1. Introduction

Lantana camara L. is an invasive plant species widely distributed across various regions of the world [

1]. In the Angolan context, it is traditionally known by different vernacular names such as “Cambumbulu”, “Cambumbe”, and “Flor-de-cerca”, particularly in areas where Kikongo, Kimbundu, and Umbundu are spoken. Despite being considered a weed,

L. camara has been traditionally used in folk medicine for a variety of therapeutic purposes, including as an antiseptic, antispasmodic, antihemorrhagic, diuretic, expectorant, febrifuge, and antirheumatic. Its roots have also been employed as an anticonvulsant in different cultural contexts [

2,

3,

4].

In addition to its medicinal uses,

L. camara has attracted scientific interest for its pesticidal, antimicrobial, and larvicidal activities, which have been validated in several studies [

5,

6,

7]. The aromatic leaves and flowers are traditionally used in local remedies to relieve constipation, underscoring the plant’s versatility in traditional healthcare practices. These plant parts are known to be rich in essential oils and natural antioxidants, which are largely responsible for their reported bioactivities.

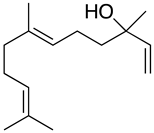

Phytochemical analyses of

L. camara essential oils, particularly those extracted from leaves and flowers, have consistently revealed a high concentration of mono- and sesquiterpenes. The principal compounds identified include β-caryophyllene, zingiberene, α-humulene, curcumene, bisabolene, bicyclogermacrene, isocaryophyllene, valencene, and germacrene D [

8,

9,

10]. These components are associated with a broad range of biological effects, such as repellent, antifungal, antiproliferative, antimicrobial, termiticidal, anti-inflammatory, and antinociceptive activities [

3,

5,

7,

11]. However, previous studies suggest that some of these compounds, due to their lipophilic nature and capacity to interact with cell membranes, may exert toxic effects, including cytotoxicity and irritation, as reported by Passos et al. 2007 [

12]. Comprehensive reviews have further emphasized these risks, compiling toxicological evidence related to lipophilic constituents in essential oils [

13,

14]. Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of incorporating safety assessments into pharmacological studies of this species.

In Angola, L. camara is commonly found near households, along roadsides, and in rural and ruderal vegetation. Its traditional uses include applications in vector control, treatment of skin irritations, and as an antiseptic for wounds. Given the plant’s widespread use and pharmacological potential, this study aims to evaluate the antioxidant activity and compare the chemical composition of essential oils extracted from L. camara leaves and flowers collected in different areas of Uíge Province. Furthermore, the findings are compared with previous literature to assess chemical variability and identify potential pharmacological applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and Origin of Samples

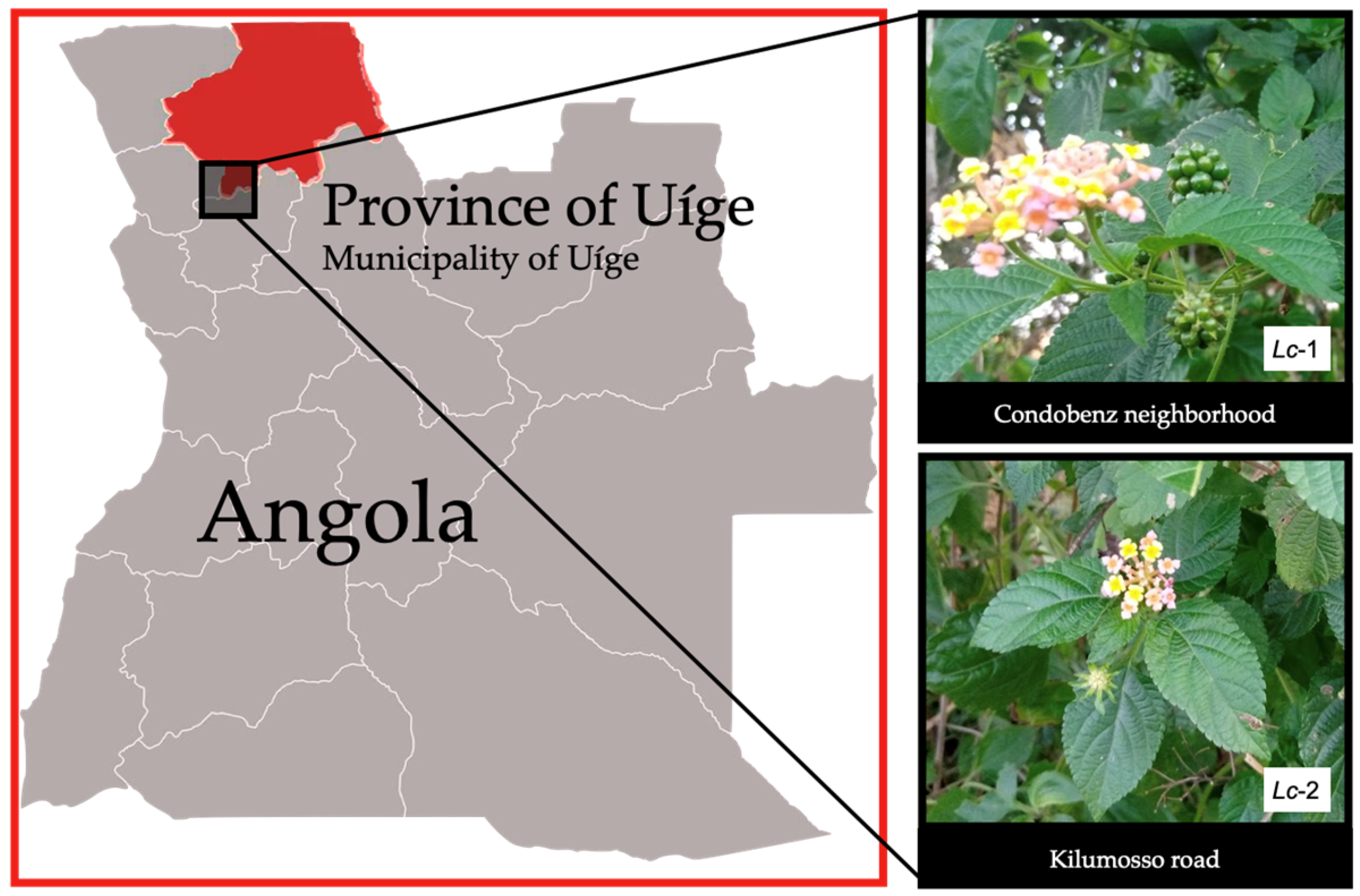

Leaves and flowers of L. camara L. were collected in November 2022 in Uíge Province, northern Angola, from two environmentally distinct urban areas. The first site (Lc-1) corresponds to a ruderal vegetation zone located within the urban perimeter of the Condobenz neighborhood (coordinates: 7°35’59”S, 15°00’13”E). At this site, samples were collected from four individual plants, yielding four leaf samples and two flower samples. The second site (Lc-2) is located in the Kilumosso neighborhood (7°38’32”S, 15°00’25”E), a more anthropized area situated near residential buildings. Here, samples were obtained from three individual plants, comprising three leaf samples and two flower samples. In total, 11 samples were collected—seven leaves and four flowers—from seven individual plants. The plant species was identified as L. camara L. by Professor Mawunu Monizi, a botanist and lecturer in the Department of Agronomy at Kimpavita University, Uíge, Angola.

Figure 1.

Geographic location of sample collection of Lantana camara.

Figure 1.

Geographic location of sample collection of Lantana camara.

2.2. Preparation of Essential Oil

Fresh L. camara leaves and flowers, collected during the flowering period, were subjected to two drying methods: open-air and oven drying. For open-air drying, the plant material was kept in a shaded environment protected from direct sunlight for 5 days to preserve the integrity of active compounds and natural coloration. Oven drying was carried out over 2 days using a homemade device designed to generate sufficient heat for dehydration. The dried material was subsequently stored in plastic bags until extraction.

Essential oils were extracted from dried leaves and flowers using a Cleveng-er apparatus with a solid-liquid ratio of 1:8 (g/mL). The oils were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered to remove residual moisture. In total, 13 extractions were performed: 8 from Lc-1 (6 from leaves, Lc-1leaf, and 2 from flowers, Lc-1flower) and 5 from Lc-2 (3 from leaves, Lc-2leaf, and 2 from flowers, Lc-2flower). However, complete losses occurred during the extraction of the two floral fractions of Lc-2, resulting in only 11 essential oil samples. All samples were stored in amber bottles at 4°C until further analysis. The essential oil yield was calculated based on the weight of the dried plant material and the volume of oil obtained.

