Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

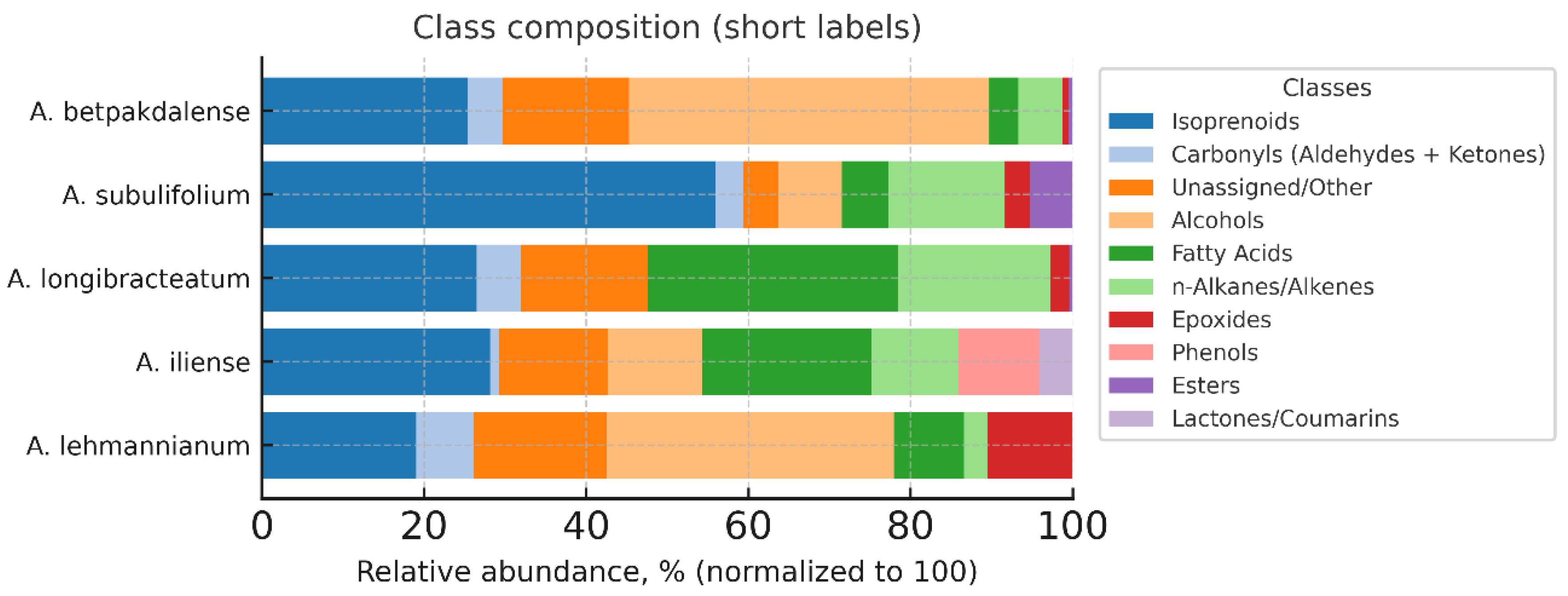

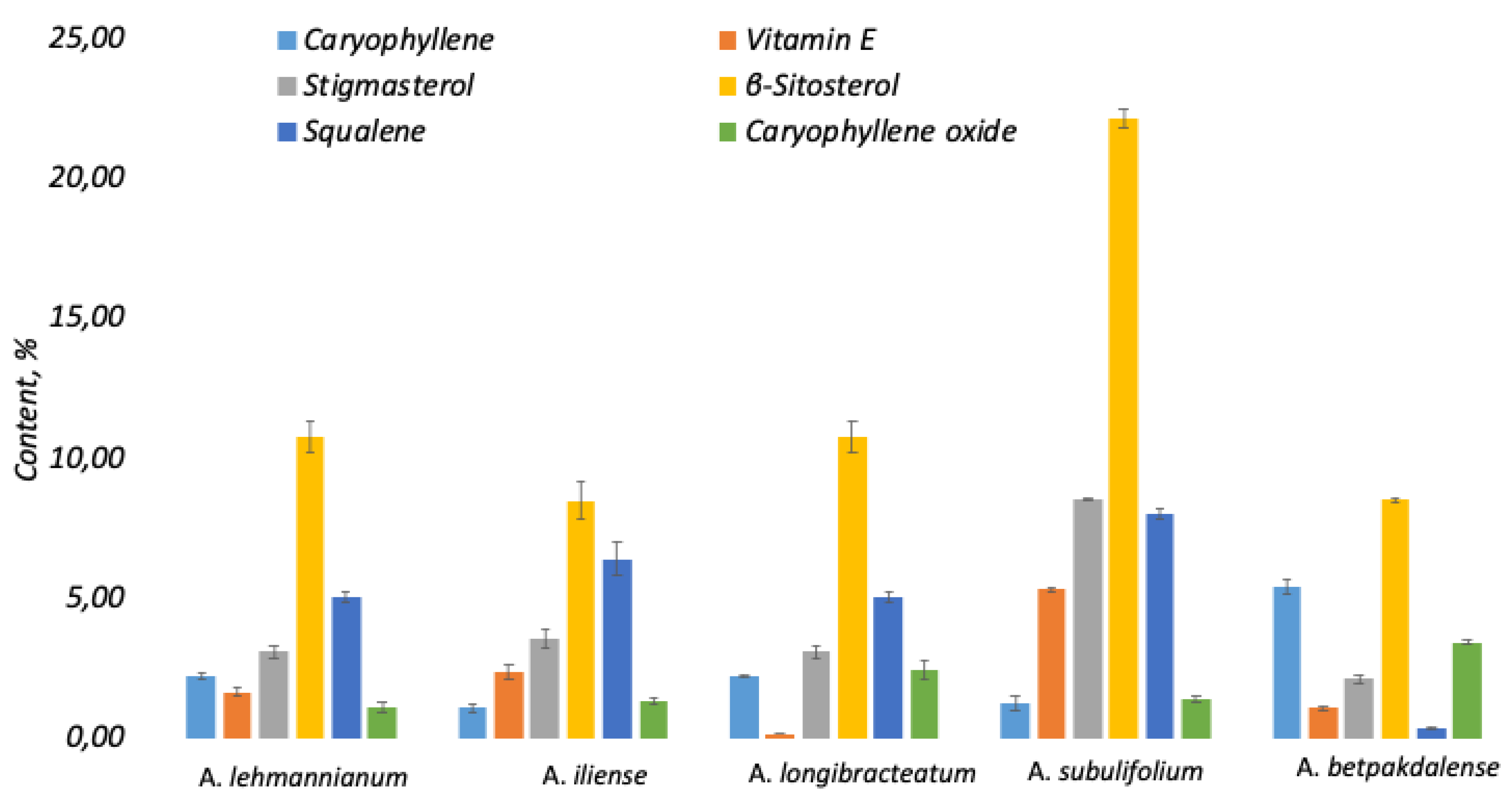

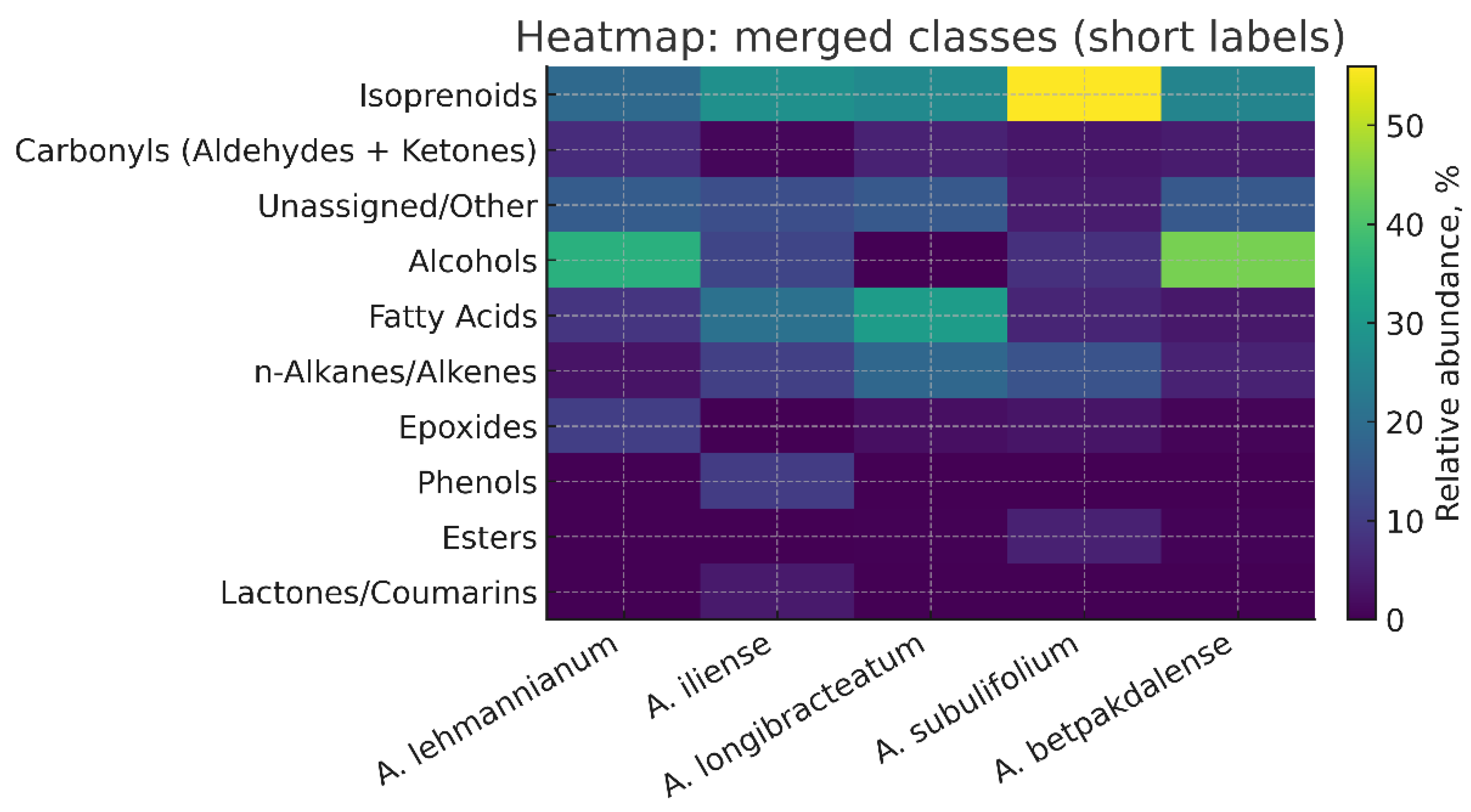

This article presents the results of the first comparative phytochemical analysis of five species of the genus Arthrophytum Schrenk (Amaranthaceae Juss.) — A. lehmannianum Bunge, A. iliense Iljin, A. longibracteatum Korovin, A. subulifolium Schrenk, and A. betpakdalense Korovin & Mironov — using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). The genus Arthrophytum is a relict systematic group whose range is limited to the desert regions of Northern Turan. The largest number of representatives of the genus are concentrated in the geologically ancient Betpakdala Desert. All of them are narrowly endemic and stenotopic species growing in inaccessible habitats, which determines their rarity and, as a result, their understudied nature, including the virtual absence of data on their phytochemical composition. Meanwhile, the results of our research, which aimed to conduct a comparative phytochemical analysis of the five above-mentioned species of the genus Arthrophytum to detect and identify their chemical components (using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)), demonstrated the value of their metabolite composition. The analysis