1. Introduction

Colombian Paso horses (CPH) stand out in gait competitions for their endurance, movement precision, and stride frequency, requiring considerable cardiorespiratory fitness to sustain intense performances lasting from 6 to 10 minutes, during which heart rates range from 160 to 200 bpm [

1]. An objective evaluation of these animals’ physical conditioning is essential for guiding training programs and preventing overload.

Among the methods used to assess aerobic fitness in equines, incremental exercise tests have proven effective in identifying physiological effort zones through the analysis of blood lactate thresholds [

2]. The aerobic threshold (LTaer), often associated with concentrations close to 2 mmol/L of lactate, represents the transition point between predominantly aerobic metabolism and mild anaerobic activity, serving as a useful reference for training intensity prescriptions [

3]. The anaerobic threshold (LTan), typically above 4 mmol/L, marks the intensity at which lactate production exceeds clearance, indicating the onset of metabolic fatigue [

4,

5].

Various approaches have been proposed to estimate these thresholds, including visual methods, segmented regression models, and curve-based lactate analyses. The gold standard, however, remains the determination of the maximal lactate steady state (MLSS) [

6,

7]. In parallel, the use of heart rate as a non-invasive marker has gained importance, particularly under field conditions, due to its practicality and its strong correlation with metabolic variables—especially in horses where stride frequency, rather than speed, is the key determinant, such as in gaited breeds like Colombian Paso Horses (CPH). Wearable devices, such as heart rate monitors and GPS units, can be fitted to horses non-invasively and comfortably [

8].

The classic approach in sports medicine establishes a direct relationship between heart rate zones and lactate production. However, in Colombian Paso Horses (CPH), some studies have indicated that this breed may produce lactate at very early stages, even when the heart rate corresponds to what is typically considered a low-intensity zone [

9].

Nevertheless, there are scarce studies validating the corresponding between heart rate zones and lactate thresholds in CPH, a breed whose gait and metabolic characteristics differ significantly from those of others breeds such us Thoroughbreds and Arabians, measured by oxygen consumption [

10,

11]. In this context, the aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between heart rate zones and estimated lactate thresholds (2 mmol/L, 4 mmol/L, and the visually determined threshold) during a field-based incremental exercise test in 18 Colombian Paso Horses. The different methods were compared, and the results are expected to contribute to the understanding of breed-specific exercise physiology.

2. Materials and Methods

The experiment was conducted in a “Very Humid Lower Montane Forest” life zone, located at 2130 meters above sea level, with ambient temperatures ranging from 12 to 18 °C and relative humidity of 69%. The study followed ethical guidelines and was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Antioquia under protocol #122 on February 5, 2018.

Eighteen Colombian Paso Horses (CPH), both male and female, with an average weight of 371 ± 30 kg, were kept in paddocks and fed diets formulated according to NRC (2007) recommendations. Water and mineral salt were provided ad libitum. Before the sample phase, all animals underwent physical, hematological, and biochemical examinations to ensure health status.

2.1. Groups

Nine untrained horses (mean age: 38 ± 6.2 months) and nine trained horses (mean age: 83 ± 26.9 months) were conveniently selected. The animals were assigned to two experimental groups: the untrained group (GD), consisting of horses at the beginning of their performance process, and the trained group (GT), consisting of horses undergoing a continuous and stable training program.

