Submitted:

24 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

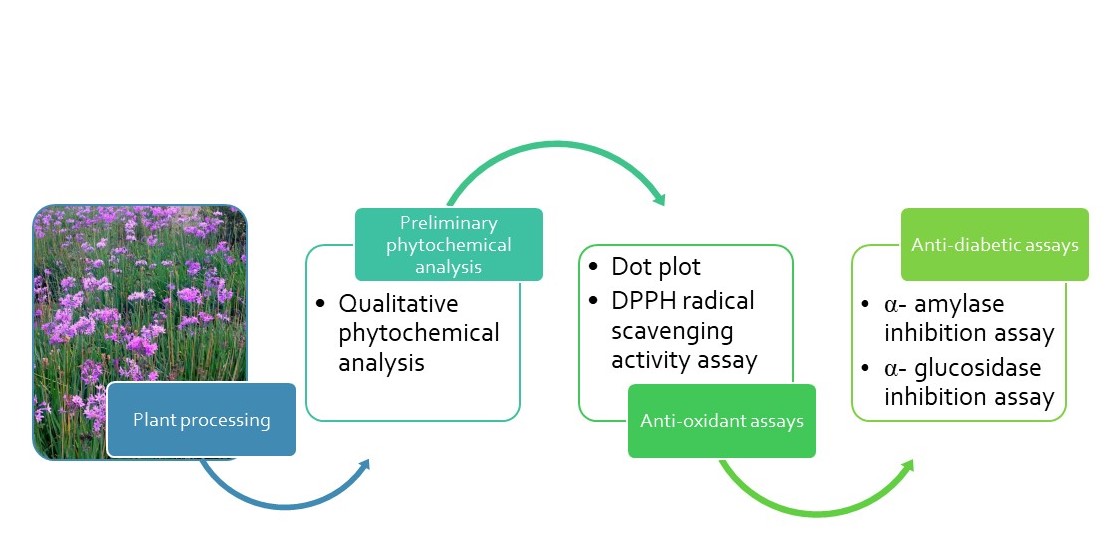

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.1.1. Sample Collection, Preparation and Handling

