Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

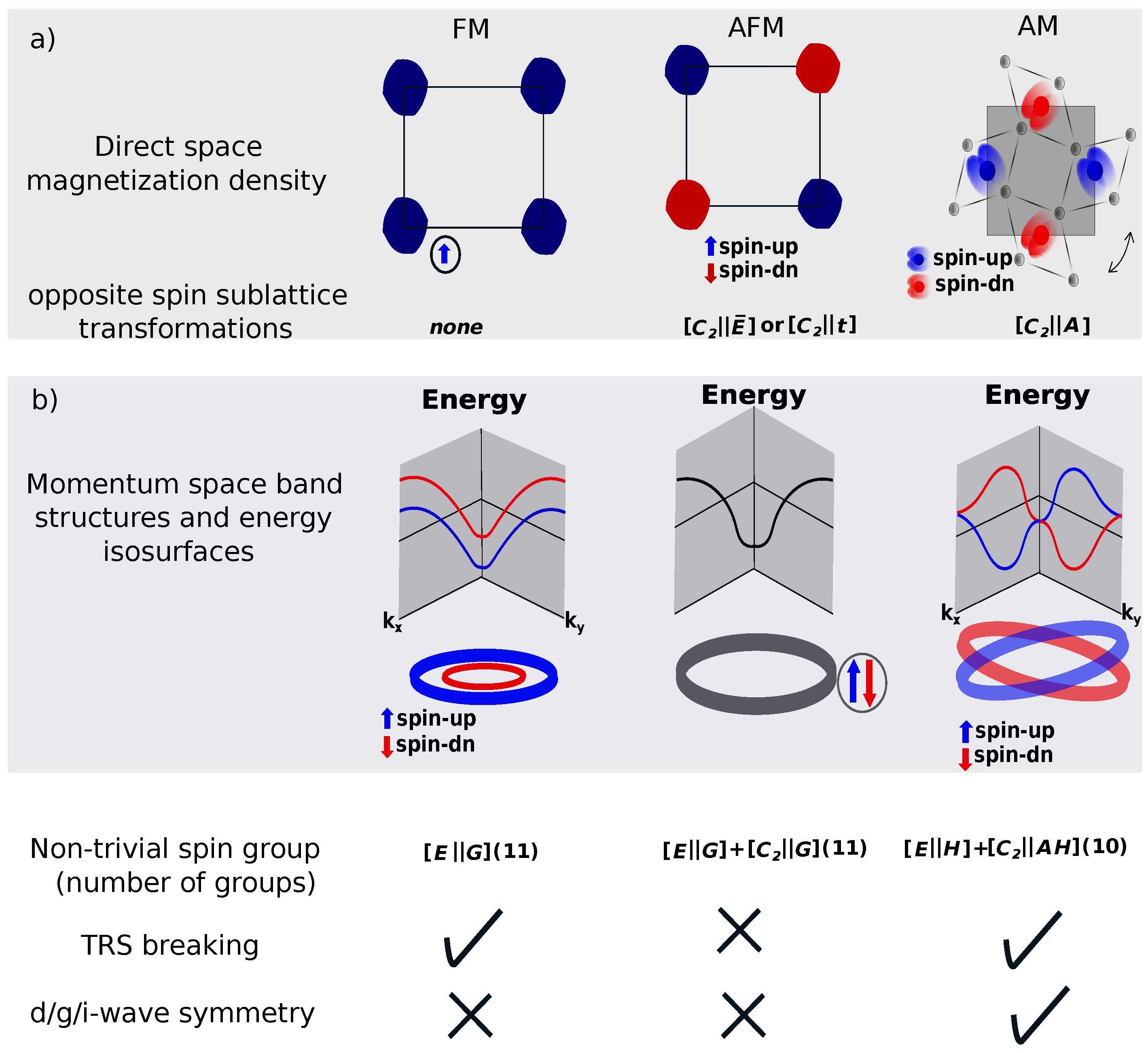

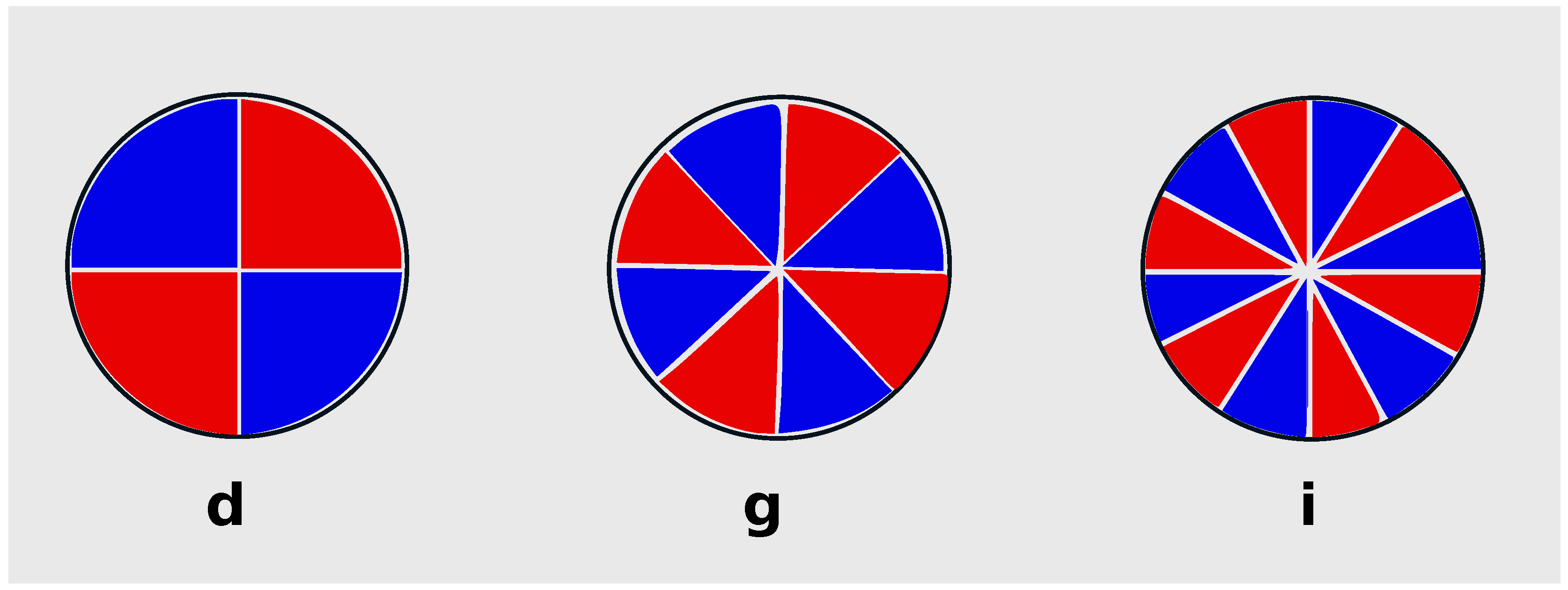

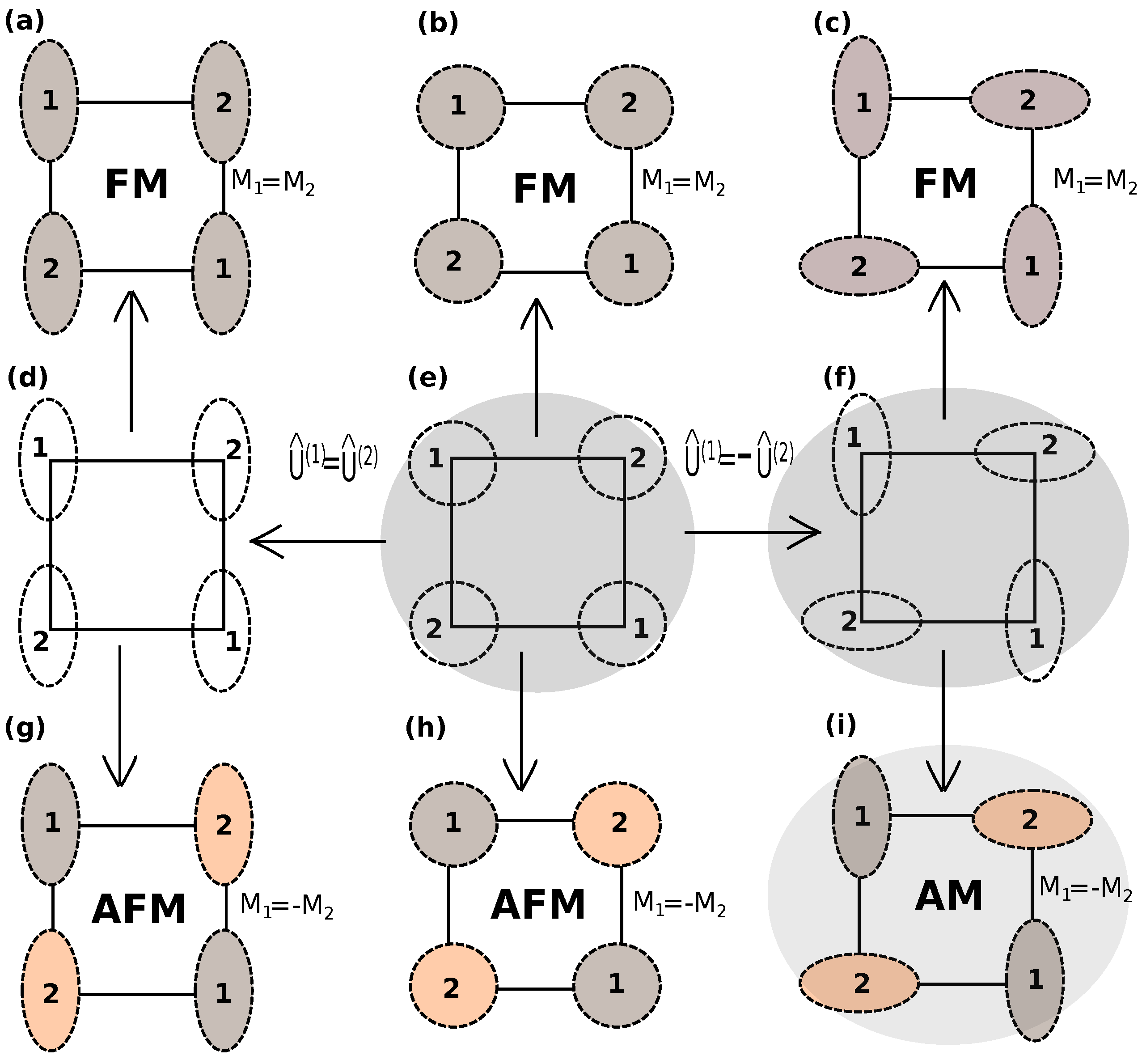

1. Introduction

- The number of magnetic atoms in a unit cell is even.

