Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

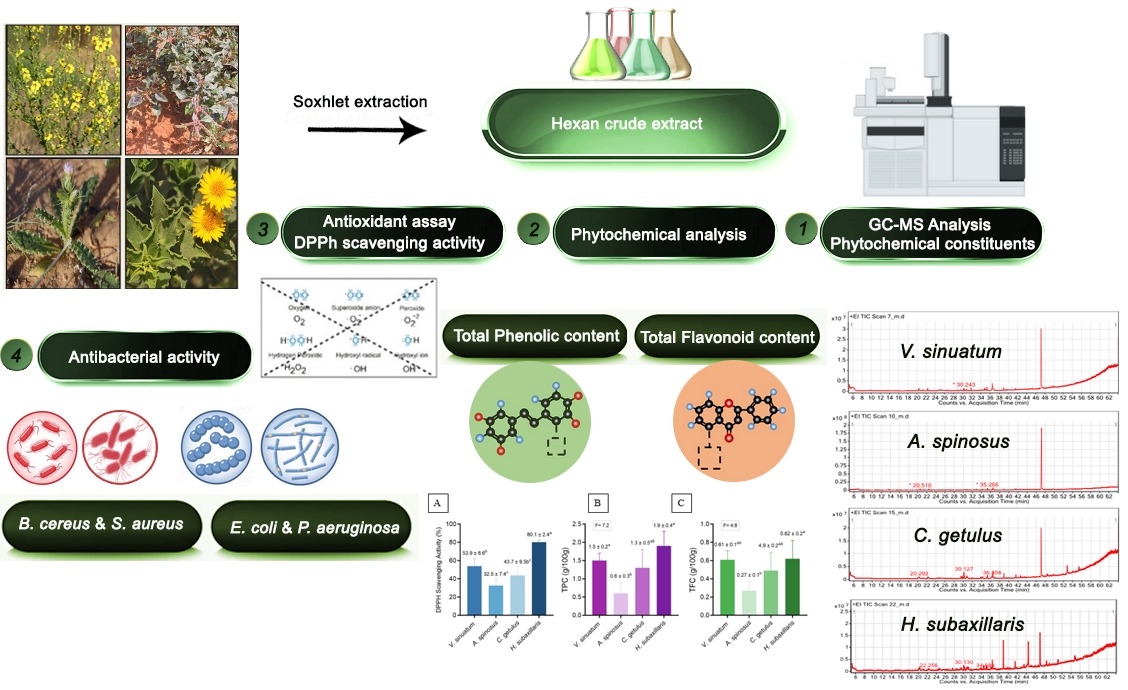

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

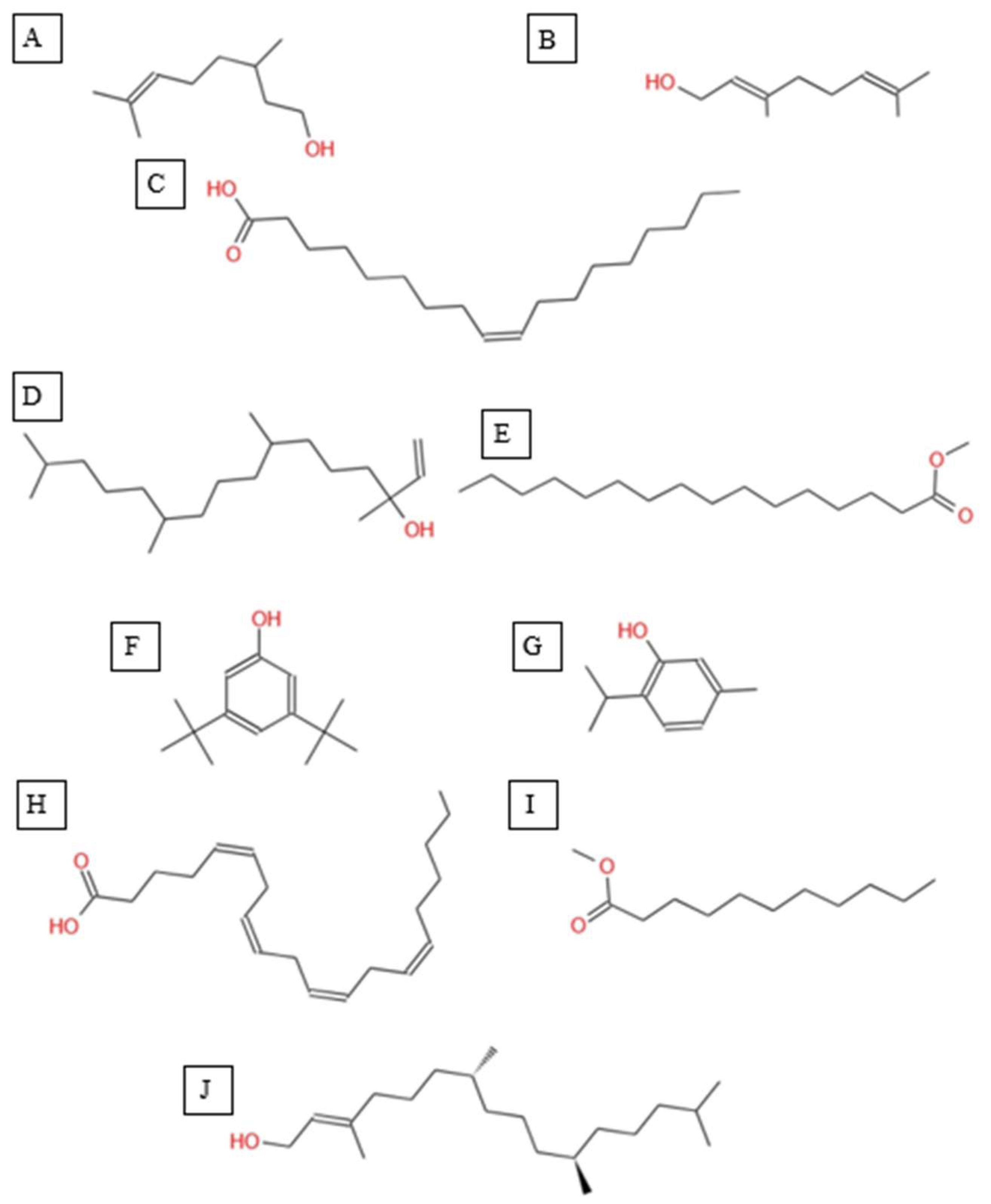

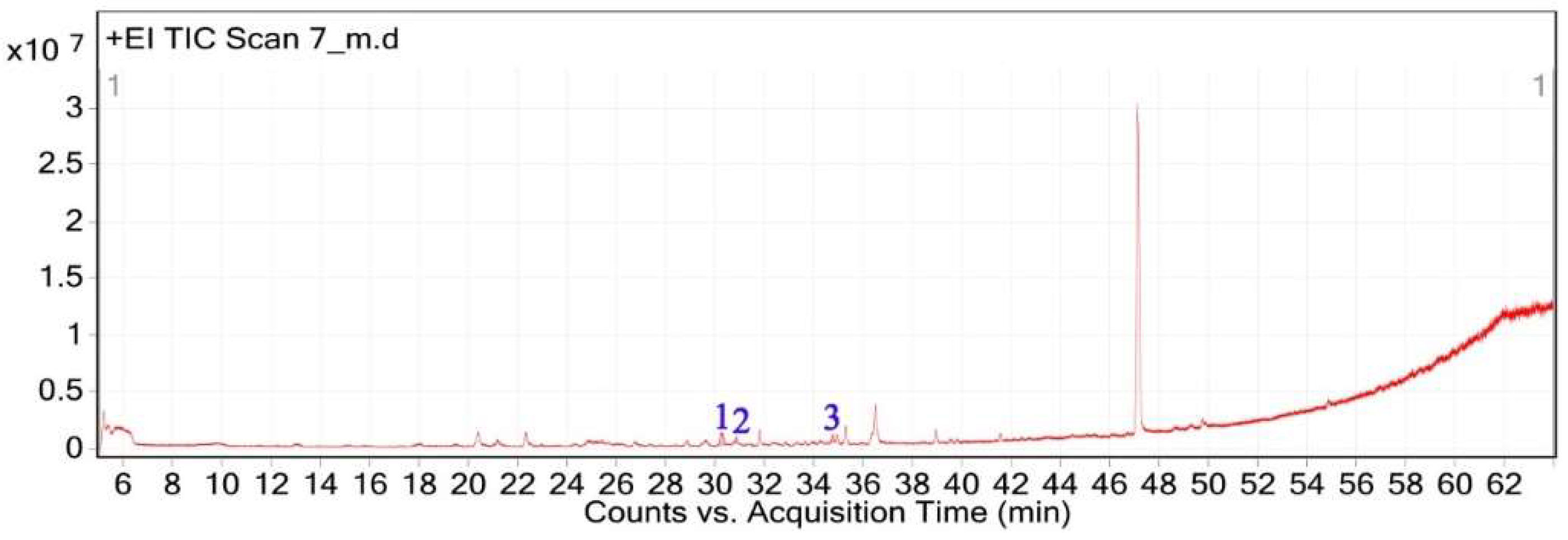

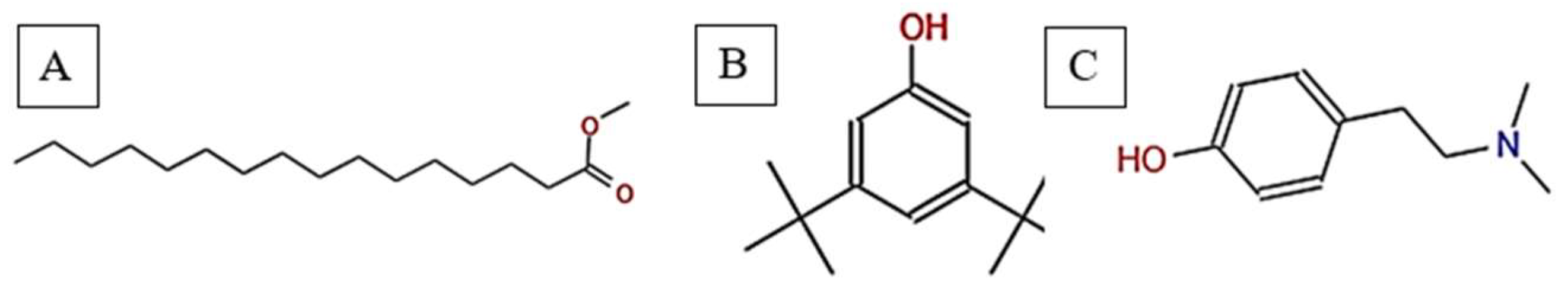

2.1. GC-MS and Phytochemical Profiling of V. sinuatum

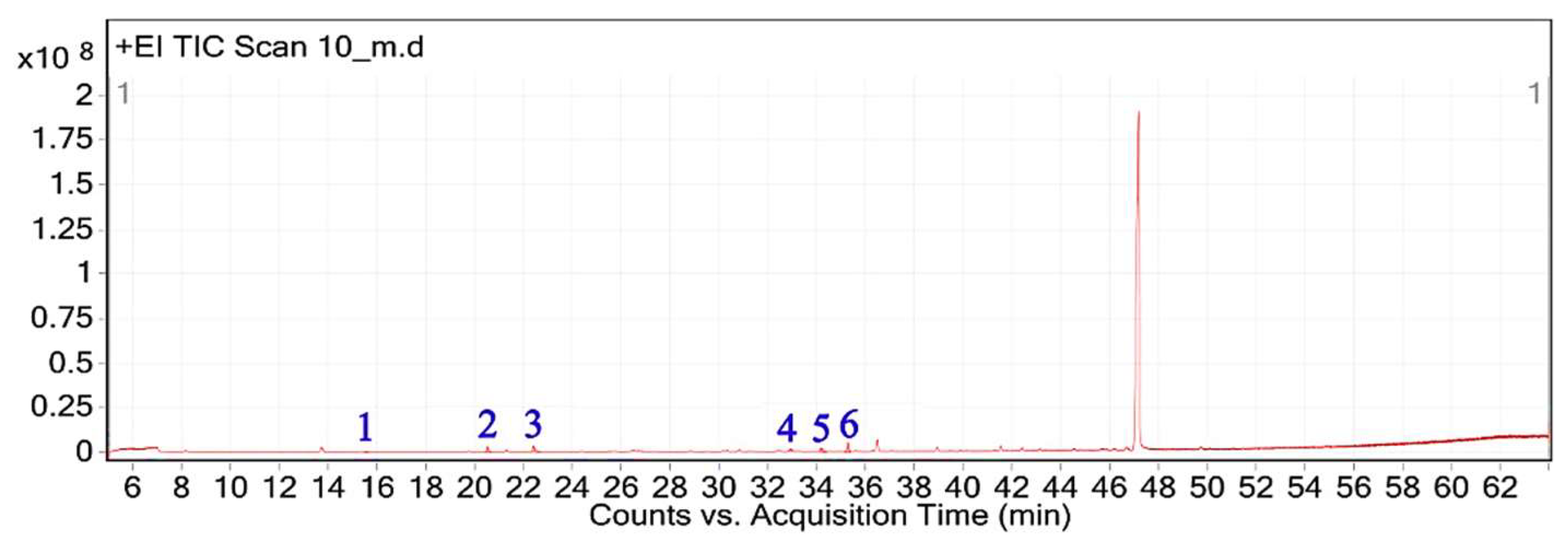

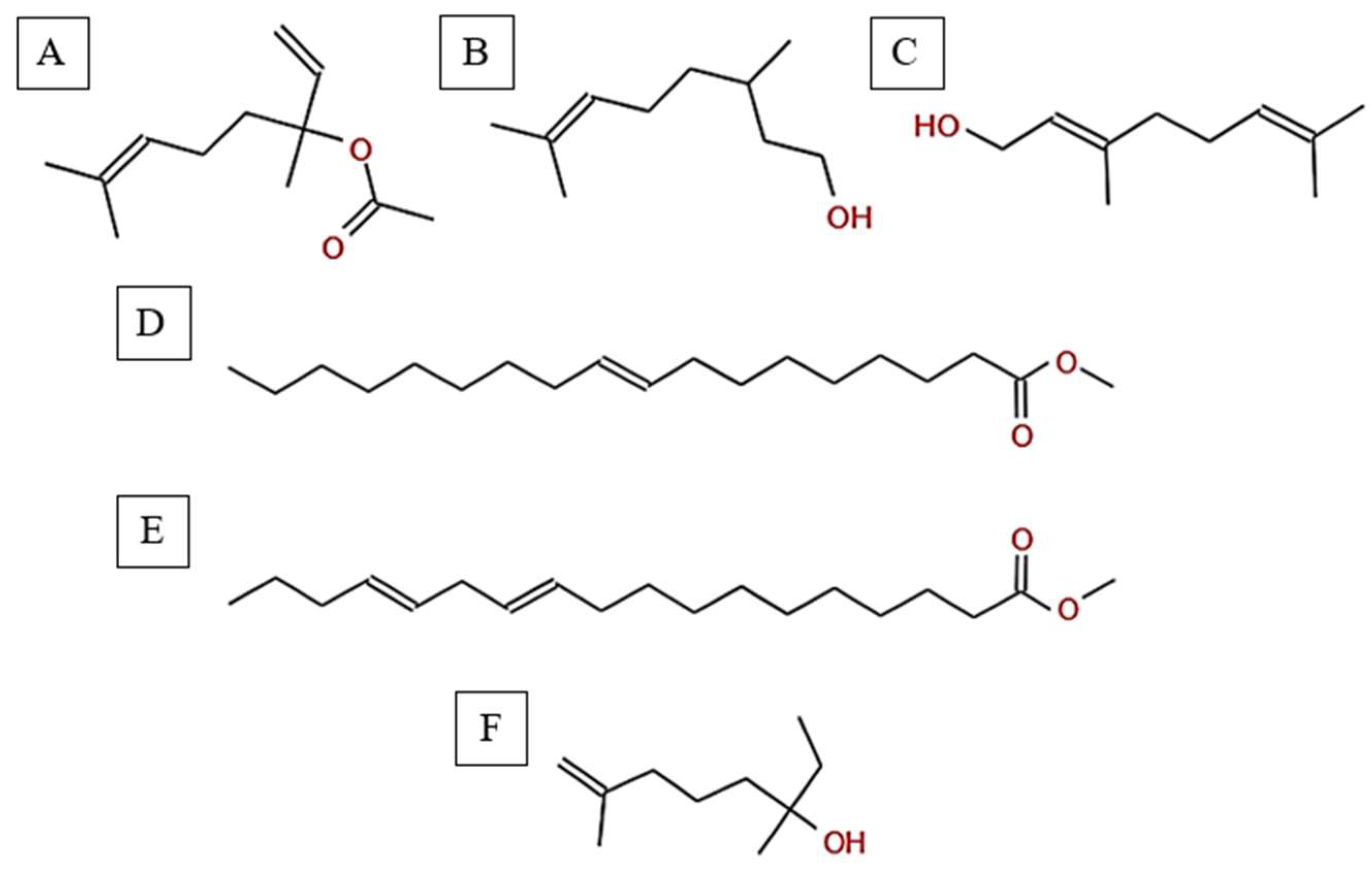

2.2. GC-MS and Phytochemical Profiling of A. spinosus

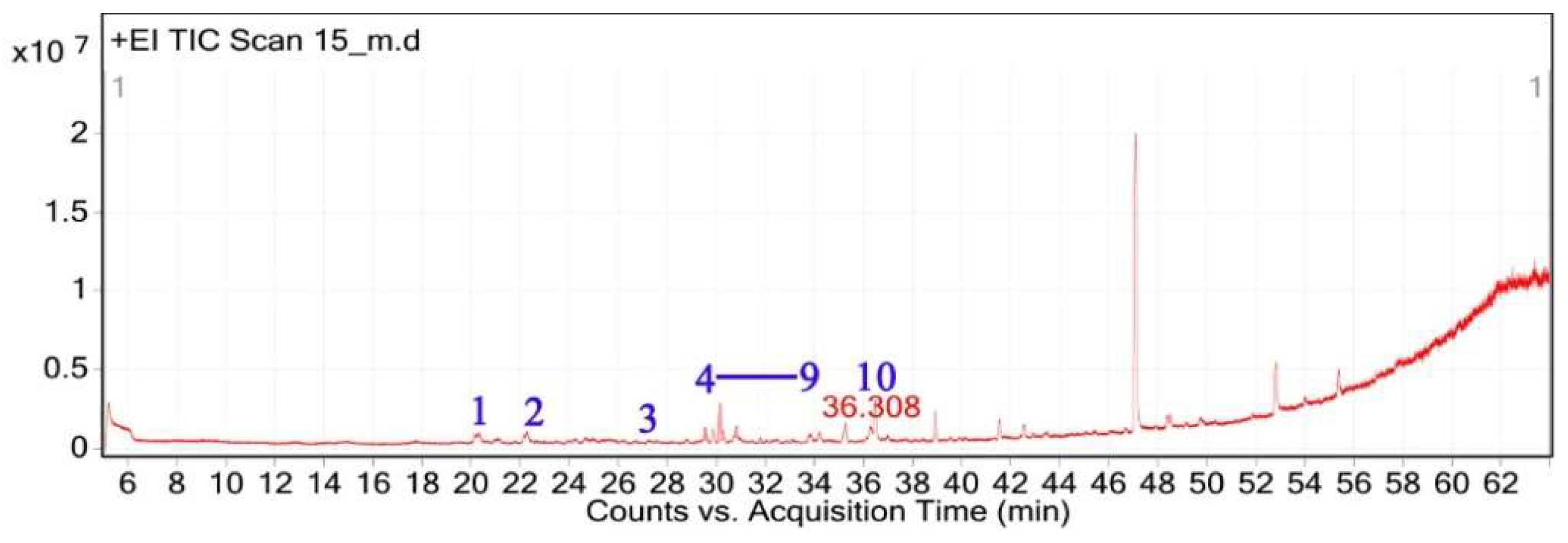

2.3. GC-MS and Phytochemical Profiling of C. getulus

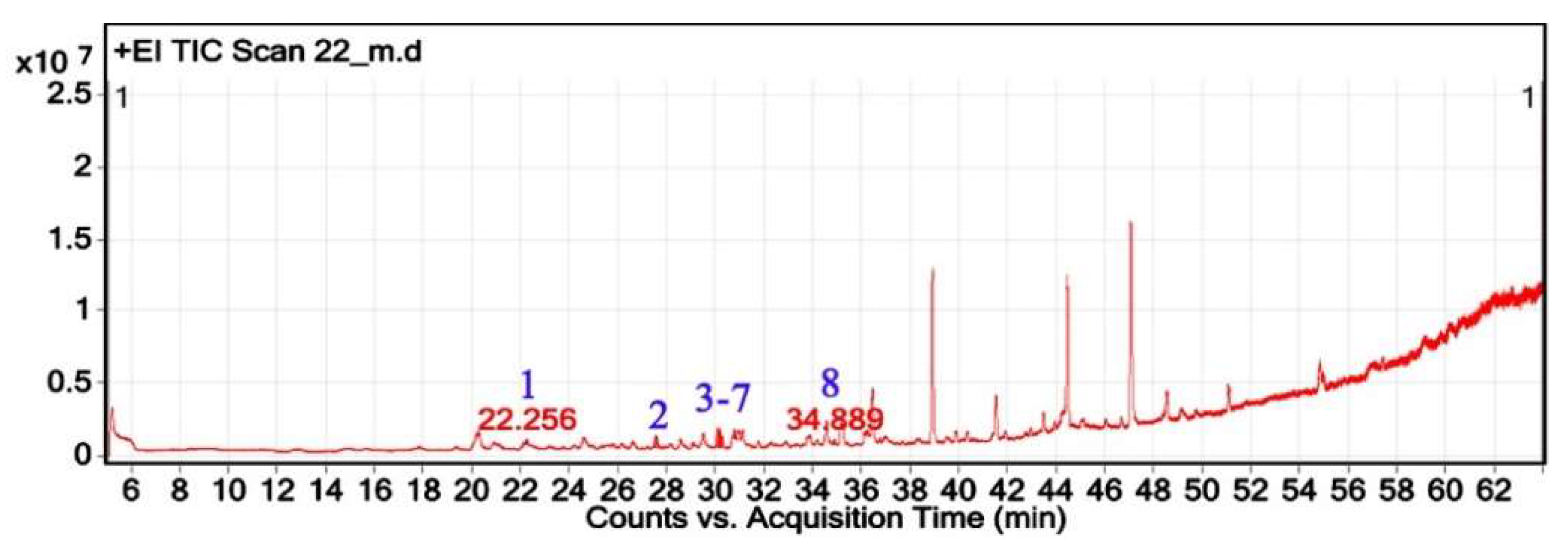

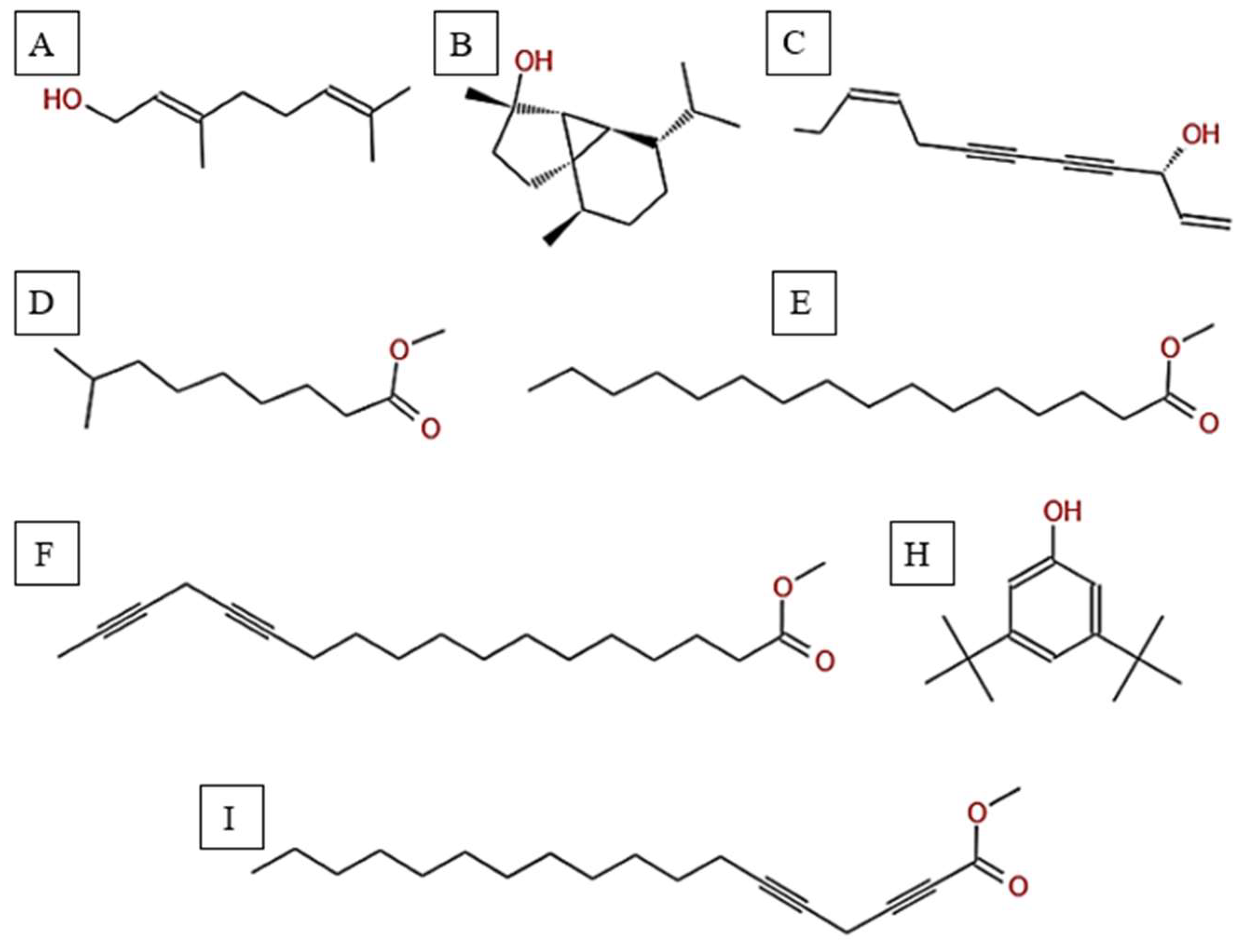

2.4. GC-MS and Phytochemical Profiling of H. subaxillaris

2.5. Antibacterial Activity Analysis

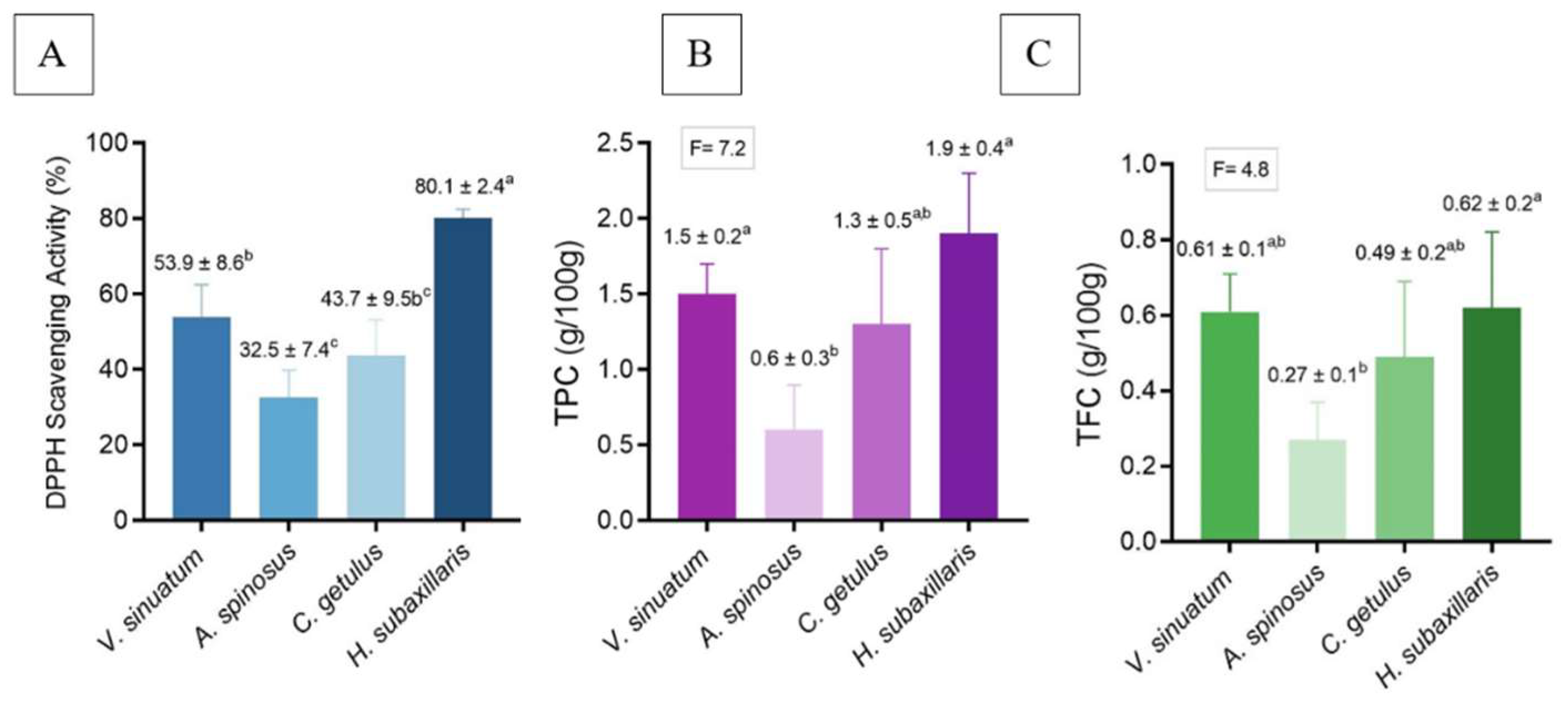

2.6. Assessment of Antioxidant Capacities in Plant Extracts

2.7. Total Phenolics Content

2.8. Total Flavonoids Content

3. Discussion

3.1. GC-MS Analysis and Phytochemical Characterization

3.2. Comparative Phytochemical and Pharmacological Profiling of Four Medicinal Plant Species

3.3. Total Phenolics Content and Total Flavonoids Content

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

3.5. Antimicrobial Activity

4. Materials and Methods

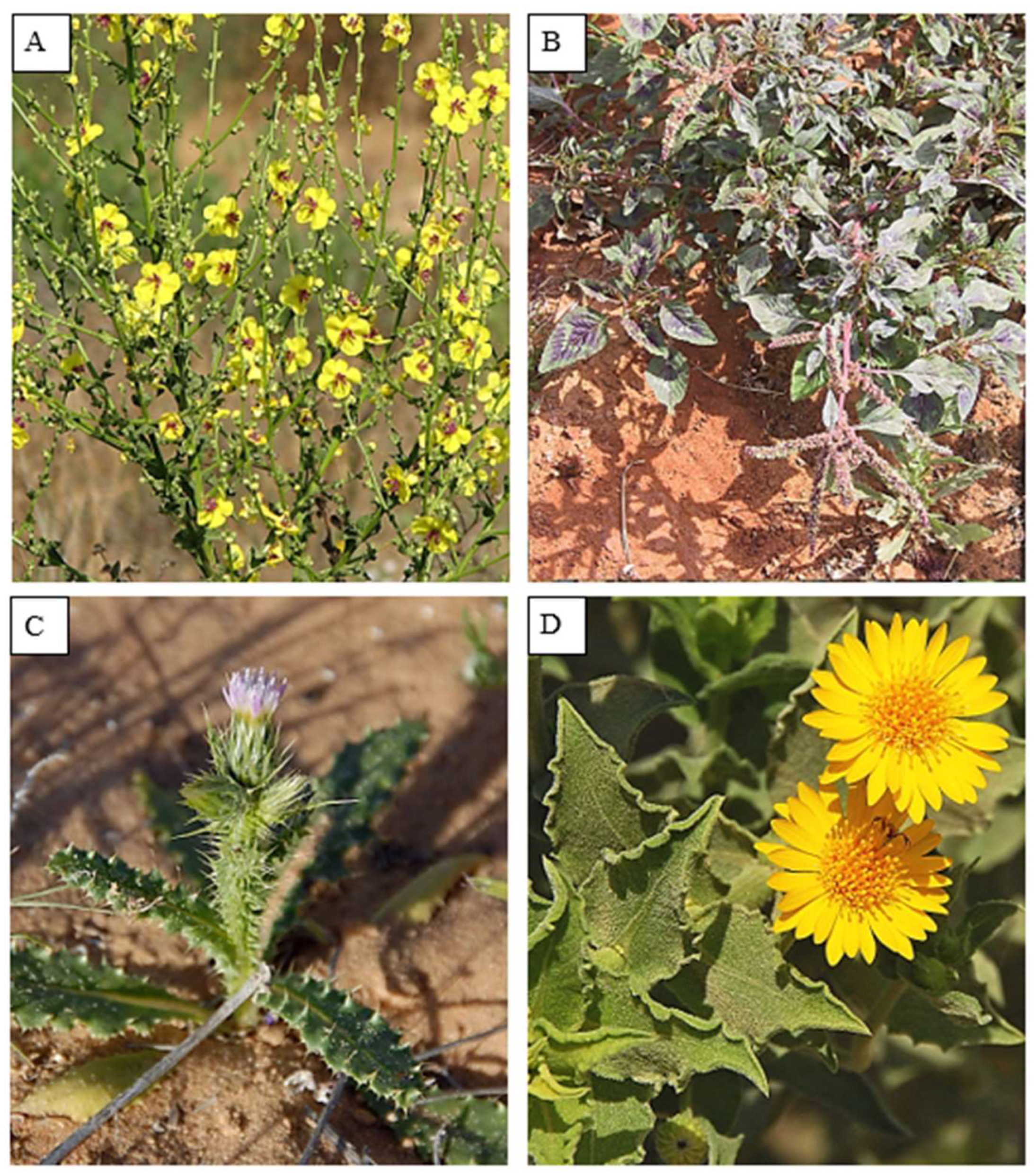

4.1. Collection and Identification of Plant Material

4.2. Extraction of Plant Material

4.3. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis

4.4. Analysis and Characterization of Compounds of Plant Extracts

4.5. Measurement of Total Phenolic Content

4.6. Measurement of Total Flavonoid Content

4.7. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

4.8. Measurement of Antimicrobial Activity

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dubale, S.; Kebebe, D.; Zeynudin, A.; Abdissa, N.; Suleman, S. Phytochemical Screening and Antimicrobial Activity Evaluation of Selected Medicinal Plants in Ethiopia. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2023, 15, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selseleh, M.; Nejad Ebrahimi, S.; Aliahmadi, A.; Sonboli, A.; Mirjalili, M.H. Metabolic profiling, antioxidant, and antibacterial activity of some Iranian Verbascum L. species. Industrial Crops and Products 2020, 153, 112609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donn, P.; Barciela, P.; Perez-Vazquez, A.; Cassani, L.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A. Bioactive Compounds of Verbascum sinuatum L.: Health Benefits and Potential as New Ingredients for Industrial Applications. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruth, O.N.; Unathi, K.; Nomali, N.; Chinsamy, M. Underutilization Versus Nutritional-Nutraceutical Potential of the Amaranthus Food Plant: A Mini-Review. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbola, P.I.; Adetutu, A.; Olaniyi, T.D. Antioxidant activity of Amaranthus species from the Amaranthaceae family – A review. South African Journal of Botany 2020, 133, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamuru, S.; Kaigamma, I.; Muluh, E. Preliminary Phytochemical Screening and GC-MS Analysis of Aqueous and Ethanolic Extracts of Amaranthus spinosus Leaves. Journal of Natural Products and Resources 2019, 5, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Auda, M. Phytochemical and proximate analysis of wild plants from the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, W.; Larrauri, M.; Gomez-Lopez, C.; DiLorenzo, N. Invasive Pigweed (Amaranthus spinosus) as a Potential Source of Plant Secondary Metabolites to Mitigate Enteric Methane Emissions in Beef Cattle. Grasses 2025, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari, L.A.; Hassan, W.H.B.; Al-Youssef, H.M. Phytochemical and biological studies of Carduus pycnocephalus L. