1. Introduction

Brazilian viticulture occupies approximately 75,000 hectares of vineyards [

1], with the states of Rio Grande do Sul, São Paulo, Pernambuco, Santa Catarina, Paraná, Bahia, and Minas Gerais standing out as the main production hubs. In terms of fine wine production, a 9.3% increase was recorded in 2021 and 2022, with a notable growth of 19.5% in red wine production, while volumes of white and rosé wines remained virtually stable [

2]. According to IBGE estimates, grape production in Brazil reached 1,450,805 tons in 2022.

In southeastern Brazil, an emerging viticulture has shown significant potential for high-quality fine wine production, driven by the adoption of the double-pruning technique [

3,

4,

5]. Although relatively recent in this region, the system has rapidly expanded, as evidenced by the increasing number of vineyards, wineries, production volumes, and commercial brands.

The double-pruning technique modifies the phenological cycle of the grapevine, allowing harvest to occur during the dry winter season—a period characterized by mild daytime temperatures, lower nighttime temperatures, and minimal rainfall. This strategy enables the harvest of grapes under optimal health and ripening conditions, resulting in berries with improved physicochemical and biochemical attributes, and consequently, wines of superior intrinsic quality [

6].

For the production of fine wines in new viticultural regions, it is essential to assess the adaptability of grapevine cultivars in relation to the specific characteristics of each terroir. The double-pruning management enhances sugar accumulation and phenolic ripening, promoting superior sensory attributes and improving wine quality [

7].

Although winter wine production in southeastern Brazil began only in 2004, in southern Minas Gerais, the system has already expanded to over 35 distinct wine-producing regions, with a growing community of winegrowers [

8]. This expansion underscores the need to evaluate the agronomic and qualitative performance of grapevine cultivars under the specific conditions imposed by double-pruning in subtropical climates.

Within this context, double pruning has emerged as a promising strategy for advancing viticulture in the state of São Paulo [

9]. Among the Vitis vinifera L. cultivars grown in the region, the red cultivars ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Merlot’ and the white cultivar ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ are particularly notable due to their recognized enological potential [

10].

Given the expansion of the double-pruning system, the present study aimed to evaluate the duration of phenological stages, thermal requirements, ripening curve, yield, productivity, physicochemical characteristics, and biochemical composition of the must of the cultivars ‘Sauvignon Blanc’, ‘Merlot’, ‘Tannat’, ‘Pinot Noir’, ‘Malbec’, and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ grown under subtropical conditions and managed using the double-pruning technique.

2. Materials and Methods

Experimental Site

The experiment was conducted from February 2023 to August 2024 in a vineyard located at Santa Lúcia do Tietê Farm, in the municipality of Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo State, Brazil (22°32’25’’ S, 48°24’13’’ W; altitude: 580 m). The experimental area is situated in a transitional zone between the tropical montane Atlantic Forest and the Cerrado biome, and is characterized by a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) according to the Köppen–Geiger classification, with hot summers and evenly distributed rainfall throughout the year.

Vineyard Establishment and Growing Conditions

The vineyard establishment began in 2020 with soil preparation, liming, and corrective fertilization based on chemical analysis. A vertical shoot positioning (VSP) trellis system with wooden posts was installed, with spacing of 3.0 m between rows and 1.0 m between vines. Certified grapevine seedlings were planted in November 2020.

The vines were managed under a double-pruning system over two production cycles. Training pruning was performed on August 17, 2022, and August 13, 2023, while production pruning was carried out on February 12, 2023, and February 17, 2024, aiming for harvest during the dry winter period typical of southeastern Brazil. Following pruning, hydrogen cyanamide (Dormex®, BASF, Ludwigshafen am Rhein, Germany) was applied at 5% concentration, combined with 0.1% silicon-based surfactant, to promote uniform budbreak.

Canopy management practices included leaf removal, shoot thinning, tipping, tying, and berry thinning (40–70%). Top-dressing fertilizations were performed based on soil analysis and the recommendations of Bulletin 100 from the Agronomic Institute of Campinas [

11]. At the onset of berry ripening (veraison), protective nets with 10% shading were installed to guard against hail, birds, and bees.

Experimental Design and Treatments

The experimental design was a randomized complete block design (RCBD), with six treatments and eight blocks, totaling 48 experimental plots. Each plot consisted of five grapevines. The treatments corresponded to six Vitis vinifera L. cultivars: ‘Sauvignon Blanc’, ‘Merlot’, ‘Tannat’, ‘Pinot Noir’, ‘Malbec’, and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’.

Evaluated VariablesDuration of Phenological Stages

Phenological stages were characterized according to the scale proposed by [

12]. Evaluations were performed twice a week until flowering and weekly thereafter until harvest. The phenological stages observed were:

Budburst (BB): 50% of buds with visible leaves;

Flowering (FL): 50% of flowers open;

Fruit Set (FS): berries with a diameter greater than 2 mm;

Beginning of Ripening (BR): 50% of berries showing color change and softening;

Harvest (H): 100% of berries with appropriate color and physiological ripeness.

Thermal Demand

Thermal demand was estimated using the accumulation of growing degree days (GDD), following the method proposed by [

13], using the equation:

GDD = Σ (Tₘ − 10 °C) × DAP

where Tₘ represents the daily mean temperature (°C), 10 °C is the base temperature for grapevine development, and DAP refers to days after pruning.

Ripening Curve

Grape ripening was monitored weekly from the onset of berry ripening. Soluble solids (SS, °Brix) were determined using a digital refractometer (Reichert r2i300); titratable acidity (TA, % tartaric acid) was measured by titration with 0.1 N NaOH until pH 8.2–8.4; pH was assessed by direct reading using a digital pH meter (Tecnal); and the maturity index (SS/TA) was calculated. For each sampling, 16 clusters per plot were collected, and six berries were sampled from each cluster (two from each third).

Harvest, Yield, and Physicochemical Quality of Grape Must

Harvest was carried out when clusters reached physiological maturity. At this stage, all clusters were counted and weighed to determine the total number of clusters and yield per plant, and to estimate productivity in tons per hectare (t ha⁻¹).

From a sample of 15 clusters per plot, fresh weight, length, and width of clusters, berries, and rachis were evaluated, as well as the number of berries per cluster.

For physicochemical analyses of the must, 100 berries per experimental plot were used. The must was obtained by manual pressing of the berries. Soluble solids content (SS) was determined by direct refractometry using a digital refractometer with automatic temperature compensation (Reichert r2i300), and the results were expressed in °Brix. Must pH was measured by direct reading using a pH meter (Tecnal).

Titratable acidity (TA) was determined by titrating 5 g of must diluted in 100 mL of distilled water with 0.1 N sodium hydroxide solution, using phenolphthalein as an indicator. Results were expressed as percentage of tartaric acid.

Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant ActivityBiochemical Characteristics of Berries

Biochemical analyses were carried out at the Laboratory of Plant Chemistry and Biochemistry, UNESP/Botucatu. Ten berries per cluster were collected (three from the top, four from the middle, and three from the bottom). The berries were halved, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground using mortar and pestle. The resulting samples were stored at −20 °C until analysis, which was performed in triplicate.

For supernatant extraction, 300 mg of pulp were mixed with 5 mL of acidified methanol (80%). The mixture was homogenized for 30 seconds in a vortex and subjected to ultrasonic bath for 20 minutes. It was then centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes at 5 °C. The supernatant was collected, and the extraction procedure was repeated once more. The combined extracts were stored in amber vials for further analysis.

Total Phenolic Compounds

Total phenolic content was quantified using the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, according to Singleton and Rossi (1965). Results were expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents per kg of fresh matter (mg GAE/kg FM). For this, 0.5 mL of the extract was mixed with 0.5 mL of distilled water, 0.5 mL of diluted Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (1:4), and 2.5 mL of 4% sodium carbonate solution. The mixture was vortexed and kept in the dark for one hour before reading absorbance at 725 nm using a spectrophotometer.

Total Flavonoids

Total flavonoid content was determined using aluminum chloride (AlCl₃) and a benchtop spectrophotometer. Four milliliters of the extract were homogenized and left in the dark for 30 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 25 minutes at 5 °C. Absorbance was read at 510 nm, and results were expressed as mg quercetin equivalent per 100 g fresh matter, according to [

14].

Total Anthocyanin Content

Total anthocyanins (TAC) were quantified by the pH differential method described by [

15]. An aliquot of the extract was diluted in two buffer solutions: 0.025 M potassium chloride (pH 1.0) and 0.4 N sodium acetate (pH 4.5). Absorbance readings were taken at 510 nm (cyanidin-3-O-glucoside peak) and 700 nm (turbidity correction) using a spectrophotometer. Results were expressed as mg cyanidin-3-O-glucoside equivalents per 100 g of grape sample.

Antioxidant Activity

Antioxidant activity was assessed using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay, according to [

16]. Results were calculated using a Trolox standard curve (y = 23.606x + 2.5805; R² = 0.9961), and expressed as μg Trolox equivalents per 100 g of sample.

