Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Identification on Causality of Waterborne Accidents

2.2. Research Gap Analysis

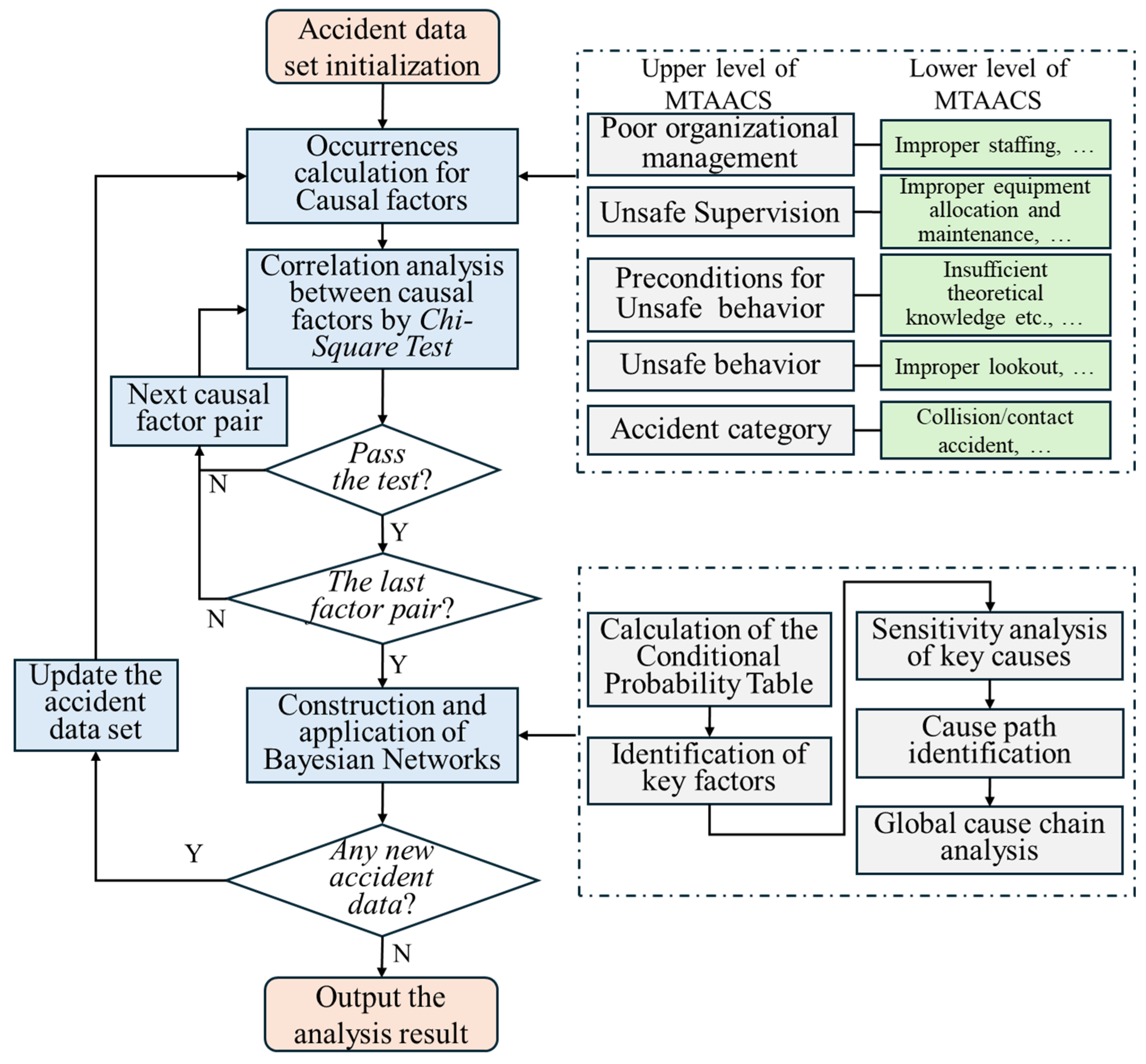

3. Data-Driven Hybrid Framework Based on the HFACS and Bayesian Network

