1. Introduction

Global demand for plant-based food is steadily increasing due to rapid population growth. However, several factors threaten the sustainability of agricultural systems and food security, including the indiscriminate use of chemical fertilizers, water scarcity, and the impacts of climate change [

1]. Besides, it is not only essential to maintain adequate food production to meet global nutritional demands, but also to ensure that the food produced is of high nutritional quality, rich in essential nutrients and bioactive compounds beneficial for human health [

2,

3]. Vegetables play an essential role in human diets, providing vitamins, minerals, fiber, and phytochemicals [

2]. As a result, agricultural focus is shifting from merely maximizing yield to improving the nutritional and functional quality of crops [

3]. Among all essential nutrients, nitrogen (N) stands out as the most influential factor that not only drives crop productivity but also greatly affects the nutritional value of plant-derived foods [

4,

5].

Although N is crucial for crop production, the excessive use of N fertilizers leads to low N use efficiency, economic losses for farmers, and negative environmental consequences such as nitrate leaching, eutrophication, and the contamination of groundwater [

5,

6]. These effects have also been linked to health issues including thyroid dysfunction, cancer, neural tube defects, and diabetes [

4,

7]. N assimilation in plants involves complex biochemical processes regulated by nitrate reductase (NR) activity and the availability of nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium. Micronutrients such as molybdenum, iron, and iodine act as cofactors in these enzymatic processes, influencing N metabolism and utilization efficiency [

6,

8,

9].

In recent years, iodine has emerged as a potentially beneficial element for plants, despite not being classified as essential [

13,

14,

15]. Iodine application through biofortification has shown promise in improving N assimilation and overall plant physiology [

12,

13,

14]. Among its chemical forms, iodate (IO₃⁻) has been proposed as an alternative cofactor for NR enhancing the conversion of nitrate into organic molecules such as amino acids and proteins [

12]. Several studies have demonstrated that potassium iodate (KIO₃) and potassium iodide (KI) can improve N use efficiency and increase chlorophyll content in various crops. For instance, the combination of KIO₃ with urea in maize resulted in enhanced chlorophyll b levels and increased root and foliar N accumulation [

13]. Similarly, in lettuce, both (KI) and KIO₃ improved N use efficiency compared to untreated controls [

14].

Nanotechnology is another important tool to improve plant nutrition as it offers a novel approach to increase the delivery and uptake of nutrients through the use of nanoparticles (NPs) [

10]. Due to their small size (typically <100 nm), NPs can penetrate biological membranes more effectively than conventional fertilizers, leading to improved nutrient absorption and physiological responses [

11]. The use of various types of nanoparticles has shown positive effects on N assimilation, biomass accumulation, and crop yield. For example, TiO₂ nanoparticles at low concentrations (2–6 mg·L⁻¹) enhanced amino acid and pigment levels in coriander, resulting in improved productivity [

16]. Similarly, foliar application of ZnO nanoparticles at only 133 mg·L⁻¹ outperformed chelated zinc in peanut crops [

17].

To assess the effectiveness of any treatment aimed at improving plant nutrition, it is essential to analyze physiological and biochemical parameters that reflect the success of N assimilation and overall plant health. Among these, the concentration of free amino acids and soluble proteins serves as a direct indicator of N metabolism, since they are primary products of nitrate reduction and ammonium assimilation and are also involved in stress responses and developmental processes [

18,

19]. Additionally, chlorophyll content is a widely used indicator due to its high N content and its direct link to the photosynthetic capacity of the plant. As such, it not only reflects N status but also provides insights into the plant’s ability to produce biomass and maintain physiological activity under different nutritional conditions [

20,

21].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of foliar application of iodine nanoparticles (INPs) in comparison to potassium iodide (KI) on biomass accumulation, yield, total chlorophyll, soluble proteins, free amino acids, and nitrogen assimilation in Lactuca sativa L. cv. Butterhead. We hypothesize that iodine nanoparticles, due to their nanoscale properties and enhanced delivery potential, will result in greater improvements in N metabolism, biochemical quality, and physiological performance than conventional iodine treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Sites and Crop Management

The experiment was conducted at the Food and Development Research Center (CIAD), Delicias Unit, Chihuahua, Mexico, during March to May 2024, under controlled conditions in a shade net house. Seeds of Lactuca sativa L. cv. Butterhead, purchased from Islas’s Garden Seed Company® (Eagle Rd, USA), were used. Germination was carried out in polystyrene trays with vermiculite as substrate, applying 250 mL of Hoagland nutrient solution every three days for 30 days. Thirty days after sowing (DAS), the seedlings were transplanted into 5 L plastic pots, using a 2:1 (v/v) mixture of vermiculite and perlite as substrate.

The irrigation system used was passive hydroponic, using sub-irrigation in plastic trays (33 × 55 × 4 cm), where the pots were placed directly on a constant layer of nutrient solution. This technique allows water and nutrients to rise by capillary action from the base of each pot, promoting a uniform and efficient supply without wetting the foliage [

22]. During the trial, a modified Hoagland nutrient solution was supplied according to the physiological requirements of the crop, in accordance with Sánchez et al. [

23]. One liter of solution was applied per pot every 24 hours, with a pH of 6 ± 0.1, from transplanting to physiological maturity (41 DAS), maintaining this frequency until harvest (71 DAS).

2.2. Characterization of Iodine Nanopartices (INPs)

The concentrations of iodine nanoparticles (INPs) used in this study were selected based on commercial compounds, such as potassium iodate, reported in previous studies by Dávila-Rangel et al. (2020) [

24], due to the limited literature available on the specific physiological properties of iodine nanoparticles in agricultural systems.

