Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

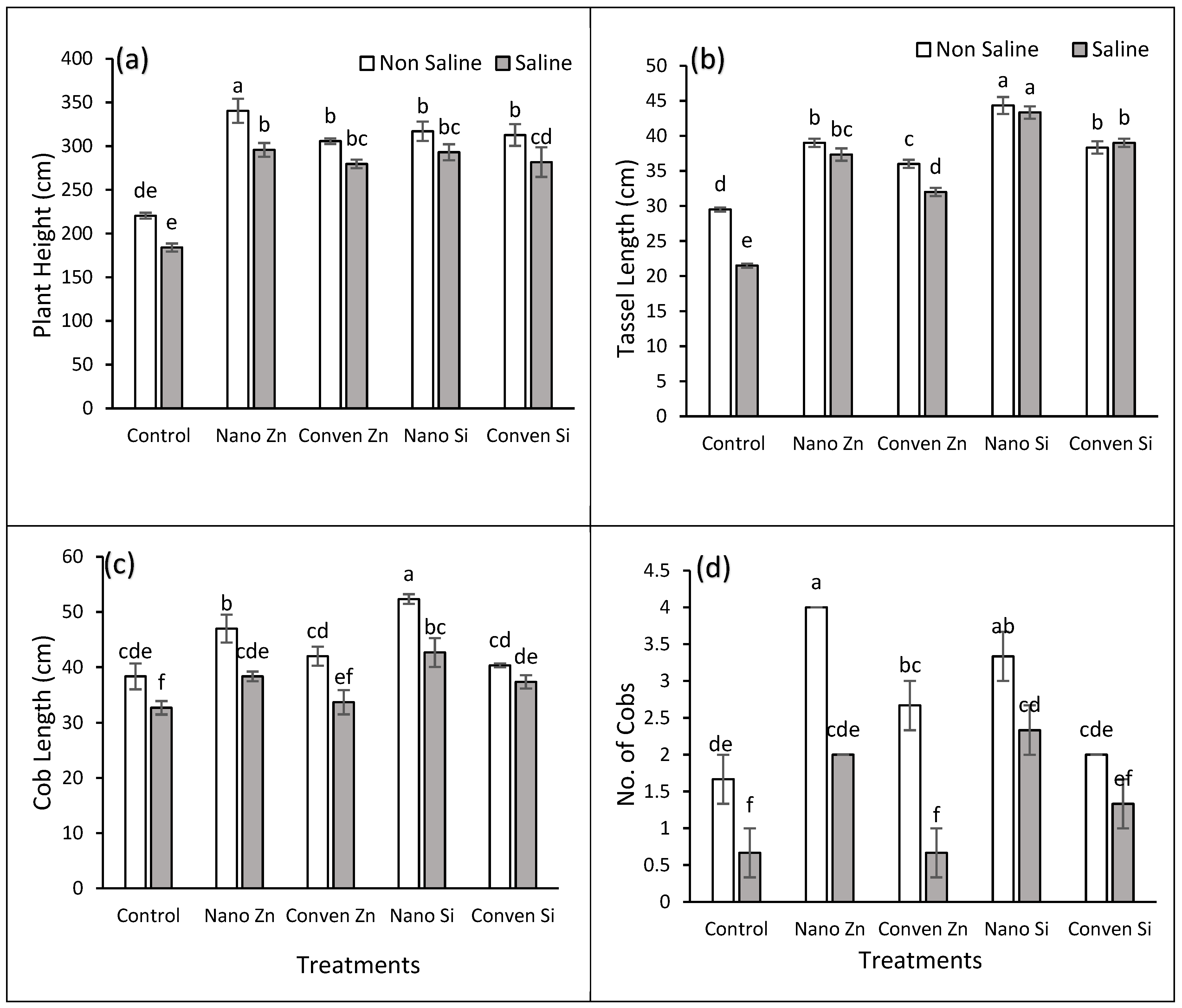

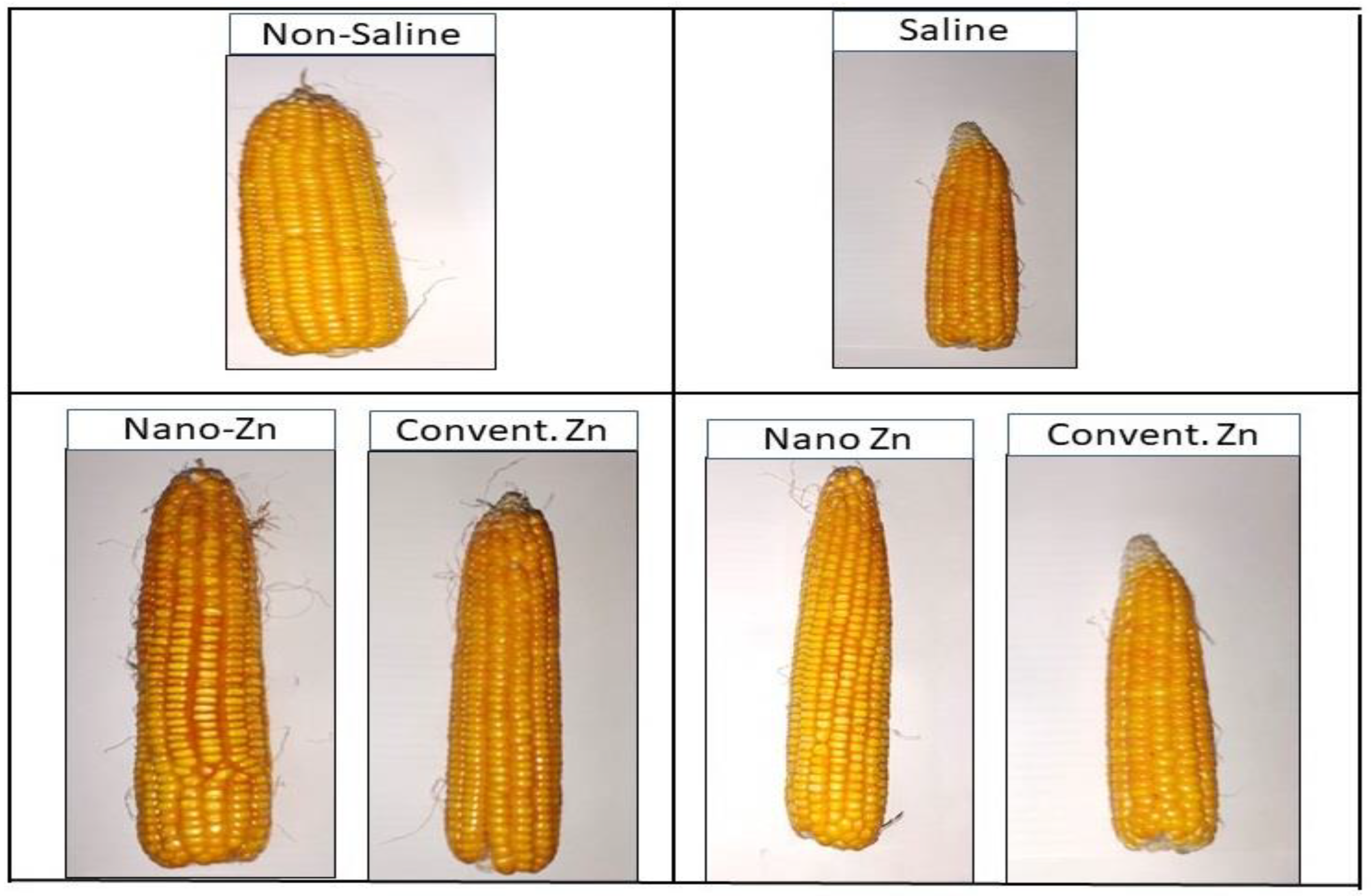

