Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

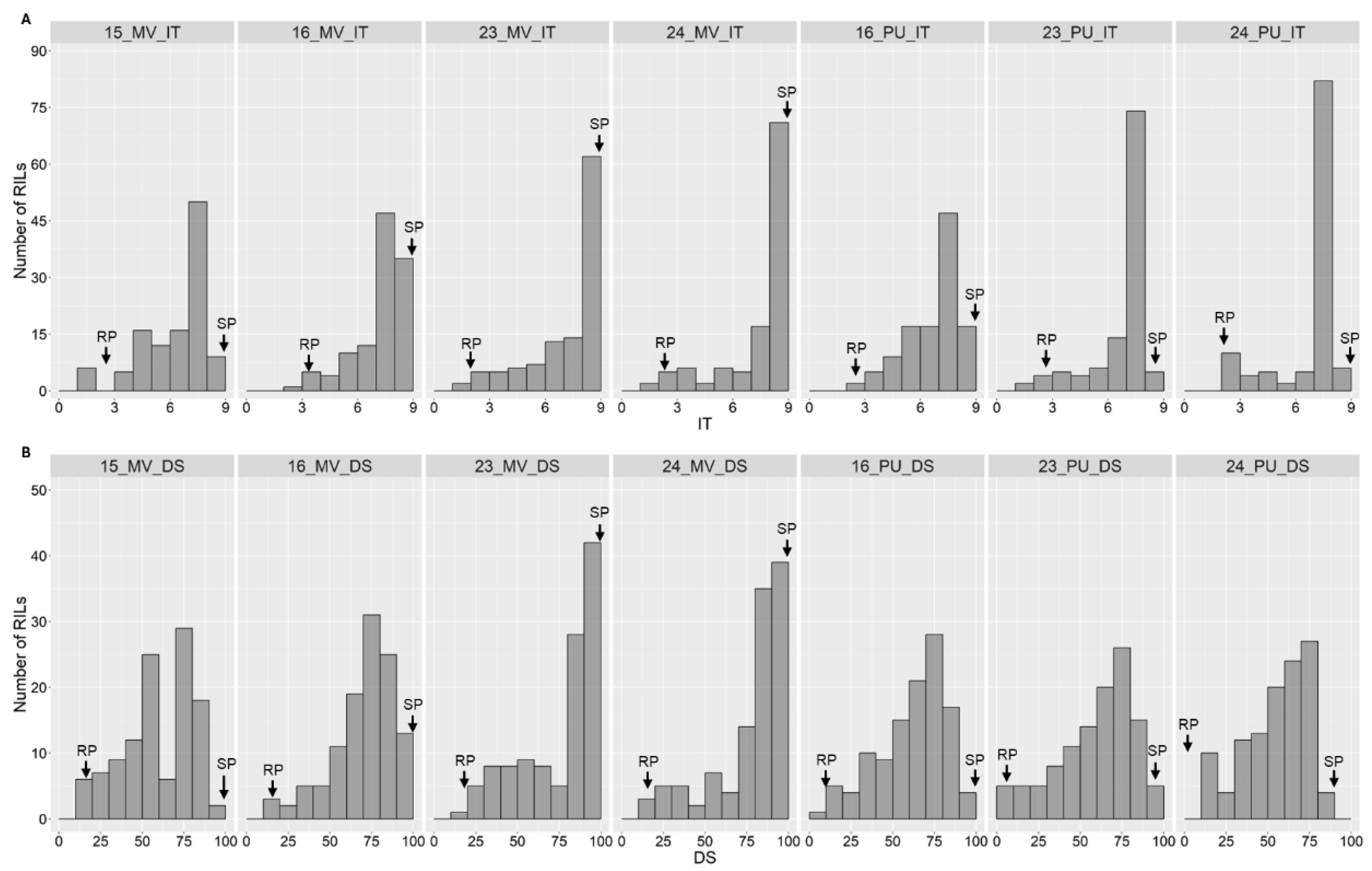

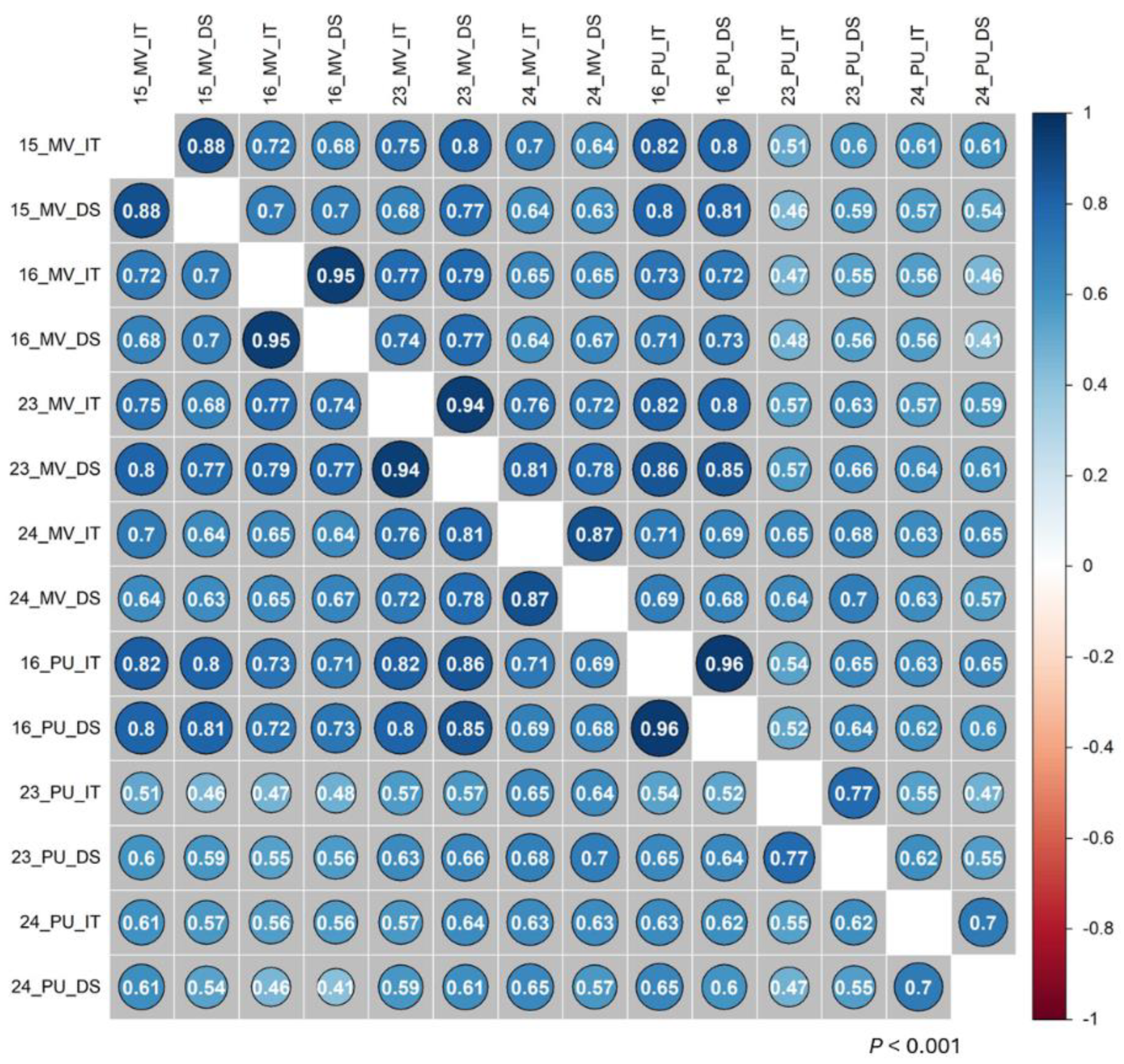

2.1. Stripe Rust Phenotypes

2.2. Linkage Map