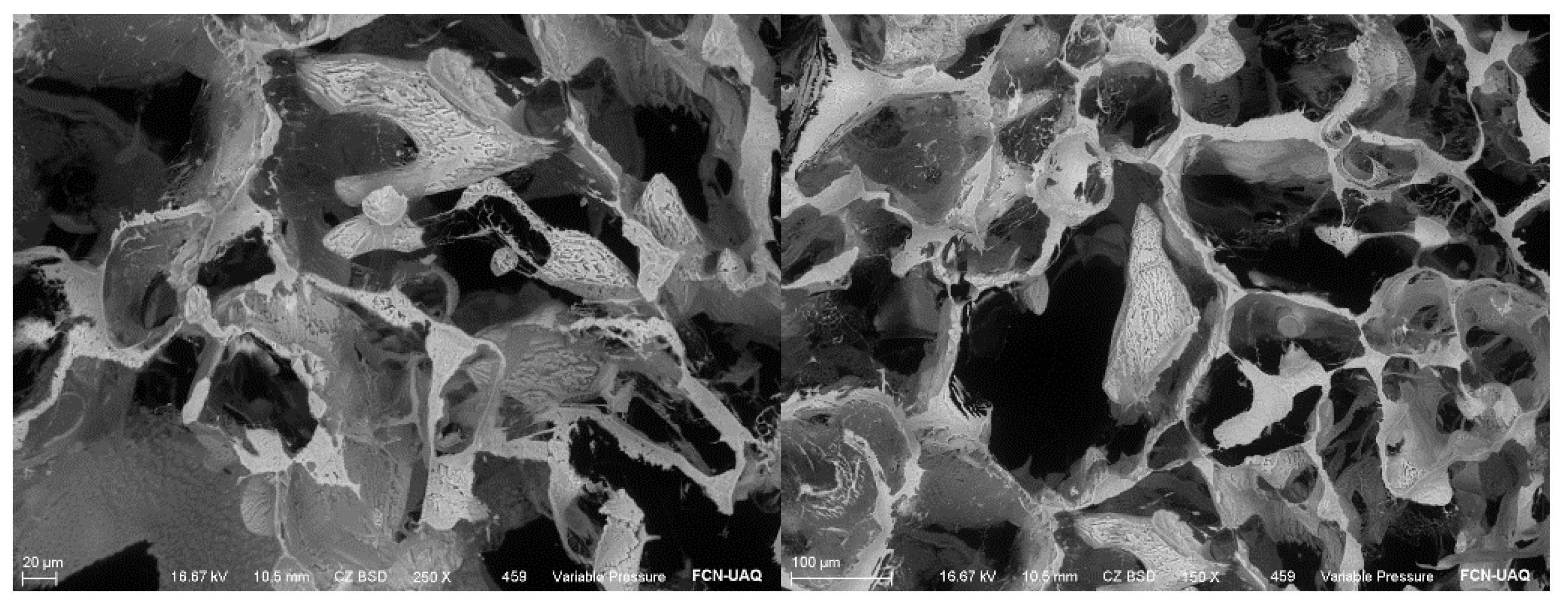

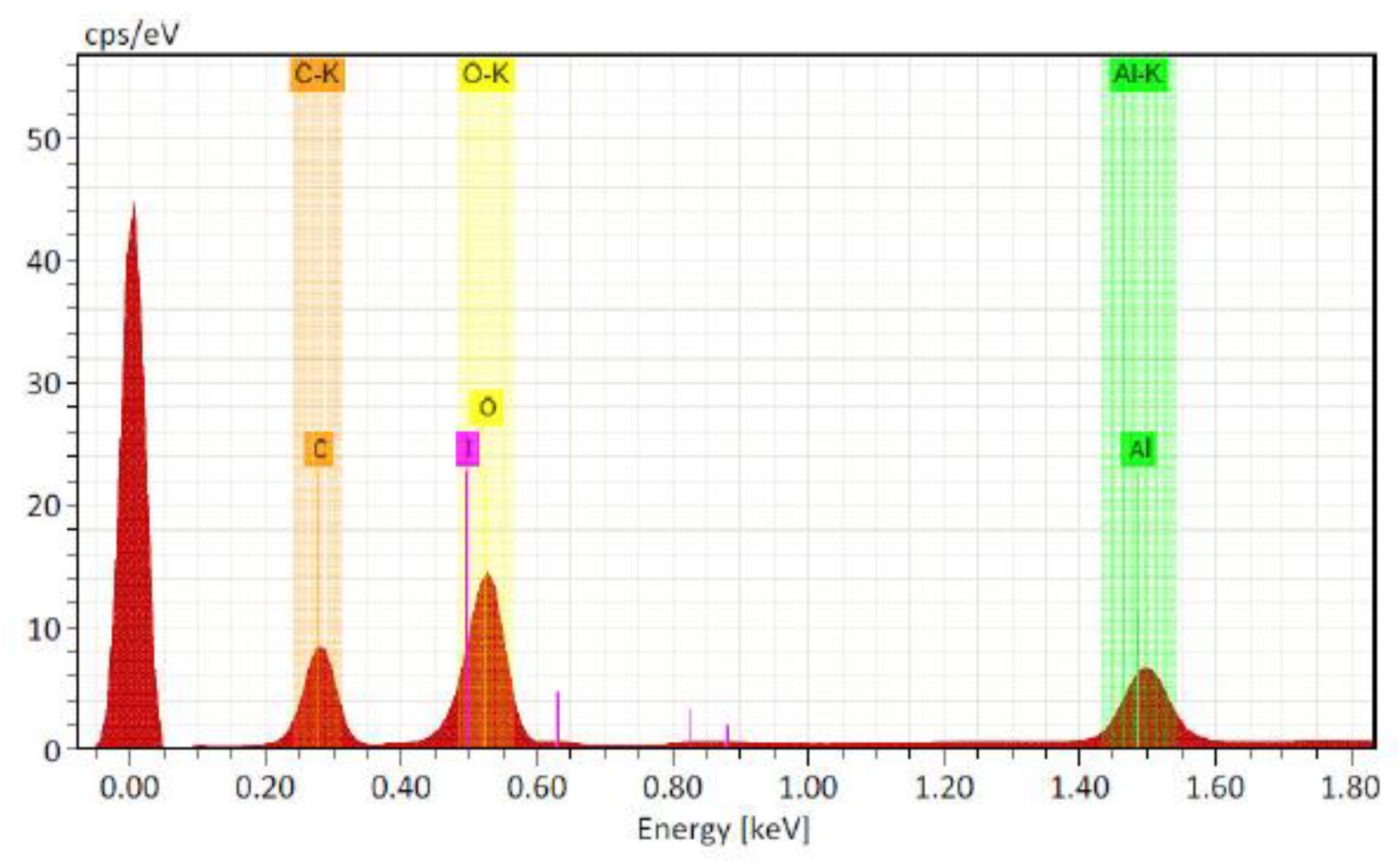

The INPs used in this study were synthesized using the wet chemical method. They appeared as a fine dark brown powder with evidence of agglomeration and were characterized structurally and morphologically by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (

Figure 1), accompanied by elemental microanalysis by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), confirming the presence of iodine (

Figure 2). The nanoparticles were provided by the company Investigación y Desarrollo de Nanomateriales S.A. de C.V., located in San Luis Potosí, Mexico.

2.3. Nanoparticles Preparation

A stock solution of (INPs) was prepared at a concentration of 320 µM, using triple-distilled water as the solvent. The mixture was homogenized by mechanical stirring on a magnetic plate (VWR®) at 700 rpm for 20 minutes, and then subjected to sonication in an ultrasonic bath (Vevor Ultrasonic Cleaner, Cleveland, OH, USA) at a frequency of 40 kHz for 15 minutes, at a controlled temperature of 25–30 °C, following the protocol described by Waqas et al. [

25]. From this stock solution, the necessary dilutions were made to achieve the concentrations required for the experimental treatments.

2.4. Experimental Design and Treatments

A completely randomized design with a single-factor arrangement consisting of six treatments was used, resulting from the combination of two sources of iodine (potassium iodide, (KI), and iodine nanoparticles INPs) applied in three concentrations: 40, 80, and 160 μM. The treatments established were: Control (0 μM), KI 40 μM, KI 80 μM, KI 160 μM, INPs 40 μM, INPs 80 μM, and INPs 160 μM. Each treatment had four replicates, and the experimental unit consisted of a single plant grown individually in a pot. The applications were made foliar during the vegetative phase of the crop, under controlled conditions.

2.5. Plant Sampling

Once the plants reached physiological maturity at 71 DAS, the plant material was harvested. The collected material was washed with distilled water to remove residues and finally separated into organs (root, leaves). The samples were divided into fresh and dry material. The fresh material was used to determine yield, nitrate reductase enzyme activity, and the concentration of photosynthetic pigments, amino acids, and soluble proteins. The dry material was used to quantify biomass.

2.6. Plant Analysis

2.6.1. Total Biomass and Yield

To quantify total biomass and yield, one plant was randomly selected from each pot and weighed fresh using a compact balance (A&D Co., Ltd., EK-120, Tokyo, Japan). The plant was then dissected into leaves and roots, and each organ was weighed fresh. Yield was expressed as the fresh weight of leaves per plant (g plant-1 FW).

The organs obtained were rinsed three times in distilled water and dried on filter paper at room temperature for 24 h. After this period, 50% of the plant material was dried in a 13.9 cubic foot forced-air laboratory oven (Shel-Lab 1380FX, Cornelius, OR, USA) at 45˚C for 72 h. Once the samples had lost moisture, they were weighed using an electronic analytical balance (A&D Co., Ltd., HR-120, Tokyo, Japan). Total biomass was expressed as the sum of the dry weight of the two plant organs (g plant-1 DW).

2.6.2. Extraction and Assay of NR (E.C. 1.6.6.1)

For each sampling, root and leaf portions were ground, with a ratio of 1:5 (w/v), in a mortar at 0 ◦C in 50 mM KH

2PO

4 buffer pH 7.5, containing 2 mM EDTA, 1.5% (w/v) soluble casein, 2mM DTT and 1% (w/v) insoluble PVPP. The homogenate was filtered through two layers of Miracloth (Cabiochem) and centrifugated at 3000×g for 5 min, after which the supernatant was centrifuged at 30 000 ×

g for 20 min. The resulting supernatant was used to measure enzyme activities and soluble protein. The extraction medium was optimized for the enzymatic activities so that these could be extracted jointly by the same method [

26,

27]. The NR assay followed the methodology of [

28]. The nitrite forwed was colorimetrically determined at

A540 after azocoupling with sulphanilamide and naphthylenediamine dihydrochloride according to the method of [

29]. The NR activity was expressed as μmol NO

2 – formed mg

-1 protein min

-1.

2.6.3. Photosynthetic Pigments

The concentrations of chlorophyll a and b and total were determined using the method described by Wellburn [

30]. Ten leaf discs with a diameter of 7 mm were weighed and infiltrated in 10 mL of methanol (CH

3OH). The samples were sealed and left to stand in the dark for 24 h. After this time, the absorbance of the samples was measured at wavelengths of 653 and 666 nm for chlorophyll b and chlorophyll a, respectively, using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, GENESYS™ 10S, Madison, WI, USA). Pigment concentrations were expressed in μg cm

2 FW and calculated using the following formulas:

where Vf: final volume; W1: weight per leaf disc; W2: total weight of leaf discs; r: radius of leaf discs; n: number of leaf discs.

2.6.4. Concentrations of soluble Amino Acids and Soluble Proteins

A volume of 0.5 g of leaf blade plant sample was homogenized with 5 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH=7 at 4 °C (solution of 6.8 g of K

2HPO

4 dissolved in 1 L of distilled water, adjusted to pH=7 with a solution of 8.81 g KH

2PO

4 dissolved in 1 L of distilled water). The sample was filtered through 4 layers of gauze and centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 15 min in a centrifuge cooled to 4 °C (Allegra™, 64R Centrifuge, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The supernatant was used to determine the concentrations of amino acids and soluble proteins using the methods described by Yemm et al. [

31] and Bradford [

32], respectively.