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2015, 19, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Auda, M. Taxonomical knowledge, biological spectra and ethnomedicinal plant inventory of Asteraceae family in various areas of Gaza strip, Palestine. Pak. J. Bot 2023, 55, 2369–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, M.; Cantrell, C.L.; Libous-Bailey, L.; Duke, S.O. Phytotoxicity of constituents of glandular trichomes and the leaf surface of camphorweed, Heterotheca subaxillaris. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasekar, R.; Thanasamy, R.; Samuel, M.; Edison, T.N.J.I.; Raman, N. Ecofriendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Heterotheca subaxillaris flower and its catalytic performance on reduction of methyl orange. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 187, 108447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, M. From America to the Holy Land: disentangling plant traits of the invasive Heterotheca subaxillaris (Lam.) Britton & Rusby. Plant Ecology 2016, 217, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbois, A.P.; Smith, V.J. Antibacterial free fatty acids: activities, mechanisms of action and biotechnological potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 1629–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, K.; Subramaniam, P. Phytochemical Profiling of Leaf, Stem, and Tuber Parts of Solena amplexicaulis (Lam.) Gandhi Using GC-MS. Int Sch Res Notices 2014, 2014, 567409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M.T.; Ghaly, M.F.; Fahmi, S.M. Antibacterial activities of hexadecanoic acid methyl ester and green-synthesized silver nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J. Basic Microbiol. 2021, 61, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.M.H.; Park, K. Applications of Tert-Butyl-Phenolic Antioxidants in Consumer Products and Their Potential Toxicities in Humans. Toxics 2024, 12, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, K.; MuhilVannan, S. 3, 5-Di-tert-butylphenol combat against Streptococcus mutans by impeding acidogenicity, acidurance and biofilm formation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartikova, H.; Hanusova, V.; Skalova, L.; Ambroz, M.; Bousova, I. Antioxidant, pro-oxidant and other biological activities of sesquiterpenes. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 2478–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiege, H.; Voges, H.W.; Hamamoto, T.; Umemura, S.; Iwata, T.; Miki, H.; Fujita, Y.; Buysch, H.J.; Garbe, D.; Paulus, W. Phenol derivatives. Ullmann's encyclopedia of industrial chemistry, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, D.; Hu, G.; Wang, H.; Ye, B.; He, Y.; Gao, X.; Liu, D. Hordenine inhibits neuroinflammation and exerts neuroprotective effects via inhibiting NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways in vivo and in vitro. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 108, 108694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Du, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Lv, X. Hordenine protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting inflammation. