3.2. Data Collection and Sources

The study’s methodology commenced with careful data collection and identification of reliable sources.

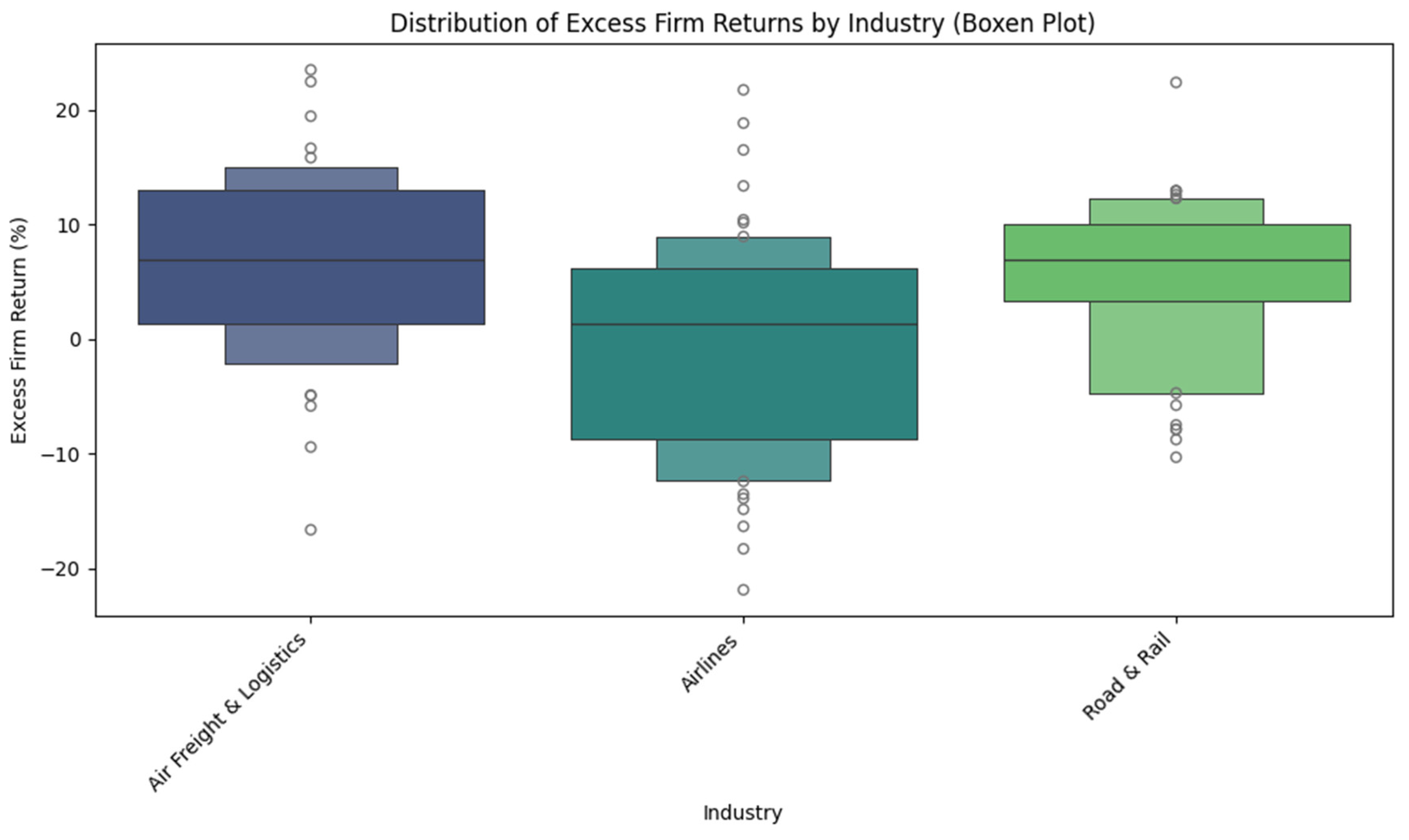

For Sample Selection, the study analyzes a carefully selected sample of 14 unique publicly traded transportation and logistics firms. The data spans an annual period from 2012 to 2021, resulting in a 10-year observation window for each firm. The selection criteria specifically prioritized firms with consistent data availability across the specified timeframe to ensure comparability and consistency of regulatory and economic environments, thus enhancing the credibility of the findings regarding the “countries analyzed.”