2.3. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis

The chemical composition of the essential oils extracted from L. camara leaves and flowers was analyzed using Gas Chromatography coupled to Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), a technique that enables efficient separation and precise identification of volatile and semi-volatile compounds.

GC-MS analyses were performed using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph equipped with a DB-5 capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm, film thickness: 0.25 µm, J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA, USA) and coupled to an Agilent 5975C Inert XL MSD mass spectrometer with a triple-axis quadrupole detector. A 1 µL aliquot of each essential oil sample was injected in splitless mode at an injector temperature of 250 °C. The oven temperature program began at 50 °C (held for 2 min), followed by a temperature ramp of 3–10 °C/min up to 280–300 °C, depending on the sample, to ensure optimal separation of constituents. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min.

Mass spectra were acquired using electron impact (EI) ionization at 70 eV, with the ion source temperature set at 230 °C. Data acquisition and processing were carried out using ChemStation software (Agilent Technologies). Compound identification was performed by comparing the obtained mass spectra with reference spectra from the NIST Mass Spectral Library (NIST/EPA/NIH).

2.4. In Silico Prediction of ADME and Toxicity Properties

The absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of the identified compounds were evaluated using the OSIRIS Property Explorer (

https://www.organic-chemistry.org/prog/) and the SwissADME platform (

http://www.swissadme.ch) [

15] OSIRIS was employed to predict key physicochemical and drug-likeness parameters, including calculated lipophilicity (cLogP), aqueous solubility (cLogS), molecular weight (MW), topological polar surface area (TPSA), drug-likeness, and drug score. Gastrointestinal absorption (GIA) and blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability were predicted using the BOILED-Egg model available on the SwissADME platform [

16].

Assessment of oral bioavailability was conducted according to Lipinski’s Rule of Five (Ro5) [

17], which considers a compound drug-like if it fulfills the following criteria: molecular weight < 500 Da, logP ≤ 5, hydrogen-bond donors (HBD) ≤ 5, hydrogen-bond acceptors (HBA) ≤ 10, and no more than one violation of these rules.

2.5. Antioxidant Activity

2.5.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

The determination of the DPPH radical inhibition percentage will be carried out following the methodology proposed by Jianu et al. [

21]. In each well of a 96-well microplate, 100 µL of DPPH and 100 µL of

Lc-1

leaf essential oil, previously dissolved in DMSO, will be added at concentrations ranging from 15.6 to 500 µg/ml. Quercetin will be used as positive control. The microplate will be incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 minutes, and the absorbance will be measured at a wavelength of 492 nm using an EPOCH™ microplate reader, model M491 (BioTek Instruments, Inc.).

All assays were conducted in triplicate. The DPPH radical scavenging capacity was expressed as the percentage of inhibition, calculated using Formula (1).

where A

control is the absorbance of the reaction media without the test sample and A

test is the absorbance in presence of the essential oil or Quercetin.

2.5.2. ABTS Radical Cation Scavenging Assay

The free radical scavenging capacity of

Lc-1

leaf was conducted as described in Valarezo et al. [

22]. Two stock solutions were prepared: ABTS (7.4 µM) and potassium persulfate (2.6 µM). Equal volumes of both solutions were mixed under constant stirring and incubated in the dark for 12 hours to generate the ABTS working solution. Subsequently, 333 µL of the resulting solution was diluted with 20 mL of methanol to adjust the absorbance to 1.1 ± 0.02 at 734 nm, measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (EPOCH™ microplate reader, model M491 (BioTek Instruments, Inc.).

For the test, 10 µL of the essential oil was mixed with 190 µL of the ABTS working solution in a 96-well plate, and assay various concentrations (15.6 to 500 µg/ml). The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 2 hours, after which the absorbance was recorded at 734 nm. Quercetin served as the positive control. The ABTS• radical scavenging activity (%) was calculated using Formula (1).

2.5.3. NBT Superoxide Radical Scavenging Assay

The superoxide anion radical (O

2•−) scavenging activity was evaluated using a non-enzymatic system, following the method described by Saha et. al. [

23]. The assay was conducted in 96-well microplates. A volume of 50 μL of the

Lc-1

leaf essential oil, prepared to assay various concentrations (15.6 to 500 µg/ml), was mixed with 50 μL of each of the following reagents: phenazine methosulfate (PMS, 120 μM), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH, 936 μM), and nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT, 300 μM). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 25°C for 5 minutes, after which the absorbance was measured at 560 nm using a same microplate reader as previously described.

All experiments were performed in triplicate for each concentration tested. The percentage of superoxide scavenging activity was calculated using the same formula applied for the DPPH radical inhibition assay.

2.5.4. Lipid Peroxidation Inhibition Assay

The effect of

Lc-1

leaf leaf extract on egg yolk lipid peroxidation was assessed using the method described by Ruberto et al. [

24], which quantifies malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of fatty acid peroxidation. Briefly, 100 μL of egg yolk homogenate (1:25 v/v in phosphate-buffered saline, PBS, pH 7.4) was mixed with 10 μL of the extract, 50 μL of FeSO₄ (25 mmol/L), and 300 μL of PBS. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes, after which 50 μL of 15% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to stop the reaction. The samples were centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 15 minutes, and the resulting supernatants were collected. The absorbance of each sample (15.6 to 500 µg/ml) was measured at 532 nm to quantify the MDA levels.

The percentage inhibition of lipid peroxidation was calculated using Formula (2).

where A

control is the absorbance of an egg yolk emulsion in a blank buffer without the test sample and A

test is the absorbance of the egg yolk emulsion containing either the

Lc-1

leaf essential oil or the standard substance (quercetin).

2.6. Anti-Inflammatory Activity by Inhibition of Protein Denaturation

The in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of

Lc-1

leaf essential oil was evaluated using a method adapted from Gîlcescu Florescu et al. [

25], optimized for use in 96-well microplates. In this assay, 5 μL of

Lc-1

leaf essential oil (at concentrations ranging from 15.6 to 500 μg/mL) was mixed with 245 μL of bovine serum albumin (0.4% BSA) prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 6.4). The mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes, followed by heating at 70°C for 5 minutes to induce protein denaturation. After cooling, the absorbance was measured at 660 nm using a same microplate reader as previously described. Diclofenac was used as a positive control. A negative control was prepared under identical conditions, replacing

Lc-1

leaf essential oil with a solution of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in proportions equivalent to those used in the test samples.

The percentage inhibition of albumin denaturation, which reflects the anti-inflammatory potential of the

Lc-1

leaf essential oil, was calculated using Formula (3).

where A

control is the absorbance of negative control and, A

test is the absorbance of the sample containing either

Lc-1

leaves or diclofenac.

2.7. Toxicity Assays

2.7.1. Preliminary Toxicity Assessment Using the Artemia salina Leach Bioassay

The toxicity of

Lc-1

leaf essential oil was evaluated using the

Artemia salina (EG Artemia, SEP-

Art®) bioassay, adapted for 96-well microplates as described by Mesquita el. al. [

26]. In each well, 100 μL of seawater containing 10 to 15

A. salina larvae was combined with 98 μL of artificial seawater Instant Ocean

® (prepared by dissolving 35 g/L in distilled water) and 2 μL of

Lc-1

leaf essential oil, to achieve final concentrations ranging from 15.5 to 300 μg/mL. After 24 hours of exposure, toxicity was assessed by determining the percentage of dead larvae in each well.

The median lethal dose (LD₅₀) was defined as the concentration required to cause 50% mortality of the nauplii. Samples with an LD₅₀ value <1000 μg/mL were classified as toxic, whereas those with an LD₅₀ value ≥1000 μg/mL were considered non-toxic.

2.7.2. MTT-Based Cytotoxicity Screening in RAW 264.7 Macrophages

RAW 264.7 murine macrophages were obtained from the National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS, Pune, India) and cultured in high-glucose DMEM as described by Marques et al. [

27]. Cytotoxicity was evaluated using the MTT assay, which quantifies mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity via the reduction of MTT to formazan. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (1.2 × 10⁵ cells/mL) and incubated for 24 h to allow adherence and proliferation, following protocols by Selvaraj et al. [

28] and Taciak et al. [

29]. Subsequently, cells were treated with

L. camara essential oil (12.5–300 µg/mL in DMSO) for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO₂. After treatment, MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added and incubated for 12 h. Formazan crystals were solubilized in acidified isopropanol, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, USA). Cytotoxicity was expressed relative to untreated controls.

2.8. In silico Prediction of Biological Activity

To predict the potential pharmacological effects and molecular targets associated with the compounds identified in the

Lantana camara essential oil, the PASS (Prediction of Activity Spectra for Substances) online platform was employed (

http://www.way2drug.com/passonline) [

30].