3.1. Basic Data-Driven Analysis Framework

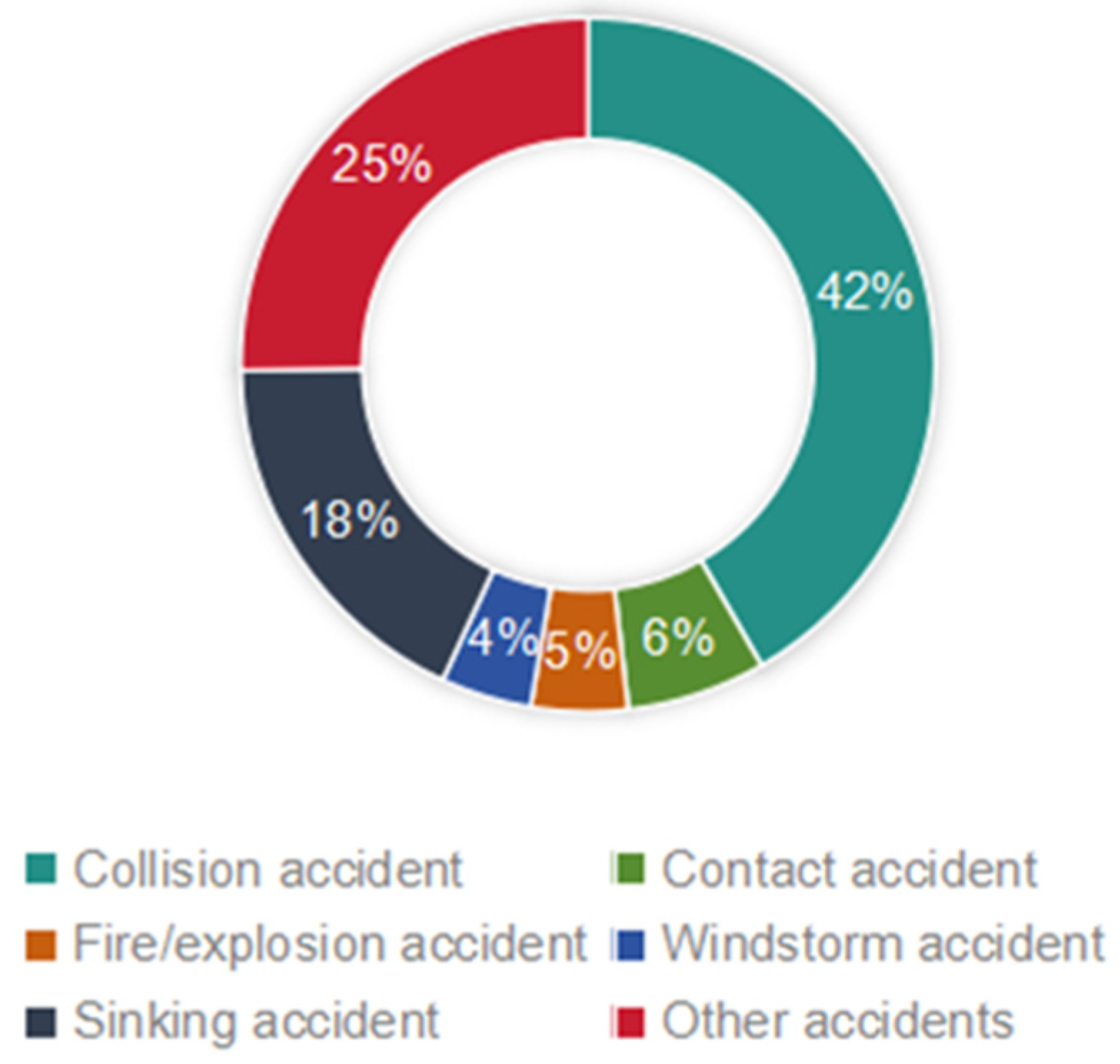

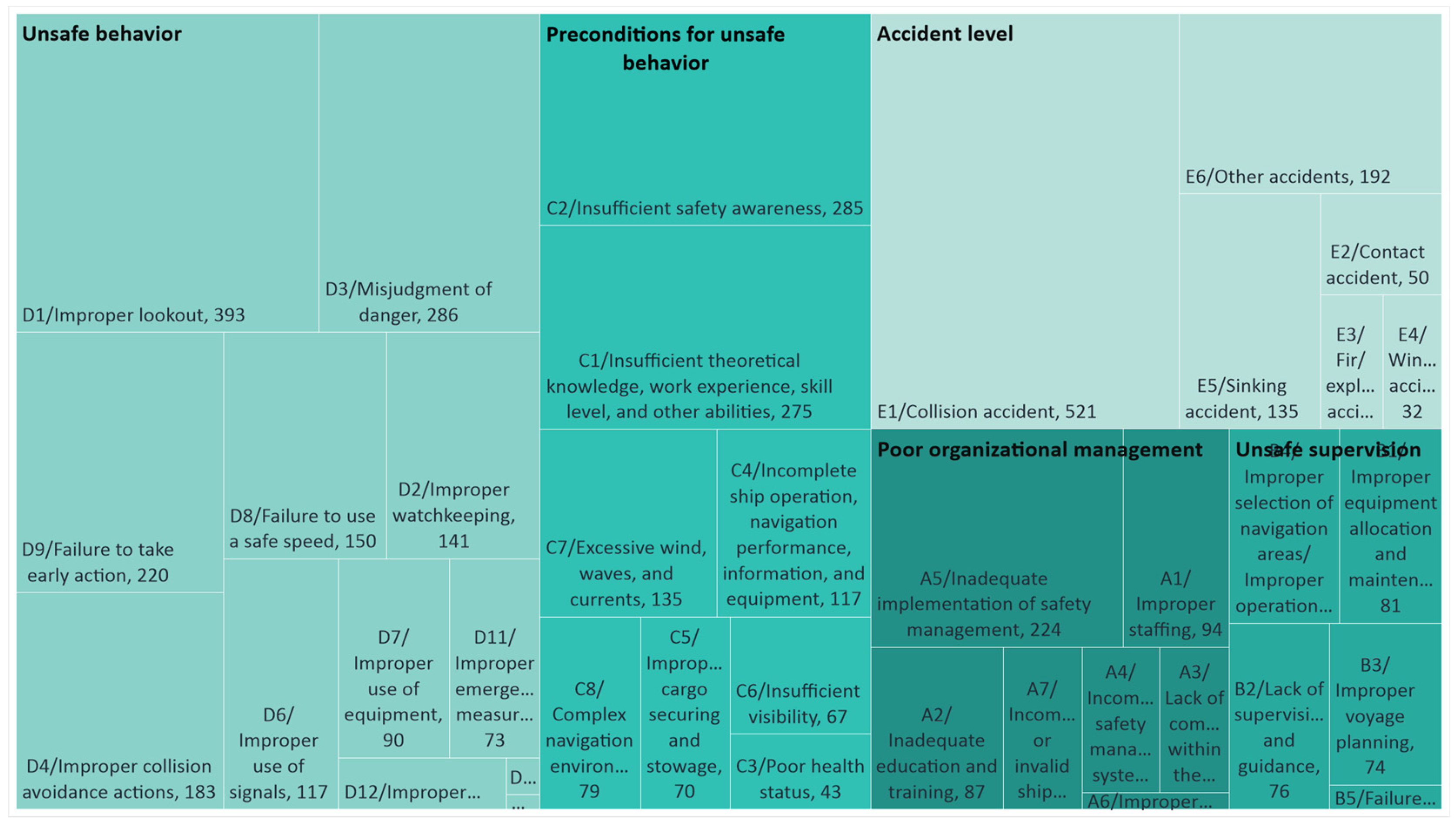

3.2. Data Collection and Basic Analysis

3.3. Improved HFACS (MTAACS) for Causes of Waterborne Traffic Accidents

