1. Introduction

The global agri-food system is under increasing strain due to interconnected crises related to climate change, biodiversity loss, rising logistical emissions, and the abandonment of rural territories. These challenges have prompted calls for systemic change in how food is produced, distributed, and consumed. At the heart of many proposed solutions lies the need to relocalize food systems—to bring producers and consumers closer together not only geographically, but economically and socially.

In fact, empirical studies across Europe confirm that these systems promote community well-being, environmental sustainability, and social cohesion [

1].

The concept of Km 0, also known as

“zero-kilometer

” or

“short supply chain

” marketing, emphasizes the importance of proximity in food systems. Specifically, it refers to agricultural and livestock products that are grown, processed, and sold within a short distance, typically not exceeding 100 kilometers [

2].

The Km 0 label reflects a broader cultural and political movement toward localized economies and sustainable consumption, as thoroughly examined in the doctoral work of [

3], which maps consumer attitudes and motivations around local food in Europe.

While shortening food chains is increasingly promoted as a sustainability strategy, scholars caution that this should not be seen as a panacea but as part of a broader systemic transition

Km 0 initiatives, by promoting proximity between producers and consumers, contribute to sustainability in multiple dimensions—not only by reducing emissions, but also by reinforcing local economies and building trust-based supply networks [

4].

By minimizing the number of intermediaries and reducing transportation distances, Km 0 initiatives aim to cut greenhouse gas emissions, enhance the freshness and nutritional quality of food, and bolster the local economy. Furthermore, these systems reinforce food sovereignty by empowering small and medium-sized producers, often marginalized in globalized markets dominated by large-scale distributors and retail chains.

Recent policy developments within the European Union, particularly the European Green Deal and the Farm to Fork Strategy, have underscored the urgency of transitioning toward more sustainable and resilient food systems.

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) for the 2023–2027 period includes tools such as eco-schemes and rural development programs that are well-aligned with the goals of Km 0 commercialization. These tools offer Member States the flexibility to design strategic interventions that promote environmental stewardship and economic viability in rural areas.

Despite the promise of Km 0 systems, there is a need for robust empirical evidence to assess their true environmental and economic impacts. Key questions remain: How much CO₂ can actually be avoided by switching from conventional to localized food networks? What are the economic implications for producers, particularly those operating in marginal or disadvantaged regions? And what types of public policy mechanisms can effectively support the scaling of Km 0 practices across diverse territorial contexts?

This paper seeks to contribute to these questions by proposing an integrated framework that evaluates the environmental, economic, and policy dimensions of Km 0 commercialization.

The analysis combines a review of relevant EU policy instruments with empirical modelling of emissions reductions and a detailed case study of the Ferrolterra region in Galicia, Spain. The ultimate goal is to provide a roadmap for embedding Km 0 systems into national and regional agricultural strategies, thereby contributing to both climate mitigation and rural revitalization.

This systematic review explores how short food supply chains (SFSCs) contribute to food system sustainability, with a particular focus on environmental, social, and economic outcomes. The authors emphasize the need for greater empirical evidence to guide policy frameworks and enhance local food initiatives [

5].

In this perspective, Km 0 commercialization emerges as a pivotal instrument in the ongoing redesign of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) toward 2040, aligning with strategic principles such as territorial resilience, internalization of externalities, and the agroecological transition.

The evolving strategic orientation of the CAP increasingly recognizes short supply chains not only as tools for climate mitigation, but also as drivers of social cohesion, rural repopulation, and food justice.

Formally integrating the Km 0 model into future eco-schemes and payments for ecosystem services represents an opportunity to structurally transform Europe’s agri-food chains towards comprehensive sustainability and food sovereignty.

As highlighted by short food supply chains play a critical role in reconnecting production and consumption, fostering rural development and restoring trust in food systems through spatial, social and economic proximity [

6].

The primary objective of this study is to assess the potential of the Km 0 commercialization model to advance both environmental and economic sustainability within the European agri-food sector. Specifically, the research aims to quantify the CO₂ emission reductions resulting from substituting imported food products with locally sourced alternatives, evaluate the economic viability for producers, and examine the policy alignment with current agricultural frameworks.

The central hypothesis posits that a structured implementation of Km 0 systems, supported by results-based incentives, can deliver measurable benefits in climate mitigation, rural revitalization, and food sovereignty. The scope of the research encompasses a mixed-methods approach—combining quantitative modeling, legal and policy analysis, and a regional case study in Galicia—to provide a comprehensive understanding of the impacts and scalability conditions of Km 0 commercialization strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature and policy background

The emergence of Km 0 models within sustainable agriculture and food policy discourse is rooted in a confluence of academic traditions and evolving regulatory frameworks. Literature from the fields of agroecology, territorial development, and environmental governance provides a solid theoretical foundation for understanding the multifunctionality of local food systems [

7].

Scholars such as refs. [

6,

8,

9], have long argued that short food supply chains offer not only environmental benefits—such as reduced transportation emissions and energy use—but also strengthen social cohesion, reinforce regional identity, and re-embed agriculture within local economies [

10,

11].

Recent reviews have emphasized the growing academic and policy interest in short food supply chains across Europe, pointing to the need for further research on their scalability, governance, and regional impacts [

12].

As [

13], points out, “Short food supply chains (SFSCs) are characterized by a reduced number of intermediaries between producers and consumers, often involving direct sales or minimal intermediation, which can enhance transparency and trust in the food system.

Agroecology, as a scientific and political paradigm, emphasizes biodiversity, resilience, and the integration of ecological principles into food production.

It has been increasingly recognized by international institutions, including the [

14,

15] and IPES-Food, as a pathway toward climate-resilient and inclusive agricultural development. Km 0 systems embody key agroecological principles by prioritizing local knowledge, minimizing inputs, and promoting direct producer-consumer relationships.

