Submitted:

30 September 2025

Posted:

30 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- Fundamental Structure: Space emerges from a dynamic network of Planck-scale Space Elementary Quanta (SEQ) – indivisible units whose elastic interactions and excitation states encode all physical phenomena.

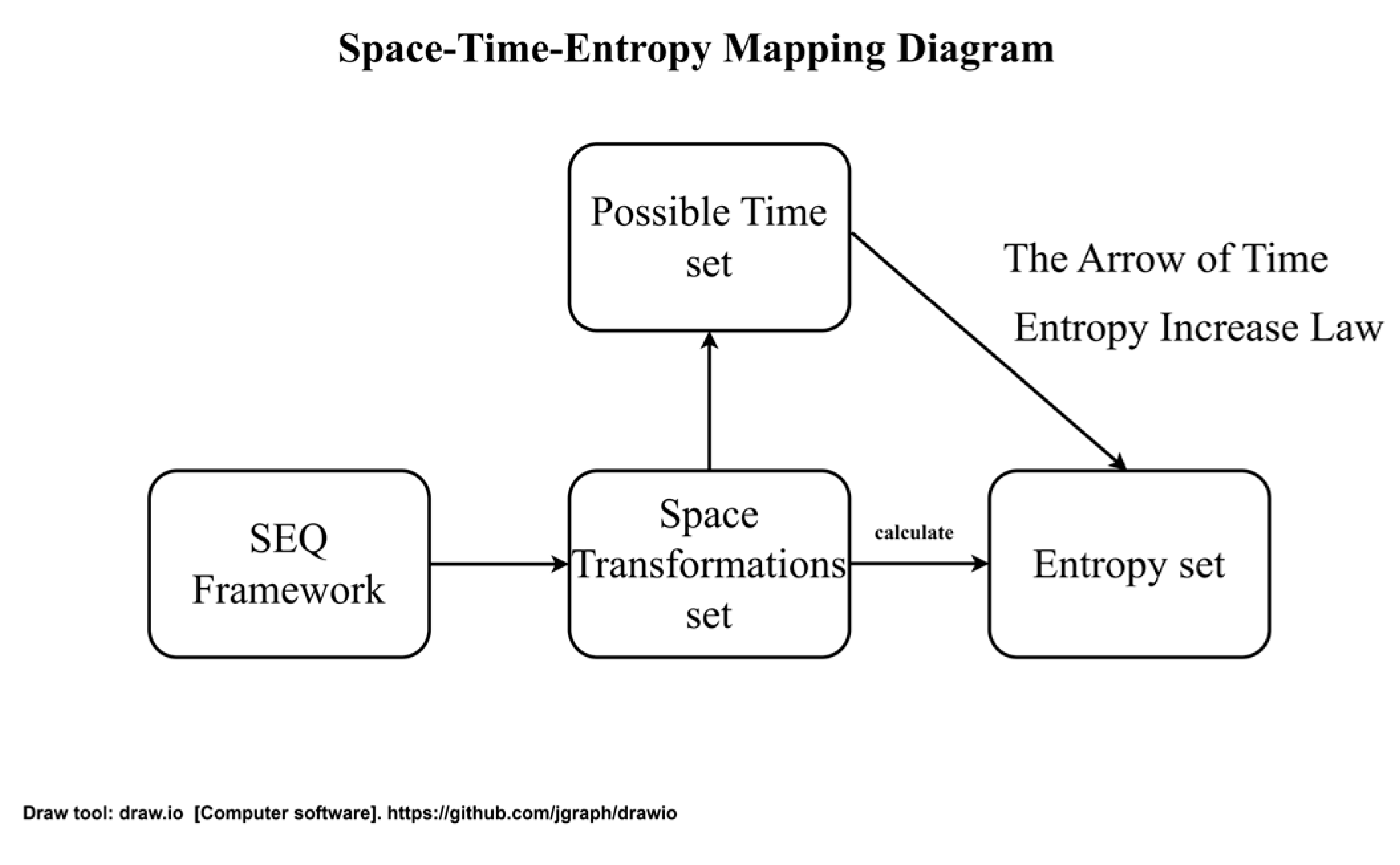

- Time and Entropy: Global time arises from discrete, entropy-increasing transformations of the SEQ network, with local time dilation governed by modulation of SEQ state-transition frequencies .

- Mass-Gravity Unification:

1. Preparatory assumptions:

1.1. The universe is expanding.

1.2. The universe operates under the Law of Energy Conservation and the Law of Entropy Increase.

1.3. The universe consists of SEQ, discrete Planck-scale units, forming a topologically homeomorphic 3D structure (adjacency relations remain preserved while individual SEQ energy states may vary). Importantly, this polycrystalline structure necessarily contains primordial Periodic or Random Topological Dislocation to ensure physical isotropy, yet maintains strict 3D topological homeomorphism as these defects are cosmologically frozen and adjacency-preserving since the birth of the universe. The distortion of light around black holes demonstrates that gravitational and electromagnetic field quanta are coupled, suggesting they originate from the same quantum field in different excited states—leading to the SEQ hypothesis. The spacing and tension between adjacent SEQ can be modulated by gravitational or equivalent gravitational fields.

1.4. All field quanta and elementary particles represent different energy excitation states of SEQ, expressible as 3D dynamic structural matrices of SEQ .

1.5. SEQ possess a ground state energy (e.g., ground-state spin or vibrational modes). If ground-state spin chirality is fixed, this may explain parity violation. The ground-state energy of SEQ could also account for the cosmological constant in General Relativity. This framework shows strong alignment with Loop Quantum Gravity theory.

1.6. Adjacent SEQ maintain a dynamic equilibrium spacing interconnected via spring-like bonds in their ground state. SEQ are fundamental, indivisible Planck-scale entities—their structure remains intact under any deformation or energy fluctuations.

- The spin degrees of freedom of SEQ and their elastic bonds remain decoupled, preserving independent dynamical regimes.

- Under perturbation, the system responds by modifying SEQ resonant frequencies while generating compressive/tensile forces.

- This elastic response is nonlinear and asymmetric.