- The magnetic atoms in AMs are not related by inversion symmetry.

- Non-interconvertible local motif-pair spin anisotropy.

- The opposite-spin sublattices are connected by rotation (in spin and real spaces) or combined with translation or inversion symmetry, mirror, glide, or screw.

2. Spin Group Theory Description

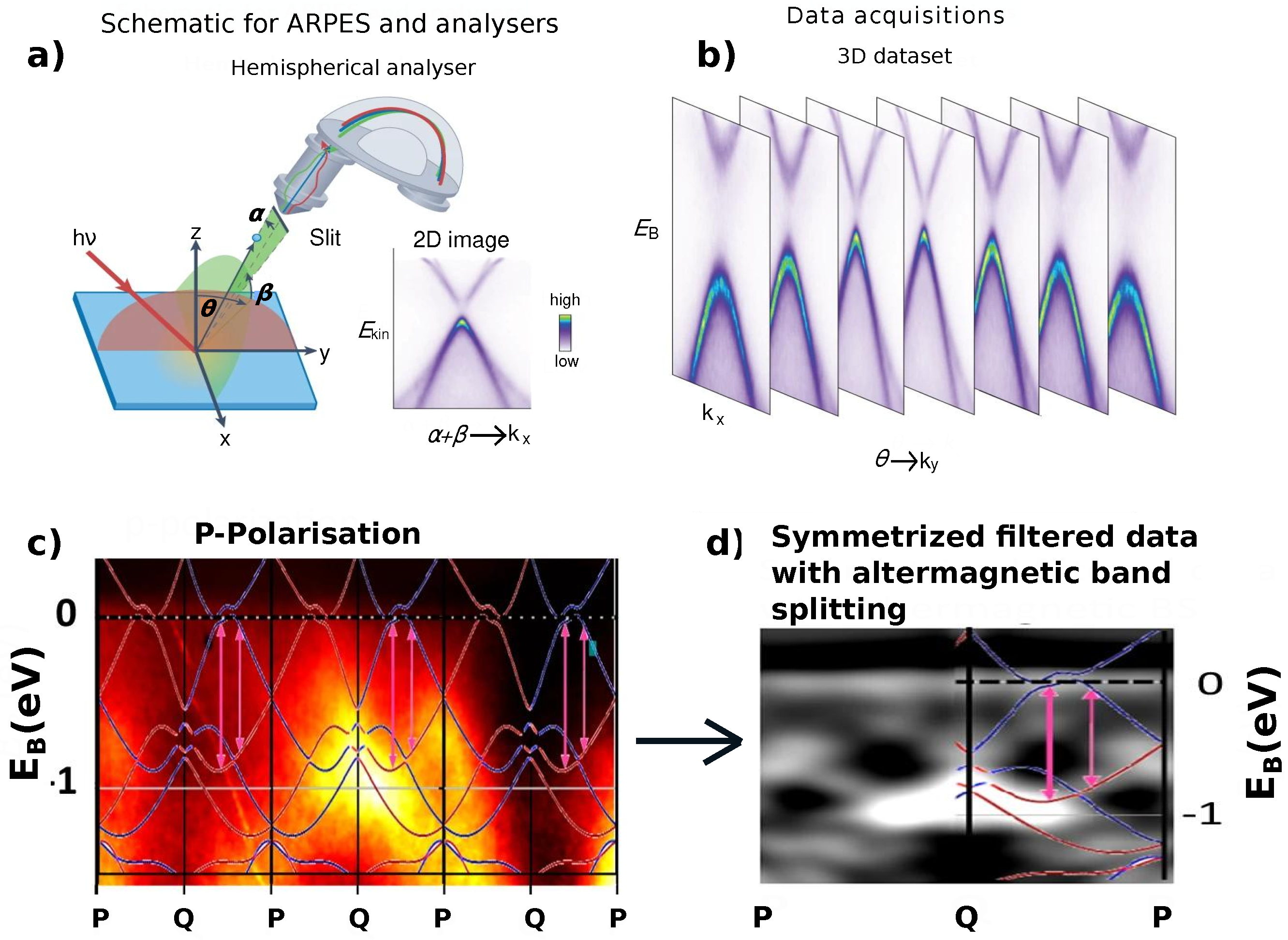

3. Experimental Techniques and Theoretical Approaches to Explore Altermagnetism

- High field torque magnetometry applied on FeSb2 to map the Fermi surface. [101].

- DFT (Density Functional Theory): First-principles investigations can be efficiently performed at a low computational cost without including SOC on altermagnets. First-principles calculations were performed to provide theoretical predictions to motivate and compare with experimental findings, focusing on various materials including RuO2 [98,108,109], CrSb [81,88], MnTe [72,94,96], MnF2 [110,111], and others [112].

4. Examples of Explored Altermagnetic Materials

4.1. MnF2 and Octupole Moments

4.2. Contradicting Reports on the Magnetic Ordering of RuO2

4.3. 2D AMs and Methods for Designing AMs

4.4. Perovskites

4.5. Superconductivity and Altermagnets

5. Emerging Magneto-Transport Phenomena and Promising Applications

5.1. Anomalous Hall Effect

5.2. Nernst Effects

5.3. Spintronics

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Baltz, V.; Manchon, A.; Tsoi, M.; Moriyama, T.; Ono, T.; Tserkovnyak, Y. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Reviews of Modern Physics 2018, 90, 015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili Amiri, P.; Phatak, C.; Finocchio, G. Prospects for Antiferromagnetic Spintronic Devices. Annual Review of Materials Research 2024, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungwirth, T.; Marti, X.; Wadley, P.; Wunderlich, J. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nature nanotechnology 2016, 11, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmejkal, L.; Sinova, J.; Jungwirth, T. Emerging research landscape of altermagnetism. Physical Review X 2022, 12, 040501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmejkal, L.; Sinova, J.; Jungwirth, T. Beyond conventional ferromagnetism and antiferromagnetism: A phase with nonrelativistic spin and crystal rotation symmetry. Physical Review X 2022, 12, 031042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazin, I.; Editors, P. Altermagnetism—a new punch line of fundamental magnetism, 2022.

- Néel, L. Some new results on antiferromagnetism and ferromagnetism. Reviews of Modern Physics 1953, 25, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashba, E.I. Spin-orbit coupling in condensed matter physics. Sov. Phys. Solid State 1960, 2, 1109. [Google Scholar]

- Dresselhaus, G. Spin-orbit coupling effects in zinc blende structures. Physical Review 1955, 100, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.D.; Wang, Z.; Luo, J.W.; Rashba, E.I.; Zunger, A. Giant momentum-dependent spin splitting in centrosymmetric low-Z antiferromagnets. Physical Review B 2020, 102, 014422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungwirth, T.; Fernandes, R.M.; Sinova, J.; Smejkal, L. Altermagnets and beyond: Nodal magnetically-ordered phases. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.10034 2024.

- Gomonay, O.; Kravchuk, V.; Jaeschke-Ubiergo, R.; Yershov, K.; Jungwirth, T.; Šmejkal, L.; Brink, J.v.d.; Sinova, J. Structure, control, and dynamics of altermagnetic textures. npj Spintronics 2024, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeranchuk, I.I.; et al. On the stability of a Fermi liquid. Sov. Phys. JETP 1958, 8, 361. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Sun, K.; Fradkin, E.; Zhang, S.C. Fermi liquid instabilities in the spin channel. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2007, 75, 115103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, S.W.; Huang, F.T. Altermagnetism with non-collinear spins. npj Quantum Materials 2024, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyanyuk, A.; Šmejkal, L.; Mazin, I.I. A tool to check whether a symmetry-compensated collinear magnetic material is antiferro-or altermagnetic. SciPost Physics Codebases 2024, p. 030.

- Bai, L.; Feng, W.; Liu, S.; Šmejkal, L.; Mokrousov, Y.; Yao, Y. Altermagnetism: Exploring new frontiers in magnetism and spintronics. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, p. 2409327.

- Gao, Z.F.; Qu, S.; Zeng, B.; Wen, J.R.; Sun, H.; Guo, P.; Lu, Z.Y. Ai-accelerated discovery of altermagnetic materials. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.04418 2023.

- Shao, D.F.; Zhang, S.H.; Li, M.; Eom, C.B.; Tsymbal, E.Y. Spin-neutral currents for spintronics. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hernández, R.; Šmejkal, L.; Vỳbornỳ, K.; Yahagi, Y.; Sinova, J.; Jungwirth, T.; Železnỳ, J. Efficient electrical spin splitter based on nonrelativistic collinear antiferromagnetism. Physical Review Letters 2021, 126, 127701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, A.; Schreiber, N.J.; Jain, R.; Shao, D.F.; Nair, H.P.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X.S.; Muller, D.A.; Tsymbal, E.Y.; Schlom, D.G.; et al. Tilted spin current generated by the collinear antiferromagnet ruthenium dioxide. Nature Electronics 2022, 5, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