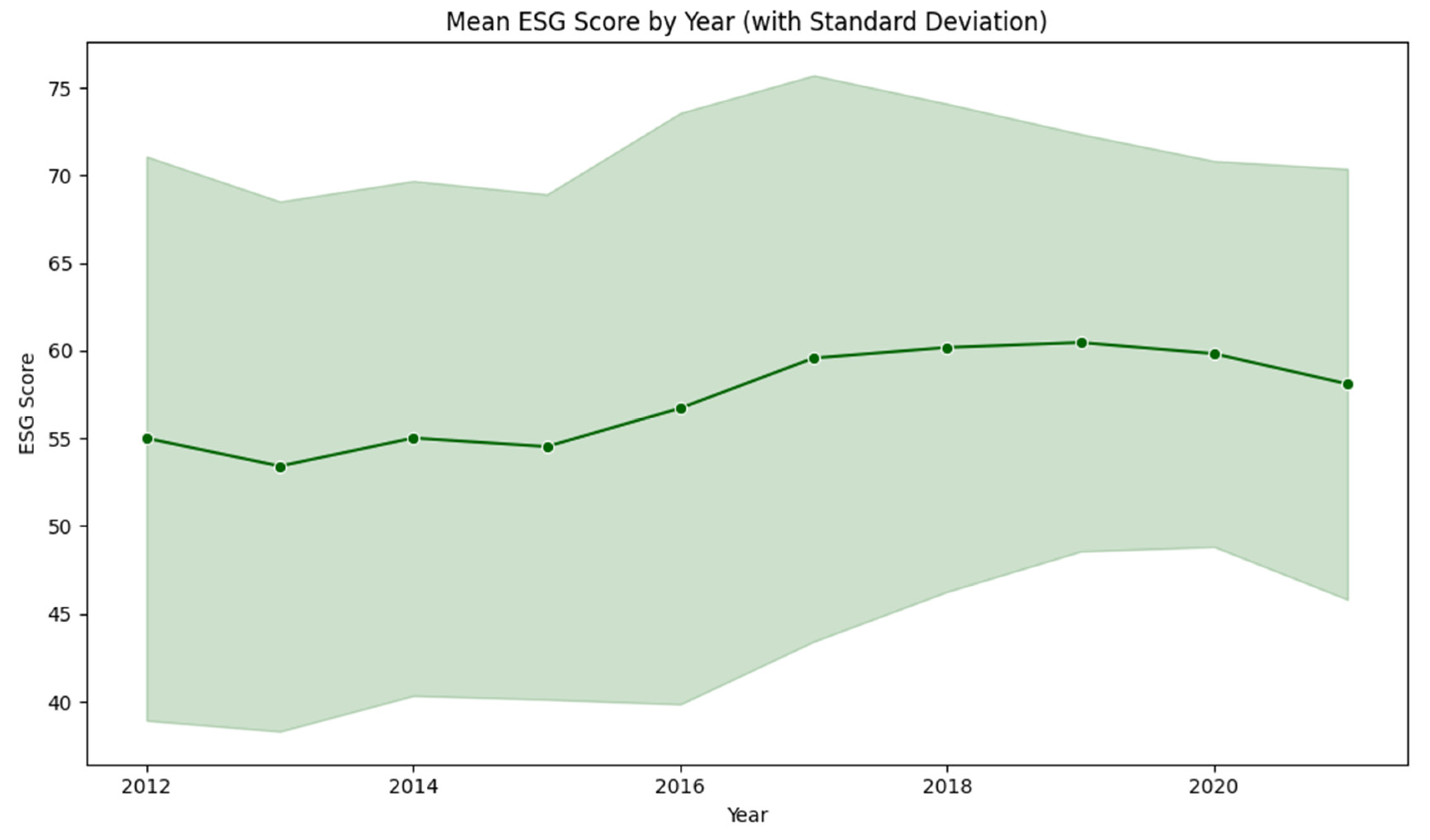

Regarding Data Sources, firm-level Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) and financial data were primarily obtained from Bloomberg and Refinitiv terminals. To enhance data robustness and allow for cross-validation, these data were triangulated with ESG-risk-rating data from reputable providers such as Sustainalytics, MSCI, and Morningstar. Established asset pricing factor data, encompassing Mkt-RF, SMB, HML, RMW, CMA, RF, and WML, were meticulously sourced from Kenneth French’s data library, a widely recognized and authoritative academic resource.

Variables: This section outlines the specific variables utilized in the study, categorized into dependent and independent types.

For the Dependent Variable, the primary dependent variable is Excess_Return_Firm, which is calculated as the firm’s annual stock return minus the risk-free rate (RF). The rationale for selecting this variable is its established use in financial economics for measuring risk-adjusted performance, allowing for direct comparison with asset pricing models and providing a standard metric for evaluating investment performance.

Turning to the Independent Variables, several distinct categories were included. First, for Asset Pricing Factors, this set includes Mkt-RF (market excess return), SMB (Small Minus Big), RMW (Robust Minus Weak), and WML (Winners Minus Losers - Momentum Factor). Due to empirically observed high multicollinearity between HML (High Minus Low) and CMA (Conservative Minus Aggressive), Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was systematically applied to these two factors. This yielded two orthogonal components, FF_HML_CMA_PC1 and FF_HML_CMA_PC2, which collectively capture their combined variance while effectively mitigating multicollinearity. These factors are selected as empirically established proxies for various dimensions of market, size, value, profitability, investment, and momentum risks, thereby providing a robust baseline for explaining equity returns.

Next, concerning ESG Factors, the core ESG factors analyzed are ESG_score (representing overall ESG performance), Social_score, Gov_score, and Env_score (environmental performance). Recognizing potential interdependencies among these individual ESG sub-scores, PCA was strategically applied to Social_score, Gov_score, and Env_score. This process derived ESG_PC1, a consolidated measure that explains a significant portion of their collective variance while directly addressing the impact of sustainability performance.

To ensure a comprehensive model, various standard Firm-Specific Financial/Operational Controls were included as control variables. These include BVPS (Book Value Per Share), Market_cap (Market Capitalization), Shares (Number of Shares Outstanding), Net_income, PE_RATIO (Price-to-Earnings Ratio), RETURN_ON_ASSET, Total_assets, and QUICK_RATIO. These variables are chosen for their known influence on firm performance, serving to isolate the specific effects attributed to ESG and market factors.

Furthermore, where data availability permitted, additional granular Detailed ESG/Sustainability Controls were considered. These include Scope_1 (direct greenhouse gas emissions), Scope_2 (indirect greenhouse gas emissions), CO2_emissions, Energy_use, Water_use, Water_recycle, Toxic_chem_red (toxic chemical reduction), Injury_rate, Women_Employees, Human_Rights policy presence, Strikes (labor disputes), Turnover_empl (employee turnover), Board_Size, Shareholder_Rights score, Board_gen_div (board gender diversity), Bribery controls, and Recycling_Initiatives. These were included for their potential to provide a more nuanced view of ESG impact, although their direct inclusion in final models depended on data completeness and statistical significance.

