1. Introduction

RNA can be categorized into two main types: protein-coding messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), which do not have protein-coding potential [

1]. Among the ncRNAs, long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a vital subclass involved in gene expression regulation. While several early studies detected lncRNAs as transcriptional noise, subsequent functional characterizations have propelled them to the forefront of regulatory biology research [

2,

3]. LncRNAs are characterized by their extended length (≥ 200 nt) and are classified into four groups: intergenic, antisense, intronic, and potentially novel isoforms, based on their position relative to lncRNA and mRNA in the genome [

4,

5]. A lncRNA in rice, termed

VIVIpary, has the capability to enhance seed dormancy [

6]. In

Arabidopsis thaliana, the

DROUGHT INDUCED lncRNA ((

DRIR) functions as a positive regulatory factor, enhancing the plant’s tolerance to abiotic stresses [

7]; During vernalization,

COOLAIR and

COLDAIR lncRNAs regulate the expression of

FLOWERING LOCUS C ((

FLC), triggering floral timing [

8]. However, the regulatory mechanisms of plant lncRNAs in drought stress responses remain less understood. Our study aims to elucidate how plant lncRNAs respond to drought stress, which is crucial for advancing the understanding of lncRNA functions.

Drought stress is the most prevalent among abiotic stresses, more so than temperature or salinity, among others [

9]. In addition, aridity is a leading cause of yield reduction in some regions, with greater impact on crop production than all biotic stresses together [

10]. To combat drought stress, plants have developed complex molecular regulatory networks that enable timely environmental response and adaptation [

11,

12]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that the drought response mechanisms in plants are linked to the abscisic acid (ABA) signaling pathways and lncRNAs [

13,

14]. High-throughput transcriptomic profiling under drought stress has systematically elucidated drought-responsive regulatory networks across diverse plant species [

15,

16]. LncRNA

MSTRG.6838 in maize shows co-downregulation with its target H+-ATPase subunit gene during drought stress, suggesting functional coregulation in stress response [

17]. Li

et al. [

18] showed that rice develops drought stress memory through synergistic regulation between lncRNAs and abscisic acid (ABA), enhancing drought tolerance. It’s clear that the growing demand for food has led to the search for more scientific ways to increase plant drought tolerance and increase crop yields [

19]. Our study aimed to discover the drought tolerant mechanisms of lncRNAs to improve crop yield and grain quality, which will provide novel strategies for enhancing agricultural productivity.

Tibetan hulless barley (

Hordeum vulgare L. var.

nudum), colloquially termed “Qingke” in China, serves as one nutritious basic food for Tibetan populations and a crucial feed source for herds in the Qinghai-Xizang (Tibet) Plateau (QTP) [

20,

21]. The high-altitude ecosystems of the QTP endows Tibetan hulless barley with remarkable resistance to abiotic stresses, characterized by strong cold resistance, a short growing period, high productivity, early maturation, and remarkable adaptability to diverse environments and makes it an excellent crop model for the analysis of drought tolerance mechanism [

22,

23]. In recent years, RNA-seq was commonly utilized to uncover the molecular mechanisms of drought resistance in hulless barely [

24,

25]. Comparative transcriptomic investigation across a gradient of water stress treatments in hulless barley leaf tissues and uncovered coordinated regulation by numerous transcription factor families (TFs) and plant hormone signaling cascades during drought adaptation [

26]. As a typical model for extreme environment adaptation, hulless barley possesses abundant stress-resistant genetic resources, which establishes its value across multiple research regions [

27]. However, in early explorations of drought resistance, researchers still lacked a profound understanding of how hulless barely lncRNAs regulate gene expression to cope with drought stress during extreme weather. Thus, investigating the abiotic stress adaptation particularly the drought tolerance mechanisms, in hulless barley, is essential for advancing crop resilience research. Here, we conducted the rigorous lncRNA recognition for surveying the expression patterns of lncRNAs between two cultivars of hulless barley under different drought treatments, delineated the basic characteristics of lncRNAs, carried out drought-responsive lncRNAs, functional annotated the

cis- and

trans-regulatory roles of lncRNA target genes and predicted the potential roles of this drought-responsive lncRNAs. All above, our work provides preliminary insights about the response mechanisms of lncRNAs to drought stress and offer novel possibilities to stabilize crop yields during droughts and enhance productivity in drought-prone farm.

2. Result

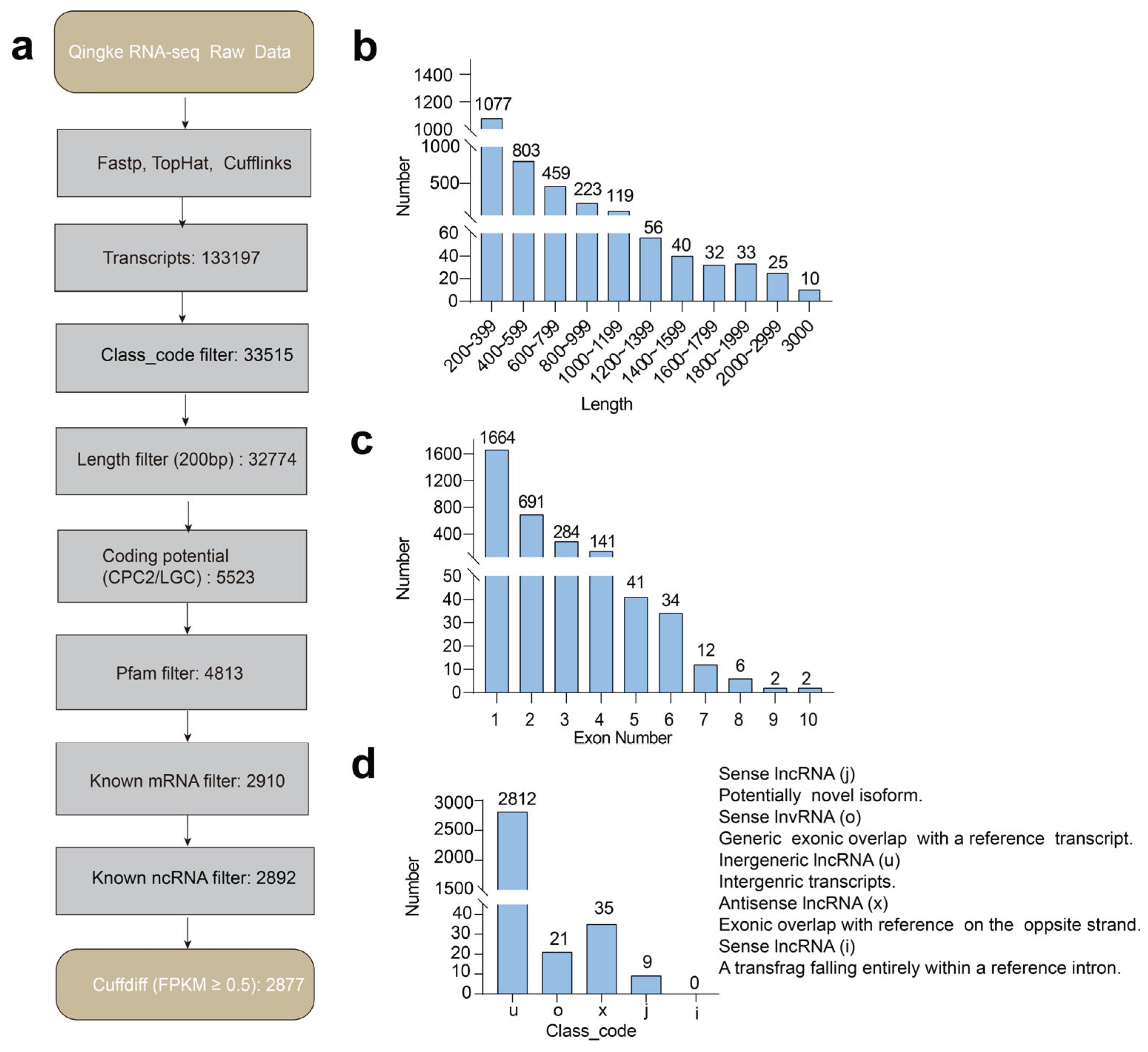

2.1. Genome-Scale Transcriptional Signatures of LncRNAs in Two Hulless Barley Cultivars Under Drought Conditions

A chromosome-scale genome assembly was achieved for hulless barley with assistance [

28], we further explored the published transcriptomic data of the drought-tolerant cultivar Z772 and the drought-sensitive cultivar Z103 of hulless barley under various treatment durations [

29] to reveal drought-induced lncRNA expression profiles, we subjected the data to a rigorous filtering pipeline. This included selecting for length, assessing coding potential, and evaluating expression levels. As a result, we identified 2,877 lncRNAs from a total of 133,197 transcripts in the six hulless barley samples (

