1. Introduction

A central challenge in the canonical quantization of general relativity is the so-called

problem of time [

25,

29]. In the Arnowitt–Deser–Misner (ADM) formalism [

1], the diffeomorphism invariance of general relativity leads to Hamiltonian and momentum constraints that eliminate explicit temporal dependence in the quantum theory. The Wheeler–DeWitt equation,

describes a static wavefunctional

over spatial 3-geometries

, with no external time parameter to anchor evolution [

15]. This leads to the so-called “frozen formalism,” in which dynamics must be recovered indirectly via semiclassical approximations [

7,

27] or relational observables [

36,

37]. Despite decades of proposals, no consensus has emerged on how to recover a physically meaningful notion of time within a background-independent, quantum gravitational context.

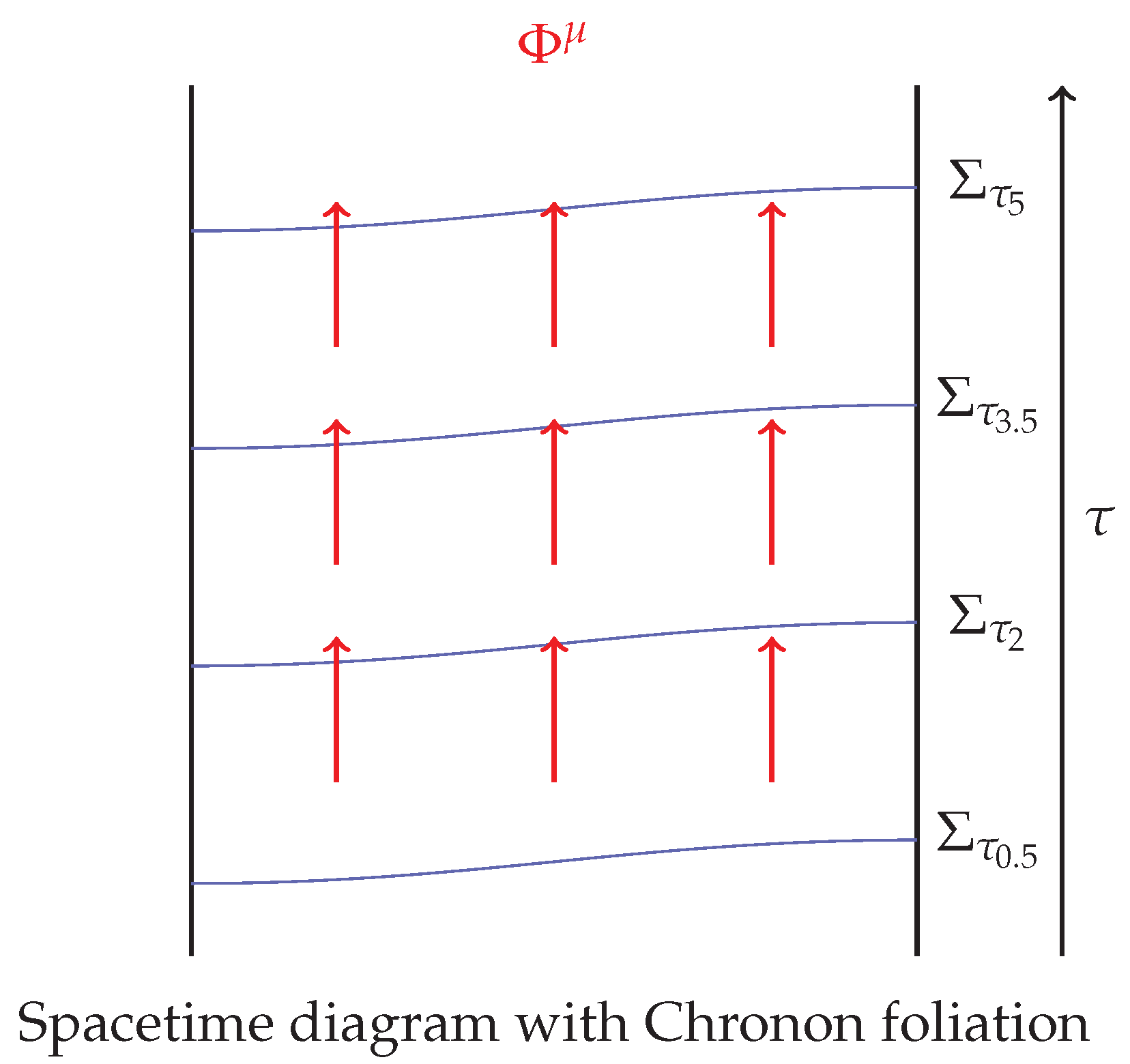

In this work, we propose a resolution grounded in the introduction of a dynamical temporal field—the Chronon field . This field is defined as a smooth, unit-norm, future-directed timelike vector field on a differentiable four-manifold. Its integral curves define a global temporal flow and a foliation of spacetime into spacelike hypersurfaces , labeled by proper time along . The Chronon field thereby provides an intrinsic clock variable from within the gravitational field itself.

