Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Equations of the Present Model

2.1. General Equations of the Model with Particle Migration

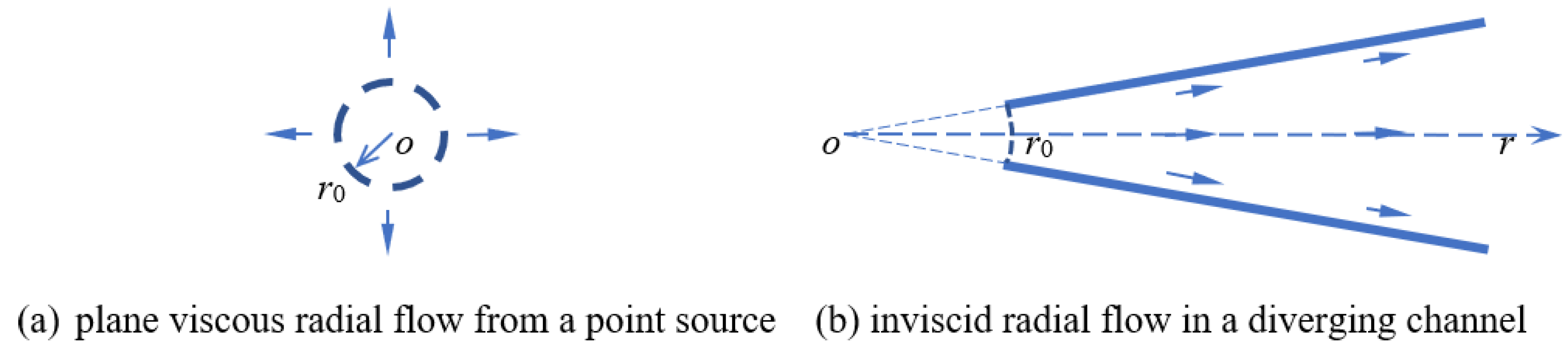

2.2. Equations for Steady Plane Radial Flow

3. Initial Velocity Field with the Uniform Particle Distribution

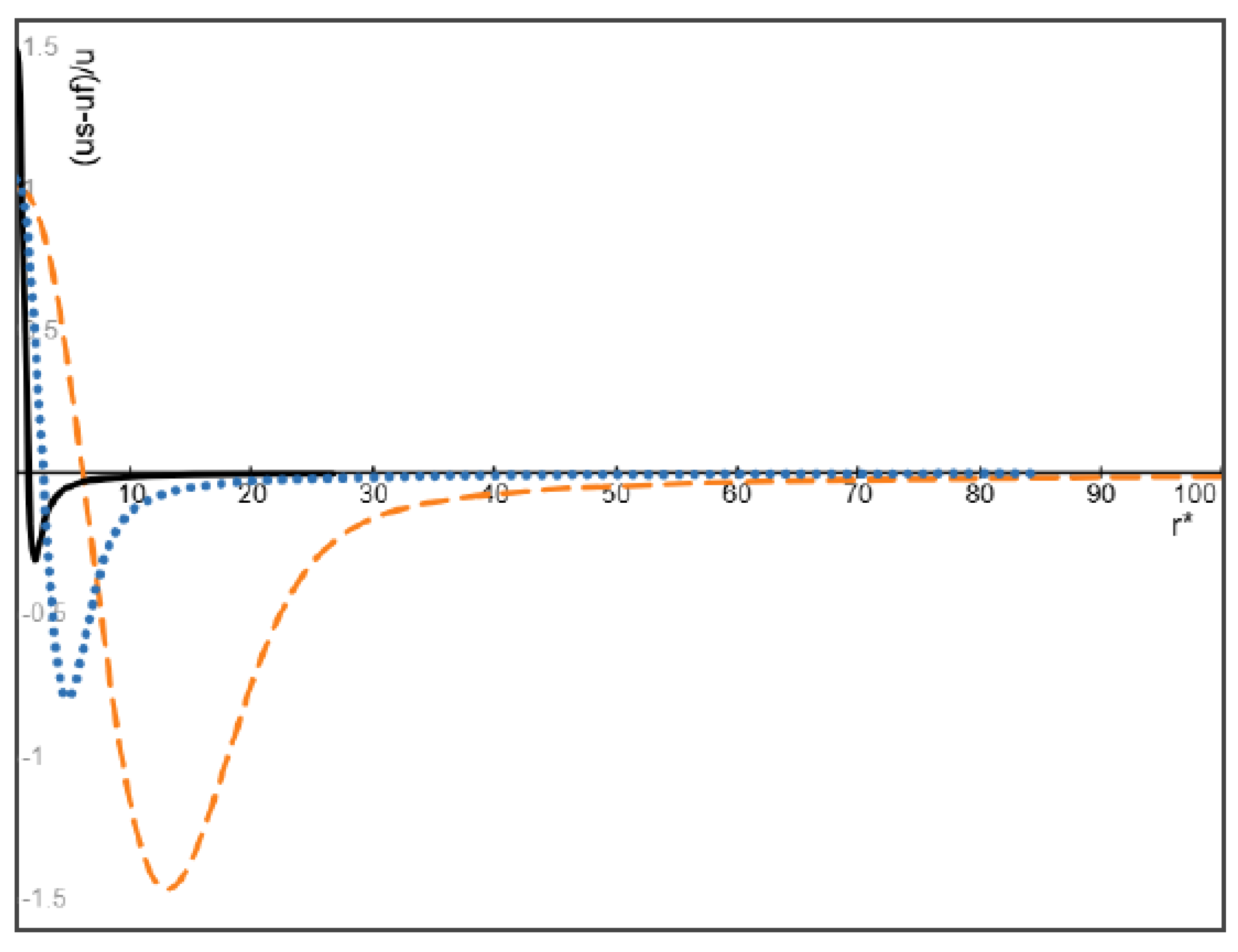

3.1. Lighter Particles with Higher Inlet Velocity (u0S>u0f)

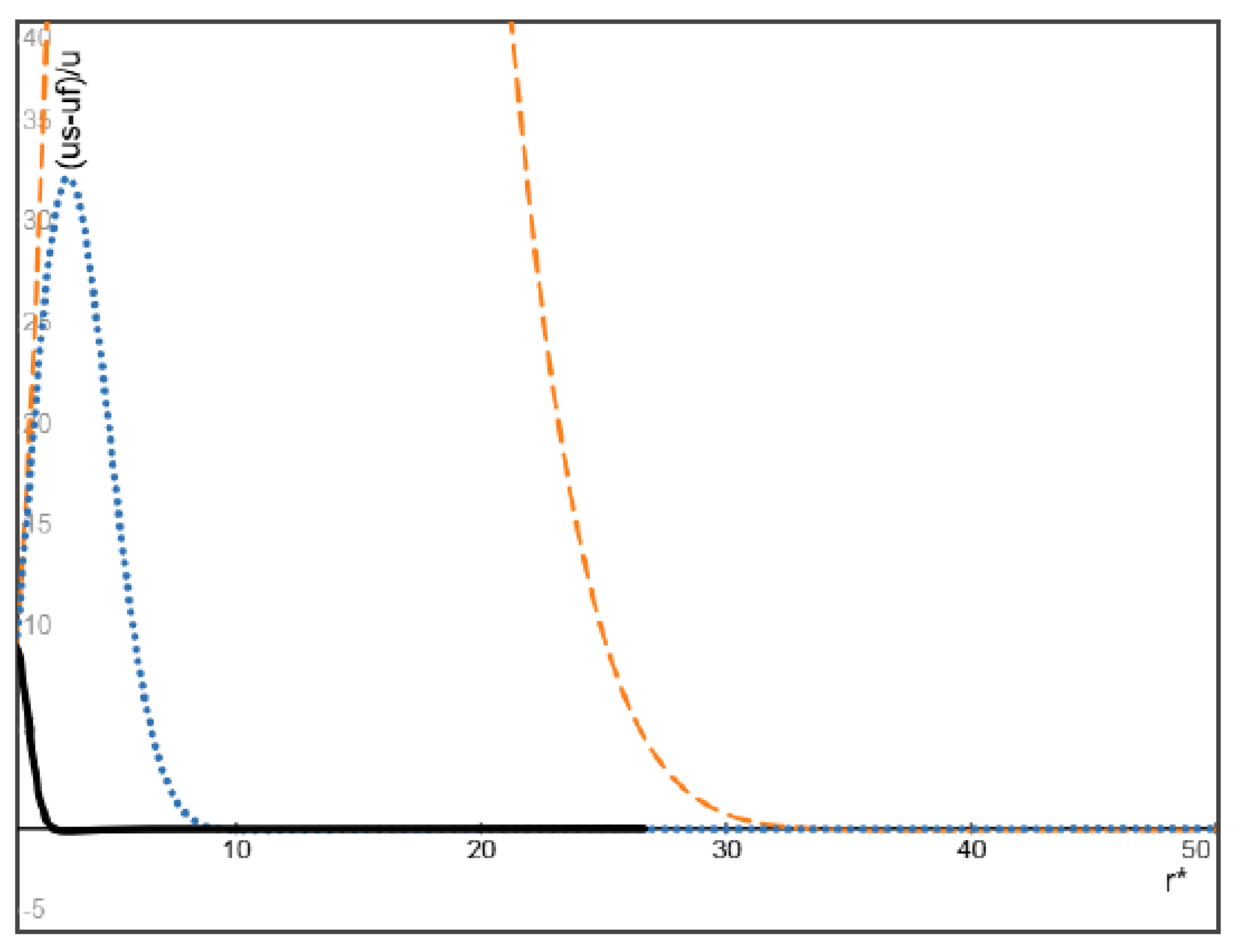

3.2. Particles and Fluid Have the Same Inlet Velocity

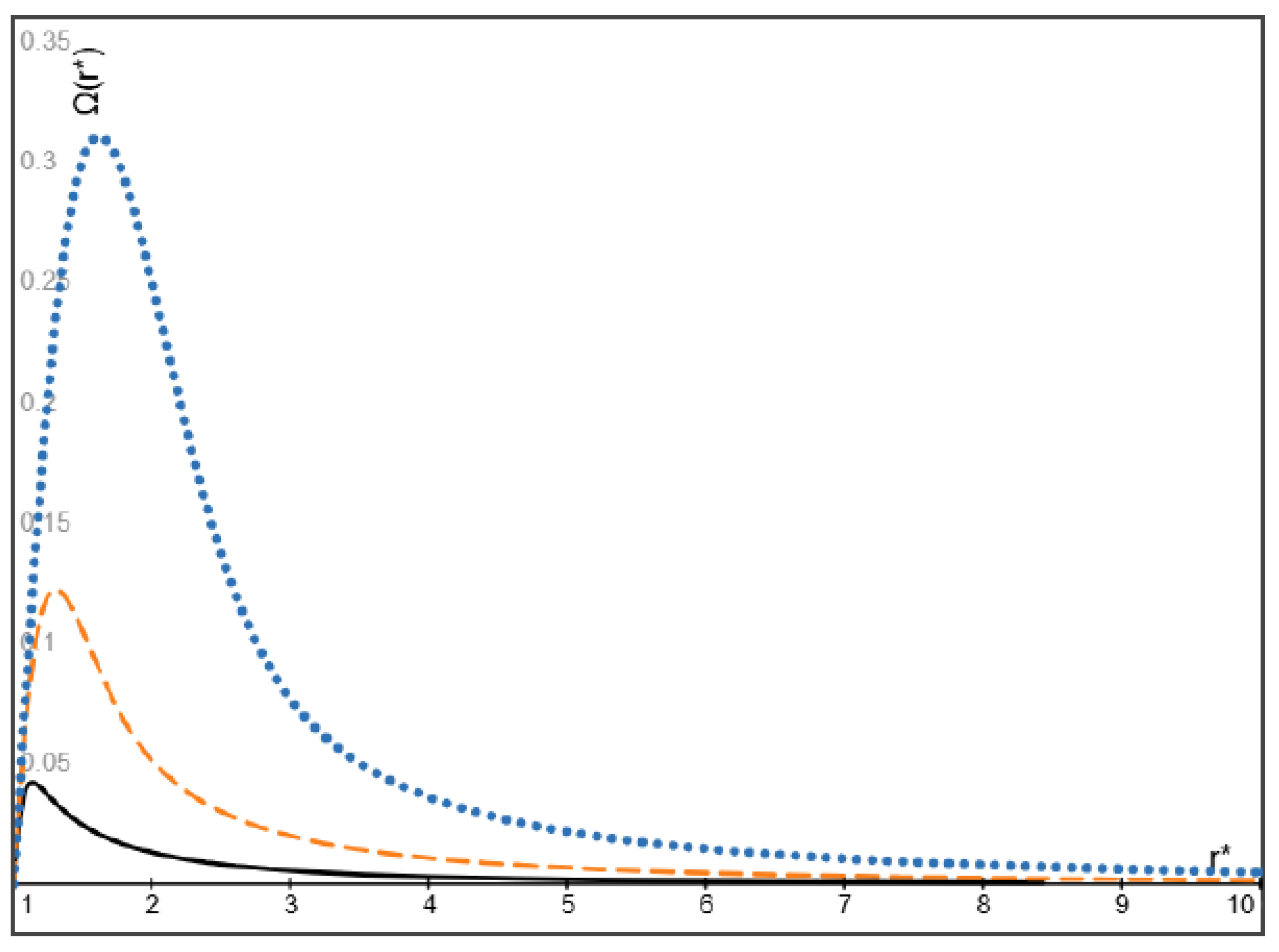

4. Steady Particle Distribution of Plane Radial Diverging Flow

4.1. Light Particles with Higher Inlet Velocity

4.2. Particles and Fluid Have the Same Inlet Velocity

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- In the initial flow field of a particle-fluid suspension with uniformly distributed particles, the relative velocity of particles with respect to the fluid depends on their inlet velocity ratio, the mass density ratio and the Stokes number of particles. For example, when their inlet velocities are equal (then Stokes drag vanishes at the entrance), the particles heavier (or lighter) than the fluid will move faster (or slower) than the fluid. On the other hand, the particles lighter than the fluid can remain faster than the fluid within a sufficiently long distance provided that the inlet velocity of lighter particles is much higher than the inlet velocity of the fluid. This result is qualitatively consistent with some known simulations and experiments on gas-liquid bubbly flow in a diverging channel of finite length driven by high-speed injection of gas bubbles into a nearly stationary liquid.

