Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

02 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

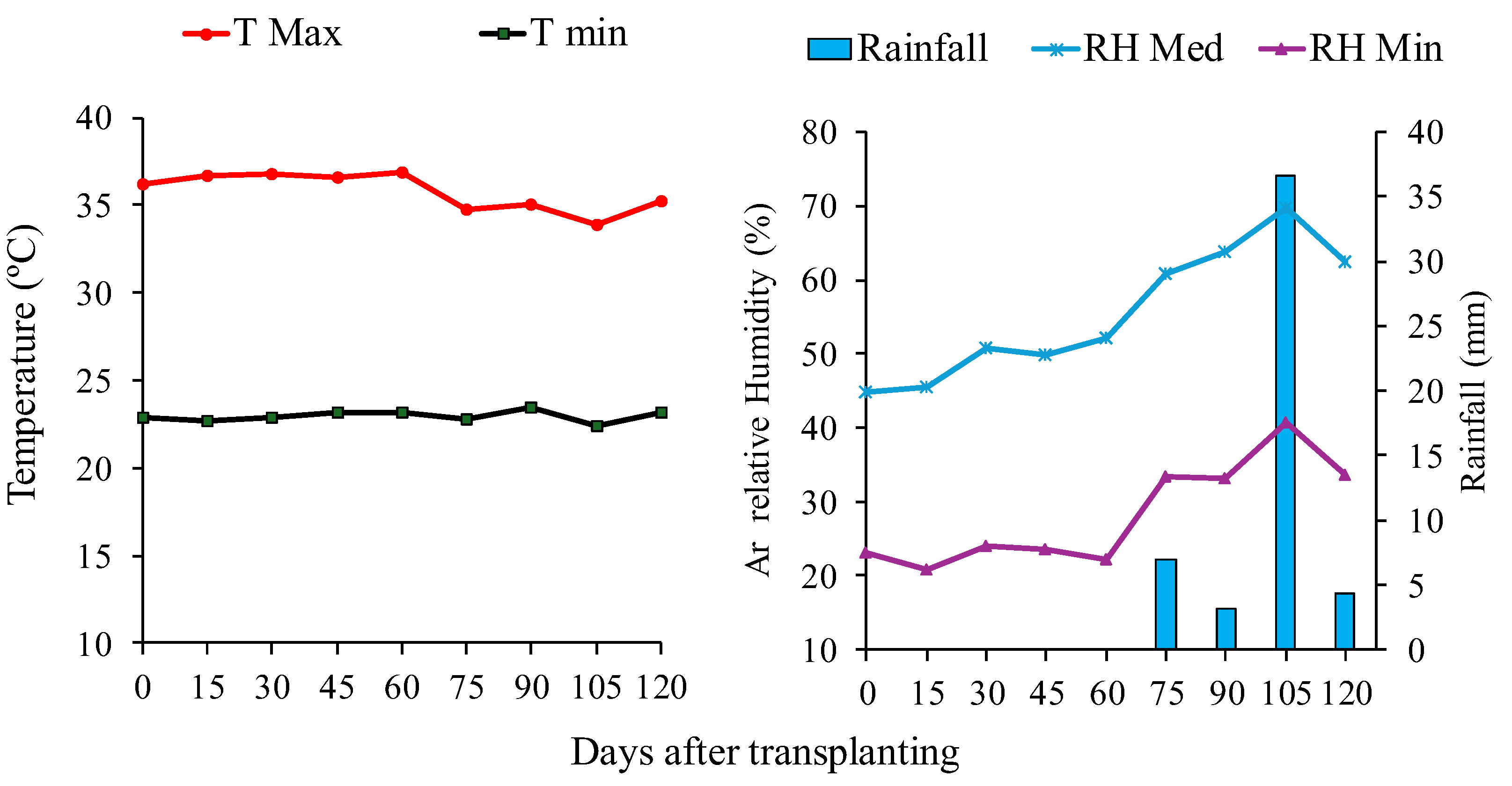

2.1. Characterization of the Experimental Area

2.2. Treatments and Experimental Design

2.3. Seedling Transplanting

2.4. Application of Treatments with Iron and Zinc Sources

2.5. Irrigation Depths Application

2.6. Cultural Practices and Phytosanitary Control

2.7. Evaluated Variables

2.7.1. Plant Growth

2.7.2. Gas Exchange and Photosynthetic Pigments

2.7.3. Fruit Yield

2.7.4. Mineral Nutrients Content in Fruits

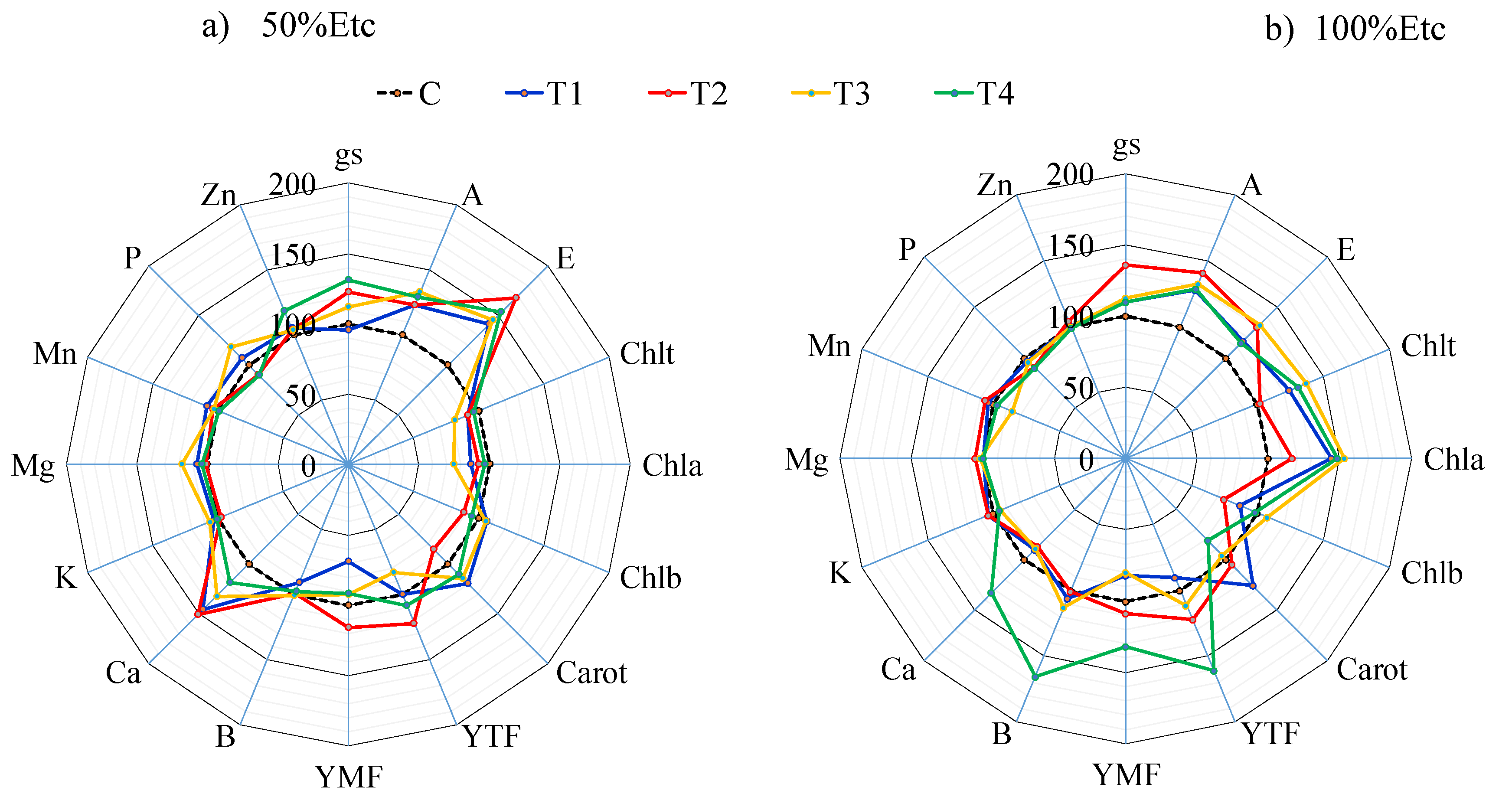