We construct a canonical formalism adapted to this foliation and derive a Schrödinger-type evolution equation in for the quantum wavefunctional . This Chronon-adapted Wheeler–DeWitt equation restores temporal evolution to canonical quantum gravity without violating background independence or general covariance. We analyze its constraint structure, Hilbert space, and physical observables, and illustrate the formalism with a minisuperspace model exhibiting Chronon-driven dynamics.

2. Theoretical Context

The problem of time in quantum gravity arises from the collision of two foundational principles: the background independence of general relativity and the unitarity of quantum theory. In general relativity, the absence of a preferred temporal parameter is codified in the invariance under spacetime diffeomorphisms, leading in the Hamiltonian formulation to a Hamiltonian constraint

that annihilates physical states. This gives rise to the Wheeler–DeWitt equation [

15], a timeless wavefunctional equation that admits no obvious mechanism for describing change.

Numerous strategies have been proposed to address this issue. One class of approaches introduces a relational or internal clock by designating one degree of freedom as “time” and describing the evolution of others relative to it [

29,

36,

37]. While conceptually appealing, these constructions are often limited to minisuperspace models and face difficulties generalizing to full field-theoretic settings, especially in the presence of gauge redundancy and nontrivial topology.

Another line of inquiry arises from semiclassical approximations, wherein the gravitational field is treated classically while quantum fields evolve on this background [

26]. Time emerges approximately via the WKB phase of the gravitational sector. However, this solution is only valid in a regime where backreaction and quantum fluctuations are negligible, and it offers no consistent foundation for a fundamentally quantum geometry.

More radical proposals, such as histories-based or decoherence-functional approaches [

22], or the emergence of time from thermodynamic or quantum informational principles [

14,

30], remain highly interpretive and lack a consistent dynamical framework in which time appears as a bona fide observable with canonical status.

In contrast, the Chronon field approach developed here embeds a physical, dynamical temporal field into the geometry, restoring intrinsic time evolution while preserving diffeomorphism invariance. It is distinct from prior scalar clock models in that is a genuine vector field defining both causal structure and foliation geometry. The normalization constraint ensures its compatibility with the Lorentzian structure of spacetime, and its quantization leads naturally to a Schrödinger-type equation in the internal proper time . This provides a coherent resolution of the frozen dynamics of the Wheeler–DeWitt equation without invoking external or approximate constructs.

3. Chronon Field and Temporal Foliation

3.1. Chronon Field Definition and Constraints

Let be a four-dimensional oriented Lorentzian manifold with metric signature . Greek indices range over spacetime coordinates , where denotes the temporal component in any local coordinate chart.

We define the Chronon field as a smooth vector field

, where

is the tangent bundle of

M. It satisfies the following conditions at every point

:

These constraints ensure that

is a future-directed, unit-norm timelike vector field that defines a physically admissible temporal orientation throughout spacetime. The integral curves of

represent the worldlines of a field of comoving observers and induce a globally consistent arrow of time [

19,

40].

We emphasize that

is treated as a dynamical, physical field—not a coordinate artifact. Its geometry and topology play a central role in defining the causal and quantum structure of spacetime. The unit-norm condition (

2) distinguishes

from arbitrary clock fields proposed in scalar time models [

28,

36].

3.2. Intrinsic Time and Foliated Spacetime

The Chronon field induces a foliation of

M into a family of spacelike hypersurfaces

, defined as level sets of a scalar function

called

Chronon time, satisfying:

where

is a positive lapse function ensuring that

satisfies the unit-norm constraint.

Figure 1.

Chronon field generates intrinsic foliation into spacelike slices along proper time .

Figure 1.

Chronon field generates intrinsic foliation into spacelike slices along proper time .

The Frobenius theorem guarantees that such a foliation exists if and only if the twist of

vanishes:

where the projection tensor onto the 3-space orthogonal to

is given by:

Assuming

, the hypersurfaces

are smooth, spacelike, and orthogonal to

[

17,

19]. The scalar field

then acts as an intrinsic clock, with

tangent to the gradient flow of

.

This foliation allows us to express the full spacetime as:

where

are coordinates on each

, and

evolves along the integral curves of

. This structure provides the necessary foundation to define canonical variables, quantize the theory, and interpret physical observables with respect to an internal temporal evolution parameter.

In the following sections, we construct the Hamiltonian formalism based on this foliation and derive a quantum evolution equation in that resolves the timelessness of the Wheeler–DeWitt framework.

4. ADM Decomposition Adapted to the Chronon Field

To formulate the canonical structure of gravity with an intrinsic temporal field, we perform a

decomposition of spacetime aligned with the foliation induced by the Chronon field

. This foliation defines a family of spacelike hypersurfaces

, each labeled by the proper time

along the integral curves of

. The Chronon field thus provides a dynamically defined slicing of the four-dimensional manifold into space and time [

3,

19].