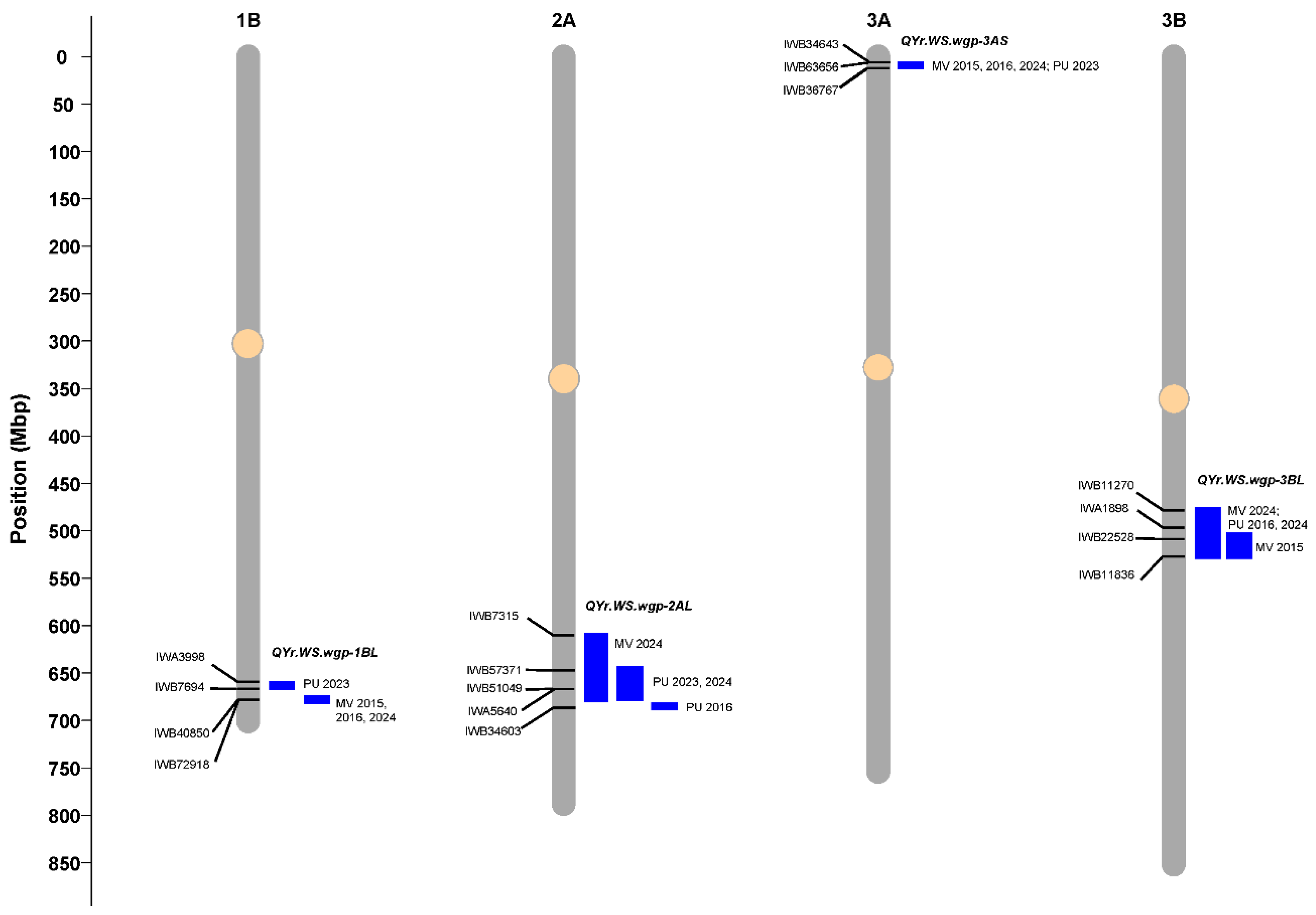

2.3. Stripe Rust Resistance QTL

2.4. KASP Markers

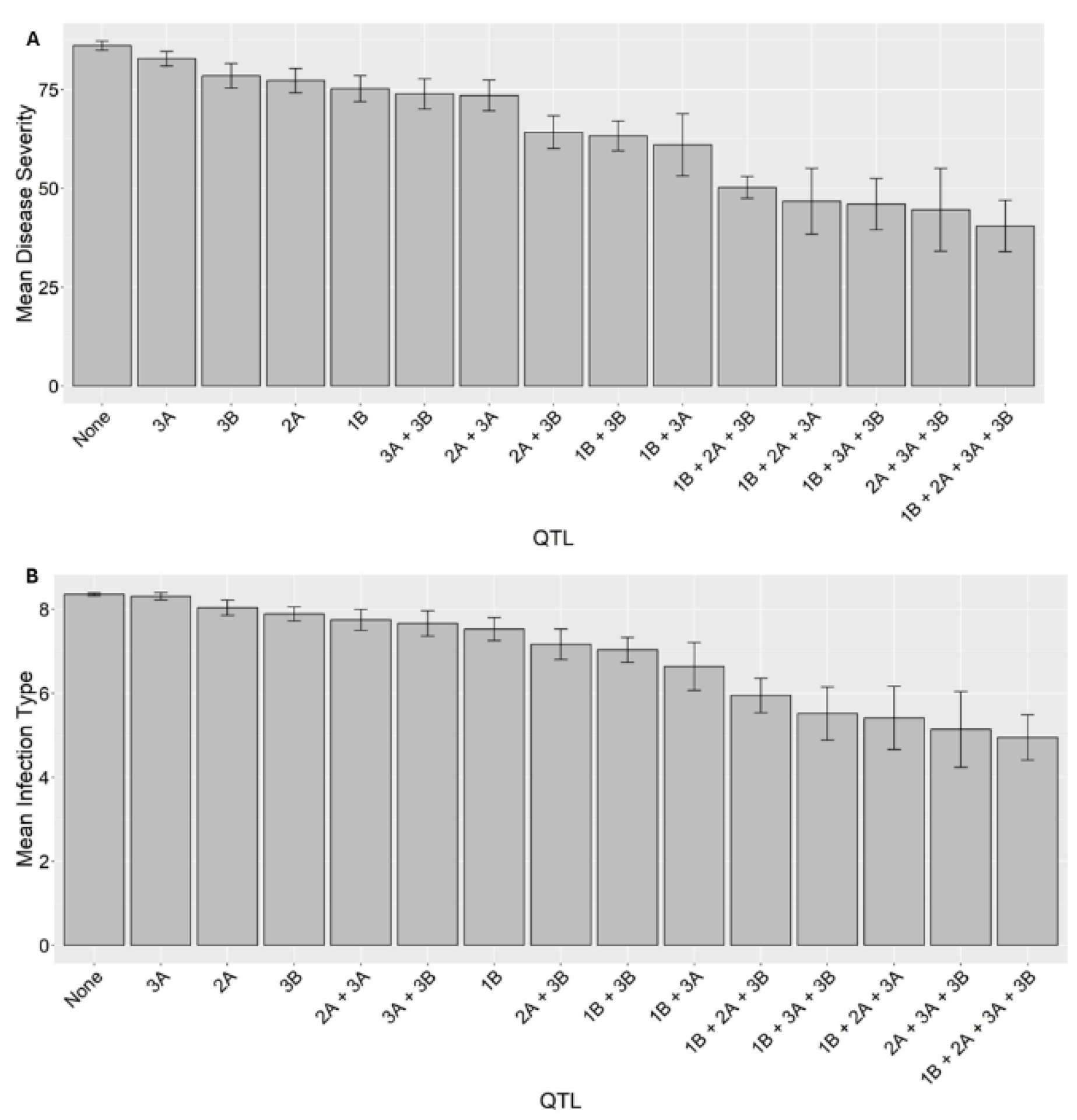

2.5. Effects of QTL Combinations

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