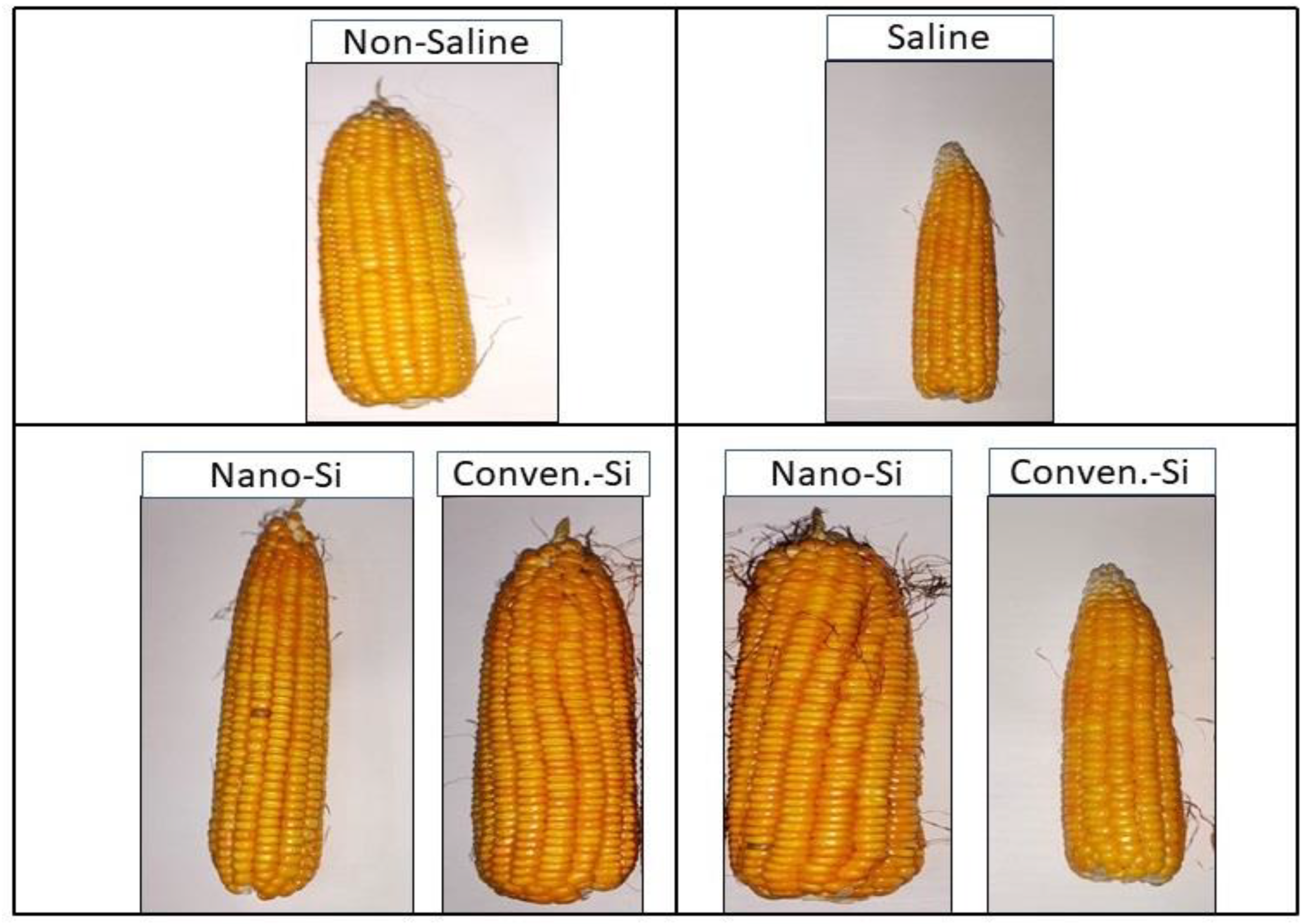

2.1. Agronomic Parameters

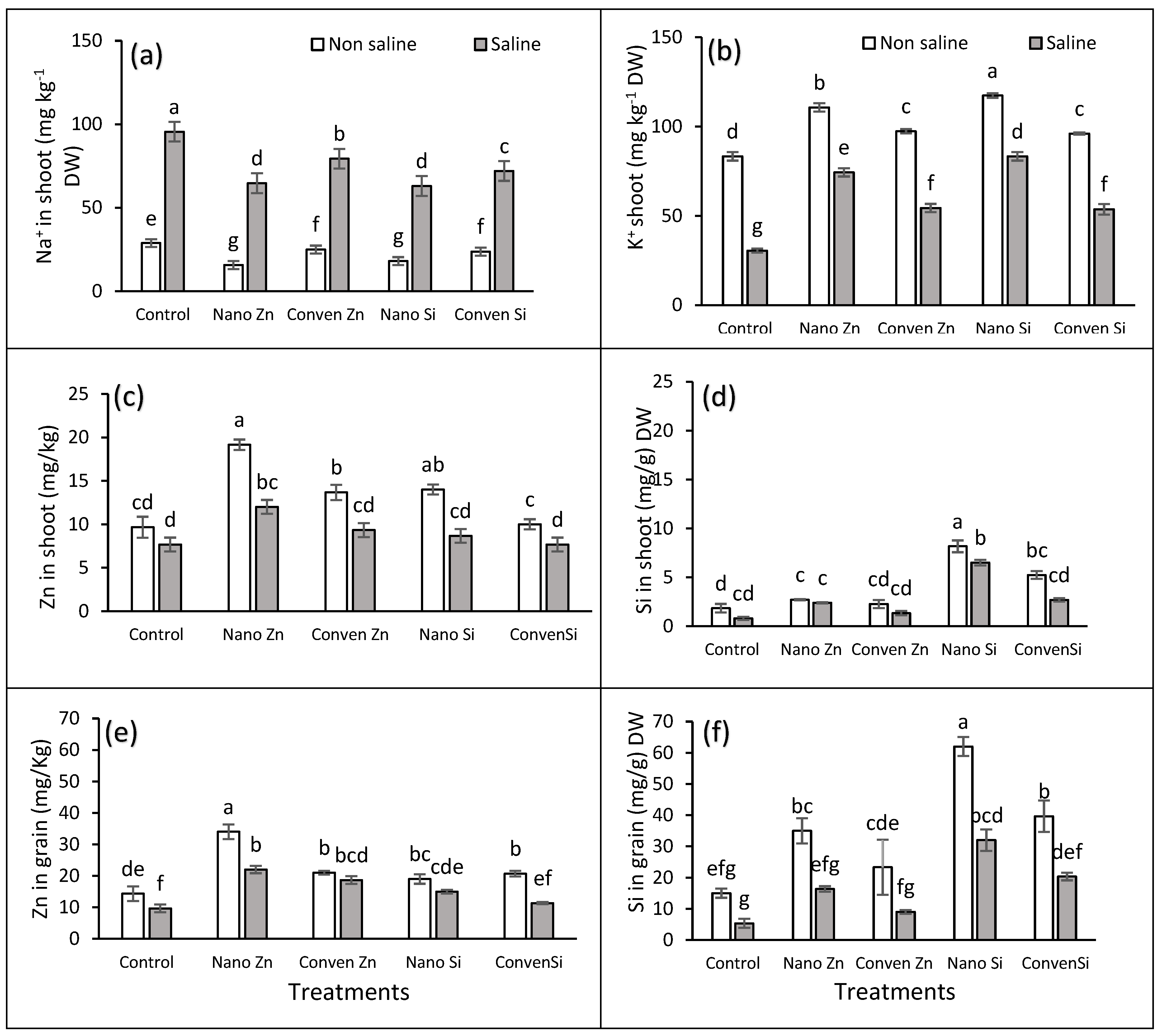

2.2. Chemical Parameters