To quantify soluble amino acids, an aliquot of 100 μL of supernatant was mixed with 1.5 mL of ninhydrin reagent (2 g of ninhydrin dissolved in 50 mL of ethylene glycol (CH2OHCH2OH), mixed with 80 mg of stannous chloride (SnCl2.2H2O), dissolved in 50 mL of 200 mM citrate buffer at pH=5 (solution of 59.41 g of tribasic sodium citrate dihydrate (C6H5Na3O72H2O), dissolved in 1 L of distilled water, and buffered to pH 5 with a solution of 38.81 g of anhydrous citric acid (C6H8O7)). The sample was stirred and placed in a water bath at 100 °C for 20 min. The samples were then placed in a water bath at 4 °C for 30 min and reacted with 8 mL of 50% (v/v) 1-propanol (C3H8O). Finally, the samples were measured at 570 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, GENESYS™ 10S, Madison, WI, USA) against a glycine standard curve. The results were expressed as (mg g-1 FW).

For the quantification of soluble proteins, a 20 μL aliquot of the centrifuged supernatant was taken and mixed with 1 mL of the Bradford Quick Start™ Protein Assay Kit (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA, USA) coloring reagent. The samples were shaken and allowed to stand for 15 min. Finally, they were measured at an absorbance of 595 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, GENESYS™ 10S, Madison, WI, USA) and compared to a standard curve of bovine serum albumin (BSA).

The curve was prepared by taking 20 μL of each of the standards from the Bradford Quick Start™ protein assay kit at concentrations of 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, and 2 mg mL-1 of BSA and distilled water for the blank. The results were expressed as (mg g-1 FW).

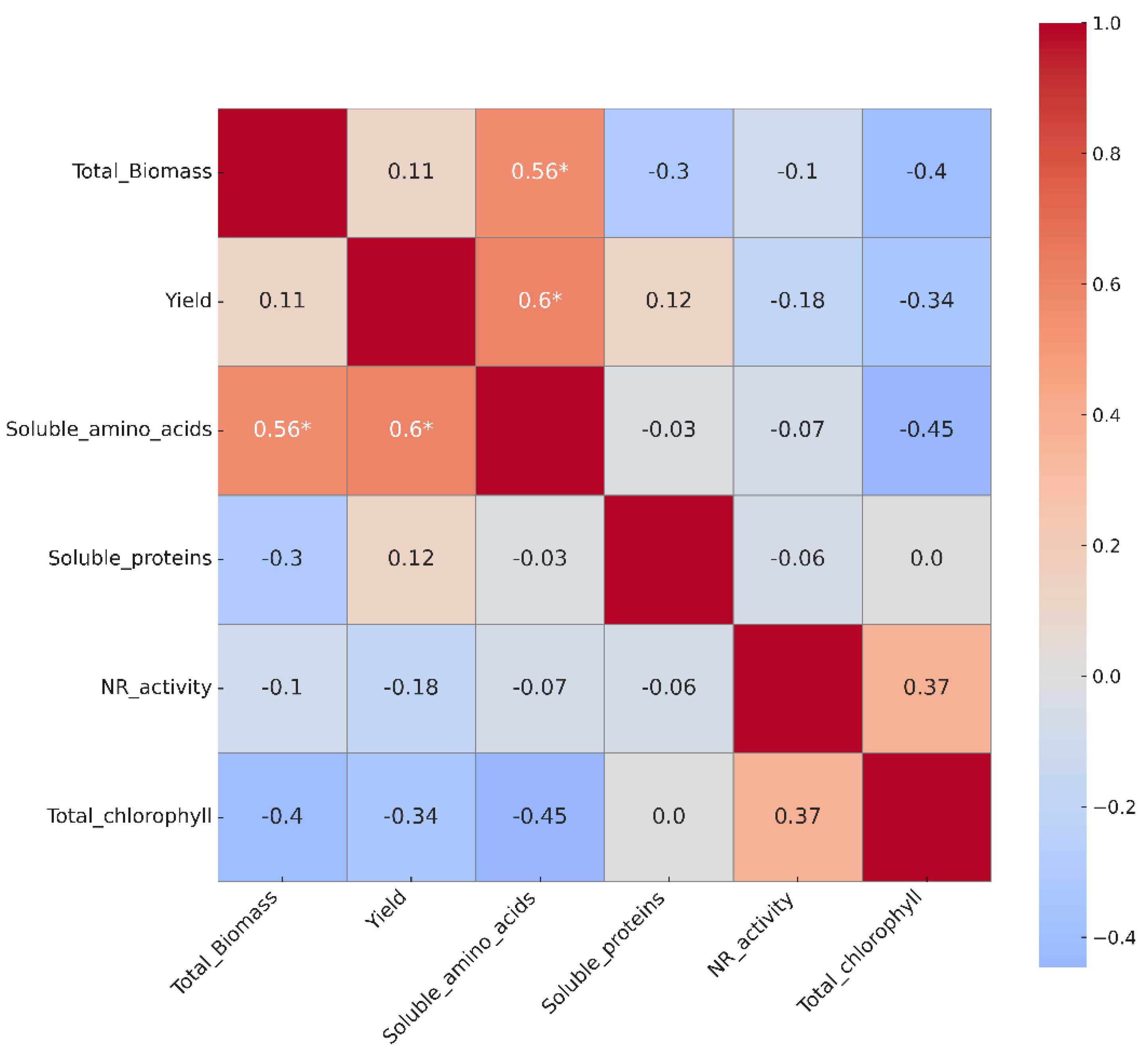

2.6.5. Pearson Correlation Heatmap

To evaluate the relationships between physiological and biochemical variables, a Pearson correlation matrix was developed using the averages per treatment. The results were represented graphically using a heatmap generated in Python (v 3.11), where the intensity and direction of the correlations were expressed using a color scale. Correlation values close to +1 indicate a strong positive association, while values close to -1 reflect a strong negative correlation. Correlations close to 0 are interpreted as weak or non-existent, allowing functional or independent relationships between the evaluated variables to be identified [

33].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was based on a linear fixed-effects model corresponding to a completely randomized design with a single factor, expressed by equation (4):

where Yij was the response variable, under the effect of the ith treatment and the jth repetition; μ was the overall mean; τi was the effect of the ith treatment; and εij was the experimental error.

Prior to analysis of variance (ANOVA), the data were evaluated to verify compliance with the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances. Normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test, while homogeneity of variances was evaluated using Bartlett’s test. Once compliance with these assumptions was confirmed, a one-way ANOVA was performed.

When statistically significant differences were detected between treatments (p ≤ 0.05), a mean comparison test was applied using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) method, with a significance level of p ≤ 0.05. The analyses were performed using SAS® statistical software version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) [

34]. Treatments with different letters indicated statistically significant differences according to the LSD test.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Total Biomass

