Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Model and Methods

2.1. Governing Equations of Fluid

2.2. Particle Poiseuille Flow Through a Cylindrical Tube

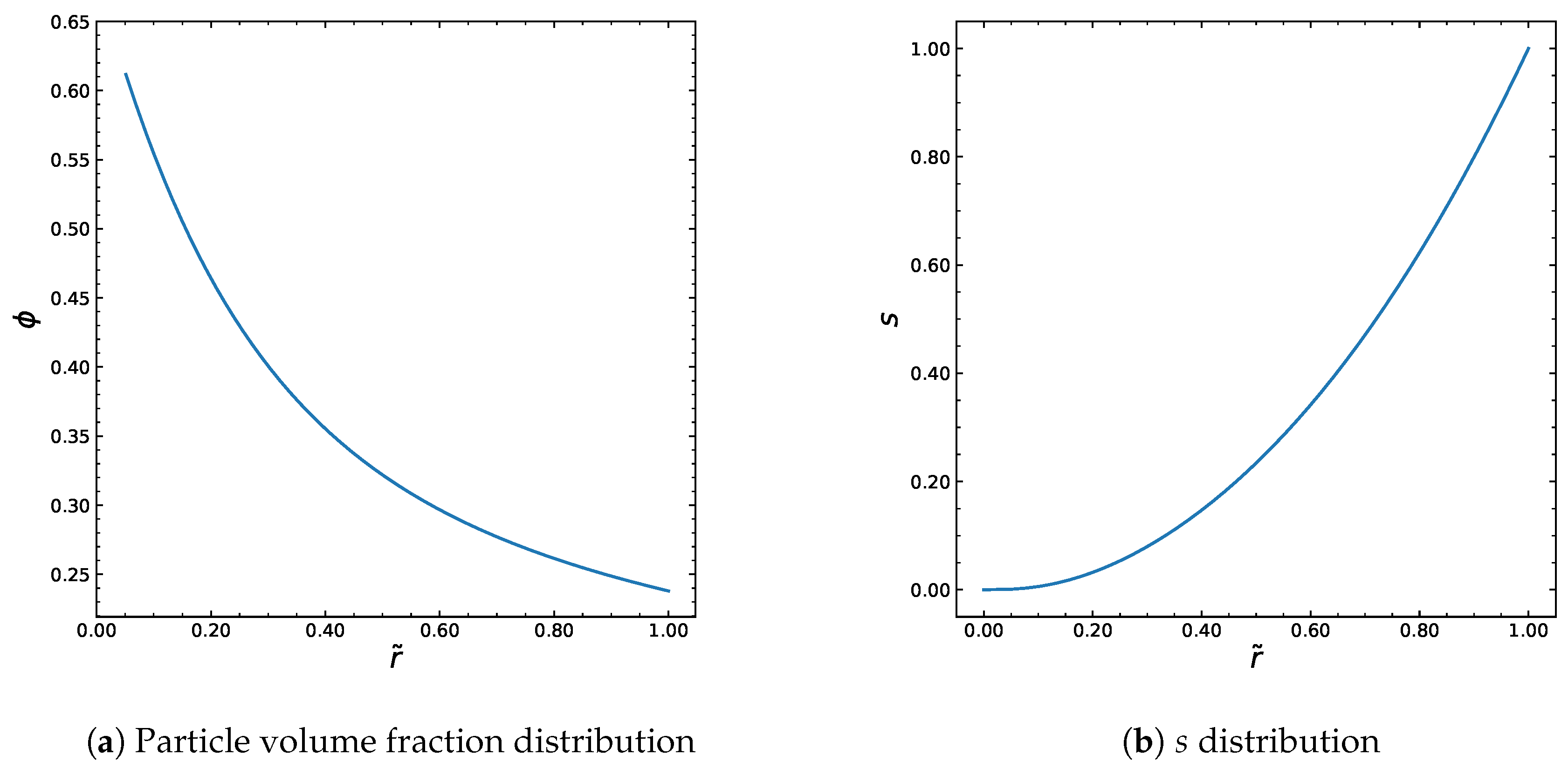

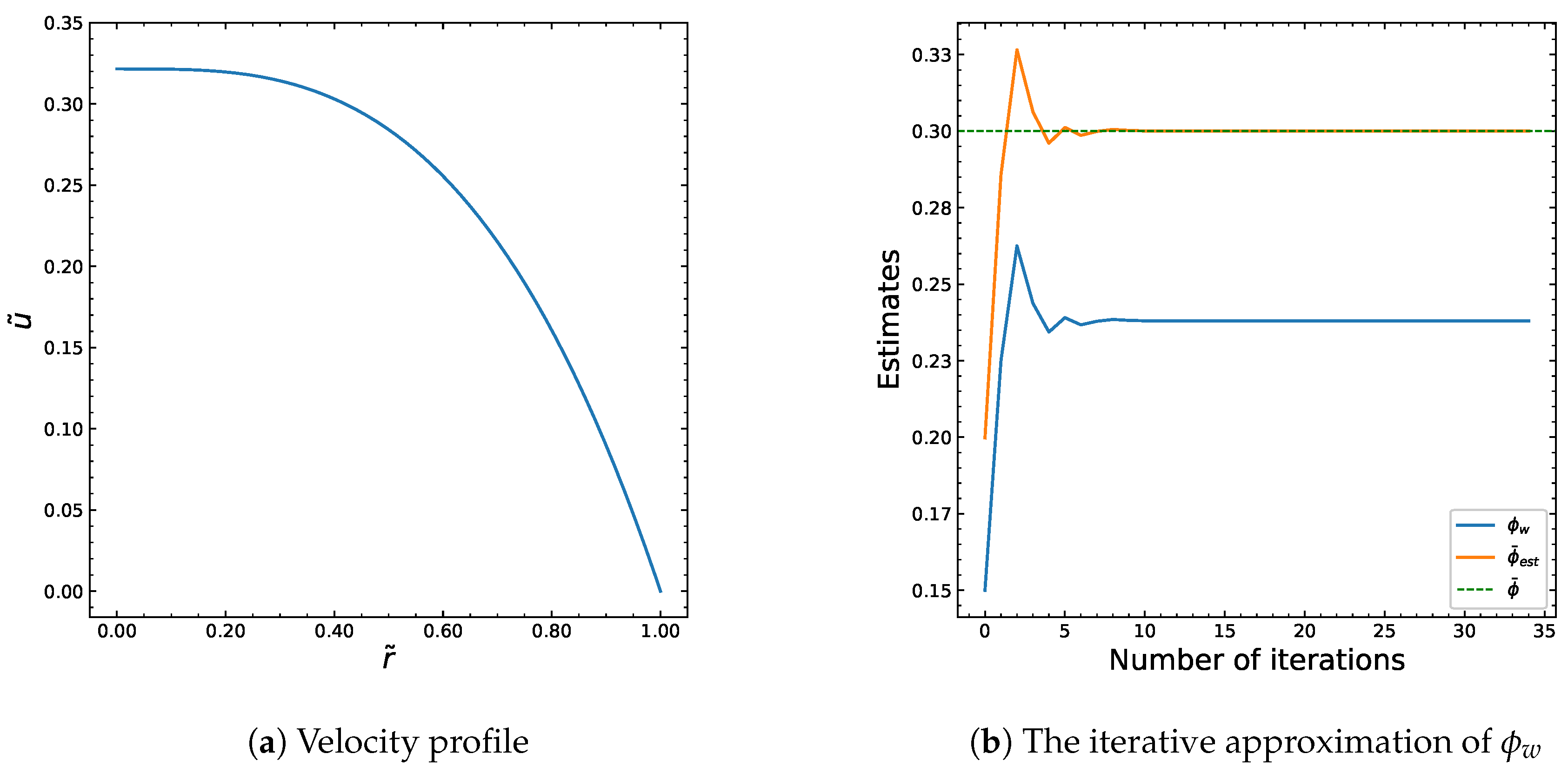

2.3. Steady State Velocity and Particle Distributions

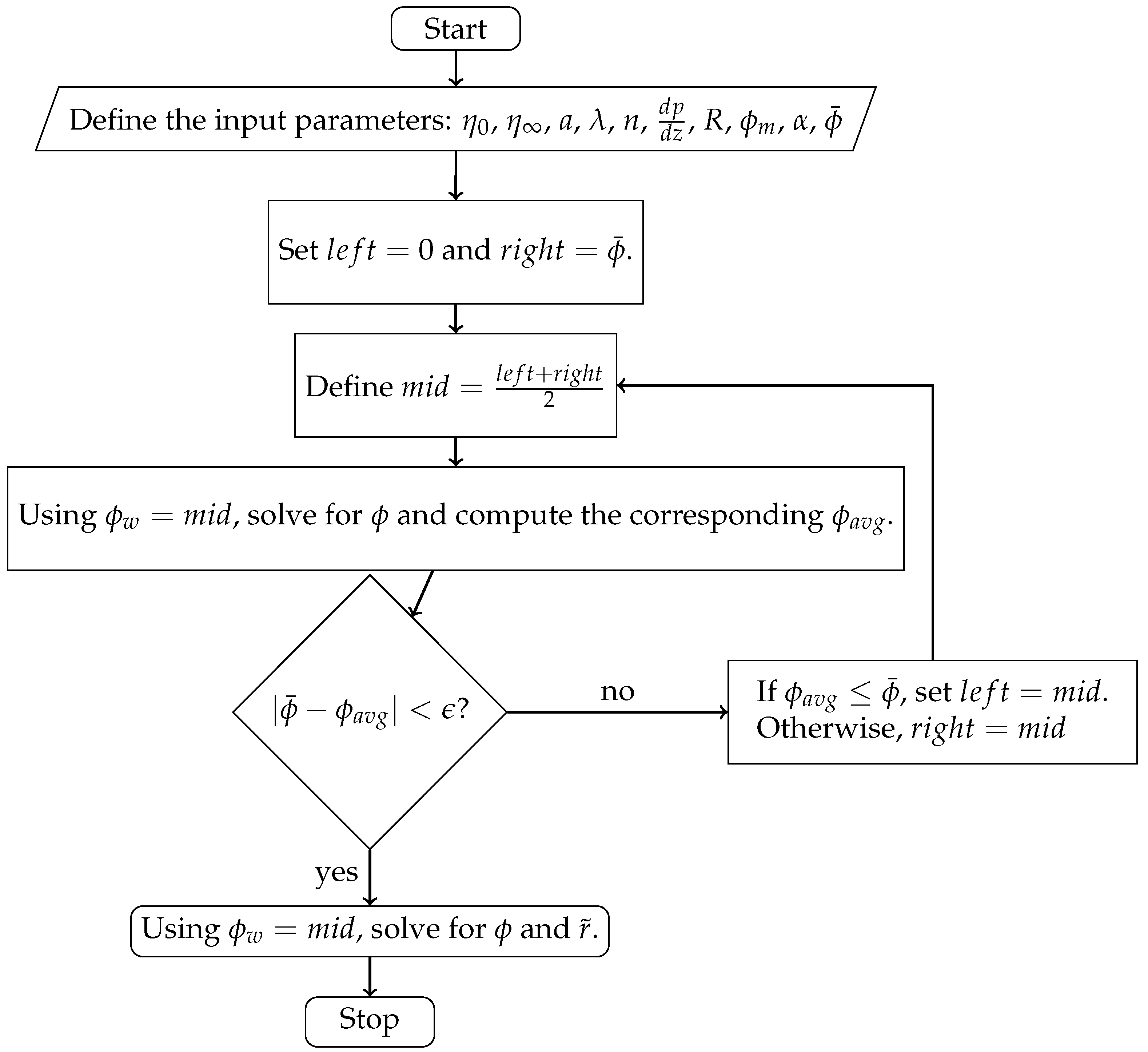

2.4. Nondimensionalization and Numerical Details

3. Results and Discussion

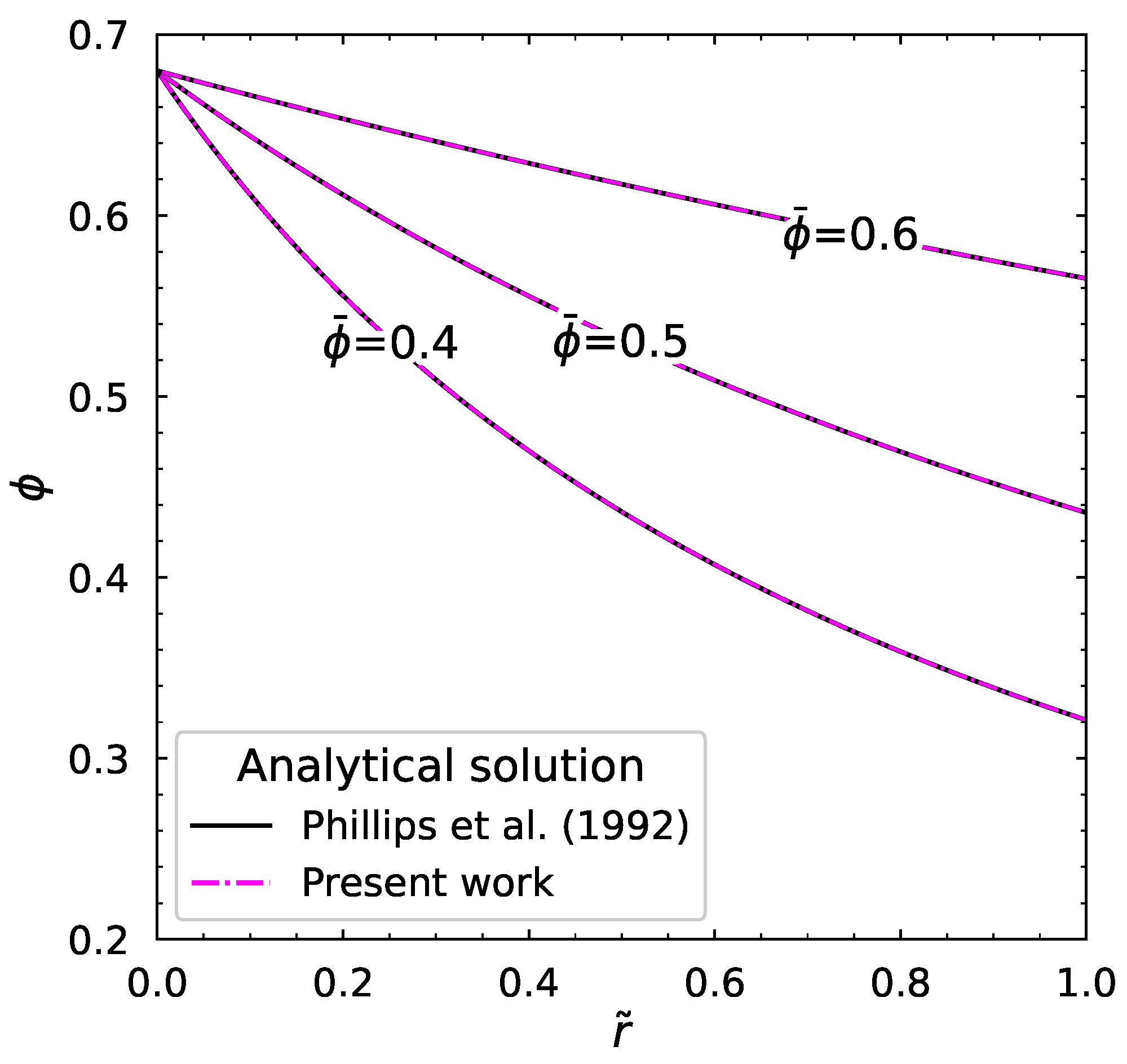

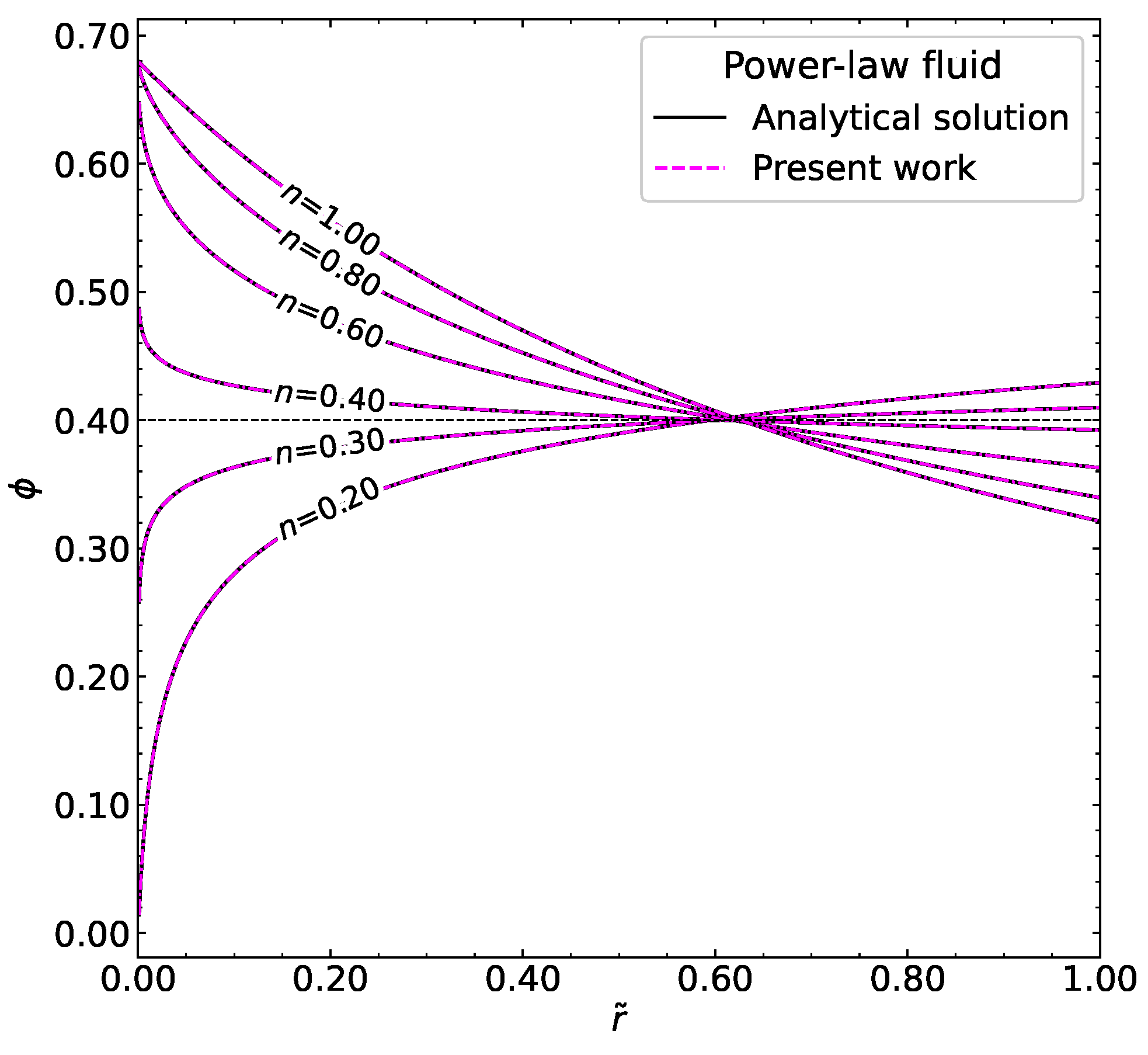

3.1. Verification and Validation of Numerical Results

3.1.1. Newtonian Fluid

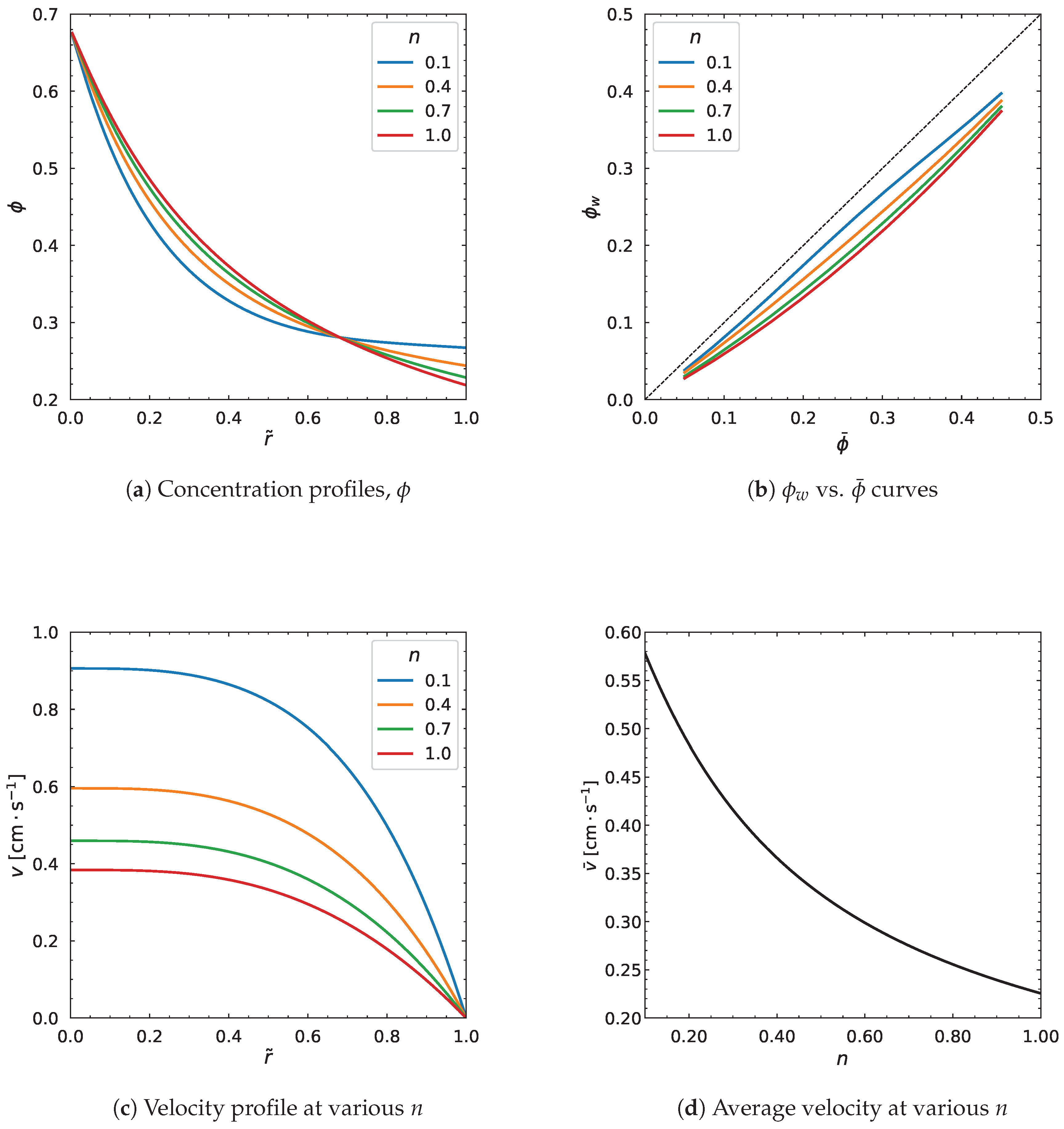

3.1.2. Power-Law Fluid

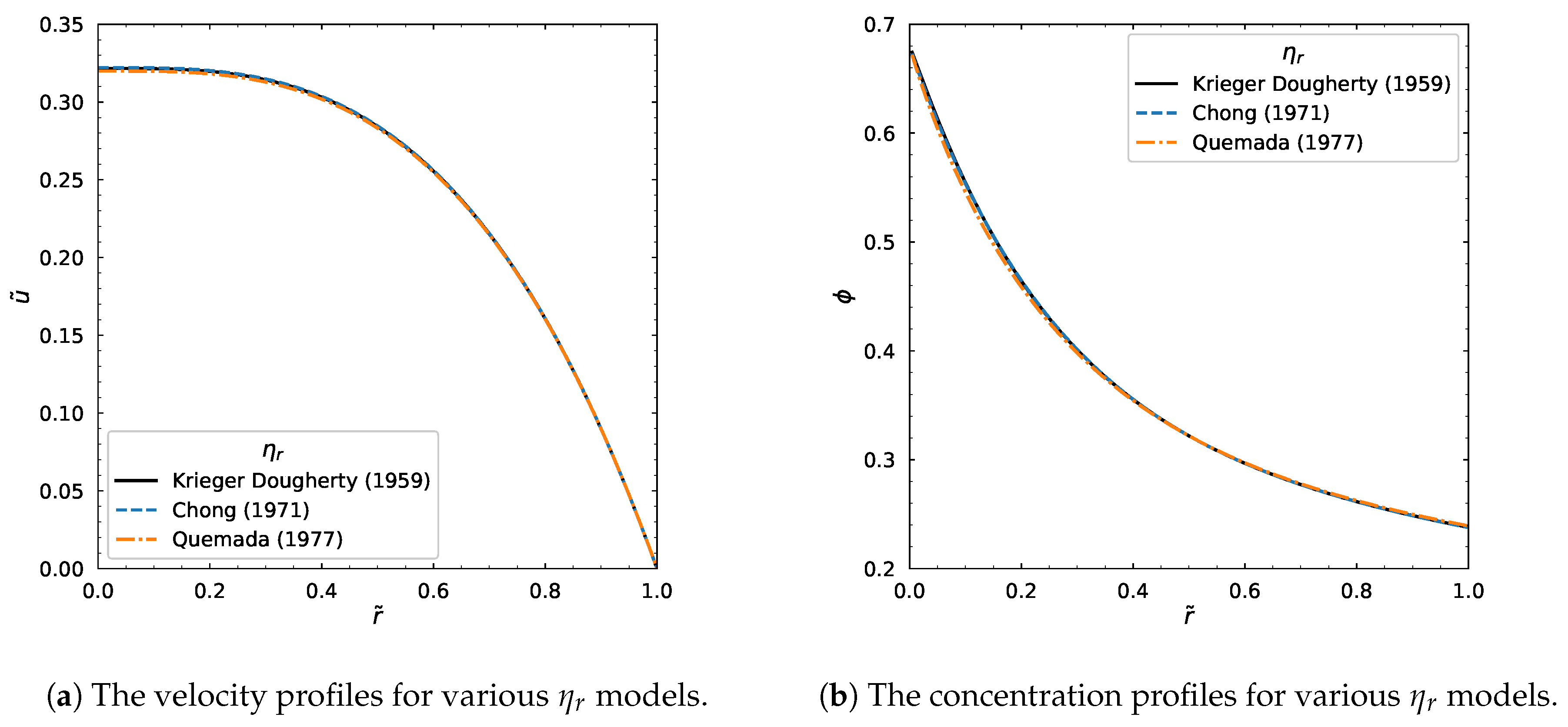

3.1.3. Other Relative Viscosity Models