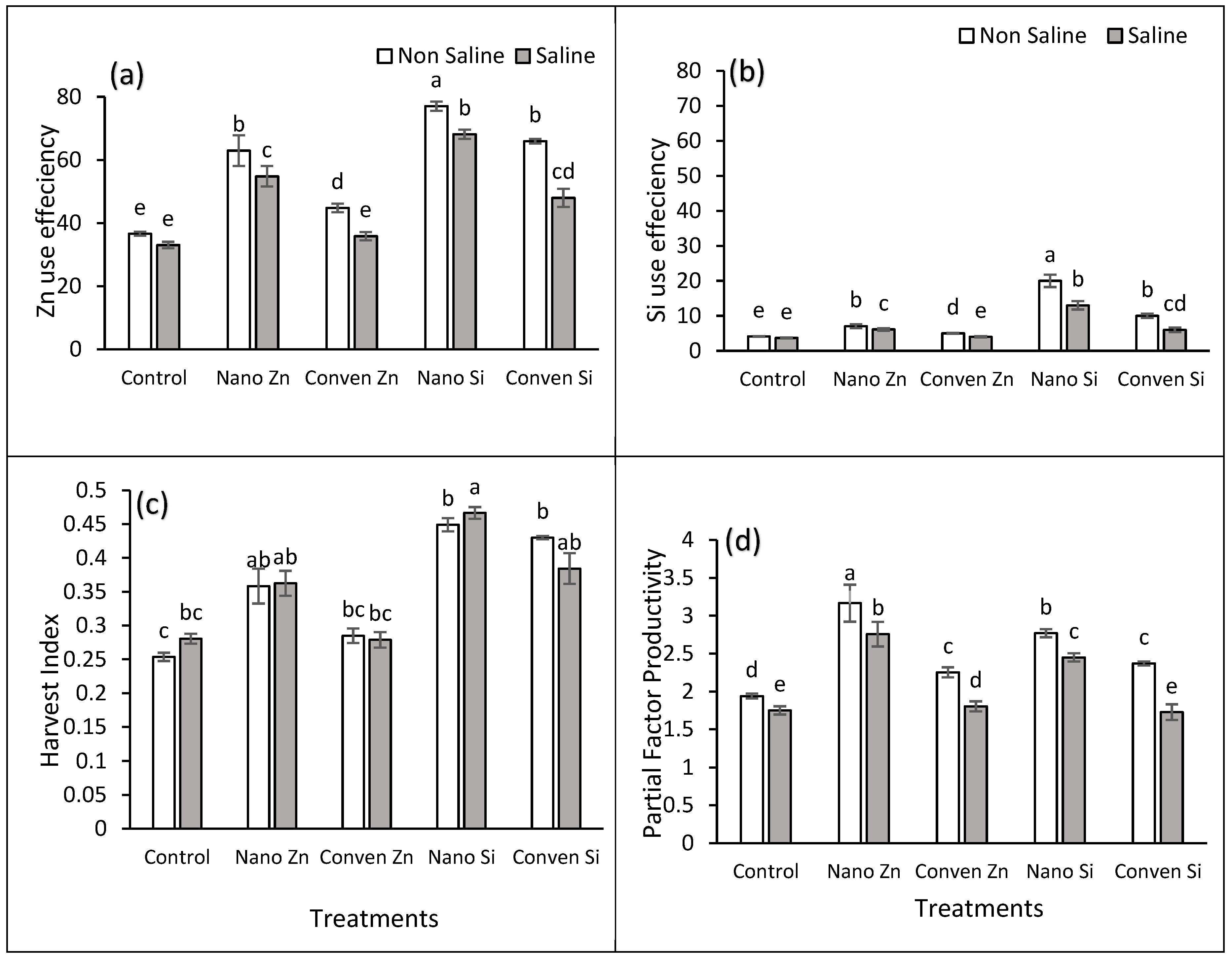

2.3. Nutrient Use Efficiency Parameters

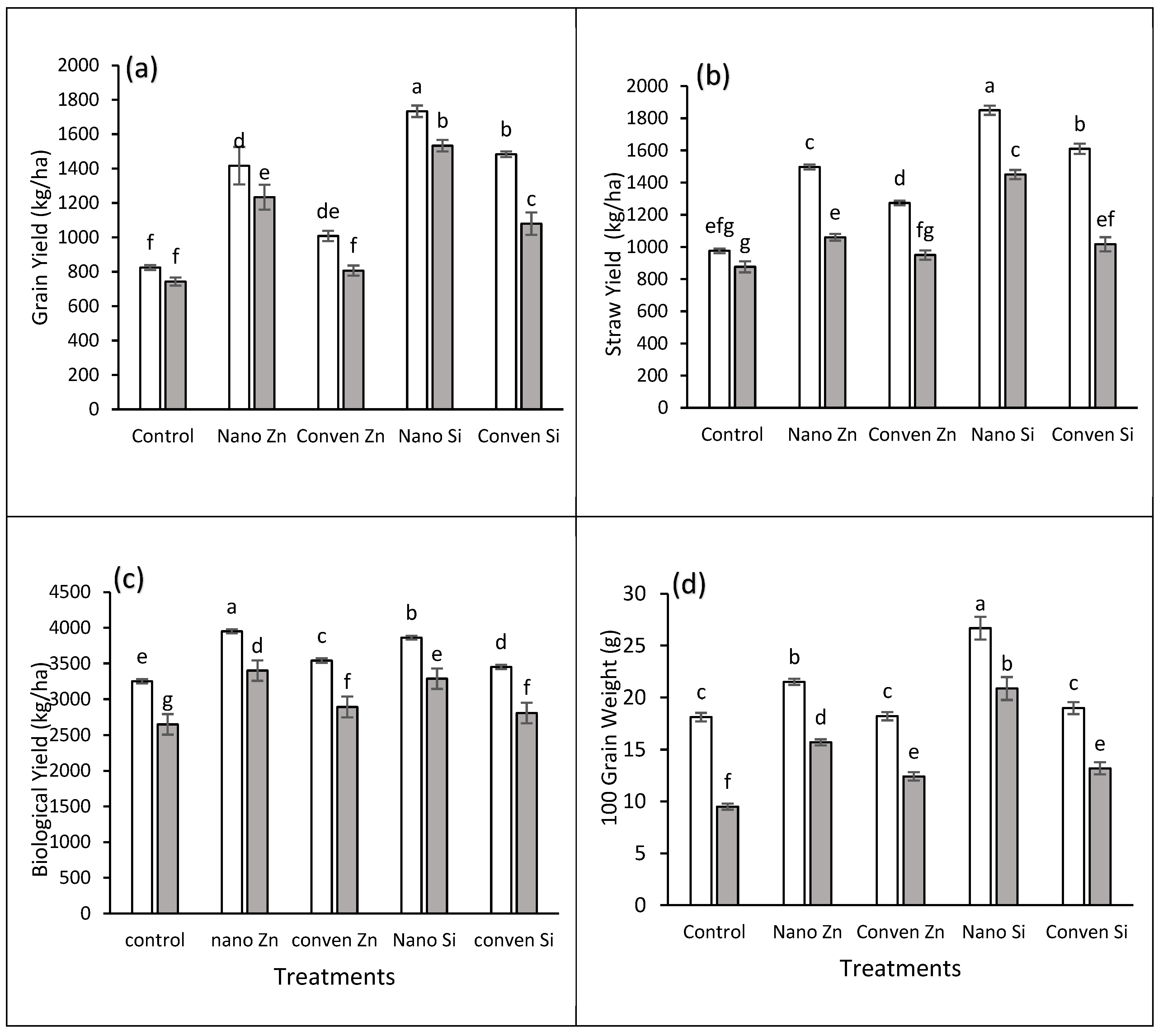