- (2)

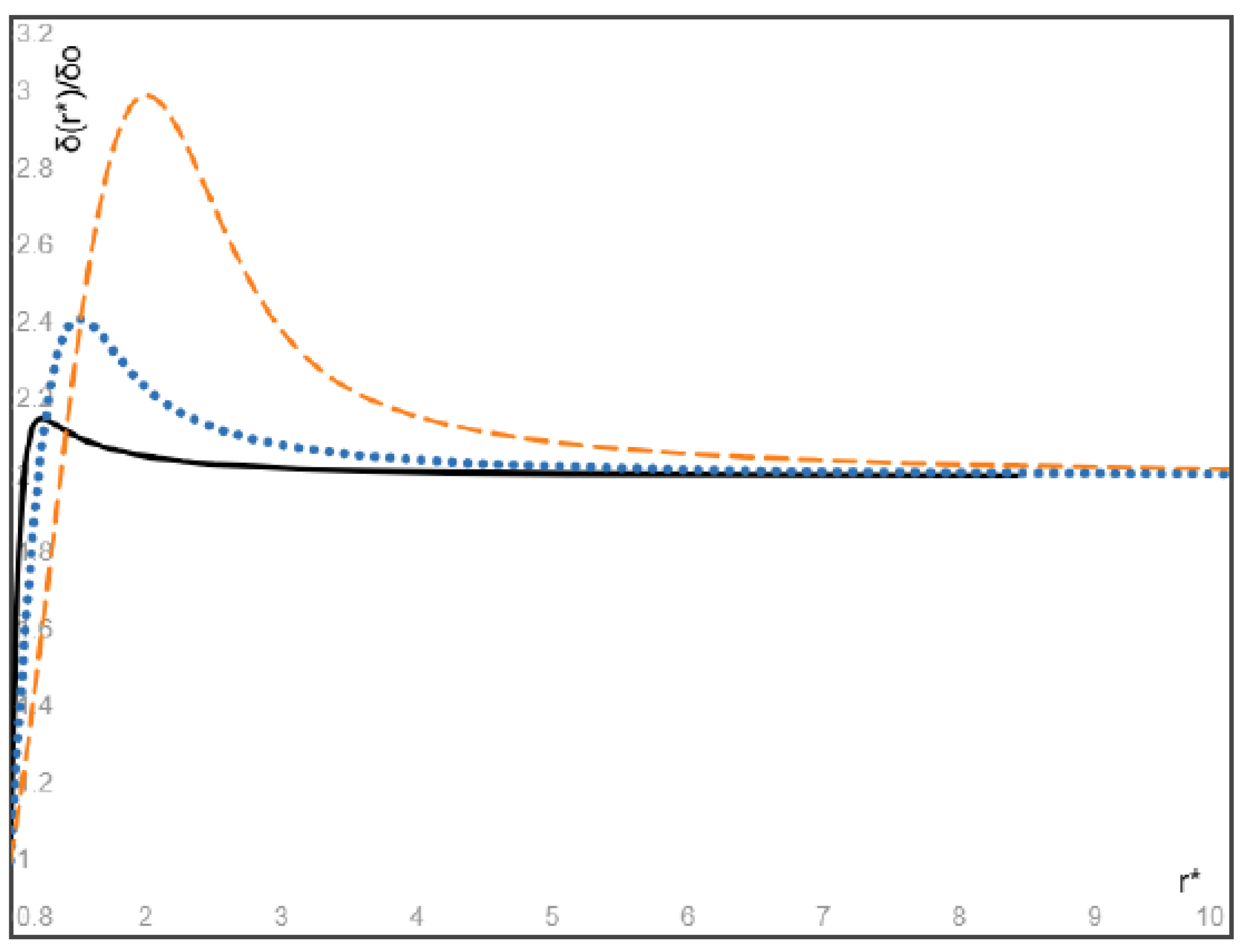

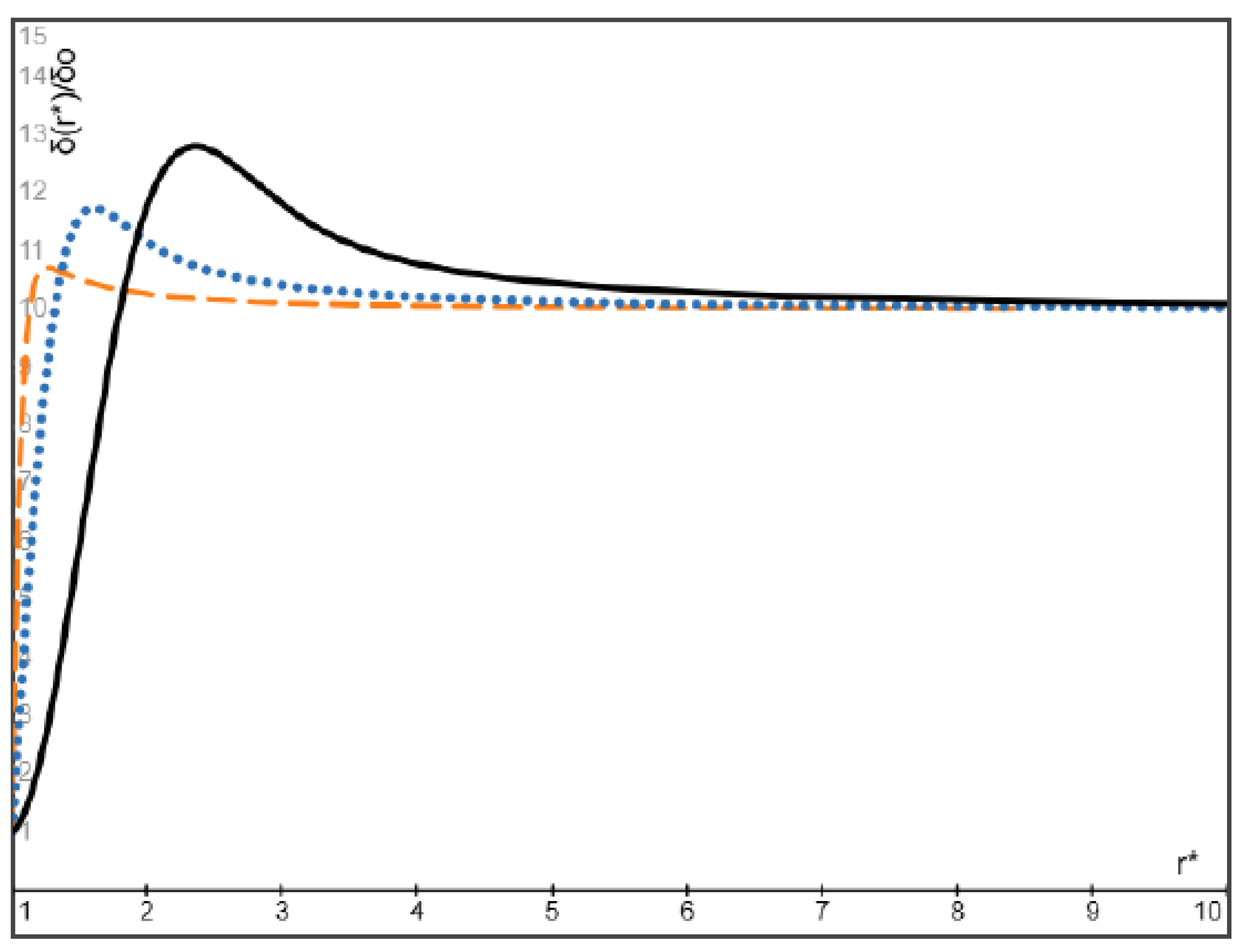

- An explicit expression is obtained for the steady spatial distribution of particles attained eventually as a result of particle migration. In particular, for massless gas bubbles with the inlet velocity higher than the inlet velocity of the fluid, our results show that the volume fraction of bubbles attains its maximum at a location close to the entrance of the flow and after then monotonically decreases with increasing radial coordinate and converges to a finite value determined by the inlet velocity ratio of the bubbles and the fluid. In addition, the maximum volume fraction and its location approach the inlet volume fraction of the bubbles multiplied by the inlet velocity ratio and the entrance location of the flow, respectively, as the Stokes number of bubbles approaches zero.

- (3)