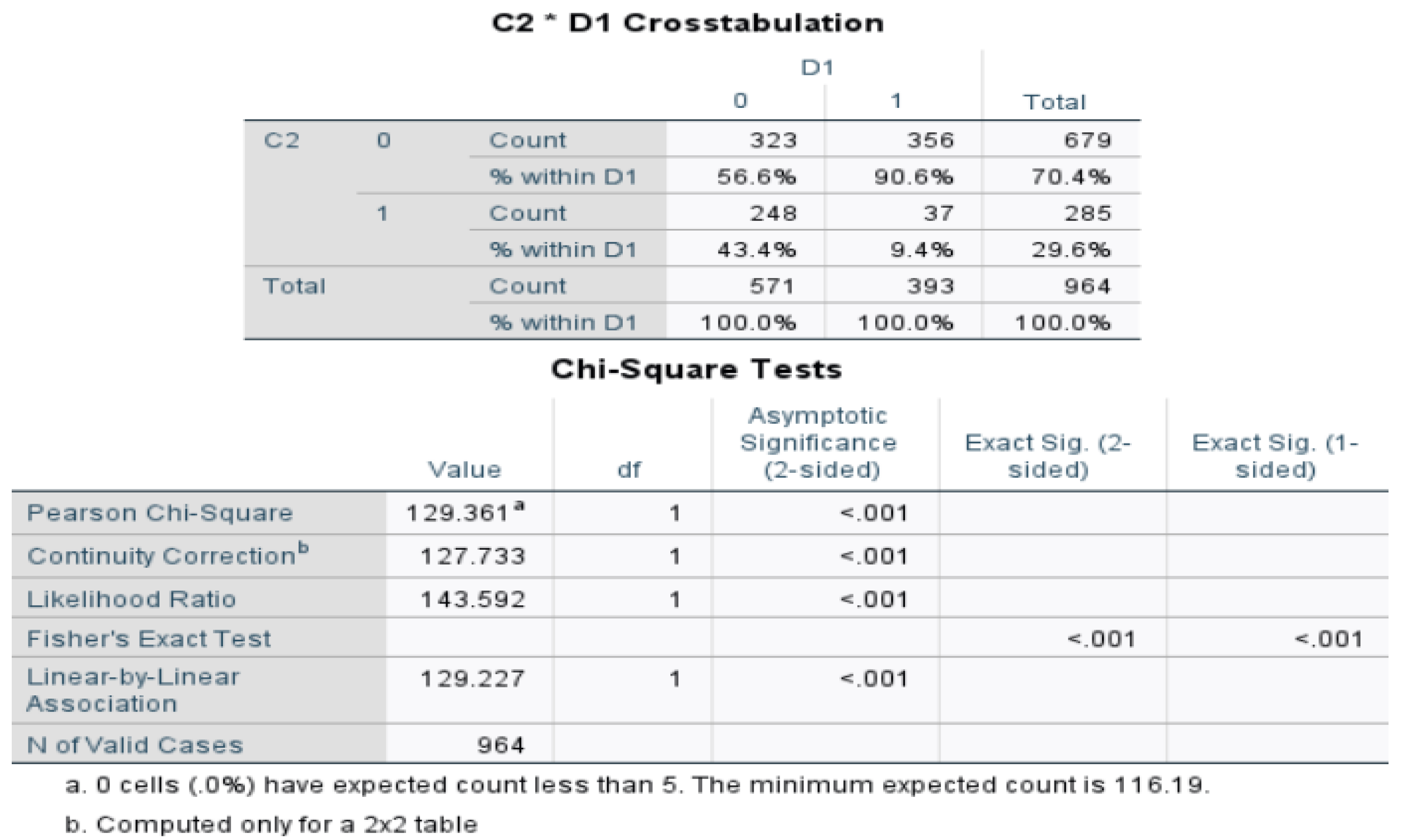

3.4. Correlation Analysis for Causal Factor Pairs

3.5. Construction of Bayesian Network for Causes of Waterborne Traffic Accidents

3.5.1. Basic Concepts and Formulas