2.4. Yield Parameters

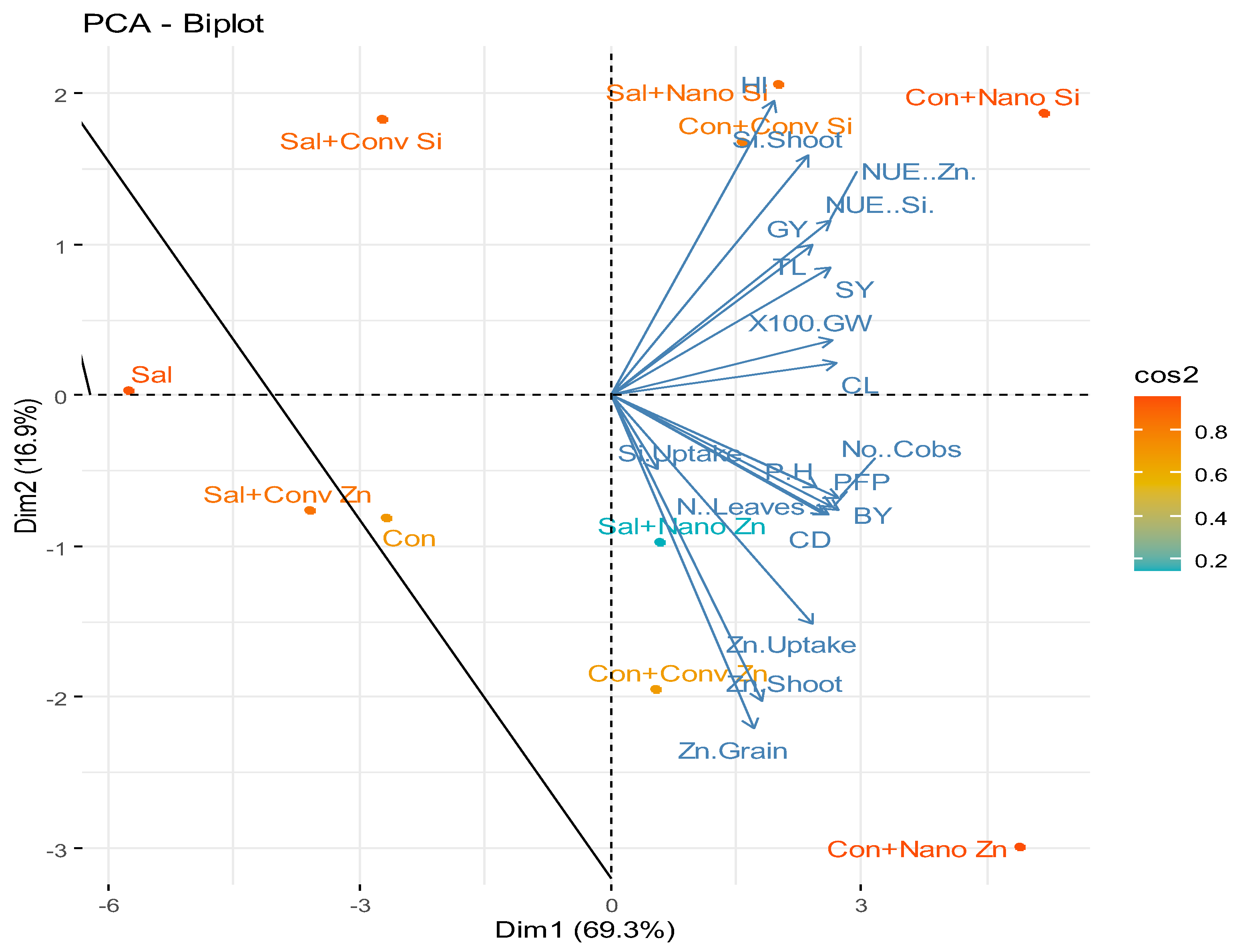

2.5. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