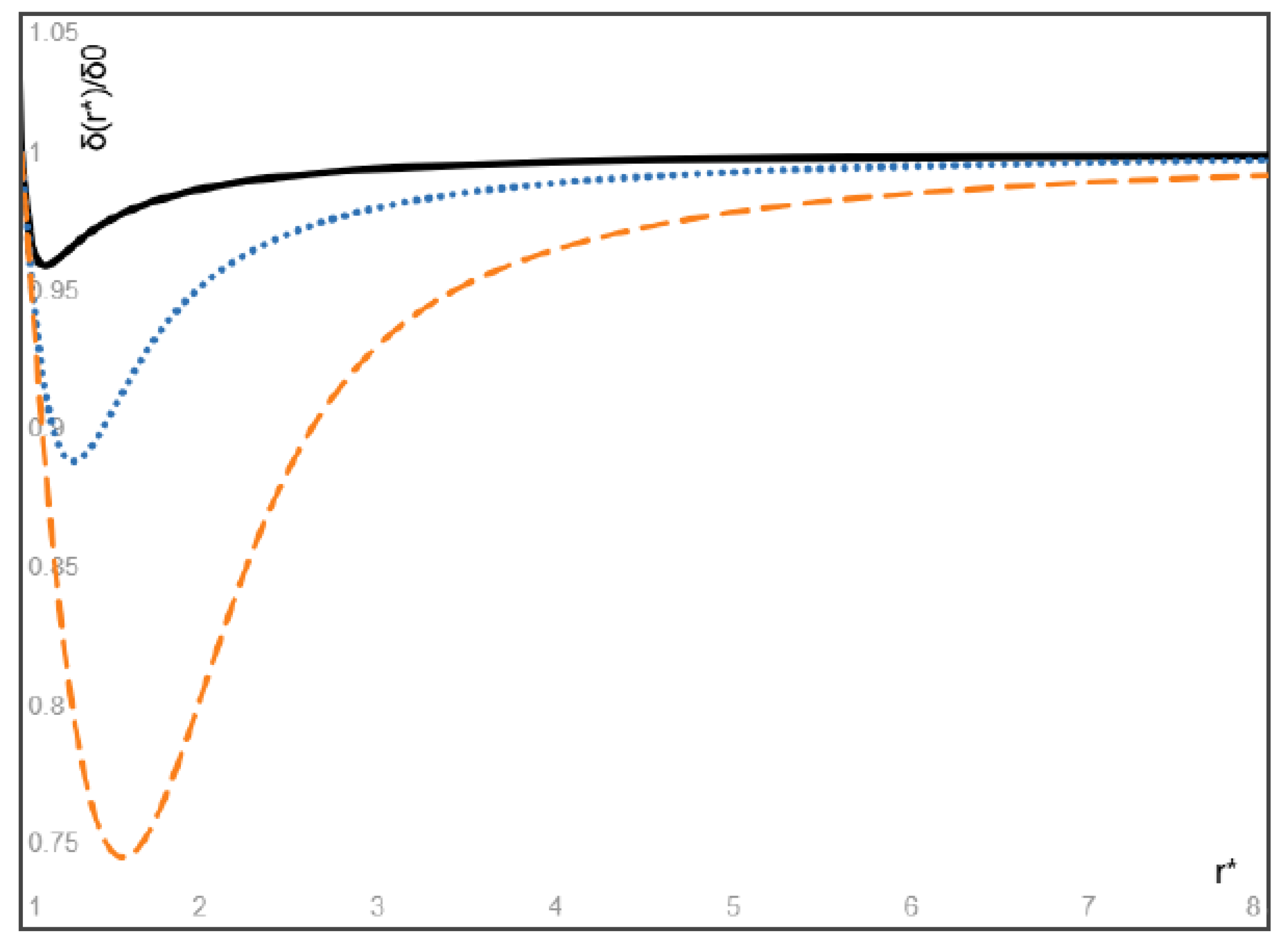

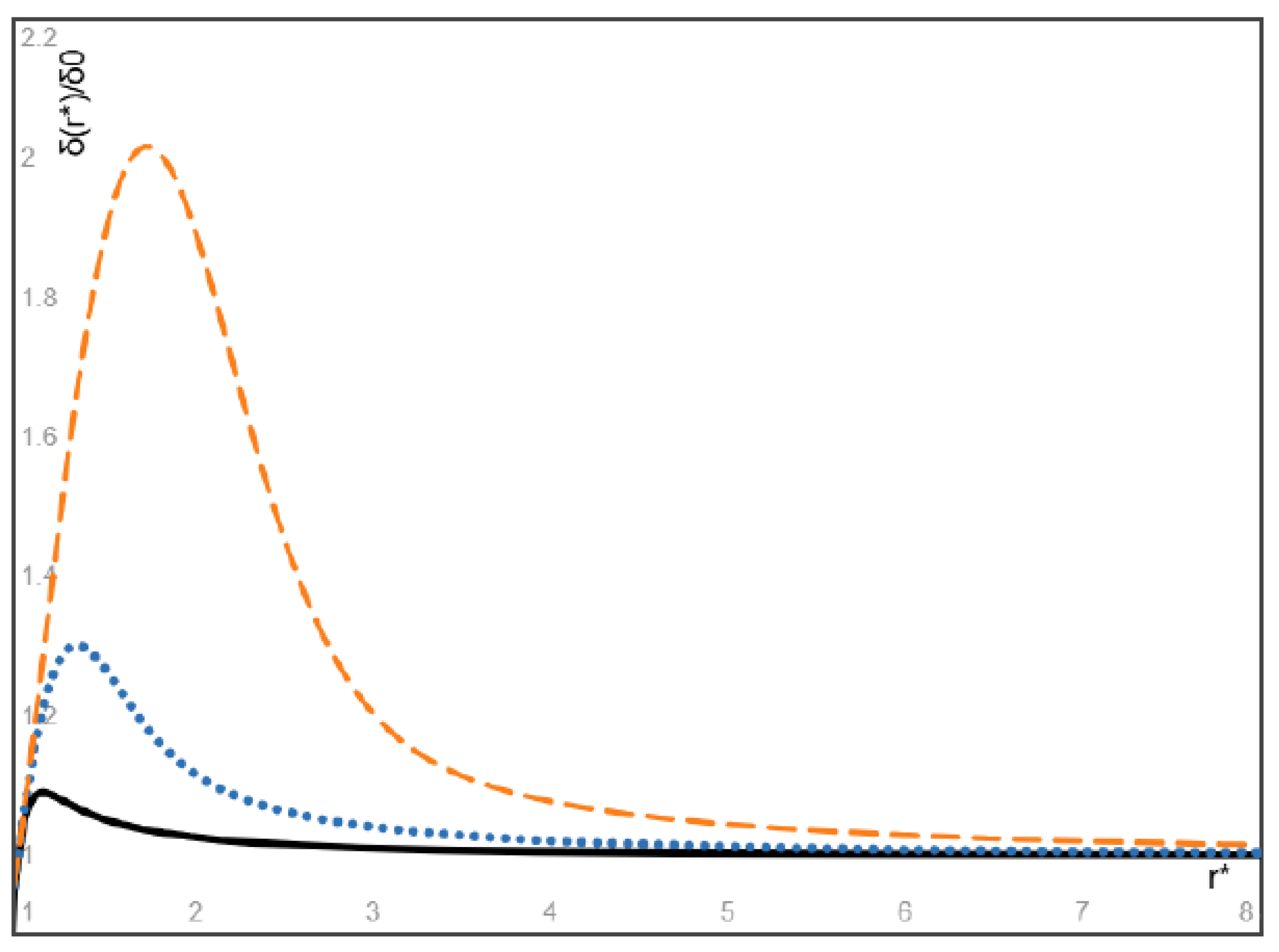

- When the particles and the fluid have the same inlet velocity, our results show that the particles heavier than the fluid attains its minimum at a location close to the entrance of the flow and after then monotonically increases with increasing radial coordinate and converges to a finite value, and the minimum volume fraction and its location approach the inlet particle volume fraction and the entrance location of the flow as the Stokes number of heavy particles approaches zero. On the other hand, the volume fraction of light particles attains its maximum at a location close to the entrance of the flow and after then monotonically decreases with increasing radial coordinate and converges to a finite value, and the maximum volume fraction of light particles and its location approach the inlet particle volume fraction and the entrance location of the flow as the Stokes number of light particles approaches zero

Funding

Contribution

Ethical approval

Declaration of interests

Appendix A. Derivation of Equations (1-5)

References

- Jeffery GB (1915) The two-dimensional steady motion of a viscous fluid. Phil. Mag. (Series 6) 29, pp455-465.

- Fraenkel LE (1962) Laminar flow in symmetrical channel with slightly curved walls. I. On the Jeffery-Hamel solutions for flow between plane walls. Proc. R. Soc. London A267, pp119-138.

- Eagles PM (1966) The stability of a family of Jeffery-Hamel solutions for diverging channel flow. J. Fluid Mech. 24(1), pp191-207.

- Fujimura K. On the linear stability of Jeffery-Hamel flow in a converging channel. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 1982, 51, 2000–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, WHH; et al. (1988) On perturbations to Jeffery-Hamel flow. J. Fluid Mech.186, pp559-581.

- Akulenko, LD; et al. (2004) Solutions of the Jeffery-Hamel problem regularly extendable in the Reynolds number. Fluid. Dyn. 39(1), pp12-28.