showed that the studied taxa are characterised by a rich pool of isoprenoids, including terpenes, sterols, tocopherols and squalene, as well as lipid components of cuticular coatings — fatty acids and long-chain alcohols. It was found that isoprenoids dominate in all studied species, especially in A. subulifolium and A. longibracteatum. A. iliense is distinguished by a high content of carbonyl and aromatic compounds, while A. longibracteatum and A. lehmannianum are characterised by an increased content of fatty acids and long-chain alcohols. Common metabolites — β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, vitamin E, squalene, and carophyllene — form the conservative biochemical core of the genus. Thus, the results obtained for the first time demonstrate the chemotaxonomic and functional features of relict species of the genus Arthrophytum and open up prospects for their further study and use in the pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and aromatic industries.

Keywords:

Introduction

Results

Distribution Analyses

| № | Species | N | E | Administrative districts | Voucher |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A. lehmannianum | 47.133605 | 67.169902 | Ulytau region | 0003631 |

| 2 | A. iliense | 43.982948 | 79.242801 | Almaty Region, along the highway towards Chundzha | 0003629 |

| 3 | A. longibracteatum | 43.46725749 | 78.97789255 | Almaty Region, along the highway towards Chundzha | 0003635 |

| 4 | A. subulifolium | 43.57220281 | 70.91093101 | Zhambyl Region, Akkol | 0003622 |

| 5 | A. betpakdalense | 46.822778 | 75.008056 | Karaganda Region, 1 km from the city of Balkhash | 0003621 |

Morphological Analysis

Photochemical Analysis

Class Composition of Volatile Components by Arthrophytum Species

Discussion

Correlation with Biological Effects from Reviews

Ecological and Methodological Factors of Variability

Material and Methods

Geobotany Methods

Morphological Methods

Chemical Methods

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| № | Retention time, min | Compounds | Content, % | RMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18,24 | Caryophyllene | 0,91 | 0,11 |

| 2 | 18,95 | 4-Methyl-1-(acetoxy)benzene | 3,23 | 0,20 |

| 3 | 23,98 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1,10 | 0,20 |

| 4 | 24,61 | Guanosine | 3,93 | 0,15 |

| 5 | 26,01 | D-Glucopyranose, 1,6-anhydro- | 0,96 | 0,29 |

| 6 | 29,20 | Mome inositol | 2,81 | 0,19 |

| 7 | 30,40 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | 6,70 | 0,20 |

| 8 | 32,69 | Phytol | 1,00 | 0,26 |

| 9 | 33,21 | Dimethyl 6-(trimethylsilyl)pyrazolo [1,5-a]pyridine-2,3-dicarboxylate | 0,37 | 0,11 |

