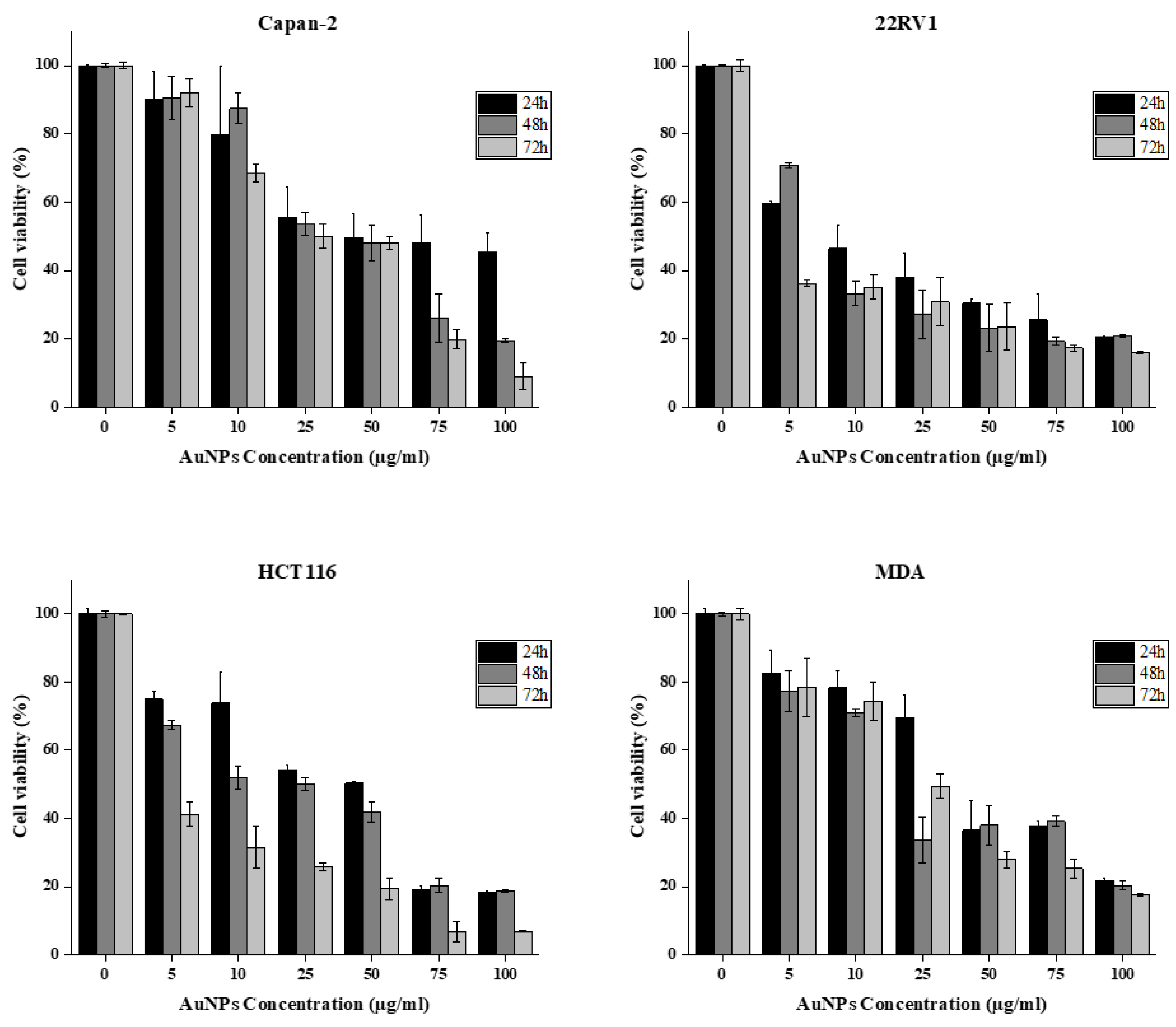

3.3. Anticancer Activity of Biosynthesized AuNPs

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

3.4.1. DPPH Assay

3.4.2. H2O2 assay

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Venkatraman, G.; Ramya; Shruthilaya; Akila; Ganga; Kumar, S.; Yoganathan; Santosham, R.; Ponraju. Nanomedicine: Towards Development of Patient-Friendly Drug-Delivery Systems for Oncological Applications. IJN 2012, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botteon, C.E.A.; Silva, L.B.; Ccana-Ccapatinta, G.V.; Silva, T.S.; Ambrosio, S.R.; Veneziani, R.C.S.; Bastos, J.K.; Marcato, P.D. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Gold Nanoparticles Using Brazilian Red Propolis and Evaluation of Its Antimicrobial and Anticancer Activities. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, K.; Nazir, S.; Li, B.; Khan, A.U.; Khan, Z.U.H.; Gong, P.Y.; Khan, S.U.; Ahmad, A. Nerium Oleander Leaves Extract Mediated Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles and Its Antioxidant Activity. Materials Letters 2015, 156, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badeggi, U.; Ismail, E.; Adeloye, A.; Botha, S.; Badmus, J.; Marnewick, J.; Cupido, C.; Hussein, A. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Capped with Procyanidins from Leucosidea Sericea as Potential Antidiabetic and Antioxidant Agents. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.; Badwaik, V.; Waghwani, H.K.; Moolani, H.; Tockstein, S.; Thompson, D.; Dakshinamurthy, R. Development of Dihydrochalcone-Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles for Augmented Antineoplastic Activity. IJN 2018, 13, 1917–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; El-Sayed, M.A. Gold Nanoparticles: Optical Properties and Implementations in Cancer Diagnosis and Photothermal Therapy. Journal of Advanced Research 2010, 1, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, A.; Eid, A.M.; Guibal, E.; Hamza, M.F.; Hassan, S.E.-D.; Alkhalifah, D.H.M.; El-Hossary, D. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles by Aqueous Extract of Zingiber Officinale: Characterization and Insight into Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and In Vitro Cytotoxic Activities. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 12879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Wang, D.; Li, Y. Green Chemistry for Nanoparticle Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 5778–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amina, S.J.; Guo, B. A Review on the Synthesis and Functionalization of Gold Nanoparticles as a Drug Delivery Vehicle. IJN 2020, Volume 15, 9823–9857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, D.; El Kurdi, R. Curcumin as a Novel Reducing and Stabilizing Agent for the Green Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles. Green Chemistry Letters and Reviews 2021, 14, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Rahmouni, N.; Beghidja, N.; Silva, A.M.S. Scabiosa Genus: A Rich Source of Bioactive Metabolites. Medicines 2018, 5, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, N.; Mesmar, J.E.; El Kurdi, R.; Al-Sawalmih, A.; Badran, A.; Patra, D.; Baydoun, E. Halodule Uninervis Extract Facilitates the Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles with Anticancer Activity. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, K.; Baunthiyal, M.; Singh, A. Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Urtica Dioica Linn. Leaves and Their Synergistic Effects with Antibiotics. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences 2016, 9, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Saqr, A.; Khafagy, E.-S.; Alalaiwe, A.; Aldawsari, M.F.; Alshahrani, S.M.; Anwer, Md. K.; Khan, S.; Lila, A.S.A.; Arab, H.H.; Hegazy, W.A.H. Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles by Using Green Machinery: Characterization and In Vitro Toxicity. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, A.; Vilas, V.; Philip, D. Studies on Catalytic, Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Anticancer Activities of Biogenic Gold Nanoparticles. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2015, 212, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Botany, University College of Science, Osmania University, Hyderabad, Telangana, -500 007 India; Hymavathi, K.; Sabitha Rani, A.; Department of Botany, University College of Science, Osmania University, Hyderabad, Telangana, -500 007 India. Synthesis and Characterization of Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) from Chrozophora Rottleri (Geiseler) Spreng. An Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities. AMSR 2024, 3, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Bustam, M.A.; Irfan, M.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Anwaar Asghar, H.M.; Bhattacharjee, S. Green Synthesis of Stabilized Spherical Shaped Gold Nanoparticles Using Novel Aqueous Elaeis Guineensis (Oil Palm) Leaves Extract. Journal of Molecular Structure 2018, 1159, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G., S.; Jha, P.K.; V., V.; C., R.; M., J.; M., S.; Jha, R.; S., S. Cannonball Fruit (Couroupita Guianensis, Aubl.) Extract Mediated Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles and Evaluation of Its Antioxidant Activity. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2016, 215, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, S.; Lushchak, V.I.; Scholz, F. The Pro-Radical Hydrogen Peroxide as a Stable Hydroxyl Radical Distributor: Lessons from Pancreatic Beta Cells. Arch Toxicol 2022, 96, 1915–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejero, I.; González-Lafont, À.; Lluch, J.M.; Eriksson, L.A. Theoretical Modeling of Hydroxyl-Radical-Induced Lipid Peroxidation Reactions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 5684–5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, A.S.; Ibrahim, N.M.; Abdul-Jalil, T.Z. Anti- Psoriatic Effect and Phytochemical Evaluation of Iraqi Scabiosa Palaestina Ethyl Acetate Extract. Plant Sci. Today 2024. [CrossRef]

