1. Introduction

Quantum correlation in low-dimensional magnets is an important topic in recent years which connects quantum information theory and condensed matter physics [

1,

2,

3]. In the context of quantum spin systems, quantum correlation refers to the entanglement and non-classical correlations that exist between quantum particles. In three-dimensional ferrimagnets or layered ferrimagnets, the interplay between topological phase transitions and quantum correlations give rise to a range of intriguing phenomena, where entanglement plays a crucial role in determining of ground state properties, and various other spin exotic phenomena observed in ferrimagnetic systems [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. On the other hand, the spin Nernst effect refers to the generation of an electric field perpendicular to both an applied temperature gradient and external field. It is an important phenomenon that occurs in materials with broken time-reversal symmetry, being a variant of the standard Nernst effect, where the generated electric field is proportional to the spin current rather than the charge current. In the framework of layered ferrimagnets, it may emerges in the system due to the interplay between temperature gradients, magnetic fields, and spin transport. In general, when a temperature gradient is applied through a ferrimagnet, it may induce a spin current perpendicular to the temperature gradient, resulting in a transverse voltage known as spin Nernst voltage. This effect is directly related to the magnon Hall effect and can provide insights into the spin dynamics of ferrimagnetic materials. To study quantum correlations and spin Nernst effect in a layered ferrimagnet, several theoretical models and computational techniques are employed such as spin wave theory, density matrix renormalization group, quantum Monte Carlo exact diagonalization. Being the predictions regarding quantum entanglement and spin Nernst effect depend on the specific model, Hamiltonian, and parameters used in the study. The goal is to explore these phenomena experimentally and theoretically to gain a deeper understanding of the behavior of quantum spins in magnetic materials. In the layered ferrimagnet, the influence of magnon bands on quantum correlation is an interesting aspect to explore. The Heisenberg model describes the system with anisotropic and isotropic interactions being a widely studied model for understanding of the behavior of layered ferrimagnets. In general, quantum correlations and entanglement in the Heisenberg model can be quantified using differents quantifiers as von Neumann entanglement entropy or entanglement spectrum. The von Neumann entropy provides information about the degree of entanglement between different regions of the spin system. The entanglement spectrum, on the other hand, gives insights into the energy levels associated with the entanglement.

The presence of anisotropic interactions introduces a characteristic anisotropy in the magnon dispersion which affects the entanglement dynamics, where the magnon bands determine the spectrum of magnons, which, in turn, affect the entanglement dynamics. The von Neumann entropy and spectrum may exhibit different behaviors depending on the specific features of the magnon bands, such as their bandwidth, dispersion relation, and anisotropy. For example, the presence of gapless magnon modes can lead to long-range entanglement and power-law scaling of the von Neumann entropy. On the other hand, the presence of a magnon gap can suppress entanglement and lead to short-range correlations. The study of magnon bands and their influence on entanglement in the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic Heisenberg model often involves theoretical approaches such as spin wave theory, bosonization techniques, or numerical methods like exact diagonalization, which provide insights into the entanglement properties and their connection to the magnon spectrum of the system. Thus, the understanding of the interplay of magnon bands and entanglement is crucial for unraveling of quantum nature of ferrimagnetic systems. Helping in characterizing of ground state properties, and exploring the emergence of novel phenomena in these systems [

20].

