5.1. Interpretation of Key Findings

The most striking finding is the consistent negative and statistically significant relationship between the overall ESG_score and Excess_Return_Firm in the panel data models. This contradicts a commonly held belief of a universally positive ESG-CFP link, yet it aligns with some recent sector-specific empirical evidence, such as Matsali et al. [

13] in tourism services and Buniakova [

22] in IT services, both finding negative or no correlation. It is also consistent with the "trade-off hypothesis" explored by Erol et al. [

2] for environmental policies, where environmental investments might incur significant financial costs. Possible explanations for this negative relationship, especially within this specific sample of "Commercial Services & Supplies" firms, include: (1) Cost of ESG Implementation: Service firms might be incurring significant short-to-medium term costs for ESG initiatives (e.g., green technologies, labor improvements, enhanced reporting) that are not yet offset by financial benefits or market appreciation. This is supported by Erol et al. [

2], who found environmental policies for REITs involve high financial costs. (2) Market Inefficiency or Overvaluation: It is possible that the market in this specific sector or period does not adequately reward ESG performance, or that firms with higher ESG scores are already overvalued, leading to lower subsequent excess returns. (3) Sample Specificity: Given the very small sample of 14 firms, these results may be highly specific and not broadly generalizable. The broad category of "Commercial Services & Supplies" might also mask heterogeneous impacts. The lack of significance of decomposed ESG factors in the fixed effects model suggests that the aggregate ESG score might capture a broader effect, or that individual components have non-linear or interacting effects not fully captured by the linear models. This contrasts with Yin et al. [

1] and Kong et al. [

14], who found positive ESG-CFP links, often with mediating factors like innovation, indicating differing market contexts (e.g., China vs. global tech leaders).

The significant and positive coefficients for SMB, RMW, WML, and FF_HML_CMA_PC1 (a combination of value and investment factors) align with established Asset Pricing Theory [

31]. This indicates that small-cap service firms, those with robust profitability, those exhibiting strong momentum, and those with value characteristics coupled with conservative investment strategies, tend to generate higher excess returns. This confirms that these traditional market factors remain fundamental drivers of firm performance in the service sector, consistent with studies like Onomakpo [

29], which also found firm size to be consistently significant in EV manufacturing. These factors provide systematic explanations for return differentials beyond simply market exposure.

The time series analysis revealed that lagged changes in the market-level ESG factor significantly influence market excess returns (Mkt-RF), suggesting a dynamic interdependency. However, the Granger causality tests found no strong evidence of predictive power in either direction between Mkt-RF and Market_ESG_Factor_VW. This implies that, within the tested lags and short sample period, past market returns do not linearly predict market-level ESG, and vice versa. This could indicate that the market-level ESG factor is either already efficiently priced or its relationship with market returns is more complex and non-linear. The GARCH model, while theoretically relevant for volatility modeling, yielded non-significant parameters for Mkt-RF volatility, primarily due to the extremely limited number of annual observations, hindering robust conclusions about volatility clustering.