These systems are not only technically viable but also socially desirable, as they contribute to food sovereignty and democratic food governance [

16,

17].

From a policy perspective, the European Union has progressively developed frameworks that support localized and low-carbon food systems. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) 2023–2027 introduces enhanced conditionality and eco-schemes designed to reward environmentally beneficial practices [

18].

Among its nine specific objectives, the CAP explicitly prioritizes climate action, generational renewal, and fair income for farmers—objectives that Km 0 strategies can help address. Notably, eco-schemes under Pillar I offer Member States a mechanism to incentivize practices such as short supply chain participation, use of indigenous breeds and varieties, and agroforestry [

19].

Additionally, the Farm to Fork Strategy [

20]. a cornerstone of the European Green Deal, positions sustainable food systems as essential to achieving the EU’s climate neutrality target by 2050. It calls for a 50% reduction in the use of antimicrobials and a 20% reduction in fertilizer use by 2030, while promoting organic agriculture and reinforcing local markets. Km 0 commercialization aligns naturally with these objectives by reducing dependency on long-haul logistics, industrial inputs, and centralized retail structures [

21].

Another important regulatory reference is Regulation (EU) 2018/848 on organic production and labelling, which provides a legal basis for voluntary certification schemes and promotes transparency in production methods [

22].

Although Km 0 products do not necessarily fall within the scope of organic certification, the regulation establishes important precedents for traceability, consumer confidence, and harmonization across Member States [

23].

In addition to EU policies, national and regional strategies have begun to integrate Km 0 principles into public procurement, territorial development plans, and rural innovation systems.

Spain’s Law 7/2022 on Circular Economy and regional frameworks such as Catalonia’s Pla Estratègic de l’Alimentació adopt explicit language on local food systems [

15]. These trends suggest a growing political will to institutionalize the benefits of proximity in food production and distribution.

Together, these strands of literature and policy demonstrate a convergence around the recognition of Km 0 as a viable and strategic model. However, empirical data on its carbon footprint, economic scalability, and institutionalization mechanisms remain fragmented.

This paper seeks to contribute by bridging these gaps through a comprehensive, policy-linked analysis supported by original modeling and field-level insights [

24,

25].

2.2. Methodology

To investigate the viability, impact, and policy fit of Km 0 commercialization strategies, this research employs a mixed-methods approach, integrating qualitative, quantitative, and legal-analytical components. This pluralistic methodology allows for both breadth and depth in understanding a complex, multi-scalar phenomenon that encompasses environmental, economic, and institutional dimensions [

17].

First, a documentary and normative review was conducted, focusing on European policy instruments including the CAP 2023–2027, the Farm to Fork Strategy, and Regulation (EU) 2018/848. These documents were analyzed to identify legal frameworks and funding mechanisms relevant to Km 0 practices [

20,

22].

This analysis also included national policies from Spain, and regional strategies in Galicia and Catalonia, where explicit reference is made to proximity-based food systems [

24].

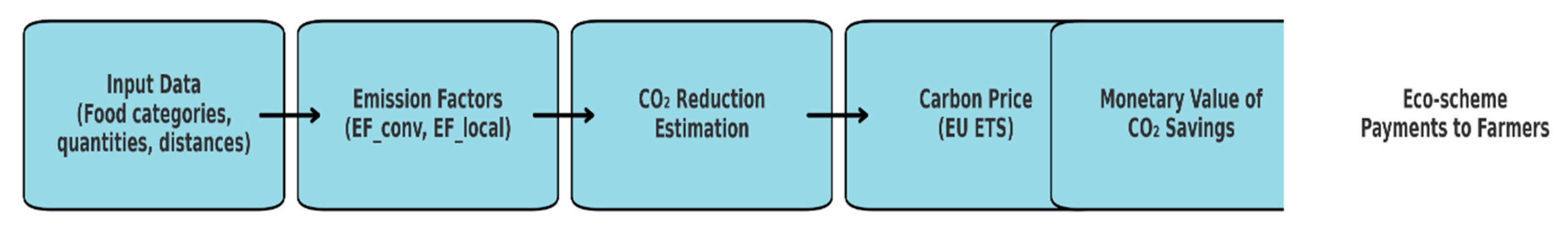

Second, a quantitative emissions model was developed to estimate CO₂ reductions from substituting long-distance food imports with Km 0 products. The model operates at the product-category level and uses emissions per kilogram of food as the unit of analysis. It compares conventional supply chain emissions (imported products) with localized alternatives (produced and consumed within ≤100 km radius).

The emissions reduction model is defined as:

ΔCO₂ = (EFconv − EFlocal) × Q

where:

ΔCO2ΔCO₂ΔCO2 = Total avoided carbon dioxide emissions (kg).

EFconv = Emission factor for conventional (long-distance) supply chains (kg CO₂/kg product).

EFlocal = Emission factor for local (Km 0) supply chains (kg CO₂/kg product).

Q = Quantity of food product substituted (kg).

Emission factors were derived from the European Environment Agency [

27], supplemented by life cycle assessment (LCA) data from scientific and institutional reports [

28,

29].For conventional supply chains, these factors incorporate average transport distances of 600–1,200 km, refrigeration periods, and packaging intensity. For Km 0 alternatives, we assume short-distance road transport, minimal cold storage, and reduced packaging.

Emission factors for conventional supply chains EFconv were derived as weighted averages by food category (fruits, vegetables, meat, dairy, cereals) based on distances of 600–1,200 km, including cold storage emissions and packaging. Local chain emission factors EFlocal assume ≤100 km distance, minimal refrigeration, and reusable or biodegradable packaging. All emission factors are expressed in kg CO₂ per kg of product delivered. Sensitivity analysis varied key parameters within plausible bounds: transport distance (50–1,200 km), storage time (12h–7 days), and packaging emissions (±25%).