2.2. Incremental Stress Testing (IET)

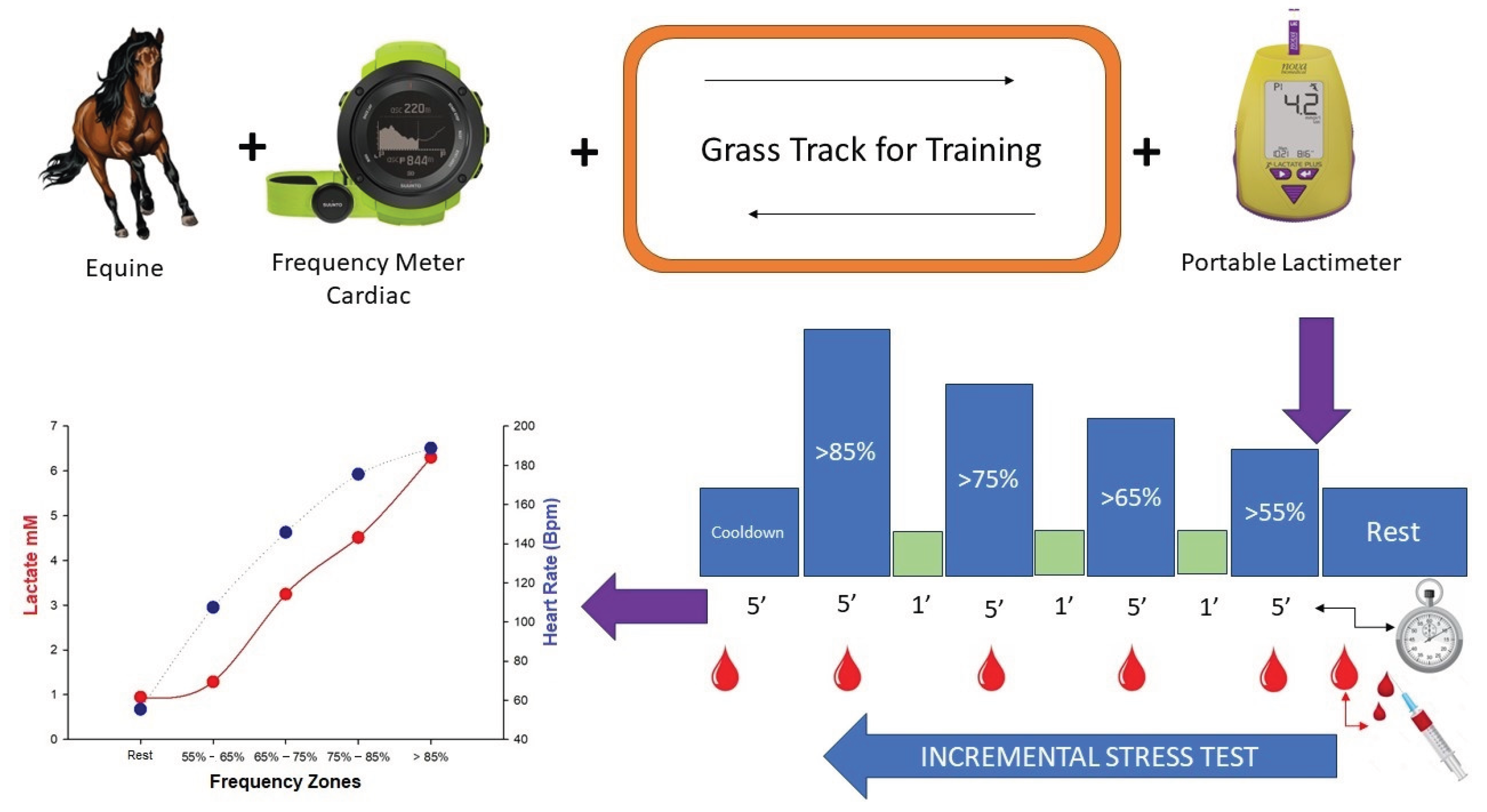

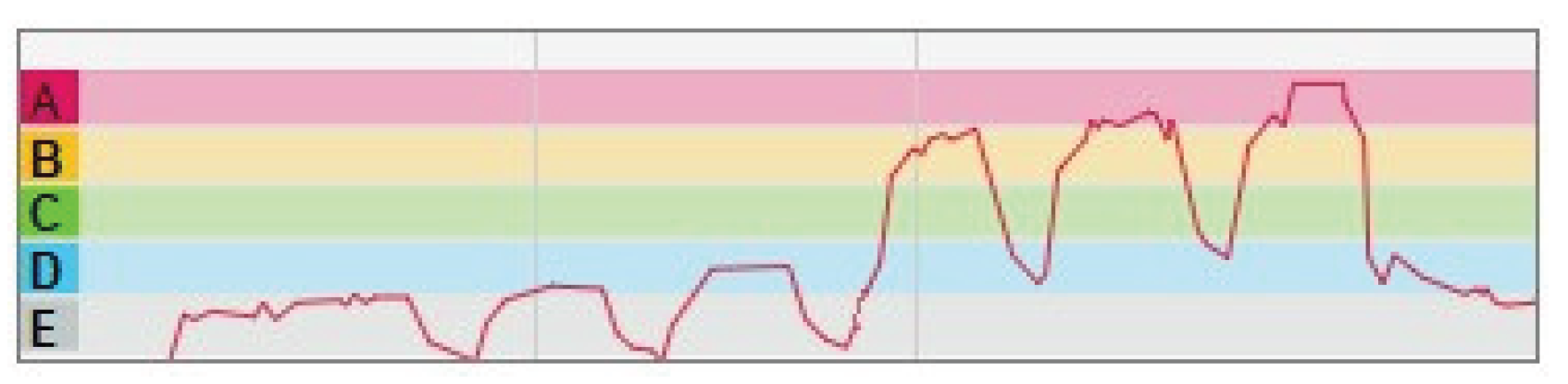

The selected animals underwent a standardized field exercise test lasting approximately 30 minutes, consisting of four progressive intensity stages, with rest periods and a final recovery phase [

