1. Introduction

Equestrian sports are growing in popularity at national and international levels around the world. The Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) Database lists approximately 478,000 horses, with nearly 77,000 horses registered by national federations each year [

1]. This increasing number of horses involved in the equestrian industry coincides with growing concerns regarding animal welfare, particularly for older registered horses. Ageing refers to the decline over time in the functioning of vital organs, including the cardiovascular system [

2,

3], which can lead to reduced exercise capacity and impaired thermoregulation [

2]. Additionally, the maximal rate of oxygen consumption (VO

2max) in horses tends to decrease with age [

3]. Research indicates that older horses also exhibit reduced muscle oxidative capacity and a shift towards more glycolytic properties [

4]. Thus, ageing negatively impacts bodily systems and potentially impairs homeostasis. It is widely accepted that physiological functions in horses start to decline after they reach 15 years of age, with the onset of senescence [

5,

6]. However, some horses continue to compete successfully even beyond the age of 20 [

6,

7]. The use of older horses in equestrian sports—when their physical abilities are naturally diminished—may expose them to increased stress and could negatively affect their well-being during training or competition.

Determining physiological stress parameters at rest or during groundwork provides benefits in exploring the consequences of stress levels and adaptation following exercise training. In this regard, heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) have frequently been implemented to monitor stress and neurophysiological responses to various conditions and challenges in both humans [

8,

9,

10,

11] and horses [

12,

13,

14]. HRV describes a rhythmic fluctuation in time intervals between consecutive heartbeats. This variation is mediated by sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal) impulses acting on the sinoatrial node of the heart during the cardiac cycle [

15,

16,

17,

18]. This natural phenomenon reflects the flexibility and adaptability of the body system in coping with stressful stimuli and maintaining homeostasis [

16,

19].

Several HRV metrics can indicate the extent of either independent vagal influence or a combination of sympathetic and vagal activity. Long-term variation in heart rate is reflected in measures including the beat-to-beat (RR) interval, standard deviation of normal-to-normal RR interval (SDNN), standard deviation of the averages of RR intervals in 5-min segments (SDANN), mean of the standard deviations of RR intervals in 5-min segments (SDNNI), low-frequency (LF) band, and standard deviation of Poincaré plot along the line of identity (SD2), which are influenced by the interplay of sympathetic and vagal components [

17,

20]. In contrast, short-term variations reflecting parasympathetic vagal dominance can be measured by metrics including the square root of the mean squared differences between successive RR intervals (RMSSD), number of successive RR interval pairs that differ more than 50 ms (NN50) and NN50 divided by the total number of RR intervals (pNN50), high-frequency (HF) band, and standard deviation of Poincaré plot perpendicular to the line of identity (SD1) [

16,

17]. A decrease in resting HR and multiple HRV metrics has been reported in horses as they age [

21,

22]. However, these physiological responses can be improved in geriatric horses through structured exercise [

23,

24].

Although geriatric horses can be trained for and succeed in equestrian competitions, it is still unclear to what extent their welfare is maintained when their sports careers extend beyond retirement age. This study aimed to investigate animal welfare by observing resting HR and various HRV metrics in geriatric horses involved in equestrian sports or physical training. These geriatric horses were compared to adult horses under similar conditions. The hypothesis was that resting HR and HRV metrics would differ between adult and geriatric horses engaged in various levels of activity. Additionally, it was expected that both age and activity levels would influence the expression of HR and HRV metrics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Horses

Fifty-one horses (4 stallions, 24 geldings, 23 mares) aged between 7–20 years and weighing 321–435 kg were selected from the Horseshoe Point Riding Club, Chonburi, Thailand (location: 12.906695, 100.96976). The horses participated in various physical activities, including regular training for equestrian sports—particularly dressage—as well as school riding and periods of rest. The horses were housed in well-ventilated 3 x 4 m stables with straw bedding, with ad libitum tap water and hay. Approximately 1.5–2 kg of commercial pellets with 90 g of electrolytes were given daily across three distribution times. The horses were also left in the paddock for 2–3 hours on non-exercise days. All horses underwent physical and echocardiographic examinations to identify any cardiac disorders. Five horses were excluded from the study due to cardiac arrhythmia, manifesting as bradycardia, atrioventricular block, and supraventricular premature beats. Accordingly, data were collected for 46 horses in this study. The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Kasetsart University Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee (ACKU68-VET-023; April 1, 2025).

2.2. Experimental Protocols

Horses were categorised into four groups based on their ages and activity levels, as shown in

Table 1. The activity levels fell into two patterns: 1) Horses engaged in daily aerobic training, especially for equestrian dressage, which included 15–20 minutes of walking, 15–20 minutes of trotting, and 10 minutes of cantering. The total duration is approximately 40–50 minutes per day, three to five days a week (AL-1). 2) Horses used for school riding by practising combined walking and trotting for 35–45 minutes, along with a 5-minute canter, one day a week or less (AL-2). Horses were left in the paddock for two to three hours on non-exercise days.

Horses were equipped with a heart rate monitoring (HRM) device (Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland), which has been demonstrated to generate reliable RR interval data from which HRV metrics can be derived [

25,

26,

27,

28]. The Polar equine belt for riding was soaked in water and then fitted, using ultrasound gel at the electrode surface to enhance electrical transmission. The heart rate sensor (H10) was subsequently attached to the belt and fastened around the chest, with the sensor pocket positioned on the left side of the chest. Finally, the sensor was wirelessly linked to the Polar sports watch (Vantage 3) to obtain RR interval data. The HRM device was installed on the horses for approximately 10 minutes before each 30-minute session of data recording. This procedure helps familiarise horses with the device, thereby reducing the confounding factor of anxiety-related distortion of HRV metrics.

