1. Introduction

Quantum mechanics is one of the most successful theories in the history of science, yet it exhibits a foundational asymmetry: time is treated as a classical external parameter, while space and matter are subject to quantization [

11,

36]. This asymmetry generates persistent conceptual and technical tensions, particularly when attempting to reconcile quantum theory with general relativity, where spacetime—including time—is dynamic and curved [

25]. Furthermore, paradoxes such as the measurement problem, the arrow of time, and the quantum-classical transition suggest that the conventional treatment of time may be fundamentally incomplete [

44,

52].

Building on Chronon Field Theory (CFT) [

28], which proposes a radical shift in temporal ontology by treating time as a dynamical, causal field—the “Real Now”—this work extends that framework into the quantum domain. In CFT, the flow of time is encoded in a smooth, unit-norm, future-directed vector field

on a Lorentzian manifold. All known interactions, including gravitation and gauge forces, emerge as geometric or topological deformations of this field.

We introduce Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM), a reformulation of quantum theory based on the intrinsic temporal geometry defined by . In this framework, quantum states are defined on hypersurfaces orthogonal to , and evolution proceeds with respect to the internal structure of the temporal flow. Quantization arises naturally from the topology of the Chronon field, yielding a geometric explanation for phenomena such as spin, statistics, and the Pauli exclusion principle.

In addition to providing a consistent merger with background-independent theories of spacetime, CQM offers novel resolutions to foundational problems in quantum mechanics. It reframes measurement, decoherence, and nonlocality as emergent phenomena tied to the causal and topological properties of time. The theory also makes concrete, testable predictions—ranging from modified scattering amplitudes and gravitational wave signatures to precision quantum effects—that distinguish it from standard quantum mechanics [

37].

To support this theoretical structure, we present numerical simulations of the Chronon field, demonstrating the spontaneous formation, motion, and annihilation of topologically quantized solitons. These solitons exhibit integer winding numbers and stable dynamics, aligning with the theoretical expectations for fermionic and bosonic precursors in the CQM framework.

This paper develops the mathematical foundations of CQM, explores its conceptual implications, and outlines a roadmap for empirical tests. We begin with a review of the Chronon field and its unifying role in physical interactions, followed by a construction of quantum theory over Chronon-defined foliations. We then derive topological quantization conditions, present simulation results, examine experimental signatures, and conclude with future directions in theory, computation, and testability.

2. Quantum States as Functionals of Temporal Flow

In Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM), quantum states are defined not on a fixed spacetime background with an external time parameter

t, but relative to the local configuration of the Chronon field

, which encodes the physical flow of time [

39,

41]. This section formalizes the structure of Hilbert spaces, observables, and dynamics in a framework where the Real Now,

, plays an active dynamical role [

5,

36].

Figure 1.

Conceptual structure of Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM). The Chronon field defines a foliation of spacetime into hypersurfaces , with quantum states evolving along the flow. Observables are defined relative to this temporal structure, grounding quantum dynamics in a physically meaningful time field.

Figure 1.

Conceptual structure of Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM). The Chronon field defines a foliation of spacetime into hypersurfaces , with quantum states evolving along the flow. Observables are defined relative to this temporal structure, grounding quantum dynamics in a physically meaningful time field.

2.1. Chronon-Sliced Configuration Space

Let

denote a hypersurface of simultaneity defined by the foliation induced by the Chronon field

[

28]. That is,

is orthogonal to the integral curves of

at Chronon proper time

. On each slice, quantum states are defined as functionals

where

denotes generic matter or gauge fields defined on

, and

is held fixed, defining the foliation and local causal structure [

22].

2.2. Hilbert Space Structure

We define a Chronon-dependent Hilbert space

by equipping the space of functionals with an inner product:

where

is the field-space measure on a fixed Chronon hypersurface. Importantly, this inner product depends parametrically on

, and the overall Hilbert space structure becomes a fiber bundle over the Chronon configuration space [

43].

2.3. Chronon-Compatible Observables

Operators

acting on

must be local functionals of

and their conjugate momenta, defined on

. To preserve covariance with respect to Chronon dynamics, we require observables to satisfy:

ensuring compatibility with the foliation structure. Observables depending explicitly on

(e.g., stress-energy or current densities) must be treated with care due to operator ordering ambiguities.

2.4. Effective Schrödinger Evolution

Although the full dynamics of

involve coupled evolution of both

and

, we can isolate the matter field evolution in a semi-classical Chronon background by defining a generalized Schrödinger equation:

where

parametrizes proper time along the Chronon foliation, and

is the Hamiltonian operator derived from the Chronon-constrained Lagrangian. This description parallels the Tomonaga–Schwinger formalism but grounds the foliation in a physically dynamical field [

39,

41].

2.5. Chronon Field Quantization Perspective

For a complete quantum description,

itself must be promoted to an operator-valued field, with quantum states obeying:

and evolution governed by a joint Chronon-matter Hamiltonian. The structure of such a theory will be developed in later sections, particularly those focused on topological quantization and field-theoretic path integrals over temporal geometries [

37].

3. Topological Quantization and the Emergence of Spin

In Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM), particles are not introduced as fundamental excitations of quantized fields on spacetime, but as

topological solitons in the Chronon field

[

29]. These solitons carry quantized topological charges associated with the nontrivial mapping of the temporal flow field into a compact internal configuration space. In this section, we show how spin and fermionic statistics emerge naturally from these topological properties [

33,

35].

3.1. Chronon Solitons and Topological Classes

We consider static, finite-energy solutions

with nontrivial winding around compactified spatial hypersurfaces. Since the Chronon field maps a compactified 3D spatial manifold (topologically

) into a target manifold of unit-norm timelike vectors (homotopy-equivalent to

), the relevant topological invariant is the third homotopy group:

Each particle species corresponds to a distinct topological class labeled by an integer winding number

. These classes are stable under smooth deformations, giving rise to solitons with conserved topological charge [

30].

3.2. Spin from Temporal Twisting

The key insight is that half-integer spin arises from antisymmetric twisting of the Chronon field configuration under 360-degree spatial rotations. Let denote a soliton solution with winding number . Under a full spatial rotation, the soliton configuration returns to its initial field values up to a sign:

Figure 2.

Visualization of topological solitons in the Chronon field. The mapping of spatial hypersurfaces () to the unit-timelike vector field admits nontrivial winding numbers. Solitons with exhibit spin- behavior, returning to minus themselves under rotation, while even windings (, etc.) exhibit bosonic periodicity.

Figure 2.

Visualization of topological solitons in the Chronon field. The mapping of spatial hypersurfaces () to the unit-timelike vector field admits nontrivial winding numbers. Solitons with exhibit spin- behavior, returning to minus themselves under rotation, while even windings (, etc.) exhibit bosonic periodicity.

which reflects the transformation behavior of spin-

representations of the rotation group. This anti-periodicity under

rotation is a hallmark of fermionic spin [

18].

3.3. Pauli Exclusion from Topological Interference

When two identical Chronon solitons overlap, their winding configurations may destructively interfere unless they are spatially distinguishable. This results in an effective exclusion principle:

This behavior reproduces the fermionic statistics of electrons and quarks without requiring postulated anticommutation relations [

10].

3.4. Bosonic Modes as Integer Windings

In contrast, solitons with even winding number exhibit periodicity under full rotations and can co-locate without destructive interference. These configurations behave as bosons. Massless gauge bosons, such as the photon, are interpreted as phase-coherent excitations of without localized topological charge.