2.7.5. Radar Chart

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

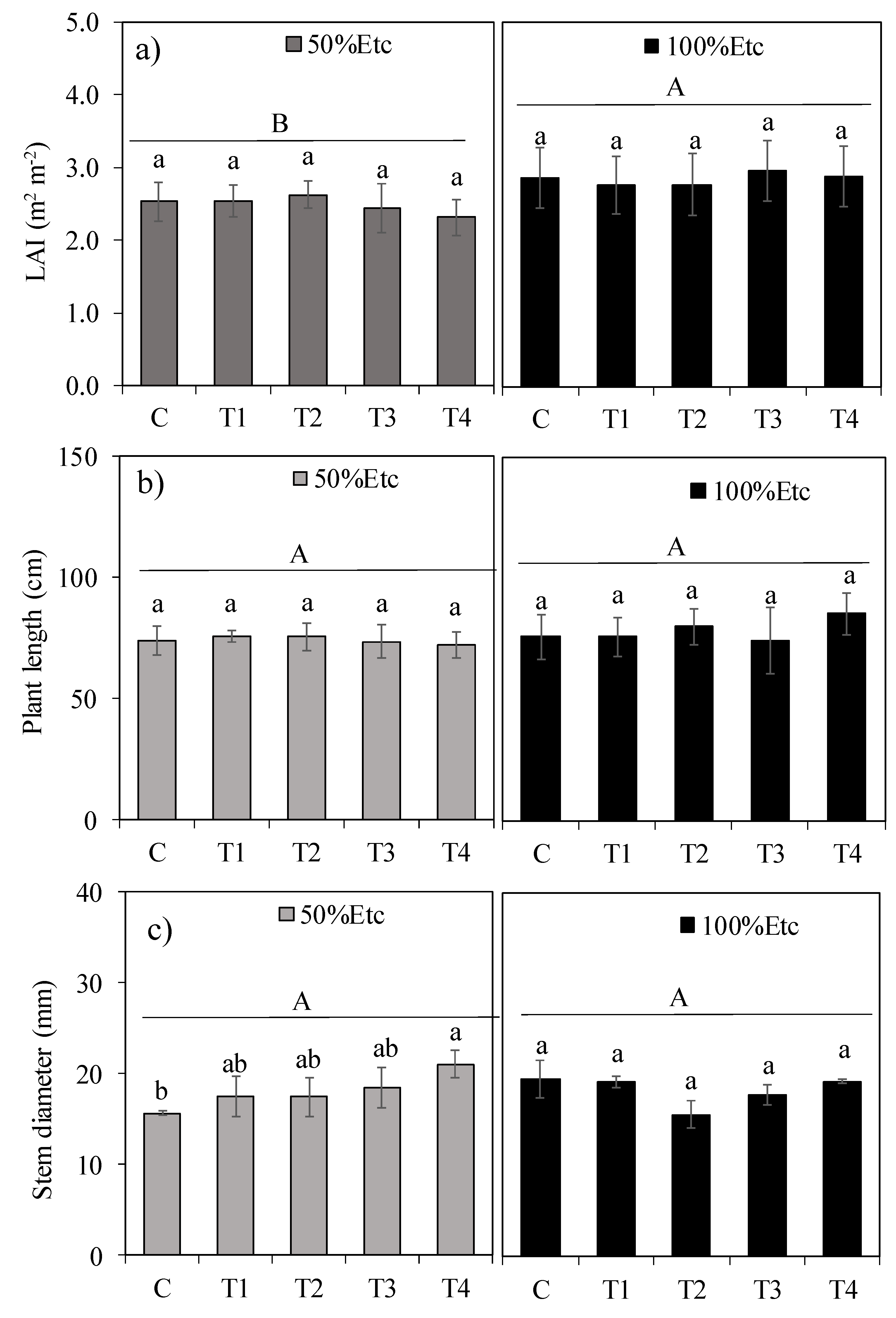

3.1. Plant Growth

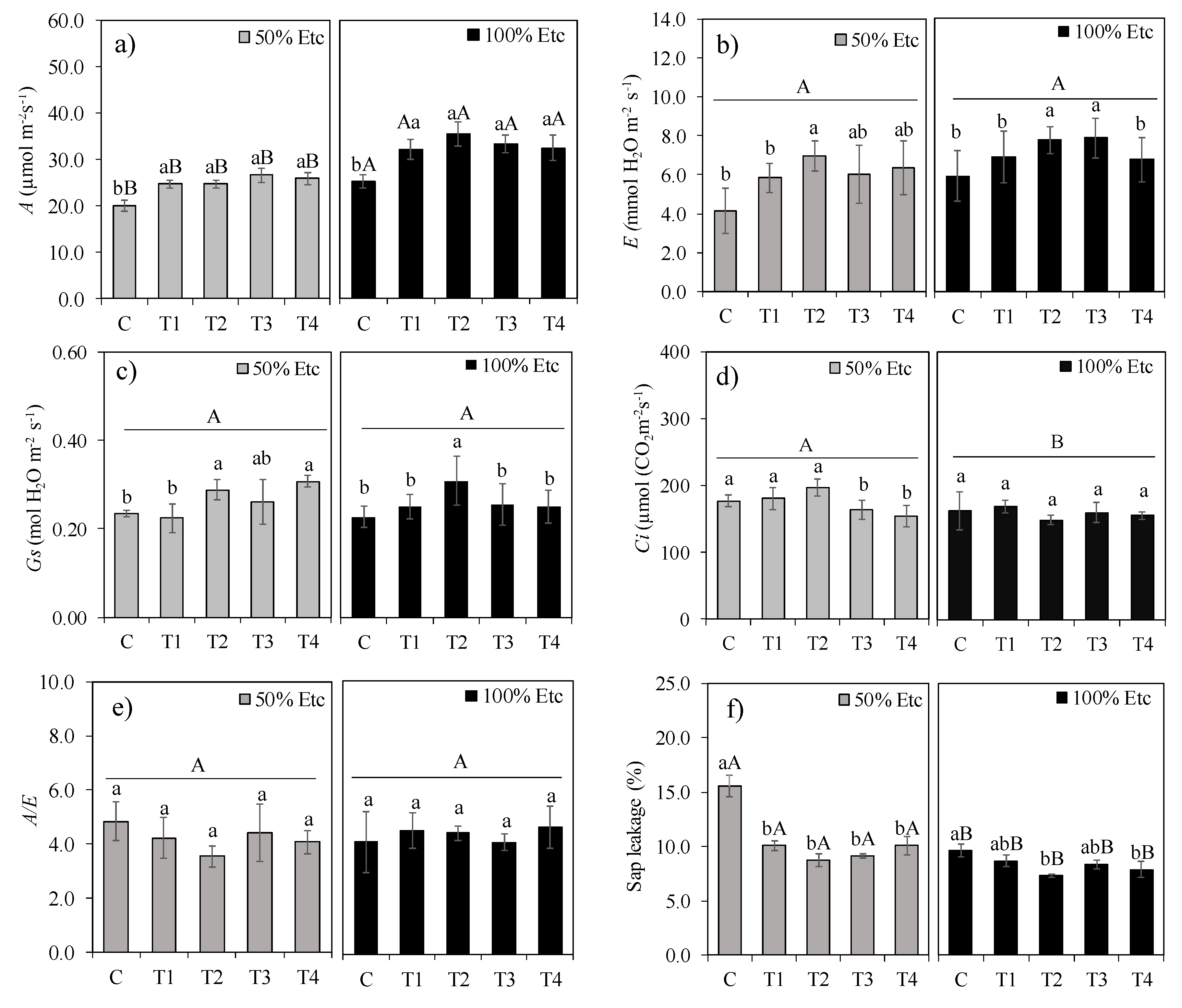

3.2. Gas Exchange, Photosynthetic Pigments, and Electrolyte Leakage

3.3. Gas Exchange Parameters

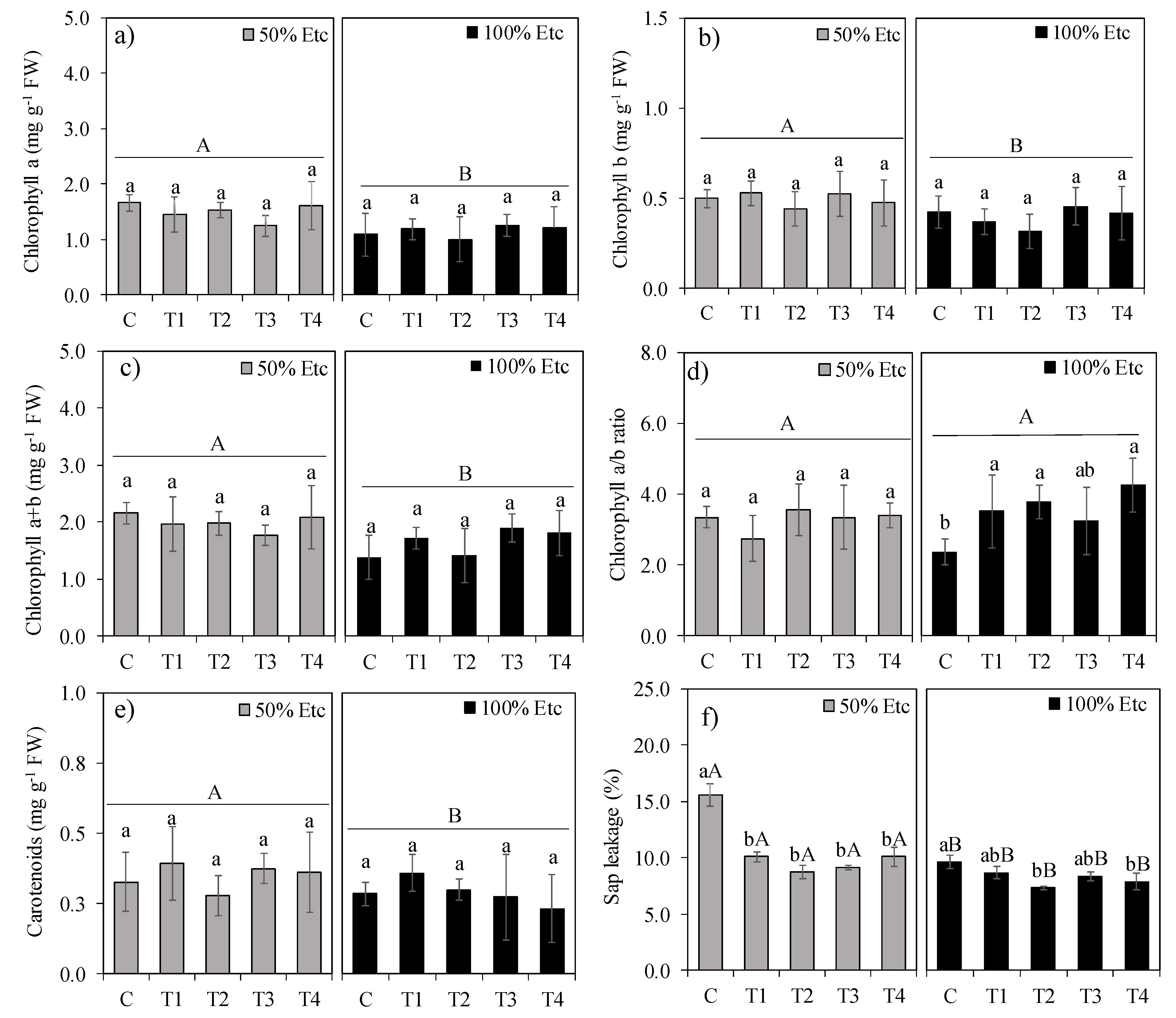

3.4. Photosynthetic Pigments and Electrolyte Leakage

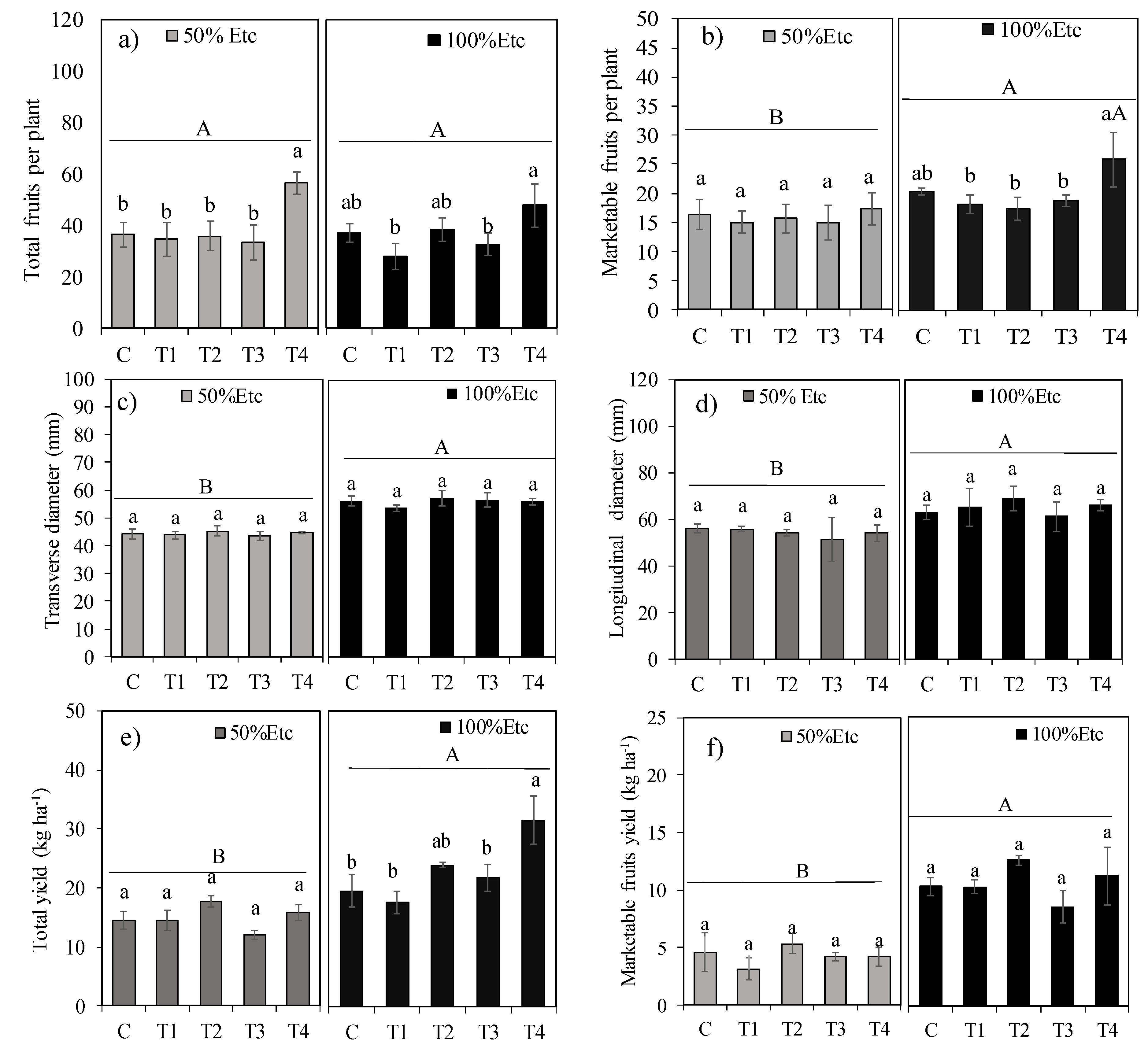

3.5. Fruit Productivity

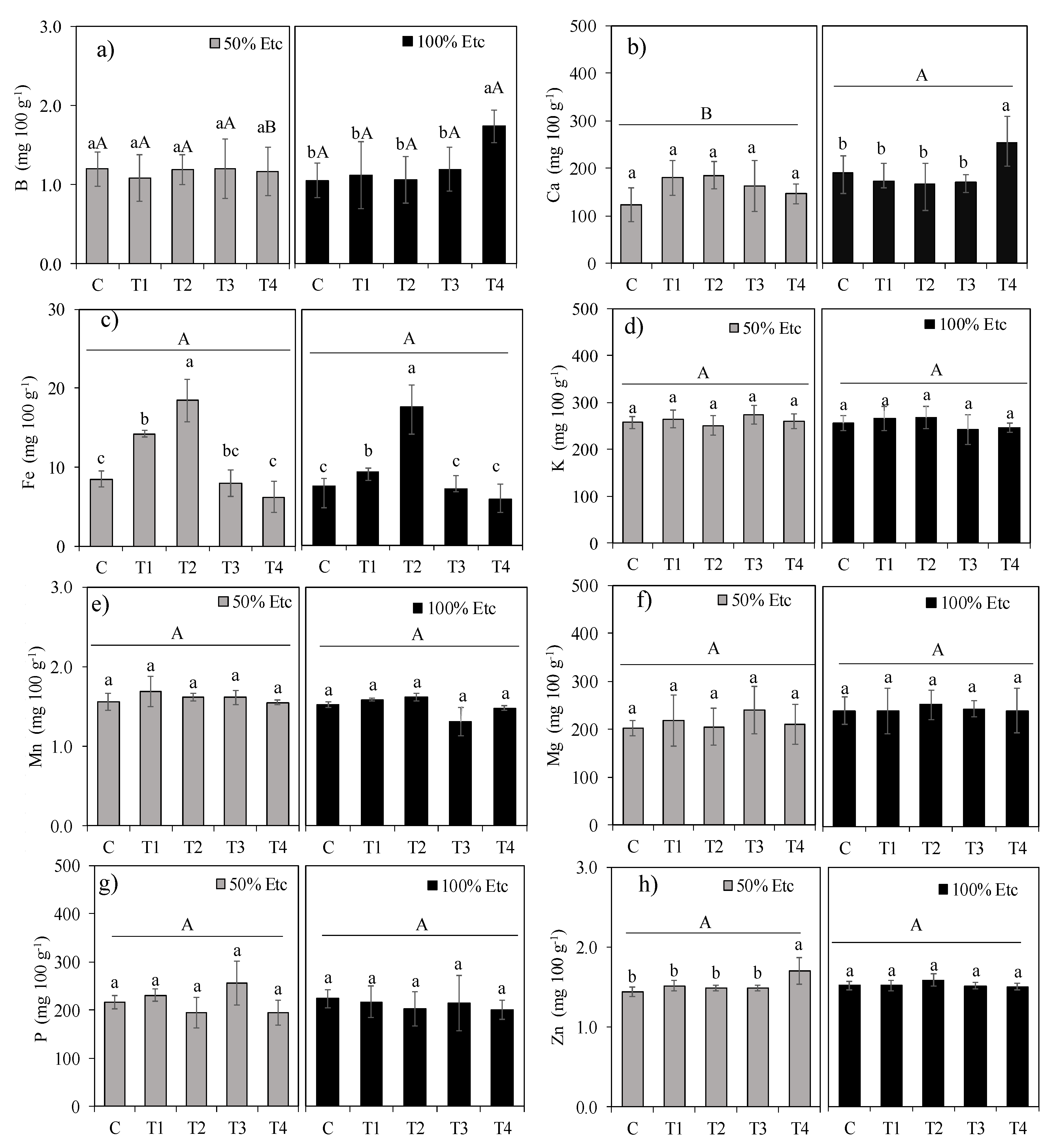

3.6. Mineral Element Content in Fruits

4. Discussion

4.1. Plant Growth

4.2. Gas Exchange, Photosynthetic Pigments, and Electrolyte Leakage