- SEQ are stable, indivisible structures composed of sub-Planckian components. SEQ’ spin emerges from collective space transformations at the sub-Planck level. This ensures the spin degrees of freedom do not interfere with elastic deformations in the SEQ network. This architecture naturally protects spin dynamics from elastic disturbances.

- At the sub-Planckian scale, the elastic properties of the underlying substrate impose an upper bound on the spacing modulation and tension between adjacent SEQ. This fundamental limit ensures that extreme deformations (e.g., near black hole singularities) cannot disrupt the topological integrity of the SEQ network.

- In this model, the harmonic oscillation intervals of SEQ are integer multiples of Planck time(tₚ). Consequently, all dynamic processes—including elastic strain interactions, harmonic conduction, as well as scalar, spinor field transmissions and other energy conduction mode induced by rotational axis dynamics—are fundamentally constrained by the discrete Planck-time intervals. This property inherently ensures the model’s consistency with the discrete-time hypothesis in quantum mechanics and quantum gravity theories.

- Any discrete model of spacetime must confront the challenge of restoring spatial isotropy so as to remain compatible with the Lorentz-covariant rules established by observation. Beyond the isotropy mechanism tied to the topologically dislocated configuration discussed in §1.3, an alternative is to let the SEQ lattice spacing be sufficiently large for sub-Planckian elastic constituents—whose characteristic scale is far below the Planck length—to fill the network uniformly. Provided that, within the precision accessible to cosmological observations, the statistical distribution of these constituents yields a dispersion relation that is effectively Lorentz-covariant, macroscopic isotropy emerges naturally and remains consistent with all current observational data.

1.7. If matter truly traversed space, it would require modification of spacetime’s adjacency relations. Yet black holes—despite their extreme mass—preserve local spacetime topology (as evidenced by smooth light bending). This implies that apparent particle motion must instead represent propagating excitations of spacetime itself, consistent with GR. The speed of light (c) constitutes the maximum excitation propagation rate in space.

1.8. Algebra derivation:Matter-Spacetime Unity| Matter is a part of space

1.9. Quantum-Elastic Two-Layer Fiber Bundle Model | Common Base Space Platform for General Relativity and Quantum Field Theory

1.10. Derivation of the Spatial Topological Invariance Postulate in This Model

2. Time as a counting process of spacetime network transformations:

2.1. SEQ serve as the electromagnetic wave conducting medium. Matter with mass and its motion are waves in this medium. In this framework, nothing truly moves through space - light speed c is the maximum conduction speed c, preventing velocity stacking beyond c. All physical phenomena correspond to specific energy state configurations, establishing SEQ as the universal substrate.

2.2. The universe’s composition: Energy conservation and quantization imply a finite number N of SEQ, each with M possible energy states,(where each energy state is an integer multiple of Planck’s constant h, ) allowing up to transformations. These M energy states form an algebraic system incorporating translational, spinning and rotational operations connecting to standard model. Energy conservation and entropy increase constraints reduce possible transformations significantly below .

2.3. Time definition:

2.3.1. Let J be the possible universe transformations (J <<).

2.3.2. The Planck time (tₚ) interval separates adjacent transformations as the minimal time unit.

2.3.3. Time’s arrow follows entropy increase.

2.3.5. Each space transformation (state transition of the SEQ network) can be assigned a unique entropy value calculated via the multiplicative energy distribution across this space transformation’s matrix.

2.3.6. Finite transformations ensure discrete, limited time in this model.

3. Definition and analysis formula of entropy In this definition of entropy, the entropy value of a closed system at a given moment (i.e., during a specific state transition) is calculated as the multiplicative product of the energy norms of all SEQ involved in that transition(that moment’s space transformation).

3.1. Energy transfer rules and triggering conditions:

3.2. Numerical Example: System States and Entropy Evolution

| System State | SEQ Energy Distribution =12 |

Entropy |

Remarks |

| Initial non-equilibrium state | [3, 1, 5, 3] | 45 | - |

| Intermediate state | PathA:[3, 1, 4, 4]; PathB:[3, 2, 4, 3]; |

PathA:48; PathB:72; |

- |

| Final state | PathA:[3, 2, 3, 4]; PathB:[3, 3, 3, 3]; |

PathA:72; PathB:81; |

Due to adjacent energy transfer with minimal quanta h, this system cannot reach maximum entropy in case A |

3.3. Logarithmic Relation:

3.4. Proof of Spontaneous Entropy Increase

3.5. The definition conserves energy, has an entropy ceiling, ensures spontaneous increase, and logarithmically aligns with classical entropy.

3.6. The Spontaneous Entropy Increase is Causality.

3.7. Why Analytic multiplicative Entropy is Adopted: Within this model’s framework, physical states at Planck-time scales exhibit deterministic characteristics. Although current experimental conditions cannot directly measure them, traditional statistical entropy can be reduced to analytic expressions at this scale. This perspective not only reveals the microscopic essence of statistical quantities but also provides a new analytic foundation for quantum thermodynamics—unifying macroscopic statistical behaviors with deterministic dynamics at the Planck scale.

| Comparison Dimension | Multiplicative Entropy | Traditional Statistical Entropy |

| Process Explicitness | Explicitly records energy homogenization steps via product sequences (e.g., ∏ᵢ mᵢ), preserving microstate transition details | Describes only macro-state differences via logarithmic state-count (ln Ω), erasing intermediate dynamics |

| Physical Intuitiveness | Entropy increase directly reflects irreversible energy redistribution; time asymmetry emerges from dynamics | Relies on probabilistic assumptions (e.g., molecular disorder) and requires ad hoc low-entropy past boundary |

| Process Resolution | Tracks Planck-timescale (tₚ) energy transfers; | Limited to ensemble averages, incapable of resolving quantum fluctuations or short-timescale entropy production |

3.8. Analysis of the Maximum Entropy Principle

3.9. In section 9.1.1, we will continue to discuss the decomposition of energy carried by SEQ {mᵢ=Kresonant (Kspin) +Uelastic assigned to this SEQ from its adjacent elastic bonds manifested as frequency suppression.}, the relational expressions, and the supplementary description of the initial low-entropy state of the universe. Chapter 13 will provide a detailed explanation of the metric-SEQ resonance frequency mirror relationship under this model. With this setting, there is no need to observe the sub-Planckian constituent-level elastic potential energy or the metric tensor; instead, the regional elastic potential energy can be directly represented by the SEQ resonance frequency. Chapter 14 will mention that SEQ spin and resonance frequency mutually excite each other and change synchronously; therefore, SEQ spin kinetic energy can also be represented by SEQ resonant kinetic energy.