Additionally, the FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power) method was applied according to [

17], using a mixture of 300 mM acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 2.5 mL of 10 mM TPTZ (in 40 mM HCl), and 2.5 mL of FeCl₃. Absorbance was read at 595 nm, and results were expressed as mmol FeSO₄ equivalents per 100 g of sample (y = 0.007 + 0.0044; R² = 0.9973).

Statistical Analysis

Data were subjected to tests for normality and homogeneity of variances. A two-factor ANOVA was performed in a split-plot design over time, with cultivars as main plots and production cycles as subplots. The experimental design was a randomized complete block with eight replicates and five plants per plot. Means were compared using Tukey’s test at 5% significance. Ripening curve data were analyzed by polynomial regression. All statistical analyses were performed using SISVAR 5.6 software [

18].

3. Results

3.1. Climatic Data

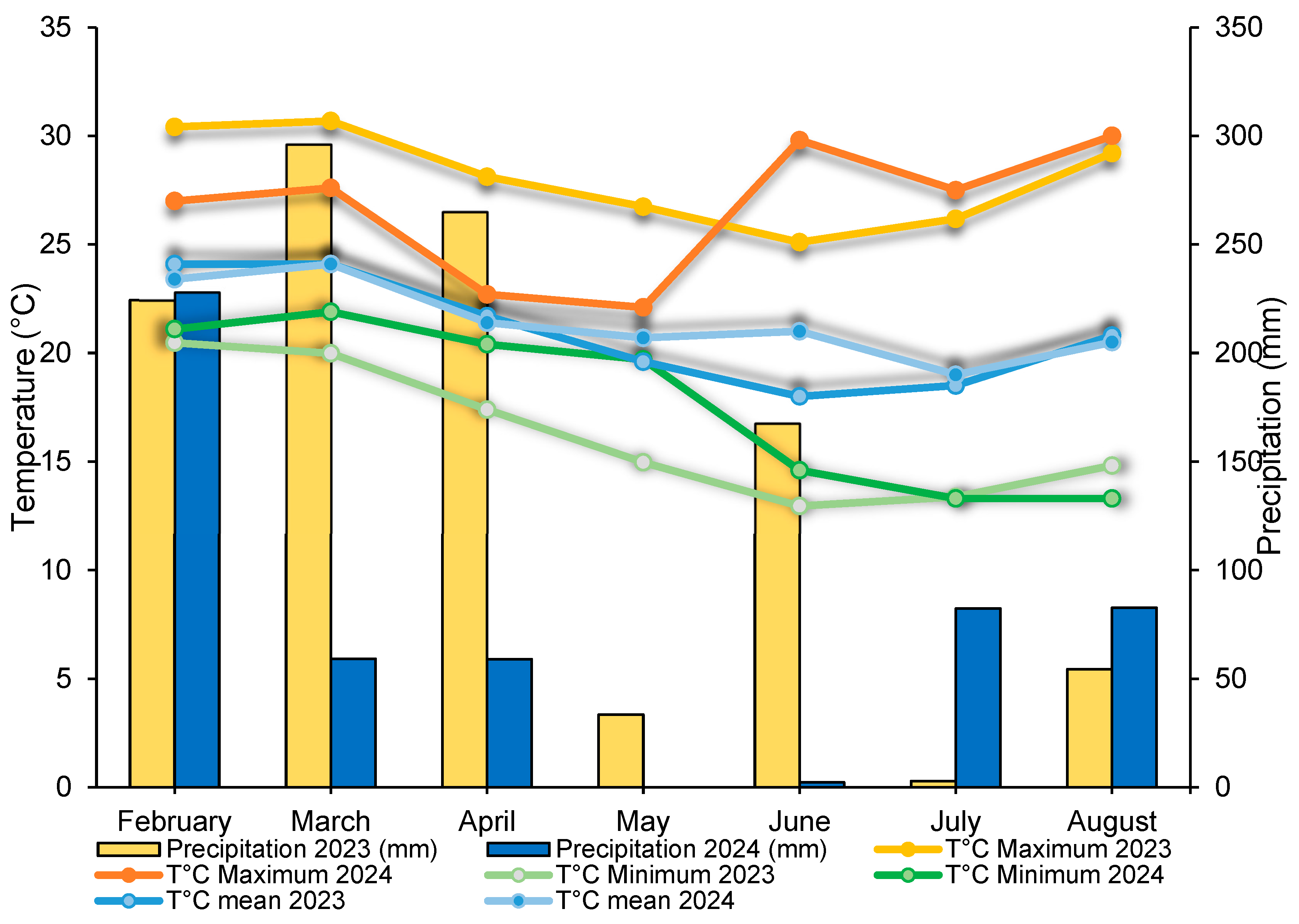

According to the climatic data obtained during the two production cycles (

Figure 1 and Figure 2), the area exhibits climatic characteristics similar to those of other winter wine-producing regions in southeastern Brazil, such as in the states of Minas Gerais and São Paulo [

19,

20].

Climatic conditions favorable to grape cultivation for winter wine production include reduced rainfall during the harvest period (June to August), low relative humidity, high thermal amplitude (below 30 °C), and high solar radiation incidence. These factors contribute to a slower ripening process, resulting in greater accumulation of phenolic compounds, aroma compounds, and aroma precursors. Such conditions are essential for the production of both red and white wines with high enological potential [

4,

21].

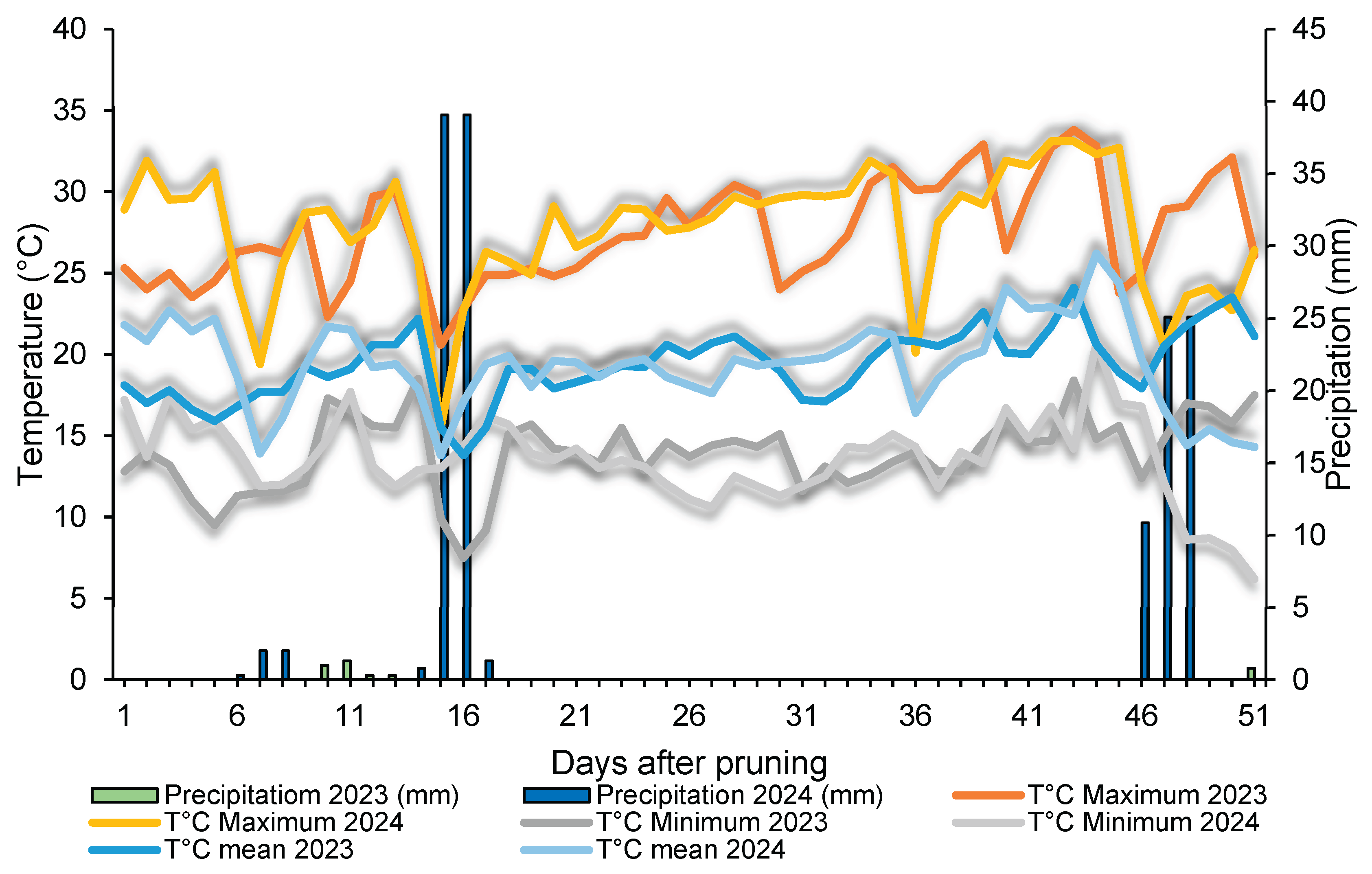

During the 2023 growing cycle, total annual rainfall was 2,135.4 mm, with an average temperature of 23.4 °C and a relative humidity of 76%. In 2024, a reduction in these climatic indices was observed, with total precipitation of 989.0 mm, a mean annual temperature of 19.6 °C, and relative humidity of 75.5%. During the berry ripening period, meteorological data collection was intensified and conducted daily in both production cycles (

Figure 1a and 1b).

