1. Introduction

Matricaria chamomilla L., sin.

Chamomilla recutita (L.) Rauschert (German chamomile) is an annual species widely cultivated across Europe, Asia, and the Americas. It thrives in well-drained, moderately fertile soil, and is commonly found in cultivated fields and gardens, but also in wild areas [

1]. In contrast,

Tripleurospermum inodorum (syn.

Matricaria inodora), commonly known as scentless mayweed, or scentless chamomile, is a ruderal species that grows spontaneously in uncultivated lands, field margins, and roadsides. It is often considered an invasive weed, being highly adaptable to diverse environmental conditions [

2].

Although both species belong to Asteraceae family and display capitulate inflorescences, they exhibit significant morphological differences.

Matricaria chamomilla (

M. chamomilla) has erect stems, pinnatisect leaves, and a hollow, conical receptacle, bearing white ligulate florets and yellow tubular disc florets [

1,

3]. In contrast,

Matricaria inodora sin.

Tripleurospermum inodorum (

T. inodorum) features more finely divided, feathery leaves and a solid receptacle. Its inflorescences are similar in appearance but lack the characteristic aroma of true chamomile, which is a key trait for accurate identification [

2].

The chemical composition of

M. chamomilla has been extensively studied and is characterized by a rich and complex profile of secondary metabolites. The essential oil of chamomile typically contains α-bisabolol, chamazulene, matricin, bisabolol oxides A and B, β-

farnesene, and spathulenol [

3]. These constituents vary depending on the plant’s origin, geographical position, harvesting time, and extraction method. Based on the main component of the essential oils, there are few chemotypes of chamomile: type A (bisabolol oxide A predominant), type B (bisabolol oxide B predominant), type C (alpha-bisabolol predominant), and type D (α-bisabolol, and α-bisabolol oxide A and B in 1:1 ratio) [

4,

5].

Among the flavonoids found in large amounts in chamomile, apigenin, apigenin-7-O-glucoside, luteolin, patuletin, and quercetin are included. Other notable biocomponds are phenolic acids (caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, and ferulic acid), coumarins (herniarin, umbelliferone), mucilages, polysaccharides, small amounts of tannins and bitter substances (matricarin) [

6,

7]. These constituents contribute to its numerous pharmacological effects.

Preparations from

M. chamomilla are traditionally used for their anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic, sedative, carminative, and antiseptic properties. Chamomile is administered as teas, infusions, tinctures, or essential oils for gastrointestinal disorders, anxiety, skin irritations, and mucosal inflammation [

3]. Recent clinical studies have highlighted the therapeutic potential of

M. chamomilla in anxiety, insomnia, and inflammation-related conditions. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed that chamomile extract significantly reduced anxiety symptoms in patients with generalized anxiety disorder [

8]. A follow-up study confirmed its role in preventing relapses and improving long-term well-being [

9]. Additionally, a meta-analysis found that chamomile improved sleep quality and reduced night-time awakenings [

10]. Topical chamomile oil has also shown benefits in reducing pain and inflammation in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome [

11].

M. chamomilla is generally considered safe, with low toxicity, although allergic reactions may occur in individuals sensitive to Asteraceae species. Potential interactions with anticoagulants have also been noted [

12].

T. inodorum is less chemically and pharmacologically studied species. So far it is known that it contains a significantly lower amount of essential oil, typically below 0.05%, and the composition varies. Unlike

M. chamomilla, it lacks chamazulene and α-bisabolol. Identified constituents include α-pinene, limonene, β-myrcene [

13,

14], artemisia ketone, terpinene-4-ol, 1,8-cineole, sabinene, tricosane [

2], and matricaria ester [

15]. Other components are flavonoids (apigenin, luteolin, quercetin, kaempferol, and isorhamnetin derivatives), phenolic acids (caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, quinic acid, 5-

O-caffeoyl quinic acid, and protocatechuic acid), tannins and terpenoids, and smaller doses of sesquiterpene lactones than chamomile [

2,

7]. Nonetheless, its phytochemical profile remains less characterized and more variable.

T. inodorum is rarely cited in traditional medicine. Few studies have reported antioxidant activity [

14,

15], alleviating gastrointestinal pain and anti-inflammatory properties [

16], but its therapeutic relevance remains uncertain due to low concentrations of active constituents. Regarding

T. inodorum, there is limited data on toxicity, but it is typically regarded as non-toxic, with low allergenic potential.

The aim of this study was to provide a comparative evaluation of the bioactive compounds of two chamomile species: M. chamomilla and T. inodorum, including total polyphenols, flavonoids, and volatile constituents from the essential oils, analyzed by GC-MS, and to explore how these bioactive compounds contribute to antioxidant and antimicrobial activities.