4. Analysis of Action

- The absence of an explicit potential energy term in the analytical herein expression is compensated by the concept that any form of metric change in space results in a reduction of SEQ resonance frequency. This implies that the potential energy term is inherently embedded within the formulation via resonance frequency modulation.

- The essence of the potential energy terms in both the Hamiltonian and Lagrangian formulations, under this model, can be understood as modulations in the frequency of energy transmission events.

- Gravitational potential energy, electromagnetic potential energy, weak interaction potential energy, and strong interaction potential energy are all fundamentally manifestations of the elastic potential energy resulting from distortions in the spatial tensors or twists.

- The essence of potential energy release is the reduction of spatial distortion, which is accompanied by an increase in SEQ resonance frequency.

5. Local time , the proper time and relative time in Relativity

5.1. local time. As previously established, global time is defined by the transformations of the universe. This work introduces local time as an operational concept that: (1) provides correspondence with special relativistic time notions; and (2) enables precise specification of time scales for localized physical processes. Crucially, any measurable time parameter in physical calculations necessarily corresponds to transformations within a specific local space. This operational concept is designated as local time.

5.2. The proper time in General Relativity is related to local transformations count of physics process entities. (Section 9.1,Section9.5.6 present the physical mechanism underlying proper time dilation in GR.)

5.3. Understanding on Lorentz-covariant rules in Special Relativity theory: The time perception of physical processes across distinct reference frames fundamentally corresponds to the observation of transformation counts. The observation time discrepancy between frames derives from the accumulated difference in their frame SEQ transformation counts. An observer measures another frame’s time evolution through the differential transformation count ΔN, while he can’t perceive their own transformation count N0. The observed ΔN is fundamentally governed by the dynamic light-path difference between the observer’s frame and the moving reference frame of the measured object. Under the principle of non-additivity of light speed (c-invariance), this formulation naturally derives Lorentz-covariant rules through counting operations.

- Key Distinction from GR Effects

- SR Effects as Perceptual Phenomena

- Contrast with GR Mechanisms

5.4. Physical Meaning of Planck Time

6. Basic physical quantities in this framework

7. Phenomenological consistency checks

7.1. Why can’t the speed of light stack up?

7.2. Uncertainty Relation and Wave-particle Duality.

7.3. Double-slit experiment.

7.4. Non-conservation of parity

7.5. Conjecture on Muon Decay experiment [3]

8. Experiment to verify or falsify the hypotheses proposed

9. Gravitational Interaction, General Relativity and Cosmic Evolution Model

9.1. Gravitational interaction is modeled as a translational action described by matrices that alter the equilibrium spacing between SEQ. SEQ are interconnected via spring-like bonds in their ground state(Refer to the basic setting in Section 1.6, page2). Gravity modifies this spacing, creating tension with finite potential energy. This system behaves like a loaded spring: under gravitational fields, oscillation frequencies decrease, reducing local spacetime transformation rates and causing time dilation - matching general relativity’s predictions while revealing its mechanism. Mass-generated gravity acts as a spherically divergent translation with inverse-square density, curving flat spacetime topologically to produce general relativistic metric changes.

9.1.1. Under this model, a detailed deduction of the process of cosmic expansion.

| Stage-Phase | Stage Name | Process | Universe State | Thermodynamic Characteristics |

| 0-Compression | Pre-Big Bang Initial State | The universe’s SEQ network is highly compressed, with resonant frequencies close to zero. The initial low-entropy state may be reflected in a part of local SEQ network having particularly high energy, while most have low energy. | High-energy Aggregation State | Low entropy |

| 1-Compression | Compression Potential Energy → Kinetic Energy | Elastic compression potential energy is released and converted into cosmic expansion kinetic energy | Accelerating Expansion | Low entropy, high energy concentration, rapid entropy increase |

| 2-Stretching | Kinetic Energy → Tension Potential Energy | Expansion kinetic energy is converted into tension potential energy | Decelerating Expansion | Increasing entropy |

| 3-Stretching | Tension Potential Energy → Kinetic Energy | Tension potential energy is released and converted into contraction kinetic energy | Accelerating Contraction | Entropy continues to increase |

| 4-compression | Kinetic Energy → Compression Potential Energy | Contraction kinetic energy is converted into compression potential energy | Decelerating Contraction | Entropy continues to increase |

| repeated Oscillation → Equilibrium Oscillation |

Energy Homogenization → Equilibrium Oscillation | In each cycle, the energy distribution becomes more uniform, with no obvious concentrated states remaining | Approaching Equilibrium State | Entropy approaches maximum, oscillating universe in thermal equilibrium |

| This process does not collapse back to the initial birth configuration of universe, nor does it reduce entropy—since the entropy increasing trend remains invariant under expansion or contraction, the homogenization of energy distribution is an irreversible process, until entropy reaches its maximum value. | ||||

- E global SEQ network =Kresonant (K spin) +Uelastic;

- Uelastic=U compress-stretch +U twistor(Space network spinor);

- Utwistor(Space network spinor) converts into Kresonant(Kspin) ; embodied as space network spinor

- Ucompress-stretch converts into Kresonant (Kspin)

| 1 | Potential energy is stored in elastic bonds composed of sub-Planck scale components. |

| 2 | In this model the energy of SEQ mᵢ equals the SEQ resonant kinetic energy plus the elastic potential energy assigned to this SEQ from its adjacent elastic bonds manifested as frequency suppression. Chapter 14 will mention that SEQ spin and resonance frequency mutually excite each other and change synchronously; therefore, SEQ spin kinetic energy can also be represented by SEQ resonant kinetic energy. |

| 3 | Chapter 10 will discuss that mass formation is mainly due to spin locking the spatial compression state and the key factor is the coupling confinement potential between the network spinor and the SEQ fixed chirality spin. |

9.1.2. The mass formation and matter-energy conversion mechanisms in different stages of cosmic evolution:

- First stage of cosmic expansion: mass generation dominates.