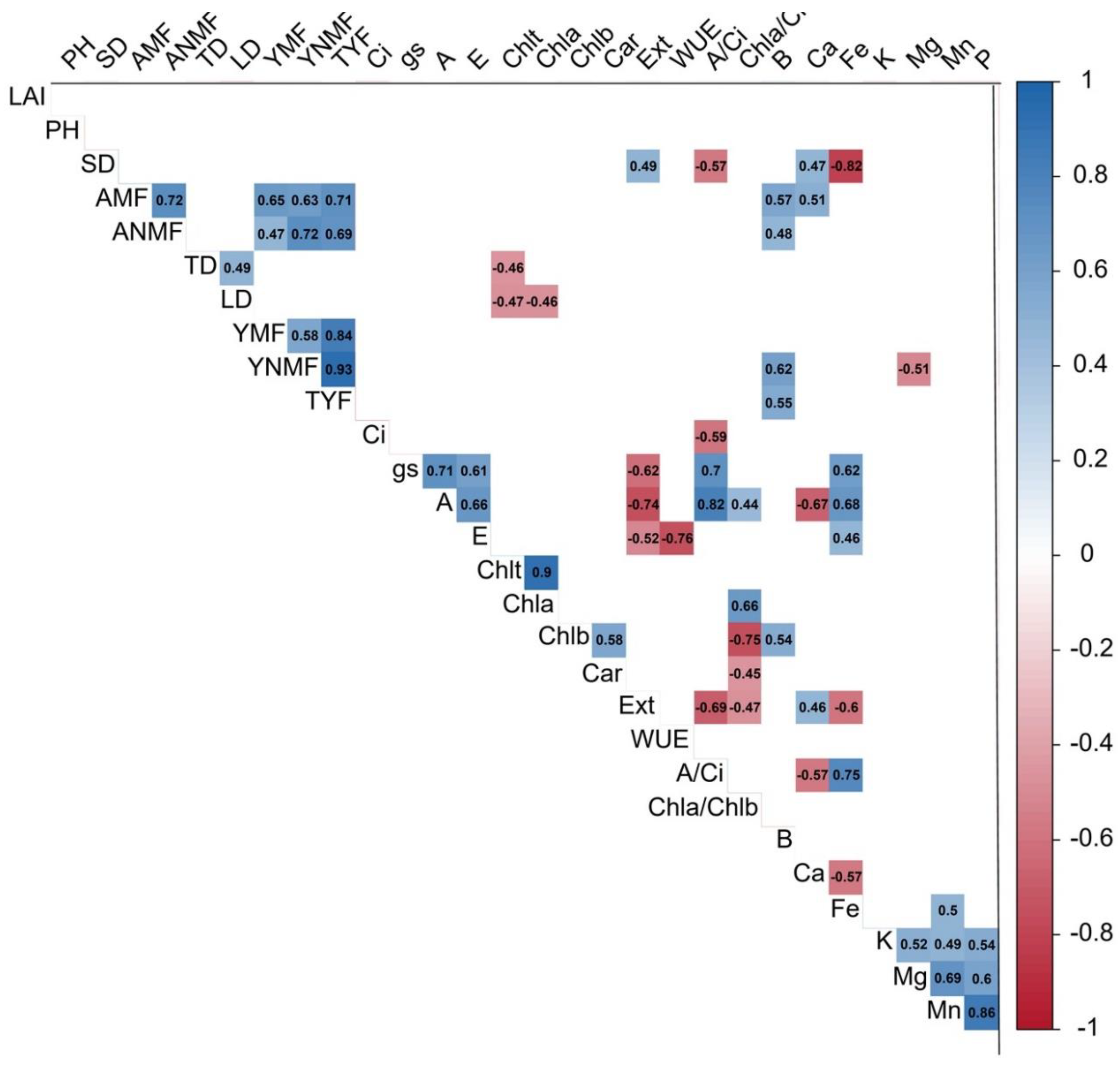

4.3. Yield, Fruit Nutrient Content, and Variable Correlations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- United Nations Water (UN-Water). The United Nations World Water Development Report 2021: Valuing Water; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Agência Nacional de Á guas e Saneamento Básico (ANA). Conjuntura dos recursos hídricos no Brasil 2023: Relatório pleno; ANA: Brasília, Brazil, 2023. Available online: https://www.snirh.gov.br/portal/snirh/centraisde-conteudos/conjuntura-dos-recursos-hidricos/conjuntura_2023.