3.2. Duration of Phenological Stages

Significant variations were observed in the duration of phenological stages between the 2023 and 2024 production cycles. In 2024, budburst occurred on average 13.1 days after pruning, and harvest took place at 128.0 days, while in 2023 these events occurred at 12.4 and 146.5 days, respectively. Thermal demand was also lower in 2024, with an accumulated total of 1,207.6 degree-days, in contrast to 1,746.3 degree-days recorded in the previous cycle, reflecting differences in climatic conditions and management practices between years.

The total duration from pruning to harvest varied among cultivars: Sauvignon Blanc (146 days), Merlot (159 days), Tannat (156 days), Pinot Noir (146 days), Malbec (158 days), and Cabernet Sauvignon (142 days) (

Table 1).

The duration of the phenological stages varied significantly among grapevine cultivars and production cycles, highlighting the influence of genetic characteristics and environmental conditions on the developmental cycle. The stages of budburst, flowering, fruit set, onset of ripening, and harvest exhibited notable differences, directly affecting vineyard management and harvest planning.

Budburst

Budburst showed little variation between the production cycles: an average of 12.4 days in 2023 and 13.1 days in 2024. The shortest period was recorded for ‘Merlot’ (11.9 ± 0.83 days) and ‘Malbec’ (11.8 ± 0.89 days) in the first cycle, while the longest was observed for ‘Malbec’ in the second cycle (13.6 ± 0.52 days).

This phenological stage marks the beginning of the vegetative cycle and is crucial for the overall development rate. Early budburst may accelerate the cycle but increases the risk of damage from late frosts in regions with unstable climates [

22].

Full Flowering

Marked differences were observed between production cycles. The period from pruning to flowering was longer in 2023 (46.5 days) compared to 2024 (32.6 days), due to higher temperatures in the latter (

Figure 1), which accelerated phenological development.

The cultivars ‘Tannat’ (53.9 ± 6.20 days) and ‘Merlot’ (48.3 ± 4.5 days) exhibited the longest pruning-to-flowering periods. In contrast, ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ had the shortest (37.9 days). Early flowering, as observed in ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ and ‘Malbec’, may be advantageous in regions requiring shorter production cycles.

Fruit Set

The duration from pruning to fruit set was shorter in 2024 (36.3 days) than in 2023 (49.9 days). ‘Tannat’ consistently exhibited the longest cycle in both years (58.4 ± 5.53 days in 2023 and 39.0 days in 2024), while ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ showed the shortest durations (47.1 days in 2023 and 34.8 ± 1.49 days in 2024).

This stage is highly sensitive to environmental factors such as water deficit and temperature [

23], and cultivars with shorter cycles may exhibit greater resilience under climatic stress.

Beginning of Ripening

The onset of ripening occurred slightly earlier in 2024 (91.5 days) compared to 2023 (92.1 days). ‘Tannat’ exhibited the latest ripening (97.0 ± 3.33 days in 2023 and 95.3 ± 1.04 days in 2024), whereas ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ was the earliest (87.9 ± 0.64 days in 2023 and 85.8 ± 4.27 days in 2024).

This stage directly influences wine quality, as it defines the balance between sugars and acids. Early ripening, as seen in ‘Sauvignon Blanc’, is often associated with fresher wines with higher acidity [

24,

25].

Harvest

In the 2023 production cycle, the period from pruning to harvest ranged from 121 to 185 days, with ‘Pinot Noir’ and ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ being the earliest cultivars and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ the latest. In 2024, all cultivars presented shorter cycles, with ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ again showing the shortest duration (121 days), while ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ remained the last to be harvested (142 days).

The shortened cycle in 2024 was mainly attributed to climatic conditions between February and June, with average temperatures of 23.4 °C and 21 °C, respectively.

Shorter cycles can reduce disease pressure, favoring early-ripening cultivars in regions with short summers [

26,

27]. Cycle duration influences both sensory attributes and vineyard management feasibility, and is thus critical for production planning.

3.3. Thermal Demand of Grapevines

In 2023, the average thermal requirement was higher (1,476.9 GDD), reflecting greater vine demand to complete the cycle. ‘Tannat’ showed the highest accumulation (1,785.5 ± 2.25 GDD), followed by ‘Malbec’ (1,769.8 ± 0.49) and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ (1,760.3 ± 0.96). In contrast, the 2024 cycle required less thermal accumulation, with ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ needing 1,377.8 ± 5.46 GDD.

A base temperature of 10 °C was used for GDD calculations, below which no vegetative development occurs [

28]. In comparison with other regions, ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ requires around 1,200 GDD in Santa Catarina (Epagri, 2005), and up to 1,625 GDD in semiarid regions [

29]. Thermal demand directly affects the pace of development, with higher temperatures shortening the intervals between phenological stages [

30].

Understanding thermal requirements allows prediction of phenological progression and enables better harvest scheduling, optimizing both management practices and labor organization.

3.4. Yield Components and Physical Characteristics

Significant differences were observed in the physical characteristics of clusters, berries, and rachis among cultivars (

Table 2), with variations attributed to genetic factors and climatic conditions.

‘Sauvignon Blanc’ showed consistency across cycles, with cluster weights of 87.9 g (Cycle I) and 84.5 g (Cycle II), and an increase in cluster length (8.29 cm in Cycle II). ‘Tannat’ exhibited a marked increase in cluster weight (from 125.4 g to 143.0 g) and overall size.

In contrast, ‘Pinot Noir’ and ‘Malbec’ showed reduced cluster weight in the second cycle. Cluster width increased across all cultivars in Cycle II compared to Cycle I, while length varied, with decreases observed only in ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’. Berry size also varied, with ‘Malbec’ showing notable increases in both length and width.

Smaller berries (with mass below 2.0 g) are favorable for the extraction of phenolic compounds, which are essential for red wine production [

31] (Conde et al., 2007). The number and size of berries directly affect cluster mass [

32].

Cultivars such as ‘Tannat’ produce robust clusters suitable for full-bodied wines, while ‘Pinot Noir’ tends to yield lighter, more aromatic wines.

Number of Clusters per Plant

The number of clusters per plant varied significantly among cultivars. ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ recorded the highest number in the second cycle (11.8 ± 0.99 clusters plant⁻¹), while ‘Pinot Noir’ showed the lowest value in the first cycle (4.88 ± 1.36 clusters plant⁻¹) (

Table 3).

The increased yield observed in Cycle II reflects favorable environmental conditions, such as temperature and water availability, which contributed to greater biomass accumulation. This trend was consistent across cultivars, suggesting that the second cycle was more suitable for maximizing productivity.

Significant differences (p < 0.05) between cycles and among cultivars confirm the influence of double-pruning management under subtropical conditions. The superior performance in Cycle II may be associated with a greater number of fruitful shoots and increased bud fertility. These results indicate a strong genotype × environment interaction. ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ stood out for its high yield and productivity, demonstrating good adaptability to the double-pruning system, whereas ‘Malbec’ and ‘Pinot Noir’ showed lower performance, indicating greater sensitivity to the growing conditions.

3.5. Yield and Productivity

Grape yield varied significantly among cultivars and between production cycles. The cultivars ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ showed the highest yields in the second cycle (3.03 ± 0.06 kg plant⁻¹ and 2.75 ± 0.15 kg plant⁻¹, respectively), whereas ‘Malbec’ exhibited the lowest performance (0.50 ± 0.13 kg plant⁻¹ in Cycle I), likely due to poor adaptation to the local conditions. According to [

33], the number of clusters per plant has a direct influence on grapevine yield under this management system. All cultivars showed increased yield in Cycle II compared to Cycle I, which can be attributed to a greater formation of fruitful shoots.

Productivity followed the same trend observed for yield. The highest values were recorded for ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ in both cycles, with particularly high productivity in Cycle II for ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ (10.8 ± 0.20 t ha⁻¹), followed by ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ (9.82 ± 0.53 t ha⁻¹). The lowest value was observed for ‘Malbec’ in Cycle I (1.79 ± 0.48 t ha⁻¹) (

Table 3). ‘Tannat’ showed higher productivity than ‘Pinot Noir’ and ‘Malbec’, reaching 3.89 t ha⁻¹ in the second cycle.

These results suggest that double-pruning management under subtropical conditions benefited cultivars such as ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, which demonstrated better adaptation and higher productivity. ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ has shown high productivity in different Brazilian regions, particularly when managed with the double-pruning technique for winter wine production. In contrast, cultivars such as ‘Malbec’ may require specific management adjustments to optimize their performance under these conditions.

According to [

34], the factors influencing grapevine productivity can be grouped into permanent and cultural components. Permanent factors include imposed elements such as climate, soil, and biological environment, as well as selected factors such as cultivar, rootstock, planting density, and row orientation. Cultural factors encompass training systems, pruning strategies, irrigation methods, fertilization, and phytosanitary management. Additionally, [

35] emphasized that grape production is influenced by multiple factors that determine both fruit quality and productivity.

