1. Introduction

In the traditional flight departure process, the aircraft starts its engines as it is pushed out of the berth by a tractor, and then the aircraft taxis to the runway and waits for takeoff [

1,

2]. In this departure mode, the aircraft engine is always idling and running inefficiently, which consumes a large amount of fuel, emits waste, and creates a high risk of human inhalation exposure, and the coordinated operation of multiple departments leads to inefficiency [

3]. Therefore, this departure mode can no longer meet the requirements of high-quality and healthy development in civil aviation. In this regard, the new towing taxi-out departure mode, in which the tractor connects to the front landing gear of the aircraft and tows it from the berth to the takeoff runway, has become the focus of domestic and international research [

4].

Despite improvements in the safety of aircraft departures over the past two decades, safety hazards still exist, and the damage caused by accidents still requires a high level of attention. Statistics show that human error is the leading cause of accidents during aircraft departures [

5,

6], resulting in injuries or deaths, damage to the aircraft or tractor, and environmental pollution. Therefore, it is necessary to identify potential human errors and estimate their probability.

In recent years, the study of human behavior has become a core topic for safety management, reliability engineers, and civil aviation authorities owing to the crucial role of human factors in reducing the incidence of aircraft departure accidents. In particular, human reliability analysis (HRA), which helps identify the causes and consequences of human errors in different human-machine systems [

7], has been a core research area. Human reliability refers to the ability of a human to accomplish a specific task without error under specific conditions and within a specific period of time [

8]. Currently, HRA consists of three main stages: qualitative evaluation, modeling, and quantitative calculation. Quantitative calculations are conducted to calculate the human error probability (HEP) value for each task, which is the main aim of HRA.

Researchers in various countries have proposed different HRA methods, such as the Technique for Human Error Rate Prediction [

9], Success Likelihood Index Methodology (SLIM) [

10], Human Error Assessment and Reduction Technique (HEART) [

11], Cognitive Reliability and Error Analysis Method (CREAM) [

12], and Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) [

13], which are widely used today. However, they all have drawbacks, such as a high degree of subjectivity and uncertainty, and some potential dependencies between tasks are easy to ignore [

14]. Faced with these limitations, researchers have extended these methods using Dempster–Shafer (D-S) evidence theory, evidential reasoning, Bayesian networks (BNs), and fuzzy set theory to overcome the drawbacks of these methods and make them more applicable to the domain under study [

15]. Akyuz [

16] applied fuzzy set theory to SLIM to address the ambiguity of expert judgment and decision expression in the weighting process and demonstrated the proposed method using an example of the abandon ship procedures in maritime transportation. Abrishami et al. [

17] proposed a BN-SLIM model that not only accounts for the possible dependencies between tasks but also reduces the subjectivity and uncertainty due to the lack of data and expert judgment. Sezer et al. [

18] extended SLIM with evidential reasoning to address the subjectivity of expert judgment in weighting and rating. Zhou et al. [

19] combined D-S evidence theory with HEART to fuse the opinions of multiple experts and assessed HEP during locomotive driving. Similarly, Musharraf et al. [

20] combined evidence theory with BNs to overcome the problem of inconsistent judgments among multiple experts and assessed HEP during offshore emergency conditions. Groth and Swiler [

21] transformed Standardized Plant Analysis Risk Human Reliability Analysis (SPAR-H) into a BN, not only accounting for the interdependencies among performance-shaping factors but also showing how to utilize the SPAR-H BN for reasoning. Ji et al. [

22] combined the best-worst method (BWM) and cloud modeling, where the BWM improved the accuracy of the weighting of the influencing factors, and cloud modeling was used to deal with the uncertainty of the expert judgment.

Although a variety of HRA methods have been proposed, each method has advantages and disadvantages, which requires us to choose the appropriate analysis method with the most appropriate characteristics for the specific task. Studies have shown that HEART, THERP, and SLIM are generally the most commonly used methods for HRA [

23]. HEART is a fast, reliable, and understandable method that calculates HEP by determining the error-producing conditions [

24]. However, HEART is highly subjective, and the 38 error-producing conditions that it contains do not cover the entire civil aircraft towing departure process [

25,

26]. THERP, although relatively simple, does not provide sufficient guidance for modeling performance-shaping factors and developing specific scenarios [

27,

28]. In contrast, SLIM is a relatively effective method when there is not enough data to calculate the HEP of a specific task or system [

29,

30]. The literature revealed that there are few domestic and international reports on departure accidents, so it is difficult for researchers to construct an aircraft departure human error database by extracting data from the text of accident reports. Therefore, SLIM based on expert experience is more suitable as an HRA method in the process of civil aircraft towing departure.

This paper presents a practical SLIM-based tool that can be used to calculate the HEP during civil aircraft towing departure. SLIM is the most effective tool to start with when data are scarce. This method was proposed by Embrey et al. [

10] and is commonly used for calculating HEP based on expert experience. Human error is due to the combined effect of multiple performance-shaping factors in a specific task [

31]. During the calculation of HEP, the determination of performance-shaping factors and their weights and ratings are given by expert assessments, which makes the method subjective and uncertain to varying degrees [

17]. To reduce this drawback, this paper extends SLIM by leveraging the advantages of the D-S evidence theory, which can overcome the inconsistency among expert judgments. To demonstrate the superiority of DS-SLIM over SLIM, the civil aircraft towing departure process is used as an example. This paper is the first application of HRA to the field of aircraft towing, providing both a practical research tool and significant research results. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces the basic research methodology and the proposed research methodology.

Section 3 applies the proposed methodology to the civil aircraft towing departure operation.

Section 4 presents the research results and discussion.

