Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

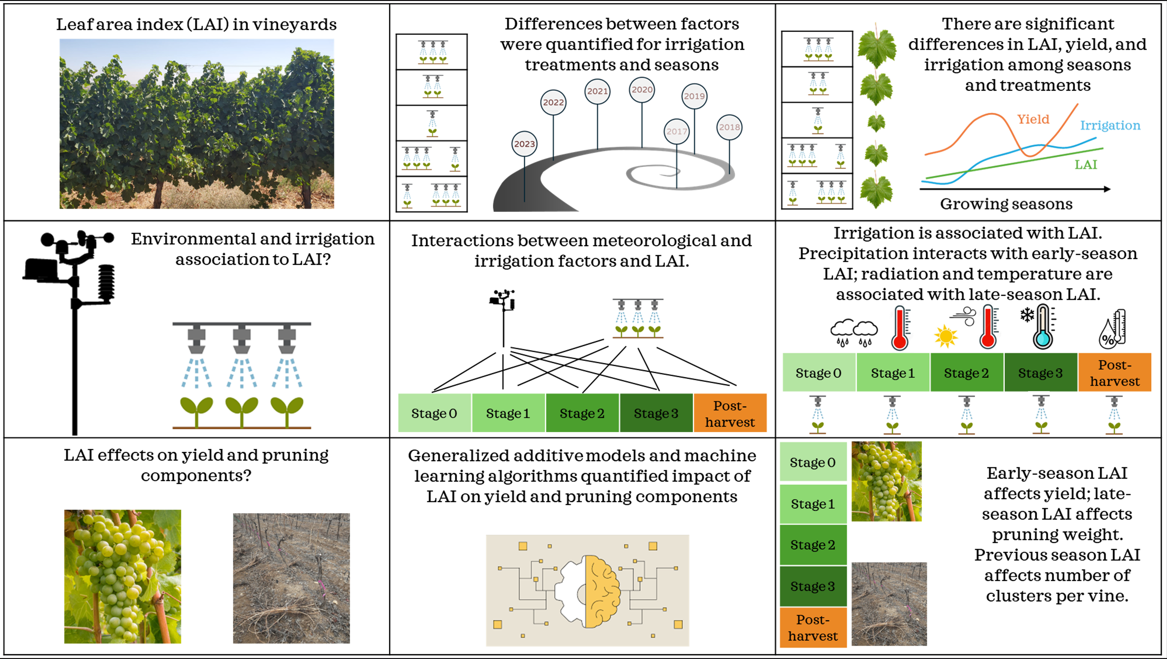

Abstract

Leaf Area Index (LAI) is a key physiological metric in viticulture, associated with vine health, yield, and responsive to environmental and management factors. This study, conducted in a Mediterranean Sauvignon Blanc vineyard (2017–2023), examines how irrigation and environmental variables affect LAI across phenological stages and its impact on yield (clusters per vine, cluster weight, total yield) and pruning parameters (cane weight, pruning weight). Results show irrigation is the primary driver of LAI, with increased water availability promoting leaf area expansion. Environmental factors, including temperature, vapor pressure deficit, and solar radiation, influence LAI dynamics, with chilling hours playing a crucial role post-veraison. Excessive LAI (>1.6–1.7) reduces yield due to competition between vegetative and reproductive sinks. Early-season LAI correlates more strongly with yield, while late-season LAI predicts pruning weight and cane growth. Machine learning models reveal that excessive pre-veraison LAI in one season reduces cluster numbers in the next. This study highlights LAI as a critical tool for vineyard management. While irrigation promotes vegetative growth, excessive LAI can hinder fruit set and yield, emphasizing the need for strategic irrigation timing, canopy management, and climate adaptation to sustain long-term vineyard productivity.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