Figure 1a and

Supplementary Table S1). The lengths of the lncRNAs ranged from 201 to 5,837 nucleotides (nt), with an average length of 596 nt (

Figure 1b and

Supplementary Table S2). Analysis of exon distribution patterns in hulless barley lncRNAs has revealed a striking predominance of single-exon transcripts. More than half (1,664 out of 2,877, 57.8%) of the identified lncRNAs were single-exonic, in contrast to 24.0% (691) that contained two exons and only 18.1% (522) exhibiting more than three exons (

Figure 1c and

Supplementary Table S3). Additionally, the 2,877 lncRNAs were classified into four groups based on their class_code, which includes 2,812 intergenic lncRNAs (u), 30 antisense lncRNAs (x), and 30 sense lncRNAs, (further divided into 21 overlapping (o) and 9 junctional (j), depending on the relative positions of their transcripts to the genome. Intriguingly, intronic lncRNAs have been detected as a type of lncRNA in other species [

30], but not characterized in the hulless barley (

Figure 1d and

Supplementary Table S4). Clearly, hulless barley contains multiple categories of lncRNAs, with lincRNAs being the most dominant form. Compared to other plants, the fundamental features of hulless barley lncRNAs exhibit greater diversity. These distinct characteristics suggest that the biological functions of lncRNAs in hulless barley may be due to its unique geographical location and extreme environmental adaptation mechanisms, warranting further experimental investigation.

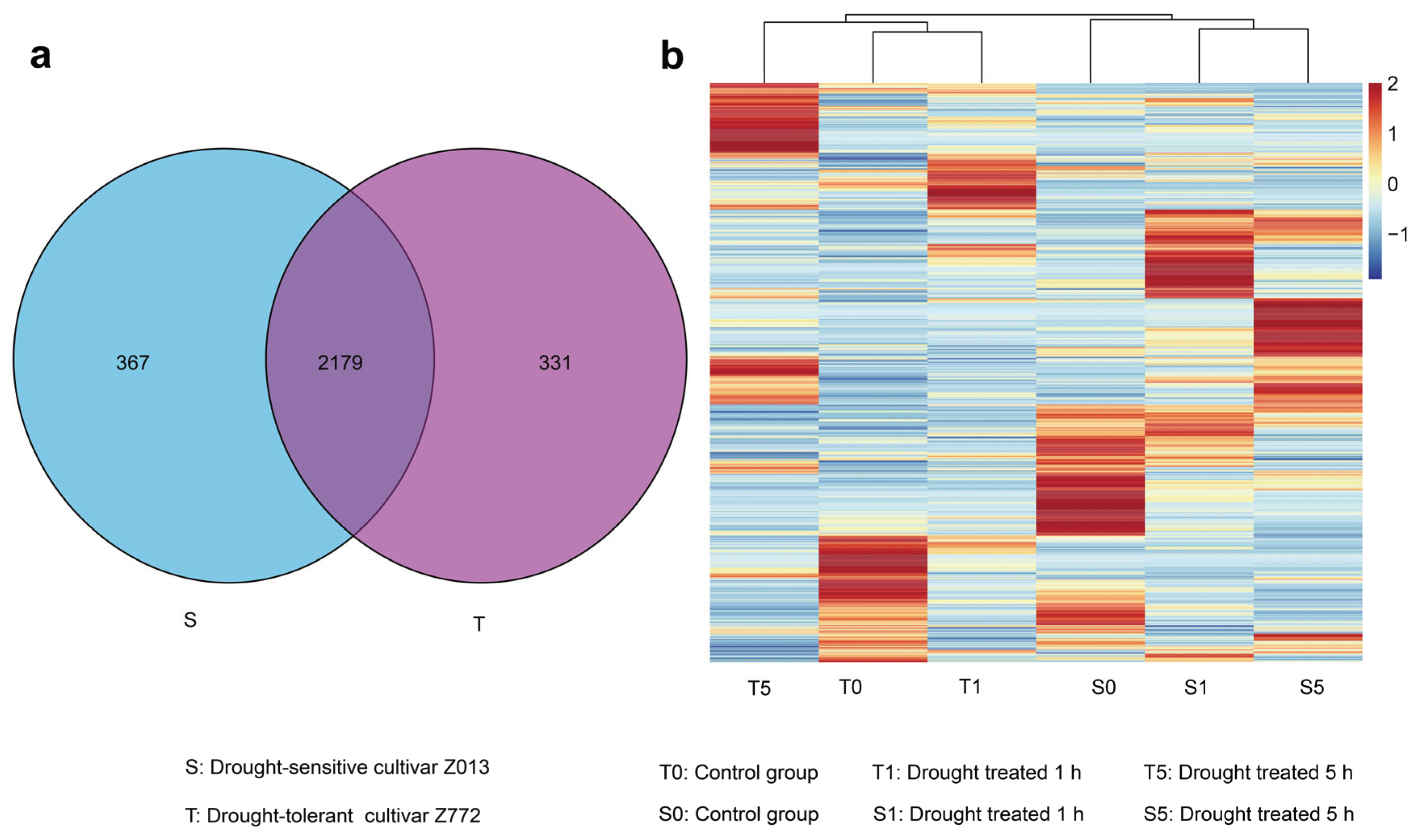

2.2. Characterization of DElncRNAs in Two Hulless Barley Cultivars Under Different Drought Treatment Times

To further delineate the potential functions of lncRNAs in two hulless barley cultivars under drought stress, we utilized FPKM values to investigate their expression patterns. All DElncRNAs were screened, as they may be involved in the drought stress response. In previous research, Liang

et al. [

29] Labeled samples of the drought-tolerant cultivar Z772 after 0, 1, and 5 h of drought treatment are designated as A, B, and C, respectively. Similarly, samples of the drought-sensitive cultivar Z013 subjected to the same treatment durations are labeled D, E, and F. To enhance clarity, this study refers to samples A, B, and C as T0, T1, and T5, and samples D, E, and F as S0, S1, and S5. Upset and Venn diagrams were used to uncover the co-expression patterns of lncRNAs between the two cultivars. Then, we discovered that 2,179 lncRNAs were co-expressed in two hulless barley cultivars, whereas 331 and 367 lncRNAs were specifically expressed in each, respectively (

Figure 2a and

Supplementary Table S5). The specifically expressed lncRNAs appear to be directly related to the drought-tolerance or drought-sensitivity of the cultivar. The co-expressed lncRNAs may play conserved regulatory roles in both cultivars. Based on hierarchical clustering of the lncRNA expression matrix and their expression patterns, T0, T1, and T5 were clustered into one group, whereas S0, S1, and S5 formed another group (

Figure 2b and

Supplementary Table S6). A stringent criterion we established: | log2 (fold change) | values ≥ 1, p value ≤ 0.01 to elucidate DElncRNAs and a total of 1004 DElncRNAs were found in this study (

Supplementary Table S7). A more detailed analysis revealed that the T0/T1 and S1/S5 groups exhibited closer clustering than the T5 and S0 groups, indicating that mild drought and control conditions showed greater expression pattern concordance in drought-tolerant cultivars. Conversely, in drought-sensitive cultivars, lncRNAs demonstrated similar expression patterns under two different levels of drought stress.

