Submitted:

04 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bucur, G.M.; Dejeu, L. Phenological and some eno-carpological traits of thirteen new Romanian grapevine varieties for white wine (Vitis Vinifera L.) in the context of climate change. Scientific Papers. Series B. Horticulture. 2024, 68 (1), 254-263. https://horticulturejournal.usamv.ro/pdf/2024/issue_1/Art32.pdf.

- Antoce, A.O.; Călugăru, L.L. Evolution of grapevine surfaces in Romania after accession to European Union - period 2007-2016. 40th World Congress of Vine and Wine, BIO Web of Conf. 2017, 9, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Tangolar, S.; Temel, N.; Torun, H.; Tangolar, S.; Karaman, Y.; Tursun, N.; Torun, A. A. Impact of organic and non-organic mulching on grape yield, quality and ecophysiological traits under irrigated and nonirrigated conditions. OENO One. 2025, 59 (1). [CrossRef]

- Carrera, L.; Fernández-González, M.; Aira, M. J.; Espinosa, K.C.S.; Otero, R.P.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F. J. Airborne Plasmopara viticola Sporangia: A Study of Vineyards in Two Bioclimatic Regions of Northwestern Spain. Horticulturae. 2025, 11 (3), 228. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, B.I. Phenology and Terroir Heard Through the Grapevine. In Phenology: An Integrative Environmental Science, 3nd ed.; Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024; pp. 573-593. [CrossRef]

- Costea, D. C.; Căpruciu, R. The influence of environmental resources specific to the cultivation year over the grapevine growth and yield. Annals of the University of Craiova - Agriculture Montanology Cadastre Series. 2022, 52 (1), 95-100. [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, L.; Nagy, R. Assessment of historical and future changes in temperature indices for winegrape suitability in Hungarian wine regions (1971-2100). Frontiers in Plant Science. 2025, 16, 1481431. [CrossRef]

- Tiefenbacher, J.P.; Townsend, C. The Semiofoodscape of Wine: The Changing Global Landscape of Wine Culture and the Language of Making, Selling and Drinking Wine. In Handbook of the Changing World Language Map; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1-44.

- Dinu, M.D., Mazilu, I.E.; Cosmulescu, S. Influence of climatic factors on the phenology of chokeberry cultivars planted in the Pedoclimatic conditions of southern Romania. Sustainability. 2022, 14 (9), 4991. [CrossRef]

- Parra, A.S.S.; Gascueña, J.M.; Alonso, G.L.; Tarancón, C.C.; Morales, A.M.; Vozmediano, J.L.C. Exploring intra-specific variability as an adaptive strategy to climate change: Response of 21 grapevine cultivars grown under drought conditions. OENO One, 2024, 58 (3). [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska, D.; Olewnicki, D.; Stangierska-Mazurkiewicz, D.; Tyminski, M., Latocha, P. Impact of climate change on the development of viticulture in central Poland: autoregression modeling SAT indicator. Agriculture. 2024, 14 (5), 748. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.A.; Petrone, R.M.; Valentini, R.; Macrae, M.L.; Reynolds, A. Assessing the influence of climate controls on grapevine biophysical responses: a review of Ontario viticulture in a changing climate. Canadian Journal of Plant Science. 2024, 104 (5), 394-409. [CrossRef]

- Colibaba, L.C.; Bosoi, I.; Pușcalău, M.; Bodale, I.; Luchian, C. Rotaru, L.; Cotea, V.V. Climatic projections vs. grapevine phenology: A regional case study. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca, 2024, 52 (1), 13381-13381. [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Darriet, P. The impact of climate change on viticulture and wine quality. J. Wine Econ. 2016, 11, 150-167. [CrossRef]

- Galal, H.; Ghoneem, G.M.; Khalil, R.; Yusuf, M.; Allam, A.; Abou Elyazid, D.M. Plastic Covering Accelerates Phenological Stages and Causes Abiotic Stress in Table Grapes in Egypt. Journal of Plant Production, 2024, 15 (10), 629-636. [CrossRef]

- Cichi, D.D.; Cichi, M.; Gheorghiu, N. Thermal regime during cold acclimation and dormant season of grapevines in context of climate changes-Hills of Craiova vineyard (Romania). Annals of the University of Craiova-Agriculture, Montanology, Cadastre Series. 2021, 51 (1), 50-59.

