1. Introduction

Climate change-driven water stress poses a significant threat to global plant life, with drought being the most widespread water-related climate disaster and waterlogging ranking as the second [

1]. Upon facing drought, plants exhibit a number of defense mechanisms, such as reduced stomatal conductance and a corresponding decrease in photosynthetic rate. This cascade of events can result in oxidative stress due to the build-up of reactive oxygen species (ROS), ultimately leading to inhibited growth and, in severe cases, plant mortality [

2]. Also, the onset of waterlogging triggers stress in plants as the water-saturated soil leads to oxygen deprivation, which in turn severely compromises root respiration [

3]. While plants employ different defense mechanisms for drought and waterlogging, a central component of their tolerance is the upregulation of antioxidant enzymes to reduce cellular damage caused by these stresses [

1]. Moreover, plant hormones such as ethylene have been shown to positively influence plant resistance to both drought and waterlogging stresses [

4,

5]. Although studying the resistance mechanisms for drought and waterlogging stresses individually is important, focusing on their common underlying mechanisms can lead to effective breeding for the climate change era.

The perennial plant, Longleaf Speedwell (

Psuedolysimachion longifolium), is natively distributed across a wide range, from Europe to the Korean Peninsula [

6]. Because of its notable ornamental and medicinal potential, the plant has been the subjects of diverse scientific studies [

7,

8,

9]. Recently, native plants have been attracting attention as a crucial resource for developing new horticultural varieties to cope with climate change, and the necessity for breeding research for climate change adaptation has also been raised in studies targeting native Korean Poaceae plants [

10]. Additionally, research on other native Korean plants has investigated their tolerance to various abiotic stresses, such as salinity, which suggests the importance of studying their genetic, protein, and transcriptional responses for climate change adaptation [

11]. However, researches on genetic response of

P. longifolium to environmental stresses are missing yet.

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) provides a powerful advantage by quantitatively measuring gene expression, which helps to clarify the molecular-level responses of plants to environmental stress [

12]. Unlike traditional PCR-based methods that target specific genes, RNA-Seq allows for a comprehensive analysis of the entire transcriptome, enabling the simultaneous discovery of diverse genes and gene networks that respond to stress [

13]. For non-model plants like

Pseudolysimachion longifolium that lack a reference genome,

de novo transcriptome assembly can be utilized to construct genetic information and enable molecular studies on species that have been understudied [

14]. RNA-Seq has been instrumental in studying abiotic stress responses in plants, such as investigating drought resistance in cassava leaves [

15] and flood tolerance in wheat leaves [

16]. Furthermore, Baldi et al. [

17] identified molecular responses to drought and waterlogging stresses of kiwifruit (

Actinidia chinensis var.

deliciosa) using RNA-Seq. Consequently, RNA-Seq is a highly effective method for elucidating the genetic responses of

Pseudolysimachion longifolium to drought and waterlogging stresses.

This study aimed to elucidate the genetic mechanisms of P. longifolium in response to drought and waterlogging stress. We hypothesized that the genes expressed under each stress condition are distinct. To test this, we first performed RNA-Seq analysis to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) specific to each stress. Second, we functionally characterized these genes through gene annotation and GO/KEGG analysis. Finally, we validated the reliability of our RNA-Seq data by performing qRT-PCR on key candidate genes, thereby identifying genes associated with drought and waterlogging tolerance in P. longifolium.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Treatments

The study was performed at the Forest Biological Resources Utilization Center of the Korea National Arboretum. P. longifolium was collected from Gurye-gun, Jeollanam-do, Korea (35°17’37.1”N 127°31’34.6”E). The collected plants were propagated by seed and cutting method at the Forest Biological Resources Utilization Center of the Korea National Arboretum. A specimen of P. longifolium was deposited at the Korea National Arboretum (Dr. Dong Chan Son, sdclym@korea.kr) with the voucher number KHB1663331. Seedlings were transplanted to square pots (12 cm × 12 cm × 15.5 cm) containing horticultural soil (Superbaroker, Seoul Bio Co., Korea).

At the flowering stage, P. longifolium were exposed to drought or waterlogging for 2 weeks. Control pots got watered normally once every 2 days for 2 weeks instead of stress treatment. Drought stress was applied by withholding water for the 2-weeks period; however, a minimal amount of water was supplied after the first week (Day 7) to prevent complete plant morality and ensure sufficient biological material for the 2-week physiological and transcriptomic sampling. Waterlogging stress was treated by placing the pots in a water-filled container to a depth of approximately 2 cm above the soil surface for 2 weeks. At least five plants of each experimental group were assigned.

Soil water content was monitored continuously throughout the 2-week treatment period. Volumetric water content (θv) was recorded hourly using a data logger (WatchDog 1650, Spectrum Technologies, Inc., Aurora, IL, USA) equipped with soil moisture sensors.

2.2. Plant Phenotypic Measurements and Chlorophyll Fluorescence

SPAD values were measured on fully expanded leaves after one week of treatment using a portable chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502, Konica Minolta, Japan). Plant fresh weight (FW) and dry weight (DW) were measured immediately after the 2-week treatment period. Dry weight was determined after drying the plant samples in an oven at 80ºC until a constant weight was achieved.