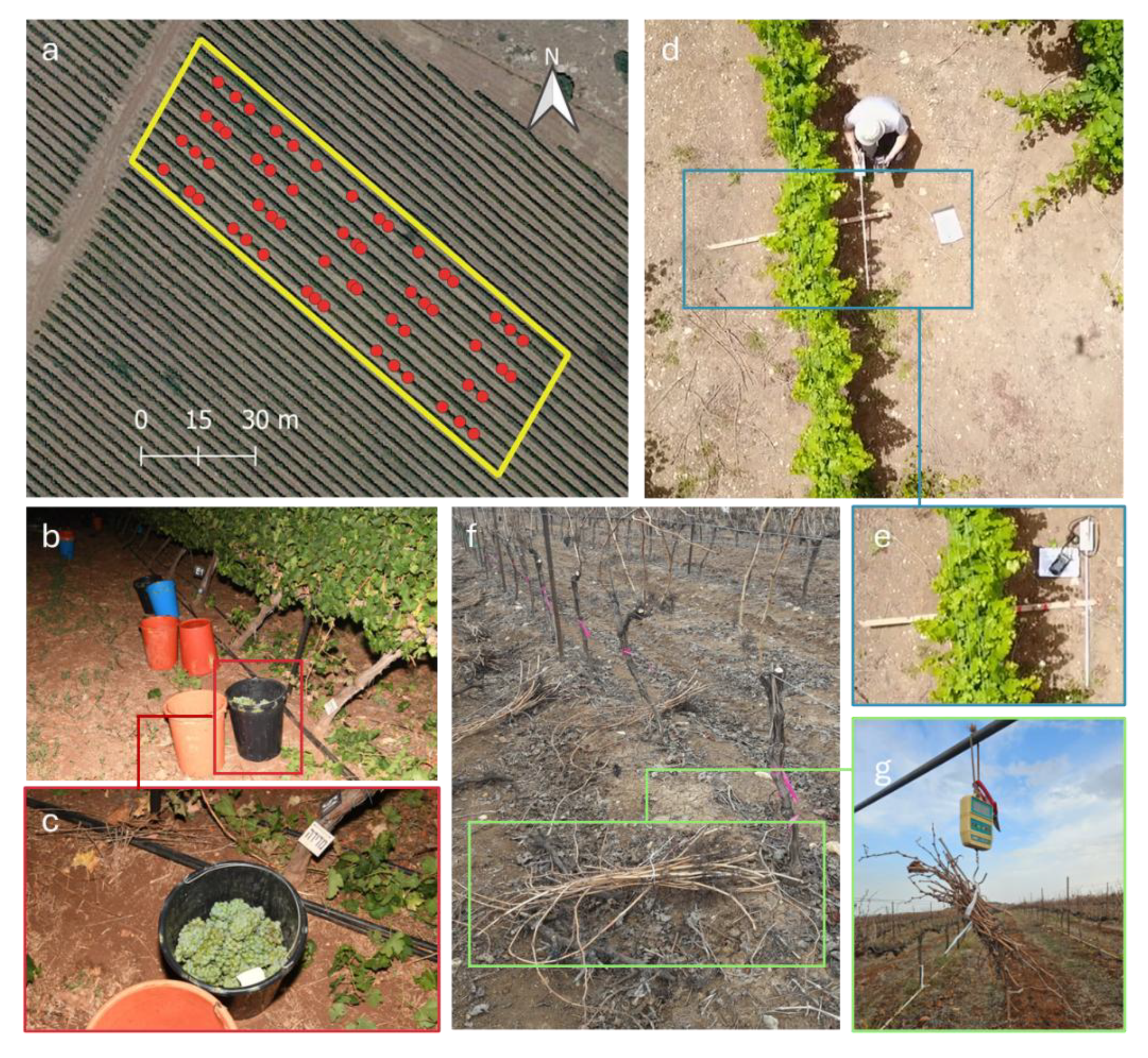

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Experiment Design

2.3. Data Collection and Feature Engineering

2.3.1. Field Data

2.3.2. Meteorological Data

- -

- Total and Spring precipitation: The accumulated precipitation (mm) during the winter and spring preceding each growing season; Total precipitation and spring precipitation were accumulated from October 1 to April 30 and from March 1 to April 30 of each winter and spring, respectively. The range of values during the experimental period was very wide (250-555 mm in total, 24-134 mm in spring, Table 2), with quite high CVs (21.44% and 50.83%).

- -

- Temperature: Minimum, maximum, and mean daily temperature values were averaged across phenological stages for each season.

- -

- Vapor pressure deficit (VPD): Daily VPD values were calculated using the Magnus formula [34] and minimum, maximum and mean daily values were averaged across phenological stages for each growing season.

- -

- Total chilling hours: Accumulated number of cool hours during each winter preceding the growing seasons. They were calculated using the a scoring system: Hourly temperature below 7 °C = 1 chilling hour; between 7 °C and 10 °C = 0.5 chilling hour; between 10 °C and 18 °C = 0; and above 18 °C = − 1 chilling hour. The daily chilling hours were then summed, while negative chilling hours were counted as 0. Daily chilling hours were accumulated between November and April and provided as total seasonal chilling hours (Table 2). During the experimental period, the values ranged between 197 and 571 chilling hours, with a CV of 31.3%.

- -

- Reference evapotranspiration (ETo) : was calculated using the FAO Penman-Monteith equation [35]. The daily mean values were averaged for each phenological stage during each growing season. Values ranged between 2.3 and 8.2 mm day -1, with CV=27.5%.

- -

- Wind speed: hourly means were averaged for each phenological stage during each growing season, ranging between 4.5 and 7.4 mm sec-1.

- -

- Mean radiation: the hourly values were summed into daily records, and further averaged at the phenological stage scale. Values ranged between 14.2 and 28 MJ m-2 day-1.

- -

- Relative humidity (RH): Mean daily RH values were averaged for each phenological stage. Values ranged from 50% to 78%, with a low variance (CV=10.45%).