For each compound, predicted activities are expressed as probability values: Pa (probability to be active) and Pi (probability to be inactive). In this study, only those predicted activities with Pa ≥ 0.7 were considered significant and retained for further analysis, as this threshold indicates a high likelihood of biological relevance.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All determinations were made in triplicate and values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical differences were determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and least significant difference (LSD) test, with a p<0.05 for comparison of means in each of the variables analyzed in the different trials. All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad 10.0 software.

3. Results

3.1. Yields and Phytochemical Characterization of Essential Oils

The essential oil yields from leaf samples

Lc-1 and

Lc-2 were comparable, exhibiting minor variations in volume and yield (

Table 1). The essential oil yield from

L. camara flowers (sample

Lc-1

flower) was relatively low, at 0.5% (0.5 ml per 100 g of raw material). Notably, we did not obtain the essential oil from the flowers of sample

Lc-2 due to complete loss during extraction.

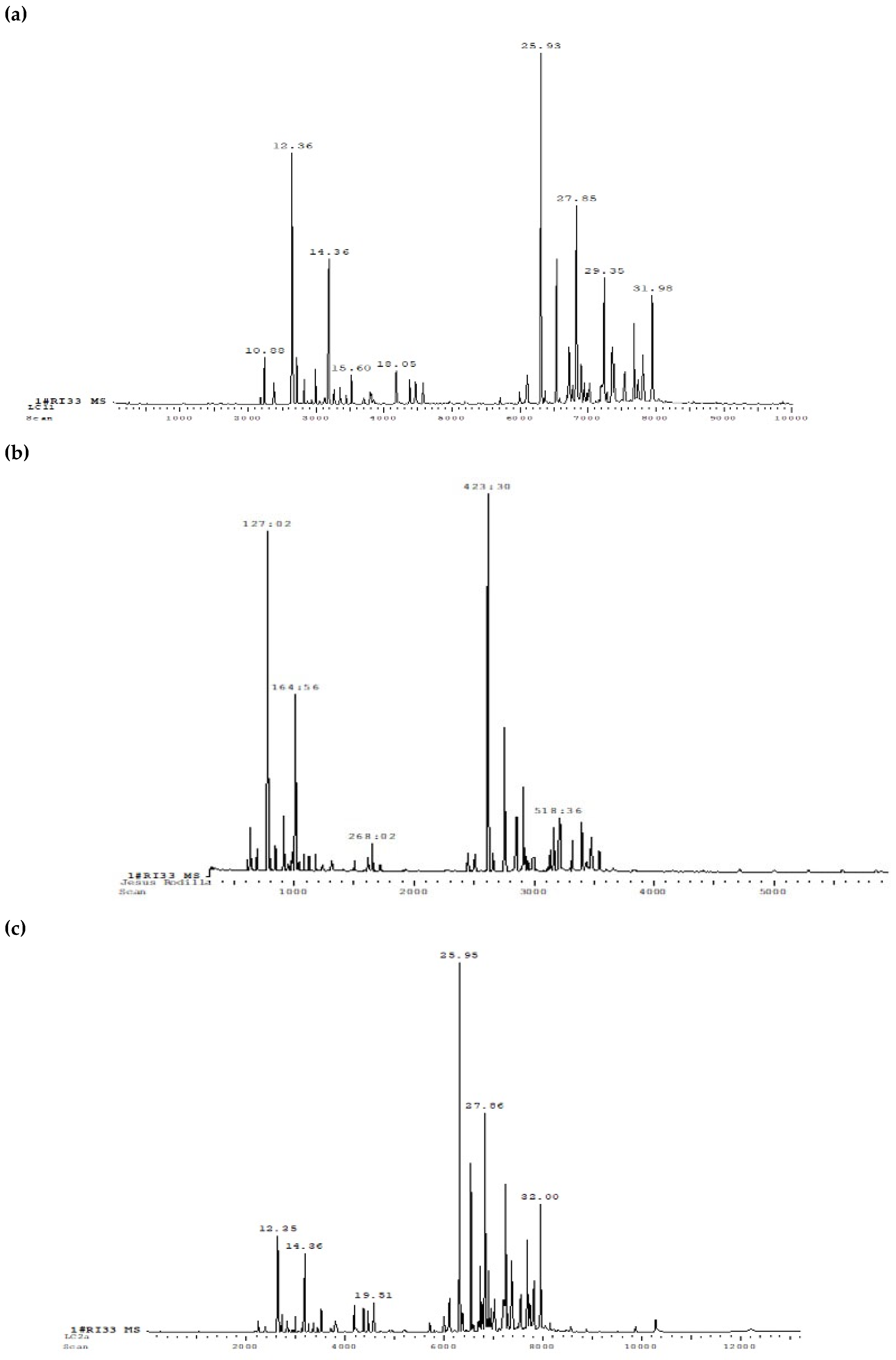

3.2. Phytochemical Characterization of Essential Oils

Chromatographic and mass spectrometric analyses led to the identification of 98 compounds in the

Lc-1

leaf sample, categorized into 17 majors, 65 minor, and 16 trace constituents (

Figure 2a). In contrast, the

Lc-1

flower sample exhibited a less complex chemical profile, with 56 identified compounds, including 5 major components present at concentrations exceeding 5% (

Figure 2b). The

Lc-2

leaf sample demonstrated the greatest chemical diversity, with 106 detected compounds, comprising 18 majors, 64 minor, 24 trace, and 15 unidentified constituents (

Figure 2c). The identification of the compounds was performed based on the Kováts Index (KI), which considers the chromatographic behavior of the substances. This index was used as a tool to characterize and differentiate the compounds present in essential oils, ensuring accurate identification.

Table 2 summarizes the total composition (expressed as percentages), representing the average of three replicates.