| 10 | 34,10 | cis-Vaccenic acid | 1,19 | 0,28 |

| 11 | 34,42 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid | 0,76 | 0,17 |

| 12 | 34,80 | Oxirane, hexadecyl- | 0,52 | 0,17 |

| 13 | 35,80 | 1-Octadecanol | 1,53 | 0,16 |

| 14 | 36,49 | Tetradecanal | 0,37 | 0,05 |

| 15 | 37,26 | Octacosane | 0,95 | 0,22 |

| 16 | 38,11 | Hexadecanal | 0,78 | 0,07 |

| 17 | 39,04 | Behenic alcohol | 3,16 | 0,25 |

| 18 | 40,30 | Octacosane | 1,08 | 0,18 |

| 19 | 41,17 | Octadecanal | 2,12 | 0,17 |

| 20 | 42,06 | Lignoceric alcohol | 9,33 | 0,29 |

| 21 | 43,13 | Hexatriacontane | 1,33 | 0,32 |

| 22 | 44,03 | Octadecanal | 3,83 | 0,30 |

| 23 | 44,22 | Squalene | 4,62 | 0,16 |

| 24 | 44,86 | n-Tetracosanol-1 | 10,57 | 0,62 |

| 25 | 45,46 | 1,6,10,14-Hexadecatetraen-3-ol, 3,7,11,15-tetramethyl- | 1,02 | 0,30 |

| 26 | 45,77 | Tetratetracontane | 0,89 | 0,28 |

| 27 | 46,11 | 1-docosanol | 0,38 | 0,04 |

| 28 | 46,70 | Oxirane, heptadecyl- | 9,94 | 0,75 |

| 29 | 47,49 | Octacosanol | 10,51 | 0,77 |

| 30 | 49,19 | 1,30-Triacontanediol | 2,72 | 0,20 |

| 31 | 50,08 | Vitamin E | 2,97 | 0,16 |

| 32 | 52,59 | Stigmasterol | 2,03 | 0,24 |

| 33 | 53,57 | β-Sitosterol | 6,39 | 0,44 |

| № | Retention time, min | Compounds | Content,% | RMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18,23 | Caryophyllene | 1,22 | 0,11 |

| 2 | 18,93 | 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol | 8,08 | 0,06 |

| 3 | 21,10 | Phenol, 2,6-dimethoxy- | 1,10 | 0,06 |

| 4 | 23,98 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1,57 | 0,09 |

| 5 | 24,14 | 2-methoxy-4-(n-propyl)phenol v | 0,82 | 0,10 |

| 6 | 24,58 | Coumarin | 4,10 | 0,06 |

| 7 | 24,81 | Ethanone, 1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)- | 1,51 | 0,10 |

| 8 | 25,81 | 2-Propanone, 1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)- | 0,81 | 0,10 |

| 9 | 25,89 | 3,7,11,15-Tetramethyl-2-hexadecen-1-ol | 0,60 | 0,06 |

| 10 | 26,00 | D-Allose | 1,40 | 0,10 |

| 11 | 26,19 | 2H-1-Benzopyran-3,4-diol, 2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-3,4-dihydro-6-methyl-, (2α,3α,4α)- | 0,42 | 0,05 |

| 12 | 26,41 | Tetradecanoic acid | 1,08 | 0,07 |

| 13 | 26,96 | 2(1H)-Pyridinone, 1-cyclohexyl-3,4,5,6-tetramethyl- | 0,94 | 0,11 |

| 14 | 27,40 | 2-Pentadecanone, 6,10,14-trimethyl- | 0,56 | 0,15 |

| 15 | 30,39 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | 9,54 | 0,41 |

| 16 | 34,10 | cis-Vaccenic acid | 6,26 | 0,30 |

| 17 | 34,42 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid | 4,02 | 0,20 |

| 18 | 35,79 | n-Heptadecanol-1 | 2,28 | 0,15 |

| 19 | 37,25 | Hexacosane | 2,49 | 0,06 |

| 20 | 38,11 | Octadecanal | 0,53 | 0,05 |

| 21 | 38,32 | 4,8,12,16-Tetramethylheptadecan-4-olide | 0,91 | 0,11 |

| 22 | 39,04 | Behenic alcohol | 3,42 | 0,25 |

| 23 | 40,29 | Hexacosane | 2,06 | 0,25 |

| 24 | 42,04 | n-Tetracosanol-1 | 8,23 | 0,13 |

| 25 | 43,12 | Octacosane | 3,19 | 0,10 |

| 26 | 44,20 | Squalene | 7,41 | 0,15 |

| 27 | 45,45 | 1,6,10,14-Hexadecatetraen-3-ol, 3,7,11,15-tetramethyl- | 2,58 | 0,20 |