- Mărăcineanu, C.; Giugea, N.; Muntean, L.; Căpruciu, R. Analyses of the influence of crop load on biological and productive characteristics of some table grape varieties grown in the Severin vineyard. Scientific Papers. Series B. Horticulture. 2022, 66 (1). https://horticulturejournal.usamv.ro/pdf/2022/issue_1/Art47.pdf.

- Monteiro, A.; Pereira, S.; Bernardo, S.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Dinis, L.T. Biochemical analysis of three red grapevine varieties during three phenological periods grown under Mediterranean climate conditions. Plant Biology. 2024, 26 (5), 855-867. [CrossRef]

- Gerbi, V.; De Paolis, C. The effects of climate change on wine composition and winemaking processes. Italian Journal of Food Science, 2025, 37 (1), 246-260.

- Baltazar, M.; Castro, I.; Gonçalves, B. Adaptation to Climate Change in Viticulture: The Role of Varietal Selection-A Review. Plants. 2025, 14 (1), 104. [CrossRef]

- Llanaj, C.; McGregor, G. Climate change, grape phenology, and frost risk in Southeast England. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research. 2022, (1), 9835317. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes de Oliveira, A.; Piga, G.K.; Najoui, S.; Becca, G.; Marceddu, S.; Rigoldi, M.P.; Nieddu, G. UV light and adaptive divergence of leaf physiology, anatomy, and ultrastructure drive heat stress tolerance in genetically distant grapevines. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2024, 15, 1399840. [CrossRef]

- Procino, S.; Miazzi, M.M.; Savino, V.N.; La Notte, P.; Venerito, P.; D’Agostino, N.; Montemurro, C. Genome Scan Analysis for Advancing Knowledge and Conservation Strategies of Primitivo Clones (Vitis vinifera L.). Plants. 2025, 14 (3), 437. [CrossRef]

- Kamila, S.; Widodo, W.D.; Santosa, E.; Suhartanto, M.R. Flowering and fruiting phenology in two varieties of grapes (Vitis vinifera) in tropical regions, Indonesia. Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity. 2024, 25 (11). [CrossRef]

- Rafique, R.; Ahmad, T.; Ahmed, M; Khan, M.A.; Wilkerson, C.J.; Hoogenboom G. Seasonal variability in the effect of temperature on key phenological stages of four table grapes cultivars. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2023, 67, 745-759. [CrossRef]

- Faralli, M.; Martintoni, S.; Giberti, F.D.; Bertamini, M. Dynamic of bud ecodormancy release in Vitis vinifera: Genotypic variation and late frost tolerance traits monitored via chlorophyll fluorescence emission. Scientia Horticulturae. 2024, 331, 113169.

- Santillán, D.; Garrote, L.; Iglesias, A.; Sotes, V. Climate Change Risks and Adaptation: New Indicators for Mediterranean Viticulture. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change. 2020, 25, 881-899. [CrossRef]

- Tramblay, Y.; Koutroulis, A.; Samaniego, L.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Volaire, F.; Boone, A.; Le Page, M.; Llasat, M.C.; Albergel, C.; Burak, S.; Cailleret, M.; Kalin, K.C.; Davi, H.; Dupuy, J.L.; Greve, P.; Grillakis, M.; Hanich, L.; Jarlan, L.; Martin-StPaul, N.; Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Mouillot, F.; D. Pulido-Velazquez, D.; Quintana-Seguí, P.; Renard, D.; Turco, M.; Türkeş, M.; Trigo, R.; Vidal, J.P.; Vilagrosa, A.; Zribi, M.; Polcher. J. Challenges for drought assessment in the Mediterranean region under future climate scenarios. Earth-Science Reviews. 2020, 210,103348. [CrossRef]

- Droulia, F.; Charalampopoulos, I. Future Climate Change Impacts on European Viticulture: A Review on Recent Scientific Advances. Atmosphere. 2021, 12 (4), 495. [CrossRef]