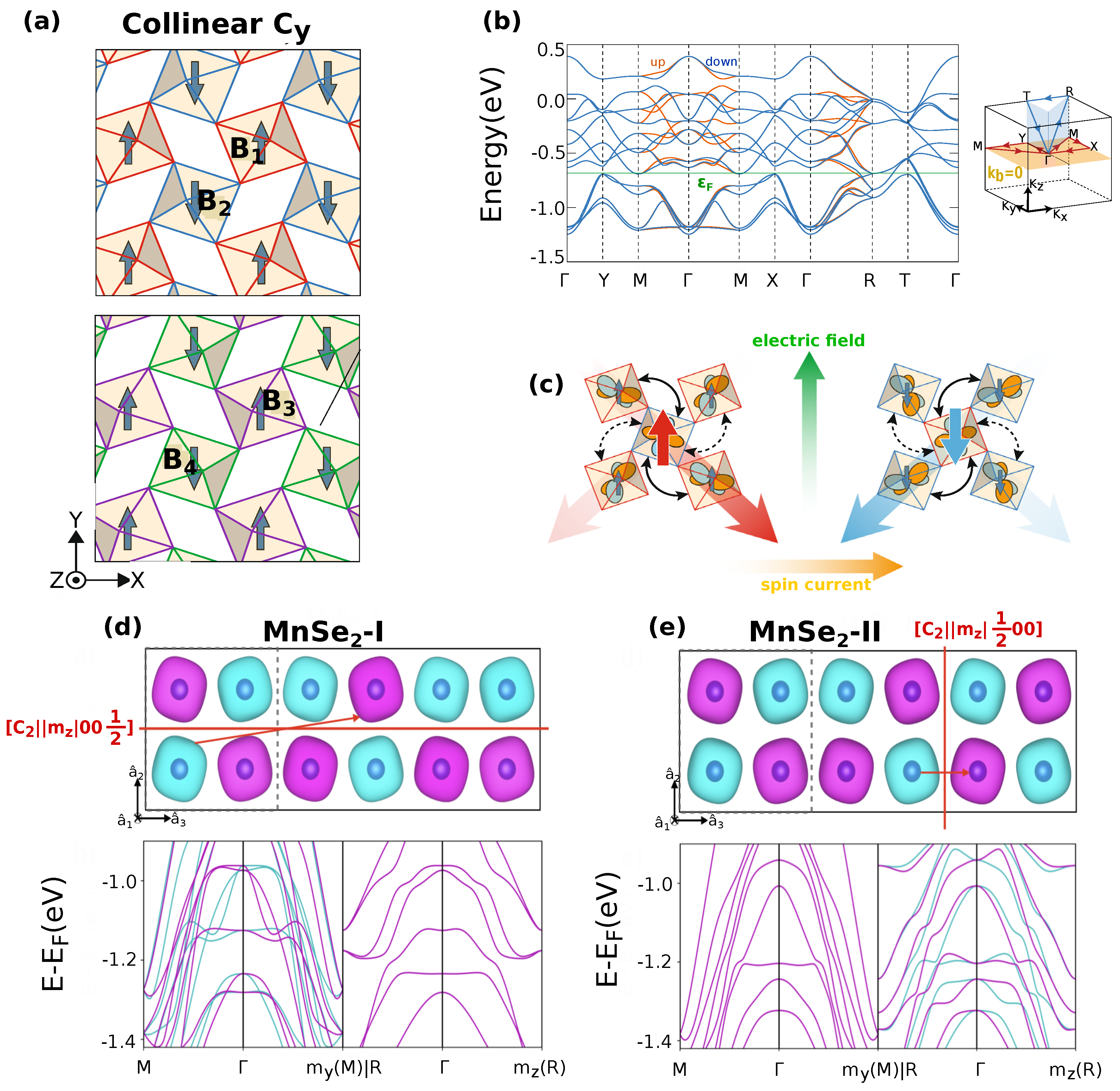

- Naka, M.; Motome, Y.; Seo, H. Perovskite as a spin current generator. Physical Review B 2021, 103, 125114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Han, L.; Feng, X.; Zhou, Y.; Su, R.; Wang, Q.; Liao, L.; Zhu, W.; Chen, X.; Pan, F.; et al. Observation of spin splitting torque in a collinear antiferromagnet RuO 2. Physical Review Letters 2022, 128, 197202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karube, S.; Tanaka, T.; Sugawara, D.; Kadoguchi, N.; Kohda, M.; Nitta, J. Observation of spin-splitter torque in collinear antiferromagnetic RuO 2. Physical review letters 2022, 129, 137201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, P.; Wan, C.; Han, L.; Zhu, W.; Liang, S.; Su, Y.; Han, X.; et al. Efficient spin-to-charge conversion via altermagnetic spin splitting effect in antiferromagnet RuO 2. Physical review letters 2023, 130, 216701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, H.; Han, L.; Chen, C.; Zhou, Y.; Back, C.H.; Pan, F.; Wang, Y.; Song, C. Simultaneous High Charge-Spin Conversion Efficiency and Large Spin Diffusion Length in Altermagnetic RuO2. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, 34, 2313332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

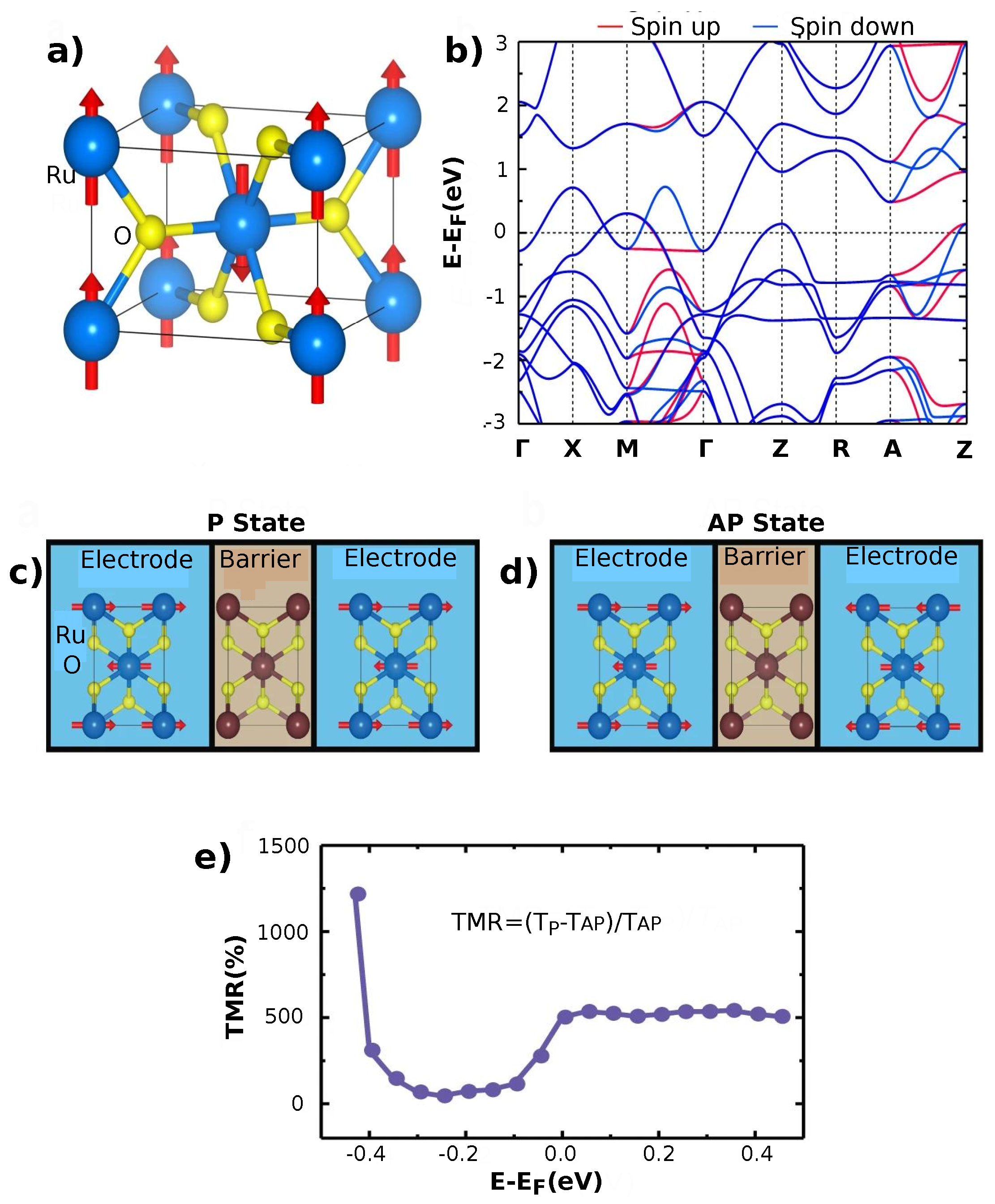

- Šmejkal, L.; Hellenes, A.B.; González-Hernández, R.; Sinova, J.; Jungwirth, T. Giant and tunneling magnetoresistance in unconventional collinear antiferromagnets with nonrelativistic spin-momentum coupling. Physical Review X 2022, 12, 011028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