3.5. Spin Quantization Without Operators

Traditional quantum mechanics introduces spin via abstract operator algebras and representation theory. In CQM, spin emerges from the global topological structure of time flow. Quantization is enforced by:

Topological stability: preventing decay into trivial configurations.

Homotopy classification: dictating allowed charge sectors.

Dynamical soliton coherence: ensuring propagation of quantized spin modes.

This framework links spin to the geometry of time itself and suggests an intrinsic origin of quantum numbers from the topology of temporal flow.

3.6. Outlook

This topological interpretation of spin motivates deeper exploration of higher homotopy groups, non-Abelian defects, and possible extensions to supersymmetric or braided statistics [

8]. In subsequent sections, we will analyze how this framework contributes to resolving foundational paradoxes and informs the construction of Chronon path integrals over nontrivial topologies.

4. Resolution of Quantum Paradoxes

Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM) offers a new lens through which several longstanding paradoxes in quantum theory can be examined and potentially resolved. By replacing an external, non-dynamical time parameter with a locally causal, topologically active field

, CQM grounds quantum evolution and measurement in a physically meaningful temporal structure. Below, we analyze how this reformulation addresses key interpretational challenges [

11,

37].

4.1. The Measurement Problem

In standard quantum mechanics, the measurement problem arises from the apparent contradiction between unitary evolution and wavefunction collapse. CQM reframes this issue:

Decoherence as Chronon Field Interaction: Classical outcomes emerge from local decoherence events driven by entanglement between matter fields and fluctuations in the Chronon field [

38,

52]. Collapse is not a fundamental process, but an effective result of Chronon field reconfiguration.

No Need for External Observer: Since temporal evolution is encoded intrinsically in

, measurement does not require a privileged classical observer or external clock [

17].

4.2. Arrow of Time

The asymmetry of time—ubiquitous in thermodynamics and cosmology—is inexplicable in time-reversal invariant formulations. CQM provides a natural explanation:

4.3. Quantum Nonlocality

Entanglement and Bell-type correlations are typically viewed as acausal or superluminal phenomena. In CQM:

4.4. The Problem of Time in Quantum Gravity

Canonical quantum gravity struggles with a “frozen formalism,” where time is absent from the Wheeler–DeWitt equation. CQM resolves this issue directly:

4.5. Collapse, Causality, and Consistency

CQM enforces causal propagation by construction:

Collapse Propagates Along Chronon Cones: Any reconfiguration of the quantum state (e.g., due to measurement) propagates within the causal structure determined by , ensuring no superluminal effects.

Objective Consistency: Observers defined on Chronon foliations will agree on measurement outcomes, modulo local fluctuations, preserving empirical consistency without appealing to observer-centric models.

4.6. Toward a Unified Interpretation

CQM invites a new interpretational stance:

Temporal Realism: Time is real, dynamic, and structured.

Solitonic Ontology: Particles are coherent topological features of temporal flow.

Measurement as Coherence Breakdown: Observations correspond to localized Chronon dephasing events.

These features suggest that many quantum paradoxes arise from mischaracterizing time as external and passive. By restoring time as an active, physical quantity, CQM offers coherent and natural resolutions to foundational issues in quantum theory.

5. Path Integral over Chronon Topologies

In Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM), the path integral formulation acquires a fundamentally new character: integration is not over fixed spacetime geometries with externally imposed dynamics, but over dynamically generated temporal flows

and matter fields

that co-evolve. The Chronon field serves as the scaffolding for defining causal structure, simultaneity, and quantum amplitudes. This section outlines the generalized path integral formalism [

6,

15].

5.1. Configuration Space of Temporal Flows

The total configuration space

includes all smooth, unit-norm, future-directed vector fields

modulo gauge equivalence:

where

represents residual diffeomorphism symmetries preserving foliation structure. Each element in

defines a unique foliation and therefore a distinct causal slicing [

22].

5.2. Total Path Integral Structure

The full quantum amplitude is given by:

where:

is the Chronon action, including kinetic, potential, and topological terms,

is the matter and gauge field action defined relative to the foliation induced by .

5.3. Topological Sectors and Solitonic Contributions

The path integral naturally decomposes into disjoint topological sectors

classified by

:

where

is a topological phase and

n labels the winding number of solitonic Chronon configurations. These sectors give rise to quantized particle species and spin [

29,

35].

5.4. Foliation-Covariant Measures

The path integral measure respects Chronon foliation symmetry:

is defined on hypersurfaces orthogonal to ,

Gauge fixing of temporal diffeomorphisms must preserve foliation coherence,

Fadeev–Popov ghosts may be required to regulate gauge redundancies [

20].

5.5. Semiclassical Approximation and Instantons

In the semiclassical limit, the dominant contributions to

arise from stationary points of the action—Chronon instantons:

These instantons encode soliton creation, annihilation, and tunneling processes between topologically distinct Chronon vacua [

14].

5.6. Toward a Topological Quantum Field Theory (TQFT)

CQM shares structural similarities with TQFTs:

Observables are topological invariants of ,

Transition amplitudes depend only on homotopy class,

Nonlocal correlation functions emerge from shared Chronon topology.

Future work may formalize the Chronon path integral in the language of cobordisms and TQFT categories, potentially linking CQM to low-energy effective theories of quantum gravity and early-universe cosmology [

48].

6. Quantization of the Chronon Field

While the Chronon field

plays a foundational role in CQM—as both a generator of causal structure and a carrier of topological charge—most of the present formalism treats it as a classical or semiclassical background. To complete the theory and ensure full consistency with quantum principles,

must itself be rigorously quantized [

16,

20].

A formal operator quantization of

requires promoting it and its conjugate momentum

to operators on a joint Hilbert space:

where

is the projection operator preserving unit-norm and future-directed constraints.

The Hamiltonian governing joint matter–Chronon evolution becomes:

with cross-coupling terms mediating feedback between temporal flow and quantum observables. Operator ordering and gauge constraints must be handled carefully to ensure anomaly cancellation and covariance under reparameterizations of the foliation [

2].

An equivalent formulation can be pursued through the path integral:

where the Chronon action includes both kinetic and topological terms:

Quantization then involves summing over smooth, unit-norm vector fields, with distinct topological sectors labeled by

. This introduces nonperturbative effects and soliton tunneling, potentially captured by Chronon instantons [

14,

48].

In future work, the quantization of must be carried out using either a canonical Dirac constraint analysis or covariant BRST techniques adapted to foliation-dependent geometries. Care must also be taken to ensure that the resulting quantum theory preserves unitarity, causality, and background independence—hallmarks of a consistent quantum spacetime theory.

7. Gauge Redundancy and Covariance in Chronon Dynamics

Chronon Quantum Mechanics introduces a dynamical time-like vector field

to generate a physically meaningful foliation of spacetime. At first glance, this appears to violate general covariance, since it selects a preferred slicing. However, this selection is not imposed arbitrarily but emerges from the dynamics of

itself, much like a Higgs field selects a vacuum direction in gauge space. Thus, general covariance is not broken explicitly, but

spontaneously broken by the vacuum configuration of the Chronon field [

36,

42].

More formally, the full configuration space includes all smooth, future-directed, unit-norm vector fields:

This space is invariant under diffeomorphisms, and different Chronon configurations correspond to physically distinct but gauge-equivalent states. Fixing a particular foliation is akin to choosing a gauge slice in this space.

In the path integral formalism, this is made explicit by integrating over all

configurations modulo diffeomorphisms:

A Fadeev–Popov procedure may be employed to define the functional measure consistently. Gauge-fixing conditions, such as choosing hypersurfaces orthogonal to

, must be handled with care to preserve consistency and avoid spurious degrees of freedom [

20].