- Grillakis, M. G.; Doupis, G.; Kapetanakis, E.; Goumenaki, E. Future shifts in the phenology of table grapes on Crete under a warming climate. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 2022, 318, 108915. [CrossRef]

- Verdugo-Vásquez, N.; Pañitrur-De la Fuente, C.; Ortega-Farías, S. Model Development to Predict Phenological scale of Table Grapes (cvs. Thompson, Crimson and Superior Seedless and Red Globe) using Growing Degree Days. OENO One. 2017, 51 (3). [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Roldán, F.E.; García-Díaz, A.; Raboso, E.; Crespo, J.; Cabello, F.; Martínez de Toda, F.; Muñoz-Organero, G. Phenological Evaluation of Minority Grape Varieties in the Wine Region of Madrid as a Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change. Horticulturae. 2024, 10 (4). 353. [CrossRef]

- del Río, S.; Álvarez-Esteban, R.; Alonso-Redondo, R.; Álvarez, R.; Rodríguez-Fernández, M.P.; González-Pérez, A.; Penas, A. Applications of bioclimatology to assess effects of climate change on viticultural suitability in the DO León (Spain). Theoretical and Applied Climatology. 2024, 155 (4). 3387-3404. [CrossRef]

- Pourreza, A.; Kamiya, Y.; Peanusaha, S.; Jafarbiglu, H.; Moghimi, A.; Fidelibus, M.W. Nitrogen retrieval in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) canopy by hyperspectral imaging. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 2025, 229, 109717. [CrossRef]

- Chedea, V. S.; Drăgulinescu, A.M.; Tomoiagă, L.L.; Bălăceanu, C.; Iliescu, M.L. Climate change and internet of things technologies-sustainable premises of extending the culture of the Amurg cultivar in Transylvania-a use case for Târnave vineyard. Sustainability. 2021, 13 (15), 8170. [CrossRef]

- Stațiunea Murfatlar. Available online: https://statiuneamurfatlar.ro/vocatia-podgoriei-si-a-statiunii/ (accesed 03/16/2025).

- Borghezan, M.; Villar, L.; Silva, T.; Canton, M.; Guerra, M.; Campos, C. Phenology and Vegetative Growth in a New Production Region of Grapevines: Case Study in São Joaquim, Santa Catarina, Southern Brazil. Open Journal of Ecology. 2014, 4, 321-335. doi: 10.4236/oje.2014.46030.

- García de Cortázar-Atauri, I.; Duchêne, E.; Destrac-Irvine, A.; Barbeau, G.; de Rességuier, L.; Lacombe, T.; Parker A.K.; Saurin N.; van Leeuwen, C. Grapevine phenology in France: from past observations to future evolutions in the context of climate change. OENO One. 2017, 51 (2), 115–126. [CrossRef]

- Verdugo-Vásquez, N.; Acevedo-Opazo, C.; Valdés-Gómez, H.; Araya-Alman, M.; Ingram, B.; de Cortázar-Atauri, I.G.; Tisseyre, B. Spatial variability of phenology in two irrigated grapevine cultivar growing under semi-arid conditions. Precision Agric. 2016, 17, 218–245. [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; Amraoui, M.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Eiras-Dias, J.; Silvestre, J.; Santos, J.A. Examining the relationship between the Enhanced Vegetation Index and grapevine phenology. European Journal of Remote Sensing. 2014, 47 (1), 753–771. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.; Pedroso, V.; Reis, S.; Yang, C.; Santos, Santos J.A. Climate change impacts on phenology and ripening of cv. Touriga Nacional in the Dão Wine Region, Portugal. International Journal of Climatology. 2022, 42, (14). 7117-7132, doi:10.1002/joc.7633, 1097-0088 0899-8418.