9]. Heart rate (HR) was monitored using an Ambit 3 sensor (Suunto

®, Finland). The HR monitor had been validated by comparison with another device and with an electrocardiograph [

12]. Exercise intensity was defined according to HR zones (

Figure 1): warm-up (55–65% HRmax), moderate (65–75% HRmax), high (75–85% HRmax), and maximal (≥85% HRmax). Each stage included a 1-minute rest interval [

13]. The track measured 35 m in length and 20 m in width, covered with dry sand similar to that used in competitions, and the exercise was performed in an oval pattern. Each stage consisted of 5 minutes of continuous exercise [

13] (

Figure 2).

2.3. Blood Collection

Blood samples for lactate analysis were collected using a Nova Plus device (Nova Biomedical, USA) before the IET (rest), at the end of each IET stage, and after the IET (cool-down). Lactometer was previously validated for equine measures [

14]. Approximately 4 mL of blood were collected via jugular venipuncture using vacuum tubes with 25 × 0.8 mm needles and EDTA + sodium fluoride anticoagulant. Additional samples were taken for CK, creatinine, urea (BUN), and AST analysis before (at rest) and after exercise (at the end of IET), placed in dry tubes, and analyzed using enzymatic kinetic colorimetric methods.

2.4. Determination of the Heart Rate Zone Corresponding to the Lactate Threshold

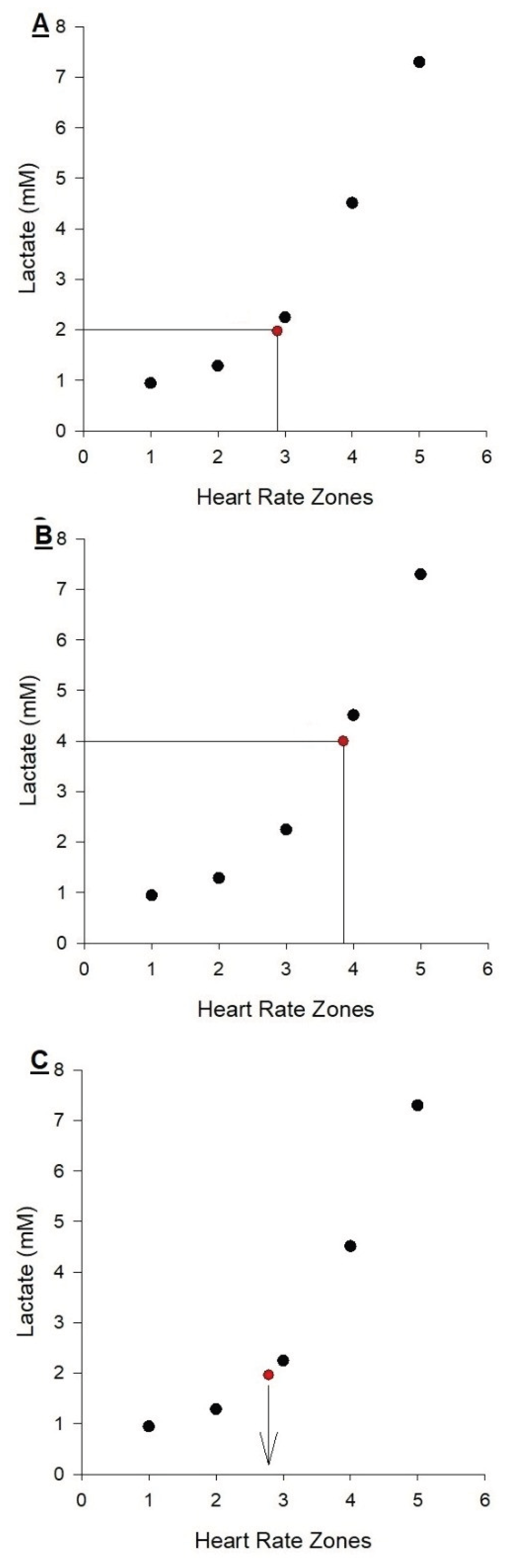

The results from each horse’s samples were analyzed using Excel, following the methods of Ferraz et al. [

15]. All methods are illustrated in

Figure 3 and described below.

Pre-established values for ZL2 and ZL4 in horses were used (

Figure 3A,B); these points correspond to the lactate concentration at which several authors have reported a shift from linear to exponential lactate production, surpassing clearance rates.

The visual method consisted of identifying the point at which the lactate concentration increased non-linearly, representing an exponential rise [

16]. This analysis was performed by two experts in the methodology, who defined the point corresponding to the visual lactate threshold (

Figure 3C).