Importantly, the observable content of the theory remains coordinate-independent: predictions depend on the topological and dynamical structure of , not on coordinate choices. This maintains the spirit of general covariance, reinterpreted in a background-dynamical setting.

Thus, CQM offers a novel approach to background independence: not by erasing structure, but by making that structure physical and dynamical. Chronon covariance is preserved at the level of the full theory, even though individual solutions define a preferred temporal frame.

8. Emergence of Gauge Dynamics and Yang–Mills Structure

While the previous discussion outlined how Standard Model (SM) gauge symmetries may arise from deformations of the Chronon field

, it remains to show how gauge dynamics—specifically the Yang–Mills action—can emerge from the Chronon field’s geometric structure [

6,

32].

We begin by observing that local symmetry transformations of

under internal rotations (preserving the norm constraint) generate effective connection forms. For example, define a local orthonormal frame

adapted to

, with

Then the residual symmetry transformations of

under internal rotations generate a gauge group structure. Infinitesimal deformations correspond to a Lie-algebra valued connection:

where

are generators of

embedded in the internal symmetry space of the Chronon geometry [

26].

The curvature two-form

derived from

then defines a gauge field strength tensor:

with associated Yang–Mills action:

In the Chronon context, this action is not fundamental, but emerges as an effective field theory describing collective excitations of the underlying temporal geometry. The dynamics of

in topologically nontrivial configurations generates curvature in the frame bundle, which acts as gauge curvature in the low-energy limit [

2].

The structure group is selected by the stable deformation modes of the Chronon vacuum. Each gauge sector corresponds to a different class of non-integrable deformations in the fiber bundle over spacetime defined by .

Thus, the Yang–Mills dynamics of the Standard Model can be understood as the low-energy limit of geometric excitations in the temporal structure defined by the Chronon field. This provides a mechanism—though not yet a full derivation—for recovering the SM gauge terms from Chronon geometry.

Future work will formalize this correspondence using Cartan geometry, coset models, or effective Lagrangian methods [

40].

9. Emergence of the Standard Model

Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM), grounded in the dynamics and topology of the temporal flow field

, provides a geometric substrate from which the gauge structure and matter content of the Standard Model (SM) can emerge. In this section, we outline how effective field degrees of freedom, internal symmetries, and particle spectra arise from deformations and excitations of the Chronon field [

7,

19,

28].

9.1. Gauge Interactions as Chronon Deformations

The internal symmetry groups of the SM can be interpreted as emergent properties of local and global distortions of :

U(1) Electromagnetism: Phase rotations of around its local direction define an emergent electromagnetic gauge field , with dynamics derived from Chronon vorticity.

SU(2) Weak Interaction: Non-Abelian twisting and shear modes in the Chronon fiber structure induce effective SU(2) gauge fields, with spontaneous symmetry breaking linked to localized Chronon torsion.

SU(3) Color: Topologically confined temporal flux tubes bind solitons into color-neutral bound states, mimicking the confinement behavior of quantum chromodynamics (QCD) [

47].

9.2. Fermionic Matter from Soliton Topology

Standard Model fermions correspond to topologically nontrivial soliton sectors of the Chronon field:

Spin-: Emerges from

winding of

as described in

Section 3.

Flavor and Generation Structure: Different classes of soliton perturbations—distinguished by asymptotic structure, shape modes, or internal degrees of freedom—yield families of particles.

Charge Quantization: Coupling to emergent gauge fields enforces quantized charges, consistent with the anomaly structure of the SM.

9.3. Mass Generation and the Higgs Analogue

Mass terms in the SM arise through spontaneous symmetry breaking. In CQM:

9.4. Unification at High Energy

CQM suggests a deeper unity beneath the SM structure:

Gauge interactions, matter, and spacetime emerge from the same topological degrees of freedom in .

Running couplings and symmetry restoration at high energies correspond to coherence transitions in the Chronon field.

Gravity is encoded as global curvature of the flow lines, potentially linking to quantum gravity scenarios.

9.5. Effective Field Theory Limit

In the low-energy limit, when

is approximately uniform and perturbative, the Chronon soliton picture reduces to the standard formulation of QFT:

This ensures agreement with all known experimental data while predicting novel corrections in regimes where deviates significantly from classical coherence.

9.6. Implications for BSM Physics

CQM may account for or motivate extensions of the SM:

Chronon dynamics thus provide a fertile foundation for both reproducing and extending the Standard Model within a temporally grounded quantum ontology[

28].

10. Universal Unification via Temporal Topology

Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM) proposes a novel model of unification that is fundamentally distinct from traditional Grand Unified Theories (GUTs). Instead of requiring that different interactions merge only at extremely high energy scales through renormalization group flow, CQM posits that all observed forces and matter content originate from a single, universal structure: the topological and geometric configurations of the Chronon field

[

28,

49].

In this picture, gauge interactions, gravitational dynamics, and matter fields are not separate entities but different manifestations of Chronon geometry:

Gauge Fields: Emergent from local twisting, shearing, or phase rotation of , interpreted as connections on fiber bundles induced by the Chronon foliation.

Fermions: Topological solitons characterized by nontrivial winding in

, yielding quantized spin and statistics [

29].

Spacetime Geometry: Derived from the global curvature and coherence of

flow lines, encoding gravitational behavior [

37].

The key insight is that these features are present not only at high energies, but at all energy scales. Chronon topology provides a persistent scaffold from which low-energy physics inherits structure. This leads to what may be called structural unification:

All known physics arises from deformations, solitons, and excitations of a single temporal field——whose geometric and topological character governs the behavior of matter, forces, and spacetime across all scales.

While effective field descriptions such as the Standard Model or General Relativity may appear disjoint, they are in CQM merely low-energy approximations to distinct regimes of Chronon dynamics. This perspective offers several key advantages:

No requirement for unification energy thresholds or grand unification Higgs fields.

Topological robustness of charges and spins independent of energy scale.

Natural explanation for why unification appears broken at low energies: different solitonic sectors coexist.

Predictive power: deviations from Standard Model behavior can arise at any scale via Chronon decoherence or nontrivial topology.

This universal unification reframes the traditional search for a “Theory of Everything” as the geometric and topological classification of stable structures in temporal flow. Rather than seeking additional fields or symmetries, the task becomes understanding how all known physical phenomena are encoded in the rich structure of time itself.

11. Experimental Predictions and Tests

Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM) is not merely a metaphysical reinterpretation of quantum theory; it makes concrete, testable predictions that distinguish it from standard formulations. These arise from the topological, dynamical, and foliation-dependent structure of the Chronon field

, and can be probed in high-energy experiments, astrophysical observations, and precision quantum systems [

1,

45].

11.1. Scattering Amplitude Modifications

Chronon-induced corrections to the effective metric and gauge couplings manifest in scattering processes:

Bhabha Scattering: Deviations in angular distributions of

scattering on the order of

, measurable via luminosity-dependent asymmetries at the ILC [

21].

e–e– Scattering: Suppression of identical fermion overlap amplitudes in localized regions with Chronon vorticity, leading to violation of standard antisymmetry at length scales .

Jet Angular Correlations: Anisotropic broadening of QCD jets due to residual Chronon flux tubes, with expected distortions at the level in high-multiplicity events.

11.2. Topological Signatures in Cosmology

Chronon solitons and instantons in the early universe may leave imprints observable today:

11.3. Precision Quantum Systems

Chronon field fluctuations at low energies may affect delicate quantum interference phenomena:

Neutron Interferometry: Time-of-flight variations across differing Chronon-aligned paths in rotating or boosted frames.