4.1. 3+1 Variables and Chronon-Aligned Slicing

Let

M be foliated as

, with coordinates

adapted to the Chronon time

and spatial coordinates

on

. The Chronon field

is identified with the unit future-directed normal vector to each hypersurface:

The spacetime metric

can be decomposed as:

where

is the induced spatial metric on

:

In coordinates adapted to the foliation, the line element becomes:

where:

is the lapse function, governing the proper time between hypersurfaces,

is the shift vector, describing the coordinate displacement of spatial points between successive slices,

is the induced 3-metric on .

In the Chronon-adapted formulation, the lapse function

N is determined dynamically by the relation

, and the shift vector

may be chosen to vanish by coordinate choice, simplifying the decomposition [

40].

4.2. Metric, Lapse, and Conjugate Momenta

The canonical variables are derived from the ADM action for general relativity, which in units

, reads:

where:

The canonical momentum conjugate to

is:

The Hamiltonian density is then expressed as:

with:

These are the Hamiltonian and momentum constraints arising from the diffeomorphism invariance of general relativity [

27,

32].

In the Chronon framework, the slicing is determined by the physical field

rather than arbitrary gauge choice. The lapse

N is fixed by the norm of

via:

ensuring compatibility with the Chronon normalization.

The foliation dictated by therefore provides a physical, dynamical time parameter with respect to which the wavefunctional will evolve in the quantum theory. This sets the stage for constructing a canonical formalism that avoids the frozen nature of the standard Wheeler–DeWitt equation.

5. Hamiltonian and Constraint Structure

In the Chronon-adapted framework, the total Hamiltonian comprises both the gravitational sector, derived from the ADM decomposition of general relativity, and the dynamical contributions of the Chronon field

. We now formulate the full Hamiltonian density, identify the constraint structure, and examine the consistency conditions ensuring closure of the constraint algebra [

3,

19,

23].

5.1. Total Hamiltonian with Chronon Contribution

The Chronon field

is a dynamical field subject to the normalization constraint

, and is assumed to be smooth and future-directed. On a fixed hypersurface

, we decompose

into its temporal and spatial components:

with

fixed implicitly by the normalization condition and the induced 3-metric

.

We introduce a canonical momentum

conjugate to

, satisfying:

The Chronon field action includes a kinetic term constructed from its antisymmetric derivative tensor:

analogous to a field strength [

42]. The Chronon Hamiltonian density is defined as:

where:

is a coupling constant (with dimensions of inverse length squared),

enforces the normalization constraint via a Lagrange multiplier .

The total Hamiltonian density is then:

and the full Hamiltonian reads:

The lapse N and shift are determined by the foliation structure imposed by , thereby removing their role as arbitrary Lagrange multipliers and embedding them into the dynamical system.

5.2. Constraint Algebra and Consistency Conditions

The Chronon-modified theory features an extended set of constraints, including:

The Hamiltonian constraint ,

The momentum (diffeomorphism) constraint ,

The Chronon normalization constraint ,

Any potential secondary constraints arising from the preservation of under time evolution.

Preserving

under evolution requires:

This generates a secondary constraint

:

The full set of constraints

must close under Poisson brackets to ensure consistency. This closure defines a first-class constraint algebra if no further conditions arise [

23,

38].

Schematically, we expect:

This algebraic structure is essential for ensuring the self-consistency of the canonical quantization procedure. It also guarantees that gauge redundancies are properly accounted for, and that physical degrees of freedom are well defined modulo diffeomorphism and Chronon reparametrization invariance.

In the next section, we proceed to quantize this extended canonical system and derive the Chronon-adapted Wheeler–DeWitt equation, in which emerges as a genuine evolution parameter for the quantum wavefunctional.

6. Chronon Wheeler–DeWitt Equation

With the canonical structure defined and the Chronon field incorporated into the foliation, we now proceed to quantize the system. The result is a generalization of the Wheeler–DeWitt framework in which time evolution is restored intrinsically through the Chronon time

. We define a time-dependent wavefunctional, formulate the corresponding Schrödinger-type equation, and discuss the status of quantum constraints [

15,

27,

29,

36].

6.1. Canonical Quantization and Wavefunctional

Canonical quantization proceeds by promoting the canonical variables to operators acting on wavefunctionals:

which depend on the spatial 3-metric

, the Chronon field spatial components

, and the intrinsic Chronon time

.

The canonical momenta become functional derivatives:

The quantum constraints are imposed as operator equations:

where the hat denotes quantum operators obtained from the classical constraints.

The Hilbert space consists of square-integrable functionals over the space of admissible configurations satisfying the constraints:

6.2. Intrinsic Schrödinger-Type Evolution in

The novelty of the Chronon framework lies in restoring intrinsic time evolution to the wavefunctional. Because the Chronon field induces a physical foliation of spacetime and defines a proper time parameter

, we can promote

to an evolution variable [

7,

25,

37].

