1. Introduction

Drought is regarded as one of the most destructive natural disasters worldwide, exerting a significant impact on agricultural systems, ecological balance, and human society. As the greenhouse effect intensifies and global temperatures continue to rise, the frequency and severity of droughts are predicted to increase, resulting in a broader range of regions being affected. Drought stress has been shown to cause plant growth inhibition, which can be promoted by timely rewatering to restore plant growth [

1,

2]. The ability of a plant to swiftly revert to its pre-drought state following rehydration is a crucial factor in determining its drought resilience [

3]. Therefore, the assessment of a plant’s capacity to withstand drought stress should encompass its recovery potential. Drought tolerance in plants is defined as a comprehensive response to drought stress, which is manifested by numerous changes in external morphology, internal structure, growth, physiological characteristics, and the accumulation of bioactive components [

4]. Regarding external morphology, drought stress severely inhibited the growth and development of

Rhododendron ovatum, with obvious wilting and drying of the leaves [

5]. In terms of physiological characteristics, drought stress resulted in the accumulation of osmotic substances such as soluble sugars and soluble proteins in the leaves of

Lycium ruthenicum [

6]. At the same time, antioxidant enzyme activities in plants change to adapt to the water-deficit environment due to the surge of reactive oxygen species content inside the plant under drought stress [

7]. In addition, drought stress caused changes in hormone levels in plants, including growth hormones such as indole acetic acid (IAA) and gibberellin (GA) and the increased adversity-responsive hormone abscisic acid (ABA) [

8]. In terms of leaf anatomical characteristics, due to the sudden decrease in water content in plants, the leaf morphology and structure made changes to adapt to the environmental changes, which caused a significant reduction in the thickness of the leaf tissues [

9].

Idesia polycarpa Maxim. (

I. polycarpa), which belongs to the genus Idesia within the family Salicaceae, is a deciduous tree species. Its fruits and seeds are high in unsaturated fatty acids and thus receive the designation of the “oil reservoir in the air” [

10].

I. polycarpa is notable for its height, adaptability, rapid growth rate, and robust vitality. Its natural distribution encompasses Sichuan, Guizhou, and Hubei provinces of China, with a recent focus on its introduction to regions such as Chongqing and Shaanxi provinces, to mitigate the effects of rocky desertification. As a new woody oilseed tree species,

I. polycarpa is widely used in many fields such as landscaping, bioenergy, healthcare, beauty care, etc. It was listed as a national strategic reserve forest species in April 2020, which is of strategic importance to ensure national energy security, food and oil supply, ecological protection, and rural revitalization [

11,

12]. At present, domestic and international research on

I. polycarpa mainly focuses on seedling breeding and fruit oil analysis, while little research has been reported on the drought tolerance of

I. polycarpa seedlings.

I. polycarpa is widely distributed, and there are many varieties, the known species are ‘Exuan 1’, ‘Yuji’, ‘Chuantong’, and so on. However, due to the lack of a comprehensive drought evaluation system, it is difficult to evaluate the drought tolerance of various varieties of

I. polycarpa, which seriously restricts the promotion of

I. polycarpa to the Northwest arid areas for afforestation. In this study, the one-year-old seedlings of

I. polycarpa were taken as the test material, through the systematic study of the growth and physiological response of

I. polycarpa seedlings to drought stress, to provide a scientific basis for

I. polycarpa seedlings’ water management. It is proposed to establish a

I. polycarpa drought tolerance evaluation system, to provide a reference for the screening of

I. polycarpa drought-tolerant varieties, and to lay a practical basis for the popularization of

I. polycarpa to the Northwest arid region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Materials

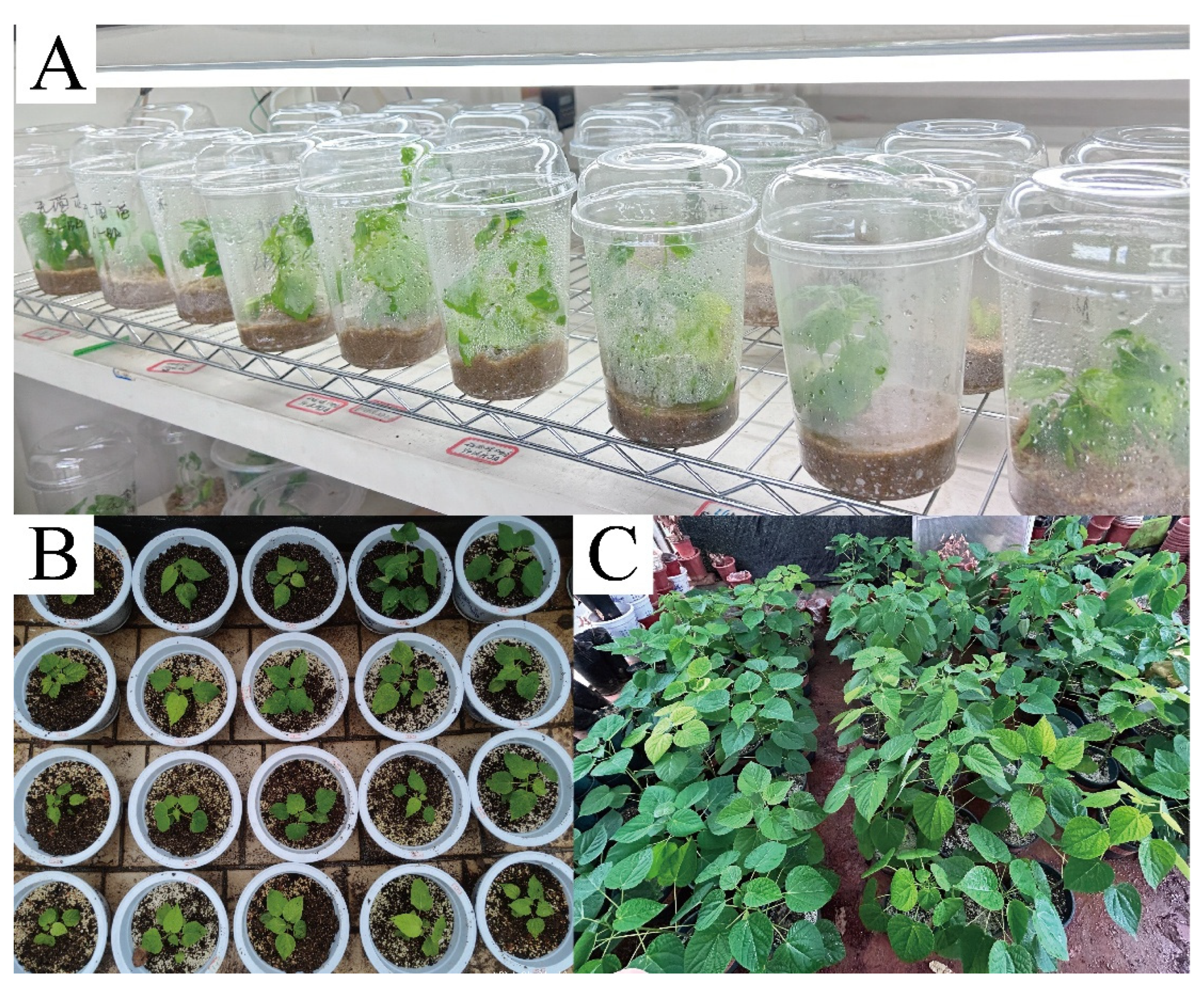

Mature

I. polycarpa fruits were collected from wild superior individual mother trees in Qishe Town, Xingyi, Guizhou Province (24°56′N, 104°47′E). After collecting the wild

I. polycarpa fruits in November 2022, the pulp of the mature fruits was crushed and continuously kneaded to obtain the seeds. The floating impurities and poor-quality seeds were eliminated through clean water. Then, the plump seeds were air-dried in a cool, well-ventilated place for storage. In January 2023, a large number of high-quality tissue culture seedlings were obtained through the aseptic germination of the collected and stored

I. polycarpa seeds. In March, the seedlings were transplanted into transparent plastic cups for hardening (

Figure 1A). In early April,

I. polycarpa seedlings were transplanted into 20 × 23 cm (height × diameter) polypropylene containers with a soil substrate composed of peat soil, perlite, and vermiculite (2:1:1) for continued growth (

Figure 1B). In July, healthy one-year-old

I.

polycarpa seedlings with uniform height were selected and moved under a rain shelter that did not affect light or ventilation for acclimatization (

Figure 1C). During this recovery phase, normal watering and maintenance practices were maintained.