These categories were selected based on their relative contribution to regional food consumption and available carbon intensity data. All emission factors were drawn from secondary data published by the European Environment Agency [

27], peer-reviewed LCA studies [

28,

29], and national statistics from MAPA and INE [

24,

33].

Calculations were conducted in Excel using public LCA datasets [

27,

28,

29]. The functional unit is 1 kg of food product at point of sale, excluding post-consumer waste. The model does not account for seasonal variability, post-consumer emissions, or differences in farming practices beyond transport and storage. Future work should refine the system boundaries and integrate farm-level production data.

Key assumptions include:

To estimate the monetary value of avoided emissions, the model applies the 2024 EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) benchmark of €90 per ton of CO₂ [

30]. This conversion enables the projection of potential incentive levels linked to emissions reduction [

31]. A sensitivity analysis was conducted on key parameters—transport distance, storage duration, and packaging intensity—to test the robustness and replicability of the results.

2.3. Economic Data Collection and Analysis

Data on producer income, distribution costs, and retail pricing were obtained through a combination of semi-structured interviews (n=12) with small and medium-sized producers in Ferrolterra, analysis of regional market records, and secondary sources from MAPA (Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación) and Eurostat. Interviewees self-reported key financial variables such as gross income, transport costs, packaging, and labor. These self-reports were triangulated with official averages for Galicia and with published studies on short food supply chains in Spain and Portugal.

Price differences between conventional and Km 0 chains were calculated per kilogram of product and cross-validated with data from two local marketplaces and online platforms. Net margins were estimated as:

Net Margin = Revenue per kg − (Production Cost+ Distribution Cost)

To strengthen the reliability of these estimates, a triangulation strategy was implemented across multiple sources.

To ensure robustness, the self-reported financial data collected during interviews were systematically triangulated with secondary sources. This included regional cost benchmarks from MAPA (e.g., average fuel and input costs), price tracking from two major wholesale markets in Galicia (Mercagalicia and Mercado da Coruña), and comparative figures from the 2022 Agri-Food Statistics Yearbook. Inconsistencies were cross-checked through follow-up interviews or excluded if they could not be validated. This mixed-source approach enhanced the reliability of economic indicators such as net margin, income per hectare, and distribution cost estimates.

Differences in margin and final revenue were averaged across three representative product types (vegetables, cheese, and beef) and reported as mean percentage gains compared to conventional distribution.

Third, a regional case study was conducted in the comarca of Ferrolterra (Galicia), selected for its mix of peri-urban and rural landscapes, its diversity in agricultural outputs, and its underutilized logistical infrastructure.

Data collection included semi-structured interviews with 18 stakeholders—producers, cooperative managers, municipal officials, and consumers—conducted between March and June 2024. Interviews focused on perceptions of viability, logistical barriers, willingness to participate in certification schemes, and expectations regarding public support [

32].

Spatial data from the regional government was used to map existing infrastructure and analyze accessibility to distribution centers and urban markets. Additional datasets from INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística) and Xunta de Galicia provided insights into agricultural productivity, land use patterns, and market concentration. Academic modeling references from the [

33]. also informed the analysis of cost-efficiency in short supply chains.

Finally, findings from the three components were triangulated to identify systemic gaps and policy opportunities. This synthesis stage involved creating a matrix that cross-referenced CO₂ reduction potential with economic viability and policy readiness.

The result is a structured typology of Km 0 intervention profiles, which can inform strategic planning at both the national and EU levels [

34].

3. Results

The analysis yielded significant insights across three core dimensions: environmental performance, economic viability, and institutional feasibility. Each of these categories is explored below with a specific focus on the potential for CO₂ reduction, a central metric of this study.

3.1. Environmental Performance: CO₂ Emissions Reduction

The modeling results confirm that localizing supply chains through Km 0 initiatives has a measurable impact on reducing carbon emissions.