We define a Schrödinger-type equation:

where

is the quantum Hamiltonian operator corresponding to the total classical Hamiltonian:

The evolution of the state in is therefore governed by the dynamics of the Chronon field itself. This equation is not frozen: it describes genuine temporal evolution in an internally defined time parameter, without appeal to external clocks or semiclassical backgrounds.

Consistency with the constraint equations (

33)–(35) ensures that

preserves the constraint surface in Hilbert space.

An important feature of this construction is its compatibility with unitarity: the inner product is preserved under evolution in

,

provided

is self-adjoint with respect to the physical inner product.

In the semiclassical limit, where

becomes approximately uniform and classical,

corresponds to the proper time along classical observers’ worldlines, and the evolution equation (

37) reduces to the expected semiclassical Schrödinger equation for quantum matter on a classical background geometry.

This construction thus resolves the timelessness of the standard Wheeler–DeWitt approach by embedding time evolution into the quantum dynamics via a physical, intrinsic field. In the next section, we formalize the Hilbert space structure and discuss the interpretation of observables in this framework.

7. Hilbert Space and Relational Observables

Having constructed a Schrödinger-type equation in Chronon time

, we now define the associated Hilbert space structure and interpret physical observables within this framework. A key challenge in quantum gravity is to formulate a consistent inner product that respects the constraints and allows a physically meaningful notion of evolution and measurement. The Chronon framework enables this by anchoring observables and states to a dynamically defined temporal background [

25,

31,

39].

7.1. Inner Product and Constraint Imposition

Let

denote the space of kinematically admissible field configurations

on a spatial hypersurface

, where

satisfies the normalization constraint

. The kinematic Hilbert space is:

where

is an appropriate diffeomorphism-invariant measure on field space [

4].

Physical states are wavefunctionals

satisfying the quantum constraints:

To define the physical Hilbert space, we implement a projection from

to the physical subspace

consisting of states annihilated by the constraints. This is achieved via the group averaging procedure [

4,

31]:

where

represents the unitary action of the gauge group generated by the constraints, and

is the group manifold.

The result is a physical inner product that is invariant under spatial diffeomorphisms and gauge transformations induced by the Chronon normalization and Hamiltonian constraints. The time dependence of states is then governed by the intrinsic Schrödinger equation:

with

acting invariantly on

.

7.2. Observables and Chronon-Conditioned Dynamics

In canonical quantum gravity, Dirac observables are typically defined as quantities commuting with all first-class constraints [

16]. However, in practice, such observables are highly nonlocal and difficult to construct. The Chronon framework offers a physically transparent alternative: define relational observables with respect to the intrinsic time

defined by the Chronon field.

Let

be a gauge-invariant functional on

. Its quantum expectation value at Chronon time

is:

Such observables represent conditional expectations of spatial geometric quantities (or matter fields in extended models) given a definite value of the physical clock

. This restores a form of Heisenberg evolution in an internal time parameter:

The presence of the Chronon field enables us to bypass the ambiguity of interpreting timeless states and to define physical change intrinsically and relationally. For example, in cosmological models, may be the spatial volume operator or curvature scalars, evolving deterministically with respect to .

Moreover, the Chronon framework admits a Born-rule interpretation: probabilities for configurations at

are computed via the squared modulus of the wavefunctional:

subject to normalization with respect to the physical measure. This supplies a coherent probabilistic framework compatible with unitary evolution and background independence.

In summary, the Chronon field provides both a physical clock and a gauge-invariant anchor for quantum observables, enabling us to define relational dynamics in a background-free quantum gravitational setting.

8. Model Applications

To concretize the Chronon-based formalism, we now explore simplified models where the intrinsic temporal dynamics and topological structure of the Chronon field produce tractable and interpretable physical phenomena. We begin with a minisuperspace model of homogeneous cosmology, followed by a conceptual outline of topological decoherence effects in the full theory.

8.1. Minisuperspace Example: Chronon Cosmology

Consider a spatially homogeneous, isotropic universe with metric of the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) form:

where

is the scale factor and

denotes the metric on the unit 3-sphere.

In this symmetry-reduced setting, the Chronon field must be compatible with homogeneity and isotropy. The most general ansatz for

consistent with FLRW symmetry is:

with

identified as the proper time along

and

enforcing the normalization constraint

.

The total action reduces to:

where

denotes the homogeneous Chronon scalar component (capturing perturbative degrees of freedom or deviations), and

V encodes curvature and Chronon potential terms.

Canonical quantization leads to the minisuperspace wavefunctional:

and the corresponding Schrödinger-type equation:

This equation describes unitary evolution of the universe’s quantum state in intrinsic Chronon time. Importantly,

here is not an external parameter, but an emergent internal clock derived from the Chronon field itself [

5,

25,

36].

One may interpret solutions to Eq. (

53) in terms of conditional amplitudes:

depending on which variable is treated as relational reference.

This model demonstrates how the Chronon formalism converts the traditional Wheeler–DeWitt constraint into a time-dependent evolution equation with clear probabilistic interpretation [

27].