- Second and third stages of cosmic evolution:

- Fourth stage of cosmic evolution : the universe re-enters a compressed phase.

- Fifth stage of cosmic evolution:

9.2. Consistent with general relativity, high-velocity or accelerated transformations of localized matter compress space, thereby inducing tensile stretching of surrounding space (equivalent gravitational effects). This process not only induces spacetime curvature but also modulates the conduction frequency of waves.

9.3. Detailed Correspondence with Newton’s law of universal gravitation

9.4. Correspondence with Newton’s First Law—the Law of Inertia

9.5. Understanding on General Relativity

9.5.1. Under gravitational and equivalent gravitational interactions, the dynamic deformation of 3D space structural matrix and variation in local SEQ density distribution corresponds to Metric field in General Relativity.

9.5.2. Minimum cumulative conduction count path adjustment along with the cumulative dynamic paths connecting every two-points with the minimal count of adjacent SEQ through spacetime distortion corresponds to geodesic path in general relativity. (Principle of least action)

9.5.3. Global topological homeomorphic transformation in SEQ framework corresponds to Diffeomorphism invariance in General Relativity.

9.5.4. The continuity assumption in general relativity, analogous to the continuum medium framework in fluid mechanics, constitutes a necessary and effective computational framework.

9.5.5. Black hole event horizon:

9.5.6. Gravitational and Kinematic Time Dilation

10. Mass, Gravity, SU(3) and Higgs field in Quantum Field Theory

10.1. SU(3) as the Origin of Mass Derivation

10.1.1. General Relativity establishes that gravitational fields manifest as metric perturbations→spacetime curvature.

10.1.2 Mass must therefore induce localized spacetime distortion→creating the observed gravitational potential.

10.1.3 This implies mass itself represents a condensed form of spacetime deformation →self-consistent with stress-energy sourcing curvature.

10.1.4 Within hadrons, quark-gluon dynamics are governed by SU(3) color interactions→the dominant force compressing SEQ network.

10.1.5. Thus, SU(3)-mediated compression of SEQ network → generates both quark confinement energy (mass) and external spacetime stretching (gravity).

10.1.6 Generalizing this mechanism→ equivalent effects (velocity/acceleration) anisotropically compress local space→inducing equivalent gravitational attraction via adjacent SEQ tension.

10.2. U(1): Electromagnetic Interaction

10.3. SU(2): Adjustments of Rotational Axes, spin and encoding chirality in Charged Microscopic Particle Structural Matrices.Encoding Rotational chirality of Charged Microscopic Particle Structural Matrices as the Origin of Weak Interaction Symmetry Breaking. because the rotational Structural Matrices with different chirality have different coupling mode with the fixed chirality of SEQ’s ground-state spin. Although SU(2) lacks a chirality modulation parameter, its definition as adjusting rotation axes and spin for charged particles with specific chirality intrinsically encodes chiral variables.

10.4. SU(3):

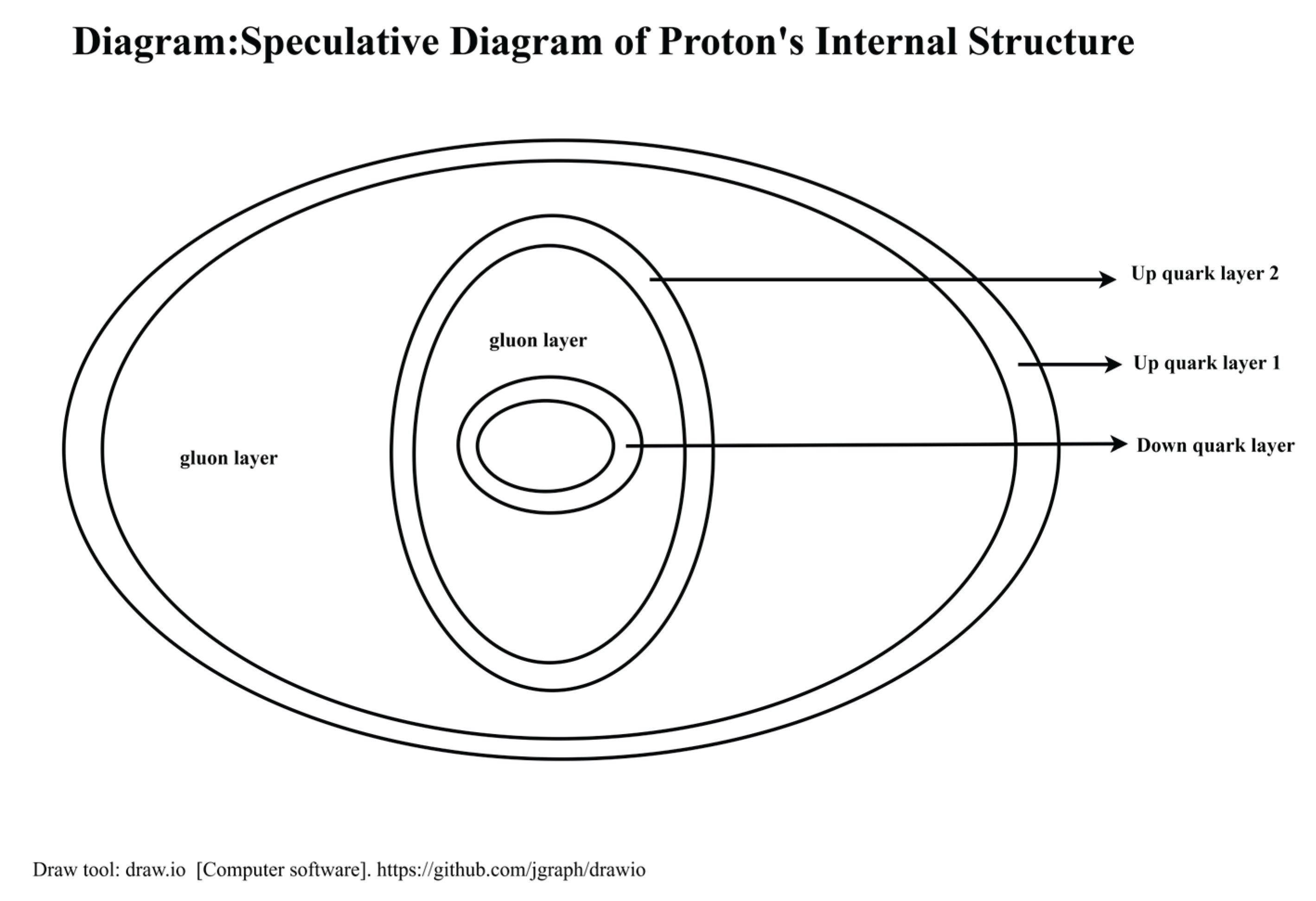

10.4.1. Imagine the 3D dynamic quasi-spherical matrix structure of quarks as a multi-layered and multi-axial rotational configuration. Due to the high-energy concentration within the structure, the SEQ within the structure remain in a dynamic equilibrium of compression or stretching, while the interactions between layers also maintain a dynamic equilibrium of compression or stretching.