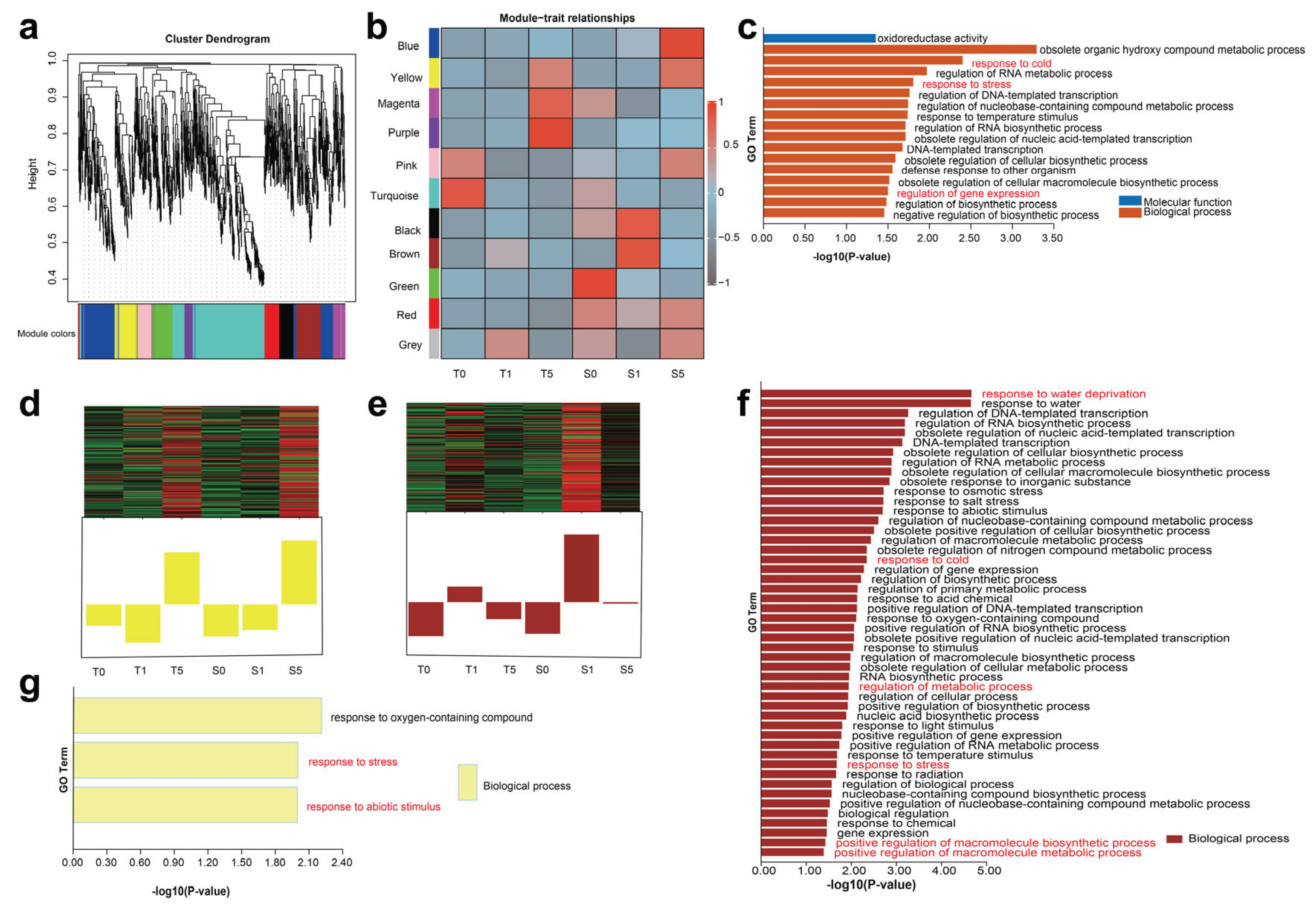

2.3. Exploring the Regulatory Mechanisms (Trans- and Cis-) of LncRNAs Based on the Distances Between Protein-Coding Genes and LncRNAs

Based on plant lncRNAs, regulation of growth and developmental processes can be achieved through both

cis-acting (local) and

trans-acting (distal) mechanisms [

31], we first systematically investigated

the trans-regulatory interactions among all protein-coding genes (PCGs) and the identified long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). We subjected the screened 2,877 lncRNAs and 38,453 PCGs to Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA). After optimizing the parameters, we identified 923 lncRNAs and 684 PCGs associated with drought stress for module identification. Hierarchical clustering revealed 11 modules that were highly correlated (

Figure 3a and

Supplementary Table S8). Notably, the turquoise, blue, brown, purple, and green modules exhibited significantly higher numbers of co-clustered lncRNAs and PCGs than other modules. Although the number of co-expressed protein-coding genes (PCGs) was substantial, lncRNAs were relatively scarce in each module. This method allowed us to infer the

trans-regulatory roles of lncRNAs by utilizing the biological functions of their co-expressed PCGs. Module-trait relationships were also identified in our study (

Figure 3b). Subsequently, we selected two high-interest modules, “Brown” and “Yellow” for further investigation.

The “Yellow” module, which we refer to as the drought stress time-response module. In the “Yellow” module, following 5 h of drought treatment, the gene exhibited upregulated expression in both hulless barley cultivars, indicating that prolonged drought stress initiates its responsive regulation (

Figure 3d). The Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of protein-coding genes (PCGs) in this module was enriched for biological processes such as “response to oxygen-containing compounds”, “response to stress”, and “response to abiotic stimulus”. These findings substantiate the observations, indicating that the genes mounted an emergency response to prolonged drought stress (

Figure 3g).

The “Brown” module called the drought stress cultivars-response module. In the “Brown” module, we observed a significant upregulation in the expression of both lncRNAs and PCGs at 1 h of drought treatment in the drought-sensitive cultivar, with expression levels higher than those in all other treatment groups and time points (

Figure 3e). GO enrichment analysis of the module’s PCGs revealed their primary functional associations with “water deprivation response” “abiotic stress response”, “regulation of metabolic processes”, and “positive regulation of macromolecule biosynthetic and metabolic processes”. (

Figure 3f). This indicates that drought-sensitive cultivars exhibit earlier activation of stress-responsive mechanisms compared to drought-tolerant cultivars under water deficit conditions. The co-expression network identified the lncRNAs and PCGs involved in hulless barley’s response to drought stress and revealed their potential functions.

In addition to their

trans-regulatory function, lncRNAs also contribute to changes in the transcriptome through a

cis-regulatory role in response to drought stress. To test this hypothesis, from 1,004 DElncRNAs, we used Bedtools to screen for 91 neighboring genes within approximately 100 kb upstream and downstream. Subsequently, GO enrichment analysis was performed on these 91 neighboring genes. The results revealed a notable enrichment in the biological process terms “organic hydroxy compound metabolic process”, “regulation of RNA biosynthesis”, “response to stress”, and “gene expression”. (

Figure 3c). Combining the GO analyses of

cis- and

trans-acting elements revealed shared enrichment in pathways related to biotic and abiotic stress responses. These results demonstrate that lncRNAs in hulless barley may regulate drought stress responses through both

cis-acting and

trans-acting mechanisms.

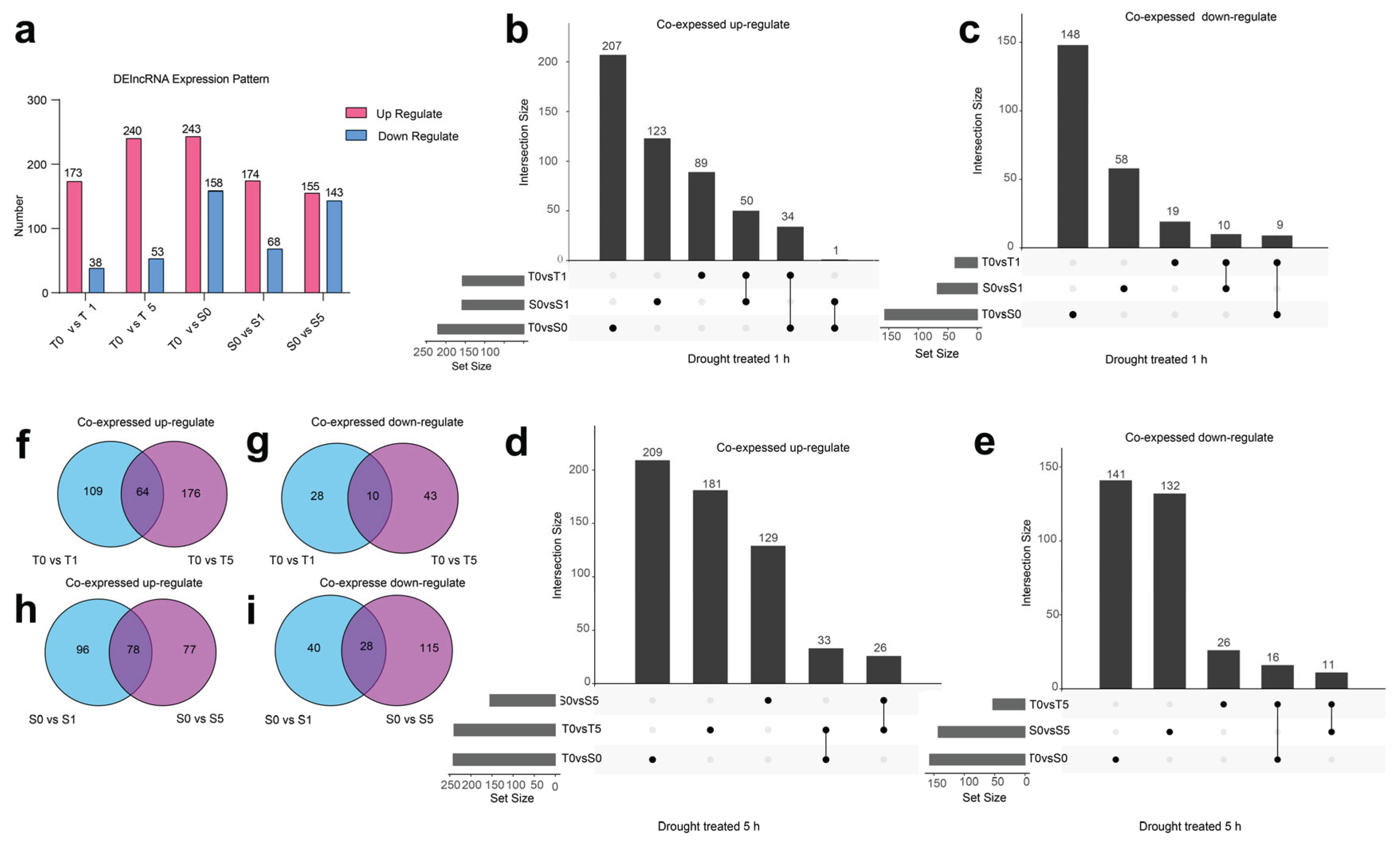

2.4. Dynamics of DElncRNAs in Two Cultivars Across Drought Stress Treatments

To discern the expression patterns of lncRNAs in response to drought stress in two cultivars, we initially identified 1004 DElncRNAs across three distinct treatments. In all treated conditions, the quantity of upregulated DElncRNAs significantly exceeds that of downregulated DElncRNAs (