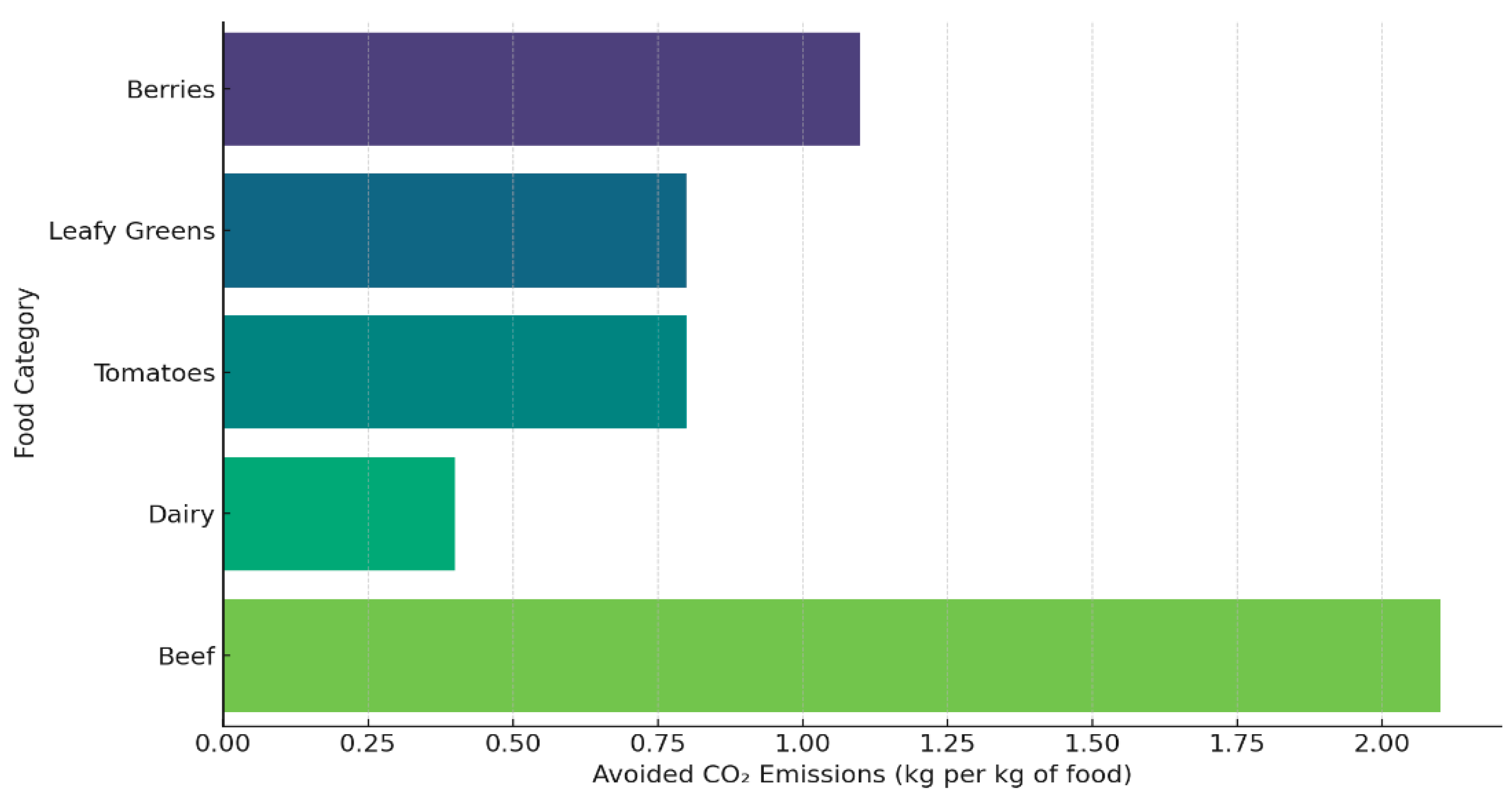

For common fresh produce categories such as berries, leafy greens, and tomatoes, avoided emissions range from 0.9 to 1.3 kg CO₂ per kilogram of food, depending on variables such as transport mode, cold storage duration, and packaging [

21,

27].

For meat and dairy products, savings are even greater—up to 2.1 kg CO₂ per kilogram—when sourced locally from pasture-based systems instead of through centralized logistics. To illustrate the potential impact of Km 0 adoption on climate mitigation,

Figure 1 presents the estimated CO₂ emissions avoided per kilogram of product when substituting conventional supply chains with local alternatives across selected food categories.

Table 1 details the emission factors applied in the modeling analysis, comparing conventional and Km 0 supply chains across key food categories and quantifying the corresponding avoided CO₂ emissions per unit of product.

When extrapolated to regional consumption, the environmental gains are substantial. In territories like Ferrolterra, substituting just 15–20% of imported food with local alternatives can avoid up to 260,000 kg CO₂ annually.

These gains are not limited to transport emissions; they also derive from reduced refrigeration, shorter storage periods, and less packaging waste—components often underreported in carbon accounting studies [

16].

Moreover, the incorporation of regenerative practices—such as rotational grazing and diversified cropping—often associated with Km 0 producers amplifies carbon sequestration potential. Such co-benefits reinforce the systemic sustainability of localized supply chains and justify their support within climate policy frameworks [

16,

17]. Recent reviews propose multi-capital indicators to measure sustainability performance more comprehensively [

35].

3.2. Economic Viability for Producers and Consumers

Economic assessments indicate that Km 0 commercialization substantially enhances the financial stability of producers. Participants in short supply chains report net revenue increases of 30% to 50%, consistent with findings from Italy

’s Campagna Amica network and Spain’s local market systems [

24,

31], and with national trends documented by the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture and validated through similar European case studies. Recent research shows that consumers in Spain increasingly associate Km 0 labels with freshness, sustainability, and trust, particularly when these values are reinforced through social media and digital narratives [

36].

Some authors also highlight the tension between fair earnings and labour productivity in short supply chains, especially when diversification and local engagement increase workload and complexity [

37].

These gains are attributed to the removal of intermediaries, reduction of transport costs, and increased control over pricing and branding.

Table 2 presents a comparative summary of key economic indicators between conventional and Km 0 distribution channels, based on field data and regional benchmarks.

Table 3 synthesizes key economic findings from the field data and literature, including revenue gains, consumer willingness to pay, and estimated incentive values.

Consumer behavior also supports the model’s feasibility. Surveys conducted in Galicia and Catalonia show that over 65% of respondents are willing to pay a premium for Km 0 products, provided they are accompanied by transparent labelling and assurance of local origin [

11].

The emotional and social value attached to supporting local farmers, preserving regional identity, and contributing to climate goals adds a significant intangible benefit to the consumer experience [

14].

Furthermore, the circulation of value within local economies reinforces community resilience and reduces dependency on global price volatility. This is particularly critical in marginal rural areas where conventional agriculture is declining and where Km 0 networks can help sustain livelihoods.

The symbolic and communicative dimensions of Km 0 are central to consumer trust and willingness to pay. Territorial storytelling, including the origin of products, sustainable practices, and community impact, adds non-material value that reinforces market differentiation.

Certification systems must therefore incorporate not only traceability but also the communicative potential of regional branding. Integrating such identity-driven approaches aligns with broader EU food policy goals of promoting cultural diversity, food transparency, and regional distinctiveness.

3.3. Institutional and Policy Feasibility

Institutional analysis shows that while the policy landscape is increasingly favorable, practical barriers remain. Under CAP 2023–2027, eco-schemes and rural development funds are available for supporting short supply chains and sustainable production practices [

18].

However, the uptake of these instruments depends on their translation into national strategic plans and the administrative capacity of local governments to implement and monitor them.