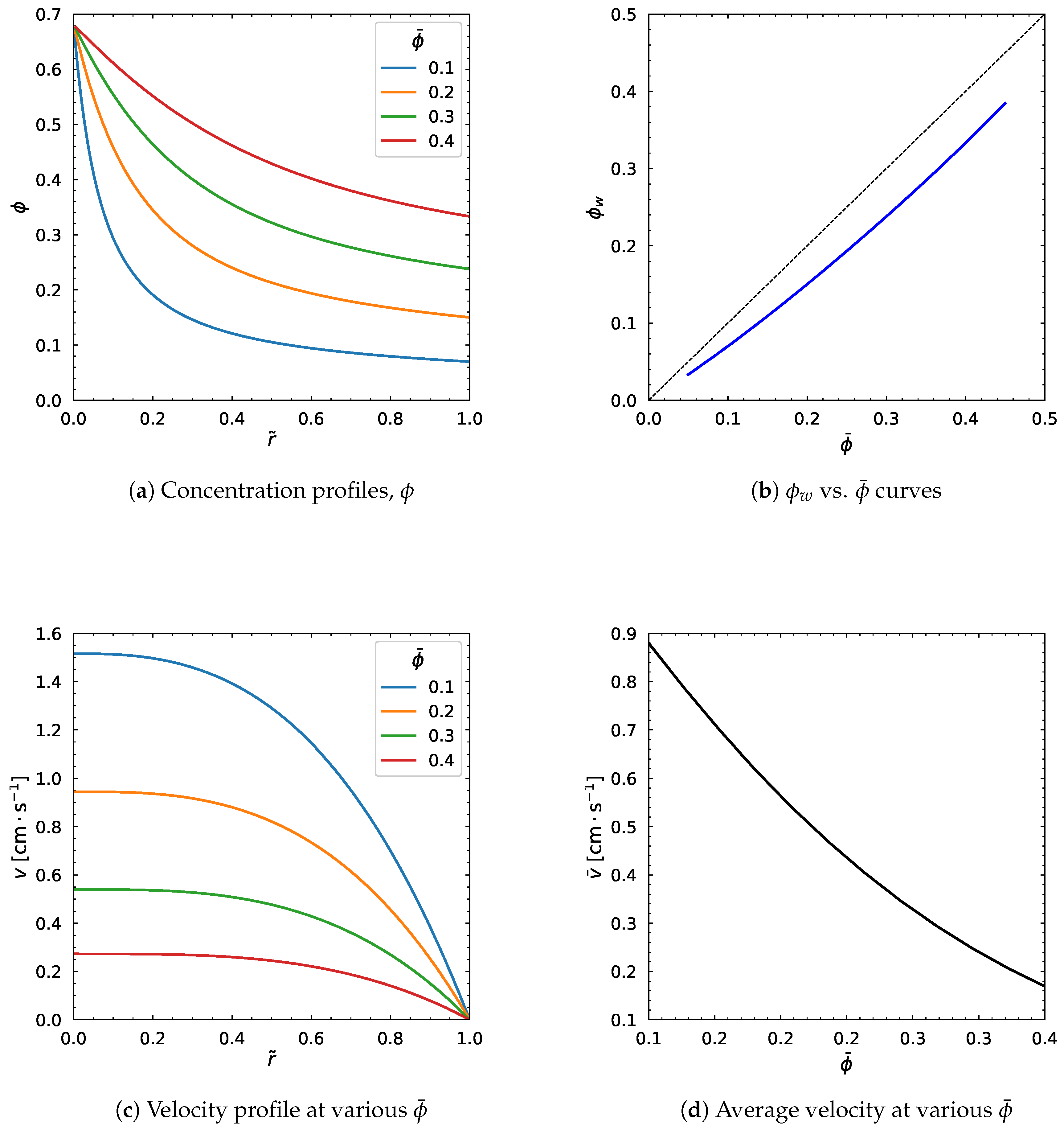

3.2. Influence of Average Particle Volume Fraction

3.3. Influence of Pressure Gradient

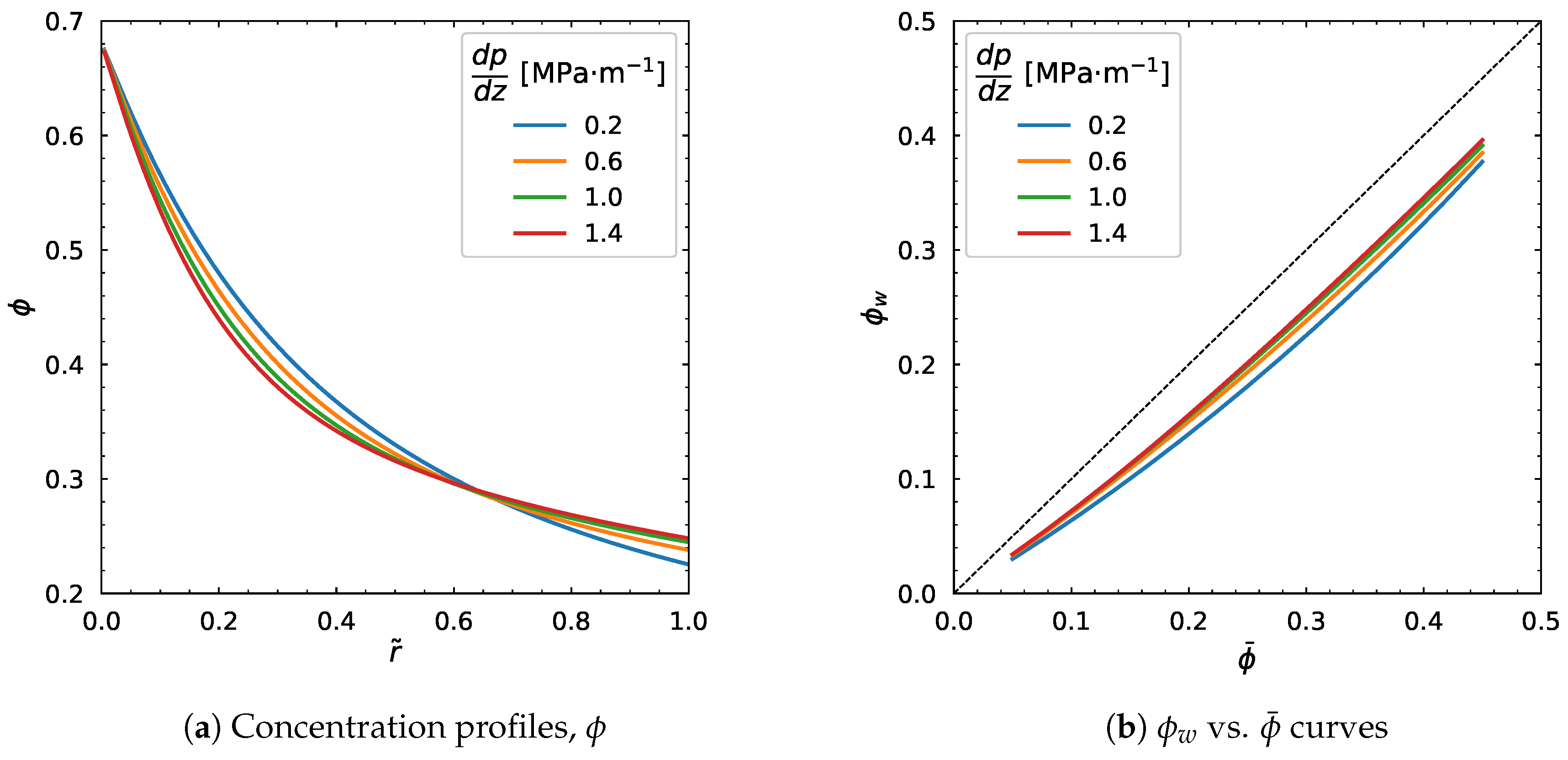

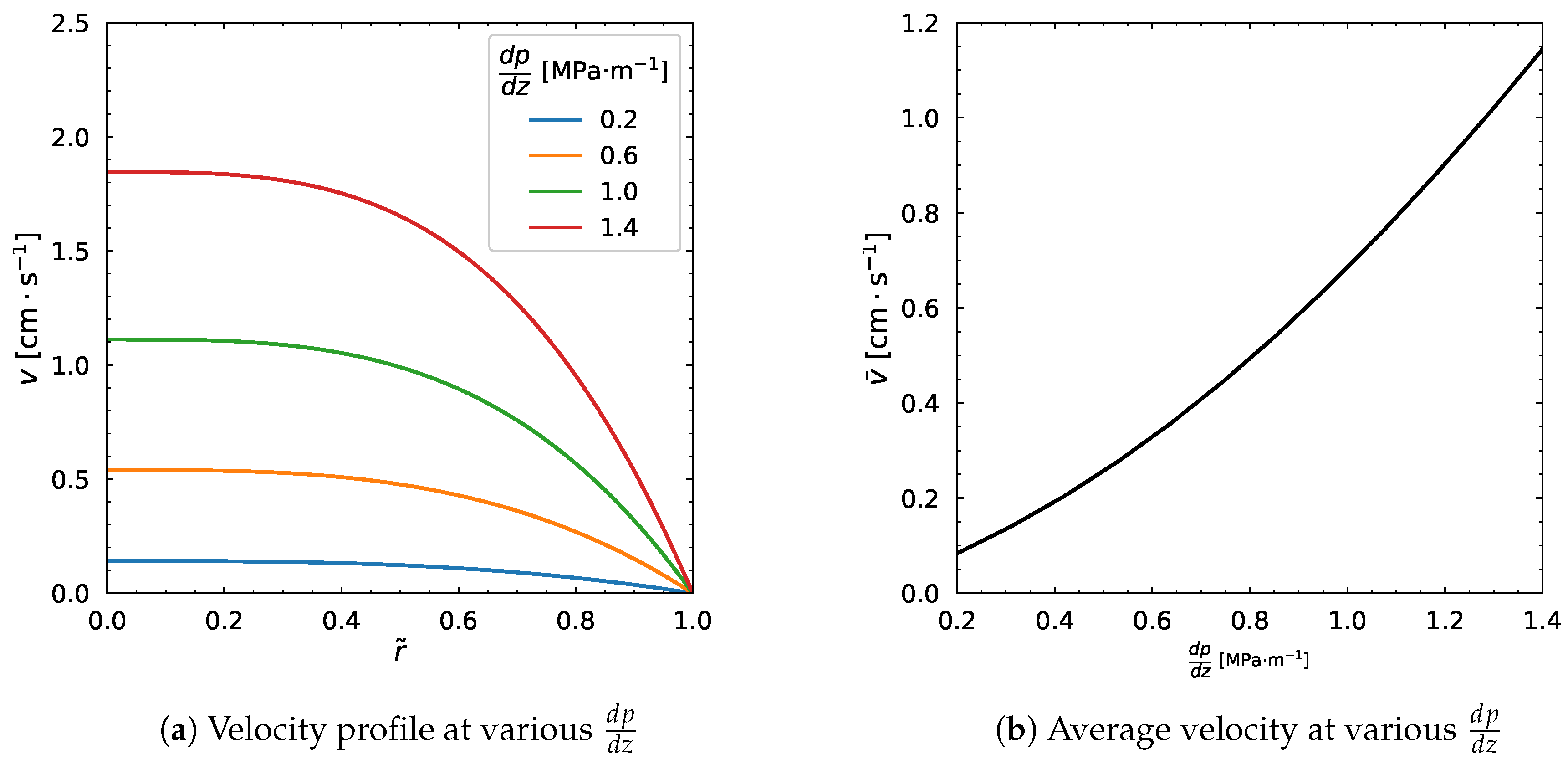

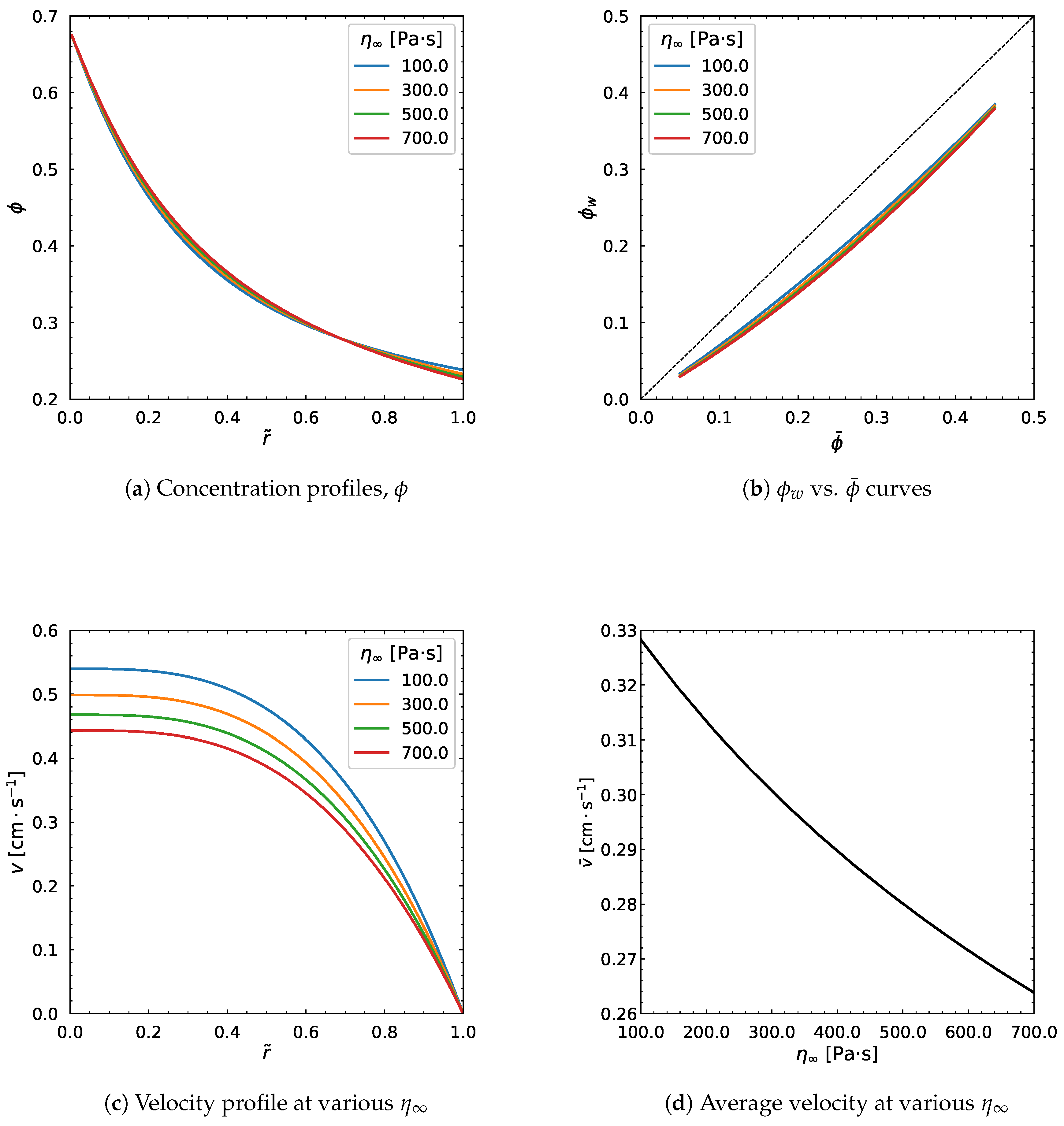

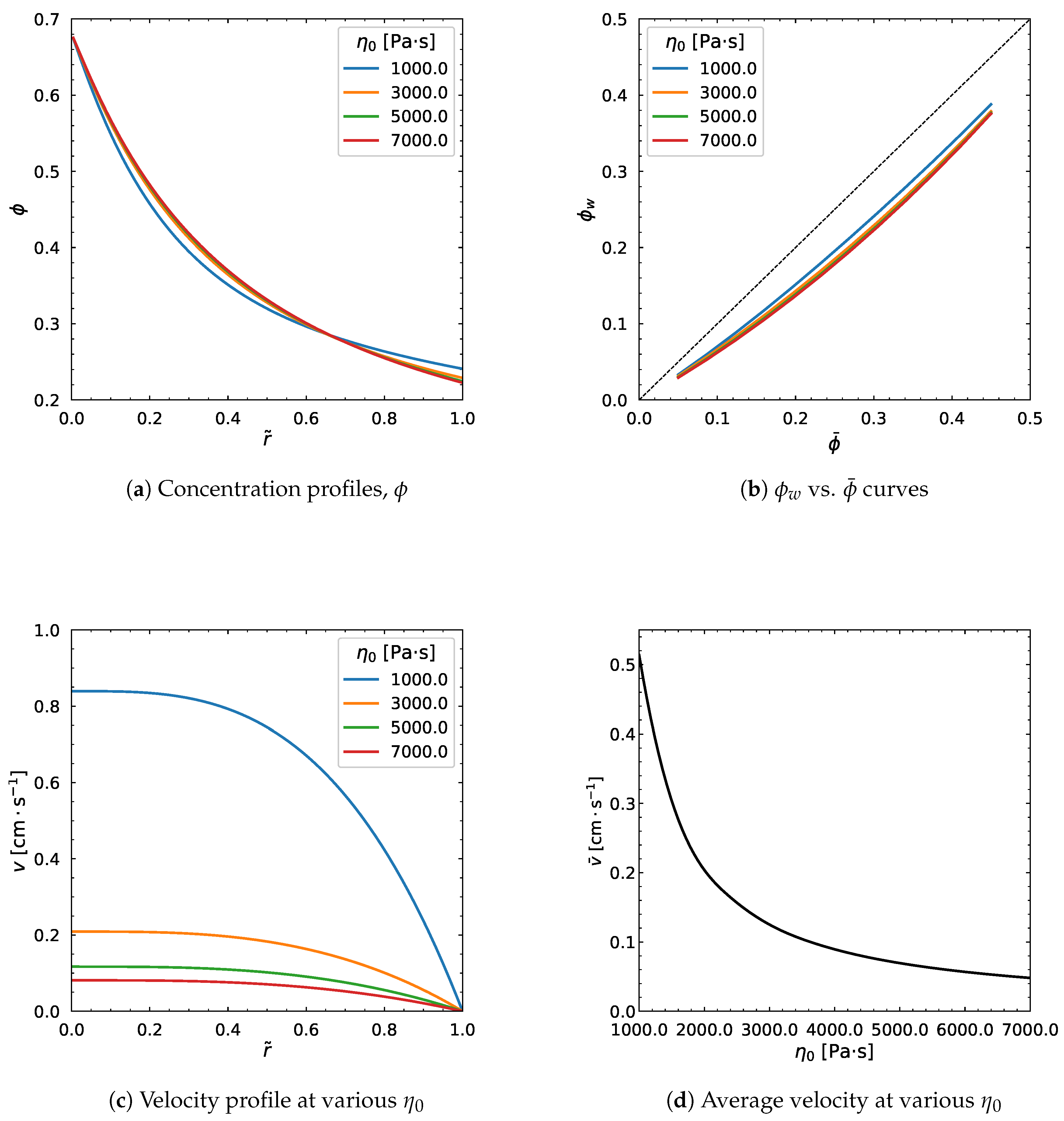

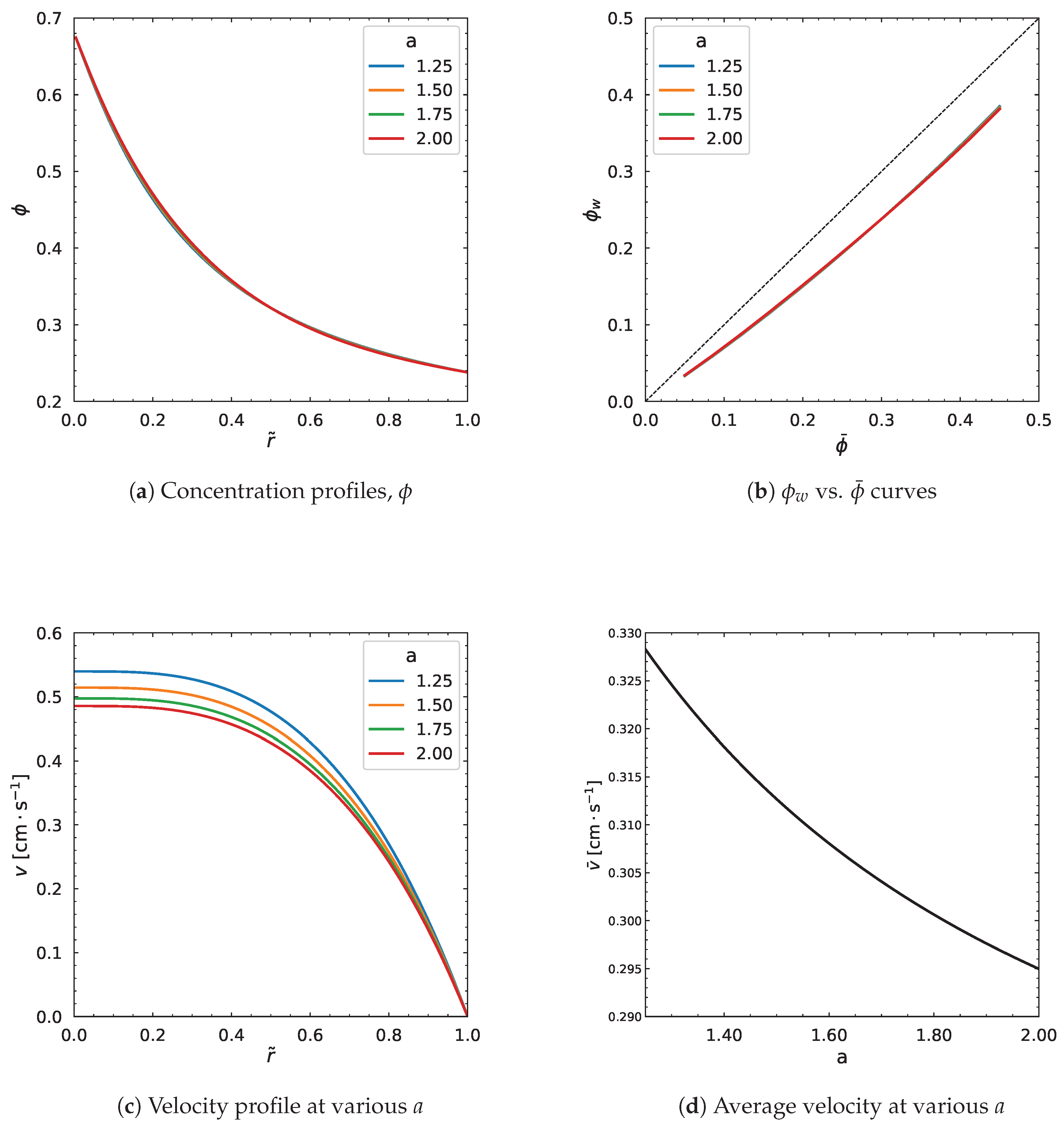

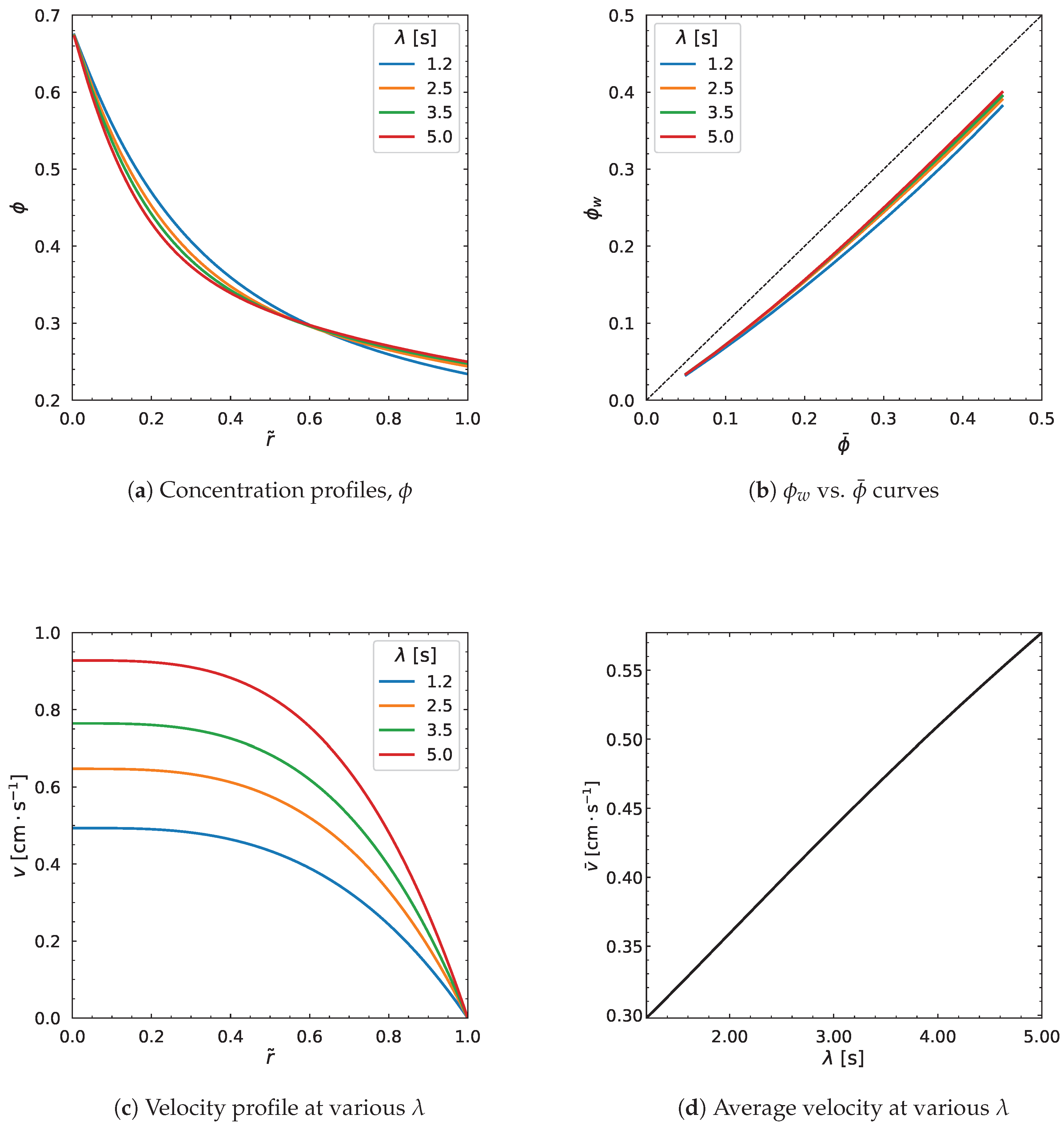

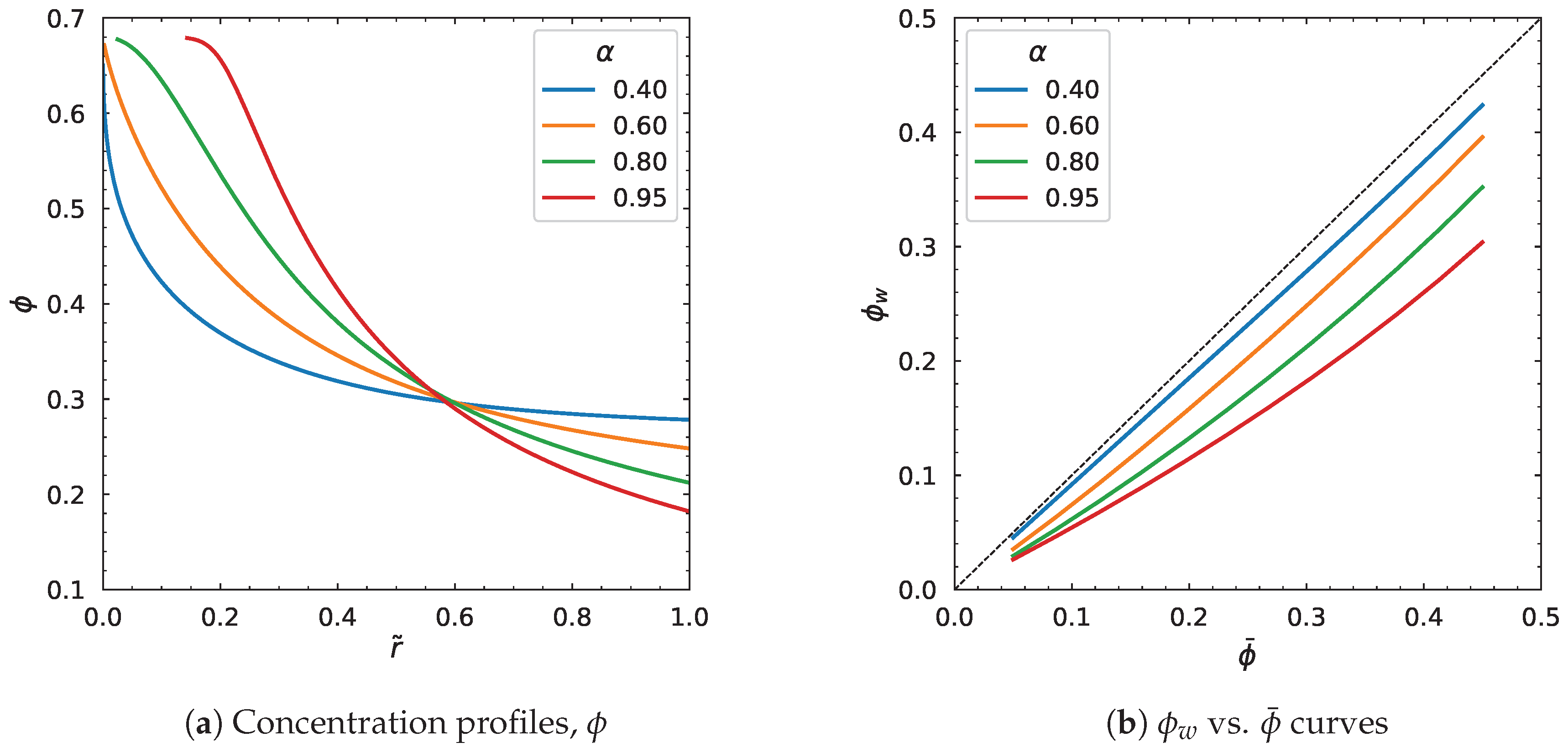

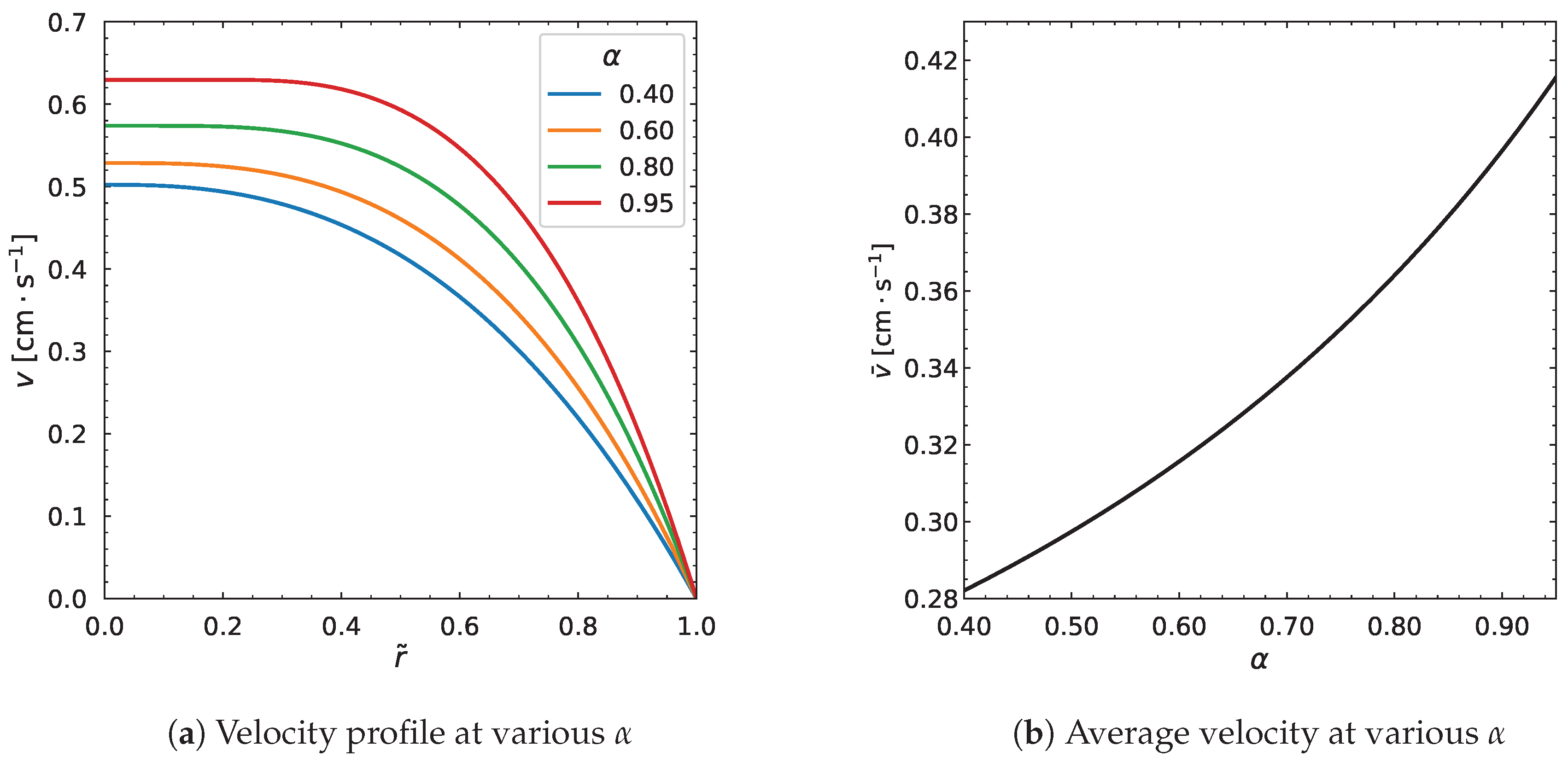

3.4. Influence of Carreau-Yasuda Parameters

3.5. Influence of Other Model Parameters

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

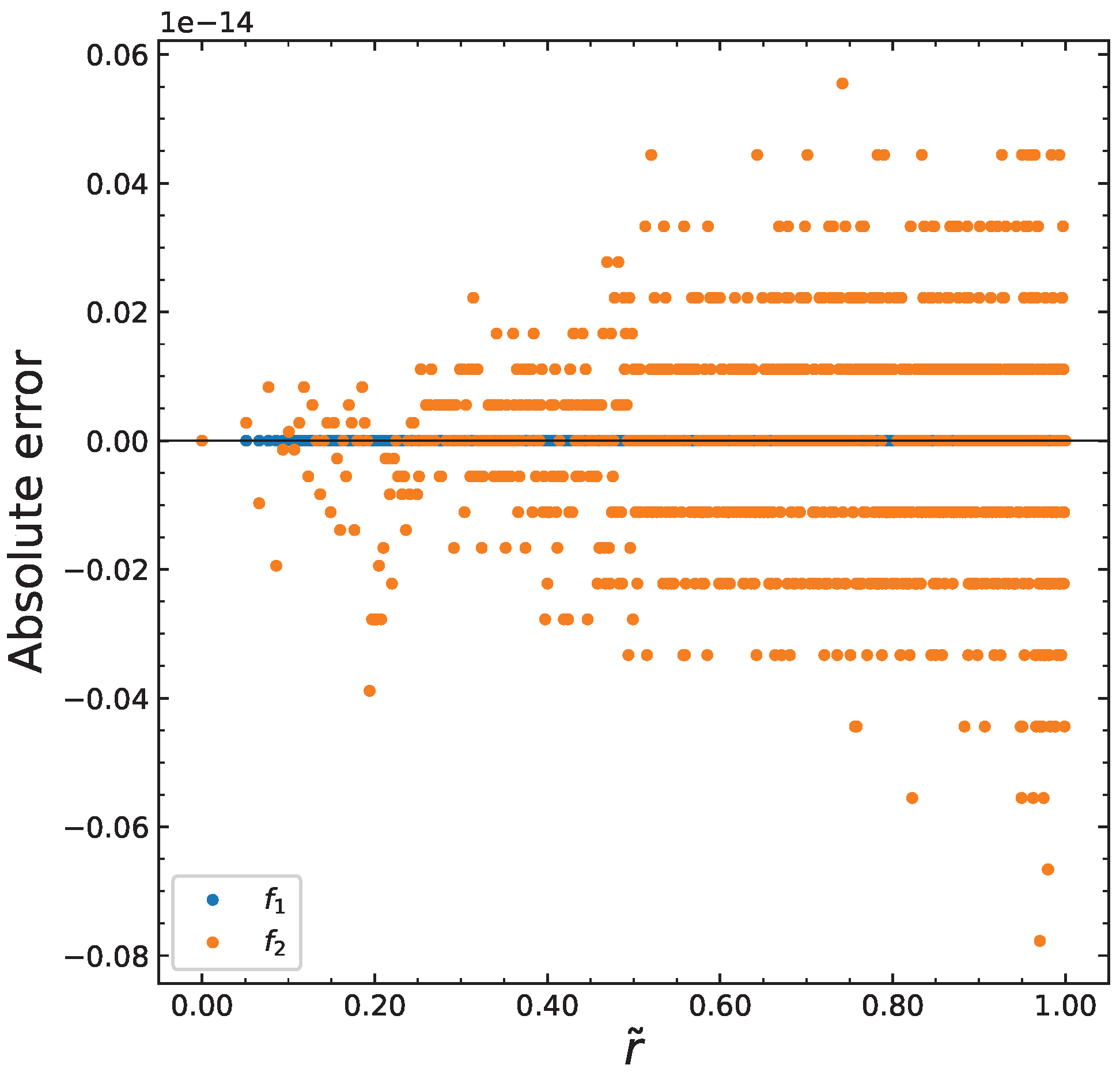

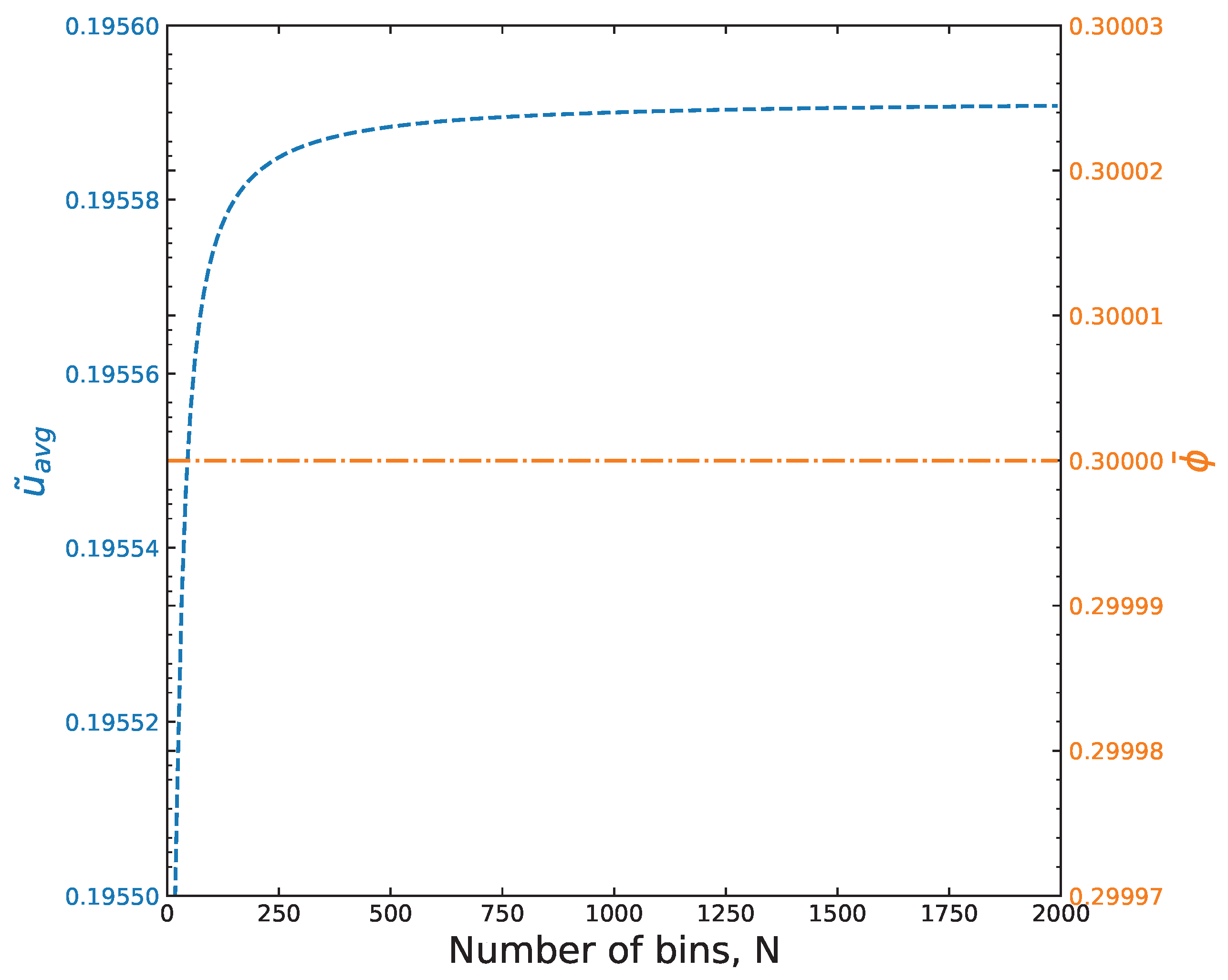

Appendix A. Function Error and Optimal Mesh Size in Numerical Computations