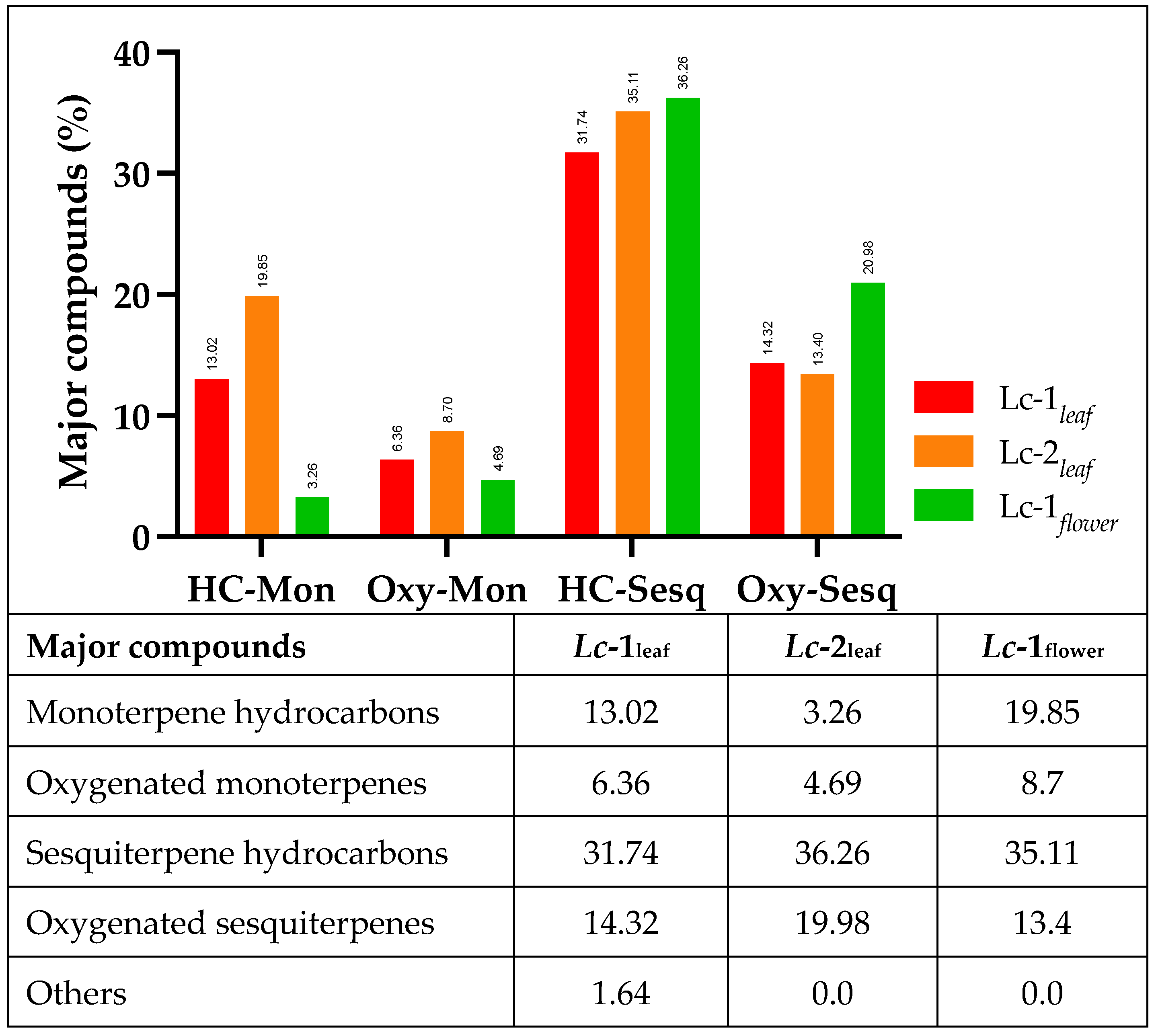

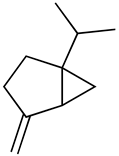

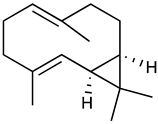

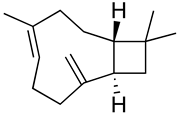

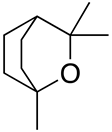

The data obtained in the present study indicate that the leaves and flowers of each sample exhibited distinct chemical fingerprints. The Lc-1leaf essential oil was characterized by the presence of α-pinene, β-pinene, δ-3-carene, (+)-2-bornanone, 1-octen-3-ol, and Davana ether 1. The Lc-2leaf uniquely contained camphor, α-terpineol, cubebol, Davanone, humulene epoxide, and Davana ethers 2 and 3. The Lc-1flower sample was distinguished by the presence of β-phellandrene, limonene, terpinene-4-ol, germacrene B, trans-β-copaene, γ-gurjunene, 14-hydroxycaryophyllene, and isospathulenol.

Across all analyzed samples, β-caryophyllene was the most abundant compound, with relative concentrations of 14.49% in Lc-1 leaves, 16.66% in

Lc-2

leaf, and 18.29% in

Lc-1

flower. In

Lc-1

leaf, sabinene (9.13%) and bicyclogermacrene (8.18%) were the next most prevalent constituents.

Lc-2

leaf was characterized by high levels of bicyclogermacrene (9.34%) and α-humulene (6.36%). In the

Lc-1

flower sample, β-phellandrene (12.77%) and germacrene B (5.54%) were the dominant components. The data obtained confirm that

L. camara is a significant source of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes, with β-caryophyllene and α-humulene consistently identified as the principal and most abundant constituents (

Figure 3).

3.3. Prediction of ADME and Toxicity Properties

The computational ADMET analysis revealed that all six major compounds exhibited favorable drug-like properties with only one Lipinski rule violation (

Table 3). The compounds displayed a range of lipophilicity (cLogP 2.11-6.24), with α-humulene being the most lipophilic (6.24) and 1,8-cineole the least (2.11), while all showed low water solubility (cLogS -2.48 to -3.66). 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) and nerolidol demonstrated high gastrointestinal absorption (GIA), and three compounds (sabinene, 1,8-cineole, and nerolidol) were predicted to cross blood–brain barrier (BBB). All compounds were predicted not to be substrates of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), suggesting a lower likelihood of active efflux, which may enhance their intracellular bioavailability.

On the other hand, major compounds of Lc-1leaf showed no structural alerts for pan-assay interference (PAINS) and had favorable synthetic accessibility scores (2.87-4.51). While sabinene emerged with the highest drug score (0.45), suggesting particularly promising drug development potential.

Toxicological prediction identified six compounds with potential irritant effects, with skin sensitization, carcinogenicity, and hepatotoxicity being the most frequently predicted toxicological endpoints. Notably, 1,8-cineole and bicyclogermacrene were associated with potential reproductive toxicity and mutagenicity.

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

In the present study, the antioxidant activity of

Lc-1

leaf essential oil was determined by using a DPPH, ABTS and O

2•− radical scavenging method and was compared to quercetin activity. The antioxidant activity of essential oil samples is summarized in

Table 4 in terms of efficacy inhibitory maximal (Emax) and IC

50 values.

Our study demonstrated that the essential oil from Lc-1leaf exhibited moderate DPPH free radical-scavenging activity, with a maximum inhibition (Emax) of 68.2 ± 2.7%. The inhibitory effect of the essential oil was not significantly lower than that of the reference compound, quercetin (78.5 ± 1.7%). To further confirm the antioxidant potential of the essential oil, additional assays targeting ABTS, and superoxide anion (O2•−) radicals were performed. In the ABTS assay, the essential oil again displayed moderate activity, achieving 77.1 ± 1.8% inhibition compared to 93.3 ± 0.3% observed for quercetin.

In contrast, the essential oil exhibited negligible scavenging activity against O2•−, with a low maximum effect of 5.7 ± 13.1% and a high IC₅₀ value of 1491 µg/mL. These results sharply contrast with those of quercetin, which demonstrated a high inhibitory activity (80.1 ± 0.7%) and a low IC₅₀ of 13.92 µg/mL.

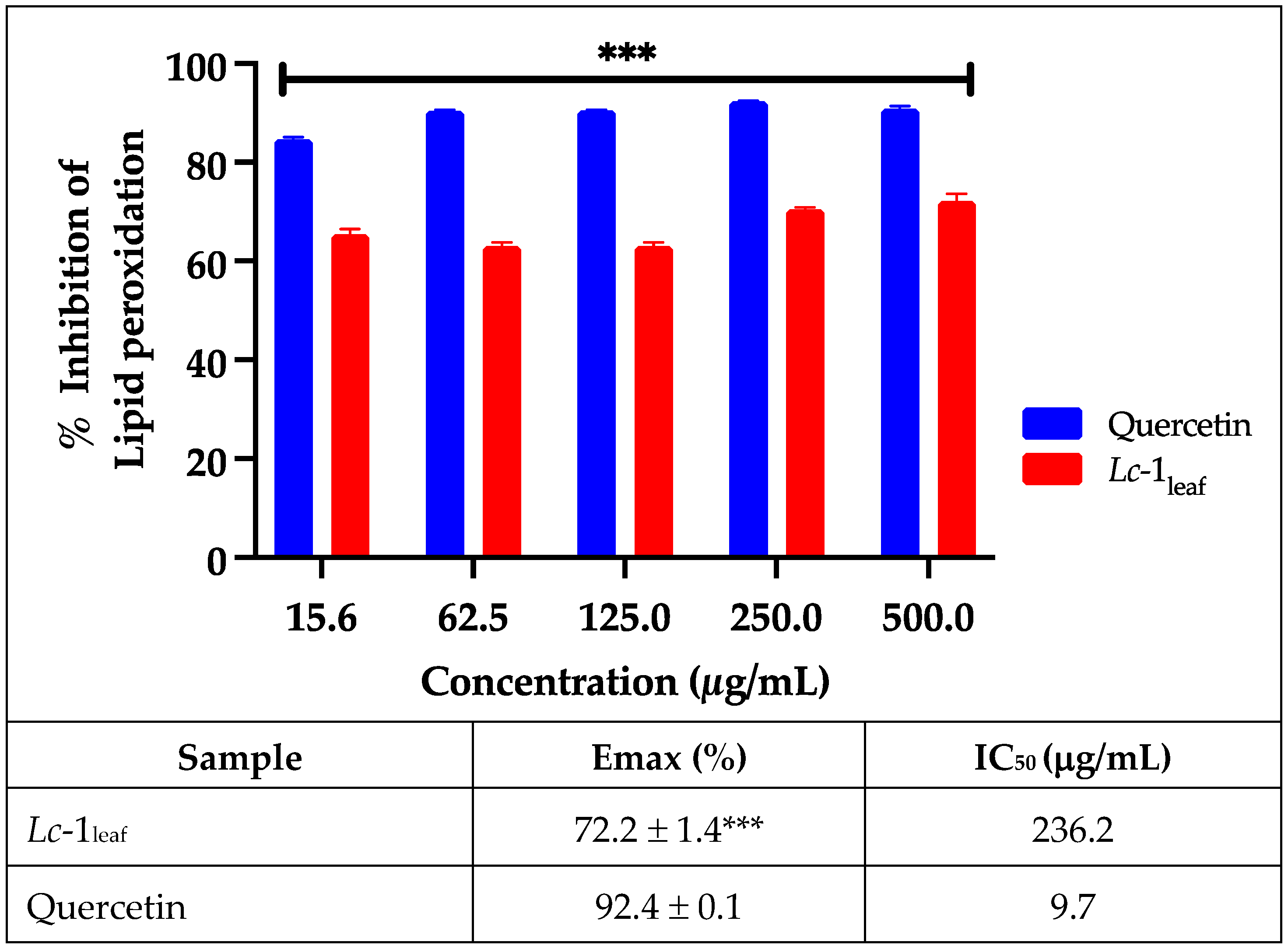

The results from the lipid peroxidation assays further support the antioxidant potential of

L. camara essential oil, as previously demonstrated in the DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging assays. As shown in

Figure 4, the

Lc-1

leaf sample achieved a maximum inhibition of 72.2 ± 1.4%, which was slightly lower than the inhibition exhibited by the reference standard, quercetin (92.4 ± 0.1%).