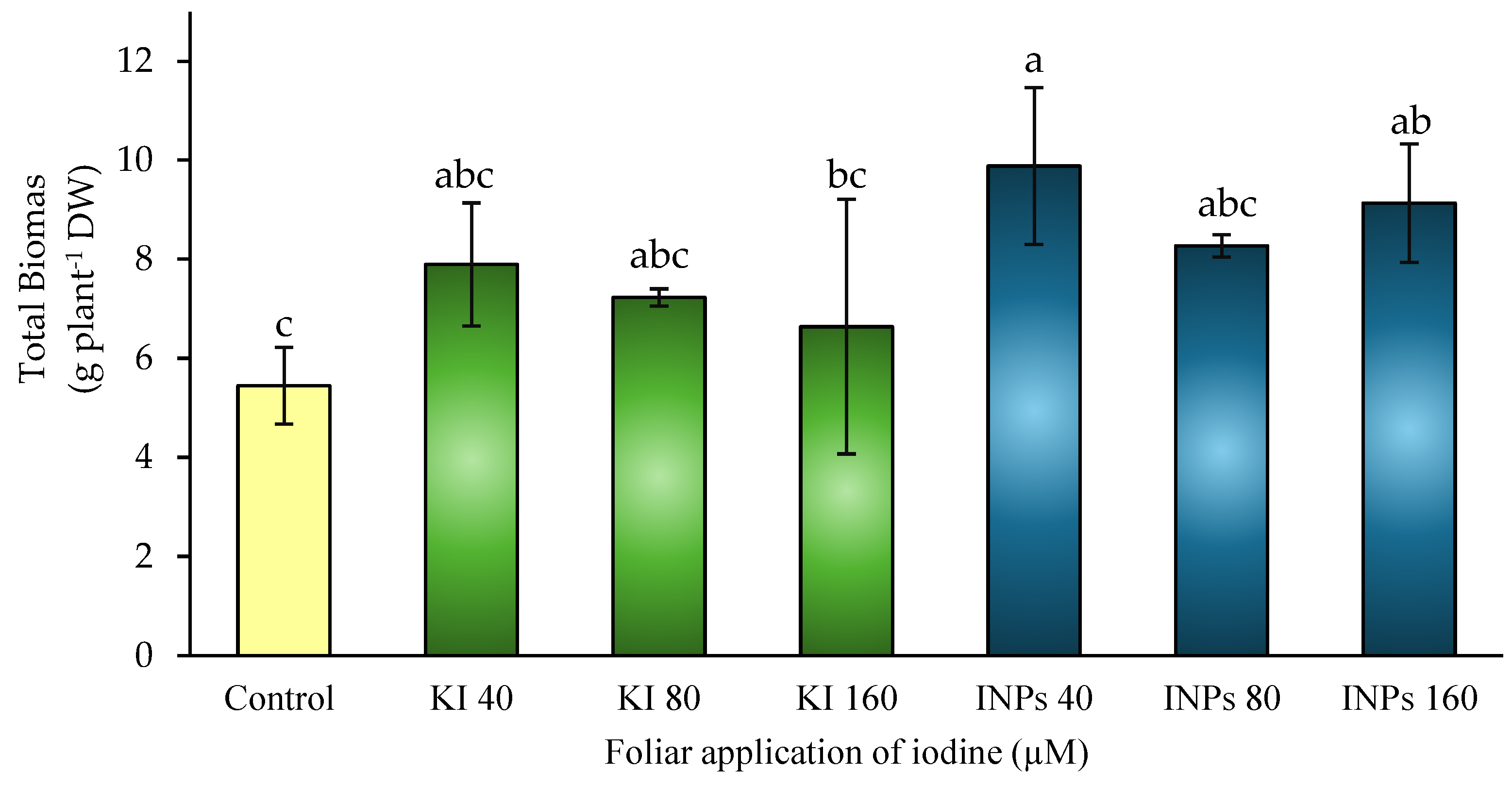

Biomass accumulation is one of the essential parameters for determining nutrient efficiency in crops [

35]. In this study, statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) were observed between treatments in total dry biomass accumulation (

Figure 3). Treatment with iodine nanoparticles (INPs) at 40 μM showed the greatest effect, with a 68.75% increase in biomass compared to the control. In contrast, treatments with potassium iodide (KI) showed more moderate increases, the highest being KI 40 μM, with a 37.5% increase over the control.

The notable increase in biomass observed with INPs can be attributed to improved efficiency in the absorption and utilization of nitrogen, an essential element for the formation of plant structures. At the physiological level, nanoparticles, due to their small size and high active surface area, promote greater penetration into tissues and sustained release of iodine, improving the availability of the element at key sites of metabolism, such as the chloroplast and cytosol [

36]. It has also been proposed that iodine, especially in the form of iodate, may act as an alternative cofactor for the enzyme nitrate reductase (NR), facilitating nitrate reduction and promoting the synthesis of amino acids and proteins, which are essential components for plant structural development [

37].

Similar results were reported by Medrano-Macías et al. (2016) [

38], who observed a significant increase in the biomass of lettuce biofortified with potassium iodate, particularly when combined with nitrogen. Similarly, Sularz et al. (2020) [

39] found that foliar applications of iodine in lettuce increased both biomass and iodine content in plant tissue, emphasizing its dual role as a biofortifying nutrient and regulator of nitrogen metabolism.

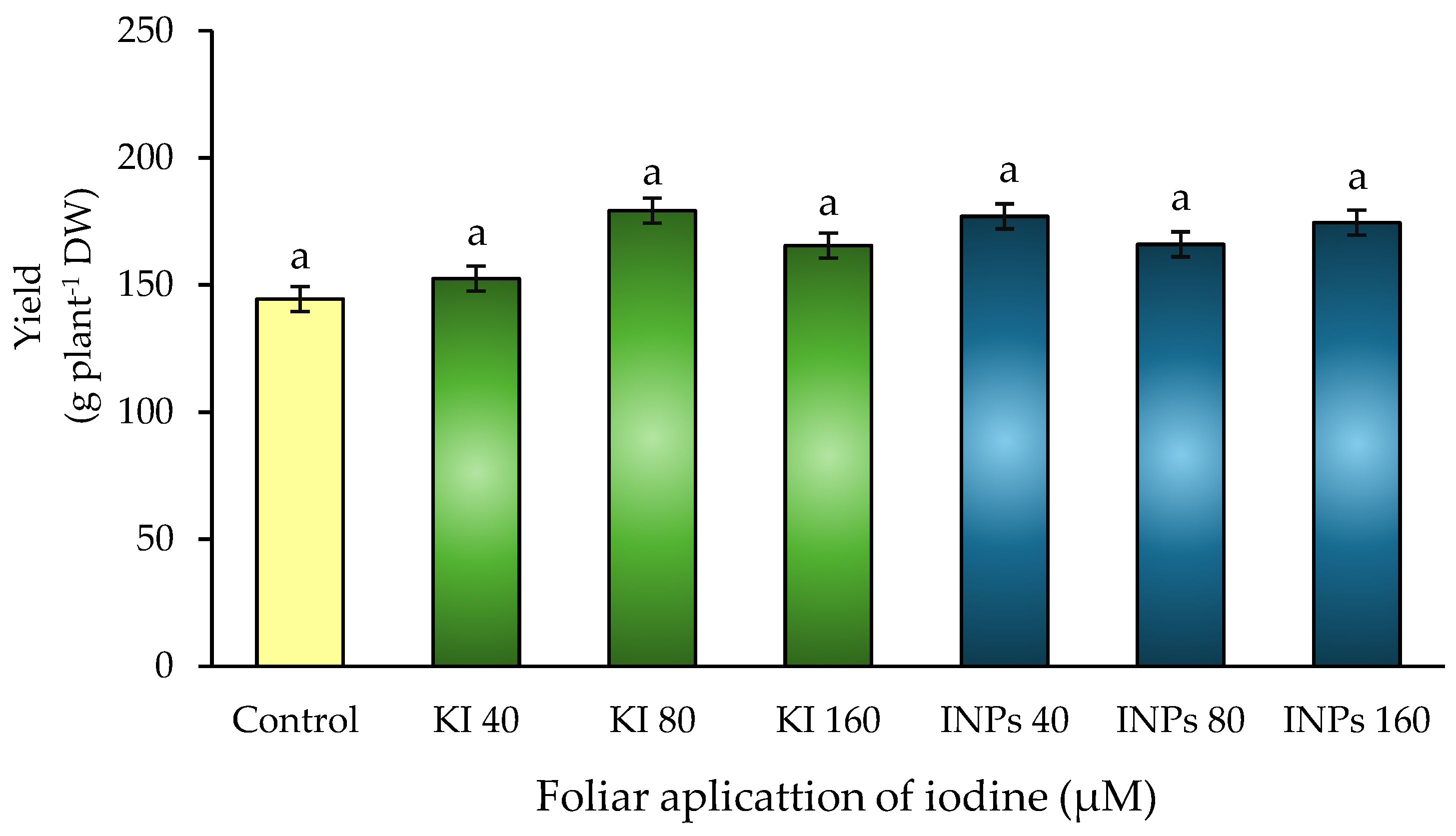

3.2. Yield

Agricultural yield is a key integrating parameter that reflects the physiological efficiency of plants in converting resources into harvestable biomass. Its value lies in the fact that it represents the end result of processes such as photosynthesis, assimilate translocation, and reproductive development, allowing the overall performance of the crop under different management conditions to be evaluated [

40].

In this study, no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed between treatments in terms of total yield, as indicated by the homogeneous letters in the graph (

Figure 4). However, positive trends were recorded in all iodine treatments compared to the control. The treatments with iodine nanoparticles (INPs), especially at 40 μM, showed a slight increase (16%) compared to the control, although this was not statistically significant.

From a physiological perspective, these results suggest that the application of iodine, both in the form of iodide and nanoparticles, does not negatively affect reproductive processes or the filling of harvest structures, even at relatively high concentrations. This could be related to iodine’s ability to modulate redox balance and preserve tissue functionality during critical phases of reproductive development without inducing adverse physiological stress [

41].

Furthermore, recent studies indicate that the action of iodine may be related to an improvement in physiological uniformity among plants, contributing to stabilize production without necessarily generating abrupt increases in yield [

42]. This is in line with the observed data, where the treatments showed similar behaviors without exhibiting a marked differential response.