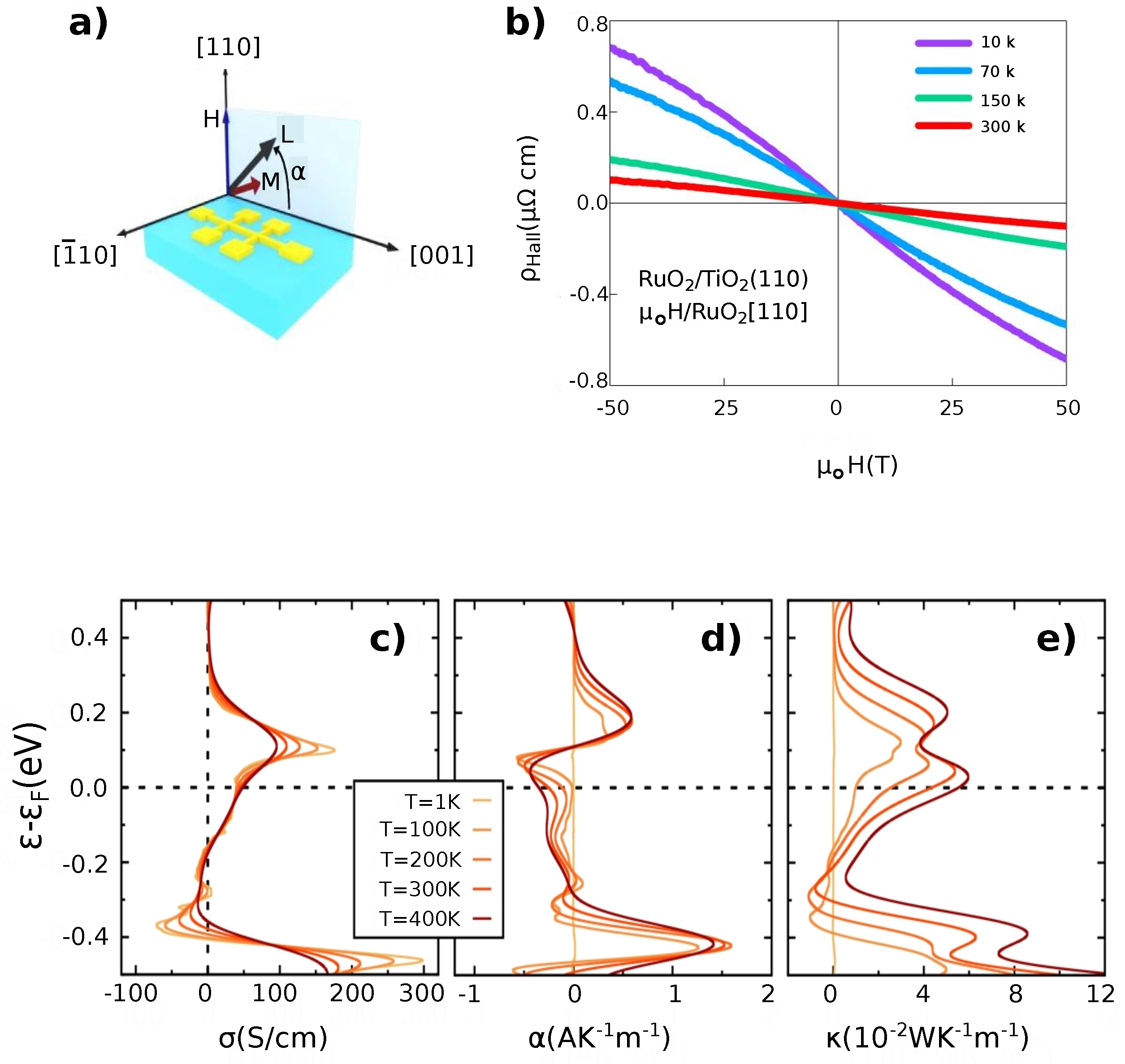

- Jiang, Y.Y.; Wang, Z.A.; Samanta, K.; Zhang, S.H.; Xiao, R.C.; Lu, W.; Sun, Y.; Tsymbal, E.Y.; Shao, D.F. Prediction of giant tunneling magnetoresistance in Ru O 2/Ti O 2/Ru O 2 (110) antiferromagnetic tunnel junctions. Physical Review B 2023, 108, 174439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, B.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Yu, G.; Wan, C.; Zhang, J.; Han, X. Crystal-facet-oriented altermagnets for detecting ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic states by giant tunneling magnetoresistance. Physical Review Applied 2024, 21, 034038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Suri, D.; Soori, A. Transport across junctions of altermagnets with normal metals and ferromagnets. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2023, 35, 435302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Betancourt, R.D.; Zubáč, J.; Geishendorf, K.; Ritzinger, P.; Růžičková, B.; Kotte, T.; Železnỳ, J.; Olejník, K.; Springholz, G.; Büchner, B.; et al. Anisotropic magnetoresistance in altermagnetic MnTe. npj Spintronics 2024, 2, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Lu, Z.; Xiong, R. Giant tunneling magnetoresistance in insulated altermagnet/ferromagnet junctions induced by spin-dependent tunneling effect. Physical Review B 2024, 110, 134437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouassou, J.A.; Brataas, A.; Linder, J. dc Josephson effect in altermagnets. Physical review letters 2023, 131, 076003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Zhuang, Z.Y.; Wu, Z.; Yan, Z. Topological superconductivity in two-dimensional altermagnetic metals. Physical Review B 2023, 108, 184505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.B.; Hu, L.H.; Neupert, T. Finite-momentum Cooper pairing in proximitized altermagnets. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Liu, C.C. Majorana corner modes and tunable patterns in an altermagnet heterostructure. Physical Review B 2023, 108, 205410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaj, M. Andreev reflection at the altermagnet-superconductor interface. Physical Review B 2023, 108, L060508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Scheurer, M.S. Altermagnetic superconducting diode effect. Physical Review B 2024, 110, 024503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Brataas, A.; Linder, J. Andreev reflection in altermagnets. Physical Review B 2023, 108, 054511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brekke, B.; Brataas, A.; Sudbø, A. Two-dimensional altermagnets: Superconductivity in a minimal microscopic model. Physical Review B 2023, 108, 224421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenakker, C.; Vakhtel, T. Phase-shifted Andreev levels in an altermagnet Josephson junction. Physical Review B 2023, 108, 075425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Black-Schaffer, A.M. Zero-field finite-momentum and field-induced superconductivity in altermagnets. Physical Review B 2024, 110, L060508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Sun, Q.F. Orientation-dependent Josephson effect in spin-singlet superconductor/altermagnet/spin-triplet superconductor junctions. Physical Review B 2024, 109, 024517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giil, H.G.; Linder, J. Superconductor-altermagnet memory functionality without stray fields. Physical Review B 2024, 109, 134511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyuzin, A.A. Magnetoelectric effect in superconductors with d-wave magnetization. Physical Review B 2024, 109, L220505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Maeda, K.; Ito, H.; Yada, K.; Tanaka, Y. φ Josephson junction induced by altermagnetism. Physical Review Letters 2024, 133, 226002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Xiang, L.; Xu, F.; Zhang, L.; Tang, G.; Wang, J. Gapless superconducting state and mirage gap in altermagnets. Physical Review B 2024, 109, L201404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, A.; Vadnais, S.; Paramekanti, A. Altermagnetism and superconductivity in a multiorbital t-J model. Physical Review B 2024, 110, 205120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mæland, K.; Brekke, B.; Sudbø, A. Many-body effects on superconductivity mediated by double-magnon processes in altermagnets. Physical Review B 2024, 109, 134515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumita, S.; Naka, M.; Seo, H. Fulde-Ferrell-Larkin-Ovchinnikov state induced by antiferromagnetic order in κ-type organic conductors. Physical Review Research 2023, 5, 043171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Mao, Y.; Sun, Q.F. Field-free Josephson diode effect in altermagnet/normal metal/altermagnet junctions. Physical Review B 2024, 110, 014518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Soori, A. Crossed Andreev reflection in altermagnets. Physical Review B 2024, 109, 245424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.X.; Matsyshyn, O.; Song, J.C. Nonlinear superconducting magnetoelectric effect. Physical Review Letters 2025, 134, 026001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhachov, P.O.; Hodt, E.W.; Linder, J. Thermoelectric effect in altermagnet-superconductor junctions. Physical Review B 2024, 110, 094508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X. Realizing tunable higher-order topological superconductors with altermagnets. Physical Review B 2024, 109, 224502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.P.; Zhang, Y.M. Electrically controlled crossed Andreev reflection in altermagnet/superconductor/altermagnet junctions. Superconductor Science and Technology 2024, 37, 055012. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Z.P.; Yang, Z. Orientation-dependent Andreev reflection in an altermagnet/altermagnet/superconductor junction. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 2024, 57, 395301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltz, V.; Hoffmann, A.; Emori, S.; Shao, D.F.; Jungwirth, T. Emerging materials in antiferromagnetic spintronics. APL Materials 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Seifert, T.S.; Huang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Kašpar, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wu, J.; Fan, K.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, D.; et al. Terahertz spin current dynamics in antiferromagnetic hematite. Advanced Science 2023, 10, 2300512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichlova, H.; Kriegner, D.; Mook, A.; Althammer, M.; Thomas, A. Role of topology in compensated magnetic systems. APL Materials 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.C. Creation and manipulation of higher-order topological states by altermagnets. Physical Review B 2024, 109, L201109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorashi, S.A.A.; Hughes, T.L.; Cano, J. Altermagnetic routes to Majorana modes in zero net magnetization. Physical review letters 2024, 133, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhou, X.; Qin, P.; Liu, Z. Review on spin-split antiferromagnetic spintronics. Applied Physics Letters 2024, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Klein, J.O.; Chappert, C.; Ravelosona, D.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W. Spintronics: Emerging ultra-low-power circuits and systems beyond MOS technology. ACM Journal on Emerging Technologies in Computing Systems (JETC) 2015, 12, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.K. Spintronics: A contemporary review of emerging electronics devices. Engineering science and technology, an international journal 2016, 19, 1503–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClarty, P.A.; Rau, J.G. Landau theory of altermagnetism. Physical Review Letters 2024, 132, 176702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, D.B. Spin point groups. Acta Crystallographica Section A: Crystal Physics, Diffraction, Theoretical and General Crystallography 1977, 33, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, D.B.; Opechowski, W. Spin groups. Physica 1974, 76, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, H. Ueber sehr schnelle electrische Schwingungen. Annalen der Physik 1887, 267, 421–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Über einen die Erzeugung und Verwandlung des Lichtes betreffenden heuristischen Gesichtspunkt, 1905.

- Zhang, H.; Pincelli, T.; Jozwiak, C.; Kondo, T.; Ernstorfer, R.; Sato, T.; Zhou, S. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2022, 2, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Jung, S.; Jung, J.; Kim, D.; Lee, Y.; Seok, B.; Kim, J.; Park, B.G.; Šmejkal, L.; et al. Broken kramers degeneracy in altermagnetic mnte. Physical Review Letters 2024, 132, 036702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, Y.; Kimura, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Nakatani, T.; Matsushita, T.; Muro, T.; Miyahara, T.; Fujisawa, M.; Soda, K.; Ueda, S.; et al. Performance of a very high resolution soft x-ray beamline BL25SU with a twin-helical undulator at SPring-8. Review of Scientific Instruments 2000, 71, 3254–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisenko, S.V. “One-cubed” ARPES user facility at BESSY II. Synchrotron Radiation News 2012, 25, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reininger, R.; Hulbert, S.; Johnson, P.; Sadowski, J.; Starr, D.; Chubar, O.; Valla, T.; Vescovo, E. The electron spectro-microscopy beamline at National Synchrotron Light Source II: A wide photon energy range, micro-focusing beamline for photoelectron spectro-microscopies. Review of Scientific Instruments 2012, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, L.; Hussain, Z.; Padmore, H.; Robin, D.; Bailey, S.; Feinberg, B.; Falcone, R. Advanced light source update. Synchrotron Radiation News 2012, 25, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strocov, V.; Wang, X.; Shi, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Krempasky, J.; Hess, C.; Schmitt, T.; Patthey, L. Soft-X-ray ARPES facility at the ADRESS beamline of the SLS: concepts, technical realisation and scientific applications. Synchrotron Radiation 2014, 21, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoesch, M.; Kim, T.; Dudin, P.; Wang, H.; Scott, S.; Harris, P.; Patel, S.; Matthews, M.; Hawkins, D.; Alcock, S.; et al. A facility for the analysis of the electronic structures of solids and their surfaces by synchrotron radiation photoelectron spectroscopy. Review of Scientific Instruments 2017, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiyama, A.; Iwasaki, T.; Matsuda, K.; Saitoh, Y.; Onuki, Y.; Suga, S. Probing bulk states of correlated electron systems by high-resolution resonance photoemission. Nature 2000, 403, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadley, C.S. Looking deeper: angle-resolved photoemission with soft and hard X-rays. Synchrotron Radiation News 2012, 25, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, X.; Tao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, T.; Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Cheng, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Large Band Splitting in g-Wave Altermagnet CrSb. Physical Review Letters 2024, 133, 206401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S. An experimentalist’s guide to the matrix element in angle resolved photoemission. Journal of Electron Spectroscopy and Related Phenomena 2017, 214, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtomo, A.; Hwang, H. A high-mobility electron gas at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterointerface. Nature 2004, 427, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyren, N.; Thiel, S.; Caviglia, A.; Kourkoutis, L.F.; Hammerl, G.; Richter, C.; Schneider, C.W.; Kopp, T.; Ruetschi, A.S.; Jaccard, D.; et al. Superconducting interfaces between insulating oxides. Science 2007, 317, 1196–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Bai, H.; Zhou, Z.; Han, L.; Reichlova, H.; Dil, J.H.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Pan, F. Altermagnets as a new class of functional materials. Nature Reviews Materials 2025, pp. 1–13.