2.2. Design of the Experiment

Three different water treatments were established based on soil relative water content (RWC) to simulate drought stress: control (CK, RWC = 70 ± 5%), moderate drought (T1, RWC = 40 ± 5%), and severe drought (T2, RWC = 20 ± 5%). The drought stress treatments lasted for 21 days. After the drought stress period, all drought-treated groups were rewatered to the control RWC level (70 ± 5%), forming the moderate drought rewatering group (T3) and the severe drought rewatering group (T4). Each treatment group, including the control, contained 20 plants, totaling 60 potted I. polycarpa seedlings.

Drought stress was simulated using a pot-based water control method. Irrigation was stopped on August 10, allowing soil moisture to decrease through natural evaporation until it reached the target RWC for each treatment group. This point was designated as day 0 of drought stress. The drought stress period lasted for 21 days. During this period, water lost through transpiration was replenished every 4 hours between 8:00 and 19:00. A soil moisture meter (SANKU SK-100, Japan) was used to measure soil water content before and after each watering. Following the principle of frequent and small water additions, the probe of the moisture meter was inserted to a depth of 10 cm to ensure that the soil RWC remained within the specified range for each treatment.

On day 21 of the drought stress treatment, plants in all drought treatment groups were rewatered to the control RWC level (70 ± 5%), and the rewatering treatment lasted for 14 days. Throughout the experiment, seedlings were kept in a rainproof net house to prevent any external water input. To reduce water loss from soil surface evaporation, plastic film was used to cover the soil surface and maintain soil moisture.

2.3. Sample Collection

Measurements of growth, biomass, and photosynthetic physiological parameters were conducted on day 21 of drought stress and day 14 after rewatering. Sample leaves were also collected during each of these times, between 08:00 and 10:00 a.m. For each treatment, 8–10 healthy leaves were collected, and labeled with the treatment name and sampling time. A portion of the samples was placed in resealable bags for the determination of leaf relative water content, relative electrical conductivity, and chlorophyll content. Another portion was wrapped in aluminum foil, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and brought back to the laboratory for storage in an ultra-low temperature freezer (–80 °C). These samples were used for measuring the contents of osmotic adjustment substances, antioxidant enzyme activities, and endogenous hormone levels. Each treatment included three biological replicates for sampling.

2.4. Measurement of Growth Indexes

Before the initiation of the stress treatment, after the stress treatment, and following rewatering, plant height, ground diameter, and crown were measured to evaluate the changes in plant height growth (ΔH), diameter growth (ΔD), and crown growth under each treatment condition.

Biomass was determined using the whole-plant harvesting method, which was conducted at the end of the stress treatment and after the rewatering process. Upon completion of the treatments, the potting soil was loosened by rinsing with running water. The seedlings were then extracted, and any adhering soil was washed away. After removing residual moisture, the fresh weights of the aboveground parts (including stems, branches, and leaves) and the belowground parts (roots) of the seedlings were measured separately. The fresh weight per plant and the root-crown ratio (the ratio of belowground fresh weight to aboveground fresh weight) were subsequently calculated.

2.5. Photosynthetic Characteristics and Photosynthetic Pigment Indexes

Photosynthetic parameters including net photosynthetic rate (P

n), stomatal conductance (G

s), intercellular CO₂ concentration (C

i), and transpiration rate (T

r) were recorded employing a portable photosynthesis measurement system (LI-6400, LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) according to a set light level of 1,200 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹. The level of chlorophyll was obtained utilizing the 95% ethanol-acetone extraction technique [

13].

2.6. Physiological and Biochemical Indexes

The leaf relative water content (LRWC) was determined using the drying method [

14]. Fresh leaves were collected and their fresh weight was measured. The leaves were then immersed in distilled water for 24 hours to achieve saturated fresh weight. Subsequently, the leaves were placed in an oven and dried at 80°C for 8 hours to obtain the dry weight. The relative water content of the leaves was calculated as (fresh weight − dry weight) / (saturated fresh weight−dry weight) × 100%.

The leaves were cut into strips of appropriate length (avoiding the midrib), and three fresh samples, each weighing 0.1g, were quickly weighed and placed into graduated test tubes containing 10 ml of deionized water. The tubes were then stopped with glass caps and left to soak at room temperature for 12 hours. The conductivity of the leachate (R1) was measured using a conductivity meter. Subsequently, the samples were heated in a boiling water bath for 30 minutes, cooled to room temperature, and thoroughly mixed before the conductivity of the leachate (R2) was measured again. Leaf relative electrical conductivity (REC) was calculated as R1/R2 × 100% [

14].

Malondialdehyde (MDA) content was assessed using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) method. Proline content was quantified using the acidic ninhydrin method. Betaine content was determined via the Reinecke salt method. The anthrone-sulfuric acid method was used to determine soluble sugar (SS) content. Soluble protein (SP) content was assessed via the Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 method (Bradford assay). Peroxidase (POD) activity was determined using the guaiacol method. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured using the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) photoreduction method. Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity was assayed using the ascorbate oxidation method. Catalase (CAT) activity was determined using the ultraviolet absorption method [

14].

ELISA was used to quantify endogenous GA, IAA, ABA, and SA levels [

15]. Fresh

I. polycarpa leaves were homogenized in an extraction buffer and centrifuged to obtain the supernatant. Samples were added to antibody-coated ELISA plates, followed by incubation with specific antibodies and enzyme-labeled secondary antibodies. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm, and hormone concentrations were determined using a standard curve. The ELISA kits used were purchased from Ruixin Biotech Co., Ltd.

2.7. Root System Indexes and Leaf Anatomy

After the drought stress test was finished and the plants were rewatered, the entire plant was gently uprooted and the root systems were cleaned with flowing water to remove any dirt. The roots were then dried, and a root scanner was utilized for calculating distinctive root structure metrics including total root length, root surface area, root volume, and the number of root tips.