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Locatelli, S.; Barrera, W.; Verdi, L.; Nicoletto, C.; Marta, A.D.; Mauricieri, C. Modelling the response of tomato on deficit irrigation under greenhouse conditions. Scientia Horticulturae 2024, 326, 112770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadood, A.; Hameed, A.; Akram, S.; Ghaffar, M. Unraveling the impact of water deficit stress on nutritional quality and defense response of tomato genotypes. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1403895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caseiro, A.; Ascenso, A.; Costa, A.; Creagh-Flynn, J.; Johnson, M.; Simões, S. Lycopene in human health. LWT - Food Sci Technol 2020, 127, 109323. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, X.; Zhunag, W.; Xia, L.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.; Rao, Z.; Du, L.; Zhao, R.; Yi, M.; et al. Tomato and lycopene and multiple health outcomes: Umbrella review. Critical Reviews Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 2063–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMBRAPA. Embrapa Hortaliças. Tomate: Produção e Mercado no Brasil; Documentos 245; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, E.C.; Carvalho, J.A.; Rezende, F.C.; Freitas, W.A.; Ramos, M.M. Stomatal regulation and photosynthetic performance in tomato under water deficit. Environ. Exp. Botany 2021, 187, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, W.; Kang, Y.; Shi, M.; Yang, X.; Li, H.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Qin, S. Application of different foliar iron fertilizers for improving the photosynthesis and tuber quality of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and enhancing iron biofortification. Chem. Biological Tech. Agriculture 2022, 9, 79. [CrossRef]