- Nemšák, S.; Conti, G.; Gray, A.; Palsson, G.; Conlon, C.; Eiteneer, D.; Keqi, A.; Rattanachata, A.; Saw, A.; Bostwick, A.; et al. Energetic, spatial, and momentum character of the electronic structure at a buried interface: The two-dimensional electron gas between two metal oxides. Physical Review B 2016, 93, 245103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, G.; Sing, M.; Pfaff, F.; Benckiser, E.; Wu, M.; Christiani, G.; Logvenov, G.; Habermeier, H.U.; Kobayashi, M.; Strocov, V.; et al. Dimensionality-tuned electronic structure of nickelate superlattices explored by soft-x-ray angle-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy. Physical Review B 2015, 92, 125130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, S.; Odenbreit, L.; Šmejkal, L.; Strocov, V.N.; Constantinou, P.; Hellenes, A.B.; Jaeschke Ubiergo, R.; Campos, W.H.; Bharadwaj, V.K.; Chakraborty, A.; et al. Direct observation of altermagnetic band splitting in CrSb thin films. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Li, Z.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, W.; Pan, Z.; Xu, Y.; Cao, S.; Zhao, W.; et al. Three-dimensional mapping of the altermagnetic spin splitting in CrSb. Nature Communications 2025, 16, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Zhu, M.Y.; Zhu, Y.P.; Liu, X.R.; Ma, X.M.; Hao, Y.J.; Liu, P.; Qu, G.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Observation of Spin Splitting in Room-Temperature Metallic Antiferromagnet CrSb. Advanced Science 2024, p. 2406529.

- Jozwiak, C.; Graf, J.; Lebedev, G.; Andresen, N.; Schmid, A.; Fedorov, A.; El Gabaly, F.; Wan, W.; Lanzara, A.; Hussain, Z. A high-efficiency spin-resolved photoemission spectrometer combining time-of-flight spectroscopy with exchange-scattering polarimetry. Review of Scientific Instruments 2010, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, T. Recent trends in spin-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2017, 29, 483001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Moreschini, L.; Lanzara, A. Present and future trends in spin ARPES. Europhysics Letters 2021, 134, 57001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krempaskỳ, J.; Šmejkal, L.; D’souza, S.; Hajlaoui, M.; Springholz, G.; Uhlířová, K.; Alarab, F.; Constantinou, P.; Strocov, V.; Usanov, D.; et al. Altermagnetic lifting of Kramers spin degeneracy. Nature 2024, 626, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhan, J.; Li, T.; Liu, J.; Cheng, S.; Shi, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Ding, J.; et al. Absence of Altermagnetic Spin Splitting Character in Rutile Oxide RuO 2. Physical Review Letters 2024, 133, 176401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osumi, T.; Souma, S.; Aoyama, T.; Yamauchi, K.; Honma, A.; Nakayama, K.; Takahashi, T.; Ohgushi, K.; Sato, T. Observation of a giant band splitting in altermagnetic MnTe. Physical Review B 2024, 109, 115102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.P.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, P.; Zha, H.; Qu, G.; Hong, C.; Li, J.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Observation of plaid-like spin splitting in a noncoplanar antiferromagnet. Nature 2024, 626, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chen, D.; Lu, W.; Liang, X.; Feng, S.; Yamagami, K.; Osiecki, J.; Leandersson, M.; Thiagarajan, B.; Liu, J.; et al. Observation of giant spin splitting and d-wave spin texture in room temperature altermagnet ruo2. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.04995 2024.

- Zhang, F.; Cheng, X.; Yin, Z.; Liu, C.; Deng, L.; Qiao, Y.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, S.; Lin, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. Crystal-symmetry-paired spin-valley locking in a layered room-temperature antiferromagnet. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.19555 2024.

- Jiang, B.; Hu, M.; Bai, J.; Song, Z.; Mu, C.; Qu, G.; Li, W.; Zhu, W.; Pi, H.; Wei, Z.; et al. A metallic room-temperature d-wave altermagnet. Nature Physics 2025, pp. 1–6.

- Phillips, C.; Pokharel, G.; Shtefiienko, K.; Bhandari, S.R.; Graf, D.E.; Rai, D.; Shrestha, K. Electronic structure of the altermagnet candidate FeSb 2: High-field torque magnetometry and density functional theory studies. Physical Review B 2025, 111, 075141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keßler, P.; Garcia-Gassull, L.; Suter, A.; Prokscha, T.; Salman, Z.; Khalyavin, D.; Manuel, P.; Orlandi, F.; Mazin, I.I.; Valentí, R.; et al. Absence of magnetic order in RuO2: insights from μ SR spectroscopy and neutron diffraction. npj Spintronics 2024, 2, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovesey, S.; Khalyavin, D.; Van Der Laan, G. Templates for magnetic symmetry and altermagnetism in hexagonal MnTe. Physical Review B 2023, 108, 174437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariki, A.; Okauchi, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Kuneš, J. Determination of the Néel vector in rutile altermagnets through x-ray magnetic circular dichroism: The case of MnF 2. Physical Review B 2024, 110, L100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariki, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Kuneš, J. X-ray magnetic circular dichroism in RuO 2. Physical Review B 2024, 109, 094413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, O.; Dal Din, A.; Golias, E.; Niu, Y.; Zakharov, A.; Fromage, S.; Fields, C.; Heywood, S.; Cousins, R.; Maccherozzi, F.; et al. Nanoscale imaging and control of altermagnetism in MnTe. Nature 2024, 636, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariki, A.; Dal Din, A.; Amin, O.; Yamaguchi, T.; Badura, A.; Kriegner, D.; Edmonds, K.; Campion, R.; Wadley, P.; Backes, D.; et al. X-ray magnetic circular dichroism in altermagnetic α-MnTe. Physical Review Letters 2024, 132, 176701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmejkal, L.; González-Hernández, R.; Jungwirth, T.; Sinova, J. Crystal time-reversal symmetry breaking and spontaneous Hall effect in collinear antiferromagnets. Science advances 2020, 6, eaaz8809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, K.H.; Hariki, A.; Lee, K.W.; Kuneš, J. Antiferromagnetism in RuO 2 as d-wave Pomeranchuk instability. Physical Review B 2019, 99, 184432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowal, S.; Spaldin, N.A. Ferroically Ordered Magnetic Octupoles in d-Wave Altermagnets. Phys. Rev. X 2024, 14, 011019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.D.; Wang, Z.; Luo, J.W.; Zunger, A. Prediction of low-Z collinear and noncollinear antiferromagnetic compounds having momentum-dependent spin splitting even without spin-orbit coupling. Physical Review Materials 2021, 5, 014409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, H.; Janson, O.; Fulga, I.C.; van den Brink, J.; Facio, J.I. Spin-split collinear antiferromagnets: A large-scale ab-initio study. Materials Today Physics 2023, 32, 100991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, J.; Das, B.; Bhowal, S.; Nishioka, Y.; Bandyopadhyay, B.; Sarker, S.; Kumar, S.; Kuroda, K.; Gopalan, V.; Kimura, A.; et al. GdAlSi: An antiferromagnetic topological Weyl semimetal with nonrelativistic spin splitting. Physical Review B 2024, 110, 224436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedchenko, O.; Minár, J.; Akashdeep, A.; D’Souza, S.W.; Vasilyev, D.; Tkach, O.; Odenbreit, L.; Nguyen, Q.; Kutnyakhov, D.; Wind, N.; et al. Observation of time-reversal symmetry breaking in the band structure of altermagnetic RuO2. Science advances 2024, 10, eadj4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, N.; Ashour, O.A.; Vila, M.; Regmi, R.B.; Fox, J.; Johnson, C.W.; Fedorov, A.; Stibor, A.; Ghimire, N.J.; Griffin, S.M. Non-relativistic spin splitting above and below the Fermi level in a g-wave altermagnet. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.18761 2024.

- Sakhya, A.P.; Mondal, M.I.; Sprague, M.; Regmi, R.B.; Kumay, A.K.; Sheokand, H.; Mazin, I.; Ghimire, N.J.; Neupane, M.; et al. Electronic structure of a layered altermagnetic compound CoNb4Se8. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.16670 2025.

- De Vita, A.; Bigi, C.; Romanin, D.; Watson, M.D.; Polewczyk, V.; Zonno, M.; Bertran, F.; Petersen, M.B.; Motti, F.; Vinai, G.; et al. Optical switching in a layered altermagnet. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.20010 2025.

- Candelora, C.; Xu, M.; Cheng, S.; De Vita, A.; Romanin, D.; Bigi, C.; Petersen, M.B.; LaFleur, A.; Calandra, M.; Miwa, J.; et al. Discovery of intertwined spin and charge density waves in a layered altermagnet. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.03716 2025.

- Ryden, W.; Lawson, A. Magnetic susceptibility of IrO2 and RuO2. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1970, 52, 6058–6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlijn, T.; Snijders, P.C.; Delaire, O.; Zhou, H.D.; Maier, T.A.; Cao, H.B.; Chi, S.X.; Matsuda, M.; Wang, Y.; Koehler, M.R.; et al. Itinerant antiferromagnetism in RuO 2. Physical review letters 2017, 118, 077201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Strempfer, J.; Rao, R.; Occhialini, C.; Pelliciari, J.; Choi, Y.; Kawaguchi, T.; You, H.; Mitchell, J.; Shao-Horn, Y.; et al. Anomalous antiferromagnetism in metallic RuO 2 determined by resonant X-ray scattering. Physical review letters 2019, 122, 017202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyanyuk, A.; Mazin, I.I.; Garcia-Gassull, L.; Valentí, R. Fragility of the magnetic order in the prototypical altermagnet RuO 2. Physical Review B 2024, 109, 134424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahimi, S.; Rai, D.P.; Lounis, S. Confinement-induced altermangetism in RuO2 ultrathin films. ArXiv: 2024, 2412.15377.

