1. Introduction

Activated carbons (AC) may be the most widely used adsorbents due to their exceptional properties (particularly their specific surface area and total pore volume), which enable effective adsorption of contaminants from various fluid streams such as vent gas, drinking water and wastewater [

1,

2]. Typically, carbons or biochars derived from lignocellulosic feedstock such as wood, coconut shell, or other agricultural residues under inert atmosphere are predominantly microporous (i.e., pore widths <2.0 nm). However, when subjected to chemical activation or physical activation through gasification using oxidizing gases such as carbon dioxide (CO₂) or steam at elevated temperatures, the microporous structure can be significantly enhanced. Physical activation refers to the development of microporosity via gasification with an oxidizing agent at temperatures ranging from 700-1100°C [

3]. For example, CO

2 used as an oxidizing gas, its reaction can be simplified as follows:

During the gasification reaction, CO2 must diffuse into the interior of the particle, where it dislodges a carbon atom from its position, thus generating micropores and mesopores (i.e., pore width between 2.0 and 50 nm).

In recent years, calcium carbonate (CaCO

3) nanoparticles have been utilized as templates for synthesizing microporous carbon materials, particularly for electrode applications in energy storage devices [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Notably, biomass materials rich in CaCO₃, such as eggshells, release CO₂ upon calcination at temperatures above 800 °C. This evolved CO₂ can be reused in situ as an activating gas for carbon material production, a concept explored in a growing number of studies [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Shen et al. [

8] demonstrated the synthesis of hierarchical porous carbon by reusing dairy manure as a low-cost carbon precursor and eggshell as both a hard template and activating agent. At an optimized temperature of 800°C and eggshell to dairy manure mass ratio of (2:1), the resulting porous carbon achieved a surface area of 543.6 m

2/g and total pore volume of 0.48 cm

3/g. Panchal et al. [

9] developed a novel method for producing ordered porous carbon from eggshell and coconut shell powder using four mass ratios (eggshell/coconut shell: 1/1, 1/2, 1/3, and 1/4). Their research identified the 1:1 ratio at 800°C as optimal, yielding a BET surface area of 375.4 m

2/g and total pore volume of 0.248 cm

3/g. Hsu et al. [

10] synthesized nitrogen-doped porous carbons using water-caltrop shell and eggshell, with the eggshell serving as the activating agent. At 900°C and residence time of 3 h, and the mass ratio of 2/1 (eggshell/water-caltrop shell), a BET surface area of 677 m

2/g was achieved. Liu et al. [

11] produced eggshell-catalyzed biochar for Pb

2+ adsorption from aqueous solution. These biochars were produced utilizing 1:10, 1:2, and 1:1 mass ratio of eggshell to Eupatorium adenophorum, pyrolyzed at 800°C and 8 °C/min under N

2 atmosphere with 1.5 h residence time. The respective BET surface areas were 67, 621, and 269 m

2/g. Similarly, Li et al. [

12] adopted various mass ratios (eggshell/sawdust: 0/1, 0.2/1, 0.4/1, 0.6/1. 0.8/1, and 1/1) to generate porous carbon materials at 900°C, a heating rate of 5 °C/min and a residence time of 30 minutes. The materials activated by CO₂ evolved from eggshells exhibited BET surface areas between 601.2 and 665.1 m²/g, substantially higher than the 486.4 m²/g observed from sawdust alone indicating that surface area increased proportionally with the eggshell content.

Coffee husk, a by-product of coffee processing, constitutes about 30-50wt% of the total coffee bean weight and is rich in lignocellulosic components such as hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin. Its composition makes it a promising feedstock for the production of value-added products such as organic fertilizers, animal feeds, biofuels and carbon materials, as reviewed in recent studies [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, there is limited availability of studies using coffee husk for the production of biochar [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. In addition, carbonization processes of the aforementioned studies operated at relatively low to moderate temperatures (< 800°C), without specific focus on producing the resulting biochar (or carbon) materials that have improved pore properties. Moreover, coffee husk exhibited low ash content and high volatile matter [

24], implying that it could be an excellent precursor for producing porous carbon materials, or utilized as an alternative energy source [

25].

The aim of the study was to increase the pore properties of the carbon products derived from coffee husk by utilizing eggshells as a renewable source of activating gas (CO2). Various mass ratios of eggshell/coffee husk were investigated to understand the effect of the evolved CO2 on the pore properties of resulting carbon materials. Proximate analysis, calorific value, elemental composition, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and its derivative thermogravimetry (DTG) were conducted to establish baseline information on the feedstock materials. TGA and DTG data for eggshells were also used to define appropriate carbonization conditions. Subsequently, carbonization experiments were conducted under specific parameters and the resulting carbon materials were characterized using nitrogen adsorption/desorption analysis, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). These analyses were used to correlate the pore, textural and chemical characteristics of resulting carbon materials with the carbonization conditions applied.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Thermochemical Characteristics of Coffee Husk and Eggshell