2. Materials and Methods

Flowers at full maturity or floral buds from the two chamomile species were collected in May 2025 in the village of Dumitresti, Vrancea County, Romania. The studied species included Matricaria chamomilla L. (chamomile, German chamomile, blue chamomile), and Matricaria inodora L. sin. Tripleurospermum inodorum (L.) Sch.Bip. (scentlesss mayweed, scentless chamomile). Species identification was performed at the Botany Laboratory of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Titu Maiorescu University.

For the total phenolic and flavonoid content, and for the determination of antioxidant capacity, the plant material was air-dried at room temperature in the absence of direct light, then finely ground. Ethanolic extracts were obtained by refluxing 1 gram of the dried material with 100 mL of 50% ethanol for 30 minutes at 100 °C using an electric water bath (Witeg Labortechnik, Wertheim, Germany). The resulting mixtures were filtered through a Whatman ashless filter paper, and the final volumes were adjusted to 100 mL with the same solvent in a graduated flask. The two extracts were stored at 4 °C until the analyses were performed.

2.1. Botanical Examination

For morphological observation representative capitula of both species were selected and dissected. Floral parts—including ray and disc florets, receptacle structure—were examined and photographed using a Motic BA310 optical microscope equipped with an integrated Motic digital imaging system (Motic Microscopes, Kowloon, Hong Kong). Observations were conducted under brightfield illumination at magnifications ranging from ×10 to ×100. Morphological characteristics such as floret arrangement, symmetry, corolla type, and receptacle shape were recorded for each species. Comparative measurements of floral structures were taken, and taxonomic identification was confirmed with standard floristic keys and herbarium references.

For pollen analysis of the plants, mature anthers from fully developed disc florets were carefully removed and mounted on glass slides. Samples were analyzed under the same optical microscope Motic BA310 at ×100 magnification (Motic Microscopes, Kowloon, Hong Kong). Parameters such as pollen shape, size (polar and equatorial diameter), aperture number and type (colpi and pori), and exine ornamentation were analyzed. Measurements were performed on at least 10 pollen grains per species. Pollen grains were described following Erdtman’s system, and the terminology following standard palynological nomenclature [

17,

18].

2.2. Phytochemical Investigations

2.2.1. Total Phenolic Content

The total polyphenolic content of the two species was determined using a spectrophotometric method based on the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, with gallic acid employed as calibration standards, as previously described [

19,

20].

Briefly, 1 mL of each hydroethanolic extract (M. chamomilla and T. inodorum flowers) was mixed with 4.5 mL of deionized water and 2.5 mL of a diluted Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). After 5 minutes, 2 mL of 7% (w/v) sodium carbonate solution was added to the mixture. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature, protected from light. Absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a VWR UV-6300 PC spectrophotometer (VWR International, Wien, Austria).

The total polyphenolic content was quantified using calibration curves constructed with standard solutions of gallic acid (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MI, USA), with R² = 0.999728 and the following regression equation:

Results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry weight (mg GAE/g DW). All measurements were conducted in triplicate, and data were reported as mean ± standard deviation.

2.2.2. Total Flavonoid Content

For the determination of total flavonoid content, the spectrophotometric method with aluminum chloride in the presence of sodium acetate was used, as described in the 10th edition of the Romanian Pharmacopoeia, where the absorbance of the yellow complex formed allows quantification of total flavonoids [

21].

10 mL of ethanolic extracts of the two species were diluted with methanol in 25 mL volumetric flasks and filtered. To 5 mL of the diluted extract solutions, 5 mL of 100 g/L sodium acetate solution (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MI, USA), and 3 mL of 25 g/L aluminum chloride solution (Merck Group, Darmstadt, Germany) were added, then topped up with methanol in 25 mL volumetric flasks and the mixture was homogenized. The samples were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature and absorbance was measured at 430 nm using a VWR UV-6300 PC spectrophotometer (VWR International, Wien, Austria), using a calibration curve made with rutin (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MI, USA).

The results were expressed as mg rutin equivalent per gram dry weight (mg RE/g DW) ± standard deviation, as the measurements were carried out in triplicate.

2.2.3. Essential Oil Extraction and GC/MS Analysis

Freshly ground chamomile and scentless mayweed (150 g) were subjected to hydrodistillation in a closed-loop system using a glass Clevenger-type apparatus for 3 hours. The extraction was performed with 600 mL of distilled water, following the volumetric assay method described in the 10th edition of the European Pharmacopoeia [

22]. This procedure was conducted in triplicate for each species to ensure consistency of results.

The essential oil yield was calculated as a percentage (% v/w), based on the volume of oil obtained relative to the mass of plant material.