- Jeong, S.G.; Choi, I.H.; Nair, S.; Buiarelli, L.; Pourbahari, B.; Oh, J.Y.; Bassim, N.; Seo, A.; Choi, W.S.; Fernandes, R.M.; et al. Altermagnetic polar metallic phase in ultra-thin epitaxially-strained RuO2 films. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.05838 2024.

- Weber, M.; Wust, S.; Haag, L.; Akashdeep, A.; Leckron, K.; Schmitt, C.; Ramos, R.; Kikkawa, T.; Saitoh, E.; Kläui, M.; et al. All optical excitation of spin polarization in d-wave altermagnets. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.05187 2024.

- Reichlova, H.; Lopes Seeger, R.; González-Hernández, R.; Kounta, I.; Schlitz, R.; Kriegner, D.; Ritzinger, P.; Lammel, M.; Leiviskä, M.; Birk Hellenes, A.; et al. Observation of a spontaneous anomalous Hall response in the Mn5Si3 d-wave altermagnet candidate. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Fu, X.; Peng, R.; Cheng, X.; Dai, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Bai, H.; et al. Electrical 180 switching of Néel vector in spin-splitting antiferromagnet. Science Advances 2024, 10, eadn0479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraishi, M.; Okabe, H.; Koda, A.; Kadono, R.; Muroi, T.; Hirai, D.; Hiroi, Z. Nonmagnetic Ground State in RuO 2 Revealed by Muon Spin Rotation. Physical Review Letters 2024, 132, 166702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmejkal, L.; Marmodoro, A.; Ahn, K.H.; González-Hernández, R.; Turek, I.; Mankovsky, S.; Ebert, H.; D’Souza, S.W.; Šipr, O.; Sinova, J.; et al. Chiral magnons in altermagnetic RuO 2. Physical Review Letters 2023, 131, 256703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohlke, M.; Corticelli, A.; Moessner, R.; McClarty, P.A.; Mook, A. Spurious symmetry enhancement in linear spin wave theory and interaction-induced topology in magnons. Physical Review Letters 2023, 131, 186702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Jin, T.; Sbiaa, R.; Kläui, M.; Bedanta, S.; Fukami, S.; Ravelosona, D.; Yang, S.H.; Liu, X.; Piramanayagam, S. Domain wall memory: Physics, materials, and devices. Physics Reports 2022, 958, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

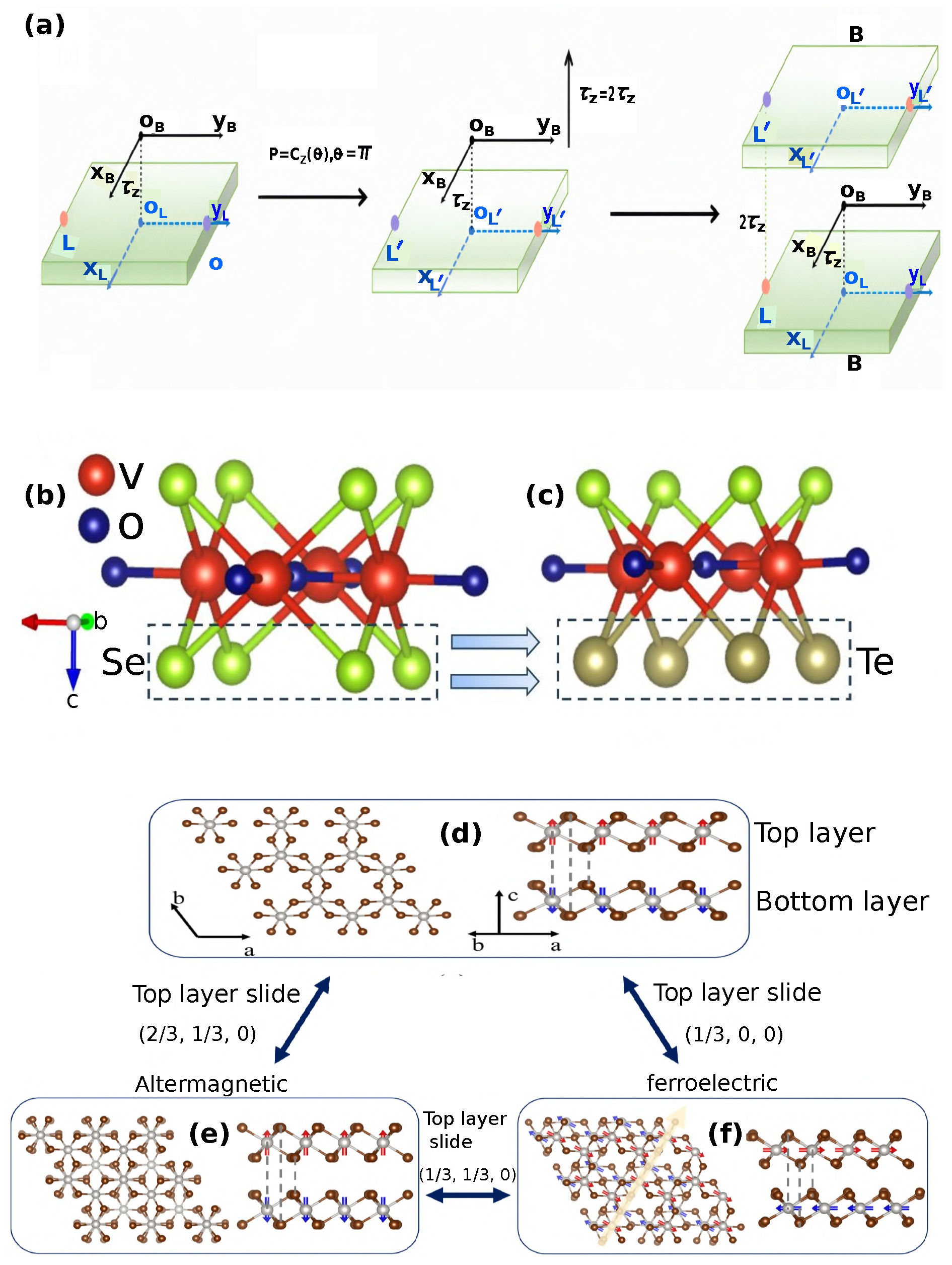

- Pan, B.; Zhou, P.; Lyu, P.; Xiao, H.; Yang, X.; Sun, L. General Stacking Theory for Altermagnetism in Bilayer Systems. Physical Review Letters 2024, 133, 166701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, T.; Li, Y.; Qiao, L.; Ma, X.; Liu, C.; Hu, T.; Gao, H.; Ren, W. Multipiezo effect in altermagnetic V2SeTeO monolayer. Nano Letters 2023, 24, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Ye, H.; Liang, L.; Ding, N.; Dong, S.; Wang, S.S. Stacking-dependent ferroicity of a reversed bilayer: Altermagnetism or ferroelectricity. Physical Review B 2024, 110, 224418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Kang, J.; Wang, P.; Gao, W.; Qi, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, X. Inverse Magnetocaloric Effect in Altermagnetic 2D Non-van der Waals FeX (X= S and Se) Semiconductors. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, p. 2402080.

- Milivojević, M.; Orozović, M.; Picozzi, S.; Gmitra, M.; Stavrić, S. Interplay of altermagnetism and weak ferromagnetism in two-dimensional RuF4. 2D Materials 2024, 11, 035025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitrienko, V.; Ovchinnikova, E.; Collins, S.; Nisbet, G.; Beutier, G.; Kvashnin, Y.; Mazurenko, V.; Lichtenstein, A.; Katsnelson, M. Measuring the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction in a weak ferromagnet. Nature Physics 2014, 10, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Wang, D.; Luo, N.; Zeng, J.; Chen, K.Q.; Tang, L.M. Nonrelativistic spin-momentum coupling in antiferromagnetic twisted bilayers. Physical Review Letters 2023, 130, 046401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, C.C. Twisted magnetic van der Waals bilayers: an ideal platform for altermagnetism. Physical Review Letters 2024, 133, 206702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, N.; Xu, B.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, J.; Sun, Z. 2D intrinsic ferromagnets from van der Waals antiferromagnets. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2018, 140, 2417–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Peng, R.; Dai, Y.; Huang, B.; Duan, L.; Ma, Y. Antiferromagnetic ferroelastic multiferroics in single-layer VOX (X= Cl, Br) predicted from first-principles. Applied Physics Letters 2021, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.X.; Su, C.; He, L. High-throughput computation and structure prototype analysis for two-dimensional ferromagnetic materials. npj Computational Materials 2022, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, R.; Luo, N.; Zou, X. Two-dimensional magnetic materials: structures, properties and external controls. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 1398–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, D.; Moustafa, H.; Jacobsen, K.W.; Olsen, T. High-throughput computational screening for two-dimensional magnetic materials based on experimental databases of three-dimensional compounds. npj Computational Materials 2020, 6, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Bezzerga, D.; Marfoua, B.; Hong, J. Altermagnetism, piezovalley, and ferroelectricity in two-dimensional Cr2SeO altermagnet. npj 2D Materials and Applications 2025, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.D.; Guo, X.S.; Cheng, K.; Wang, K.; Ang, Y.S. Piezoelectric altermagnetism and spin-valley polarization in Janus monolayer Cr2SO. Applied Physics Letters 2023, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Su, X.; Chen, J.; Jin, C.; Chen, L. Two-Dimensional Metal-Organic Frameworks Towards Spintronics. Angewandte Chemie 2023, 135, e202305408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Y.; Lv, H.; Wu, X.; Yang, J. Realizing altermagnetism in two-dimensional metal–organic framework semiconductors with electric-field-controlled anisotropic spin current. Chemical Science 2024, 15, 13853–13863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cabrelles, J.; Mañas-Valero, S.; Vitórica-Yrezábal, I.J.; Šiškins, M.; Lee, M.; Steeneken, P.G.; Van Der Zant, H.S.; Minguez Espallargas, G.; Coronado, E. Chemical design and magnetic ordering in thin layers of 2D metal–organic frameworks (MOFs). Journal of the American Chemical Society 2021, 143, 18502–18510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; González Hernández, R.; Šmejkal, L.; Sinova, J. Strain-induced phase transition from antiferromagnet to altermagnet. Physical Review B 2024, 109, 144421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Gong, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, B. High-pressure modulation of altermagnetism in MnF2. Applied Physics Letters 2025, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeb, V.; Mook, A.; Šmejkal, L.; Knolle, J. Spontaneous Formation of Altermagnetism from Orbital Ordering. Physical Review Letters 2024, 132, 236701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Lee, C.C.; Chang, T.R.; Jeng, H.T.; Lin, H.; Haga, Y.; Fisk, Z.; Hasegawa, Y. Atomic-scale visualization of surface-assisted orbital order. Science advances 2017, 3, eaao0362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Hill, J.; Gibbs, D.; Blume, M.; Koyama, I.; Tanaka, M.; Kawata, H.; Arima, T.; Tokura, Y.; Hirota, K.; et al. Resonant x-ray scattering from orbital ordering in LaMnO 3. Physical review letters 1998, 81, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Kawada, H.; Kawata, H.; Tanaka, M.; Arima, T.; Moritomo, Y.; Tokura, Y. Direct observation of charge and orbital ordering in La 0.5 Sr 1.5 MnO 4. Physical review letters 1998, 80, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizokawa, T.; Khomskii, D.; Sawatzky, G. Interplay between orbital ordering and lattice distortions in LaMnO 3, YVO 3, and YTiO 3. Physical Review B 1999, 60, 7309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliullin, G.; Horsch, P.; Oleś, A.M. Spin order due to orbital fluctuations: Cubic vanadates. Physical review letters 2001, 86, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeschke-Ubiergo, R.; Bharadwaj, V.K.; Jungwirth, T.; Šmejkal, L.; Sinova, J. Supercell altermagnets. Physical Review B 2024, 109, 094425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mei, L.; Wang, K.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lian, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, Z.; Xiao, G.; Liu, Q.; et al. Advances in the application of perovskite materials. Nano-Micro Letters 2023, 15, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.S.; Naidu, K.C.B. A review on perovskite solar cells (PSCs), materials and applications. Journal of Materiomics 2021, 7, 940–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bati, A.S.; Zhong, Y.L.; Burn, P.L.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Shaw, P.E.; Batmunkh, M. Next-generation applications for integrated perovskite solar cells. Communications Materials 2023, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanga, L.; Lalengmawia, C.; Renthlei, Z.; Chanu, S.T.; Hima, L.; Singh, N.S.; Yvaz, A.; Bhattarai, S.; Rai, D. A review on perovskite materials for photovoltaic applications. Next Materials 2025, 7, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naka, M.; Motome, Y.; Seo, H. Altermagnetic perovskites. npj Spintronics 2025, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naka, M.; Motome, Y.; Seo, H. Anomalous Hall effect in antiferromagnetic perovskites. Physical Review B 2022, 106, 195149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardini, F.; Fiebig, M.; Cano, A. Ruddlesden-Popper and perovskite phases as a material platform for altermagnetism. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.12910 2024.