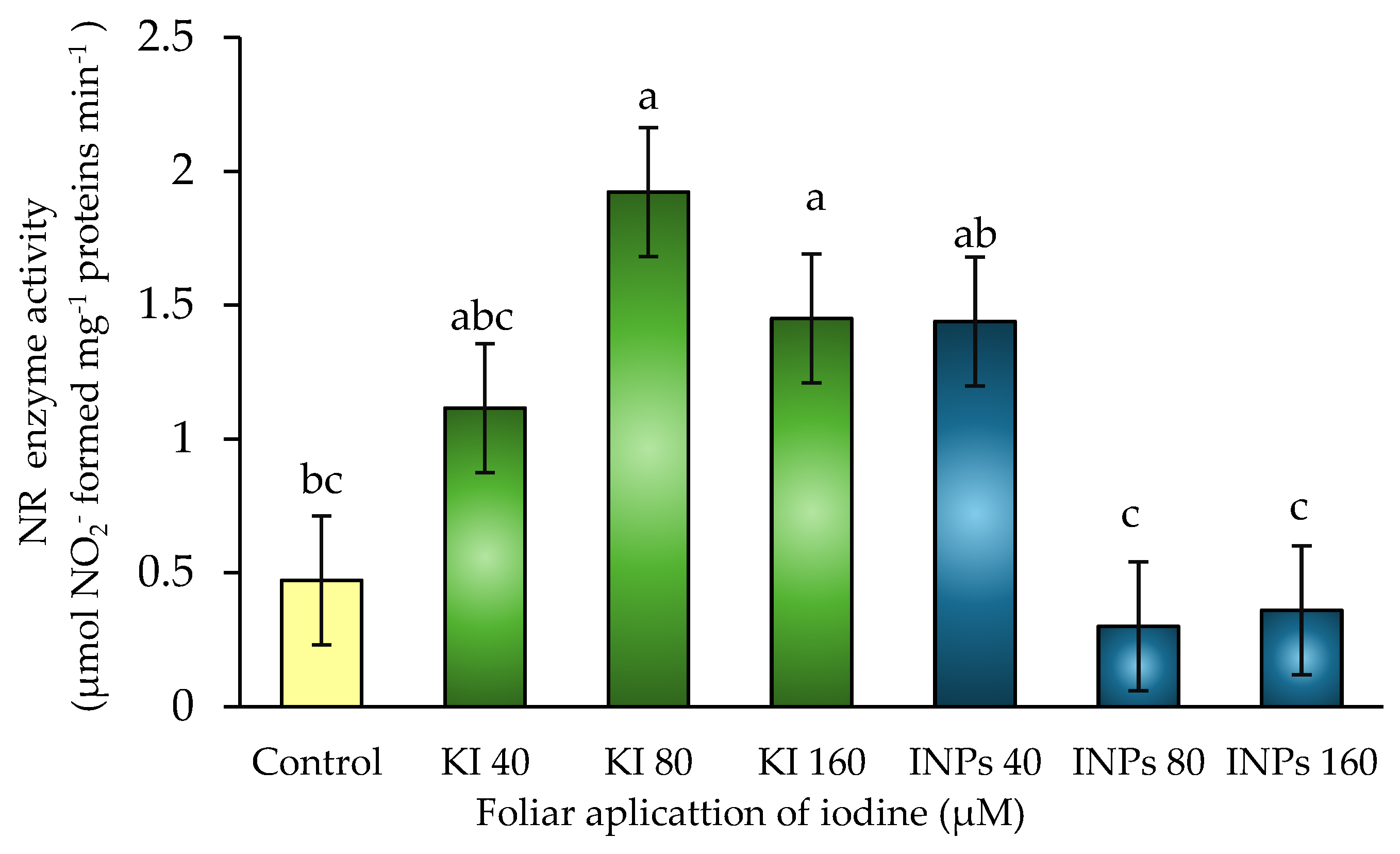

3.3. “In vivo” Nitrate Reductase Enzyme Activity (NR) (E.C. 1.7.11)

Nitrate reductase (NR) is a key enzyme in nitrogen metabolism, as it catalyzes the reduction of nitrate (NO₃⁻) to nitrite (NO₂⁻), an essential step for the subsequent synthesis of amino acids and proteins. Its activity is strongly regulated by nitrate availability, hormonal signals, light, and cellular redox status, and is considered a functional marker of nitrogen use efficiency in plants [

43].

In this study, statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) in NR activity were observed between treatments (

Figure 5). The treatment with 80 μM KI showed the highest value, with an increase of more than 307% compared to the control, followed by 160 KI and 40 μM KI, which also showed high levels. In contrast, treatments with iodine nanoparticles (INPs) at 160 and 80 μM showed the lowest enzyme activities, even below the control level.

These results suggest that the ionic form of iodine (potassium iodide) may act as a positive signal or stabilizing cofactor for NR, promoting its synthesis or preventing its post-translational degradation. Some authors have proposed that iodide may influence the expression of genes associated with nitrogen metabolism through redox signals or indirect effects on hormonal pathways such as salicylic acid and jasmonic acid [

44].

In contrast, iodine nanoparticles can generate localized oxidative stress or interfere with redox balance, which would negatively affect NR stability or activity. This is consistent with studies indicating that, at suboptimal concentrations or through sustained release mechanisms, INPs can activate defense responses that inhibit redox-sensitive enzymes such as NR [

45].

In addition, the nanoparticle form could alter the spatial distribution of iodine, limiting its availability in the cytosol (where NR is located) and redirecting it to organelles or compartments where it does not exert its catalytic effect, thus decreasing its functionality [

46].

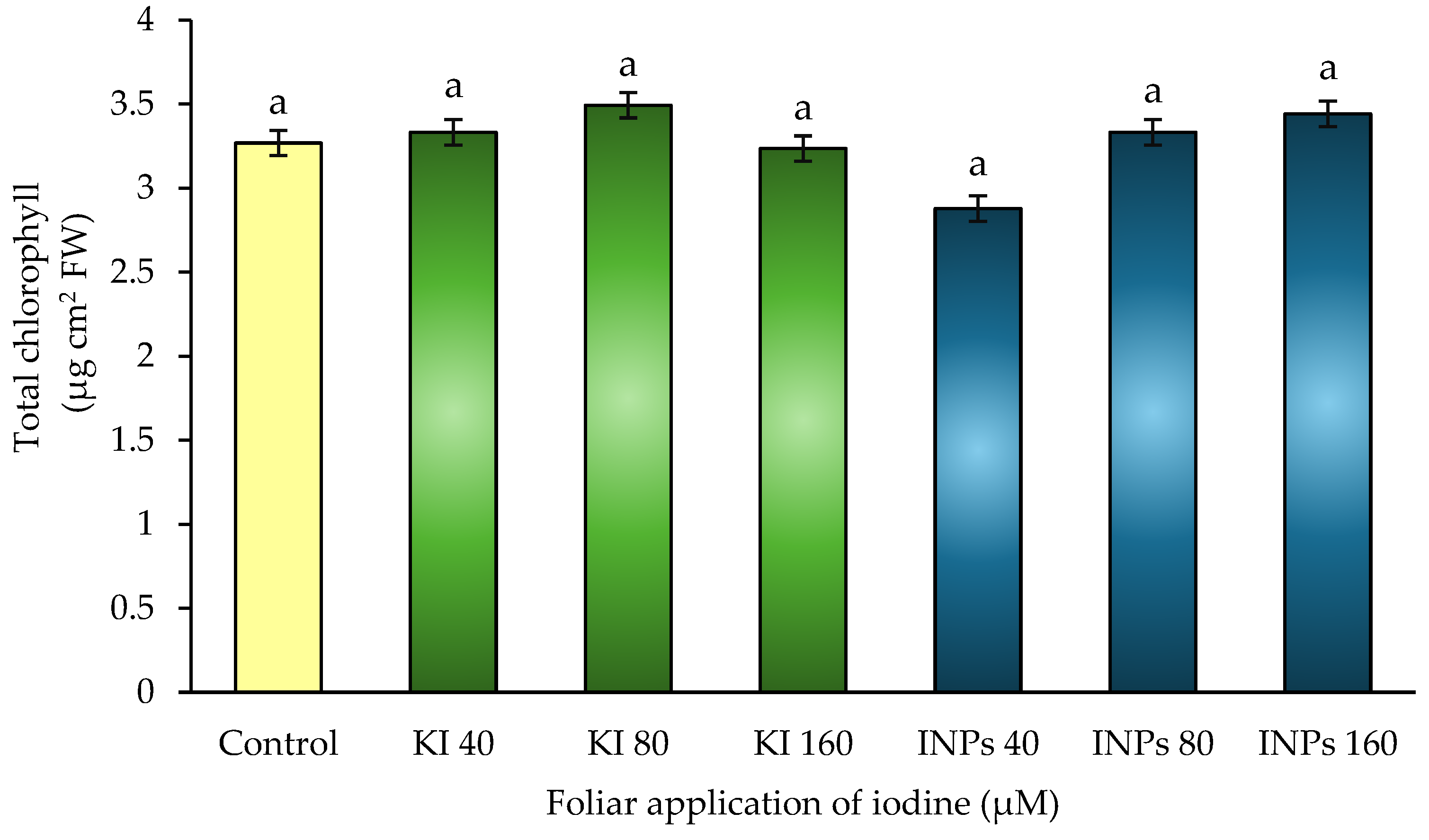

3.4. Total chlorophyll

Total chlorophyll is one of the main functional indicators of the photosynthetic apparatus, directly related to the plant’s ability to absorb light and carry out photosynthesis efficiently. Stability in its content reflects not only adequate nutritional status but also the absence of severe oxidative stress or metabolic disruptions that compromise pigment biosynthesis [

47].

In the present study, no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed between treatments, as indicated by the homogeneous letters (

Figure 6). Despite this, interesting physiological trends were recorded: treatments with INPs (especially at 40 and 80 μM) showed a slight decrease (5–8%) in chlorophyll content compared to the control, while treatments with potassium iodide (KI) maintained similar or even slightly higher levels.