The Polar sports watch was connected to the FlowSync software program (

https://flow.polar.com/start: accessed on 13 March 2025) to transfer RR interval data, which was subsequently exported as comma-separated values (CSV) files. These files were then uploaded to the Kubios premium program version 4.1.2.1 (Kubios HRV scientific:

https://www.kubios.com/hrv-premium/: accessed on 13 March 2025) for the calculation of specific HRV metrics. HRV data were eventually exported as MATLAB MAT files. HRV results can be distorted by artefacts such as missing, extra, misaligned, or ectopic beats (including premature ventricular contractions or other arrhythmias). To address this issue, an automatic artefact correction feature was utilised to ensure the accuracy of the aligned RR intervals. Additionally, automatic noise detection was applied at a medium level to filter out noisy segments that could lead to distortions in the analysis of consecutive beats. The smoothness priors method was also implemented to eliminate non-stationarities within the RR interval time series. The cutoff frequency set for trend removal was 0.035 Hz, as denoted in the user guidelines (

https://www.kubios.com/downloads/Kubios_HRV_Users_Guide.pdf, accessed 13 March 2025).

HRV metrics derived from 30-minute recordings were reported in three domain analyses: 1) Time domain analysis: Mean HR, RR interval, SDNN, SDANN, SDNNI, RMSSD, pNN50, deceleration capacity of heart rate computed as a four-point difference (DC), and stress index; 2) Frequency domain analysis: LF band (frequency threshold: 0.01–0.07 Hz), HF band (frequency threshold: 0.07–0.6 Hz), total power, and LF/HF ratio; and 3) Nonlinear analysis: SD1, SD2, and the SD2/SD1 ratio.

2.3. Data Analysis

HRV data were statistically analysed using GraphPad Prism version 10.4.2 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A two-way repeated measures ANOVA was utilised to determine the independent effects of horses’ age and activity levels, as well as the interaction effect between horses’ age and activity levels on the expression of HR and HRV metrics. Differences within and between groups were evaluated using uncorrected Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test. The effect size was determined using Eta squared (

ƞ2) and denoted as very small (

ƞ2 < 0.01), small (0.01 ≤

ƞ2 < 0.06), medium (0.06 ≤

ƞ2 < 0.14), or large (

ƞ2 ≥ 0.14) [

29]. The results are presented as mean ± SD, and statistical significance was considered at