Atomic Clocks: Frequency shifts at the level due to local decoherence in , detectable via differential clock networks or optical lattice comparisons.

Quantum Optics: Reduction in Bell-inequality violations at the

level due to partial misalignment of entangled photon wavepackets with background Chronon direction [

38].

11.4. Predictions for Beyond Standard Model Phenomena

CQM opens new avenues for BSM exploration:

Neutrino Oscillations: Modulations in oscillation probabilities from Chronon torsion couplings; expect energy-dependent deviations in long-baseline experiments.

Axion-like Fields: Scalar perturbations in the norm generate pseudo-scalar modes behaving like axions, with coupling scales near .

Violation of Lorentz Symmetry: Preferred foliation effects causing sidereal modulation in SME coefficients at the

level [

27].

11.5. Chronon Detection Strategies

While is not directly observable, its influence can be inferred through:

Coherence Measurements: Frame-dependent loss of quantum coherence in rotating interferometers (e.g., neutron or atom interferometers with baseline ).

Anisotropy Probes: Orientation-sensitive experiments (e.g., torsion balance, NMR gyroscope arrays) may detect spatial alignment of .

Temporal Flux Imaging: Analog systems in condensed matter (e.g., spin ice, time-crystal analogues) may simulate emergent Chronon-like flows.

Figure 3.

Experimental domains for testing Chronon Quantum Mechanics. Observable effects arise in high-energy scattering (e.g., angular deviations), cosmological probes (e.g., gravitational wave background), precision quantum systems (e.g., atomic clocks, interferometers), and symmetry violation searches. This summary highlights where deviations from standard quantum theory are most likely to emerge.

Figure 3.

Experimental domains for testing Chronon Quantum Mechanics. Observable effects arise in high-energy scattering (e.g., angular deviations), cosmological probes (e.g., gravitational wave background), precision quantum systems (e.g., atomic clocks, interferometers), and symmetry violation searches. This summary highlights where deviations from standard quantum theory are most likely to emerge.

11.6. Summary of Observable Effects

12. Intrinsic Finiteness and UV Regularization

One of the defining advantages of Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM) over conventional quantum field theories lies in its intrinsic finiteness. In standard formulations, quantum fields are quantized over point-like degrees of freedom, leading to ultraviolet (UV) divergences that require renormalization through ad hoc counterterms and regularization procedures [

50]. By contrast, CQM avoids these issues at the structural level[

28].

Particles in CQM arise not as point-like quanta, but as topological solitons—smooth, finite-energy field configurations of the Chronon field

, classified by

[

29]. These solitons possess an extended spatial structure, effectively smearing interactions over finite regions of spacetime. As a result, loop amplitudes and self-interactions are regularized geometrically, not algebraically.

This solitonic framework functions as a natural UV cutoff, rendering the theory finite without breaking unitarity or requiring auxiliary fields. In this sense, CQM shares conceptual similarities with finite topological quantum field theories (TQFTs), where amplitudes are topologically protected from divergence [

48].

Furthermore, the absence of singularities at short distances improves both mathematical consistency and the feasibility of coupling to gravity. The smoothness of Chronon solitons may also alleviate problems such as black hole singularities and cosmological initial conditions, pointing toward a deeper geometric regularization principle underlying all of physics [

4].

13. Numerical Simulations of Chronon Solitons

To probe the dynamical implications of Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM), we conducted numerical simulations of soliton formation, interaction, and annihilation in a discretized temporal flow field

. These simulations provide computational evidence for the emergence of topologically quantized excitations, their coherent trajectories, and interaction rules—corroborating the theoretical predictions developed in

Section 3 and

Section 5.

13.1. Simulation Setup and Methodology

The Chronon field

is modeled as a smooth, unit-norm, future-directed vector field on a 3D spatial lattice evolving over discrete time steps. The field is initialized with random perturbations around a uniform temporal flow

, and evolved using a constrained relaxation scheme to minimize a field energy functional:

where

enforces the unit-norm constraint and

is a finite-difference spatial derivative.

Localized structures—referred to as “blobs”—emerge and stabilize with quantized topological winding. Each blob is tracked via its center of mass and local Chronon vorticity. In principle, a full topological invariant associated with mappings

would be computed from the 3D surface integral:

which characterizes the homotopy class in

. However, this requires access to the full 4-vector structure of

over a compactified spatial hypersurface.

In our simulations, we employed a practical and computationally robust method based on planar phase winding around the local blob center in the

x–

y plane at fixed

. Let

be the azimuthal angle of the projected Chronon vector. Then the effective winding number is estimated as:

where the path integral is discretized over

angular segments forming a circle of radius

r around the blob. This method captures

winding in the planar field and provides a reliable integer-valued classification of localized topological structures, which we interpret as solitonic particle analogs.

Readers may reproduce these simulations using a 3D lattice of size (e.g., ), iterating field updates via gradient descent or Langevin dynamics with small noise. Visualization is performed using isosurfaces of vorticity and blob centroid tracking.