2.4. Modeling Framework

2.4.1. Irrigation and Leaf Area Variations Among Seasons and Treatments

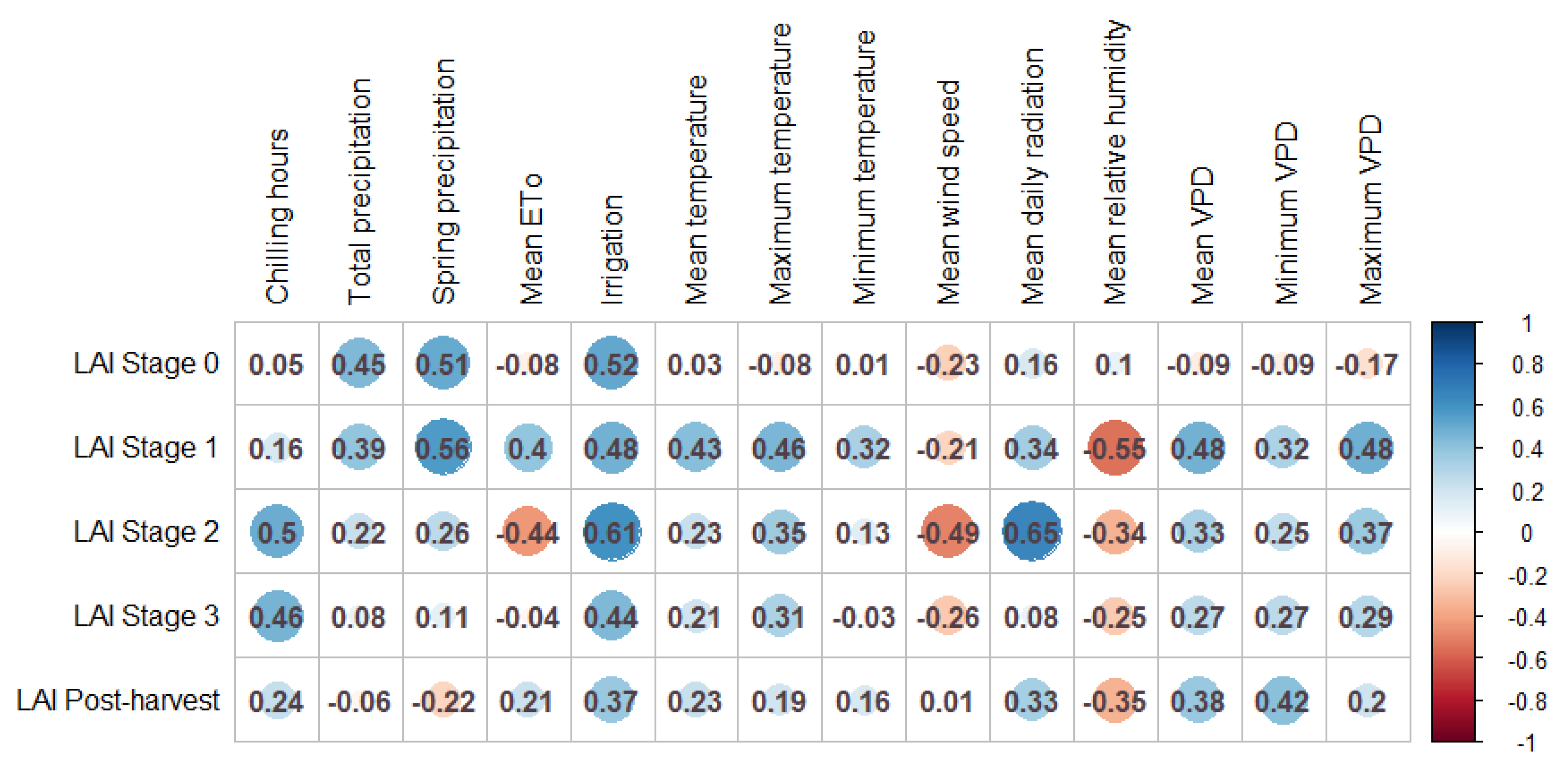

2.4.2. LAI Associations to Environmental and Irrigation Factors

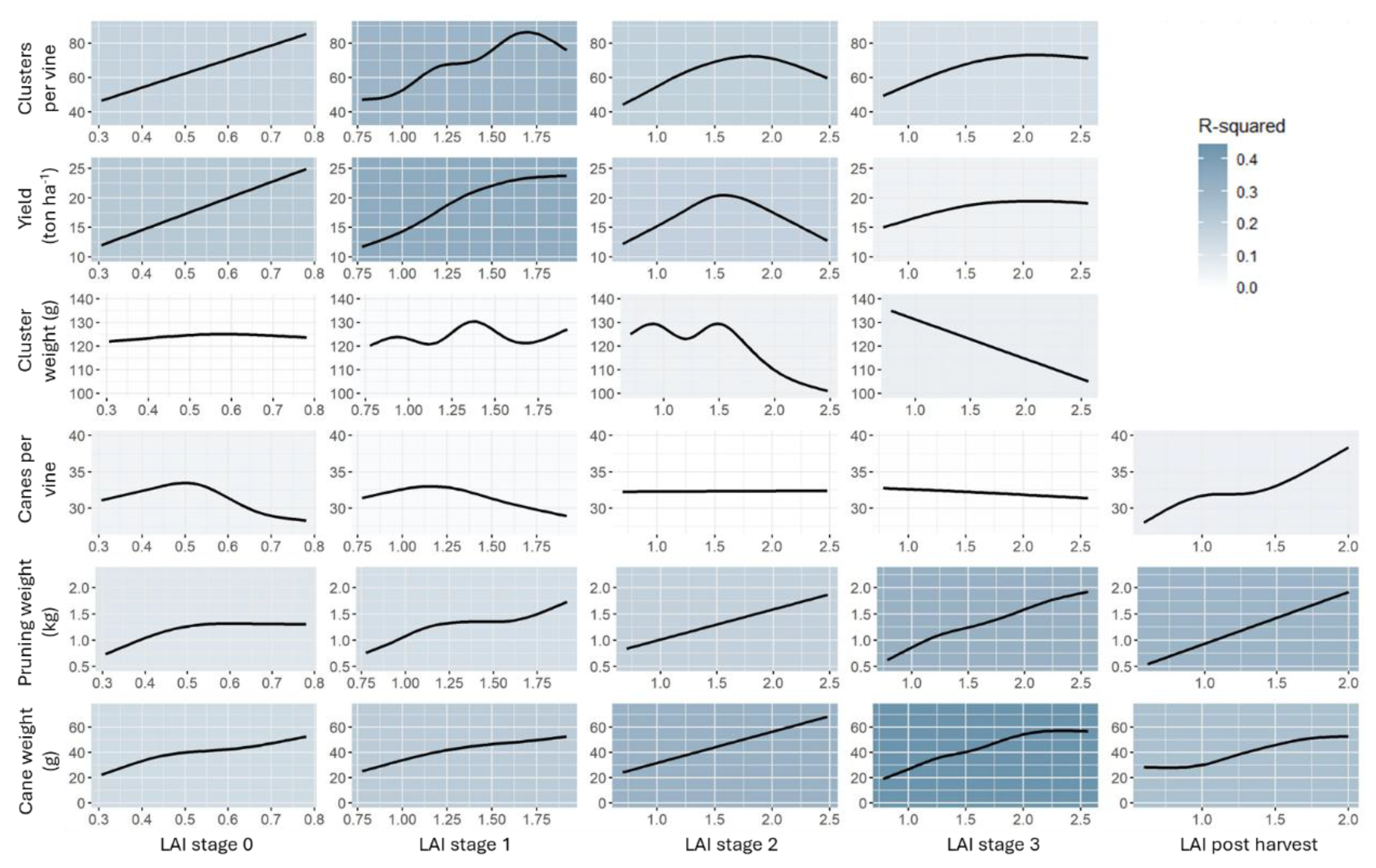

2.4.3. LAI Phenology Effects on Reproductive and Pruning Components

- 1.

