1. Introduction

Horses have been domesticated for human purposes such as transportation, agriculture and military use [

1]. Today, they are bred and trained for equestrian sports competitions, a global industry worth approximately 302 billion USD [

2]. Consequently, sports horses are often subjected to excessive training to meet the demands of the industry, leading to prolonged stressful conditions and potential injuries throughout their careers [

3,

4]. Importantly, the post-retirement fate of sports horses varies, with some facing abandonment, breeding, slaughter or euthanasia, depending on their circumstances [

3].

The concept of age can be divided into chronological, physiological and demographic ages [

5,

6]. Chronological age refers to the actual number of years lived, whereas physiological age relates to the functional capacity of the animal [

5]. On the other hand, demographic age refers to survivorship relative to a population [

5,

6]. Physiological age is particularly interesting because it varies among horses based on their genetics and environment. Although some horses may be considered old at 15 years, others may still be competing at 25 years of age [

6,

7]. After retiring from their athletic careers, some horses are retrained for less physically demanding activities, such as school riding. This not only preserves the welfare of the animals but also maintains the economic value of retired sports horses as they age [

3].

Physical training for horses aims to achieve several key goals, including enhancing or preserving optimal sports performance, delaying the onset of fatigue, reducing the risk of injury and maintaining the horse's willingness to exercise [

8,

9]. Specifically, aerobic training has a positive impact on biological systems, leading to improved cardiovascular function [

10,

11], a lower resting heart rate (HR) [

12,

13,

14,

15] and increased aerobic capacity of skeletal muscle [

16,

17,

18], in turn enhancing the horse's fitness level [

19]. Furthermore, exercise training modulates autonomic function, as evidenced by changes in HR variability (HRV) [

15,

20,

21,

22,

23]. HRV reflects the variability in beat-to-beat intervals under the influence of the sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal) components, demonstrating the adaptability and flexibility of biological systems in response to stressful challenges [

24,

25].

Modification of various HRV variables can reflect specific autonomic components. For example, changes in the standard deviation of normal-to-normal RR intervals (SDNN), low-frequency (LF) band, total power band and standard deviation of the Poincaré plot along the line of identity (SD2) are influenced by both sympathetic and vagal components [

24,

25]. Conversely, the root mean square of differences between successive RR intervals (RMSSD), relative number of successive RR interval pairs that differ by more than 50 ms (pNN50), high-frequency (HF) band and standard deviation of the Poincaré plot perpendicular to the line of identity (SD1) modulations reflect short-term variation at high-frequency power band and, thereby, predominant vagal activity [

24,

25,

26,

27]. A decrease in these variables indicates a reduced role of the vagal component [

20,

21,

28,

29,

30]. Although HRV decreases in horses, reflecting a shift toward sympathetic activity, while performing exercise [

20,

21,

31,

32], it demonstrates a shift toward more vagal activity after a period of aerobic training [

11,

15].

Importantly, ageing is not a disease but a condition in which the body experiences a decline in body mass, aerobic capacity, functional immunity and autonomic function with time [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Engaging in physical activity is essential for maintaining muscle mass and immunological function in aged and unfit horses [

38,

39]. Exercise training allows for enhancing oxidative capacity and mitochondrial function, as well as reducing microstructural damage to skeletal muscle in aged horses [

40]. Additionally, physical training leads to a decreased resting HR and a trend toward better autonomic responses in geriatric horses [

13,

41]. However, inappropriate physical training may pose a risk of significant injury, compromising the welfare of horses [

42].

Although the enhancement of autonomic regulation has been observed after structured training programmes in adult horses, the impact of such programmes on geriatric horses has not been fully explained. Hence, this study sought to examine the effects of a structured exercise regimen on HR and autonomic regulation in retired geriatric horses. The hypothesis was that the structured exercise regimen would significantly impact their HR and autonomic regulation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Horses

Twenty-seven mixed-breed geriatric horses from the Horse Lover’s Club in Pathum Thani, Thailand, were selected for this study. These horses had previously participated in equestrian sports and retired from competition around the age of 15 years. Following their retirement, they either lived sedentarily or continued with physical activities. They were housed in 4x4-m single-stalled boxes with straw bedding in central-aisle horse barns. The horses were provided with 2 kg of commercial pellets and 60–100 g of trace minerals three times a day and had free access to hanged pergola hay and tap water within their boxes. The inclusion criteria for the horses in this study were that (1) they did not receive medical or surgical treatments 30 days before or during the 12-week study period and (2) they passed a fundamental health check and gait inspection for exercise, particularly for horses who had retained physical activity and those who were assigned to practise the structured exercise regimen. Two horses who had retained physical activity were excluded from the study due to health problems early in the experiment. Thus, data were collected from only 25 horses.

2.2. Experimental protocol

The study involved three groups of horses assigned to different treatments. (1) The first group consisted of nine sedentary geriatric horses (seven geldings and two mares) with an average age of 23.4 ± 4.3 years and an average weight of 391.5 ± 77.1 kg. These horses were required to maintain a sedentary lifestyle (SEL), primarily living in single-stalled boxes and spending a few hours daily in the paddock. (2) The second group included seven geriatric horses (four geldings and three mares) with an average age of 18.8 ± 5.7 years and an average weight of 373.0 ± 99.6 kg. These horses engaged in unstructured physical activities, encompassing lunging, schooling, jumping and trail riding, for 20–30 minutes, three to four days a week (RAT). On non-exercise days, they spent a few hours in the paddock. (3) The third group comprised another nine sedentary geriatric horses (five geldings and four mares) with an average age of 20.8 ± 3.9 years and an average weight of 376.6 ± 41.3 kg. They were assigned to practise lunges following a structured exercise regimen, as described in

Table 1. The total period for the exercise regimen was 54 minutes, 3–4 days a week, for 12 consecutive weeks. Like the other groups, they spent a few hours in the paddock on non-exercise days.

2.3. Data Collection and Acquisition

The RR intervals were recorded biweekly to calculate HRV variables, providing insight into the autonomic regulation of the horses. The horses in this study were equipped with an HR monitoring (HRM) device from Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland. This user-friendly device has been validated for measuring HR and HRV [

43,

44,

45] and has been used for various purposes in horses [

44,

46,

47,

48,

49]. To ensure optimal signal transmission, the Polar equine belt for riding was moistened and ultrasound gel was applied to the electrode area. The HR sensor (H10) was then affixed to the dampened belt and secured to the horse’s chest, positioning the sensor pocket on the middle left side of the chest. The sensor was eventually wirelessly connected to the Polar sports watch (Vantage V3) and set to record the RR interval data of individuals for 30 minutes at rest periods of specific time points.

The sports watch was then linked to the Polar FlowSync program (

https://flow.polar.com/, accessed on 29 September 2024) to upload the RR interval data and export them as CSV files. These documents were used to compute the HRV variables via the Kubios premium software (Kubios HRV Scientific;

https://www.kubios.com/hrv-premium/) and reported as MATLAB MAT files. To ensure the aligned RR intervals, the automatic artefact correction was set to exclude missing, extra or misaligned beat detections and ectopic beats, such as premature ventricular contractions or other arrhythmias in the RR interval time series. The automatic noise detection was set at a medium level to exclude noise segments that distorted several consecutive beats, thereby affecting the accuracy of HRV analysis. Additionally, the smoothness priors method was used to remove RR interval time series nonstationarities. The cutoff frequency for trend removal was set at 0.035 Hz, as outlined by the user guideline (

https://www.kubios.com/downloads/Kubios_HRV_Users_Guide.pdf, accessed on 29 September 2024). The HRV variables were expressed in three domain methods, as shown in

Table 2, and reported at 2-week intervals for a consecutive 12 weeks.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.3.1 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Due to missing data on HRV analysis, the independent effects of group and time and the interaction effect of group-by-time on HR and HRV modulation were evaluated by the mixed-effects model (restricted maximum likelihood; REML) with Greenhouse–Geisser correction. Tukey’s post hoc test was implemented for within-group and between-group comparisons at specific times. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to verify the normal distribution of the data when necessary. Due to the normally distributed data, the ordinary one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons tests, was employed to estimate variations in the horses’ age and weight. The results were expressed as mean ± SD, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

No differences existed in average age (SEL: 23.4 ± 4.3 years vs RAT: 18.8 ± 5.7 years vs SER: 20.8 ± 3.9 years, p = 0.1340) or weight (SEL: 391.5 ± 77.1 kg vs RAT: 373.0 ± 99.6 kg vs SER: 376.6 ± 41.3 kg, p = 0.9271) between the groups of horses. The autonomic regulation was determined via three analysis methods as follows.