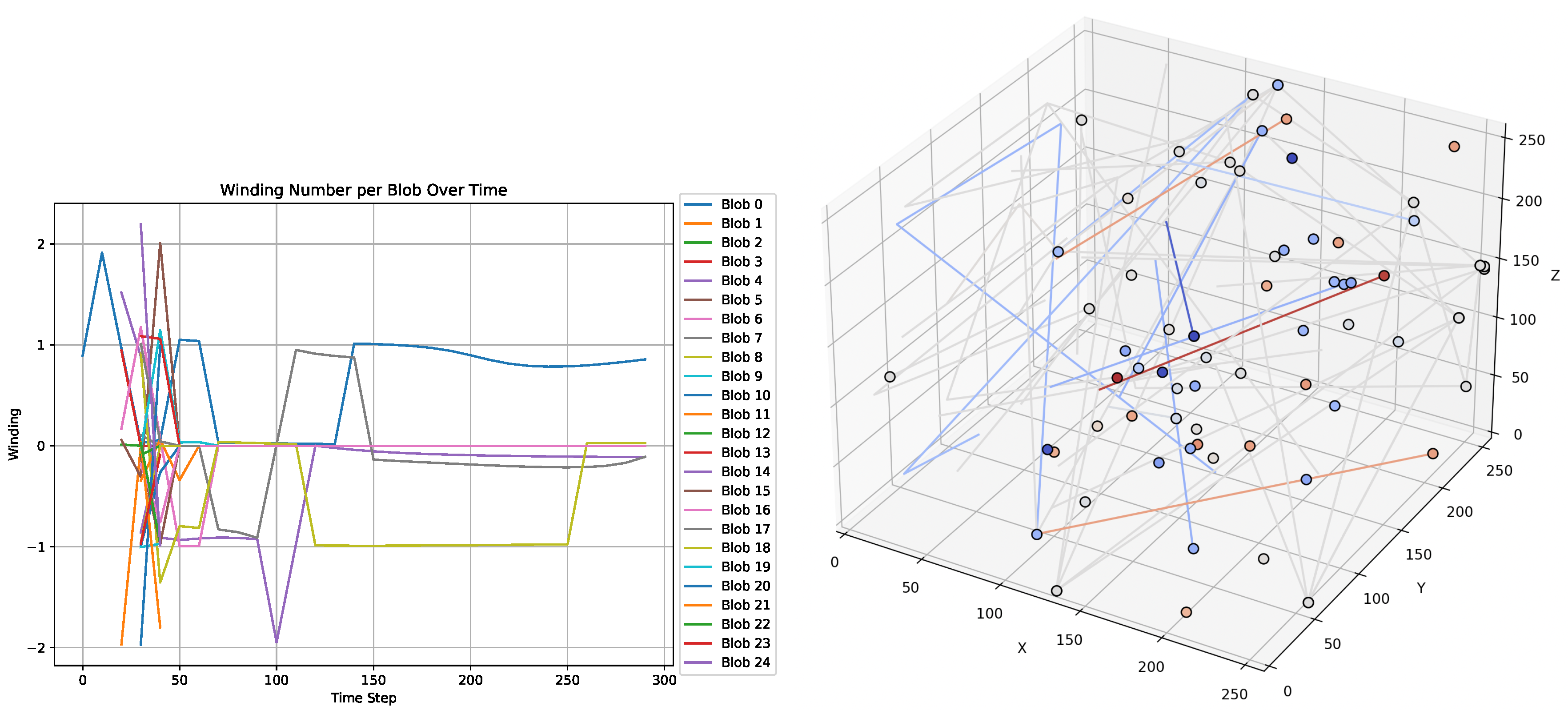

13.2. Soliton Dynamics and Winding Quantization

Blobs with winding numbers

were frequently observed. Higher winding configurations were less stable and typically fragmented. Trajectories were recorded, showing coherent propagation over time.

Figure 5 (left) illustrates time evolution of winding numbers for selected blobs, while (right) shows their 3D paths.

Figure 4.

Snapshots of the Chronon field at various time steps, showing the planar phase angle at the central slice of a lattice. Initially random configurations evolve into coherent topological domains, consistent with solitonic ordering.

Figure 4.

Snapshots of the Chronon field at various time steps, showing the planar phase angle at the central slice of a lattice. Initially random configurations evolve into coherent topological domains, consistent with solitonic ordering.

Figure 5.

Left: Time evolution of winding numbers of spontaneously generated blobs which are interpreted as topological solitons. Right: Sample 3D trajectories of solitons exhibiting quantized transport and coherence.

Figure 5.

Left: Time evolution of winding numbers of spontaneously generated blobs which are interpreted as topological solitons. Right: Sample 3D trajectories of solitons exhibiting quantized transport and coherence.

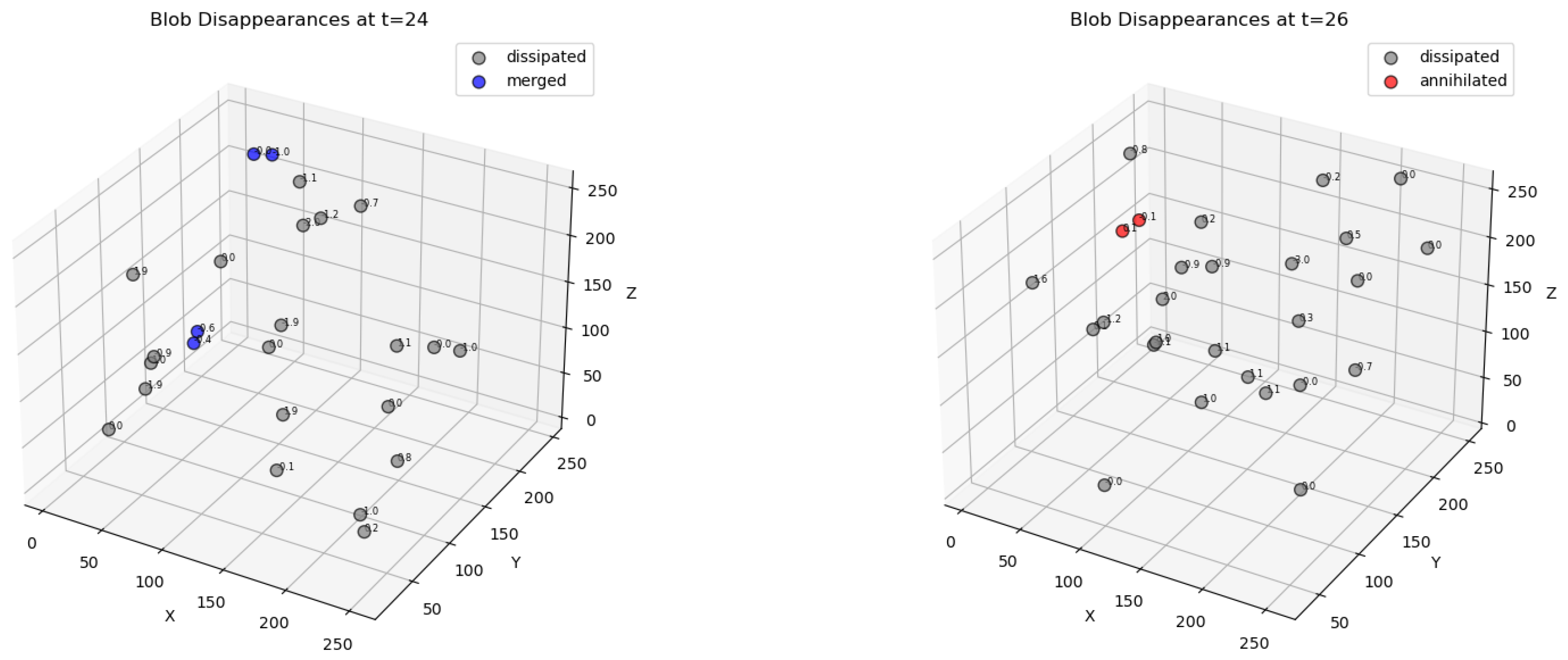

13.3. Interaction Rules and Annihilation Events

Annihilation events were identified where blobs of opposite winding number approached, interacted, and disappeared.

Figure 6 visualize the spatial configuration of such events. No such dissipation occurred for same-sign solitons, consistent with topological charge conservation.

13.4. Topological Repulsion and Quantum Statistics

A notable observation was the apparent exclusion behavior of blobs with or : such pairs were never observed to co-locate or approach below a threshold distance. This suggests an emergent repulsive interaction—consistent with a fermionic interpretation rooted in the antisymmetric topology of spin- solitons.

By contrast, neutral solitons () and even-winding solitons () showed clustering and overlapping trajectories. This behavior supports the identification of as a candidate for bosonic modes.

13.5. Interpretation and Outlook

These simulations validate key predictions of CQM:

Winding number is locally quantized and globally conserved.

Solitons follow coherent trajectories consistent with topological charge.

Same-sign blobs repel, consistent with fermionic exclusion.

Opposite-sign blobs annihilate, consistent with topological neutrality.

The methods are reproducible and open to further refinement. Future work will incorporate full Chronon–matter coupling and extend simulations to curved backgrounds.

14. Conclusion and Future Work

Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM) offers a transformative reformulation of quantum theory, grounded in the dynamics and topology of a physically real temporal flow field . By elevating time from an external parameter to a dynamical, causal, and quantized field, CQM provides a unified geometric substrate from which spacetime, matter, interactions, and measurement processes naturally emerge.

This framework addresses several foundational challenges in physics:

It recasts quantum states as functionals over Chronon-defined foliations, replacing coordinate time with physical time.

It derives spin, statistics, and exclusion from topological soliton sectors in the temporal field.

It resolves the measurement problem, quantum nonlocality, and time asymmetry by embedding causality in the geometry of .

It reproduces gauge symmetries and matter content via geometric deformations of temporal flow, providing a path from Chronon Field Theory (CFT) to the Standard Model [

28].

It yields concrete, testable predictions across high-energy, cosmological, and precision quantum domains.