10.4.2. Fractional quark charges emerge from stratified SEQ layers in proton/neutron matrices, with 2/3-charged quarks occupying twice the layers of 1/3-charged quarks. The multi-layered structure well explains the observed differences between high-energy(uniform angular distribution) and medium-energy regimes in electron-proton scattering experiments.

10.4.3. The color property of quarks corresponds to the long axis of their dynamic structural matrix, specifically the axis with the highest energy density distribution within the quark’s structural configuration. The color neutrality of protons and neutrons corresponds to the global spatial symmetry, the isotropy of the electric field (protons)and structural stability exhibited by their spatial structural matrices.

10.4.4. Antiquarks correspond to the handedness reverse representation of structural matrix rotational transformation of their corresponding quarks.

10.4.5. The 8 generators of SU(3) correspond to 8 distinct interactions mediated by different gluons dynamics manner. Among them, the 6 non-diagonal matrices represent combinations of color exchange operations, stretching and compression phase transformations with phase variations(3*2); while the 2 diagonal matrices correspond to scaling transformations across the three color dimensions. These gluons and their 8 distinct interaction types operate within the interlayer regions of the multi-layered structural matrices of protons or neutrons.

10.4.6. Gluons mediate compression and tensile stresses between quarks or interlayer SEQ. Gluons can be understood as a kind of quasi-structure of highly condensed SEQ, akin to a rotational high-density array of springs.

10.4.7. Quark asymptotic freedom and color confinement originated from nonlinear variations in compression-tensile tensions among SEQ.

10.4.8. The three-quark point-like configuration inherently fails to achieve spatial symmetry, contradicting the observed spherical charge distribution of protons, whereas this hypothesis of a layered arrangement in a quasi-spherical structure of up and down quarks within the proton offers a more plausible explanation for the integer charge of the proton and the isotropic nature of the electric field as well.

10.4.9. The discrepancy in the proton’s g-factor from theoretical models stems from an underestimation of the gluon field’s spinor contribution. If the effect of the rapidly rotating gluon field were properly accounted for, this deviation would significantly diminish. Moreover, the conventional three-point-quark distribution framework fundamentally cannot accommodate a proportionally substantial gluon field spinor component. The layered structure proposed in this model presents a viable architectural framework worthy of serious consideration.

10.5. How SU(3) Generators Mediate Mass Formation

10.6. The essence of mass is the storage of gravitational (spatial elastic) potential energy under the interaction of SU(3) corresponding to the compression of space.

10.6.1. Dimensional analysis dictates that the relationship between mass and energy must satisfy [E]/[m][], with the proportionality coefficient determined by the fundamental constants of spacetime (the speed of light, c).

10.6.2. The compressed potential energy of mass in localized space is inherently mainly released as gravitational waves with radiation, which propagate at speed c , thus directly yielding E=m.

10.7. Complementary Role of the Higgs Field: Symmetry Breaking and “Locking” Mechanism:

10.7.1. The Higgs field plays a crucial yet subtle role in this framework by acting as a stabilizing “quantum chiral lock” that preserves the compression effects mediated by the SU(3) gluon field on the local SEQ network. While the SU(3) color force actively compresses the local space to generate mass-energy through spatial deformation, the Higgs mechanism serves to maintain this compressed configuration in a stable equilibrium state. This locking function is particularly vital for quark confinement, as it prevents the rapid dissipation of the gluon field’s compressive energy that would otherwise lead to deconfinement. The Higgs field’s symmetry-breaking properties thus complement the SU(3) compression mechanism by providing an additional interaction of stability to the mass-generating structure. In essence, if the SU(3) mediated compression is likened to a tensed spring storing potential energy, the Higgs field acts as the catch mechanism that keeps the spring compressed, ensuring the persistence of the mass effect. This dual mechanism - active compression by color forces and passive stabilization by the Higgs field - offers a more complete picture of mass generation that bridges quantum chromodynamics with electroweak theory while remaining consistent with the discrete spacetime framework proposed in the paper. The interplay between these mechanisms may also help explain why certain particles (like quarks) exhibit both confinement and mass properties, while others (like leptons) primarily acquire mass through Higgs interactions alone(like a preloaded torsional spring energy storage combined with a ratchet).

10.7.2. Origin and Physical Picture of the Higgs Mechanism

10.7.3. Therefore, quark confinement may arise from the combined effects of the Higgs field’s quantum chiral lock and the nonlinear response of spatial elasticity(QCD).

10.8. A fundamental duality emerges between the SU(3)-driven compression of matter at quantum scales and the emergent gravitational field: The mass of hadrons arises from intense color-force compaction within subnuclear volumes, whereas gravity manifests as the coherent stretching of the finite SEQ fabric. This stark contrast in interaction ranges—from quark confinement to system-wide SEQ deformation—naturally explains the hierarchical strength difference between nuclear and gravitational forces.

10.9. In nuclear reactions, the release of kinetic energy primarily corresponds to the elastic potential energy-kinetic energy of the QCD dynamic spring array, while the breaking of the Higgs mechanism mainly releases stored Fermionic Spinor energy-akin to torsional spring energy storage in the form of radiation. This explains the energy type distribution in nuclear reactions and the radiative phenomena in QED.