Chlorophyll

a fluorescence was measured using a pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM) fluorometer (PAM-2500, Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany). Measurements were conducted on fully expanded leaves sampled from the control, drought, and waterlogging groups after the 1-week treatment period to assess the early photosynthetic impact. Before measurement, leaves were dark-adapted for 20 minutes to ensure full oxidation of the primary electron acceptor (Q

A). The maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (F

v/F

m) was calculated as (F

m-F

o)/F

m, where F

o is the minimum fluorescence and F

m is the maximum fluorescence in the dark-adapted state. The effective quantum yield of photosystem II (Φ

PSII) was measured under actinic light and calculated as (F

m’-F

s)/F

m’. The electron transport rate (ETR) was then estimated using the formula ETR = Φ

PSII × PAR × 0.5 × absorption, assuming an average leaf absorption of 0.84 and partitioning light energy equally between PSII and PSI (0.5) [

18,

19].

2.3. RNA Isolation and Sequencing

The leaf was sampled, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C until RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using the Maxwell RSC Plant RNA Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA concentration was determined using Quant-IT RiboGreen (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA integrity was assessed on the TapeStation RNA ScreenTape (Agilent), and only high-quality RNA with a RIN value greater than 7.0 was used for library construction. For each sample, an RNA library was independently prepared with 1 µg of total RNA using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The workflow involved purifying poly-A-containing mRNA using poly-T-attached magnetic beads, followed by mRNA fragmentation using divalent cations. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and random primers, and second-strand cDNA was synthesized using DNA Polymerase I, RNase H, and dUTP. The resulting cDNA fragments were then subjected to end repair, A-base addition, and adapter ligation. The final cDNA libraries were purified and enriched via PCR. Libraries were quantified using KAPA Library Quantification kits for Illumina sequencing platforms (KAPA BIOSYSTEMS) and qualified using the TapeStation D1000 ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies). Paired-end (2×100 bp) sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeqX (Illumina Inc.) by Macrogen Incorporated.

Raw sequencing reads were preprocessed to remove low-quality and adapter sequences. The processed reads were assembled

de novo into unigenes using the Trinity program [

20]. Read alignment and abundance estimation were performed on the unigenes using Bowtie v1.1.2 [

21] and RSEM v1.3.1 [

22]. The expression level of each unigene was calculated using the Fragments Per Kilobase of exon per Million mapped fragments (FPKM) method. For functional annotation, the unigenes were blasted against public databases including NCBI Nucleotide (NT), NCBI non-redundant Protein (NR), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Pfam, Gene Ontology (GO), UniProt, and EggNOG. Based on the annotation results, contigs annotated as fungal, bacterial, or animal-related were excluded from further analysis to ensure the focus on

P. longifolium transcripts.

Relative abundances were measured in read counts using RSEM. Statistical analysis was performed using DESeq2 to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs). A false discovery rate (FDR) was controlled by an adjusted p-value using the Benjamini-Hochberg algorithm. Enrichment of GO and KEGG analysis was carried out and visualized using R 4.5.1.

2.4. qRT-PCR Validation

To validate the expression patterns of key genes identified through RNA-Seq, 3 genes with significant differential expression were selected for quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Gene-specific primers were designed based on the sequences obtained from the

de novo analysis using NCBI Primer-BLAST program (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) (

Table 1). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from the same RNA samples of RNA-Seq analysis using the PrimeScript™ 1st strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara Bio Inc, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. qRT-PCR was carried out on a CFX Duet real-time PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) in a 10 μL reaction mixture, containing 5 μL of BrightGreen 2× qPCR MasterMix-No Dye (Applied Biological Materials, Richmond, Canada), 500 nM of each primer, and 1 μL of template cDNA (diluted 1:10). Gene expression levels were established based on the quantitation cycle (Cq). The Cq values were established using Bio-Rad CFX Manager 3.1 (BioRad Laboratories), and the results were calculated using the 2

-ΔΔCq method [

23]. Pearson correlation coefficients were then calculated between the transcripts per million (TPM) values from RNA-Seq and the expression levels from qRT-PCR for each gene.

4. Discussion

The results determine the genetic response of

P. longifolium leaf under two extreme and contrasting water regimes, drought and waterlogging. The present study successfully imposed clear and contrasting water stresses on

P. longifolium, as confirmed by the significant differences in soil water content (

θv) after the two-week treatment period. The severe reduction in

θv in the drought group (~ 1.44%) and the maintenance of saturated conditions in the waterlogging group (~ 58.57%) confirmed the suitability of the experimental setup for investigating these two major abiotic stresses. Plant responses and adaptation mechanisms to both drought and waterlogging stresses are critical areas of research in water stress physiology, and are essential for breeding water-tolerant varieties [

1].