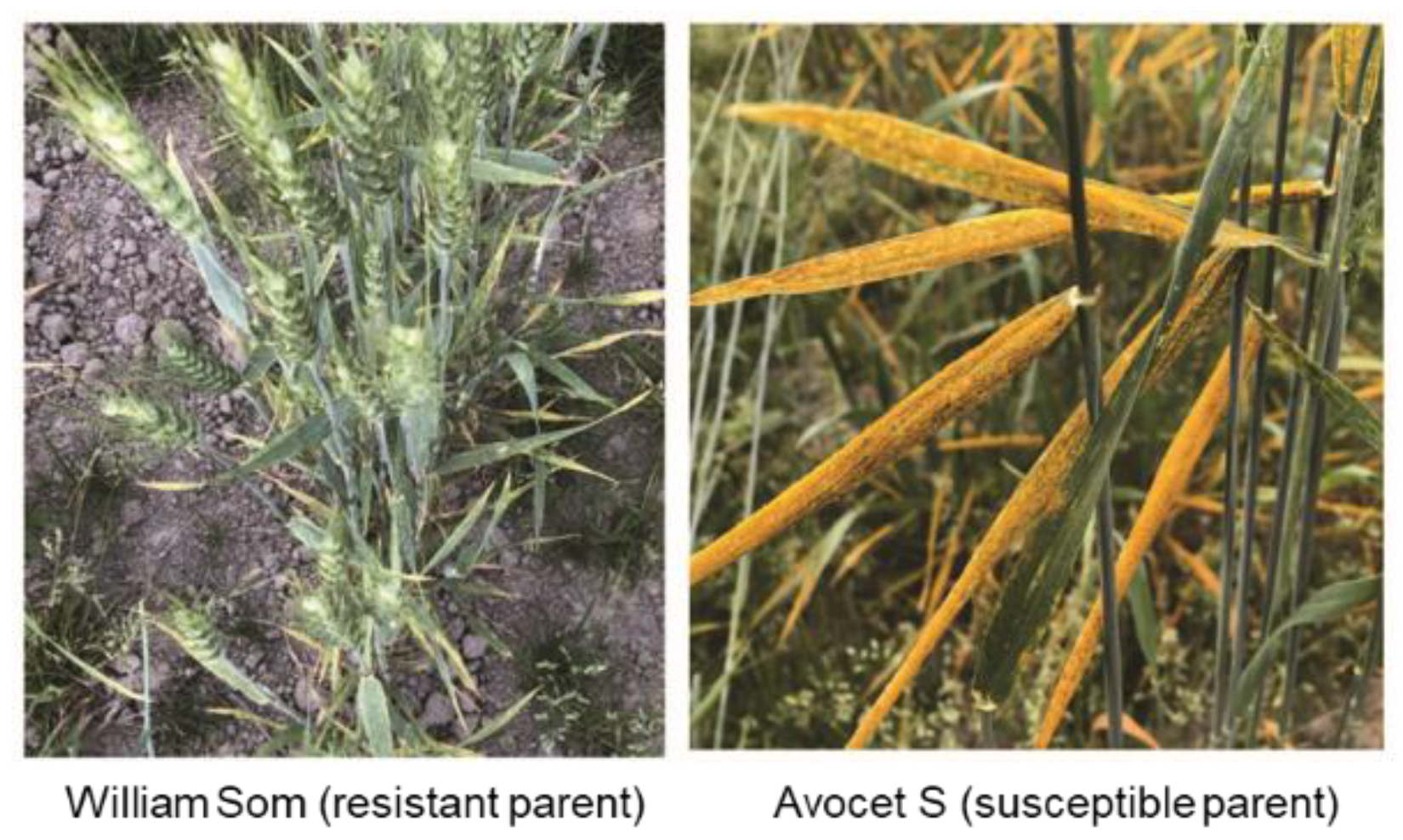

4.1. Plant Materials and Population Development

4.2. Stripe Rust Phenotyping

4.3. Stripe Rust Data Analyses

4.4. DNA Extracting, Genotyping, and SNP Calling

4.5. Linkage Map Construction and QTL Analysis

4.6. KASP Marker Development and Genotyping

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Pst | Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici |

| Yr | Yellow rust |

| HTAP | High-temperature and adult-plant resistance |

| ASR | All-stage resistance |

| QTL | Quantitative trait loci |

| PNW | Pacific Northwest |

| WS | William Som |

| AvS | Avocet S |

| RILs | Recombinant inbred lines |

| KASP | Kompetitive allele-specific PCR |

| SNPs | Single nucleotide polymorphisms |

| NPGS | National Plant Germplasm System |

| NSGC | National Small Grains Collection |

| IT | Infection type |

| DS | Disease severity |

| GS | Growth stage |

| cM | Centimorgan |

| wgp | Wheat genetics at Pullman |

| PVE | Phenotypic variation explained |

References

- Chen, X.M. Epidemiology and control of stripe rust [Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici] on wheat. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2005, 27, 314–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.M. Pathogens which threaten food security: Puccinia striiformis, the wheat stripe rust pathogen. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.M. High-temperature adult-plant resistance, key for sustainable control of stripe rust. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 608–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, R.F. Stripe rust of wheat and barley in North America: a retrospective historical review. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2002, 40, 75–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.L.; Wan, A.M.; Liu, D.C.; Chen, X.M. Changes of races and virulence genes in Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, the wheat stripe rust pathogen, in the United States from 1968 to 2009. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 1522–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.N.; Wan, A.M.; Chen, X.M. Race characterization of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in the United States from 2013 to 2017. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.N.; Chen, X.M. Stripe rust resistance. In Stripe Rust; Chen, X.M., Kang., Z.S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2017; pp. 353–558. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.M. Integration of cultivar resistance and fungicide application for control of wheat stripe rust. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 36, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhaya, A.; Upadhaya, S.G.; Brueggeman, R. The wheat stem rust (Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici) population from Washington contains the most virulent isolates reported on barley. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, R.A. Catalogue of Gene Symbols of Wheat. 2024, https://wheat.pw.usda.gov/GG3/wgc. Accessed 20 March 2025.