2.1.2. Extraction of the Plant Material

2.2. Qualitative Phytochemical Analysis

2.3. Antioxidant Assay

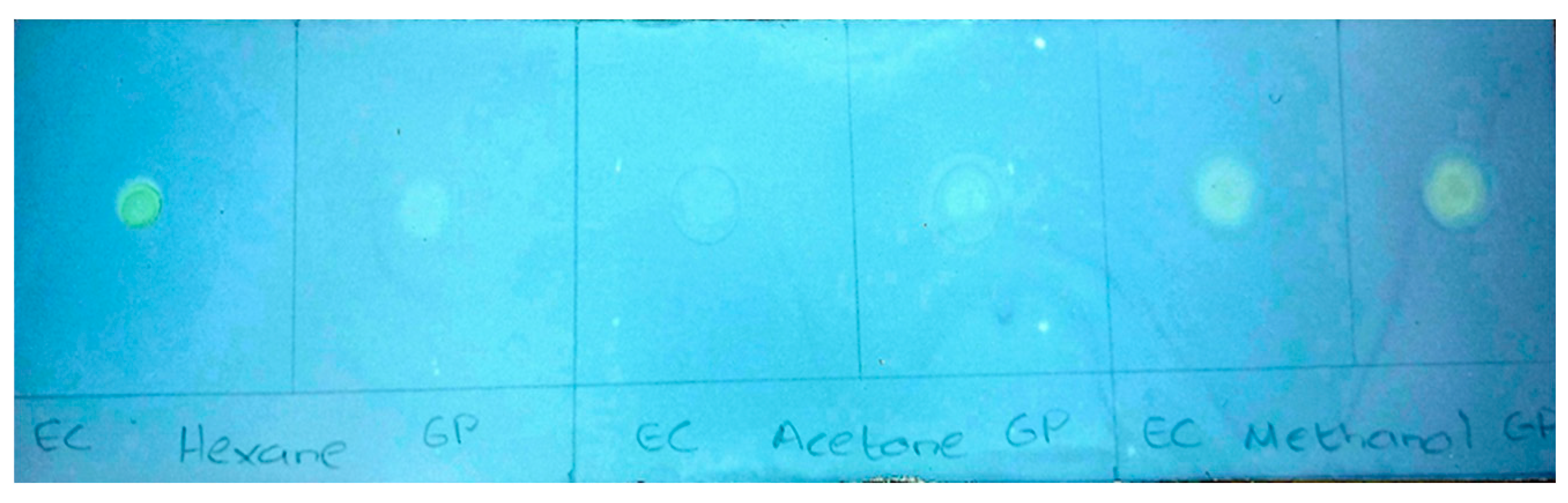

2.3.1. Qualitative Antioxidant Activity (Dot-Plot Assay)

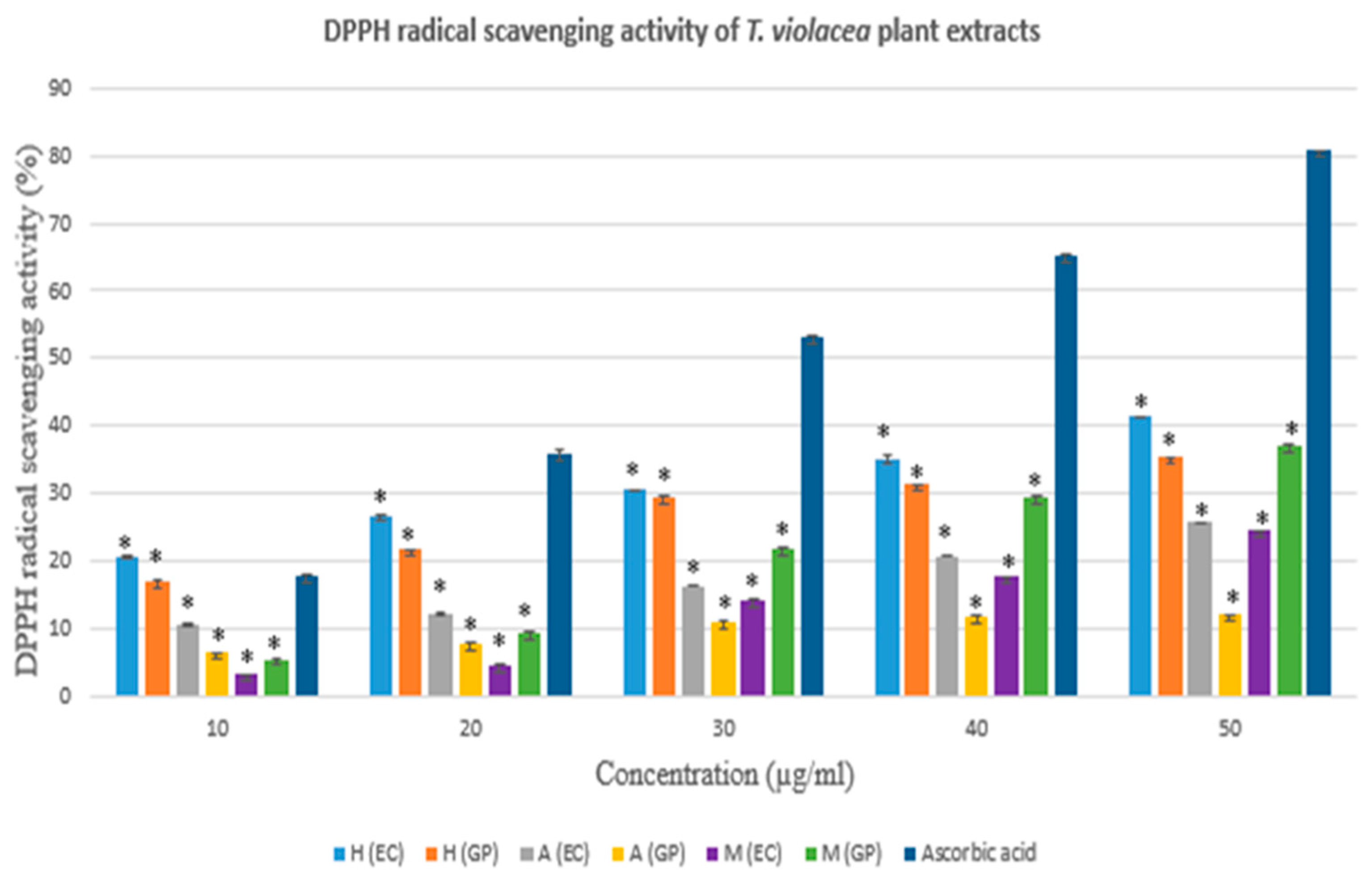

2.3.2. Quantitative DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

2.4. Antidiabetic Assays

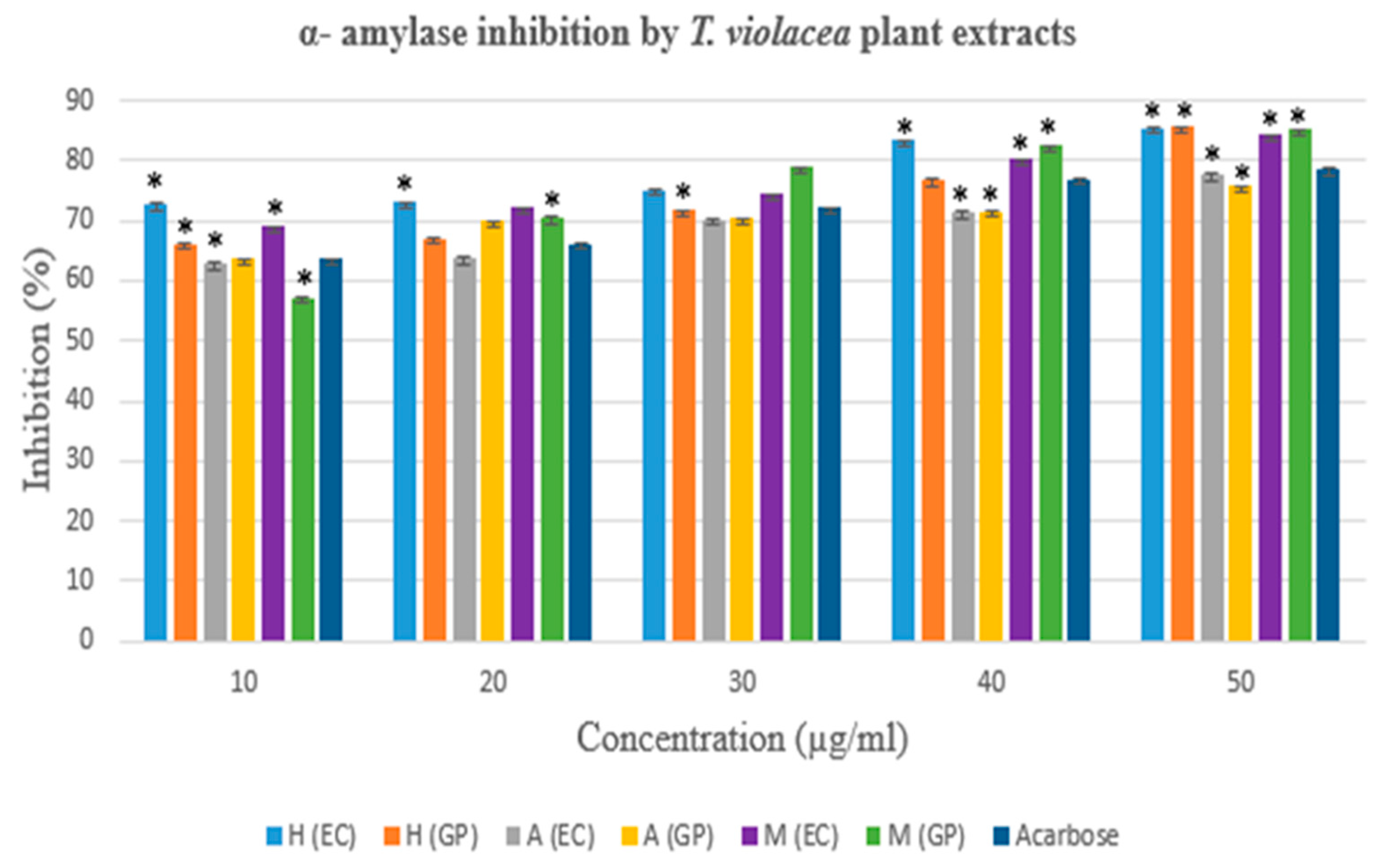