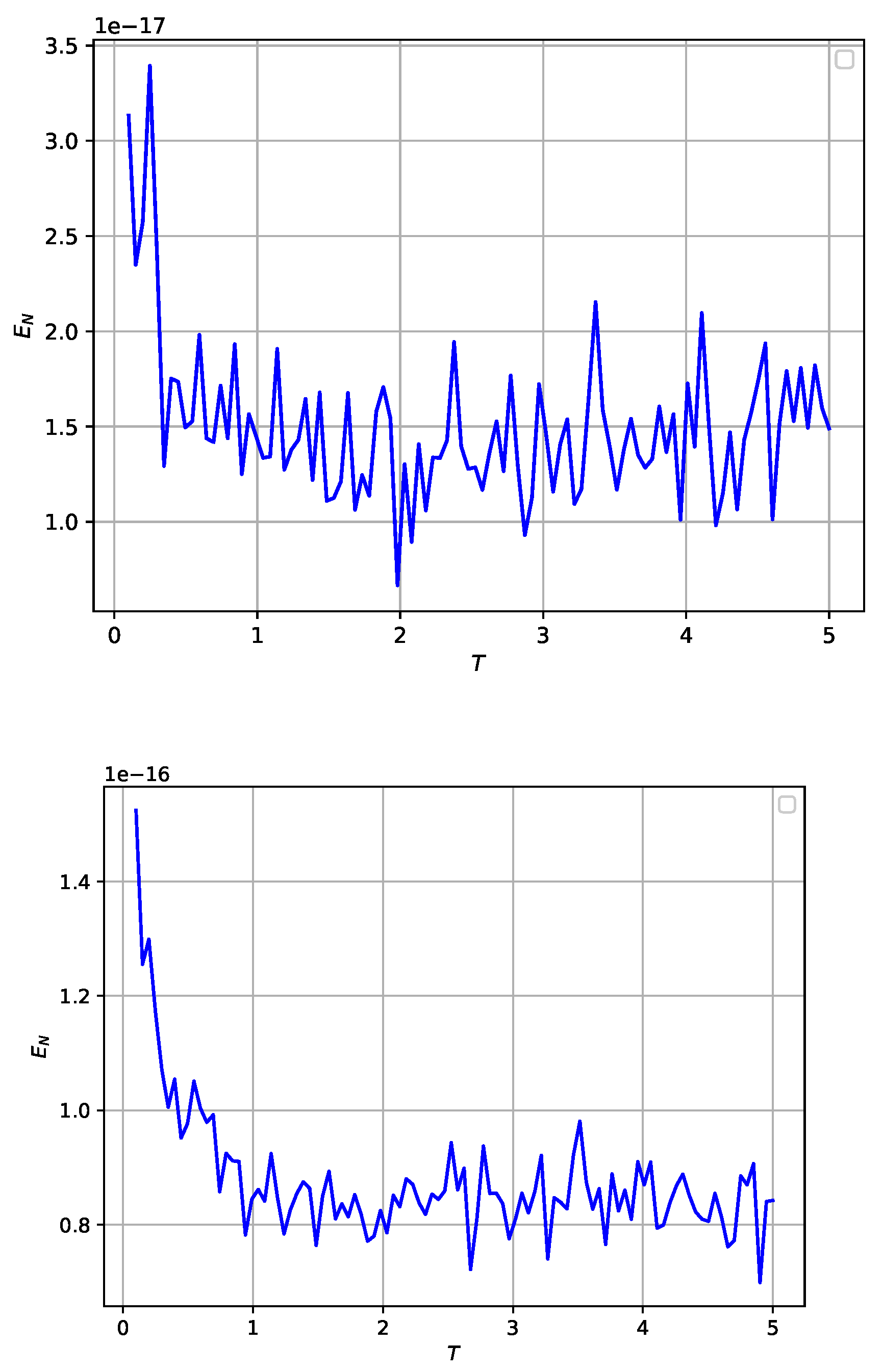

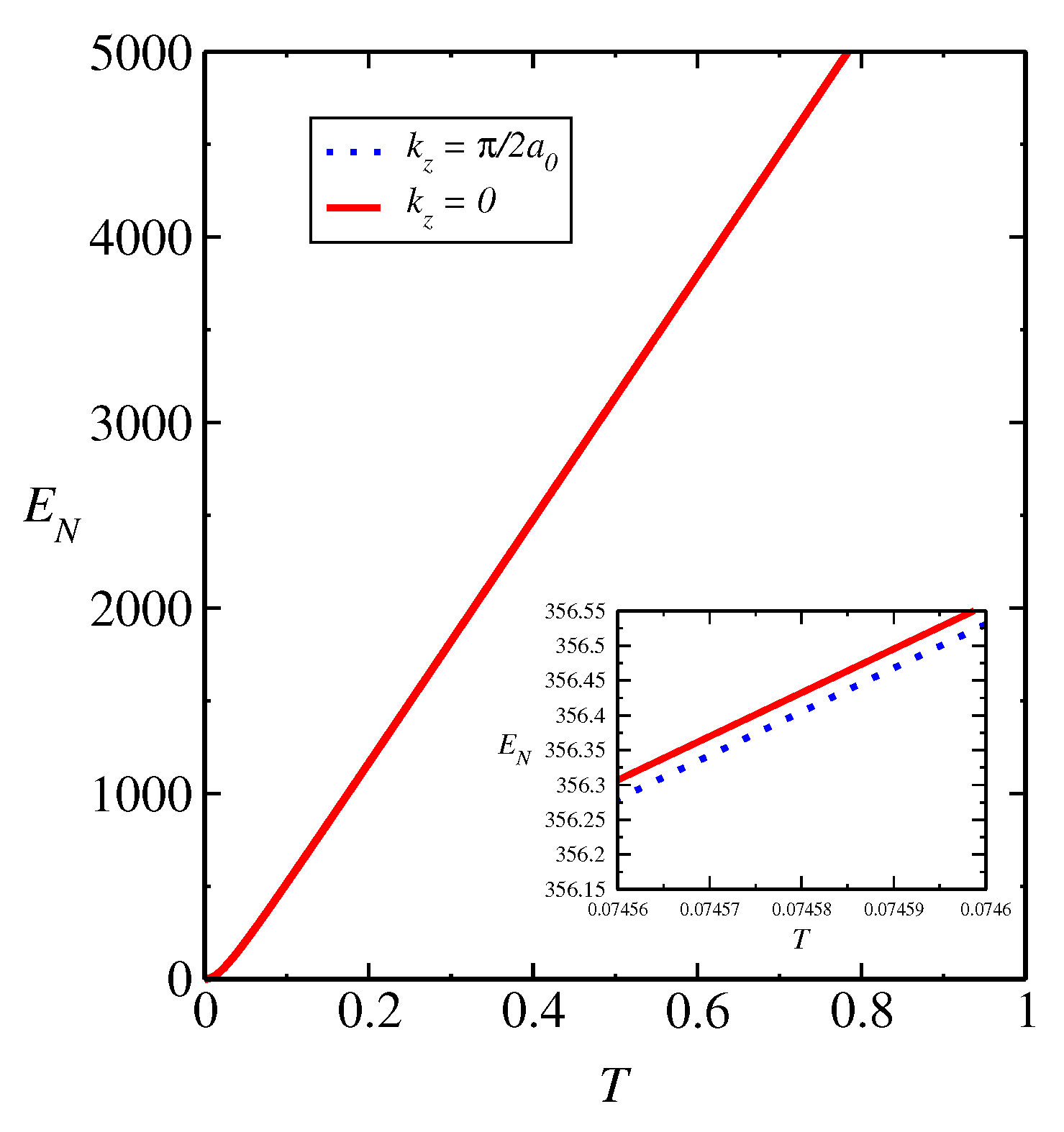

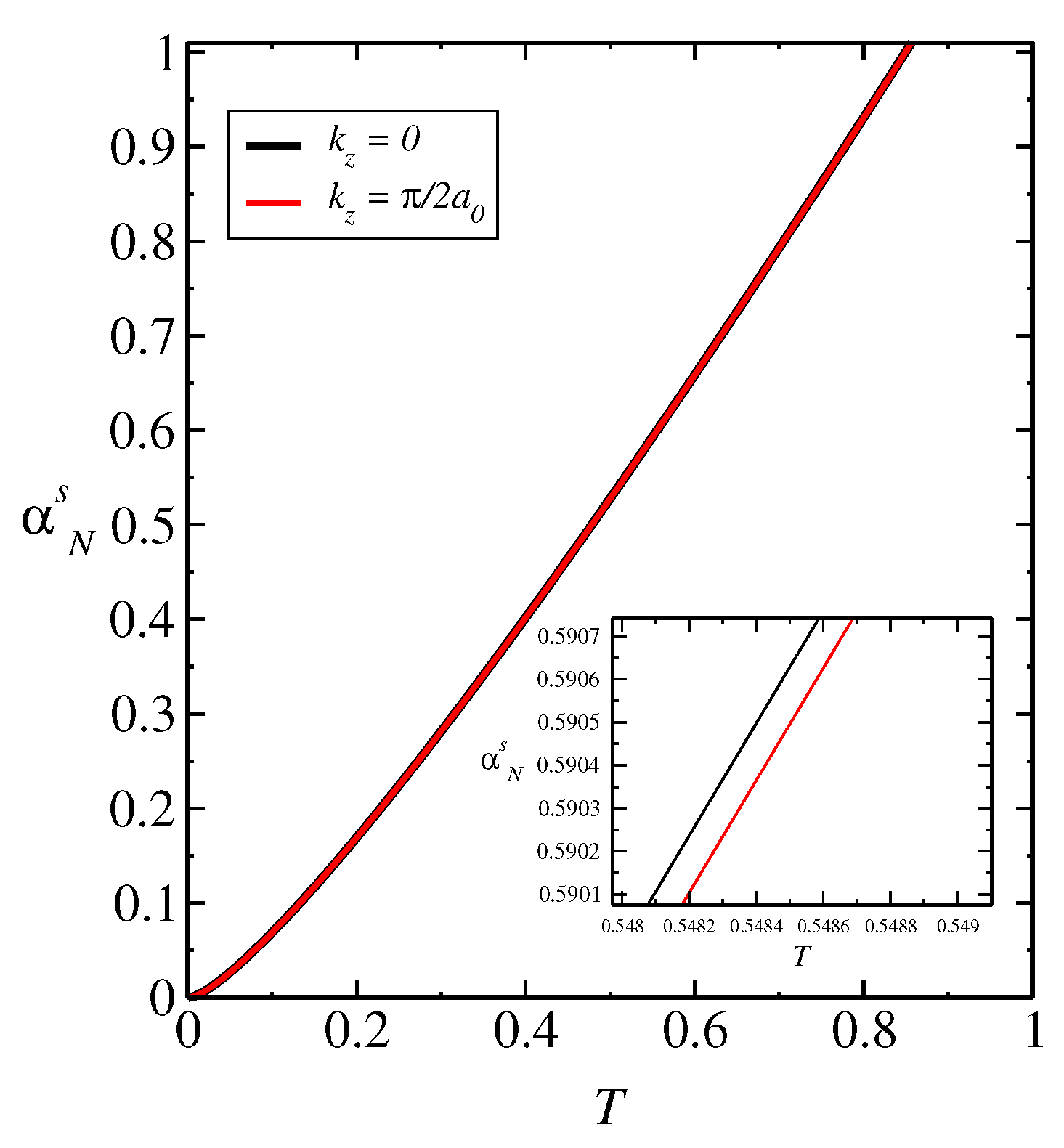

The goal of this paper is to analyze the influence of variation of the spin Nernst coefficient with coupling parameters on entanglement negativity. The paper is organized as follows: in

Section 2, we discuss about the three-dimensional layered ferrimagnet and theirs properties. In

Section 3, we present our analytical and numerical, where we discuss the variation of the spin Nernst conductivity and the behavior of the entanglement negativity as a function of

T. In the last

Section 4, we present our conclusions.