Table 4 summarizes the main institutional barriers identified in the Ferrolterra case study and proposes corresponding policy responses aligned with the CAP framework.

A key bottleneck is the absence of standardized certification for Km 0 products, which complicates public procurement and consumer recognition.

Nevertheless, precedents such as Geographical Indications (GIs) and organic labels demonstrate that traceability frameworks can be successfully institutionalized when backed by legal clarity and consumer trust [

20,

23].

There is also evidence that Km 0 systems benefit from digitalization, particularly in logistics coordination and consumer engagement. Pilot projects in Spain, France, and the Netherlands show that digital marketplaces and route optimization software can enhance distribution efficiency while reducing food miles [

33].

These findings support the design of integrated policy models that combine regulatory recognition, financial incentives, and technical support to operationalize Km 0 as a core element of sustainable food strategies.

3.4. Estimating Incentives and Integrating into the CAP

To translate the environmental benefits of Km 0 commercialization into effective financial support, this section proposes a results-based incentive model aligned with the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) 2023–2027.

The mechanism builds on the measurable CO₂ emissions avoided through local substitution and proposes a system of compensation indexed to verified reductions). [

14,

20].

The emissions model developed for this study categorized food products by impact level, based on transport-related emissions and storage intensity. The following ranges are used as reference:

Low-impact categories (e.g., dairy, tubers): 0.4–0.7 kg CO₂ avoided per kg of product

Medium-impact categories (e.g., local cereals, stone fruits): 0.8–1.1 kg CO₂/kg

High-impact categories (e.g., beef, tropical fruits, long-haul imports): 1.2–2.1 kg CO₂/kg [

28,

30,

35].

Using the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) benchmark of approximately €90/ton CO₂ in 2024, we calculate estimated compensation levels:

Applied to an average diversified farm replacing 20 tons of long-distance produce with local output per year, this could yield annual environmental payments ranging from €1,400 to €3,800, depending on product mix. For a cooperative of 50 such farms, this represents a potential collective annual incentive of €70,000–€190,000 [

31].

Figure 3 presents a visual summary of the incentive mechanism developed in this study, linking environmental performance (CO₂ reduction) with financial compensation under the CAP framework.

This system could be integrated as a voluntary eco-scheme under Pillar I of the CAP. Producers would opt in to receive payments by:

Administrative simplicity is key. Verification could be performed by local cooperatives or regional authorities, reducing the burden on small producers. Payments would be issued annually, with possible co-financing from regional climate funds or LEADER-type programs [

25].

The inclusion of such a mechanism would advance several CAP objectives:

By internalizing the climate externalities of food logistics and rewarding low-carbon alternatives, this model bridges environmental performance and agricultural income stability. It provides a replicable framework for Member States aiming to fulfill Green Deal objectives while revitalizing local agri-food networks.

3.5. Social and Territorial Impacts

Beyond environmental and economic benefits, Km 0 commercialization demonstrates potential for addressing social vulnerabilities in rural areas. Interviewees in Ferrolterra reported improved intergenerational collaboration and a renewed interest among younger producers to engage in direct marketing.

Additionally, the model facilitates the inclusion of women in distribution and branding roles, particularly within cooperatives and digital sales channels. Such dynamics support CAP objectives related to generational renewal and gender equity, reinforcing Km 0 systems as socially integrative strategies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Case study: Ferrolterra