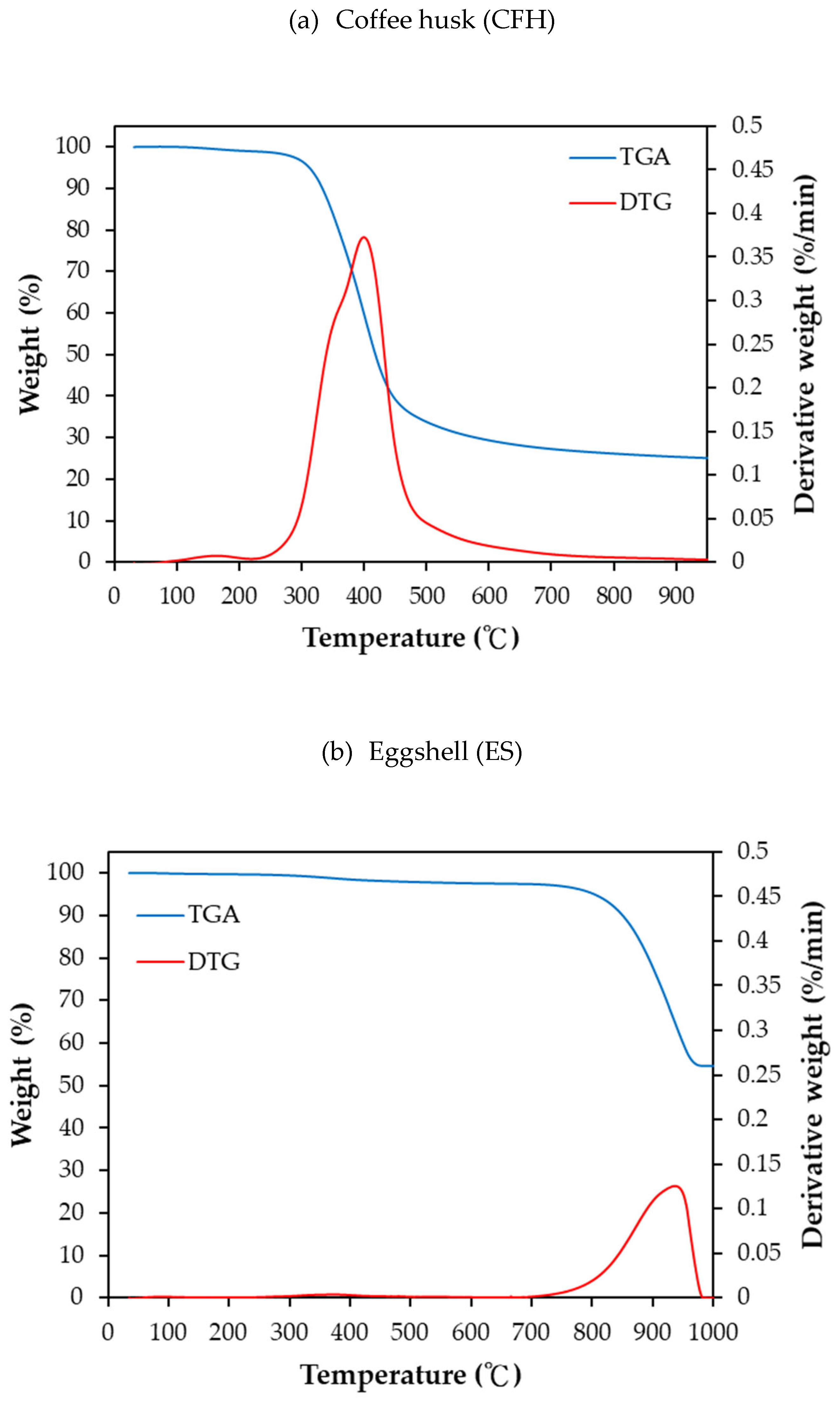

The thermal behaviors of the starting materials, as determined by TGA/DTG analysis at a heating rate of 10°C/min is presented in

Figure 1(a). As expected, majority of the coffee husk sample had a mass loss in the temperature range 250°C to 450°C, corresponding to the thermal decomposition of lignocellulosic components such as hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin [

26]. At 900°C, the residual mass was approximately 25 wt%, comprising primarily inorganic minerals, fixed carbon and other charring residues.

Table 1 summarizes the proximate analysis, calorific value and elemental compositions of coffee husk. The biomass was characterized by high volatile matter (79.36 wt%), moderate fixed carbon content (19.60 wt%) and low ash content (1.05 wt%) on a dry basis. These characteristics are consistent with its high carbon content (45.60 wt%) and calorific value of 19.40 MJ/kg. These results gave further reason that the coffee husk biomass, is a promising precursor for producing carbon materials under the appropriate carbonization conditions [

27].

In contrast the TGA/DTG profile of eggshell powder, shown in

Figure 1(b), reflects its non-lignocellulose, CaCO

3-rich nature [

28]. The most significant change occurred in the temperature range of 800-950°C (over a 15 min time span) where CaCO

3 thermally decomposed into calcium oxide (CaO) and carbon dioxide CO

2. The residual mass of the eggshell sample at 900°C was about 60 wt% consistent with the molecular weights of CaCO

3 (100) and CaO (56). Based on this, the carbon-activation experiments were conducted at 850°C with holding times ranging from 10 to30 minutes, ensuring sufficient decomposition of the eggshell and activation of the carbon material by the evolved CO

2. However, these conditions also resulted with relatively low carbon yields (13-22 wt%) [

29].