To substantiate these theoretical insights, we presented numerical simulations demonstrating the spontaneous formation, propagation, and interaction of quantized solitons in a discretized Chronon field. These simulations confirm the topological origin of quantum numbers and hint at emergent fermionic and bosonic behavior—strengthening the empirical grounding of the theory and offering a reproducible path for independent verification.

Future work should explore the following directions:

Chronon Quantum Mechanics represents a bold and coherent hypothesis: that time is not an abstract background parameter but the fundamental agent of physical law. By grounding quantum theory in the geometry and topology of temporal flow, CQM opens a new pathway toward unifying matter, forces, and consciousness under a common dynamical framework—experimentally accessible and mathematically robust.

Author Contributions

Bin Li is the sole author

Funding

This research received no external funding

Appendix A. Operator Algebra in Chronon Foliation

In this appendix, we formalize the operator structure in Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM), where quantum observables are defined relative to hypersurfaces

determined by the Chronon field

. The goal is to establish a consistent algebraic framework for field operators and their conjugate momenta that respects the causal structure imposed by

[

16,

20].

Appendix A.1. Canonical Quantization on Chronon Hypersurfaces

Let

denote a generic field (e.g., scalar, spinor, or gauge) defined on a fixed Chronon slice

. The conjugate momentum

is defined by

where

is the directional derivative along the Chronon field. The equal-

canonical commutation relations take the form:

where

is the induced delta function on

defined by the foliation [

3].

Appendix A.2. Chronon Field Operators

To extend quantization to the Chronon field itself, we define operator-valued vector fields

and their associated momenta

. The algebra is constrained by the normalization condition:

and the commutation relations must preserve this constraint:

where

is a projection operator onto the spacelike directions orthogonal to

.

Appendix A.3. Foliation Covariance and Time Evolution

The Hamiltonian governing evolution along Chronon time

is a functional

defined on

. The Heisenberg equations take the form:

with

capturing explicit

-dependence due to background variation in

[

37].

Appendix A.4. Commutators and Causality

To ensure causality with respect to the Chronon field, operator commutators must vanish for spacelike-separated points relative to

:

This condition replaces the usual light-cone structure with a -adapted causal cone.

Appendix A.5. Gauge Constraints and Chronon Compatibility

In the presence of gauge fields

, the constraints must commute with

to preserve foliation invariance:

where

are Gauss law operators or gauge-fixing constraints. This ensures that gauge symmetry and Chronon causality coexist consistently.

Appendix A.6. Summary

The operator algebra in CQM is intrinsically foliation-dependent and encodes causal and topological structures induced by . Canonical quantization proceeds slice by slice, with Chronon-compatible commutation relations preserving both causality and background covariance. This formalism paves the way for non-perturbative and path integral quantization of the full Chronon–matter system.

Appendix B. Canonical vs Path Integral Chronon Quantization

Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM) supports two complementary quantization approaches: canonical quantization defined on Chronon foliation slices, and a generalized path integral over temporal geometries. In this appendix, we compare these two frameworks and clarify their equivalence and domain of applicability [

16,

20].

Appendix B.1. Canonical Quantization

Canonical quantization proceeds by selecting a hypersurface

orthogonal to

, promoting fields and their conjugate momenta to operators with equal-

commutation relations:

The system evolves via a Hamiltonian

that depends on the local configuration of

. Evolution is governed by:

This approach is well-suited for:

Perturbative analysis around semiclassical backgrounds,

Canonical constraint algebra and gauge fixing [

22],

Explicit construction of Chronon-adapted Hilbert spaces.

Appendix B.2. Path Integral Quantization

Alternatively, the full quantum amplitude can be expressed as a double path integral:

This formulation:

Sums over all admissible Chronon field histories,

Integrates over all matter field configurations constrained to -defined foliations,

Encodes topological transitions and tunneling events (e.g., soliton–antisoliton creation) [

48].

It is particularly powerful for:

Appendix B.3. Equivalence via Chronon Time Slicing

Under appropriate gauge fixing and choice of foliation, both formulations yield equivalent predictions. The path integral can be discretized into a product of canonical transition amplitudes:

recovering the canonical evolution kernel [

15].

Appendix B.4. Handling Chronon Dynamics

Unlike conventional QFT, where spacetime is fixed, CQM requires quantization of itself:

In canonical quantization, and are operator-valued fields.

In path integral quantization, contributes to the functional measure and action.

Their dynamics introduce new degrees of freedom and require regularization of the Chronon field space [

6].

Appendix B.5. Anomalies and Gauge Consistency

Both approaches must preserve Chronon gauge invariance:

Canonically, this appears as constraint closure under Poisson (or Dirac) brackets.

In the path integral, anomalies may arise from measure non-invariance under -dependent transformations.

Ensuring anomaly cancellation is critical for physical consistency.

Appendix B.6. Summary

Canonical and path integral formulations of CQM are complementary. The canonical approach emphasizes local operator structure and dynamical evolution, while the path integral encodes global topological information and non-perturbative effects. Together, they provide a robust dual framework for exploring the quantum dynamics of temporal geometry and matter.