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Methodology

This section presents a brief overview of the basic research methodology, followed by a detailed description of the proposed research methodology.

2.1. SLIM

SLIM originates from the field of decision analysis and is commonly used in HRA. The method states that an operator’s success in completing a task depends on the combined effect of multiple performance-shaping factors (PSFs). The PSFs and their weights and ratings for a specific task are evaluated by a panel of experts. The weight of a PSF indicates the importance of the PSF to the task, and the rating of the PSF indicates the effectiveness of the PSF in executing the task [

32]. The method, although heavily dependent on the judgment of experts, is practical in cases where human error data are difficult to obtain. As a result, SLIM has been used in the marine, railroad, and aerospace industries [

33,

34,

35]. The main steps of SLIM are task analysis, scenario definition, PSF derivation, PSF rating, PSF weighting, success likelihood index (SLI) determination, and HEP calculation.

SLI indicates the composite rating for the task, the higher the SLI, the higher the probability of success [

36]. SLI is calculated by Eq. (1).

where

n denotes the number of PSFs,

Ri denotes the rating of the

ith PSF, and

Wi denotes the weight of the

ith PSF.

After calculating the SLI value, the SLI value can be converted to the HEP value using Eq. (2).

where

a and

b are both coefficients to be determined and can be derived from known upper and lower limits of the HEP.

2.2. D-S Evidence Theory

D-S evidence theory, which originated from Dempster’s research [

37] in the use of upper and lower limits of probability to solve multi-valued mapping problems and was later developed by Shafer [

38], is a mathematical method used for dealing with uncertainty reasoning problems. The a priori data needed in evidence theory is more intuitive and easier to obtain than in probabilistic reasoning theory, coupled with the fact that Dempster’s combination rule can synthesize knowledge or data from different experts or data sources, which has led to the widespread use of D-S evidence theory in fields such as expert systems and information fusion [

39,

40,

41,

42].

In D-S evidence theory, the sample space consisting of all propositions is defined as the frame of discernment and is denoted as Θ, which is a complete set of N mutually exclusive elements representing all possible answers to a given question. The set consisting of all subsets of Θ is called its power set, denoted as 2

Θ.

Basic Probability Assignment (BPA) is the process of calculating the basic probability of each piece of evidence in the frame of discernment Θ. This process is accomplished using the BPA function (also called the mass function). The BPA function, denoted as m, is a mapping of 2

Θ to [0,1] and is defined as

which must satisfy the following two conditions:

where m(A) denotes the level of trust in A based on the current environment, and A is called a focal element, such that m(A) > 0 (A∈2

Θ).

According to D-S evidence theory, the rules for combining multiple mass functions are expressed as follows:

K is a normalization constant that represents the degree of conflict between multiple independent pieces of evidence m1, m2, ..., mn. The larger the value of K, the greater the degree of conflict [

43,

44,

45].