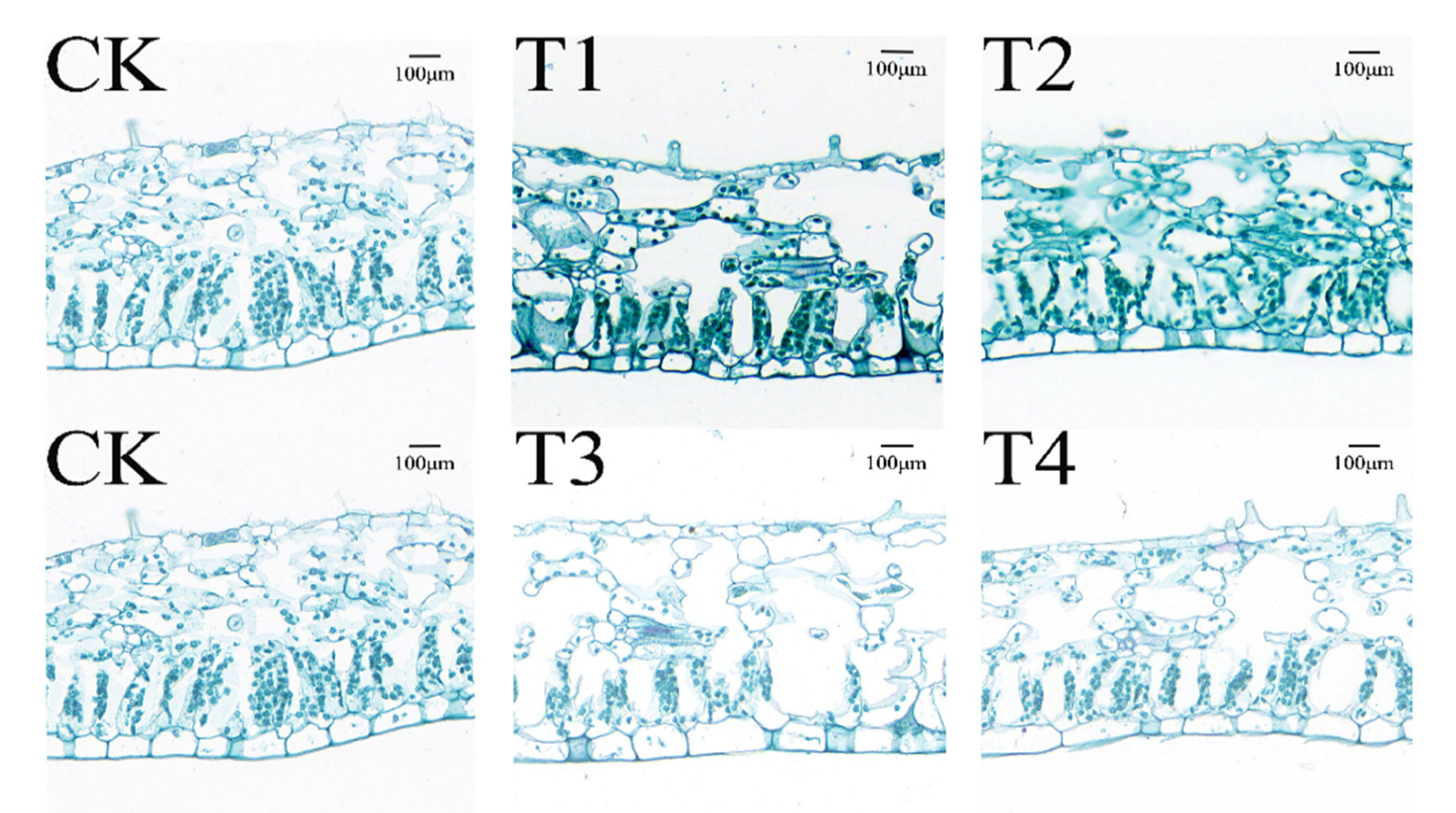

Leaf anatomy: Samples were collected to prepare paraffin sections, and the epidermal structure of the leaf was observed under a microscope to measure leaf thickness, epidermal thickness, thickness of fenestrated tissue, thickness of water-storage tissue, and vascular bundle area.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data collection and preliminary processing were all carried out utilizing Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The experimental data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA in SPSS 23.0 (IBM, New York, NY, USA), followed by Duncan’s test to assess the significance of observed differences. Graphs were generated according to Origin 2021 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA), whereas plates were created with Adobe Photoshop 2021 (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA).

4. Discussion

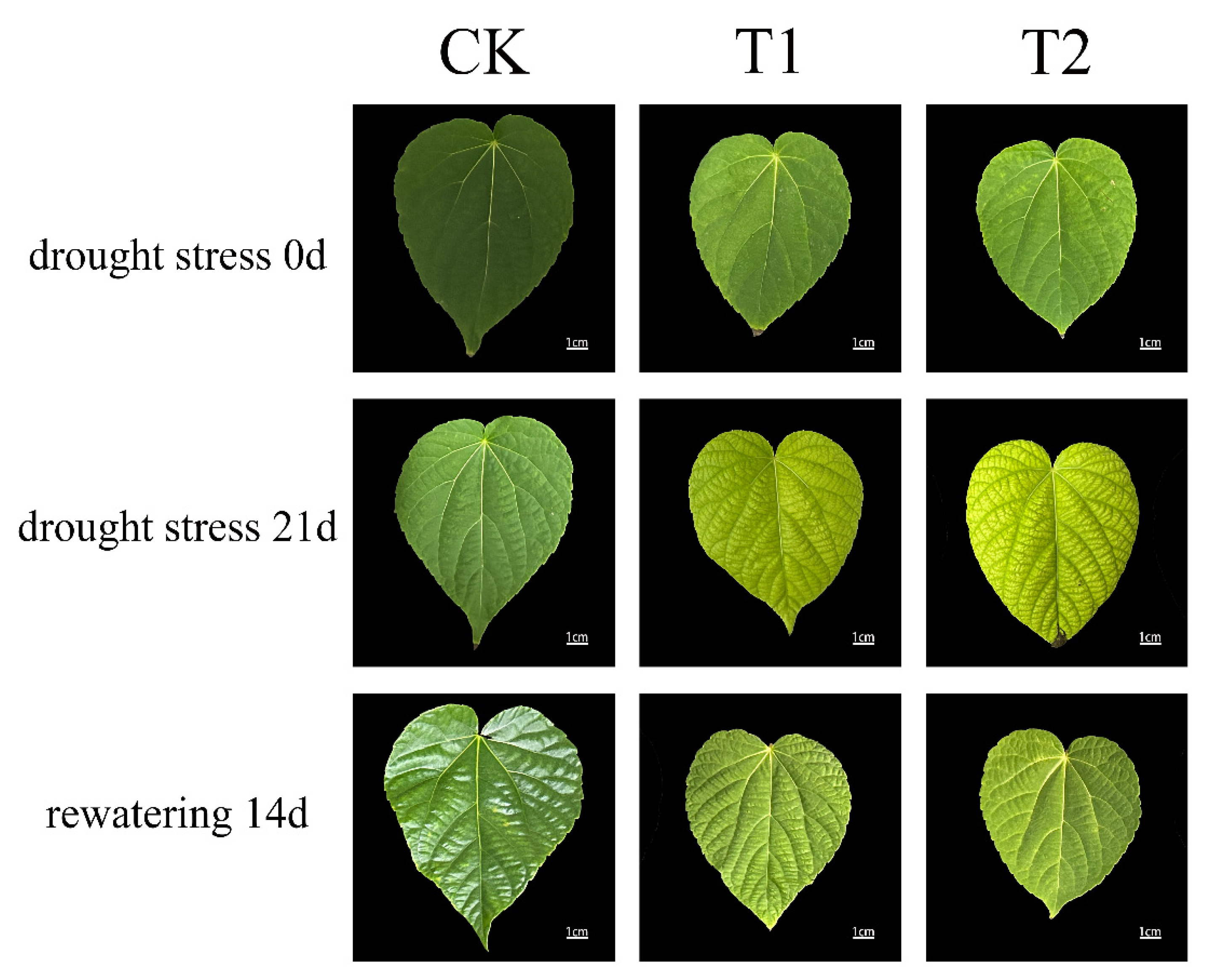

Drought stress has widespread and profound effects on plant growth and development, particularly under water-deficient conditions, where cell differentiation and expansion are inhibited, ultimately affecting overall plant growth and development [

16]. The most visible effects of drought stress are changes in leaf morphology, such as wilting, yellowing, and necrosis at the leaf tips and margins. In this study,

I. polycarpa seedlings exhibited leaf yellowing and necrosis under drought conditions, indicating significant growth impairment. Similar responses have been observed in

Camellia oleifera [

17] and

Delphinium grandiflorum [

18]. After rewatering, these stress symptoms were alleviated, but the leaf phenotype remained distinct from non-stressed plants.

Changes in leaf anatomical structure further reflected the impact of drought stress. The palisade tissue, which plays a central role in photosynthesis, directly affects photosynthetic efficiency and light tolerance [

19]. Our results showed that drought stress significantly reduced the thickness of leaf tissues in

I. polycarpa, indicating a restriction in growth due to water deficiency. Notably, the upper epidermal thickness of

I. polycarpa leaves significantly decreased by 39.51% and 34.97% under moderate and severe drought conditions, respectively, compared to the control, demonstrating a remarkable reduction. After rewatering, leaf structure partially recovered under moderate drought conditions, whereas recovery was notably limited under severe drought, suggesting that rewatering has a constrained restorative effect on leaf structure.