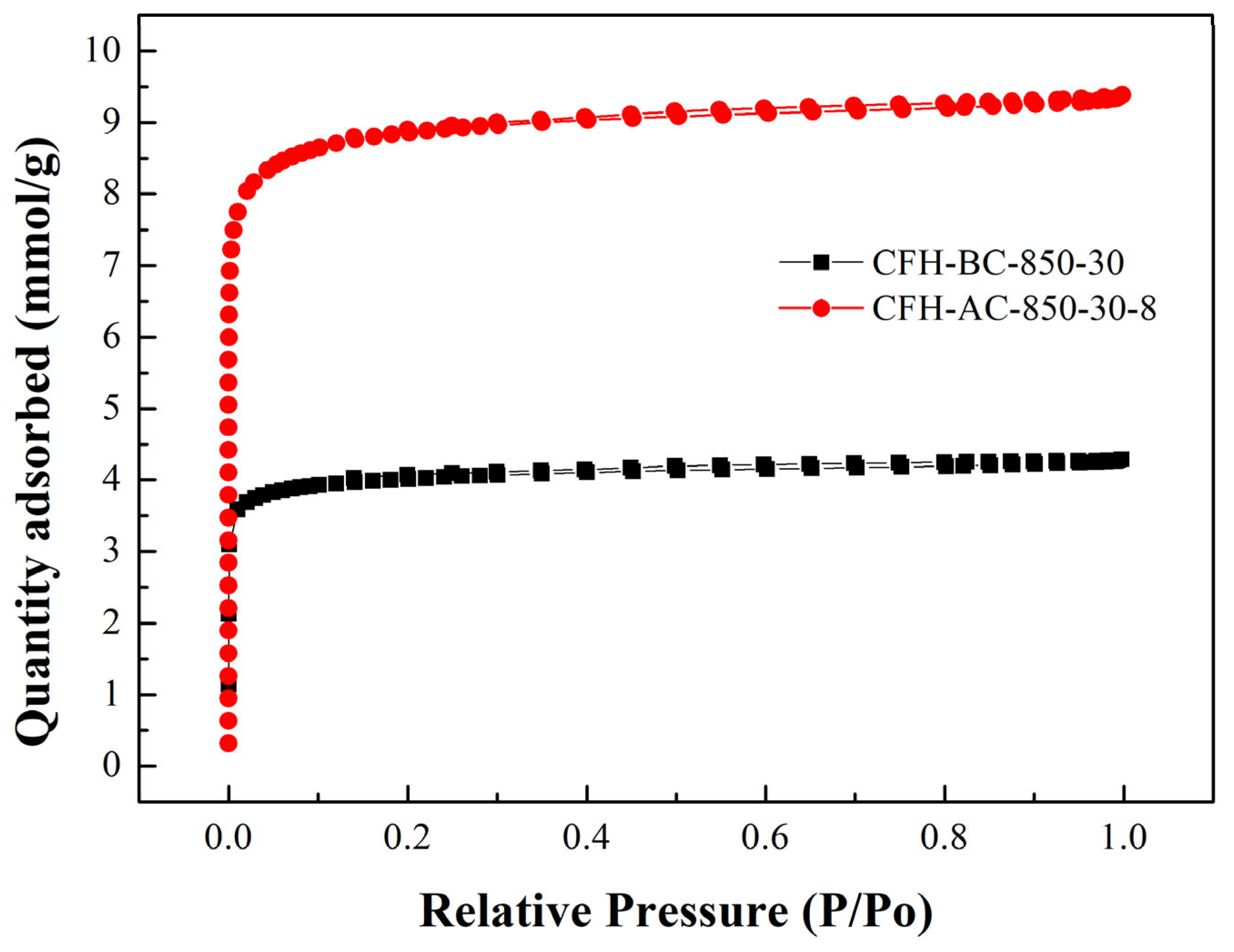

2.2. Pore Properties of Resulting Carbon Materials

The primary pore characteristics of the resulting carbon materials is presented in

Table 2. The data reveal that CO

2 gas released from the eggshell powder at 850°C significantly enhanced pore development. For instance, compared to the biochar sample (CFH-BC-850-30), which had a BET surface area of 321 m

2/g, the activated carbon materials (CFH-AC-850 series) exhibited markedly higher surface areas ranging from 592 to 715 m

2/g. A clear trend was observed in which increasing the eggshell-to-coffee husk mass ratio from 2.0 to 8.0 led to further enhancement in pore properties. This indicated that the amount of evolved CO

2 played in vital role in the formation of pores via activation (or gasification) reactions, resulting in improved characteristics of the carbon materials (CFH-AC-850 series) [

1]. On the other hand, variation in holding time between 10 and 30 minutes had a negligible impact on pore development. The data also show that the portion of residual eggshell increased with higher eggshell loading, this suggested that the eggshell powder did not decompose completely into CaO and CO

2 under the applied conditions.

Table 3 compares the full pore property data for the biochar (CFH-BC-850-30) and the optimal activated carbon(CFH-AC-850-30-8). Notably, the BET surface area and micropore volume of the activated carbon were more than double those of the biochar (155.59 m²/g vs. 714.56 m²/g, respectively).