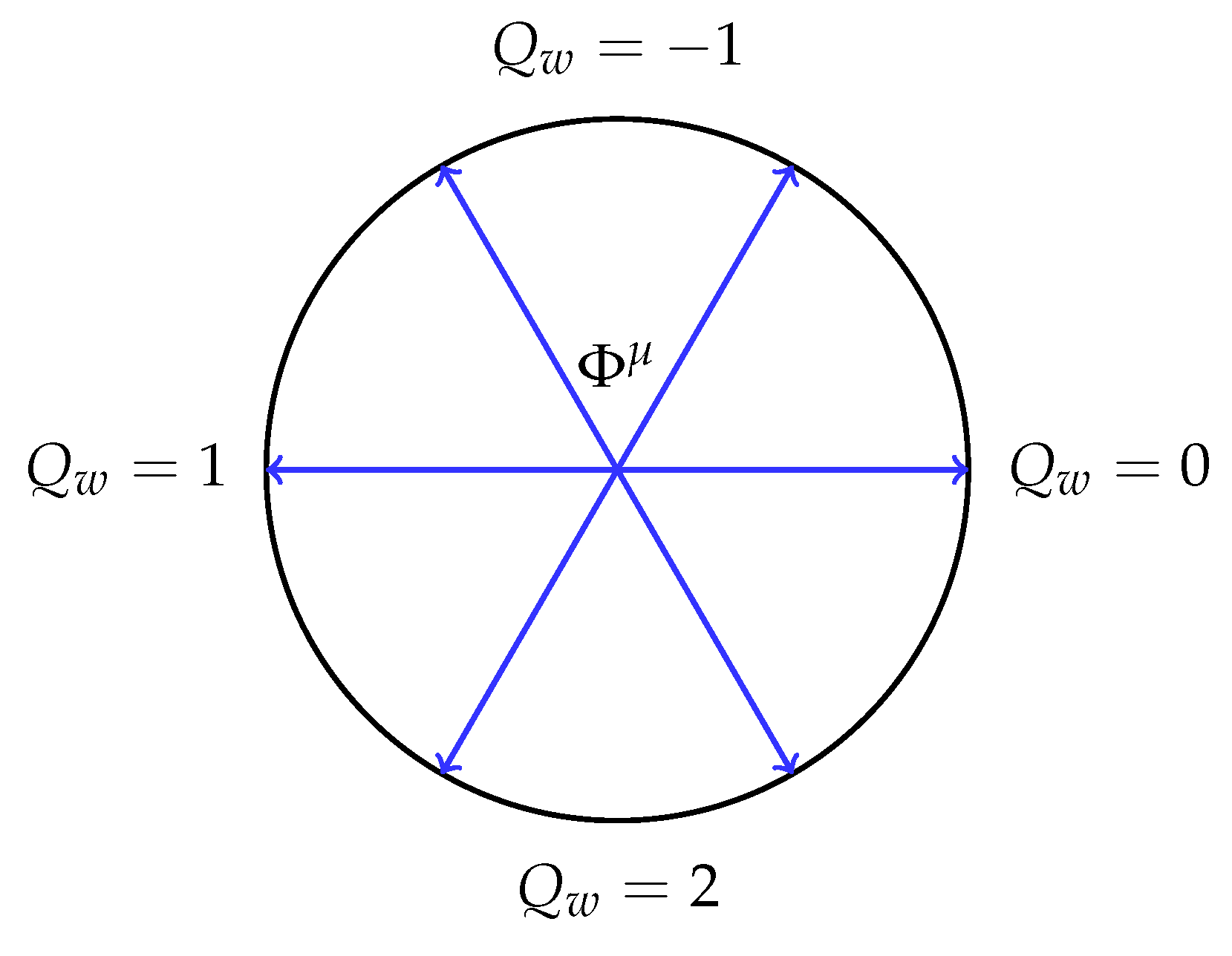

8.2. Topological Decoherence and Quantum Time Effects

In the full Chronon theory, nontrivial topological configurations of the field (e.g., winding modes characterized by ) may play a dynamical role in quantum evolution. Such topological sectors are expected to influence the coherence properties of quantum states in the following ways:

1. Superselection of Topological Sectors.

If the Chronon field admits distinct winding number sectors

, then quantum transitions between sectors may be suppressed or forbidden. States may decohere into topologically isolated branches, labeled by distinct values of

. The Hilbert space becomes a direct sum:

with independent evolution within each sector [

4,

10].

2. Time Decoherence from Topological Entanglement.

Quantum fluctuations of

in regions of high curvature may lead to entanglement between different foliation histories. As a result, decoherence in the Chronon time parameter

may emerge, suppressing interference between histories with incompatible topologies. This resembles a “quantum clock decoherence” mechanism [

20,

21].

3. Discrete Spectra of Temporal Transitions.

If transitions between Chronon winding sectors are quantized, then temporal evolution itself may occur in discrete steps. This would manifest as quantized entropy increments (e.g., in black hole evolution) or as “temporal beats” in gravitational wave echoes from strong-field scattering events [

11].