3.1. Time Domain Methods

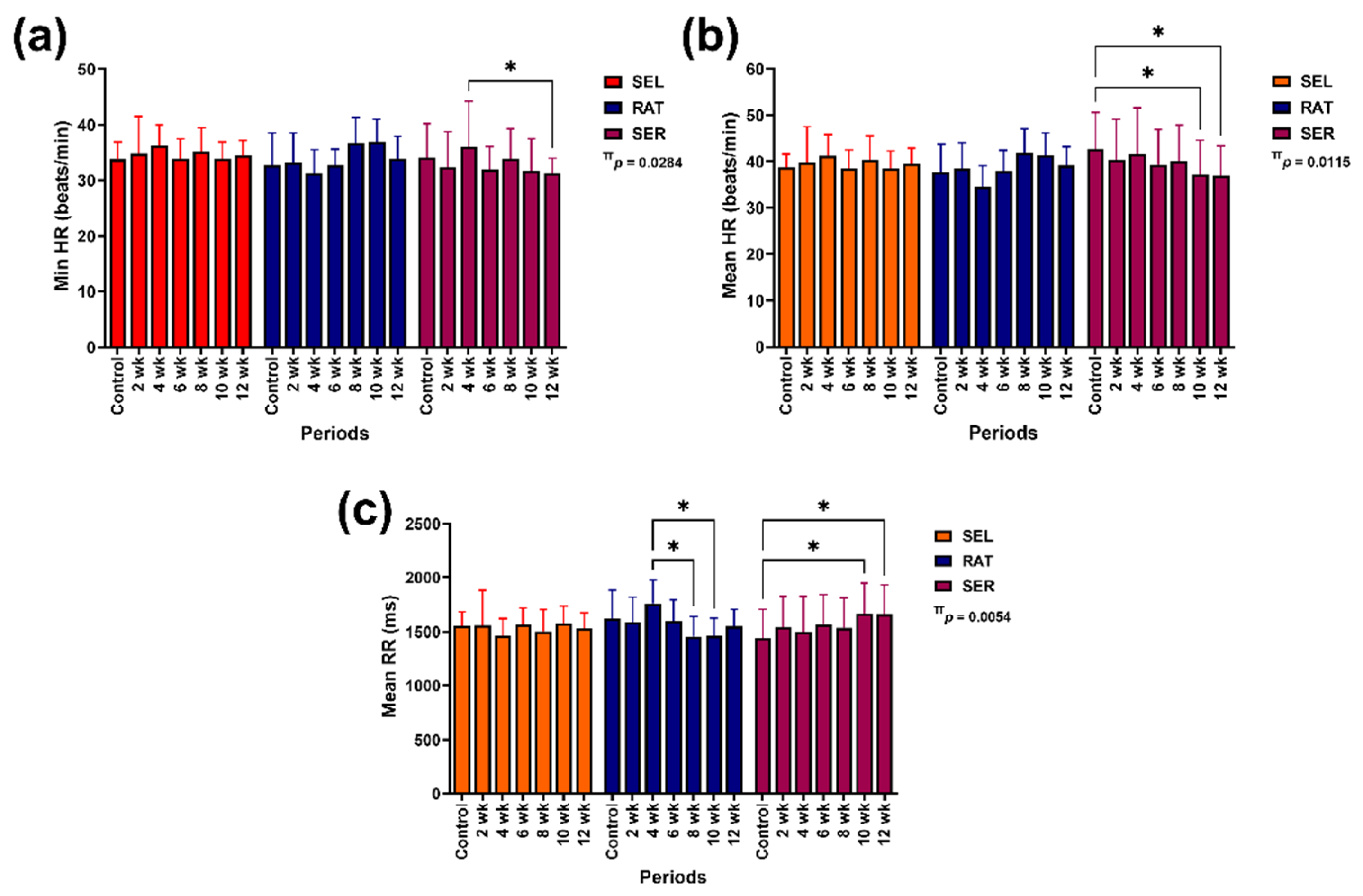

Group-by-time interaction was detected on changes in minimum HR (p = 0.0284), mean HR (p = 0.0115) and mean RR intervals (p = 0.0054;