Once the thresholds were estimated, they were correlated with heart rate zones: Zone 1 (< 55% HRmax), Zone 2 (55–65%), Zone 3 (65–75%), Zone 4 (75–85%), and Zone 5 (≥ 85%). The maximum heart rate was estimated based on literature, which indicates that horses have a maximum HR near 220 bpm. The heart rate zones were calculated accordingly [

12,

17,

18].

2.5. Experimental Design and Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using Sigma software version 14.5. A mixed-effects model was applied, considering the animal as a random effect and time, training, and their interaction as fixed categorical effects. A repeated measures mixed ANOVA was conducted, and means were compared using Tukey’s test. Differences between HR zones for GT vs. GD were tested using t-tests and one-way ANOVA, with significance set at 5% (P < 0.05). For the biochemical parameter analysis, paired t-tests were performed within each group (pre- vs. post-exercise), and unpaired t-tests were used to compare between groups (P < 0.05).

3. Results

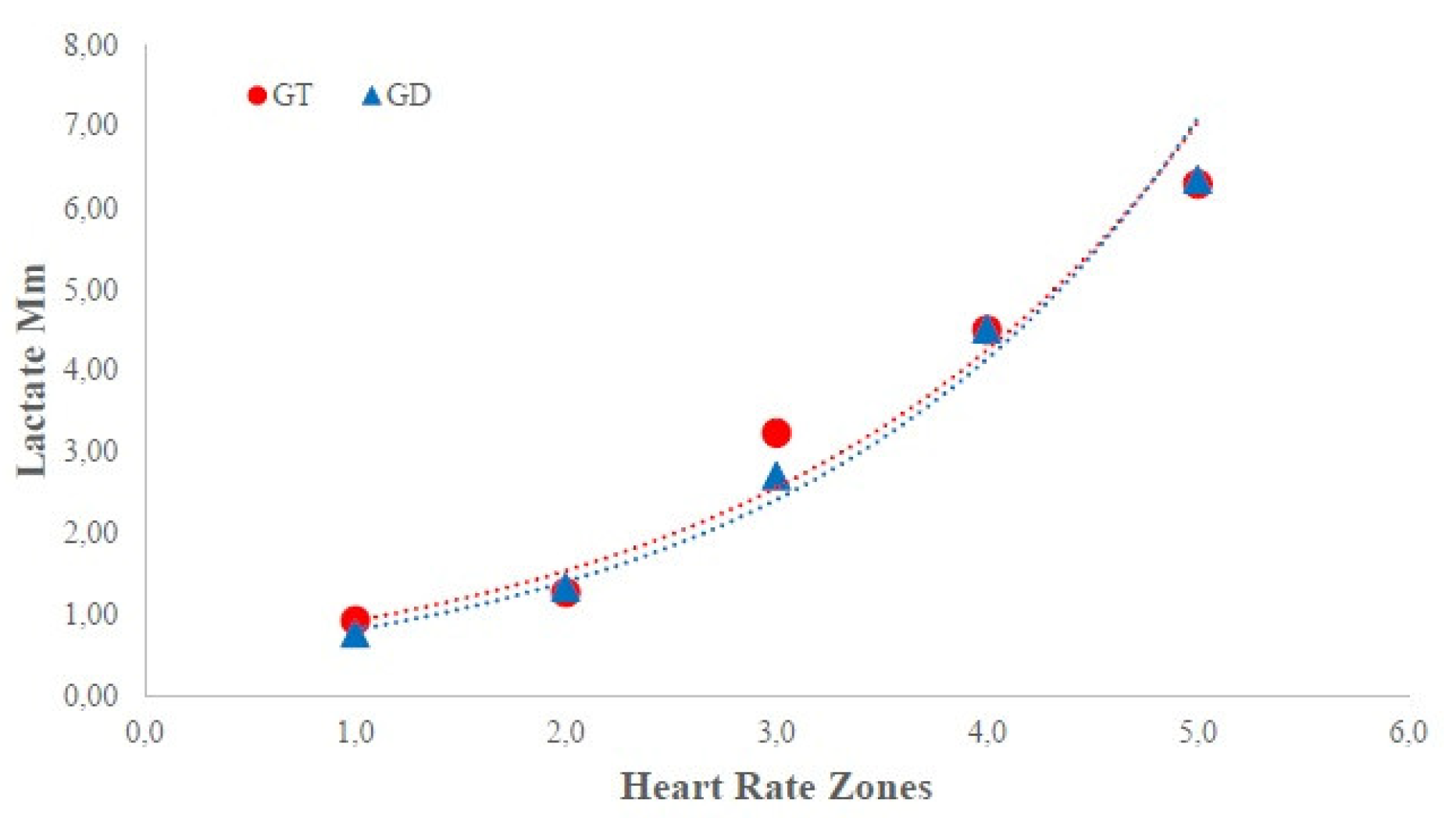

This study provides a systematic analysis of the feasibility of estimating the aerobic lactate threshold (LTaer) in horses using predictive methods based on blood lactate levels. There was no significant difference between groups when analyzing lactate values obtained during the test; however, within-group comparisons revealed statistically significant differences between the >85% and 75–85% HRmax stages, which was expected due to the exponential rise in lactatemia. These results are shown in

Figure 4.