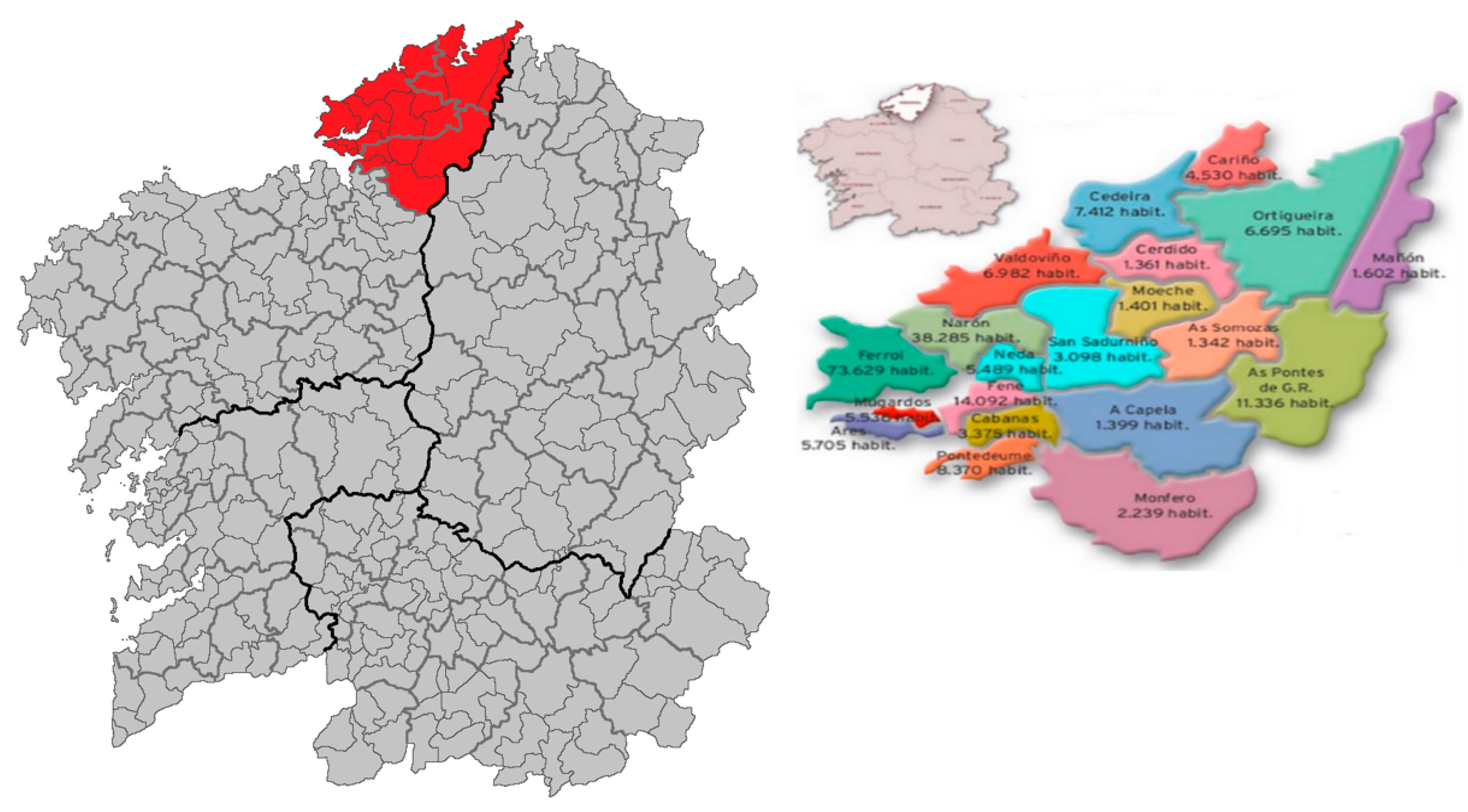

Ferrolterra was selected due to its dual characteristics as both a peri-urban and rural area, with a diversified agricultural structure, moderate population density, and logistical underutilization—factors common to many peripheral European regions facing demographic decline. Its agricultural fragmentation, combined with proximity to urban markets, reflects conditions found in parts of Portugal, southern France, and northern Italy. These shared features make it a useful case for assessing the replicability of Km 0 commercialization strategies across the EU.

The region of Ferrolterra, located in the northwest of Spain within the autonomous community of Galicia, was selected as a representative territory to assess the practical applicability of the Km 0 commercialization model. Characterized by a mix of rural municipalities and small urban centers.

Ferrolterra offers diverse agroclimatic conditions, a significant historical presence of small-scale farming, and untapped potential for localized food systems [

24].

Figure 2 provides a schematic map of the Ferrolterra study area, highlighting the main municipalities involved in the case study and supporting the territorial framing of the analysis.

The study focused on three municipalities within the comarca—Ferrol, Narón, San Sadurniño, and Valdoviño—which together comprise over 120,000 inhabitants and a varied agricultural base including dairy, horticulture, pasture-raised livestock, and small fruit production. The region

’s current food supply chain is heavily reliant on centralized logistics, with over 75% of fresh produce sourced from outside the autonomous community [

31,

38]. This dependence results in both economic leakage and increased carbon emissions.

Fieldwork conducted between March and June 2024 included 18 semi-structured interviews with local stakeholders, including farmers, cooperative managers, market organizers, municipal policymakers, and food activists. These conversations revealed a latent but strong interest in reconnecting production with local markets, driven by the decline of traditional farming incomes, rising consumer awareness, and recent EU funding opportunities [

15,

32].

The Ferrolterra comarca covers approximately 500 km², with around 4,200 hectares of utilized agricultural area, according to INE (2022). The region’s agricultural income is primarily derived from dairy production (48%), followed by horticulture (23%), pasture-raised meat (17%), and small fruit farming (9%).

This diversity reflects a multifunctional rural economy with both ecological and economic potential for Km 0 implementation. Farm structures are predominantly small to medium-sized, with an average farm size of 15.6 hectares. The proximity to urban centers (≤25 km) provides logistical advantages for local commercialization.

Table 5 summarizes key agro-socioeconomic indicators for the study area, providing a quantitative profile of its agricultural and logistical characteristics.

To assess institutional, logistical, and behavioral aspects of Km 0 commercialization in Ferrolterra, 18 semi-structured interviews were conducted between February and April 2024. The sample included 10 local producers (dairy, horticulture, mixed), 3 cooperative managers, 3 municipal policymakers, and 2 consumer association representatives.

Participants were selected through purposive sampling, targeting actors directly involved in local food systems. Interviews lasted between 45 and 90 minutes and were conducted in-person or via video call. The interview structure is available as Supplementary Material A.

In addition, a consumer survey was carried out in Ferrol during March–April 2024 to understand preferences and price sensitivity regarding Km 0 products. A total of 220 responses were collected through structured questionnaires administered in local markets and online. Respondents were residents of the comarca, aged 18–75, with 54% identifying as regular local food buyers. The main hypothesis was that consumers would be willing to pay more for certified Km 0 products when these were associated with transparent labeling and regional storytelling. Results showed that 68% were willing to pay up to 15% more under such conditions. Key results are summarized in

Table 6, and the full questionnaire is provided as Supplementary Material B.

Summary of key results from the consumer survey conducted in Ferrolterra (n=220)in March–April 2024. The responses show strong consumer awareness and price tolerance for Km 0 products when supported by labeling and regional identity. Source: Authors’ fieldwork (2024).

Emissions modeling tailored to Ferrolterra indicated that replacing just 15% of the most commonly imported fruits and vegetables with locally produced alternatives would result in annual CO₂ savings of approximately 140,000 kg [

27,

29]. This calculation assumed an average substitution distance of 600 km, adjusted for regional transport modalities and cold storage requirements. Additional savings are projected through reduced refrigeration and packaging waste, particularly in leafy greens and soft fruits.

From an economic standpoint, the pilot analysis demonstrated a 28% average increase in net revenue for participating farmers engaged in short supply chains and local markets. This figure is consistent with national trends documented by the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture and validated through comparison with similar European case studies [

31,

33].