- Putkaradze V & Vorobieft P (2006) Instabilities, bifurcations, and multiple solutions in expanding channel flows. Phys. Rev. Let.(7), 144502.

- Haines, PE; et al. (2011) The Jeffery-Hamel similarity solution and its relation to flow in a diverging channel. J. Fluid Mech. 687, pp404-430.

- Jotkar MR & Govindarajan R (2017) Non-modal stability of Jeffery-Hamel flow. Phys. Fluids.29, 064107.

- Noureen & Marwat DNK (2022) Double-diffusive convection in Jeffery-Hamel flow. Sci. Reports 12, 9134.

- Goli, S; et al. (2022) Physics of fluid flow in an hourglass (converging-diverging) microchannel. Phys. Fluids 34 (5), 052006.

- Kumar A; Govindarajan R. On the intense sensitivity to wall convergence of instability in a channel. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee D (2024) Linear temporal stability of Jeffery-Hamel flow of nanofluids. Euro. J. Mech./B Fluids 107, pp1-16.

- Rana, P; et al. Multiple solutions and temporal stability for ternary hybrid nanofluid flow between non-parallel plates. J. Appl. Math. Mech. (ZAMM) 2024, 104, e202400124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AI-Saedi, AA; et al. (2025) Study on Jeffery-Hamel nano-fluid flow with uncertain volume fraction using semi-analytical approach. AIP Advances 15, 045113.

- Park, H.M. (2018) Comparison of the pseudo-single-phase continuum model and the homogeneous single-phase model of nanofluids. Int. J. Heat & Mass Transfer 120, pp106-116.

- Saha, G. & Paul M.C. (2018) Investigation of the characteristics of nanofluids flow and heat transfer in a pipe using a single phase model. Inter. Communications in Heat & Mass Transfer 93, pp48-59.

- Turkyilmazoglu M (2020) Single phase nanofluids in fluid mechanics and their hydrodynamic linear stability analysis. Computer Methods & Programs in Biomedicine 187, 105171.

- AI-Nimr, MA; et al. (2010) Effect of velocity-slip boundary conditions on Jeffery-Hamel flow solutions. J. Appl. Mech.(ASME) 77, 041010.