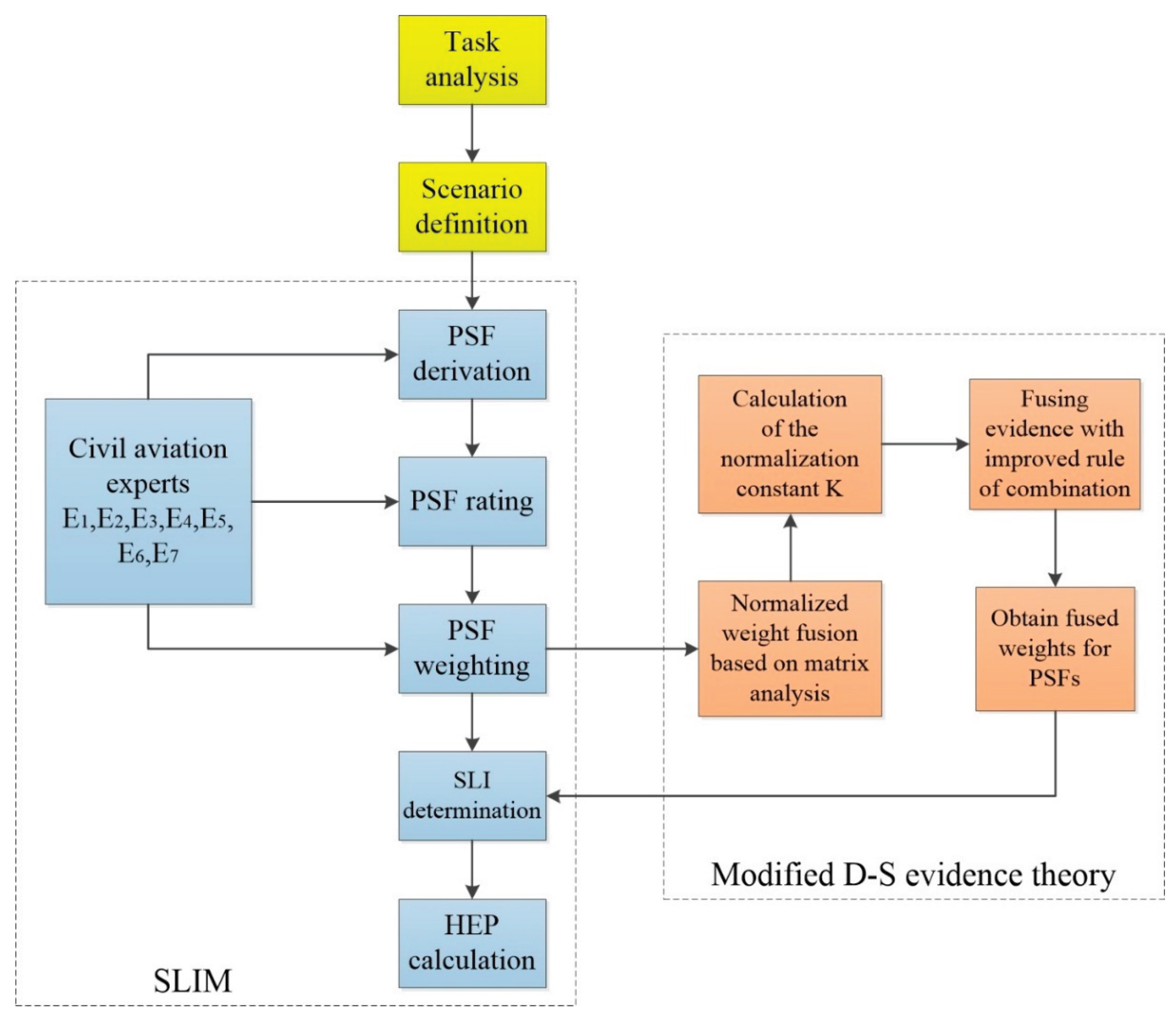

2.3. The Proposed Methodology: D-S Evidence Theory-Extended SLIM Approach

In this section, a D-S evidence theory-extended SLIM approach is proposed for quantitatively calculating the HEP in the civil aircraft towing departure process. The flowchart of the proposed method is shown in

Figure 1. The steps of the method are summarized as follows.

Step 1. Task analysis

The task analysis identifies the activities that must be completed by the staff in the civil aircraft towing departure process. This is performed according to hierarchical task analysis (HTA), where the main tasks are divided into sub-tasks [

46,

47]. In addition, this step is designed to prevent possible accidents by identifying each step that can go wrong in the civil aircraft towing departure process.

Step 2. Scenario definition

This step defines various scenarios during the execution of tasks. A complete civil aircraft towing departure process is a complex human operation that is based on four closely linked elements: technology, physical environment, communication, and collaboration. The scenario definition provides a detailed description of the operation. As a result, we can clarify the operation environment and identify possible human errors more accurately.

Step 3. PSF derivation

In this step, the group of experts, after research and discussion, determines the set of PSFs that have the greatest impact on human performance. PSFs are a representation of the context, which is given different names in different HRA methods, such as error-producing conditions in HEART and common performance conditions in CREAM, and are indispensable in the probabilistic safety analysis of a system.

Step 4. PSF rating

In this step, the experts rate the individual PSFs for each task of the civil aircraft towing departure operation using an 8-point scale (from 1 to 9). Then, the arithmetic means are calculated for each task of the individual PSFs. The higher the rating, the more favorable it is for the operator to complete the task. The expert ratings of PSFs are independent of each other.

Step 5. PSF weighting

In this step, the experts assign values to the PSFs between 0 and 100 based on their importance in relation to the task and then calculate the normalized weight of each PSF. In this way, we can gain a preliminary understanding of the relative impact of PSFs on civil aircraft towing departure operations. This step also applies the D-S evidence theory to fuse the weights given by multiple experts and deal with the subjectivity and uncertainty generated by the experts.

However, traditional D-S evidence theory has two obvious drawbacks. First, when there is a large conflict between the evidence (i.e., the K-value is close to 1), direct computation using Eq. (8) may provide less desirable results. Second, the required time increases exponentially as the number of experts increases, and directly using Eq. (8) for data fusion causes the focal element explosion problem. Thus, the present study proposes a D-S combination rule based on matrix analysis and weight assignment when performing data fusion [

48]. Matrix analysis is used to reduce the amount of computation, and weight assignment is used to solve the problem of conflicting evidence.

Assuming that there are n experts evaluating the system and that there are 6 PSFs, the BPAs given through the experts are

where

mij represents the BPA of the

jth PSF by the

ith expert, and hence the row sum of this matrix is 1.

We multiply the transpose of M1 with M2 to obtain the matrix R.

The sum of the principal diagonal elements in the matrix R is the numerator in the combination rule, and the sum of the non-principal diagonal elements is the degree of conflict K in the combination rule.

Multiplying the column matrix formed by the main diagonal elements of matrix R with M3 yields the new matrix R.

At this point, the sum of the principal diagonal elements of the matrix R is still the numerator in the combination rule, and the degree of conflict K is the sum of all the non-principal diagonal elements of the original matrix R and the present matrix R.

This continues until the fusion of all n experts’ assessments is completed. The sum of the non-principal diagonal elements of all matrices R in this process is the degree of conflict K between the n pieces of evidence.

When the value of K is close to 1, it is likely to produce counterintuitive fusion results. In this case, the system can be improved using Eq. (13).

where

is the probability assignment function for evidence conflict (i.e., the degree of conflict between evidence, K), which is assigned to each element of the frame of discernment. Therefore, this probability assignment function satisfies

. Since K no longer lies in the denominator, there is no need to worry about (1 − K)→0, indicating that this improvement is successful [

49].

Step 6. SLI determination

SLI can be calculated using Eq. (1). The larger the SLI value, the smaller the probability of an error occurring.

Step 7. HEP calculation

After calculating the SLI values, they can be converted to HEP values using Eq. (2). In this step, absolute probability judgments for endpoints are used to determine the absolute probability of the failure of endpoints to obtain the values of constants a and b.

3. Calculation of HEP in Civil Aircraft Towing Departure Process

In this section, the proposed DS-SLIM model is demonstrated using an example of a civil aircraft towing departure operation. This is the first application of the D-S evidence theory-extended SLIM approach in the field of civil aircraft towing departure, and the research results are innovative and referable.