- Cameron, W.; Petrie, P.R., Barlow, E.; Howell, K.; Jarvis, C.; Fuentes, S. A comparison of the effect of temperature on grapevine phenology between vineyards. OENO One. 2021, 55 (2), 301-320. [CrossRef]

- Bernáth, S.; Paulen, O.; Šiška, B.; Kusá, Z.; Tóth, F. Influence of Climate Warming on Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) Phenology in Conditions of Central Europe (Slovakia). Plants. 2021, 10, 1020. [CrossRef]

- Teker, T. Effects of temperature rise on grapevine phenology (Vitis vinifera L.): Impacts on early flowering and harvest in the 2024 Growing Season. International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Food Sciences. 2024, 8 (4), 970-979. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, N.A.S.; Leite, A.V.; Castro, C.C. Phenology, reproductive biology and growing degree days of the grapevine ‘Isabel’ (Vitis labrusca, Vitaceae) cultivated in northeastern Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Biology. 2016, 76 (04). http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.05315.

- Rafique, R.; Ahmad, T.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmed, M.; Atak, A. Pheno-physiological responses of grapevine cultivars vary under the influence of growing season temperature – a study from Pothwar region of Pakistan. Acta Hortic. 2024, 1385, 197-204. DOI: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2024.1385.25.

- Rafique R.; Ahmad, T.; Abbasi, N.; Ahmed, M. Modeling phenological responses of table grape cultivars. In Book of abstract Second International Crop Modelling Symposium, Montpellier, France. 2020. https://inria.hal.science/hal-02950242v1.

- Munoz-Organero, G.; Espinosa, F.E.; Cabello, F.; Zamorano, J.P.; Urbanos, M.A.; Puertas, B.; Fernandez-Pastor, M. Phenological study of 53 Spanish minority grape varieties to search for adaptation of vitiviniculture to climate change conditions. Horticulturae. 2022, 8(11), 984. [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, T. Understanding the Influence of Extreme Cold on Grapevine Phenology in South Dakota’s Dormant Season: Implications for Sustainable Viticulture. Applied Fruit Science. 2024, 66, 1019–1026. [CrossRef]

- Ghiglieno, I.; Facciano, L.; Valenti, L.; Amari, F.; Cola, G. Evaluation of the impact of vine pruning periods on grape production and composition: an integrated approach considering different years and cultivars. OENO ONE. 2025, 59. [CrossRef]

- Beleniuc G.V. Viticultura și vinificația de pe Valea Carasu de-a lungul vremurilor. Teză de doctorat. Universitatea din Craiova, 2022.

- Alonso, F.; Chiamolera, F.M.; Hueso, J.J.; González, M.; Cuevas, J. Heat unit requirements of “flame seedless” table grape: a tool to predict its harvest period in protected cultivation. Plants. 2021, 10 (5), 904. [CrossRef]

- Cosmulescu, S.; Laies, M.M.M.; Sărățeanu, V. The Influence of Variety and Climatic Year on the Phenology of Blueberry Grown in the Banat Area, Romania. Agronomy. 2022, 12, 2605. [CrossRef]

| Phenophase | Variety | Mean | SD | CV (%) | Shapiro–Wilk | p-Value of Shapiro–Wilk | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBCH 09 (Bud burst) |

Victoria | 108.750 | 1.997 | 1.836 | 0.944 | 0.284 | 106.000 | 113.000 |

| Cardinal | 109.500 | 1.573 | 1.437 | 0.942 | 0.265 | 107.000 | 113.000 | |

| Muscat Hamburg | 110.100 | 1.021 | 0.927 | 0.790 | < 0.001 | 109.000 | 113.000 | |

| Italia | 113.650 | 1.461 | 1.286 | 0.889 | 0.026 | 110.000 | 117.000 | |

| Afuz-Ali | 111.750 | 2.359 | 2.111 | 0.754 | < 0.001 | 109.000 | 119.000 | |

| BBCH 61 (Beginning of flowering) |

Victoria | 148.600 | 1.789 | 1.204 | 0.937 | 0.212 | 145.000 | 151.000 |

| Cardinal | 149.300 | 3.230 | 2.163 | 0.953 | 0.410 | 144.000 | 155.000 | |

| Muscat Hamburg | 152.200 | 3.443 | 2.262 | 0.920 | 0.098 | 148.000 | 160.000 | |