Figure 4a and

Supplementary Table S9). When compared across two cultivars, the drought-tolerant cultivar Z772 shows 50 co-upregulated DElncRNAs (

Figure 4b), After a 1 h drought treatment, 10 co-downregulated DElncRNAs were identified when compared with the drought-sensitive cultivar Z103 (

Figure 4c). Furthermore, following a 5 h drought treatment, 26 co-upregulated (

Figure 4d) and 11 co-downregulated DElncRNAs were observed (

Figure 4e). All the upregulated and downregulated lncRNAs mentioned have been listed in

Supplementary Table S10. Subsequently, we focused on analyzing the dynamics of DElncRNAs in the two cultivars separately. In the drought-tolerant cultivar, 64 DElncRNAs were co-upregulated (

Figure 4f), and 10 were co-downregulated after 1 and 5 h of drought treatments (

Figure 4g). In contrast, the drought-sensitive cultivar exhibited 78 co-upregulated DElncRNAs (

Figure 4h), and 10 were co-downregulated (

Figure 4i; The data is listed in

Supplementary Table S11). The findings revealed that a significant number of genes exhibited stage-specific responses to drought stress, with markedly distinct expression patterns observed between mild and severe dehydration conditions.

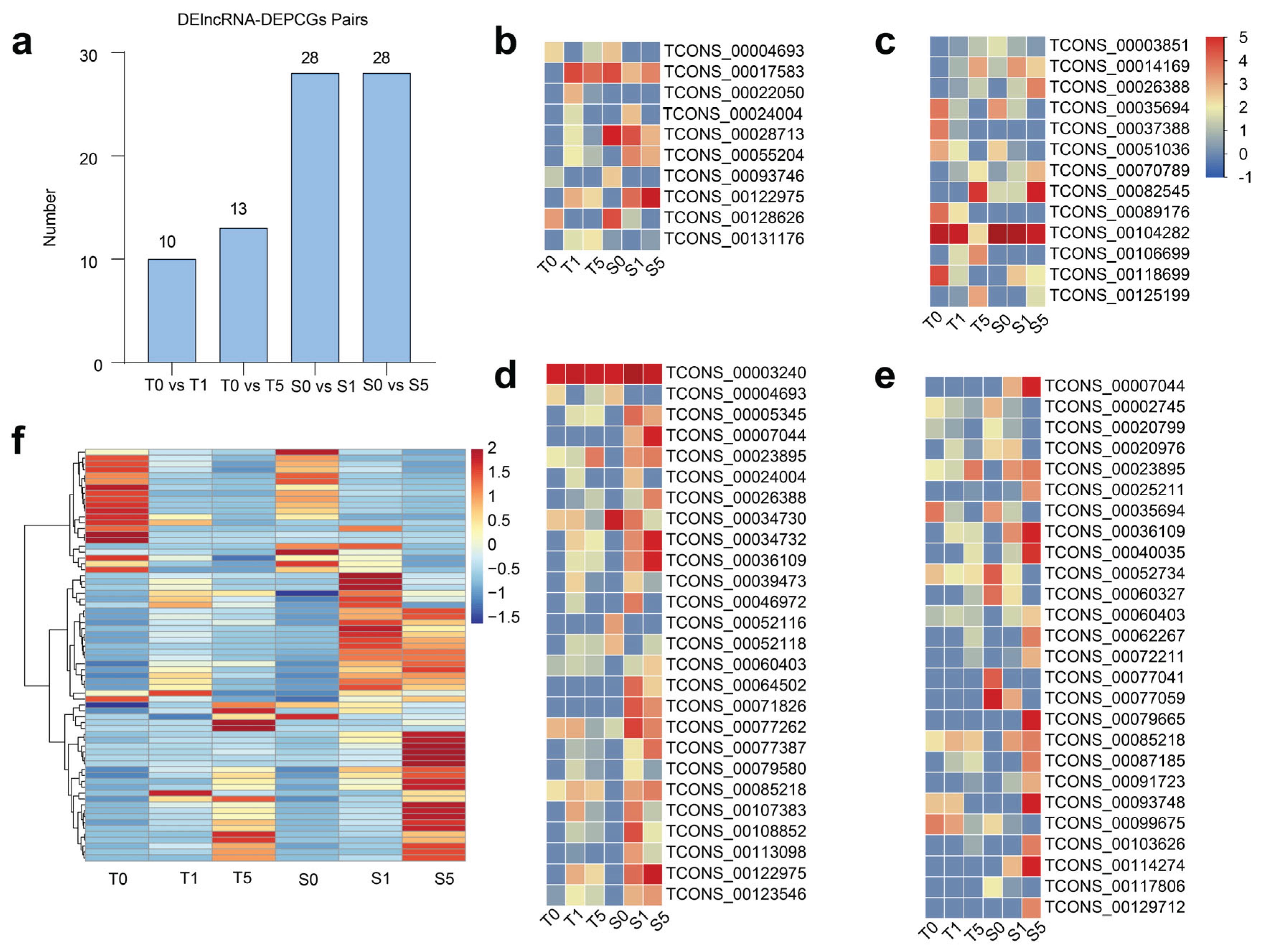

2.5. The Regulatory Diversity of DElncRNAs and Potential Target DEPCGs in Two Cultivars Across Drought Stress Treatments

We identified 85 DElncRNAs with potential target DEPCGs from a total of pairs in two cultivars under different drought treatments (

Figure 5a and

Supplementary Table S12-13), and discovered several DElncRNAs exhibiting significant similarities in expression patterns between two cultivars of hulless barley. For instance, TCONS_00004693, TCONS_00093746, TCONS_00128626 (

Figure 5b), TCONS_00035694, and TCONS_00051036 (

Figure 5c) demonstrated downregulated expression under drought stress in both drought-tolerant and drought-sensitive cultivars. Meanwhile, TCONS_00070789, TCONS_00082545 (

Figure 5c), and TCONS_00023895 (

Figure 5d) showed no significant response to mild drought stress but were markedly upregulated under severe drought stress in both cultivar types. Additionally, TCONS_00024004 (

Figure 5b), TCONS_00039473, TCONS_00079580, TCONS_000107383 (

Figure 5d), and TCONS_00020976 (

Figure 5e) were upregulated under mild drought stress but downregulated under severe drought stress in both cultivars. We also examined the expression patterns of DEPCGs and observed that the majority of DEPCGs in the drought-tolerant cultivar exhibited no significant changes in expression levels after 5 h of drought treatment, whereas the expression levels were significantly altered in the drought-sensitive cultivar. (

Figure 5f and

Supplementary Table S14). This pattern is similar to that observed for DElncRNAs. The results indicate that the expression of these lncRNAs and their target DEPCGs is specific across the six samples, suggesting the functional diversity of these DElncRNAs and DEPCGs in regulation.