- Komarek, A.; Streltsov, S.; Isobe, M.; Möller, T.; Hoelzel, M.; Senyshyn, A.; Trots, D.; Fernández-Díaz, M.; Hansen, T.; Gotou, H.; et al. CaCrO 3: an anomalous antiferromagnetic metallic oxide. Physical Review Letters 2008, 101, 167204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordet, P.; Chaillout, C.; Marezio, M.; Huang, Q.; Santoro, A.; Cheong, S.; Takagi, H.; Oglesby, C.; Batlogg, B. Structural aspects of the crystallographic-magnetic transition in LaVO3 around 140 K. Journal of Solid State Chemistry 1993, 106, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka, S.; Okimoto, Y.; Iwama, M.; Tokura, Y. Spin-orbital phase diagram of perovskite-type R VO 3 (R= rare-earth ion or Y). Physical Review B 2003, 68, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka, S.; Okuda, T.; Tokura, Y. Critical behavior of metal-insulator transition in La 1- x Sr x VO 3. Physical Review Letters 2000, 85, 5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyev, I. Magneto-optical effect in the weak ferromagnets LaMO 3 (M= Cr, Mn, and Fe). Physical Review B 1997, 55, 8060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajimoto, R.; Yoshizawa, H.; Tomioka, Y.; Tokura, Y. Stripe-type charge ordering in the metallic A-type antiferromagnet Pr 0.5 Sr 0.5 MnO 3. Physical Review B 2002, 66, 180402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okugawa, T.; Ohno, K.; Noda, Y.; Nakamura, S. Weakly spin-dependent band structures of antiferromagnetic perovskite LaMO3 (M= Cr, Mn, Fe). Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2018, 30, 075502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.S.; Alonso, J.; Muonz, A.; Fernández-Díaz, M.; Goodenough, J. Magnetic structure of LaCrO 3 perovskite under high pressure from in situ neutron diffraction. Physical Review Letters 2011, 106, 057201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jüdin, V.; Sherman, A. Weak ferromagnetism of YCrO3. Solid State Communications 1966, 4, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, B.; Surendra, M.K.; Rao, M.R. HoCrO3 and YCrO3: a comparative study. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2013, 25, 216004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skumryev, V.; Ott, F.; Coey, J.; Anane, A.; Renard, J.P.; Pinsard-Gaudart, L.; Revcolevschi, A. Weak ferromagnetism in LaMnO 3. The European Physical Journal B-Condensed Matter and Complex Systems 1999, 11, 401–406. [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet, E.; Cano, A. Non-collinear magnetism in multiferroic perovskites. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2016, 28, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. Review of recent work on the magnetic and spectroscopic properties of the rare-earth orthoferrites. Journal of Applied Physics 1969, 40, 1061–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, C.A.; Kavanagh, C.M.; Knight, K.S.; Kockelmann, W.; Morrison, F.D.; Lightfoot, P. Thermal evolution of the crystal structure of the orthorhombic perovskite LaFeO3. Journal of Solid State Chemistry 2015, 230, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, P.; Kollipara, V.S. Evaluating the structure-property correlation in Y1-xNdxFeO3 (0≤ x≤ 0.15) perovskites. Ceramics International 2021, 47, 30797–30806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, J.; Lyons, D.; Kestigian, M. Antiferromagnetic resonance in NaMnF3. Journal of Applied Physics 1967, 38, 1280–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, O.; Knox, K. Magnetic Properties of KMn F 3. I. Crystallographic Studies. Physical Review 1961, 121, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeger, A.; Beckman, O.; Portis, A. Magnetic Properties of KMn F 3. II. Weak Ferromagnetism. Physical Review 1961, 123, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattigeri, R.M.; Cuono, G.; Autieri, C. Altermagnetic surface states: towards the observation and utilization of altermagnetism in thin films, interfaces and topological materials. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 16998–17005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhou, X.; Šmejkal, L.; Wu, L.; Zhu, Z.; Guo, H.; González-Hernández, R.; Wang, X.; Yan, H.; Qin, P.; et al. An anomalous Hall effect in altermagnetic ruthenium dioxide. Nature Electronics 2022, 5, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Feng, W.; Zhang, R.W.; Šmejkal, L.; Sinova, J.; Mokrousov, Y.; Yao, Y. Crystal thermal transport in altermagnetic RuO 2. Physical review letters 2024, 132, 056701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazin, I.I. Notes on altermagnetism and superconductivity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.05000 2022.

- Nagaosa, N.; Sinova, J.; Onoda, S.; MacDonald, A.H.; Ong, N.P. Anomalous hall effect. Reviews of modern physics 2010, 82, 1539–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Niu, Q.; MacDonald, A.H. Anomalous Hall effect arising from noncollinear antiferromagnetism. Physical review letters 2014, 112, 017205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kübler, J.; Felser, C. Non-collinear antiferromagnets and the anomalous Hall effect. Europhysics Letters 2014, 108, 67001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuji, S.; Kiyohara, N.; Higo, T. Large anomalous Hall effect in a non-collinear antiferromagnet at room temperature. Nature 2015, 527, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sürgers, C.; Kittler, W.; Wolf, T.; Löhneysen, H.v. Anomalous Hall effect in the noncollinear antiferromagnet Mn5Si3. AIP Advances 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrin, D.; Samathrakis, I.; Zemen, J.; Mihai, A.; Zou, B.; Johnson, F.; Esser, B.D.; McComb, D.W.; Petrov, P.K.; Zhang, H.; et al. Anomalous Hall effect in noncollinear antiferromagnetic Mn 3 NiN thin films. Physical Review Materials 2019, 3, 094409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmejkal, L.; MacDonald, A.H.; Sinova, J.; Nakatsuji, S.; Jungwirth, T. Anomalous hall antiferromagnets. Nature Reviews Materials 2022, 7, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, N.J.; Botana, A.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.S.; Mitchell, J. Large anomalous Hall effect in the chiral-lattice antiferromagnet CoNb3S6. Nature communications 2018, 9, 3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naka, M.; Hayami, S.; Kusunose, H.; Yanagi, Y.; Motome, Y.; Seo, H. Anomalous Hall effect in κ-type organic antiferromagnets. Physical Review B 2020, 102, 075112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attias, L.; Levchenko, A.; Khodas, M. Intrinsic anomalous Hall effect in altermagnets. Physical Review B 2024, 110, 094425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiviskä, M.; Rial, J.; Bad’ura, A.; Seeger, R.L.; Kounta, I.; Beckert, S.; Kriegner, D.; Joumard, I.; Schmoranzerová, E.; Sinova, J.; et al. Anisotropy of the anomalous Hall effect in thin films of the altermagnet candidate Mn 5 Si 3. Physical Review B 2024, 109, 224430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschirner, T.; Keßler, P.; Gonzalez Betancourt, R.D.; Kotte, T.; Kriegner, D.; Büchner, B.; Dufouleur, J.; Kamp, M.; Jovic, V.; Smejkal, L.; et al. Saturation of the anomalous Hall effect at high magnetic fields in altermagnetic RuO2. APL Materials 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Tan, Z.; Gong, Z.; Wang, J. Anomalous Hall effect in two-dimensional vanadium tetrahalogen with altermagnetic phase. Physical Review B 2024, 110, 155125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, R.G.; Zubáč, J.; Gonzalez-Hernandez, R.; Geishendorf, K.; Šobáň, Z.; Springholz, G.; Olejník, K.; Šmejkal, L.; Sinova, J.; Jungwirth, T.; et al. Spontaneous anomalous Hall effect arising from an unconventional compensated magnetic phase in a semiconductor. Physical Review Letters 2023, 130, 036702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.T.; Yamauchi, K. Ab initio prediction of anomalous Hall effect in antiferromagnetic CaCrO 3. Physical Review B 2023, 107, 155126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.Y.; Yang, H.C.; Liu, Z.X.; Guo, P.J.; Lu, Z.Y. Large intrinsic anomalous Hall effect in both Nb 2 FeB 2 and Ta 2 FeB 2 with collinear antiferromagnetism. Physical Review B 2023, 107, L161109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tanaka, K.; Sakai, S.; Wang, Z.; Deng, K.; Lyu, Y.; Li, C.; Tian, D.; Shen, S.; Ogawa, N.; et al. Emergent zero-field anomalous Hall effect in a reconstructed rutile antiferromagnetic metal. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 8240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichlová, H.; Seeger, R.L.; González-Hernández, R.; Kounta, I.; Schlitz, R.; Kriegner, D.; Ritzinger, P.; Lammel, M.; Leiviskä, M.; Petříček, V.; et al. Macroscopic time reversal symmetry breaking arising from antiferromagnetic Zeeman effect 2024.