p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Time Domain Results

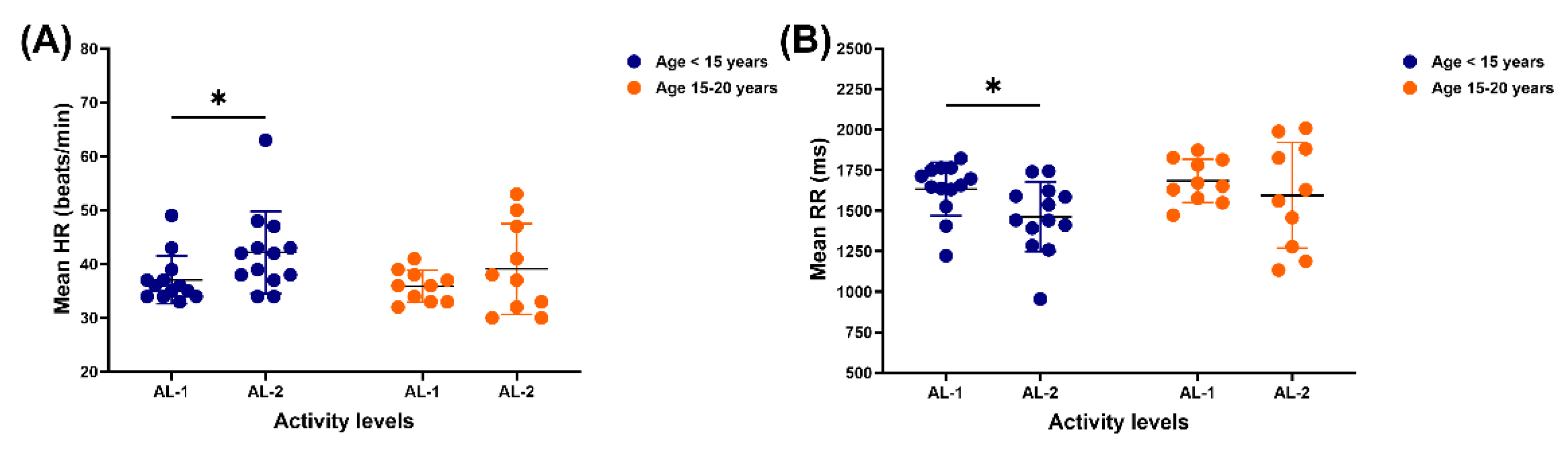

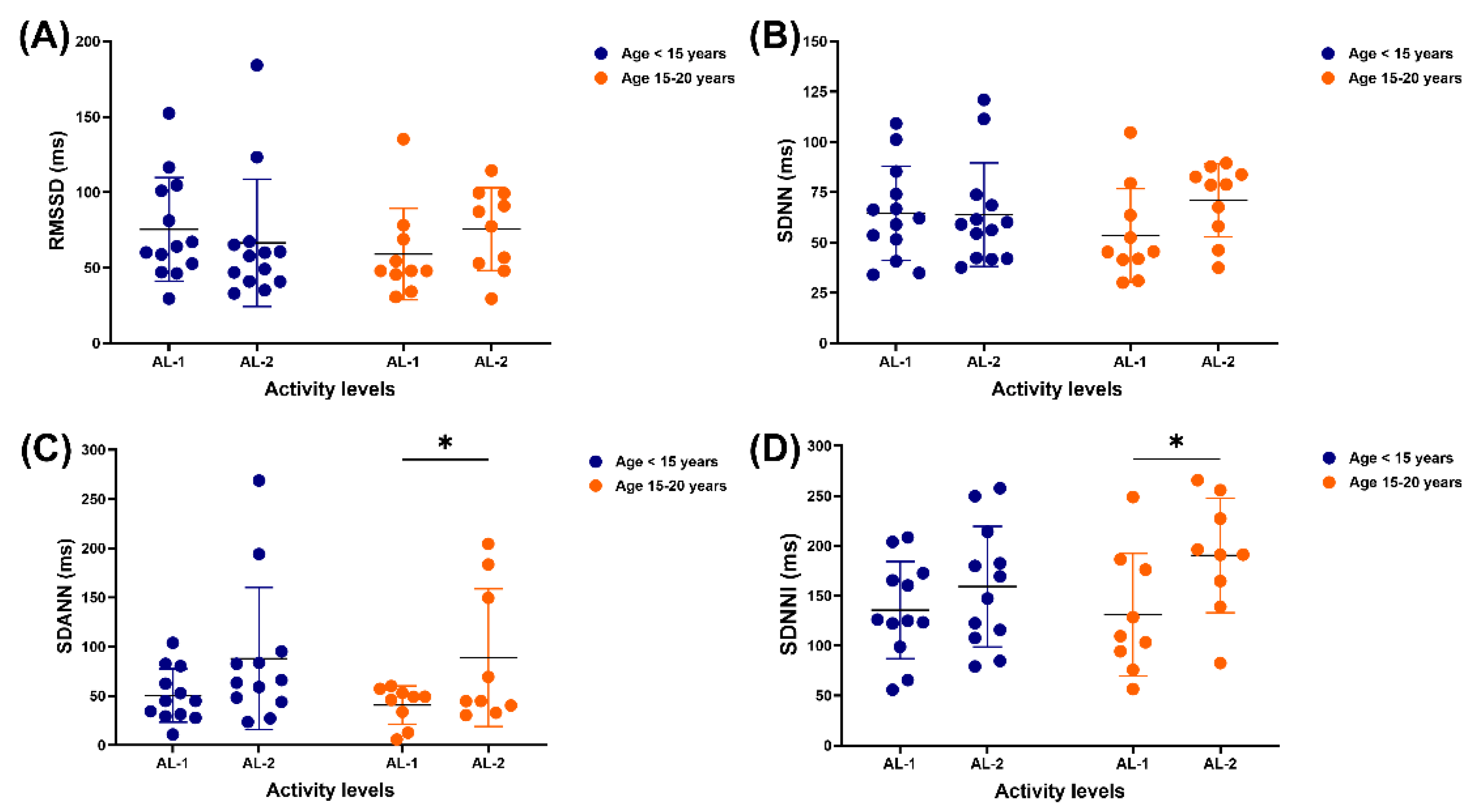

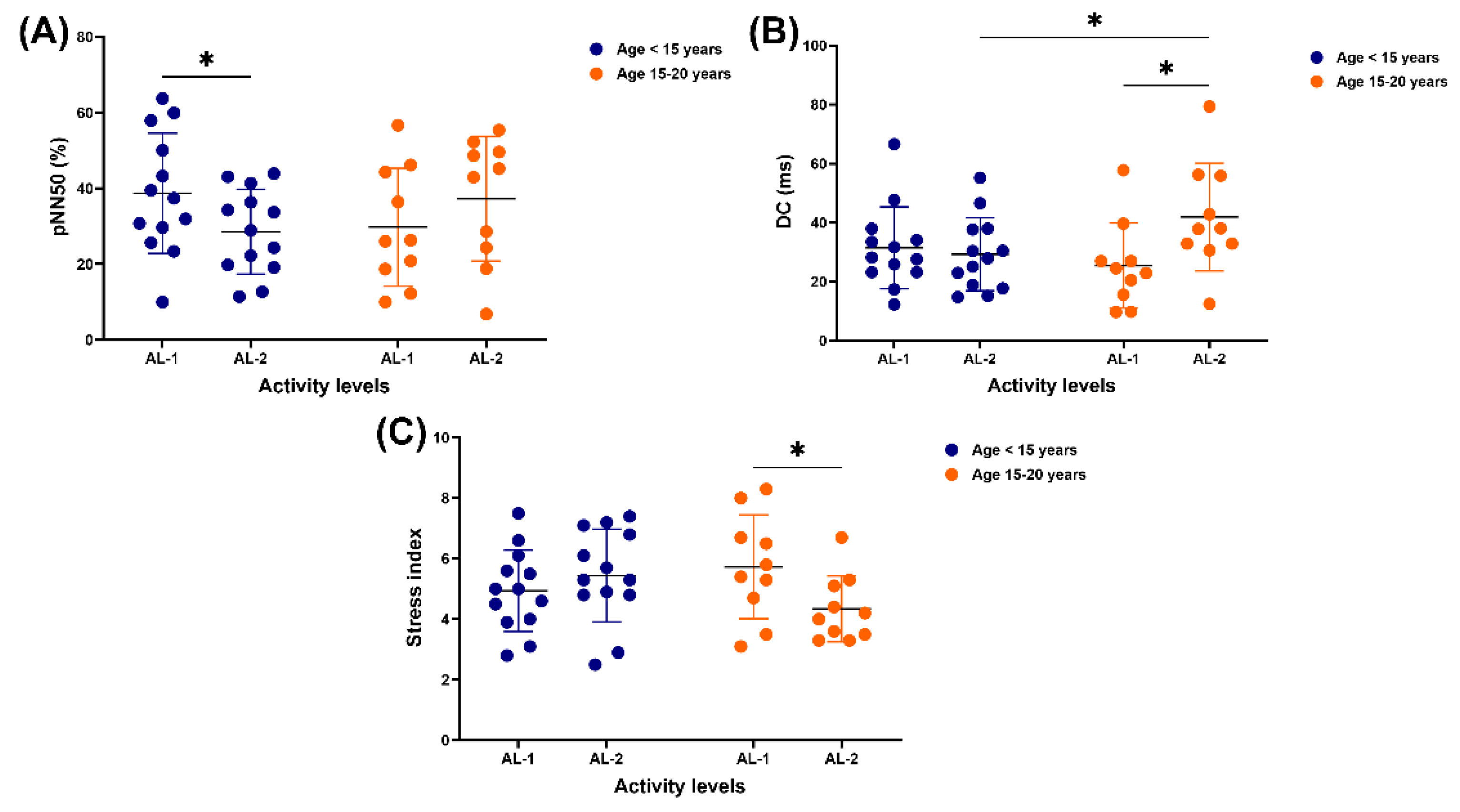

An independent effect of activity levels were found on the expression of mean HR (F (1, 21) = 5.376, p = 0.0306, ƞ2 = 0.10), mean RR (F (1, 21) = 4.643, p = 0.0429, ƞ2 = 0.08), SDANN (F (1, 19) = 8.158, p = 0.0101, ƞ2 = 0.15) and SDNNI (F (1, 19) = 4.947, p = 0.0385, ƞ2 = 0.12). Meanwhile, the interaction between age and activity level influenced the expression of pNN50 (F (1, 21) = 5.714, p = 0.0263, ƞ2 = 0.09), DC (F (1, 21) = 4.460, p = 0.0468, ƞ2 = 0.09) and stress index (F (1, 21) = 5.985, p = 0.0233, ƞ2 = 0.10). Neither independent nor interaction effects influenced RMSSD and SDNN reflections.

In horses under 15 years, mean HR was lower for those in the AL-1 group than in the AL-2 (37.1 ± 4.4 vs 42.2 ± 7.6 beats/min, p = 0.0428). However, no difference was observed in mean HR in horses between the ages of 15 and 20 years when performing AL-1 and AL-2 (

Figure 1a). Meanwhile, the mean RR was higher in horses younger than 15 years practising AL-1 compared to AL-2 (1633.9 ± 165.2 vs 1461.8 ± 215.5 ms, p = 0.0434). There was no variation in the mean RR in horses aged 15–20 years between AL-1 and AL-2 groups (