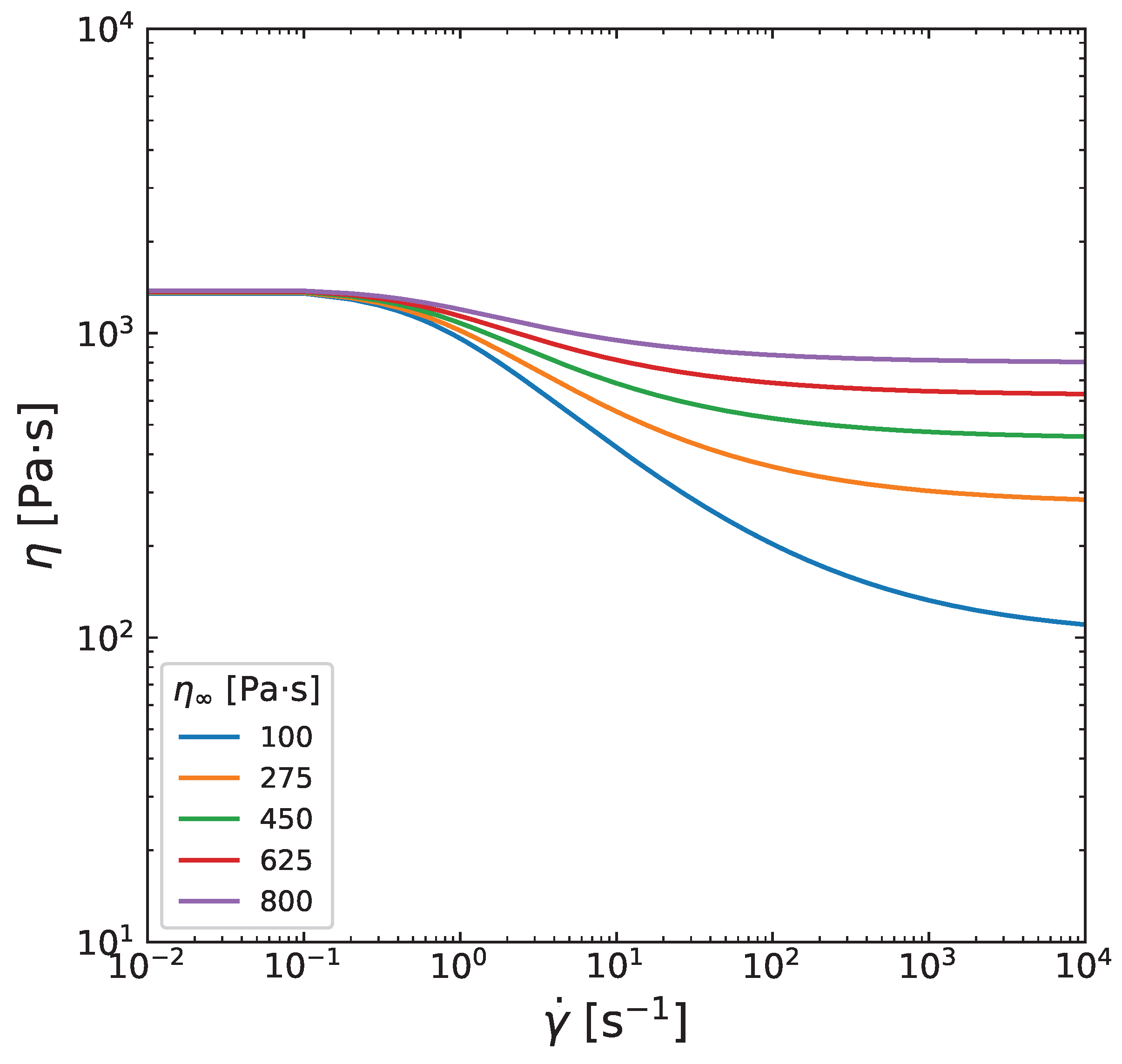

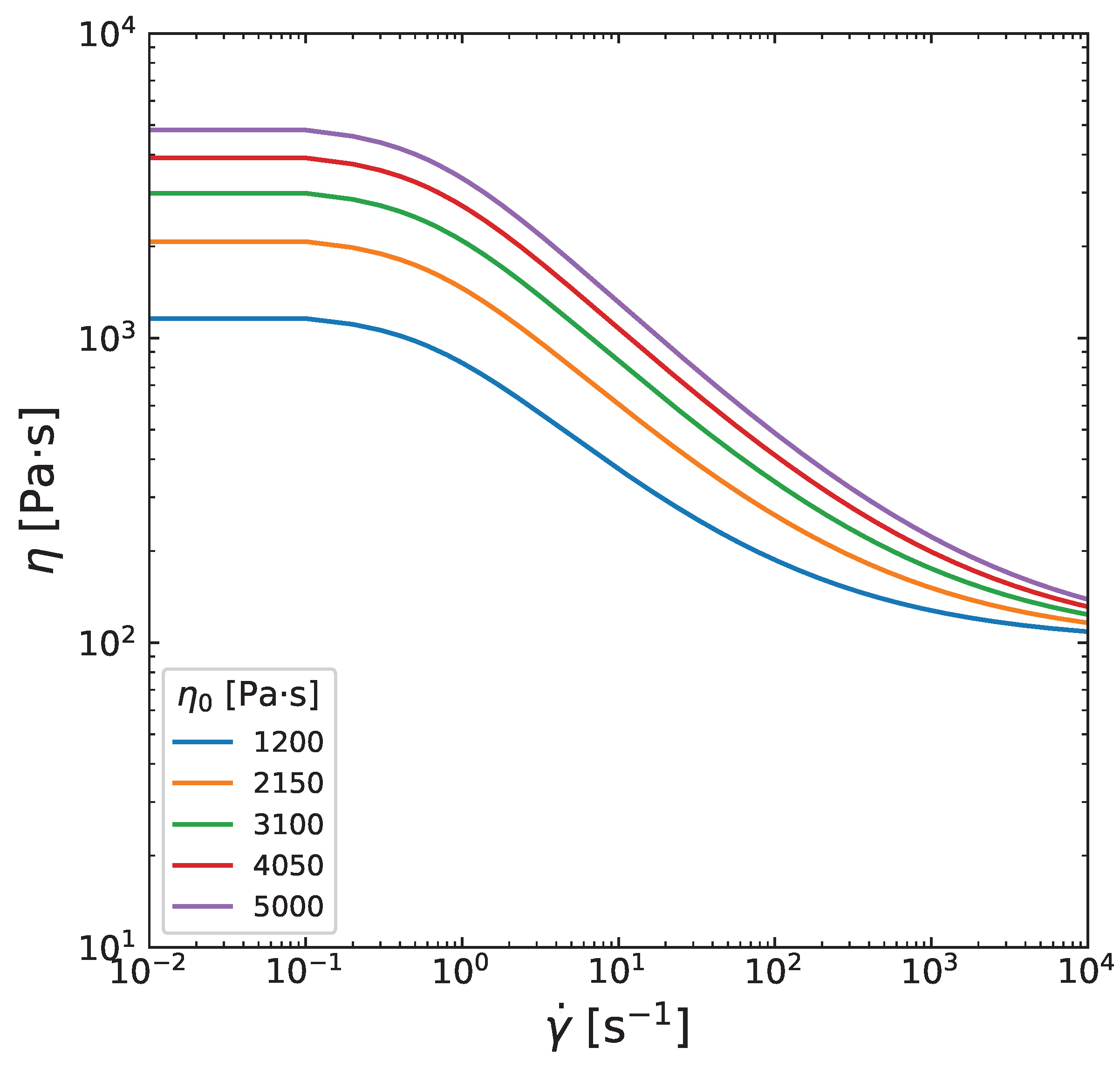

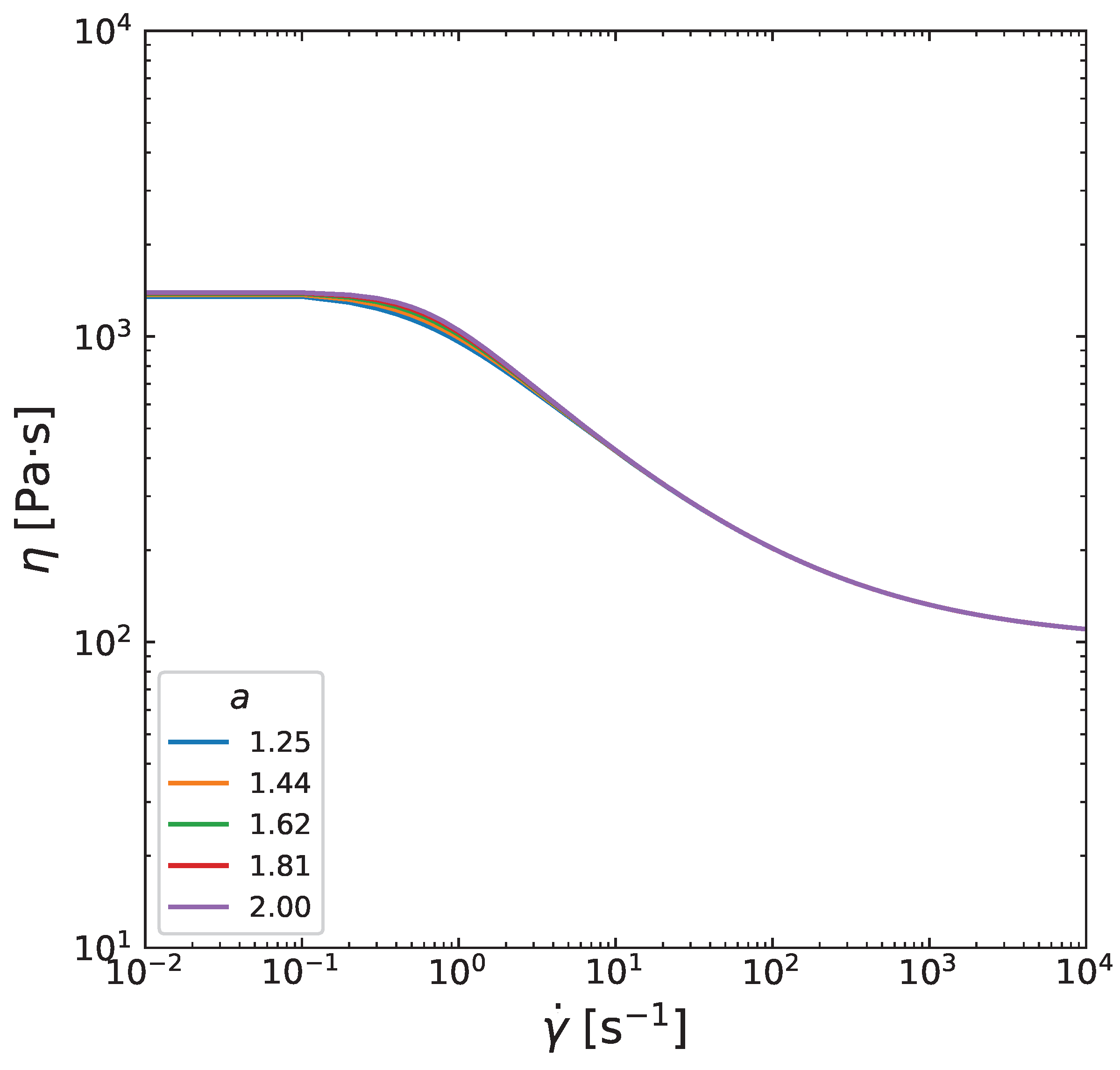

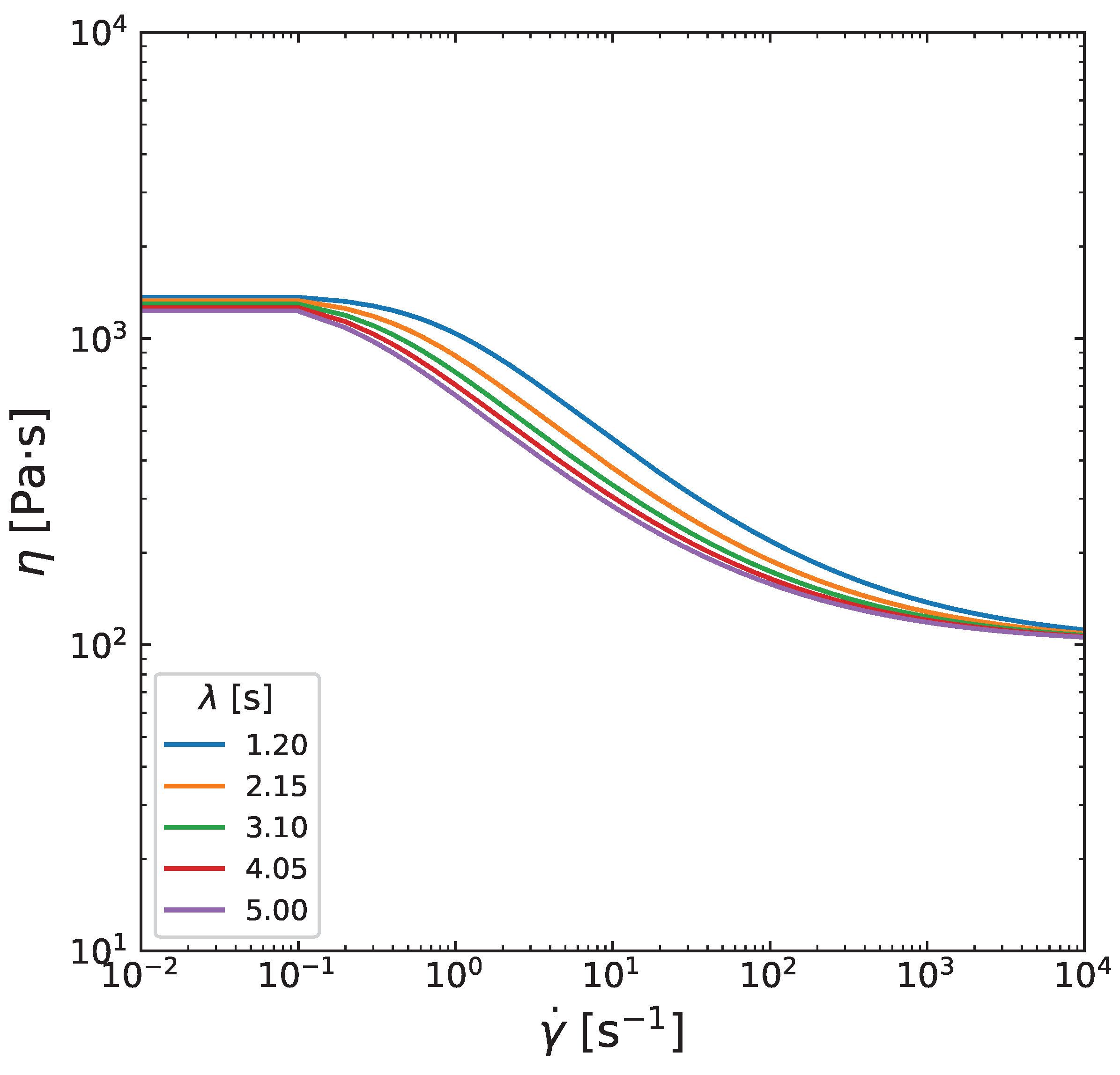

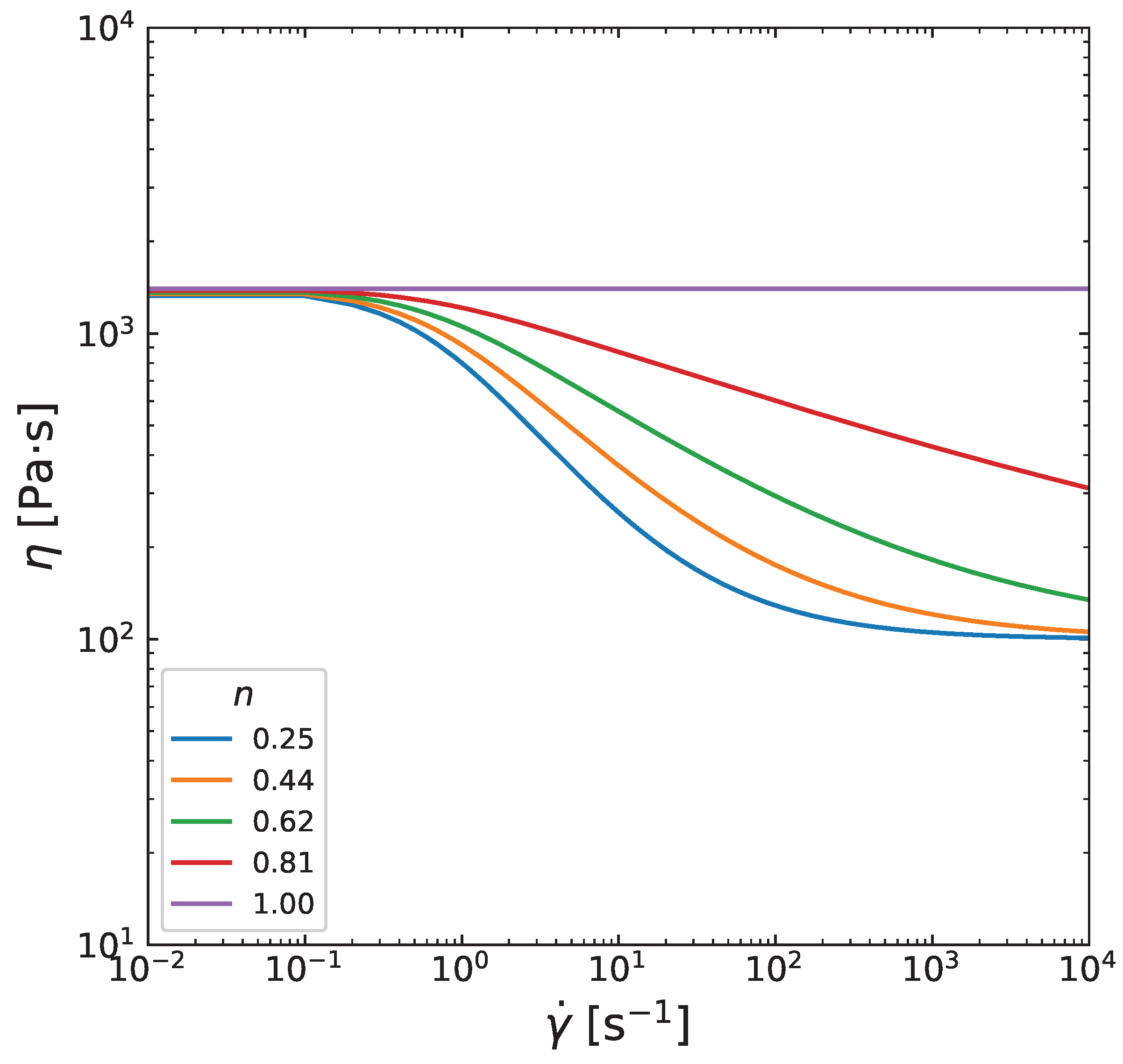

Appendix B. Influence of Carreau-Yasuda model parameters on viscosity

References

- Xie, X.; Zhang, L.; Shi, C.; Liu, X. Prediction of lubrication layer properties of pumped concrete based on flow induced particle migration. Construction and Building Materials 2022, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, M.; Auscher, M.; Fulchiron, R.; Périé, T.; Martin, G.; Sonntag, P.; Cassagnau, P. Rheology and applications of highly filled polymers: A review of current understanding. Progress in Polymer Science 2017, 66, 