3.1. Problem Statement

In the towing taxi-out departure mode, the aircraft relies on the tractor power to directly complete the efficient transfer from the berth to the takeoff runway. This process requires close collaboration and communication between the driver, pilot, air traffic control (ATC), and other staff. If there is an improper operation by the personnel, collision, side-slip, tail-flip or even folding may occur, which may lead to serious accidents. Therefore, the human factor is important to consider in the process, and it is necessary to identify potential human errors and estimate the probability of their occurrence.

3.2. Task Analysis and Scenario Definition

The HTA consists of a set of hierarchical tasks that can provide a systematic description of the complete operational process. The HTA was used by seven experts to divide the complete civil aircraft towing departure process into four main tasks, namely preparation for towing taxi-out, push-back, towing taxi-out, and separation. Then, the sub-tasks related to human factors in each main task were analyzed, and a total of 36 sub-tasks were defined.

Table 1 outlines the detailed task analysis.

Once the task analysis was completed, a realistic civil aircraft towing departure scenario was defined, which provided a detailed description of the operation and environment for expert evaluation. The civil aircraft towing departure task began in the morning with clear weather and unobstructed roads. Pilots, drivers, ground crew, and ATC were involved throughout the task. The working environment, time pressure, staff experience, proficiency, and skills of communication and collaboration all met the requirements of the job. Moreover, the pilots and drivers were in high spirits owing to adequate rest. During the towing and taxi-out, pilots and drivers strictly followed the prescribed speeds and routes, following ground traffic rules and airport regulations. Moreover, the noise level and mental workload were acceptable.

3.3. Deriving and Rating PSF

The PSFs were determined by a panel of experts who relied on references, in addition to their own extensive experience. The expert group consisted of seven members, one professor, two masters, two drivers, and two pilots, who have solid theoretical knowledge and rich practical experience. The references came from the International Civil Aviation Organization and the Civil Aviation Administration of China, including papers reported by Akyuz et al., which are authoritative and referable. After research and discussion, a total of six PSFs, namely task complexity, environmental conditions, time pressure, training and exercises, experience, and communication, were identified (

Table 2). The experts rated the PSFs for each task using an 8-point scale (from 1 to 9). Then, the arithmetic means were calculated for each task of the six PSFs. The specific values are shown in

Table 3.

Table 2.

Tasks for civil aircraft towing taxi-out departure.

Table 2.

Tasks for civil aircraft towing taxi-out departure.

| PSF Number |

PSFs |

| PSF1 |

Task complexity |

| PSF2 |

Environmental conditions |

| PSF3 |

Time pressure |

| PSF4 |

Training and exercises |

| PSF5 |

Experience |

| PSF6 |

Communication |

Table 3.

Mean of PSF ratings.

Table 3.

Mean of PSF ratings.