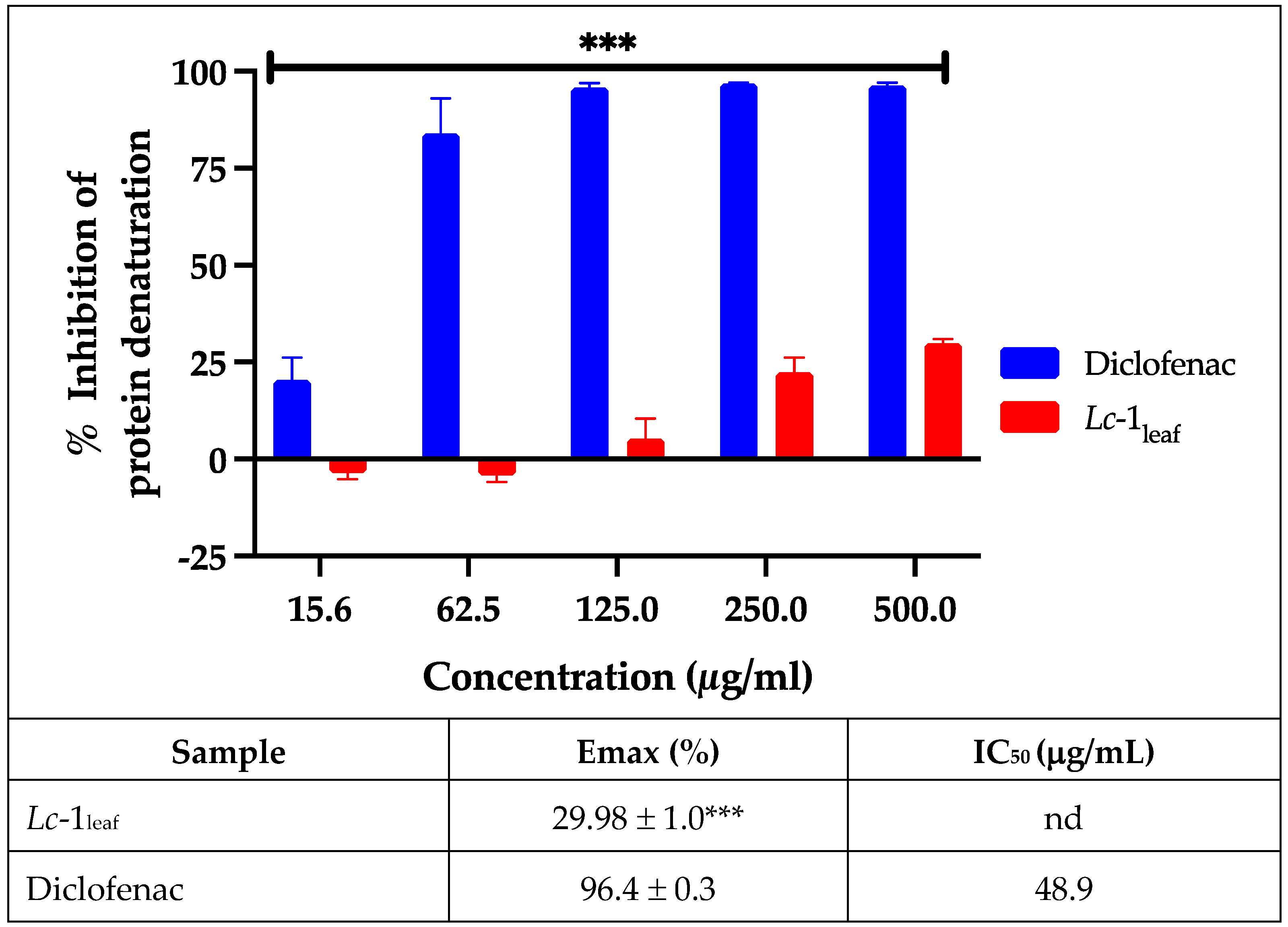

3.5. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of L. camara Essential Oil

The anti-inflammatory activity of

Lc-1

leaf was evaluated based on its ability to inhibit protein denaturation (in vitro model). As shown in

Figure 5,

Lc-1

leaf exhibited a moderate inhibitory effect compared to the reference drug diclofenac sodium (p < 0.05). While diclofenac achieved nearly complete inhibition (~100%) of protein denaturation,

Lc-1

leaf showed a dose-dependent effect, reaching a maximum inhibition of approximately 28% at the highest tested concentration. The IC₅₀ value for

Lc-1

leaf could not be determined, as the maximum inhibition did not reach 50%, preventing reliable curve fitting. This was reported as “not determined” (nd), indicating limited anti-inflammatory activity within the tested concentration range. These findings suggest that, although the constituents of

L. camara have been associated with anti-inflammatory activity [

31,

32,

33],

Lc-1

leaf possesses moderate anti-inflammatory properties.

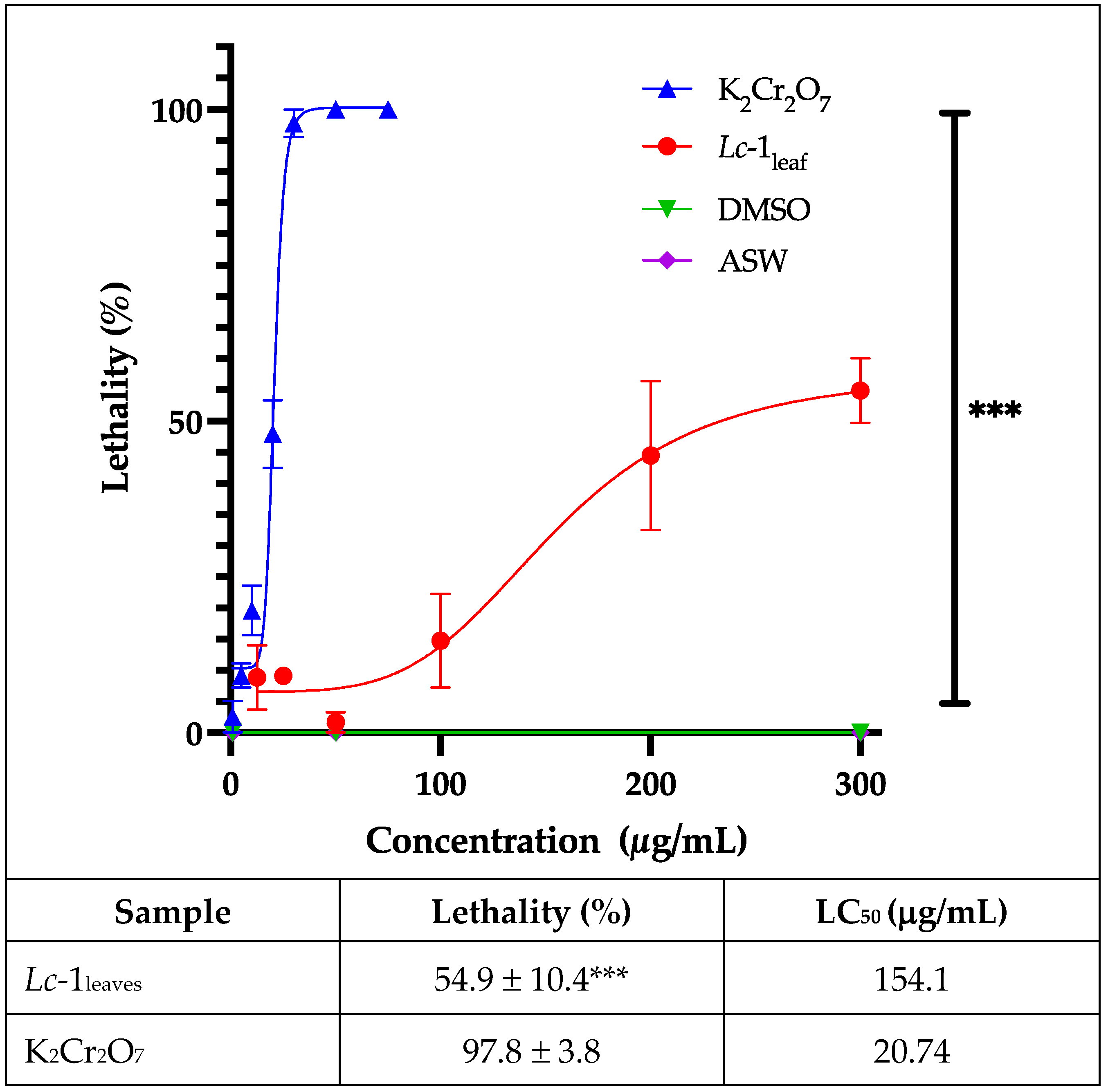

3.5. Toxicity Assays

3.5.1. Preliminary Toxicity Assessment Using the Artemia salina Leach Bioassay

No mortality was observed in the control group, confirming that DMSO is a suitable solvent for this assay (