- Feng, J.Y.; Wang, M.N.; See, D.R.; Chao, S.M.; Zheng, Y.L.; Chen, X.M. Characterization of novel gene Yr79 and four additional quantitative trait loci for all-stage and high-temperature adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in spring wheat PI 182103. Phytopathology 2018, 108, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.H.; Chen, X.M.; Garland-Campbell, K.; Kidwell, K.K. Identifying QTL for high-temperature adult-plant resistance to stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici) in the spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivar ‘Louise’. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 119, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, M.N.; Feng, J.Y.; See, D.R.; Chao, S.M.; Chen, X.M. Combination of all-stage and high-temperature adult-plant resistance QTL confers high-level, durable resistance to stripe rust in winter wheat cultivar Madsen. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 1835–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santra, D.K.; Chen, X.M.; Santra, M.; Campbell, K.G.; Kidwell, K.K. Identification and mapping QTL for high-temperature adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivar ‘Stephens’. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2008, 117, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Chen, X.M. Quantitative trait loci for non-race-specific, high-temperature adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in wheat cultivar Express. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 118, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Zhang, Z.J.; Xu, Y.B.; Li, G.H.; Feng, J.; Zhou, Y. Quantitative trait loci for high-temperature adult-plant and slow-rusting resistance to Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in wheat cultivars. Phytopathology 2008, 98, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Yuan, C.Y.; Wang, M.N.; See, D.R.; Zemetra, R.S.; Chen, X.M. QTL analysis of durable stripe rust resistance in the North American winter wheat cultivar Skiles. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 1677–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.J.; Wang, M.N.; See, D.R.; Yang, E.N.; Chen, G.Y.; Chen, X.M. Identification of 39 stripe rust resistance loci in a panel of 465 winter wheat entries presumed to have high-temperature adult-plant resistance through genome-wide association mapping and marker-assisted detection. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1514926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satam, H.; Joshi, K.; Mangrolia, U.; Waghoo, S.; Zaidi, G.; Rawool, S.; Thakare, R.P.; Banday, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Das, G.; Malonia, S.K. Next-generation sequencing technology: current trends and advancements. Biol. 2023, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, M.; Upadhaya, A.; Clare, S.; Brueggeman, R. QTL analysis of a novel source of barley seedling resistance effective against virulent North American stem rust isolates. Phytopathology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhaya, A.; Upadhaya, S.G.; Brueggeman, R. Identification of candidate avirulence and virulence genes corresponding to stem rust (Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici) resistance genes in wheat. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2024, 37, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhaya, A.; Upadhaya, S.G.; Brueggeman, R. Association mapping with a diverse population of Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici identified avirulence loci interacting with the barley Rpg1 stem rust resistance gene. BMC Genomics 2024, 25, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, P.; Yang, Z.; Xu, C. Genetic mapping of quantitative trait loci in crops. Crop J. 2017, 5, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.N.; Chen, X.M.; Xu, LS. .; Cheng, P.; Bockelman, H.E. Registration of 70 common spring wheat germplasm lines resistant to stripe rust. J. Plant Regist. 2012, 6, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Wang, L.; Rimbert, H.; Rodriguez, J.C.; Deal, K.R.; De Oliveira, R.; Choulet, F.; Keeble-Gagnere, G.; Tibbits, J.; Rogers, J.; Eversole, K.; Appels, R.; Gu, Y.Q.; Mascher, M.; Dvorak, J.; Luo, M.C. Optical maps refine the bread wheat Triticum aestivum cv. Chinese Spring genome assembly. Plant J. 2021, 107, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, M.; Singh, R.P.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Islas, S.O.; Hoisington, D. Molecular marker mapping of leaf rust resistance gene Lr46 and its association with stripe rust resistance gene Yr29 in wheat. Phytopathology 2003, 93, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, H.M.; Singh, R.P.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Palacios, G.; Suenaga, K. Characterization of genetic loci conferring adult plant resistance to leaf rust and stripe rust in spring wheat. Genome 2006, 49, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, U.K.; Kazi, A.G.; Singh, B.; Hare, R.A.; Bariana, H. S. Mapping of durable stripe rust resistance in a durum wheat cultivar Wollaroi. Mol. Breed. 2014, 33, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranwal, D.K.; Bariana, H.; Bansal, U. Genetic dissection of stripe rust resistance in a Tunisian wheat landrace Aus26670. Mol. Breed. 2021, 41, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosewarne, G.M.; Singh, R.P.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Rebetzke, G.J. Quantitative trait loci for slow-rusting resistance in wheat to leaf rust and stripe rust identified with multi-environment analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2008, 116, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qie, Y.M.; Li, X.; Wang, M.N.; Chen, X.M. Genome-wide mapping of quantitative trait loci conferring all-stage and high-temperature adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in spring wheat landrace PI 181410. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, U.K.; Hayden, M.J.; Keller, B.; Wellings, C.R.; Park, R.F.; Bariana, H.S. Relationship between wheat rust resistance genes Yr1 and Sr48 and a microsatellite marker. Plant Pathol. 2009, 58, 1039–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, L.; Afshari, F.; Christiansen, M.J.; McIntosh, R.A.; Jahoor, A.; Wellings, C.R. Yr32 for resistance to stripe (yellow) rust present in the wheat cultivar Carstens V. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 108, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Cao, Q.; Han, D.; Wu, J.; Wu, L.; Tong, J.; Xu, X.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, K.; Wang, F.; Dong, Y.; Gao, C.; He, Z.; Xia, X.; Hao, Y. Molecular characterization and validation of adult-plant stripe rust resistance gene Yr86 in Chinese wheat cultivar Zhongmai 895. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.L.; Wang, W.L.; Wang, L.L.; Hou, D.Y.; Jing, J.X.; Wang, Y. , Xu, Z.Q.; Yao, Q.; Yin, J.L.; Ma, D.F. Genetics and molecular mapping of genes for high-temperature resistance to stripe rust in wheat cultivar Xiaoyan 54. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2011, 123, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yuan, C.Y.; Wang, M.N.; See, D.R.; Chen, X.M. Mapping quantitative trait loci for high-temperature adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in spring wheat PI 197734 using a doubled haploid population and genotyping by multiplexed sequencing. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 596962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, B.; Gao, X.; Cao, N.; Ding, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, Y.; Xin, Z.; Zhang, L. QTL mapping for adult plant resistance to wheat stripe rust in M96-5 × Guixie 3 wheat population. J. Appl. Genet. 2022, 63, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzand, M.; Dhariwal, R.; Hiebert, C.W.; Spaner, D.; Randhawa, H.S. QTL mapping for adult plant field resistance to stripe rust in the AAC Cameron/P2711 spring wheat population. Crop Sci. 2022, 62, 1088–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Gong, F.; Jin, Y.; Xia, Y.; He, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; He, J.; Feng, L.; Chen, G.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, D.; Huang, L.; Wu, B. Identification and mapping of QTL for stripe rust resistance in the Chinese wheat cultivar Shumai126. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Feng, J.Y.; Wang, M.N.; Chen, X.M.; See, D.R.; Wan, A.M.; Wang, T. Molecular mapping of stripe rust resistance gene Yr76 in winter club wheat cultivar Tyee. Phytopathology 2016, 106, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Hu, T.; Li, X.; Yu, M.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Huang, K.; Han, D.; Kang, Z. Genome-wide mapping of adult plant stripe rust resistance in wheat cultivar Toni. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 1693–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; He, Z.; Rasheed, A.; Wu, L.; Cao, S.; Nan, H.; Xia, X. Genome-wide association mapping of adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in common wheat (Triticum aestivum). Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 2174–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsabiyera, V.; Bariana, H.S.; Qureshi, N.; Wong, D.; Hayden, M.J.; Bansal, U.K. Characterization and mapping of adult plant stripe rust resistance in wheat accession Aus27284. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 1459–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakeerathan, K.; Bariana, H.; Qureshi, N.; Wong, D.; Hayden, M.; Bansal, U. Identification of a new source of stripe rust resistance Yr82 in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 3169–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, M.; Awan, F.S.; Sadia, B.; Zia, M.A. Genome-wide association mapping for stripe rust resistance in Pakistani spring wheat genotypes. Plants 2020, 9, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Z.; Ali, M.; Mirza, J.I.; Fayyaz, M.; Majeed, K.; Naeem, M.K.; Aziz, A.; Trethowan, R.; Ogbonnaya, F.C.; Poland, J.; Quraishi, U.M.; Hickey, L.T.; Rasheed, A.; He, Z. Genome-wide association and genomic prediction for stripe rust resistance in synthetic-derived wheats. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 788593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.M.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.N.; See, D.R.; Han, D.J.; Chen, X.M. Genome-wide association study and gene specific markers identified 51 genes or QTL for resistance to stripe rust in U.S. winter wheat cultivars and breeding lines. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; He, Z.; Rasheed, A.; Wu, L.; Cao, S.; Nan, H.; Xia, X. Genome-wide association mapping of adult-plant resistance to stripe rust in common wheat (Triticum aestivum). Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 2174–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavani, S.; Singh, R.P.; Hodson, D.P.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Randhawa, M.S. Wheat rusts: current status, prospects of genetic control and integrated approaches to enhance resistance durability. In Wheat improvement: Food Security in a changing climate; Reynolds, M.P., Braun, H.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wang, M.N.; Zhang, Z.W.; See, D.R.; Chen, X.M. Identification of stripe rust resistance loci in U.S. spring wheat cultivars and breeding lines using genome-wide association mapping and Yr gene markers. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 2181–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadoks, J.C.; Chang, T.T.; Konzak, C.F. A decimal code for the growth stages of cereals. Weed Res. 1974, 14, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Line, R.F.; Qayoum, A. Virulence, aggressiveness, evolution and distribution of races of Puccinia striiformis (the cause of stripe rust of wheat) in North America, 1968-87. U.S. Department of Agriculture Technical Bulletin No. 1788, the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, USA, 1992; pp 44.