22–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, J.; Heckner, T.; Chrupala, A.; Pollock, J.; Goris, S.; Osswald, T. Experimental study of particle migration in polymer processing. Polymer Composites 2019, 40(6), 2165–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.D.; Hare, S.D.; Slater, P.R.; Simmons, M.J.H.; Kendrick, E. Rheology and Structure of Lithium-Ion Battery Electrode Slurries. Energy Technology 2022, 10, 2200545. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/ente.202200545]. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.; Lam, J.; Yang, L.; Kendrick, E. Extensional rheology of battery electrode slurries with water-based binders. Materials & Design 2022, 222, 111104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.; Armstrong, R.; Brown, R.; Graham, A.; Abbott, J. A Constitutive Equation for Concentrated Suspensions that Accounts for Shear- Induced Particle Migration. Physics of Fluids A: Fluid Dynamics 1992, 4(30), 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.; Armstrong, R.; Hassager, O. Dynamics of polymeric liquids. Volume 1., 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Tan, K.; Lam, Y.; Chai, J. The Transverse Particle Migration of Highly Filled Polymer Fluid Flow in a Pipe. Innovation in Manufacturing Systems and Technology (IMST) 2003. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/3757.

- Chen, X.; Lam, Y.; Tan, K.; Chai, J.; Yu, S. Shear-Induced Particle Migration modelling in a concentrated suspension