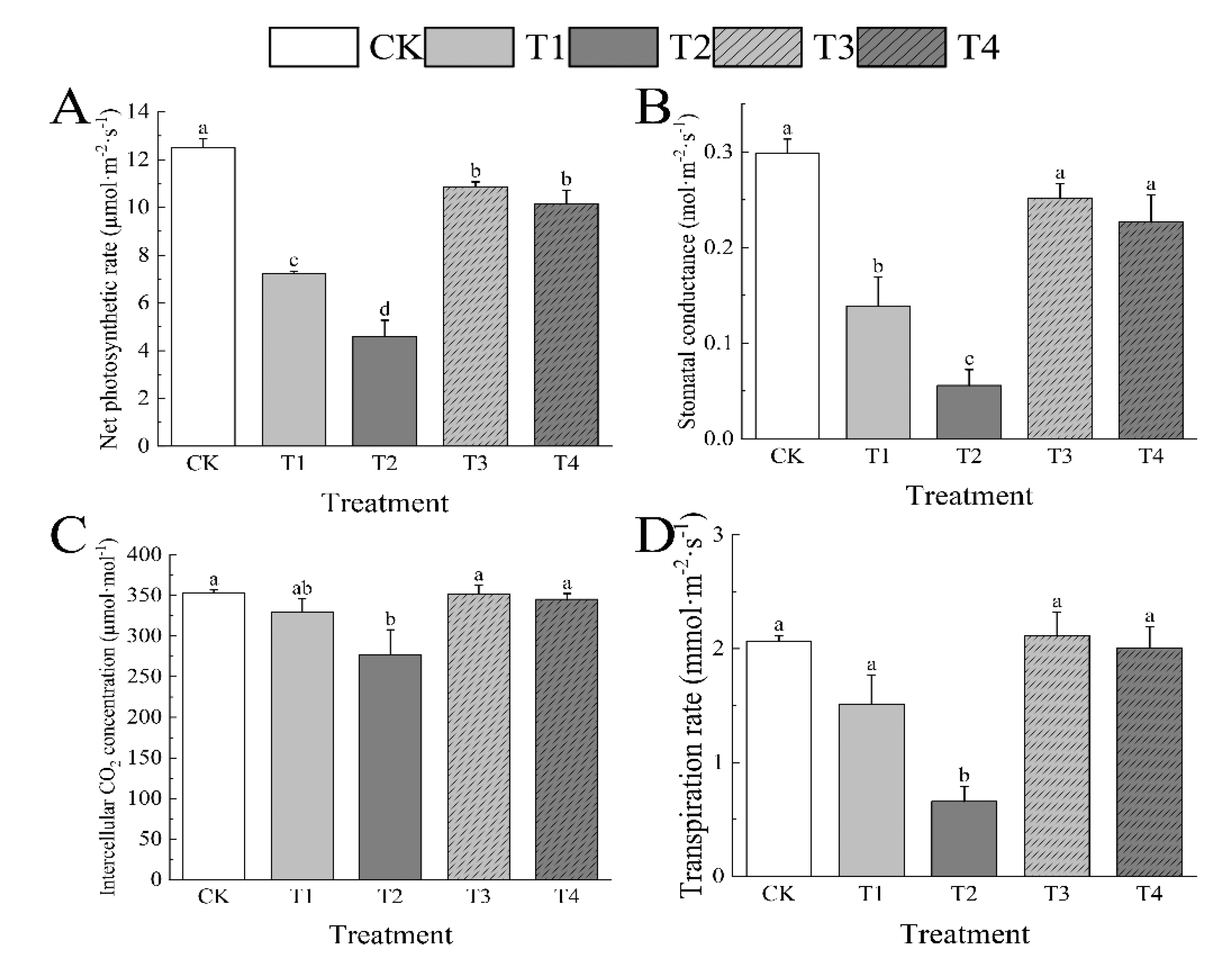

Stomata serve as the primary channels for gas exchange in plants [

20]. Under drought stress, Gs and Ci declined, directly limiting Pn. In this study, the decrease in Gs and Ci suggested that Pn limitation was mainly driven by stomatal factors. Additionally, Tr decreased, indicating that

I. polycarpa adapted to drought by reducing water loss. After rewatering, gas exchange parameters partially recovered, consistent with findings in palm species following drought stress relief [

21]. Drought stress also significantly inhibited chlorophyll synthesis and accelerated its degradation [

22]. In this study, chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b contents in

I. polycarpa seedlings declined significantly under drought conditions but increased after rewatering, suggesting that resuming normal water supply mitigates drought-induced damage to the photosynthetic system.

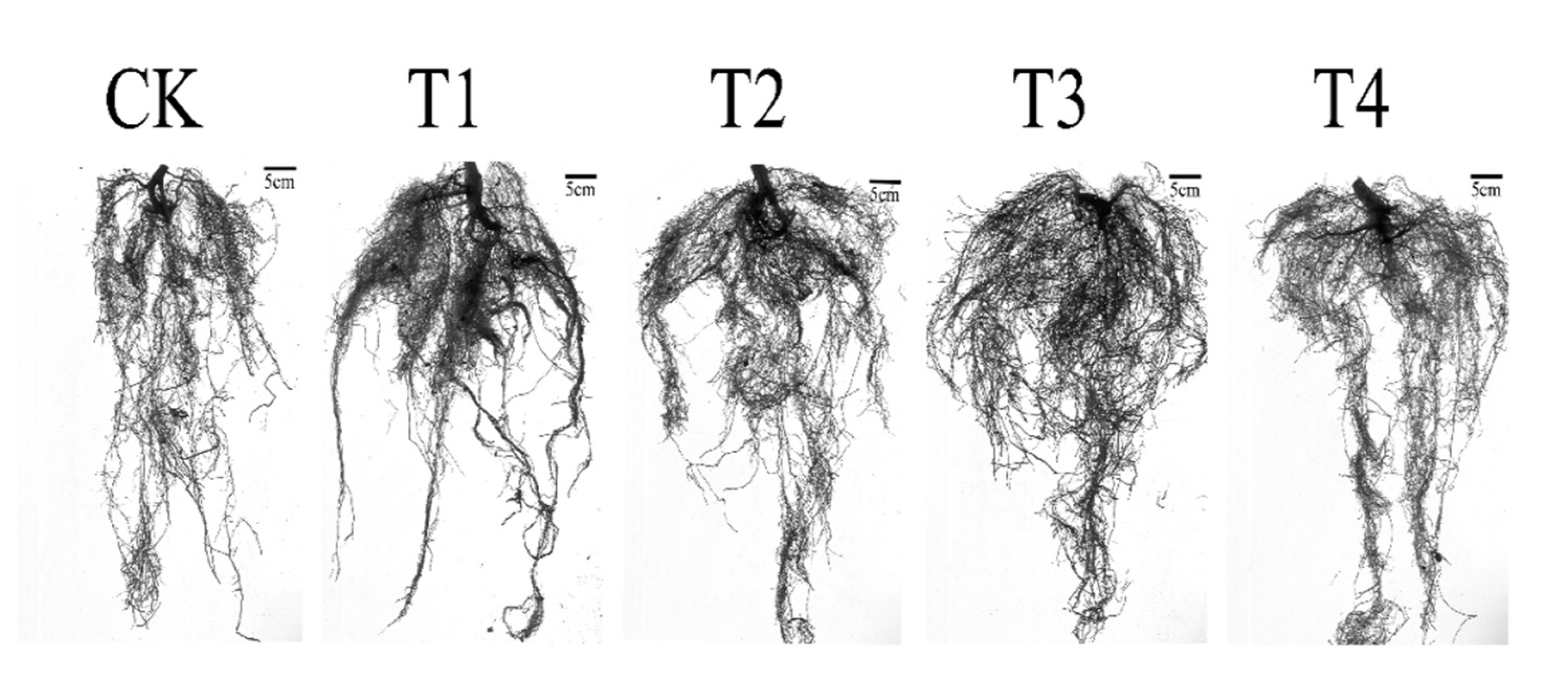

The root system, which directly interacts with the soil, is highly sensitive to water availability [

23]. Under drought stress,

I. polycarpa exhibited an increase in total root length and root tips number, indicating an adaptive strategy to access deeper soil water and enhance drought tolerance. After rewatering, compensatory root growth occurred, suggesting that