- Khamees, A.H.; Kadhim, E.J. Isolation, Characterization and Quantification of a Pentacyclic Triterpinoid Compound Ursolic Acid in Scabiosa Palaestina L. Distributed in the North of Iraq. Distributed in the North of Iraq. Plant Sci. Today 2021. [CrossRef]

- Manivasagan, P.; Venkatesan, J.; Senthilkumar, K.; Sivakumar, K.; Kim, S.-K. Biosynthesis, Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Effect of Silver Nanoparticles Using a Novel Nocardiopsis Sp. MBRC-1. BioMed Research International 2013, 2013, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asker, A.Y.M.; Al Haidar, A.H.M.J. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Pelargonium Graveolens Leaf Extract: Characterization and Anti-Microbial Properties (An in-Vitro Study). F1000Res 2024, 13, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghramh, H.A.; Khan, K.A.; Ibrahim, E.H.; Setzer, W.N. Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) Using Ricinus Communis Leaf Ethanol Extract, Their Characterization, and Biological Applications. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, N.U.; Jalil, K.; Shahid, M.; Muhammad, N.; Rauf, A. Pistacia Integerrima Gall Extract Mediated Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles and Their Biological Activities. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2019, 12, 2310–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, N.N.; Vu, L.V.; Kiem, C.D.; Doanh, S.C.; Nguyet, C.T.; Hang, P.T.; Thien, N.D.; Quynh, L.M. Synthesis and Optical Properties of Colloidal Gold Nanoparticles. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2009, 187, 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, F.; Rashidi, M.-R.; Omidi, Y. Ultra-Sensitive Detection by Metal Nanoparticles-Mediated Enhanced SPR Biosensors. Talanta 2019, 192, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozgur, M.U.; Ortadoğulu, E.; Erdemi̇, R.B. Greener Approach to Synthesis of Steady Nano-Sized Gold with the Aqueous Concentrate of Cotinus Coggygria Scop. Leaves. Gazi University Journal of Science 2021, 34, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, N.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Kanungo, M.; DeBruine, A.; Kroll, E.; Gilmore, D.; Eckrose, Z.; Gaston, S.; Matel, P.; Kaltchev, M.; Nickel, A.-M.; Kumpaty, S.; Hua, X.; Zhang, W. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Upland Cress and Their Biochemical Characterization and Assessment. Nanomaterials 2021, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliszewska, I.; Wanarska, E.; Thompson, A.C.; Samuel, I.D.W.; Matczyszyn, K. Biogenic Gold Nanoparticles Decrease Methylene Blue Photobleaching and Enhance Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy. Molecules 2021, 26, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoğlu, A. Rapid Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Antimicrobial Activities. [CrossRef]