| 28 | 45,77 | Hentriacontane | 2,95 | 0,10 |

| 29 | 46,18 | 9,19-Cycloergost-24(28)-en-3-ol, 4,14-dimethyl-, acetate, (3β,4α,5α)- | 1,29 | 0,20 |

| 30 | 46,50 | 1,6,10,14,18,22-Tetracosahexaen-3-ol, 2,6,10,15,19,23-hexamethyl- | 1,97 | 0,40 |

| 31 | 50,07 | Vitamin E | 2,73 | 0,15 |

| 32 | 52,57 | Stigmasterol | 4,05 | 0,03 |

| 33 | 53,55 | β-Sitosterol | 9,87 | 0,19 |

| № | Retention time, min | Compounds | Content,% | RMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18,23 | Caryophyllene | 2,23 | 0,06 |

| 2 | 19,02 | Ethanone, 1-(2-hydroxy-5-methylphenyl)- | 1,34 | 0,16 |

| 3 | 23,98 | Caryophyllene oxide | 2,45 | 0,31 |

| 4 | 24,57 | Sucrose | 9,78 | 0,25 |

| 5 | 25,90 | E-6-Octadecen-1-ol acetate | 0,41 | 0,09 |

| 6 | 27,40 | 2-Pentadecanone, 6,10,14-trimethyl- | 1,21 | 0,09 |

| 7 | 28,83 | n-Heptadecanol-1 | 0,41 | 0,09 |

| 8 | 30,38 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | 16,77 | 0,72 |

| 9 | 32,52 | Trichloroacetic acid, pentadecyl ester | 0,42 | 0,07 |

| 10 | 32,68 | Phytol | 1,29 | 0,12 |

| 11 | 32,96 | 9-Octadecenoic acid, methyl ester | 0,48 | 0,04 |

| 12 | 33,51 | Phthalic acid, 6-ethyl-3-octyl butyl ester | 0,41 | 0,08 |

| 13 | 34,10 | Oleic Acid | 7,05 | 0,22 |

| 14 | 34,42 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid | 5,73 | 0,21 |

| 15 | 34,79 | Tetradecanal | 1,20 | 0,10 |

| 16 | 35,79 | n-Heptadecanol-1 | 2,91 | 0,20 |

| 17 | 37,25 | Heptadecane | 1,63 | 0,16 |

| 18 | 38,10 | Pentadecanal- | 1,41 | 0,10 |

| 19 | 38,32 | 4,8,12,16-Tetramethylheptadecan-4-olide | 1,24 | 0,15 |

| 20 | 39,04 | 1-Nonadecene | 5,29 | 0,10 |

| 21 | 40,29 | Heptadecane | 1,51 | 0,08 |

| 22 | 41,17 | Tetradecanal | 1,63 | 0,11 |

| 23 | 42,05 | 1-Docosene | 7,30 | 0,09 |

| 24 | 43,12 | Hentriacontane | 1,83 | 0,06 |

| 25 | 44,20 | Squalene | 5,04 | 0,19 |

| 26 | 45,76 | Tetratetracontane | 1,22 | 0,07 |

| 27 | 46,49 | Oxirane, 2,2-dimethyl-3-(3,7,12,16,20-pentamethyl-3,7,11,15,19-heneicosapentaenyl)- | 2,33 | 0,15 |

| 28 | 50,06 | Vitamin E | 1,64 | 0,15 |

| 29 | 52,58 | Stigmasterol | 3,09 | 0,21 |

| 30 | 53,55 | β-Sitosterol | 10,75 | 0,58 |

| № | Retention time, min | Compounds | Content,% | RMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18,24 | Caryophyllene | 1,28 | 0,25 |

| 2 | 23,98 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1,39 | 0,09 |

| 3 | 27,42 | 2-Pentadecanone, 6,10,14-trimethyl- | 1,26 | 0,15 |

| 4 | 32,27 | 7,9-Di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro(4,5)deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione | 1,09 | 0,20 |

| 5 | 33,20 | Indazol-4-one, 3,6,6-trimethyl-1-phthalazin-1-yl-1,5,6,7-tetrahydro- | 1,96 | 0,12 |