I. polycarpa possesses a certain degree of post-drought recovery capability.

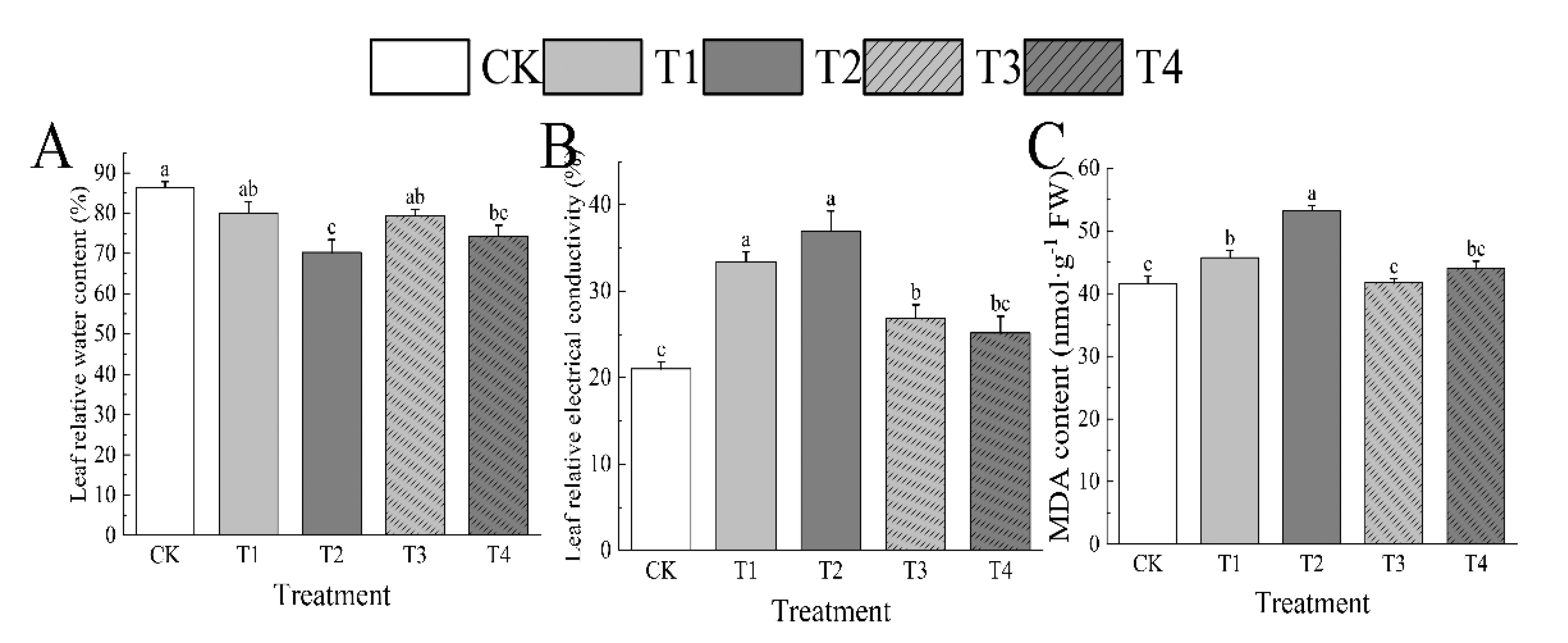

Relative water content (RWC) is a key indicator of plant drought tolerance [

24]. In this study, RWC decreased progressively with increasing drought severity, while relative conductivity and MDA content increased significantly, indicating severe cellular membrane damage. After rewatering, RWC recovered well under moderate drought conditions, demonstrating the resilience of

I. polycarpa to mild drought stress.

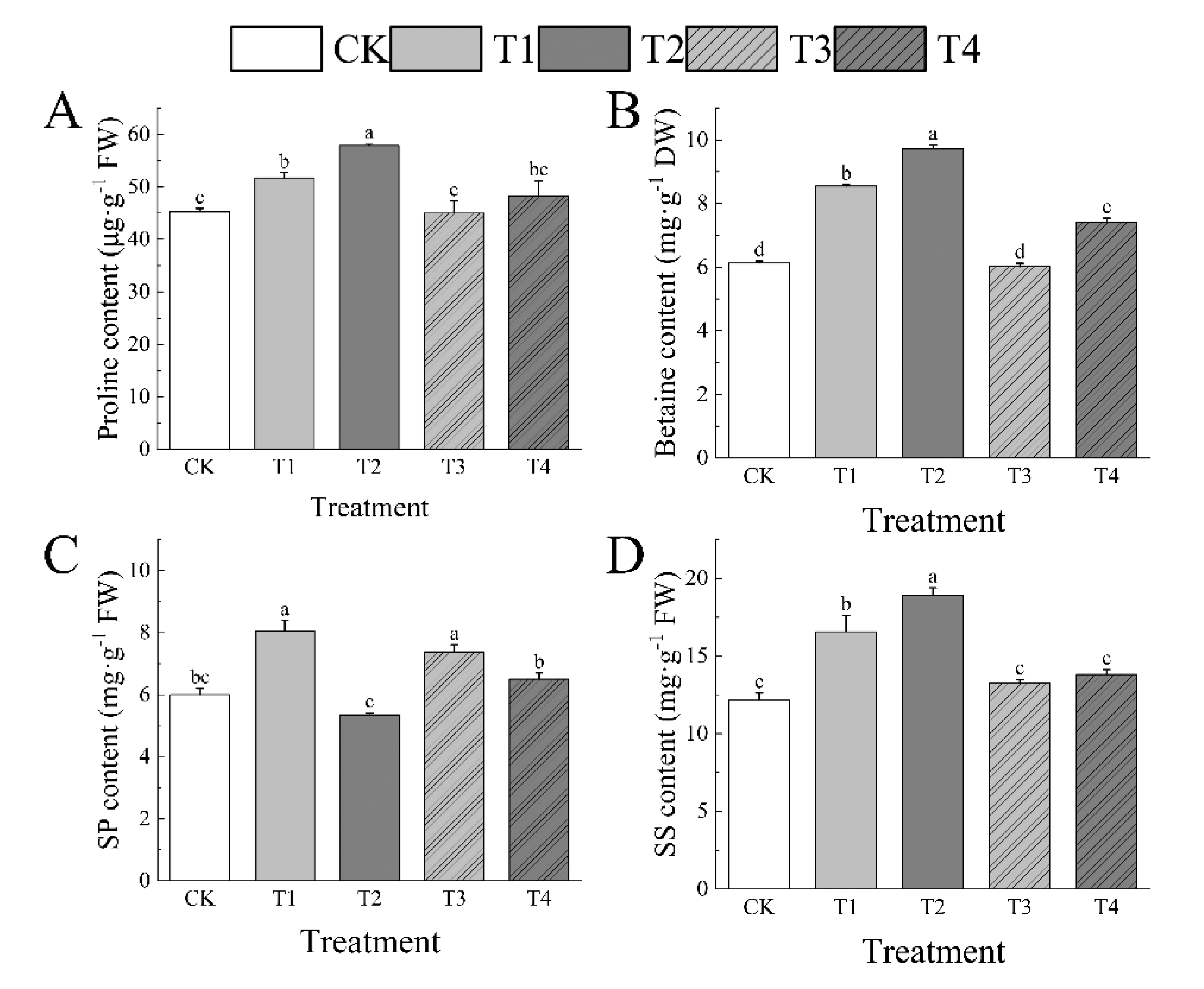

Under drought stress, the contents of proline, betaine, and SP in

I. polycarpa leaves significantly increased, while SP content peaked under moderate drought and then declined. After rewatering, these osmotic regulators partially recovered, indicating a certain degree of post-drought recovery ability. This response may be attributed to the plant’s regulation of intracellular solute concentrations to maintain cell turgor and water balance. Proline and betaine not only reduce cellular osmotic potential but also stabilize proteins and membrane structures, thereby mitigating drought-induced damage. Meanwhile, soluble sugars provide energy and carbon skeletons while undergoing osmotic adjustment [

25].