For Engineered Features for ML, to enrich the dataset and enhance the predictive power of the machine learning models, several engineered features were meticulously created. These include momentum features (ESG_score_momentum, Social_score_momentum, Gov_score_momentum, Env_score_momentum, and ESG_PC1_momentum), representing year-over-year changes in these ESG metrics. Additionally, industry-adjusted features (ESG_score_adj, Social_score_adj, Gov_score_adj, Env_score_adj, ESG_PC1_adj, Market_cap_adj, RETURN_ON_ASSET_adj, PE_RATIO_adj, Total_assets_adj) were computed by subtracting the industry average from each firm’s value, thereby capturing their relative performance within the sector. These features are specifically engineered to capture dynamic effects and relative performance, significantly enhancing the predictive capabilities of the machine learning models.

A Market-level ESG Factor, Market_ESG_Factor_VW (Value-weighted Market ESG Factor), was constructed by aggregating the ESG scores across all firms in the sample, weighted by their respective market capitalization. This variable was designed to capture aggregate ESG trends within the transportation and logistics sector for use in time series analysis.

Finally, for the machine learning classification task, the Target Variable for ML, Excess_Return_Firm_next_year_Direction, was created as a binary variable. It is assigned a value of 1 if the Excess_Return_Firm in the subsequent year is positive, and 0 otherwise (negative or zero). This binary variable simplifies the prediction task for classification models and provides actionable insights into the likelihood of future positive returns.

3.4. Econometric Models

Panel regression models were chosen as the primary econometric tool for analyzing firm-level data over time. This approach offered robust insights into financial performance determinants by effectively controlling for unobserved firm-specific heterogeneity that could bias Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regressions.

The Pooled OLS model served as a baseline, representing a standard linear regression that assumed constant coefficients across all firms and periods, thus ignoring any inherent panel structure. Robust standard errors were applied to address common issues like heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation in financial panel data, ensuring more reliable statistical inference. The Fixed Effects (Within) Model was employed to explicitly control for unobserved, time-invariant firm-specific heterogeneity, justified by the inherent diversity of firms within the transportation and logistics sector (e.g., unique management styles). By differencing out these fixed effects, the model estimated the impact of within-firm changes in independent variables on the dependent variable, providing unbiased coefficient estimates. Robust standard errors consistently ensured hypothesis test validity. The Random Effects Model offered an alternative to Fixed Effects, assuming unobserved firm-specific effects are uncorrelated with independent variables; if this assumption holds, it can provide more efficient estimates, also utilizing robust standard errors.

Model Selection Tests guided the choice among these panel models. An F-test for poolability (comparing Pooled OLS against Fixed Effects) determined if unobserved firm-specific effects were jointly significant, with a significant result indicating a preference for Fixed Effects. While the Hausman test (Fixed Effects vs. Random Effects) encountered a potential linearmodels library compatibility issue (Hausman test comparison method may have changed), the decision for the preferred panel model was primarily informed by the highly significant F-test for poolability and the overall F-statistic of the Fixed Effects model (Table 5, e.g., p-value of 0.0000). A highly significant F-statistic for Fixed Effects strongly suggested its appropriateness over simple OLS, indicating significant unobserved firm-specific heterogeneity.

Time series analysis was strategically chosen to understand the dynamic interdependencies and temporal evolution of market-level variables, particularly between market excess returns and aggregate ESG factors within the transportation and logistics sector. This approach provided insights into lead-lag relationships that cross-sectional or simple panel regressions might not capture.

Unit Root Tests (ADF Test) were performed on Mkt-RF and Market_ESG_Factor_VW to formally determine their stationarity (I(0)) or non-stationarity (I(1) or higher). This step was critical for ensuring the validity of subsequent Vector Autoregression (VAR) Model applications, as VAR models require stationary time series or cointegrated series to avoid spurious regression results [

52]. A VAR model was then applied to analyze the dynamic relationships between the stationary time series variables (Mkt-RF in levels and the first-differenced Market_ESG_Factor_VW_diff). The VAR model was suitable for investigating potential lead-lag relationships and interdependencies between multiple time series without imposing strong theoretical restrictions. The optimal lag length was systematically selected using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), balancing model fit with parsimony. Following VAR estimation, Granger Causality Tests assessed whether past values of one series statistically predict future values of another, even after controlling for the latter’s past values. This directly addressed Research Question 3, providing insights into directional predictability between market returns and market-level ESG factors.

A GARCH (Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity) Model, specifically GARCH(1,1), was employed to analyze and forecast the conditional volatility of Mkt-RF. This model is designed to capture volatility clustering, a common characteristic of financial time series [

52]. However, robust GARCH estimation typically requires significantly more observations (hundreds or thousands) than the 10 annual points available, potentially limiting result robustness and generalizability. The Breusch-Pagan test for VAR residuals could not be performed due to data limitations related to exogenous variable requirements.

Machine learning models were employed to capture complex, non-linear relationships and interactions that traditional econometric models might not fully discern, particularly for the prediction task. This approach leveraged modern computational power to identify intricate patterns in data for improved forecasting.

The primary Objective of the machine learning analysis was to predict Excess_Return_Firm_next_year_Direction, a binary classification (1 for positive excess return, 0 for negative/zero) providing actionable predictions for market participants. Feature Engineering, as detailed in

Section 3.2, was utilized to enrich the dataset and enhance predictive power via momentum features (e.g., ESG_score_momentum) and industry-adjusted features (e.g., ESG_score_adj), designed to capture dynamic effects and relative performance.