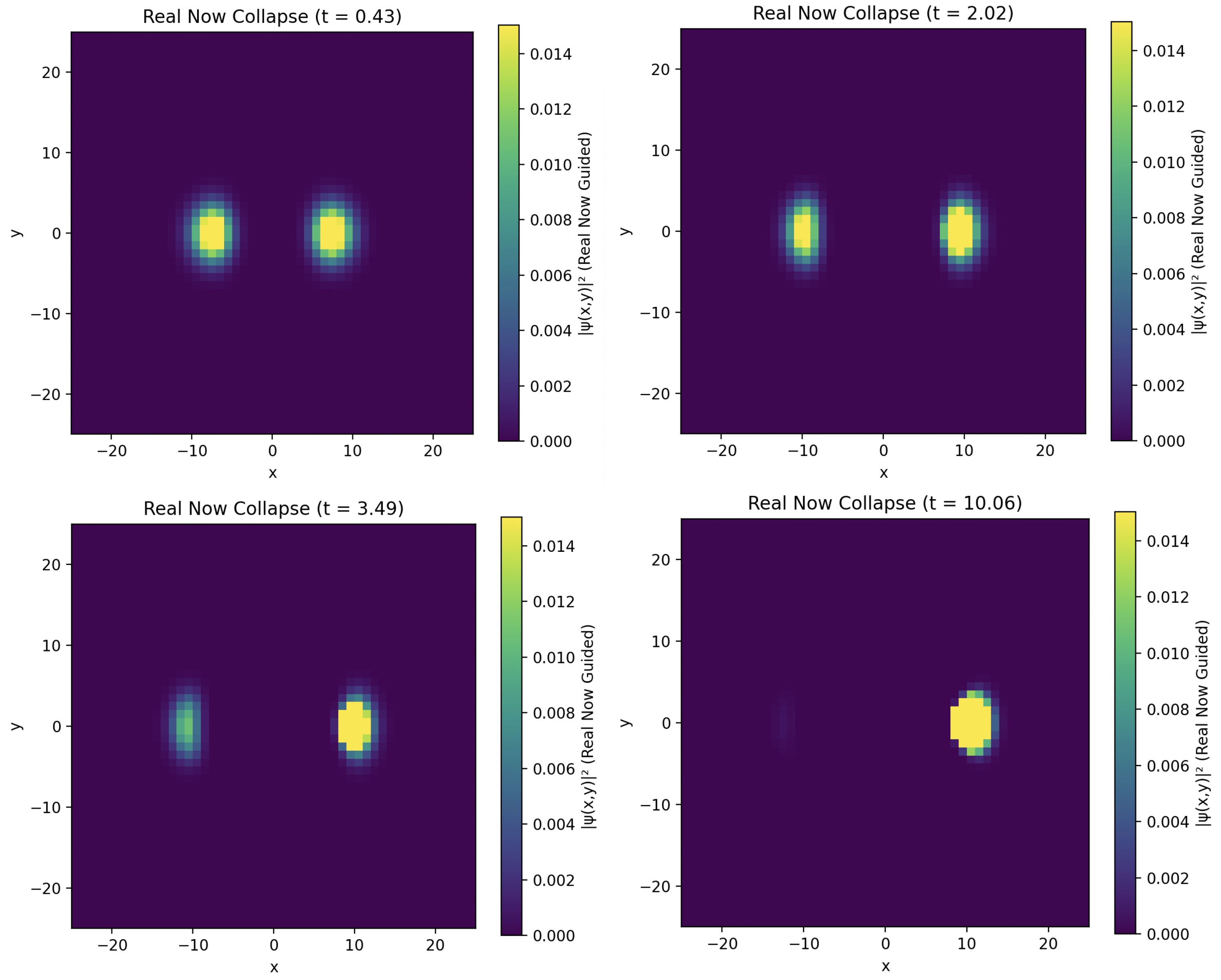

Appendix C. Simulations of Chronon-Mediated Quantum Collapse

In this appendix, we present a numerical framework for simulating quantum state collapse as an emergent effect of Chronon field dynamics in Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM). The goal is to demonstrate how classical measurement outcomes can arise from temporal decoherence governed by the structure and evolution of a physically real time-orienting field , referred to as the Real Now.

Appendix C.1. Model Setup and Initial Conditions

We consider a two-dimensional spatial domain where a quantum field

evolves in the presence of a semiclassical Chronon field

. In contrast to prior stochastic models, here

is treated as a deterministic foliation field representing the direction and coherence of local temporal flow. The field is initialized with a spatial gradient that breaks global symmetry:

where

k controls the steepness of the temporal tilt across the

x-axis. This defines a coherent Real Now structure with a preferred causal orientation that evolves via self-interaction and coupling to

.

The quantum wavefunction is initialized as a symmetric superposition of two localized Gaussians centered symmetrically about the origin. No noise or external measurement agent is included; all dynamics are fully determined by local field interactions and time-oriented geometry.

Appendix C.2. Collapse Mechanism via Real Now Foliation

Collapse is modeled as the localization of the wavefunction into one temporally coherent region defined by the Chronon foliation. This process is mediated by two field-induced mechanisms:

Decoherence:

which suppresses amplitudes in temporally incoherent or high-curvature zones.

Confinement:

which energetically favors domains where

, corresponding to maximal coherence in temporal flow.

The combined effect selectively confines to a temporally preferred region defined by the Real Now, inducing collapse without stochasticity.

Appendix C.3. Numerical Scheme

The simulation uses a lattice-based finite-difference scheme with the following core components:

Chronon evolution via a nonlinear Proca-like equation without noise,

Gradient-based decoherence and domain wall confinement,

Bidirectional coupling between the field and the quantum amplitude ,

Renormalization of at each timestep to conserve total probability.

All parameters, such as the Chronon domain tension D, decoherence damping , coupling constant , and confinement strength , are chosen to ensure visible and stable collapse behavior within computational time constraints.

Appendix C.4. Simulation Results and Visualization

Figure A1 shows selected snapshots of

over the course of evolution. Initially symmetric, the wavefunction becomes increasingly suppressed on one side of the domain and ultimately localizes entirely into a single foliation-aligned region. This collapse arises dynamically through the nonlinear interaction with the temporally structured Chronon field.

Figure A1.

Chronon-guided collapse: evolution of at representative time steps. A symmetric initial superposition collapses deterministically into one Chronon-aligned region due to foliation-induced decoherence and temporal confinement. No stochastic noise is used.

Figure A1.

Chronon-guided collapse: evolution of at representative time steps. A symmetric initial superposition collapses deterministically into one Chronon-aligned region due to foliation-induced decoherence and temporal confinement. No stochastic noise is used.

Appendix C.5. Interpretation and Theoretical Implications

This simulation demonstrates that wavefunction collapse can emerge as a deterministic, dynamical process governed by the causal foliation structure of the Chronon field. In this framework, the Real Now functions as an ontological engine of causal structure. Collapse is not a random outcome of stochastic decoherence but a temporal bifurcation event: a selection of one consistent temporal trajectory from among multiple potential ones, enforced by geometric asymmetry in the field .

This offers a concrete model of measurement and state reduction rooted in field dynamics rather than epistemic updates or environment-induced decoherence. It aligns with the Chronon Field Theory view that temporal coherence, not external observation, governs classical emergence.

Appendix C.6. Future Directions in Deterministic CQM

Future extensions of this simulation framework may include:

Simulations with topologically nontrivial initial Chronon configurations (e.g., vortex strings),

Generalization to 3+1D and relativistic Chronon dynamics,

Study of Born-rule recovery across ensemble realizations with deterministic but varied foliation seeds,

Exploration of the role of Chronon-induced curvature in gravitational decoherence,

Design of experimentally testable collapse asymmetries tied to time-foliation structure.

This deterministic Chronon collapse model provides a physically grounded, temporally causal alternative to standard quantum interpretations, rooted in the geometry and topology of time itself.

Appendix D. Continuous Collapse and the Double-Slit Experiment in CFT

Appendix D.1. Chronon Collapse as Continuous Temporal Selection

In Chronon Field Theory (CFT), wavefunction collapse is reinterpreted not as a discrete, observer-triggered event but as a continuous, local process governed by the structure and evolution of the real-time field . This field defines a physically instantiated direction of becoming—the Real Now—whose spatial and temporal gradients impose decoherence and drive the emergence of classical outcomes.

Collapse is therefore understood as the progressive suppression of quantum superpositions via local coupling to the Chronon field. The rate and localization of this suppression depend on the geometry and topology of . In regions where the Chronon field is smooth and coherent, quantum amplitudes may remain entangled across space. But where is large—e.g., near sharp temporal bifurcations, domain boundaries, or interaction sites—the wavefunction rapidly decoheres and becomes effectively classical.

Mathematically, the local decoherence rate can be written as:

which enters directly into the evolution of the quantum field

via damping and confinement terms. Collapse is thus not initiated by an observer or apparatus, but by the local structure of temporal flow itself.

Appendix D.2. Reinterpreting the Double-Slit Experiment

The double-slit experiment is a canonical case study in quantum measurement theory. In standard interpretations, the presence of a detector at one slit is said to “cause” collapse, preventing interference. In CFT, this phenomenon is reinterpreted as a natural consequence of Chronon field dynamics.

Appendix D.2.1. Case 1: No Detector Present

When no which-path detector is placed, the Chronon field

remains smooth across both slits. The quantum amplitude

propagates through both paths coherently. Since there are no sharp decohering gradients in

, no significant collapse occurs prior to the screen. Interference fringes form, and collapse is localized only at the detection surface, where

becomes highly nonlinear due to interaction with macroscopic detection media:

Appendix D.2.2. Case 2: Detector Placed at One Slit

Introducing a measurement device at one slit modifies the local Chronon geometry. The detector imposes its own internal time flow (as a classical system), creating a sharp bifurcation in

. This increases local decoherence rates and destroys superposition coherence at or near the slit, well before the particle reaches the screen:

Importantly, this occurs without invoking a subjective observer or discrete wavefunction collapse. Instead, the detector simply acts as a Chronon modulator, altering the structure of real time and thereby suppressing ’s delocalized evolution.