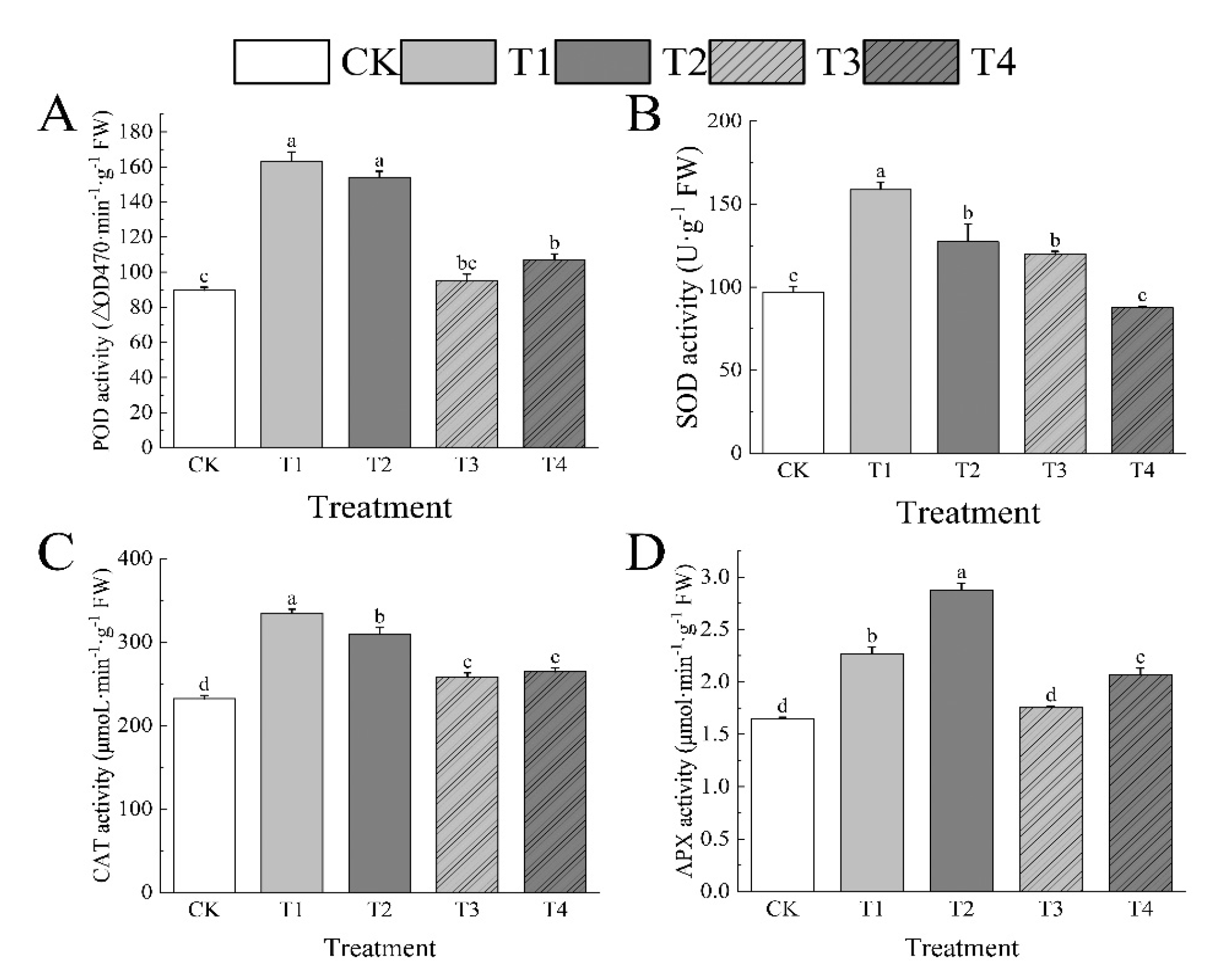

Additionally, drought stress significantly enhanced the activity of antioxidant enzymes (POD, SOD, CAT, and APX) to mitigate oxidative damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

26,

27]. After rewatering, enzyme activity declined, indicating a reduction in oxidative stress. SOD converts superoxide radicals into H₂O₂, which is further decomposed by POD, CAT, and APX, thereby limiting ROS accumulation [

28]. This mechanism plays a crucial role in protecting cell membranes and biomolecules such as proteins and DNA, ultimately improving drought tolerance.

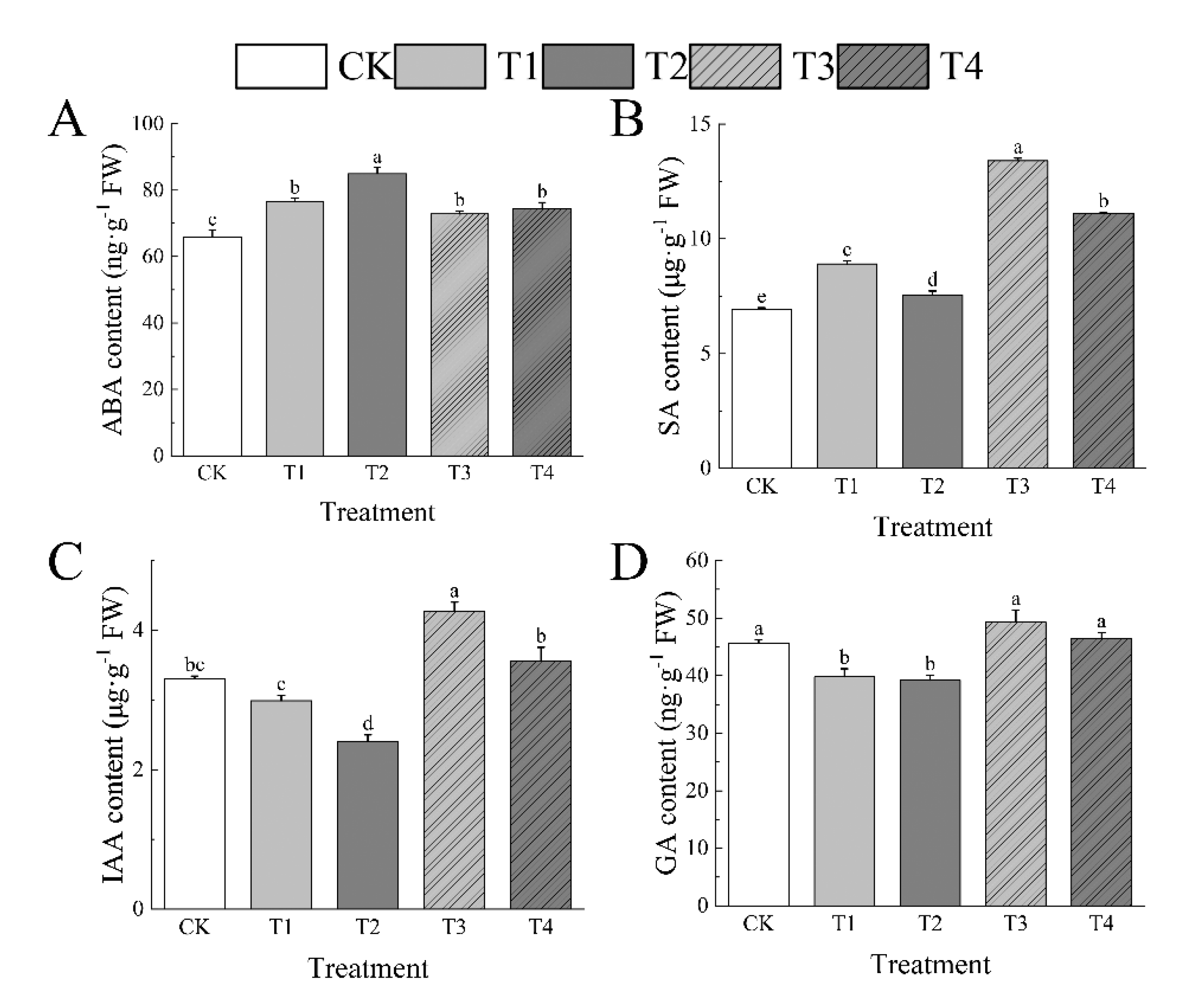

Endogenous hormones are vital in plant drought responses [

29]. This study found that drought reduced GA and IAA levels, inhibiting growth to conserve water. Upon rehydration, both hormones recovered and exceeded control levels, indicating compensatory growth, likely through hormone balance regulation. ABA and SA increased significantly under drought stress. ABA induced stomatal closure to reduce transpiration, while SA likely enhanced stress tolerance and damage repair [

30]. Rehydration led to ABA decline and stomatal reopening. Elevated SA levels suggest that