Subsequently, the chemical composition of each essential oil was determined using Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS). The analysis was performed using a Thermo Electron Corporation Focus gas chromatograph equipped with a splitter and coupled to a Thermo Electron Corporation DSQII mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The capillary column was coated with Macrogol 20,000 (Ohio Valey, OH, USA), with a film thickness of 0.25 µm, a length of 30 m, and an internal diameter of 0.25 mm. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. The injection volume was 1.0 µL, and the column oven temperature was programmed to increase from 65 °C to 200 °C, over a 60-minute run time [

23]. Quantification of components was based on integration of peak areas in the chromatograms, and compound identification was achieved by comparing the obtained mass spectra with reference spectra from the Wiley 8 and NIST 07 databases.

2.3. Biological Activity Assays

2.3.1. Antioxidant Capacity

The antioxidant activity of the two flowers extracts was evaluated using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay. This widely used method is based on the reduction of the stable, violet-colored DPPH radical by antioxidants capable of donating electrons or hydrogen atoms, resulting in a color change from deep purple to pale yellow as the radical is neutralized [

20].

For the preparation of the DPPH solution, 100 mg of DPPH (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MI, USA) was dissolved in methanol and brought to volume in a 200 mL volumetric flask. 1 mL of extract was combined with 5 mL of the DPPH solution and methanol was added to reach a final volume of 25 mL. The mixture was thoroughly homogenized and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark to prevent photo-degradation of the radical.

After incubation, the absorbance of the solution was measured at 517 nm using a VWR UV-6300 PC spectrophotometer (VWR International, Wien, Austria). The radical scavenging activity was calculated using the following equation:

where Abs control represents the absorbance of the DPPH solution without extract, and Abs sample represents the absorbance of the DPPH solution containing the sample.

The IC₅₀ value, indicating the concentration needed to inhibit DPPH radical activity by half, was used to express the antioxidant capacity of the samples.

2.3.2. Antimicrobial Activity

Antimicrobial activity was evaluated against reference strains:

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923,

Escherichia coli ATCC 35218),

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853), and

Candida albicans (ATCC 10231). Bacteria were cultured on Plate Count Agar at 37 °C for 22 ± 2 h. The antimicrobial effect of the oils was assessed by the Kirby–Bauer diffusion method under standardized, reproducible conditions [

24,

25].

Mueller–Hinton agar plates were inoculated with a 0.5 McFarland suspension (OD550 = 0.125) of each strain, and essential oils were applied in spots of 5–30 µL. After pre-diffusion (15 min), plates were incubated at 35 ± 2 °C for 16–18 h under aerobic conditions. Any inhibition zone was recorded as sensitivity (S), while its absence indicated resistance (R).

2.4. Statistical Data Processing

Statistical analyses were performed using XL STAT software. The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and differences were evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA). All experiments were conducted in triplicate

3. Results

3.1. Botanical Examination

The morphological examination indicates that both species exhibit capitulum-type inflorescences, specific to

Asteraceae family, but with distinct differences. In

M. chamomilla, the receptacle was conical and hollow, while in

T. inodorum the receptacle appeared flat and solid. This is a key taxonomic feature, that enables an accurate differentiation between the two species (

Figure 1). Moreover, ray florets in

M. chamomilla were ligulate, strap-shaped, having three teeth at apex, and white, while in

T. inodorum the ray florets were also white, strap-shaped, but more deeply three-lobed. The disc florets in

M. chamomilla were tubular, bright yellow colored, with prominent bifid stigmas, while in

T. inodorum they were golden-yellow, more compact, having a reduced stigma structure. Additional images of botanical examination are presented in

Supplementary Figure S1.

Pollen of

M. chamomilla appeared spheroidal, isopolar, and tricolporate, with a diameter of approximately 22–27 µm. The exine surface was finely reticulate, and the colpi were well defined, extending nearly the entire length of the grain. In contrast, pollen of

T. inodorum was similarly spheroidal, and tricolporate, but slightly larger, with a diameter of 25–30 µm. The exine ornamentation was coarser, and the colpi appeared smoother, and less defined compared to

M. chamomilla. Minor variations in aperture size and exine thickness were also observed. These palynological features also contribute to a more precise distinction between the two chamomile species, being used as supportive criteria for their identification. Additional data is provided in

Figure S2 (Supplementary Material).

Botanical differences of the two species are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Total Phenolic Content

Total polyphenol content of

M. chamomilla and

T. inodorum was determined using gallic acid (mg GAE) and caffeic acid (mg CAE) as reference standards. The results are expressed as equivalents per gram of dry weight (DW), as shown in

Table 2.