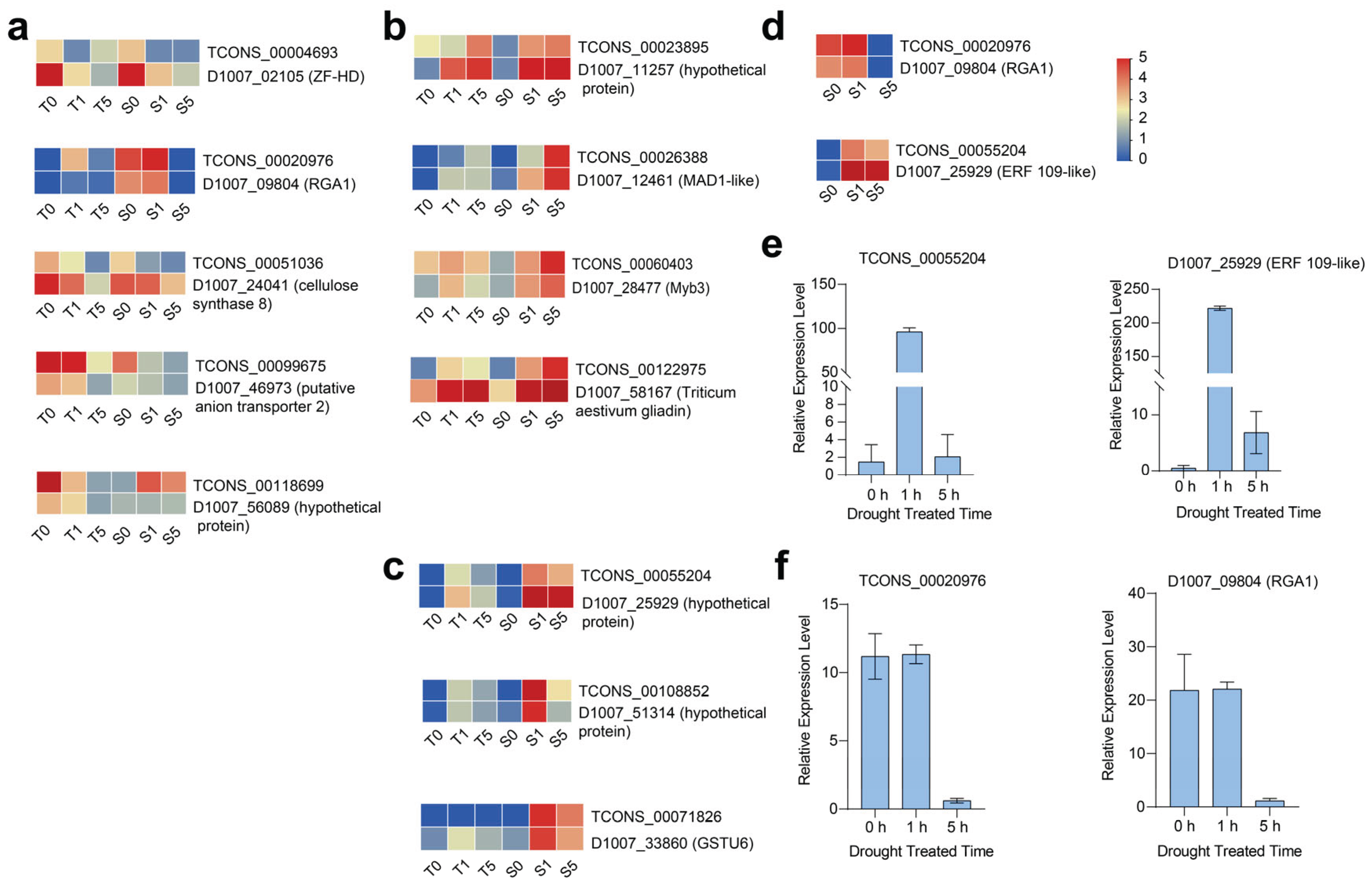

2.6. In-Depth Functional Profiling of Putative lncRNA Target Genes

We further analyzed the expression patterns of DElncRNA-PCG pairs and identified 12 pairs with similar expression profiles, including 5 pairs of drought stress down-regulated DElncRNA-PCGs, respectively: the TCONS_00118699-D1007_56089 pair (with no annotations provided).The TCONS_00099675-D1007_46973 pair functions as an anion transporter 2; the TCONS_00051036-D1007_24041 encodes cellulose synthase 8 (CesA8).TCONS_00004693-D1007_02105 encoding a ZF-HD transcription factor; and the TCONS_00020976-D1007_09804 pair, functioning as putative disease resistance protein Resistance Gene Analog 1 (

Figure 6a). Four pairs of DElncRNA-PCG pairs were highly up-regulated following 5 h of drought treatment: TCONS_00023895-D1007_11257 (with no annotation provided); TCONS_00060403-D1007_28477, encoding a stress-responsive MYB3 protein; TCONS_00122975-D1007_58167, encoding a gliadin protein; and TCONS_00026388-D1007_12461, encoding a protein known as MAD1-like. Additionally, three pairs of DElncRNA-PCG pairs were upregulated after 1 hour of drought treatment but downregulated after 5 hours, respectively: TCONS_00071826-D1007_33860 encoding Glutathione S-Transferase Tau 6; TCONS_00108852-D1007_51314 (none annotated); TCONS_00055204-D1007_25929 (Ethylene response factor 109, ERF 109-like) (

Figure 6c; Details of the 12 selected pairs are presented in

Table S15). In summary, our findings suggest that specific lncRNAs modulate drought stress responses by regulating transcription factors in hulless barley.

Moreover, we utilized the drought-sensitive cultivar (Kunlun 14 as plant materials to verify the reliability of the RNA-Seq data. Two pairs of DElncRNA-PCG pairs (TCON_00020976-D1007_09804 and TCON_00055204-D1007_25929) were selected for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis (

Figure 6d). TCONS_00055204 and D1007_25929 were dramatically upregulated following 1 h of drought treatment (

Figure 6e). Conversely, TCONS_0020976 and D1007_09804 were significantly upregulated after 1 h but downregulated after 5 h of drought treatment (

Figure 6f). The expression patterns of these two pairs of DElncRNA-PCGs were highly consistent with the trends observed in the transcriptomic data. The qRT-PCR results validated the expression patterns of these genes, showing strong concordance with the RNA-Seq data, thereby demonstrating the reliability of the data. Ensure the authenticity of the differentially expressed genes.

3. Discussion

As a critical abiotic stressor, drought severely impairs agricultural productivity by disrupting key physiological and biochemical pathways in plants [

32]. Among staple grains, species such as hulless barley are highly affected by drought [

33]. However, previous studies have revealed that due to its simple genome and strong stress resilience, the genetic and molecular mechanisms of hulless barley are more reliable than those of other cereal crops, thus making it a significant model system for dissecting drought tolerance in cereal crops [

34]. Several studies have shown that lncRNAs play significant roles in various plant species’ biological processes under drought stress conditions [

7,

35]. For example, the

DANA1 enhanced drought tolerance by interacting with DIP1 and PWWP3 in

Arabidopsis [

36]. However, the functions of most lncRNAs in drought stress remain incompletely resolved in hulless barley, particularly due to the lack of functional verification. Our study aims to understand this underexplored area by exploring the molecular mechanisms through which lncRNAs mediate drought stress tolerance in hulless barley.

The widespread application of high-throughput and sensitive technologies has further accelerated the vast field of plant lncRNA research [

34,

35,

36] Numerous lncRNAs have been discovered within plant genomes, including 2,937 in rice [

37] and 1,624 in O

rinus [

38], among others. In this study, we employed a stringent lncRNA screening pipeline to identify 2,877 lncRNAs from the hulless barley genome (Assembly: GCA_004114815.1) [

39]. During the comprehensive analysis of the structural features of these lncRNAs, we observed that most were predominantly characterized by short length, single-exon structures, and were of the intergenic type. Compared with other Poaceae, hulless barley exhibits a reduced number of exons [

40,

41]. We hypothesize that this divergence likely reflects the evolutionary acceleration due to high-altitude environmental pressures, leading to structural simplification in lncRNAs.

As established in previous research, lncRNAs play crucial roles in modulating transcriptional activation and repression in both plant and animal systems [

42,

43]. We therefore concentrated on the expression patterns of DElncRNAs in hulless barley. Remarkably, under moderate drought stress, two varieties of hulless barley exhibited similar quantities of upregulated genes. However, significant disparities in DElncRNAs expression became apparent under extreme drought conditions, with the drought-resistant variety displaying a greater number of upregulated DElncRNAs compared to the drought-sensitive one. This finding presents a stark contrast to previous studies, which demonstrated that the drought-sensitive cultivar exhibits an increasing upregulation of PCGs as drought stress intensifies [

26]. We deduced that lncRNAs in the drought-sensitive cultivar employ distinct regulatory mechanisms compared to those of protein-coding genes during drought stress adaptation.