Figure 1B).

No variation was detected in the RMSSD and SDNN of horses in either age range when performing AL-1 and AL-2 (

Figure 2A,B). SDANN and SDNNI did not differ between AL-1 and AL-2 in horses aged less than 15 years; however, in older horses, both were lower in those practising AL-1 than AL-2 (SDANN: 40.8 ± 19.5 vs 88.9 ± 70.0 ms, p = 0.0471; SDNNI: 131.0 ± 61.4 vs 190.3 ± 57.3 ms, p = 0.0487) (

Figure 2C,D).

A difference in pNN50 was observed only in horses under 15 years old, with higher values in those practising AL-1 compared to AL-2 (38.7 ± 15.9 vs 28.6 ± 11.2 %, p = 0.0494) (

Figure 3A). Although DC showed no variation between AL-1 and AL-2 in younger horses, a higher value was observed in those 15–20 years old who practised AL-2 compared to those performing AL-1 (41.9 ± 18.2 vs 25.5 ± 14.4 ms, p = 0.0216) and younger horses performing AL-2 (41.9 ± 18.2 vs 29.3 ± 12.3 ms, p = 0.0469) (

Figure 3B). The stress index did not differ between AL-1 and AL-2 in horses under 15 years, but was higher in older horses in AL-1 than those involved in AL-2 (5.7 ± 1.7 vs 4.3 ± 1.1, p = 0.0267) (

Figure 3C).