Figure 2.

Distinct Chronon topological sectors visualized by different winding directions of around a compact domain.

Figure 2.

Distinct Chronon topological sectors visualized by different winding directions of around a compact domain.

These effects suggest that Chronon dynamics encode a new layer of temporal quantum structure, blending topological invariants with causal ordering in a physically meaningful and potentially observable way. Further development will require full nonperturbative quantization and path integral treatments incorporating Chronon topology.

9. Comparison with Relational and Timeless Time Approaches

The Chronon field formalism developed in this work introduces a dynamically constrained, timelike vector field that restores intrinsic time evolution in canonical quantum gravity. To clarify its conceptual position, we now compare this approach to several established models that aim to address the problem of time through alternative temporal embeddings.

The Page–Wootters mechanism treats time as a correlation between a global, timeless state and a clock subsystem [

35]. Temporal evolution is recovered via conditional probabilities: the system evolves “with respect to” the state of an internal clock.

The Chronon framework also defines evolution relationally, but it does so through a globally defined dynamical field rather than a fixed subsystem.

Unlike Page–Wootters, which lacks a proper Hamiltonian generating evolution in clock time, the Chronon approach yields a Schrödinger-type equation in the internal time , with a self-adjoint evolution generator .

The Chronon time parameter is geometrically and causally embedded, in contrast to the abstract conditioning framework of Page–Wootters.

Barbour proposes that time is illusory, and that the universe should be described by a timeless configuration space of spatial geometries [

7]. Change arises from correlations between static records in configuration space.

While the Chronon construction is compatible with relational principles, it does not discard time altogether. Instead, it introduces a physical field that endows spacetime with an intrinsic notion of proper time .

This construction allows for genuine unitary evolution, rather than the emergent perspectival change advocated in timeless theories.

Shape dynamics recasts general relativity by trading refoliation invariance for spatial conformal symmetry [

8]. This introduces a preferred time parameter at the classical level associated with volume-preserving evolution.

The Chronon formalism preserves full spacetime diffeomorphism invariance, avoiding the need for symmetry trading.

Time evolution arises from a dynamically constrained internal field rather than from a fixed conformal gauge.

In contrast to these alternative paradigms, the Chronon approach reinstates time as a canonical, background-independent dynamical entity that naturally resolves the frozen formalism of the Wheeler–DeWitt equation, while maintaining compatibility with the relational and diffeomorphism-invariant principles of general relativity.

10. Discussion and Outlook

We have developed a reformulation of canonical quantum gravity in which intrinsic time evolution is restored through the introduction of a dynamical temporal field—the Chronon field

. This unit-norm, future-directed timelike vector field defines a physical foliation of spacetime and provides a natural scalar clock

. By embedding this structure into the Hamiltonian framework, we derived a Chronon-adapted Wheeler–DeWitt equation that governs unitary evolution of the wavefunctional in intrinsic time [

25,

36,

39].

This approach resolves the problem of time not by reducing the gravitational constraints to semiclassical approximations, but by introducing a physically motivated clock field that maintains background independence and general covariance [

2,

7]. The Chronon field does not rely on external reference structures: it is a legitimate dynamical variable with its own constraint surface and quantum degrees of freedom.

The Chronon formalism realigns the conceptual structure of quantum gravity:

The Chronon field has potentially observable consequences:

Several directions remain open for development:

Full Path Integral Formulation: Extending the Chronon dynamics to a covariant path integral framework, incorporating summation over foliation classes [

21].

Coupling to Matter Fields: Embedding standard model fields into the Chronon background, and exploring implications for quantum field theory in curved spacetime with intrinsic time [

41].

Topological Quantum Gravity: Further analysis of Chronon winding sectors, superselection, and entropy quantization using topological field theory methods [

9].

Quantum Simulation and Clocks: Implementing Chronon dynamics in quantum simulators or analyzing correlations with operational definitions of time in quantum information theory [

13,

33].

In sum, the Chronon-adapted Wheeler–DeWitt framework offers a novel, technically rigorous, and conceptually coherent path toward a quantum theory of gravity with physically meaningful time evolution. It invites further theoretical elaboration, mathematical analysis, and potentially even experimental exploration in regimes where the quantum structure of time itself becomes observable.

10.1. Prospects for Observational Signatures

While the Chronon field formalism is inherently nonperturbative and background-free, several possible observational avenues arise:

Spatial fluctuations of the Chronon lapse function during inflation may leave imprints in the primordial curvature perturbations. Assuming a perturbative deviation , the induced modulation in the scalar power spectrum could be constrained by current Planck data at the level, leading to bounds on Chronon field variance.

Transitions between Chronon winding sectors near strong-field regions (e.g., black hole horizons) could generate discrete shifts in temporal structure. This may manifest as observable delays or “beats” in post-merger ringdown signals, with frequency splitting on the order of for the winding-induced shift. Such effects could also relate to entropy quantization .