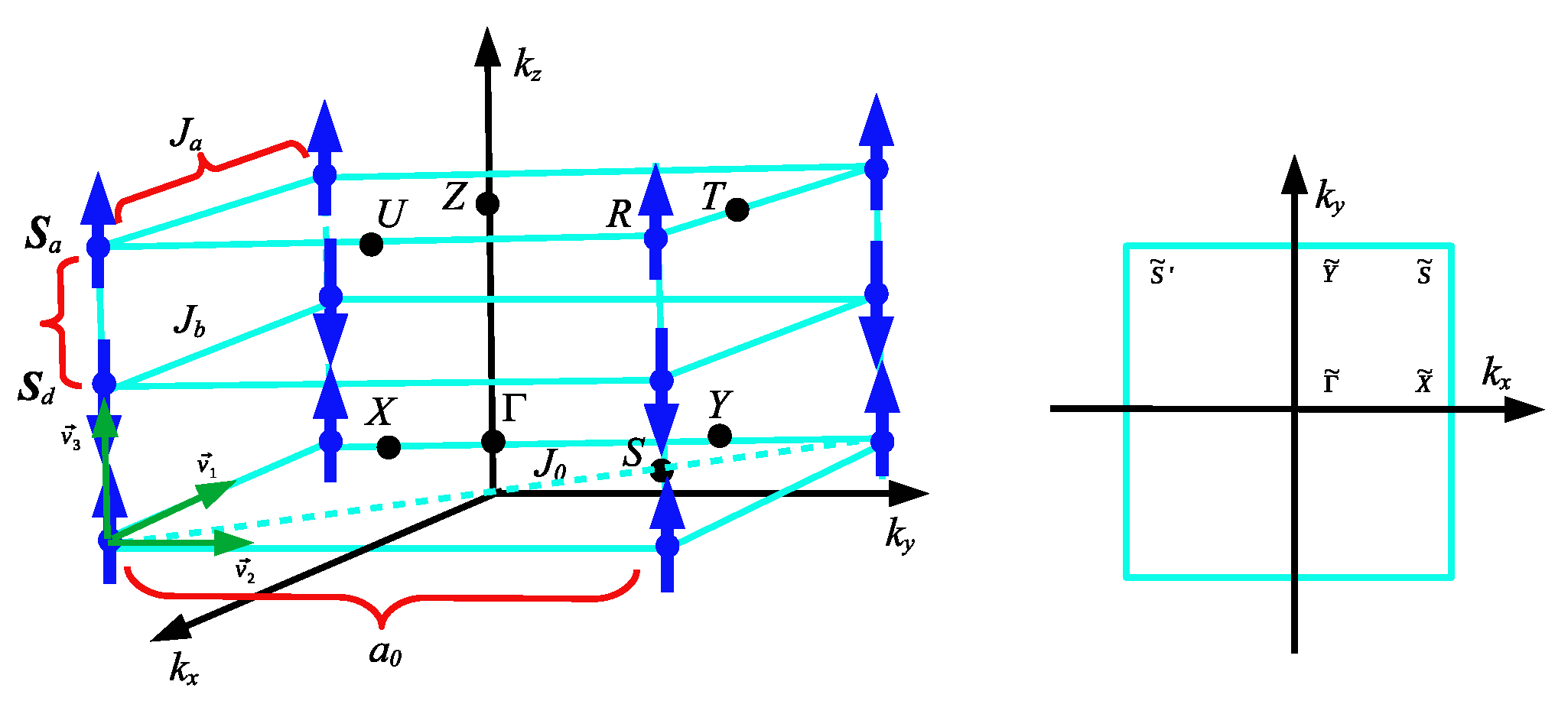

Figure 1.

Lattice model for a layered ferrimagnet with ferromagnetic layers along z axis. is the inter-layer coupling, and indicate the exchange interactions between nearest-neighbors. The red arrows are the basis vectors, defined as . and , with being the in-plane lattice spacing.

Figure 1.

Lattice model for a layered ferrimagnet with ferromagnetic layers along z axis. is the inter-layer coupling, and indicate the exchange interactions between nearest-neighbors. The red arrows are the basis vectors, defined as . and , with being the in-plane lattice spacing.