| |

PSF1 |

PSF2 |

PSF3 |

PSF4 |

PSF5 |

PSF6 |

| 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1.1 |

6.8571 |

4.8571 |

4.4286 |

2.8571 |

4.4286 |

5.5714 |

| 1.2 |

6.0000 |

5.7143 |

4.1429 |

2.4286 |

3.2857 |

4.2857 |

| 1.3 |

5.8571 |

5.4286 |

4.8571 |

3.4286 |

3.4286 |

4.2857 |

| 1.4 |

6.0000 |

7.4286 |

4.8571 |

4.7143 |

4.2857 |

4.8571 |

| 1.5 |

5.8571 |

5.7143 |

5.4286 |

4.5714 |

3.5714 |

4.2857 |

| 1.6 |

4.4286 |

5.8571 |

5.0000 |

2.7143 |

1.5714 |

4.8571 |

| 1.7 |

6.1429 |

6.1429 |

6.1429 |

3.2857 |

2.4286 |

5.7143 |

| 1.8 |

5.5714 |

5.1429 |

5.5714 |

3.8571 |

3.7143 |

0.8571 |

| 1.9 |

5.0000 |

5.1429 |

5.8571 |

3.0000 |

2.5714 |

5.1429 |

| 1.10 |

2.4286 |

3.4286 |

3.5714 |

2.8571 |

3.0000 |

3.0000 |

| 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2.1 |

6.2857 |

6.4286 |

5.0000 |

4.0000 |

4.7143 |

1.0000 |

| 2.2 |

6.1429 |

5.0000 |

6.1429 |

3.5714 |

4.4286 |

5.1429 |

| 2.3 |

7.7143 |

6.2857 |

6.7143 |

3.8571 |

3.7143 |

1.5714 |

| 2.4 |

4.5714 |

6.2857 |

5.1429 |

3.0000 |

4.2857 |

1.5714 |

| 2.5 |

6.0000 |

6.2857 |

6.2857 |

3.4286 |

4.5714 |

3.8571 |

| 2.6 |

7.2857 |

6.1429 |

6.2857 |

3.8571 |

4.5714 |

1.8571 |

| 2.7 |

3.5714 |

3.8571 |

5.4286 |

2.2857 |

2.0000 |

2.5714 |

| 2.8 |

4.2857 |

3.1429 |

5.5714 |

2.4286 |

2.4286 |

3.1429 |

| 2.9 |

4.4286 |

4.1429 |

5.4286 |

3.4286 |

3.0000 |

4.1429 |

| 2.10 |

5.4286 |

4.1429 |

6.1429 |

3.7143 |

3.0000 |

4.5714 |

| 2.11 |

0.5714 |

2.0000 |

3.1429 |

1.5714 |

1.8571 |

3.8571 |

| 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3.1 |

6.4286 |

6.2857 |

5.5714 |

4.0000 |

4.0000 |

0.7143 |

| 3.2 |

5.0000 |

3.5714 |

6.0000 |

3.5714 |

4.5714 |

4.0000 |

| 3.3 |

7.0000 |

5.0000 |

5.5714 |

4.4286 |

5.5714 |

5.0000 |

| 3.4 |

5.1429 |

5.8571 |

3.8571 |

3.4286 |

2.7143 |

0.8571 |

| 3.5 |

6.1429 |

5.1429 |

6.5714 |

4.4286 |

4.4286 |

4.8571 |

| 3.6 |

2.2857 |

1.8571 |

3.5714 |

1.7143 |

2.1429 |

2.7143 |

| 3.7 |

1.7143 |

2.8571 |

2.7143 |

1.5714 |

2.2857 |

1.1429 |

| 3.8 |

5.1429 |

3.2857 |

4.2857 |

2.7143 |

3.1429 |

3.1429 |

| 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4.1 |

6.7143 |

6.4286 |

4.4286 |

2.7143 |

4.1429 |

1.5714 |

| 4.2 |

6.2857 |

2.5714 |

6.7143 |

4.2857 |

5.1429 |

5.7143 |

| 4.3 |

7.0000 |

4.0000 |

5.2857 |

3.4286 |

5.4286 |

2.5714 |

| 4.4 |

5.0000 |

4.0000 |

5.5714 |

3.5714 |

3.7143 |

0.5714 |

| 4.5 |

6.5714 |

6.1429 |

5.7143 |

3.7143 |

4.8571 |

5.2857 |

| 4.6 |

5.4286 |

4.2857 |

6.5714 |

4.1429 |

4.2857 |

4.5714 |

| 4.7 |

5.2857 |

3.7143 |

4.2857 |

3.2857 |

3.7143 |

3.8571 |

3.4. PSF Weighting

After deriving the PSFs, the experts assigned values between 0 and 100. The specific values are shown in

Table 4. Considering the differences in the theoretical knowledge and practical experience of each expert, the rating results are naturally different. Considering the normalized weight given by each expert as evidence, fusing the weights given by multiple experts can be regarded as an evidence fusion problem. Because the experts have different knowledge backgrounds, conflicts among them need to be considered before fusing their normalized weights. Therefore, we need to calculate the normalization constant K that represents the degree of conflict among them.

The BPA function can be derived from

Table 4 as

Multiplying the transpose of M1 with M2 according to Eq. (11) yields the matrix R1.

The sum of the non-primary diagonal elements of matrix R1 is denoted as K1, K1 = 0.8322. The column matrix formed by the primary diagonal elements of matrix R1 is multiplied with M3 to obtain a new matrix R2. The sum of the non-primary diagonal elements of the new matrix R2 is calculated as K2, K2 = 0.1395. This process is repeated, and the matrices R1 to R6 and the normalization constant K are shown in

Table 5.

K = 0.99998 was calculated, indicating that there is clear conflict among the seven experts. Therefore, unsatisfactory results will be obtained using the traditional D-S combination rule. The fused weights calculated with the improved combination rule are shown in

Table 4.

3.5. SLI Determination and HEP Calculation

Through the above steps, we obtained the arithmetic mean for the rating and fusion values of the normalized weights. Then, the SLI values for each sub-task were calculated using Eq. (1), which were transformed into HEP values using Eq. (2), where a and b are two constants to be determined and need to be substituted with the known HEP and SLI values of the two sub-tasks to be determined. For civil aircraft towing departure operations, no HEP values for the relevant sub-tasks have been recorded in the literature or by civil aviation companies. Therefore, using absolute probability judgments for endpoints, the experts made a judgment on the best- and worst-case scenarios for the civil aircraft towing departure process [

16,

18,50]. After substituting these two endpoints (SLI = 1, HEP = 0.9 and SLI = 9, HEP = 10-4) into Eq. (2), solving the coupled equations yielded a = −1.1381 and b = 1.0328. The SLI and HEP values are shown in

Table 6.