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 712232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-C.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, M.-H.; Lee, J.-A.; Kim, Y.B.; Jung, E.; Kim, Y.-S.; Lee, J.; Park, D. Hordenine, a single compound produced during barley germination, inhibits melanogenesis in human melanocytes. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Ding, C.; Wen, F.; Sun, F.; Liu, Y.; Tao, C.; Yao, J. Beneficial Effects of Hordenine on a Model of Ulcerative Colitis. Molecules 2023, 28, 2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamwal, K.; Bhattacharya, S.; Puri, S. Plant growth regulator mediated consequences of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. Journal of Applied Research on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants 2018, 9, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.J.; Zheng, B. The Role of Polyphenols in Abiotic Stress Tolerance and Their Antioxidant Properties to Scavenge Reactive Oxygen Species and Free Radicals. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Jiang, C.; Chen, L.; Paul, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Shen, G. Achieving abiotic stress tolerance in plants through antioxidative defense mechanisms. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1110622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipel, T.; Alexander, J.M.; Daehler, C.C.; Rew, L.J.; Edwards, P.J.; Dar, P.A.; McDougall, K.; Naylor, B.; Parks, C.; Pollnac, F.W. Performance of the herb Verbascum thapsus along environmental gradients in its native and non-native ranges. J. Biogeogr. 2015, 42, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, M.I.; Ali, K.; Alipieva, K.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Metabolic differentiations and classification of Verbascum species by NMR-based metabolomics. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 2045–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, N.; Anmol, A.; Kumar, S.; Wani, A.W.; Bakshi, M.; Dhiman, Z. Exploring phenolic compounds as natural stress alleviators in plants- a comprehensive review. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 133, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraj, R.L.; Azimullah, S.; Parekh, K.A.; Ojha, S.K.; Beiram, R. Effect of citronellol on oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and autophagy pathways in an in vivo model of Parkinson's disease. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Viljoen, A.M. Geraniol – A review update. South African Journal of Botany 2022, 150, 1205–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peana, A.T.; D'Aquila, P.S.; Panin, F.; Serra, G.; Pippia, P.; Moretti, M.D.L. Anti-inflammatory activity of linalool and linalyl acetate constituents of essential oils. Phytomedicine 2002, 9, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembitsky, V.M.; Shkrob, I.; Rozentsvet, O.A. Fatty acid amides from freshwater green alga Rhizoclonium hieroglyphicum. Phytochemistry 2000, 54, 965–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javan, A.J.; Javan, M.J. Electronic structure of some thymol derivatives correlated with the radical scavenging activity: Theoretical study. Food Chem. 2014, 165, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tlais, A.Z.A.; Rantsiou, K.; Filannino, P.; Cocolin, L.S.; Cavoski, I.; Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R. Ecological linkages between biotechnologically relevant autochthonous microorganisms and phenolic compounds in sugar apple fruit (Annona squamosa L.). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 387, 110057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sytar, O.; Hemmerich, I.; Zivcak, M.; Rauh, C.; Brestic, M. Comparative analysis of bioactive phenolic compounds composition from 26 medicinal plants. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasmi, S.; Hamdi, A.; Atmani-Kilani, D.; Debbache-Benaida, N.; Jaramillo-Carmona, S.; Rodríguez-Arcos, R.; Jiménez-Araujo, A.; Ayouni, K.; Atmani, D.; Guillén-Bejarano, R. Characterization of phenolic compounds isolated from the Fraxinus angustifolia plant and several associated bioactivities. Journal of Herbal Medicine 2021, 29, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Shah, M.D.; Gnanaraj, C.; Iqbal, M. In vitro total phenolics, flavonoids contents and antioxidant activity of essential oil, various organic extracts from the leaves of tropical medicinal plant Tetrastigma from Sabah. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2011, 4, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadie, A.; Dakone, D.; Unbushe, D.; Wang, A.; Xia, S. Antibacterial activity of selected medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Genta Meyche (Southern Ethiopia) for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. Journal of Herbal Medicine 2020, 22, 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, K.R.; Le, T.C.; Chintakunta, P.K.; Lakshman, D.K. Phyto-fungicides: Structure activity relationships of the thymol derivatives against Rhizoctonia solani. Journal of Agricultural Chemistry and Environment 2017, 6, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Tong, Y.; Hu, Y. Discovery of a novel series of α-terpineol derivatives as promising anti-asthmatic agents: Their design, synthesis, and biological evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niinemets, Ü.; Monson, R.K. Biology, controls and models of tree volatile organic compound emissions. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, B.M. The evolution of plant secretory structures and emergence of terpenoid chemical diversity. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudt, M.; Lhoutellier, L. Volatile organic compound emission from holm oak infested by gypsy moth larvae: evidence for distinct responses in damaged and undamaged leaves. Tree physiology 2007, 27, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yore, Mark M.; Syed, I.; Moraes-Vieira, Pedro M.; Zhang, T.; Herman, Mark A.; Homan, Edwin A.; Patel, Rajesh T.; Lee, J.; Chen, S.; Peroni, Odile D.; et al. Discovery of a Class of Endogenous Mammalian Lipids with Anti-Diabetic and Anti-inflammatory Effects. Cell 2014, 159, 318–332. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Santoro, A.; Hofer, P.; Tan, D.; Oberer, M.; Nelson, A.T.; Konduri, S.; Siegel, D.; Zechner, R.; Saghatelian, A.; et al. ATGL is a biosynthetic enzyme for fatty acid esters of hydroxy fatty acids. Nature 2022, 606, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riecan, M.; Paluchova, V.; Lopes, M.; Brejchova, K.; Kuda, O. Branched and linear fatty acid esters of hydroxy fatty acids (FAHFA) relevant to human health. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 231, 107972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, I.; Lee, J.; Moraes-Vieira, P.M.; Donaldson, C.J.; Sontheimer, A.; Aryal, P.; Wellenstein, K.; Kolar, M.J.; Nelson, A.T.; Siegel, D.; et al. Palmitic Acid Hydroxystearic Acids Activate GPR40, Which Is Involved in Their Beneficial Effects on Glucose Homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 419–427.e414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muoio, D.M.; Newgard, C.B. The good in fat. Nature 2014, 516, 49–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes-Vieira, P.M.; Saghatelian, A.; Kahn, B.B. GLUT4 expression in adipocytes regulates de novo lipogenesis and levels of a novel class of lipids with antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory effects. Diabetes 2016, 65, 1808–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, I.; de Celis, M.F.R.; Mohan, J.F.; Moraes-Vieira, P.M.; Vijayakumar, A.; Nelson, A.T.; Siegel, D.; Saghatelian, A.; Mathis, D.; Kahn, B.B. PAHSAs attenuate immune responses and promote β cell survival in autoimmune diabetic mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 2019, 129, 3717–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.P.; Guijas, C.; Astudillo, A.M.; Rubio, J.M.; Balboa, M.A.; Balsinde, J. Sequestration of 9-Hydroxystearic Acid in FAHFA (Fatty Acid Esters of Hydroxy Fatty Acids) as a Protective Mechanism for Colon Carcinoma Cells to Avoid Apoptotic Cell Death. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.-F.; Yan, J.-W.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.-W.; Yuan, B.-F.; Feng, Y.-Q. Highly sensitive determination of fatty acid esters of hydroxyl fatty acids by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography B 2017, 1061-1062, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, M.J.; Konduri, S.; Chang, T.; Wang, H.; McNerlin, C.; Ohlsson, L.; Härröd, M.; Siegel, D.; Saghatelian, A. Linoleic acid esters of hydroxy linoleic acids are anti-inflammatory lipids found in plants and mammals. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 10698–10707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dongoran, R.A.; Lin, T.-J.; Byekyet, A.; Tang, S.-C.; Yang, J.-H.; Liu, C.-H. Determination of Major Endogenous FAHFAs in Healthy Human Circulation: The Correlations with Several Circulating Cardiovascular-Related Biomarkers and Anti-Inflammatory Effects on RAW 264.7 Cells. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benlebna, M.; Balas, L.; Bonafos, B.; Pessemesse, L.; Fouret, G.; Vigor, C.; Gaillet, S.; Grober, J.; Bernex, F.; Landrier, J.-F.; et al. Long-term intake of 9-PAHPA or 9-OAHPA modulates favorably the basal metabolism and exerts an insulin sensitizing effect in obesogenic diet-fed mice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2013–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defour, M.; van Weeghel, M.; Hermans, J.; Kersten, S. Hepatic ADTRP overexpression does not influence lipid and glucose metabolism. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2021, 321, C585–C595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minto, R.E.; Blacklock, B.J. Biosynthesis and function of polyacetylenes and allied natural products. Prog. Lipid Res. 2008, 47, 233–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, J.W.; Green, T.; Phillips, P.J. Metabolism of the phenolic antioxidant 3,5-Di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyanisole (Topanol 354). II. Biotransformation in man, rat and dog. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 1973, 11, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seigler, D.S. Acetylenic Compounds. In Plant Secondary Metabolism, Seigler, D.S., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1998; pp. 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Viljoen, A.M. Geraniol — A review of a commercially important fragrance material. South African Journal of Botany 2010, 76, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avato, P.; Vitali, C.; Mongelli, P.; Tava, A. Antimicrobial activity of polyacetylenes from Bellis perennis and their synthetic derivatives. Planta Med. 1997, 63, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Liu, Y. Terpenoids: Natural Compounds for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Therapy. Molecules 2023, 28, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabalak, E.; Ibrahim, F.; Eliuz, E.A.E.; Everest, A.; Gizir, A.M. Evaluation of chemical composition, trace element content, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Verbascum pseudoholotrichum. Plant Biosystems-An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology 2022, 156, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyra, M.; Komsta, Ł.; Wojtanowski, K. Analysis of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of methanolic extracts from inflorescences of Carduus sp. Phytochemistry Letters 2019, 31, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supritha, P.; Radha, K.V. Estimation of phenolic compounds present in the plant extracts using high pressure liquid chromatography, antioxidant properties and its antibacterial activity. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Education and Research 2018, 52, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M.H. Therapeutic Potential of Phenolic Compounds in Medicinal Plants—Natural Health Products for Human Health. Molecules 2023, 28, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Oh, Y.J.; Lim, J.; Youn, M.; Lee, I.; Pak, H.K.; Park, W.; Jo, W.; Park, S. AFM study of the differential inhibitory effects of the green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Food Microbiol. 2012, 29, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathima, A.; Rao, J.R. Selective toxicity of Catechin—a natural flavonoid towards bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 6395–6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiko, A.G.; Sekowski, S.; Lapshina, E.A.; Wilczewska, A.Z.; Markiewicz, K.H.; Zamaraeva, M.; Zhao, H.-c.; Zavodnik, I.B. Flavonoids modulate liposomal membrane structure, regulate mitochondrial membrane permeability and prevent erythrocyte oxidative damage. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2020, 1862, 183442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutha, R.E.; Tatiya, A.U.; Surana, S.J. Flavonoids as natural phenolic compounds and their role in therapeutics: an overview. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2021, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verri, W.A.; Vicentini, F.T.M.C.; Baracat, M.M.; Georgetti, S.R.; Cardoso, R.D.R.; Cunha, T.M.; Ferreira, S.H.; Cunha, F.Q.; Fonseca, M.J.V.; Casagrande, R. Chapter 9 - Flavonoids as Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Drugs: Mechanisms of Action and Perspectives in the Development of Pharmaceutical Forms. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, Atta ur, R., Ed.; Elsevier: 2012; Volume 36, pp. 297-330.