Figure 2 presents the nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms of the representative BC and AC materials. Both curves conform to Type I isotherms with H4-type hysteresis loops, which are characteristic of microporous materials with slit-like pore structures [

30,

31]. Analyzing the data of the nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms, the pore size distribution can be described using the 2D-NLDFT-HS model [

32]. These curves were not presented, but were a dominant presence of micropores in the range of 0.50 to 1.00 nm was observed.

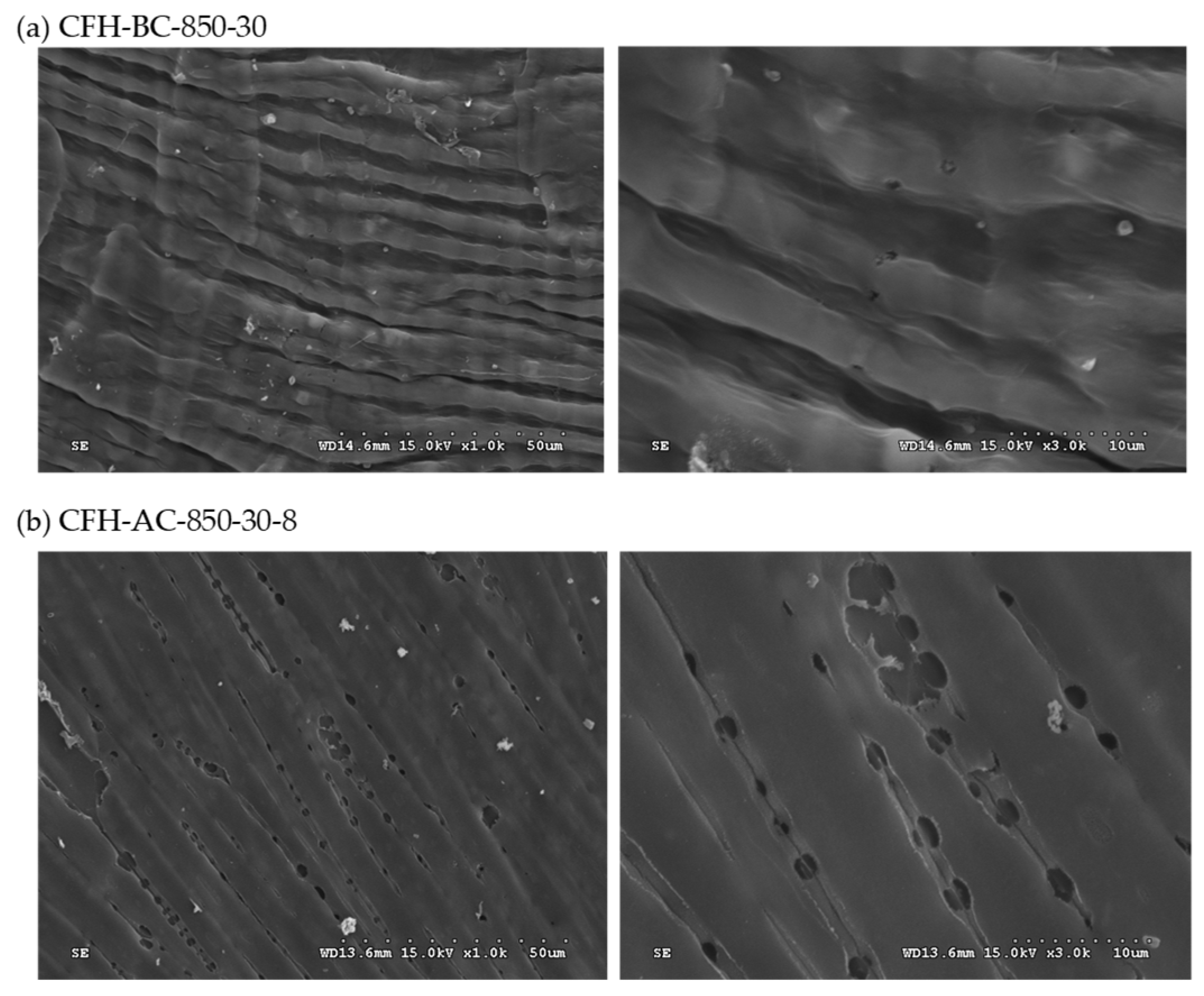

2.3. Textural and Chemical Characteristics of Resulting Carbon Materials

The porous structure inferred from nitrogen adsorption–desorption analysis (

Table 2,

Table 3, and

Figure 2) was further confirmed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Representative samples CFH-BC-850-30 and CFH-AC-850-30-8 were selected for surface morphology analysis. As shown in

Figure 3, the AC material exhibited a significantly more porous structure compared to the biochar under the two magnifications (i.e., ×1,000 and ×3,000). These observations were consistent with the pore properties derived from BET analysis and the nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms. The SEM images also revealed a shriveled, rod-like morphology on the surface of the carbon matrix, which may be attributed to the vascular structure of the lignocellulosic biomass (i.e., coffee husk) and its transformation under high temperature carbonization (850°C).