Phenotypic analysis revealed that both drought and waterlogging significantly compromised plant vigor. Both fresh weight (FW) and dry weight (DW) were highest in the control and significantly reduced in both stress groups, indicating a rapid, non-specific arrest of growth. Photosynthetic efficiency, a key indicator of plant health, was also severely impaired. After one week of stress, both chlorophyll content (SPAD) and the maximum quantum yield of Photosystem II (F

v/F

m) showed a sharp decline. Importantly, the consistent statistical grouping (b) across all physiological and growth metrics (FW, DW, SPAD, and F

v/F

m) in both stress treatments indicated an equivalent overall physiological impairment under both dehydration and hypoxia. This rapid and comparable physiological deterioration underscores the sensitivity of

P. longifolium to abrupt changes in soil moisture. Indeed, a study on cherry trees (

Prunus yedoensis) found that while both stresses caused rapid physiological decline (similar to our findings), overall growth indices such as total dry weight were most severely reduced by waterlogging stress, highlighting a potentially greater long-term vulnerability to hypoxia in that species compared to drought [

24].

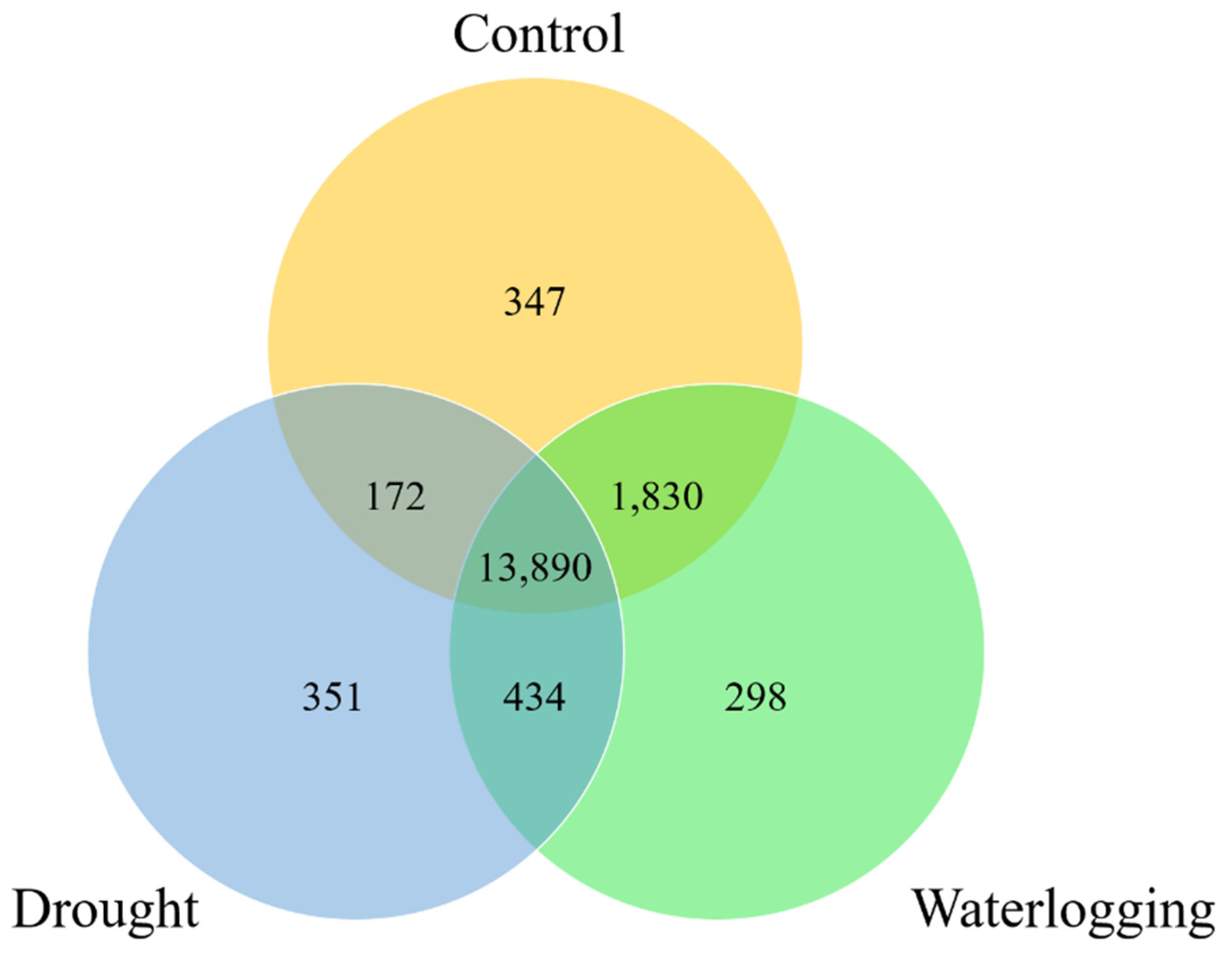

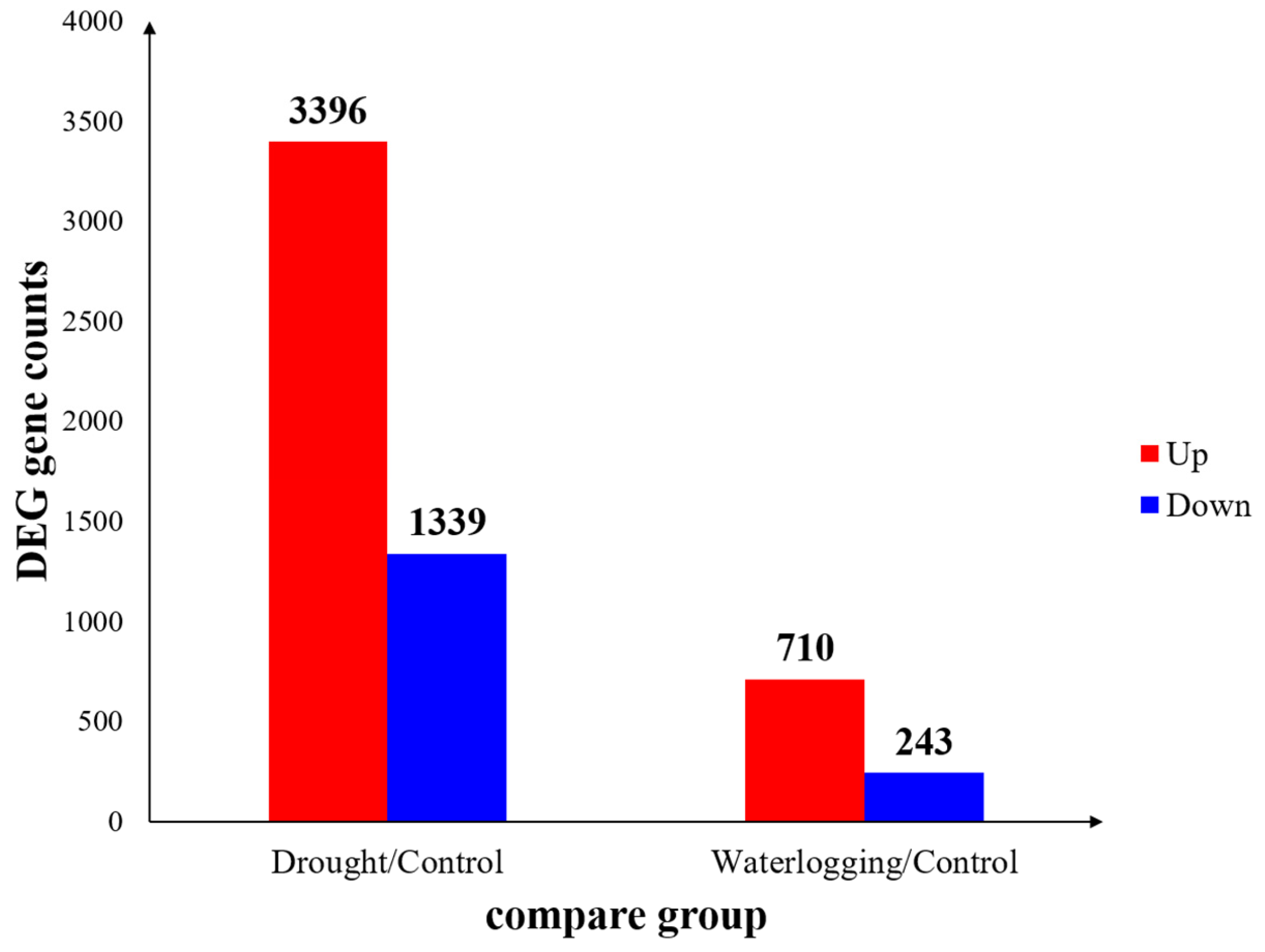

While both stresses led to comparable physiological damage, the global transcriptome analysis revealed a profoundly differential molecular response. Drought stress induced the differential expression of 4,735 genes (DEGs) compared to the control, a number approximately five times higher than the 953 DEGs observed under waterlogging stress. This significant disparity suggests that drought triggers a far more extensive and pervasive molecular reprogramming cascade than waterlogging in

P. longifolium. The initial comparison showed a comparatively low number of shared expressed genes between the control and drought groups, while the control and waterlogging groups shared a significantly higher number of genes. This indicates that the gene expression profile under waterlogging remains relatively closer to the basal state compared to the massive shift observed under drought. This difference may reflect

P. longifolium’s inherent tolerance or specific molecular mechanisms for coping with moderate waterlogging, requiring fewer widespread transcriptional changes than the highly damaging dehydration caused by drought. This finding is consistent with transcriptomic studies in other plant species, such as kiwifruit, where the molecular response to waterlogging was also reported to be less intense and involve fewer differentially expressed genes compared to drought stress [

17].