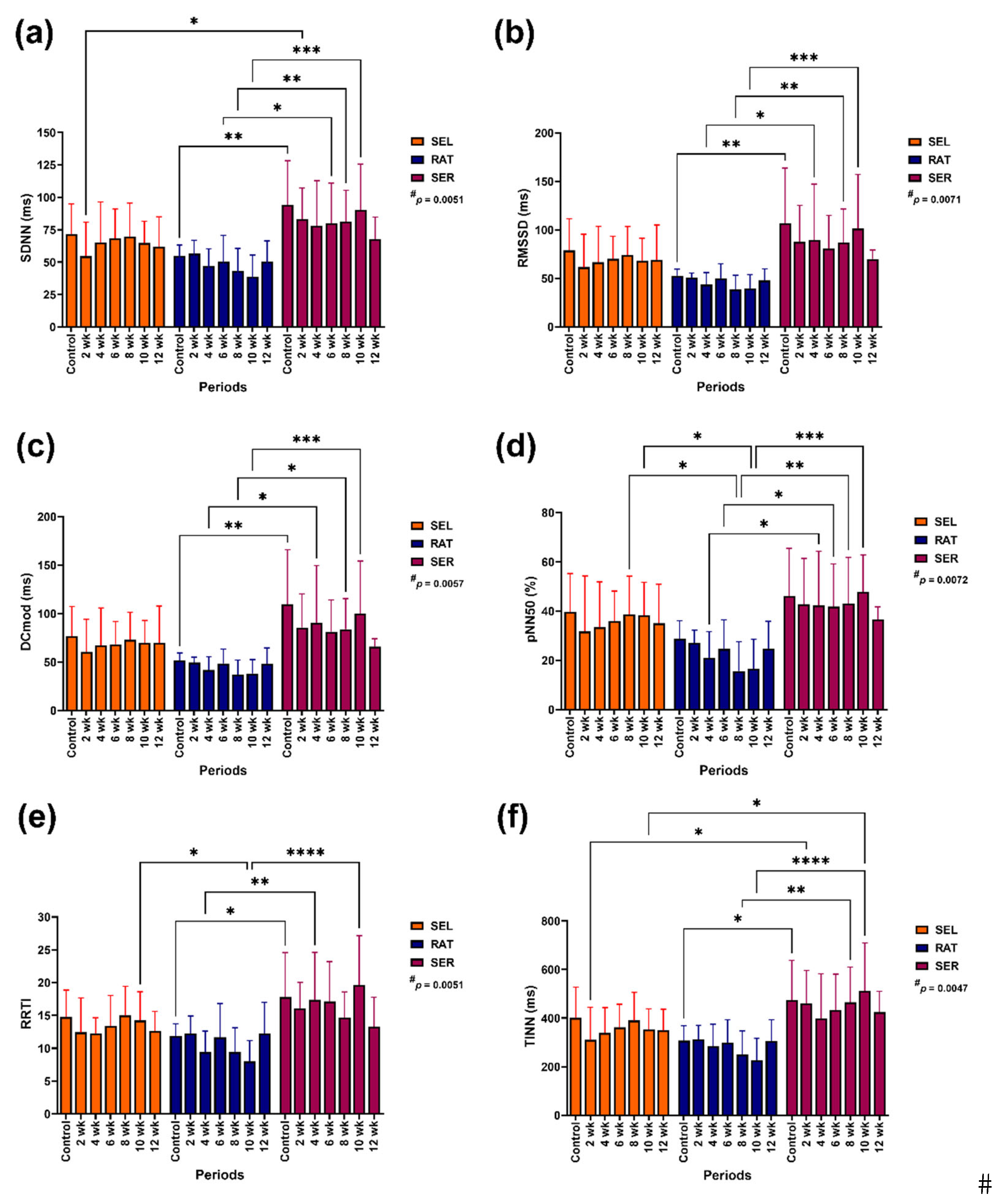

Figure 1). Independent group affected modification of SDNN (p = 0.0051), RMSSD (p = 0.0071), pNN50 (p = 0.0072), DCmod (p = 0.0057), TINN (p = 0.0047) and RRTI (p = 0.0051;

Figure 2).

Although the minimum and mean HR were unchanged in SEL and RAT horses, the minimum HR was reduced in SER horses at 10 (p = 0.0552) and 12 weeks (p < 0.05), compared to the values at 4 weeks (

Figure 1a). The mean HR also decreased in SER horses at 10 and 12 weeks, compared to the control (p < 0.05 for both time points;

Figure 1b). The mean RR intervals showed a temporal decrease in RAT horses at 8 and 10 weeks (p < 0.05 for both time points) but increased in SER horses at 10 and 12 weeks, compared to the control (p < 0.05 for both time points). No change was found in the mean RR intervals of SEL horses over the study period (

Figure 1c).

SDNN in SER horses was higher than in RAT horses before the study (control) at 6, 8 and 10 weeks of the study (p < 0.05–0.001) and higher than in SEL horses at 2 weeks of the study (p < 0.05;

Figure 1a). RMSSD and DCmod were higher in SER horses than RAT horses before the study (control) at 4, 8 and 10 weeks of the study (p < 0.05–0.001 for both variables;

Figure 2b,c). pNN50 and RRTI were higher in SER horses than in RAT horses at specific time points (pNN50: 4, 6, 8, 10 weeks of the study, p < 0.05–0.001; RRTI: control, 4 and 10 weeks of the study, p < 0.05–0.0001). pNN50 and RRTI in RAT horses were lower than in SEL horses at 8 and 10 weeks of the study (pNN50, p < 0.05 for both time points; RRTI: 8 weeks, p = 0.0541; 10 weeks, p < 0.05;

Figure 2d,e). Like the other variables, TINN was higher in SER horses than in RAT horses before the study (control) and at 8 and 10 weeks of the study (p < 0.05–0.0001). TINN in SER horses was also higher than in SEL horses at 2 and 10 weeks of the study (p < 0.05 for both time points;

Figure 2f).

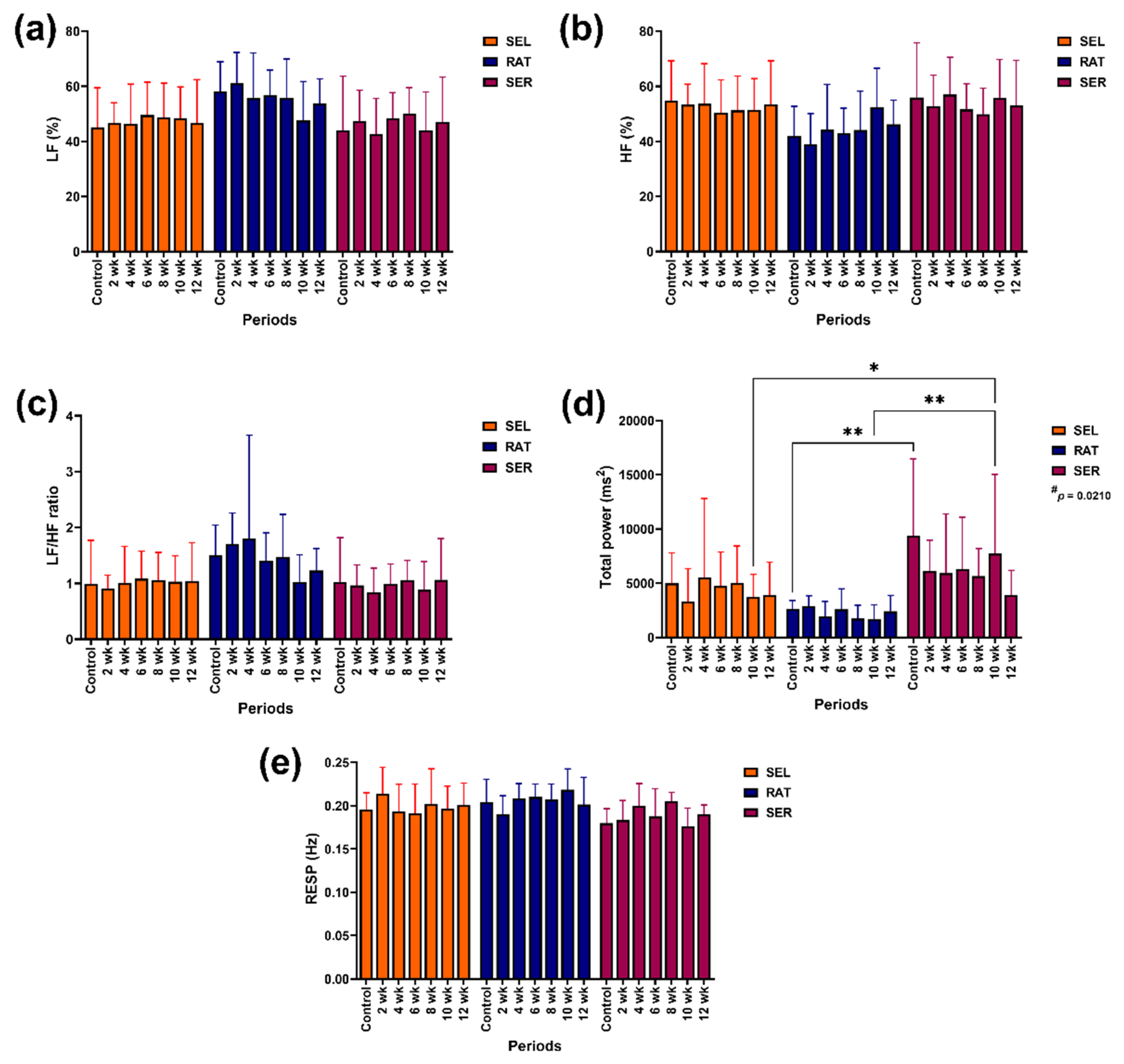

3.2. Frequency Domain Methods

Group-by-time interaction, independent group and independent time did not affect the contributions of HF band, LF band, LF/HF ratio or RESP, even though the independent group and group-by-time interaction were almost significant in LF/HF (p = 0.0770) ratio and RESP (p = 0.0593), respectively. However, the independent group effect influenced total power modulation (p = 0.0210;

Figure 3).

The contributions of LF band, HF band, LF/HF ratio and RESP did not differ within or between groups throughout the study. However, the total power in SER horses was higher than in RAT horses before the study (control) and at 10 weeks of the study (p < 0.01 for both time points) and higher than in SEL horses at 10 weeks of the study (p < 0.05;

Figure 3a–e).