These results suggest that the ionic form of iodine does not negatively affect the synthesis of photosynthetic pigments, while nanoparticles could induce mild stress or a redistribution of essential nutrients, such as magnesium or iron, which are directly involved in the structure of chlorophyll. Recent research has shown that the use of nanoparticles can modify the transport and accumulation of minerals in photosynthetic tissues, without generating evident phytotoxicity, but with possible compensatory effects on hormonal regulation or stomatal density [

48].

On the other hand, it is possible that the moderate reduction in chlorophyll in INPs treatments is linked to an increase in the production of phenolic compounds or non-enzymatic antioxidants, as part of an adaptive response to the nanoparticulate stimulus, a phenomenon documented in studies on plant biostimulation with nanomaterials [

49].

Overall, the results suggest that iodine biofortification, at the concentrations evaluated, does not compromise the photosynthetic functionality of plants. The small variations observed with INPs could be attributed to minor physiological adjustments rather than actual damage or deficiency processes, confirming the viability of these technologies in sustainable plant improvement strategies.

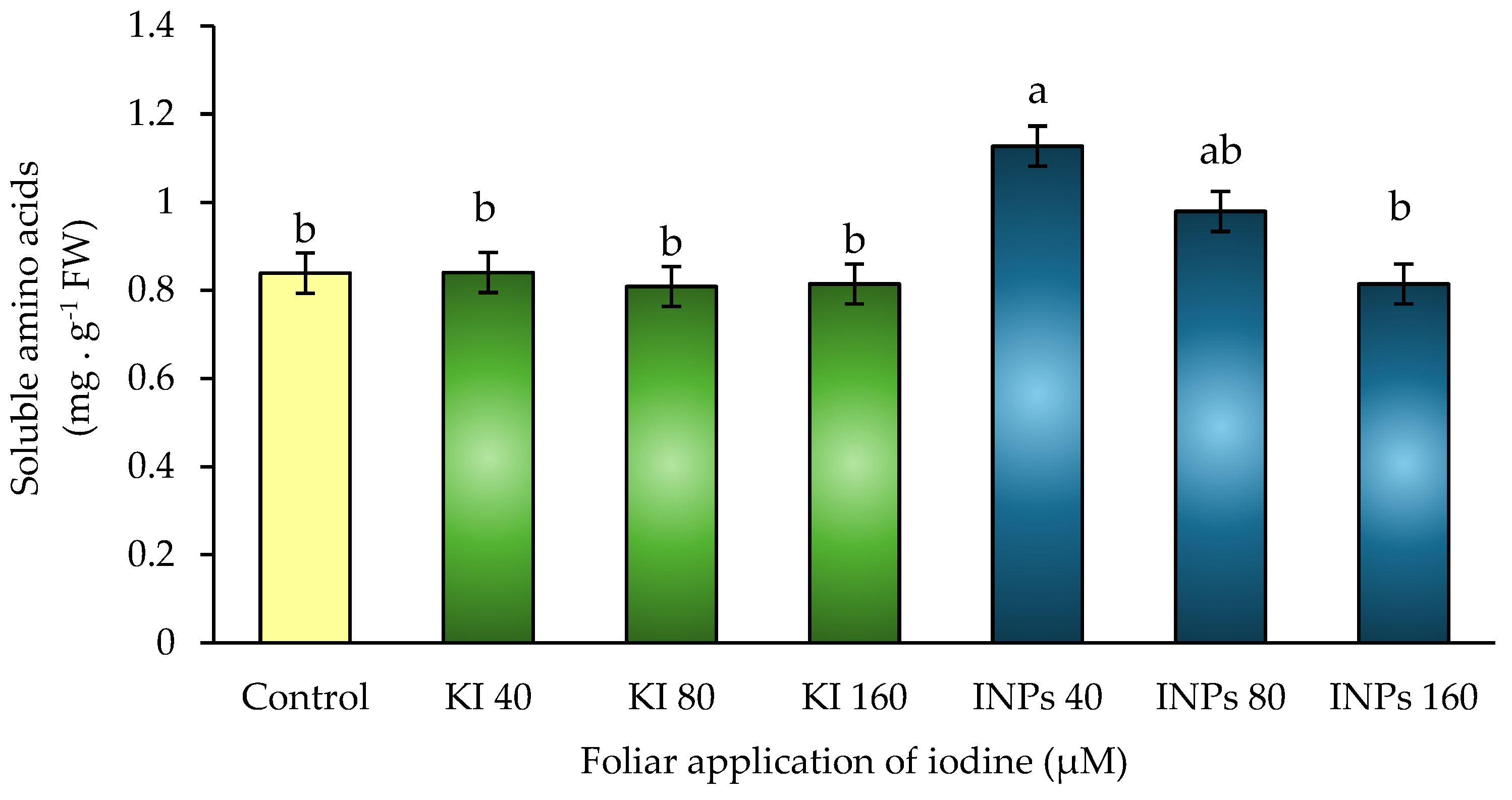

3.5. Concentration of Soluble Amino Acids

Soluble amino acids perform essential functions in plants beyond being precursors of proteins, they participate in osmotic regulation, stress responses, metabolic signaling, and nitrogen storage. Their accumulation is influenced by nutrient availability, enzyme activity (such as glutamine synthetase and glutamate dehydrogenase), and environmental conditions that alter the anabolic/catabolic balance of nitrogen [

50].

In this study, statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) were observed between treatments (

Figure 7). Treatments with iodine nanoparticles (INPs), particularly at 40 μM, recorded the highest value, with an increase of approximately 30% compared to the control, followed by INPs 80 and 160 μM. In contrast, treatments with potassium iodide (KI) showed values similar to the control, with no relevant increases.

These results indicate that the nanoparticulate form of iodine could be positively modulating nitrogen metabolism, favoring the synthesis and accumulation of free amino acids. This phenomenon can be explained by a combination of factors: greater efficiency in nutrient absorption, activation of biosynthetic pathways such as the glutamate pathway, and possible inhibition of amino acid degradation pathways under controlled redox conditions [

51].

On the other hand, the high accumulation of soluble amino acids could reflect a beneficial adaptive response that improves osmotic balance and favors the temporary storage of reduced nitrogen, especially in treatments with INPs. These molecules also act as carbon and nitrogen donors for the synthesis of secondary compounds during development or in the face of moderate environmental challenges [

52].

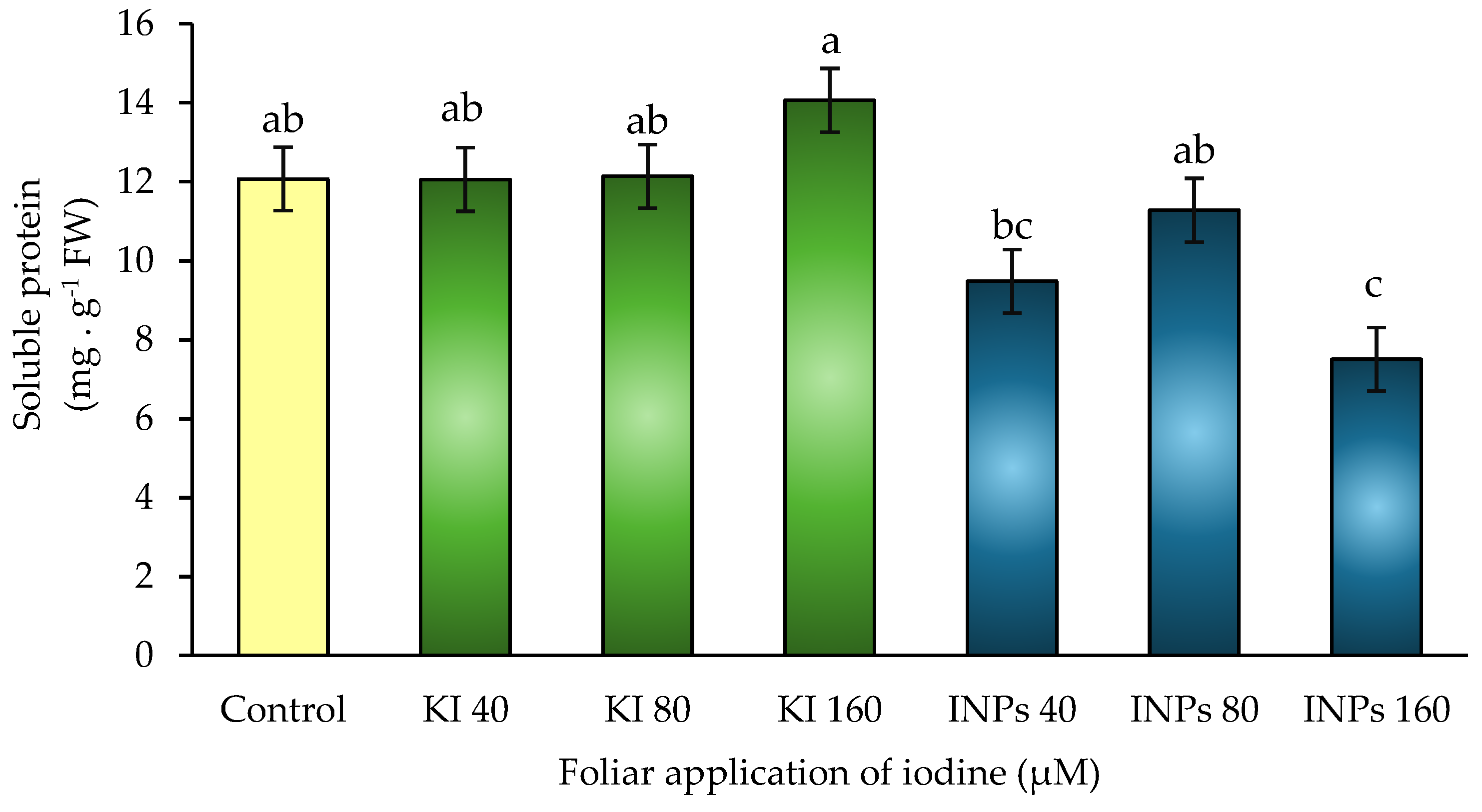

3.6. Concentration of Soluble Proteins

Soluble proteins in plant tissues represent a critical fraction of cell metabolism, including enzymes, structural proteins, and molecules involved in stress response. Their accumulation is highly sensitive to nutritional status and environmental conditions, serving as a functional biomarker of nitrogen metabolism and the plant’s biosynthetic capacity [

53].