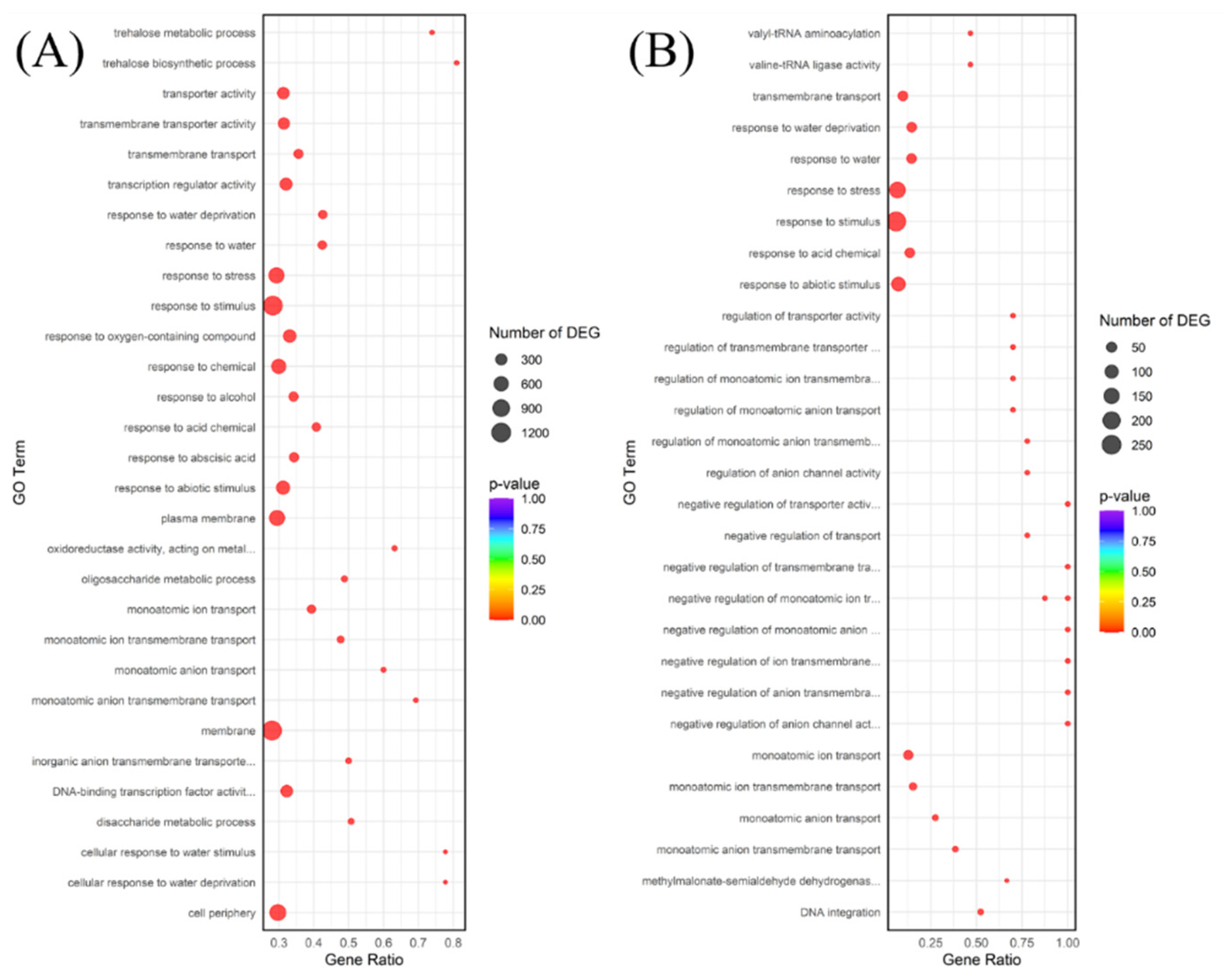

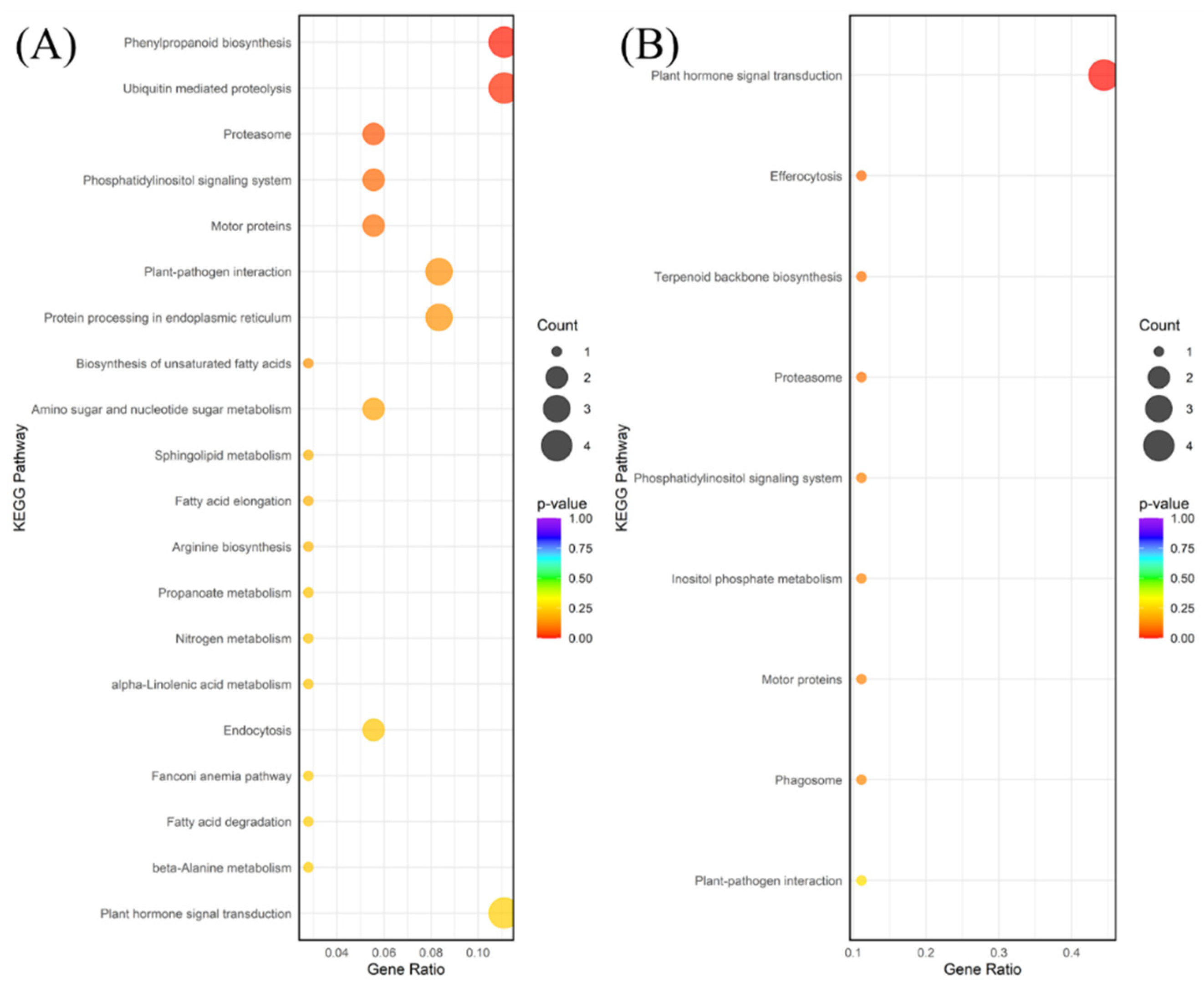

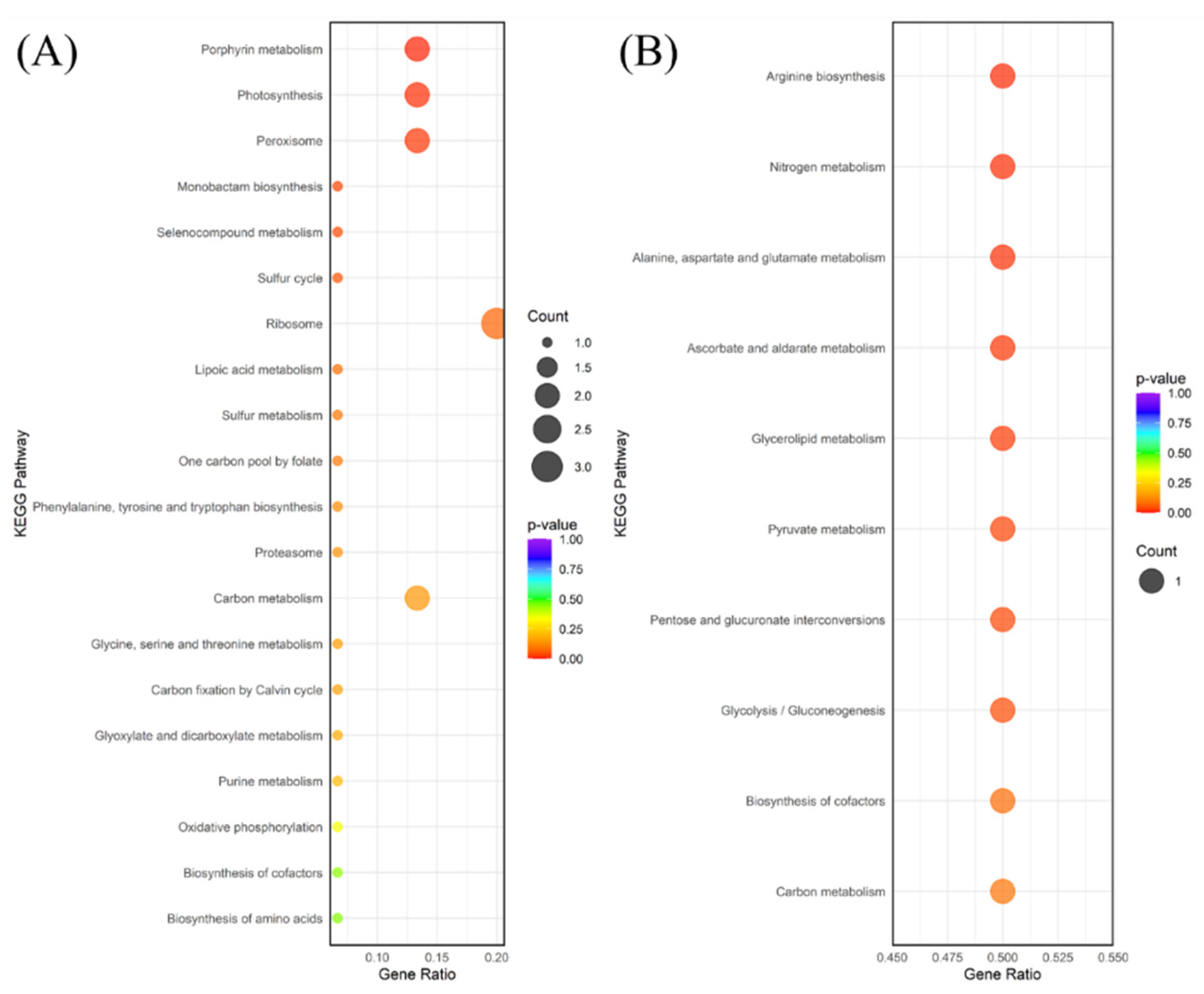

Functional enrichment analysis, including both GO and KEGG pathway analysis, provides complementary insights into the biological implications of DEGs [

25]. While GO terms provided a general overview of affected cellular components, molecular functions, and biological processes (e.g., ‘oxidation-reduction process,’ ‘response to abscisic acid stimulus’), the subsequent discussion focuses on the KEGG pathway enrichment results. This is because KEGG offers a more detailed, mechanistic view by mapping DEGs onto specific, well-defined metabolic and signal transduction pathways, allowing for a clearer, biochemically grounded interpretation of the plant’s adaptation strategies. KEGG is generally preferred for exploring metabolic and signaling interactions as it organizes genes into broader, systemic pathway diagrams, unlike the more fragmented, ontology-based classification provided by GO [

26]. The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis confirmed that

P. longifolium employs highly specialized and contrasting molecular strategies to survive drought and waterlogging.