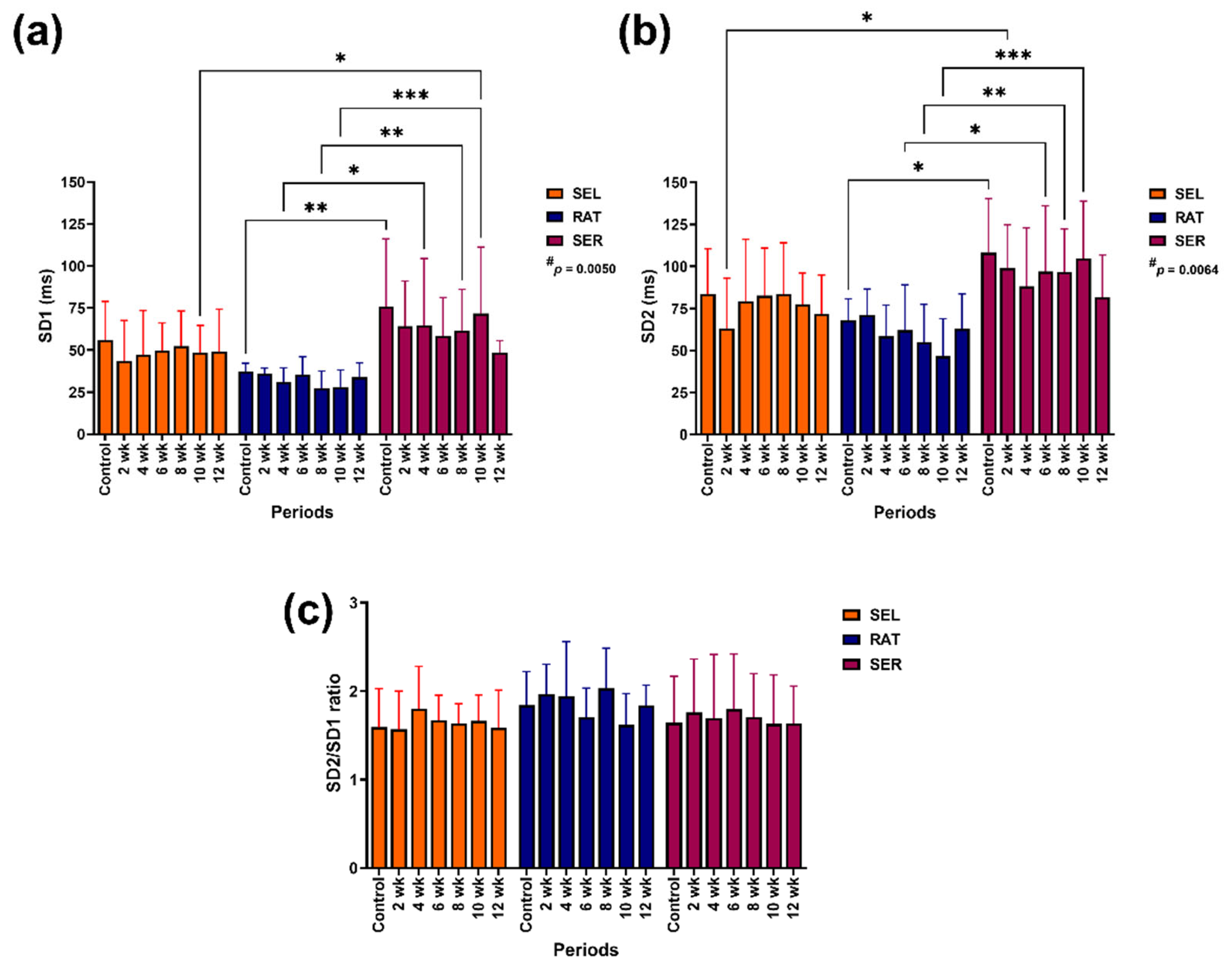

3.3. Nonlinear Methods

The independent group affected the modification of SD1 (p = 0.0050) and SD2 (p = 0.0064;

Figure 4). SD1 in SER horses was higher than in RAT horses before the study (control) at 4, 8 and 10 weeks of the study (p < 0.05–0.001), as well as in SEL horses at 10 weeks of the study (p < 0.05;

Figure 4a). SD2 in SER horses was also higher than in RAT horses before the study at 6, 8 and 10 weeks of the study (p < 0.05–0.001) and in SEF horses at 2 weeks of the study (p < 0.05;

Figure 4b). The SD2/SD1 ratio did not change over the study period (

Figure 4c).

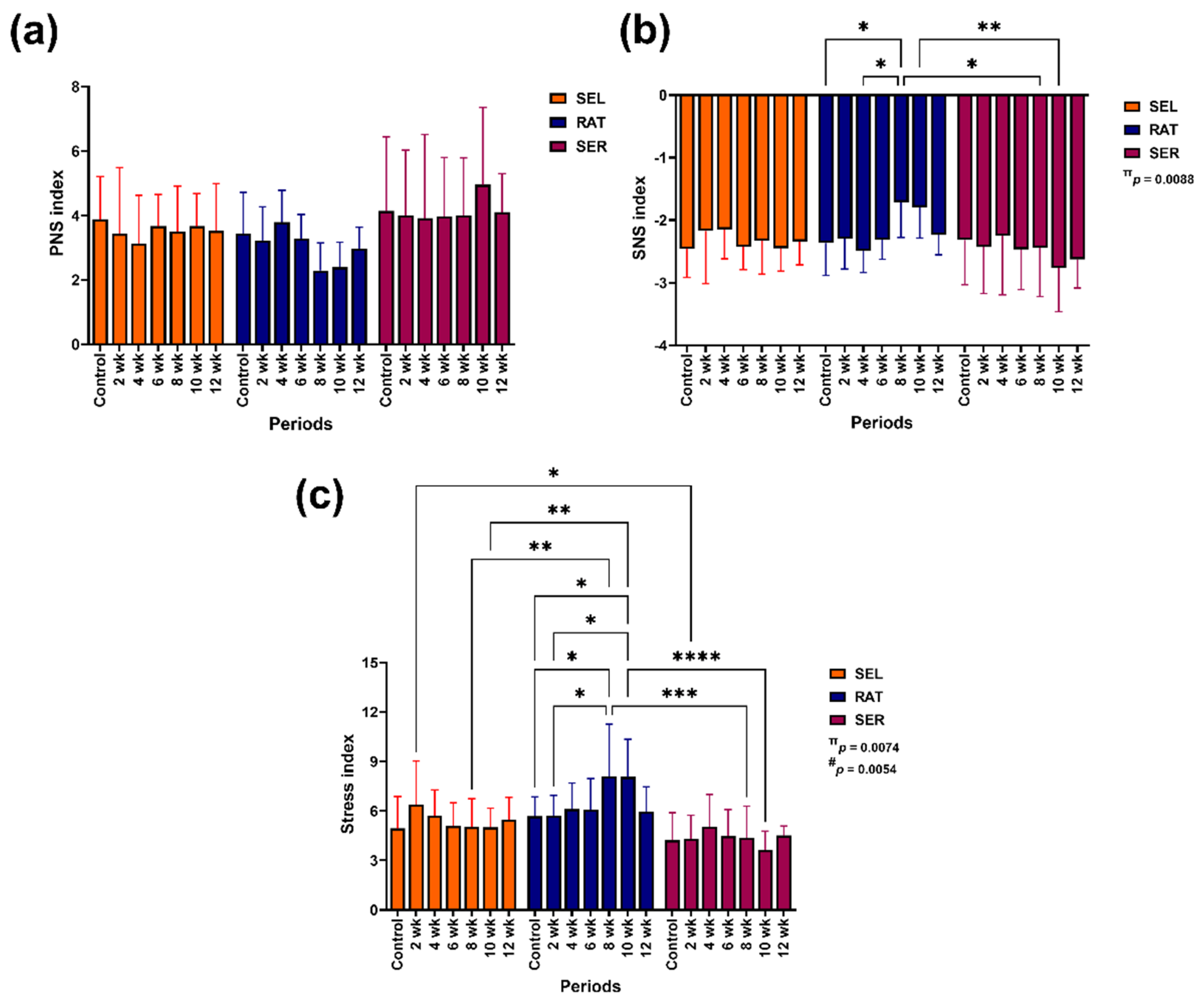

3.4. Autonomic Nervous System Index

The effect of group-by-time interaction impacted modulation of the SNS index (p = 0.0088), whereas group-by-time interaction (p = 0.0074) and independent group (p = 0.0054) affected modification of the stress index (

Figure 5).