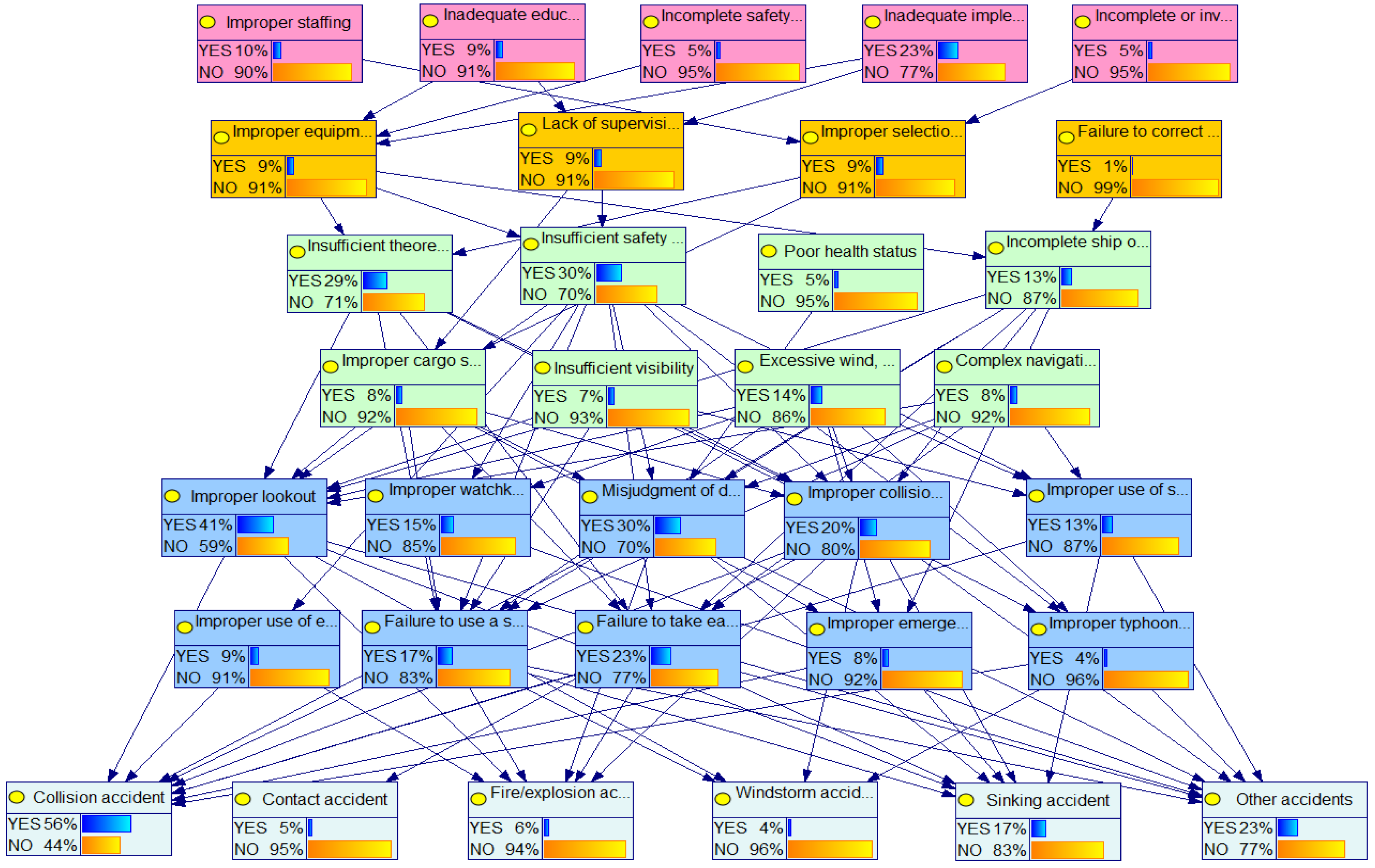

3.5.2. Bayesian Network for Causes of Water Traffic Accidents

4. Analysis of the Causal Chain of Waterborne Traffic Accidents

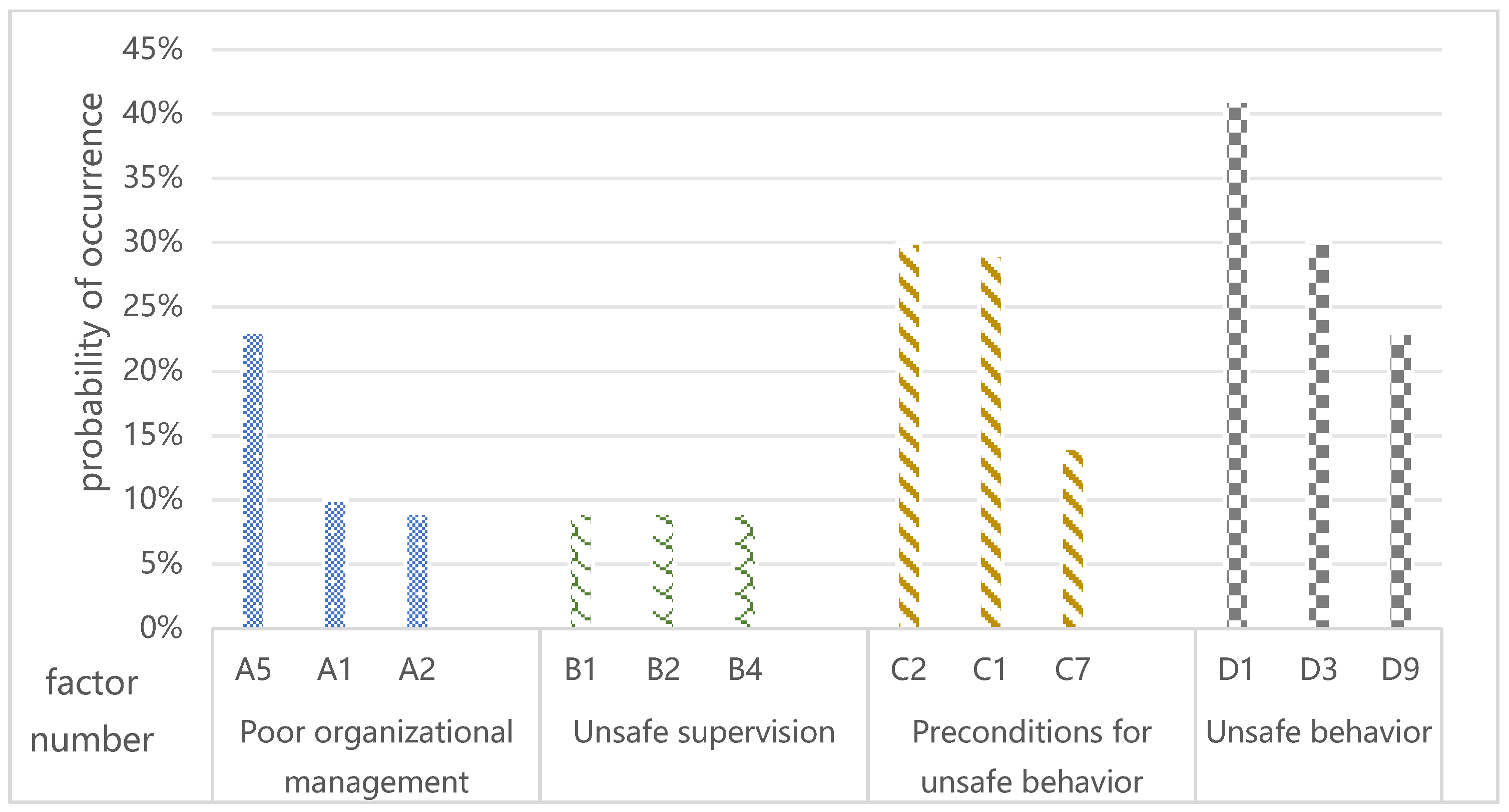