The molecular response to drought was characterized by an active defense mechanism coupled with a pervasive suppression of core metabolic processes. Upregulated pathways were dominated by Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (ko00940), Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis (ko04120), and Plant hormone signal transduction (ko04075) (

Figure 4A). The enhancement of Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis is crucial, as its products (lignin, flavonoids) are central to cell wall reinforcement and the scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to reduce oxidative damage caused by dehydration [

27]. This role is well-established, as the phenylpropanoid pathway is typically activated under abiotic stress to detoxify ROS and protect cellular components [

28]. The enrichment of the Ubiquitin system highlights the plant’s need for rapid protein quality control, recycling, and the degradation of regulatory proteins essential for stress adaptation [

29]. The hormone signal transduction pathway is typically associated with ABA signaling, which is the master regulator for drought, controlling stomatal closure and inducing stress-responsive gene expression [

30].

Conversely, the most significantly downregulated pathways included high-energy, growth-related processes such as Ribosome (ko03010), Carbon metabolism (ko01200), and Photosynthesis (ko00195) (

Figure 5A). This widespread transcriptional suppression of protein synthesis and primary energy capture systems is the molecular hallmark of a severe growth-arrest strategy, aimed at minimizing water and energy expenditure under conditions of extreme scarcity [

31]. This aggressive resource conservation aligns with the observed severe reduction in FW and DW.

The waterlogging response, while inducing fewer DEGs, was specific and focused on adapting to low-oxygen conditions. Upregulated pathways included Plant hormone signal transduction (ko04075) and Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (ko00900) (

Figure 4B). In waterlogging, the hormone signaling pathway often involves ethylene and auxin, which mediate morphological adaptations such as aerenchyma formation and adventitious root development, critical for oxygen supply under hypoxia. Ethylene accumulation is recognized as a rapid and reliable signal for initiating these flood-adaptive traits [

32]. The downregulation of pathways like Nitrogen metabolism (ko00910) and Arginine biosynthesis (ko00220) suggests a critical shutdown of resource-demanding synthesis processes, allowing the plant to conserve energy and shift metabolic resources toward immediate survival mechanisms under anaerobic conditions [

33].