| 6 | 33,53 | Phthalic acid, butyl isohexyl ester | 0,69 | 0,10 |

| 7 | 35,80 | 1-Eicosanol | 2,49 | 0,26 |

| 8 | 37,26 | Heptadecane | 3,25 | 0,15 |

| 9 | 38,11 | Tetradecanal | 1,14 | 0,11 |

| 10 | 38,33 | 4,8,12,16-Tetramethylheptadecan-4-olide | 1,26 | 0,15 |

| 11 | 38,37 | Hexanedioic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester | 1,03 | 0,16 |

| 12 | 39,05 | 1-Heneicosyl formate | 5,24 | 0,07 |

| 13 | 40,29 | Octacosane | 3,82 | 0,27 |

| 14 | 41,17 | Hexadecanal | 1,04 | 0,15 |

| 15 | 42,05 | 1-Eicosanol | 5,36 | 0,15 |

| 16 | 42,16 | 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, diisooctyl ester | 4,00 | 0,10 |

| 17 | 43,12 | Hentriacontane | 4,31 | 0,12 |

| 18 | 44,20 | Squalene | 8,00 | 0,20 |

| 19 | 45,76 | Heneicosane | 3,03 | 0,11 |

| 20 | 46,49 | Oxirane, 2,2-dimethyl-3-(3,7,12,16,20-pentamethyl-3,7,11,15,19-heneicosapentaenyl)- | 3,11 | 0,10 |

| 21 | 50,07 | Vitamin E | 5,31 | 0,08 |

| 22 | 52,58 | Stigmasterol | 8,52 | 0,07 |

| 23 | 53,55 | β-Sitosterol | 22,13 | 0,32 |

| 24 | 56,60 | Stigmasta-3,5-dien-7-one | 5,16 | 0,15 |

| 25 | 57,37 | Stigmast-4-en-3-one | 4,14 | 0,14 |

| № | Retention time, min | Compounds | Content,% | RMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13,36 | 2,6-Octadienal, 3,7-dimethyl- | 0,82 | 0,07 |

| 2 | 14,53 | Benzenemethanol, α,α,4-trimethyl- | 2,01 | 0,09 |

| 3 | 15,41 | Bicyclo [3.1.1]hept-3-en-2-one, 4,6,6-trimethyl- | 1,53 | 0,06 |

| 4 | 16,51 | 2-Cyclohexen-1-one, 3-methyl-6-(1-methylethyl)- | 1,83 | 0,06 |

| 5 | 18,11 | Ylangene | 0,32 | 0,07 |

| 6 | 18,23 | Caryophyllene | 5,41 | 0,27 |

| 7 | 19,74 | 2H-Inden-2-one, 1,4,5,6,7,7a-hexahydro-7a-methyl-, (S)- | 2,80 | 0,20 |

| 8 | 20,20 | 1,6-Cyclodecadiene, 1-methyl-5-methylene-8-(1-methylethyl)-, [s-(E,E)]- | 0,69 | 0,02 |

| 9 | 20,42 | 3-Cyclopenten-1-one, 2-hydroxy-3-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)- | 1,42 | 0,07 |

| 10 | 23,84 | 1H-Cycloprop[e]azulen-7-ol, decahydro-1,1,7-trimethyl-4-methylene-, [1ar-(1aα,4aα,7β,7aβ,7bα)]- | 1,21 | 0,09 |

| 11 | 23,97 | Caryophyllene oxide | 3,42 | 0,07 |

| 12 | 24,54 | Sucrose | 1,85 | 0,13 |

| 13 | 25,90 | 3,7,11,15-Tetramethyl-2-hexadecen-1-ol | 1,21 | 0,08 |

| 14 | 27,40 | 2-Pentadecanone, 6,10,14-trimethyl- | 0,51 | 0,10 |

| 15 | 30,43 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | 3,35 | 0,15 |

| 16 | 32,26 | 7,9-Di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro(4,5)deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione | 0,52 | 0,11 |