- Peterson, R.F.; Campbell, A.B.; Hannah, A.E. A diagrammatic scale for estimating rust intensity on leaves and stems of cereals. Can. J. Res. 1948, 26, 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.M.; Line, R.F. Gene action in wheat cultivars for durable, high-temperature, adult-plant resistance and interaction with race-specific, seedling resistance to Puccinia striiformis. Phytopathology 1995, 85, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: South Carolina, USA, 2016; pp. 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, T.; Simko, V.; Levy, M.; Xie, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zemla, J. Corrplot: Visualization of a correlation matrix. R package version 0.73 2013, 230, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, P.J.; Zhang, Z.; Kroon, D.E.; Casstevens, T.M.; Ramdoss, Y.; Buckler, E.S. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2633–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J. QTL IciMapping: Integrated software for genetic linkage map construction and quantitative trait locus mapping in biparental populations. Crop J. 2015, 3, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosambi, D.D. The estimation of map distances from recombination values. Ann. Eugen. 1944, 12, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Source of variations | Df | Sum Sq. | Mean Sq. | F-value | Pr (>F) |

| Infection type | Genotype (G) | 113 | 3315 | 29.33 | 45.83 | <2e-16 |

| Environment (E) | 6 | 174 | 28.98 | 45.28 | <2e-16 | |

| G×E | 669 | 1246 | 1.86 | 2.9 | <2e-16 | |

| Error | 789 | 505 | 0.64 | |||

| Disease severity | Genotype (G) | 113 | 546121 | 4833 | 39.86 | <2e-16 |

| Environment (E) | 6 | 132776 | 22129 | 182.52 | <2e-16 | |

| G×E | 669 | 195494 | 292 | 2.41 | <2e-16 | |

| Error | 789 | 95661 | 121 |

| QTL | Chr. | Interval (Mbp)a |

Left marker | Position (bp) |

Right marker | Position (bp) |

LOD | PVEb | Traitc |

| QYrWS.wgp-1BL | 1B | 669 - 682 | IWA3998 | 669,136,631 | IWB7694 | 675,532,521 | 4.5 | 13.5 | PU_2023_DS |

| IWB7694 | 675,532,521 | IWB40850 | 681,737,056 | 5.2 | 15.4 | MV_2024_IT | |||

| IWB7694 | 675,532,521 | IWB40850 | 681,737,056 | 7.4 | 19.0 | MV_2024_DS | |||

| IWB7694 | 675,532,521 | IWB72918 | 682,339,545 | 4.7 | 10.0 | MV_2015_DS | |||

| IWB7694 | 675,532,521 | IWB72918 | 682,339,545 | 4.7 | 12.2 | MV_2016_DS | |||

| QYrWS.wgp-2AL | 2A | 611 - 684 | IWB7315 | 611,614,334 | IWB57371 | 643,705,482 | 3.7 | 10.2 | MV_2024_IT |

| IWB57371 | 643,705,482 | IWB51049 | 678,678,971 | 4.0 | 11.0 | PU_2023_DS | |||

| IWB57371 | 643,705,482 | IWB51049 | 678,678,971 | 5.7 | 16.7 | PU_2024_DS | |||

| IWB57371 | 643,705,482 | IWB51049 | 678,678,971 | 4.9 | 12.0 | MV_2024_DS | |||

| IWA5640 | 679,489,440 | IWB34603 | 684,696,382 | 6.8 | 11.9 | PU_2016_IT | |||

| QYrWS.wgp-3AS | 3A | 9 -13 | IWB34643 | 8,940,939 | IWB36767 | 13,212,163 | 3.5 | 7.0 | PU_2023_DS |

| IWB63656 | 8,942,306 | IWB36767 | 13,212,163 | 6.2 | 15.9 | MV_2016_DS | |||

| IWB63656 | 8,942,306 | IWB36767 | 13,212,163 | 3.2 | 6.9 | MV_2024_DS | |||

| IWB63656 | 8,942,306 | IWB36767 | 13,212,163 | 3.3 | 7.3 | MV_2015_DS | |||

| QYrWS.wgp-3BL | 3B | 476 - 535 | IWB11270 | 476,376,513 | IWB22528 | 512,777,195 | 11.5 | 27.8 | PU_2016_DS |

| IWB11270 | 476,376,513 | IWB11836 | 535,559,634 | 8.7 | 15.7 | PU_2016_IT | |||

| IWB11270 | 476,376,513 | IWB11836 | 535,559,634 | 3.7 | 12.0 | PU_2024_DS | |||

| IWB11270 | 476,376,513 | IWB11836 | 535,559,634 | 3.5 | 12.9 | MV_2024_DS | |||

| IWA1898 | 499,086,813 | IWB11836 | 535,559,634 | 5.8 | 12.6 | MV_2015_DS |

| KASP marker | SNP marker | Primer | Sequence (5' - 3')a | QTL |

| IWA3998 | wsnp_Ex_c4774_8519623 | Forward1 | GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTGAGTTTTCAGGCCTTGGAGGG | QYrWS.wgp-1BL |

| Forward2 | GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTGGAGTTTTCAGGCCTTGGAGGA | |||

| Common reverse | CTGGGTCGTCAGTTTGACTTAAGCAT | |||

| IWB7694 | BS00028747_51 | Forward1 | GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTGGACTGGAGCAAAATTTCAAGTGTAA | QYrWS.wgp-1BL |

| Forward2 | GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTGGACTGGAGCAAAATTTCAAGTGTAG | |||

| Common reverse | CCCAGCTGCACATTGTAAATTCCGTT | |||

| IWA5640 | wsnp_EX_rep_c69799_68761171 | Forward1 | GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTAGCCCTTCACCTTGATCACCTT | QYrWS.wgp-2AL |

| Forward2 | GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTAGCCCTTCACCTTGATCACCTC | |||

| Common reverse | TCCTTAACGAGGAGCTTGCAGACAT | |||

| IWB34603 | IAAV2718 | Forward1 | GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTGAAGTTTCAAGATATAAACCAAGTGCATG | QYrWS.wgp-2AL |

| Forward2 | GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTGAAGTTTCAAGATATAAACCAAGTGCATA | |||

| Common reverse | CTGCCTAGCCAATCTGTTTATATCTTGTA | |||

| IWB63656 | RFL_Contig1488_671 | Forward1 | GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTTCCAGTCCAACGCAAGCTGGA | QYrWS.wgp-3AS |

| Forward2 | GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTCCAGTCCAACGCAAGCTGGG | |||

| Common reverse | AGGAACAGGCTCAGGGCAGGAT | |||

| IWB36767 | Jagger_c8039_67 | Forward1 | GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTATGTTAAACATAGGAGTATCACAAAAGATG | QYrWS.wgp-3AS |

| Forward2 | GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTATAATGTTAAACATAGGAGTATCACAAAAGATA | |||

| Common reverse | CTTTTGTAGTAACATTTTCTGCTATTGGTA | |||

| IWB11270 | BS00082644_51 | Forward1 | GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTCAAACCGTATACATGTATGTCTATCCT | QYrWS.wgp-3BL |

| Forward2 | GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTAAACCGTATACATGTATGTCTATCCC | |||

| Common reverse | GCTCCGAACCAATCGCCGGTA | |||

| IWB22528 | Excalibur_c14999_712 | Forward1 | GAAGGTGACCAAGTTCATGCTCCTTGTTGATTCTCTCTTCAGAGC | QYrWS.wgp-3BL |

| Forward2 | GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTCCCTTGTTGATTCTCTCTTCAGAGT | |||

| Common reverse | CGCTACTCTCCAATGTTTTTGCGAAAATT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).