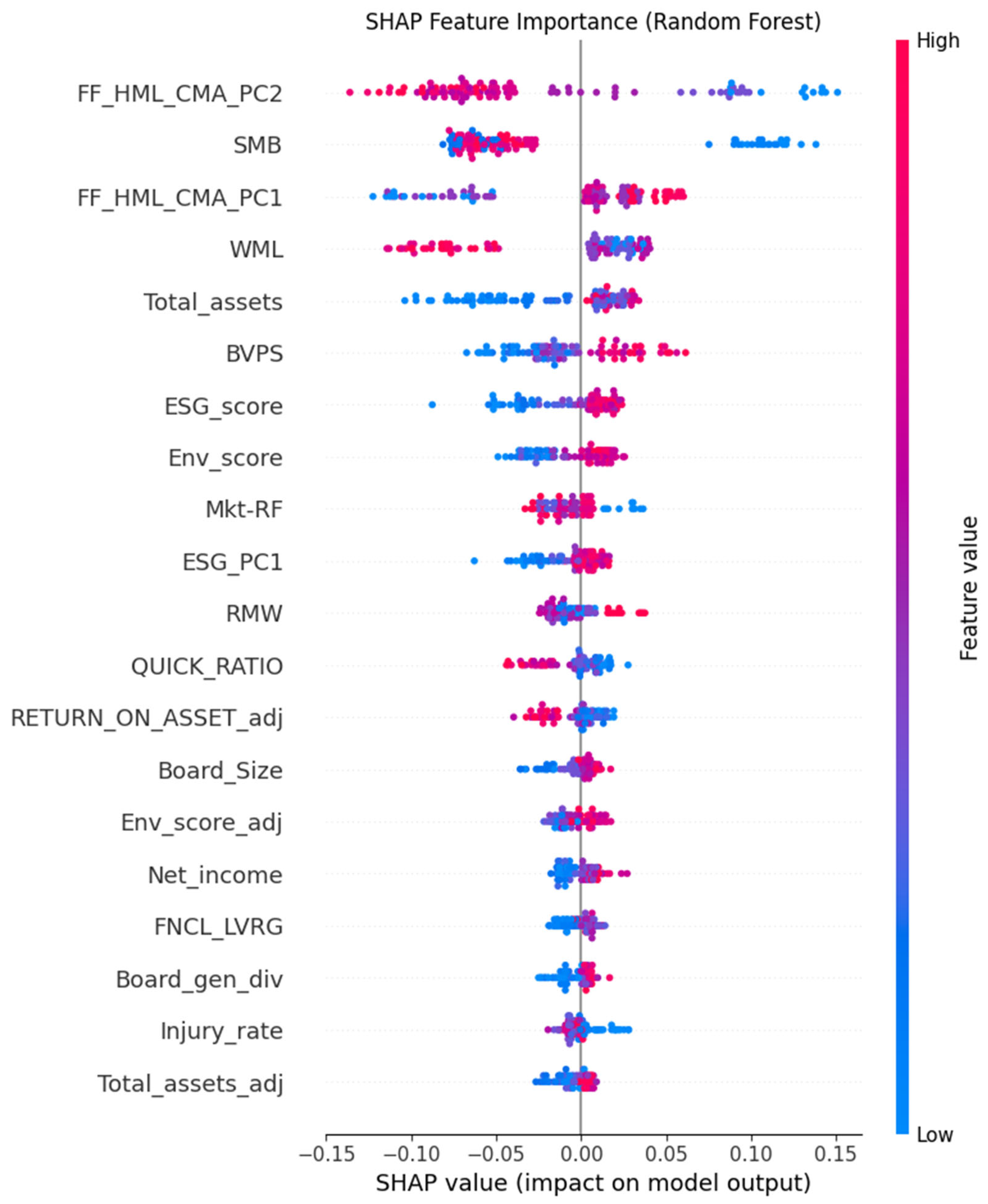

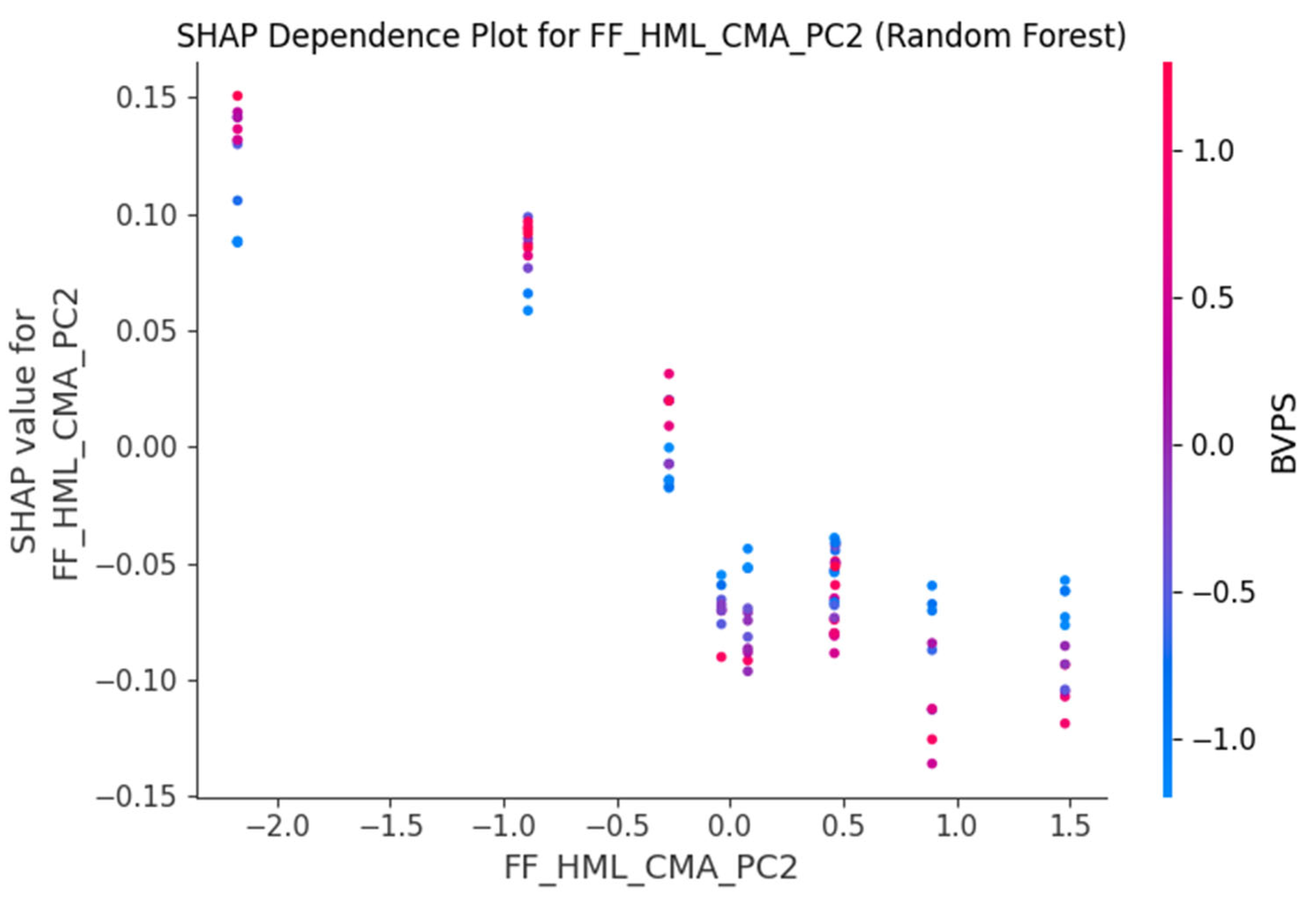

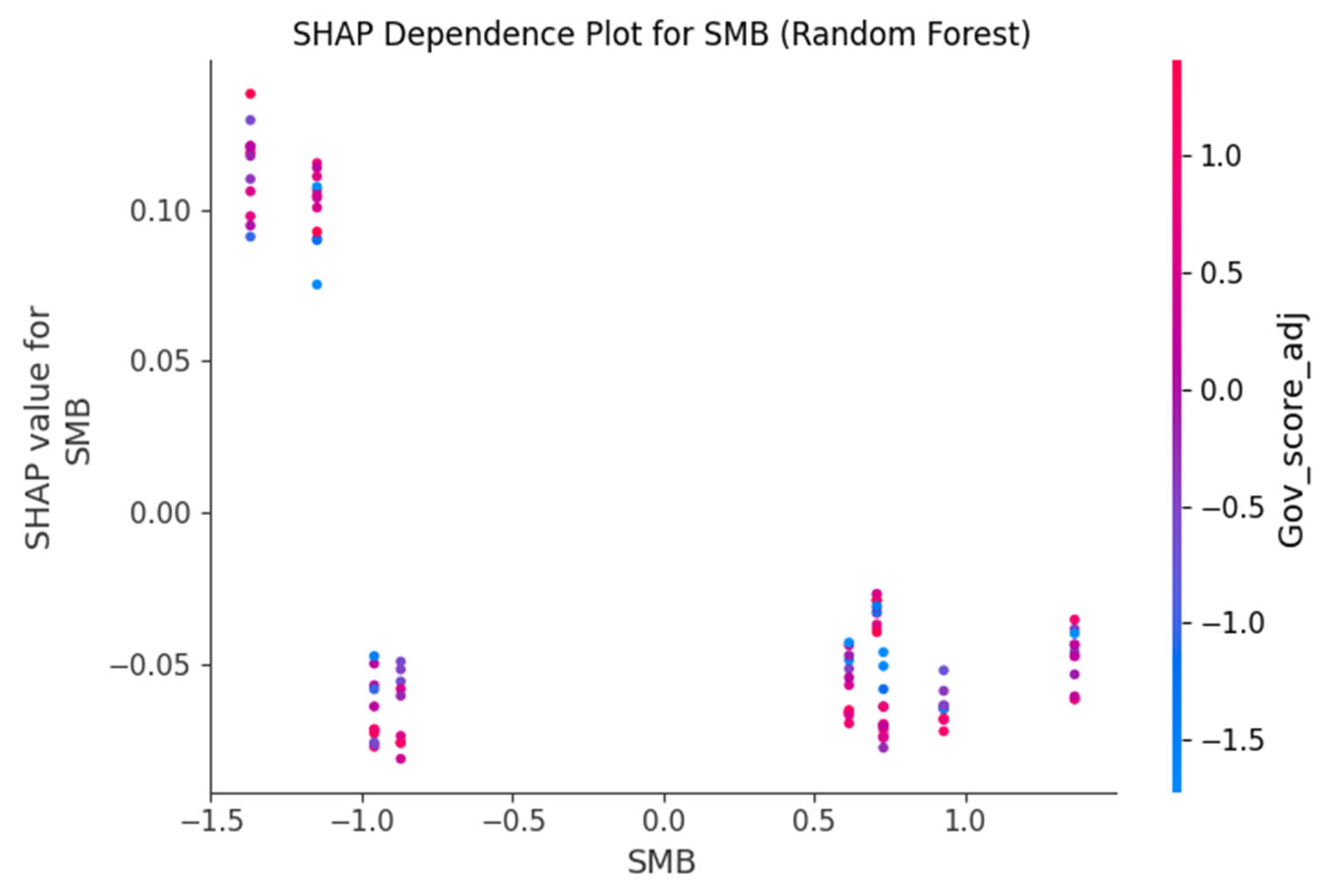

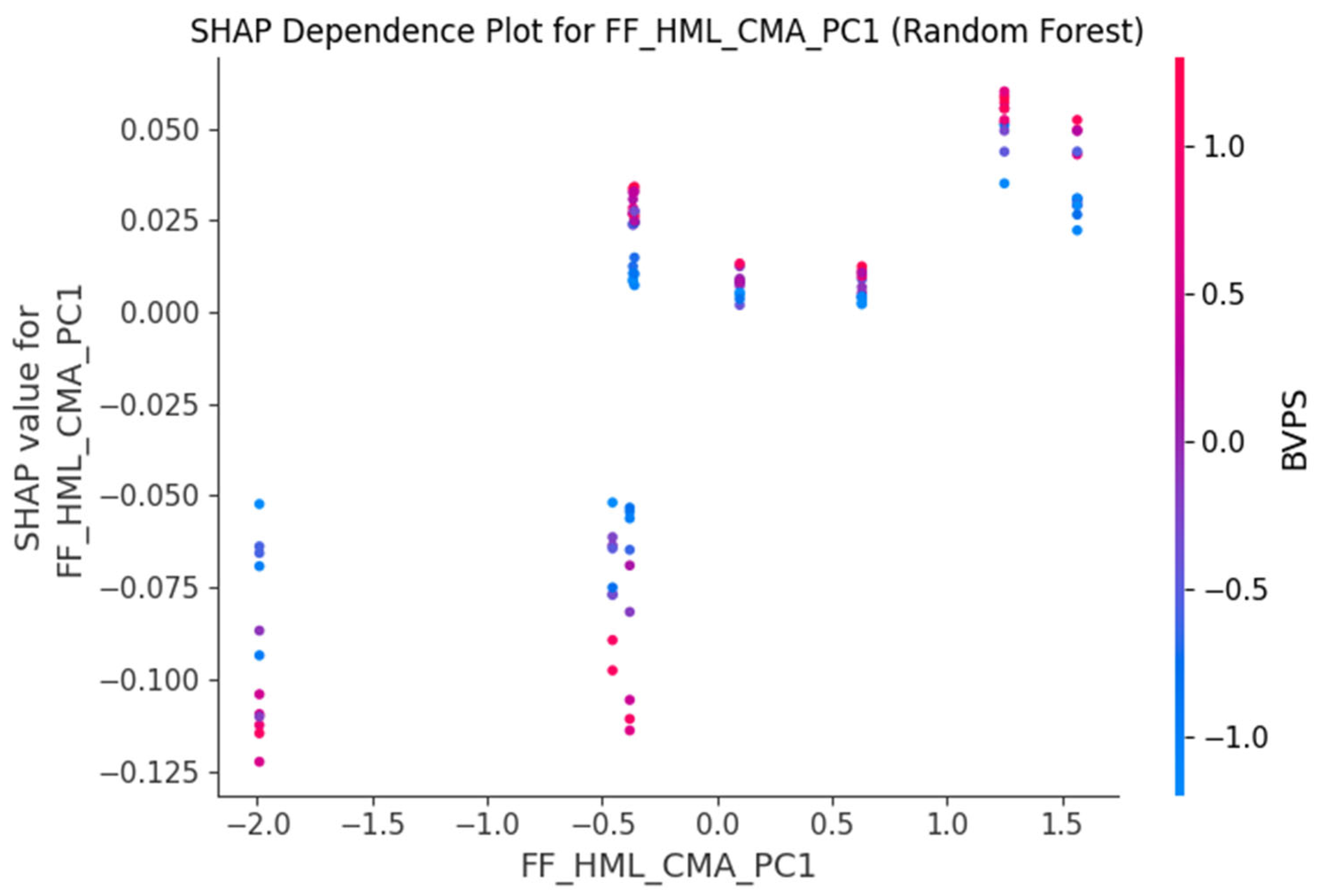

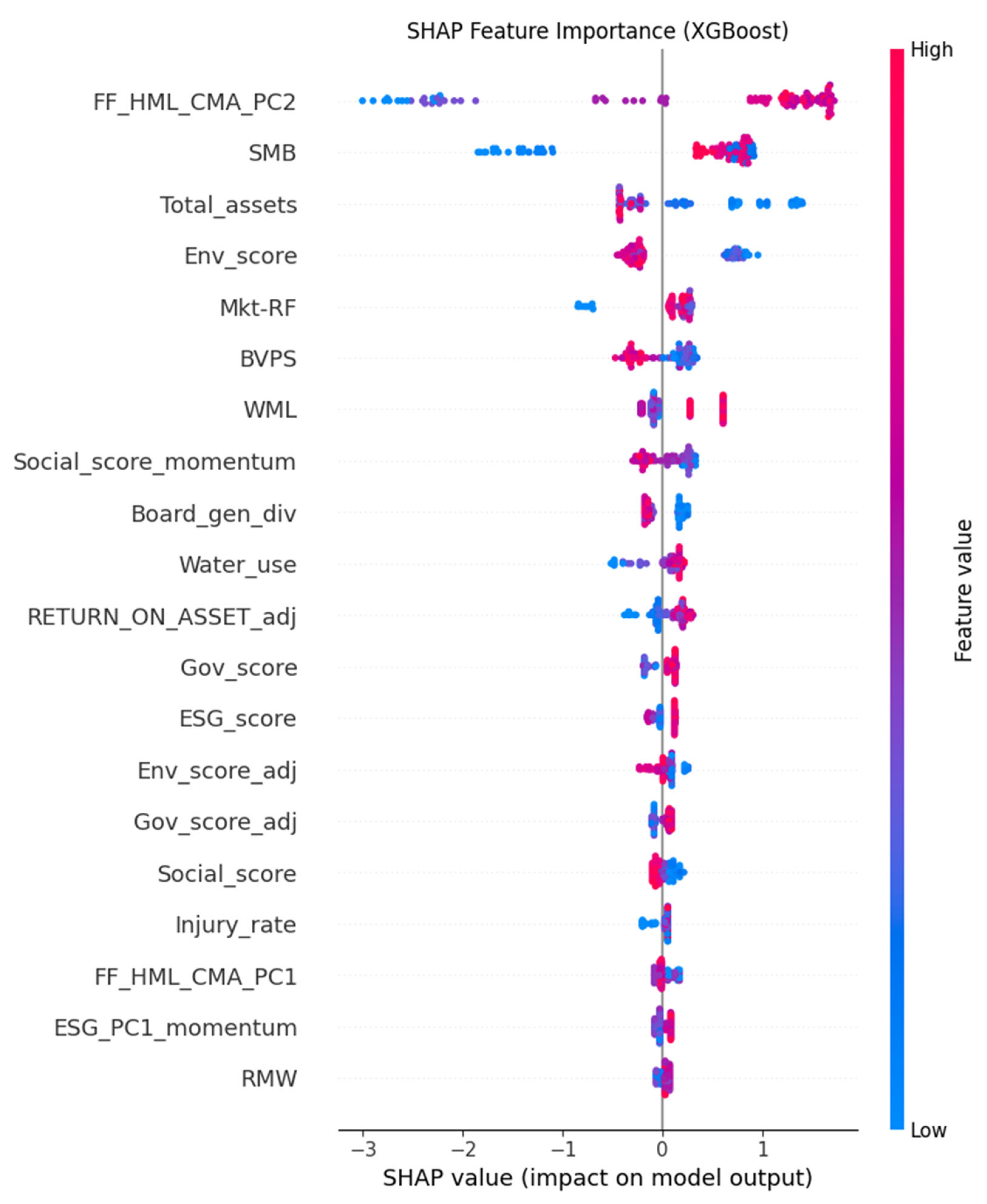

The remarkably high predictive performance (ROC AUCs of ~0.95–0.98) of Random Forest and XGBoost models for forecasting the direction of future excess returns is promising. This highlights the ability of ML models to capture complex, non-linear relationships from a diverse set of financial and ESG features. The feature importance analysis shows that Fama-French factors (FF_HML_CMA_PC2, SMB, WML, FF_HML_CMA_PC1, RMW) and firm-specific financial ratios (Total_assets, BVPS) are highly influential predictors. Importantly, ESG-related features (ESG_score, Env_score_adj, Injury_rate, Water_use) also contributed significantly to the predictive power in the ML models, suggesting that even if their linear relationship with returns is negative, they contain valuable information for predicting future trends in a non-linear context. This demonstrates the added value of machine learning in uncovering subtle patterns missed by linear econometric methods.

5.2. Answers to Research Questions

This section explicitly addresses each of the research questions posed in the Introduction, leveraging the empirical findings and their interpretation.