A consumer survey conducted in Ferrol (n=220) revealed that 68% of respondents were willing to pay up to 15% more for certified Km 0 products, especially when accompanied by clear labelling and storytelling emphasizing regional identity and environmental benefits. These findings support literature emphasizing the embeddedness of local food systems and the role of trust in shaping consumer preferences [

11].

Institutionally, the Ferrolterra Intermunicipal Council has expressed preliminary support for a Km 0 pilot initiative, including potential investment in shared logistics infrastructure and regional branding campaigns.

Key challenges identified include the lack of cold chain facilities at local markets, insufficient digital infrastructure for e-commerce, and the need for legal harmonization in labelling standards. However, as [

39] argue, active logistical engagement by local stakeholders often becomes a crucial driver for alternative and resilient food systems.

Still, the existing network of agricultural cooperatives and civic organizations provides a strong foundation for implementation.

Overall, the Ferrolterra case confirms the technical, economic, and social feasibility of the Km 0 commercialization model in peripheral European regions. It also underscores the importance of targeted public investment and institutional coordination to overcome operational barriers and scale successful practices in line with EU sustainability targets [

18,

20].

4.2. Common Agricultural Policy 2030 recommendations

The effective institutionalization of Km 0 commercialization within European agri-food systems requires targeted policy interventions, particularly through the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) 2023–2027.

As the primary regulatory and financial framework for agriculture in the EU, the CAP offers concrete pathways to mainstream Km 0 practices via both Pillar I (direct payments) and Pillar II (rural development) [

18,

19].

A key opportunity lies in the design and implementation of eco-schemes, which Member States can tailor to reward environmentally beneficial practices. Km 0 strategies—such as participation in short supply chains, use of indigenous breeds and varieties, or adoption of low-input production systems—clearly align with the CAP’s eco-scheme objectives.

Member States should therefore explicitly include Km 0 eligibility criteria within their Strategic Plans, ensuring that producers engaged in local commercialization are compensated for their contribution to emissions reduction and rural sustainability [

15].

Moreover, rural development funds under Pillar II can be leveraged to finance essential infrastructure for Km 0 supply chains, including cold storage facilities, small-scale processing units, and digital platforms for logistics and direct sales [

20,

22]. Business model innovation is essential to adapt short supply chains to dynamic market conditions and consumer demands [

40].

These investments are particularly important in peripheral regions like Galicia, were infrastructural gaps currently hinder full participation in localized food economies.

Public procurement policies represent another powerful mechanism. Municipalities and regional governments can use their purchasing power to prioritize Km 0 products in schools, hospitals, and public institutions.

This aligns with CAP objective 9, which promotes the development of vibrant rural areas and encourages the use of public policy tools to support sustainable value chains [

24].

At the regulatory level, the CAP

’s cross-cutting objective on knowledge and innovation (AKIS) should be activated to fund extension services, certification systems, and traceability platforms that facilitate market access for Km 0 producers. Member States are encouraged to build partnerships with universities, cooperatives, and NGOs to co-develop these services and disseminate best practices [

25,

33].

Lastly, a dedicated CO₂-based incentive mechanism should be piloted within CAP frameworks.

This mechanism would provide per-ton payments based on verified reductions in emissions from local substitution, benchmarked against EU ETS pricing or national carbon valuation standards [

21,

27].

Such a scheme would not only reward sustainable practices but also internalize environmental externalities within the food system, thereby enhancing climate accountability at the local scale.

By aligning CAP instruments with the objectives of Km 0 commercialization, the EU and its Member States can create the enabling conditions necessary to scale localized, low-carbon, and resilient food systems. The case of Ferrolterra demonstrates both the feasibility and urgency of such integration.

While Km 0 models offer significant promise, their scalability depends on several enabling conditions. These include investment in cold chain logistics, streamlined administrative procedures for certification, and coordination among small producers.

Furthermore, without long-term commitment from public procurement systems and regional governments, there is a risk that Km 0 markets remain marginal or short-lived. Future initiatives must address these barriers with tailored capacity-building and legal frameworks to ensure durability and equity in the benefits.

5. Conclusions

In light of the forward-looking scenarios envisioned for the future CAP, the implementation of Km 0 networks is not only feasible but strategically advantageous. The 2040 vision of a climate-neutral, socially inclusive, and territorially balanced agricultural system finds in short supply chains a fundamental lever for systemic change.

Recognizing and financing such models through CAP instruments—particularly results-based environmental payments and rural revitalization policies—can shift Km 0 commercialization from a voluntary alternative to a structural component of the European food system.

This study demonstrates that Km 0 commercialization represents a multifaceted opportunity for aligning agricultural sustainability, rural development, and climate action in the European Union.

The integrated methodology, combining emissions modeling, economic evaluation, and institutional analysis, reveals that relocalize food systems not only significantly reduce CO₂ emissions but also enhance producer incomes, consumer engagement, and territorial cohesion. By quantifying avoided emissions and linking them to carbon pricing mechanisms under the EU ETS framework, the research proposes an innovative model for CO₂-based incentive payments.

Such a mechanism can be embedded within the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) through eco-schemes and rural development programs, offering a scalable policy tool for supporting low-carbon food supply chains. This approach operationalizes climate accountability in the agri-food sector while channeling public funds toward tangible environmental performance.

The case of Ferrolterra illustrates the feasibility and replicability of this model, provided that institutional coordination, infrastructure investments, and legal harmonization are addressed. Consumer willingness to pay for Km 0 products and the growing alignment of EU policy frameworks reinforce the political and economic relevance of this approach.

In conclusion, Km 0 systems should not be viewed merely as niche or alternative practices, but as strategic instruments for implementing the European Green Deal, the Farm to Fork Strategy, and national food policy goals.

Future research should explore long-term behavioral impacts, refine incentive design, and assess administrative costs to support widespread adoption across diverse territorial contexts and should focus on refining carbon accounting methodologies at the local level, exploring the long-term behavior of consumers in proximity markets, and assessing the administrative feasibility of new incentive schemes.