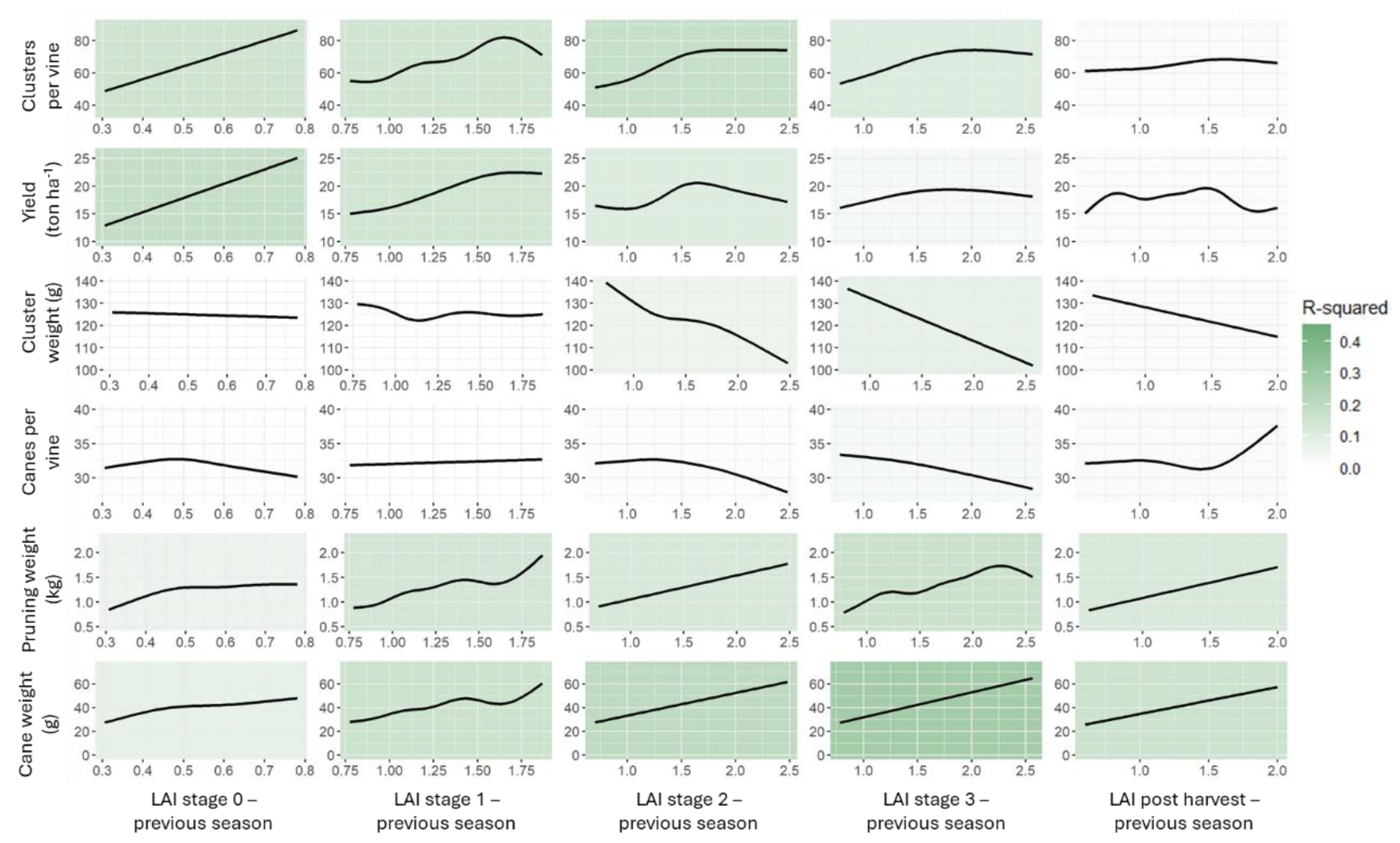

- Yield and pruning components were separately analyzed against LAI values at each phenological stage, and against LAI values from the previous season. This analysis was conducted using the generalized additive model (GAM), to enable quantifying the non-linearity of some of the relationships. GAM is an additive model technique where the influence of each covariate is captured by a smooth function [42]. These smooth functions can adapt to both linear and non-linear relationships, providing greater flexibility compared to traditional linear models. The degree of smoothness in the model is controlled by a smoothing parameter, which helps to prevent overfitting by penalizing overly complex models [43]. In this study, the spline function was used for smoothing the covariates, and Gaussian distribution was assumed. All GAM models were applied using 8 knots to avoid overfitting the relationships. The coefficient of determination (R2) was extracted from each model to define the proportion of variance in the response variable explained by the model. In addition, for each model the partial dependent plot was extracted to visualize the patterns of relationship between LAI and each component. GAM models were fitted using the “mgcv” package in R [44], and the partial plots were produced using the “pdp” package [45]. Heatmaps were subsequently produced based on R2 values to enable comparison between the strengths of the different models, while incorporating the partial plots to illustrate the nature of the relationships between LAI and the respective components.

- 2.