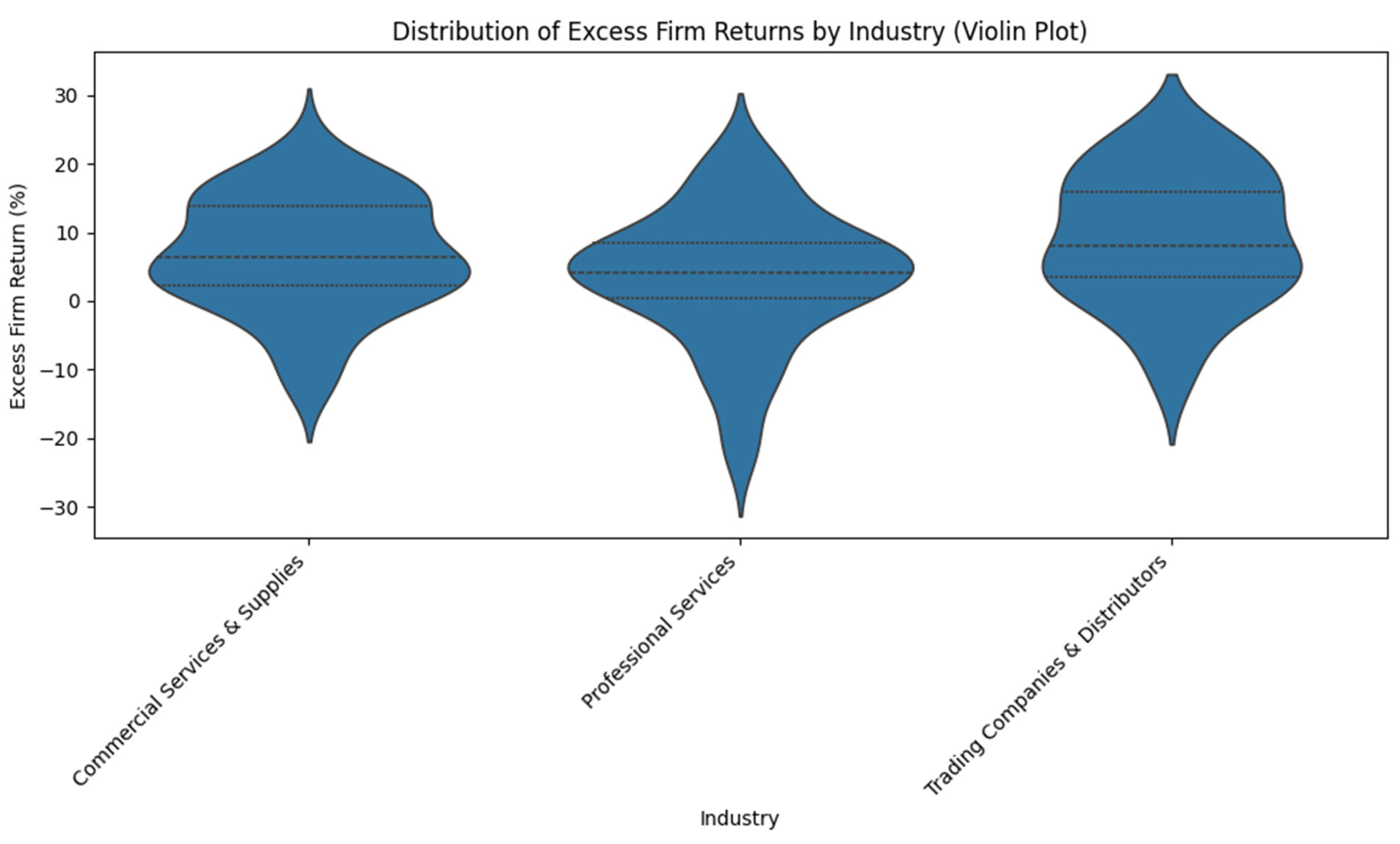

Research Question 1: How do traditional asset pricing factors (Mkt-RF, SMB, HML, RMW, CMA, WML) and aggregated ESG scores influence the excess returns of service sector firms?

The panel data analysis, presented in

Table 4, demonstrates that traditional asset pricing factors play a significant role in influencing the excess returns of service sector firms within the sample. Specifically, the SMB (Small-Minus-Big), RMW (Robust-Minus-Weak), and WML (Winners-Minus-Losers) factors consistently exhibit positive and highly significant coefficients across all estimated models (Pooled OLS, Fixed Effects, and Random Effects). Furthermore, the principal component capturing the combined effects of HML (High-Minus-Low) and CMA (Conservative-Minus-Aggressive), FF_HML_CMA_PC1, also shows a strong positive and significant influence on excess returns. These findings are consistent with established Asset Pricing Theory [

31] and prior industry-specific studies, such as Onomakpo [

29] in EV manufacturing, which highlight the persistence of these factors in explaining stock performance. Conversely, the aggregated ESG score reveals a consistent and statistically significant negative relationship with excess returns across all panel models (

Table 4). This unexpected finding suggests that, for the service firms in this sample and during the studied period, higher overall ESG performance was associated with lower excess returns, a result that stands in contrast to common positive associations found in some broader market studies [