10.10. According to my personal understanding, the tensor description in standard General Relativity (GR) represents the compression and stretching of space in different directions. In fact, the synthesis of such compression-stretching tensors across different directions can generate structures similar to spinors, and the Kerr metric is essentially doing this kind of work.

11. Thoughts on the 3D Spatial Arrangement Matrix of Microscopic Particles

11.1. Spatial Arrangement Matrix Representation of Electrons:

11.2. Representation of Electric Charge:

11.3. Fractional Charges of Quarks:

11.4. Annihilation and Decay of Microscopic Particles:

11.5. Mechanism Analysis of Positron and other types of Antiparticle Scarcity:

11.6. Geometric intuition for the half-integer spin of electrons:

11.7. The Nature and Origin of Lepton Mass:

12. Quantum Gravity, Graviton and Space Elastic Response Frequency

12.1. Gravity fundamentally stems from its mediation by elastic bonds(sub-Planckian constituents) between SEQ rather than direct SEQ interactions.

12.2. When the resonant frequency of SEQ significantly exceeds the elastic response frequency of inter-SEQ bonds, gravitational field mediation does not encode SEQ’s spectral fingerprints.

12.3. The method of gravitational wave frequency detection implies that the detected frequency range should fall within the spatial elastic response frequency range. As our understanding of gravitational wave frequencies expands, so too will our knowledge of the spatial elastic response frequency range.

13. Space Deformation(Geometry) - SEQ Resonant Frequency Modulation Duality:-Connecting GR to QFT

13.1. Frequency Modulation as an Essential Description of Spatial Deformation

- The model suggests that any metric change in space, such as curvature caused by gravitational fields, modulates the resonant frequency of SEQ. Compression and stretching phases influence frequency domain modulation through asymmetric elastic coefficients. This frequency modulation directly encodes the geometric information of spatial deformation, eliminating the need for additional Riemann geometry descriptions.

- The traditional concept of potential energy terms (gravitational, electromagnetic, or quantum field potentials) is reinterpreted as frequency modulation of SEQ resonance. For instance, a decrease in gravitational potential energy corresponds to a frequency domain offset, while the release of potential energy manifests as dynamic modulation restoring the frequency to its high-frequency ground state. This mapping enables a unified frequency-domain representation of the metric field in general relativity and potential energy terms in quantum field theory.

- Entropy Increase Rate: In addition, since the conduction frequency within a local space directly determines the local entropy increase rate of the system, there also exists a dualistic modulation mechanism between space geometry deformation and the rate of entropy increase. This relationship is self-consistent and analytically derivable under the SEQ quantized space model.

13.2. Classification of Spatial Deformations: First, classify spatial deformations into 4 types (specific classifications can be refined based on future research):

- Stretching Phase

- Compression Phase

- Left-handed Twistor

- Right-handed Twistor

13.3. Construction of Discrete Functional Framework:

13.4. Generalized Coordinates in This Model:

13.5. Under the topologically homeomorphic setting, the spatial coordinates of each SEQ serve as its structural label and constitute important topological invariants. These coordinates remain fixed during dynamical evolution (i.e., they do not change over time), and therefore are not subjected to time differentiation. Nevertheless, they play a crucial role in constructing conservation equations, such as defining local gradients and adjacency relations. Hence, they should be regarded as background structural parameters rather than components of generalized coordinates.13.6. Mass, Mass represents a spatial compression state that cannot be characterized by a single SEQ. Instead, it requires a local description in terms of the local spatial compression rate — the degree of deformation, which can be quantitatively expressed as the average frequency shift within that local space. Frequency directly reflects the extent of spatial deformation.

- m: mass

- K: a dimensional conversion constant (can be dimensionless or carry traditional mass dimensions)

- N: number of SEQs contained in the mass-bearing object

- ω̄ : average resonance frequency (relative to Planck frequency shift)

- ωₚ : Planck frequency

- (ωₚ/ω̄): represents the degree of spatial deformation

13.7. Force — next, we discuss F = ma. Acceleration can be understood as the rate of change of spatial deformation gradient between a mass-bearing object and its external environment. This gradient of deformation induces the object to maintain structural synchronization during acceleration, resulting in additional spatial deformation — compression at the front end of acceleration and stretching at the back end. In this framework, m represents the structural response barrier (mass), and F is the deformation action required to induce an additional gradient of spatial deformation in an object of mass m. The essence of F = m a is: in order to cause a change in the spatial deformation gradient (acceleration) of an object that possesses a structural response barrier (mass), a corresponding deformation action (force) must be applied.

13.8. Other conceptual constructions of classical physical quantities — the following are only examples and not strict mathematical formalizations:

13.9. In this model, the spatial field is a topologically homeomorphic structural field, and the motion of matter corresponds to the propagation of excitation waves on this field. Therefore, when constructing conservation equations, they may differ from the traditional conservation equations in analytical mechanics, but they should be able to derive equivalent forms corresponding to the classical ones. Here, I can only propose a rough framework, and the specific rigorous mathematical formalization likely still requires the work of professional physicists to complete.

13.10. Hamiltonian, Schrödinger Equation, and General Relativity Equations from the Perspective of This Model

13.10.1. From the perspective of this model, the Hamiltonian is an energy function defined in terms of the generalized coordinates (resonance frequency and resonance axis vector of Space Elementary Quanta, SEQ) and their corresponding generalized momenta. It fully characterizes the current local spatial configuration of energy distribution and acts as the generator of time evolution, determining the subsequent energy distribution and its evolutionary trend at the next moment. In this framework, the traditional notions of kinetic and potential energy terms are both manifested as different modes of frequency modulation of SEQ. The so-called “potential energy” fundamentally arises from elastic potential energy associated with spatial tensor deformations or twistor structures.

13.10.2. Schrödinger Equation: In this model’s interpretation, the Schrödinger equation describes how the current energy distribution, along with its gradients—such as phase gradients (encoded in the Hamiltonian)—determines the probabilistic evolution of the next moment’s energy distribution and its gradients. The origin of probabilistic randomness lies in the non-uniqueness of maximum entropy paths within the system’s dynamical evolution. Thus, quantum probability emerges not from intrinsic indeterminism, but from the multiplicity of valid pathways that satisfy thermodynamic and variational principles under constrained initial conditions.