4.1. Identification of Key Factors in Waterborne Traffic Accidents

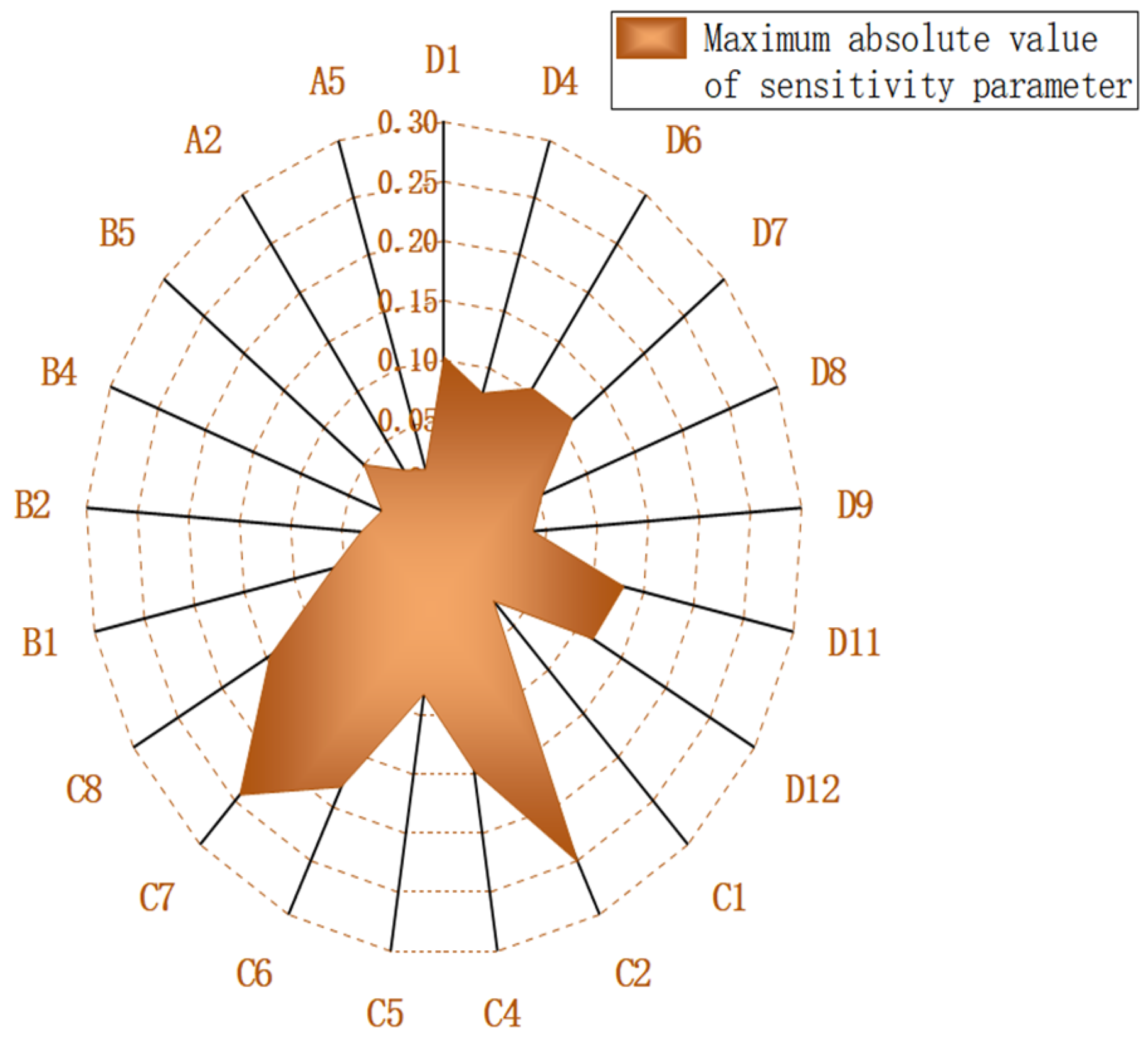

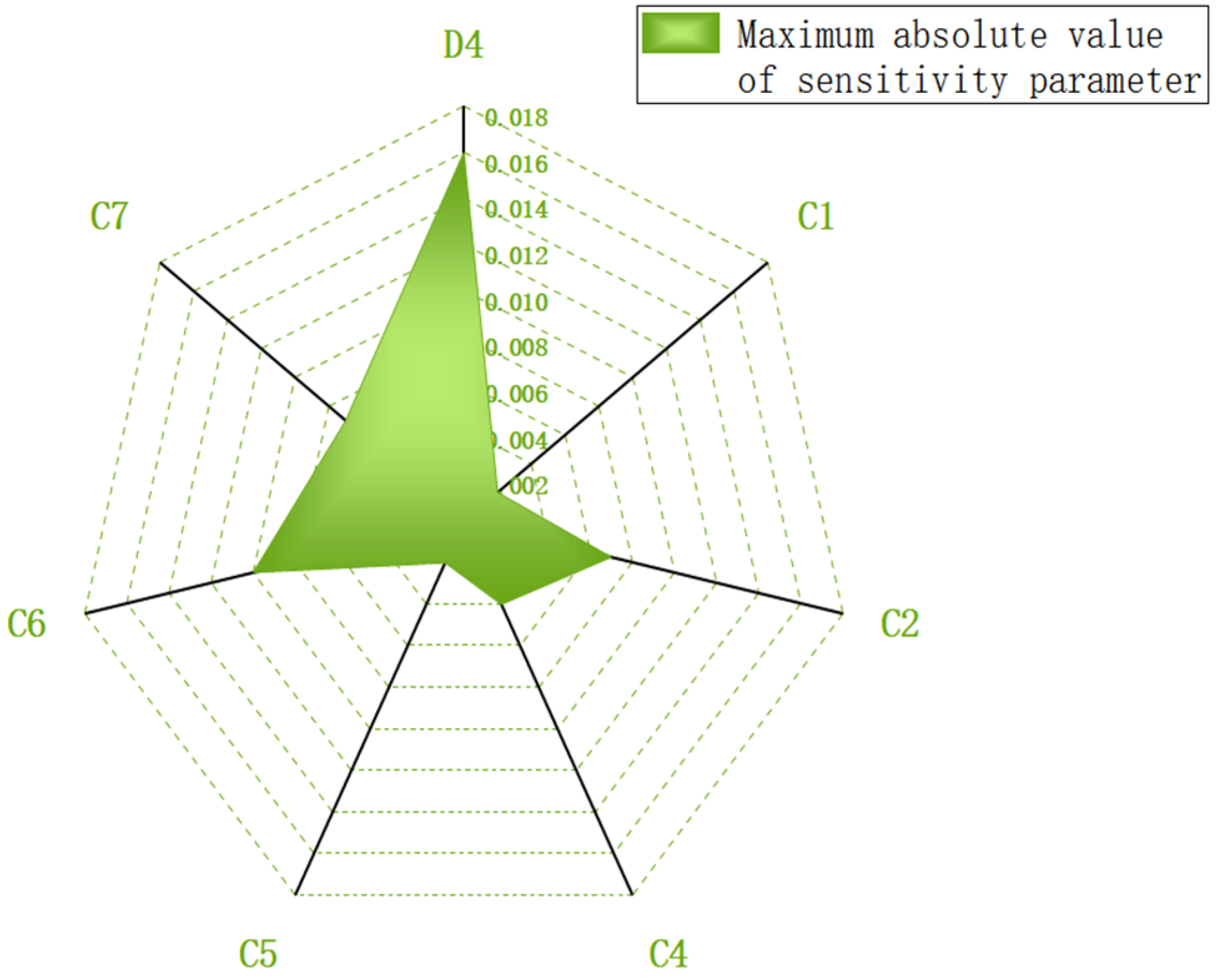

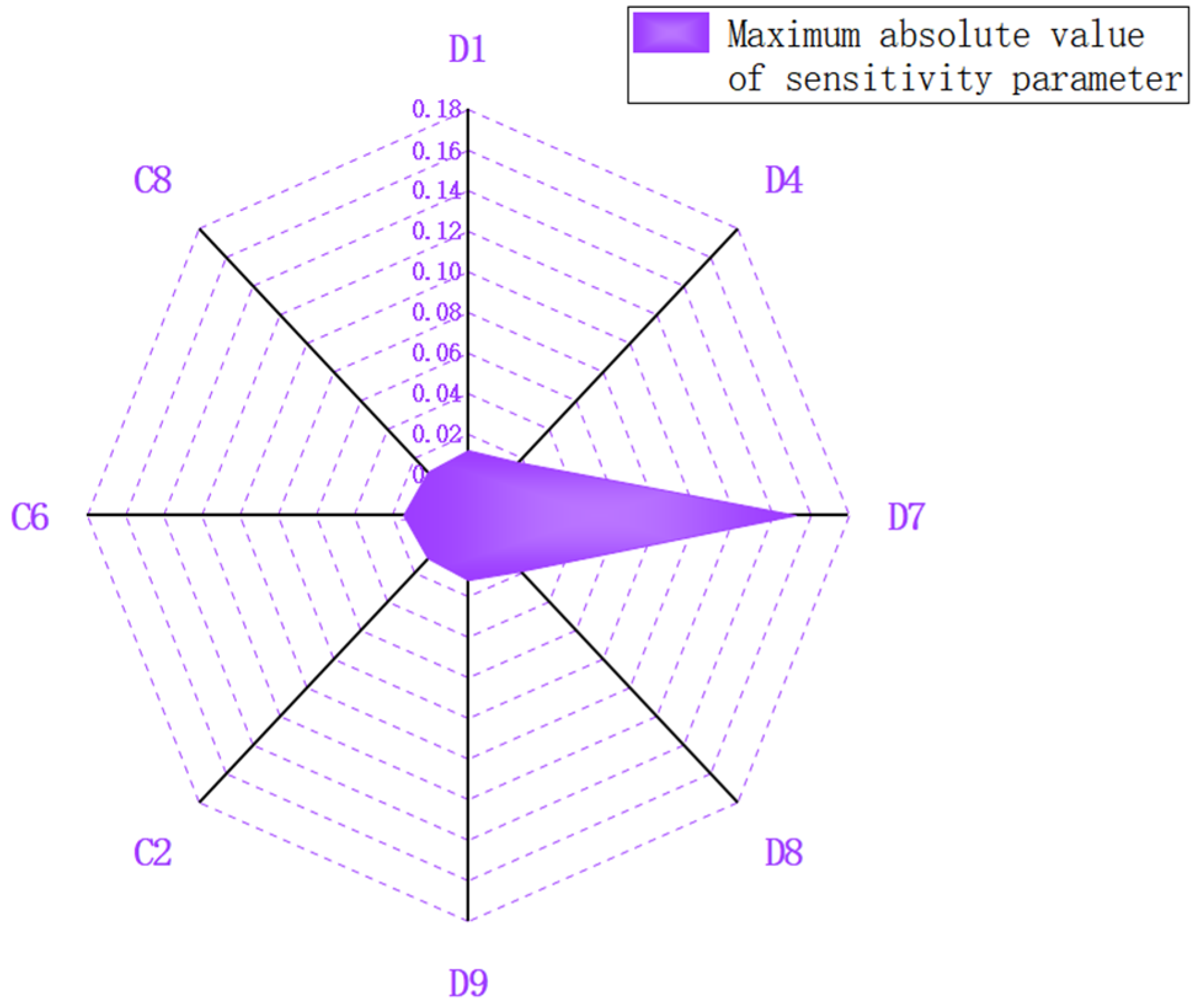

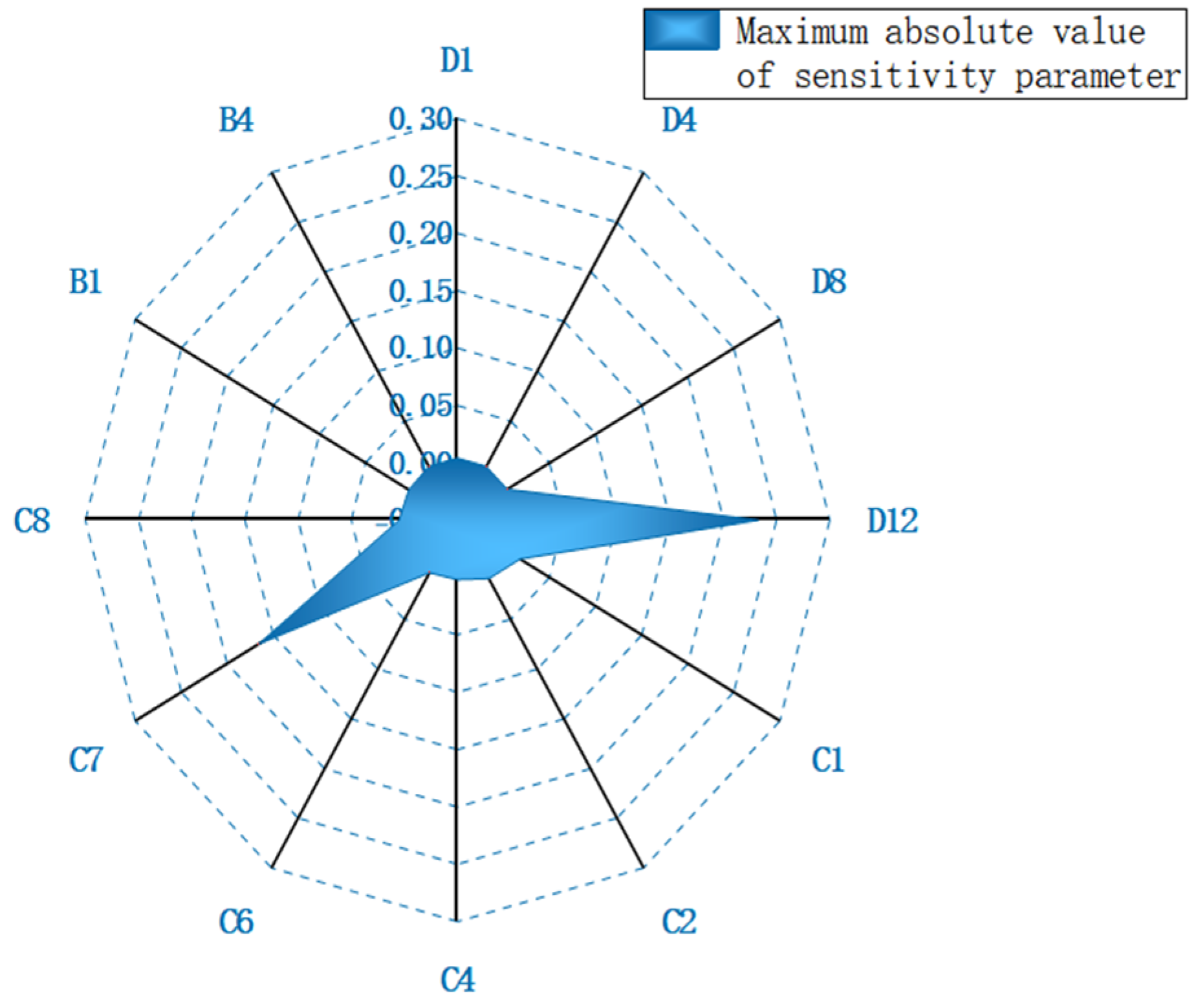