4. Findings and Discussion

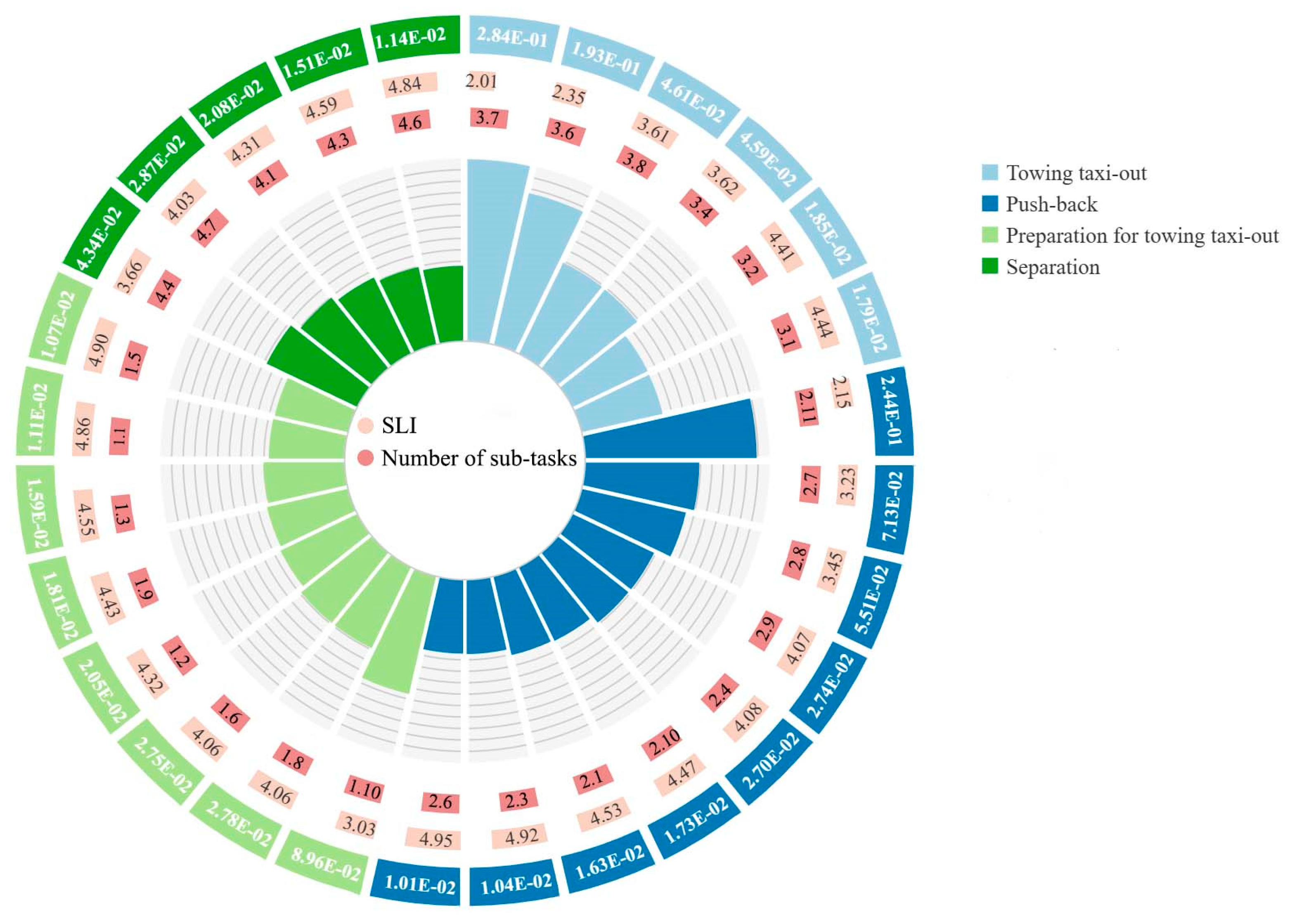

In this paper, the proposed DS-SLIM model is used to study human reliability during civil aircraft towing departure. After the experts finished their analysis, it was concluded that task complexity, environmental conditions, time pressure, training and exercises, experience, and communication are the six most important factors. Among them, training and exercises, task complexity, and communication have the most prominent influence on operators. As seen in

Figure 2, the four sub-tasks most prone to human error are sub-task 3.7 (Ensure safety during towing taxi-out, and if there is a danger, alert ATC, who issues a stop-and-return command), sub-task 2.11 (The tractor pushes the aircraft backward at a safe speed and angle to the designated position), sub-task 3.6 (Pilot taxis at prescribed speeds and routes, following ground traffic rules and airport regulations), and sub-task 1.10 (Pilot conducts final confirmation and evaluation of the route, weather conditions, and airport information).

Sub-task 3.7 has the highest HEP value (2.84E-01). During the towing taxi-out process, unpredictable conditions may be encountered, which require accurate and quick anticipation by the pilot and driver, as well as correct and reasonable instructions from ATC. Since this sub-task is executed when danger is imminent, failure of this sub-task can substantially increase the accident rate. In this case, experience and time pressure are the main factors leading to high HEP. To successfully complete this sub-task, the pilot and driver must be in good physical condition and remain focused at all times during the towing taxi-out process to deal with unexpected situations that may arise. In addition, basic knowledge and the exchange of experience among employees are necessary to help pilots and drivers anticipate unexpected situations.

Sub-task 2.11 also has a high HEP (2.44E-01). In this sub-task, the tractor is used to propel the aircraft backward into the berth at a safe speed and angle. Unlike conventional vehicle driving, the tractor driver needs to face backward during the push-back to obtain a better field of view. This difference in driving habits can present some challenges to the driver. If there is improper behavior during driving that causes the tractor to exceed a safe speed or angle, the tractor is highly susceptible to folding with the aircraft. The failure of sub-task 2.11 can result in a serious accident and requires a high level of attention. Training and exercises can improve the proficiency of drivers, thereby reducing the occurrence of human errors.

Sub-task 3.6 (HEP of 1.93E-01) also requires a high degree of attention. During towing taxi-out, the power system is provided by the tractor while the pilot needs to maneuver the aircraft-tractor system and complete a series of operations such as acceleration, deceleration, and turning. The process requires the pilot to keep a constant eye on the road conditions, as well as perform various operations using the human-machine interface, which requires significant attention and mental dexterity. As a result, time pressure may cause pilots to perform improper maneuvers. In addition, rain or snow can limit the speed of the tractor, and if the pilot fails to drive at a safe speed, the aircraft-tractor system is highly susceptible to side-slipping and folding during turns. To improve safety in the towing taxi-out process, the pilots’ work pressure can be reduced by optimizing the human-machine interface and designing intelligent driver assistance systems.

The checks in the preparation phase are critical, with sub-task 1.10 (HEP of 8.96E-02) having the greatest potential for human error. Even though the crew has scrutinized the fuel quantity, avionics system, air pressure system, and communication equipment, it is still possible that checks have been missed, thus requiring the pilot to perform a final confirmation and evaluation of the critical systems. In this case, because careful scrutiny was already performed by the crew, the pilot may be careless or even ignore this issue. This error may be caused by poor working conditions or lack of experience. In addition, fatigue or lack of safety awareness may also contribute to this situation.