2.4.1. The α- amylase Inhibition Assay

2.4.2. The α-glucosidase Inhibition Assay

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Phytochemical Analysis

3.2. Antioxidant assay

3.2.1. Qualitative Antioxidant Screening: Dot-Plot Method

3.2.2. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

3.3. Antidiabetic Assays

3.3.1. The α- amylase Inhibition Assay

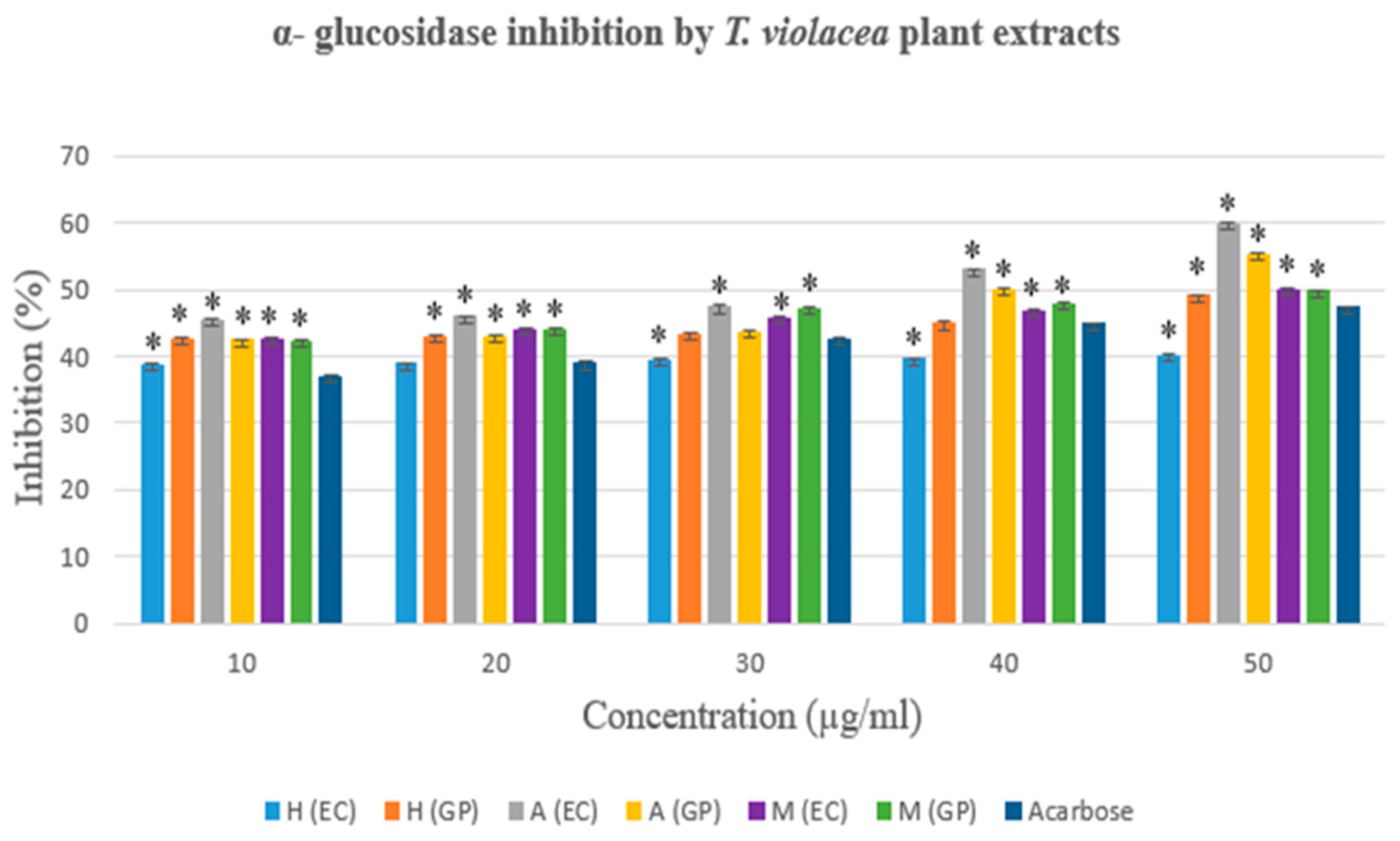

3.3.2. The α- glucosidase Inhibition Assay

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| DPPH DPP-IV |

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 |

| EC | Eastern Cape Province |

| GP SA T1DM T2DM TLC |

Gauteng Province South Africa Type 1 diabetes mellitus Type 2 diabetes mellitus Thin layer chromatography |