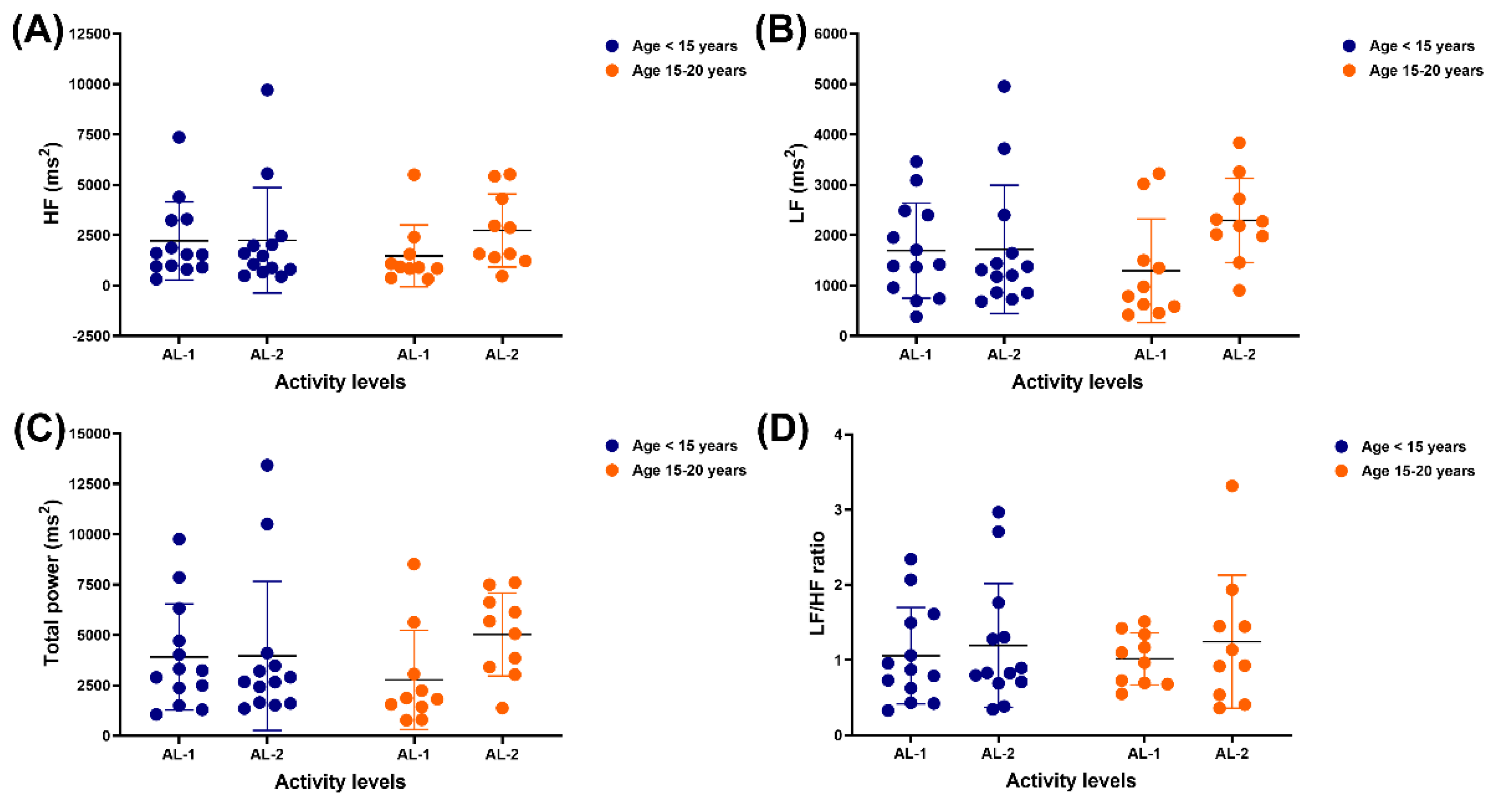

3.2. Frequency Domain Results

Neither independent nor interaction effects were observed in the HF, LF, or total band power, nor the LF/HF ratio. There was no variation in any frequency domain results, although the difference between AL-1 and AL-2 was almost significant in the LF band (p = 0.0513) and total power (p = 0.0969).

Figure 4.

HRV metrics HF band (A), LF band (B), total power band (C) and LF/HF ratio (D) in horses of different ages and activity levels. HRV: heart rate variability; HF: high-frequency; LF: low-frequency; AL: activity levels.

Figure 4.

HRV metrics HF band (A), LF band (B), total power band (C) and LF/HF ratio (D) in horses of different ages and activity levels. HRV: heart rate variability; HF: high-frequency; LF: low-frequency; AL: activity levels.

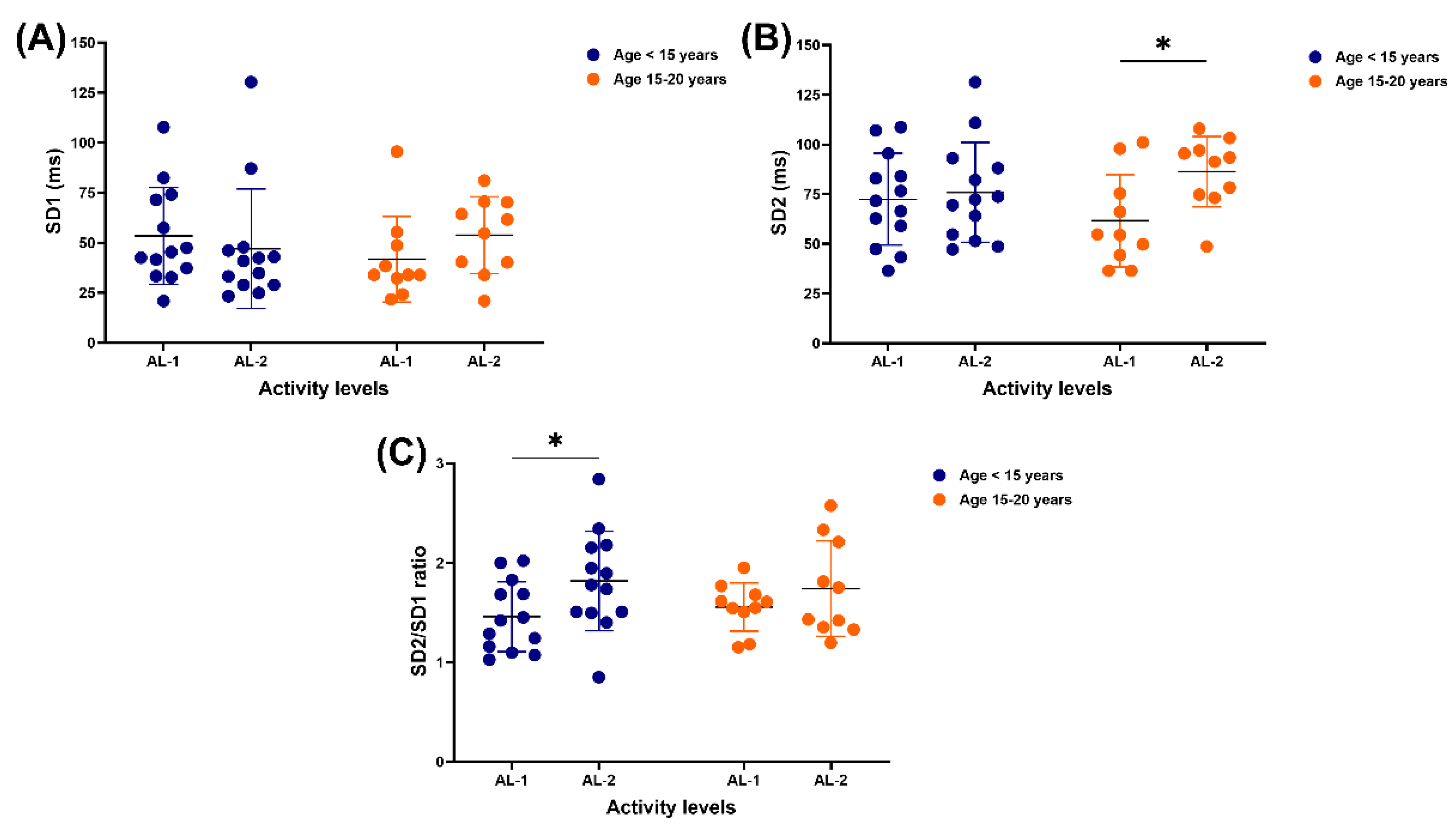

3.3. Nonlinear Results

Activity level independently impacted the expression of SD2 (F

(1, 21) = 4.353, p = 0.0493, ƞ

2 = 0.09) and the SD2/SD1 ratio (F

(1, 21) = 6.360, p = 0.0198, ƞ

2 = 0.10). No independent or interaction effects of age and activity level were detected on SD1, with no difference in either age group or activity level (

Figure 5A). There was no variation in SD2 between AL-1 and AL-2 in horses under 15 years, but this value was lower in older horses who performed AL-1 compared to AL-2 (61.6 ± 23.3 vs 86.3 ± 17.7 ms, p = 0.0241) (

Figure 5B). The SD2/SD1 ratio was lower in horses under 15 years who practised AL-1 than those involved in AL-2 (1.5 ± 0.4 vs 1.8 ± 0.5, p = 0.0200), while no variation between AL-1 and AL-2 in horses of 15–20 years (

Figure 5C).