1,

14] but aligns with specific sector-level observations [

13,

22]. The scatter plot of excess returns by year (

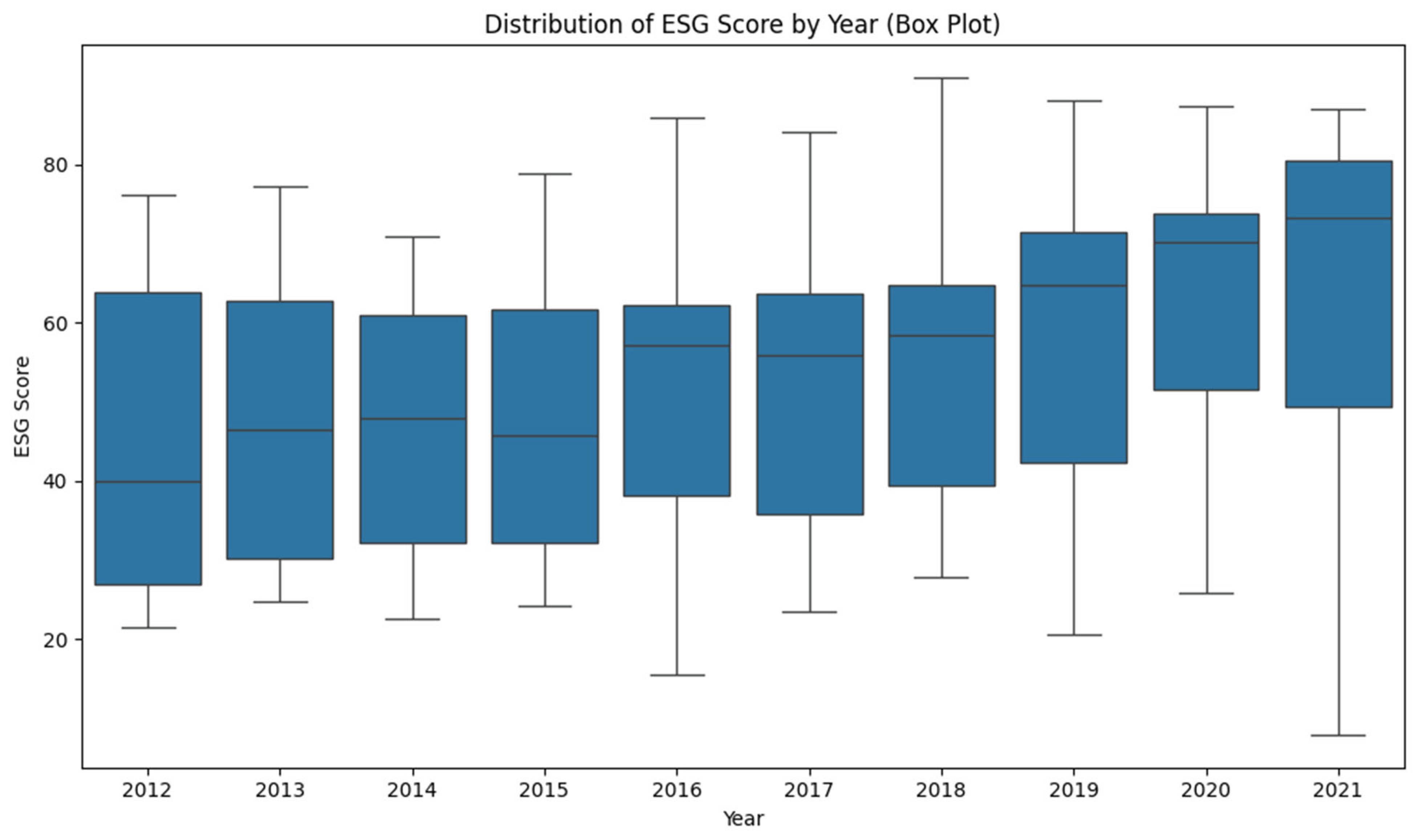

Figure 2) visually confirms the variations in firm performance over time, which these factors attempt to explain.

Research Question 2: What are the relationships and interdependencies between market-level ESG factors and market returns over time?

The time series analysis, specifically the Vector Autoregression (VAR) model summarized in

Table 6, indicates significant interdependencies between lagged changes in the market-level ESG factor and current market excess returns (Mkt-RF). For instance, both the first and second lags of Market_ESG_Factor_VW_diff significantly influence Mkt-RF. However, when subjected to Granger causality tests (

Table 7), no strong evidence was found to suggest that Mkt-RF Granger-causes Market_ESG_Factor_VW, nor vice versa, within the tested lags. This implies a lack of simple linear predictive power between these aggregate market series in the short term, despite some observed dynamic associations in the VAR model. The GARCH(1,1) model fitted to Mkt-RF (

Table 8) showed a statistically significant mean return, but its volatility parameters (omega, alpha[

1], beta[

1]) were non-significant, largely due to the limited number of annual observations, thus hindering robust conclusions about volatility clustering.

Figure 1 depicts the time series dynamics of ESG scores and market ESG components, as well as the data used in this analysis.

Research Question 3: Can machine learning models effectively predict the direction of future excess returns for service sector firms based on financial and ESG data?

Yes, machine learning models demonstrated remarkable predictive capabilities for forecasting the direction of future excess returns for service sector firms. Both the tuned Random Forest Classifier and XGBoost Classifier achieved high performance metrics, with ROC AUCs of 0.9497 (

Table 9) and 0.9695 (

Table 10), respectively. The full classification reports (

Table 11 and

Table 12) further confirm strong accuracy, precision, and recall, even for the minority class. Feature importance analysis (

Table 13 and

Table 14) revealed that Fama-French factors (FF_HML_CMA_PC2, SMB, WML, FF_HML_CMA_PC1, RMW) and firm-specific financial ratios (Total_assets, BVPS) were highly influential predictors. Importantly, ESG-related features (ESG_score, Env_score_adj, Injury_rate, Water_use) also contributed significantly to the predictive power of these models. The SHAP summary plots (