Moreover, certain functions of the lncRNA targeting PCGs have garnered our attention, particularly their regulatory roles involving transcription factors such as ERF, MYB, and ZF-HD, which are crucial in mediating epigenetic modulation [

44,

45,

46,

47]. In transgenic tomatoes and apples, a factor associated with the AP2/ERF family, named

MhERF113-like, could act as a positive factor in drought tolerance [

48]. Also,

MYB41-BRAHMA (a classic member of the MYB family) [

49] and

PtrVCS2 (a member of ZF-HD family) [

50] modulated drought tolerance in

Arabidopsis and

Populus trichocarpa by regulating stomatal movement and changing vessel morphology. Therefore, we conducted research indicating that investigating key transcription factors in hulless barley serves as a pivotal starting point for elucidating its drought tolerance mechanisms. It was intriguing that the MYB (D1007_28477) and ERF (D1007_25929) we found in hulless barley display markedly divergent expression patterns between the two cultivars: their transcript levels show a time-dependent upregulation in the drought-sensitive cultivar under drought treatment, whereas no significant changes are observed in the drought-tolerant counterpart. This finding suggests that the two transcription factors may play a role in drought stress-inducible responses in the sensitive cultivar. In contrast, the drought-tolerant cultivar likely has a pre-adapted genetic background that allows its osmotic adjustment and reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging system to maintain cellular equilibrium under normal or mild drought conditions, without the need for stress-induced activation of related genes [

51,

52].

Our study provided the first comprehensive investigation of lncRNAs in Tibetan hulless barley’s response to drought stress. We identified a series of drought-responsive lncRNAs and predicted their potential target genes, which are involved in various biological processes. We uncovered that the extreme drought tolerance of hulless barley may stem from the synergistic co-evolution of MYB and ERF with other native transcription factors. We intend to explore the drought tolerance mechanisms of hulless barley in future research.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. The Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

In this study, Tibetan hulless barley accession Kunlun 14 was used as the plant material. To enhance the seed germination rate and growth speed, the seeds were planted in pots filled with a 5:1 mixture of nutrient soil and vermiculite. To ensure optimal growing conditions, we maintained controlled environmental parameters in the growth chamber, with temperatures kept between 23 °C to 25 °C, humidity maintained at 50% to 70% and a photoperiod of 16 h/8 h light/dark.

4.2. Comprehensive Transcriptome Alignment and Assembly

The paired-end RNA-seq data from the Tibetan hulless barley drought response experiment was downloaded from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession number PRJNA391461 [

53]. Fastp (version 0.23.4; accessed on September 19, 2023; parameters: -l 20, -q 5, -u 50) was used to perform quality control (QC) on the initial reads and to clean up the raw data [

54]. Here, we selected the hulless barley genome (assembly version: GCA_004114815.1), which was carried out in 2020, as a reference and utilized the tool (version 2.5.1, available at

https://sourceforge.net/projects/bowtiebio/files/bowtie2/, accessed on May 28, 2024) for subsequent analysis [

39,

55]. This genomic dataset provided us with an invaluable reference foundation, enabling more precise investigations in our follow-up studies. Additionally, TopHat2 (version 2.0.14; available at

https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml, accessed on May 28, 2024; -I 5000) is used for genome index building, a critical step that facilitates rapid and efficient searching of large genomic databases, and for read alignment, a process essential for comparing and analyzing genomic sequences [

56]. To achieve transcript assembly and combination, we utilized Cufflinks (version 2.2.1; available at

https://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/install/, accessed May 28, 2024) [

57]. Subsequently, the expression levels of the isoforms were quantified using FPKM to ensure a standardized basis for comparison.

4.3. Workflow for Systematic lncRNA Annotation

To determine the molecular characteristics of lncRNAs, we developed a rigorous filtering pipeline (

Figure 1a). The transcripts classified as “i” (fully enclosed within a reference intron), “o” (exonic overlaps with a reference transcript), “u” (intergenic transcripts), “j” (potentially novel isoforms), and “x” (exonic overlaps on the opposite strand relative to the reference) were segregated and advanced to the subsequent filtering pipeline. After filtering for transcripts greater than 200 nt, we utilized the BLAST program to identify potential mRNAs, tRNAs, and snoRNAs, applying a stringent e-value threshold of less than 10

-10. With the aid of HMMER (

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/hmmer)[

58], the remaining transcripts were used to eliminate those that contained known protein domains outlined in the Pfam database (e-value < 10

-10) [

59]. Moreover, the Coding Potential Calculator (CPC2 version 2.0) and LGC (version 1.0) were combined to assess the noncoding capacity of the transcripts [

4,

60]. To ascertain whether any of the identified long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) could potentially produce microRNAs (miRNAs), we performed a BLAST search using the candidate lncRNA transcripts against both the miRNA sequences in the hulless barley genome and the mature miRNA sequences listed in the miRbase database. Following this analysis, we further filtered the results, retaining only those isoforms with a FPKM value of 0.5 or higher (FPKM status = OK), thereby ensuring that the final set of lncRNAs were reliably expressed.

4.4. Prediction of Cis-Regulatory Target Genes of lncRNAs in Hulless Barley

Genes transcribed within a 100 kb window upstream or downstream of lncRNAs were identified as potential

cis-acting target genes using Bedtools v2.0 software. The study extracted all differentially expressed protein-coding genes (DEPCGs) around lncRNAs in hulless barley using TBtools (version 2.0) [

61,

62]. To compare the expression patterns of cis-acting target genes with their corresponding DElncRNAs. In this study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of all up-regulated DEPCGs and all down-regulated DEPCGs. Additionally, we identified all cis-regulated target genes of up-regulated DElncRNAs, as well as those of down-regulated DElncRNAs. The PCGs and lncRNAs were merged based on plant samples, and the expression level matrix was inputted into the WGCNA package in TBtools [

63]. A non-directional co-expression network was constructed within each module, and PCGs that exhibited co-expression relationships with lncRNAs were considered to be

trans-regulated target genes. The protein sequence of hull-less barley was annotated using eggNOG-Mapper (

http://eggnog-mapper.embl.de/, accessed on April 8, 2024) as a reference to understand the functions of the

cis/

trans-regulated target genes [

64]. TBtools was used to conduct GO enrichment analyses on the

cis- and

trans-regulated target genes, employing a significance threshold of FDR < 0.05.

4.5. Differential Expression Analysis

Cuffdiff was utilized to calculate the FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) values for lncRNAs. Subsequently, the FPKM method was applied to determine the expression levels of each transcript. DElncRNAs and DEPCGs was conducted in the drought-tolerant cultivar Z772 and the drought-sensitive cultivar Z013 throughout their developmental timeline, using FPKM values. In this study, a log2 fold change value of 1 or greater, combined with a p-value of 0.05 or less, was used to identify differentially expressed genes.

4.6. Drought Stress Treatments

For the drought stress treatment, after 25 days of well-watered growth, the fifth leaves at the fully expanded stage were cut and transferred onto absorbent filter paper in dry dishes within a growth chamber maintained at 23 °C to 25 °C, with humidity kept between 50% and 70%. Equal amounts of leaves from three individuals of Kunlun 14 were collected and pooled, after being placed on filter papers for 0 hours, 1 hour, and 5 hours, respectively. These six samples were quickly ground using a mortar and pestle with liquid nitrogen and then stored in a −80 °C freezer.

4.7. qRT-PCR Validation

To validate the results of RNA-Seq, two pairs of DElncRNA-PCG were chosen as targets for quantitative real-time PCR analysis. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized using 1000 ng of RNA samples and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Takara, Japan). The cDNA product was diluted tenfold, and 1 μL was used in a 20 μL PCR reaction.

The PCR amplification consisted of a preincubation at 95 °C for 5 minutes and 40 cycles, each comprising 15 seconds at 95 °C, 15 seconds at 60 °C, and 15 seconds at 72 °C. The reactions utilized the QuantStudio real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad, USA) and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.). To standardize the cDNA templates, the housekeeping gene EF1α was co-amplified. All primers were synthesized by RuiBiotech. (Table S16).