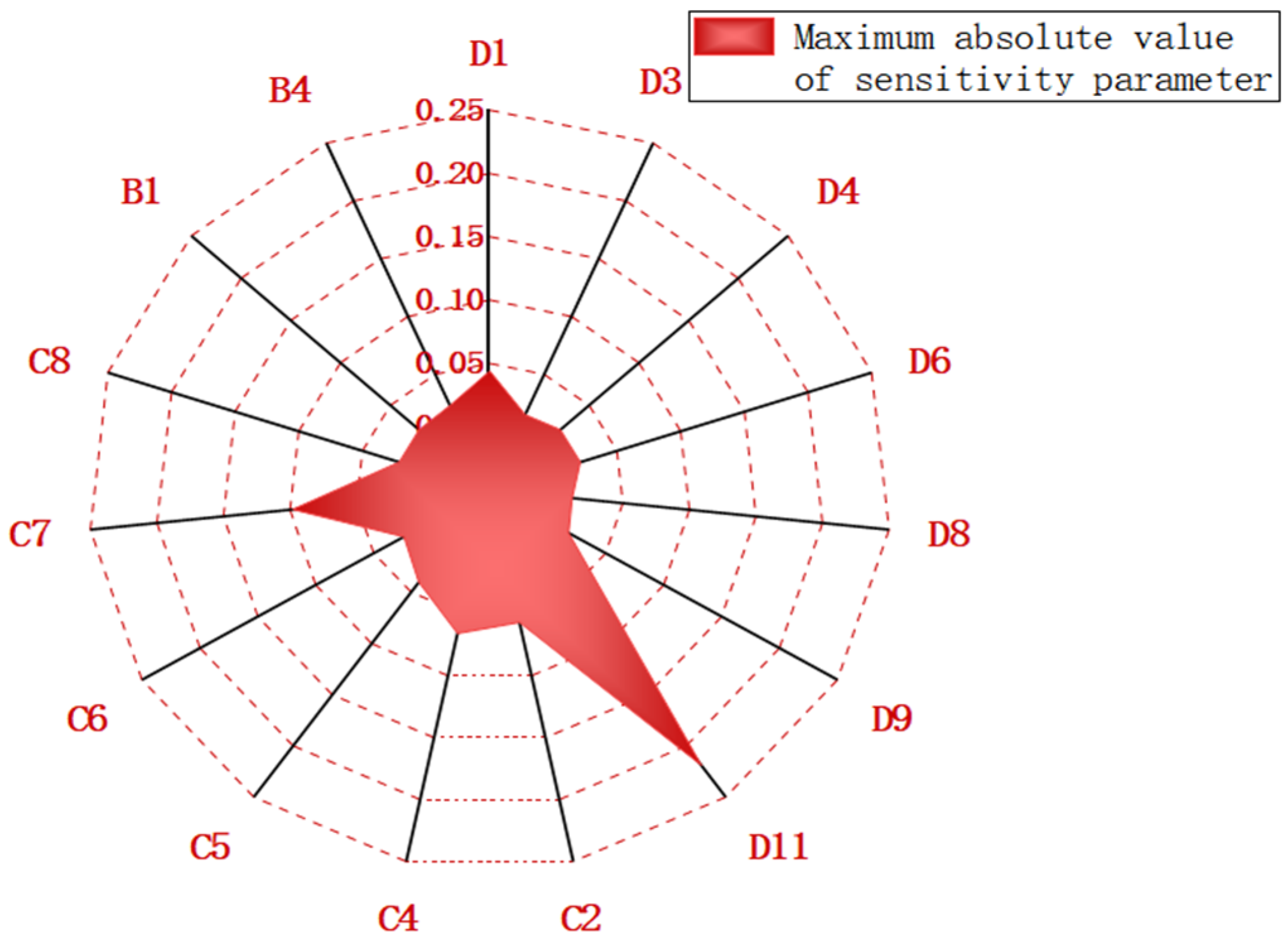

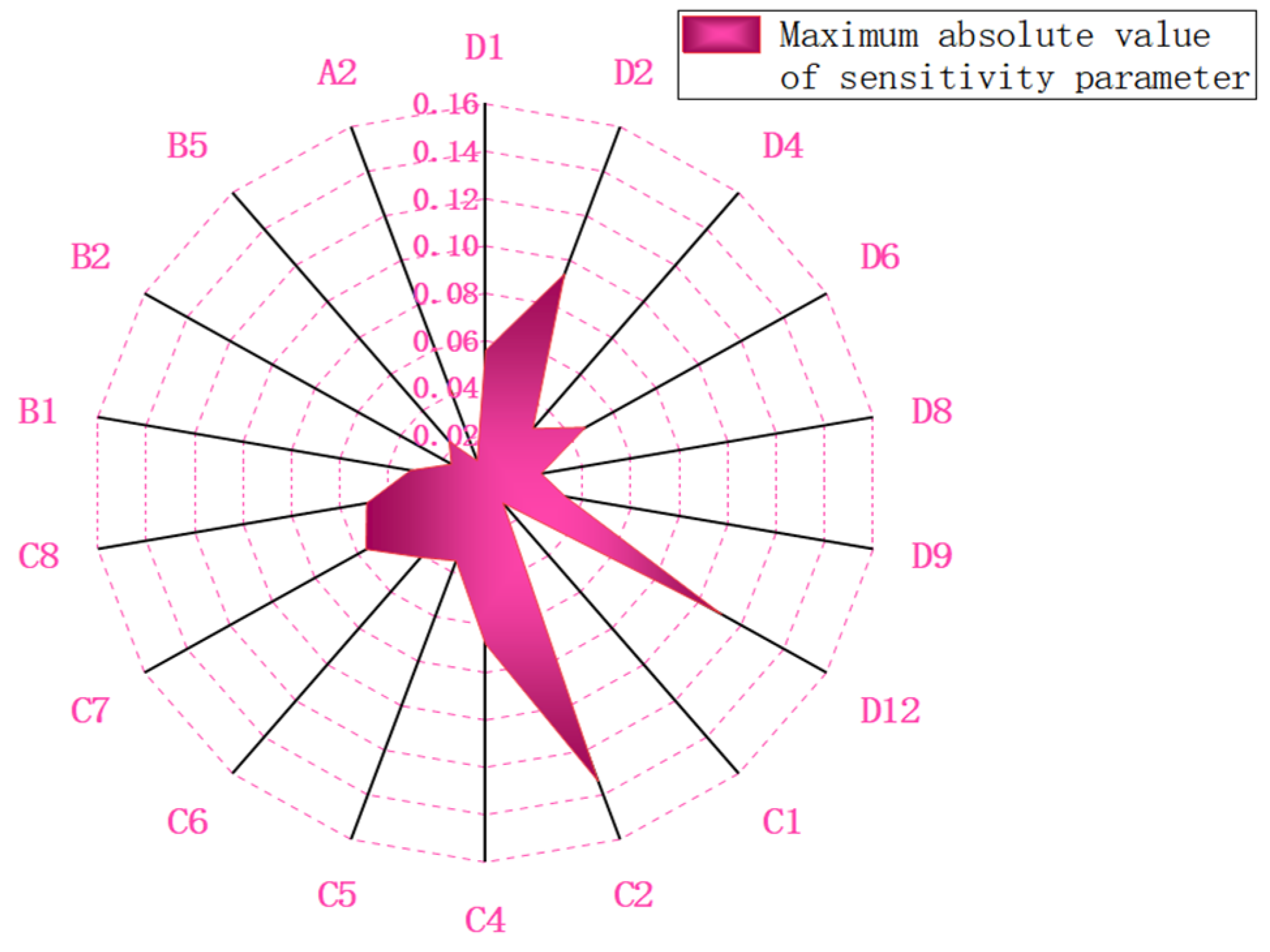

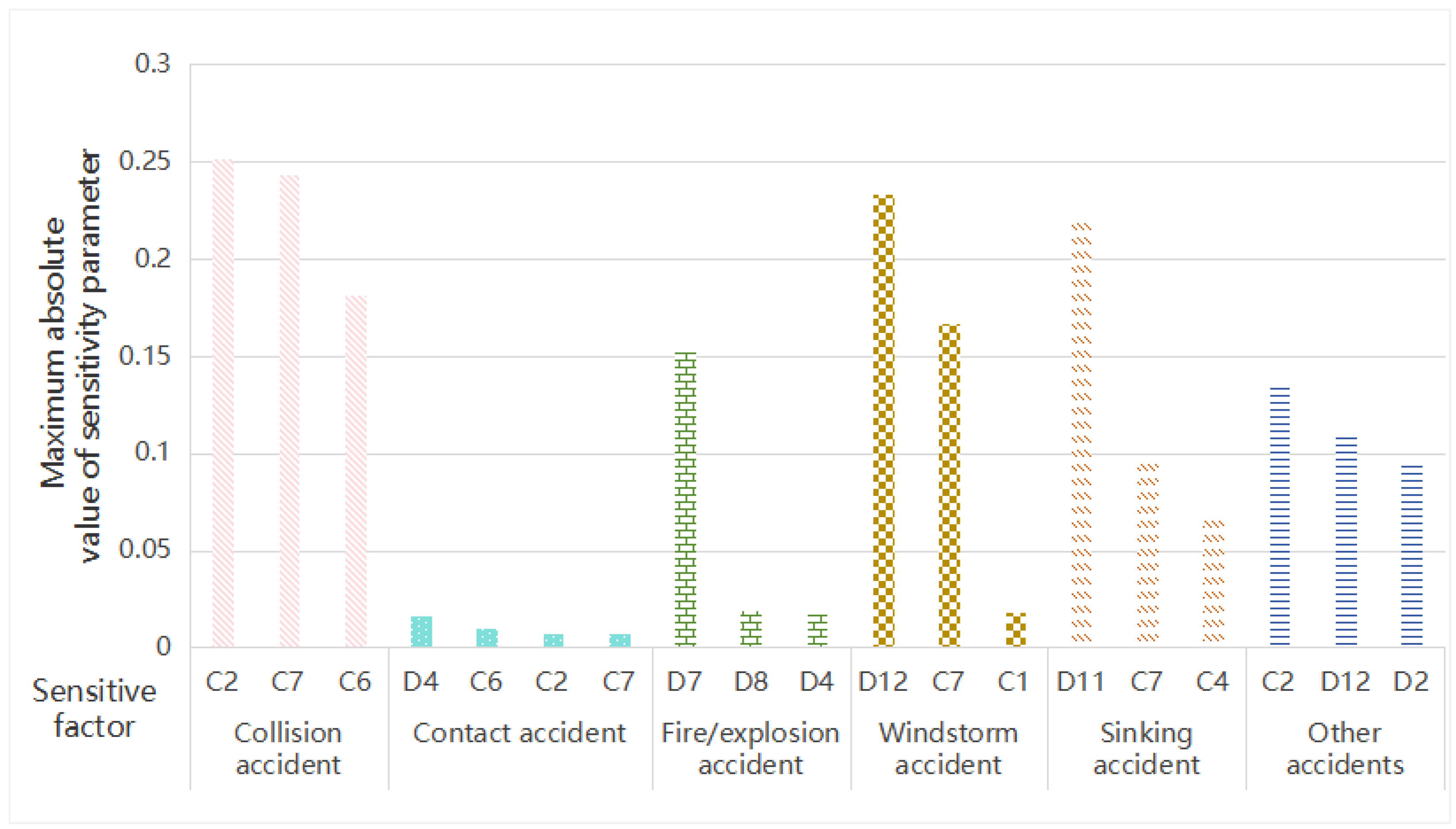

4.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Causes of Waterborne Traffic Accidents