Regarding heart rate, similar statistical patterns to those of lactate were observed, with no differences between groups, but significant within-group differences between the >85% and 75–85% HRmax stages and the other stages.

Based on the blood lactate data, predictive methods were applied to identify the aerobic threshold and, from this point, to determine the corresponding heart rate zone. The methods were applied to both groups (

Table 1), identifying the heart rate zone in which each threshold fell. In the trained group (GT), the ZL4 method placed the threshold in heart rate zone 4, which was also observed for the untrained group (GD). The ZL2 threshold corresponded to zone 2 for GT and zone 3 for GD. Using the visual method, the average threshold was around 1.32 mmol/L, corresponding to heart rate zone 2.

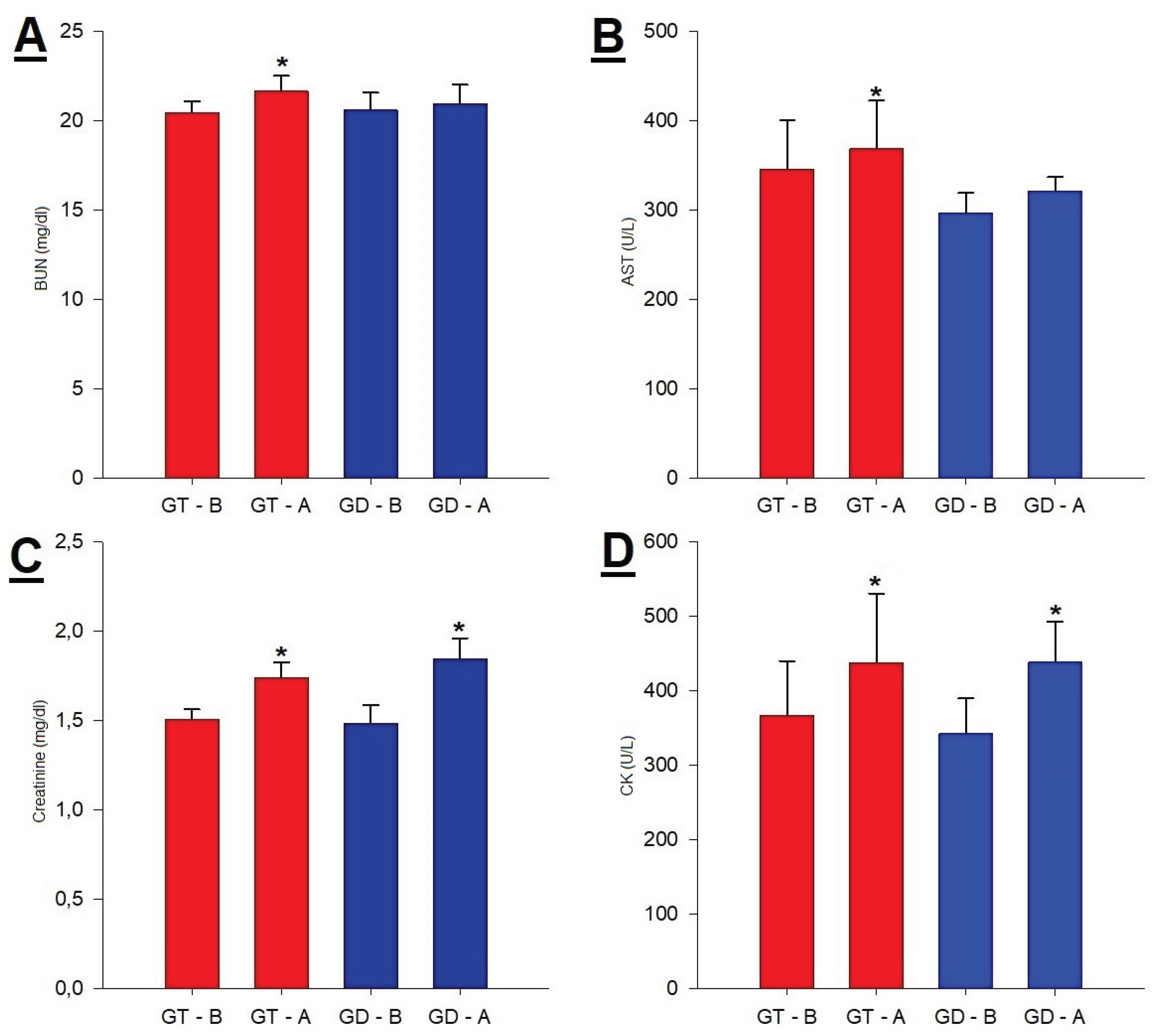

To assess the physiological changes induced by exercise, biochemical biomarkers such as CK, AST, creatinine, and urea (BUN) were analyzed, aiming to demonstrate systemic changes resulting from the imposed exercise load. The results of these analyses are shown in

Figure 5.

4. Discussion

Despite the popularity of Colombian Paso Horses (CPH) in Colombia and other countries, there is a lack of studies addressing their physical work capacity, and training programs designed for this breed often lack scientific foundation, limiting their maximum athletic potential. Predictive methods for determining the aerobic lactate threshold (LTaer) have already been applied to human athletes in various sports [

19,

20,

21,

22], as well as to dogs [

15] and horses [

23,

24].

For many years, measuring physiological parameters such as heart rate percentage and blood lactate concentration during and after exercise has been a widely used method to assess physical effort intensity [

17,

25,

26]. In CPH, these parameters, combined with lactate threshold predictors, are highly useful for guiding training loads, especially considering the limitations of field-based testing. The predictive approach used in this study offers a relevant opportunity to deepen the understanding of the relationship between exercise intensity and metabolism in CPH.

This study proposes an additional method for predicting LTaer under field conditions in CPH, based on visual assessment and heart rate alone. Among more than 25 methods available for estimating LTaer using the speed–lactate curve [

26], the main conclusion of the present study is that, under field conditions, it is feasible to estimate the exercise intensity corresponding to LTaer in CPH using some of the tested heart rate–based methods.

Another relevant factor is the evolution of wearable devices, which has made heart rate monitoring more practical and accessible for equine sports veterinarians. This highlights the importance of implementing training protocols based on heart rate zones, specifically adapted to each breed and equestrian discipline [