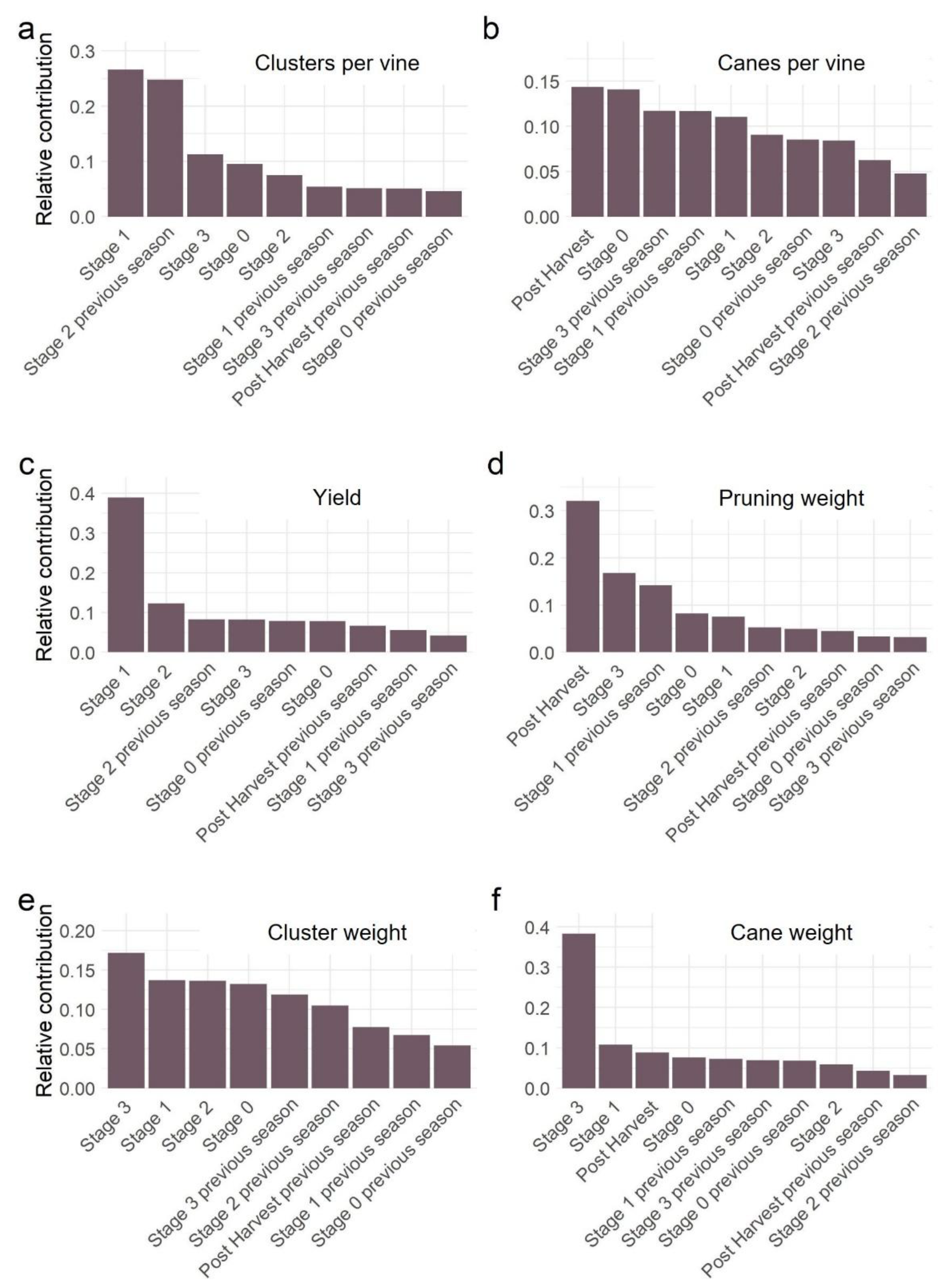

- To determine the relative importance of LAI values at different stages (including the current and previous season) on yield and pruning components, we employed the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm. XGBoost is a powerful ensemble learning method that combines multiple decision trees to create a robust predictive model in an iterative manner, with each subsequent tree focusing on correcting the errors of its predecessors. XGBoost incorporates regularization techniques to prevent overfitting and can effectively handle complex relationships between variables [46]. Given the potential non-linearity and interactions between LAI at different stages and the yield/pruning components, XGBoost was selected for its ability to capture these complex relationships and its strong predictive performance. The objective parameter was set to optimize the regression using a squared error loss function, using a maximum of 100 iterations. Finally, the relative contribution of the features (e.g., LAI at the different stages at current and previous season) were extracted and visualized. The XGBoost algorithm was applied using the “xgboost” package in R [47] and the results were visualized using “ggplot2” [48]. To evaluate model reliability, a validation process was conducted for each yield and pruning component. The dataset was randomly split into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets. The model was trained on the training set and then used to predict the component values for the test set. Model accuracy was assessed using the following metrics:

- -

- Pearson correlation (r): Measures the strength and direction of the linear relationship between predicted and observed values. Higher absolute values of 'r' indicate stronger correlations.

- -

- Paired t-test (t): Evaluates whether the mean predicted values differ significantly from the mean observed values in the test set.

- -

- Kolmogorov-Smirnov (D): Compares the distribution of predicted values to the distribution of observed values in the test set to assess whether they are statistically different.

- -

- Mean absolute error (MAE): Measures the average absolute difference between predicted and observed values. MAE was further normalized to the range of the test set to provide the error in percentage. MAE was calculated using the “Metrics” library in R [49].

3. Results

3.1. Irrigation and Leaf Area Variations Among Seasons and Treatments

3.2. LAI Associations to Environmental and Irrigation Factors

3.3. LAI Phenology Effects on Reproductive and Pruning Components

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ETo | Reference evapotranspiration |

| ETc | Crop evapotranspiration |

| LAI | Leaf area index |

| VPD | Vapor pressure deficit |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

References

- Watson, D.J. Comparative Physiological Studies on the Growth of Field Crops: I. Variation in Net Assimilation Rate and Leaf Area between Species and Varieties, and within and between Years. Ann. Bot. 1947, 11, 41–76. [CrossRef]

- White, W.A.; Alsina, M.M.; Nieto, H.; McKee, L.G.; Gao, F.; Kustas, W.P. Determining a robust indirect measurement of leaf area index in California vineyards for validating remote sensing-based retrievals. Irrig. Sci. 2018, 37, 269–280. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Gao, F.; Anderson, M.; Kustas, W.; Alsina, M.; Sanchez, L.; Sams, B.; McKee, L.; Dulaney, W.; White, W.; et al. Daily Mapping of 30 m LAI and NDVI for Grape Yield Prediction in California Vineyards. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 317. [CrossRef]

- Ohana-Levi, N.; Gao, F.; Knipper, K.; Kustas, W.P.; Anderson, M.C.; del Mar Alsina, M.; Sanchez, L.A.; Karnieli, A. Time-series clustering of remote sensing retrievals for defining management zones in a vineyard. Irrig. Sci. 2022, 1, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Leolini, L.; Bregaglio, S.; Ginaldi, F.; Costafreda-Aumedes, S.; Di Gennaro, S.F.; Matese, A.; Maselli, F.; Caruso, G.; Palai, G.; Bajocco, S.; et al. Use of remote sensing-derived fPAR data in a grapevine simulation model for estimating vine biomass accumulation and yield variability at sub-field level. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 705–726. [CrossRef]

- Munitz, S.; Schwartz, A.; Netzer, Y. Effect of timing of irrigation initiation on vegetative growth, physiology and yield parameters in Cabernet Sauvignon grapevines. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2020, 26, 220–232. [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.E.; Ayars, J.E. Grapevine water use and the crop coefficient are linear functions of the shaded area measured beneath the canopy. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2005, 132, 201–211. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Asher, J.; Tsuyuki, I.; Bravdo, B.-A.; Sagih, M. Irrigation of grapevines with saline water: I. Leaf area index, stomatal conductance, transpiration and photosynthesis. Agric. Water Manag. 2006, 83, 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Ohana-Levi, N.; Munitz, S.; Ben-Gal, A.; Schwartz, A.; Peeters, A.; Netzer, Y. Multiseasonal grapevine water consumption – Drivers and forecasting. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 280, 107796. [CrossRef]

- Netzer, Y.; Yao, C.; Shenker, M.; Bravdo, B.A.; Schwartz, A. Water use and the development of seasonal crop coefficients for Superior Seedless grapevines trained to an open-gable trellis system. Irrig. Sci. 2009, 27, 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Ohana-Levi, N.; Cohen, Y.; Munitz, S.; Michaelovsky, R.; Ferman Mintz, D.; Hagag, N.; Getz, Y.; Netzer, Y. The response of yield, number of clusters, and cluster weight to meteorological factors and irrigation practices in grapevines: A multi-experiment study. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2024, 326, 112761. [CrossRef]

- Somkuwar, S.G.; Taware, P.B.; Bondage, D.D.; Nawale, S. Influence of shoot density on leaf area, yield and quality of Tas-A-Ganesh grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) grafted on Dog Ridge rootstock. Int. Res. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 94–99.

- Hunter, J.J. Implications of Seasonal Canopy Management and Growth Compensation in Grapevine. South African J. Enol. Vitic. 2000, 21, 81–91. [CrossRef]

- Munitz, S.; Schwartz, A.; Netzer, Y. Water consumption, crop coefficient and leaf area relations of a Vitis vinifera cv. “Cabernet Sauvignon” vineyard. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 219, 86–94. [CrossRef]

- Ohana-Levi, N.; Munitz, S.; Ben-Gal, A.; Netzer, Y. Evaluation of within-season grapevine evapotranspiration patterns and drivers using generalized additive models. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 228, 105808. [CrossRef]

- Lavee, S.; May, P. Dormancy of grapevine buds - facts and speculation. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 1997, 3, 31–46. [CrossRef]

- Picón-Toro, J.; González-Dugo, V.; Uriarte, D.; Mancha, L.A.; Testi, L. Effects of canopy size and water stress over the crop coefficient of a “Tempranillo” vineyard in south-western Spain. Irrig. Sci. 2012, 30, 419–432. [CrossRef]