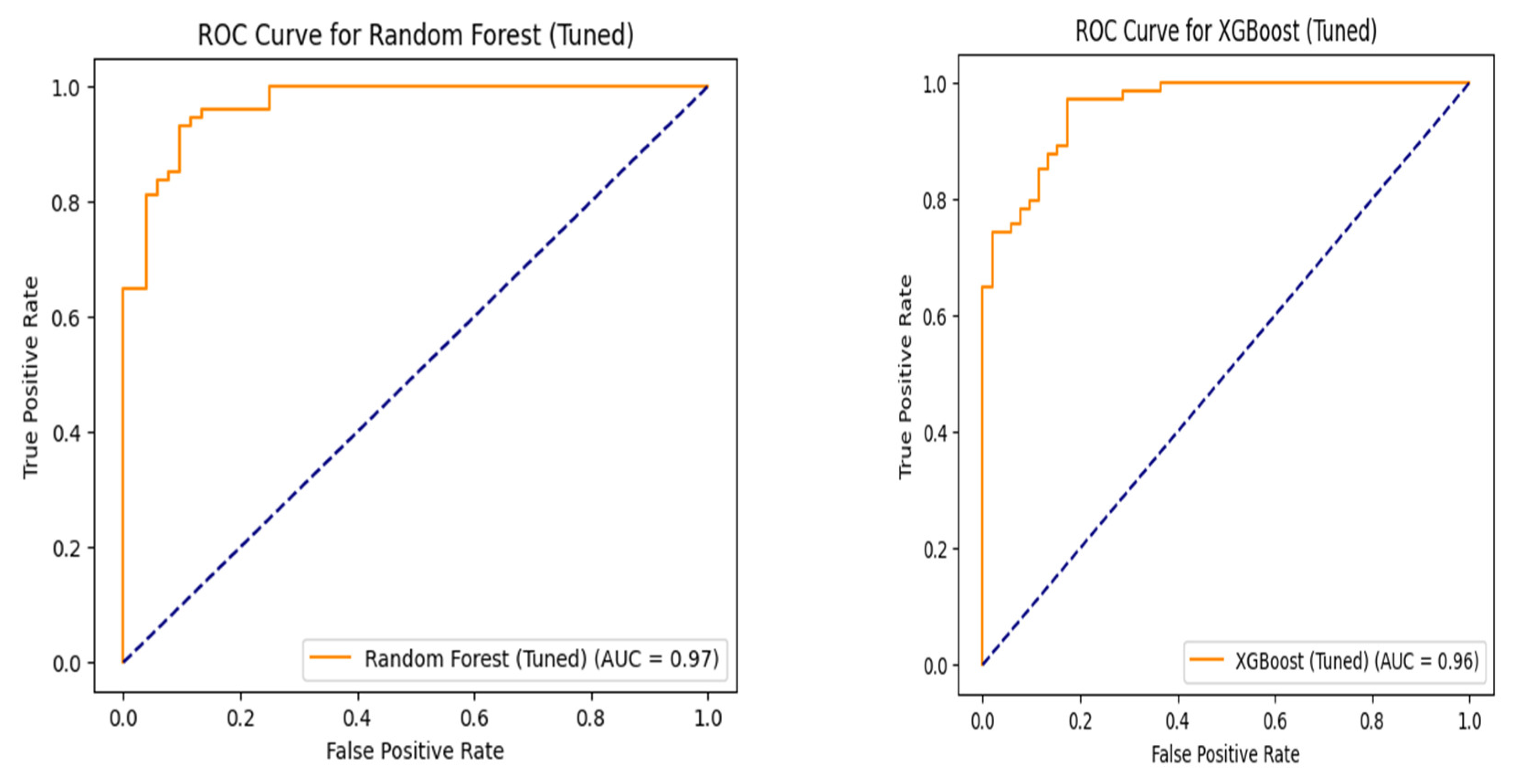

Random Forest Classifier and XGBoost Classifier were selected for the classification task. These ensemble methods are robust, handle high-dimensional data, capture complex interactions, and exhibit strong predictive performance, making them well-suited for financial classification [

18,

19]. To ensure robust model evaluation and mitigate data leakage, 5-fold Grouped Cross-Validation was implemented. This grouped observations by firm ID (RIC), ensuring firm-specific data remained together within folds, significantly improving generalizability. Grid Search was used for Hyperparameter Tuning for both models, systematically searching a predefined parameter grid (e.g., n_estimators, max_depth) to optimize performance on validation sets, typically for ROC AUC.

Evaluation Metrics included ROC AUC (as primary due to potential class imbalance), Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score. These were computed from consolidated predictions across all cross-validation folds, offering a comprehensive and less biased view of model effectiveness. The class distribution of the target variable (Excess_Return_Firm_next_year_Direction) was also examined for context.