| 17 | 32,52 | 1-Nonadecene | 0,21 | 0,02 |

| 18 | 32,68 | Phytol | 0,51 | 0,10 |

| 19 | 33,52 | Phthalic acid, butyl cycloheptyl ester | 0,27 | 0,03 |

| 20 | 34,80 | Hexadecanal | 0,32 | 0,03 |

| 21 | 35,78 | Behenic alcohol | 5,11 | 0,20 |

| 22 | 37,26 | Heneicosane | 1,17 | 0,15 |

| 23 | 38,32 | 4,8,12,16-Tetramethylheptadecan-4-olide | 0,89 | 0,04 |

| 24 | 38,80 | Tetradecane, 2,6,10-trimethyl- | 0,41 | 0,08 |

| 25 | 39,03 | Behenic alcohol | 4,19 | 0,09 |

| 26 | 40,29 | Octacosane | 1,65 | 0,15 |

| 27 | 41,17 | Tetradecanal | 0,44 | 0,06 |

| 28 | 42,04 | n-Tetracosanol-1 | 9,25 | 0,17 |

| 29 | 43,11 | Hentriacontane | 1,11 | 0,10 |

| 30 | 43,45 | 1-Docosanol, acetate | 0,64 | 0,07 |

| 31 | 44,02 | Oxirane, hexadecyl- | 0,74 | 0,05 |

| 32 | 44,20 | Squalene | 0,37 | 0,05 |

| 33 | 44,85 | 1-Octacosanol | 15,53 | 0,15 |

| 34 | 45,76 | Tetratetracontane | 1,30 | 0,10 |

| 35 | 46,11 | Triacontyl acetate | 0,50 | 0,01 |

| 36 | 46,67 | Hexadecanal | 1,50 | 0,10 |

| 37 | 47,47 | 1-Octacosanol | 9,69 | 0,19 |

| 38 | 50,06 | Vitamin E | 1,08 | 0,07 |

| 39 | 52,57 | Stigmasterol | 2,14 | 0,15 |

| 40 | 53,56 | β-Sitosterol | 8,50 | 0,10 |

| 41 | 55,11 | Stigmast-7-en-3-ol, (3β,5α,24S)- | 1,42 | 0,14 |

| 42 | 56,60 | Stigmasta-3,5-dien-7-one | 2,17 | 0,16 |

Appendix B

References

- Osmonali, B.B.; Vesselova, P.V.; Kudabayeva, G.M.; Ussen, S.; Abdildanov, D.Sh.; Friesen, N. Contributions to the flora of Kazakhstan, genera Arthrophytum and Haloxylon. Plant Systematics and Evolution 2025, 311, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubentayev, S.A.; Alibekov, D.T; Perezhogin, Y.V.; Lazkov, G.A.; Kupriyanov, A.N.; Ebel, A.L.; Kubentayeva, B.B. Revised checklist of endemic vascular plants of Kazakhstan. PhytoKeys 2024, 238, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseyni M., S.; Safaie, N.; Soltani, J.; Pasdaran, A. Endophytic association of bioactive and halotolerant Humicola fuscoatra with halophytic plants, and its capability of producing anthraquinone and anthranol derivatives. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.; Huang, B. Mechanism of salinity tolerance in plants: physiological, biochemical, and molecular characterization. International journal of genomics 2014, 701596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanković, M.; Jakovljević, D. Phytochemical diversity of halophytes. In Handbook of Halophytes: From Molecules to Ecosystems towards Biosaline Agriculture; 2021; pp. 2089–2114.

- Arya S., S.; Devi, S.; Ram, K.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, N.; Mann, A.; Chand, G. Halophytes: The plants of therapeutic medicine. Ecophysiology, abiotic stress responses and utilization of halophytes 2019, 271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Ksouri, R.; Ksouri, W.M.; Jallali, I.; Debez, A.; Magne, C.; Isoda, H.; Abdelly, C. Medicinal halophytes: potent source of health promoting biomolecules with medical, nutraceutical and food applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2011, 32, 289–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todorović, M.; Zlatić, N.; Bojović, B.; Kanjevac, M. Biological properties of selected Amaranthaceae halophytic species: A review. Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 58, e21229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, N.V. Flora of Kazakhstan, Vol. 3. Academy of Sciences of the Kazakh SSR, Alma-Ata, 1960, 460 pp. [In Russian].

- Polyakov P.P.; Goloskokov V.P. Family Chenopodiaceae. In The Flora of Kazakhstan, 3rd, ed.; Pavlov, P.P. Ed.; Academy of Sciences of the Kazakh SSR: Alma-Ata, Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, 1960, pp. 179–320. [In Russian].

- Pratov, U.; Bondarenko, O.N.; Nabiev, M.M. Family Chenopodiaceae. In The Plant Identifier of Plants of Central Asia, III; FAN Publishing House: Tashkent, USSR, 1972, pp. 29–137. [In Russian].

- Sukhorukov, A.P.; Kushunina, M.A.; Stepanova, N.Y.; Kalmykova, O.G.; Golovanov, Y.M.; Sennikov, A.N. Taxonomic inventory and distributions of Chenopodiaceae (Amaranthaceae sl) in Orenburg Region, Russia. Biodiversity Data Journal. 2024, 12, e121541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddour, S.M.; Arrar, L.; Baghiani, A.; et al. Acute, sub-acute and antioxidant activities of Arthrophytum scoparium aerial parts. International journal of pharmaceutical sciences and research, 2019, 10, 4167–4175. [Google Scholar]

- Dif, M.M. Phytochemical study of phenolic compounds and biological activities of Arthrophytum schmittianum. Journal of Horticulture, Forestry and Biotechnology 2022, 26, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, H.C.; Najjaa, H.; Villareal, M.O.; Ksouri, R.; Han, J.; Neffati, M.; Isoda, H. Arthrophytum scoparium inhibits melanogenesis through the down-regulation of tyrosinase and melanogenic gene expressions in B16 melanoma cells. Experimental Dermatology. 2013, 22, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snieckus, V. The distribution of indole alkaloids in plants. In: The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Physiology. 2014, Vol. 11.