The PNS index remained unchanged throughout the study (

Figure 5a). The SNS index was lower in SER horses than in RAT horses at 8 and 10 weeks of the study (p < 0.05 for both time points). The SNS in RAT horses increased at 8 weeks compared to the control (p < 0.05;

Figure 5b). The stress index in SER horses was lower than in RAT horses at 8 and 10 weeks of the study (p < 0.001–0.0001) and in SEL horses at 2 weeks of the study (p < 0.05). The stress index in RAT horses increased at 8 and 10 weeks (p < 0.05 for both time points) and showed higher values than in SEL horses for these periods (p < 0.01 for both time points;

Figure 5c).

4. Discussion

This study examined the HR and autonomic regulation responses to different physical modalities in geriatric horses. It revealed some significant findings. (1) A decrease in minimum and mean HR, corresponding to increased RR intervals, was only observed in SER horses. (2) Various HRV variables (SDNN, RMSSD, DCmod, pNN50, RRTI, TINN, total power, SD1 and SD2) were higher in SER horses compared to RAT horses. (3) Some HRV variables in SER horses (SDNN, TINN, total power, SD1 and SD2) were also higher than in SEL horses. (4) The SNS index was lower in SER horses compared to RAT horses. (5) The stress index in SER horses was lower than in RAT horses or, to a lesser extent, SEL horses. These results suggest that horses engaged in structured exercise regimens exhibit reduced resting HR and greater autonomic regulation compared to those with unstructured activities and sedentary lifestyles.

The horses in this study participated in a well-regimented exercise programme at a low-to-moderate intensity. This was evidenced by the average HR fluctuations during each exercise session, which ranged from 119.4 ± 29.6 to 150.7 ± 28.8 beats per minute, corresponding to 54.3 ± 13.5–68.5 ± 13.1% of the maximum HR based on a reference maximum of 220 beats per minute in ponies [

50,

51] (

Table S1). Comparing the exercise intensity in humans and horses [

52,

53] confirmed that the horses adhered to a structured exercise routine at a low-to-moderate intensity. Notably, resting HR decreased in geriatric horses as a result of the structured exercise programme. This aligns with previous literature reporting a reduced resting HR after aerobic training in both young and old horses [

12,

13,

14]. However, the resting HR remained unchanged, indicating no positive effect of physical activity on horses engaging in unstructured physical activities or those with sedentary lifestyles. Since a decreased resting HR indicates improved fitness levels in horses undergoing aerobic training [

14,

54,

55], aged horses engaged in the structured exercise regimen demonstrated superior physical fitness compared to those engaging in unstructured physical activities or leading a sedentary lifestyle.

The modulation of HR is influenced by the interplay between sympathetic and vagal activities [

24]. Changes in HR can be attributed to independent or synchronous activities of the two autonomic components. For example, a decreased HR can be the result of increased vagal activity, decreased sympathetic activity or combined changes in both components [

24,

25]. Therefore, using HR alone to indicate the separate effects of both autonomic components is unsuitable [

25,

26]. To address this limitation, HRV is often used to reflect the independent impact of sympathetic and vagal impulses. In this study, increased RR intervals were observed only in the SER horses, corresponding to a decreased mean HR. Since RR intervals are modulated under the influence of both sympathetic and vagal components [

24,

25], we assumed that a combination of sympathovagal activity led to changes in RR intervals and mean HR in the horses following the structured exercise regimen.

Various HRV variables were found to be higher in SER horses compared to RAT horses. These variables comprised SDNN, RMSSD, DCmod, pNN50, TINN, RRTI, total power band, SD1 and SD2. RMSSD, pNN50 and SD1 reflect short-term variations in HR due to predominant vagal activity, whereas sympathetic and vagal components affect modulations of SDNN, TINN, RRTI, total power and SD2, reflecting overall HRV [

24,

25,

26]. The results suggest that horses following the structured exercise regimen generated more vagal activity than those engaged in unstructured physical activity. DCmod is a deceleration capacity of HR, computed as a two-point difference for indicating vagal modulation [

56,

57]. It has been used in predicting congestive heart failure and mortality after myocardial infarction in elderly patients [

56,

58,

59]. The DCmod in this study appeared to be higher in SER horses than in RAT horses, suggesting that aged horses engaged in structured exercise may be predisposed to a lower risk of age-related cardiac disease compared to those performing unstructured physical activity. Furthermore, the SER horses exhibited higher SDNN, RRTI, TINN, total power band, SD1 and SD2, reflecting higher HR variations than SEL horses. Additionally, the stress index was temporally lower in SER horses than in SEL and RAT horses at 2 and 8–10 weeks of the experiment. These results support the idea that horses practising the structured exercise regimen displayed improved autonomic function, leading to lower stress than those performing unstructured physical activity and, to a lesser extent, those leading sedentary lifestyles. Notably, the lower pNN50 in RAT horses than in SEL and SER horses may support, in part, evidence of the detrimental effect of unstructured physical activity in aged horses.

The HRV variables differed between the groups, but no variation was observed within each group. Previous reports have suggested that the vagal component may be fully activated during the resting period in horses [

14,

60]. Since the HRV in our study was assessed during the resting state, the vagal activity may have been saturated, leading to consistent HRV variables across the study period. For the SER horses, the mean HR decreased after the structured exercise regimen despite no change in vagal activity. Additionally, with no variation in the PNS index, the SNS index was lower in SER horses compared to RAT horses. These findings suggest a gradual reduction in the role of the sympathetic component in response to a structured exercise regimen, resulting in a decreased resting HR in aged horses, consistent with previous reports [

14,

41].

The baseline HRV variables in the SER and RAT horses closely resembled those in SEL horses at the start of the study. However, biases may exist when including retired-aged horses who have led a sedentary lifestyle, whether they were introduced to a structured exercise programme or continuing their sedentary routine. For the 12-week structured training, sedentary aged horses with the potential to complete the exercise regimen (e.g. acceptable body condition score, appropriate hoof and limb conformation, and familiarity with lunging protocol) were primarily chosen for the SER group. This selection criterion could mean slightly higher HRV variable values in the SER group compared to the SEL group. Importantly, unlike the aged horses in the other groups, the horses in the RAT group were consistently engaged in unstructured physical activities before the study. This may have predisposed them to experience chronic stress, resulting in HRV variables slightly lower than the SEL horses but significantly lower than the SER horses at the beginning of the study (

Table S2). Although the structured exercise regimen showed the potential to maintain autonomic responses, the impact of this exercise regimen on muscular adaptation and related enzymatic functions in geriatric horses requires further investigation.