Emerging platforms in quantum optics and information processing allow simulation of relational clocks and indefinite causal structures [

33,

34]. A synthetic Chronon field could be engineered using control Hamiltonians defining local clocks and simulating topological transitions through parameter quenches. Measurement of decoherence in these artificial “Chronon time” variables could validate or falsify aspects of the framework.

These avenues suggest that even if direct detection of Chronon dynamics lies beyond current reach, meaningful bounds or simulations could test their physical consequences.

10.2. Physical Interpretation and Operational Status of the Chronon Field

The Chronon field

plays a dual role: it is both a dynamical entity in the gravitational sector and an emergent reference structure for defining intrinsic time. Physically, the scalar function

satisfying

can be interpreted as an operational clock variable, accessible in principle through localized measurements of proper time:

This aligns with the notion of time in the Page–Wootters formalism [

35], where evolution is encoded in conditional probabilities relative to a clock subsystem. Here, the Chronon field generalizes this idea to a field-theoretic and geometrical setting.

Coupling to matter fields can be introduced via modified covariant derivatives or by interpreting

as defining a preferred foliation in matter Lagrangians, e.g.,

where

encodes possible Chronon-matter interaction strength.

Moreover, recent developments in quantum reference frames suggest that

may correspond to a coarse-grained limit of relational clock degrees of freedom [

18]. In this sense, the Chronon field acquires an operational status not unlike a collective coordinate frame in many-body quantum systems.

Further development is needed to clarify whether arises as an effective field from more fundamental quantum symmetries or has direct observable consequences in regimes such as cosmology, black hole interiors, or quantum simulators.

Appendix A. Toward a Path Integral Formulation

While the Chronon framework has thus far been developed within the canonical quantization paradigm, a path integral extension would provide several advantages, including manifest covariance, clearer connections to semiclassical approximations, and potential compatibility with spin foam and topological quantum field theory (TQFT) methods.

Appendix A.1. Chronon Path Integral Structure

A natural starting point is to define the transition amplitude between 3-geometries and Chronon configurations on initial and final hypersurfaces

and

:

subject to the constraint

and suitable gauge fixing. The action

includes the standard Einstein–Hilbert term and Chronon contributions:

where

enforces normalization and

encodes possible kinetic and topological terms for

.

Appendix A.2. Foliation Sums and Causal Sectors

Because the Chronon field dynamically defines the foliation structure, a fully covariant formulation must include a sum over foliation classes. Analogous to the approach in causal dynamical triangulations (CDT), this leads to a generalized sum over both geometries and Chronon-induced causal orders:

where

denotes distinct topological sectors, including nontrivial winding classes relevant for Chronon-induced decoherence.

Appendix A.3. Chronon Correlation Functions

In analogy with standard field theory, observables in this formalism are correlation functions conditioned on intrinsic Chronon time

:

Such observables remain relational, but are embedded within a fully covariant sum-over-histories framework.

Appendix A.4. Future Directions

This program suggests several avenues:

Embedding the Chronon field into spin foam models, identifying with time-normal vectors at faces or dual graphs.

Formulating topologically invariant versions of the path integral using TQFT tools [

9,

42].

Implementing Chronon-based causal structure in the effective actions of loop quantum gravity or group field theories.

A fully developed path integral for the Chronon field may unify its canonical and covariant facets, potentially uncovering new relations between time, topology, and quantum geometry.

References

- R. Arnowitt, S. Deser, and C. W. Misner, The dynamics of general relativity, in *Gravitation: An Introduction to Current Research*, ed. L. Witten, Wiley (1962) [arXiv:gr-qc/0405109].

- E. Anderson, Problem of Time in Quantum Gravity, Annalen Phys. 524, 757 (2012) [arXiv:1206.2403]. [CrossRef]

- R. Arnowitt, S. Deser, and C. W. Misner, Republication of: The dynamics of general relativity, Gen. Rel. Grav. 40, 1997–2027 (2008) [arXiv:gr-qc/0405109]. [CrossRef]

- A. Ashtekar, J. Lewandowski, D. Marolf, J. Mourão, and T. Thiemann, Quantization of diffeomorphism invariant theories of connections with local degrees of freedom, J. Math. Phys. 36, 6456 (1995) [arXiv:gr-qc/9504018]. [CrossRef]

- A. Ashtekar and M. Bojowald, Quantum Geometry and the Schwarzschild Singularity, Class. Quant. Grav. 23, 391 (2006) [arXiv:gr-qc/0509075]. [CrossRef]

- A. Ashtekar, T. Pawlowski, and P. Singh, Quantum nature of the big bang, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 141301 (2006) [arXiv:gr-qc/0602086].

- J. Barbour, The timelessness of quantum gravity: I. The evidence from the classical theory, Class. Quant. Grav. 11, 2853 (1994).

- J. Barbour, T. Koslowski, and F. Mercati, The Solution to the Problem of Time in Shape Dynamics, Class. Quant. Grav. 31, 155001 (2014) [arXiv:1302.6264]. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Baez, Spin Foam Models, Class. Quant. Grav. 15, 1827 (1998) [arXiv:gr-qc/9709052].