5. Conclusion

This study underscores the crucial role of lncRNAs in the drought-tolerance mechanisms of hulless barley. We identified 2,877 lncRNAs through RNA-seq analysis of two cultivars: (the drought-tolerant Z772 and the drought-sensitive Z013. Of these, 57.8% of the lncRNAs were found to have a single exon, and no lncRNAs with intronic sequences were detected. Differential expression analysis revealed that 2,179 lncRNAs were co-expressed in both cultivars, while 331 lncRNAs were uniquely expressed in the drought-tolerant cultivar and 367 lncRNAs were uniquely expressed in the drought-sensitive cultivar. Furthermore, we identified a total of 22 lncRNAs that were differentially expressed across all treatment conditions. WGCNA identified 11 modules enriched in drought-responsive pathways. Additionally, the target genes of trans/cis-regulated lncRNAs predominantly exhibited functions related to stress responses. Twelve DElncRNA-PCG pairs were identified as having the same expression pattern, and several PCGs were found to act as transcription factors, indicating their potential cis-regulatory roles in drought-responsive pathways. Furthermore, qRT-PCR validation confirmed the reliability of the expression patterns observed in this study. The study is the first to systematically reveal the expression characteristics of lncRNAs in hulless barley under drought stress, providing an important foundation for further research on the role of lncRNAs in plant drought tolerance mechanisms and offering targets for crop improvement strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Table S1. Transcriptome-wide information for 2877 long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) transcripts in two cultivars of hulless barley;

Table S2. Molecular length characteristics of lncRNAs;

Table S3. Distribution pattern of exon numbers among lncRNAs;

Table S4. Allocation of lncRNAs class_code;

Table S5. Unique and shared lncRNAs expressed in two cultivars of hulless barley;

Table S6. The expression distribution and patterns of lncRNAs in two hulless barely cultivars;

Table S7. DElncRNAs, we found in two cultivars under different drought treatments;

Table S8. Hierarchical cluster tree and color bands showing the 11 modules by WGCNA;

Table S9. Up/downregulated DElncRNAs under drought stress in two hulless barley cultivars;

Table S10. The count of unique and shared upregulated and downregulated DElncRNAs in different drought treatments between the two cultivars;

Table S11. The count of unique and shared upregulated and downregulated DElncRNAs in different drought treatments in the two cultivars, respectively;

Table S12. Cis-regulated target PCGs and their DElncRNAs;

Table S13. Number of DElncRNA-PCG pairs in different treatment groups;

Table S14. The expression patterns of DEPCGs of DElncRNA;

Table S15. Expression profile and function annotated of 12 co-expressed lncRNA-PCGs pairs under different drought treatment conditions;

Table S16. PCR primers for the target genes.

Author Contributions

Z. W.: conceptualization, data curation, software, investigation, methodology, and writing-original manuscript; Y. F.: data curation, software, investigation, and writing-original manuscript; Q. M.: investigation, methodology, and writing-review manuscript; K. Z.: conceptualization, data curation and investigation; Y. P.: investigation and methodology; J. C.: methodology and project administration; F, Q, investigation, project administration, supervision and writing—review and editing; S.H.: funding acquisition, conceptualization, project administration, supervision, and writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Department of Qinghai Province of China (Grant No. 2023-ZJ-706), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32270346), and Qinghai “Kunlun Talents • High End Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talents” Featured Grant to Shengcheng Han. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Shafiq, S.; Li, J.; Sun, Q. Functions of plants long non-coding RNAs. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2016, 1859, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaduwage, I.; Hewadikaram, M. Predicted roles of long non-coding RNAs in abiotic stress tolerance responses of plants. Molecular horticulture 2024, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palos, K.; Yu, L.; Railey, C.E.; Nelson Dittrich, A.C.; Nelson, A.D.L. Linking discoveries, mechanisms, and technologies to develop a clearer perspective on plant long noncoding RNAs. The Plant cell 2023, 35, 1762–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.K.; Wang, H. Computational Analysis Predicts Hundreds of Coding lncRNAs in Zebrafish. Biology 2021, 10, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, T.; Chang, H.Y. Long noncoding RNA in genome regulation: Prospects and mechanisms. RNA biology 2010, 7, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Yuan, C.; Zhou, Y.F.; Huang, Q.J.; Zhao, W.L.; He, R.R.; Jiang, J.; Qin, Y.C.; Chen, Z.T.; Zhang, Y.C.; Lei, M.Q.; Lian, J.P.; Chen, Y.Q. The long non-coding RNA VIVIpary promotes seed dormancy release and pre-harvest sprouting through chromatin remodeling in rice. Molecular plant 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, T.; Zhao, H.; Cui, P.; Albesher, N.; Xiong, L. A Nucleus-Localized Long Non-Coding RNA Enhances Drought and Salt Stress Tolerance. Plant physiology 2017, 175, 1321–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhu, P.; Hepworth, J.; Bloomer, R.; Antoniou-Kourounioti, R.L.; Doughty, J.; Heckmann, A.; Xu, C.; Yang, H.; Dean, C. Natural temperature fluctuations promote COOLAIR regulation of FLC. Genes & development 2021, 35, 888–898. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, X.; Gao, H.; Liu, W.; Jing, Y.; Saxena, R.K.; Feng, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H. Soybean F-Box-Like Protein GmFBL144 Interacts With Small Heat Shock Protein and Negatively Regulates Plant Drought Stress Tolerance. Frontiers in plant science 2022, 13, 823529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Rico-Medina, A.; Caño-Delgado, A.I. The physiology of plant responses to drought. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2020, 368, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Functional genomics in plant abiotic stress responses and tolerance: From gene discovery to complex regulatory networks and their application in breeding. Proceedings of the Japan Academy. Series B, Physical and biological sciences 2022, 98, 470–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Ai, Q.; Wong, D.C.J.; Zhang, F.; Yang, J.; Zhang, N.; Si, H. Current perspectives of lncRNAs in abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in plants. Frontiers in plant science 2023, 14, 1334620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Dwivedi, S.; Bhagavatula, L.; Datta, S. Integration of light and ABA signaling pathways to combat drought stress in plants. Plant cell reports 2023, 42, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Aslam, M.; Waseem, M.; Jakada, B.H.; Okal, E.J.; Lei, Z.; Saqib, H.S.A.; Yuan, W.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Q. Mechanisms of Abscisic Acid-Mediated Drought Stress Responses in Plants. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgil, H.; Tardu, M.; Cevahir, G.; Kavakli, İ.H. Comparative RNA-seq analysis of the drought-sensitive lentil (Lens culinaris) root and leaf under short- and long-term water deficits. Functional & integrative genomics 2019, 19, 715–727. [Google Scholar]

- Sobreiro, M.B.; Collevatti, R.G.; Dos Santos, Y.L.A.; Bandeira, L.F.; Lopes, F.J.F.; Novaes, E. RNA-Seq reveals different responses to drought in Neotropical trees from savannas and seasonally dry forests. BMC plant biology 2021, 21, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, J.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X.; Zhao, J. Spatio-Temporal Transcriptional Dynamics of Maize Long Non-Coding RNAs Responsive to Drought Stress. Genes 2019, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yang, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Huo, H.; Zhang, C.; Liu, A.; Zhu, A.; Hu, J.; Lin, Y.; Liu, L. Physiological and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal Short-Term Responses and Formation of Memory Under Drought Stress in Rice. Frontiers in genetics 2019, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohra, A.; Choudhary, M.; Bennett, D.; Joshi, R.; Mir, R.R.; Varshney, R.K. Drought-tolerant wheat for enhancing global food security. Functional & integrative genomics 2024, 24, 212. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.L.; Wei, Z.X.; Xu, Q.J.; Zeng, X.Q.; Yuan, H.J.; Tang, Y.W.; Tashi, N. The complete mitochondrial genome of Tibetan hulless barley. Mitochondrial DNA. Part B, Resources 2016, 1, 430–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Long, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Tang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Mao, L.; Deng, G.; Yao, X.; Li, X.; Bai, L.; Yuan, H.; Pan, Z.; Liu, R.; Chen, X.; WangMu, Q.; Chen, M.; Yu, L.; Liang, J.; DunZhu, D.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, S.; LuoBu, Z.; Guang, X.; Li, J.; Deng, C.; Hu, W.; Chen, C.; TaBa, X.; Gao, L.; Lv, X.; Abu, Y.B.; Fang, X.; Nevo, E.; Yu, M.; Wang, J.; Tashi, N. The draft genome of Tibetan hulless barley reveals adaptive patterns to the high stressful Tibetan Plateau. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2015, 112, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Yao, Y.; An, L.; Li, X.; Bai, Y.; Cui, Y.; Wu, K. Accumulation and regulation of anthocyanins in white and purple Tibetan Hulless Barley (Hordeum vulgare L. var. nudum Hook. f.) revealed by combined de novo transcriptomics and metabolomics. BMC plant biology 2022, 22, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, N.; Yue, X. Distribution of Core Root Microbiota of Tibetan Hulless Barley along an Altitudinal and Geographical Gradient in the Tibetan Plateau. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, L. Identification and expression analysis of miRNAs in germination and seedling growth of Tibetan hulless barley. Genomics 2021, 113, 3735–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Wu, X.; Xue, X.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, F.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, F.; Han, S. Transcriptome Screening of Long Noncoding RNAs and Their Target Protein-Coding Genes Unmasks a Dynamic Portrait of Seed Coat Coloration Associated with Anthocyanins in Tibetan Hulless Barley. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 10587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Chen, X.; Deng, G.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Yang, K.; Long, H.; Yu, M. Dehydration induced transcriptomic responses in two Tibetan hulless barley (Hordeum vulgare var. nudum) accessions distinguished by drought tolerance. BMC genomics 2017, 18, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, K.F.; Waugh, R.; Brown, J.W.; Schulman, A.; Langridge, P.; Platzer, M.; Fincher, G.B.; Muehlbauer, G.J.; Sato, K.; Close, T.J.; Wise, R.P.; Stein, N. A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome. Nature 2012, 491, 711–716. [Google Scholar]