The study faced a challenge due to the limited number of healthy geriatric horses available, especially for those who performed the physical activity or structured exercise regimen. This resulted in a small sample size for all study groups. This is the primary limitation of the study. Additionally, the inclusion of horses of different sexes and individual characteristics may have contributed to variations in autonomic responses within each group. Furthermore, the varying levels of physical fitness among the horses in the second group likely led to differing autonomic responses while performing unstructured activities. Therefore, the study results concerning autonomic regulation must be interpreted with caution.

5. Conclusions

Geriatric horses participating in a structured exercise programme showed improvements in both physical fitness and autonomic regulation compared to those with unstructured activities or a sedentary lifestyle. Conversely, aged horses engaging in unstructured physical activity demonstrated potentially negative effects. These findings provide valuable insights into how different activity levels affect autonomic regulation in retired geriatric horses. The study has significant welfare implications, suggesting the need for management practices to enhance well-being, maintain welfare and, to some extent, preserve the economic value of geriatric horses after retirement.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27233970.

Table S1: Percentage of maximum heart rate (%HRmax) indicating effort intensity in geriatric horses practising structured exercise regimen;

Table S2: HRV variables in aged horses living sedentarily (SEL), retaining unstructured physical activity (RAT) and practising the structured exercise regimen (SER) at the onset of the study (control).

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, K.S., C.P., T.W. and M.C.; methodology, K.S., C.P., O.H., S.V., S.P., W.C., S.W., T.W. and M.C.; software, K.S., C.P., T.W. and M.C; validation, formal analysis and investigation, K.S., C.P., O.H., S.V., S.P., W.C., S.W., T.W. and M.C.; resources, K.S., C.P., T.W. and M.C; data curation, K.S., C.P., O.H., T.W. and M.C; writing—original draft preparation, K.S., T.W. and M.C; writing—review and editing, T.W. and M.C; visualisation, K.S., C.P., T.W. and M.C.; supervision, T.W. and M.C.; project administration, T.W. and M.C.; funding acquisition, T.W. and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Council of Thailand (contact nos. N41A661096 and N41A650067) and the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University (VET.KU2024-03 and VET.KU2024-05). The APC was funded by the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Kasetsart University (ACKU65-VET-005; 27/01/2022 and ACKU66-VET-089; 12/12/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the owners of all horses involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend our gratitude to Vaewratt Kamonkon, director of the Horse Lover’s Club, for allocating their horses for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript or the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bokonyi, S. History of horse domestication. Anim. Genet. Resour. Inf. 1987, 6, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fédération Équestre Internationale. Global Equestrian – Research. Available online: https://inside.fei.org/system/files/FEI%20Global%20Market%20Research%20Report_NF%20Version.pdf (accessed on 12/09/2024).

- Holmes, T.Q.; Brown, A.F. Champing at the bit for improvements: A review of equine welfare in equestrian sports in the United Kingdom. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, G.D. Gastrointestinal diseases of performance horses. In Equine sports medicine and surgery: basic and clinical sciences of the equine athlete, Hinchcliff, K.W., Kaneps, A., Geor, R. J., Ed.; 2004; pp. 1037–1043.

- Timiras, P.S. Definition: demographic, comparative and differential aging. In Physiological basis of aging and geriatrics, Timiras, P.S., Ed.; Macmillan Publishing Company: New York, 1988; pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, M.R. Demographics of health and disease in the geriatric horse. Vet. Clin. North Am. Equine Pract. 2002, 18, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, G. Nutritional and managerial considerations of the aged equine. Proceedings of Advanced Equine Management Short Course, Colorado State University. Fort Collins (CO): Colorado State University 1989, 121–123.