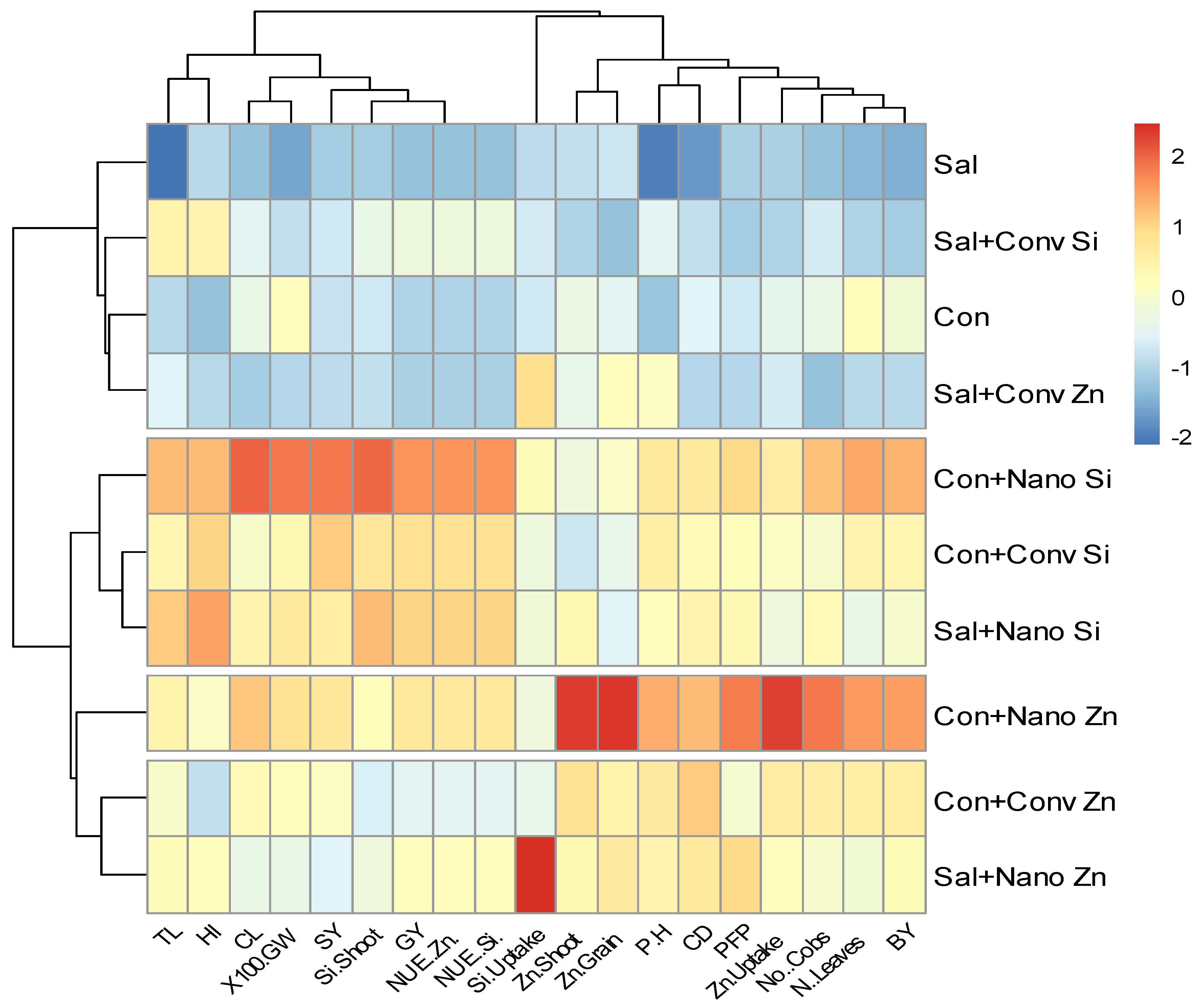

2.6. Heat Map Analysis

| Salinity | Treatments | Plant Height | Cob Length | Tassel length | No. of cobs |