4. Discussion

The present study explored how HRV metrics reflect autonomic responses in athletic horses of various ages engaged in typical riding club and equestrian sport activities at varying levels. The key findings of this study are as follows: 1. Interactions between the horses’ age and activity level significantly influenced HRV metrics, particularly pNN50, DC, and the stress index. Conversely, activity levels independently impacted the expression of mean HR, mean RR intervals, SDANN, SDNNI, SD2, and the SD2/SD1 ratio. 2. Horses younger than 15 exhibited lower HR and SD2/SD1 ratios, along with higher RR intervals and pNN50 while training for equestrian dressage, compared to those participating in school riding. 3. Horses aged 15 to 20 years demonstrated decreased SDANN, SDNNI, DC, and SD2, accompanied by an increased stress index during equestrian dressage training, relative to their counterparts participating in school riding. These findings indicate that HRV metrics in athletic horses vary based on age and activity level. Horses younger than 15 years displayed heightened HRV during structured training for equestrian sports, whereas those between 15 and 20 years exhibited elevated HRV metrics while engaged in school riding practices.

HRV metrics can be effectively evaluated using 4-, 6-, or 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) devices, considered the gold standard in any species [

15,

30]. However, the complex setup and the requirement for multiple optical cables attached to a horse’s body may cause discomfort during physical activity. As a result, HRM devices that detect RR intervals without recording full ECG have become popular for deriving HRV metrics. These devices offer several advantages, including a non-invasive method, ease of use, lower costs, and greater comfort for the horse compared to ECG devices [

27]. Several HRV metrics derived from HRM devices have been validated [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Despite these benefits, the presence of physiological 2-degree atrioventricular (AV) block—common in healthy horses—can lead to missed beats, causing intermittent prolongation of RR intervals and distortion of HRV results when using HRM devices [

31,

32]. To mitigate this issue, artefact filtering is necessary to correct for missing beats before conducting HRV analysis [

30]. In the current study, automatic artefact filtering was employed to correct or exclude artefacts such as missing beats, extra or misaligned beat detections, ectopic beats, and other arrhythmias. Additionally, the automatic noise detection feature provided by the Kubios program was utilised to remove noisy segments that could distort the detection of consecutive beats. The implementation of these algorithms aimed to enhance the accuracy of HRV analysis [

33]. Consequently, the HRV results from this study were thought to be reliable for identifying the autonomic responses in horses of varying ages and activity levels.

In the present study, HRV metrics varied among different groups of horses, influenced by age and activity levels. This finding was supported by the interaction observed between age and activity level on the expression of pNN50, DC, and the stress index, with a medium effect size. As expected, young horses undergoing structured dressage training displayed increased RR intervals and pNN50, indicating decreased HR and a lower SD/SD1 ratio. RR intervals are affected by both sympathetic and vagal activity, and elevated pNN50 signifies a dominance of vagal tone [

15,

17,

34]. A reduced SD2/SD1 ratio also indicates a shift towards vagal activity [

16,

17]. Our results, therefore, indicate that structured dressage training induced greater vagal activity in young horses compared to those engaged in a school riding regimen. In contrast, geriatric horses exhibited a decline in SDANN, SDNNI, DC, and SD2, associated with an increased stress index. This finding suggests lower HRV, reflecting reduced vagal tone in geriatric horses during structured dressage training compared to their counterparts involved in a school riding regimen. In human studies, measurements of DC, combined with acceleration capacity (AC) and heart rate fragmentation (HRF), have been predictive capability for cardiovascular disease [

35,

36]. Low DC and AC combined with high HRF correlate strongly with cardiovascular issues in patients [

35]. Based on this understanding, the decreased DC observed in geriatric horses may indicate adverse effects on cardiac function when they continue structured dressage training. Furthermore, the lower DC observed in young compared to geriatric horses participating in a school riding regimen may suggest negative impacts, even when young horses are only involved in basic riding activities. The current finding also provides objective evidence to support former anecdotal information from owners; the common perception is that nutrition, grooming, and pain avoidance are of great importance in older horses, while exercise is crucial in younger ones [

37]. Accordingly, the current results indicate that young horses are well-suited for structured training in equestrian sports. In contrast, due to the natural deterioration of bodily systems, geriatric horses are better suited to lower activity levels, such as those associated with school riding. Continuing their involvement in the high activity levels required for structured equestrian sport training may not be appropriate.

Notably, the SDNN measure did not differ between groups of similar ages. However, significant variations were observed in SDANN and SDNNI metrics between geriatric horses engaging in structured dressage training versus those involved in school riding. This finding aligns with previous reports from our group, which also showed significant differences in SDANN and SDNNI, but not in SDNN, among horses in similar conditions [

24,

38]. It is plausible that the RR intervals fluctuated transiently over the course of the 30-minute recording period, even while the horses were at rest. These fluctuations may have contributed to significant variation between the 5-minute segments in which estimates were calculated [

38]. Consequently, estimating HRV metrics over consecutive 5-minute intervals during a given period may be more sensitive and should be the preferred method for indicating HRV modulation, rather than longer recording periods. The expression of resting HR and autonomic responses varied among horses of different ages and activity levels in this study. However, there remains a gap in our understanding of how autonomic regulation manifests during exercise regimens, equestrian competitions, and recovery in horses under these conditions.

Several limitations of this experiment must be considered. While there was a structured timeline for the exercise training programs focused on equestrian dressage and school riding, the order of the exercises—such as trotting or cantering—was not standardised. This introduced variability dependent on the preferences of each horse’s trainer. Moreover, individual differences in behavioural and HRV parameters persist among horses [

39,

40,

41]. The experiment involved a large number of horses and included the recording of consecutive RR intervals and echocardiography. However, each horse unavoidably underwent examination at different times of the day. Circadian rhythm may also affect the expression of HRV metrics [

42,

43]. These factors could contribute to within-group variations when evaluating HRV metrics in this study. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution.