2. Model

General Hamiltonian for the layered ferrimagnet: For a layered ferrimagnet system with two types of ferromagnetic sublayers

a and

d sublattices stacked periodically, we consider the Hamiltonian with intralayer ferromagnetic exchange interactions for each sublattice; interlayer antiferromagnetic coupling between adjacent sublayers; magnetic anisotropy for each sublattice; external magnetic field applied to the system and dipole-dipole interaction as a perturbation to account for long-range dipolar effects. The model is composed by:

Antiferromagnetic interlayer exchange coupling between neighboring layers:

Magnetic anisotropy for each sublattice:

External magnetic field:

Dipole-dipole interaction (perturbative term):

where

is the unit vector between spins

i and

j and

is the distance between them.

is the external magnetic field vector. Thus, the total Hamiltonian for the system is:

The model captures the interactions within and between the two sublattices as well as the influence of anisotropy, external fields and long-range dipolar effects.

4. Outlook

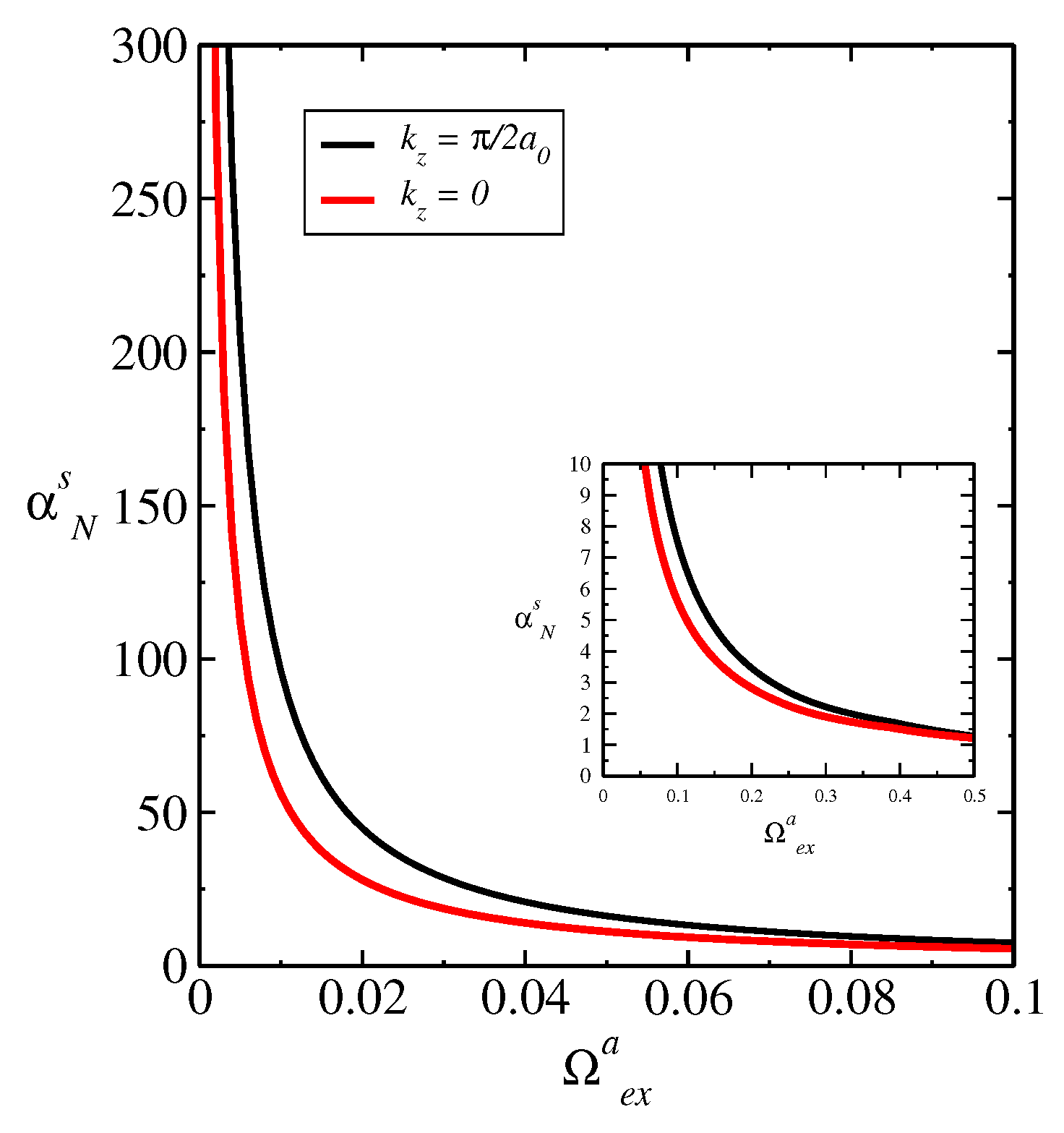

In brief, we analyzed the influence of dipole-dipole interaction on spin Nernst coefficient and quantum entanglement in a lattice model given by the layered ferrimagnet. The quantities reported well as the contribution to the Nernst coefficient of a given plane in

k-space and entanglement negativity are experimentally relevant [

1,

36]. It’s worth noting that the specific details and predictions regarding quantum correlations and spin Nernst effect would depend on the specific model, Hamiltonian, and parameters used in the study. We got that the changes reported in the quantities analyzed are very small, where the contributions from the analyzed planes in

k-space are relevant or dominant [

21]. Moreover, we get that the small change in the curves of the spin Nernst coefficient

as a function of

T, for different values

and for

, where the system suffers a topological phase transition, generating the same influence in the behavior of the curves of the entanglement negativity,

vs.

T. In a general way, the interplay of spin Nernst effect, entanglement negativity, and magnetism is a complex topic that requires further investigation and research. It is plausible that the spin Nernst effect influences the entanglement properties of the layered ferrimagnet by affecting the spin dynamics and correlations within the system. However, the specific details and quantitative aspects of this influence must depend on the particular characteristics of the material as well as its lattice structure and magnetic interactions.