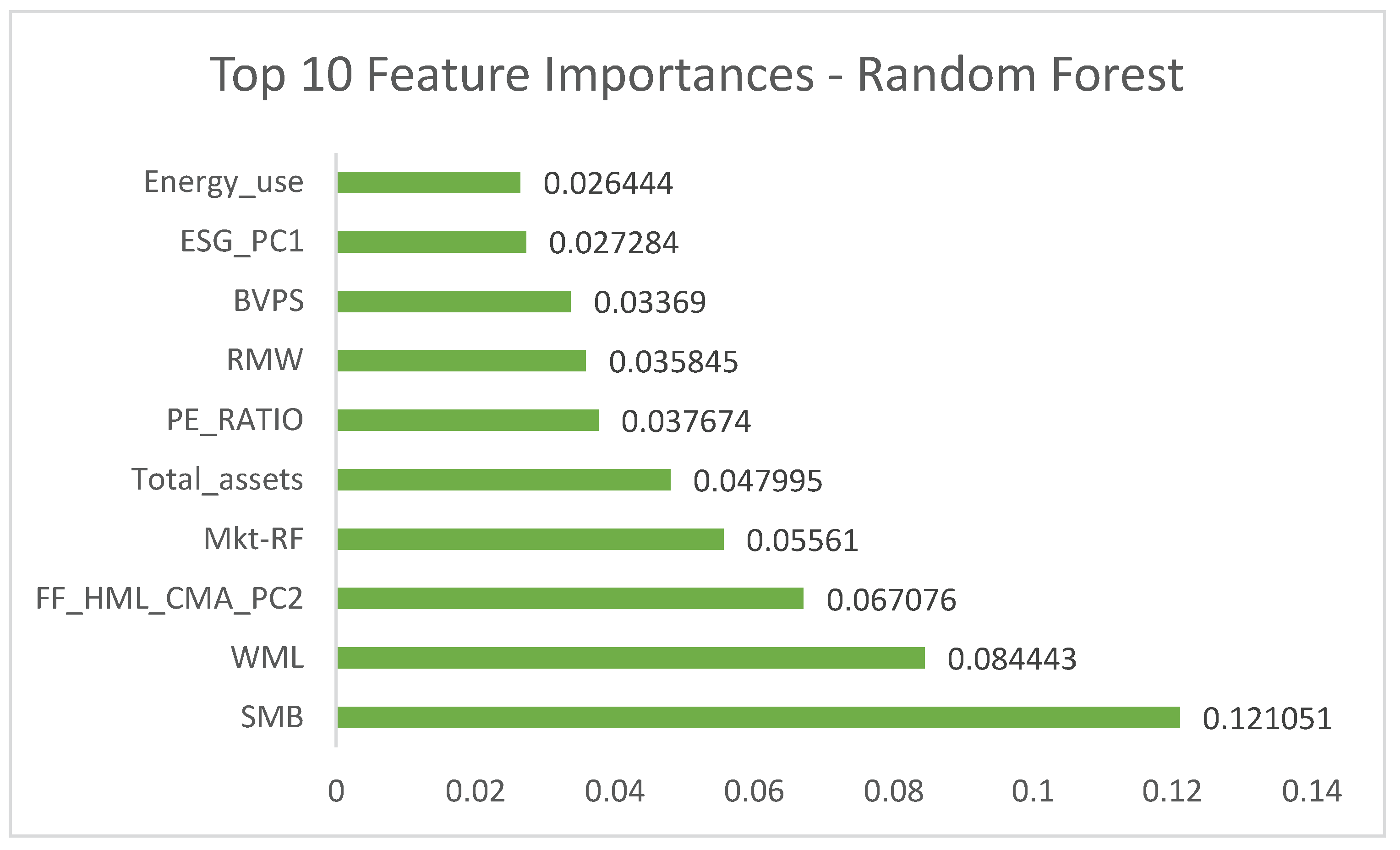

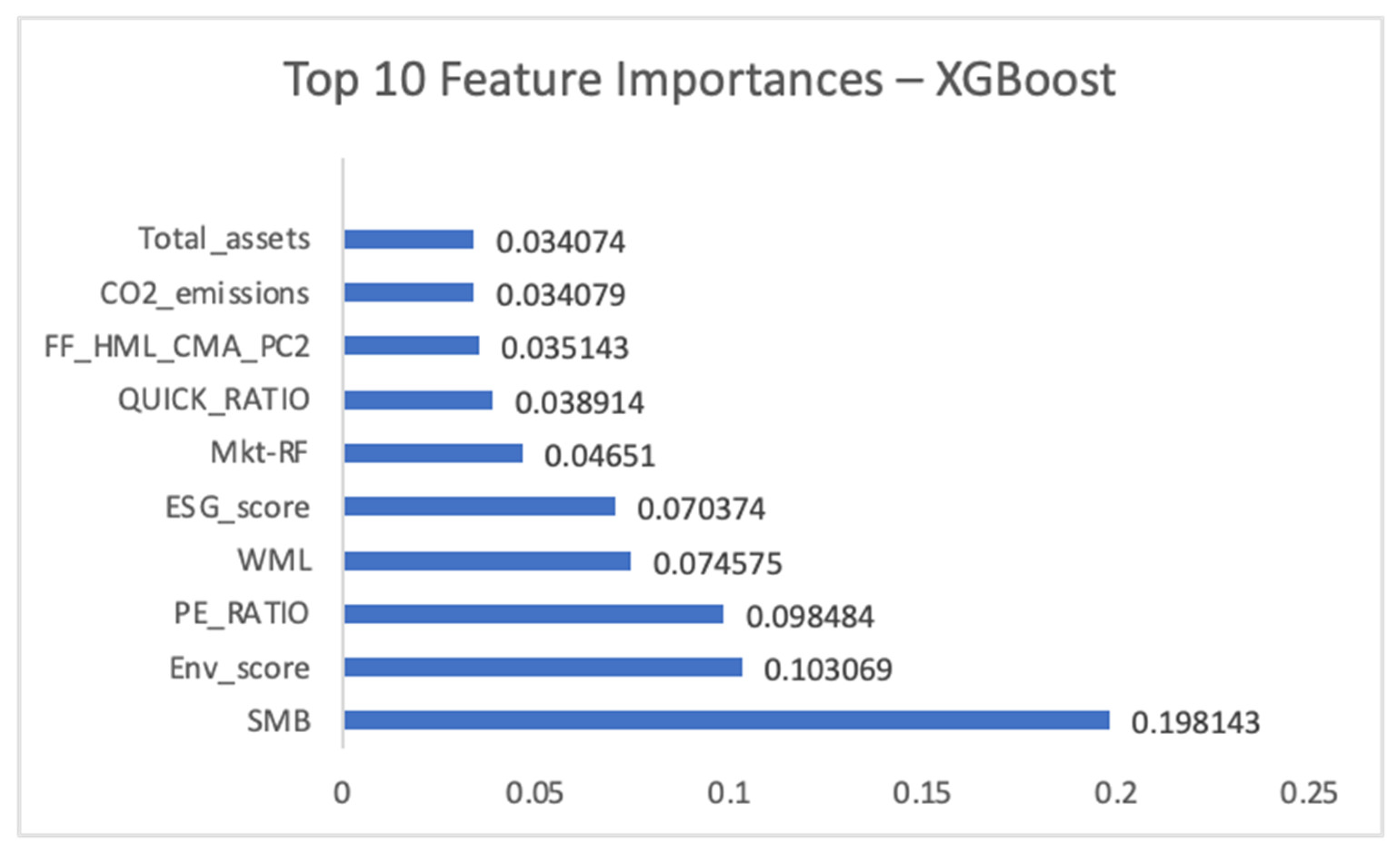

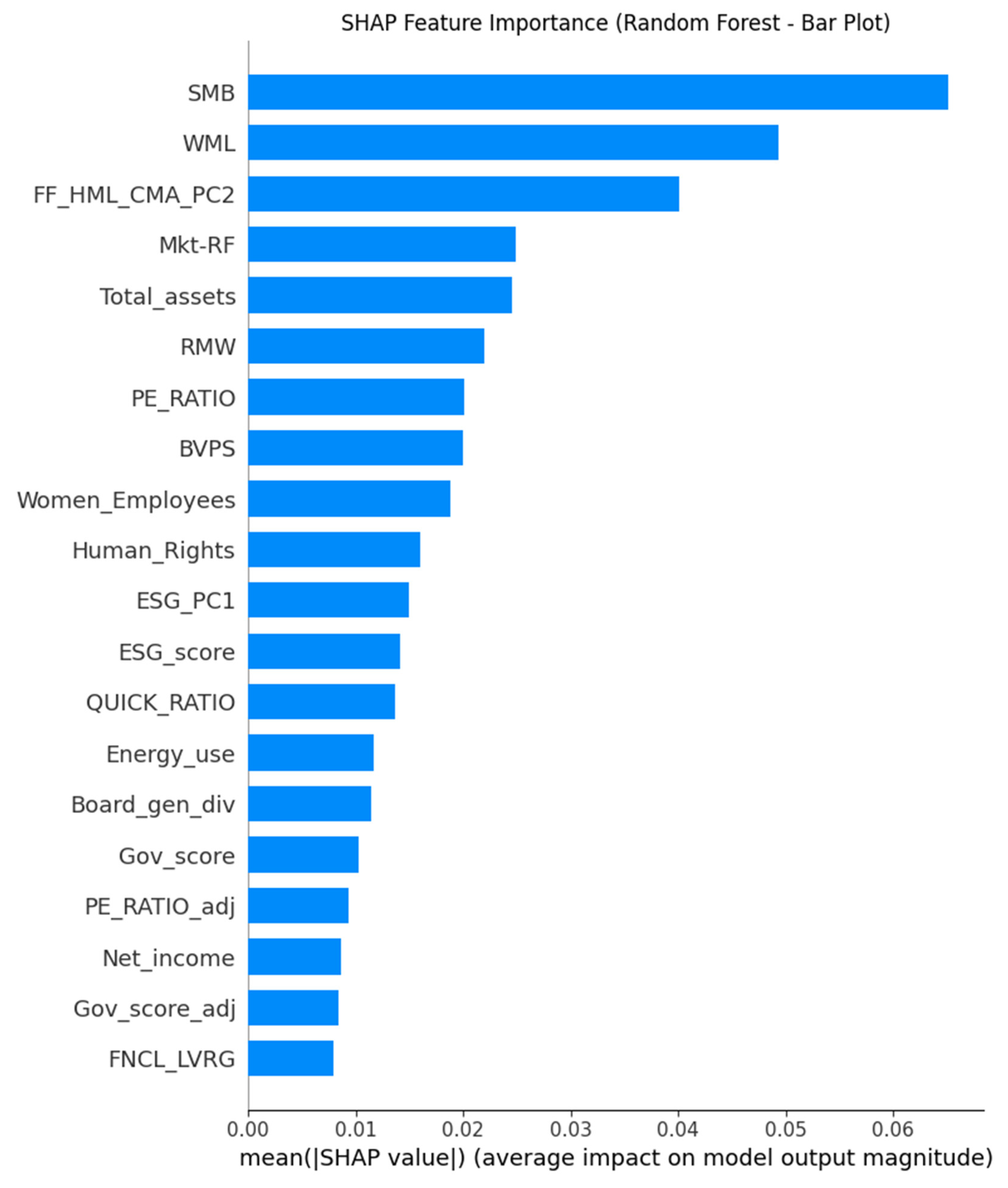

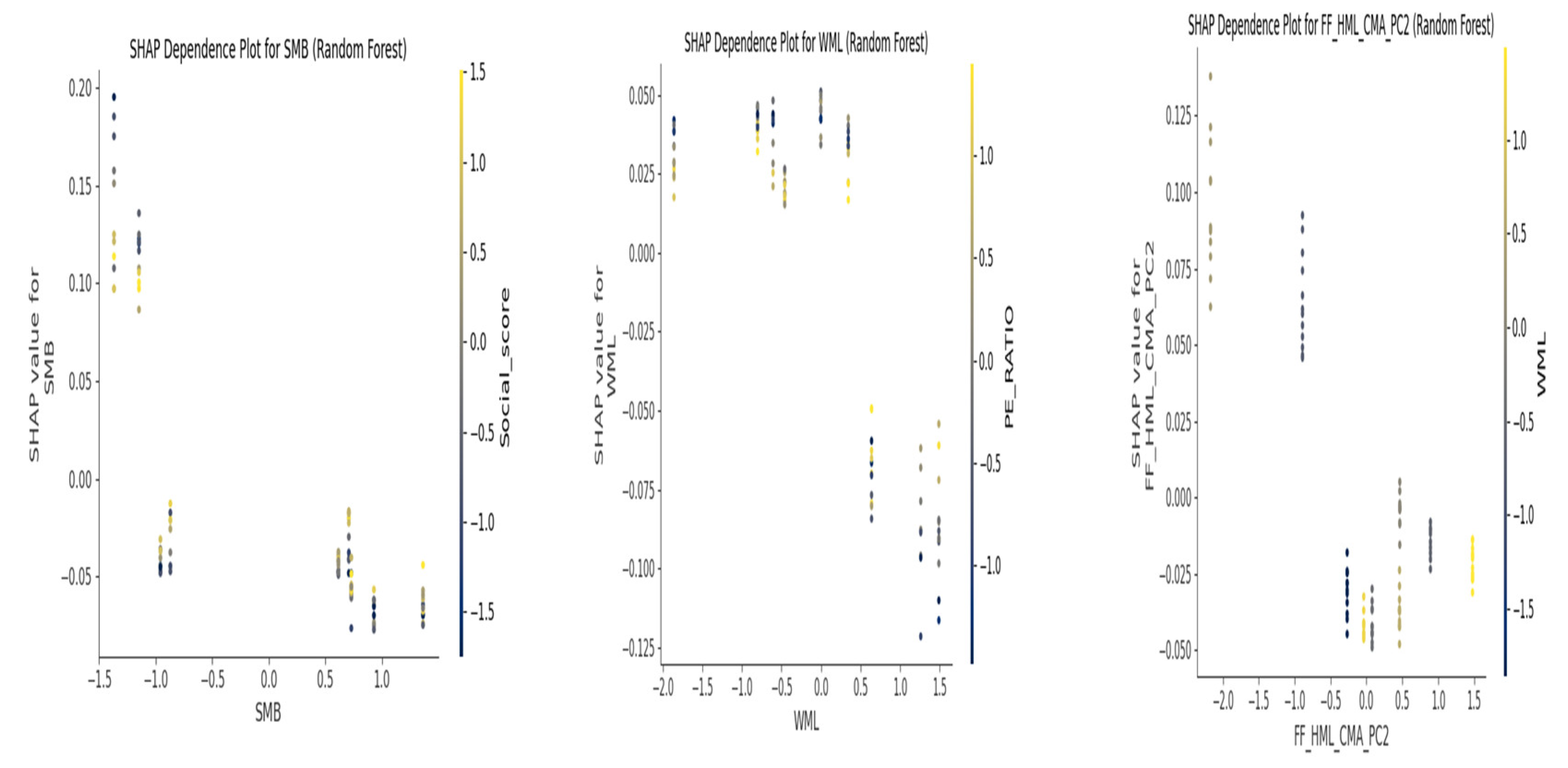

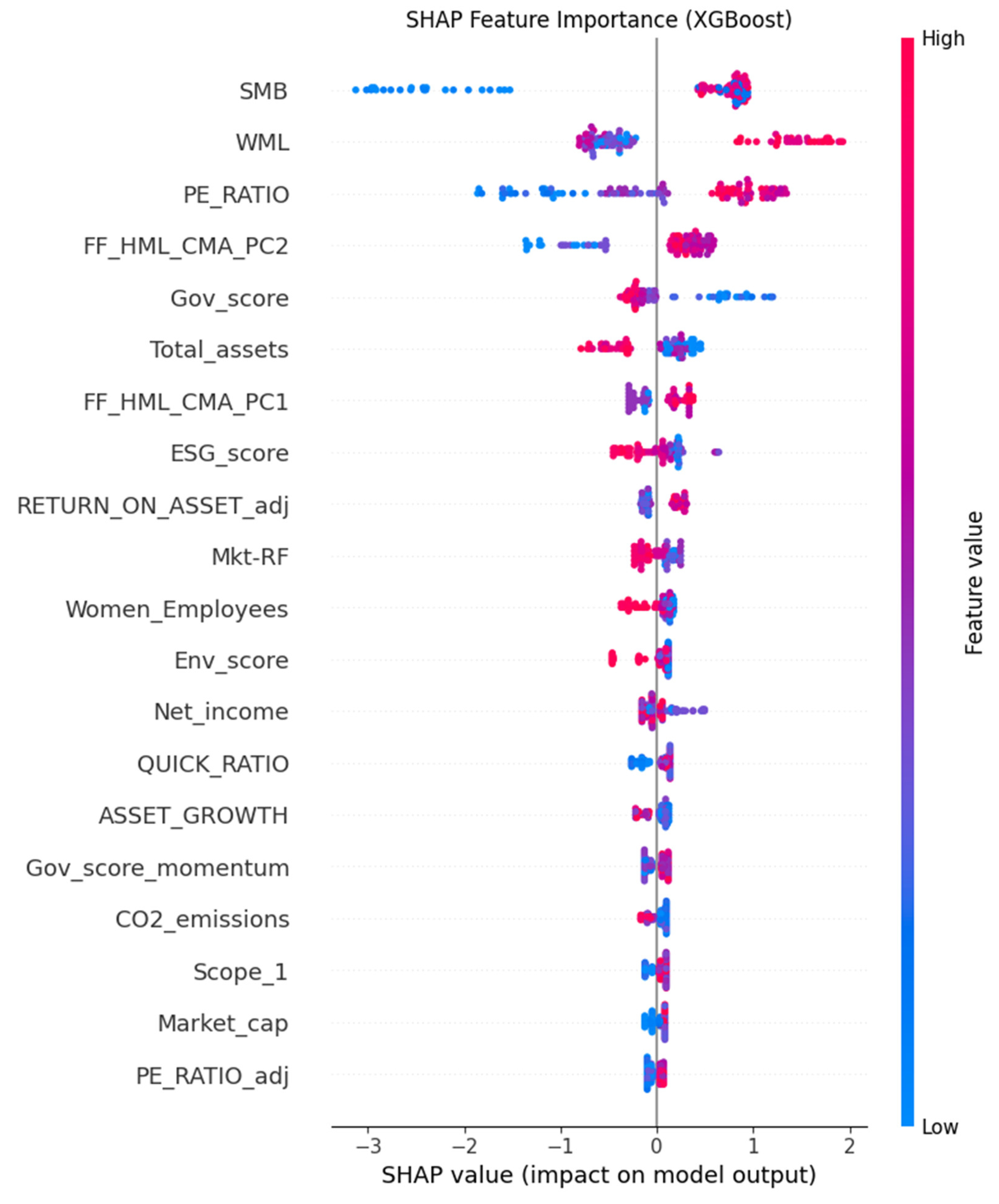