The production of fine wine grapes demands extensive technical knowledge to perform the cultural practices required for high-quality fruit, as well as significant labor input for manual vineyard operations, which raises the overall production costs [

36].

The cultivar ‘Merlot’ did not produce enough fruit to allow evaluation of physical characteristics under double-pruning management in subtropical conditions. This contrasts with southern Brazil, where it is considered one of the most important cultivars.

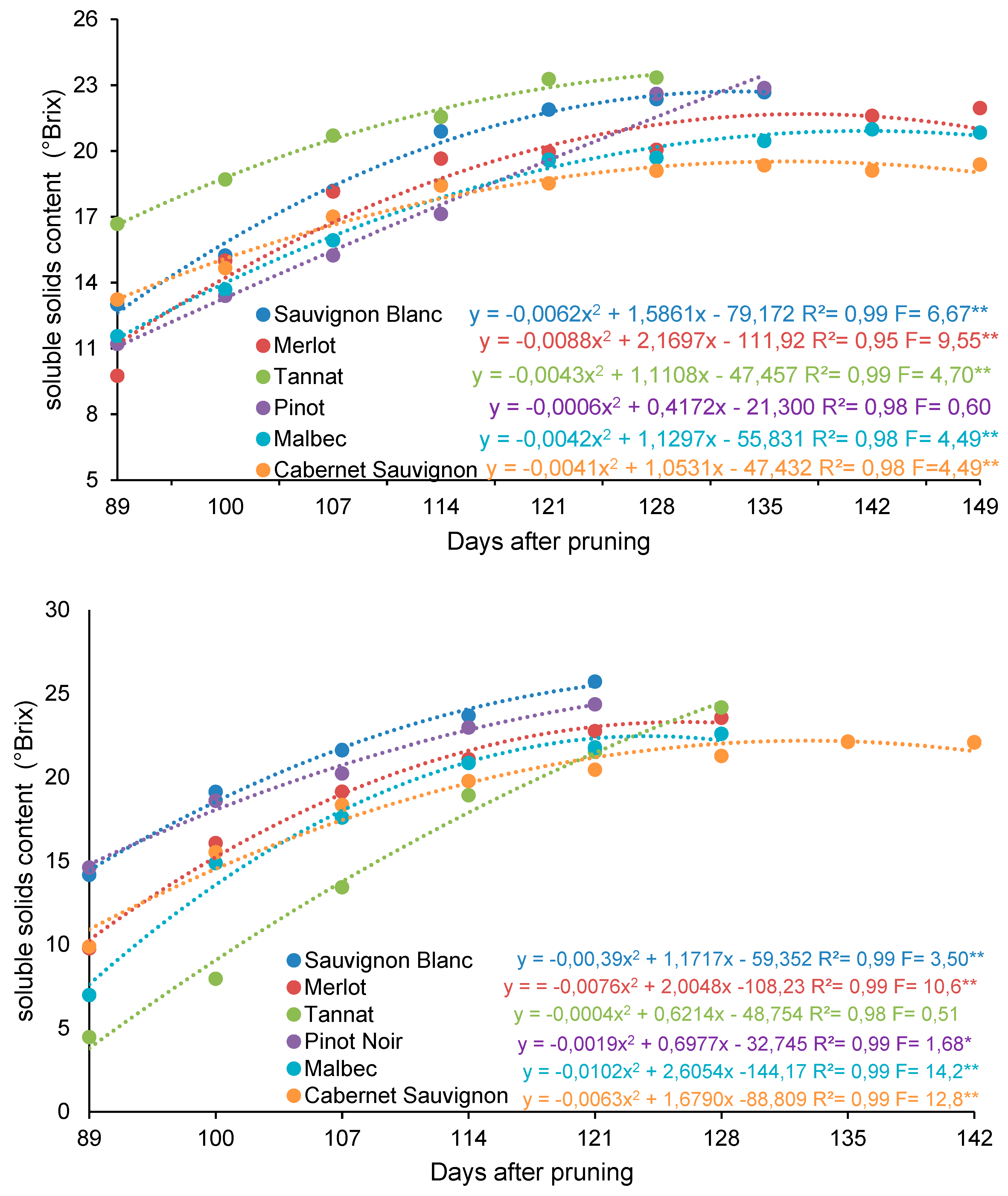

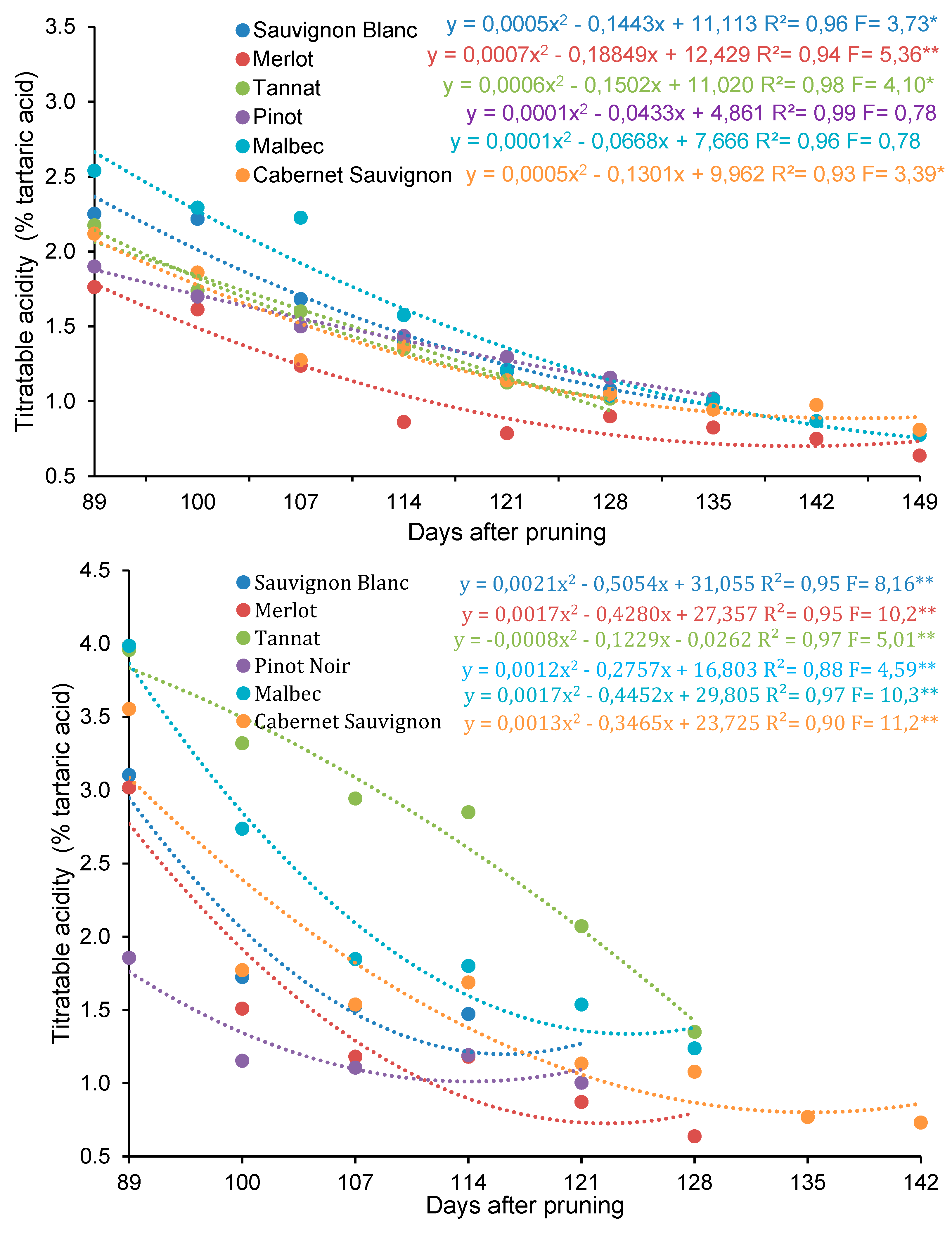

3.6. Berry Ripening Progress

On average, berry ripening began 93 days after pruning (DAP) during the 2023 cycle, with a thermal accumulation of 1,745.3 growing degree days. The cultivars ‘Sauvignon Blanc’, ‘Merlot’, ‘Tannat’, ‘Pinot Noir’, ‘Malbec’, and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ began ripening at 88, 94, 97, 88, 95, and 94 DAP, respectively.

Ripening progress showed significant variation among cultivars (p > 0.05), although a consistent pattern of uniformity was observed within each variety. Ripening in the 2023 season began on May 16 (93 DAP), with ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ and ‘Pinot Noir’ showing early ripening (May 11, 88 DAP), while ‘Malbec’ and ‘Tannat’ exhibited the latest onset at 95 and 97 DAP, respectively.

Analyses of the ripening curve revealed significant differences among cultivars for soluble solids (°Brix), pH, titratable acidity (TA), and maturity index (MI). Over the course of the production cycle, a typical ripening trend was observed: increases in SS and pH and a decrease in acidity, reflecting progressive ripening (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Quadratic models provided a good fit for the variables as a function of days after the onset of ripening.