5. Conclusions

Horses under 15 years of age show a more positive autonomic response to training for equestrian sports compared to those engaged in a school riding regimen. In contrast, continuous training for equestrian sports in horses aged 15 to 20 years tends to result in reduced autonomic response when compared to the school riding regimen. Therefore, caution should be taken when continuing structured training for equestrian sports with horses older than 15 years, as it may compromise their welfare. This study provides valuable insights into the different autonomic responses of horses based on their age and activity levels. These findings have important implications for horse welfare, emphasising the need for careful management to ensure that horses participate in appropriate levels and types of physical activity to protect their well-being, especially for older horses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, T.W., C.P., S.P. and M.C.; methodology, T.W., C.P., S.P. and M.C.; software, T.W., C.P., K.S., S.P. and M.C.; validation, T.W., C.P., K.S., S.P. and M.C.; formal analysis, T.W., C.P., K.S., K.C., T.T., B.W., S.P. and M.C.; investigation, T.W., C.P., K.S., K.C., T.T., B.W., S.P. and M.C.; resources, C.P. and M.C.; data curation, T.W., C.P., K.S., K.C., T.T., B.W., S.P. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.W., C.P., K.S., S.P. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, S.P. and M.C.; visualisation, T.W., C.P., K.S., K.C., T.T., B.W., S.P. and M.C.; supervision, S.P. and M.C.; project administration, S.P. and M.C.; funding acquisition, C.P. and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Kasetsart Veterinary Development Funds, grant number VET.KU2025 – 02 and the APC was funded by the faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Kasetsart University Institute of Animal Care and Use Committee (ACKU68-VET-023; April 1, 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the owners of all horses involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Horseshoe Point Riding Academy for allowing us to conduct this research in the club. We greatly appreciate the professional skill in horse restraints and the invaluable assistance of duty grooms and responsible persons during the experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AL-1 |

Structured exercise programme for equestrian dressage practise three to five days/week |

| AL-2 |

School riding practice one or less than one day/week |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| CSV |

Comma-separated values |

| DC |

Deceleration capacity of heart rate computed as a four-point difference |

| HF |

High-frequency band |

| HR |

Heart rate |

| HRM |

Heart rate monitoring |

| HRV |

Heart rate variability |

| LF |

Low-frequency band |

| LSD |

Least significant difference |

| pNN50 |

Number of successive RR interval pairs that differ more than 50 ms divided by the total number of RR intervals |

| RMSSD |

Square root of the mean squared differences between successive RR intervals |

| RR |

Beat-to-beat |

| SDNN |

Standard deviation of normal-to-normal RR intervals |

| SDANN |

Standard deviation of the averages of normal-to-normal RR intervals in 5-min segments |

| SDNNI |

Mean of the standard deviations of normal-to-normal RR intervals in 5-min segments |

| SD1 |

Standard deviation in Poincaré plot perpendicular to the line-of-identity |

| SD2 |

Standard deviation in Poincaré plot along the line-of-identity |

References

- Internationale, F.E. the FEI Database. 2025. https://data.fei.org/default.aspx.