Analysis of the results indicates that M. chamomilla has the highest total polyphenol content, both in gallic acid equivalents (20.48 mg/g) and caffeic acid equivalents (20.10 mg/g). In comparison, T. inodorum showed lower values—17.88 mg/g (gallic acid) and 17.73 mg/g (caffeic acid), respectively. These differences in polyphenol content may be correlated with phytochemical composition variations between the two species, suggesting a higher antioxidant potential for chamomile flowers.

3.3. Total Flavonoid Content

The total flavone content of

M. chamomilla and

T. inodorum was determined and expressed as g% rutin equivalents, and the results are expressed relative to dry weight (DW), as shown in

Table 3.

The results showed values of 13.872 ± 0.009 mg/g for M. chamomilla and 15.925 ± 0.005 mg/g for T. inodorum. The flowers of T. inodorum contain slightly more flavonoids than those of M. chamomilla, which may contribute to a greater overall antioxidant capacity. Although M. chamomilla is traditionally regarded as the plant with stronger medicinal properties, the present results indicate that T. inodorum may also represent a valuable source of bioactive compounds, particularly flavonoids.

3.4. Hydrodistillation and GC/MS Analysis

Through hydrodistillation of two types of chamomile flowers, distinct essential oils were obtained.

The oil from M. chamomilla was characterized as a deep blue liquid, a feature attributed to the presence of chamazulene formed during the distillation process. Its aroma was strong, sweet, herbaceous, and slightly fruity. The essential oil content was 0.75 ± 0.008 mL per 100 g of plant material.

In contrast, the oil from T. inodorum appeared as a yellow liquid with considerably lower viscosity and a weakly herbaceous to camphoraceous odor. The essential oil content was 1.14 ± 0.007 mL per 100 g of plant material.