27].

Identifying the lactate threshold is a well-established and essential parameter for evaluating athletic potential and guiding training programs [

25,

28,

29,

30,

31]. In horses, this threshold is a crucial predictor of exercise intensity and fitness level in endurance training [

32]. Heart rate data are also widely used to monitor and analyze physical training in athletes, including humans [

25,

33]. Therefore, establishing the LTaer in CPH and training them based on the heart rate zones where this threshold occurs may represent a more accurate approach, contributing to improved physical fitness and, most importantly, reducing the risk of musculoskeletal injuries and other overload-related conditions.

In this study, most horses presented LTaer within zone 2 according to the visual method for both groups, zone 2 for the trained group (GT), and zone 3 for the untrained group (GD) using the ZL2 method, and zone 4 using the ZL4 method. These findings indicate that if the training goal is to improve aerobic capacity, exercises should be performed within these intensity zones. This is feasible and can be effectively controlled using portable heart rate monitors. This finding is especially important considering that riders often train CPH horses at heart rates above 75% of HRmax. Current literature reinforces the necessity of training in different heart rate zones to develop both aerobic and anaerobic excellence in equine athletes [

33].

In humans, studies have already demonstrated significant variations in blood lactate concentrations among individuals [

34] and across different sports disciplines [

35]. Since equine exercise physiology concepts were largely adapted from human medicine, it is relevant to investigate these indices in different equestrian modalities. In Thoroughbred horses, for instance, it has been shown that V4 does not adequately represent the lactate threshold [

36]. In Arabian horses, the maximum lactate steady state (MLSS) concentrations were significantly lower than 4 mmol/L in various treadmill protocols, indicating that V4 is also not suitable for predicting this threshold in that breed [

37]. Therefore, practical, non-invasive methods such as those proposed in this study may represent a significant advancement in CPH training. Structuring training based on heart rate zones could be a crucial step in enhancing the athletic development of this breed.

Finally, to analyze whether the external workload imposed by the test caused transient changes in the internal load of the animals, the variables creatinine, urea (BUN), AST, and CK were evaluated in all subjects (

Figure 5). There were statistically significant differences between pre- and post-exercise time points; however, no significant differences were found between experimental groups, indicating that the workload was evenly distributed among all animals [

37].