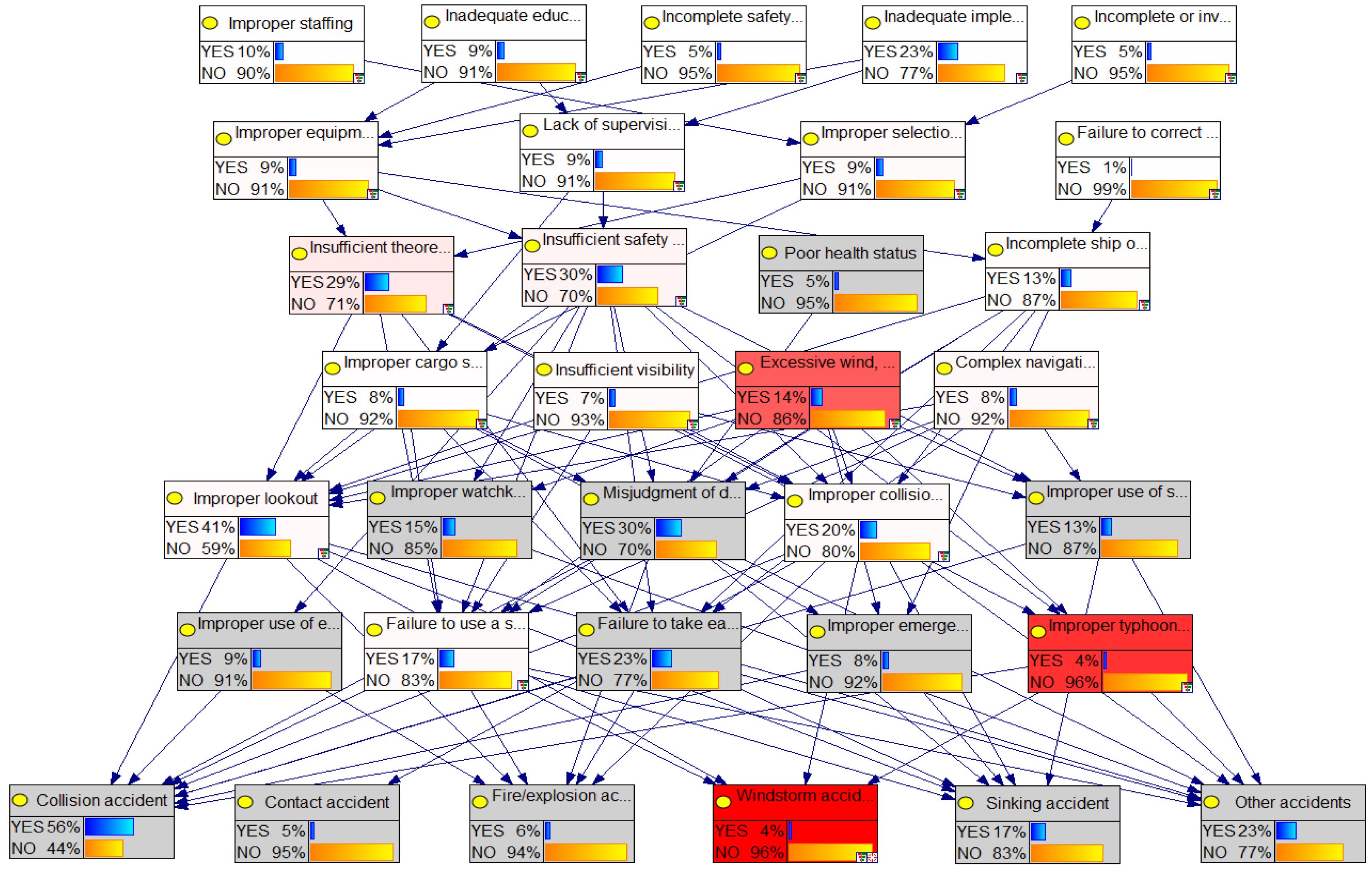

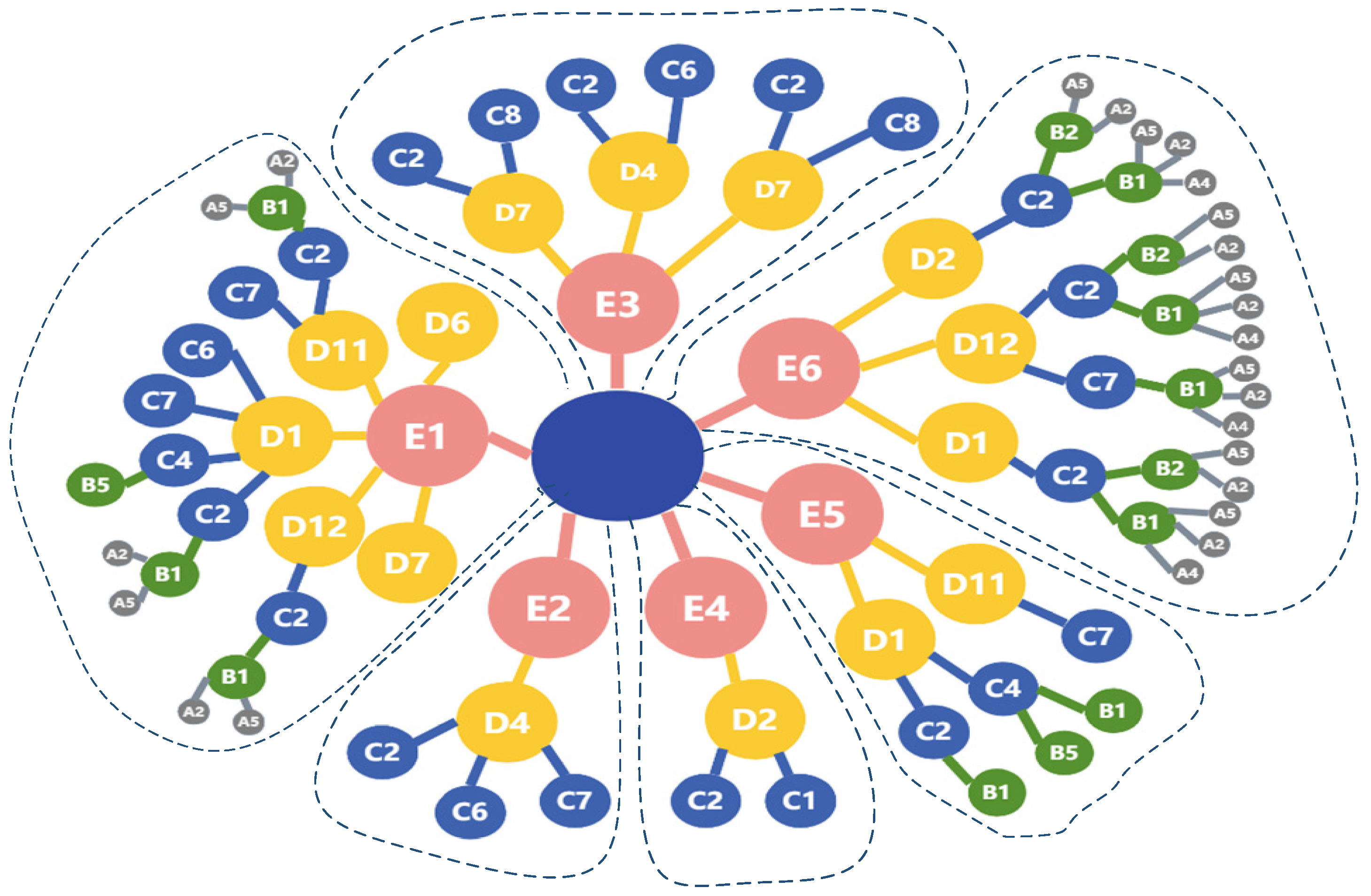

4.3. Cause Paths of Waterborne Traffic Accidents

4.4. Global Causal Chain Analysis of Waterborne Traffic Accidents

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Formela, K.; Weintrit, A.; Neumann, T. Overview of definitions of maritime safety, safety at sea, navigational safety and safety in general. International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation, 2019, 13, 285-290.

- Peng Z, Jiang Z, Chu X. et al. Spatiotemporal Distribution and Evolution Characteristics of Water Traffic Accidents in Asia since the 21st Century. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2023, 11, 2112. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Kou, L.; Ma, Q. Research on HFACS based on accident causality diagram. Open journal of safety science and technology, 2017, 7, 77-85. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Thai, V.V. Expert elicitation and Bayesian Network modeling for shipping accidents: A literature review. Safety science, 2016, 87: 53-62. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Liu Z, Wang X. et al. An analysis of factors affecting the severity of marine accidents. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 2021, 210,107513. [CrossRef]

- Liu K, Yu Q, Yuan Z. et al. A systematic analysis for maritime accidents causation in Chinese coastal waters using machine learning approaches. Ocean & Coastal Management, 2021, 213:105859. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, M.; Xiu, X. Analysis of the Causes of Water Transportation Accidents Based on Complex Network Theory . Journal of Dalian Maritime University, 2023, 49, 80-90+160.

- Wu Y, Jiang F, Yao H. et al. Analysis of Causal Factors and Risk Prediction for Inland River Ship Collision Accidents Based on Text Mining . Journal of Transport Information and Safety, 2018.36, 8-18.

- Wang H, Liu Z, Liu Z. et al. GIS-based analysis on the spatial patterns of global maritime accidents. Ocean engineering, 2022, 245: 110569.

- Kaptan M, Sarıali̇oğlu S, Uğurlu Ö. et al. The evolution of the HFACS method used in analysis of marine accidents: A review. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 2021, 86: 103225 . [CrossRef]

- Yildiz S, Uğurlu Ö, Wang J. et al. Application of the HFACS-PV approach for identification of human and organizational factors (HOFs) influencing marine accidents. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 2021, 208: 107395. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Sha, Z, Zhang J. et al. Human Factor Analysis of Ship Grounding Accidents Based on the HFACS-FCMs Model . Journal of Shandong Jiaotong University, 2024, 32, 103-109+123.