- McKeever, K.H.; Eaton, T.L.; Geiser, S.; Kearns, C.F.; Lehnhard, R.A. Age related decreases in thermoregulation and cardiovascular function in horses. Equine Vet. J. 2010, 42, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.; Arent, S.M.; McKeever, K.H. Maximal aerobic capacity (VO2max) in horses: a retrospective study to identify the age-related decline. Comp. Exerc. Physiol. 2009, 6, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-s.; Hinchcliff, K.W.; Yamaguchi, M.; Beard, L.A.; Markert, C.D.; Devor, S.T. Age-related changes in metabolic properties of equine skeletal muscle associated with muscle plasticity. Vet. J. 2005, 169, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, T.; Kikuchi, M.; Kurotaki, T.; Oyamada, T.; Yoshikawa, H.; Yoshikawa, T. Age-related changes in the testes of horses. Equine Vet. J. 2001, 33, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradis, M.R. Demographics of health and disease in the geriatric horse. Vet. Clin, Equine Pract. 2002, 18, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington McKeever, K. Aging and how it affects the physiological response to exercise in the horse. Clin. Tech., Equine Pract. 2003, 2, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-G.; Cheon, E.-J.; Bai, D.-S.; Lee, Y.H.; Koo, B.-H. Stress and Heart Rate Variability: A Meta-Analysis and Review of the Literature. Psychiatry Investig. 2018, 15, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J.F.; Åhs, F.; Fredrikson, M.; Sollers, J.J.; Wager, T.D. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012, 36, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiweck, C.; Piette, D.; Berckmans, D.; Claes, S.; Vrieze, E. Heart rate and high frequency heart rate variability during stress as biomarker for clinical depression. A systematic review. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, W.C.; Cerqueira, M.D.; Harp, G.D.; Johannessen, K.-A.; Abrass, I.B.; Schwartz, R.S.; Stratton, J.R. Effect of endurance exercise training on heart rate variability at rest in healthy young and older men. Am. J. Cardiol. 1998, 82, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietmann, T.R.; Stuart, A.E.A.; Bernasconi, P.; Stauffacher, M.; Auer, J.A.; Weishaupt, M.A. Assessment of mental stress in warmblood horses: heart rate variability in comparison to heart rate and selected behavioural parameters. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2004, 88, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlen, H.; Faust, M.-D.; Grzeskowiak, R.M.; Trachsel, D.S. Association between Disease Severity, Heart Rate Variability (HRV) and Serum Cortisol Concentrations in Horses with Acute Abdominal Pain. Animals 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.J.; Schwarzwald, C.C. Heart rate variability analysis in horses for the diagnosis of arrhythmias. Vet. J. 2021, 268, 105590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucke, D.; Große Ruse, M.; Lebelt, D. Measuring heart rate variability in horses to investigate the autonomic nervous system activity – Pros and cons of different methods. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 166, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Borell, E.; Langbein, J.; Després, G.; Hansen, S.; Leterrier, C.; Marchant, J.; Marchant-Forde, R.; Minero, M.; Mohr, E.; Prunier, A.; et al. Heart rate variability as a measure of autonomic regulation of cardiac activity for assessing stress and welfare in farm animals — A review. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An Overview of Heart Rate Variability Metrics and Norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, F.; McCraty, R.; Zerr, C.L. A healthy heart is not a metronome: an integrative review of the heart's anatomy and heart rate variability. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCraty, R.; Zayas, M.A. Cardiac coherence, self-regulation, autonomic stability, and psychosocial well-being. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Moneghetti, K.J.; Christle, J.W.; Hadley, D.; Froelicher, V.; Plews, D. Heart Rate Variability: An Old Metric with New Meaning in the Era of Using mHealth technologies for Health and Exercise Training Guidance. Part Two: Prognosis and Training. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. Rev. 2018, 7, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, H.; Jones, J.H. Changes in heart rate and heart rate variability as a function of age in Thoroughbred horses. Journal of Equine Science 2017, 28, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczarek, I.; Kędzierski, W.; Wilk, I.; Wnuk–Pawlak, E.; Rakowska, A. Comparison of daily heart rate variability in old and young horses: A preliminary study. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanigavatee, K.; Poochipakorn, C.; Huangsaksri, O.; Vichitkraivin, S.; Pakdeelikhit, S.; Chotiyothin, W.; Wongkosoljit, S.; Wonghanchao, T.; Chanda, M. A structured exercise regimen enhances autonomic function compared to unstructured physical activities in geriatric horses. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanigavatee, K.; Poochipakorn, C.; Huangsaksri, O.; Wonghanchao, T.; Rodkruta, N.; Chanprame, S.; wiwatwongwana, T.; Chanda, M. Comparison of daily heart rate and heart rate variability in trained and sedentary aged horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2024, 137, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frippiat, T.; van Beckhoven, C.; Moyse, E.; Art, T. Accuracy of a heart rate monitor for calculating heart rate variability parameters in exercising horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2021, 104, 103716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapteijn, C.M.; Frippiat, T.; van Beckhoven, C.; van Lith, H.A.; Endenburg, N.; Vermetten, E.; Rodenburg, T.B. Measuring heart rate variability using a heart rate monitor in horses (Equus caballus) during groundwork. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 939534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ille, N.; Erber, R.; Aurich, C.; Aurich, J. Comparison of heart rate and heart rate variability obtained by heart rate monitors and simultaneously recorded electrocardiogram signals in nonexercising horses. J. Vet. Behav. 2014, 9, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, R.; Dowell, F.; Evans, N. Use of the Polar V800 and Actiheart 5 heart rate monitors for the assessment of heart rate variability (HRV) in horses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 241, 105401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences; routledge: New York, 2013; p. 567. [Google Scholar]

- Electrophysiology, T.F.o.t.E.S.o.C.t.N.A.S.o.P. Heart Rate Variability. Circulation 1996, 93, 1043–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggensperger, B.H.; Schwarzwald, C.C. Influence of 2nd-degree AV blocks, ECG recording length, and recording time on heart rate variability analyses in horses. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2017, 19, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntson, G.G.; Stowell, J.R. ECG artifacts and heart period variability: Don't miss a beat! Psychophysiology 1998, 35, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipponen, J.A.; and Tarvainen, M.P. A robust algorithm for heart rate variability time series artefact correction using novel beat classification. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2019, 43, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyerges-Bohák, Z.; Kovács, L.; Povázsai, Á.; Hamar, E.; Póti, P.; Ladányi, M. Heart rate variability in horses with and without severe equine asthma. Equine Vet. J. 2025, 57, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Pichot, V.; Solelhac, G.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Haba-Rubio, J.; Vollenweider, P.; Waeber, G.; Preisig, M.; Barthélémy, J.-C.; Roche, F.; et al. Association between nocturnal heart rate variability and incident cardiovascular disease events: The HypnoLaus population-based study. Heart Rhythm 2022, 19, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takase, B. Role of Heart Rate Variability in Non-Invasive Electrophysiology: Prognostic Markers of Cardiovascular Disease. J. Arrhythm. 2010, 26, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, J.L.; Clegg, P.D.; McGowan, C.M.; Duncan, J.S.; McCall, S.; Platt, L.; Pinchbeck, G.L. Owners’ perceptions of quality of life in geriatric horses: a cross-sectional study. Animal Welfare 2011, 20, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonghanchao, T.; Sanigavatee, K.; Poochipakorn, C.; Huangsaksri, O.; Chanda, M. Dynamic Adaptation of Heart Rate and Autonomic Regulation During Training and Recovery Periods in Response to a 12-Week Structured Exercise Programme in Untrained Adult and Geriatric Horses. Animals 2025, 15, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez Manrique, L.; Hudson, R.; Bánszegi, O.; Szenczi, P. Individual differences in behavior and heart rate variability across the preweaning period in the domestic horse in response to an ecologically relevant stressor. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 210, 112652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.D.; Stephenson, M.; Preece, M.; Harris, P. A novel approach to systematically compare behavioural patterns between and within groups of horses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 161, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physick-Sheard, P.W.; Marlin, D.J.; Thornhill, R.; Schroter, R.C. Frequency domain analysis of heart rate variability in horses at rest and during exercise. Equine Vet. J. 2000, 32, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, M.; Hiraga, A.; Kai, M.; Tsubone, H.; Sugano, S. Influence of training on autonomic nervous function in horses: evaluation by power spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Equine Vet. J. 1999, 31, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, H.; Boscan, P.L.; Solano, A.M.; Stanley, S.D.; Jones, J.H. Changes in heart rate, heart rate variability, and atrioventricular block during withholding of food in Thoroughbreds. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2012, 73, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).