- Mancha, L.A.; Uriarte, D.; Prieto, M.D.H. Characterization of the Transpiration of a Vineyard under Different Irrigation Strategies Using Sap Flow Sensors. Water 2021, Vol. 13, Page 2867 2021, 13, 2867. [CrossRef]

- Bahat, I.; Netzer, Y.; Grünzweig, J.M.; Alchanatis, V.; Peeters, A.; Goldshtein, E.; Ohana-Levi, N.; Ben-Gal, A.; Cohen, Y. In-season interactions between vine vigor, water status and wine quality in terrain-based management-zones in a ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ vineyard. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1636. [CrossRef]

- Arab, S.T.; Noguchi, R.; Matsushita, S.; Ahamed, T. Prediction of grape yields from time-series vegetation indices using satellite remote sensing and a machine-learning approach. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 22, 100485. [CrossRef]

- Greer, D.H.; Weedon, M.M. Interactions between light and growing season temperatures on, growth and development and gas exchange of Semillon (Vitis vinifera L.) vines grown in an irrigated vineyard. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 54, 59–69. [CrossRef]

- Intrigliolo, D.S.; Castel, J.R. Response of grapevine cv. “Tempranillo” to timing and amount of irrigation: Water relations, vine growth, yield and berry and wine composition. Irrig. Sci. 2010, 28, 113–125. [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.E. Growth of ‘Thompson Seedless’ Grapevines: I. Leaf Area Development and Dry Weight Distribution. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1987, 112, 325–330. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.C. Projection of phenology response to climate change in rainfed vineyards in north-east Spain. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 247, 104–115. [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Fidelibus, M.W.; Kennedy, J.A.; Kurtural, S.K. Precipitation before Flowering Determined Effectiveness of Leaf Removal Timing and Irrigation on Wine Composition of Merlot Grapevine. Plants 2021, Vol. 10, Page 1865 2021, 10, 1865. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lüscher, J.; Brillante, L.; Nelson, C.C.; Al-Kereamy, A.M.; Zhuang, S.; Kurtural, S.K. Precipitation before bud break and irrigation affect the response of grapevine ‘Zinfandel’ yields and berry skin phenolic composition to training systems. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2017, 222, 153–161. [CrossRef]

- van Es, H.M.; Gomes, C.P.; Sellmann, M.; van Es, C.L. Spatially-Balanced Complete Block designs for field experiments. Geoderma 2007, 140, 346–352. [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements-FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, 1998;.

- Ohana-Levi, N.; Mintz, D.F.; Hagag, N.; Stern, Y.; Munitz, S.; Friedman-Levi, Y.; Shacham, N.; Grünzweig, J.M.; Netzer, Y. Grapevine responses to site-specific spatiotemporal factors in a Mediterranean climate. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 259, 107226. [CrossRef]

- Ohana-Levi, N.; Zachs, I.; Hagag, N.; Shemesh, L.; Netzer, Y. Grapevine stem water potential estimation based on sensor fusion. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107016. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J. Understanding grape berry development. Pract. Winer. Vineyard 2002, 4, 1–5.

- Netzer, Y.; Munitz, S.; Shtein, I.; Schwartz, A. Structural memory in grapevines: Early season water availability affects late season drought stress severity. Eur. J. Agron. 2019, 105, 96–103. [CrossRef]

- Moritz, S.; Bartz-Beielstein, T. imputeTS: Time Series Missing Value Imputation in R. R J. 2017, 9, 207–218. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wei, Q.; Peng, S.; Yu, Y. Error of Saturation Vapor Pressure Calculated by Different Formulas and Its Effect on Calculation of Reference Evapotranspiration in High Latitude Cold Region. Procedia Eng. 2012, 28, 43–48. [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements- Irrigation and Drainage Paper 56; FAO, 1998; Vol. 56;.

- Wickham, H.; Francois, R.; Henry, L.; Muller, K. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R package version 1.0.8. 2022.

- Leutner, B.; Horning, N.; Schwalb-Willmann, J.; Hijmans, R.J.; Maintainer, ] RStoolbox: Tools for Remote Sensing Data Analysis. R package version 0.2.6. 2019, Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/packa.

- Grolemund, G.; Wickham, H. Dates and Times Made Easy with lubridate. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 40, 1–25.

- de Mendiburu, F. agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. R package version 1.3-5 2021.

- R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing 2021, Available online: https://www.R-project.org/.

- Taiyun Wei, M.; Taiyun Wei cre, A.; Simko aut, V.; Levy ctb, M.; Xie ctb, Y.; Jin ctb, Y.; Zemla ctb, J. Package “corrplot”: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix 2021, Available from https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot.

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Generalized Additive Models. Stat. Sci. 1986, 1, 297–310. [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Stable and Efficient Multiple Smoothing Parameter Estimation for Generalized Additive Models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2012, 99, 673–686. [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models; 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, 2017; ISBN 9781315370279.

- Greenwell, B.M. pdp: An R package for constructing partial dependence plots. R J. 2017, 9, 421–436. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. Proc. ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min. 2016, 13-17-August-2016, 785–794. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; He, T.; Benesty, M.; Khotilovich, V.; Tang, Y.; Cho, H.; Chen, K.; Mitchell, R.; Cano, I.; Zhou, T.; et al. xgboost: Extreme Gradient Boosting 2022.

- Wickham, H. ggplot2 : Elegant graphics for data analysis; Springer: Verlag, New York, 2016; ISBN 9780387981406.

- Hamner, B.; Frasco, M.; Ledell, E. Package “Metrics” - Evaluation Metrics for Machine Learning; 2018;.