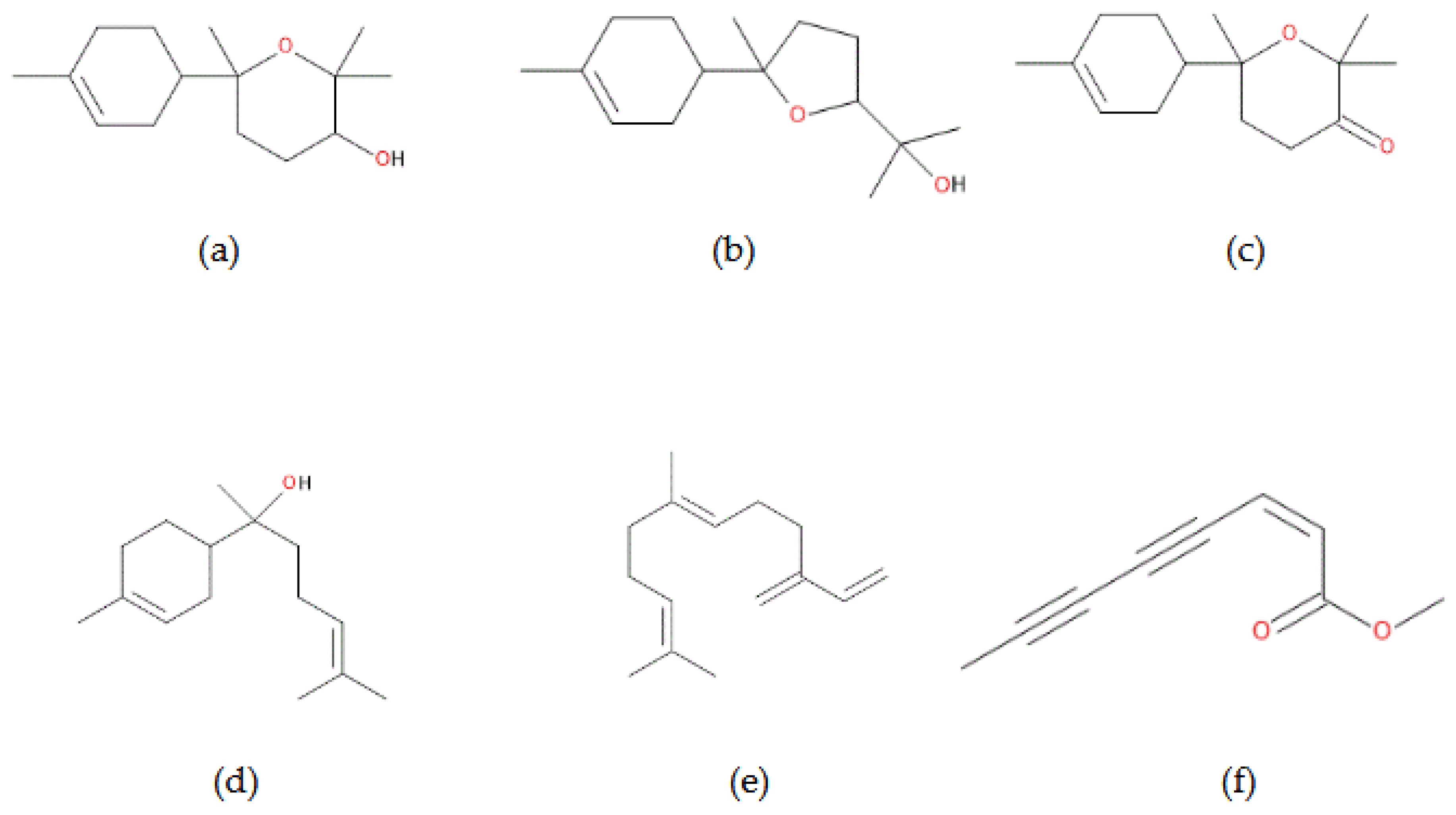

The essential oil of chamomile contains mostly oxygenated sesquiterpenes (76.80%), followed by other oxygenated/aromatic compounds (14.45%) and sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (8.71%). Among the identified bioactive compounds, the major ones are bisabolol oxide A (39.49 %), bisabolol oxide B (18.69 %), bisabolone oxide A (12.73 %), ß-farnesene (7.96 %), lachnophyllum ester, trans (6.18 %), and chamazulene (4.24 %) (

Figure 2). Based on its chemical profile, the chamomile profile can be classified as chemotype B, also found in Armenia or Albania [

4,

5,

26].

The essential oil of scentless chamomile has a different chemical profile, as revealed by GC-MS analysis. Thus, the major compounds are oxygenated and aromatic compounds (87.98%), with a smaller proportion of sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (11.56%). The predominant bioactive compounds discovered in this essential oil are 1,3-naphthalenediol (69.70 %), followed by lachnophyllum ester, cis (11.59 %), and ß-farnesene (11.56 %) (

Figure 2). While β-farnesene and cis-lachnophyllum ester were consistent with previous reports for

T. inodorum, the tentative identification of 1,3-naphthalenediol is unexpected due to its low volatility. This signal may instead reflect a possible identification or co-elution with semi-volatile compounds and thus requires cautious interpretation until further validation.

It can be observed that several compounds are present in both species, such as ß-farnesene, lachnophyllum ester, cis, and (Z)-1-[isobenzofuran-1-ylidene]propan-2-one, due to a similar metabolism along the course of evolution, both species belonging to the same taxonomic genus.