Appendix D.2.3. General Principle

The apparent discreteness of measurement-induced collapse in standard QM is, in the CFT framework, the visible macroscopic consequence of a continuous, geometry-driven suppression of quantum amplitudes. The timing and location of collapse are thus **not universal**, but **dynamically modulated** by the field .

Appendix D.3. Resolution of Apparent Paradox

While CFT posits that collapse is always ongoing, this does not mean that all coherence is destroyed immediately or uniformly. Instead:

Without a detector, the Chronon field remains coherent across the slits, allowing interference to manifest.

With a detector, the Chronon field is locally perturbed, introducing decoherence that collapses the wavefunction earlier.

This allows CFT to **reproduce all experimental results** of the double-slit setup, while offering a **deeper physical explanation** of why and how collapse occurs—grounded in the geometry of time rather than epistemic updates or observer intervention.

Appendix D.4. Implications and Testable Distinctions

CFT predicts that even in the absence of observers, wavefunction collapse occurs due to the ambient temporal structure. It also suggests the possibility of novel experiments:

Using time-asymmetric environments to modulate and influence collapse location,

Engineering materials or setups to suppress decoherence and extend coherence lengths,

Testing collapse timescales as a function of spatial curvature in .

These predictions differentiate CFT from conventional interpretations and make it amenable to empirical investigation as a theory of quantum temporal ontology.

Appendix E. Comparison Table: Standard QM vs CQM

This appendix provides a side-by-side comparison of key conceptual and structural differences between standard quantum mechanics (QM) and Chronon Quantum Mechanics (CQM). The comparison highlights the novel aspects of CQM and clarifies its implications for foundational physics.

Table A1.

Core differences between standard and Chronon quantum mechanics.

Table A1.

Core differences between standard and Chronon quantum mechanics.

| Standard QM |

Chronon QM |

| Time is external |

Time is field |

| Hilbert space on t slices |

States on foliation |

| Spin imposed algebraically |

Spin from topology |

| Statistics by postulate |

Statistics from solitons |

| Fixed spacetime |

Dynamic temporal geometry |

| Collapse postulated |

Collapse from decoherence of

|

Appendix F. Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CQM |

Chronon Quantum Mechanics |

| CFT |

Chronon Field Theory |

References

- Amelino-Camelia, G. Quantum-Spacetime Phenomenology. Living Rev. Relativ. 2013, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arnowitt, R.; Deser, S.; Misner, C.W. The dynamics of general relativity. Gen. Rel. Grav. 2008, 40, 1997–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A.; Lewandowski, J. Projective techniques and functional integration for gauge theories. J. Math. Phys. 1995, 36, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A.; Bojowald, M.; Lewandowski, J. Mathematical structure of loop quantum cosmology. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2006, 7, 233–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A.; Tate, R.S.; Uggla, C. Minisuperspaces: Observables and quantization. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 1993, 2, 15–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, J.C.; Muniain, J.P. Gauge Fields, Knots and Gravity; World Scientific: Singapore, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Baez, J.C. The prehistory of n-categorical physics. In Deep Beauty; Halvorson, H., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 13–128. [Google Scholar]

- Baez, J.C.; Huerta, J. An Invitation to Higher Gauge Theory. Gen. Rel. Grav. 2011, 43, 2335–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, J.C.; Huerta, J. The algebra of grand unified theories. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 2010, 47, 483–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, A.P.; Marmo, G.; Skagerstam, B.S.; Stern, A. Classical Topology and Quantum States; World Scientific: Singapore, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, J. The timelessness of quantum gravity: I. The evidence from the classical theory. Class. Quantum Grav. 1994, 11, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, A.; Lochan, K.; Satin, S.; Singh, T.P.; Ulbricht, H. Models of wave-function collapse, underlying theories, and experimental tests. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2013, 85, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassard, G.; Broadbent, A.; Tapp, A. Recasting Mermin’s Multi-player Game into the Framework of Pseudo-Telepathy. Quant. Inf. Comp. 2005, 5, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S. Fate of the False Vacuum: Semiclassical Theory. Phys. Rev. D 1977, 15, 2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, B.S. The Global Approach to Quantum Field Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dirac, P.A.M. Lectures on Quantum Mechanics; Belfer Graduate School of Science, Yeshiva University: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, H. Relative State Formulation of Quantum Mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1957, 29, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, D. Past-Future Asymmetry of the Gravitational Field of a Point Particle. Phys. Rev. 1963, 132, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, P.H. Gauge Field Theories, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Henneaux, M.; Teitelboim, C. Quantization of Gauge Systems; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Behnke, T. et al. The International Linear Collider Technical Design Report, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Isham, C.J. Canonical Quantum Gravity and the Problem of Time. In Integrable Systems, Quantum Groups, and Quantum Field Theories; Ibort, A., Rodríguez, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 157–287. [Google Scholar]

- Joos, E.; Zeh, H.D. The emergence of classical properties through interaction with the environment. Z. Phys. B 1985, 59, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D.E. Five lectures on effective field theory. In Theoretical Advanced Study Institute in Elementary Particle Physics: Physics of the Large and the Small; World Scientific: Singapore, 2011; pp. 223–269. [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer, C. Quantum Gravity, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, S.; Nomizu, K. Foundations of Differential Geometry, Vol. 1; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Kostelecký, V.A.; Russell, N. Data Tables for Lorentz and CPT Violation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. Chronon Field Theory. Zenodo. Chronon Field Theory: Unification of Gravity and Gauge Interactions via Temporal Flow Dynamics. [CrossRef]

- Manton, N.S.; Sutcliffe, P. Topological Solitons; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara, M. Geometry, Topology and Physics, 2nd ed. L: Taylor & Francis, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- NANOGrav Collaboration. Evidence for a stochastic gravitational-wave background. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2023, 951, L3. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, C.; Sen, S. Topology and Geometry for Physicists; Academic Press: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Niedermann, F.; Scrucca, C.A. Soliton Solutions in Field Theory and Cosmology. Phys. Rep. 2021, 890, 1–99. [Google Scholar]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VII. Isotropy and Statistics of the CMB. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaraman, R. Solitons and Instantons; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Rovelli, C. Time in quantum gravity: An hypothesis. Phys. Rev. D 1991, 43, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Quantum Gravity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosshauer, M. Decoherence and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schwinger, J. Quantum Electrodynamics. I. A Covariant Formulation. Phys. Rev. 1948, 74, 1439–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaposhnikov, M.; Shkerin, A. Gravity, scale invariance and the hierarchy problem. JHEP 2020, 2020, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomonaga, S. On a Relativistically Invariant Formulation of the Quantum Theory of Wave Fields. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1946, 1, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, W.G.; Wald, R.M. Time and the interpretation of canonical quantum gravity. Phys. Rev. D 1989, 40, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, R.M. Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime and Black Hole Thermodynamics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, D. The Emergent Multiverse: Quantum Theory According to the Everett Interpretation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A. The Status of Beyond the Standard Model Searches at Colliders. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2021, 71, 151–178. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, Y.S. Simulations of decoherence with quantum computers. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 79, 012318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Current algebra theorems for the U(1) Goldstone boson. Nucl. Phys. B 1979, 156, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Topological Quantum Field Theory. Commun. Math. Phys. 1988, 117, 353–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Quantum Field Theory and the Jones Polynomial. Commun. Math. Phys. 1989, 121, 351–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, A. Quantum Field Theory in a Nutshell, 2nd ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zeh, H.D. The Physical Basis of the Direction of Time, 5th ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).