- Kluczyk, K.; Gas, K.; Grzybowski, M.; Skupiński, P.; Borysiewicz, M.; Fąs, T.; Suffczyński, J.; Domagala, J.; Grasza, K.; Mycielski, A.; et al. Coexistence of anomalous Hall effect and weak magnetization in a nominally collinear antiferromagnet MnTe. Physical Review B 2024, 110, 155201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmejkal, L.; Mokrousov, Y.; Yan, B.; MacDonald, A.H. Topological antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nature physics 2018, 14, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.Z.; Chang, G.; Belopolski, I.; Bian, G.; Xu, S.Y.; Yin, J.X. Weyl, Dirac and high-fold chiral fermions in topological quantum matter. Nature Reviews Materials 2021, 6, 784–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradlyn, B.; Cano, J.; Wang, Z.; Vergniory, M.; Felser, C.; Cava, R.J.; Bernevig, B.A. Beyond Dirac and Weyl fermions: Unconventional quasiparticles in conventional crystals. Science 2016, 353, aaf5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, W. XIX. On the electro-dynamic qualities of metals:—Effects of magnetization on the electric conductivity of nickel and of iron. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 1857, pp. 546–550.

- Baibich, M.N.; Broto, J.M.; Fert, A.; Van Dau, F.N.; Petroff, F.; Etienne, P.; Creuzet, G.; Friederich, A.; Chazelas, J. Giant magnetoresistance of (001) Fe/(001) Cr magnetic superlattices. Physical review letters 1988, 61, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binasch, G.; Grünberg, P.; Saurenbach, F.; Zinn, W. Enhanced magnetoresistance in layered magnetic structures with antiferromagnetic interlayer exchange. Physical review B 1989, 39, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Tezuka, N. Giant magnetic tunneling effect in Fe/Al2O3/Fe junction. Journal of magnetism and magnetic materials 1995, 139, L231–L234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodera, J.S.; Kinder, L.R.; Wong, T.M.; Meservey, R. Large magnetoresistance at room temperature in ferromagnetic thin film tunnel junctions. Physical review letters 1995, 74, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slonczewski, J.C. Current-driven excitation of magnetic multilayers. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 1996, 159, L1–L7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, L. Emission of spin waves by a magnetic multilayer traversed by a current. Physical Review B 1996, 54, 9353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeur, K.; Buda-Prejbeanu, L.; Prenat, G.; Di Pendina, G. Study of two writing schemes for a magnetic tunnel junction based on spin orbit torque. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology.

- Nguyen, V.; Rao, S.; Wostyn, K.; Couet, S. Recent progress in spin-orbit torque magnetic random-access memory. npj Spintronics 2024, 2, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappert, C.; Fert, A.; Van Dau, F.N. The emergence of spin electronics in data storage. Nature materials 2007, 6, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.; Sbiaa, R.; Hirohata, A.; Ohno, H.; Fukami, S.; Piramanayagam, S. Spintronics based random access memory: a review. Materials today 2017, 20, 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, S.D.; Parkin, S.S.P. Spintronics. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2010, 1, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchon, A.; Železnỳ, J.; Miron, I.M.; Jungwirth, T.; Sinova, J.; Thiaville, A.; Garello, K.; Gambardella, P. Current-induced spin-orbit torques in ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic systems. Reviews of Modern Physics 2019, 91, 035004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Železnỳ, J.; Gao, H.; Vỳbornỳ, K.; Zemen, J.; Mašek, J.; Manchon, A.; Wunderlich, J.; Sinova, J.; Jungwirth, T. Relativistic Néel-order fields induced by electrical current in antiferromagnets. Physical review letters 2014, 113, 157201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadley, P.; Howells, B.; Železnỳ, J.; Andrews, C.; Hills, V.; Campion, R.P.; Novák, V.; Olejník, K.; Maccherozzi, F.; Dhesi, S.; et al. Electrical switching of an antiferromagnet. Science 2016, 351, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadley, P.; Reimers, S.; Grzybowski, M.J.; Andrews, C.; Wang, M.; Chauhan, J.S.; Gallagher, B.L.; Campion, R.P.; Edmonds, K.W.; Dhesi, S.S.; et al. Current polarity-dependent manipulation of antiferromagnetic domains. Nature nanotechnology 2018, 13, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Koepernik, K.; Rezaev, R.; Janson, O.; Železnỳ, J.; Jungwirth, T.; Felser, C.; van den Brink, J.; Sun, Y. Different types of spin currents in the comprehensive materials database of nonmagnetic spin Hall effect. npj Computational Materials 2021, 7, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Nomoto, T.; Arita, R. First-principles study of the tunnel magnetoresistance effect with Cr-doped RuO 2 electrode. Physical Review B 2024, 110, 064433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Yan, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Meng, Z.; Dong, J.; Zhu, M.; Cai, J.; Feng, Z.; Zhou, X.; et al. Room-temperature magnetoresistance in an all-antiferromagnetic tunnel junction. Nature 2023, 613, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duine, R.; Lee, K.J.; Parkin, S.S.; Stiles, M.D. Synthetic antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nature physics 2018, 14, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlauderer, S.; Lange, C.; Baierl, S.; Ebnet, T.; Schmid, C.P.; Valovcin, D.; Zvezdin, A.; Kimel, A.; Mikhaylovskiy, R.; Huber, R. Temporal and spectral fingerprints of ultrafast all-coherent spin switching. Nature 2019, 569, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landauer, R. Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process. IBM journal of research and development 1961, 5, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.H. The thermodynamics of computation—a review. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1982, 21, 905–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Lambson, B.; Dhuey, S.; Bokor, J. Experimental test of Landauer’s principle in single-bit operations on nanomagnetic memory bits. Science advances 2016, 2, e1501492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudenzi, R.; Burzurí, E.; Maegawa, S.; Van Der Zant, H.; Luis, F. Quantum Landauer erasure with a molecular nanomagnet. Nature Physics 2018, 14, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimel, A.; Kalashnikova, A.; Pogrebna, A.; Zvezdin, A. Fundamentals and perspectives of ultrafast photoferroic recording. Physics Reports 2020, 852, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Fu, X.; He, W.; Zhu, Y.; Dai, J.; Yang, W.; Zhu, W.; Bai, H.; Chen, C.; Wan, C.; et al. Observation of non-volatile anomalous Nernst effect in altermagnet with collinear N∖’eel vector. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.13427 2024.

- Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Yin, J.; Xu, S.; Mullan, C.; Taniguchi, T.; Watanabe, K.; Geim, A.K.; Novoselov, K.S.; Mishchenko, A. In situ manipulation of van der Waals heterostructures for twistronics. Science advances 2020, 6, eabd3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, B.; Che, B.; Xu, M.; Ang, Z.P.; Di, J.; Gao, H.J.; Yang, H.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Z. Recent advances in synthesis and study of 2D twisted transition metal dichalcogenide bilayers. Small Structures 2021, 2, 2000153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puretzky, A.A.; Liang, L.; Li, X.; Xiao, K.; Sumpter, B.G.; Meunier, V.; Geohegan, D.B. Twisted MoSe2 bilayers with variable local stacking and interlayer coupling revealed by low-frequency Raman spectroscopy. ACS nano 2016, 10, 2736–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Ling, X.; Liang, L.; Kong, J.; Terrones, H.; Meunier, V.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Probing the interlayer coupling of twisted bilayer MoS2 using photoluminescence spectroscopy. Nano letters 2014, 14, 5500–5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.D.; Xin, W.; Jiang, W.S.; Liu, Z.B.; Chen, Y.; Tian, J.G. High-precision twist-controlled bilayer and trilayer graphene. Advanced Materials 2016, 28, 2563–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Huang, B.; Tian, M.; Ceballos, F.; Lin, M.W.; Mahjouri-Samani, M.; Boulesbaa, A.; Puretzky, A.A.; Rouleau, C.M.; Yoon, M.; et al. Interlayer coupling in twisted WSe2/WS2 bilayer heterostructures revealed by optical spectroscopy. ACS nano 2016, 10, 6612–6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Suriyage, M.; Khan, A.R.; Gao, M.; Zhao, J.; Liu, B.; Hasan, M.M.; Rahman, S.; Chen, R.s.; Lam, P.K.; et al. Twisted van der Waals quantum materials: fundamentals, tunability, and applications. Chemical Reviews 2024, 124, 1992–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, W.; Wang, E.; Bao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Bao, K.; Chan, C.K.; Chen, C.; Avila, J.; Asensio, M.C.; et al. Quasicrystalline 30 twisted bilayer graphene as an incommensurate superlattice with strong interlayer coupling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 6928–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.y.; Kim, S.; Jung, S.W.; Hwang, J.; Kim, Y. Recent technical advancements in ARPES: Unveiling quantum materials. Current Applied Physics 2024, 60, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, K.; Ležaić, M.; Merte, M.; Freimuth, F.; Blügel, S.; Mokrousov, Y. Crystal Hall and crystal magneto-optical effect in thin films of SrRuO3. Journal of applied physics 2020, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Feng, W.; Yang, X.; Guo, G.Y.; Yao, Y. Crystal chirality magneto-optical effects in collinear antiferromagnets. Physical Review B 2021, 104, 024401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iguchi, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Ikemoto, Y.; Furukawa, T.; Itoh, H.; Iwai, S.; Moriwaki, T.; Sasaki, T. Magneto-optical detection of altermagnetism in organic antiferromagnet. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.15696 2024.

- Flebus, B.; Grundler, D.; Rana, B.; Otani, Y.; Barsukov, I.; Barman, A.; Gubbiotti, G.; Landeros, P.; Akerman, J.; Ebels, U.; et al. The 2024 magnonics roadmap. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2024, 36, 363501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Materials | Space Group | NRSS detection | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CrSb | [81,88,89,90] | ||

| MnTe | " | " | [72,94,96] |

| MnTe2 | " | [97] | |

| KV2Se2O | " | [100] | |

| Rb1V2Te2O | " | [99] | |

| GdAlSi | " | [113] | |

| RuO2 | " | [98,114] | |

| CoNb4Se8 | " | [115,116] | |

| Co1/4NbSe2 | " | [117,118] | |

| RuO2 | × | [95] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).