3.5. Antioxidant Capacity

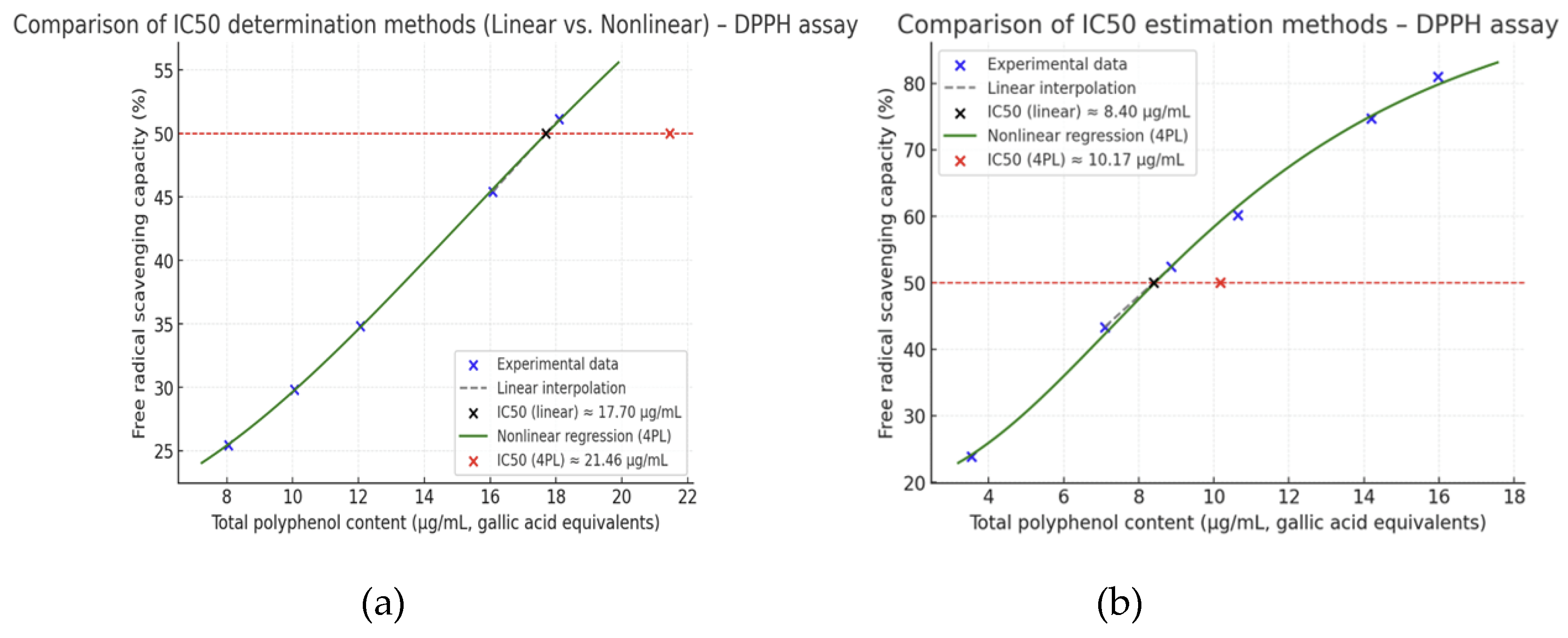

The antioxidant activity of the tested extract was evaluated by the DPPH assay, and the IC₅₀ values were calculated using both linear interpolation and nonlinear regression models. For

M. chamomilla, based on linear interpolation, the IC₅₀ was estimated at 17.7 µg/mL GAE, whereas the nonlinear 4-parameter logistic (4PL) regression provided a slightly higher value of 21.5 µg/mL GAE (

Figure 3). The graphical comparison of the two approaches highlights that the nonlinear model, which accounts for the sigmoidal nature of dose–response relationships, results in a more conservative estimate of IC₅₀ compared to the local linear approximation. These findings indicate that the extract exhibits a moderate free radical scavenging capacity, attributable to its polyphenolic constituents, and confirm the importance of applying appropriate regression models to obtain robust IC₅₀ values.

The IC₅₀ values determined for the extract of T. inodora highlight a moderate antioxidant potential. Using linear interpolation, the IC₅₀ was estimated at 8.40 µg/mL GAE, while nonlinear logistic regression (4PL) provided a slightly higher and more robust estimate of 10.17 µg/mL GAE (95% CI: 7.38–12.96 µg/mL).

The difference between linear and nonlinear estimates underlines the importance of applying regression models that account for the sigmoidal nature of dose–response relationships, particularly when extrapolating IC₅₀ values.