Elemental composition analysis of the coffee husk and its resulting carbon materials was performed using energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), due to its speed and simplicity. As indicated in

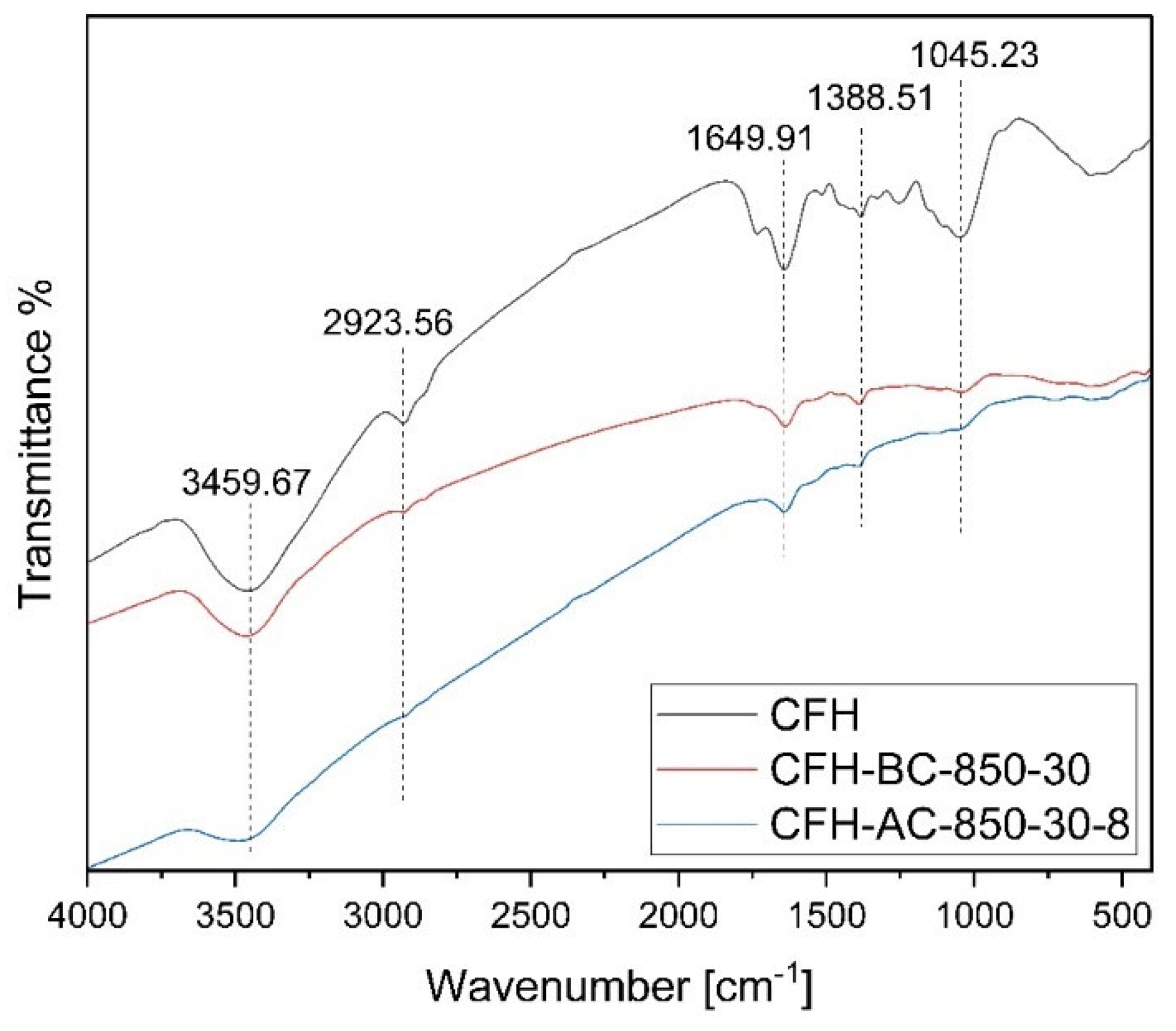

Table 1, the original coffee husk contained 45.60 wt% carbon and 53.45 wt% oxygen. After carbonization and activation, the carbon content of resulting materials increased to over 85 wt%, indicating a high degree of charring under the conditions 850°C and 10-30 minute holding time. Simultaneously, oxygen content was drastically reduced due to the release of oxygen-rich volatiles such as H₂O, CO, and CO₂ during thermal treatment Despite the reduction in oxygen, the carbon materials retained some oxygen-containing functional groups, which can have an impact on the materials surface chemistry affecting the electrostatic interactions. FTIR spectra of the original coffee husk (CFH) and the carbon materials (CFH-BC-850-30 and CFH-AC-850-30-8) are presented in Figure 4. The key absorption peaks positioned at approximately 3460, 2920, 1650, 1390, and 1045 cm

-1 which could be ascribed to the absorption of -OH, C-H (stretching), C-O-C (carbonyl group), C-H (bending), and C–O (stretching), respectively [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Additionally, the peak heights or regions of the carbon materials in Figure 4 were relatively less than those of the raw coffee husk, which is consistent with the results of the EDS findings.

Figure 5.

Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of coffee husk (CFH) and the resulting carbon materials (i.e., CFH-BC-850-30 and CFH-AC-850-30-8).

Figure 5.

Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra of coffee husk (CFH) and the resulting carbon materials (i.e., CFH-BC-850-30 and CFH-AC-850-30-8).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Coffee husk and eggshell were sourced from a local coffee bean manufacturer in Taiwu Township, Pingtung County, Taiwan and breakfast shop in Qianzhen District, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan respectively. The yellow coffee by-product, referred to as coffee husk, derived from the parchment layer during the washing and drying stages of coffee processing. Prior to characterization and carbonization experiments, the biomass sample was oven-dried at 105°C and stored in an air-circulating oven. Eggshells were treated by immersion in dilute acetic acid to remove the inner membrane, followed by drying and grinding into powder. The prepared eggshell powder was stored in airtight glass containers until further use.

3.2. Thermochemical Properties and Thermogravimetric Analysis of Coffee Husk and Eggshell

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out using the instrument TGA-51; Shimadzu Co., Tokyo, Japan, in order to investigate the thermal decomposition behaviors of coffee husk and eggshell. The heating profile involved a temperature increase from room temperature to 1000°C at a rate of 10°C/min under a nitrogen flow of 50 cm3/min. Proximate analysis of the dried coffee husk, including ash, volatile matter, and fixed carbon, was performed in accordance with the Standard Methods of the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). The fixed carbon was calculated by subtracting the ash and volatile matter percentages from 100%. The calorific value, which is closely related to the materials volatile matter and fixed carbon, was determined using a bomb calorimeter (Model: CALORIMETER ASSY 6200; Parr Co., Moline, IL, USA). To better understand the differences between the precursor material (i.e., coffee husk) and resulting carbon materials, additional analyses of the elemental composition and surface oxygen-containing functional groups were also conducted, as described later in this section.

3.3. Carbonization-Activation Experiments

Based on the TGA/DTG results of the eggshell, carbonization-activation experimental conditions were determined and carried out in a vertical fixed-bed reactor. Nitrogen gas was introduced at a flowrate of 500 cm3/min, with a heating rate of 10°C/min up to a final temperature of 850°C, followed by holding times from10-30 minutes. During this period, CO₂ evolved from the thermal decomposition of eggshells acted as the activating gas. A custom double steel-mesh sample holder was used to support the materials, approximately 2.0 g coffee husk was placed in the top holder, while a certain mass of eggshell powder was placed in the bottom of the holder. These combinations achieved mass ratios of eggshells to coffee husk of 2:1, 4:1, 6:1 and 8:1. To evaluate the effect of holding time on the pore properties of resulting carbon materials, two additional times (i.e., 10 and 20 min) were performed under identical process parameters. In total, seven experiments were performed, including one carbonization run without eggshell as a control. The yields of the resulting porous carbon materials and residual eggshell were calculated based on the mass difference before and after the carbonization-activation experiments. The resulting carbon (i.e., biochar) materials from coffee husk (abbreviated as CFH) were coded as follows. CFH-BC-850-30 referred to the biochar (abbreviated as BC) material produced at 850°C and a holding time of 30 minutes, while CFH-AC-850-30-8 referred to activated carbon (abbreviated as AC) materials produced at 850°C and a holding time of 30 minutes using an eggshell/coffee husk mass ratio of 8:1.

3.4. Determinations of Textural and Chemical Characteristics of Coffee Husk-Based Biochar Products

The pore properties of resulting carbon materials were analyzed via nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms at -196°C using an automated analyzer (Model: ASAP 2020; Micromeritics Co., Norcross, GA, USA). Prior to analysis, the carbon samples were degassed to remove moisture and other adsorbed substances. Degassing conditions included heating at 5°C/min up to 90°C under a vacuum of 10 μmHg for 60 minutes followed by a ramping to 200°C and held for 10 hours. BET, Langmuir, and single-point surface areas were calculated based on relative pressure (P/P₀) in the range of 0.05–0.15. Total pore volume was estimated from the amount of nitrogen adsorbed at a relative pressure of 0.995 and converted into liquid volume [

31]. Micropore surface area and volume were determined using the t-plot statistical thickness method, based on the Harkins & Jura model corresponding to the thickness between 0.35 -0.5 nm [

31]. Surface morphology was observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Model: S-3000N; Hitachi Co., Tokyo, Japan). To improve conductivity, non-conductive samples were coated with a thin gold film using an ion sputter (Model: E1010; Hitachi Co., Tokyo, Japan). Elemental analysis was performed using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS; Model: X-stream-2; Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK). Surface functional groups were identified by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR; Model: FT/IR-4600; JASCO Co., Tokyo, Japan). For FTIR analysis, samples were mixed with high-purity potassium bromide (KBr) and ground with an agate mortar to form translucent pellets.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that coffee husk, a major by-product from coffee bean processing, has the potential to produce porous carbon material. Carbonization–activation experiments were conducted in a vertical fixed-bed reactor at a heating rate of 10 °C/min up to 850 °C under nitrogen atmosphere. A custom-designed double-mesh holder was used to enable upward activation of coffee husk by CO₂ evolved from eggshell decomposition. The mass ratios of eggshells to coffee husk used in this experiment were ratios of 2:1, 4:1, 6:1 and 8:1. The results confirmed that CO2 released from eggshell powder decomposition significantly enhanced pore development in the carbon materials at 850°C. Compared to the unactivated biochar (BET surface area of 321 m2/g), the eggshell derived CO2- activated samples exhibited much higher BET surface areas, ranging from 592 to 715 m2/g. These materials showed Type I isotherms with H4 hysteresis loops, indicating the presence of micropores and slit-shaped pores. Increased eggshell loading corresponded to a consistent enhancement in pore properties. SEM, EDS, and FTIR analyses further supported the observed morphological and compositional transformations. Overall, the study demonstrated that high-temperature carbonization of coffee husk, assisted by CO₂ activation from eggshells, is an effective strategy for producing microporous carbon materials with desirable structural and surface characteristics