13.10.3. Einstein’s field equations of General Relativity—the metric tensor equation—and the geodesic equation essentially describe the same class of evolutionary dynamics as the Schrödinger equation: namely, that the present state of energy distribution and its gradient determines the future path of energy distribution evolution. The difference lies only in the encoding language: General Relativity formulates this law geometrically through spacetime curvature and affine connections, while the Schrödinger equation expresses it through quantum phase dynamics and probability amplitudes. Despite their distinct mathematical formulations and interpretive frameworks, both reflect a unified underlying principle—the causal propagation of energy configurations governed by extremal principles such as least action and entropy increase.

13.11. Due to the topological invariance of the spatial field in this model, the spatial coordinates of each field quantum are fixed (the space may deform, but the connectivity and adjacency relations remain unchanged). Each Space Elementary Quantum (SEQ) carries only two generalized coordinates: the field quantum resonance frequency (associated with field quantum spin and mutual spin synchronization, representing elastic potential energy at sub-Planckian elastic scales) and the field quantum resonance axis vector, denoted as (ωᵢ, n̂(i)). Consequently, the Hamiltonian formulation of this model is simpler, more intuitive, and more consistent with the physical process of energy redistribution and energy gradient configurations than those of traditional quantum field theory or general relativity, while naturally preserving global energy conservation and embedding thermodynamic arrow of time.

14. Preliminary Exploration of the Electromagnetic Interaction Physical Picture:

14.1. Electromagnetic Waves:

14.2. Closed Magnetic Fields of Charged Particles:

14.3. Spin-Generated Magnetic Moment Mechanism:

14.4. Magnetic Field of Moving Charges:

14.5. Theoretical Integration:

15. Discussion:

15.1. During the expansion of the universe, would the Planck constant have subtle changes?

15.2. Can a discrete differential geometry model, a spacetime nonlinear elastic coefficient function, and QCD simulations model be constructed to be compatible with this framework?

15.3 What would be the real emergent physical picture and interaction topology of electromagnetism ?

15.4 The next stage of this model could employ an algebra system to explore the closed transformations of M energy states on SEQ—encompassing (1) inter-SEQ translation effect (stress modulation), (2) spin, and (3) axial rotation—ultimately embedding this algebraic structure with the Standard Model.

15.5 Quark confinement and asymptotic freedom characterize the nonlinearity and asymmetry of spacetime’s elastic modulus at microscopic QCD scales. This behavior may extend to cosmic scales, potentially linking to variations in dark energy distribution density. QCD as an Intrinsic Property of Elastic Spacetime.

15.6 This framework suggests that the essence of QCD may ultimately reside in the elastic spacetime paradigm. Specifically, the non-perturbative features of quark confinement and asymptotic freedom could emerge from the topological connectivity patterns of adjacent SEQ - implying that studying Planck-scale SEQ adjacency configurations represents a fundamental pathway for deeper understanding of QCD dynamics beyond current effective field theories.

15.7 This framework is restricted to local interactions; non-local quantum entanglement falls outside its current scope.

15.8. The discrete field equations and discrete functionals in this model need to be built on a clear spatial adjacency topology. However, since the configuration of spatial adjacency topology remains undetermined at present, an exact mathematically formalized model cannot be provided. Therefore, the model can only remain at a conceptual stage for now.

16. Summary:

16.1. While this framework currently lacks complete mathematical formalization due to its foundational nature, the proposed quantization of spacetime provides a compelling new paradigm for offering a novel perspective to understand cosmic structure, time evolution, and thermodynamic principles.

16.2. If a computer model of the universe is developed with this framework, the first and second laws of thermodynamics and Principle of least action would be the main factors to drive the simulation, treating entropy as a dynamical coordinate for spontaneous system evolution’s simulation. The mathematical simplicity of our model reflects a deeper truth: the universe itself operates on fundamental rules that generate complexity through iteration. If the nonlinear and asymmetric elastic modulus between SEQ is modeled, such a computer-based physical simulation could further embed General Relativity and QCD, evolving into a more comprehensive physical simulation framework.

- Cubic

- Face-Centered Cubic (FCC)

- Hexagonal Close-Packed (HCP)

16.3. The analysis of entropy and action in the text operates at the Planck scale, where observable-level practical computability is unachievable, but this work provides a perspective to understand the concrete mechanisms of entropy and action from the Planck-scale .

16.4. This framework achieves a profound synthesis by embedding the Standard Model within Einstein’s elastic spacetime paradigm, revealing their unified geometric essence: (i) The SU(3) color symmetry corresponds physically to spherical compression modes of the spacetime quantum network, where gluon-mediated interactions preserve perfect 3D isotropy during local space compaction, while the resultant outward stretching generates the characteristic 1/r²gravitational field. (ii) The Higgs field operates as a chiral locking mechanism - its symmetry-breaking role emerges from how it pins compressed spacetime quanta to their deformation states, like a cosmic ratchet preventing elastic recoil. (iii) This framework proposes a hypothetical 3D multi-layered symmetric architecture for leptons: Different lepton generations manifest distinct charge and mass properties due to their varying layered configurations within the SEQ matrix. (iv) Dark matter and energy find natural explanations as topological defect vibrations and the ground-state tension of this crystalline spacetime fabric, respectively - no exotic particles required. Crucially, these phenomena all derive from a single principle: quantum spacetime compressible, defect-laden, yet topologically preserved nature.

16.5. In this framework, quantum superposition arises from the dynamic resonating, multi-layer, multi-axis rotation of a particle’s internal SEQ structure—a high-dimensional phase space of possible configurations prior to measurement. The eigenstates correspond to metastable solutions of this system, determined by its intrinsic parameters: mass distribution (gravitational potential storage), electromagnetic coupling, chiral symmetry constraints (e.g., Higgs locking), and initial conditions. Measurement collapses the rotating structure into one of these allowed states.

16.6. This work originates from a profound reflection on the nature of time. With no theory of time, definitions of physical processes would be fundamentally ambiguous.16.7. If the human observation is regarded as a physical interaction, then indeed it can lead to a change in quantum states. However, human observation is not fundamentally different from other physical interactions such as electromagnetic or other types of forces. We are, in the grand scheme of the universe, merely a small and fleeting process. Humility, therefore, should be our fundamental attitude towards the cosmos and our place within it.