- Turkyilmazoglu M (2014) Extending the traditional Jeffery-Hamel flow to stretchable convergent/divergent channel. Computer & Fluids 100, pp196-203.

- Soliman HM (2017) Laminar, radial flow of two immiscible fluids in slender wedge-shaped passages. J. Fluids Engng. (ASME) 139, 081201.

- Sahu KC & Govindarajan R (2005) Stability of flow through a slowly diverging pipe. J. Fluid Mech. 531, pp325-334.

- Klinkenberg, J.; et al. (2014) Linear stability of particle laden flows: the influence of added mass, fluid acceleration and Basset history force. Mechanica 49, pp811-827.

- Ru CQ (2024) Rotational flow field of a particle-laden fluid on a co-rotating disk. Phys. Fluids (36) (11), 113356.

- Rubinow SI & Keller JB (1961) The transverse force on a spinning sphere moving in a viscous fluid. J. Fluid Mech.11, pp447-459.

- Saffman PG (1965) The lift on a small sphere in a slow shear flow. J. Fluid Mech.22, pp385-400.

- Boronin SA & Osiptsov AN (2020) Stability of a vertical Couette flow in the presence of settling particles. Phys. Fluids (32), 024104.

- Li, H; et al. (2020) Eulerian-Lagrangian simulation of inertial migration of particles in circular Couette flow. Phys. Fluids ((32), 073308.

- Saffman, P.G. (1962) On the stability of laminar flow of a dusty gas. J. Fluid Mech.13, pp120-128.

- Michael DH (1965) Kelvin-Helmholtz instability of a dusty gas. Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc.61, pp569-571.

- Yang, Y; et al. (1990) The influence of particles on the spatial stability of two-phase mixing layers. Phys. Fluids A2 (10), pp1839-45.

- Dimas AA & Kiger KT (1998) Linear instability of a particle-laden mixing layer with dynamic dispersed phase. Phys. Fluids (10), pp253957.

- Senatore, G; et al. (2015) The effect of non-uniform mass loading on the linear, temporal development of particle-laden shear layers. Phys. Fluids 27, 033302.

- Goldshtik MA & Shtern VN (1989) Loss of symmetry in viscous flow from a linear source. Fluid Dyn. 24, pp151-199.

- Shusser M & Weihs D (1995) Stability analysis of source and sink flows. Phys. Fluids 7(10), pp245-2353.

- Putkaradze V & Dimon P (2000) Non-uniform two-dimensional fluid from a point source. Phys. Fluids 12(1), pp66-70.

- Chemetov NV & Starovoitov VN (2002) On a motion of a perfect fluid in a domain with sources and sinks. J. Math. Fluid Mech.4, pp128-144.

- Taylor GI (1932) The viscosity of a fluid containing small drops of another fluid. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A138, pp41-48.

- Ohie, K; et al. (2024) Rheology of dilute bubble suspension in unsteady shear flow. J. Fluid Mech. (983), A39.

- Auton, TR; et al. (1988) The forces exerted on body in inviscid unsteady non-uniform rotational flow. J. Fluid Mech.197, pp241-257.

- Kuo JT & Wallis GB (1988) Flow of bubbles through nozzles. Int. J. Multiphase Flow (14) (5), pp547-564.

- Chen, J; et al. (2024) Numerical simulation of single bubble motion fragmentation mechanism in Venturi-type bubble generator. Mechanics & Industry (25), 21.

- Zhao, L; et al. (2024) Investigations on the near-wall bubble dynamic behaviors in a diverging channel. AIP Advances 14, 115014.

- Zeng, X; et al. (2025) Simulation of the vane-type bubble separator using a hybrid Euler-Euler/volume-of-fluid approach. Phys. Fluids (37), 043330.

- Tribbiani, G; et al. (2025) An image-based technique for measuring velocity and shape of air bubbles in two-phase vertical bubbly flows. Fluids (10), 69.

- Nedeltchev S (2025) Updated review on the available methods for measurement and prediction of the mass reansfer coefficients in bubble columns. Fluids (10), 29.

- Magnaudet J & Eames I (2000) The motion of high-Reynolds-Number bubbles. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. (32), pp659-708.

- Khan, I; et al. (2020) Two-phase bubbly flow simulation using CFD method: a review of models for interfacial forces. Prog. Nuclear Energy (125), 103360.

- Basagni, G; et al. (2023) Computational fluid dynamics modeling of two-phase bubble column: a comprehensive review. Fluids (8), 91.

- Legendre D & Zenit R (2025) Gas bubble dynamics. Rev. Modern Phys. (97), 025001.

- Ru CQ. Stability of plane parallel flow revisited for particle-fluid suspensions. J. Appl, Mech. (ASME) 2024, ((91)), 111005. [Google Scholar]

- Ru CQ (2025) On Kelvin-Helmholtz instability of particulate two-fluid flow. Acta Mechanica Sinica (41), 324143.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).