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-T.T.; formal analysis, C.-H.T. and H.-M.M.J.; data curation, C.-H.T. and H.-M.M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, W.-T.T.; writing—review and editing, W.-T.T. and H.-M.M.J.; supervision, W.-T.T.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Sincere appreciation was expressed to acknowledge the National Pingtung University of Science and Technology for the assistance in the scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Marsh, H.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F. Activated Carbon. Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2006.

- Bansal, R.C.; Goyal, M. Activated Carbon Adsorption. CRC Press: Bocca Raton (FL, USA), 2005.

- Mehdi, R.; Khoja, A.H.; Naqvi, S.R.; Gao, N.; Amin, N.A.S. A Review on production and surface modifications of biochar materials via biomass pyrolysis process for supercapacitor applications. Catalysts 2022, 12, 798.

- Li, T.; Yang, G.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Han, H. Excellent electrochemical performance of nitrogen-enriched hierarchical porous carbon electrodes prepared using nano-CaCO3 as template. J Solid State Electrochem 2013, 17, 2651–2660.

- Wang, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Guan, S. A simple CaCO3-assisted template carbonization method for producing nitrogen doped porous carbons as electrode materials for supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 188, 757–766.

- Xing, B.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Huang, G.; Guo, H.; Cao, J.; Cao, Y.; Yu, J.; Chen, Z. Green synthesis of porous graphitic carbons from coal tar pitch templated by nano-CaCO3 for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J Alloys Compd 2019, 795, 91–102.

- Yang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Ren, B.; Fan, C.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Q.; Zhong, L.; You, C.; Xu, Y.; Yang, R. Modified nano-CaCO3 hard template method for hierarchical porous carbon powder with enhanced electrochemical performance in lithium-sulfur battery. Adv Powder Technol 2021, 32, 3574–3584.

- Shen, F.; Qiu, M.; Hua, Y.; Qi, X. Dual-functional templated methodology for the synthesis of hierarchical porous carbon for supercapacitor. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3(2), 586-591.

- Panchal, M.; Raghvendra, G.; Ojha, S.; Omprakash, M.; Acharya, S.K. A single step process to synthesize ordered porous carbon from coconut shells-eggshells biowaste. Mater Res Express 2019, 6, 115613.

- Hsu, C.H.; Pan, Z.B.; Qu, H.T.; Chen, C.R.; Lin, H.P.; Sun, I.W.; Huang, C.Y.; Li, C.H. Green synthesis of nitrogen-doped multiporous carbons for oxygen reduction reaction using water-caltrop shells and eggshell waste. RSC Adv 2021, 11(26), 15738-15747.

- Liu, D.; Hao, Z.; Chen, D.; Jiang, L.; Li, T.; Tian, B.; Yan, C.; Luo, Y.; Chen, G.; Ai, H. Use of eggshell-catalyzed biochar adsorbents for Pb removal from aqueous solution. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 21808−21819.

- Li, C.; Zhou, S.; Li, Q.; Gao, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Y.; Ding, K.; Hu, X. Activation of sawdust with eggshells. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2023, 171, 105968.

- Janissen, B.; Huynh, T. Chemical composition and value-adding applications of coffee industry by-products: A review. Resour Conserv Recycl 2018, 128, 110-117.

- Klingel, T.; Kremer, J.I.; Gottstein, V.; Rajcic de Rezende, T.; Schwarz, S.; Lachenmeier, D.W. A Review of coffee by-products including leaf, flower, cherry, husk, silver skin, and spent grounds as novel foods within the European Union. Foods 2020, 9, 665.

- Hoseini, M.; Cocco, S.; Casucci, C.; Cardelli, V.; Corti, G. Coffee by-products derived resources. A review. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 148, 106009.

- Sugebo, B. A review on enhanced biofuel production from coffee by-products using different enhancement techniques. Mater Renew Sustain Energy 2022, 11, 91–103.

- Mora-Villalobos, J.A.; Aguilar, F.; Carballo-Arce, A.F.; José-Roberto Vega-Baudrit, J.R.; Trimino-Vazquez, H.; Villegas-Peñaranda, L.R.; Stöbener, A.; Eixenberger, D.; Bubenheim, P.; Sandoval-Barrantes, M.; Liese, A. Tropical agroindustrial biowaste revalorization through integrative biorefineries—review part I: coffee and palm oil by-products. Biomass Conv Bioref 2023, 13, 1469–1487.