Figure 6). The tested essential oil exhibited a concentration-dependent mortality, ranging from 10% to 60% across the tested concentrations. The

Lc-1

leaf sample induced a maximum mortality rate of 54.9 ± 10.4%, whereas the positive control (potassium dichromate) caused 97.8 ± 3.8% mortality. The calculated LC₅₀ values were 154.1 µg/mL for the essential oil and 20.74 µg/mL for the standard (

Figure 6). According to Rajabi et al. [

34], an LC₅₀ between 100 and 500 µg/mL indicates moderate cytotoxicity, suggesting a relationship with the antiparasitic action described for

L. camara essential oils [

7].

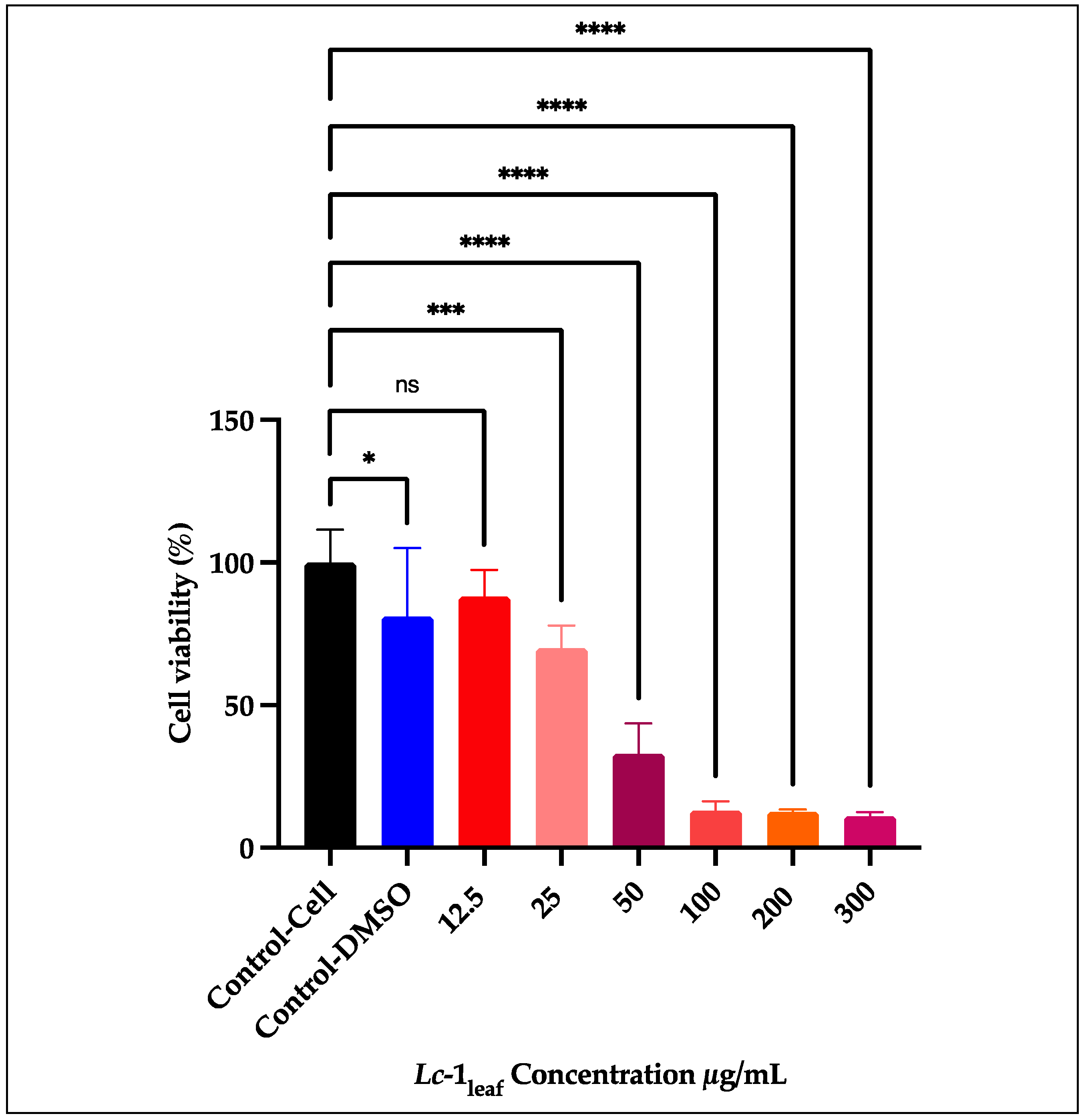

3.5.2. Cytotoxicity Screening in RAW 264.7

The relative metabolic activity of RAW 264.7 macrophages decreased in a concentration-dependent manner following exposure to increasing concentrations of

Lc-1

leaf at 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 300 μg/mL (

Figure 7). After 24 h of treatment, the IC₅₀ value was determined to be 31.58 μg/mL, indicating a significant cytotoxic effect of

L. camara leaf essential oil. At the highest concentration tested (300 μg/mL), cell viability was reduced by up to 88% compared to untreated control cells.

2.5.3. Prediction of Biological Activity

Using the PASS online tool, we screened the six primary

Lc-1

leaves compounds for potential biological activities,

Table 5 details the predicted activities for each compound. Our data indicate some interesting pharmacological activities, considering probably activity ≥ 0.7 as highly probable for experimental validation. The most highlighted evidence is target for anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and dermatologic applications. Some multiple effects compounds as sabinene and β-caryophyllene show broad activity (bone, skin, and cancer), and 1,8-cineole and nerolidol may benefit liver, mental health, and some metabolic disorders.

4. Discussion

This study presents a comprehensive phytochemical, pharmacological, and toxicological evaluation of essential oils extracted from

Lantana camara leaves and flowers collected in Uíge, Angola. Several compounds were common to both leaf samples (

Lc-1

leaf and

Lc-2

leaf), including sabinene, β-pinene, 1,8-cineole, β-elemene, β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, germacrene-D, bicyclogermacrene, nerolidol, spathulenol, caryophyllene oxide, and τ-cadinol. Notably, sabinene, 1,8-cineole, β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, nerolidol, spathulenol, and caryophyllene oxide were shared across all three samples, suggesting their potential importance as key secondary metabolites in

L. camara. The data from our study, consistent with previous reports, identify

L. camara as a significant source of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes, with β-caryophyllene and α-humulene as the principal and most abundant compounds [

6,

7,

35].

In addition to these similarities, it has also been reported that the chemical components and their relative composition may vary depending on geographical origin, as well as on climatic and soil conditions where the plants were cultivated [

36]. This underscores the relevance of conducting a phytochemical investigation of the essential oils from leaves and flowers collected in the province of Uíge, Angola. Overall, the results are consistent with previous reports describing the major constituents present in the essential oils of

L. camara leaves and flowers. For the leaf essential oil, various authors have consistently reported the presence of β-caryophyllene and α-humulene as principal compounds. Similarly, in samples collected from the Bregbo region, β-caryophyllene and α-humulene were also identified as major constituents in the flower essential oil [

35].

The floral oil (

Lc-1

flower) displayed a distinct profile dominated by monoterpenes, particularly β-phellandrene, limonene, eucalyptol, and humulene compounds that impart characteristic aroma and open avenues for applications in perfumery, aromatherapy, and cosmetics [

24,

35,

36,

37]. Additionally, these compounds also exhibit antimicrobial and antioxidant properties [

21], in contrast to the leaf oils, which are richer in sesquiterpenes and possess greater therapeutic potential. This functional differentiation underscores the importance of defining specific uses for each oil type.