3.6. Antimicrobial Activity

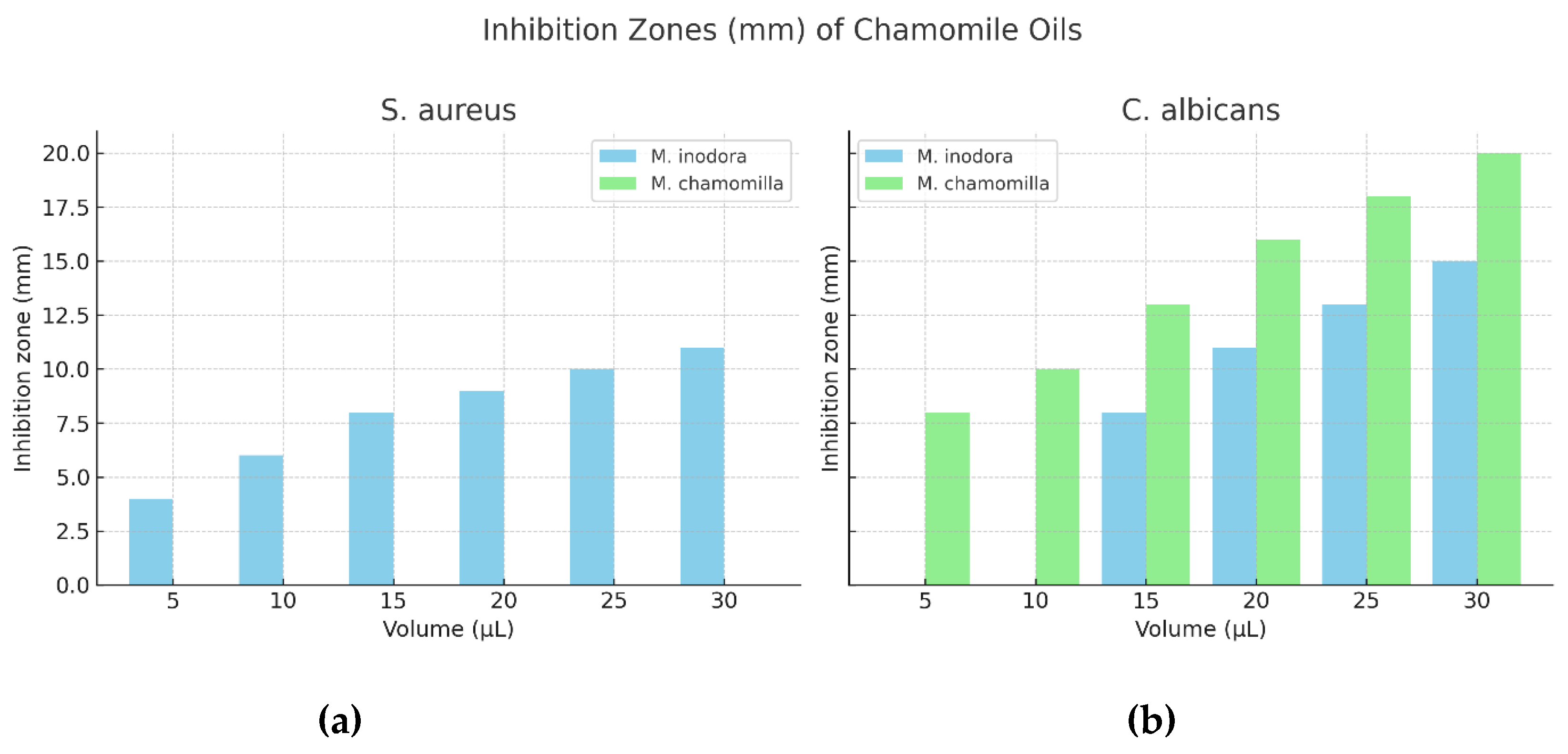

The antimicrobial assays revealed distinct differences between the two chamomile species. The essential oil obtained from T. inodorum exhibited both antibacterial activity against Gram-positive strains and antifungal activity against C. albicans (

Figure 4). Antibacterial effects were detected at all tested volumes (5–30 µL), while antifungal inhibition zones were evident at higher volumes (15–30 µL). In contrast, the oil from M. chamomilla displayed only antifungal activity, which was consistently observed across all tested volumes. These findings suggest a broader antimicrobial spectrum for T. inodorum, highlighting its potential as a more effective source of bioactive compounds compared to M. chamomilla.

4. Discussion

The comparative analysis of M. chamomilla and T. inodorum reveals that microscopic, phytochemical, and biological characteristics are closely interconnected, indicating that variations in structural features and chemical composition are reflected in their distinct antioxidant and antimicrobial activities.

This study highlights the diagnostic significance of both morphological and palynological characteristics in distinguishing the two species of chamomile. The observed differences in receptacle structure, ray florets and disc florets are consistent with previously reported taxonomic descriptions and represent reliable characters for species identification [

26,

27]. These findings underscore the value of detailed floral morphology for accurate species identification, for better knowing the plant material used for medicinal purposes. Palynological characteristics are consistent with previously published studies [

26,

28,

29], and provide reliable diagnostic features for accurate species authentication within the Asteraceae family.

Furthermore, the size, shape, and exine surface of pollen are also important in triggering seasonal allergies. Although allergic reactions to the pollen of these two species are rarely reported, cross-reactive IgE-mediated anaphylactic responses may occur, particularly in individuals sensitized to ragweed or mugwort pollen [

30]. Further research is needed to clarify the specific allergenic substances (haptenes), the significance of pollen morphology, and the underlying mechanisms by which these species may induce allergic responses.

Our findings confirm that both

M. chamomilla and

T. inodorum represent valuable sources of phenolic compounds and flavonoids, yet with distinct chemical signatures. The higher polyphenolic content in

M. chamomilla is consistent with recent reports highlighting its well-established antioxidant capacity [

3]. Interestingly, the comparatively higher flavonoid levels observed in

T. inodorum contrast with previous studies where

M. chamomilla was identified as the major flavonoid-rich taxon [

2], suggesting possible chemotypic variability or environmental influences on secondary metabolism. This aligns with recent work showing significant fluctuations in phenolic and flavonoid profiles of Asteraceae species depending on harvest season and geographic origin [

30].

The IC₅₀ value for M. chamomilla (17.7–21.5 µg/mL) indicates moderate antioxidant activity, consistent with its higher polyphenol content, and falls at the lower end of the wide range reported for chamomile extracts (13.15–73.35 µg/mL), confirming its relevance as a natural source of antioxidants. T. inodorum showed comparable IC₅₀ values (8.4–10.2 µg/mL), which may be attributed to its relatively higher flavonoid content. Although its potency does not approach that of classical antioxidants such as ascorbic acid or quercetin (IC₅₀ < 5 µg/mL), its activity is consistent with other medicinal plants of moderate radical-scavenging capacity. These findings underline the importance of considering both phenolic and flavonoid fractions when evaluating antioxidant potential, which is why the antioxidant capacity was assessed on hydroethanolic extracts, where such compounds are the main contributors to radical scavenging activity. In contrast, antimicrobial assays were performed on essential oils, rich in volatile terpenoids with well-documented antibacterial and antifungal effects. This complementary approach allowed us to capture the distinct bioactive potential of the polar versus volatile fractions of the two chamomile species.