- Patil, V.M.; Masand, N. Chapter 12 - Anticancer Potential of Flavonoids: Chemistry, Biological Activities, and Future Perspectives. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, Atta ur, R., Ed.; Elsevier: 2018; Volume 59, pp. 401-430.

- Muhaisen, H.M. Introduction and interpretation of flavonoids. Advanced Science, Engineering and Medicine 2014, 6, 1235–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajuria, R.; Singh, S.; Bahl, A. General introduction and sources of flavonoids. Current aspects of flavonoids: Their role in cancer treatment, -7. [CrossRef]

- Lobiuc, A.; Pavăl, N.-E.; Mangalagiu, I.I.; Gheorghiță, R.; Teliban, G.-C.; Amăriucăi-Mantu, D.; Stoleru, V. Future Antimicrobials: Natural and Functionalized Phenolics. Molecules 2023, 28, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, Z.K.; Saggu, S.; Sakeran, M.I.; Zidan, N.; Rehman, H.; Ansari, A.A. Phytochemical, antioxidant and mineral composition of hydroalcoholic extract of chicory (Cichorium intybus L.) leaves. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Hossain, A.S.M.S.; Mostofa, M.G.; Khan, M.A.; Ali, R.; Mosaddik, A.; Sadik, M.G.; Alam, A.H.M.K. Evaluation of anti-ROS and anticancer properties of Tabebuia pallida L. Leaves. Clinical Phytoscience 2019, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.M.; Abo-Shady, A.; Sharaf Eldeen, H.A.; Soror, H.A.; Shousha, W.G.; Abdel-Barry, O.A.; Saleh, A.M. Structural features, kinetics and SAR study of radical scavenging and antioxidant activities of phenolic and anilinic compounds. Chem. Cent. J. 2013, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Lucardi, R.D.; Su, Z.; Li, S. Natural Sources and Bioactivities of 2,4-Di-Tert-Butylphenol and Its Analogs. Toxins (Basel) 2020, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofa, M.G.; Reza, A.; Khan, Z.; Munira, M.S.; Khatoon, M.M.; Kabir, S.R.; Sadik, M.G.; Ağagündüz, D.; Capasso, R.; Kazi, M.; et al. Apoptosis-inducing anti-proliferative and quantitative phytochemical profiling with in silico study of antioxidant-rich Leea aequata L. leaves. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Cheng, W.; Tian, M.; Wu, Z.; Wei, X.; Cheng, X.; Yang, M.; Ma, X. Antioxidant Activity and Volatile Oil Analysis of Ethanol Extract of Phoebe zhennan S. Lee et F. N. Wei Leaves. Forests 2024, 15, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medbouhi, A.; Merad, N.; Khadir, A.; Bendahou, M.; Djabou, N.; Costa, J.; Muselli, A. Chemical composition and biological investigations of Eryngium triquetrum essential oil from Algeria. Chem. Biodivers. 2018, 15, e1700343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tel-Çayan, G.; Duru, M.E. Chemical characterization and antioxidant activity of Eryngium pseudothoriifolium and E. thorifolium essential oils. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viuda-Martos, M.; López-Marcos, M.; Fernández-López, J.; Sendra, E.; López-Vargas, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, J. Role of fiber in cardiovascular diseases: a review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 9: 240–258. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharififar, F.; Dehghn-Nudeh, G.; Mirtajaldini, M. Major flavonoids with antioxidant activity from Teucrium polium L. Food Chem. 2009, 112, 885–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.A.; Khan, M.R.; Sahreen, S.; Ahmed, M. Assessment of flavonoids contents and in vitro antioxidant activity of Launaea procumbens. Chem. Cent. J. 2012, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benramdane, E.; Chougui, N.; Ramos, P.A.B.; Makhloufi, N.; Tamendjari, A.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Santos, S.A.O. Lipophilic Compounds and Antibacterial Activity of Opuntia ficus-indica Root Extracts from Algeria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydın Kurç, M.; Orak, H.H.; Gülen, D.; Caliskan, H.; Argon, M.; Sabudak, T. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Efficacy of the Lipophilic Extract of Cirsium vulgare. Molecules 2023, 28, 7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeri, R.; Parafati, L.; Arena, E.; Grassenio, E.; Restuccia, C.; Fallico, B. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Semi-Processed Frozen Prickly Pear Juice as Affected by Cultivar and Harvest Time. Foods 2020, 9, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jubair, N.; Rajagopal, M.; Chinnappan, S.; Abdullah, N.B.; Fatima, A. Review on the antibacterial mechanism of plant-derived compounds against multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDR). Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2021, 2021, 3663315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorusso, A.B.; Carrara, J.A.; Barroso, C.D.N.; Tuon, F.F.; Faoro, H. Role of Efflux Pumps on Antimicrobial Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuon, F.F.; Dantas, L.R.; Suss, P.H.; Tasca Ribeiro, V.S. Pathogenesis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm: A Review. Pathogens 2022, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirani, Z.A.; Naz, S.; Khan, F.; Aziz, M.; Asadullah; Khan, M.N.; Khan, S.I. Antibacterial fatty acids destabilize hydrophobic and multicellular aggregates of biofilm in S. aureus. The Journal of Antibiotics 2017, 70, 115–121. [CrossRef]