flow. Modelling Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2003, 11(4), 503–522. Available at https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0965-0393/11/4/307. [CrossRef]

- Cebeci, T. Convective heat transfer., 2nd ed.; Springer-Verlag Berlin and Heidelberg GmbH & Co. KG: Berlin, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Steady isothermal flow of a Carreau–Yasuda model fluid in a straight circular tube. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2022, 310, 104937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, S. Prediction on pipe flow of pumped concrete based on shear-induced particle migration. Cement and Concrete Research 2013, 52, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, I.; Carvalho, M. Particle migration in planar die-swell flows. J. Fluid Mech. 2017, 825, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.B.Rebouças.; Siqueira, I.; de Souza Mendes, P.; Carvalho, M. On the pressure-driven flow of suspensions: Particle migration in shear sensitive liquids. Journal of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics 2016, 234, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, M. Rheology and processing of highly filled materials. Materials. Universite de Lyon 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, I.; Dougherty, T. A Mechanism for Non-Newtonian Flow in Suspensions of Rigid Spheres. Transactions of the Society of Rheology 1959, 3(137). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.S. Chong, E.C.; Baer, A. Rheology of concentrated Suspensions. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 1971, 15, 2007–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quemada, D. Rheology of concentrated disperse systems and minimum energy dissipation principle. Rheologica Acta 1977, 16, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghiyadaki, A.; Wei, D.; Perveen, A.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y. Effects of Melt Temperature and Non-Isothermal Flow in Design of Coat Hanger Dies Based on Flow Network of Non-Newtonian Fluids. Polymers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | (Pa·s) | (Pa·s) | a | (s) | n | (MPa/m) | R (m) | |||

| 1400 | 100 | 1.25 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).