| Italia | 153.150 | 4.320 | 2.821 | 0.951 | 0.380 | 147.000 | 161.000 | |

| Afuz-Ali | 153.850 | 4.295 | 2.792 | 0.929 | 0.147 | 146.000 | 160.000 | |

| BBCH 81 (Beginning of ripening) |

Victoria | 198.000 | 1.124 | 0.568 | 0.907 | 0.056 | 196.000 | 200.000 |

| Cardinal | 198.100 | 1.294 | 0.653 | 0.917 | 0.088 | 195.000 | 200.000 | |

| Muscat Hamburg | 230.100 | 1.651 | 0.718 | 0.889 | 0.026 | 226.000 | 232.000 | |

| Italia | 233.650 | 2.870 | 1.228 | 0.870 | 0.012 | 229.000 | 241.000 | |

| Afuz-Ali | 232.600 | 3.619 | 1.556 | 0.962 | 0.581 | 226.000 | 242.000 | |

| BBCH 89 (Full maturity) |

Victoria | 253.450 | 4.395 | 1.734 | 0.895 | 0.033 | 245.000 | 259.000 |

| Cardinal | 239.250 | 7.779 | 3.251 | 0.941 | 0.250 | 227.000 | 251.000 | |

| Muscat Hamburg | 261.200 | 5.053 | 1.935 | 0.814 | 0.001 | 245.000 | 269.000 | |

| Italia | 275.450 | 3.620 | 1.314 | 0.894 | 0.032 | 271.000 | 283.000 | |

| Afuz-Ali | 272.900 | 4.315 | 1.581 | 0.876 | 0.015 | 268.000 | 281.000 |

| Phenophase | Year | Mean | SD* | CV (%) | Shapiro–Wilk | p-Value of Shapiro–Wilk | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBCH 09 (Bud burst) |