References

- World Health Organisation. Traditional Medicine. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/traditional-medicine (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Che, C.; George, V.; Ijinu, T.; Pushpangadan, P.; Marobela, K. Traditional Medicine. In Pharmacognosy: Fundamentals, Applications and Strategies, Badal, S.; Delgoda, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Academic Press, 2017, pp. 15-30. [CrossRef]

- Mothibe, M.E.; Sibanda, M. African Traditional Medicine: South African Perspective. In Traditional and Complementary Medicine, Mordeniz, C. IntechOpen, 2019, pp. 31-57. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Traditional Medicine. Draft traditional medicine strategy: 2025–2034. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB156/B156_16-en.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Shetty, P.; Rinaldi, A. Traditional medicine for modern times: Facts and figures. Available online: https://www.scidev.net/global/features/traditional-medicine-modern-times-facts-figures/ (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Thomford, N.E.; Senthebane, D. A.; Rowe, A.; Munro, D.; Seele, P.; Maroyi, A.; Dzobo, K. Natural Products for Drug Discovery in the 21st Century: Innovations for Novel Drug Discovery. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 6, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- South African National Biodiversity Institute. Tulbaghia violacea. Available online: https://pza.sanbi.org/tulbaghia-violacea (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Styger, G.; Aboyade, O.M.; Gibson, D.; Hughes, G. Tulbaghia--A Southern African Phytomedicine. J Altern Complement Med 2016, 22, 4, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeyemi, S.; Bradley, G. Medicinal Plants Used for the Traditional Management of Diabetes in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: Pharmacology and Toxicology. Molecules 2018, 23, 11, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagbo, I.J.; Hussein, A.A. Antidiabetic Medicinal Plants Used in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa: An Updated Review. Processes 2022, 10, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danquah, C.A.; Minkah, P.A.B.; Agana, T.A.; Moyo, P.; Ofori, M.; Doe, P.; Rali, S.; Osei Duah Junior, I.; Amankwah, K.B.; Somuah, S.O.; et al. The Phytochemistry and Pharmacology of Tulbaghia, Allium, Crinum and Cyrtanthus: ‘Talented’ Taxa from the Amaryllidaceae. Molecules 2022, 27, 4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhuvele, R.; Gbashi, S.; Njobeh, P.B. GC-HRTOF-MS Metabolite Profiling and Antioxidant Activity of Methanolic Extracts of Tulbaghia violacea Harv. J King Saud Univ Sci 2022, 34, 7, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1018364722004591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhoahle, P.; Rampana, D.E. Antioxidant Activities, Total Polyphenol Profile and Anticancer Activity, of Leaf, Bulb and Root Extracts of Tulbaghia violacea from Bloemfontein. Phcog J 2023, 15, 5, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. South Africa, Key Information. Available online: https://idf.org/our-network/regions-and-members/africa/members/south-africa/ (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- World Health Organisation. Diabetes. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is Diabetes? Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/diabetes.html#:~:text=Diabetes%20is%20a%20chronic%20(long,your%20pancreas%20to%20release%20insulin (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes care 2009, 32, Suppl 1, S62–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galicia-Garcia, U.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Jebari, S.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Siddiqi, H.; Uribe, K.B.; Ostolaza, H.; Martín, C. Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 17, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutsaert, E.F.; Medications for Diabetes Mellitus Treatment - Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. MSD Manual Professional Edition. Available online: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/endocrine-and-metabolic-disorders/diabetes-mellitus-and-disorders-of-carbohydrate-metabolism/medications-for-diabetes-mellitus-treatment (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Dias, D.A.; Urban, S.; Roessner, U. A Historical Overview of Natural Products in Drug Discovery. Metabolites 2012, 2, 2, 303–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madike, L.; Takaidza, S.; Pillay, M. Preliminary Phytochemical Screening of Crude Extracts from the Leaves, Stems, and Roots of Tulbaghia violacea. Int J Pharmacogn Phytochem Res 2017, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Mathew, L. Comparative Account of the Preliminary Phytochemical Aspects of Helicanthes elastica (Desr) Danser growing on two Different Hosts. J Pharmacogn Phytochem 2014, 3, 1, 218–221, https://www.phytojournal.com/archives/2014/vol3issue1/PartD/47.1-184.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Adak, S.; Rajak, R.C. , Banerjee, R. In Vitro Efficacy of Bryophyllum pinnatum Leaf Extracts as Potent Therapeutics. Prep Biochem Biotechnol 2016, 46, 5, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ.; Alwasel, S.H. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay. Processes 2023, 11, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.H.; Wang, Z.; Hwang, S.H; Kang, Y.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Lim, S.S. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Antioxidant Capacity of Perilla frutescens Leaves Extract and Isolation of Free Radical Scavengers using Step-wise HSCCC Guided by DPPH-HPLC. Int J Food Prop 2017, 20, sup1, 921–34.