- Haghpanah, M.; Hashemipetroudi, S.; Arzani, A.; Araniti, F. Drought tolerance in plants: Physiological and molecular responses. Plants 2024, 13, 2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zafar, S.; Javaid, A.; Perveen, S.; Hasnain, Z.; Ihtisham, M.; Abbas, A.; Usman, M.; El-Sappah, A.H.; Abbas, M.; et al. Zinc nanoparticles (ZnNPs): High-fidelity amelioration in turnip (Brassica rapa L.) production under drought stress. Sustainability. 2023; 15, 6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, B.L.R.; Ferreira, K.N.; Rocha, J.L.A.; Araujo, R.H.C.R.; Lopes, G.; Santos, L.C.d.; Bezerra Neto, F.; Sá, F.V.d.S.; Silva, T.I.d.; da Silva, W.I.; et al. Nano ZnO and Bioinoculants Mitigate Effects of Deficit Irrigation on Nutritional Quality of Green Peppers. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Uresti-Porras, J.G.; Cabrera-De La Fuente, M.; Benavidez-Mendoza, A.; Olivares-Sáenz, E.; Cabrera, R.I.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Effect of graft and nano ZnO on nutraceutical and mineral content in bell pepper. Plants 2021, 10, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semida, W.M.; Abdelkhalik, A.; Mohamed, G.F.; Abd El-Mageed, T.A.; Abd El-Mageed, S.A.; Rady, M.M.; Ali, E.F. Foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles promotes drought stress tolerance in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.)Plants. 2021; 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.; Bhatti, H.N.; Khan, A.K.; Zafar, L.; Iqbal, M. Zinc oxide nano-fertilizer application (foliar and soil) effect on the growth, photosynthetic pigments and antioxidant system of maize cultivar. Biocat. Agric. Biotechnology 2022, 42, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Ali, N.; Akmal, M.; Alotaibi, M.; Refay, Y.; Dindaroglu, T.; Abdul-Wajid, H.H.; Battaglia, M.L. Drought stress impacts on plants and different approaches to alleviate its adverse effects. Plants 2021, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.; Javad, S.; Jabeen, K.; Shah, A.A.; Ahmad, A.; Shah, A.N.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Mosa, W.F.A.; Abbas, A. Effect of calcium oxide, zinc oxide nanoparticles and their combined treatments on growth and yield attributes of Solanum lycopersicum L. J. King Saud Univ- Sci. 2023; 35, 102647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, Z. Nano-enabled agriculture: How do nanoparticles cross barriers in plants? Plant Communications 2022, 3, 100346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokoupil, L.; Mlcek, J. Foliar application of ZnO-NPS influences chlorophyll fluorescence and antioxidants pool in Capsicum annum L. under salinity. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, J.I.; Niño-Medina, G.; Olivares-Sáenz, E.; Lira-Saldivar, R.H.; Barriga-Castro, E.D.; Vázquez-Alvarado, R.; Rodríguez-Salinas, P.A.; Zavala-García, F. Foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles and zinc sulfate boosts the content of bioactive compounds in habanero peppers. Plants 2019, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baybordi, A. Zinc in Soils and Crop Nutrition; Parivar Press: Tehran, Iran, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elsheery, N.I.; Helaly, M.N.; El-Hoseiny, H.M.; Alam-Eldein, S.M. Zinc oxide and silicone nanoparticles to improve the resistance mechanism and annual productivity of salt-stressed mango trees. Agronomy 2020, 10, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybaez, Q.E.; Sanchez, P.B.; Badayos, R.B. Synthesis and characterization of nano zinc oxide foliar fertilizer and its influence on yield and postharvest quality of tomato. Philippine Agricultural Scientist 2020, 103, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, R.; Sarkar, A.; Dasgupta, D.; Acharya, K.; Keswani, C.; Popova, V.; Minkina, T.; Maksimov, A.Y.; Chakraborty, N. Unravelling the efficient applications of zinc and selenium for mitigation of abiotic stresses in plants. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Zhang, B.; Chachar, Z.; Li, J.; Xiao, G.; Wang, Q.; Hayat, F.; Deng, L.; Narejo, M.; Bozdar, B.; et al. Micronutrients and their effects on horticultural crop quality, productivity and sustainability. Scientia Horticulturae 2024, 323, 112512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, R.; Kato, K.; Hamaguchi, U.; Ueno, Y.; Tsuboshita, N.; Shimizu, S.; Furutani, S.; Ehira, S.; Nakajima, Y.; Kawakami, K.; et al. Structure of a monomeric photosystem I core associated with iron-stress-induced-A proteins from Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, J.; Wang, G.Y.; Ahmad, S.; Muhammad, I.; Zeeshan, M.; Gitari, H.; Adnan, M.; Fahad, S.; Khalid, M.H.B.; Zhou, X.B.; et al. Nitrogen fertilization coupled with iron foliar application improves the photosynthetic characteristics, photosynthetic nitrogen use efficiency, and the related enzymes of maize crops under different planting patterns. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 988055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedifar, M.; Moosavi, A.A.; Gavili, E.; Ershadi, A. Tomato fruit quality and nutrient dynamics under water deficit conditions: The influence of an organic fertilizer. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0310916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMBRAPA. Manual of Soil Analysis Methods, 2nd ed.; Centro Nacional de Pesquisa em Solo: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- AGRITEMPO. Agrometeorological monitoring system: meteorological stations for the state of Paraiba. 2023. Disponível em: https://www.agritempo.gov.br/agritempo/jsp/Estacao/index.jsp?siglaUF=PB. Acessado em 15 outubro 2023.

- Cavalcante, F.J.A. Fertilization Recommendations for the State of Pernambuco (Brazil), 2nd ed.; Instituto Agronômico de Pernambuco: Recife, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, J.E. Irrigation by Sprinkling; University of California Agricultural Experiment Station: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.E. Water consumption by agriculture plants. In Water Deficit and Plant Growth; Kozlowski, T.T., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA,; 1968; Volume 2, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration—Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements; FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, A.; Hatami, M. Foliar-applied nanoscale zero-valent iron (nZVI) and iron oxide (Fe3O4) induce differential responses in growth, physiology, antioxidative defense and biochemical indices in Leonurus cardiaca L. Environmental Research 2022, 215, 114254. Environmental Research 2022, 215, 114254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods in Enzymology 1987, 148, 350–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, P.; Thi, A. Effects of an abscisic acid pretreatment on membrane leakage and lipid composition of Vigna unguiculata leaf discs subjected to osmotic stress. Plant Science 1997, 130, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juzon-Sikora, K.; Lasko´s, K.; Warchoł, M.; Czyczyło-Mysza, I.M.; Dziurka, K.; Grzesiak, M.; Skrzypek,E. Water Relations and Physiological Traits Associated with the Yield Components of Winter Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Agriculture 2024, 14, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayet, J.P.; Bleinroth, E.W.; Matallo, M.; Garcia, E.E.C.; Garcia, A.E.; Ardito, E.F.G.; Bordin, M.R. Tomate para Exportação: Procedimentos de Colheita e Pós-colheita; Série Publicações Técnicas FRUPEX 13; EMBRAPA-SPI: Brasília, Brazil, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco, M.J.; Gianello, C.; Bissani, C.A.; Bohnen, H.; Volkweiss, S.J. Analysis of Soil, Plants and Other Materials, 2nd ed.; Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Viena: Austria, 2023.