The PASS online platform predicted various pharmacological activities for the major compounds identified in the

Lc-1

leaf sample. The most prominent predicted effects included antineoplastic, anti-inflammatory, and dermatological applications. Additional potential benefits included lipid metabolism regulation, antiulcer activity, and hepatoprotective effects. These computational predictions are consistent with findings from biological studies. For instance, anti-inflammatory activity has been previously described for α-humulene [

32,

38], sabinene [

31], β-caryophyllene [

39], 1,8-cineole [

33], and nerolidol [

40].

These compounds have also been reported to exhibit antioxidant properties [

41,

42,

43], which are relevant to their proposed antitumor and anti-inflammatory activities. The findings regarding the individual pharmacological potential of

L. camara constituents are further supported by this study, in which the

Lc-1

leaf sample demonstrated significant antioxidant activity.

The primary applications of

L. camara have been associated with its larvicidal and repellent activities, as previously reported [

6,

7,

11,

35]. In host–parasite interactions, the immune response often involves the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by macrophages as a defense mechanism [

44]. Certain antiparasitic agents may enhance this oxidative burst to promote parasite clearance. Conversely, some parasites have developed adaptive strategies to neutralize host-derived oxidative stress.

In this context, the current findings suggest noteworthy biological properties for the Lc-1leaf essential oil. While this oil appears to confer antioxidant protection against lipid peroxidation during parasitemia, it does not inhibit superoxide anion production. This selective antioxidant profile may support the host’s antiparasitic mechanisms that rely on ROS generation.

The antioxidant capacity exhibited by

Lc-1

leaf is likely attributable to its principal constituents. Similar synergistic antiradical effects have been documented in essential oils from other geographical origins [

7,

35]. Furthermore, individual contributions from major compounds such as β-caryophyllene are well-supported in the literature, as this sesquiterpene has demonstrated the ability to inhibit lipid peroxidation in both in vitro and in vivo models [

45,

46,

47].

Finally, the Artemia salina bioassay indicated moderate cytotoxicity for the Lc-1leaf oil, with an LC₅₀ value supporting its potential for antiparasitic applications but warranting further toxicity profiling. Together, these findings reinforce the pharmacological potential of L. camara essential oil and support its continued investigation as a source of bioactive compounds with possible therapeutic relevance.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the chemical variability of Lantana camara essential oils directly shapes their potential applications: leaf oils, enriched in bioactive sesquiterpenes, exhibit greater therapeutic promise, whereas floral oils, dominated by monoterpenes, present a profile more suitable for perfumery and cosmetic uses. This functional differentiation, together with pharmacological and toxicological evidence, highlights the need for integrated approaches that combine chemical characterization, biological evaluation, and safety assessment, thereby reinforcing the status of L. camara as a valuable source of bioactive compounds for both medicinal and industrial applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K, J.M.R, L.S and E.G.D.L; chemical analysis methodology , N.K, J.M.R, M.M., N.S., L.S and N.S; software, H.A.S.; validation, J.M.R, N.S., L.S and E.G.D.L; investigation, N.K, J.A.M.P and M.M; evaluation of the antioxidant activity, toxicity, and anti-inflammatory, A.M., H.A.S., M.D. and J.A.M.P; resources, J.M.R, J.A.M.P, and E.G.D.L; data curation: N.K and E.G.D.L, writing—original draft preparation, L.S., N.K and E.G.D.L; writing—review and editing, N.K, L.S, J.M.R and E.G.D.L, supervision, J.A.M.P, J.M.R, L.S and E.G.D.L; project administration, E.G.D.L and J.M.R ; funding acquisition, J.M.R , L.S and E.G.D.L All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Secretaría Nacional de Ciencia Tecnología e Innovación, grant numbers FID2024-072 and SNI-EGDL. The authors are grateful for the Research Unit of Fiber Materials and Environmental Technolo-gies (FibEnTech-UBI) through the Project reference UIDB/00195/2020, funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, IP/MCTES through national funds (PIDDAC) and DOI: 10.54499/UIDB/00195/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00195/202014.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

To the Research and Postgraduate Department of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Panama, for the administrative support provided in the management of funds and development of research. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used the NAPROC-13 database to confirm the structures and biological relevance of the main constituents of Lc-1leaf. The NMR spectrometers are part of the National NMR Facility supported by FCT-Portugal (ROTEIRO/0031/2013-PINFRA/22161/2016, financed by FEDER through COMPETE 2020, POCI and PORL and FCT through PIDDAC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bhagwat, S.A.; Breman, E.; Thekaekara, T.; Thornton, T.F.; Willis, K.J. A Battle Lost? Report on Two Centuries of Invasion and Management of Lantana Camara L. in Australia, India and South Africa. PLoS One 2012, 7, e32407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda, R.; Cáceres, A.; Cruz, S.M.; Aceituno, J.A.; Marroquín, E.S.; Barrios Sosa, A.C.; Strangman, W.K.; Williamson, R.T. Nephroprotective Plant Species Used in Traditional Mayan Medicine for Renal-Associated Diseases. J Ethnopharmacol 2023, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyoum, A.; Pålsson, K.; Kung’a, S.; Kabiru, E.W.; Lwande, W.; Killeen, G.F.; Hassanali, A.; Knols, B.G.J. Traditional Use of Mosquito-Repellent Plants in Western Kenya and Their Evaluation in Semi-Field Experimental Huts against Anopheles Gambiae: Ethnobotanical Studies and Application by Thermal Expulsion and Direct Burning. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2002, 96, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavela, R.; Benelli, G. Ethnobotanical Knowledge on Botanical Repellents Employed in the African Region against Mosquito Vectors - A Review. Exp Parasitol 2016, 167, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, F.G.; Bouzada, M.L.M.; Fabri, R.L.; de, O. Matos, M.; Moreira, F.O.; Scio, E.; Coimbra, E.S. Antileishmanial and Antifungal Activity of Plants Used in Traditional Medicine in Brazil. J Ethnopharmacol 2007, 111, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisha, K.; Visakh, N.U.; Pathrose, B.; Mori, N.; Baeshen, R.S.; Shawer, R. Extraction, Chemical Composition and Insecticidal Activities of Lantana Camara Linn. Leaf Essential Oils against Tribolium Castaneum, Lasioderma Serricorne and Callosobruchus Chinensis. Molecules 2024, 29, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.M.; Duarte, A.E.; Morais-Braga, M.F.B.; Waczuk, E.P.; Vega, C.; Leite, N.F.; De Menezes, I.R.A.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Kamdem, J.P. Chemical Characterization and Trypanocidal, Leishmanicidal and Cytotoxicity Potential of Lantana Camara L. (Verbenaceae) Essential Oil. Molecules 2016, 21, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurade, N.P.; Jaitak, V.; Kaul, V.K.; Sharma, O.P. Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils of Lantana Camara, Ageratum Houstonianum and Eupatorium Adenophorum. Pharm Biol 2010, 48, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, J.L.; Almeida Barbosa, L.C.; Demuner, A.J.; Alvarenga, E.S.; Da Silva, C.M.; Barreto, R.W. Chemical Characterization of Volatile Compounds of Lantana Camara L. and L. Radula Sw. and Their Antifungal Activity. Molecules 2012, 17, 11447–11455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, T.R.S.A.; Leite, J.A.C.; de Mesquita, L.S.S.; Bezerra, S.A.; Gomes Ribeiro, E.C.; Silveira, D.P.B.; Mesquita, J.W.C. de; do Amaral, F.M.M.; Coutinho, D.F. Seasonal Variation in the Chemical Composition and Larvicidal Activity against Aedes Aegypti L. of Essential Oils from Brazilian Amazon. Exp Parasitol 2022, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udappusamy, V.; Mohan, H.; Thinagaran, R. Lantana Camara L. Essential Oil Mediated Nano-Emulsion Formulation for Biocontrol Application: Anti-Mosquitocidal, Anti-Microbial and Antioxidant Assay. Arch Microbiol 2022, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos, G.F.; Fernandes, E.S.; da Cunha, F.M.; Ferreira, J.; Pianowski, L.F.; Campos, M.M.; Calixto, J.B. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Allergic Properties of the Essential Oil and Active Compounds from Cordia Verbenacea. J Ethnopharmacol 2007, 110, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husnu Can Baser, K.; Buchbauer, G. Handbook of Essential Oils: Science, Technology, and Applications.