17. Statement:

Funding

Conflict of interest Declaration

Appendix A

Appendix A.1 Speculative Diagram of Proton’s Internal Structure with Quarks and Gluons.

Appendix A.2. Degrees of Freedom in the Future and The essence of life in This Model:

| Feature | Advantages of Mathematical Formalization |

| Compression | Abstracts vast amounts of concrete experience into concise rules (e.g., “fire heats objects”) |

| Generalization | Applicable to novel situations (e.g., inferring combustibility of new materials) |

| Composability and Extensibility | Multiple rules can be combined to simulate complex behaviors (heat → steam → motion → tools) |

| Transmissibility | Easily shared across individuals (via language, symbols, education) |

| Predictability | Enables forward simulation: logical chains such as “if A, then B” |

- Power systems → enabling long chains from fossil fuels to electricity, mechanical work, and information processing;

- The Internet → accelerating knowledge diffusion, improving societal responsiveness and adaptive efficiency;

- Space exploration → probing new energy sources and novel topological configurations of space;

References

- Steeds, J.; Merli, P.G.; Pozzi, G.; Missiroli, G.; Tonomura, A. The double-slit experiment with single electrons. Phys. World 2003, 16, 20–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R. The Merli–Missiroli–Pozzi Two-Slit Electron-Interference Experiment. Phys. Perspect. 2012, 14, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, B.; Hall, D.B. Variation of the Rate of Decay of Mesotrons with Momentum. Phys. Rev. B 1941, 59, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie. Ann. der Phys. 1916, 354, 769–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.J.; Wilczek, F. Ultraviolet Behavior of Non-Abelian Gauge Theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1973, 30, 1343–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, H.D. Asymptotic freedom: An approach to strong interactions. Phys. Rep. 1974, 14, 129–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Zee, Quantum Field Theory in a Nutshell, Princeton University Press2003, ISBN: 9780691010199.

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooft, G.’. Quantum gravity as a dissipative deterministic system. Class. Quantum Gravity 1999, 16, 3263–3279. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. (2004). Quantum Gravity.Cambridge University Press.ISBN: 978-0521715966.

- Smolin, L. (2001). Three Roads to Quantum Gravity.Basic Books.ISBN: 978-0465078363.

- Sorkin, R.D. (2005). Causal Sets: Discrete Gravity. BOOK CHAPTER published in Series of the Centro De Estudios Científicos. Springer, Boston, MA. [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Topological quantum field theory. Commun. Math. Phys. 1988, 117, 353–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.S.; White, M. CDM models with a smooth component. Phys. Rev. D 1997, 56, R4439–R4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.-G. Quantum orders and symmetric spin liquids. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 65, 165113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.A. On the nature of quantum geometrodynamics. Ann. Phys. 1957, 2, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markopoulou, F.; Smolin, L. Disordered locality in loop quantum gravity states. Class. Quantum Gravity 2007, 24, 3813–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, D. Space-Time Code. Phys. Rev. B 1969, 184, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrvold, W.C. The Science of $${\Theta \Delta }^{\text{cs}}$$. Found. Phys. 2020, 50, 1219–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe, S.P. Superconducting Field Theory (Theory of Everything). J. Adv. Phys. 2023, 21, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamseddine, A.H.; Mukhanov, V. Discrete gravity. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitry Chelkak | Alexander Glazman | Stanislav Smirnov (2016). Discrete stress-energy tensor in the loop O(n) model. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Myers, T.G.; Sukra, B.A.D.; Gabrielse, G. Measurement of the Electron Magnetic Moment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 071801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoelito, M. de Souza.(2018). Discrete fields, general relativity, other possible implications and experimental evidences. arXiv:hep-th/0103218. [CrossRef]

- JGraph. (2021). draw.io (Version 15.5.2) [Computer software]. https://github.com/jgraph/drawio.

- Kalmbach H.E., Gudrun. (2021). Gravity with Color Charges. Journal of Emerging Trends in Engineering and Applied Sciences (JETEAS) 11(5):183-189 (ISSN: 2141-7016) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348602343_Gravity_with_Color_Charges.

- Sim, C.G. Gravitational Force is a Type of Physical Interaction between Gluon Fields: Molecular Motions of Gases. Phys. Sci. Int. J. 2021, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, S. . (2002). A new kind of science. Wolfram Media. https://www.wolframscience.com/nks/.

- Zou, Z. K. (2025). The Arrow of Time under The Mapping model between time set and entropy set. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Raut, U. A General Relativistic Approach for Non-Perturbative QCD. J. High Energy Physics, Gravit. Cosmol. 2023, 09, 917–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethan Richards. A Complete Unified Theory of Space Compression- Resolving Fundamental Physics Through Mechanical Principles. Academia.edu https://www.academia.edu/125340292/_A_Complete_Unified_Theory_of_Space_Compression_Resolving_Fundamental_Physics_Through_Mechanical_Principles.

- Ryuya Fukuda, Masataka Iinuma, Yuto Matsumoto, Holger F. Hofmann. Experimental evidence for the physical delocalization of individual photons in an interferometer. arXiv:2505.00336 [quant-ph]. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Maxwell. LI. On physical lines of force. published May 1861 in The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. [CrossRef]

- David Cornberg. https://independent.academia.edu/DavidCornberg John Duffield https://physicsdetective.com/.

- Louis de Broglie.(1924). Recherches sur la théorie des quanta, Faculté des Sciences de Paris, Thèse de doctorat soutenue à Paris le 25 novembre 1924. On the theory of quanta, english translation by A.F. Kracklauer. https://fondationlouisdebroglie.org/LDB-oeuvres/De_Broglie_Kracklauer.pdf.

- Volovik, G. E. . (2009). The Universe in a Helium Droplet. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Katanaev, M. O. , & Volovich, I. V.. (1992). Theory of defects in solids and three-dimensional gravity. Annals of Physics, 216(1), 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Vladimir, Leonov. (2024). V.S. Leonov (1996). Book The Theory of Elastic Quantized Space (EQS). [CrossRef]

- Barceló, C. , Liberati, S. & Visser, M. Analogue Gravity. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).