Layered ferrimagnet with single-ion anisotropy K, external field with dipole-dipole interaction: The model is given by the Hamiltonian

where the unit vector

is in the direction of the easy axis, specified to

z (

x) for the in-plane (out-of-plane) magnetized geometry,

and

is the unit vector pointed in the direction of the line joining of nearest-neighbors spins, and

is the distance between them. Moreover,

is the vacuum permeability constant,

g is the Landé factor and

is the Bohr magneton. The representation of the lattice considered is given in

Figure 1.

is the single-ion anisotropy and

are the ferrimagnetic intra-layer exchanges. The notation used

ℓ and

i in

denote the layer and the site, respectively. Being

and

for the sublattice a (d). Moreover,

,

and

indicate the exchange constants between nearest-neighbors. The unit vector

is the direction of the easy axis, which is specified to

x direction in-plane (out-of-plane).

HP transformation: We performed the Holstein-Primakoff (HP) transformation expanded up to first order, after performing a local rotation of the spin operators of the model above to the new operators

,

and

[

21], so that the mean-field direction of the spins points along to the local

z axis:

where we obtain the magnon Hamiltonian in the form of creation and annihilation operators,

and

, respectively.

Semimetal phase in collinear configuration: Whether the magnetic field is applied along to the easy axis with intensity below of the spin flop transition, we have a perpendicularly magnetized geometry,

. The ferrimagnetic state is in the collinear configuration with the spins aligning in the

z direction, corresponding to

. The addition of the dipole-dipole interaction opens an anti-crossing gap at the intersection regions of the

plane within the Brillouin zone, while the bands display linear crossings at the Brillouin zone edge, reflecting in the role of dipole-dipole interaction as a source of magnon spin-orbit coupling [

21,

22] and nontrivial magnon band topology [

23,

24]. We consider the dipole-dipole interaction as a perturbation, considering its smaller magnitude compared to the other energy terms and projecting the magnon Hamiltonian into a reduced subspace with the basis consisting of the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian excluding the dipole-dipole interaction.

In the collinear configuration, we take the discrete Fourier transform of the bosons operators

and the Bogoliubov transformation to get the dispersion relation of magnons [

21]

where

and

,

,

,

. Furthermore, we have

.

corresponding to external field component along to the easy axis. In addition, we have the form factors

where

the lattice spacing constant.