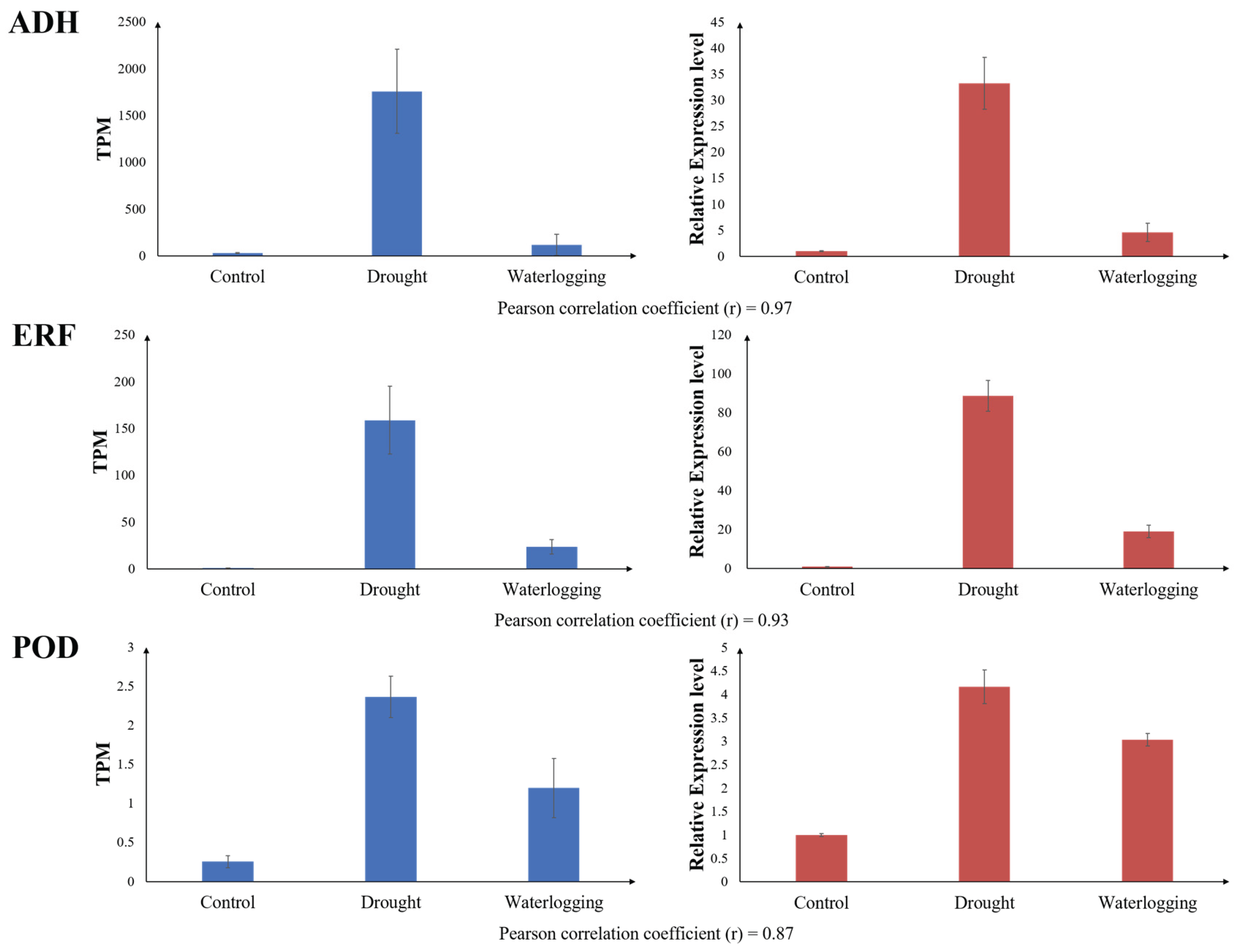

The qRT-PCR validation confirmed the high reliability of the RNA-Seq data (Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.97 for ADH, 0.93 for ERF, and 0.87 for POD). Furthermore, the expression patterns of these three genes are highly notable. All three genes were significantly upregulated under both drought and waterlogging conditions, with the highest expression observed under drought stress. This suggests they play a crucial role in the common or interconnected stress-response network in P. longifolium.

The strong upregulation of ADH (Alcohol dehydrogenase) is a classic indicator of anaerobic fermentation under waterlogging stress, essential for maintaining NAD

+ regeneration and detoxifying acetaldehyde [

5]. However, ADH can also contribute to drought resistance [

34]. Its highest expression under drought suggests an unexplored function in dehydration stress, possibly related to ethanol-mediated signaling or protection.

ERF (Ethylene Responsive Factor) transcription factors are directly involved in the regulation of waterlogging stress through ethylene signaling [

5]. ERF also plays a crucial role in plant drought resistance by regulating the expression of various stress-responsive genes [

35]. Its dual upregulation confirms its pivotal role as a signaling node managing adaptation to both stresses.

POD (Peroxidase) activity is central to mitigating oxidative damage, a common consequence of both drought (due to ROS accumulation from suppressed photosynthesis) and waterlogging (due to reoxygenation injury). In maize (

Zea mays), POD appeared to enhance both drought tolerance and waterlogging tolerance [

36]. The high induction of POD in

P. longifolium suggests a vital and generalized role in cellular protection against the distinct ROS production mechanisms induced by each stress.

In summary, P. longifolium utilizes fundamentally distinct molecular strategies to cope with water stress. Drought induced a massive transcriptional upheaval (~ 5× DEGs), focusing on robust defense (Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis) while severely shutting down growth (Ribosome, Photosynthesis). Conversely, waterlogging triggered a more constrained hypoxic response that prioritized energy conservation by downregulating resource-intensive synthesis and activating key ethylene signaling. Critically, the identification of Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), Ethylene Responsive Factor (ERF), and Peroxidase (POD) as commonly induced genes highlights their potential as targets for broad-spectrum water stress tolerance. These findings provide essential genetic mechanisms for P. longifolium’s adaptation.