Figure 3 for Random Forest and

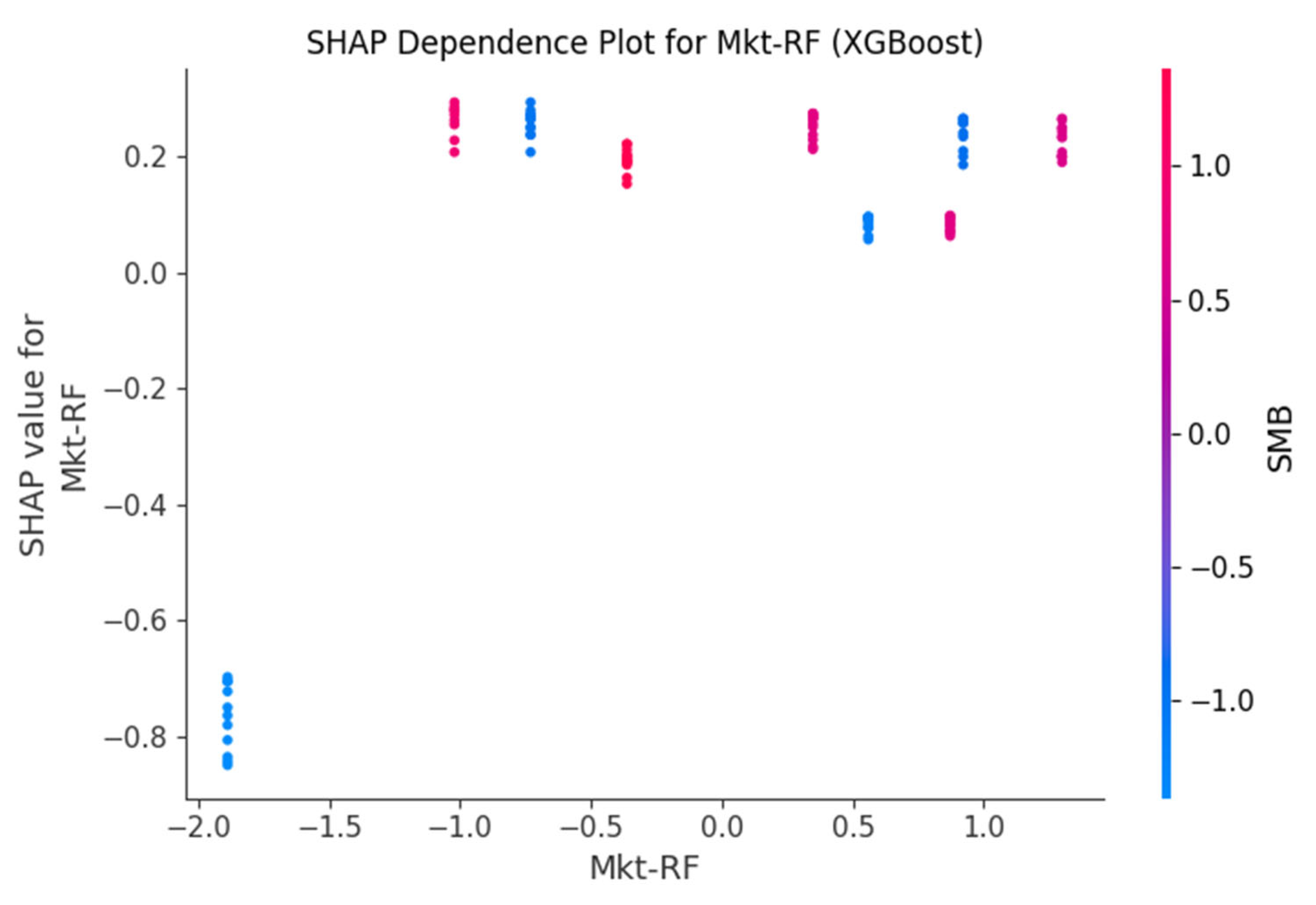

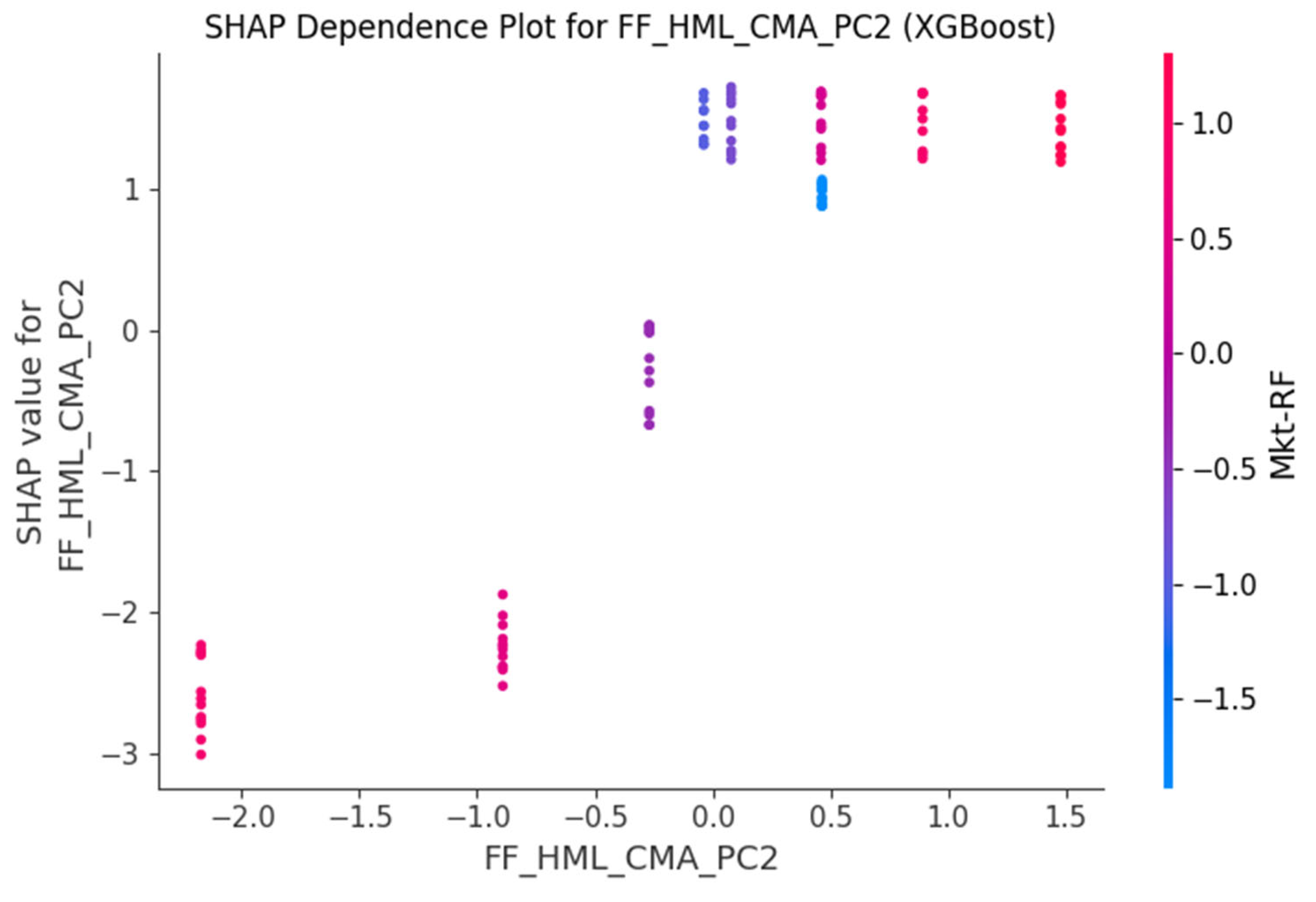

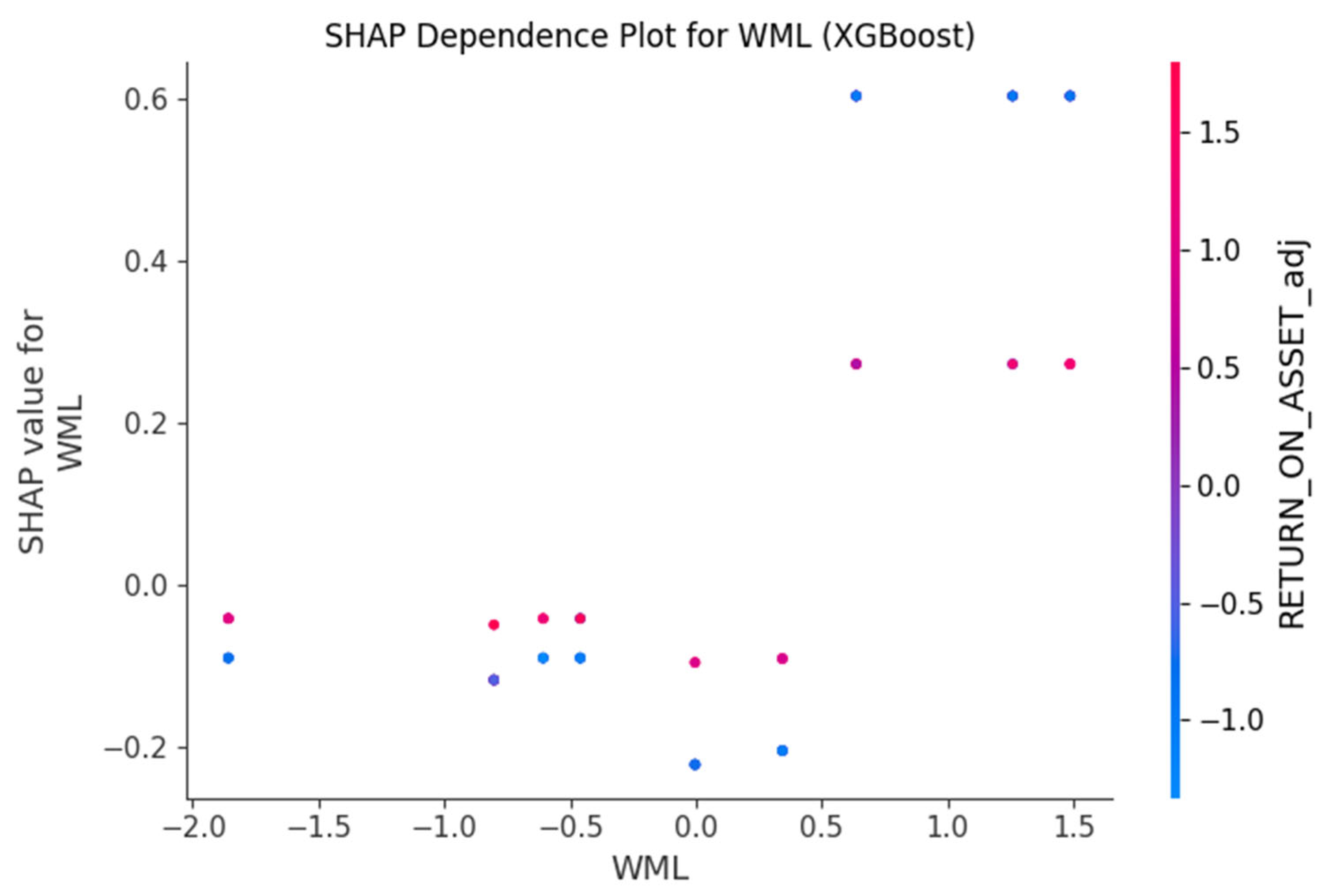

Figure 7 for XGBoost) visually confirm the overall impact of these features on predictions. Dependence plots (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 for Random Forest;

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 for XGBoost) offer insights into potential non-linear relationships. This high predictive performance highlights the ability of ML models to capture complex, non-linear patterns within combined financial and ESG data, distinguishing their utility from traditional linear models. However, it is crucial to reiterate the CRITICAL WARNING that these results are based on a very small sample size (14 unique firms) and should be interpreted as exploratory, with limited generalizability beyond the dataset.

Research Question 4: Do individual components of ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) have a distinct impact on service sector firm performance compared to the aggregated ESG score?

The analysis suggests that, within the linear panel data framework for this sample, the individual components of ESG do not show a statistically significant distinct impact on service sector firm excess returns, in contrast to the aggregated ESG score. The Fixed Effects model with decomposed ESG factors (

Table 5), which included ESG_PC1, Social_score, Gov_score, and Env_score as independent variables, found that none of these individual components had a statistically significant relationship with excess returns. This contrasts with some literature that finds distinct impacts for individual E, S, or G pillars [

2,

13]. This finding implies that the overall ESG score might capture a more holistic effect not linearly apparent in its disaggregated parts, or that the individual sub-scores are too noisy or collinear when separated in this specific sample.

5.3. Link to Theoretical Framework and Existing Literature

The observed negative ESG-return relationship in this study for the service sector presents a nuanced perspective on Stakeholder Theory, challenging a simplistic positive association. Instead, it suggests that the relationship is complex and context-dependent, potentially reflecting the costs of ESG implementation or market inefficiencies in valuing ESG in certain service sub-sectors, aligning with sector-specific empirical evidence from Matsali et al. [

13] and Buniakova [