According to the results, the HEP values of the sub-tasks in the process of civil aircraft towing departure are consistent with the experts’ expectations. Therefore, the four sub-tasks with the highest HEP values are discussed, and in addition to analyzing the causes and consequences of the errors, the corresponding reduction measures are given. This study can serve as a reference for civil aviation companies in the safety management of civil aircraft towing departure.

5. Conclusions

Civil aircraft towing departure is a highly dynamic multivariable process. Quantifying the HEP throughout the entire process can significantly improve the overall safety of the operation. Although SLIM is particularly effective for quantifying the HEP in the presence of data scarcity, we used the improved D-S evidence theory to fuse the judgments given by seven experts, thus developing a SLIM-based D-S evidence theory approach. This approach can overcome the problem of inconsistent expert judgments by fusing information from multiple sources, providing more reasonable data for the HEP calculation and serving as a practical tool for HRA in other industries.

Herein, HRA is applied to the field of civil aircraft towing departure for the first time, and the proposed DS-SLIM model is used to calculate the HEP of each sub-task in the departure process, which fills the research gap in this field. Based on SLIM, the group of experts derived a total of six PSFs, namely task complexity, environmental conditions, time pressure, training and exercises, experience, and communication, and gave their weights and ratings according to references and their own experience. To overcome the subjectivity and uncertainty of expert judgment in the weighting phase, an improved D-S evidence theory was used to fuse the normalized weights given by the seven experts. Then, the obtained arithmetic means for the rating and fusion values of the normalized weights were used to calculate the final HEP values. The resulting HEP values range from 5.81E-03 to 2.84E-01, where the three sub-tasks with the highest HEP values are sub-task 3.7 (2.84E-01), sub-task 2.11 (2.44E-01) and sub-task 3.6 (1.93E-01). In addition, we analyzed the possible causes and consequences of human errors in the sub-tasks with high HEP values and mentioned reduction strategies.

The quantification of correlations between PSFs and other human factors, as well as correlations among PSFs, can be considered in future studies using complex network theory. In addition, the identification and HEP calculation of unsafe behaviors in departure accidents can be further investigated. Moreover, other methods for dealing with uncertain information (e.g., BNs and fuzzy set theory) can be considered to extend SLIM and potentially improve the objectivity of expert judgments in the civil aircraft towing departure process.

Funding

This research was supported by research on active stabilization control of heavy load towing taxi-out system based on all wheel drive array chassis(3122025092), research on key technologies for external recognition and intelligent docking in unmanned traction scenarios(SATS202305) and research on the construction of robot digital twin model and real time data interaction technology (2021KJ102).

Data Availability Statement

All research data are supported for sharing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Qin JH, Liu JW, Lin QW, Zhang W. Research on Instability and “Jack-Knifing” of Civil Aircraft Towing Taxi-Out System. Appl. Sci. 2023; 13(6):3636.

- Qin JH, Wu H, Lin QW, Shen J, Zhang W. The Recovering Stability of a Towing Taxi-Out System from a Lateral Instability with Differential Braking Perspective: Modeling and Simulation. Electronics 2023; 12(10):2170. [CrossRef]

- Postorinoa MN, Mantecchinib L, Paganelli F. Improving taxi-out operations at city airports to reduce CO2 emissions. Transport Policy 2019; 80:167-176.

- Guo R, Zhang Y, Wang Q. Comparison of emerging ground propulsion systems for electrified aircraft taxi operations. Transportation Research Part C 2014; 44:98-109. [CrossRef]

- Hu WH, Carver JC, Anu V, Walia GS, Bradshaw GL. Using human error information for error prevention. Empir Software Eng 2018; 23:3768–3800.

- Kim J, Yu M, Hyun SS. Study on Factors That Influence Human Errors: Focused on Cabin Crew. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022; 19(9):5696. [CrossRef]

- Groth KM, Mosleh A. Deriving causal bayesian networks from human reliability analysis data: a methodology and example model. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part O J Risk Reliab 2012;226(4):361–79. [CrossRef]

- Swain AD, Guttmann HE. Handbook of human reliability analysis with emphasis on nuclear power. Washington: US Nuclear Regulatory; 1983.

- Swain AD. A method for performing a human-factors reliability analysis. Technical Report Archive & Image Library 1963;42(2):137.

- Embrey DE, Humphreys P, Rosa EA, et al. SLIM-MAUD: an approach to assessing human error probabilities using structured expert judgment. Volume I. Overview of SLIM-MAUD 1984.

- Williams JC. A Data-based method for assessing and reducing human error to improve operational performance. C// Human Factors and Power Plants, 1988.Conference Record for 1988 IEEE Fourth Conference on. IEEE Xplore; 1988. p.436–50.

- Hollnagel E. Cognitive reliability and error analysis method (CREAM). Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1998.

- Li WC, Harris D. Pilot error and its relationship with higher organizational levels: HFACS analysis of 523 accidents. Aviat Space Environ Med 2006; 77:1056–1061.

- Ekanem NJ, Mosleh A, Shen SH. Phoenix–a model-based human reliability analysis methodology: qualitative analysis procedure. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2016; 145:301–15. [CrossRef]

- Patriarcaa R, Ramosb M, Paltrinieric N, Massaiud S, Costantinoa F, Gravioa GD, Boring RL. Human reliability analysis: Exploring the intellectual structure of a research field. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2020; 203:107102.

- Akyuz E. Quantitative human error assessment during abandon ship procedures in maritime transportation. Ocean Engineering 2016; 120:21-29. [CrossRef]

- Abrishami S, Khakzad N, Hosseini SM, Gelder PV. BN-SLIM: A Bayesian Network methodology for human reliability assessment based on Success Likelihood Index Method (SLIM). Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2020; 193:106647.