3.7. Soluble Solids Content (°Brix)

Soluble solids content (SS), expressed in °Brix, is one of the main indicators of grape maturity, as it reflects sugar accumulation in the berries. Among the evaluated cultivars, ‘Tannat’ reached the highest value, with 23.4 °Brix at 128 DAP, indicating high potential alcohol content for winemaking.This result reinforces its good adaptation to the double-pruning system in a subtropical climate, which favors sugar synthesis [

37,

38].

‘Pinot Noir’ and ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ also showed consistent increases in SS content, reaching ideal levels for wines with balanced acidity and alcohol content. As noted by [

39], although °Brix is not a direct measurement of sugars, its increase directly reflects the physiological maturity of the grape and the quality of the must.

High SS values are directly related to the sensory profile and complexity of wines, as they influence the synthesis of phenolic compounds, aromatic precursors, and organic acids [

40,

41].

According to Brazilian regulations, wine grapes must reach 18–21 °Brix for optimal harvest [

42]. All cultivars in this study achieved values within this range, indicating appropriate technological maturity. ‘Tannat’, in particular, stood out with 23.4 °Brix at 128 DAP (

Figure 4), demonstrating excellent sugar accumulation and strong potential for producing structured wines.

According to [

37], monitoring the progression of berry ripening through variables such as soluble solids and titratable acidity is essential to characterize the chemical composition up to the point of physiological maturity. The primary criterion for determining the optimal harvest time is sugar content, measured in degrees Brix, which represents the total soluble solids—approximately 90% of which are sugars [

38].

The decision on the harvest date is one of the most critical for grape growers, as it involves factors beyond physicochemical parameters, such as flavor, berry and seed integrity, sanitary status, and the intended wine style. Currently, many producers also incorporate sensory evaluations of aroma and taste alongside routine laboratory measurements.

The cultivars ‘Tannat’, ‘Pinot Noir’, and ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ showed a quadratic increase in soluble solids over days after pruning, reflecting efficient sugar accumulation and favorable SS/TA ratios, which contribute to enological balance. Similar patterns were reported by [

43] and [

44]. For red wine production, [

45] recommend a minimum of 21 °Brix. Although °Brix is an indirect measure of sugars—since it also includes vitamins, phenolics, pectins, and organic acids [

39]—sugars still account for up to 90% of the total soluble solids.

Harvesting for fine red wines should be performed at the peak of both technological and phenolic ripeness, with soluble solids ranging from 21 to 26 °Brix and titratable acidity between 5 and 6.5 g L⁻¹ [

46,

47]. °Brix is also critical for estimating potential alcohol content, as higher values indicate greater fermentable sugar levels [

48].

Harvest was performed when soluble solids and titratable acidity values stabilized between two consecutive samplings, as described by [

37]. The cultivars ‘Tannat’, ‘Pinot Noir’, and ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ reached satisfactory SS levels, with ‘Tannat’ standing out by reaching 23.4 °Brix at 128 DAP, indicating high potential for producing wines with greater alcohol content and complexity (

Figure 4).

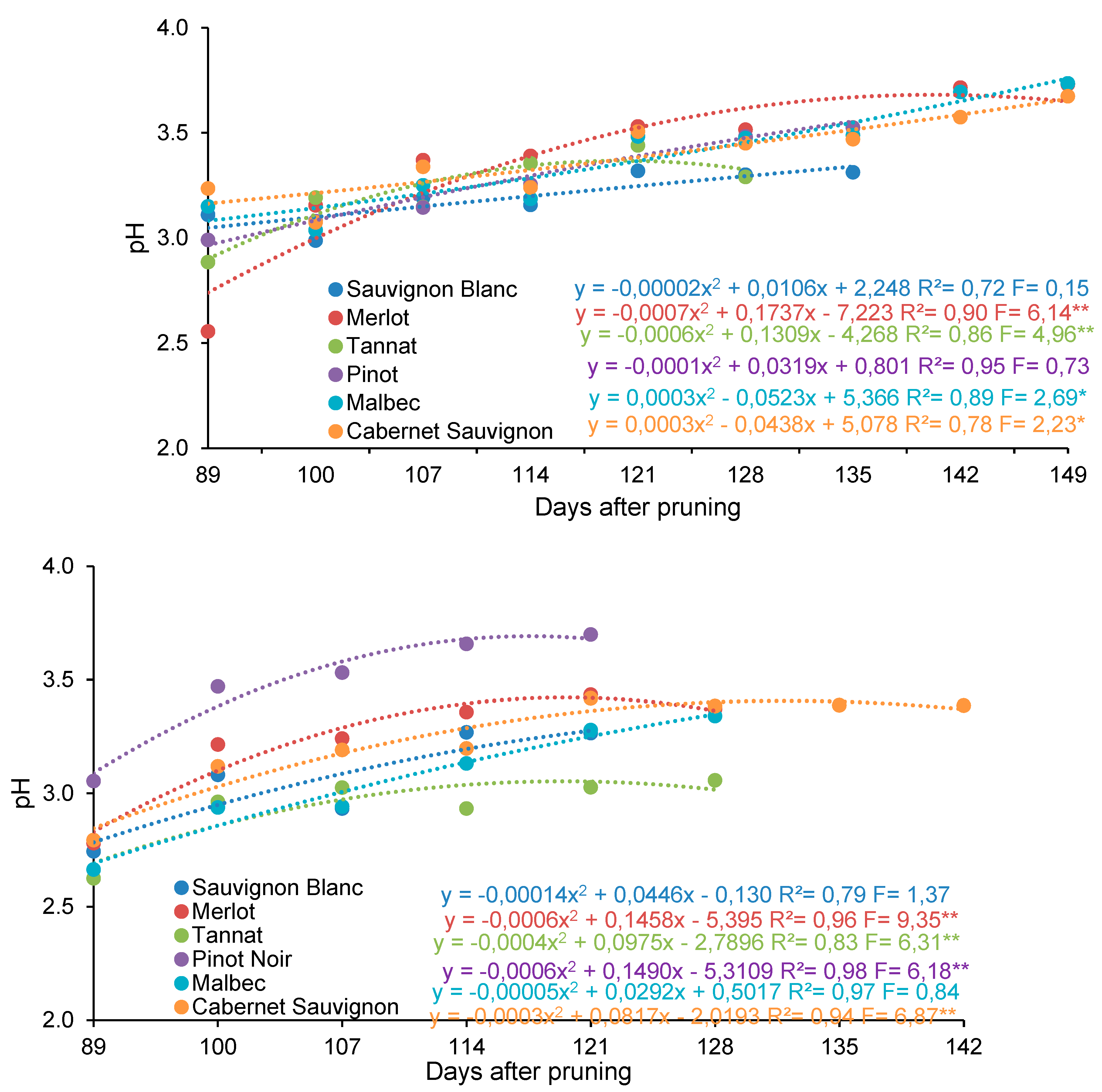

3.8. pH

The analysis of pH evolution throughout the 2023 and 2024 production cycles revealed significant differences among cultivars. Statistical models fitted to the data indicated a linear trend for ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ and ‘Pinot Noir’, and a quadratic trend for ‘Tannat’, ‘Malbec’, ‘Merlot’, and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, reflecting distinct ripening dynamics.

In the 2023 cycle, pH values remained relatively stable, with ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ standing out for their consistency. ‘Tannat’ exhibited a progressive increase in pH, indicating advanced ripening, while ‘Pinot Noir’ remained close to levels considered ideal for winemaking.

In 2024, differences among cultivars became more pronounced. ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ showed a greater increase in pH compared to the previous year, reflecting higher accumulation of compounds associated with maturity. ‘Merlot’ and ‘Malbec’ also exhibited elevated pH values, while ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ maintained similar behavior to that observed in the previous cycle, demonstrating good consistency.

Quadratic pH behavior peaked at 128 days after pruning (DAP), ranging from 3.2 (‘Tannat’) to 3.7 (‘Malbec’). ‘Merlot’ recorded the highest pH value at the end of ripening (3.72), indicating an advanced stage of maturity. The increase in pH, together with the reduction in titratable acidity, suggests optimal technological ripening, favoring wines with a smoother and more balanced sensory profile [

39].

pH has a direct influence on wine quality, affecting microbial stability, color, and sensory characteristics. [

6] reported that wines produced in southeastern Brazil from cultivars such as ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, ‘Malbec’, and ‘Merlot’ usually present pH values between 3.2 and 3.5. Values between 3.2 and 3.4 are considered ideal, as they are associated with anthocyanin stability and color intensity [

49].

During ripening, acidity reduction is mainly due to the degradation of malic acid via cellular respiration, which leads to an increase in pH [

50,

51]. Thus, double-pruning management under subtropical conditions proved effective in achieving pH levels suitable for quality wine production, ensuring a balance between freshness, acidity, and stability.

The pH is an indicator directly related to berry acidity and showed significant variation among the evaluated cultivars, reaching its maximum at 128 days after pruning (DAP). Values ranged from 3.2 for ‘Tannat’ to 3.7 for ‘Malbec’ (

Figure 5).