2000 | 110.800 | 2.280 | 2.058 | 0.961 | 0.814 | 108.000 | 114.000 |

| 2001 | 111.200 | 2.280 | 2.050 | 0.961 | 0.814 | 108.000 | 114.000 | |

| 2002 | 111.200 | 1.643 | 1.478 | 0.779 | 0.054 | 110.000 | 114.000 | |

| 2003 | 112.600 | 3.782 | 3.359 | 0.786 | 0.062 | 110.000 | 119.000 | |

| 2004 | 112.800 | 1.095 | 0.971 | 0.828 | 0.135 | 111.000 | 114.000 | |

| 2005 | 111.800 | 3.114 | 2.785 | 0.885 | 0.332 | 108.000 | 115.000 | |

| 2006 | 111.600 | 2.881 | 2.582 | 0.871 | 0.269 | 109.000 | 116.000 | |

| 2007 | 110.000 | 3.240 | 2.945 | 0.922 | 0.543 | 106.000 | 115.000 | |

| 2008 | 111.800 | 2.950 | 2.639 | 0.688 | 0.007 | 110.000 | 117.000 | |

| 2009 | 111.200 | 1.643 | 1.478 | 0.779 | 0.054 | 110.000 | 114.000 | |

| 2010 | 110.200 | 2.775 | 2.518 | 0.939 | 0.656 | 107.000 | 114.000 | |

| 2011 | 110.400 | 1.673 | 1.515 | 0.881 | 0.314 | 109.000 | 113.000 | |

| 2012 | 112.000 | 1.225 | 1.094 | 0.833 | 0.146 | 111.000 | 114.000 | |

| 2013 | 110.400 | 1.673 | 1.515 | 0.881 | 0.314 | 109.000 | 113.000 | |

| 2014 | 109.800 | 2.387 | 2.174 | 0.974 | 0.899 | 107.000 | 113.000 | |

| 2015 | 110.200 | 2.490 | 2.260 | 0.895 | 0.384 | 108.000 | 114.000 | |

| 2016 | 110.600 | 2.702 | 2.443 | 0.903 | 0.427 | 108.000 | 115.000 | |

| 2017 | 109.000 | 2.000 | 1.835 | 0.905 | 0.440 | 106.000 | 111.000 | |

| 2018 | 108.800 | 2.683 | 2.466 | 0.916 | 0.502 | 106.000 | 113.000 | |

| 2019 | 108.600 | 1.517 | 1.397 | 0.803 | 0.086 | 107.000 | 110.000 | |

| BBCH 61 (Beginning of flowering) |

2000 | 148.400 | 1.817 | 1.224 | 0.867 | 0.254 | 146.000 | 150.000 |

| 2001 | 149.800 | 0.837 | 0.558 | 0.881 | 0.314 | 149.000 | 151.000 | |

| 2002 | 149.000 | 2.449 | 1.644 | 0.833 | 0.146 | 147.000 | 153.000 | |

| 2003 | 153.800 | 5.404 | 3.514 | 0.957 | 0.785 | 147.000 | 160.000 | |

| 2004 | 155.800 | 5.762 | 3.698 | 0.712 | 0.013 | 149.000 | 160.000 | |

| 2005 | 154.200 | 4.868 | 3.157 | 0.937 | 0.643 | 149.000 | 161.000 | |

| 2006 | 154.800 | 6.058 | 3.913 | 0.860 | 0.228 | 146.000 | 160.000 | |

| 2007 | 151.600 | 3.782 | 2.495 | 0.800 | 0.081 | 147.000 | 155.000 | |

| 2008 | 153.800 | 1.924 | 1.251 | 0.979 | 0.928 | 151.000 | 156.000 | |

| 2009 | 152.400 | 3.912 | 2.567 | 0.902 | 0.421 | 147.000 | 156.000 | |

| 2010 | 150.200 | 3.899 | 2.596 | 0.908 | 0.455 | 145.000 | 154.000 | |

| 2011 | 150.000 | 3.162 | 2.108 | 0.912 | 0.482 | 147.000 | 155.000 | |

| 2012 | 152.000 | 3.082 | 2.028 | 0.903 | 0.429 | 149.000 | 156.000 | |

| 2013 | 151.600 | 2.881 | 1.900 | 0.951 | 0.742 | 148.000 | 155.000 | |