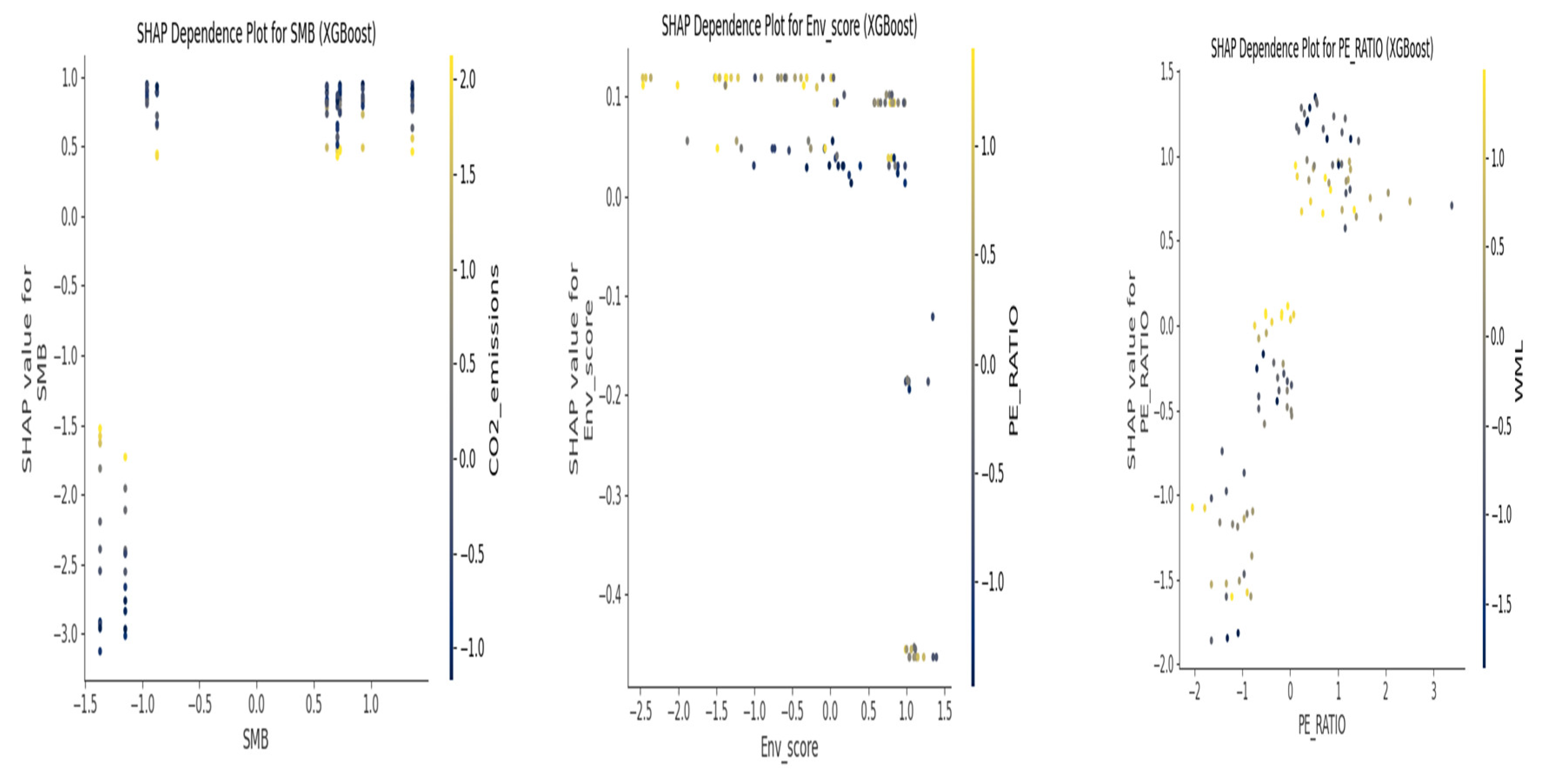

For Model Interpretability, Feature Importance was extracted globally from both Random Forest and XGBoost models, quantitatively ranking features by their predictive contribution and identifying influential predictors (Research Question 4). SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) Values provide model-agnostic local and global interpretability, quantifying each feature’s contribution to individual predictions and overall impact. SHAP summary plots (bar plots) visualized the overall impact and direction, while dependence plots for key features illustrated non-linear relationships and interactions, offering deeper insights.