- Worthington, K.; Worthington, V. Amylase, Alpha- Assay, Worthington Enzyme Manual 2011. Available online: https://www.worthington-biochem.com/products/amylase-alpha/assay (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Worthington, K.; Worthington, V. Maltase, Worthington Enzyme Manual 2011. Available online: https://www.worthington-biochem.com/products/maltase/manual (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Takaidza, S.; Pillay, M.; Mtunzi, F. Analysis of the Phytochemical Contents and Antioxidant Activities of Crude Extracts from Tulbaghia species. J Tradit Chin Med 2018, 38, 2, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olorunnisola, O.; Bradley, G.; Afolayan, A. Chemical composition, antioxidant activity and toxicity evaluation of essential oil of Tulbaghia violacea Harv. J Med Plant Res 2012, 6(14). https://academicjournals.org/journal/JMPR/article-full-text-pdf/B46B01A27275.

- Takaidza, S.; Kumar, A.M.; Ssemakalu, C.C.; Natesh, N.S.; Karanam, G.; Pillay, M. Anticancer Activity of Crude Acetone and Water Extracts of Tulbaghia violacea on Human Oral Cancer Cells. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2018, 8, 9, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makgati, M.M.B. The Antifungal Activity and Bioanalysis of Fractions from Tulbaghia violacea (leaf and root) Acetone Extracts. Masters Dissertation. Vaal University of Technology, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa, 2022. https://digiresearch.vut.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/3adf99d5-40d0-4e0e-8ae3-b174edfc2b42/content.

- Ben Jalloul, A.; Chaar, H.; Tounsi, M.S.; Abderrabba, M. Variations in Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Activities of Scabiosa maritima (Scabiosa atropurpurea sub. maritima L.) Crude Extracts and Fractions According to Growth Stage and Plant Part. S Afr J Bot 2022, 146, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shai, K.; Hassan, Z.B.; Lebelo, S.; Ng’ambi, J.W.; Mabelebele, M.; Sebola, N.A. Chemical Analysis and Biological Activities of Various Parts of Securidaca longipedunculata from South Africa. Nat Prod Commun 2024, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, C. W. Carbohydrate Digestion and Absorption. NASPGHAN Physiology Series. Available online: https://www.naspghan.org/files/documents/pdfs/training/curriculum-resources/physiology-series/Carbohydrate_digestion_NASPGHAN.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Callahan, A.; Leonard, H.; Powell, T. Digestion and Absorption of Carbohydrates. Available online: https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Nutrition/Book%3A_Nutrition_Science_and_Everyday_Application_(Callahan_Leonard_and_Powell)/04%3A_Carbohydrates/4.04%3A_Digestion_and_Absorption_of_Carbohydrates (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- Moodley, K.; Mackraj, I. Metabolic effects of Tulbaghia violacea Harv. in a Diabetic Model. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 2016, 13, 4, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, K.; Joseph, K.; Naidoo, Y.; Islam, S.; Mackraj, I. Antioxidant, Antidiabetic and Hypolipidemic Effects of Tulbaghia violacea Harv. (Wild garlic) Rhizome Methanolic Extract in a Diabetic Rat Model. BMC Complement Altern Med 2015, 15, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, M.R. Phytochemical Analysis and In Vitro Anti-diabetic Activity of Selected South African Medicinal Plants Traditionally Used to Treat Diabetes Mellitus. Masters thesis. Nort West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2023. https://repository.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/42055/Stevens_MR.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Motadi, L.R; Choene, M.S.; Mthembu, N.N. Anticancer Properties of Tulbaghia violacea Regulate the Expression of p53-Dependent Mechanisms in Cancer Cell Lines. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 1, 12924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeka Aba, P.; Asuzu, I.U. Mechanisms of Actions of Some Bioactive Anti-diabetic Principles from Phytochemicals of Medicinal Plants: A Review. Indian J Nat Prod Resour 2018, 9, 2, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phytochemical | T. violacea extracts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexane | Acetone | Methanol | ||||