| 2014 | 151.800 | 4.764 | 3.138 | 0.711 | 0.012 | 149.000 | 160.000 | |

| 2015 | 151.600 | 3.286 | 2.168 | 0.845 | 0.179 | 149.000 | 157.000 | |

| 2016 | 149.600 | 4.159 | 2.780 | 0.947 | 0.715 | 145.000 | 155.000 | |

| 2017 | 149.400 | 3.847 | 2.575 | 0.829 | 0.137 | 146.000 | 154.000 | |

| 2018 | 151.400 | 2.408 | 1.590 | 0.957 | 0.787 | 148.000 | 154.000 | |

| 2019 | 147.200 | 2.168 | 1.473 | 0.871 | 0.272 | 144.000 | 149.000 | |

| BBCH 81 (Beginning of ripening) |

2000 | 218.400 | 18.202 | 8.334 | 0.736 | 0.022 | 198.000 | 233.000 |

| 2001 | 217.600 | 18.407 | 8.459 | 0.751 | 0.030 | 197.000 | 233.000 | |

| 2002 | 215.400 | 17.869 | 8.296 | 0.793 | 0.071 | 195.000 | 232.000 | |

| 2003 | 220.000 | 19.455 | 8.843 | 0.862 | 0.235 | 199.000 | 241.000 | |

| 2004 | 218.400 | 19.604 | 8.976 | 0.731 | 0.020 | 197.000 | 234.000 | |

| 2005 | 219.600 | 19.655 | 8.950 | 0.822 | 0.121 | 198.000 | 240.000 | |

| 2006 | 218.600 | 17.925 | 8.200 | 0.727 | 0.018 | 199.000 | 233.000 | |

| 2007 | 218.400 | 18.743 | 8.582 | 0.766 | 0.041 | 198.000 | 235.000 | |

| 2008 | 219.000 | 18.722 | 8.549 | 0.706 | 0.011 | 198.000 | 233.000 | |

| 2009 | 218.600 | 17.516 | 8.013 | 0.758 | 0.035 | 199.000 | 234.000 | |

| 2010 | 217.000 | 17.903 | 8.250 | 0.761 | 0.037 | 197.000 | 232.000 | |

| 2011 | 218.600 | 20.330 | 9.300 | 0.781 | 0.057 | 196.000 | 237.000 | |

| 2012 | 220.600 | 20.256 | 9.182 | 0.835 | 0.153 | 199.000 | 242.000 | |

| 2013 | 217.400 | 16.817 | 7.736 | 0.719 | 0.015 | 199.000 | 231.000 | |

| 2014 | 219.200 | 19.867 | 9.063 | 0.748 | 0.029 | 197.000 | 236.000 | |

| 2015 | 219.600 | 18.863 | 8.590 | 0.736 | 0.022 | 199.000 | 235.000 | |

| 2016 | 218.800 | 17.641 | 8.063 | 0.727 | 0.018 | 199.000 | 233.000 | |

| 2017 | 219.000 | 20.285 | 9.263 | 0.758 | 0.036 | 197.000 | 236.000 | |

| 2018 | 218.000 | 20.112 | 9.226 | 0.722 | 0.016 | 196.000 | 234.000 | |

| 2019 | 217.600 | 17.897 | 8.225 | 0.698 | 0.009 | 198.000 | 231.000 | |

| BBCH 89 (Full maturity) |

2000 | 258.200 | 19.867 | 7.694 | 0.977 | 0.916 | 231.000 | 281.000 |

| 2001 | 260.000 | 17.479 | 6.723 | 0.920 | 0.528 | 236.000 | 277.000 | |

| 2002 | 258.000 | 15.540 | 6.023 | 0.914 | 0.494 | 237.000 | 273.000 | |

| 2003 | 263.400 | 13.704 | 5.203 | 0.919 | 0.525 | 244.000 | 277.000 | |

| 2004 | 266.400 | 13.520 | 5.075 | 0.975 | 0.906 | 249.000 | 283.000 | |

| 2005 | 265.000 | 10.977 | 4.142 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 251.000 | 280.000 | |