The evolution of pH throughout the ripening cycle provides relevant information regarding the degree of maturation and the acid–base characteristics of the must, being a decisive parameter for wine quality. pH affects flavor, microbial stability, and wine color, directly influencing the sensory profile [

39].

Among the cultivars, ‘Merlot’ showed the greatest variation, reaching 3.72 at 142 DAP, indicating a sharp decrease in acidity and a more advanced stage of ripening. Elevated pH values are associated with lower perceived acidity, favoring wines with a smoother mouthfeel.

According to [

6], wines produced in southeastern Brazil from red cultivars such as ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, ‘Malbec’, ‘Merlot’, ‘Pinot Noir’, and the white ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ generally present pH values ranging from 3.2 to 3.5, which supports the findings of the present study.

[

52] reported that pH tends to increase linearly during ripening, whereas total acidity decreases exponentially, mainly due to malic acid degradation. In environments with higher water availability, pH tends to be lower for a given level of acidity, highlighting the influence of environmental conditions on grape chemical composition.

3.9. Titratable Acidity (TA)

Titratable acidity (TA), expressed as tartaric acid equivalents, showed a quadratic decline throughout the ripening process in all cultivars. The highest acidity values were observed in ‘Pinot Noir’ and ‘Tannat’, which stood out compared to the other cultivars (

Figure 6).

This reduction in TA during ripening is essential for achieving a balanced wine taste. High acidity levels can result in wines with a more astringent mouthfeel, while controlled acidity contributes to freshness and sensory stability.

Cooler temperatures during the production cycle help preserve berry acidity, which in turn favors the retention of aroma compounds and enhances wine liveliness, as reported by [

53].

According to Brazilian regulations, acceptable acidity levels for fine wines range from 40 to 130 meq L⁻¹, with the ideal interval being between 55 and 130 meq L⁻¹ [

42]. The cultivars ‘Pinot Noir’ and ‘Tannat’ remained within this range, ensuring enological quality and an appropriate structure for wines with greater aging potential.

Titratable acidity (TA), expressed as tartaric acid equivalents, showed a declining trend during ripening across all evaluated cultivars, with a more pronounced reduction during the final stages of the cycle. In contrast, soluble solids content increased as ripening progressed due to sugar accumulation. This inverse relationship between SS and TA was consistent across both production cycles (

Figure 6).

The cultivars ‘Pinot Noir’ and ‘Tannat’ maintained the highest acidity levels throughout the period, reflecting their genetic characteristics and greater potential for producing structured wines with aging capacity.

The combined evaluation of these variables is essential for determining the optimal harvest point, as technological maturity — necessary for fine wine production — is achieved when physicochemical parameters are balanced [

54].

The acidity values observed are in accordance with Brazilian regulations for fine wines, which stipulate acceptable limits between 40 and 130 meq L⁻¹, with the ideal range between 55 and 130 meq L⁻¹ [

42]. The high acidity recorded in some cultivars may be attributed to cooler temperatures in high-altitude regions, which slow the degradation of organic acids such as malic acid [

53].

Previous studies, such as that of [

55], reported similar trends for the cultivar ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ in high-altitude regions of Brazil, reinforcing the present findings.

Several factors contribute to the reduction in TA, including physiological, genetic, and environmental variables [

56,

57,

58]. The decline in acidity is mainly attributed to the respiratory degradation of malic acid, dilution resulting from berry growth, and the salt formation of organic acids [

59].

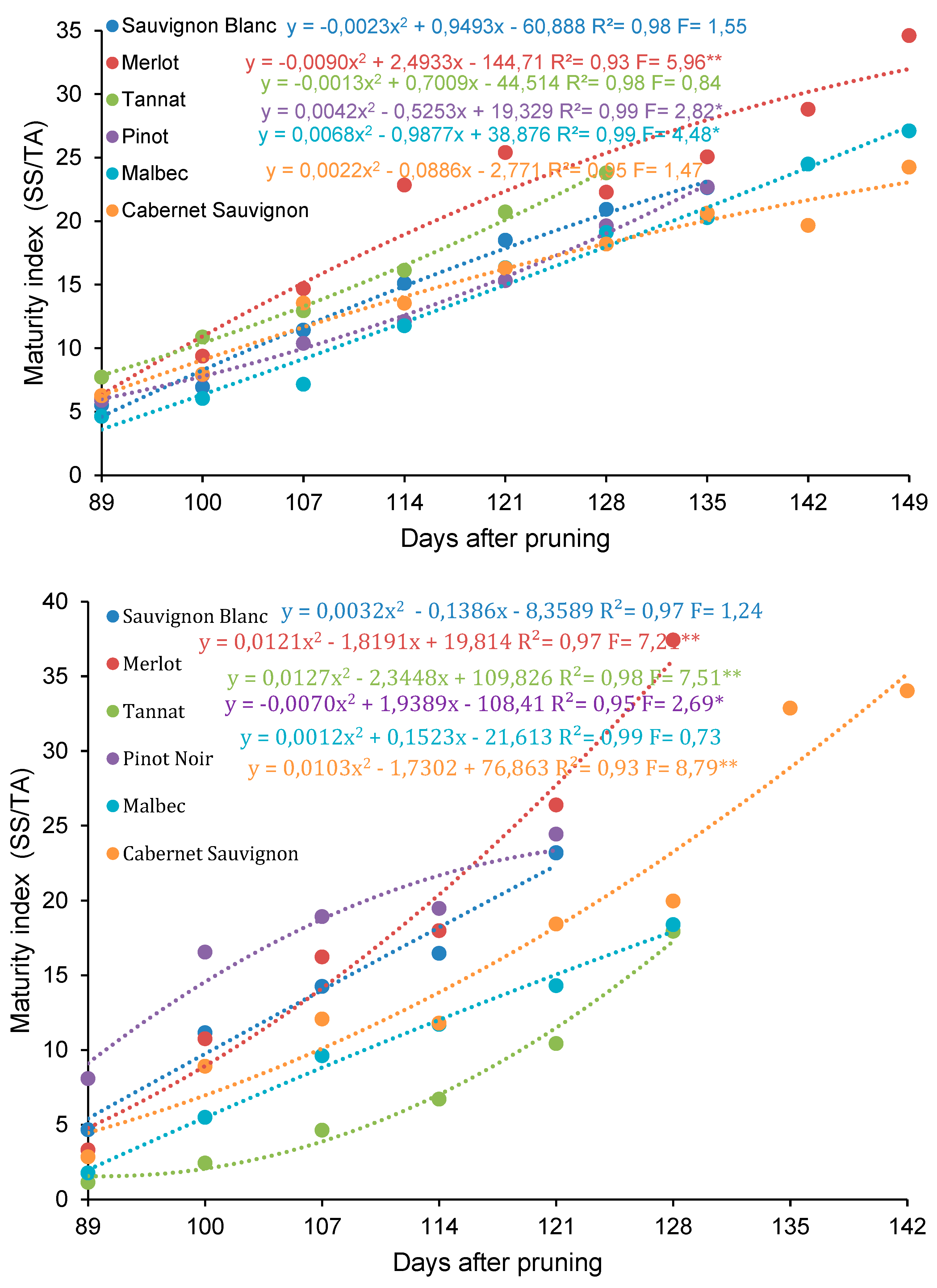

3.10. Maturity Index (SS/TA)

The maturity index (MI), calculated as the ratio between soluble solids content and titratable acidity (SS/TA), showed significant variation among cultivars, reaching values of 20.6 for ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and 28.8 for ‘Merlot’ at 142 days after pruning.

This indicator is widely used to assess the balance between sugar and acidity and is fundamental in defining the wine style to be produced. According to [

60], determining the ideal harvest time involves integrating technological (SS/TA), aromatic, and phenolic parameters to maximize enological potential.

The highest MI values observed in ‘Merlot’ indicate a favorable balance between sugars and acidity, supporting the production of wines with a smoother and rounder profile. In contrast, ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ presented a lower MI, a feature that may impart greater freshness and structure to the wine—desirable attributes for age-worthy red wines.

According to [

59], the ratio between soluble solids and titratable acidity (SS/TA) is widely used as an indicator of grape ripeness and enological quality. However, this index should be interpreted with caution, as the increase in SS does not always occur in inverse proportion to the reduction in TA. Nonetheless, the SS/TA ratio can serve as a reliable indicator of the sugar–acid balance for a given cultivar and region, especially when compared to reference vintages with established enological benchmarks.

In this study, maturity index values at 142 days after pruning ranged from 20.6 (‘Cabernet Sauvignon’) to 28.8 (‘Merlot’) (

Figure 7), highlighting significant differences among cultivars regarding the ideal harvest balance point.

3.11. Biochemical Composition and Antioxidant Potential of Grapes

The biochemical characterization of grapes—including total phenolics, flavonoids, anthocyanins, and antioxidant activity—is essential for determining wine sensory quality, stability, and aging potential.

The cultivars ‘Merlot’ and ‘Tannat’ exhibited the highest contents of total phenolics and flavonoids in grape must (

Table 4), indicating a higher antioxidant potential and, consequently, greater aging capacity and complexity. Phenolic compounds such as anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins are products of the grapevine's secondary metabolism and are directly associated with the color, body, bitterness, and astringency of red wines, particularly under water deficit conditions [

61].