22]. This emphasizes that "doing good" might incur immediate costs that are not instantly rewarded by the market in terms of excess returns, thus prompting a deeper theoretical exploration into the time horizons and specific mechanisms through which ESG investments translate into financial value in the service industry. The consistent findings on Fama-French factors remain in line with Asset Pricing Theory [

31], confirming their explanatory power for service firm returns.

The adoption of Digital Transformation, viewed through the lens of Open Innovation Theory [

30], can contribute significantly to financial outcomes. While not directly measured as a variable in the panel regression, the ability of service firms to leverage digital ecosystems and external collaborations [

28] through open innovation practices can enhance operational efficiency, foster innovation [

19], and improve customer experience. Vincenzi and da Cunha [

32] directly support the positive link between open innovation and performance in the service sector. The inclusion of ESG-related features in the top ML predictors suggests that the market recognizes these non-financial factors as important for future firm trajectory, potentially reflecting stakeholder value creation or risk mitigation through non-linear channels.

5.5. Limitations of the Study

The most significant limitation of this study is the very small sample size (14 unique firms) and limited time series (10 years). This severely restricts the generalizability and statistical power of all models, especially the ML models and time series analysis. Results should, therefore, be interpreted as exploratory. While comprehensive, the ESG data relies on Refinitiv's scoring methodology, which might not capture all nuances relevant to the diverse service sector's specific impact. The chosen firms are primarily categorized under "Commercial Services & Supplies," which is a broad category, and findings might not apply uniformly across all service sub-sectors. Some econometric models rely on assumptions (e.g., adequate sample size for GARCH) that might be challenged by small samples. Furthermore, while panel data helps control for unobserved firm-specific effects, establishing definitive causality in the ESG-performance relationship is complex due to potential endogeneity. Finally, the study quantifies ESG and financial factors, but does not directly measure the financial impact of every "key trend" (e.g., specific AI adoption rates, detailed customer experience metrics), limiting the scope of a comprehensive analysis on all listed trends.