| 2006 | 260.600 | 11.502 | 4.414 | 0.914 | 0.490 | 244.000 | 272.000 | |

| 2007 | 261.600 | 17.038 | 6.513 | 0.975 | 0.906 | 238.000 | 281.000 | |

| 2008 | 263.400 | 13.831 | 5.251 | 0.949 | 0.727 | 247.000 | 281.000 | |

| 2009 | 260.200 | 15.675 | 6.024 | 0.996 | 0.997 | 239.000 | 281.000 | |

| 2010 | 262.200 | 11.946 | 4.556 | 0.918 | 0.519 | 251.000 | 280.000 | |

| 2011 | 258.600 | 14.673 | 5.674 | 0.924 | 0.557 | 236.000 | 273.000 | |

| 2012 | 258.400 | 18.916 | 7.320 | 0.885 | 0.331 | 228.000 | 275.000 | |

| 2013 | 260.800 | 18.674 | 7.160 | 0.850 | 0.195 | 230.000 | 276.000 | |

| 2014 | 262.400 | 18.366 | 6.999 | 0.913 | 0.487 | 233.000 | 280.000 | |

| 2015 | 253.600 | 14.876 | 5.866 | 0.853 | 0.205 | 238.000 | 271.000 | |

| 2016 | 262.000 | 12.748 | 4.866 | 0.863 | 0.238 | 248.000 | 276.000 | |

| 2017 | 259.000 | 12.884 | 4.975 | 0.849 | 0.190 | 245.000 | 272.000 | |

| 2018 | 258.200 | 16.146 | 6.253 | 0.861 | 0.232 | 232.000 | 272.000 | |

| 2019 | 257.000 | 18.166 | 7.068 | 0.873 | 0.280 | 227.000 | 273.000 |

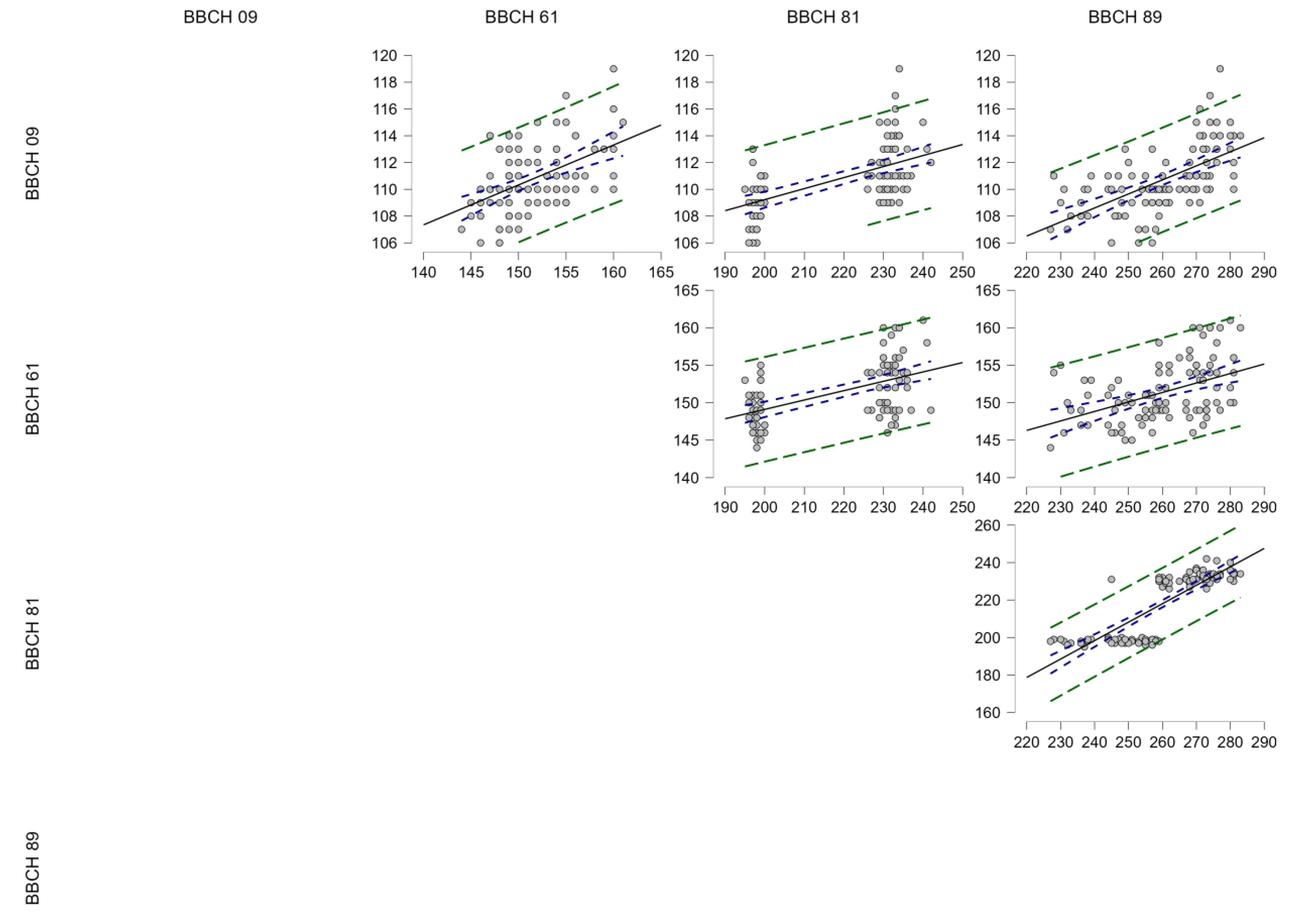

| Variable | BBCH 09 | BBCH 61 | BBCH 81 | BBCH 89 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBCH 09 | Pearson’s r | — | |||

| p-value | — | ||||

| Lower 95% CI | — | ||||

| Upper 95% CI | — | ||||

| BBCH 61 | Pearson’s r | 0.493*** | — | ||

| p-value | < 0.001 | — | |||

| Lower 95% CI | 0.328 | — | |||

| Upper 95% CI | 0.628 | — | |||

| BBCH 81 | Pearson’s r | 0.569*** | 0.522*** | — | |

| p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | — | ||

| Lower 95% CI | 0.419 | 0.363 | — | ||

| Upper 95% CI | 0.688 | 0.652 | — | ||

| BBCH 89 | Pearson’s r | 0.610*** | 0.445*** | 0.828*** | — |

| p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | — | |

| Lower 95% CI | 0.470 | 0.273 | 0.754 | — | |

| Upper 95% CI | 0.720 | 0.590 | 0.881 | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).