Bio. Yield |

SY | GY | 100 GY |

| Control | T1 | 220.4 | 38.3 | 29.5 | 1.6 | 3250 | 976 | 824 | 18.13 |

| T2 | 340.3 | 47 | 39 | 4 | 3950 | 1497 | 1416 | 21.5 | |

| T3 | 305.7 | 42 | 36 | 2.6 | 3540 | 1273 | 1007 | 18.22 | |

| T4 | 307 | 52.3 | 44.3 | 3.3 | 3860 | 1850 | 1733 | 26.66 | |

| T5 | 301.6 | 40.3 | 38.3 | 2 | 3450 | 1610 | 1483 | 19 | |

| Mean | 294A | 44A | 37A | 2.73A | 3610A | 1441A | 1293A | 20.7A | |

| 10 dSm-1 | T1 | 184 | 32.66 | 21.5 | 0.66 | 2650 | 876 | 743 | 9.5 |

| T2 | 295.6 | 38.33 | 37.33 | 2 | 3400 | 1060 | 1233 | 15.7 | |

| T3 | 279.66 | 33.6 | 32 | 0.66 | 2893 | 950 | 806 | 12.42 | |

| T4 | 283 | 42.6 | 43.33 | 2.33 | 3286 | 1450 | 1533 | 20.8 | |

| T5 | 253.3 | 37.33 | 39 | 1.33 | 2810 | 1016 | 1080 | 13.2 | |

| Mean | 259B | 36B | 34B | 1.4B | 3008B | 1070B | 1079B | 14.3B | |

| Significance ANOVA | |||||||||

| Salinity Stress | * | ** | * | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Fertilizers Treatments | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |

| Interaction | NS | NS | *** | NS | NS | *** | NS | NS | |

| Salinity | Treatments |

Zn in shoot |

Si in shoot | Zn in grain |

Si in grain |

Na in shoot | K in shoot | ZnUE | SiUE | ||

| Control | T1 | 9.6 | 1.8 | 14.3 | 15.3 | 28.8 | 49.6 | 36.6 | 4.0 | ||

| T2 | 19.15 | 2.7 | 34 | 35 | 15.6 | 85 | 62.9 | 7.04 | |||

| T3 | 13.6 | 2.2 | 21 | 23.3 | 24.9 | 64.2 | 44.7 | 5.01 | |||

| T4 | 14 | 8.1 | 19 | 62 | 18 | 99.3 | 77.0 | 20.6 | |||

| T5 | 10 | 5.2 | 20.6 | 39.6 | 23.6 | 57.3 | 65.9 | 13 | |||

| Mean | 13.3A | 4.04A | 21.8A | 35A | 22A | 71A | 57A | 10A | |||

| 10 dSm-1 | T1 | 6.3 | 0.8 | 9.6 | 5.33 | 95.5 | 31 | 33.0 | 3.6 | ||

| T2 | 12 | 2.4 | 22 | 16.33 | 64.6 | 58.3 | 54.8 | 6.13 | |||

| T3 | 9.3 | 1.33 | 18.6 | 9 | 79.3 | 43 | 35.8 | 4.01 | |||

| T4 | 8.6 | 6.5 | 15 | 32 | 63 | 65.3 | 68.14 | 9.66 | |||

| T5 | 7.6 | 2.68 | 11.3 | 20.33 | 72 | 50.6 | 48 | 5.9 | |||

| Mean | 8.8A | 2.74B | 15.33B | 16.6B | 79B | 50B | 47B | 5.8B | |||

| Significance ANOVA | |||||||||||

| Salinity Stress | NS | * | ** | *** | ** | ** | ** | ** | |||

| Fertilizers Treatments | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | |||

| Interaction | NS | ** | * | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |||

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Nanoparticle Synthesis and Characterization

4.2. Study Site and Pre-Experiment Soil Analysis

4.3. Soil Preparation and Fertilizer Application

4.4. Planting and Crop Management

4.5. Harvesting and Agronomic Measurements

4.6. Chemical Analysis of Plant Samples

4.7. Nutrient Uptake and Efficiency

4.8. Yield and Quality Parameters

4.9. Experimental Design

| Sr. No. | Name | Unit | Pars Soil | UAF Soil | Reference |

| 1 | ECe | dS m-1 | 9.1 | 1.8 | [56] |

| 2 | pHs | ---- | 8.1 | 8.4 | [56] |

| 3 | (CO3-) | me L-1 | nil | nil | [57] |

| 4 | (HCO3-) | me L-1 | 4.1 | 3.8 | [57] |

| 5 | Ca2++Mg2+ | me L-1 | 16.8 | 7.5 | [58] |

| 6 | (SAR) | me L-1 | 16.89 | 2.1 | [59] |

| 7 | Saturation percentage | Percentage (%) | 37 | 35 | [60] |

| 8 | Texture | Sandy clay loam | Sandy Loam | [61] | |

| 9 | Organic matter | Percentage (%) | 0.83 | 0.9 | [62] |

| 10 | Nitrogen (N) | Percentage (%) | 0.061 | 0.05 | [63] |

| 11 | Phosphorus (P) | ppm | 9.32 | 7.8 | [64] |

| 12 | Potassium (K) | ppm | 129 | 125 | [65] |

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Serraj:, R.; Krishnan, L.; Pingali, P. Agriculture and food systems to 2050: a synthesis. Agric. Food Syst. 2019, 2050, 3–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. M.; Salem, H. M. Salinity-induced desertification in oasis ecosystems: challenges and future directions. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanga, D. L.; Mwamahonje, A. S.; Mahinda, A. J. Soil salinization under irrigated farming: A threat to sustainable food security and environment in semi-arid tropics. Unpublished.