The double-pruning technique promotes ripening under ideal climatic conditions, enhancing the accumulation of polyphenols and antioxidants, which improves both the sensory and enological quality of wines [

21]. This not only adds value to the final product but also enhances the health benefits associated with moderate wine consumption.

The ‘Merlot’ cultivar, with the highest contents of phenolics and flavonoids, is highly promising for the production of age-worthy wines due to its oxidative stability and aromatic persistence. In contrast, ‘Sauvignon Blanc’, with lower levels of these compounds, is better suited for fresh, early-consumption wines. The high anthocyanin content observed in ‘Malbec’ and ‘Merlot’ contributes to the intense coloration of wines, a desirable trait in more robust products (

Table 4).

In red wines, phenolic compound concentrations typically range from 1,000 to 4,000 mg L⁻¹, while in white wines they range from 200 to 300 mg L⁻¹ [

62]. The color of red wines is determined by multiple factors, including pre-fermentation conditions. The interaction between tannins and anthocyanins—especially malvidin-3-O-glucoside, the most abundant pigment in red grapes—plays a key role in defining color intensity and stability [

63].

Antioxidant activity, assessed by DPPH and FRAP assays, confirmed the superior performance of ‘Merlot’ and ‘Tannat’ in terms of phenolic stability and suitability for producing complex wines.

Interestingly, ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ and ‘Pinot Noir’ also showed high antioxidant activity regardless of the method used, with ‘Pinot Noir’ standing out in the DPPH assay. Despite having lower total phenolic content, these cultivars demonstrated excellent antioxidant performance, with similar average values.

It is worth noting that the methods employed yielded distinct sensitivities: the DPPH assay proved more responsive to the presence of antioxidant compounds than the FRAP method. Among all samples, ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ recorded the highest antioxidant potential, with performance comparable to red cultivars, despite its lower anthocyanin content—compounds that are exclusive to red grapes.

The average antioxidant activity measured by DPPH across all cultivars was 11.6, underscoring the suitability of the evaluated grapes for high-quality wine production. The results demonstrate that, beyond their enological potential, these cultivars represent a viable and technically distinct alternative for sustainable wine production in subtropical regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.A.T., C.R.M., and G.E.P.; Methodology: M.A.T., C.R.M., C.A.P.C.S., J.B.O., R.F., M.S.S. and H.S.A.M..; Investigation:; M.A.T., C.R.M., C.A.P.C.S., J.B.O., M.S.S., S.N.S.B., and F.J.D.N. Writing – Original Draft: M.A.T., C.R.M., F.J.D.N. and S.L. Writing – Review and Editing: M.A.T., C.R.M., G.E.P., J.B.O., F.J.D.N., S.L., P.V.S.; Tables and figures: M.A.T., C.R.M., M.S.S. and C.A.P.C.S. and F.J.D.N.; Supervision: M.A.T., G.E.P., S.L. and R.F.; Final approval: M.A.T., C.R.M., G.E.P., S.L., M.S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Annual climatic data for maximum, minimum, and mean temperatures and accumulated rainfall (a); and climatic data after the onset of ripening, including maximum, minimum, and mean temperatures and accumulated precipitation (b), during the 2023 and 2024 growing seasons in Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo, Brazil.

Figure 1.

Annual climatic data for maximum, minimum, and mean temperatures and accumulated rainfall (a); and climatic data after the onset of ripening, including maximum, minimum, and mean temperatures and accumulated precipitation (b), during the 2023 and 2024 growing seasons in Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo, Brazil.

Figure 4.

Evolution of soluble solids content (°Brix) in the must of wine grapes as a function of days after pruning, in grapevines managed under the double-pruning system. Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo, Brazil.

Figure 4.

Evolution of soluble solids content (°Brix) in the must of wine grapes as a function of days after pruning, in grapevines managed under the double-pruning system. Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo, Brazil.

Figure 5.

Evolution of must pH in wine grapes as a function of days after pruning in grapevines managed under the double-pruning system. Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo, Brazil.

Figure 5.

Evolution of must pH in wine grapes as a function of days after pruning in grapevines managed under the double-pruning system. Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo, Brazil.

Figure 6.

Evolution of titratable acidity in the must of wine grapes as a function of days after pruning in grapevines managed under the double-pruning system. Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo, Brazil.

Figure 6.

Evolution of titratable acidity in the must of wine grapes as a function of days after pruning in grapevines managed under the double-pruning system. Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo, Brazil.

Figure 7.

Evolution of the maturity index in the must of wine grapes as a function of days after pruning in grapevines managed under the double-pruning system. Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo, Brazil.

Figure 7.

Evolution of the maturity index in the must of wine grapes as a function of days after pruning in grapevines managed under the double-pruning system. Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo, Brazil.

Table 1.

Duration of phenological stages (days after pruning) of the grape cultivars ‘Sauvignon Blanc’, ‘Merlot’, ‘Pinot Noir’, ‘Tannat’, ‘Malbec’, and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ during the 2023 and 2024 production cycles under subtropical conditions in São Paulo, Brazil.

Table 1.

Duration of phenological stages (days after pruning) of the grape cultivars ‘Sauvignon Blanc’, ‘Merlot’, ‘Pinot Noir’, ‘Tannat’, ‘Malbec’, and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ during the 2023 and 2024 production cycles under subtropical conditions in São Paulo, Brazil.

| Cultivar/Production Cycle |

Budburst |

Full flowering |

Fruit set |

Beginning of ripening |

Harvest |

Growing degree days |

| I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

| Sauvignon Blanc |

12.3 ± 0.71 ABb* |

13.4 ± 0.52 ABa |

44.3 ± 2.12 Ca |

31.6 ± 7.44 Ab |

47.1 ± 2.59 Ca |

34.8 ± 1.49 Bb |

87.9 ± 0.64 Ba |

85.8 ± 4.27 Ca |

130.9 ± 0.00 Ca |

121.0 ± 0.00 Cb |

1700.3 ± 5.89 Ca |

1122.7 ± 14.3 Db |

| Merlot |

11.9 ± 0.83 Ba |

12.5 ± 0.76 BCa |

48.3 ± 4.50 Ba |

32.1 ± 0.83 Ab |

53.5 ± 3.25 Ba |

35.8 ± 2.12 ABb |

93.8 ± 3.33 Aa |

90.6 ± 2.07 Bb |

171.0 ± 0.00 Aa |

128.0 ± 0.00 Bb |

1758.9 ± 1.55 Ba |

1218.0 ± 10.1 Bb |

| Tannat |

13.0 ± 0.53 Aa |

13.5 ± 0.53 ABa |

53.9 ± 6.20 Aa |

35.0 ± 1.51 Ab |

58.4 ± 5.53 Aa |

39.0 ± 0.76 Ab |

97.0 ± 3.33 Aa |

95.3 ± 1.04 Aa |

148.0 ± 0.00 Ba |

128.0 ± 0.00 Bb |

1785.5 ± 2.25 Aa |

1204.7 ± 8.45 Cb |

| Pinot Noir |

12.8 ± 1.04 Aba |

13.5 ± 1.07 ABa |

45.3 ± 3.45 BCa |

32.9 ± 0.83 Ab |

48.1 ± 3.68 Ca |

37.0 ± 1.69 ABb |

88.3 ± 0.71 Bb |

90.8 ± 4.50 Ba |

130.0 ± 0.00 Da |

121.0 ± 0.00 Cb |

1702.8 ± 4.39 Ca |

1119.9 ± 18.4 Db |

| Malbec |

11.8 ± 0.89 Bb |

13.6 ± 0.52 Aa |

43.3 ± 1.83 Ca |

32.0 ± 0.76 Ab |

45.9 ± 1.64 Ca |

35.6 ± 1.77 ABb |

94.7 ± 1.39 Aa |

93.9 ± 2.03 ABa |

171.0 ± 0.00 Aa |

128.0 ± 0.00 Bb |

1769.8 ± 0.49 Ba |

1202.7 ± 8.18 Cb |

| Cabernet Sauvignon |

12.6 ± 1.06 Aba |

12.3 ± 0.46 Ca |

43.9 ± 1.55 Ca |

32.0 ± 0.76 Ab |

46.6 ± 1.77 Ca |

35.8 ± 1.58 ABb |

94.0 ± 0.00 Aa |

92.8 ± 2.66 ABa |

129.0 ± 0.00 Eb |

142.0 ± 0.00 Aa |

1760.3 ± 0.96 Ba |

1377.8 ± 5.46 Ab |

| Média |

12.7 |

39.5 |

43.1 |

92.1 |

137.3 |

1,476.90 |

| CV 1 (%) |

5.95 |

7.06 |

6.17 |

2.54 |

2.93 |

0.56 |

| CV 2 (%) |

6.11 |

6.47 |

5.84 |

2.82 |

2.01 |

0.62 |

Table 2.

Physical characteristics of clusters, berries, and rachis of wine grape cultivars grown under double-pruning management in a subtropical climate during the 2023 (I) and 2024 (II) growing seasons in São Paulo, Brazil.

Table 2.