- Munitz, S.; Netzer, Y.; Schwartz, A. Sustained and regulated deficit irrigation of field-grown Merlot grapevines. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2016, 1, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Intrigliolo, D.S.; Castel, J.R. Effects of Irrigation on the Performance of Grapevine cv. Tempranillo in Requena, Spain. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2008, 59, 30–38. [CrossRef]

- Camps, J.O.; Ramos, M.C. Grape harvest and yield responses to inter-annual changes in temperature and precipitation in an area of north-east Spain with a Mediterranean climate. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 853–864. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.C.; Mulligan, M. Spatial modelling of the impact of climate variability on the annual soil moisture regime in a mechanized Mediterranean vineyard. J. Hydrol. 2005, 306, 287–301. [CrossRef]

- Junquera, P.; Lissarrague, J.R.; Jiménez, L.; Linares, R.; Baeza, P. Long-term effects of different irrigation strategies on yield components, vine vigour, and grape composition in cv. Cabernet-Sauvignon (Vitis vinifera L.). Irrig. Sci. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Zufferey, V.; Spring, J.L.; Verdenal, T.; Dienes, A.; Belcher, S.; Lorenzini, F.; Koestel, C.; Rösti, J.; Gindro, K.; Spangenberg, J.; et al. The influence of water stress on plant hydraulics, gas exchange, berry composition and quality of Pinot Noir wines in Switzerland. OENO One 2017, 51, 37–57. [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, U.; Degu, A.; Gendler, T.; Fait, A.; Rachmilevitch, S. The variability in the xylem architecture of grapevine petiole and its contribution to hydraulic differences. Funct. Plant Biol. 2014, 42, 357–365. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J.C.; Savoi, S.; Dostal, J.; Elezovic, K.; Chatzisavva, M.; Forneck, A.; Savi, T. The legacy of past droughts induces water-sparingly behaviour in Grüner Veltliner grapevines. Plant Biol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shtein, I.; Wolberg, S.; Munitz, S.; Zait, Y.; Rosenzweig, T.; Grünzweig, J.M.; Ohana-Levi, N.; Netzer, Y. Multi-seasonal water-stress memory versus temperature-driven dynamic structural changes in grapevine. Tree Physiol. 2021, 41, 1199–1211. [CrossRef]

- Lavoie-Lamoureux, A.; Sacco, D.; Risse, P.A.; Lovisolo, C. Factors influencing stomatal conductance in response to water availability in grapevine: A meta-analysis. Physiol. Plant. 2017, 159, 468–482. [CrossRef]

- Buttrose, M.S. Some Effects of Light Intensity and Temperature on Dry Weight and Shoot Growth of Grape-Vine. Ann. Bot. 1968, 32, 753–765. [CrossRef]

- Lavee, S. Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera) Growth and Performance in Warm Climates. Temp. Fruit Crop. Warm Clim. 2000, 343–366. [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, B.; Berry, P.; Moulia, B. Review: Wind impacts on plant growth, mechanics and damage. Plant Sci. 2016, 245, 94–118. [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, M.J. Thigmomorphogenesis: The response of plant growth and development to mechanical stimulation - With special reference to Bryonia dioica. Planta 1973, 114, 143–157. [CrossRef]

- Pollastrini, M.; Di Stefano, V.; Ferretti, M.; Agati, G.; Grifoni, D.; Zipoli, G.; Orlandini, S.; Bussotti, F. Influence of different light intensity regimes on leaf features of Vitis vinifera L. in ultraviolet radiation filtered condition. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2011, 73, 108–115. [CrossRef]

- Dobrowski, S.Z.; Ustin, S.L.; Wolpert, J.A. Grapevine dormant pruning weight prediction using remotely sensed data. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2003, 9, 177–182. [CrossRef]

- Netzer, Y.; Suued, Y.; Harel, M.; Ferman-Mintz, D.; Drori, E.; Munitz, S.; Stanevsky, M.; Grünzweig, J.M.; Fait, A.; Ohana-Levi, N.; et al. Forever Young? Late Shoot Pruning Affects Phenological Development, Physiology, Yield and Wine Quality of Vitis vinifera cv. Malbec. Agric. 2022, Vol. 12, Page 605 2022, 12, 605. [CrossRef]

- Santesteban, L.G.; Miranda, C.; Royo, J.B. Regulated deficit irrigation effects on growth, yield, grape quality and individual anthocyanin composition in Vitis vinifera L. cv. “Tempranillo.” Agric. Water Manag. 2011, 98, 1171–1179. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.G.; Vanden Heuvel, J.E. Influence of Grapevine Training Systems on Vine Growth and Fruit Composition: A Review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2009, 60, 251–268. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, M.C.; Castagnoli, S. Leaf Canopy Structure and Vine Performance. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2000, 51, 390–396. [CrossRef]

- Uriarte, D.; Mancha, L.A.; Moreno, D.; Bejarano, M.A.; Valdés, E.; Talaverano, I.; Prieto, M.H. Effects of timing of water deficit induction on “Doña Blanca” white grapevine under semi-Arid growing conditions of south-western Spain. Acta Hortic. 2017, 1150, 493–500. [CrossRef]

- Bindon, K.A.; Dry, P.R.; Loveys, B.R. The interactive effect of pruning level and irrigation strategy on water use efficiency of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Shiraz. South African J. Enol. Vitic. 2008, 29, 59–70. [CrossRef]

- Hamman, R.A.J.; Dami, I.E. Effects of irrigation on wine grape growth and fruit quality. Horttechnology 2000, 10, 162–168.

- Intrigliolo, D.S.; Castel, J.R.; Cárcel, S. Effects of crop level and irrigation on yield and wine quality of tempranillo grapevines in a dry year. Acta Hortic. 2008, 792, 371–378. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.I.; Malheiro, A.C.; Bacelar, E.A. Morphology, Physiology and Analysis Techniques of Grapevine Bud Fruitfulness: A Review. Agric. 2021, Vol. 11, Page 127 2021, 11, 127. [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.; Rawnsley, B. Factors influencing primary bud necrosis (PBN) in Australian vineyards. Acta Hortic. 2005, 689, 81–86. [CrossRef]

- Rumbolz, J.; Gubler, W.D. Susceptibility of grapevine buds to infection by powdery mildew Erysiphe necator. Plant Pathol. 2005, 54, 535–548. [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.; Coles, R.; Conran, J.G.; Rawnsley, B. The progression of primary bud necrosis in the grapevine cv. Shiraz (Vitis vinifera L.): A histological analysis. Vitis 2006, 45, 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Lavee, S.; Melamu, H.; Ziv, M.; Bernstein, Z. Necrosis in grapevine buds (Vitis vinifera cv. Queen of Vineyard) I. Relation to vegetative vigor1). Vitis 1981, 20, 8–14.