Establishing the MLSS in CPH would be an important step toward developing training protocols more precisely tailored to the physical capacity of these horses. Future studies should focus on expanding the use of heart rate zones in CPH training, including identifying the zone corresponding to the MLSS a factor that could revolutionize training strategies for this breed, especially considering the accessibility of wearable technology and its potential positive impact on performance.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed, specific heart rate intensity zones method for Colombian Paso Horses (CPH) aerobic and anaerobic threshold calculation under field conditions. The results demonstrated that it is feasible to estimate the aerobic lactate threshold (LTaer) using accessible and non-invasive methods, particularly through the analysis of heart rate zones. This approach represents a promising tool for guiding individualized training programs, optimizing physical fitness, and reducing the risk of injury. The use of wearable devices enhances the practical applicability of training zones, promoting greater control and precision in the physical preparation of CPH horses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing—original draft preparation A.M.Z.C and M.P.A.G.; formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation D.B.D and I.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Institución Universitaria Visión de las Américas.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad de Antioquia (protocol code #122 on February 5, 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all animals’ owners.:

Data Availability Statement

Data Availability under requisition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AST – Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BUN – Blood urea nitrogen |

| CK – Creatine kinase |

| CPH – Colombian Paso Horse |

| HR – Heart rate |

| HRmax – Maximum heart rate |

| GD – Untrained group (breaking group) |

| GPS – Global Positioning System |

| GT – Trained group |

| LTaer – Aerobic lactate threshold |

| LTan – Anaerobic lactate threshold |

| MLSS – Maximal lactate steady state |

| IET – Incremental exercise test |

| ZL2 – Zone corresponding to the 2 mmol/L lactate threshold |

| ZL4 – Zone corresponding to the 4 mmol/L lactate threshold |

References

- Mendoza, R.; et al. Heart rate responses in Paso horses during field performance tests. J Equine Sci. 2021;32(4):225–231.

- Courcoucé, A.; et al. Blood lactate thresholds in equine performance assessment: new perspectives. Equine Vet J. 2023;55(1):12–19.

- Gondin, D.; et al. Aerobic conditioning and lactate thresholds in athletic horses: revisiting training zones. Comp Exerc Physiol. 2022;18(3):145–152.

- Lindinger, M.; et al. Current concepts in lactate kinetics and threshold determination in equine athletes. Vet Sports Med. 2024;4(2):67–75.

- Littiere, T.O.; Costa, G.B.; Sales, N.A.A.; Carvalho, J.R.G.; Rodrigues, I.D.M.; Ramos, G.V.; Ferraz, G.C. Evaluating plasma lactate running speed derived parameters for predicting maximal lactate steady state in teaching horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2025 Apr; 147:105385. [CrossRef]

- Vervuert, I,; et al. Accuracy of visual and computational methods for lactate threshold detection in horses. Animals (Basel). 2022;12(8):1012–1024.

- Ramos, G.V.; Titotto, A.C.; Costa, G.B.D.; Ferraz, G.D.C.; Lacerda-Neto, J.C.D. Determination of speed and assessment of conditioning in horses submitted to a lactate minimum test—alternative approaches. Front Physiol. 2024;15:1324038.

- Gómez, J.; et al. Heart rate as a surrogate marker for lactate threshold in endurance horses. Front Vet Sci. 2023;10. [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga-Cabrera, A.M.; Casas-Soto, M.J.; Martínez-Aranzales, J.R.; Correa-Valencia, N.M.; Arias-Gutiérrez, M.P. Blood lactate concentrations and heart rates of Colombian Paso horses during a field exercise test. Vet Anim Sci. 2021, 13, 100-185.

- Massie, S.; Léguillette, R.; Bayly, W.; Sides, R.; Zuluaga-Cabrera, A.M. Oxygen consumption, locomotory-respiratory coupling and exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage in horses during the Paso Fino gait. J Vet Intern Med. 2024; 38(6): 3337-3345. [CrossRef]

- Massie, S.; Vega, L.C.C.; Zuluaga-Cabrera, A.M.; Bayly, W.M.; Léguillette, R. Colombian Criollo horses’ trot, trocha, and gallop are submaximal oxygen consumption gaits with unique locomotory-respiratory coupling. Am J Vet Res. 2025, 14, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Arias, M.P.; Sánchez, H.E.; Duque, E.C.; Maya, L.A.; Becerra, J.Z. Estimación de la intensidad de trabajo en un grupo de caballos criollos colombianos de diferentes andares. CES Med Vet Zootec. 2006;1:18–32.

- Arias-Gutiérrez, M.P.; Arango, L.; Maya, J.S. Effects of two training protocols on blood lactate in paso fino horses. Rev Med Vet Zoot. 2019, 66(3):219–230.