I. polycarpa enhances drought resistance and recovery via SA-mediated signaling.

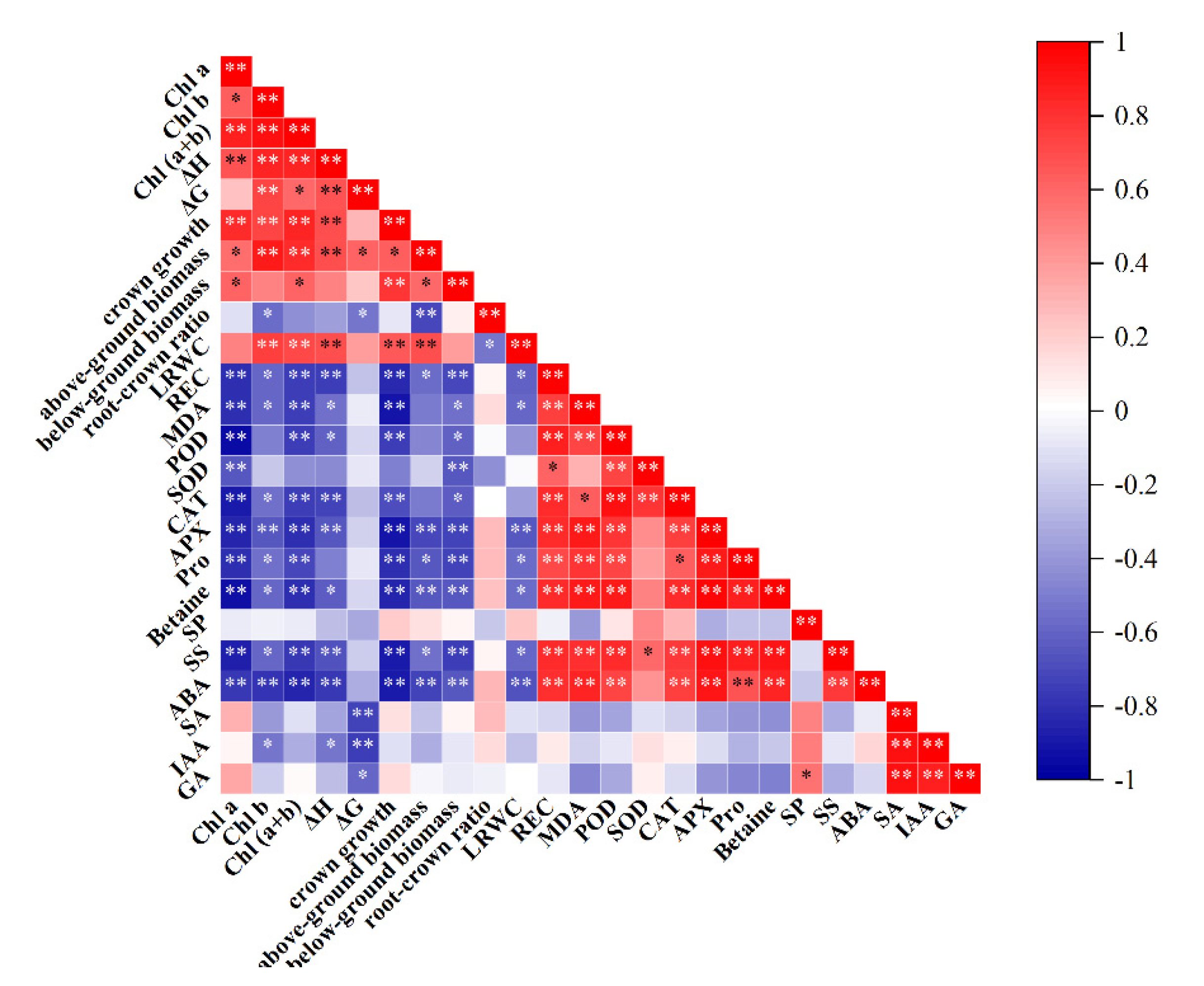

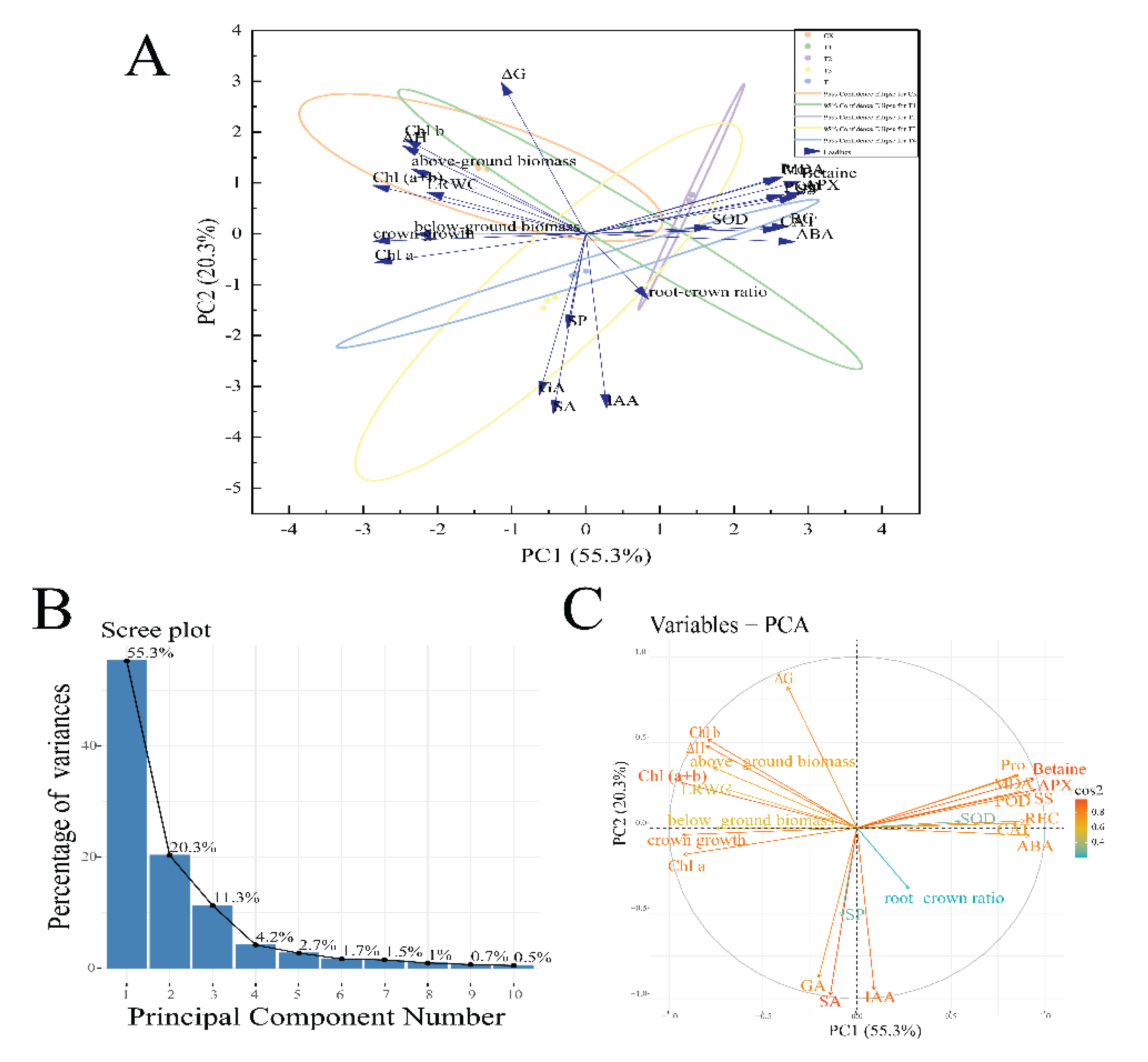

Plants respond to drought stress through various growth and physiological changes. Therefore, assessing drought tolerance requires a comprehensive evaluation of multiple growth and physiological parameters. In this study, correlation analysis revealed significant relationships (p < 0.05) among 18 growth and physiological indices. However, the high correlation between variables may lead to redundant information extraction. To address this issue, principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to reduce data dimensionality while retaining essential information, effectively mitigating redundancy [

31]. In PCA, the cos² value serves as a key metric for assessing a variable’s contribution to the principal components. By analyzing cos² values, variables with high explanatory power can be identified, aiding in data interpretation, key variable selection, and subsequent analysis. In drought tolerance studies, cos² values help determine which growth and physiological indices are most representative of drought resistance. This study found that betaine, ascorbate peroxidase (APX), salicylic acid (SA), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), abscisic acid (ABA), total chlorophyll (Chl(a+b)), chlorophyll a (Chla), and crown growth exhibited high cos² values in the first two principal components. These results suggest that these indices have strong explanatory power and can serve as key indicators for evaluating the drought tolerance of

I. polycarpa.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xiaoyu Lu and Lingli Wu; methodology, Xiaoyu Lu; software, Xiaoyu Lu; validation, Xiaoyu Lu, Yian Yin and Zhangtai Niu; formal analysis, Xiaoyu Lu; investigation, Lingli Wu; resources, Xiaoyu Lu; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Xiaoyu Lu; writing—review and editing, Xiaoyu Lu; visualization, Shucheng Zhang; supervision, Lingli Wu; project administration, Chan Chen; funding acquisition, Maolin Yang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

The experimental materials used in this study. (A) Transplant the tissue-cultured seedlings of I. polycarpa into transparent plastic cups for acclimatization. (B) Transplant I. polycarpa seedlings into pots for continued growth. (C) Healthy one-year-old I. polycarpa seedlings with uniform height were selected and moved under a rain shelter that did not affect light or ventilation for acclimatization.