- Marlin, D.; Nankervis, K.J. Equine exercise physiology; Blackwell Science Ltd: UK, 2002; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero, J.-L.L.; Ruz, A.; Martí-Korff, S.; Estepa, J.-C.; Aguilera-Tejero, E.; Werkman, J.; Sobotta, M.; Lindner, A. Effects of intensity and duration of exercise on muscular responses to training of thoroughbred racehorses. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007, 102, 1871–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.L.; Rose, R.J. Cardiovascular and respiratory responses to submaximal exercise training in the thoroughbred horse. Pflügers Archiv 1988, 411, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, R.F.; Teixeira, M.S.; Perez, F.P.; Gulart, L.S. Effect of lunging exercise program with Pessoa training aid on cardiac physical conditioning predictors in adult horses. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2023, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottin, F.; Médigue, C.; Lopes, P.; Petit, E.; Papelier, Y.; Billat, V.L. Effect of exercise intensity and repetition on heart rate variability during training in elite trotting horse. Int. J. Sports Med. 2005, 26, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betros, C.L.; McKeever, N.M.; Manso Filho, H.C.; Malinowski, K.; McKeever, K.H. Effect of training on intrinsic and resting heart rate and plasma volume in young and old horses. Comp. Exerc. Physiol. 2013, 9, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, M.; Hiraga, A.; Kai, M.; Tsubone, H.; Sugano, S. Influence of training on autonomic nervous function in horses: evaluation by power spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Equine Vet. J. 1999, 31, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, C.S.; Silva, A.S.B.A.; Santos, C.M.R.; Santos, A.M.R.; Vintem, C.M.B.L.; Leite, A.G.; Fonseca, J.M.C.; Prazeres, J.M.C.S.; Souza, V.R.C.; Siqueira, R.F.; et al. Training effects on the stress predictors for young Lusitano horses used in dressage. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Votion, D.-M.; Gnaiger, E.; Lemieux, H.; Mouithys-Mickalad, A.; Serteyn, D. Physical fitness and mitochondrial respiratory capacity in horse skeletal muscle. PLoS One 2012, 7, e34890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietbroek, N.J.; Dingboom, E.G.; Schuurman, S.O.; Hengeveld-van der Wiel, E.; Eizema, K.; Everts, M.E. Effect of exercise on development of capillary supply and oxidative capacity in skeletal muscle of horses. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2007, 68, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Votion, D.M.; Fraipont, A.; Goachet, A.G.; Robert, C.; Van Erck, E.; Amory, H.; Ceusters, J.; De La RebiÈRe de Pouyade, G.; Franck, T.; Mouithys-Mickalad, A.; et al. Alterations in mitochondrial respiratory function in response to endurance training and endurance racing. Equine Vet. J. 2010, 42, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Thiers, P.M.; Bowen, L.K. Improved ability to maintain fitness in horses during large pasture turnout. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2013, 33, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangsaksri, O.; Sanigavatee, K.; Poochipakorn, C.; Wonghanchao, T.; Yalong, M.; Thongcham, K.; Srirattanamongkol, C.; Pornkittiwattanakul, S.; Sittiananwong, T.; Ithisariyanont, B.; et al. Physiological stress responses in horses participating in novice endurance rides. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanigavatee, K.; Poochipakorn, C.; Huangsaksri, O.; Wonghanchao, T.; Yalong, M.; Poungpuk, K.; Thanaudom, K.; Chanda, M. Hematological and physiological responses in polo ponies with different field-play positions during low-goal polo matches. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0303092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Lewinski, M.; Biau, S.; Erber, R.; Ille, N.; Aurich, J.; Faure, J.-M.; Möstl, E.; Aurich, C. Cortisol release, heart rate and heart rate variability in the horse and its rider: Different responses to training and performance. Vet. J. 2013, 197, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabó, C.; Vizesi, Z.; Vincze, A. Heart rate and heart rate variability of amateur show jumping horses competing on different levels. Animals 2021, 11, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Borell, E.; Langbein, J.; Després, G.; Hansen, S.; Leterrier, C.; Marchant-Forde, J.; Marchant-Forde, R.; Minero, M.; Mohr, E.; Prunier, A. Heart rate variability as a measure of autonomic regulation of cardiac activity for assessing stress and welfare in farm animals—A review. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucke, D.; Große Ruse, M.; Lebelt, D. Measuring heart rate variability in horses to investigate the autonomic nervous system activity – Pros and cons of different methods. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 166, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, F.; Ginsberg, J.P. An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms. Front. Public Health 2017, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourot, L.; Bouhaddi, M.; Perrey, S.; Rouillon, J.-D.; Regnard, J. Quantitative Poincaré plot analysis of heart rate variability: Effect of endurance training. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004, 91, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizaka, S.; Aurich, J.E.; Ille, N.; Aurich, C.; Nagel, C. Acute physiological stress response of horses to different potential short-term stressors. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2017, 54, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Birck, M.; Schmidt, A.; Lasarzik, J.; Aurich, J.; Möstl, E.; Aurich, C. Cortisol release and heart rate variability in sport horses participating in equestrian competitions. J. Vet. Behav. 2013, 8, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyerges-Bohák, Z.; Kovács, L.; Povázsai, Á.; Hamar, E.; Póti, P.; Ladányi, M. Heart rate variability in horses with and without severe equine asthma. Equine Vet. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottin, F.; Barrey, E.; Lopes, P.; Billat, V. Effect of repeated exercise and recovery on heart rate variability in elite trotting horses during high intensity interval training. Equine Vet. J. 2006, 38, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, M.; Robert, C.; Barrey, E.; Cottin, F. Effects of age, exercise duration, and test conditions on heart rate variability in young endurance horses. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.A.; LaVigne, E.K.; Jones, A.K.; Patterson, D.F.; Schauer, A.L. Horse species symposium: The aging horse: Effects of inflammation on muscle satellite cells. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington McKeever, K. Aging and how it affects the physiological response to exercise in the horse. Clin. Tech. Equine Pract. 2003, 2, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baragli, P.; Vitale, V.; Banti, L.; Sighieri, C. Effect of aging on behavioural and physiological responses to a stressful stimulus in horses (Equus caballus). Behaviour 2014, 151, 1513–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horohov, D.W.; Dimock, A.; Guirnalda, P.; Folsom, R.W.; McKeever, K.H.; Malinowski, K. Effect of exercise on the immune response of young and old horses. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1999, 60, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betros, C.L.; McKeever, K.H.; Kearns, C.F.; Malinowski, K. Effects of ageing and training on maximal heart rate and V̇O2max. Equine Vet. J. 2002, 34, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeever, K.H. Exercise and rehabilitation of older horses. Vet. Clin. North Am. Equine Pract. 2016, 32, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keadle, T.L.; Pourciau, S.S.; Melrose, P.A.; Kammerling, S.G.; Horohov, D.W. Acute exercises stress modulates immune function in unfit horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 1993, 13, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-s.; Hinchcliff, K.W.; Yamaguchi, M.; Beard, L.A.; Markert, C.D.; Devor, S.T. Exercise training increases oxidative capacity and attenuates exercise-induced ultrastructural damage in skeletal muscle of aged horses. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 98, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanigavatee, K.; Poochipakorn, C.; Huangsaksri, O.; Wonghanchao, T.; Rodkruta, N.; Chanprame, S.; Wiwatwongwana, T.; Chanda, M. Comparison of daily heart rate and heart rate variability in trained and sedentary aged horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2024, 137, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waran, N.; McGreevy, P.; Casey, R.A. Training methods and horse welfare. In The welfare of horses, Waran, N., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2007; pp. 194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Frippiat, T.; van Beckhoven, C.; Moyse, E.; Art, T. Accuracy of a heart rate monitor for calculating heart rate variability parameters in exercising horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2021, 104, 103716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapteijn, C.M.; Frippiat, T.; van Beckhoven, C.; van Lith, H.A.; Endenburg, N.; Vermetten, E.; Rodenburg, T.B. Measuring heart rate variability using a heart rate monitor in horses (Equus caballus) during groundwork. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 939534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ille, N.; Erber, R.; Aurich, C.; Aurich, J. Comparison of heart rate and heart rate variability obtained by heart rate monitors and simultaneously recorded electrocardiogram signals in nonexercising horses. J. Vet. Behav. 2014, 9, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangsaksri, O.; Sanigavatee, K.; Poochipakorn, C.; Wonghanchao, T.; Yalong, M.; Thongcham, K.; Srirattanamongkol, C.; Pornkittiwattanakul, S.; Sittiananwong, T.; Ithisariyanont, B.; et al. Physiological stress responses in horses participating in novice endurance rides. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poochipakorn, C.; Wonghanchao, T.; Huangsaksri, O.; Sanigavatee, K.; Joongpan, W.; Tongsangiam, P.; Charoenchanikran, P.; Chanda, M. Effect of exercise in a vector-protected arena for preventing African horse sickness transmission on physiological, biochemical, and behavioral variables of horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2023, 131, 104934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huangsaksri, O.; Wonghanchao, T.; Sanigavatee, K.; Poochipakorn, C.; Chanda, M. Heart rate and heart rate variability in horses undergoing hot and cold shoeing. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0305031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frippiat, T.; van Beckhoven, C.; van Gasselt, V.J.; Dugdale, A.; Vandeweerd, J.M. Effect of gait on, and repeatability of heart rate and heart rate variability measurements in exercising Warmblood dressage horses. Comp. Exerc. Physiol. 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, T.L.; Newton, J.R.; Deaton, C.M.; Franklin, S.H.; Biddick, T.; McKeever, K.H.; McDonough, P.; Young, L.E.; Hodgson, D.R.; Marlin, D.J. Retrospective study of predictive variables for maximal heart rate (HRmax) in horses undergoing strenuous treadmill exercise. Equine Vet. J. 2006, 38, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, M. Furosemide and systemic circulation during severe exercise. In Equine exercise physiology 2; ICEEP Publications: California, USA, 1987; pp. 132–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chanda, M.; Srikuea, R.; Cherdchutam, W.; Chairoungdua, A.; Piyachaturawat, P. Modulating effects of exercise training regimen on skeletal muscle properties in female polo ponies. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medicine, A. Benefit and risks associated with physical activity. In ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription; Thompson WR GN, P.L., Ed.; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, 2010; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Agüera, E.; Rubio, M.; Vivo, R.; Santisteban, R.; Munoz, A.; Castejón, F. Blood parameter and heart rate response to training in Andalusian horses. J. Physiol. Biochem. 1995, 51, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ringmark, S.; Lindholm, A.; Hedenström, U.; Lindinger, M.; Dahlborn, K.; Kvart, C.; Jansson, A. Reduced high intensity training distance had no effect on VLa4 but attenuated heart rate response in 2–3-year-old Standardbred horses. Acta Vet. Scand. 2015, 57, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Kantelhardt, J.W.; Barthel, P.; Schneider, R.; Mäkikallio, T.; Ulm, K.; Hnatkova, K.; Schömig, A.; Huikuri, H.; Bunde, A.; et al. Deceleration capacity of heart rate as a predictor of mortality after myocardial infarction: Cohort study. The Lancet 2006, 367, 1674–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasario-Junior, O.; Benchimol-Barbosa, P.R.; Nadal, J. Refining the deceleration capacity index in phase-rectified signal averaging to assess physical conditioning level. J. Electrocardiol. 2014, 47, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Pan, Q.; Zhou, G.; Fang, L.; Cao, P.; Ning, G. Resampling the RR tachogram enhances the deceleration capacity of heart rate in the assessment of chronic heart failure. In Proceedings of the 2017 10th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, 14–16 Oct. 2017, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI); pp. 1–5.