In the present study, statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) were observed between treatments (

Figure 8).Treatment with 160 μM KI showed the highest value, with an approximate increase of 20% compared to the control, followed by 80 and 40 μM KI, with no significant differences between them. In contrast, treatments with iodine nanoparticles (INPs) at 40 and 160 μM showed the lowest soluble protein values, even below the control.

From a physiological point of view, these results could be due to the fact that the ionic form of iodine (potassium iodide) promotes greater availability of assimilable nitrogen, favoring protein synthesis. This effect may be mediated by activation of nitrogen transport to meristematic tissues and stimulation of biosynthetic pathways associated with glutamine and aspartic acid, key pathways in the formation of soluble proteins in leaves [

54].

Conversely, iodine nanoparticles could be generating negative redox modulation or metabolic competition, leading to a decrease in the expression or translation of functional proteins. It has been proposed that INPs, depending on their surface charge and concentration, may interfere with the ribosomal machinery or induce protein recycling mechanisms (autophagy), thereby reducing the net concentration of soluble proteins [

43].

In addition, a possible imbalance in the carbon/nitrogen ratio caused by signaling overload or sustained release of iodine from nanoparticles could be redirecting metabolism toward secondary pathways, such as the synthesis of phenolic compounds, to the detriment of protein production [

55].

Taken together, these findings suggest that while iodine in ionic form (KI) may favor plant protein metabolism, its use in nanoparticle form requires fine adjustments in concentration and formulation to avoid adverse effects on the synthesis and accumulation of functional proteins in the plant.

3.7. Heat Map and Correlation

Pearson’s correlation analysis, visualized using a heat map, allowed us to identify linear associations between key variables related to nitrogen metabolism, growth, and photosynthetic activity in Lactuca sativa. This approach is widely used in plant nutrition studies to understand functional interactions under different nutritional management schemes [

48].

Statistically significant positive correlations were observed between total biomass, yield, and soluble amino acid content (r = 0.56* and r = 0.6*, respectively) (

Figure 9). These relationships suggest that biomass accumulation and plant productivity are closely linked to increased availability of soluble nitrogen compounds, reinforcing the hypothesis that iodine nanoparticles (INPs) treatments favor a more efficient nitrogen assimilation pathway [

48]. This pattern is consistent with the behavior observed in the 40 μM INPs treatments, where the highest levels of biomass and amino acids were recorded.

In contrast, no significant correlations were observed between biomass or yield with nitrate reductase activity or soluble protein content, indicating that under the experimental conditions these variables were not direct determinants of productivity. This finding suggests that, although NR and proteins participate in the general nitrogen pathway, their variation does not necessarily translate into visible improvements in growth or yield in the short term.

Negative correlations were also identified between total biomass and total chlorophyll concentration (r = –0.4), as well as between soluble amino acids and chlorophyll (r = –0.45). This could be interpreted as a relative dilution of pigment content in plants with higher leaf mass, without implying a functional deterioration of the photosynthetic apparatus [

56]. The stability of photosynthesis observed in treatments with INPs, even with high levels of growth, supports this interpretation. Taken together, these correlations support the positive effect of iodine nanoparticles on nitrogen metabolism, especially in the synthesis of soluble amino acids, and demonstrate a direct relationship between these molecules and plant productivity. Furthermore, it is confirmed that these treatments do not compromise photosynthetic integrity, reinforcing their potential as sustainable tools in efficient nitrogen management.

4. Conclusions

Foliar application of iodine nanoparticles (INPs) on Lactuca sativa L. promoted greater nitrogen assimilation, evidenced by an increase in total biomass and soluble amino acid accumulation, without compromising the photosynthetic stability of the crop. The 40 μM dose of INPs proved to be the most effective, showing the best overall physiological response without inducing phytotoxic effects. This formulation consistently outperformed potassium iodide (KI), suggesting that the nanostructuring of iodine improves its absorption and utilization in plant tissue. Together, these results confirm that foliar biofortification with iodine nanoparticles at appropriate doses represents a safe, efficient, and promising tool for optimizing nitrogen nutrition and improving the functional quality of horticultural crops in sustainable agricultural systems.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: J.J.P.-C. and E.S.; data collection: E.H.O.-C. and J.J.P.-C.; analysis and interpretation of results: E.H.O.-C., E.N.-L., S.P.-A., A.G.-A., C.C.-M., and E.M.M.; draft manuscript preparation: J.J.P.-C., E.H.O.-C. and E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data discussed in this study are available in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI—Mexico) for the support provided by the scholarship granted to Juan José Patiño Cruz through the “Becas Nacionales SECIHTI” program with CVU No. 1317558.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Farooq, M.; Rehman, A.; Pisante, M. Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security. In Innovations in Sustainable Agriculture; Farooq, M., Pisante, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–24. ISBN 978-3-030-23168-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ebabhi, A.; Adebayo, R. Nutritional values of vegetables. Vegetable Crops-Health Benefits and Cultivation,

1st ed.; Yildirim, E., Y., Erinci, M.; Eds.; EIntechOpen, London, United Kingdom, 2022; pp. 3-11.

- Salisu, M.A. , Ismail, F., Bamiro, N.B.; Luqman, H. (2024). Sustainable Agriculture for Food Safety, Security, and Sufficiency. In Agripreneurship and the Dynamic Agribusiness Value Chain. Olatidoye, O.P., Said, T.F.H. Eds.; Springer, Singapore Pte Ltd, 2024; pp. 29-60.

- Ahmed, M.; Rauf, M.; Mukhtar, Z.; Saeed, N.A. Excessive use of nitrogenous fertilizers: An unawareness causing serious threats to environment and human health. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 26983–26987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostria-Gallardo, E.; Bascuñán-Godoy, L.; Fernández Del-Saz, N. (2024). Nitrogen metabolism in crops and model plant species. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2024, 15, 1502273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, J.A.; Vega, A.; Bouguyon, E.; Krouk, G.; Gojon, A.; Coruzzi, G.; Gutiérrez, R.A. Nitrate transport, sensing, and responses in plants. Molecular plant 2016, 9(6), 837–856. [Google Scholar]

- The, S.V.; Snyder, R.; Tegeder, M. Targeting nitrogen metabolism and transport processes to improve plant nitrogen use efficiency. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2021, 11, 628366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, I.; Brown, P.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M.; Husted, S.; Kutman, B.Y.; Nikolic, M.; Rengel, Z.; Schmidt, S.B.; Zhao, F.-J. Chapter 7 - Micronutrients. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Plants, 4th ed.; Rengel, Z., Cakmak, I., White, P.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 283–385. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P.; Mishra, J.; Arora, N.K. Biofortification revisited: Addressing the role of beneficial soil microbes for enhancing trace elements concentration in staple crops. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 275, 127442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona, E.R.; Rojo, C.; Vergara Carmona, V. Nanomaterial-Based Biofortification: Potential Benefits and Impacts of Crops. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2024, 72(43), 23645–23670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichert, T.; Kurtz, A.; Steiner, U.; Goldbach, H.E. Size exclusion limits and lateral heterogeneity of the stomatal foliar uptake pathway for aqueous solutes and water-suspended nanoparticles. Physiologia plantarum. 2008, 134(1), 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzali, S.; Kiferle, C.; Perata, P. Iodine biofortification of crops: agronomic biofortification, metabolic engineering and iodine bioavailability. Current opinion in biotechnology. 2017, 44, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cezar, J.V.D.C.; Morais, E.G.D.; Lima, J.D.S.; Benevenute, P.A.N.; Guilherme, L.R.G. Iodine-enriched urea reduces volatilization and improves nitrogen uptake in maize plants. Nitrogen. 2024, 5(4), 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, B.; Rios, J.J.; Cervilla, L.M.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, E.; Rubio-Wilhelmi, M.M.; Rosales, M.A.; Ruiz, J.M. Iodine application affects nitrogen-use efficiency of lettuce plants (Lactuca sativa L.). Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil Plant Sci. 2011, 61, 378–383. [Google Scholar]