- Domingues, R.R.; Trugilho, P.F.; Silva, C.A.; Melo, I.C.N.Ad.; Melo, L.C.A.; Magriotis, Z.M.; Sannchez-Monedero, M.A. Properties of biochar derived from wood and high-nutrient biomasses with the aim of agronomic and environmental benefits. PLoS ONE 2017, 12(5), e0176884.

- Schellekens, J.; Silva, C.A.; Buurman, P.; Rittl, T.F.; Domingues, R.R.; Justi, M.; Vidal-Torrado, P.; Trugilho,P.F. Molecular characterization of biochar from five Brazilian agricultural residues obtained at different charring temperatures. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2018, 130, 106-117.

- Asfaw, E.; Nebiyu, A.; Bekele, E.; Ahmed, M.; Astatkie, T. Coffee-husk biochar application increased AMF root colonization, P accumulation, N2 fixation, and yield of soybean grown in a tropical Nitisol, southwest Ethiopia. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 2019, 181, 419–428.

- Nguyen, X.C.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Nguyen,T.H.C.; Le, Q.V.; Vo, T.Y.B.; Tran, T.C.P.; La, D.D.; Kumar, G.; Nguyen, V.K.; Chang, S.W.; Chung, W.J.; Nguyen, D.D. Sustainable carbonaceous biochar adsorbents derived from agro-wastes and invasive plants for cation dye adsorption from water. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 131009.

- Ngalani, G.P.; Ondo, J.A.; Njimou, J.R.; Njiki, C.P.N.; Prudent, P.; Ngameni, E. Effect of coffee husk and cocoa pods biochar on phosphorus fixation and release processes in acid soils from West Cameroon. Soil Use Manag 2023, 39(2), 817-832.

- Setiawan, A.; Nurjannah, S.; Riskina, S.; Fona, Z.; Muhammad; Drewery, M.; Kennedy, E.M.; Stockenhuber, M. Understanding the thermal and physical properties of biochar derived from pre-washed arabica coffee agroindustry residues. Bioenergy Res 2025, 18, 16.

- Saenger, M.; Hartge, E.U.; Werther, J.; Ogada, T.; Siagi, Z. Combustion of coffee husks. Renew Energy 2001, 23(1), 103-121.

- Carneiro, A.d.C.O.; Zanuncio, A.J.V.; Carvalho, A.G.; Jorge, J.A.C.G.; dos Santos, R.J.C.; Demuner, I.F.; Peres, L.C.; Winter, S.G.; de Castro, V.R.; Branco-Vieira, M.; Araújo, S.d.O. Sustainable production of coffee husk pellets: applying circular economy in waste management and renewable energy production. Resources 2025, 14, 26.

- Chen, D.; Cen, K.; Zhuang, X.; Gan, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Insight into biomass pyrolysis mechanism based on cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin: Evolution of volatiles and kinetics, elucidation of reaction pathways, and characterization of gas, biochar and bio-oil. Combust Flame 2022, 242, 112142.

- Bansal, R.C.; Donnet, J.B.; Stoeckli, F. Active Carbon. Marcel Dekker: New York, 1988.

- Tsai, W.T.; Yang, J.M.; Hsu, H.C.; Lin K.Y.; Chiu, C.S.; Chiu, C.H. Development and characterization of mesoporosity in eggshell ground by planetary ball milling. Micropor Mesopor Mater 2008, 111, 379-386.

- Keiluweit, M.; Vico, P.S.; Johnson, M.G.; Kleber, M. Dynamic molecular structure of plant biomass-derived black carbon (biochar). Environ Sci Technol 2010, 44(4), 1247–1253.

- Condon, J.B. Surface Area and Porosity Determinations by Physisorption: Measurements and Theory; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006.

- Lowell, S.; Shields, J.E.; Thomas, M.A.; Thommes, M. Characterization of Porous Solids and Powders: Surface Area, Pore Size and Density. Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2006.

- Jagiello, J.; Castro-Gutierrez, J.; Canevesi, R.L.S; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Comprehensive analysis of hierarchical porous carbons using a dual-shape 2D-NLDFT model with an adjustable slit-cylinder pore shape Boundary. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021, 13(41), 49472-49481.

- Li, L.; Yao, X.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Ma, W.; Liang, X. Thermal stability of oxygen-containing functional groups on activated carbon surfaces in a thermal oxidative environment. J Chem Eng Jpn 2004, 47(1), 21-27.

- Islam, M.S.; Ang, B.C.; Gharehkhani, S.; Afifi, A.B.M. Adsorption capability of activated carbon synthesized from coconut shell. Carbon Lett 2016, 20, 1-9.

- Johnston, C.T. Biochar analysis by Fourier-transform infra-red spectroscopy. In Biochar: A Guide to Analytical Methods. Singh, B.; Camps-Arbestain, M.; Lehmann, J., Eds.; CRC Press, Boca Raton (FL, USA), 2017; pp. 199-228.

- Qiu, C.; Jiang, L.; Gao, Y.; Sheng, L. Effects of oxygen-containing functional groups on carbon materials in supercapacitors: A review. Mater Des 2023, 230, 111952.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).