- Liu, X.; Xiang, L.; Tong, G. Predictive values of heart rate variability, deceleration and acceleration capacity of heart rate in post-infarction patients with LVEF ≥35%. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2020, 25, e12771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyerges-Bohák, Z.; Nagy, K.; Rózsa, L.; Póti, P.; Kovács, L. Heart rate variability before and after 14 weeks of training in thoroughbred horses and standardbred trotters with different training experience. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0259933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

The effects of different activity modalities on changes in minimum HR (a), mean HR (b) and mean RR intervals (c). π indicates the effect of group-by-time interaction. * indicates a significant difference between comparison pairs at p < 0.05. SEL: sedentary living; RAT: retained unstructured activities; SER: structured exercise regimen; HR: heart rate; RR: beat-to-beat interval; Min: minimum.

Figure 1.

The effects of different activity modalities on changes in minimum HR (a), mean HR (b) and mean RR intervals (c). π indicates the effect of group-by-time interaction. * indicates a significant difference between comparison pairs at p < 0.05. SEL: sedentary living; RAT: retained unstructured activities; SER: structured exercise regimen; HR: heart rate; RR: beat-to-beat interval; Min: minimum.

Figure 2.

The effects of different activity modalities on changes in time domain variables: SDNN (a), RMSSD (b), DCmod (c), pNN50 (d), RRTI (e) and TINN (f). # indicates independent group effect. *, **, *** and **** indicate significant differences between comparison pairs at p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 and 0.0001, respectively. SEL: sedentary living; RAT: retained unstructured activities; SER: structured exercise regimen; RR: beat-to-beat interval; SDNN: standard deviation of normal-to-normal RR intervals; RMSSD: root mean square of differences between the successive RR intervals; pNN50: relative number of successive RR interval pairs differing by more than 50 ms; DCmod: modified deceleration capacity; RRTI: RR triangular index; TINN: triangular interpolation of normal-to-normal RR intervals.

Figure 2.

The effects of different activity modalities on changes in time domain variables: SDNN (a), RMSSD (b), DCmod (c), pNN50 (d), RRTI (e) and TINN (f). # indicates independent group effect. *, **, *** and **** indicate significant differences between comparison pairs at p < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 and 0.0001, respectively. SEL: sedentary living; RAT: retained unstructured activities; SER: structured exercise regimen; RR: beat-to-beat interval; SDNN: standard deviation of normal-to-normal RR intervals; RMSSD: root mean square of differences between the successive RR intervals; pNN50: relative number of successive RR interval pairs differing by more than 50 ms; DCmod: modified deceleration capacity; RRTI: RR triangular index; TINN: triangular interpolation of normal-to-normal RR intervals.

Figure 3.

The effects of different activity levels on frequency domain variables: LF band (a), HF band (b), LF/HF ratio (c), total power band (d) and RESP (e).* and ** indicate a significant difference between comparison pairs at p < 0.05 and 0.01. SEL: sedentary living; RAT: retained unstructured activities; SER: structured exercise regimen; LF: low-frequency band; HF: high-frequency band; RESP: respiratory rate (estimated from RR interval recordings).

Figure 3.

The effects of different activity levels on frequency domain variables: LF band (a), HF band (b), LF/HF ratio (c), total power band (d) and RESP (e).* and ** indicate a significant difference between comparison pairs at p < 0.05 and 0.01. SEL: sedentary living; RAT: retained unstructured activities; SER: structured exercise regimen; LF: low-frequency band; HF: high-frequency band; RESP: respiratory rate (estimated from RR interval recordings).

Figure 4.

The effects of different activity levels on nonlinear variables: SD1 (a), SD2 (b) and SD2/SD1 ratio (c). # indicates independent group effect. *, ** and *** indicate significant differences between comparison pairs at p < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively. SEL: sedentary living; RAT: retained unstructured activities; SER: structured exercise regimen: structured exercise regimen; RR: beat-to-beat interval; SD1: standard deviation of the Poincaré plot perpendicular to the line of identity; SD2: standard deviation of the Poincaré plot along the line of identity.

Figure 4.

The effects of different activity levels on nonlinear variables: SD1 (a), SD2 (b) and SD2/SD1 ratio (c). # indicates independent group effect. *, ** and *** indicate significant differences between comparison pairs at p < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively. SEL: sedentary living; RAT: retained unstructured activities; SER: structured exercise regimen: structured exercise regimen; RR: beat-to-beat interval; SD1: standard deviation of the Poincaré plot perpendicular to the line of identity; SD2: standard deviation of the Poincaré plot along the line of identity.

Figure 5.

The effects of different activity levels on modification of PNS index (a), SNS index (b) and stress index (c). π and # indicate the effects of group-by-time interaction and independent group. *, ** and *** indicate significant differences between comparison pairs at p < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively. SEL: sedentary living; RAT: retained unstructured activities; SER: structured exercise regimen; PNS: parasympathetic; SNS: sympathetic.

Figure 5.

The effects of different activity levels on modification of PNS index (a), SNS index (b) and stress index (c). π and # indicate the effects of group-by-time interaction and independent group. *, ** and *** indicate significant differences between comparison pairs at p < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively. SEL: sedentary living; RAT: retained unstructured activities; SER: structured exercise regimen; PNS: parasympathetic; SNS: sympathetic.

Table 1.

Training patterns in aged horses practising structured exercise regimen.

Table 1.

Training patterns in aged horses practising structured exercise regimen.

| Training order |

Gait |

Minutes |

Training pattern |

| 1 |

Walk |

5 |

Pattern 1 |

| 2 |

Trot |

10 |

| 3 |

Walk |

1 |

| 4 |

Trot |

10 |

| 5 |

Walk |

1 |

| 6 |

Canter |

5 |

Pattern 2 |

| 7 |

Walk |

1 |

| 8 |

Canter |

5 |

| 9 |

Walk |

1 |

| 10 |

Trot |

10 |

Pattern 3 |

| 11 |

Walk |

5 |

Table 2.

HRV variables measured in geriatric horses with different activity levels.

Table 2.

HRV variables measured in geriatric horses with different activity levels.

| Variable |

Unit |

Description |

| Time domain variables |

| Min HR |

beats/min |

Minimum heart rate |

| Mean HR |

beats/min |

Mean heart rate |

| Mean RR |

ms |

Mean beat-to-beat interval |

| SDNN |

ms |

Standard deviation of normal-to-normal RR intervals |

| RMSSD |

ms |

Root mean square of differences between successive RR intervals |

| pNN50 |

% |

Number of successive RR interval pairs differing by more than 50 ms (NN50) divided by the total number of RR intervals |

| DCmod |

ms |

Modified deceleration capacity, computed as a two-point difference |

| TINN |

ms |

Triangular interpolation of normal-to-normal intervals, computed from the baseline width of a histogram displaying RR intervals |

| RRTI |

- |

RR triangular index, computed from the integral of the density of the RR interval histogram divided by its height |

| Stress index |

- |

Square root of Baevsky’s stress index |

| Frequency domain variables |

| LF |

% |

Relative power of the low-frequency band (frequency band threshold 0.01–0.07 Hz) |

| HF |

% |

Relative power of the high-frequency band (frequency band threshold 0.07–0.6 Hz) |

| RESP |

Hz |

Respiratory rate estimated from RR interval recordings |

| LF/HF ratio |

- |

Ratio of frequency band analysis to indicate sympathovagal balance |

| Total power |

ms2

|

Total power band spectrum |

| Nonlinear variables |

| SD1 |

ms |

Standard deviation of the Poincaré plot perpendicular to the line of identity |

| SD2 |

ms |

Standard deviation of the Poincaré plot along the line of identity |

| SD2/SD1 ratio |

- |

Ratio of nonlinear analysis to indicate sympathovagal balance |

| Autonomic nervous system indexes |

| PNS index |

- |

Parasympathetic nervous system index |

| SNS index |

- |

Sympathetic nervous system index |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).