- Rey-Caramés, C.; Tardaguila, J.; Sanz-Garcia, A.; Chica-Olmo, M.; Diago, M.P. Quantifying spatio-temporal variation of leaf chlorophyll and nitrogen contents in vineyards. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 150, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šebesta, M.; Kolenčík, M.; Sunil, B.R.; Illa, R.; Mosnáček, J.; Ingle, A.P.; Urík, M. Field application of ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles on agricultural plants. Agronomy. 2021, 11(11), 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, T.N.V.K.V.; Sudhakar, P.; Sreenivasulu, Y.; Latha, P.; Munaswamy, V.; Reddy, K.R. ;... & Pradeep, T. Effect of nanoscale zinc oxide particles on the germination, growth and yield of peanut. Journal of plant nutrition 2012, 35(6), 905–927. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Cai, Y.; Li, X.; et al. High-nitrogen fertilizer alleviated adverse effects of drought stress on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Hosta ‘Guacamole’. BMC Plant Biology. 2024, 24, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortunato, S.; Nigro, D.; Paradiso, A.; Cucci, G.; Lacolla, G.; Trani, R.; Agrimi, G.; Blanco, A.; de Pinto, M.C.; Gadaleta, A. Nitrogen Metabolism at Tillering Stage Differently Affects the Grain Yield and Grain Protein Content in Two Durum Wheat Cultivars. Diversity 2019, 11, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Song, Q.; Li, X.; Zheng, H.; amp; Zhu, X. G. Would reducing chlorophyll content result in a higher photosynthesis nitrogen use efficiency in crops? Food and Energy Security. 2024, 13(4), e576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, C.; Dusenge, M.E.; Nyirambangutse, B.; Zibera, E.; Wallin, G.; Uddling, J. Contrasting dependencies of photosynthetic capacity on leaf nitrogen in early- and late-successional tropical montane tree species. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 500479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, P.; Campanile, G.; Parente, A.; Elia, A. Subirrigation vs drip-irrigation: effects on yield and quality of soilless grown cherry tomato. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2003, 78, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, E.; Ruiz, J.M.; Romero, L. Proline metabolism in response to nitrogen toxicity in fruit of French Bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L. cv Strike). Sci. Hortic. 2002, 93, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, I.E.; Trejo Téllez, L.I.; Ortega Ortiz, H.; Juárez Maldonado, A.; González Morales, S.; Companioni González, B.; Cabrera De la Fuente, M.; Benavides Mendoza, A. Comparison of Iodide, Iodate, and Iodine-Chitosan Complexes for the Biofortification of Lettuce. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas Mazhar, M.; Ishtiaq, M.; Hussain, I.; Parveen, A.; Hayat Bhatti, K.; Azeem, M.; Thind, S.; Ajaib, M.; Maqbool, M.; Sardar, T. Seed nano-priming with zinc oxide nanoparticles in rice mitigates drought and enhances agronomic profile. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farden, k.J.K. , Robertson, J.G. 1980. Methods for Evaluating Biological Nitrogen Fixation. Wiley, New York, pp. 265-314.

- Singh, R.P. , Srivastava, H.S., 1986. Increase in glutamate synthase activity in maize seedlings in response to nitrate and ammonium nitrogen. Physiol. Plant. 66, 413–416.

- Kaiser, J.J. , Lewis, O.A.H., 1984. Nitrate reductase and glutamine synthetase activity in leaves and roots of nitrate fed Helianthus annuus L. Plant Soil 70, 127–130.

- Hageman. R.H., Hucklesby, D.P., 1971. Nitrate reductase. Meth. Enzymol. 23, 497–503.

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemm, E.W.; Cocking, E.C.; Ricketts, R.E. The determination of amino-acids with ninhydrin. Analyst 1955, 80, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudáš, A. Graphical representation of data prediction potential: correlation graphs and correlation chains. Vis. Comput. 2024, 40, 6969–6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 15.2 User’s Guide; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Szarka, A.; Tomasskovics, B.; Bánhegyi, G. The ascorbate-glutathione-α-tocopherol triad in abiotic stress response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 4458–4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R.; Gulshad, L.; Haq, I.U.; Farooq, M.A.; Al-Farga, A.; Siddique, R.; Karrar, E. Nanotechnology: a novel tool to enhance the bioavailability of micronutrients. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 3354–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, B.; Rios, J.J.; Cervilla, L.M.; Sánchez-Rodriguez, E.; Ruiz, J.M.; Romero, L. Iodine biofortification and antioxidant capacity of lettuce: potential benefits for cultivation and human health. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2008, 152, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano-Macías, J.; Leija-Martínez, P.; et al. Use of iodine to biofortify and promote growth and stress tolerance in crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sularz, O.; Smoleń, S.; Koronowicz, A.; Kowalska, I.; Leszczyńska, T. Chemical composition of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) biofortified with iodine by KIO₃, 5-Iodo-, and 3.5-diiodosalicylic acid in a hydroponic cultivation. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavkiev, J.; Nabiev, S.; Azimov, A.; Khamdullaev, S.; Amanov, B.; Matniyazova, H.; Nurmetov, K. Correlation coefficients between physiology, biochemistry, common economic traits and yield of cotton cultivars under full and deficit irrigated conditions. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.; Arif, Y.; Mir, A.R.; Alam, P.; Hayat, S. Quercetin-mediated alteration in photosynthetic efficiency, sugar metabolism, elemental status, yield, and redox potential in two varieties of okra. Protoplasma 2024, 261, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubkina, N.; Moldovan, A.; Fedotov, M.; Kekina, H.; Kharchenko, V.; Folmanis, G.; Caruso, G. Iodine and selenium biofortification of chervil plants treated with silicon nanoparticles. Plants 2021, 10, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, T.; Indu, I.; Singhal, R.K.; Shabbir, R.; Shah, A.N.; Kumar, P.; Jinger, D.; Dharmappa, P.M.; Shad, M.A.; Saha, D.; Anuragi, H.; Adamski, R.; Siuta, D. Recent Advances in Agronomic and Physio-Molecular Approaches for Improving Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Crop Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 877544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fageria, N.K.; Baligar, V.C. Enhancing nitrogen use efficiency in crop plants. Adv. Agron. 2005, 88, 97–185. [Google Scholar]

- Anjum, S.A.; Xie, X.Y.; Wang, L.C.; Saleem, M.F.; Man, C.; Lei, W. Morphological, physiological and biochemical responses of plants to drought stress. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6, 2026–2032. [Google Scholar]

- Marslin, G.; Sheeba, C.J.; Franklin, G. Nanoparticles alter secondary metabolism in plants via ROS burst. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agüero-Esparza, M.; Villalobos-Cano, O.; Sanchez, E.; Perez-Alvarez, S.; Sida-Arreola, J.P.; Palacio-Marquez, A.; Ramirez-Estrada, C.A. Effectiveness of foliar application of biostimulants and nanoparticles on growth, nitrogen assimilation and nutritional content in green bean. Not. Sci. Biol. 2022, 14, 11261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza-Alonso, C.A.; Juárez-Maldonado, A.; González-Morales, S.; Cabrera-De la Fuente, M.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; Morales-Díaz, A.B.; Benavides-Mendoza, A. ZnO nanoparticles as potential fertilizer and biostimulant for lettuce. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnabosco, P.; Masi, A.; Shukla, R.; Bansal, V.; Carletti, P. Advancing the impact of plant biostimulants to sustainable agriculture through nanotechnologies. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Arias, D.; García-Machado, F.J.; Morales-Sierra, S.; García-García, A.L.; Herrera, A.J.; Valdés, F.; Borges, A.A. A beginner’s guide to osmoprotection by biostimulants. Plants 2021, 10, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallarita, A.V.; Golubkina, N.; De Pascale, S.; Sękara, A.; Pokluda, R.; Murariu, O.C.; Caruso, G. Effects of Selenium/Iodine Foliar Application and Seasonal Conditions on Yield and Quality of Perennial Wall Rocket. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabados, L.; Savouré, A. Proline: A Multifunctional Amino Acid. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Xu, J. Abiotic Stress Responses in Plant Roots: A Proteomics Perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, P.J.; Miflin, B.J. Nitrogen assimilation and its relevance to crop improvement. Annu. Plant Rev. 2011, 42, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Jan, R.; Asaf, S.; Numan, M.; Lubna; Kim, K. M. Plant Secondary Metabolite Biosynthesis and Transcriptional Regulation in Response to Biotic and Abiotic Stress Conditions. Agronomy 2021, 11, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, R.; Asaf, S.; Numan, M.; Lubna; Kim, K. -M. Plant Secondary Metabolite Biosynthesis and Transcriptional Regulation in Response to Biotic and Abiotic Stress Conditions. Agronomy 2021, 11, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).