- De Cássia Da Silveira E Sá, R.; Andrade, L.N.; De Sousa, D.P. A Review on Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Monoterpenes. Molecules 2013, 18, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Zoete, V. A BOILED-Egg To Predict Gastrointestinal Absorption and Brain Penetration of Small Molecules. ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and Computational Approaches to Estimate Solubility and Permeability in Drug Discovery and Development Settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2001, 46, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Shi, S.; Yi, J.; Wang, N.; He, Y.; Wu, Z.; Peng, J.; Deng, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, C.; et al. ADMETlab 3.0: An Updated Comprehensive Online ADMET Prediction Platform Enhanced with Broader Coverage, Improved Performance, API Functionality and Decision Support. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, W422–W431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, Y.; De Sá, A.G.C.; Ascher, D.B. Deep-PK: Deep Learning for Small Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, W469–W475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.E.V.; Blundell, T.L.; Ascher, D.B. PkCSM: Predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and Toxicity Properties Using Graph-Based Signatures. J Med Chem 2015, 58, 4066–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jianu, C.; Rusu, L.C.; Muntean, I.; Cocan, I.; Lukinich-Gruia, A.T.; Goleț, I.; Horhat, D.; Mioc, M.; Mioc, A.; Șoica, C.; et al. In Vitro and In Silico Evaluation of the Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Potential of Thymus Pulegioides Essential Oil. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valarezo, E.; Flores-Maza, P.; Cartuche, L.; Ojeda-Riascos, S.; Ramírez, J. Phytochemical Profile, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of Essential Oil Extracted from Ecuadorian Species Piper Ecuadorense Sodiro. Nat Prod Res 2021, 35, 6014–6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Basak, B.B.; Manivel, P.; Kumar, J. Valorization of Java Citronella (Cymbopogon Winterianus Jowitt) Distillation Waste as a Potential Source of Phenolics/Antioxidant: Influence of Extraction Solvents. J Food Sci Technol 2020, 58, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberto, G.; Baratta, M.T.; Deans, S.G.; Dorman, H.J.D. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Foeniculum Vulgare and Crithmum Maritimum Essential Oils. Planta Med 2000, 66, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gîlcescu Florescu, C.A.; Stanciulescu, E.C.; Berbecaru-Iovan, A.; Balasoiu, R.M.; Pisoschi, C.G. In Vitro Assessment of Free Radical Scavenging Effect and Thermal Protein Denaturation Inhibition of Bee Venom for an Anti-Inflammatory Use. Curr Health Sci J 2024, 50, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, K.D.S.M.; Feitosa, B. de S.; Cruz, J.N.; Ferreira, O.O.; Franco, C. de J.P.; Cascaes, M.M.; Oliveira, M.S. de; Andrade, E.H. de A. Chemical Composition and Preliminary Toxicity Evaluation of the Essential Oil from Peperomia Circinnata Link Var. Circinnata. (Piperaceae) in Artemia Salina Leach. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taciak, B.; Białasek, M.; Braniewska, A.; Sas, Z.; Sawicka, P.; Kiraga, Ł.; Rygiel, T.; Król, M. Evaluation of Phenotypic and Functional Stability of RAW 264.7 Cell Line through Serial Passages. PLoS One 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, V.; Nepal, N.; Rogers, S.; Manne, N.D.P.K.; Arvapalli, R.; Rice, K.M.; Asano, S.; Fankenhanel, E.; Ma, J.Y.; Shokuhfar, T.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide Induced MAP Kinase Activation in RAW 264.7 Cells Attenuated by Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. Data Brief 2015, 4, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, J.I.; Alves, J.S.F.; Torres-Rêgo, M.; Furtado, A.A.; Siqueira, E.M. da S.; Galinari, E.; Araújo, D.F. de S.; Guerra, G.C.B.; de Azevedo, E.P.; Fernandes-Pedrosa, M. de F.; et al. Phytochemical Analysis by HPLC-HRESI-MS and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Tabernaemontana Catharinensis. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonov, D.A.; Lagunin, A.A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Rudik, A. V.; Druzhilovskii, D.S.; Pogodin, P. V.; Poroikov, V. V. Prediction of the Biological Activity Spectra of Organic Compounds Using the Pass Online Web Resource. Chem Heterocycl Compd (N Y) 2014, 50, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, J.; Zuzarte, M.; Gonçalves, M.J.; Lopes, M.C.; Cavaleiro, C.; Salgueiro, L.; Cruz, M.T. Antifungal, Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Oenanthe Crocata L. Essential Oil. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2013, 62, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, E.S.; Passos, G.F.; Medeiros, R.; da Cunha, F.M.; Ferreira, J.; Campos, M.M.; Pianowski, L.F.; Calixto, J.B. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Compounds Alpha-Humulene and (−)-Trans-Caryophyllene Isolated from the Essential Oil of Cordia Verbenacea. Eur J Pharmacol 2007, 569, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.J.; Fischer, N.; Efferth, T. Phytochemicals as Inhibitors of NF-ΚB for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmacol Res 2018, 129, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, S.; Ramazani, A.; Hamidi, M.; Naji, T. Artemia Salina as a Model Organism in Toxicity Assessment of Nanoparticles. DARU Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2015, 23, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nea, F.; Kambiré, D.A.; Genva, M.; Tanoh, E.A.; Wognin, E.L.; Martin, H.; Brostaux, Y.; Tomi, F.; Lognay, G.C.; Tonzibo, Z.F.; et al. Composition, Seasonal Variation, and Biological Activities of Lantana Camara Essential Oils from Côte d’Ivoire. Molecules 2020, 25, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satyal, P.; Crouch, R.A.; Monzote, L.; Cos, P.; Awadh Ali, N.A.; Alhaj, M.A.; Setzer, W.N. The Chemical Diversity of Lantana Camara: Analyses of Essential Oil Samples from Cuba, Nepal, and Yemen. Chem Biodivers 2016, 13, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haikal, A.; Ali, A.R. Chemical Composition and Toxicity Studies on Lantana Camara L. Flower Essential Oil and Its in Silico Binding and Pharmacokinetics to Superoxide Dismutase 1 for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Therapy. RSC Adv 2024, 14, 24250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogerio, A.P.; Andrade, E.L.; Leite, D.F.P.; Figueiredo, C.P.; Calixto, J.B. Preventive and Therapeutic Anti-Inflammatory Properties of the Sesquiterpene α-Humulene in Experimental Airways Allergic Inflammation. Br J Pharmacol 2009, 158, 1074–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandiffio, R.; Geddo, F.; Cottone, E.; Querio, G.; Antoniotti, S.; Pia Gallo, M.; Maffei, M.E.; Bovolin, P. Protective Effects of (E)-β-Caryophyllene (BCP) in Chronic Inflammation. Nutrients 2020, Vol. 12, Page 3273 2020, 12, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonsêca, D. V.; Salgado, P.R.R.; de Carvalho, F.L.; Salvadori, M.G.S.S.; Penha, A.R.S.; Leite, F.C.; Borges, C.J.S.; Piuvezam, M.R.; Pordeus, L.C. de M.; Sousa, D.P.; et al. Nerolidol Exhibits Antinociceptive and Anti-Inflammatory Activity: Involvement of the GABAergic System and Proinflammatory Cytokines. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2016, 30, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.; Lee, D.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, K.J.; Jin, H.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, H.M.; Kim, B.; Won, K.J. Sabinene Prevents Skeletal Muscle Atrophy by Inhibiting the MAPK–MuRF-1 Pathway in Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, Vol. 20, Page 4955 2019, 20, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinholes, J.; Gonçalves, P.; Martel, F.; Coimbra, M.A.; Rocha, S.M. Assessment of the Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Effects of Sesquiterpenic Compounds in in Vitro Caco-2 Cell Models. Food Chem 2014, 156, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinholes, J.; Rudnitskaya, A.; Gonçalves, P.; Martel, F.; Coimbra, M.A.; Rocha, S.M. Hepatoprotection of Sesquiterpenoids: A Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship (QSAR) Approach. Food Chem 2014, 146, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stafford, J.L.; Neumann, N.F.; Belosevic, M. Macrophage-Mediated Innate Host Defense against Protozoan Parasites. Crit Rev Microbiol 2002, 28, 187–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.T.; Zhong, L.S.; Huang, C.; Guo, Y.Y.; Jin, F.J.; Hu, Y.Z.; Zhao, Z.B.; Ren, Z.; Wang, Y.F. β-Caryophyllene Acts as a Ferroptosis Inhibitor to Ameliorate Experimental Colitis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wu, W.; Song, Y.; Zhang, J.; Han, D.; Shu, C.; Lian, F.; Fang, X. β-Caryophyllene Confers Cardioprotection by Scavenging Radicals and Blocking Ferroptosis. J Agric Food Chem 2024, 72, 18003–18012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yovas, A.; Stanely, S.P.; Issac, R.; Ponnian, S.M.P. β-Caryophyllene Blocks Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Hyperlipidemia in Isoproterenol-Induced Myocardial Infarcted Rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2023, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).