| EC | GP | EC | GP | EC | GP | |

| Saponins | ++ | ++ | + | +/- | ++ | ++ |

| Anthraquinones | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Flavonoids | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| Tannins | - | - | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| Alkaloids | + | + | ++ | + | + | +/- |

| Steroids | +++ | + | ++ | + | + | - |

| Cardiac glycosides | ++ | +++ | + | ++ | - | - |

| Phenols | +/- | +/- | + | + | +++ | ++ |

| Concentration (µg/ml) | DPPH radical scavenging activity (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexane Extract | Acetone Extract | Methanol Extract | ||||

| EC | GP | EC | GP | EC | GP | |

| 10 | 20,505* | 17,021* | 10,686* | 6,410* | 3,209* | 5,535* |

| 20 | 26,465* | 21,664* | 12,227* | 7,785* | 4,701* | 9,519* |

| 30 | 30,516* | 29,613* | 16,337* | 11,094* | 14,220* | 21,855* |

| 40 | 35,098* | 31,372* | 20,689* | 11,611* | 17,610* | 29,502* |

| 50 | 41,314* | 35,362* | 25,762* | 12,069* | 24,443* | 37,202* |

| Extracts and standard | IC50 value (µg/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| T. violacea (EC) | T. violacea (GP) | Ascorbic acid | |

| Hexane | 68.259 | 79.565 | |

| Acetone | 115.11 | 295.568 | |

| Methanol | 97.105 | 65.138 | |

| Ascorbic acid | 29.595 | ||

| Concentration (µg/ml) | α- amylase inhibition activity (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexane Extract | Acetone Extract | Methanol Extract | |||||

| EC | GP | EC | GP | EC | GP | ||

| 10 | 72,778* | 66,167* | 62,891* | 63,754* | 69,094* | 57,228* | |

| 20 | 73,056* | 67,056* | 63,862* | 69,903* | 72,168* | 70,550* | |

| 30 | 75,111* | 71,833* | 70,168 | 70,496 | 74,434* | 78,846* | |

| 40 | 83,389* | 76,889* | 71,467 | 71,597 | 80,334* | 82,567* | |

| 50 | 85,500 | 85,667 | 77,724* | 75,750* | 84,218* | 85,194* | |

| Extracts and standard | IC50 value (µg/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| T. violacea (EC) | T. violacea (GP) | Acarbose | |

| Hexane | 9,022 | 15,083 | |

| Acetone | 16,189 | 16,504 | |

| Methanol | 16,146 | 16,201 | |

| Acarbose | 16,366 | ||

| Concentration (µg/ml) | α- glucosidase inhibition activity (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexane Extract | Acetone Extract | Methanol Extract | ||||

| EC | GP | EC | GP | EC | GP | |

| 10 | 38,849* | 42,606* | 45,414* | 42,444* | 42,727* | 42,263* |

| 20 | 39,000 | 43,000* | 46,000* | 43,000* | 44,000* | 44,000* |

| 30 | 39,521 | 43,475 | 47,475* | 43,758 | 45,960* | 47,333* |

| 40 | 39,721* | 45,000 | 53,000* | 50,000* | 47,000* | 48,000* |

| 50 | 40,101* | 49,172* | 60,010* | 55,273* | 49,960* | 49,838* |

| Extracts and standard | IC50 value (µg/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| T. violacea (EC) | T. violacea (GP) | Acarbose | |

| Hexane | 42,2 | 43,332 | |

| Acetone | 34,570 | 38,878 | |

| Methanol | 41,607 | 41,148 | |

| Acarbose | 45,609 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).