- Yıldırım, U.; Başar, E.; Uğurlu, Ö. Assessment of collisions and grounding accidents with human factors analysis and classification system (HFACS) and statistical methods. Safety Science, 2019, 119: 412-425. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Analysis and Application of Human Factors in Marine Traffic Based on the HFACS Method . Shandong Industrial Technology, 2018, (05): 216-218+238.

- Chen S, Wall A, Davies P. et al. A Human and Organizational Factors (HOFs) analysis method for marine casualties using HFACS-Maritime Accidents (HFACS-MA). Safety science, 2013, 60:105-114.

- Chauvin C, Lardjane S, Morel G. et al. Human and organizational factors in maritime accidents: Analysis of collisions at sea using the HFACS. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 2013, 59:26-37.

- Fan S, Blanco-Davis E, Yan Z. et al. Incorporation of human factors into maritime accident analysis using a data-driven Bayesian network. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 2020, 203:107070. [CrossRef]

- Antão, P.; Soares, C.G. Analysis of the influence of human errors on the occurrence of coastal ship accidents in different wave conditions using Bayesian Belief Networks. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 2019, 133: 105262. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, Z. Bayesian network modelling and analysis of accident severity in waterborne transportation: A case study in China. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 2018, 180:277-289. [CrossRef]

- Meng X, Li H, Zhang W. et al. Analyzing risk influencing factors of ship collision accidents: A data-driven Bayesian network model integrating physical knowledge. Ocean & Coastal Management, 2024, 256: 107311. [CrossRef]

- Fan S, Yang Z, Blanco-Davis E. et al. Analysis of maritime transport accidents using Bayesian networks. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part O: Journal of Risk and Reliability, 2020, 234, 439-454. [CrossRef]

- Tian Y, Qiao H, Hua L. et al. Bayesian Network Model for Maritime Ship Collisions and Its Application . Journal of Naval University of Engineering, 2023, 35, 28-33.

- Hänninen, M.; Kujala, P. The effects of causation probability on the ship collision statistics in the Gulf of Finland. Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation, 2010, 4,79-84.

- Meng X, Li H, Zhang W. et al. Analyzing ship collision accidents in China: A framework based on the NK model and Bayesian networks. Ocean Engineering, 2024, 309: 118619. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jin, G. Cause analysis of marine accidents based on HFACS and Bayesian networks[C]. International Conference on Smart Transportation and City Engineering , 2024, 13018: 1022-1030.

- Rostamabadi A, Jahangiri M, Zarei E. et al. A novel fuzzy bayesian network-HFACS (FBN-HFACS) model for analyzing human and organization factors (HOFs) in process accidents. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 2019, 132: 59-72. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wan, Z.; Chen, J. Path Analysis of the Causes of Coastal Water Transportation Accidents in China . Journal of Dalian Maritime University, 2024, 50, 76-84.

- Li Y, Cheng Z, Yi T. et al. Use of HFACS and Bayesian network for human and organizational factors analysis of ship collision accidents in the Yangtze River. Maritime Policy & Management, 2022, 49, 1169-1183. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Chen N, Wu B. et al. Human and organizational factors analysis of collision accidents between merchant ships and fishing vessels based on HFACS-BN model. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 2024, 249: 110201. [CrossRef]

- Özkan U, Serdar Y, Sean L et al. Analyzing Collision, Grounding, and Sinking Accidents Occurring in the Black Sea Utilizing HFACS and Bayesian Networks. Risk analysis: an official publication of the Society for Risk Analysis, 2020, 40,2610-2638.

| Accident Type | Accident Description | Accident Frequency |

| Collision accident | An accident in which two or more ships are directly impacted and cause damage at the same time in the same space. | 315 |

| Contact accident |

An accident in which a ship collides with structures above or below the water, such as quay walls, docks, navigation aids, bridge piers, floating facilities, or obstacles to navigation such as sunken ships, sunken objects, and wooden piles, causing damage. | 49 |

| Fire/explosion accident | A fire or explosion on a ship caused by the uncontrolled ignition source due to some reason during navigation, berthing, or operation. | 34 |

| Windstorm accident | An accident in which a ship suffers losses due to a strong storm. | 32 |

| Sinking accident |

An accident in which a ship sinks or capsizes due to its own reasons. | 135 |

| Other accidents |

An accident that does not belong to the specific categories of collision, contact, fire/explosion, windstorm, or sinking, but still results in the sinking or damage of the ship, casualties of crew members and passengers, and environmental pollution. | 191 |

| Factor Level | Num | Causal Factor | OC |

| Poor organizational management |

A1 | Improper staffing | 94 |

| A2 | Inadequate education and training | 87 | |

| A3 | Lack of communication within the team | 41 | |

| A4 | Incomplete safety management system | 46 | |

| A5 | Inadequate implementation of safety management | 224 | |

| A6 | Improper provision of chart information | 10 | |

| A7 | Incomplete or invalid ship certificates | 52 | |

| Unsafe supervision | B1 | Improper equipment allocation and maintenance | 81 |

| B2 | Lack of supervision and guidance | 76 | |

| B3 | Improper voyage planning | 74 | |

| B4 | Improper selection of navigation areas/Improper operation and management | 87 | |

| B5 | Failure to correct mistakes | 11 | |

| Preconditions for unsafe behavior |

C1 | Insufficient theoretical knowledge, work experience, skill level, and other abilities | 275 |

| C2 | Insufficient safety awareness | 285 | |

| C3 | Poor health status | 43 | |

| C4 | Incomplete ship operation, navigation performance, information, and equipment | 117 | |

| C5 | Improper cargo securing and stowage | 70 | |

| C6 | Insufficient visibility | 67 | |

| C7 | Excessive wind, waves, and currents | 135 | |

| C8 | Complex navigation environment | 79 | |

| Unsafe behavior |

D1 | Improper lookout | 393 |

| D2 | Improper watchkeeping | 141 | |

| D3 | Misjudgment of danger | 286 | |

| D4 | Improper collision avoidance actions | 183 | |

| D5 | Failure to detect collision objects early | 2 | |

| D6 | Improper use of signals | 117 | |

| D7 | Improper use of equipment | 90 | |

| D8 | Failure to use a safe speed | 150 | |

| D9 | Failure to take early action | 220 | |

| D10 | Improper location of anchorage | 5 | |

| D11 | Improper emergency measures | 73 | |

| D12 | Improper typhoon prevention measures | 35 | |

| Accident category |

E1 | Collision accident | 521 |

| E2 | Contact accident | 50 | |

| E3 | Fire/explosion accident | 34 | |

| E4 | Windstorm accident | 32 | |

| E5 | Sinking accident | 135 | |

| E6 | Other accidents | 192 |

| Accident Type | Cause Paths |

| Collision accident (E1) | A2(A5)-B1-C2-D1-E1; A2(A5)-B1-C2-D6-E1; A2(A5)-B1-C2-D7-E1; A2(A5)-B1-C2-D12-E1; B5-C4-D1-E1; B5-C4-D11; C6-D1-E1; C6-D6-E1; C7-D1-E1; C7-D6-E1; C7-D11-E1; C7-D712-E1 |

| Contact accident(E2) | C2-D4-E2; C6-D4-E2; C7-D4-E2 |

| Fire/explosion accident (E3) | C2-D4-E3; C2-D7-E3; C2-D8-E3; C6-D4-E3; C8-D7-E3; C8-D8-E3 |

| Windstorm accident (E4) | C1-D2-E4; C2-D2-E4 |

| Sinking accident (E5) | B1-C2-D1-E5; B1-C4-D1-E5; B5-C4-D1-E5; C7-D11-E5 |

| Other accidents (E6) | A2(A4)(A5)-B1-C2-D1-E6; A2(A4)(A5)-B1-C2-D2-E6; A2(A4)(A5)-B1-C2-D12-E6; A2(A4)(A5)-B1-C7-D12-E6; A2(A5)-B2-C2-D1-E6; A2(A5)-B2-C2-D2-E6; A2(A5)-B2-C2-D12-E6 |

| Accident Type | Global Causal Chain |

| Collision accident (E1) | A1-B4-C1-D1-E1 |

| Contact accident(E2) | A5-B2-C2-D1-E2 |

| Fire/explosion accident (E3) | A5-B1-C2-D7-E3 |

| Windstorm accident (E4) | C7-D12-E4 |

| Sinking accident (E5) | A1-B4-C1-D3-E5 |

| Other accidents (E6) | A1/A5-B4/B2-C1/C2-D3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).