- Sári, D.; Ferroudj, A.; Abdalla, N.; El-Ramady, H.; Dobránszki, J.; Prokisch, J. Nano-Management approaches for Salt Tolerance in plants under field and in Vitro conditions. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokisch, J.; Ferroudj, A.; Labidi, S.; El-Ramady, H.; Brevik, E. C. Biological Nano-Agrochemicals for Crop Production as an Emerging Way to Address Heat and Associated Stresses. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zörb, C.; Geilfus, C. M.; Dietz, K. J. Salinity and crop yield. Plant Biol. 2019, 21, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Bano, A.; Khan, N. Climate change and salinity effects on crops and chemical communication between plants and plant growth-promoting microorganisms under stress. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 618092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Islam, M.; Hasan, M.; Hafeez, A. S. M. G.; Chowdhury, M.; Pramanik, M.; Iqbal, M.; Erman, M.; Barutcular, C.; Konuşkan, Ö.; Dubey, A. Salinity stress in maize: consequences, tolerance mechanisms, and management strategies. OBM Genet. 2024, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurabh, K.; Prakash, V.; Dubey, A. K.; Ghosh, S.; Kumari, A.; Sundaram, P. K.; Jeet, P.; Sarkar, B.; Upadhyaya, A.; Das, A.; Kumar, S. Enhancing sustainability in agriculture with nanofertilizers. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, A.; Salah, M. A.; Ali, M.; Ali, B.; Saleem, M. H.; Samarasinghe, K. G. B. A.; De Silva, S. I. S.; Ercisli, S.; Iqbal, N.; Anas, M. Advancing Agriculture: Harnessing Smart Nanoparticles for Precision Fertilization. BioNanoScience 2024, 14, 3846–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffan, M. M.; Koriem, M. A.; El-Henawy, A.; El-Mahdy, S.; El-Ramady, H.; Elbehiry, F.; Omara, A. E.-D.; Bayoumi, Y.; Badgar, K.; Prokisch, J. Sustainable Production of Tomato Plants (Solanum lycopersicum L.) under Low-Quality Irrigation Water as Affected by Bio-Nanofertilizers of Selenium and Copper. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3236. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M.; Liu, S.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, T.; Chen, W. Recent advances in stimuli-response mechanisms of nano-enabled controlled-release fertilizers and pesticides. Eco-Environ. Health 2023, 2, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, T.; Gopinath, S. C. B. Nanosensors: Recent perspectives on attainments and future promise of downstream applications. Process Biochem. 2022, 117, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manju, K.; Ranjini, H. K.; Raj, S. N.; Nayaka, S. C.; Lavanya, S. N.; Chouhan, R. S.; Prasad, M. N. N.; Satish, S.; Ashwini, P.; Harini, B. P. Nanoagrosomes: Future prospects in the management of drug resistance for sustainable agriculture. Plant Nano Biol. 2023, 4, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Garg, V. K.; Chhillar, A. K.; Rana, J. S. Recent advances in nanotechnology for the improvement of conventional agricultural systems: A review. Plant Nano Biol. 2023, 4, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, I.; Gogoi, B.; Sharma, B.; Borah, D. Role of metal-nanoparticles in farming practices: An insight. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M. M. F. Anthocyanins: Biotechnological targets for enhancing crop tolerance to salinity stress. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 319, 112182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Bharati, R.; Kubes, J.; Popelkova, D.; Praus, L.; Yang, X.; Severova, L.; Skalicky, M.; Brestic, M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles application alleviates salinity stress by modulating plant growth, biochemical attributes, and nutrient homeostasis in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1432258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Huang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Xu, Y.; He, Y.; Nikolic, M.; Zhu, Z. Silicon nanoparticles in sustainable agriculture: synthesis, absorption, and plant stress alleviation. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1393458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherpa, D.; Kumar, S.; Mishra, S. Response of Different Doses of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles in Early Growth of Mung Bean Seedlings to Seed Priming under Salinity Stress Condition. Legume Res.-Int. J. 2024, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwini, M. N.; Gajera, H. P.; Hirpara, D. G.; Savaliya, D. D.; Kandoliya, U. K. Comparative impact of seed priming with zinc oxide nanoparticles and zinc sulfate on biocompatibility, zinc uptake, germination, seedling vitality, and antioxidant modulation in groundnut. J. Nanopart. Res. 2024, 26, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avestan, S.; Ghasemnezhad, M.; Esfahani, M.; Byrt, C. S. Application of nano-silicon dioxide improves salt stress tolerance in strawberry plants. Agronomy 2019, 9, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. X.; Gong, H. J.; Yin, J. L. Role of silicon in mediating salt tolerance in plants: a review. Plants 2019, 8, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.; Islam, M.; Hasan, M.; Hafeez, A. S. M. G.; Chowdhury, M.; Pramanik, M.; Iqbal, M.; Erman, M.; Barutcular, C.; Konuşkan, Ö.; Dubey, A. Salinity stress in maize: consequences, tolerance mechanisms, and management strategies. OBM Genet. 2024, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Hussain, M.; Wakeel, A.; Siddique, K. H. Salt stress in maize: effects, resistance mechanisms, and management. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Hussain, S.; Qayyaum, M. A.; Ashraf, M.; Saifullah, S. The response of maize physiology under salinity stress and its coping strategies. Plant Stress Physiol. 2020, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Arif, Y.; Singh, P.; Siddiqui, H.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. Salinity-induced physiological and biochemical changes in plants: An omic approach towards salt stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 156, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Irfan, M.; Ahmad, A.; Hayat, S. Causes of salinity and plant manifestations to salt stress: a review. J. Environ. Biol. 2011, 32, 667. [Google Scholar]

- Maiti, R. K.; Singh, V. P. Physiological basis of maize growth and productivity–A review. Farm. Manag. 2017, 2, 59–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkharabsheh, H. M.; Seleiman, M. F.; Hewedy, O. A.; Battaglia, M. L.; Jalal, R. S.; Alhammad, B. A.; Schillaci, C.; Ali, N.; Al-Doss, A. Field crop responses and management strategies to mitigate soil salinity in modern agriculture: A review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S. F.; Martins, D.; Agacka-Mołdoch, M.; Czubacka, A.; de Sousa Araújo, S. Strategies to alleviate salinity stress in plants. Salinity Responses Toler. Plants 2018, 1, 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Sharma, A.; Singh, O.; Rajput, V. D.; Movsesyan, H. S.; Minkina, T.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M.; Singh, R. K.; Singh, S.; Sousa, J. R. In-depth exploration of nanoparticles for enhanced nutrient use efficiency and abiotic stresses management: present insights and future horizons. Plant Stress 2024, 100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, A.; Pitann, B.; Zafar, M. M.; Farooq, M. A.; Haroon, M.; Nawaz, A.; Wahab, S. W.; Saqib, Z. A. Nanotechnology for climate change mitigation: Enhancing plant resilience under stress environments. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2024, 187, 604–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, A.; Saqib, Z. A.; Akhtar, J.; Aslam, Z.; Pitann, B.; Hossain, M. S.; Mühling, K. H. Zinc and Silicon Nano-Fertilizers Influence Ionomic and Metabolite Profiles in Maize to Overcome Salt Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Agrawal, S.; Rajput, V. D.; Ghazaryan, K.; Yesayan, A.; Minkina, T.; Zhao, Y.; Petropoulos, D.; Kriemadis, A.; Papadakis, M.; Alexiou, A. Nanoparticles in revolutionizing crop production and agriculture to address salinity stress challenges for a sustainable future. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, A.; Saqib, Z. A.; Nawaz, A.; Amir, K. Z.; Ahmad, I.; Hamza, A.; Mühling, K. H. Nanofertilizers Benefited Maize to Cope Oxidative Stress under Saline Environment. Plant Nano Biol. 2025, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, P.; Roy, S. Nanosilica facilitates silica uptake, growth and stress tolerance in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 157, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, J. J.; Martínez-Ballesta, M. C.; Ruiz, J. M.; Blasco, B.; Carvajal, M. Silicon-mediated improvement in plant salinity tolerance: the role of aquaporins. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, C.; Chen, Q. Architecture and autoinhibitory mechanism of the plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter SOS1 in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryam, S.; Gul, A. The mechanism of silicon transport in plants. In Plant Metal and Metalloid Transporters; Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, 2022; pp. 245–273.