Physical characteristics of clusters, berries, and rachis of wine grape cultivars grown under double-pruning management in a subtropical climate during the 2023 (I) and 2024 (II) growing seasons in São Paulo, Brazil.

| Cultivar/ |

FWC |

CL |

CW |

CL/CW |

FWB |

BL |

BW |

BL/BW |

NBC |

FWR |

|

| Production Cycle |

I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

| Sauvignon Blanc |

87.9 ± 16.9 bcA* |

84.5 ± 4.05 BCa |

7.90 ± 1.07 Ba |

8.29 ± 0.54 Ca |

4.67 ± 0.37 BCb |

6.75 ± 0.61 BCa |

1.69 ± 0.16 Bca |

1.24 ± 0.12 BCb |

1.41 ± 0.10 Ba |

1.36 ± 0.10 Ca |

1.45 ± 0.05 ABa |

1.42 ± 0.03 BCa |

1.28 ± 0.03 Ba |

1.27 ± 0.03 Ca |

1.13 ± 0.02 ABa |

1.11 ± 0.03 Aba |

59.3 ± 12.3 Ba |

58.8 ± 5.61 Ba |

4.27 ± 0.78 Ca |

5.00 ± 0.59 Ba |

| Merlot |

56.6 ± 8.47 Da |

68.0 ± 10.9 CDa |

8.25 ± 0.83 Bb |

10.3 ± 0.82 Ba |

5.25 ± 0.63 BCb |

7.00 ± 0.85 Ba |

1.58 ± 0.12 Ca |

1.49 ± 0.08 Aba |

1.09 ± 0.04 Cb |

1.27 ± 0.05 CDa |

1.14 ± 0.14 Cb |

1.31 ± 0.19 Ca |

1.10 ± 0.03 Db |

1.35 ± 0.03 Ba |

1.03 ± 0.14 Ba |

0.98 ± 0.15 Ba |

49.4 ± 8.29 Ba |

50.8 ± 7.08 ABa |

3.01 ± 0.48 Da |

3.50 ± 0.69 Ca |

| Tannat |

125.4 ± 20.4 Ab |

143.0 ± 19.8 Aa |

10.3 ± 1.98 Ab |

15.3 ± 1.98 Aa |

14.1 ± 1.17 Ab |

18.1 ± 1.82 Aa |

0.72 ± 0.10 Da |

0.84 ± 0.04 Da |

1.41 ± 0.12 Bb |

1.64 ± 0.15 Ba |

1.37 ± 0.04 Bb |

1.57± 0.06 Aba |

1.26 ± 0.03 BCb |

1.39 ± 0.08 Ba |

1.09 ± 0.02 ABa |

1.13 ± 0.04 Aa |

83.2 ± 8.75 Aa |

83.0 ± 8.61 Aa |

7.38 ± 0.54 Ab |

8.20 ± 0.36 Aa |

| Pinot Noir |

66.1 ± 10.7 CDa |

46.3 ± 8.16 Db |

6.88 ± 0.74 Ba |

6.18 ± 0.59 Da |

4.22 ± 0.74 Cb |

5.52 ± 0.33 CDa |

1.67 ± 0.27 BCa |

1.12 ± 0.11 Cb |

1.09 ± 0.14 Ca |

1.21 ± 0.14 CDa |

1.40 ± 0.20 ABa |

1.30 ± 0.03 Cb |

1.19 ± 0.03 Ca |

1.19 ± 0.04 Da |

1.18 ± 0.19 Aa |

1.09 ± 0.02 Aba |

58.3 ± 8.88 Ba |

26.9 ± 7.60 Db |

2.63 ± 0.80 Da |

2.21 ± 0.60 Da |

| Malbec |

137.2 ± 28.6 Aa |

97.0 ± 22.8 Bb |

10.5 ± 1.21 Aa |

11.3 ± 1.34 Ba |

5.53 ± 0.52 Bb |

7.65 ± 0.83 Ba |

1.90 ± 0.21 Ba |

1.48 ± 0.17 ABb |

2.11 ± 0.18 Aa |

2.13 ± 0.11 Aa |

1.55 ± 0.06 Ab |

1.67 ± 0.05 Aa |

1.45 ± 0.05 Ab |

1.50 ± 0.03 Aa |

1.07 ± 0.03 ABa |

1.12 ± 0.02 Aba |

62.0 ± 11.4 Ba |

43.6 ± 8.88 CDb |

6.19 ± 1.54 Ba |

3.75 ± 0.76 Cb |

| Cabernet Sauvignon |

99.9 ± 11.0 Ba |

56.0 ±11.3 Db |

10.2 ± 1.10 Aa |

7.61 ± 0.88 CDb |

4.14 ± 0.20 Ca |

4.70 ± 0.70 Da |

2.48 ± 0.27 Aa |

1.63 ± 0.05 Ab |

1.26 ± 0.09 BCa |

1.10 ± 0.03 Db |

1.32± 0.02 Ba |

1.30 ± 0.01 Ca |

1.22 ± 0.02 BCa |

1.19 ± 0.00 Da |

1.07 ± 0.02 ABa |

1.09 ± 0.00 ABa |

75.7 ± 6.27 Aa |

47.9 ± 8.13 BCDb |

4.60 ± 0.49 Ca |

2.97 ± 0.80 CDb |

| CV (%) |

21.5 |

16 |

17.1 |

8.86 |

14.6 |

9.15 |

13.1 |

10.2 |

9.38 |

7.2 |

8.92 |

3.75 |

2.53 |

|

16.6 |

12.9 |

16.7 |

19.1 |

| Mean |

88.9 |

9.41 |

7.31 |

1.49 |

1.42 |

1.40 |

1.28 |

1.10 |

50.1 |

4.47 |

|

Table 3.

Yield, productivity, and number of clusters per plant of wine grape cultivars grown under double-pruning management in a subtropical climate during the 2023 (I) and 2024 (II) growing seasons in Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo, Brazil.

Table 3.

Yield, productivity, and number of clusters per plant of wine grape cultivars grown under double-pruning management in a subtropical climate during the 2023 (I) and 2024 (II) growing seasons in Mineiros do Tietê, São Paulo, Brazil.

| Cultivar/Production Cycle |

Yeld |

Productivity |

Number of clusters per plant |

| (kg pl-1) |

(t ha-1) |

(un) |

| I |

II |

I |

II |

I |

II |

| Sauvignon Blanc |

2,13 ± 0,29 Ab* |

2,75 ± 0,15 Bb |

7,59 ± 1,02 Ab |

9,82 ± 0,53 Ba |

9,25 ± 5,09 Ab |

11,6 ± 5,18 Aba |

| Tannat |

0,88 ± 0,24 Bb |

1,09 ± 0,01 Ca |

3,12 ± 0,85 Bb |

3,89 ± 0,05 Ca |

5,63 ± 1,41 BCb |

7,38 ± 1,06 Ca |

| Pinot Noir |

0,70 ± 0,09 BCb |

0,89 ± 0,01 CDa |

2,50 ± 0,33 BCb |

3,18 ± 0,04 CDa |

4,88 ± 1,36 Cb |

7,63 ± 1,19 Ca |

| Malbec |

0,50 ± 0,13 Cb |

0,78 ± 0,03 Da |

1,79 ± 0,48 Cb |

2,77 ± 0,11 Da |

6,37 ± 1,41 BCb |

10,0 ± 1,20 Ba |

| Cabernet Sauvignon |

2,13 ± 0,28 Ab |

3,03 ± 0,06 Aa |

7,59 ± 0,99 Ab |

10,8 ± 0,20 Aa |

7,38 ± 1,06 Bb |

11,8 ± 0,99 Aa |

| CV(%) |

11,6 |

10,6 |

11,6 |

10,7 |

39,5 |

5,20 |

| Mean |

1,49 |

5,30 |

8,20 |

Table 4.

Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of wine grape cultivars grown under double-pruning management in a subtropical climate during the 2024 growing season, São Paulo, Brazil.

Table 4.

Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of wine grape cultivars grown under double-pruning management in a subtropical climate during the 2024 growing season, São Paulo, Brazil.

| Cultivars |

Bioactive compounds and antioxidant |

| Phenols |

Flavonoids |

Anthocyanins |

DPPH |

FRAP |

| (mg 100 g-1) |

(µg Trolox g-1) |

(mmol FeSO4 g-1) |

| Sauvignon Blanc |

101.3 c* |

10.1 c |

18.7 cd |

12.2 a |

3.49 a |

| Merlot |

234.9 a |

15.3 a |

76.1 a |

11.1 cd |

3.34 cd |

| Tannat |

216.6 a |

14.7 a |

64.6 ba |

11.6 bc |

3.41 bc |

| Pinot Noir |

151.2 b |

12.3 b |

33.8 bc |

11.7 ab |

3.42 ab |

| Malbec |

209.9 a |

14.5 a |

77.7 a |

11.1 d |

3.33 d |

| Cabernet Sauvignon |

206.3 a |

14.4 a |

14.4 d |

11.6 bcd |

3.41 bcd |

| DMS |

1.22 |

2.07 |

111.5 |

0.55 |

1.91 |

| CV (%) |

8.65 |

27.9 |

22.4 |

2.39 |

3.49 |

| Mean |

186.69 |

13.5 |

47.5 |

11.6 |

3.40 |