- Sezer SI, Akyuz E, Gardoni P. Prediction of human error probability under Evidential Reasoning extended SLIM approach: The case of tank cleaning in chemical tanker. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2023; 238:109414. [CrossRef]

- Zhou JL, Lei Y, Chen Y. A hybrid HEART method to estimate human error probabilities in locomotive driving process. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2019; 188:80-89.

- Musharraf M, Hassan J, Khan F, Veitch B, MacKinnon S, Imtiaz S. Human reliability assessment during offshore emergency conditions. Saf Sci Nov. 2013;59(Supplement C):19–27. [CrossRef]

- Groth KM, Swiler LP. Bridging the gap between hra research and hra practice: a Bayesian Network version of SPAR-H. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2013; 115:33–42.

- Changcheng Ji, Fei Gao, Wenjiang Liu. Dependence assessment in human reliability analysis based on cloud model and best-worst method. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2024; 242:109770. [CrossRef]

- Islam R, Yu H, Abbassi R, Garaniya V, Khan F. Development of a monograph for human error likelihood assessment in marine operations. Saf Sci 2017; 91:33–9.

- Islam R, Abbassi R, Garaniya V, et al. Development of a human reliability assessment technique for the maintenance procedures of marine and offshore operations. J Loss Prev Process 50, Part B 2017:416–28. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, Kumar R. Evaluation of human error probability of disc brake unit assembly and wheel set maintenance of railway bogie. Procedia Manuf 2015; 3:3041–8.

- Noroozi A, Khan F, Mackinnon S, et al. Determination of human error probabilities in maintenance procedures of a pump. Proc Saf Environ Protec 2014; 92(2):131–41. [CrossRef]

- Jae MS, Park CK. A new dynamic HRA method and its application. J Korean Nuclear Soc 1995;27(3):292–300.

- Yang K; Tao LQ; Bai J. Assessment of Flight Crew Errors Based on THERP. ISAA 2013; 80:49-58.

- Abbassi R, Khan F, Garaniya V, et al. An integrated method for human error probability assessment during the maintenance of offshore facilities. Process Saf Environ Prot 2015; 94:172–9. [CrossRef]

- Khan FI, Amyotte PR, Dimattia DG. HEPI: a new tool for human error probability calculation for offshore operation. Saf Sci 2006; 44(4):313–34.

- Park KS, Lee J. A new method for estimating human error probabilities. AHP-SLIM. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2008; 93(4):578–87. [CrossRef]

- Kayisoglu G, Gunes B, Besikci EB. SLIM based methodology for human error probability calculation of bunker spills in maritime operations. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2022; 217:108052.

- Liu JL, Aydin M, Akyuz E, Arslan O, Uflaz E, Kurt RE, Turan O. Prediction of human–machine interface (HMI) operational errors for maritime autonomous surface ships (MASS). Journal of Marine Science and Technology 2022; 27:293–306. [CrossRef]

- Zhou JL, Lei Y. A slim integrated with empirical study and network analysis for human error assessment in the railway driving process. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2020; 204:107148. [CrossRef]

- Aydin M, U˘gurlu ¨O, Boran M. Assessment of human error contribution to maritime pilot transfer operation under HFACS-PV and SLIM approach. Ocean Eng 2022;266.

- Vestrucci P. The logistic model for assessing human error probabilities using the SLIM method. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 1988;21(3):189–96. [CrossRef]

- Dempster AP. Upper and lower probabilities induced by a multivalued mapping. Ann Math Stat 1967;38(2):325–39.

- Shafer G. A mathematical theory of evidence. Princeton university press; 1976(Vol. 42).

- Talavera A, Aguasca R, Galvan B, et al. Application of Dempster-Shafer theory for the quantification and; propagation of the uncertainty caused by the use of AIS data. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 2013;111(2):95–105.

- Liu Z, Pan Q, Dezert J, et al. Combination of classifiers with optimal weight based on evidential reasoning. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst 2017(99). 1-1. [CrossRef]

- Che X, Mi J, Chen D. Information fusion and numerical characterization of a multi-source information system. Knowl-Based Syst 2018; 145:121–33. [CrossRef]

- Fei L, Feng Y. A dynamic framework of multi-attribute decision making under Pythagorean fuzzy environment by using Dempster–Shafer theory. Eng Appl Artif Intell 2021; 101:104213.

- Wang H, Huang C, Yu H, Zhang J, Wei F. Method for fault location in a low-resistance grounded distribution network based on multi-source information fusion. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst 2021; 125:106384. [CrossRef]

- Si L, Wang Z, Tan C, Liu X. A novel approach for coal seam terrain prediction through information fusion of improved D-S evidence theory and neural network. Meas J Int Meas Confed 2014; 54:140–51. [CrossRef]

- Jiang W, Hu WW, Xie CH. A new engine fault diagnosis method based on multi-sensor data fusion. Appl Sci Basel 2017; 7(3):1–18.

- Akyuz E. Quantification of human error probability towards the gas inerting process on-board crude oil tankers. Saf Sci 2015; 80:77–86. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd A. Hierarchical task analysis. Taylor and Francis 2001, London.

- Wang J, Fan KF, Mo W. Method for information security risk assessment based on fuzzy set theory and DS evidence theory. Application Research of Computers 2017;34(11):3432-3436.

- Pan Y, Zhang LM, Li ZW, Ding LY. Improved Fuzzy Bayesian Network-Based Risk Analysis With Interval-Valued Fuzzy Sets and D-S Evidence Theory. IEEE transactions on fuzzy systems 2020; 28(9):2063-2077. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).