Regarding the chemical composition of the two essential oils, the diversity of the identified bioactive compounds is notable, offering multiple possible therapeutical applications. Chemical profile of

M. chamomilla essential oil, with bisabolol oxide A as the major compound (39.49 %) placed this Romanian species in the chemotype B, as previously described by literature [

26]. Bisabolol oxides (A and B), as natural derivates of α- bisabolol, by oxidation, are known for their anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and wound-healing properties [

31]. Tomić et al highlighted the antihyperalgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antiedematous effects of a bisabolol-oxides-rich

Matricaria essential oil in a rat model of inflammation induced by carrageenan, dextran, and histamine [

32]. In another study, Alimi et al, revealed that bisabolol oxide A showed good activity against

Staphylococcus aureus,

Escherichia coli, and

Salmonella enteritidis, ovicidal and larvicidal against

Hyalomma scupense, and potent anti-acetylcholinesterase activity [

33]. A randomized controlled trial on 29 patients with chronic venous leg ulcers showed that a spray formulation containing ozonated oil and α-bisabolol used in topical treatment was significantly efficient in reducing the wound size and increasing the rate of complete ulcer closure [

34]. Two other major compounds, bisabolol oxide B (18.69%), and bisabolone oxide A (12.73 %), with biological activities comparable to bisabolol oxide A, further enhance the overall bioactivity of chamomile essential oil. β-Farnesene, beyond its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory potential, functions as an ecological signaling compound, acting as an alarm pheromone in certain insects and as a plant defense metabolite against herbivory [

35,

36]. Lachnophyllum ester, known for its antifungal activity against dermatophytes such as

Trichophyton rubrum and

Microsporum canis [

37], as well as for its significant antioxidant capacity, adds an important contribution to the bioactive profile of the essential oil. An important compound, found in the essential oil of chamomile, that gives its blue color, is chamazulene, a sesquiterpene derivate. In the Romanian analyzed sample, the chamazulene content (4.24%) falls within the range reported in the literature (2.3–10.9%) [

26]. Chamazulene is generated from matricin, during hydrodistillation, and has notable anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic, and antioxidant properties, thereby contributing significantly to the species pharmacological profile, along with the other compounds [

6,

38].

In contrast, the essential oil of

T. inodorum displays a comparatively simpler phytochemical profile, characterized by fewer bioactive constituents. Lachnophyllum ester, cis, a polyunsaturated fatty ester, as a major compound (11.59 %), provides significant contributions to the bioactive profile of the essential oil, through its antifungal and antioxidant activities. Interestingly, recent studies showed that lachnophyllum ester exhibit cytotoxic activity against MDA-MD-231, MCF-7, 5637 human tumor cells, and SK-MEL-28 melanoma cells, by increasing ROS production, which makes our plants candidates for anticancer therapy [

39,

40]. β-Farnesene, a sesquiterpene alkene accounting for 11.56% of the composition, is also known to function as a component of the aphid alarm pheromone. Apart from its ecological role, β-farnesene demonstrates biological properties such as anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective activities. Turkez et al noticed it has a dose-related neuroprotective action on cultured rat primary cortical neurons, reducing DNA damage, thus suggesting possible applications in neurodegenerative and oxidative stress related disorders [

41]. These diverse biological actions of the bioactive compounds from the two chamomile species suggest interest for both ecological agricultural applications, and for developing new therapeutic agents for human health.

The chemical composition differences of the essential oils are reflected in their biological activity, as shown by our results.

The broader antimicrobial spectrum of

T. inodora essential oil, active against both

S. aureus and

C. albicans, contrasts with the strictly antifungal effect of

M. chamomilla. This difference reflects their distinct chemotypes, with β-farnesene and lachnophyllum ester in

T. inodora linked to antimicrobial activity, while bisabolol derivatives in

M. chamomilla are primarily associated with anti-inflammatory and antifungal effects. Our findings are consistent with previous reports:

M. chamomilla oils are known to inhibit

Candida species, particularly due to α-bisabolol oxides and chamazulene, whereas

T. disciforme [421] and

T. inodorum extracts [

43,

44] demonstrated antibacterial and antifungal activity. Together, these results confirm that both volatile and polar fractions of

T. inodorum contribute to its antimicrobial potential, supporting its recognition as an underexplored source of bioactive metabolites.

Future research is needed to deepen the understanding of the chemical profiles of both chamomile species, identifying potential new pharmacological effects, and evaluate their safety and toxicity.