- Monteiro, A.I.; Ferreira, H.; Ferreira-Cardoso, J. V; Malheiro, A.C.; Bacelar, E.A.; Deloire, A. Assessment of bud fruitfulness of three grapevine varieties grown in northwest Portugal. OENO One 2022, 56, 385–395. [CrossRef]

- Intrigliolo, D.S.; Lizama, V.; García-Esparza, M.J.; Abrisqueta, I.; Álvarez, I. Effects of post-veraison irrigation regime on Cabernet Sauvignon grapevines in Valencia, Spain: Yield and grape composition. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 170, 110–119. [CrossRef]

- Petrie, P.R.; Cooley, N.M.; Clingeleffer, P.R. The effect of post-veraison water deficit on yield components and maturation of irrigated Shiraz (Vitis vinifera L.) in the current and following season. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2004, 10, 203–215. [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, M.; Sanz-Ablanedo, E.; Pereira-Obaya, D.; Ramón Rodríguez-Pérez, J.; Lukáš, J.; Hamouz, P.; Antonio Dominguez-Gómez, J. Vineyard Pruning Weight Prediction Using 3D Point Clouds Generated from UAV Imagery and Structure from Motion Photogrammetry. Agron. 2021, Vol. 11, Page 2489 2021, 11, 2489. [CrossRef]

| Stage 0 Budbreak-Flowering | Stage 1 Flowering-Bunch closure | Stage 2 Bunch closure-Veraison | Stage 3 Veraison-Harvest | Stage 4 Post Harvest |

Pruning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of start dates | March 7- April 6 |

April 18 – May 14 |

May 30 – June 11 |

June 23 – July 18 |

July 27 – August 19 |

February 5 – March 7 |

| Mean start date | March 19 | May 6 | June 4 | June 29 | August 9 | February 22 |

| Average duration | 48 | 29 | 25 | 41 | 52 | - |

| Category | Variable | Min | Max | Median | Mean | SD | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield components | Clusters per vine | 23 | 110 | 62 | 64.17 | 19.28 | 30.05 |

| Yield (ton ha-1) | 5.19 | 34.81 | 17.57 | 18.16 | 5.85 | 32.2 | |

| Cluster weight (g) | 51.66 | 199 | 121 | 123.79 | 25.91 | 20.93 | |

| Pruning components | Canes per vine | 16 | 48 | 32 | 32.33 | 6.11 | 18.91 |

| Pruning weight (Kg) | 0.19 | 2.54 | 1.16 | 1.23 | 0.47 | 38.27 | |

| Cange weight (g) | 0 | 78.89 | 36.03 | 38.4 | 14.45 | 37.63 | |

| Leaf area index | Mean LAI at Stage 0 (m2 m-2) | 0.31 | 0.78 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.1 | 19 |

| Mean LAI at Stage 1 (m2 m-2) | 0.77 | 1.92 | 1.19 | 1.22 | 0.24 | 19.3 | |

| Mean LAI at Stage 2 (m2 m-2) | 0.7 | 2.48 | 1.4 | 1.39 | 0.36 | 26.02 | |

| Mean LAI at Stage 3 (m2 m-2) | 0.78 | 2.56 | 1.33 | 1.41 | 0.38 | 27.21 | |

| Mean LAI at Post-harvest (m2 m-2) | 0.6 | 2 | 1.2 | 1.22 | 0.27 | 21.96 | |

| Irrigation treatments | Irrigation per season (mm) | 191.7 | 710.8 | 397.1 | 396.4 | 126.6 | 31.93 |

|

Meteorology (at the phenological stage scale) |

Total (seasonal) precipitation (mm) | 250.8 | 555.3 | 441.8 | 421.53 | 90.39 | 21.44 |

| Spring precipitation (mm) | 23.8 | 134.4 | 73.9 | 72.09 | 36.64 | 50.83 | |

| Mean temperature (°C) | 9.62 | 26.64 | 22.99 | 21.26 | 4.76 | 22.39 | |

| Maximum temperature (°C) | 13.37 | 36.93 | 30.06 | 27.78 | 5.98 | 21.54 | |

| Minimum temperature (°C) | 6.79 | 21.74 | 17.74 | 16.57 | 4.2 | 25.36 | |

| Mean vapor pressure deficit (kPa) | 0.3 | 1.96 | 1.17 | 1.11 | 0.37 | 33.85 | |

| Minimum vapor pressure deficit (kPa) | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.1 | 57.03 | |

| Maximum vapor pressure deficit (kPa) | 0.64 | 4.77 | 2.82 | 2.57 | 0.95 | 37.07 | |

| Chilling hours | 197.5 | 571.5 | 409.25 | 390.5 | 122.14 | 31.28 | |

| Mean ETo (mm day-1) | 2.32 | 8.16 | 6.69 | 6.07 | 1.67 | 27.52 | |

| Mean wind speed (m sec-1) | 4.53 | 7.4 | 5.62 | 5.72 | 0.62 | 10.81 | |

| Mean radiation (MJ m-2 day-1) | 14.18 | 28.11 | 22.3 | 22.93 | 3.92 | 17.08 | |

| Mean relative humidity (%) | 49.61 | 77.89 | 66.69 | 65.97 | 6.89 | 10.45 |

| Treatment | Mean LAI (mm2 mm-2) | Mean irrigation amount (mm day-1) |

Yield (ton ha-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 1.02 d | 1.85 e | 16.9 e |

| Medium | 1.17 b | 2.85 b | 19 a |

| High | 1.28 a | 3.8 a | 18.7 b |

| Low to High | 1.08 c | 2.57 c | 18.3 c |

| High to Low | 1.17 b | 2.42 d | 18 d |

| Season | Mean LAI (mm2 mm-2) | Mean irrigation amount (mm day-1) | Yield (ton ha-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 0.93 g | 2.00 e | 13.4 f |

| 2018 | 1.02 f | 1.96 e | 15.3 e |

| 2019 | 1.07 e | 2.60 d | 21.4 c |

| 2020 | 1.13 d | 2.89 c | 21.9 b |

| 2021 | 1.25 c | 3.13 b | 13.2 g |

| 2022 | 1.29 b | 3.05 b | 17.0 d |

| 2023 | 1.34 a | 3.36 a | 24.8 a |

| Metric | n | Correlation | t-test (p-value) |

KS test (p-value) |

MAE (normalized to the range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clusters per vine | train=350; test=88 |

66.82 | t = -0.127 (p = 0.899) |

D = 0.136 (p = 0.387) |

11.45 (14.49%) |

| Yield (ton ha-1) | train=372; test=94 |

62.16 | t = -0.069 (p = 0.945) |

D = 0.17 (p = 0.131) |

40.3 (13.82%) |

| Cluster weight (g) | train=370; test=92 |

39.46 | t = -0.101 (p = 0.92) |

D = 0.239 (p = 0.01) |

22.5 (17.5%) |

| Canes per vine | train=256; test=64 |

8.69 | t = -0.211 (p = 0.833) |

D = 0.185 (p = 0.211) |

5.72 (18.46%) |

| Pruning weight (Kg) | train=319; test=80 |

52.66 | t = 0.529 (p = 0.598) |

D = 0.162 (p = 0.241) |

0.346 (16.47%) |

| Cane weight (g) | train=265; test=68 |

53.95 | t = 1.408 (p = 0.162) |

D = 0.235 (p = 0.05) |

10.1 (15.81%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).