- Stalin Dhas, T.; Ganesh Kumar, V.; Stanley Abraham, L.; Karthick, V.; Govindaraju, K. Sargassum Myriocystum Mediated Biosynthesis of Gold Nanoparticles. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2012, 99, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arockiya Aarthi Rajathi, F.; Parthiban, C.; Ganesh Kumar, V.; Anantharaman, P. Biosynthesis of Antibacterial Gold Nanoparticles Using Brown Alga, Stoechospermum Marginatum (Kützing). Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2012, 99, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantari, H.; Turner, R.J. Structural and Antimicrobial Properties of Synthesized Gold Nanoparticles Using Biological and Chemical Approaches. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1482102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhas, T.S.; Kumar, V.G.; Karthick, V.; Govindaraju, K.; Shankara Narayana, T. Biosynthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Sargassum Swartzii and Its Cytotoxicity Effect on HeLa Cells. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2014, 133, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danaei, M.; Dehghankhold, M.; Ataei, S.; Hasanzadeh Davarani, F.; Javanmard, R.; Dokhani, A.; Khorasani, S.; Mozafari, M.R. Impact of Particle Size and Polydispersity Index on the Clinical Applications of Lipidic Nanocarrier Systems. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, S. DLS and Zeta Potential – What They Are and What They Are Not? Journal of Controlled Release 2016, 235, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin Lee, K.; Shameli, K.; Miyake, M.; Kuwano, N.; Bt Ahmad Khairudin, N.B.; Bt Mohamad, S.E.; Yew, Y.P. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Extract of Garcinia Mangostana Fruit Peels. Journal of Nanomaterials 2016, 2016, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliyote, S.; Shaji, J. A Recent Review on Synthesis, Characterization and Activities of Gold Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts. Ind. J. Pharm. Edu. Res 2023, 57, s198–s212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi Tadi, A.; Farhadiannezhad, M.; Nezamtaheri, M.S.; Goliaei, B.; Nowrouzi, A. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Gold Nanoparticles from Citrullus Colocynthis (L.) Schrad Pulp Ethanolic Extract: Their Cytotoxic, Genotoxic, Apoptotic, and Antioxidant Activities. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, K.M.; López-Romero, J.M.; Mendoza, S.; Peza-Ledesma, C.; Rivera-Muñoz, E.M.; Velazquez-Castillo, R.R.; Pineda-Piñón, J.; Méndez-Lozano, N.; Manzano-Ramírez, A. Rapid and Facile Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles with Two Mexican Medicinal Plants and a Comparison with Traditional Chemical Synthesis. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2023, 295, 127109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckiewicz, K.P.; Barcinska, E.; Malankowska, A.; Zauszkiewicz–Pawlak, A.; Nowaczyk, G.; Zaleska-Medynska, A.; Inkielewicz-Stepniak, I. Impact of Gold Nanoparticles Shape on Their Cytotoxicity against Human Osteoblast and Osteosarcoma in in Vitro Model. Evaluation of the Safety of Use and Anti-Cancer Potential. J Mater Sci: Mater Med 2019, 30, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jannathul Firdhouse, M.; Lalitha, P. Cytotoxicity of Spherical Gold Nanoparticles Synthesised Using Aqueous Extracts of Aerial Roots of Rhaphidophora Aurea (Linden Ex Andre) Intertwined over Lawsonia Inermis and Areca Catechu on MCF-7 Cell Line. IET nanobiotechnol. 2017, 11, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assad, N.; Laila, M.B.; Hassan, M.N.U.; Rehman, M.F.U.; Ali, L.; Mustaqeem, M.; Ullah, B.; Khan, M.N.; Iqbal, M.; Ercişli, S.; Alarfaj, A.A.; Ansari, M.J.; Malik, T. Eco-Friendly Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Equisetum Diffusum D. Don. with Broad-Spectrum Antibacterial, Anticancer, Antidiabetic, and Antioxidant Potentials. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 19246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueslati, M.H.; Tahar, L.B.; Harrath, A.H. Catalytic, Antioxidant and Anticancer Activities of Gold Nanoparticles Synthesized by Kaempferol Glucoside from Lotus Leguminosae. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2020, 13, 3112–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar, S.; Parameswari, R.P.; Jayapriya, J.; Tharani, M.; Ali, H.; Aljarba, N.H.; Alkahtani, S.; Alarifi, S. [Retracted] Apoptotic and Antioxidant Activity of Gold Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Marine Brown Seaweed: An In Vitro Study. BioMed Research International 2022, 2022, 5746761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmya, K.; Narendhirakannan, R. Green Synthesis, Characterization and Bioactivity of AuNPs from E. Cardamomum: A Comparative Study. Int J. Pharm. Investigation 2025, 15, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliasih, B.A.; Budi, S.; Katas, H. Synthesis and Application of Gold Nanoparticles as Antioxidants. PHAR 2024, 71, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ryu, D. Silver Nanoparticle-induced Oxidative Stress, Genotoxicity and Apoptosis in Cultured Cells and Animal Tissues. J of Applied Toxicology 2013, 33, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manke, A.; Wang, L.; Rojanasakul, Y. Mechanisms of Nanoparticle-Induced Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. BioMed Research International 2013, 2013, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell line | IC50 (µg/ml) |

| Capan-2 | 4.0 |

| 22RV1 | 2.3 |

| HCT116 | 2.2 |

| MDA-MB-231 | 3.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).