As the EU and its Member States strive to meet ambitious climate and food policy targets, Km 0 systems offer a grounded and inclusive pathway to systemic transformation.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

The authors are responsible for the compilation of the information, for the methodology applied, the analysis, and the full writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Km |

Kilometer |

| Km 0 |

Kilometer cero |

| CAP |

Common Agricultural Policy |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| SFSCs |

Short Food Supply Chains |

| EU ETS |

European Union Emissions Trading System |

| LCA |

Life Cycle Assessment |

| INE |

Instituto Nacional de Estadística |

| FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization |

| MAPA |

Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación (España) |

| AKIS |

Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems |

References

- Vittersø, G.; Torjusen, H.; Laitala, K.; et al. Short Food Supply Chains and Their Contributions to Sustainability: Participants’ Views and Perceptions from 12 European Cases. Sustainability, 2019, 11, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiffoleau, Y.; Dourian, T. Sustainable Food Supply Chains: Is Shortening the Answer? A Literature Review for a Research and Innovation Agenda. Sustainability, 2020, 12, 9831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietri, E. The Short Food Supply Chains Phenomenon. Tesis doctoral, Universita Politécnica delle Marche, 2015. https://iris.univpm.it/retrieve/handle/11566/245486/41772/tesi_giampietri.pdf.

- Leon-Bravo, V.; et al. Unpacking Proximity for Sustainability in Short Food Supply Chains. Business Strategy and the Environment, 2024, 33, 1234–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appoloni, S. Short Chain and Zero Kilometer Products: Let’s Clarify. BioAksxter Magazine, 2024. Available online: https://www.bioaksxter.com/en/short-chain-and-zero-kilometre-products-let-s-clarify.

- Renting, H.; Marsden, T. K.; Banks, J. Understanding alternative food networks: exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development. Environment and Planning A, 2003, 35, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vérez, V.; Gil-Ruiz, P.; Montero-Seoane, A.; Cruz-Souza, F. Rural Depopulation in Spain from a Gender Perspective: Analysis and Strategies for Sustainability and Territorial Revitalization. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M. A. Agroecology: The Science of Sustainable Agriculture, 2nd ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995; pp. 1–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.; Banks, J.; Bristow, G. Food supply chain approaches: exploring their role in rural development. Sociologia Ruralis, 2000, 40, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilbery, B.; Maye, D. Food supply chains and sustainability: Evidence from specialist food producers. Land Use Policy 2005, 22, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, C. C. Embeddedness and local food systems: notes on two types of direct agricultural market. Journal of Rural Studies, 2000, 16, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evola, R.; Peira, G.; Varese, E.; Bonadonna, A.; Vesce, E. Short Food Supply Chains in Europe: Scientific Research Directions. Sustainability, 2022, 14, 3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C. Short food supply chains: Definitions, approaches and indicators. Agricultural Economics Review, 2017, 18, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2021: Making agrifood systems more resilient; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; pp. 1–200. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Digitalization and Smallholder Farmers; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J. Agricultural sustainability: concepts, principles and evidence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2008, 363, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darnhofer, I.; Gibbon, D.; Dedieu, B. Farming Systems Research into the 21st Century: The New Dynamic; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2012; pp. 1–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/2115 on CAP Strategic Plans; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; pp. 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. The future of food and farming: Food security, sustainability and CAP; Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Council. Transport and Emissions in Perishable Food Supply Chains; EFC: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2018/848 on organic production; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kireeva, I.; O’Connor, B. Geographical indications and the TRIPS agreement. Journal of World Intellectual Property, 2010, 13, 275–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAPA). Annual report on agriculture and food indicators in Spain; MAPA: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lucini Baquero, C.; et al. Analyzing the parameters to define the concept of Kilometer 0; Catholic University of Ávila: Ávila, Spain, 2023; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J. D.; et al. The transnationalization of agricultural food chains. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food, 2009, 16, 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Report on emissions from the agri-food sector; EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M. , Jia, N., Lenzen, M., Malik, A., Wei, L., & Reinheimer, D. Global food-miles account for nearly 20% of total food-systems emissions. Nature Food 2022, 3, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Chen, L. Location Optimization of Fresh Agricultural Products Cold Chain. Sustainability, 2022, 14, Article 6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Agricultural statistics - main results; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2021; https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat. [Google Scholar]

- Coldiretti. Campagna Amica: Rapporto sull’economia agricola locale; Coldiretti: Rome, Italy, 2022; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Graeub, B. E.; Chappell, M. J.; Wittman, H.; Ledermann, S.; Kerr, R. B.; Gemmill-Herren, B. The state of family farms in the world. World Development, 2016, 87; pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Universidad de Wageningen. Cost effectiveness in short supply chains of agricultural products; Wageningen UR: Wageningen, Netherlands, 2021; pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Cold Chain Logistics Network Design for Fresh Agricultural Products. Sustainability, 2023, 15, Article 10021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amamou, A.; Chabouh, S.; Sidhom, L.; Zouari, A.; Mami, A. Agri-Food Supply Chain Sustainability Indicators from a Multi-Capital Perspective: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 2025, 17, Article 4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghannam, A.; Mesias, F. J.; Escribano, M.; et al. Consumers’ Perspectives on Alternative Short Food Supply Chains Based on social media: A Focus Group Study in Spain. Foods, 2020, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundler, P.; Jean-Gagnon, J. Short food supply chains, labour productivity and fair earnings: an impossible equation? Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 2020, 35, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Agricultural price data in the European Union; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2022; https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, C.; Raimbert, C.; Raton, G. Is the logistical engagement of stakeholders in short food chains a crucible of alternativity? 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Mosavi, A.; Lakner, Z. Food Supply Chain and Business Model Innovation. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).