- Qiao, M.; Hong, C.; Jiao, Y.; Hou, S.; Gao, H. Impacts of drought on photosynthesis in major food crops and the related mechanisms of plant responses to drought. Plants 2024, 13, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmenero-Flores, J.M.; Arbona, V.; Morillon, R.; Gómez-Cadenas, A. Salinity and water deficit. In The Genus Citrus; Talon, M., Caruso, M., Gmitter, F.G., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundel, D.; Lori, M.; Fliessbach, A.; van Kleunen, M.; Meyer, S.; Mader, P. Drought effects on nitrogen provisioning in different agricultural systems: Insights gained from a field experiment. Nitrogen 2021, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiz, L.; Zeiger, E.; Moller, I.M.; Murphy, A. Plant Physiology and Development, 6th ed.; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak, I.; Marschner, H. Increase in membrane permeability and exudation in roots of zinc deficient plants. J. Plant Physiology 1988, 132, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.U.; Aamer, M.; Chattha, M.U.; Haiying, T.; Shahzad, B.; Barbanti, L.; Nawaz, M.; Rasheed, A.; Afzal, A.; Liu, Y.; et al. The critical role of zinc in plants facing the drought stress. Agriculture 2020, 10, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewangizaw, B.; Kassie, K.; Assefa, S.; Lemma, G.; Gete, Y.; Getu, D.; Getanh, L.; Shegaw, G.; Manaze, G. Tomato yield, and water use efficiency as affected by nitrogen rate and irrigation regime in the central low lands of Ethiopia. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 13307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Salazar, J.C.; Guaca-Cruz, L.; Quiceno-Mayo, E.J.; Ortiz-Morea, F.A. Photosynthetic responses and protective mechanisms under prolonged drought stress in cocoa. Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira 2024, 59, e03543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Nan, R.; Mi, T.; Song, Y.; Shi, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, F.; Xi, Y.; Zhang, C. Rapid and nondestructive evaluation of wheat chlorophyll under drought stress using hyperspectral imaging. Inter. J. Molec. Sciences 2023, 24, 5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Lu, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Qin, D.; Huo, J. Effects of drought stress on photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence in blue honeysuckle. Plants 2024, 13, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Dash, P.K.; Das, D.; Das, S. Growth, yield and water productivity of tomato as influenced by deficit irrigation water management. Environmental Processes 2023, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowiak, A.; Podgórska, A.; Szal, B. Calcium in plants: An important element of cell physiology and structure, signaling, and stress responses. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 2024, 46, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Maldonado, P.; Aquea, F.; Reyes-Díaz, M.; Cárcamo-Fincheira, P.; Soto-Cerda, B.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Inostroza-Blancheteau, C. Role of boron and its interaction with other elements in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1332459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peroni, E.C.; Messoas, R.S.; Gallo, V.; Bardwosko, J.M.; Souza, E.R.; Avola, L.D.; Bamberg, A.L.; Rambo, C.V. Mineral content and antioxidant compounds in strawberry fruit submitted to drought stress. Food Science and Technology 2019, 39, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Mfarrej, M.F.B.; Usman, M.; Anayatullah, S.; Rizwan, M.; Alharby, H.F.; Zeid, I.M.A.; Alabdallah, N.M.; Ali, S. Effect of iron nanoparticles and conventional sources of Fe on growth, physiology and nutrient accumulation in wheat plants grown on normal and salt-affected soils. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 458, 131861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhao, S.; Huang, R.; Geng, Y.; Guo, L. The effects of exogenous iron on the photosynthetic performance and transcriptome of rice under salt-alkali stress. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maret, W.; Sandstead, H.H. Zinc requirements and the risks and benefits of zinc supplementation. J. Trace Elements in Med Biology 2006, 20, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, S.S.; Chen, Y.H. Association of zinc with anemia. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cançado, R.D. Iron deficiency anemia in women: Pathophysiological, diagnosis, and practical management. Rev Associação Méd. Brasileira 2023, 69 (Suppl. 1). [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Liu, J.; Jiang, G. Nanoparticle-specific transformations dictate nanoparticle effects associated with plants and implications for nanotechnology use in agriculture. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M. Nanoparticle-facilitated targeted nutrient delivery in plants: Breakthroughs and mechanistic insights. Plant Nano Biology 2025, 12, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alordzinu, K.E.; Appiah, S.A.; AL Aasmi, A.; Darko, R.O.; Li, J.; Lan, Y.; Adjibolosoo, D.; Lian, C.; Wang, H.; Qiao, S. Evaluating the influence of deficit irrigation on fruit yield and quality indices of tomatoes grown in sandy loam and silty loam soils. Water 2022, 14, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.L.J.; Valladares, G.S.; Vieira, J.S.; Coelho, R.M. Availability and spatial variability of copper, iron, manganese and zinc in soils of the State of Ceará, Brazil. Revista Ciência Agronômica 2018, 49, 371-380.

- Nascimento Júnior, A.L.; Souza, S.; Paiva, A.Q.; Souza, LD.; Souza-Filho, L.F.; Fernandes Filho, E.I.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R.; Santos, J.A.G.; Bomfim, M.R.; Silva, E.F.; Fernandes, A.C.O.; Xavier, F.A.S.bConcentration and variability of soil trace elements in an agricultural area in a semiarid region of the Irecê Plateau, Bahia, Brazil. Geoderma Regional, 2021, 24, e00351. [CrossRef]

| Chemical | Value | Physical | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH (CaCl2) | 6.45 | Sand (g kg-1) | 389 |

| OM (g kg-1) | 11.2 | Silt (g kg-1) | 430 |

| P (mg dm-3) | 180.1 | Clay (g kg-1) | 181 |

| K+ (mg dm-3) | 256.8 | BD (g cm-3) | 1.30 |

| Ca++ (cmolc dm-3) | 7.72 | PD (g cm-3) | 2.59 |

| Mg++ (cmolc dm-3) | 2.83 | TP (m3 m-3) | 0.47 |

| Na+ (cmolc dm-3) | 0.06 | FC (%) | 12.87 |

| H + Al+++ (cmolc dm-3) | 1.35 | PWP (%) | 5.29 |

| Fe (mg dm-3) | 18.0 | AWC (%) | 7.58 |

| Zn (mg dm-3) | 1.69 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).