Figure 1.

The experimental materials used in this study. (A) Transplant the tissue-cultured seedlings of I. polycarpa into transparent plastic cups for acclimatization. (B) Transplant I. polycarpa seedlings into pots for continued growth. (C) Healthy one-year-old I. polycarpa seedlings with uniform height were selected and moved under a rain shelter that did not affect light or ventilation for acclimatization.

Figure 2.

Effects of drought stress on leaf phenotypic characteristics of I. polycarpa seedlings. CK: Control; T1: Moderate drought; T2: Severe drought.

Figure 2.

Effects of drought stress on leaf phenotypic characteristics of I. polycarpa seedlings. CK: Control; T1: Moderate drought; T2: Severe drought.

Figure 3.

Scan of I. polycarpa seedlings root system.

Figure 3.

Scan of I. polycarpa seedlings root system.

Figure 4.

Effects of drought stress on the net photosynthetic rate(A), stomatal conductance(B), intercellular CO2 concentration(C), and transpiration rate(D) of I. polycarpa. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of drought stress on the net photosynthetic rate(A), stomatal conductance(B), intercellular CO2 concentration(C), and transpiration rate(D) of I. polycarpa. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of drought stress on leaf relative water content (A), leaf relative electrical conductivity (B), and MDA content(C) of leaves of I. polycarpa. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of drought stress on leaf relative water content (A), leaf relative electrical conductivity (B), and MDA content(C) of leaves of I. polycarpa. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Effects of drought stress on POD activity (A), SOD activity (B), APX activity (C), and CAT activity (D) of leaves of I. polycarpa. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Effects of drought stress on POD activity (A), SOD activity (B), APX activity (C), and CAT activity (D) of leaves of I. polycarpa. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Effects of drought stress on proline content (A), betaine content (B), SP content (C), and SS content (D) of leaves of I. polycarpa. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Effects of drought stress on proline content (A), betaine content (B), SP content (C), and SS content (D) of leaves of I. polycarpa. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Effects of drought stress on ABA content (A), SA content (B), IAA content (C), and GA content (D) of leaves of I. polycarpa. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Effects of drought stress on ABA content (A), SA content (B), IAA content (C), and GA content (D) of leaves of I. polycarpa. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Figure 9.

Leaf anatomy of I. polycarpa seedlings leaves.

Figure 9.

Leaf anatomy of I. polycarpa seedlings leaves.

Figure 10.

Pearson’s correlation matrix analysis of key growth and physiological indices of I. polycarpa seedings; * indicates significant correlation(p≤0.05); ** indicates extremely significant correlation(p≤0.01).

Figure 10.

Pearson’s correlation matrix analysis of key growth and physiological indices of I. polycarpa seedings; * indicates significant correlation(p≤0.05); ** indicates extremely significant correlation(p≤0.01).

Figure 11.

Principal component analysis of key indicators of growth and physiology of I. polycarpa seedlings. A: PCA 2D Biplot; B: Scree Plot; C: Biplot with cos2 Values; high cos² values are represented by red arrows, intermediate cos² values are represented by yellow arrows, low cos² values are represented by blue arrows.

Figure 11.

Principal component analysis of key indicators of growth and physiology of I. polycarpa seedlings. A: PCA 2D Biplot; B: Scree Plot; C: Biplot with cos2 Values; high cos² values are represented by red arrows, intermediate cos² values are represented by yellow arrows, low cos² values are represented by blue arrows.

Table 1.

Effects of drought stress on chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll contents of I. polycarpa. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Effects of drought stress on chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll contents of I. polycarpa. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

| Treatment |

Chlorophyll a content

(mg·g−1 FW)

|

Chlorophyllb content

(mg·g−1 FW)

|

Total chlorophyll content

(mg·g−1 FW)

|

| CK |

1.882±0.001a |

2.161±0.082a |

4.042±0.082a |

| T1 |

0.948±0.004c |

1.044±0.094b |

1.992±0.091c |

| T2 |

0.907±0.017c |

0.526±0.038d |

1.433±0.055d |

| T3 |

1.741±0.086a |

0.956±0.139bc |

2.696±0.224b |

| T4 |

1.499±0.121b |

0.688±0.104cd |

2.188±0.225bc |

Table 2.

Effects of drought stress on the growth of I. polycarpa seedlings. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Effects of drought stress on the growth of I. polycarpa seedlings. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

| Treatment |

ΔH(cm) |

ΔG(mm) |

crown growth(cm) |

above-ground biomass(g) |

below-ground biomass(g) |

root-crown ratio |

| CK |

3.90±0.15a |

2.66±0.29a |

6.82±1.00a |

51.80±5.72a |

43.82±1.66a |

0.87±0.10c |

| T1 |

0.83±0.41b |

1.18±0.26bc |

−0.92±0.16bc |

33.51±1.61bc |

33.07±1.44b |

0.99±0.03bc |

| T2 |

0.73±0.18b |

1.42±0.06b |

−9.02±0.27d |

21.24±1.98c |

26.42±2.32b |

1.25±0.06b |

| T3 |

1.47±0.44b |

0.77±0.06cd |

0.92±0.19c |

34.42±3.86b |

34.19±2.19b |

1.01±0.11bc |

| T4 |

1.13±0.22b |

0.47±0.05d |

2.56±0.80b |

24.64±4.16bc |

42.69±3.85a |

1.79±0.16a |

Table 3.

Effects of drought stress on root growth of I. polycarpa seedlings. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Effects of drought stress on root growth of I. polycarpa seedlings. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

| Treatment |

Root Length

(cm)

|

Root Surf area

(cm2)

|

Root Volume

(cm3)

|

Root Tips |

| CK |

1 923.44±14.41bc |

955.24±20.94a |

39.07±2.11a |

1 119.0±48.5c |

| T1 |

2 873.54±228.60a |

946.86±26.38a |

22.53±0.85c |

1 613.7±113.8ab |

| T2 |

2 165.50±71.36b |

645.79±24.28c |

14.91±1.92d |

1 685.7±29.8ab |

| T3 |

1 764.77±123.61bc |

827.66±50.09b |

33.45±0.91ab |

1 877.7±141.1a |

| T4 |

1 664.69±81.47c |

863.47±15.04ab |

31.85±2.49b |

1 408.0±47.1bc |

Table 4.

Parameters of I. polycarpa leaf structure TU: Upper epidermal thickness; TL: Lower epidermal thickness; TP: Palisade tissue thickness; TS: Spongy tissue thickness; LT: Leaf thickness. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Parameters of I. polycarpa leaf structure TU: Upper epidermal thickness; TL: Lower epidermal thickness; TP: Palisade tissue thickness; TS: Spongy tissue thickness; LT: Leaf thickness. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between each treatment (p < 0.05).

| Treatment |

TU(μm) |

TL(μm) |

TP(μm) |

TS(μm) |

LT(μm) |

| CK |

19.07±0.90b |

7.83±0.38b |

60.07±1.34a |

76.70±2.16a |

154.40±3.99a |

| T1 |

11.53±0.99a |

6.40±0.56b |

56.23±2.09abc |

72.87±1.73ab |

145.97±0.75b |

| T2 |

12.40±0.72a |

8.33±1.28ab |

51.60±2.22bc |

66.90±0.69b |

138.00±2.79bc |

| T3 |

19.50±1.02b |

11.47±1.33a |

57.10±0.51ab |

77.13±3.59a |

158.37±1.03a |

| T4 |

19.53±1.55b |

7.27±0.73b |

51.33±1.44c |

67.67±2.72b |

137.40±2.08c |