- Alves, E.; Dias, M.; Lopes, D.; Almeida, A.; Domingues, M.d.R.; Rey, F. Antimicrobial Lipids from Plants and Marine Organisms: An Overview of the Current State-of-the-Art and Future Prospects. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartron, M.L.; England, S.R.; Chiriac, A.I.; Josten, M.; Turner, R.; Rauter, Y.; Hurd, A.; Sahl, H.G.; Jones, S.; Foster, S.J. Bactericidal activity of the human skin fatty acid cis-6-hexadecanoic acid on Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3599–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D.L.B. , Lloyd B. Antimicrobial activity of sucrose fatty acid ester emulsifiers. J. Food Sci. 1986, 51, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikkema, J.; de Bont, J.A.; Poolman, B. Interactions of cyclic hydrocarbons with biological membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 8022–8028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikkema, J.; de Bont, J.A.; Poolman, B. Mechanisms of membrane toxicity of hydrocarbons. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 59, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helander, I.M.; Alakomi, H.-L.; Latva-Kala, K.; Mattila-Sandholm, T.; Pol, I.; Smid, E.J.; Gorris, L.G.; von Wright, A. Characterization of the action of selected essential oil components on Gram-negative bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 3590–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Song, X.; Li, H.; Zhu, L.; Cao, S.; Liu, J. Sesquiterpenes and Monoterpenes from the Leaves and Stems of Illicium simonsii and Their Antibacterial Activity. Molecules 2022, 27, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rossi, L.; Rocchetti, G.; Lucini, L.; Rebecchi, A. Antimicrobial Potential of Polyphenols: Mechanisms of Action and Microbial Responses—A Narrative Review. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, D.; Castelli, F.; Sarpietro, M.G.; Venuti, V.; Cristani, M.; Daniele, C.; Saija, A.; Mazzanti, G.; Bisignano, G. Mechanisms of antibacterial action of three monoterpenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2474–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatore, F.; Rigano, D.; Formisano, C.; Grassia, A.; Basile, A.; Sorbo, S. Phytogrowth-inhibitory and antibacterial activity of Verbascum sinuatum. Fitoterapia 2007, 78, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.Y.; Yunus, M.A.C.; Idham, Z.; Ruslan, M.S.H.; Aziz, A.H.A.; Irwansyah, N. Extraction and identification of bioactive compounds from agarwood leaves. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2016, 162, 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezhilan, B.P.; Neelamegam, R. GC-MS analysis of phytocomponents in the ethanol extract of Polygonum chinense L. Pharmacognosy Res. 2012, 4, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. American journal of Enology and Viticulture 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhishen, J.; Mengcheng, T.; Jianming, W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, T.J.; Mozumder, H.A.; Ali, F.; Akther, K. Inhibition of pathogenic microbes by the lactic acid bacteria Limosilactobacillus fermentum strain LAB-1 and Levilactobacillus brevis strain LAB-5 isolated from the dairy beverage borhani. Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science 2022, 10, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Peak No. | RT (min) | Area (%) | Chemical Compounds | MF | MW (g/mol) | Key m/z | Match score | Phytochemical Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30.243 | 65.90 | Methyl palmitate | C₁₇H₃₄O₂ | 270.45 | 74.02 | 71.0 | Saturated fatty acid ester |

| 2 | 30.840 | 13.34 | 3,5-ditert-butylphenol | C₁₄H₂₂O | 206.32 | 190.57 | 75.6 | Phenolic antioxidant |

| 3 | 34.752 | 20.76 | Hordenine | C₁₀H₁₅NO | 165.23 | 190.57 | 75.6 | Alkaloid (phenethylamine) |

| Peak No. | RT (min) | Area (%) |

Chemical Compounds | MF | MW (g/mol) | Key m/z | Match score | Phytochemical Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15.526 | 3.03 | Linalyl acetate | C₁₂H₂₀O₂ | 196.29 | 71.01 | 72.8 | Monoterpene ester |

| 2 | 20.51 | 17.59 | Citronellol | C₁₀H₂₀O | 156.27 | 69.01 | 76.7 | Monoterpenoid alcohol |

| 3 | 22.395 | 17.34 | Geraniol | C₁₀H₁₈O | 154.25 | 92.88 | 81.4 | Monoterpenoid alcohol |

| 4 | 32.923 | 9.51 | Methyl elaidate | C₁₉H₃₆O₂ | 296.49 | 55.03 | 86.9 | Fatty acid ester |

| 5 | 34.16 | 21.75 | 11,14-Octadecadienoic acid, methyl ester | C₁₉H₃₄O₂ | 294.47 | 67.02 | 87.6 | Polyunsaturated fatty acid ester |

| 6 | 35.266 | 30.78 | Isocitronellol | C₁₀H₂₀O | 156.27 | 152.77 | 61.4 | Monoterpenoid alcohol |

| Peak No. | RT (min) |

Area (%) |

Chemical Compounds | MF | MW (g/mol) | Key m/z | Match score | Phytochemical Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20.292 | 0.88 | Citronellol | C₁₀H₂₀O | 156.26 | 69.01 | 74.6 | Monoterpenoid alcohol |

| 2 | 22.135 | 1.29 | Geraniol | C₁₀H₁₈O | 154.25 | 92.90 | 77.6 | Monoterpenoid alcohol |

| 3 | 27.226 | 0.69 | Oleic acid | C₁₈H₃₄O₂ | 282.5 | 137.84 | 65.3 | Unsaturated fatty acid |

| 4 | 29.528 | 9.58 | Isophytol | C₂₀H₄₀O | 296.5 | 57.98 | 70.3 | Diterpene alcohol |

| 5 | 30.127 | 66.26 | Methyl palmitate | C₁₇H₃₄O₂ | 270.45 | 74.02 | 73.8 | Saturated fatty acid ester |

| 6 | 30.800 | 12.67 | 3,5-ditert-butylphenol | C₁₄H₂₂O | 206.32 | 190.59 | 78.7 | Phenolic antioxidant |

| 7 | 31.776 | 4.41 | Thymol | C₁₀H₁₄O | 150.22 | 134.76 | 74.1 | Monoterpenoid phenol |

| 8 | 33.083 | 2.14 | Arachidonic acid | C₂₀H₃₂O₂ | 304.5 | 78.85 | 77.8 | PUFA |

| 9 | 33.798 | 1.03 | Methyl undecanoate | C₁₂H₂₄O₂ | 200.32 | 74.98 | 64.6 | Fatty acid ester |

| 10 | 36.308 | 1.05 | Phytol | C₂₀H₄₀O | 296.5 | 70.92 | 76.1 | Diterpene alcohol |

| Peak No. | RT (min) |

Area (%) |

Chemical Compounds | Molecular Formula | MW (g/mol) | Key m/z | Match score | Phytochemical Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22.256 | 3.22 | Geraniol | C₁₀H₁₈O | 154.25 | 69.03 | 78.6 | Monoterpenoid alcohol |

| 2 | 27.538 | 18.52 | Cubebol | C₁₅H₂₆O | 222.37 | 81.87 | 78.0 | Sesquiterpenoid alcohol |

| 3 | 29.072 | 3.56 | Falcarinol | C₁₇H₂₄O | 244.38 | 114.75 | 80.1 | Long-chain fatty alcohol |

| 4 | 30.153 | 36.84 | Methyl 8-methyl-nonanoate | C₁₁H₂₂O₂ | 186.29 | 74.02 | 74.3 | Branched fatty acid ester |

| 5 | 30.130 | 18.03 | Methyl palmitate | C₁₇H₃₄O₂ | 270.5 | 114.75 | 71.9 | fatty acid methyl ester |

| 6 | 30.242 | 4.31 | methyl octadeca-13,16-diynoate | C₁₉H₃₀O₂ | 290.45 | 190.59 | 78.7 | Polyunsaturated fatty acid ester |

| 7 | 30.772 | 9.28 | 3,5-ditert-butylphenol | C₁₄H₂₂O | 206.32 | 55.04 | 72.9 | Phenolic antioxidant |

| 8 | 34.889 | 6.24 | 2,5-Octadecadiynoic acid, methyl ester | C₁₉H₃₀O₂ | 290.45 | 190.59 | 78.7 | Polyunsaturated fatty acid ester |

| V. sinuatum | A. spinosus | C. getulus | H. subaxillaris | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. cereus | 15.2 ± 1.5b | 8.3 ± 0.6c | 13.5 ± 1.2b | 19.8 ± 0.8a |

| S. aureus | 12.6 ± 0.9a | 7.0 ± 1.1b | 11.8 ± 0.9a | 12.5 ± 0.7a |

| E. coli | 9.3 ± 0.7a | 5.5 ± 0.8b | 6.2 ± 0.5b | 10.1 ± 0.3a |

| P. aeruginosa | 7.0 ± 0.5a | 4.2 ± 0.6b | 5.0 ± 0.4b | 8.4 ± 0.9a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).