- Glasby, J.S. Encyclopedia of the Alkaloids. New York: Plenum Press, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Belabdelli, F. ; Phytoconstituents effects of traditionally used herbs on dissolution and inhibition of kidney stones (CaOx). Farmacia. 2023, 71, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataev, E.A. On some plant communities in the Kugitangtau piedmont plain and their relationship with soil type. Izvestiya Akademii Nauk Turkmenskoi SSR, Biologicheskikh Nauk, 1973, (37–41).

- Smach, M.A. Arthrophytum scoparium extract improves memory impairment and affects acetylcholinesterase activity in mice brain. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology 2020, 21, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaddour, S.M.; Arrar, L.; Baghiani, A. ; Anti-inflammatory potential evaluation (in-vitro and in-vivo) of Arthrophytum scoparium aerial part. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics 2020, 10, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, M.N. Investigation of alkaloids of Anabasis aphylla (Chenopodiaceae). Ibn Al-Haitham Journal for Pure and Applied Sciences 2010, 23, 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Shakeri, A. Phytochemical screening, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Anabasis aphylla L. extracts. Kragujevac Journal of Science 2012, 34, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ouadja, B.; Katawa, G.; Toudji, G.A.; Layland, L.; Gbekley, E.H.; Ritter, M.; Karou, S.D. Anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. (Chenopodiaceae) extracts. Journal of Applied Biosciences 2021, 162, 16764–16794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohra, M.; Fawzia, A. Hemolytic activity of different herbal extracts used in Algeria. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 2014, 5, 495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Boubrima, Y. Inhibitory effect of phenolic extracts of four Algerian Atlas Saharan plants on α-glucosidase activity. Current Enzyme Inhibition 2018, 14, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalai F.Z. Antioxidant and antiadipogenic potential of four Tunisian extremophiles (Mesembryanthemum edule, Atriplex inflata, Rantherium suaveolens, Arthrophytum scoparium). Advances in Nutrition and Food Science 2022, Article ID: ANAFS-229.

- Benslama, A.; Harrar, A. Free radicals scavenging activity and reducing power of two Algerian Sahara medicinal plants extracts. International Journal of Herbal Medicine 2016, 4, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datkhayev, U. GC–MS analysis, HPLC–UV analysis, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of extracts of wild-growing Anabasis salsa native to Kazakhstan desert lands. Phytochemistry Reviews 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadaf, M. ,Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of different Iranian populations of Anabasis aphylla L. Natural Product Research 2024, 38, 1606–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shegebayev, Z. Pharmacological properties of four plant species of the genus Anabasis (Amaranthaceae). Molecules 2023, 28, 4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.J. Spatial heterogeneity of soil chemical properties between Haloxylon persicum and Haloxylon ammodendron populations. Journal of Arid Land 2010, 2, 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Tleubayeva M.I.; Abdullabekova R.M.; Datkhayev U.; Ishmuratova M.Y.; Alimzhanova M.B.; Kozhanova K.K.; Seitaliyeva A.M.; Zhakipbekov K.S.; Iskakova Z.B.; Serikbayeva E.A.; Flisyuk E.V. Investigation of CO2Extract of Portulaca oleracea for Antioxidant Activity from Raw Material Cultivated in Kazakhstan. International Journal of Biomaterials 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ikhsanov, Y.S.; Nauryzbaev, M.; Musabekova, A.; Alimzhanova, M.; Burashev, E. Study of Nicotiana tabacum L extraction, by methods of liquid and supercritical fluid extraction. Journal of Applied Engineering Science 2019, 17, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toderich, K.N.; Terletskaya, N.V.; Zorbekova, A.N.; Saidova, L.T.; Ashimuly, K.; Mamirova, A.; Shuyskaya, E.V. Abiotic stresses utilisation for altering the natural antioxidant biosynthesis in Chenopodium quinoa L. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology 2023, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmonali, B.B.; Vesselova, P.V.; Kudabayeva, G.M.; Duisenbayev, S.; Taukebayev, O.; Zulpykharov, K. . & Abdiildanov D.S. Salt resistance of species of the Chenopodiaceae family (Amaranthaceae sl) in the desert part of the Syrdarya River Valley, Kazakhstan. Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity 2024, 25. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).