- Singhal, R. K.; Fahad, S.; Kumar, P.; Choyal, P.; Javed, T.; Jinger, D.; Singh, P.; Saha, D.; Bose, B.; Akash, H. Beneficial elements: New players in improving nutrient use efficiency and abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 100, 237–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Shan, R.; Shi, Y.; Li, H.; Xue, L.; Song, Y.; Jiang, M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles alleviate salt stress in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) by adjusting Na+/K+ ratio and antioxidative ability. Life 2024, 14, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, J. Y.; Rao, S.; Huang, X.; Liu, X.; Cheng, S.; Xu, F. Interaction between selenium and essential micronutrient elements in plants: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 853, 158673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, R.; Xu, J.; Huang, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z. Unlocking Zn biofortification: leveraging high-Zn wheat and rhizospheric microbiome interactions in high-pH soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2024, 60, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H.; Kasote, D. M. Nano-Priming for Inducing Salinity Tolerance, Disease Resistance, Yield Attributes, and Alleviating Heavy Metal Toxicity in Plants. Plants 2024, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zexer, N.; Kumar, S.; Elbaum, R. Silica deposition in plants: Scaffolding the mineralization. Ann. Bot. 2023, 131, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Badri, A. M.; Batool, M.; Mohamed, I. A.; Agami, R.; Elrewainy, I. M.; Wang, B.; Zhou, G. Role of phytomelatonin in promoting ion homeostasis during salt stress. In Melatonin: Role in Plant Signaling, Growth and Stress Tolerance; Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2023; pp. 313–342.

- Rajput, V. D.; Minkina, T.; Feizi, M.; Kumari, A.; Khan, M.; Mandzhieva, S.; Sushkova, S.; El-Ramady, H.; Verma, K. K.; Singh, A.; Hullebusch, E. D. V. Effects of silicon and silicon-based nanoparticles on rhizosphere microbiome, plant stress and growth. Biology 2021, 10, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surendar, K. K.; Raja, R. K.; Sritharan, N.; Ravichandran, V.; Kannan, M. Impact of Nanosilica on Anatomical, Morpho-Physiological and Yield Characters of Rice (Oryza sativa L. ) For Drought Tolerance–A Review. Int. J. Bot. Hortic. Res. 2024, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Madhoor, H. A. A.; Faisal, M. Z. Effect of the use of micro-nano fertilizers, normal micro fertilizer and gibberellic acid and their interference in some growth, chemical, medicinal characteristics and yield in fenugreek (Trigonella foenum graecum L.). Plant Arch. 2020, 20, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Shoukat, A.; Pitann, B.; Hossain, M. S.; Saqib, Z. A.; Nawaz, A.; Mühling, K. H. Zinc and silicon fertilizers in conventional and nano-forms: Mitigating salinity effects in maize (Zea mays L.). J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2024, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, G. W.; Bauder, J. W. Particle-size analysis. Methods Soil Anal. Part 1 Phys. Miner. Methods 1986, 5, 383–411. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, W. L.; Norvell, W. Development of a DTPA soil test for zinc, iron, manganese, and copper. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1978, 42, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraska, J. E.; Breitenbeck, G. A. Simple, robust method for quantifying silicon in plant tissue. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2010, 41, 2075–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, R. K.; Nagaraju, B.; Govinda, K.; Kumar, S. N. U.; Basavaraja, P. K.; Saqeebulla, H. M.; Gangamrutha, G. V.; Srivastava, S.; Dey, P. Soil test crop response nutrient prescription equations for improving soil health and yield sustainability—a long-term study under Alfisols of southern India. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1439523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, R. G. D.; Torrie, J. H.; Dickey, D. A. Principles and Procedures of Statistics. A Biometrical Approach, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, J.; Estefan, G.; Rashid, A. Soil and Plant Analysis Laboratory Manual; ICARDA: 2001.

- Fordham, A. W. Determination of dissolved carbonate/bicarbonate in the presence of sulfide. Soil Res. 1992, 30, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K. L.; Bray, R. H. Determination of calcium and magnesium in soil and plant material. Soil Sci. 1951, 72, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harron, W. R. A.; Webster, G. R.; Cairns, R. R. Relationship between exchangeable sodium and sodium adsorption ratio in a solonetzic soil association. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1983, 63, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, E. C.; Trout, A. M. Analysis of thrust augmentation of turbojet engines by water injection at compressor inlet including charts for calculating compression processes with water injection. NACA-TR 1951, 1006.

- Bouyoucos, G. J. Hydrometer method improved for making particle size analyses of soils. Agron. J. 1962, 54, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I. A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldahl, J. A new method for the determination of nitrogen in organic substances. Z. Anal. Chem. 1883, 22, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S. R.; Cole, C. V.; Watanabe, F. S.; Dean, L. A. Estimation of available phosphorus in soils by extraction with sodium bicarbonate. USDA Circ. 1954, 939. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C. H.; Steinbergs, A. Soil sulfur fractions as chemical indices of available sulfur in some Australian soils. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1941, 1, 340–35. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).