- T. Banks, Prolegomena to a Theory of Bifurcating Universes, Nucl. Phys. B 309, 493 (1988). [CrossRef]

- R. Bousso, A Covariant Entropy Conjecture, JHEP 07, 004 (1999) [arXiv:hep-th/9905177].

- M. Bojowald, Absence of singularity in loop quantum cosmology, Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5227 (2001) [arXiv:gr-qc/0102069]. [CrossRef]

- Č. Brukner, Quantum causality, Nature Phys. 10, 259–263 (2014).

- A. Connes and C. Rovelli, Von Neumann algebra automorphisms and time-thermodynamics relation in generally covariant quantum theories, Class. Quant. Grav. 11, 2899 (1994). [CrossRef]

- B. S. DeWitt, Quantum Theory of Gravity. I. The Canonical Theory, Phys. Rev. 160, 1113 (1967). [CrossRef]

- P. A. M. Dirac, Lectures on Quantum Mechanics, Yeshiva University Press (1964).

- R. Geroch, Domain of dependence, J. Math. Phys. 11, 437 (1970).

- F. Giacomini, E. Castro-Ruiz, and Č. Brukner, Quantum mechanics and the covariance of physical laws in quantum reference frames, Nature Commun. 10, 494 (2019). [CrossRef]

- E. Gourgoulhon, 3+1 Formalism and Bases of Numerical Relativity, Lecture Notes in Physics, vol. 846, Springer (2012).

- J. J. Halliwell, Decoherent histories and hydrodynamic equations, Phys. Rev. D 51, 1051 (1995) [arXiv:gr-qc/9407040]. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Hartle, Quantum Cosmology: Problems for the 21st Century, in *Proceedings of the 1993 Les Houches Summer School*, North-Holland (1995).

- J. B. Hartle, Spacetime Quantum Mechanics and the Quantum Mechanics of Spacetime, in *Gravitation and Quantizations*, Les Houches Summer School (1992), North-Holland (1995).

- M. Henneaux and C. Teitelboim, Quantization of Gauge Systems, Princeton University Press (1992).

- S. Hossenfelder and L. Smolin, Conservative solutions to the black hole information problem, Phys. Rev. D 81, 064009 (2010) [arXiv:0901.3156]. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Isham, Canonical quantum gravity and the problem of time, in *Integrable Systems, Quantum Groups, and Quantum Field Theories*, NATO ASI Series, vol. 409, Springer (1993) [arXiv:gr-qc/9210011].

- C. Kiefer, Wave packets in minisuperspace, Phys. Rev. D 38, 1761 (1988). [CrossRef]

- C. Kiefer, Quantum Gravity, Oxford University Press, 2nd ed. (2007).

- K. V. Kuchař, The Problem of Time in Canonical Quantization of Relativistic Systems, in *Conceptual Problems of Quantum Gravity*, eds. A. Ashtekar and J. Stachel, Birkhäuser (1991).

- K. V. Kuchař, Time and interpretations of quantum gravity, in *Proceedings of the 4th Canadian Conference on General Relativity and Relativistic Astrophysics* (1992) [arXiv:gr-qc/9304012].

- S. Lloyd, Programming the Universe: A Quantum Computer Scientist Takes on the Cosmos, Vintage Books (2007).

- D. Marolf, Group averaging and refined algebraic quantization: Where are we now?, in *The Ninth Marcel Grossmann Meeting*, World Scientific (2002) [arXiv:gr-qc/0011112].

- C. W. Misner, K. S. Thorne, and J. A. Wheeler, Gravitation, W. H. Freeman (1973).

- E. Moreva, G. Brida, M. Gramegna, V. Giovannetti, L. Maccone, and M. Genovese, Time from quantum entanglement: an experimental illustration, Phys. Rev. A 89, 052122 (2014) [arXiv:1310.4691]. [CrossRef]

- O. Oreshkov, F. Costa, and Č. Brukner, Quantum correlations with no causal order, Nature Commun. 3, 1092 (2012). [CrossRef]

- D. N. Page and W. K. Wootters, Evolution without evolution: Dynamics described by stationary observables, Phys. Rev. D 27, 2885 (1983). [CrossRef]

- C. Rovelli, Time in quantum gravity: An hypothesis, Phys. Rev. D 43, 442 (1991).

- C. Rovelli, Quantum Gravity, Cambridge University Press (2004), Chapters 5–6.

- C. Teitelboim, Quantum mechanics of the gravitational field, Phys. Rev. D 25, 3159 (1982).

- T. Thiemann, Modern Canonical Quantum General Relativity, Cambridge University Press (2007).

- R. M. Wald, General Relativity, University of Chicago Press (1984).

- R. M. Wald, Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime and Black Hole Thermodynamics, University of Chicago Press (1994).

- E. Witten, Topological Quantum Field Theory, Commun. Math. Phys. 117, 353 (1988).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).