- Ashlee, A.H.; Cortney, K.; Stablein, A.L.; Fisher, H.M.; Greene, Y.S.; et al. Validation of the Lactate Plus Lactate Meter in the Horse and Its Use in a Conditioning Program. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2014, 3(4): 1064-1068. [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, G.C.; et al. Predicting maximal lactate steady state from lactate thresholds determined using methods based on an incremental exercise test in beagle dogs: A study using univariate and multivariate approaches. Res Vet Sci. 2022, 152, 289–299.

- Cunha, R.R.; Cunha, V.N.; Segundo, P.R.; Moreira, S.R.; Kokubun, E.; Campbell, C.S.G.; Oliveira, R.J.; Simões, H.G. Determination of the lactate threshold and maximal blood lactate steady state intensity in aged rats. Cell Biochem Funct. 2009, 27, 351–357.

- Evans, D.L. Physiology of equine performance and associated tests of function. Equine Vet J. 2007, 39(4), 373–383.

- Hinchcliff, K.W.; Kaneps, A.J.; Geor, R.J. Equine Sports Medicine and Surgery: Basic and Clinical Sciences of the Equine Athlete. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2013.

- Faude, O.; Kindermann, W.; Meyer, T. Lactate threshold concepts: how valid are they? Sports Med. 2009;39(6):469–490.

- Spurway, N.C. Aerobic exercise, anaerobic exercise and the lactate threshold. Br Med Bull. 1992, 48(3), 569–591.

- Cairns, S.P. Lactic acid and exercise performance: culprit or friend? Sports Med. 2006, 36(4), 279–291.

- Heuberger, J.A.A.C.; Gal, P.; Stuurman, F.E.; de Muinck Keizer, W.A.S.; Mejia-Miranda, Y.; Cohen, A.F. Repeatability, and predictive value of lactate threshold concepts in endurance sports. PLoS One. 2018, 13(11), e0206846.

- Gondim, F.J.; Zoppi, C.C.; Pereira-da-Silva, L.; Vaz de Macedo, D. Determination of the anaerobic threshold and maximal lactate steady state speed in equines using the lactate minimum speed protocol. Comp Biochem Physiol A. 2007, 146, 375–380.

- De Mare, L.; Boshuizen, B.; Plancke, L.; De Meeus, C.; De Bruijn, M.; Delesalle, C. Standardized exercise tests in horses: Current situation and future perspectives. Vlaams Diergeneeskd Tijdschr. 2017, 86, 63–72.

- Jamnick, N.A.; Pettitt, R.W.; Granata, C.; Pyne, D.B.; Bishop, D.J. An examination and critique of current methods to determine exercise intensity. Sports Med. 2020, 50(10), 1729–1756.

- Messias, L.H.D.; Gobatto, C.A.; Beck, W.R.; Manchado-Gobatto, F.B. The lactate minimum test: Concept, methodological aspects and insights for future investigations in human and animal models. Front Physiol. 2017, 8, 389.

- Ferraz, G.D.C. The next decade for sport horses will be the time of wearable technology: Wearable technology for sport horses. Int J Equine Sci. 2023, 2(2), 1–2.

- Jones, A.M.; Carter, H. The effect of endurance training on parameters of aerobic fitness. Sports Med. 2000, 29(6), 373–386.

- Morton, R.H. The critical power and related whole-body bioenergetic models. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006, 96, 339–354.

- Jones, A.M.; Burnley, M.; Black, MI.; Poole, D.C.; Vanhatalo, A. The maximal metabolic steady state: redefining the ‘gold standard’. Physiol Rep. 2019, 7(10), e14098.

- Vanhatalo, A.; Jones, A.M.; Burnley, M. Application of critical power in sport. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2011, 6(2), 128–136.

- Lindner, A.E. Relationships between racing times of Standardbreds and v4 and v200. J Anim Sci. 2010, 88(3), 950–954. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, H.; Xiao, J.; Xu, W.; Huang, M-C. A fitness training optimization system based on heart rate prediction under different activities. Methods. 2022, 205, 89–96.

- Beneke, R.; von Duvillard, S.P. Determination of maximal lactate steady state response in selected sports events. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996, 28(2), 241–246.

- Beneke, R.; Leithäuser, R.M.; Hütler, M. Dependence of the maximal lactate steady state on the motor pattern of exercise. Br J Sports Med. 2001, 35, 192–196.

- Lindner, A.E. Maximal lactate steady state during exercise in blood of horses. J Anim Sci. 2010, 88, 2038–2044.

- Scheidegger, M.D.; et al. Quantitative gait analysis before and after a cross-country test in a population of elite eventing horses. J Equine Vet Sci. 2022, 117.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).