- Holm, K.M.; Koepfli, K.P.; Pukazhenthi, B.S.; Ratan, A.; Fryxell, K.J.; Pham, M.; Weisz, D.; Dudchenko, O.; Aiden, E.L.; Lim, H.C. Chromosome-length genome assembly of the critically endangered Mountain bongo (Tragelaphus eurycerus isaaci): A resource for conservation and comparative genomics. G3 (Bethesda, Md.) 2025, jkaf109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Chen, X.; Deng, G.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Yang, K.; Long, H.; Yu, M. Dehydration induced transcriptomic responses in two Tibetan hulless barley (Hordeum vulgare var. nudum) accessions distinguished by drought tolerance. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, C.S.; Marz, M.; Rose, D.; Hertel, J.; Brindley, P.J.; Santana, C.B.; Kehr, S.; Attolini, C.S.-O.; Stadler, P.F. Homology-based annotation of non-coding RNAs in the genomes of Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum. BMC Genomics 2009, 10, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engreitz, J.M.; Haines, J.E.; Perez, E.M.; Munson, G.; Chen, J.; Kane, M.; McDonel, P.E.; Guttman, M.; Lander, E.S. Local regulation of gene expression by lncRNA promoters, transcription and splicing. Nature 2016, 539, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, R.D.; Wendelboe-Nelson, C.; Morris, P.C. The barley transcription factor HvMYB1 is a positive regulator of drought tolerance. Plant physiology and biochemistry : PPB 2019, 142, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Pei, W.; Wan, K.; Pan, R.; Zhang, W. LncRNA cis- and trans-regulation provides new insight into drought stress responses in wild barley. Physiologia plantarum 2024, 176, e14424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, I.K.; Russell, J.; Powell, W.; Steffenson, B.; Thomas, W.T.B.; Waugh, R. Barley: A translational model for adaptation to climate change. The New phytologist 2015, 206, 913–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.; Khemka, N.; Rajkumar, M.S.; Garg, R.; Jain, M. PLncPRO for prediction of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in plants and its application for discovery of abiotic stress-responsive lncRNAs in rice and chickpea. Nucleic acids research 2017, 45, e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Zhang, Y.; He, R.; Jiang, L.; Qu, Z.; Gu, J.; Yang, J.; Legascue, M.F.; Wang, Z.Y.; Ariel, F.; Adelson, D.L.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, D. LncRNA DANA1 promotes drought tolerance and histone deacetylation of drought responsive genes in Arabidopsis. EMBO reports 2024, 25, 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.; Zheng, K.; Min, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xue, X.; Li, W.; Zhao, H.; Qiao, F.; Han, S. Long Noncoding RNAs in Response to Hyperosmolarity Stress, but Not Salt Stress, Were Mainly Enriched in the Rice Roots. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25, 6226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Q.; Zheng, K.; Liu, T.; Wang, Z.; Xue, X.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, F.; Chen, J.; Su, X.; Han, S. Transcriptomic Profiles of Long Noncoding RNAs and Their Target Protein-Coding Genes Reveals Speciation Adaptation on the Qinghai-Xizang (Tibet) Plateau in Orinus. Biology 2024, 13, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Xu, T.; Ling, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, S.; Xu, Q.; Zha, S.; Qimei, W.; Basang, Y.; Dunzhu, J.; Yu, M.; Yuan, H.; Nyima, T. An improved high-quality genome assembly and annotation of Tibetan hulless barley. Scientific data 2020, 7, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.F.; Zhang, Y.C.; Sun, Y.M.; Yu, Y.; Lei, M.Q.; Yang, Y.W.; Lian, J.P.; Feng, Y.Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L.; He, R.R.; Huang, J.H.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y.W.; Chen, Y.Q. The parent-of-origin lncRNA MISSEN regulates rice endosperm development. Nature communications 2021, 12, 6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, C.; Niu, X.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Yuan, Q.; Pei, X. Research on lncRNA related to drought resistance of Shanlan upland rice. BMC genomics 2022, 23, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, M.C.; Daulagala, A.C.; Kourtidis, A. LNCcation: lncRNA localization and function. The Journal of cell biology 2021, 220, e202009045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Fu, H.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, X. Function of lncRNAs and approaches to lncRNA-protein interactions. Science China. Life sciences 2013, 56, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Hou, X.L.; Xing, G.M.; Liu, J.X.; Duan, A.Q.; Xu, Z.S.; Li, M.Y.; Zhuang, J.; Xiong, A.S. Advances in AP2/ERF super-family transcription factors in plant. Critical reviews in biotechnology 2020, 40, 750–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubos, C.; Stracke, R.; Grotewold, E.; Weisshaar, B.; Martin, C.; Lepiniec, L. MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends in plant science 2010, 15, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Kumari, S.; Olson, A.; Hauser, F.; Ware, D. Role of a ZF-HD Transcription Factor in miR157-Mediated Feed-Forward Regulatory Module That Determines Plant Architecture in Arabidopsis. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 8665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, Q.; Zheng, K.; Pang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, F.; Su, X.; Chen, J.; Han, S. Transcription factors in Orinus: Novel insights into transcription regulation for speciation adaptation on the Qinghai-Xizang (Tibet) Plateau. BMC plant biology 2025, 25, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Yuan, P.; Gao, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Jiao, J.; Zhang, K.; Hao, P.; Song, C.; Zheng, X.; Bai, T. The AP2/ERF transcription factor MhERF113-like positively regulates drought tolerance in transgenic tomato and apple. Plant physiology and biochemistry : PPB 2025, 221, 109598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Lv, Q.; Wang, L.; Han, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, X.; Bao, F.; Hu, Y.; Li, L.; He, Y. Abscisic acid-mediated autoregulation of the MYB41-BRAHMA module enhances drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant physiology 2024, 196, 1608–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Dong, H.; Li, J.; Dai, X.; Lin, J.; Li, S.; Zhou, C.; Chiang, V.L.; Li, W. PtrVCS2 Regulates Drought Resistance by Changing Vessel Morphology and Stomatal Closure in Populus trichocarpa. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mráz, P.; Tarbush, E.; Müller-Schärer, H. Drought tolerance and plasticity in the invasive knapweed Centaurea stoebe s.l. (Asteraceae): Effect of populations stronger than those of cytotype and range. Annals of botany 2014, 114, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, S.; Sun, X.; Khan, N.U.; Zhong, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Ming, F.; Li, Z.; Li, J. Variations in OsSPL10 confer drought tolerance by directly regulating OsNAC2 expression and ROS production in rice. Journal of integrative plant biology 2023, 65, 918–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Deng, G.; Long, H.; Pan, Z.; Wang, C.; Cai, P.; Xu, D.; Nima, Z.-X.; Yu, M. Virus-induced silencing of genes encoding LEA protein in Tibetan hulless barley (Hordeum vulgare ssp. vulgare) and their relationship to drought tolerance. Molecular Breeding 2011, 30, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, W.B. Performance of genetic programming optimised Bowtie2 on genome comparison and analytic testing (GCAT) benchmarks. BioData mining 2015, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Pertea, G.; Trapnell, C.; Pimentel, H.; Kelley, R.; Salzberg, S.L. TopHat2: Accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome biology 2013, 14, R36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Roberts, A.; Goff, L.; Pertea, G.; Kim, D.; Kelley, D.R.; Pimentel, H.; Salzberg, S.L.; Rinn, J.L.; Pachter, L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nature protocols 2012, 7, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandawala, M.; Bilal Amir, M.; Shin, J.; Yim, W.C.; Alfonso Yañez Guerra, L. Proteome-wide neuropeptide identification using NeuroPeptide-HMMer (NP-HMMer). General and comparative endocrinology 2024, 357, 114597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Chuguransky, S.; Williams, L.; Qureshi, M.; Salazar, G.A.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; Tosatto, S.C.E.; Paladin, L.; Raj, S.; Richardson, L.J.; Finn, R.D.; Bateman, A. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic acids research 2021, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.J.; Yang, D.C.; Kong, L.; Hou, M.; Meng, Y.Q.; Wei, L.; Gao, G. CPC2: A fast and accurate coding potential calculator based on sequence intrinsic features. Nucleic acids research 2017, 45, W12–W16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, A.R.; Hall, I.M. BEDTools: A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2010, 26, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Molecular plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC bioinformatics 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional Annotation, Orthology Assignments, and Domain Prediction at the Metagenomic Scale. Molecular biology and evolution 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).